5.1. Our Findings

The competitive performance of the proposed ADFF-Net framework in terms of the integrated HS metric can be attributed to the dual-stream acoustic features and the ADFF module design, which combines attention-based feature fusion with a skip connection. First, combining the Mel-FBank and Mel-spectrogram features effectively balances the classification metrics (

Table 2). For example, MFCC features yield the highest specificity (88.16%) but extremely low sensitivity (9.43%), reflecting a severe imbalance in prediction performance. By contrast, Mel-FBank features achieve a higher HS score (57.69%), slightly outperforming Mel-spectrogram features. Importantly, the combination of Mel-FBank and Mel-spectrogram features consistently outperforms any single feature input or other pairwise combinations, demonstrating their strong complementarity. Second, the ADFF module achieves superior performance compared to baseline fusion strategies such as Concat-AST, AST-Concat, and ADFF-Net without the SC (

Table 3). While simple concatenation remains a common approach for feature integration, it often lacks the capacity to exploit complex dependencies between features. More advanced strategies, such as feature-wise linear modulation for context-aware computation [

50] or cross-attention fusion for integrating multi-stream outputs [

51], highlight the need for principled fusion mechanisms. ADFF-Net addresses this by leveraging attention-guided fusion and an SC to enhance feature interactions and stabilize learning. Overall, by jointly incorporating dual-branch acoustic inputs and an advanced fusion architecture, ADFF-Net achieves a balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity while reaching competitive state-of-the-art performance. This indicates strong generalization capability even under class-imbalance conditions.

It is also observed that ADFF-Net struggles to identify abnormal respiratory sounds in this RSC task (

Figure 10 and

Table 6), with particularly low SEN values for crackle and wheeze events (

Table 4). Several underlying factors may explain this problem. First, the ADFF module and AST backbone operate on time–frequency patches with a relatively coarse temporal resolution and global token aggregation. This design favors stable, high-energy patterns that characterize normal breathing but tends to smooth out short, low-energy transients. However, crackles and wheezes occupy only a few patches in sound events and therefore contribute weakly to the feature representation. Second, the attention weights inside the ADFF module are supervised through the four-class cross-entropy loss. Under the severe class imbalance of the ICBHI2017 dataset, the learned attention maps are biased toward the discrimination for the majority normal class. Third, the objective function treats all training cases equally. Therefore, it may drive the decision boundary toward higher specificity at the expense of sensitivity, as reflected in the confusion matrix in

Figure 10 and the per-class metrics in

Table 4. Together, these factors explain why ADFF-Net fails to reliably capture a substantial fraction of crackle and wheeze events.

On the ICBHI2017 database, there is still considerable room for improvement in the four-class classification task (

Table 6). The highest HS value (63.54%) is achieved by the BTS model [

47], which introduces a text–audio multi-modal approach leveraging metadata from respiratory sounds. Specifically, free-text descriptions derived from metadata, such as patient gender and age, recording device type, and recording location, are used to fine-tune a pre-trained multi-modal model. Meanwhile, similar advanced techniques are commonly adopted in recent SOTA methods, including large-scale models [

16,

28,

30], contrastive learning [

16,

29,

48], fine-tuning strategies [

28,

30], and data augmentation or cross-domain adaptation [

16,

28,

29]. A key limitation of this study is the relatively low class-wise SEN value, and recent SOTA methods typically report SEN values between 42% and 46%. From a clinical perspective, such sensitivity is insufficient for medical diagnosis, because many abnormal breaths would be wrongly classified as normal sounds. Therefore, the proposed model should be regarded as a methodological contribution and a proof of concept on this public database, rather than as a deployable clinical decision-support tool in its current form. Notably, this limitation is not unique to ADFF-Net, but reflects a broader RSC challenge. Abnormal acoustic events such as crackles and wheezes are often subtle, short in duration, easily masked by background noise, and highly variable across patients and recording conditions. These intrinsic characteristics, combined with significant inter-class imbalance in the ICBHI dataset, make accurate detection particularly difficult for all existing deep learning systems. Accordingly, improving SEN remains an open research problem for the entire field rather than a deficiency specific to a single architecture.

