Abstract

Hospital in the Home (HITH) programs are emerging as a key pillar of smart city healthcare infrastructure, leveraging technology to extend care beyond traditional hospital walls. The global healthcare sector has been conceptualizing the notion of a care without walls hospital, also called HITH, where virtual care takes precedence to address the multifaceted needs of an increasingly aging population grappling with a substantial burden of chronic disease. HITH programs have the potential to significantly reduce hospital bed occupancy, enabling hospitals to better manage the ever-increasing demand for inpatient care. Although many health providers and hospitals have established their own HITH programs, there is a lack of research that provides healthcare executives and HITH program managers with management models and frameworks for such initiatives. There is also a lack of research that provides strategies for improving HITH management in the health sector. To fill this gap, the current study ran a systematic literature review to explore state-of-the-art with regard to this topic. Out of 2631 articles in the pool of this systematic review, 20 articles were deemed to meet the eligibility criteria for the study. After analyzing these studies, nine management models were extracted, which were then categorized into three categories, namely, governance models, general models, and virtual models. Moreover, this study found 23 strategies and categorized them into five groups, namely, referral support, external support, care model support, technical support, and clinical team support. Finally, implications of findings for practitioners are carefully provided. These findings provide healthcare executives and HITH managers with practical frameworks for selecting appropriate management models and implementing evidence-based strategies to optimize program effectiveness, reduce costs, and improve patient outcomes while addressing the growing demand for home-based care.

1. Introduction

The healthcare sector has been facing various challenges over the past years, such as changes in demand, technology, budgetary constraints, staffing, etc. [1]. These challenges have necessitated a re-evaluation of traditional care models and the exploration of innovative solutions. To cope with these challenges, a new trend has emerged, often implying a shift towards new care models.

The Hospital in the Home (HITH) care model is one of these new models. HITH commonly refers to providing patients with hospital-level care in their own homes [2,3]. HITH is also known as Home Hospitalization, Medical Home Care, Hospital Without Walls [4], Hospital at Home [2,5], or as Virtual Hospital [6]. This new model of care aims to bridge the gap in care between hospitals and the community by delivering hospital services directly to patients’ homes. Advances in technology have made it possible for certain medical procedures, once limited to hospital settings, to be performed in the patient’s home [1]. Before examining existing approaches, it is important to clarify key terminology. Governance models refer to structured approaches that define accountability, decision-making processes, and operational oversight of HITH initiatives. Frameworks represent the systematic organization of components that facilitate HITH implementation and management. General models refer to operational HITH approaches that focus on service delivery and care coordination, regardless of whether they target specific clinical domains or offer broad applicability across healthcare settings. Virtual models refer to HITH approaches that emphasize technology-mediated care delivery with minimal in-person components, relying primarily on remote monitoring, telehealth platforms, and digital communication systems. These distinctions are essential for understanding the different approaches to organizing and managing HITH programs discussed in this review.

Globally, the health sector has been under significant pressure with a growing population and limited infrastructure available to hospitalize patients. These factors collectively highlight the necessity for alternative care models that can alleviate the strain on traditional hospital infrastructure. According to Pandit et al. [7], over $1 trillion was spent on hospital services in the US in 2021, with expected increases in the coming years that highlight the need for exploring more efficient care delivery models. In addition to the costs, there has been a decreasing trend in the number of available hospital beds per person over the past years. For example, according to the World Bank Group, the number of available hospital beds per 1000 people in the European Union was 6.5 in 2000 and decreased to 4.6 in 2018. Similarly, in Australia, the number was 7.9 per 1000 people in 2000 and decreased to 3.8 in 2016 [8]. This shortage in available hospital beds can be covered by HITH models of care.

The healthcare sector has experienced a significant increase in patients who receive medical care at home. This increase is driven by different factors such as the growing population of elderly and chronically ill individuals who require health services, the limited availability and accessibility of acute and sub-acute in-patient services in some areas, and technological and clinical care advancements that enable the provision of medical care in home settings [4], and increased annual cost of hospital care [7]. This reduction in hospital bed availability underscores the critical need for scalable home-based care solutions like HITH.

Given the key role that new care models, such as HITH, can play within the healthcare sector, several studies have examined different aspects of HITH. These include the effectiveness and safety of HITH models [1,9,10,11], the experience of patients and caregivers with HITH programs [12,13], the technology use in HITH programs [14], ethical issues in HITH programs [15], and virtual services [16]. While previous systematic reviews have examined HITH effectiveness, safety, and patient experiences, they have not synthesized governance models and management frameworks that healthcare executives need to successfully implement these programs. To address this gap in the literature, the current study addresses the following two research questions:

- What management models and frameworks have been proposed for HITH initiatives?

- What strategies have been proposed for managing HITH initiatives?

Addressing the above-mentioned research questions is important for healthcare executives and managers. By having best practice models and frameworks for managing HITH initiatives, healthcare executives can design governance systems that allow effective and efficient management of HITH programs. Furthermore, having best practice strategies for HITH programs allows healthcare providers to tailor their HITH programs to the specific contexts they deal with and develop a HITH program compatible with the demand and infrastructure limitations they face. For hospital executives, these models provide an overview of the potential HITH program, its main components, and the arrangement of those components. This can help them develop a more efficient process for their programs. HITH program managers can take advantage of the extracted strategies to improve their current practices. These insights can improve their patient outcomes and streamline the operations of their programs.

Following this introduction section, the methodology employed in this systematic literature review project is outlined. Subsequently, the research findings are presented. Finally, a detailed discussion of the implications of these research findings for practitioners is provided.

