Abstract

The objective of this manuscript is to describe the iterative user-centered development of the Mobile Device Assessment Tool (MoDAT) and to present early usability results involving persons with disabilities and assistive technology (AT) professionals. Smartphones have become a ubiquitous tool for use in everyday life. However, there are limited tools and resources available for AT providers to assess the needs of persons with disabilities in using smartphones. The MoDAT is being developed to help determine the most effective accessibility and AT options for smartphone use by individuals with functional limitations. A user-centered approach has been implemented, including preliminary guidance by advisory committees, focus groups, and usability testing by persons with disabilities and providers who recommend AT solutions. This process has guided the development of a pilot system that can generate personalized recommendations on smartphone device setup and configuration. The MoDAT consists of a series of simulated typical tasks completed on a smartphone application. Individuals complete these tasks to assess their functional capacity, with data regarding their performance gathered and sent to the provider portal. Data is securely stored in the portal for review to help determine accessibility settings and AT that may improve smartphone use. These results and the iterative process are described in this manuscript. Future research will focus on establishing the psychometric properties of the MoDAT as an assessment tool and outcomes.

1. Introduction

Smartphones have become essential assistive technologies for individuals with disabilities, providing critical tools for communication, navigation, and social connection. Despite the integration of robust accessibility features, significant disparities remain in the adoption and use of these technologies among people with disabilities. Research has shown that many individuals with disabilities either lack awareness of available accessibility features or are unsure how to activate and personalize these settings to meet their needs [1,2]. These barriers are further compounded by limited clinician training and the absence of standardized assessment tools to guide clinical decision-making regarding smartphone accessibility [3,4].

National data reveal a substantial digital divide: smartphone ownership among individuals with disabilities in the United States lags behind the general population (72% vs. 88%) [5]. This divide is even more pronounced among those with dexterity, vision, or cognitive impairments, who often face unique challenges, such as navigating touchscreens, discovering relevant features, or accessing device setup [6,7,8]. For instance, persons with vision loss may benefit from screen readers and text-to-speech tools but still face barriers, like inaccessible CAPTCHA verifications or unresponsive applications [2]. Similarly, individuals with cervical spinal cord injury may find that unresolved smartphone accessibility issues compromise their privacy and independence [3]. A key challenge in addressing these issues is the lack of standardized tools to assess functional smartphone proficiency. Existing measures, such as the Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (MDPQ), provide some insight into user confidence and skills but are not designed for clinical assessment or intervention planning [9]. Providers often rely on subjective observation or informal interviews, which may overlook the subtle factors that influence real-world smartphone usability.

To address this gap, we developed the Mobile Device Assessment Tool (MoDAT), a functional assessment platform designed to evaluate the users’ physical interaction capabilities with smartphones and to support clinical decision-making. The MoDAT simulates common smartphone tasks, such as placing a call or sending a message, to assess essential motor skills, including finger isolation, hand–eye coordination, and pressure sensitivity. These simulations generate objective data that can inform the customization of accessibility features and guide training or support needs. The MoDAT includes both a mobile app for user testing and a clinician-facing web portal that provides data visualization and detailed reporting. Importantly, the MoDAT is aligned with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), which emphasizes the interaction between user abilities, environmental factors, and task performance. By simulating real-world scenarios, the MoDAT adopts the ICF’s approach to addressing both activity limitations and participation challenges, offering a systematic way to assess the demands of modern technology use. In addition, the MoDAT supports the ICF’s focus on environmental factors by identifying both barriers and facilitators to smartphone accessibility. The following skills, in particular, may influence the successful and efficient use of smartphone devices.