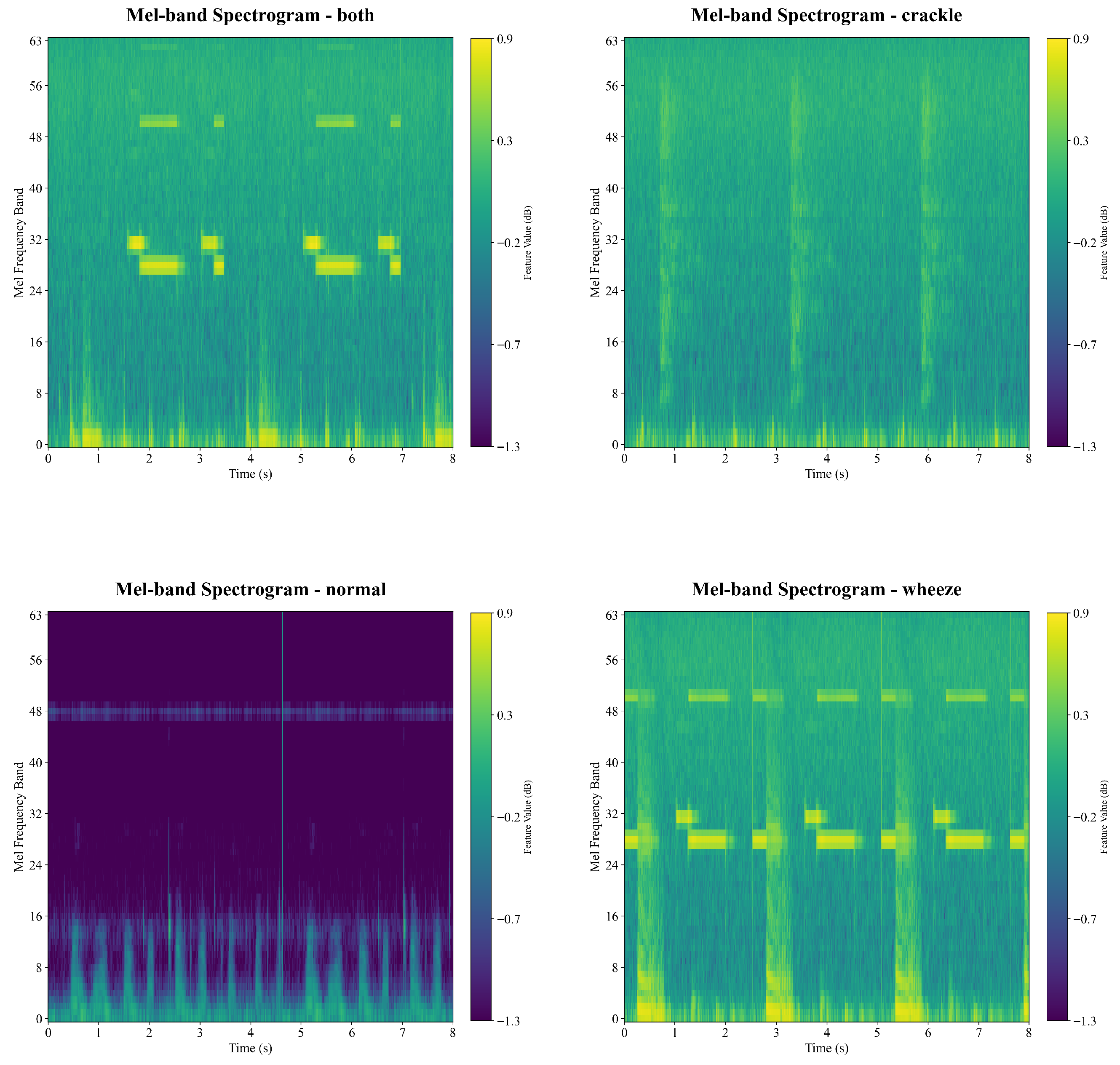

Accurate classification of respiratory sounds into normal, crackle, wheeze, and both categories remains challenging for several reasons [