2. Methodology

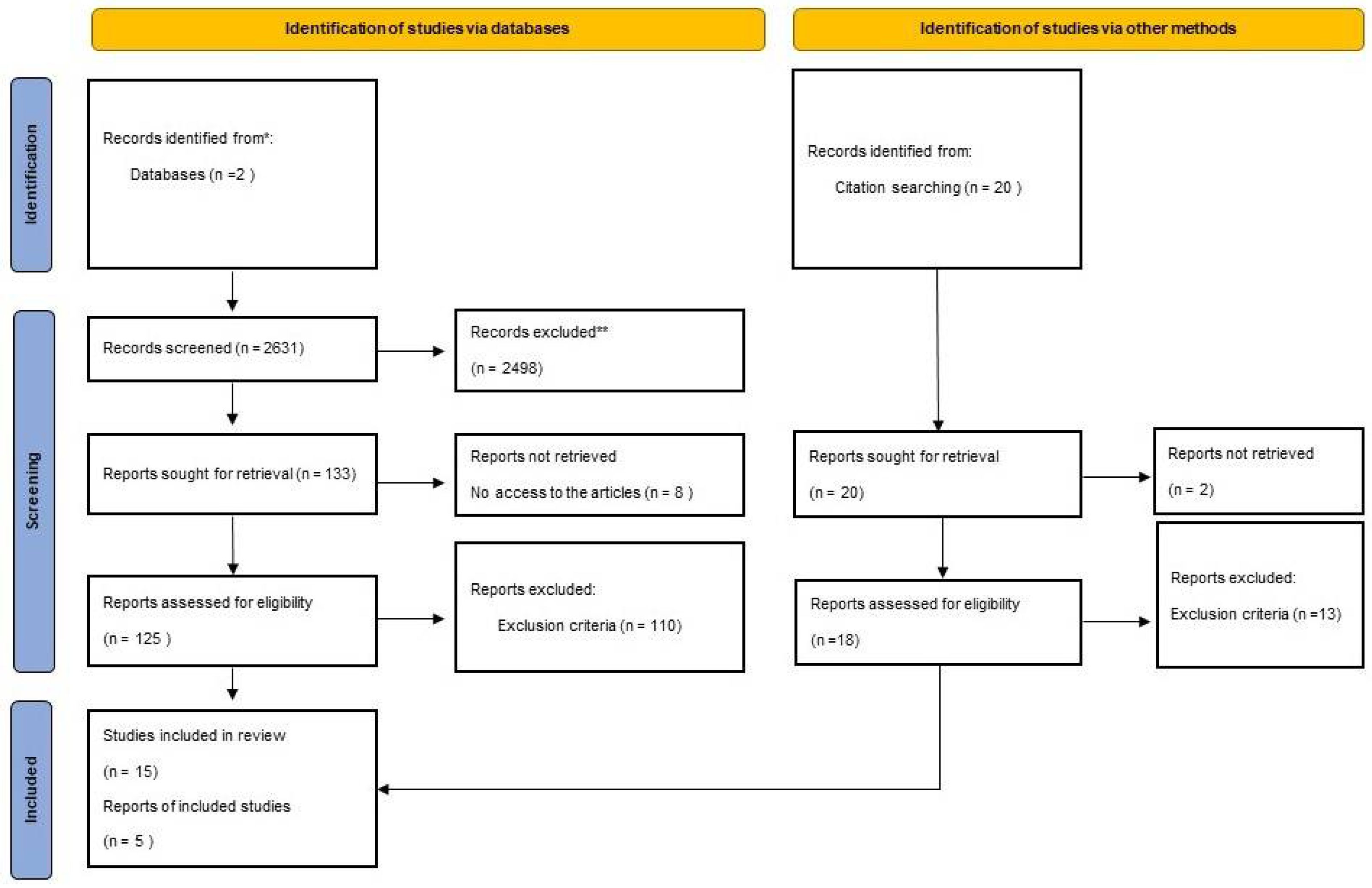

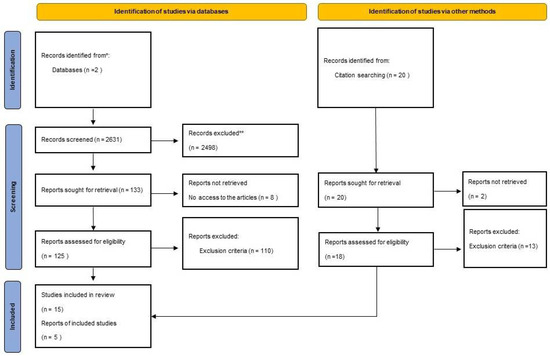

This systematic review employed PRISMA methodology to provide a comprehensive and transparent synthesis of existing governance and management models and strategies for HITH programs, addressing a critical knowledge gap for healthcare executives implementing these services. While quantitative analyses of clinical outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and safety profiles have been conducted in previous reviews [1,9,10,11], our research specifically targets the governance and management aspects that enable successful HITH implementation. Rather than focusing on statistical measures of service performance, this review synthesizes organizational models and implementation approaches to guide executives in designing HITH programs appropriate to their specific contexts. This qualitative synthesis approach is particularly valuable given the heterogeneity of HITH implementations across healthcare systems and the need for adaptable governance frameworks that can be tailored to various organizational environments. The review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [17], using pre-specified search strategies, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data extraction methods. The study selection process is shown in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram. Data synthesis followed PRISMA recommendations for systematic reviews with qualitative synthesis, incorporating thematic analysis of extracted models and strategies. All critical review processes were documented to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. * exclusion during the initial screening phase. ** exclusion at the full-text review stage.

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search on ScienceDirect and Scopus was conducted on 14 April 2024. Search terms and criteria for inclusion/exclusion were determined by the first and second authors of this study before starting data collection. The search was restricted to the top 10 Q1 journals in each database, which had the highest number of papers retrieved through the search strings (See Table 1), and only included full-text research articles in English. As the emergence of at-home models of care goes back to 1947 [18], this study included all years without any year limitations. The results were then filtered by subjects to exclude irrelevant subjects such as agricultural and biological sciences, engineering, environmental science, biochemistry, genetics, and molecular biology. One additional search was conducted to identify the most relevant studies through citation searching.

Table 1.

Top 10 journals in each database based on the number of published articles.

2.2. Search Key Words

ScienceDirect and Scopus were used to search the keywords. Depending on the search services offered by the relevant search engines, the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the journal articles were searched using the terms listed below. Since Scopus has no limitations in terms of search strings, more thorough terms were used in this database, while ScienceDirect allows a limited number of terms.

- Search Keywords in Scopus:

(“hospital in the home” OR “HITH” OR “hospital at home” OR “HaH” OR “virtual care” OR “virtual hospital” OR “acute home care” OR “hospital-based home care” OR “hospital without walls” OR “sub-acute home care” OR “RITH” OR “rehab in the home” OR “Gem at home” OR “ESD” OR “Neuro rehab at home” OR “early supported discharge” OR “geriatric evaluation management”) AND (“model” OR “framework” OR “taxonomy” OR “big picture” OR “management” OR “leadership” OR “governance” OR “operational governance” OR “clinical governance” OR “operational leadership” OR “clinical leadership”)

- Search Keywords in ScienceDirect:

(“hospital in the home” OR “HITH” OR “hospital at home” OR “HaH” OR “virtual care”) AND (“model” OR “framework” OR “management” OR “governance”)

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The criteria for including materials in our systematic review were determined by specific inclusion and exclusion standards. The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) any governance models for HITH; (2) any governance frameworks for HITH; (3) any HITH model of care; (4) any management or governance strategies for HITH; and (5) virtual care models. The exclusion criteria for this study were: (1) quality evaluation of HITH models; (2) safety evaluation of HITH models; and (3) financial evaluation of HITH models.

Given the focus on identifying governance models and management strategies rather than evaluating intervention outcomes, we did not employ a formal quality assessment tool for the included studies. Instead, our analysis focused on extracting and synthesizing governance structures, management approaches, and implementation strategies regardless of study design. This approach is appropriate for our research questions, which sought to identify and categorize existing models rather than assess their comparative effectiveness.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The data extraction and synthesis stage involved the extraction of data in response to the two research questions raised at the end of the introduction section. After conducting searches in two databases, the datasets were imported to Covidence (a systematic review management software) for screening. After the screening process, a total of 20 papers were included for data extraction and analysis. The process of data analysis was conducted by one investigator and controlled by a senior investigator. Two types of data were extracted from the included studies: (1) the existing frameworks and models for managing and governing different sorts of HITH initiatives; and (2) strategies for better developing and managing HITH initiatives. Relevant outcomes were extracted from the reported findings, discussions, and tables in the reviewed studies through content analysis. Microsoft Excel was used for entering the data, undertaking descriptive analysis, and drawing diagrams.

2.5. Data Analysis

The results from the included papers were organized into groups, analyzed based on recurring themes, and then summarized in a narrative format. In response to the first research question, the related findings were summarized narratively. For the second research question, themes were used to categorize the findings into groups. The findings are indicated in two separate Section 3.1 and Section 3.2.

3. Results

This systematic review identified nine management models and 23 implementation strategies from 20 studies that met our inclusion criteria. The models were categorized into three distinct types: one governance model explicitly addressing accountability structures, six general models focusing on operational service delivery, and two virtual models emphasizing technology-mediated care. The 23 strategies were grouped into five categories: referral support (3 strategies), external support (3 strategies), care model support (6 strategies), technical support (6 strategies), and clinical team support (5 strategies). These findings directly address our two research questions and provide healthcare executives with structured frameworks for HITH implementation.

The primary search strings identified 2631 records, and 20 additional records were identified through citation searching. Of these, 143 full-text articles were fully reviewed, and 20 papers met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). The included articles were regarding encompass governance framework (n = 1), HITH model of care (n = 6), virtual initiatives (n = 2), and strategies regarding managing HITH programs (n = 11). To streamline the results, the first Section 3.1 indicates the HITH governance framework, management models, and virtual initiatives, and the second Section 3.2 indicates the HITH management strategies extracted from the literature.

3.1. HITH Management Models

To answer the first research question, nine articles were found. Out of them, one article provides a governance model for a particular HITH initiative, six articles propose general models for HITH initiatives, and two articles are regarding virtual care initiatives. Proposed HITH models reviewed in this study, on the one hand, are divided into two types, with respect to their pathways: Early supported discharge (ESD) or step-down, and admission avoidance (AA) or step-up. ESD or step-down aims to accelerate the discharge of admitted patients, thus partially substituting hospital care. AA or step-up directly admits patients into HITH, avoiding physical contact with the hospital, or through direct admissions from the emergency room [11,19]. On the other hand, these models are divided into virtual, in-person, or hybrid based on the way care is delivered. A description of each model is given below. Table 2 provides an overview of these studies.

Table 2.

Models extracted in response to the first research question.

The categorization distinguishes between governance models that explicitly address accountability structures and decision-making processes [20], general models that focus on operational frameworks for service delivery regardless of clinical specialization [21,22,23,24,25,26], and virtual models that emphasize technology-mediated care delivery [27,28]. While only one governance model was identified in our review, this limitation highlights a significant gap in the literature regarding explicit governance frameworks for HITH programs, suggesting that most existing models focus on operational rather than governance aspects.