- Physical CapacityWhen assessing motor skills for mobile phone use, it is important to evaluate key abilities, such as tapping accuracy, swiping, pinch-to-zoom, typing precision, response speed, hand–eye coordination, and the ability to use the device for extended periods. This evaluation should include observing how the user holds the device, navigates the interface, and performs multi-touch gestures. To conduct a thorough assessment, use structured tests or specialized apps to measure speed and accuracy, and gather self-reports from users about any difficulties they encounter. Furthermore, analyze objective data, such as error rates and reaction times, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the user’s dexterity and strength as they relate to effective smartphone use. By systematically studying these touch-based interactions, we can better understand how individuals with motor skill impairments use mobile devices. This insight helps to identify unmet accessibility needs and guides the development of more inclusive touch-screen features [10].

- Cognitive CapacityAssessing cognitive capacity involves evaluating key functions, such as executive functioning, memory, problem-solving, and the ability to learn, skills that are crucial for effective smartphone use. Performance-based assessments, like observing how individuals complete tasks, such as downloading an app or setting an alarm, provide valuable insight into their decision-making and problem-solving abilities. Guided tasks can further reveal a person’s learning capacity by showing how well they retain and apply new information. While smartphone usability has significantly improved, these design enhancements often prioritize the needs of younger, cognitively healthy users, which may not align with the needs of adults with cognitive impairments [11]. By evaluating how individuals interact with smartphones, we can better understand their specific challenges and leverage built-in accessibility features to support engagement with everyday tasks, social connections, and community services.

- Digital LiteracyDigital literacy assessments evaluate a person’s ability, confidence, and familiarity with using digital tools. Practical tasks, such as composing a message or navigating an app, help gauge functional skills, while observational methods provide deeper insight by highlighting the difficulties encountered during real-world activities, like using GPS or taking photos. The digital divide, the growing gap between digitally privileged and disadvantaged populations is influenced by factors such as health literacy, comfort with technology, and interface usability. To help bridge this gap, designers must prioritize universally accessible user interfaces, especially for individuals with limited technical experience or physical abilities [12]. By assessing how someone uses a smartphone, we can better understand their specific challenges and introduce appropriate accessibility features to enhance usability, support independence, and ultimately improve quality of life.

Given the complex nature of smartphone use involving all these skills, our initial approach has focused primarily on physical capacity, but we do recognize that all aspects of functional ability (physical, cognitive, sensory) in conjunction with digital literacy skills must be considered when assessing a person’s mobile device skills and potential needs. This paper presents findings from iterative usability testing and stakeholder feedback involving both assistive technology (AT) service providers and individuals with disabilities. Using focus groups and structured usability sessions, we sought to understand how users experience the MoDAT platform, identify usability issues, and gather suggestions for design refinement and clinical utility.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design: This study utilized a user-centered, multi-phase qualitative research design, incorporating focus groups and usability testing. The approach was informed by recent qualitative studies in assistive technology development, particularly those that have emphasized iterative stakeholder engagement and thematic analysis [13,14,15,16]. The primary objective was to gather feedback from two key user groups, including (1) assistive technology (AT) service providers and (2) persons with disabilities (PwDs), to guide the ongoing development and refinement of the MoDAT system [17]. A user-centered, multi-phase qualitative approach was deliberately chosen instead of quantitative or mixed methods to gather rich, experiential insights directly from key stakeholders, including persons with disabilities and assistive technology service providers. This approach is particularly valuable for uncovering nuanced user needs and guiding the iterative refinement of emerging technologies. Qualitative methods, such as interviews and focus groups, enable researchers to explore social dynamics and real-world processes, capturing lived experiences and practical challenges that are often overlooked by quantitative measures. By supporting a human-centered design process, this method encourages meaningful collaboration between clinical and design experts, helping bridge the gap between user needs and technological solutions. It also accelerates development by providing timely, actionable feedback. By contrast, quantitative methods may fail to reveal complex, context-specific issues critical in early-stage innovation, while mixed methods can introduce unnecessary complexity when the primary goal is to deeply understand user experiences. The content and functionality of the MoDAT were shaped through an ongoing, iterative process that included contributions from a consumer advisory committee (CAG) and subject matter experts. Early prototypes were informed by user feedback obtained through formative interviews and initial field testing. The MoDAT system comprises two core components: the MoDAT mobile app and the MoDAT web portal.