2,

6,

7,

8]. First, the acoustic boundaries between classes are often blurred. In clinical practice, crackles and wheezes frequently occur together, making the both category a composite of two abnormal patterns with overlapping spectral–temporal signatures. Second, substantial intra-class variability and inter-class similarity complicate discrimination. Intra-class variability arises from differences in age, body habitus, breathing effort, auscultation site, and disease stage. Conversely, inter-class similarity may occur when classes share similar frequency ranges or when acoustic patterns are distorted by background noise or inconsistent recording quality. These phenomena are visible in the Mel-scale representation, as shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. Third, some abnormal sounds are faint, brief, or intermittent, making them easily confused with normal breathing. This challenge is reflected in the misclassification patterns shown in the confusion matrix (

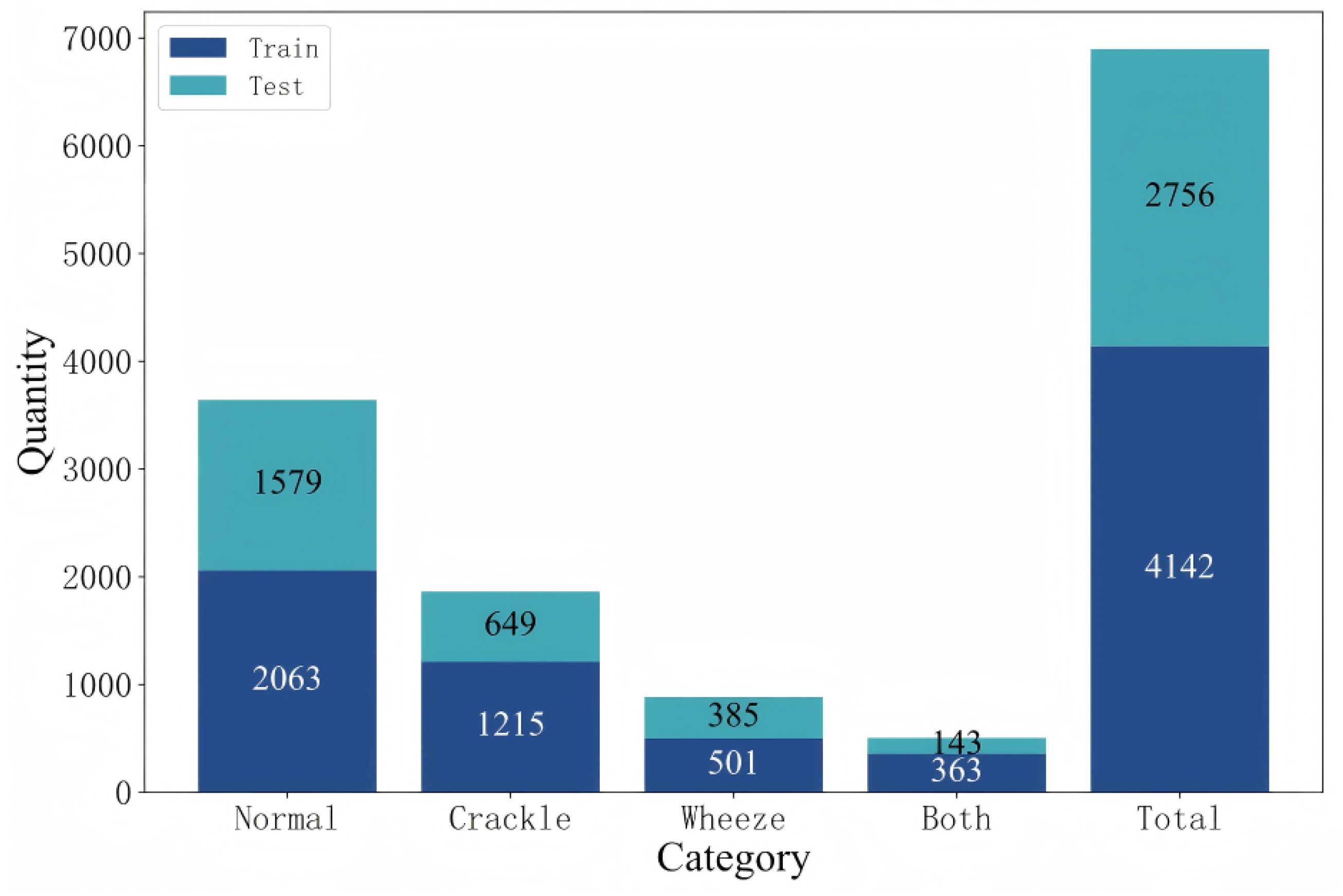

Figure 10). Fourth, class imbalance is common. Normal recordings usually dominate public datasets, while crackle, wheeze, and both categories are under-represented [

5]. This imbalance biases model training and hinders reliable learning of minority classes. In summary, the task is difficult due to overlapping acoustic characteristics, high temporal variability, environmental and recording noise, and severe data imbalance [

52]. Addressing these challenges requires more expressive feature representations and robust classification strategies capable of reliably distinguishing the four respiratory sound categories.