3.1.1. Governance Model

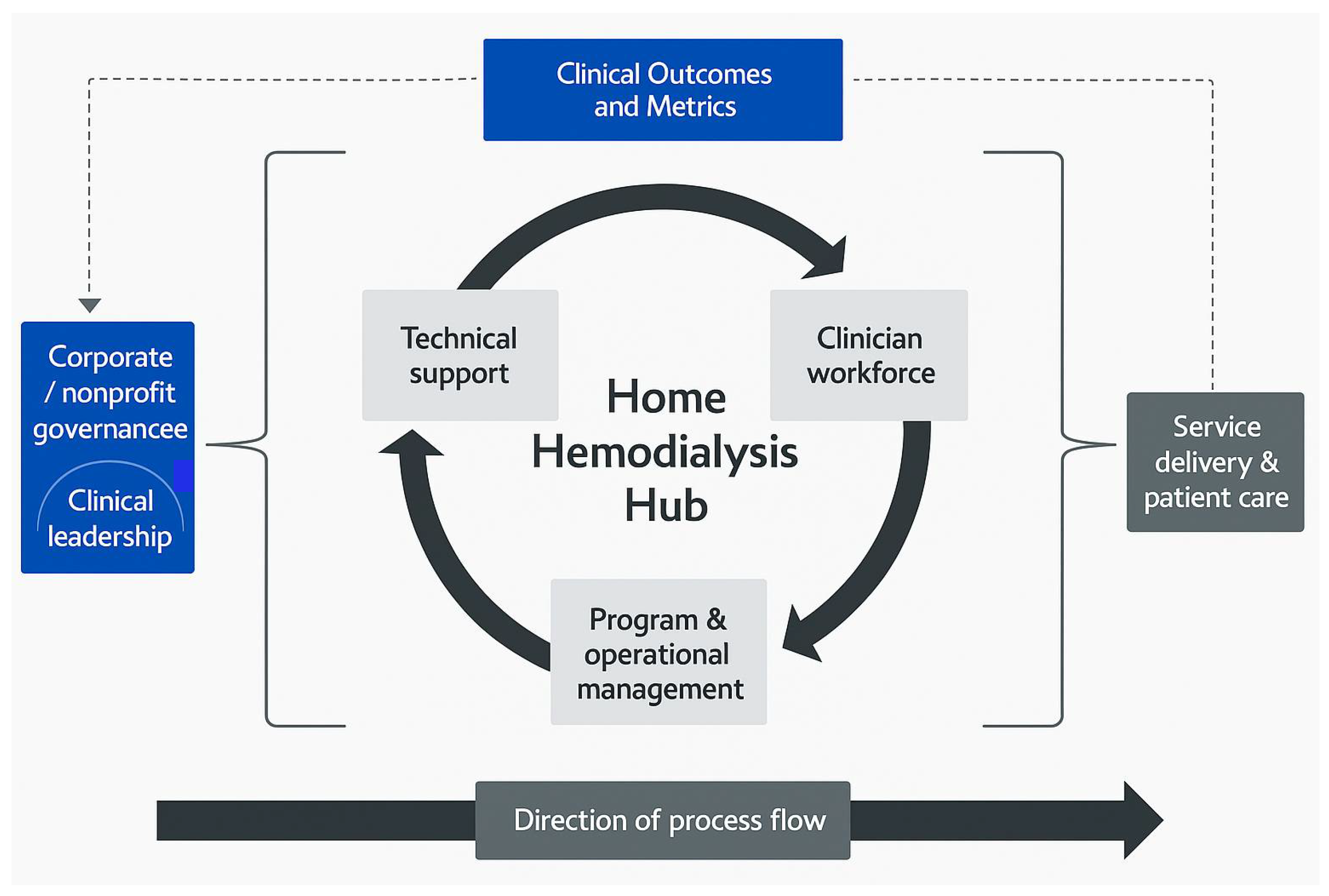

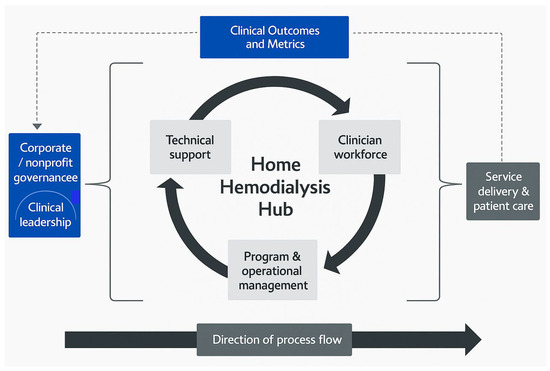

Marshall et al. [20] suggested a governance model for HITH initiatives, with particular focus on Home Hemodialysis programs. The governance framework they proposed makes clear the accountability of each group involved in programs, as well as linkages around all critical processes that may impact clinical outcomes. What they suggested as the top of the governance structure is either corporate or nonprofit bodies that exercise final authority. In the case of having corporately-governed programs, boards of directors are in charge in the sense of determining policies and running the programs to achieve corporate goals. Boards of directors also determine the nature of relationships among directors, management, and stakeholders, such as regulators, financiers, suppliers, employees, patients, the community at large, etc. In the case of having nonprofit-governed programs, boards of trustees or governmental groups are in charge. In the proposed model, clinicians have a crucial role to play in the governance of Home Hemodialysis programs. Management governance is typically hierarchical and responsible for business and regulatory requirements. In contrast, clinical governance follows a more decentralized manner and needs the expertise and involvement of healthcare professionals across all levels within the home programs. The coexistence of both management governance and clinical governance is emphasized, as together they allow patient care and outcomes to remain the main focus when providing clinical services and making decisions. According to Marshall et al. [20], the governance framework for Home Hemodialysis programs comprises four main components, including leadership, clinician workforce, program management, and technical support. Figure 2 illustrates this framework.

Figure 2.

Framework for the governance of home hemodialysis program [20].

The Home Hemodialysis Hub framework presents several strengths, including clear delineation of accountability across corporate/nonprofit bodies, management, and clinical teams, which facilitates transparent governance [20]. The model emphasizes the coexistence of management and clinical governance, ensuring patient care remains the central focus. However, limitations include its narrow specificity to hemodialysis programs, potentially limiting broader applicability to other HITH services. Implementation challenges may arise when attempting to balance hierarchical management structures with decentralized clinical governance, particularly in organizations with rigid existing structures [20]. The model’s applicability depends heavily on contextual factors, such as the availability of skilled clinicians, adequate technical support, and whether corporate or nonprofit governance predominates in the healthcare system. Marshall et al. [20] report successful implementation of this framework in established hemodialysis programs, though comprehensive evaluation evidence comparing outcomes before and after implementation is limited in the literature.

3.1.2. General Models

In exploring the different approaches to HITH programs, six general models have been identified. These models represent different delivery modes and pathways for delivering at-home services to patients. The following sections detail these six HITH models and highlight their main elements.

Home Healthcare System Conceptual Model [21]

Lissovoy and Feustle [21] proposed a conceptual model of care including three components: Home, clinical service, and supply service. According to Lissovoy and Feustle [21], the home setting encompasses the patient, their living space, and the family members or other individuals who can help in care providing. The clinical service supplies external skilled workers, such as nurses, to provide care. And the supply service is in charge of providing equipment and consumable items. Based on this model, the combination of these three elements may differ in different conditions, and there is flexibility in terms of doing the jobs. For example, in the home and the clinical service components, the work done by the clinical service staff can replace the work done by people in the home setting, and the work done by the home caregivers can also substitute for the clinical service staff. In home-supply services, the need for labor provided by the home can be reduced when more medical equipment and devices are provided by the supply service. There is also the possibility of switching between the clinical service and supply service. The model was developed by Lissovoy and Feustle [21] based on a hospital-based total parenteral nutrition home care program (HTPN) in which clinicians select candidates during discharge planning. Patients need a partner for backup and support. Prior to discharge, a nurse trains the patient and their partner for two weeks. After discharge, a company provides the necessary equipment for the patient’s home, and a physician monitors the patient’s health through follow-up clinic visits [21].

The Home Healthcare System model proposed by Lissovoy and Feustle [21] offers flexibility in allocating responsibilities among three key components (home, clinical service, and supply service), allowing it to adapt to various patient and resource scenarios. This flexibility, however, may become a limitation when clear accountability is needed, as the model does not establish rigid governance structures. Implementation challenges include determining optimal allocation of responsibilities and establishing appropriate boundaries between clinical and home-based care activities [21]. The model’s applicability is influenced by contextual factors such as patient/caregiver capabilities, local healthcare workforce availability, and existing supply chain infrastructure for medical equipment. While Lissovoy and Feustle [21] developed this model based on a hospital-based total parenteral nutrition program, comprehensive evaluation evidence comparing different implementations of this flexible approach is not extensively documented in the literature.

Huntsman at Home Program [22]

A HITH model tailored for cancer patients was developed by the leaders of the University of Utah Health Huntsman Cancer Institute. This model features continuous monitoring and rapid intervention for patients facing unstable, acute medical issues [22]. Titchener et al. [22] reported on how this model works and what its components are. Hospital-level care in the patient’s own home is provided by nurse practitioners, home health registered nurses, and other staff. Management team, medical team, referral, and technology are the four main elements of this HITH model. The team model is centered on nurse practitioners taking the lead in providing care for the patient at home, collaborating closely with the registered nurses from the contracted home health agency to deliver that care. This model is led by nurse practitioners, with an overseeing medical director from Huntsman at Home who is board-certified in oncology and palliative medicine. Nurses also worked closely with the patient’s oncologist to ensure the treatment plan was coordinated effectively. Organizing the daily patient care routine that starts each morning with virtual rounds, evaluating new referrals, and addressing clinical questions are a lead nurse practitioner’s responsibility, while providing guidance on clinical matters, complex patient cases, and situations where patients are not responding to treatment are the medical director’s responsibilities. The referral model follows a clinical treatment plan. Based on the admission criteria, patients can be referred by their oncologist or the inpatient physician managing their hospital care. Referrals, whether electronic or by phone, are reviewed by the program’s admitting nurse practitioner, who decides to accept or decline them based on the treatment plan and the program’s current capacity [21].