- MoDAT Mobile App: The MoDAT mobile app is installed directly on the user’s smartphone, and is designed to simulate and track common smartphone activities. These simulated tasks are assigned by a clinician or researcher through an online portal prior to the user’s trial. The app mimics real-world interactions to evaluate the user’s functional abilities. Six tasks were developed to reflect typical smartphone use: making a phone call, sending a text message, checking the local temperature, searching for a pizza place, downloading an app, and using map navigation. These tasks were carefully selected to represent key categories of daily smartphone use, including communication, navigation, and app interaction. Each task is designed to assess specific motor functions, such as finger isolation, hand–eye coordination, and strength. The activities reflect challenges that may be encountered by individuals with physical or cognitive limitations in real-life settings.

- MoDAT Web Portal: The portal is a web-based application accessible from any location with an internet connection. It provides clinicians and researchers with a user-friendly interface to manage participants, to assign or modify simulated tasks, and to analyze performance data. The analysis section includes visual representations of each task completed by the participant, along with mapping to show where and how interactions occurred on the screen. These insights help clinicians identify challenges and recommend appropriate accessibility features tailored to the user’s needs. In addition, a visual study flow diagram was developed to illustrate the structure and timeline of consumer advisory group (CAG) input, focus groups, and usability testing throughout this study.

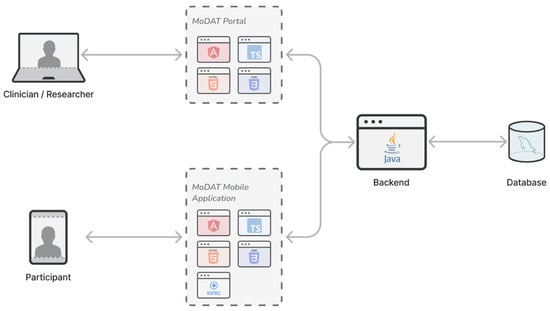

Figure 1 illustrates the MoDAT’s system architecture, designed to support distinct user roles. Clinicians/researchers access system functionalities via the MoDAT portal (built with Angular, TypeScript, HTML5, CSS3), while participants utilize the MoDAT mobile application (Angular, TypeScript, HTML5, CSS3, and Ionic). Data and requests from both the portal and the mobile application are routed to a central Java-based backend. The backend processes these interactions, validates data, and interfaces with a dedicated database for data persistence and retrieval.

Figure 1.

MoDAT System Design.

Participants: Participants were recruited using a combination of purposive and snowball sampling to ensure balanced representation from both key stakeholder groups: assistive technology (AT) professionals (Table 1) and persons with disabilities (PwDs) (Table 2). Purposive sampling was initially used to select individuals who met specific eligibility criteria, including being 18 years or older, English-speaking, and either a clinician or AT professional experienced in recommending smartphone accessibility solutions, or a person with a physical or cognitive disability who currently uses or has considered using a smartphone. Recruitment was conducted through professional networks, disability advocacy organizations, and clinical contacts, allowing the research team to reach participants with a wide range of disabilities (e.g., mobility, vision, cognitive impairments) and professionals from diverse clinical and AT backgrounds (e.g., occupational therapy practitioners, assistive technology professionals). To further enhance diversity, snowball sampling was employed by inviting initial participants to refer eligible colleagues or peers who might represent different disability experiences or professional perspectives. This combined approach supported the inclusion of varied viewpoints and strengthened the overall representativeness of the sample across both stakeholder groups. All participants provided informed consent prior to involvement in this study.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Assistive Technology (AT) Professional Participants (N = 14), Please note that most categories are not mutually exclusive.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Persons with Disabilities (PwDs) (N = 7).