5.2. Future Directions

While substantial improvement in network design and classification performance is achieved in the four-class prediction task on the ICBHI2017 database, several directions remain open for future investigation. Given that the present study evaluates ADFF-Net only on the ICBHI2017 database and under a single dual-stream configuration, the current experimental evidence is not sufficient to support strong claims of broad generalizability beyond this database. In the short term, future work will examine ADFF-style modules on related problems, such as cough and heart sound analysis, where multi-representation and multi-feature schemes have already been shown to improve classification performance [

23,

25,

35,

38,

46]. Beyond medical acoustics, attention-based fusion of heterogeneous signals has also proven effective in other signal processing contexts, including environmental sound recognition and multi-modal medical diagnosis [

33,

36]. Therefore, evaluating ADFF-type fusion modules in these broader scenarios will be essential for rigorously establishing and refining the cross-dataset and cross-domain generalizability.

An important direction is balancing the number of cases across categories in respiratory sound databases [

4]. Imbalanced datasets often bias models toward majority classes, resulting in poor sensitivity for minority categories [

5]. Several strategies can be considered to address this issue. First, expanding clinical collaborations can help collect recordings from under-represented disease categories, ensuring a representative distribution of patient conditions. However, this approach is resource-intensive, requiring significant time, expert involvement, and funding. Second, data augmentation can be applied using signal processing techniques such as time-stretching, pitch shifting, noise injection, or spectrogram-level transformations to artificially increase the diversity of existing samples [

5]. Third, generative modeling offers a promising direction, where realistic synthetic respiratory sound samples are produced to synthesize rare pathological categories while maintaining clinical validity, including conditional generative adversarial networks [

28,

53], variational autoencoders [

54], and generative adversarial diffusion [

55]. Fourth, domain adaptation provides another feasible solution by mitigating distribution shifts across recording devices, patient populations, or clinical centers [

9,

16,

28,

29,

30]. This can effectively increase usable data samples and improve the generalization of deep learning models. In addition, adopting robust mathematical frameworks widely used in other domains to address class-imbalance problems and enhance sensitivity is highly valuable. These techniques include robust imbalance classification via deep generative mixture models [

56], class rebalancing through class-balanced dynamically weighted loss functions [

57], and class-imbalance learning based on theoretically guaranteed latent-feature rectification [

58].

Diverse signal collection is another direction essential for advancing respiratory sound analysis. Relying solely on acoustic signals may restrict a model’s ability to capture all relevant information. Four complementary directions can be considered. First, fully exploiting acoustic signals remains fundamental. High-quality respiratory sound recordings are the core modality, and improvements such as multi-site recordings and standardized acquisition protocols [

4,

5] can enhance reliability while reducing noise-related biases. Second, incorporating additional modalities can provide richer diagnostic context. For instance, integrating physiological signals or chest imaging data can complement acoustic features and improve robustness in clinical decision-making [

46]. Finally, leveraging contextual metadata, including patient age, gender, medical history, recording device type, and auscultation location, provides valuable cues that refine model predictions and support more personalized assessments [

47]. Additionally, the transformation of respiratory sounds into diverse quantitative forms, not limited to MFCCs, Mel-spectrograms, and deeply learned features [

16,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], facilitates comprehensive information representation [

5], enabling more effective discriminative feature identification and knowledge discovery.