The Huntsman at Home Program model demonstrates strength in its specialized focus on cancer patients with a nurse practitioner-led approach, which creates clear clinical leadership and specialized oncology expertise [22]. Its limitations include potential scalability challenges due to the requirement for specialized oncology training and close collaboration with oncologists. Implementation challenges include coordinating between nurse practitioners, registered nurses from contracted home health agencies, and hospital-based oncologists, particularly in maintaining consistent communication [22]. The model is most applicable in contexts with strong oncology departments, established home health agency partnerships, and sufficient nurse practitioners with specialized training. Evaluation evidence reported by Titchener et al. [22] suggests positive outcomes for cancer patients, though comparative studies with traditional oncology care models across different healthcare systems would strengthen the evidence base for this approach.

Advanced Care at Home (ACH) [23]

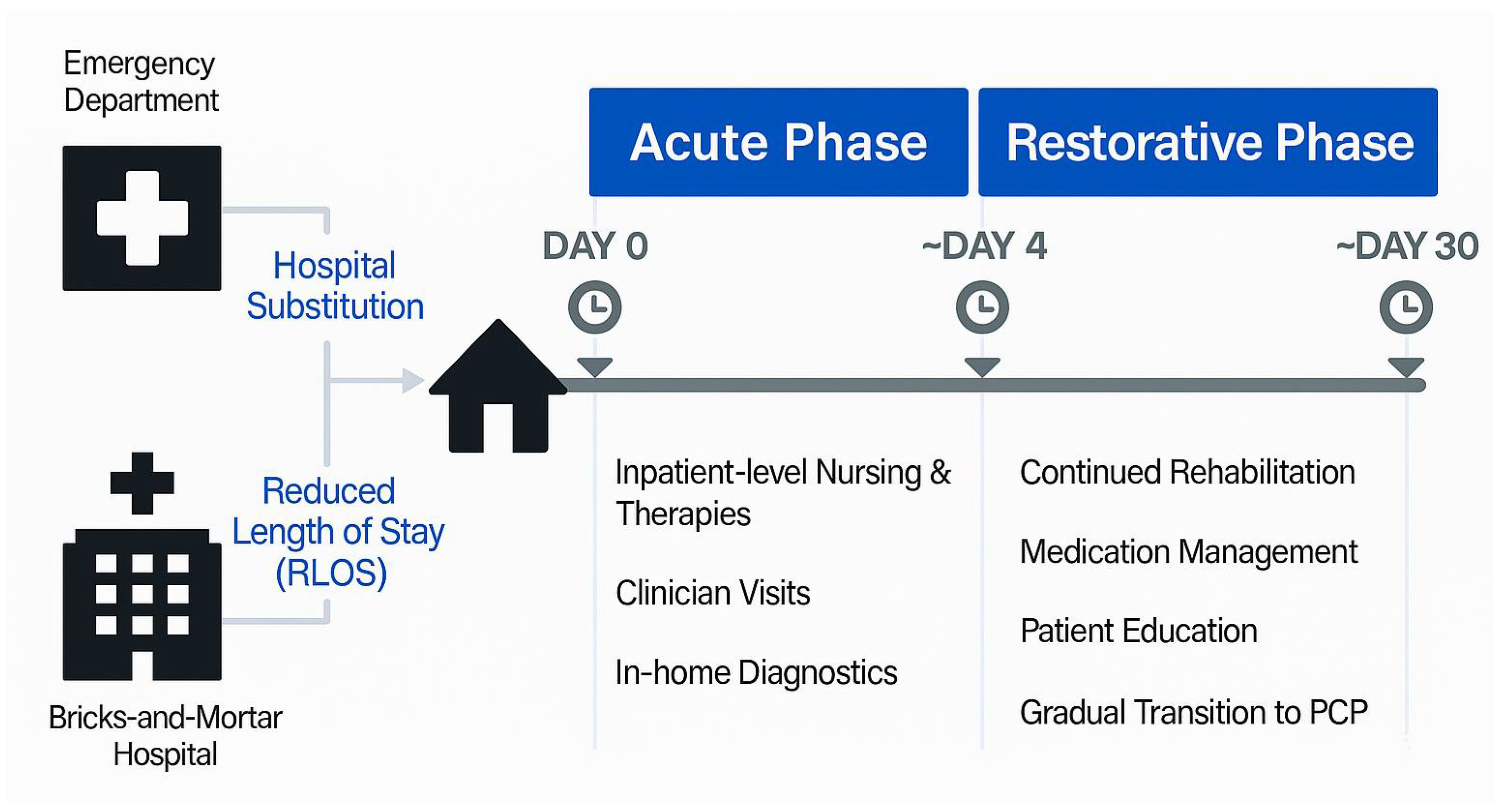

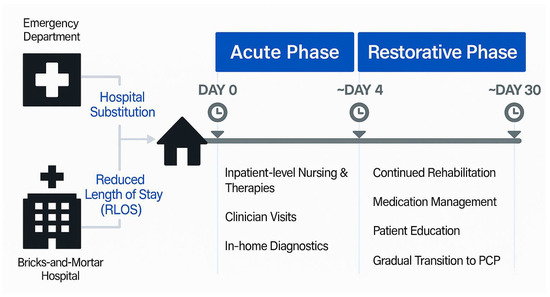

Paulson et al. [23] reported on a model developed by the Mayo Clinic called Advanced Care at Home (ACH). The model is a combination of virtual care and in-person care where an online doctor is available in a central command center, healthcare professionals make home visits to patients, and there is a service that delivers medical supplies to the patient’s home. There are three main linked-together components in this model that provide acute medical care management in the home setting. (1) Command center: Including doctors, registered nurses, and advanced practice providers (such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants) who work together with non-clinical service coordinators. The ACH model of hospital-at-home uses a centralized, single command center to coordinate and deliver inpatient-level care. The command center is also in charge of overseeing the care of all patients within ACH. (2) Technology in the home: Including custom technology kits for monitoring vital signs. (3) Care delivery services: Including a full suite of care services, such as APPs, community paramedics, registered nurses, aides, rehabilitative services, infusion therapy, phlebotomists, and basic radiography technicians dispatched to the patients’ homes to allow for the provision of scheduled and acutely activated urgent patient care needs. In this model, two referral pathways are defined through either the emergency department physician or the physical hospital. An admission meeting is organized by the ACH physician, ACH registered nurse, and the service coordinator to plan personalized patient care. The patient is then physically transported home by community paramedics. The model consists of two phases: acute and restorative. Once the acute phase reaches clinical stability, like discharge from a traditional hospital, patients can transition to the restorative phase of the ACH program. This phase involves virtual outpatient observation by the command center team. Figure 3 shows this model of care.

Figure 3.

The Advanced Care at Home Model of Care [23].

The Advanced Care at Home model introduces the strength of a centralized command center approach that efficiently coordinates virtual and in-person care, potentially serving multiple geographical regions from a single hub [23]. This approach, however, may be limited by substantial technology infrastructure requirements and potential disconnection between remote physicians and local care contexts. Implementation challenges include establishing reliable technology platforms, training staff in hybrid care delivery, and maintaining seamless coordination between virtual and physical care providers [23]. The model’s applicability depends significantly on technological infrastructure, availability of community paramedics and home-visiting staff, and regulatory environments permitting such virtual-physical hybrid approaches. Paulson et al. [23] described the model’s implementation, but comprehensive evaluation evidence comparing outcomes with traditional hospital care, particularly regarding cost-effectiveness and patient satisfaction across different conditions, would strengthen the case for broader adoption.