Procedures: The iterative development of the MoDAT was informed by the ICF framework [11]. Development began with formative consultations with an advisory committee composed of people with lived experience of disability/disabilities. All procedures involving data collection with PwDs were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Pittsburgh prior to initiation. This included both the formal focus group sessions and subsequent usability testing with PwDs. Data collection was conducted in three main phases:

- Phase 1—Consumer Advisory Committee (CAG): As part of the wireless rehabilitation engineering research, CAG was gathered to support the iterative development of the Mobile Device Assessment Tool (MoDAT). While these individuals were not enrolled as research participants, their lived experiences with physical disabilities and AT provided valuable insights into real-world usability challenges and feature needs. Meetings conducted in August and September 2022 included diverse CAG members who rely on mobility aids, voice control, assistive touch, and mounting systems to interact with smartphones.

- Phase 2—Focus Groups: Separate focus groups were held with AT professionals and PwDs to explore experiences with smartphone technology and reactions to a live demonstration of the MoDAT prototype. Semi-structured guides included questions on barriers to smartphone use, awareness and usage of accessibility features, and perceived utility of the MoDAT features. The focus group sessions, conducted in January and February 2024, were approximately 90 min in duration, and were recorded and transcribed.

- Phase 3—Usability Testing: Participants then completed guided task simulations using the MoDAT application on smartphones or tablets. The tasks simulated real-world interactions, such as placing a call or conducting a web search. Participants were encouraged to use “think aloud” techniques, and follow-up interviews captured impressions of interface usability, performance feedback, and system design. Observational field notes were recorded by research team members. Usability testing with AT professionals is ongoing under the same IRB protocol and these results are not included in the present manuscript.

Task Performance and Data Collection: Task performance was evaluated through qualitative observations, task completion status, and researcher field notes. Future versions will incorporate structured performance metrics, such as completion time and error rates.

Data Analysis: All qualitative data, including transcripts, observational notes, and open-ended responses, were analyzed using thematic analysis. Coding was conducted independently by four researchers and reconciled through iterative team meetings. An inductive–deductive coding strategy was used: initial codes were derived from participant responses (inductive), then organized using the ICF-based deductive categories, such as ‘Body Functions’, ‘Environmental Factors’, and ‘Activities’. Discrepancies were resolved in collaborative coding meetings. The themes were refined collaboratively and validated against the data.

3. Results

3.1. Consumer Advisory Committee Feedback

Detailed notes captured the feedback from six members of the CAG. A qualitative analysis revealed key themes which emerged across the six smartphone tasks used in the MoDAT:

- Device Positioning and Input Challenges: Users reported that mounting and positioning the phone is critical to effective use, particularly for those with limited upper-limb mobility or spasms. Some participants used dual mounts or Velcro to stabilize the device. Voice control and adaptive pointers (e.g., joystick or grid-based control systems) were frequently used, though often supplemented by trial-and-error workarounds.

- Voice Control and Accessibility Features: Participants described voice control as both empowering and inconsistent. Speech impairments and background noise often reduced accuracy. Custom voice commands, grids, and labeling features helped some users streamline access, but limitations remained in tasks requiring fine gestures or system swipes. Few users relied on built-in screen readers or switched access consistently.

- Functional Task Difficulties: Tasks, such as placing a call, sending a text, and navigating apps, presented barriers due to imprecise screen taps, limited grip, or poor voice recognition. Multitasking, such as switching apps or using Apple Pay at checkouts, introduced further challenges. Long-press gestures and dragging apps were particularly difficult for individuals with reduced dexterity or sensation.

- User Strategies and Workarounds: Users reported customizing their devices through grid systems, joystick interfaces, screen mounting at optimal angles, and syncing tasks across devices (e.g., smart speakers, desktops). Some described building their own macros or voice scripts to execute multi-step commands. Preferences for assessments included keeping tasks under 30 min, integrating visual aids, and providing clear instructions.

- Recommendations for the MoDAT Development: CAG members emphasized the importance of flexible input modalities, simplified screen navigation, support for voice and pointer-based control, and the ability to bypass or repeat tasks as needed. They also advocated for realistic task simulations and designs that consider personal device setups and varying functional capacities.