Advances in network design are also key to driving further improvements in RSC performance. First, Transformer architectures remain the dominant backbone, often outperforming traditional deep networks. Their self-attention mechanisms allow models to capture long-range temporal dependencies in acoustic signals and highlight subtle but clinically relevant sound events [

14,

15,

16,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Second, extending large multi-modal models to integrate respiratory sounds, free-text patient descriptions, additional modalities, and acoustic feature interpretations can provide more comprehensive and context-aware representations [

47,

59]. This integration bridges the gap between signal-level patterns and clinical knowledge, thereby enhancing model robustness and generalization. In addition, other advanced strategies hold significant promise for boosting performance and clinical applicability. These include multi-task learning, which enables joint optimization of related tasks such as RSC and disease diagnosis [

60]; contrastive learning, which facilitates the extraction of discriminative embeddings under limited labeled data [

16,

29,

48]; and domain adaptation, which mitigates distribution shifts across recording devices, patient populations, and clinical centers [

9,

16,

28,

29,

30].

Beyond architectural design and feature fusion, loss-function engineering offers a promising direction for improving diagnostic sensitivity under severe class imbalance. In the ADFF-Net framework, the standard cross-entropy loss may not optimally address the skewed distribution of normal and pathological classes in the ICBHI2017 dataset [

4,

5]. Future studies could therefore explore class-weighted cross-entropy and Focal Loss to more aggressively penalize false negatives and to emphasize under-represented pathological categories such as crackles and wheezes [

52]. Systematically evaluating these loss functions in combination with the proposed ADFF module may help alleviate the high false-negative rate and enhance the clinical viability of respiratory sound classification models.

In the medical domain, where annotated datasets are often scarce and costly to obtain, relying solely on fully supervised learning is increasingly impractical. Expert labeling of respiratory sounds requires trained clinicians, careful listening, and sometimes consensus among multiple annotators, making large-scale high-quality labels difficult to collect [

4,

46]. As a result, exploring alternative training paradigms that reduce dependence on precise labels has become essential. Promising directions include weakly supervised learning, which uses coarse or imperfect labels to guide model training [

61], and unsupervised learning, which discovers structure in data without relying on any labels [

62]. By encouraging the model to pull similar samples closer and push dissimilar samples apart in the feature space, contrastive learning, a powerful branch of self-supervised learning, has shown strong potential in respiratory sound analysis [

16,

29,

48] and medical text generation [

63]. These alternative paradigms can mitigate the limitations of small, imbalanced, or imperfectly labeled medical datasets and enhance the robustness of downstream classification models [

64]. Ultimately, integrating weakly supervised, unsupervised, and contrastive learning approaches may provide a more scalable and label-efficient pathway for future respiratory sound research.

Given the inherent “black-box” characteristic of deep learning-based models, explainable AI (XAI) should be a central focus of future research in clinical practice [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. A variety of XAI techniques can shed light on how models arrive at their predictions. For example, attention-map visualizations and gradient-based attribution methods [

66,

67] can identify the specific time–frequency regions that most strongly influence a model’s decisions. These tools allow researchers and clinicians to verify whether the model relies on physiologically meaningful acoustic cues rather than spurious noise or recording artifacts. Meanwhile, recent advances in Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs) provide an analytical and interpretable view by using explicit scalar functions along each input dimension to replace nonlinear transformations in deep learning [

68]. Building on this formulation, TaylorKAN further employs Taylor-series approximations to decompose these functions into analytically tractable low-order polynomial terms, enabling clear interpretation of how individual components contribute to model behavior [

69]. Most importantly, integrating XAI into respiratory sound analysis is essential for improving transparency, ensuring reliability, and strengthening clinical trust [

5]. Meaningful explanations can help clinicians understand why a model labels a segment as crackle, wheeze, both, or normal and support more effective bias detection, while the ultimate goal is to facilitate the translation of AI models from research environments to real-world clinical workflows.

Despite achieving competitive performance, a persistent issue across all SOTA models, including ours, is the relatively low SEN value (

Table 6). Such low sensitivity undermines clinical trust, as both clinicians and patients prioritize avoiding missed disease cases. This indicates that while current models reliably identify normal sounds, accurate detection of the subtle and diverse patterns of pathological events remains a major challenge [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Future work must therefore prioritize strategies that substantially improve sensitivity, such as targeted data augmentation for under-represented classes or loss functions that more heavily penalize false negatives. Additional improvements may come from better data class balancing, careful threshold tuning, and architectural designs for more effectively capturing fine-grained acoustic features. Moreover, multi-center validation using additional datasets and real-world recordings will be essential for assessing generalizability and facilitating translation from laboratory research to clinical practice.