Hospital-Managed Advanced Care of Children in Their Homes [24]

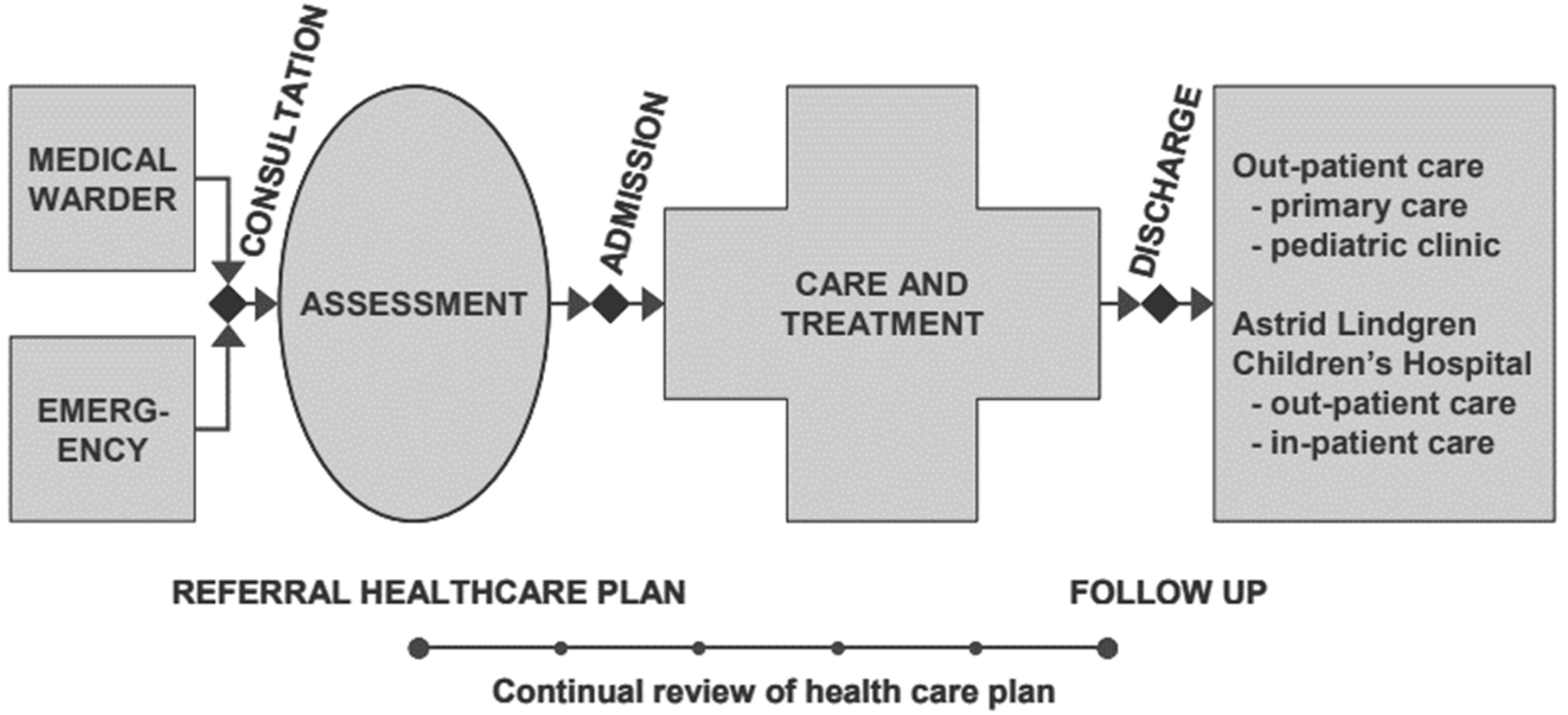

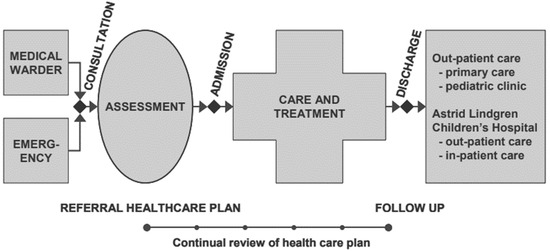

The Nordgren and Larsen [24] described an at-home program model for children based on mobile care teams with advanced information and communication technology, with 24 h accessibility to make the hospital’s resources accessible to the patient’s home. The model consists of two components. A centralized management unit where healthcare activities are coordinated and managed, and mobile medical care teams including a pediatrician, a medical social worker, a senior nurse, and an assistant nurse. The communication among patients, medical teams, and the management center is supported through modern IT devices. Patient monitoring is carried out in the home setting by both the program staff and the patients’ parents. Medical team staff provide parents with instructions on how to use the monitoring equipment. Patients can be referred from both hospital wards and casualty departments. Figure 4 shows the process from consultation to discharge in this model of care. After reaching a referral and early assessment, a care plan, including a treatment program and follow-up plan, is designed together with the responsible physician and nurse on the referring ward. As Figure 4 demonstrates, the care processes in this model describe a homecare model at a unit called Astrid Lindgren’s Children’s Hospital [24].

Figure 4.

Medical care process of the model [24].

The pediatric-focused model by Nordgren and Larsen [24] offers strengths in specialized pediatric care delivered through mobile medical teams with 24-h accessibility, making hospital resources available in home settings. Limitations include potential resource intensity and dependency on specialized pediatric medical teams that may not be widely available. Implementation challenges include training medical teams for pediatric home care, establishing effective coordination between centralized management and mobile teams, and ensuring appropriate technology adoption by both staff and parents [24]. Contextual factors affecting applicability include the availability of pediatric specialists, geographical distribution of patients, and parental willingness and capability to participate in monitoring. Nordgren and Larsen [24] described the model’s implementation at Astrid Lindgren’s Children’s Hospital, but comparative evaluation evidence establishing clear advantages over traditional pediatric inpatient care across multiple settings would strengthen support for wider implementation.

Integra at Home [25]

Fulton et al. [25] described an at-home medical care model for older adults with chronic complex needs. The model provides at-home acute care and 2 to 5-day high-need episodes as an alternative to emergency department and inpatient care. The interdisciplinary team includes geriatricians, nurse care managers, nurse practitioners, an external group called the CP group, the patient’s primary care practice team, pharmacy, social work, and resource specialists. According to this model, there is a continuum of home-based services in which the primary care team and the complex care management team are responsible for moving the patients along the continuum. According to the severity of the patients’ conditions, if they are frail enough, they may transfer to the home-based primary care program. Patients are typically referred based on a clinical treatment plan (opt-in enrolment approach) by primary care teams, identification by transition liaisons during inpatient care, or a referral from a complex care manager. Enrolment begins with a nurse care manager reaching out to the patient to explain the program and get their consent. After that, an at-home provider does the initial assessment, and together they create a care plan focused on treating the patient at home. The care team then makes regular home visits to check on the patient. The patient receives regular home visits from members of the care team. Medical equipment is brought in as needed through a health system partner, and medications are provided either by a local pharmacy or by community paramedics in urgent situations [25].

The Integra at Home model demonstrates strength in its comprehensive approach to older adults with chronic complex needs, offering a continuum of services that can flexibly respond to changing patient conditions [25]. Its interdisciplinary team structure incorporates multiple specialties but may be limited by resource intensity and coordination complexity. Implementation challenges include managing the interdisciplinary team effectively, ensuring smooth transitions along the care continuum, and maintaining communication between primary care teams and complex care management teams [25]. The model’s applicability is particularly tied to contexts with established geriatric services, strong primary care networks, and sufficient home care workforce availability. Fulton et al. [25] described the model, but comprehensive evaluation evidence comparing outcomes and cost-effectiveness with traditional geriatric care approaches would enhance understanding of its value proposition, particularly regarding emergency department visit reduction and hospital admission prevention.

Home Dialysis Model [26]

A model for home dialysis was developed by Fortnum et al. [26]. The model outlines a comprehensive pathway for managing chronic kidney disease (CKD), which includes stages from diagnosis through to various treatment modalities. When patients reach CKD stage 5, they are referred to a renal specialist center for assessment and preparation for their chosen modality of treatment. The model emphasizes two main types of dialysis treatments: hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD). Home dialysis, including both PD and home hemodialysis (HHD), is the primary treatment modality and can be facilitated in hospital, satellite, or community-based units. The transition between home dialysis modalities is planned within this framework. The steps for home dialysis involve assessment, training, installation, support, and, if necessary, withdrawal or transfer to another modality. CKD management is designed to be primarily GP-based, with support from renal specialists such as doctors or nurse practitioners, and primary education provided by skilled renal practitioners. This integrated approach aims to ensure comprehensive care and support for CKD patients throughout their treatment journey [26].

The home dialysis model by Fortnum et al. [26] demonstrates strength in providing a comprehensive pathway for chronic kidney disease management with clear progression stages. Its limitations include dependency on highly structured referral processes and potential challenges in training patients for self-management. Implementation challenges include ensuring effective assessment, training, and ongoing support for home dialysis, particularly in contexts with limited renal specialist resources [26]. The model’s applicability depends heavily on contextual factors, such as patient selection criteria, availability of renal specialists, and existing infrastructure for home-based dialysis. While Fortnum et al. [26] outlined this pathway-based approach, evaluation evidence specifically comparing outcomes between different governance approaches to home dialysis would provide valuable insights for healthcare executives considering implementation.