This advisory input directly informed the design refinements and accessibility considerations integrated into the MoDAT app and provider portal. Stakeholder feedback ensured the assessment was inclusive of a range of physical interaction strategies and representative of real-world challenges encountered by individuals with disabilities.

3.2. Focus Groups

3.2.1. Assistive Technology Providers

This focus group comprised 14 assistive technology (AT) professionals, predominantly female (n = 11) and White/Caucasian (n = 13). Participants represented a diverse range of clinical roles, including certified occupational therapy assistants (n = 7), AT professionals (n = 6), and one occupational therapist. Most were employed full-time (n = 13) in community-based settings and had an average of 9.8 years of experience. The majority served adults (n = 13) and older adults (n = 14) with physical disabilities, neurodegenerative diseases, or mental health diagnoses. Detailed demographic data are presented in Table 1 below:

Four core themes emerged from the focus group held with AT professionals:

- (1)

- Observation-Based Assessment is InadequateClinicians emphasized the difficulty of accurately assessing clients’ smartphone skills through observation alone, particularly given the small screen size and rapid interaction required. They noted that clients often omit or fail to verbalize their challenges, making objective tools like the MoDAT particularly valuable.“You’re trying to observe, you’re trying to catch a lot of information… and it’s not ideal.”

- (2)

- Digital Literacy and Training GapsProviders frequently encounter clients who lack basic digital literacy. Even when accessibility features are available, clients may be unaware or unsure of how to activate and use them. This challenge was compounded by rapidly evolving features across platforms.“How do you know it’s there unless you’re constantly looking?”

- (3)

- Interface Complexity and Feature DiscoverabilityParticipants reported that clients struggle to locate or understand features, such as voice control, app downloads, or keyboard variations. Password management and confusion between apps and accessibility features were also cited as frequent barriers.“It’s amazing—some people don’t know how to swipe to answer a phone.”

- (4)

- Recommendations for the Design and Use of the MoDATProfessionals endorsed the MoDAT tool’s structure, noting that the simulated tasks reflected real-world needs. They appreciated the task progression (e.g., from dialing a phone to searching online) and suggested optional additions like camera use, external button functions, and soft resets for assessment flexibility.“You want to see how somebody uses this in real life, but… also capture it objectively.”

3.2.2. Persons with Disabilities (PwDs)

A total of seven individuals with disabilities participated in the focus group and usability testing sessions. Participants were predominantly male (n = 4) and White/Caucasian (n = 5), with one identifying as Black or African American, and one reporting a multiracial or “Other” background. One participant identified as Hispanic or Latino, while the remainder identified as non-Hispanic. Employment status varied among the group: one individual was employed full-time, two were employed part-time, and four reported they were not currently employed. Annual household income was reported as USD 10,000 or less by two participants and between USD 10,000 and USD 39,999 by five participants.

Regarding technology use, most participants rated themselves as either “comfortable” (n = 5) or “very comfortable” (n = 2) with using technology. One participant indicated prior experience inventing something new or innovative. All participants expressed strong interest in technology, with three “strongly agreeing” and four “agreeing” that they were passionate about exploring new technologies and improving existing products or processes. In terms of smartphone use, participants reported engaging in a range of activities including texting and calling (n = 7), using the camera (n = 6), accessing email (n = 6), using GPS or map features (n = 6), and social media (n = 5). Several also reported using apps for entertainment, education, or task management. Self-reported functional limitations included upper extremity impairments (n = 3), difficulties with dexterity (n = 4), and cognitive or memory-related challenges (n = 2). These characteristics underscore the importance of accessible, customizable smartphone solutions such as those targeted by the MoDAT platform.

Participants who were PwDs offered detailed insight into their experiences using mobile devices, highlighting both empowering and frustrating aspects of smartphone technology. Five major themes emerged as follows:

- (1)

- Smartphones are Essential Tools for IndependenceParticipants reported using smartphones for a broad range of tasks, including communication, navigation, home automation, education, document management, and telehealth. Many described their devices as essential for day-to-day living and decision-making.“My phone has empowered me… it’s educated me so much.”

- (2)

- Challenges with Accessibility Settings and Feature UniformityPwDs often experienced difficulties locating and enabling appropriate accessibility features. Inconsistencies across apps and devices or updates that reset user preferences created frustration and confusion.“Every app is different. Nothing is uniform.”

- (3)

- Learning Preferences and Support NeedsParticipants expressed strong preferences for how they learned to use features—many favored step-by-step video demonstrations or peer-generated tutorials (e.g., YouTube, listservs) over traditional manuals or written guides.“For me, I’m a very visual learner… I like to go step by step.”

- (4)

- Physical Limitations in Touchscreen InteractionSeveral individuals noted difficulties with multi-step gestures, such as pinch-to-zoom or holding multiple buttons. These challenges were particularly pronounced among users with fine motor impairments or muscle weakness.“If there’s something that needs two fingers, my hands don’t always work simultaneously.”

- (5)

- Barriers to Voice Control and Input AccuracyVoice input features were helpful but often limited by speech clarity, accent, or background noise. Participants emphasized the need for greater tolerance of variation and alternative options for those with atypical speech.“If you don’t speak perfectly, it’s challenging. Who speaks perfectly?”

Usability Testing Observations of PwDs

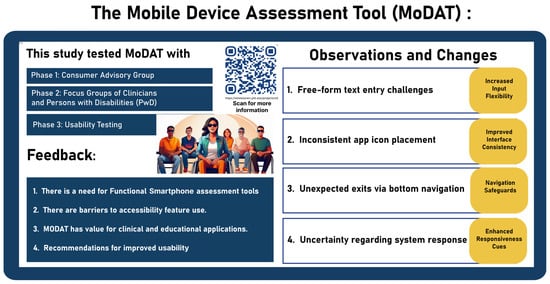

Structured usability testing reinforced many themes from the usability testing sessions. While most participants were able to complete assigned tasks with minimal assistance, some encountered difficulties interpreting system feedback or navigating task workflows. Four of the PwDs with physical disabilities also participated in usability testing of the MoDAT application. Key usability issues and revisions included the following:

- Free-form text entry problems: Initial task logic required exact wording (e.g., “best pizza in Pittsburgh”). This rigidity led to user frustration when semantically correct alternatives were marked incorrect.

- Inconsistent app icon placement across tasks: Some icons were shown only when they are needed, this led to confusion and users thinking the new icon they are seeing for the first time to be the correct icon they needed to tap.

- Unexpected exits via bottom navigation: Some participants unintentionally left the simulation.

- Uncertainty about system response: Users sometimes did not know if their input had been received.

In response to usability challenges identified during initial testing with these four PwDs who we asked to complete the six simulations, the MoDAT application underwent a series of targeted updates, demonstrating a commitment to user-centered design and ecological validity. Major improvements included the following:

- Increased input flexibility: To better reflect real-world digital interactions and address user’s frustration observed with the initial strict input requirements, most of the input related tasks, such as searching, were modified. The system now accepts synonyms, typos, or alternative phrasing (e.g., “sixteen” vs. “16”; partial matches for “Our Mother’s Pizza”), as demonstrated by the pseudocode comparison in Table 3. The integration of SerpAPI also enabled more realistic search behavior and the ability to select results that are semantically similar, simulating Google-like responsiveness rather than relying on exact string matching.

Table 3. A comparison of string-matching algorithms, demonstrating a strict, exact-match approach (“Before”) and a more flexible method for both single and multi-word inputs (“After”).

Table 3. A comparison of string-matching algorithms, demonstrating a strict, exact-match approach (“Before”) and a more flexible method for both single and multi-word inputs (“After”).

- Navigation safeguards: Although the app could not disable the bottom navigation bar, device-level screen pinning was activated to prevent premature exits during tasks. This measure aimed to keep the user on the app and maintain the completeness and reliability of the collected data

- Improved interface consistency: Task-related icons and apps were standardized across scenarios to reduce confusion and to make sure the reason they are picking the icon is because of their own reasoning.