3.1.3. Virtual Models

Virtual Visit Track (VVT) [27]

Nair et al. [27] reported on the model of a virtual initiative proposed by Stanford Medicine in 2020, called the Virtual Visit Track (VVT) program. The model integrates remote care into pediatric and adult emergency departments (EDs). This virtual model involves pediatric and adult ED physicians, along with remote physicians, who provide low acuity care through virtual visits. Using specialized hardware, software, and a developed workflow, alongside comprehensive staff training, the program facilitates patient care remotely. Patients are triaged upon arrival at the ED, and if they meet the criteria for a virtual visit, they are connected to a remote physician. The remote physician conducts the consultation, reviews imaging and lab results if needed, and provides discharge instructions. This way, while reducing physical contact and potential overcrowding in the ED, this makes sure of effective patient care.

The Virtual Visit Track model presents strengths in its integration of remote care directly into emergency department workflows, potentially reducing overcrowding while maintaining quality of care [27]. However, limitations include dependency on specialized hardware/software infrastructure and potential challenges in patient selection for virtual visits. Implementation challenges include developing appropriate triage protocols, training staff in virtual assessment techniques, and ensuring seamless transitions between virtual and in-person care when needed [27]. The model’s applicability is influenced by contextual factors including emergency department volume, technological infrastructure, and regulatory environments permitting virtual emergency assessments. Nair et al. [27] described implementation at Stanford Medicine, but comprehensive evaluation evidence comparing patient outcomes, provider satisfaction, and system efficiency metrics between virtual and traditional emergency pathways would strengthen support for broader adoption of this model.

Long-Term Care Plus (LTC+) [28]

The last virtual model is an integrated care model called Long-Term Care Plus (LTC+) that could serve the needs of nursing home residents, caregivers, and providers, helping to reduce transfers of nursing home residents to acute care [28]. The main feature of this model is the use of a hub-and-spoke model. This hub-and-spoke model includes five components: (1) Virtual specialist consultations: The acute care hospital hubs provide virtual consultations with specialist physicians in fields like general internal medicine and palliative care. (2) Nurse navigator: Facilitate rapid access to services offered in the community, such as outreach nursing care, programs for behavioral support, and wound treatment. (3) Rapid access to laboratory and diagnostic imaging services: Coordinated with private sector laboratory providers to expand access to these services. (4) Educational webinars in collaboration with NH Medical Directors and Administrators. (5) The leadership team included members with expertise in primary care, long-term care, internal medicine, geriatric medicine, palliative care, quality improvement, data analytics, and virtual care [28].

The Long-Term Care Plus model demonstrates strength in its hub-and-spoke approach that efficiently extends specialist expertise to nursing home residents without requiring transfers. Its limitations include dependency on virtual consultation technology and potential challenges in care coordination across multiple organizations. Implementation challenges include establishing effective workflows between acute care hospitals and nursing homes, developing appropriate referral processes, and ensuring technology adoption by all stakeholders [28]. The model’s applicability is particularly dependent on contextual factors such as existing relationships between hospitals and nursing facilities, technology infrastructure in long-term care settings, and specialist availability for virtual consultations. Wong et al. [28] outlined this model, but comparative evaluation evidence specifically measuring impact on hospital transfer rates, patient outcomes, and cost-effectiveness across different implementation contexts would provide healthcare executives with stronger evidence for adoption decisions.

3.2. HITH Management Strategies

In response to the second research question, Table 3 indicates strategies that have been proposed for managing and governing different HITH models of care.

Table 3.

Strategies for managing and governing different HITH initiatives.

The strategies have been classified into five groups, including referral support, external support, care model support, technical support, and clinical team support (Table 3). The referral support group includes three strategies suggested by Mader et al. [29] and Inzitari et al. [19] for improving the patients’ referral assessments and processing. The external support category includes strategies for improving care delivery performance by leveraging third-party organizations such as regional communities. The care model support strategies are those suggested to improve the HITH program at the whole-model-of-care level and include five strategies. There are also six strategies categorized in the technological support group, which suggest using novel technology and equipment to improve care delivery performance. The clinical team support strategies include five strategies that support the clinical team. These strategies are indicated below in Table 3.

Summary of HITH Management Strategies by Category:

- Referral Support (R1–R3): Strategies for optimizing patient referral processes and pathways

- External Support (E1–E3): Approaches for leveraging third-party organizations and community resources

- Care Model Support (M1–M6): Frameworks for organizing comprehensive care delivery models

- Technical Support (T1–T6): Technology-based solutions for remote monitoring and care coordination

- Clinical Team Support (C1–C5): Strategies for optimizing healthcare team structure and coordination

According to Table 3, the referral support group includes three strategies with the aim of improving HITH programs by focusing on referral processes. R1 and R3 involve establishing multiple referral sites for admission and utilizing multiple referral pathways, respectively. This approach has been suggested in a HITH program targeting conditions like congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by Mader et al. [29], and in a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment HITH model by Inzitari et al. [19]. R2 suggests separating a referral if post-acute home services are required at the time of discharge [29].

The external support group, including three strategies, focuses on how leveraging external organizations and community resources would enhance HITH programs. As described by Marshall et al. [20], in a home hemodialysis program, E1 involves outsourcing parts of HITH programs, such as training the patients to another organization. E2 involves partnering with regional and rural health services to provide home-based bed substitutive care [30].

The care model support group includes six strategies extracted from literature on the HITH models and programs [20,31]. For example, M1 describes a Hub-and-Spoke Model in which a centralized regional location assesses all potential patients for home hemodialysis. According to the literature [20], this model can provide thorough evaluations and consistent follow-up care throughout the region. M3 emphasizes employing various modes of care delivery within home-based interdisciplinary primary care [31]. M6 involves a centralized command center to coordinate and deliver inpatient-level care in several regions [23]. These models highlight the significance of a customized model of care in improving the effectiveness of HITH programs.

The technological group includes six strategies to support the HITH program through leveraging new technologies and equipment. For instance, T3 involves using a new software platform to link the three components of the at-home program described by [23]. T4 focuses on utilizing custom technology kits to equip patients with the necessary tools for remote monitoring and care [23]. T6 suggests combining telehealth and in-person assessments by physicians, accommodating patients who need physical examinations or cannot participate in telehealth due to technology limitations or impairments [30]. These strategies demonstrate the key role of technology in improving patient care and operational efficiency in HITH programs.

For supporting clinical teams in HITH programs, Table 3 highlights five strategies. For example, C1 suggests employing a nurse-led program where a nurse care manager coordinates care among local social resources, emergency departments, hospitals, primary care medical resources, and the home care team, ensuring integration of services for cancer patients at home [22]. C2 indicates the importance of having two dedicated teams within a large geographical area to provide both acute services and subacute rehabilitative services to ensure patients receive appropriate care regardless of their location [30]. C4 emphasizes the integration of interdisciplinary care teams to manage the healthcare needs of older adults at home [19]. These strategies underscore the key role of well-coordinated and specialized clinical teams in the success of HITH programs.

3.3. Key Findings Summary

Our systematic review revealed three primary findings: First, explicit governance models for HITH programs are notably scarce in the literature, with only one comprehensive governance framework identified [20]. Second, operational approaches vary significantly across the six general models, ranging from flexible resource allocation systems [21] to highly specialized condition-specific programs [22,24,26]. Third, virtual models [27,28] demonstrate the growing integration of technology-mediated care, though implementation requires substantial infrastructure investment and careful patient selection protocols.

4. Discussion

Despite the existence of some systematic literature reviews from the effectiveness and safety perspectives of different HITH programs [1,11] or virtual services [16], there is a notable lack of studies examining HITH models from a management and governance perspective. For example, Leong et al. [11] systematically reviewed the safety and effectiveness of two major HITH program types, including early supported discharge and admission avoidance, based on the resource use and costs, patient and caregiver outcomes, etc., for offering recommendations for practice. Detollenaere et al. [1] systematically reviewed the effectiveness and safety of pediatric HITH programs as a substitute for hospital care. This study, from a management perspective, systematically reviewed and listed nine HITH models for managing HITH programs, as well as five groups of strategies for better managing these programs. Table 4 shows a comparison of Key Features Across HITH Management Models.

Table 4.

Key Features Across HITH Management Models.

This comparison table highlights the diversity in management approaches across HITH models, particularly in terms of accountability structures and staffing models. Models range from highly centralized command centers [23] to decentralized clinical governance [20] and flexible approaches [21]. Technology requirements vary significantly, from specialized dialysis equipment [20,26] to comprehensive virtual consultation platforms [27,28]. Target populations are often condition-specific [20,22,26], age-focused [24,25], or setting-specific [27,28]. The delivery models span a spectrum from primarily in-person care with technology support [21,24,26] to predominantly virtual approaches [27,28], with several hybrid models [22,23] combining elements of both. These variations suggest that healthcare organizations should carefully consider their specific context, target population, and available resources when selecting or adapting a HITH management model.