- Enhanced responsiveness cues: A loading animation was added to reduce uncertainty and to prevent repeated button presses when operations took a few seconds to complete.

- Expanded monitoring tools: A screen recording feature was introduced to enable post-session review. While valuable its deployment encountered technical inconsistencies across devices, potentially related to device processing power, which caused the app to force close.

Each modification was driven directly by user feedback and validated through follow-up testing, enhancing both the realism of the simulation and its clinical utility. Figure 2 provides an at-a-glance visual summary of the implemented improvements.

Figure 2.

MoDAT Improvements.

4. Discussion

The iterative development and evaluation of the MoDAT revealed valuable insights into the accessibility needs, functional barriers, and usability preferences of both AT providers and PwDs. The combination of focus groups and usability testing confirmed the importance of using a user-centered design framework to ensure that emerging assessment tools like the MoDAT are both clinically relevant and contextually appropriate. Unlike existing tools, such as the Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (MDPQ), which primarily assess users’ self-reported confidence, the MoDAT offers function-based simulations of physical smartphone interactions. Participants with disabilities in this study represented a range of functional challenges, including upper extremity impairments, limited dexterity, and cognitive difficulties. These conditions can significantly impact smartphone use. Despite identifying as generally comfortable with technology, several participants reported encountering obstacles in executing basic mobile tasks due to inconsistent touchscreen responsiveness, fine motor limitations, or difficulties navigating complex interfaces. These findings are consistent with prior studies that emphasize a persistent digital divide and the need for individualized technology solutions among users with functional impairments [1,3,6,7]. The prevalence of workarounds, such as using adaptive mounts, joysticks, or customized voice commands, illustrates how users must adapt their environments and devices in the absence of optimized accessibility support. Feedback from AT providers underscored similar concerns. Providers emphasized the lack of formalized tools for assessing clients’ mobile technology needs and highlighted the reliance on informal interviews or observational strategies. Many expressed a need for more structured, data-driven assessments to support clinical reasoning and documentation. These concerns echo broader calls within the literature for standardized approaches to evaluating functional smartphone use and tailoring accessibility recommendations accordingly [4,9].

Despite these strengths, this study has several limitations. The small and regionally concentrated sample may limit the generalizability of the findings. While participants reflected diverse clinical and lived experiences, further testing is needed with a broader population, including individuals with sensory impairments, limited digital literacy, or limited English proficiency. Additionally, although the present study focused on the physical and cognitive aspects of smartphone use, future iterations of the MoDAT should expand to incorporate sensory accessibility and learning support features. Furthermore, this study did not include quantitative measures of user performance improvement over time or direct tracking of accessibility feature adoption following the MoDAT recommendations. While these early rounds of usability testing offered important observational insights and participant feedback, it lacked standardized performance metrics, such as task completion time, error rates, or system usability scale (SUS) scores. Future studies will incorporate pre/post-testing designs or longitudinal data collection to assess the impact of the MoDAT on accessibility feature adoption and smartphone proficiency. In addition, integrating analytics from the provider-facing portal—such as configuration changes based on the MoDAT reports—could help validate the tool’s clinical utility and inform real-world practice.