4.1. Implications for the First Research Question: Models and Frameworks for HITH Initiatives

The identification of nine management models across three distinct categories (Table 2) reveals important patterns for HITH implementation. The single governance model identified [20] emphasizes the critical need for explicit accountability structures, while the six general models [21,22,23,24,25,26] demonstrate diverse operational approaches, including both flexible frameworks adaptable across contexts [21,23,25] and specialized approaches for specific clinical populations [22,24,26]. The two virtual models [27,28] highlight the growing importance of technology-mediated care delivery. As shown in Table 4, these models vary significantly in their accountability structures, technology requirements, and staffing models, suggesting that healthcare executives must carefully match model characteristics to their organizational context and patient populations. However, the identification of only one explicit governance model in our review reveals a significant limitation in the current literature and suggests that most HITH implementations may lack formal governance structures, representing an important area for future research and development.

The six general HITH models and two virtual HITH models identified in this study highlight a diverse array of approaches for delivering HITH programs, ranging from early supported discharge to admission avoidance, various referral sources, including external, internal, and self-referral sources, and utilizing virtual, in-person, or hybrid delivery modes. The insights from these models can provide a blueprint for healthcare providers to tailor HITH programs to their specific contexts, whether they are dealing with a vast geographical region or a specific type of care. It can be said that the main elements common to these models are referral pathway, clinical team, operational team, external partners, and technology and equipment. The combination of these main elements may vary under different conditions.

As described by Lissovoy and Feustle [21], there is the possibility of switching between clinical service and supply service. For example, in a home hemodialysis program described by [20], all training and subsequent follow-up are outsourced to an external organization. Another example of this combination is seen in the operational structure: in one model, the responsibility for overseeing the HITH program lies with a nurse care manager who coordinates care [22], while another model is managed by a command center that includes doctors, registered nurses, and advanced practice providers [23]. Depending on the program’s specifications, the model may consist of only two main elements, such as a central management unit where healthcare activities are coordinated and mobile medical care teams supported by modern IT devices [24]. Or, like the hub-and-spoke model, it may be composed of five components [28].

For health providers looking to implement a HITH program, the results of the first section can help identify the best model among early-discharge, hospital admission avoidance, in-person care delivery, virtual, or hybrid models. For example, according to Mader et al. [29], an early-discharge model is simpler to develop and can handle more patients compared to a full hospital substitution model. However, it may not save as much money or reduce iatrogenic events as effectively as a hospital admission avoidance model.

4.2. Implications for the Second Research Question: Management Strategies for HITH Initiatives

In response to the second research question, five groups of strategies were identified. A total of 23 strategies were categorized into five groups, including referral support, external support, care model support, technical support, and clinical team support (Table 3). Each of these groups is a main element of an HITH model, according to what we found in response to the first research questions. The 23 strategies identified in Table 3 directly support the implementation of the models analyzed in Section 3.1. The five strategy categories—referral support (R1–R3), external support (E1–E3), care model support (M1–M6), technical support (T1–T6), and clinical team support (C1–C5)—correspond to the key components identified across our analyzed models. For instance, the referral support strategies directly address the varied referral sources documented in Table 4, while the technical support strategies align with the diverse technology requirements identified across different model types.

The systematic analysis of the nine models and 23 strategies reveals significant variation in implementation approaches that healthcare executives must navigate when selecting HITH management options. Our comparative analysis in Table 4 demonstrates that models differ substantially across accountability structures, technology requirements, staffing models, and target populations. For example, referral strategies must align with program specifications and delivery modes—virtual care models may require single streamlined pathways [28], while comprehensive programs benefit from multiple referral sources, including acute hospitals, emergency departments, and primary care [19]. Similarly, technology requirements vary dramatically from simple communication tools for in-person models [24] to sophisticated remote monitoring and virtual ward systems for technology-dependent approaches [19,34]. External partnerships offer benefits such as outsourcing training and follow-up [20] but also introduce complexities, including electronic health record incompatibilities and coordination challenges [23].

Building on these findings, we propose a practical assessment framework that synthesizes our analysis into six critical dimensions for healthcare executives: (1) Scalability—capacity to expand without proportional resource increases, ranging from high [23,28] to low [24,26]; (2) Resource Requirements—financial, human, and technological investments needed, from substantial [20,23,24] to modest [21,27]; (3) Adaptability—flexibility to accommodate different conditions, from highly adaptable [21,23] to condition-specific [20,22,24,26]; (4) Integration Capacity—ease of incorporating into existing systems, from seamless [23,27,28] to challenging [20,22,24,26]; (5) Governance Clarity—explicitness of accountability structures, from well-defined [20,23] to flexible [21,24,27,28]; and (6) Evidence Base—availability of evaluation data, from strong [23] to emerging [21,24,26]. This framework enables systematic evaluation of HITH models against organizational priorities and implementation contexts, directly reflecting the diversity documented in our systematic review, where models range from highly scalable virtual approaches to specialized condition-specific programs with substantial resource requirements. It directly reflects the diversity documented in our systematic review, where models like the Advanced Care at Home [23] and Long-Term Care Plus [28] demonstrate high scalability, while specialized approaches like the Home Hemodialysis Hub [20] and Huntsman at Home [22] show condition-specific focus with substantial resource requirements. The framework enables executives to systematically match our identified models and strategies to their specific implementation context.

4.3. Integration of Models and Strategies

The relationship between the identified models (Table 2) and strategies (Table 3) reveals systematic patterns that guide implementation decisions. Models with centralized accountability structures [20,23] benefit most from technical support strategies (T1–T6) and coordinated clinical team approaches (C1–C5). Conversely, flexible models [21] show greater compatibility with external support strategies (E1–E3) that leverage community resources. The virtual models [27,28] demonstrate heavy reliance on technical support strategies, while disease-specific models [20,22,26] emphasize clinical team support strategies. This systematic relationship between model characteristics and optimal strategy selection provides healthcare executives with a structured approach to HITH program design and implementation.

4.4. Implications for Researchers

This study aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the existing HITH models and strategies for managing these programs through addressing their research questions. In response to the first research question, “What management models and frameworks have been proposed for HITH initiatives?”, we observed that the development of comprehensive management models for HITH programs has received limited attention, with only one explicit governance model identified. The only model identified was proposed by Marshall et al. [20] specifically for a type of HITH program focused on hemodialysis. Future research studies should focus on developing a general governance model that clearly determines accountability across all processes and elements within an HITH program.

4.5. Recommendations for Healthcare Executives

Healthcare executives should select HITH models based on their organizational context and priorities. For resource-constrained settings, consider flexible models with modest technology requirements [21,27]; for specialized care needs (e.g., oncology, dialysis), implement disease-specific models with clear clinical governance [20,22,26]; for organizations serving diverse populations across large geographic areas, centralized command centre approaches offer scalability advantages [23,28]; and for organizations prioritizing integration with existing systems, hub-and-spoke models facilitate gradual implementation [20,28]. Organizations with strong home care infrastructure should leverage nurse-led models [22], while those with robust virtual care capabilities may benefit from telehealth-intensive approaches [27,28]. Regardless of model selection, we recommend starting with a clearly defined patient population and gradually expanding scope as governance processes mature.

4.6. Implementation Barriers and Challenges

Implementing HITH governance models presents several potential barriers that healthcare organizations must address. Our review identified challenges across different implementation contexts that may impede successful adoption. The models with significant virtual care components [23,27,28] often face technical infrastructure limitations and interoperability issues between hospital and home-based systems. Several studies in our review [20,22] highlight potential professional resistance from clinicians concerned about changes to accountability structures and clinical oversight processes. Patient selection challenges were also evident in multiple models [19,29], where inappropriate referrals could lead to safety issues and unplanned returns to hospital settings. Models requiring specialized clinical expertise [20,22,26] faced additional implementation barriers related to workforce availability and training requirements. Organizations considering HITH implementation must develop mitigation strategies for these barriers based on their specific healthcare context and the governance model selected.

4.7. Economic Considerations of Governance Models

The economic implications of different HITH governance approaches require careful consideration. Centralized command center models [23] demand significant upfront investment but may offer economies of scale when serving large populations. Nurse-led models [22] typically have lower technology costs but may face workforce availability challenges in competitive labor markets. Hub-and-spoke approaches [20,28] allow for gradual scaling of resources but require robust coordination mechanisms. Healthcare executives must evaluate these economic trade-offs in the context of their organization’s financial constraints, existing infrastructure, and strategic priorities. While comprehensive cost-effectiveness analyses of different governance models remain limited in the literature, our findings suggest that models with flexible resource allocation [21] may be more adaptable to varying economic conditions than highly specialized approaches [20,26].

4.8. Comparison with Similar Healthcare Service Models

The governance challenges in HITH programs share similarities with other healthcare delivery models identified in our review. The comprehensive geriatric assessment approaches described by Inzitari et al. [19] demonstrate governance structures that coordinate care across multiple settings, offering insights for broader HITH implementation. Similarly, the home-based interdisciplinary primary care models discussed by Franzosa et al. [31] provide frameworks for engaging both clinical teams and community resources, which could inform HITH governance development. The transitional care interventions outlined by Toles et al. [32] offer valuable perspectives on governance structures that bridge hospital and home environments. Several strategies identified in our review, particularly those related to care model support [19,31,32] and clinical team support [19,22], could be adapted from these parallel healthcare domains to strengthen HITH governance frameworks. Future research could benefit from a more explicit comparison of governance approaches across these related healthcare delivery models.

4.9. Limitations

The findings of this study are based solely on a systematic literature review, without empirical data collection or expert views. Therefore, the validity threats and limitations present in our reviewed papers may also apply to this research. Additionally, systematic literature review studies are always limited by inclusion and exclusion criteria and the scope of available databases, which is a common limitation of this type of research.

5. Conclusions

As Hospital in the Home (HITH) programs emerge as a crucial component of smart city architecture, leveraging technology to extend care beyond traditional hospital walls, this systematic review sheds light on the current state of HITH governance and management models, addressing a critical gap in the literature. This study makes three key contributions: (1) it synthesizes and categorizes existing HITH management models into a coherent taxonomy, (2) it extracts actionable strategies from successful implementations that can guide practice, and (3) it identifies critical gaps in governance research that future studies should address. The findings of this systematic review have substantial practical significance for healthcare leaders implementing HITH programs. The identification of nine management models, categorized into three distinct groups (governance, general, and virtual models), provides a comprehensive framework for healthcare executives and HITH program managers to reference when implementing or improving their own programs. Furthermore, the 23 identified strategies, spanning five key areas of support, offer practical guidance for enhancing HITH management and provide healthcare executives with an evidence-based toolkit for designing and optimizing HITH initiatives tailored to their specific contexts.

These findings are particularly timely given the growing importance of virtual care in addressing the needs of an aging population with chronic diseases, and the potential of HITH programs to alleviate pressure on hospital bed occupancy. As the healthcare landscape continues to evolve, the models and strategies presented in this study serve as valuable tools for healthcare providers seeking to optimize their HITH initiatives, ultimately contributing to more efficient and patient-centered care delivery. By selecting appropriate governance structures and implementing targeted strategies across referral processes, external partnerships, care models, technology integration, and clinical team management, healthcare organizations can reduce implementation barriers, optimize resource utilization, and maintain clinical quality and accountability. These practical frameworks enable health systems to expand care capacity beyond physical walls, directly addressing the critical challenges of growing demand, limited bed capacity, and rising healthcare costs identified in this review.

Funding

This research was funded by Western Health (number VUR20964).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Detollenaere, J.; Van Ingelghem, I.; Van den Heede, K.; Vlayen, J. Systematic literature review on the effectiveness and safety of paediatric hospital-at-home care as a substitute for hospital care. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 2735–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, B.; DeCherrie, L.V.; Montalto, M.; Levine, D.M. A research agenda for hospital at home. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, B.; Montalto, M. Home hospital—Toward a tighter definition. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentur, N. Hospital at home: What is its place in the health system? Health Policy 2001, 55, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jester, R.; Titchener, K.; Doyle-Blunden, J.; Caldwell, C. The development of an evaluation framework for a Hospital at Home service: Lessons from the literature. J. Integr. Care 2015, 23, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitammagari, K.; Murphy, S.; Kowalkowski, M.; Chou, S.-H.; Sullivan, M.; Taylor, S.; Kearns, J.; Batchelor, T.; Rivet, C.; Hole, C.; et al. Insights from rapid deployment of a “virtual hospital” as standard care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, J.A.; Pawelek, J.B.; Leff, B.; Topol, E.J. The hospital at home in the USA: Current status and future prospects. Npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Hospital Beds (per 1000 People). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Qaddoura, A.; Yazdan-Ashoori, P.; Kabali, C.; Thabane, L.; Haynes, R.B.; Connolly, S.J.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Abete, P. Efficacy of hospital at home in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varney, J.; Weiland, T.J.; Jelinek, G. Efficacy of hospital in the home services providing care for patients admitted from emergency departments: An integrative review. JBI Evid. Implement. 2014, 12, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, M.Q.; Lim, C.W.; Lai, Y.F. Comparison of Hospital-at-Home models: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Burt, J.; Roland, M. Measuring patient experience: Concepts and methods. Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2014, 7, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossinot, H.; Marquestaut, O.; de Stampa, M. The experience of patients and family caregivers during hospital-at-home in France. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfelt, W.T.; Sulo, S.; Robinson, A.; Chess, D.; Catanzano, K. Scalable hospital at home with virtual physician visits: Pilot study. Am J Manag. Care 2015, 21, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lasseter, J.A. Complex-Technology Home Care: Ethics, Caring, and Quality of Life. University of Kansas. 2004. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/305174246?fromopenview=true&pq-origsite=gscholar&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Ekeleme, N.; Yusuf, A.; Kastner, M.; Waite, K.; Montesanti, S.; Atherton, H.; Salvalaggio, G.; Langford, L.; Sediqzadah, S.; Ziegler, C.; et al. Guidelines and recommendations about virtual mental health services from high-income countries: A rapid review. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e079244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Vale, J.; Franco, A.I.; Oliveira, C.V.; Araújo, I.; Sousa, D. Hospital at home: An overview of literature. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2020, 32, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzitari, M.; Arnal, C.; Ribera, A.; Hendry, A.; Cesari, M.; Roca, S.; Pérez, L.M. Comprehensive Geriatric hospital at home: Adaptation to referral and case-mix changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 3–9.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M.R.; Young, B.A.; Fox, S.J.; Cleland, C.J.; Walker, R.J.; Masakane, I.; Herold, A.M. The home hemodialysis hub: Physical infrastructure and integrated governance structure. Hemodial. Int. 2015, 19, S8–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissovoy, G.; Feustle, J.A. Advanced home health care. Health Policy 1991, 17, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchener, K.; Coombs, L.A.; Dumas, K.; Beck, A.C.; Ward, J.H.; Mooney, K. Huntsman at Home, an oncology hospital at home program. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, M.R.; Shulman, E.P.; Dunn, A.N.; Fazio, J.R.; Habermann, E.B.; Matcha, G.V.; McCoy, R.G.; Pagan, R.J.; Maniaci, M.J. Implementation of a virtual and in-person hybrid hospital-at-home model in two geographically separate regions utilizing a single command center: A descriptive cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergius, H.; Eng, A.; Fagerberg, M.; Gut, T.; Jacobsson, U.; Lundell, B.; Palmquist, Y.; Rylander, E. Hospital-managed advanced care of children in their homes. J. Telemed. Telecare 2001, 7 (Suppl. 1), 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, A.T.; Vognar, L.; Stuck, A.R.; McBride, C.; Scott, R.; Crowley, C. Integra at Home: A flexible continuum of in-home medical care for older adults with complex needs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortnum, D.; Mathew, T.; Johnson, K. A Model for Home Dialysis Australia; Kidney Health Australia: Southbank, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, A.; Rosengaus, L.; Findikaki, H.; Barahimi, H.; Moyer, M.; Williams, E. Transforming the ED Fast Track to a Virtual Visit Track to Reduce Emergency Department Length of Stay Stanford Medicine. 2023. Available online: https://www.himss.org/sites/hde/files/media/file/2023/08/11/stanford-medicine-himss-davies-2023-telehealth-in-the-ed-final.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Wong, B.M.; Rotteau, L.; Feldman, S.; Lamb, M.; Liang, K.; Moser, A.; Mukerji, G.; Pariser, P.; Pus, L.; Razak, F.; et al. A novel collaborative care program to augment nursing home care during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 304–307.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, S.L.; Medcraft, M.C.; Joseph, C.; Jenkins, K.L.; Benton, N.; Chapman, K.; Donius, M.A.; Baird, C.; Harper, R.; Ansari, Y.; et al. Program at home: A Veterans Affairs Healthcare Program to deliver hospital care in the home. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.M.; Island, L.; Horsburgh, A.; Maier, A.B. Home first! identification of hospitalized patients for home-based models of care. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 413–417.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzosa, E.; Gorbenko, K.; Brody, A.A.; Leff, B.; Ritchie, C.S.; Kinosian, B.; Ornstein, K.A.; Federman, A.D. At home, with care: Lessons from New York City home-based primary care practices managing COVID-19. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toles, M.; Leeman, J.; McKay, M.H.; Covington, J.; Hanson, L.C. Adapting the Connect-Home transitional care intervention for the unique needs of people with dementia and their caregivers: A feasibility study. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 48, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benz, C.; Middleton, A.; Elliott, A.; Harvey, A. Physiotherapy via telehealth for acute respiratory exacerbations in paediatric cystic fibrosis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 29, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, D.; Conley, J. The next frontier of remote patient monitoring: Hospital at home. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e42335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).