In conclusion, the findings of this study affirm that the MoDAT is a promising tool for assessing smartphone accessibility needs among individuals with disabilities. Its development demonstrates the feasibility of applying user-centered principles to create meaningful, scalable assessment technologies. Future research will focus on validating the tool’s psychometric properties, such as test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and convergent validity with established measures, while also expanding its use across broader clinical contexts and user populations. Present efforts are focused on gathering normative data for completion of the tasks from users without disabilities to allow for specific guidance in determining thresholds for performance related to accuracy and efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.F. and A.S.; methodology, A.D.F., A.S. and F.A.I.; formal analysis, F.A.I. and A.D.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.F., R.B.O. and F.A.I.; writing—review and editing, A.D.F., A.S., R.B.O. and F.A.I.; funding acquisition, A.D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this work is provided by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) under the grant #90REGE0016. NIDILRR is part of the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh (protocol code STUDY23040060, approved on 20 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained by contacting the authors directly.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the individuals who participated in this study, whose insights and experiences were instrumental to the development and evaluation of the MoDAT system. We also extend our sincere appreciation to Nia Monteiro, Chapin Graham, and Lauren Mochnal for their valuable contributions to data collection and analysis while employed as part-time research assistants and completing their occupational therapy doctoral (OTD) degrees.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors are employed at the University of Pittsburgh through the Health Information Management Department in the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. Andrea Fairman is also employed by Carlow University in College of Health and Wellness, Occupational Therapy Department. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wu, J.; Reyes, G.; White, S.C.; Zhang, X.; Bigham, J.P. When can accessibility help? An exploration of accessibility feature recommendation on mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 18th International Web for All Conference (W4A’21), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–20 April 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senjam, S.S.; Primo, S.A. Challenges and enablers for smartphone use by persons with vision loss during the COVID-19 pandemic: A report of two case studies. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 912460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong-Wood, R.; Messiou, C.; Kite, A.; Joyce, E.; Panousis, S.; Campbell, H.; Lauriau, A.; Manning, J.; Carlson, T. Smartphone accessibility: Understanding the lived experience of users with cervical spinal cord injuries. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 19, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botelho, F.H.F. Accessibility to digital technology: Virtual barriers, real opportunities. Assist. Technol. 2021, 33 (Suppl. 1), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, A.; Atske, S.; Pew Research Center. Americans with Disabilities Less Likely Than Those Without to Own Smartphones, Computers. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/09/10/americans-with-disabilities-less-likely-than-those-without-to-own-some-digital-devices/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Boman, M.; Bowman, M.; Robinson, J.; Kane, S.K. How smartphones fail users with mild-to-moderate dexterity differences. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS’23), New York, NY, USA, 22–25 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Gulliksen, J.; Gustavsson, C. Disability digital divide: The use of the internet, smartphones, computers and tablets among people with disabilities in Sweden. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaForce, S.; Bright, D. Are we there yet? The developing state of mobile access equity. Assist. Technol. 2022, 34, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, N.A.; Boot, W.R. A new tool for assessing mobile device proficiency in older adults: The Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 37, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trewin, S.; Swart, C.; Pettick, D. Physical accessibility of touchscreen smartphones. In Proceedings of the 15th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Bellevue, WA, USA, 21–23 October 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Wang, Q.J.; Stolwyk, R.; Ponsford, J. Do smartphones have the potential to support cognition and independence following stroke? Brain Impair. 2017, 18, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donawa, A.; Powell, C.; Wang, R.; Chih, M.; Patel, R.; Zinner, R.; Aronoff-Spencer, E.; Baker, C. Designing survey-based mobile interfaces for rural patients with cancer using Apple’s ResearchKit and CareKit: Usability study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e57801. Available online: https://formative.jmir.org/2024/1/e57801 (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Morris, L.; Messina, K.; Fairman, A. Providing mainstream smart home technology as assistive technology for persons with disabilities: A qualitative study with professionals. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 18, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairman, A.D.; Ojeda, A.; Morris, L.; Goodwin, R.; Thompson, M.E. User-centered design of mobile health system to support transition-age youth with epilepsy and their caregivers—Phase I: Focus groups. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7411515340p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, R.; Fairman, A.D.; Karavolis, M.; Sullivan, C.; Parmanto, B. A qualitative exploration of client and caregiver needs and preferences for self-management using mHealth applications. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indradhirmaya, F.; Monteiro, N.; Morris, L.; Fairman, A.; Saptono, A. Mobile Device Assessment Tool (MoDAT) to capture functional capacity of persons with physical and cognitive disabilities. In Proceedings of the RESNA 2023 Annual Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 24–26 July 2023; Available online: https://www.resna.org/sites/default/files/conference/2023/AccessAndAccommodations/87_Indradhirmaya.html (accessed on 1 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).