CALM: Continual Associative Learning Model via Sparse Distributed Memory

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Establish evaluation system to configure optimal parameters for SDM devices.

- 2.

- Validate the characteristic behavior of SDM (S1) by synthetic tests from the benchmark.

- 3.

- Define and validate the preliminary architecture containing the SDM module (S1) and dual-transformer module (S2),

2. Related Work

2.1. SDM Foundations and Neuroscientific Principles

2.2. Neuromorphic Implementations

2.3. Multimodal and Memory-Augmented Learning

2.4. CALM Positioning Within Continual Learning LLMs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. SDM Evaluation Methodology

3.2. Encoding Techniques

3.3. SDM Benchmark Design

3.4. System 1 Methodology

- 1.

- Establish inherent S1 mechanisms;

- 2.

- Integrate intuitive S1 mechanisms;

- 3.

- Implement controller to detect emergent S1 mechanisms;

- 4.

- Integrate S2 dual transformers to S1 (SDM and controller).

3.5. CALM Integration

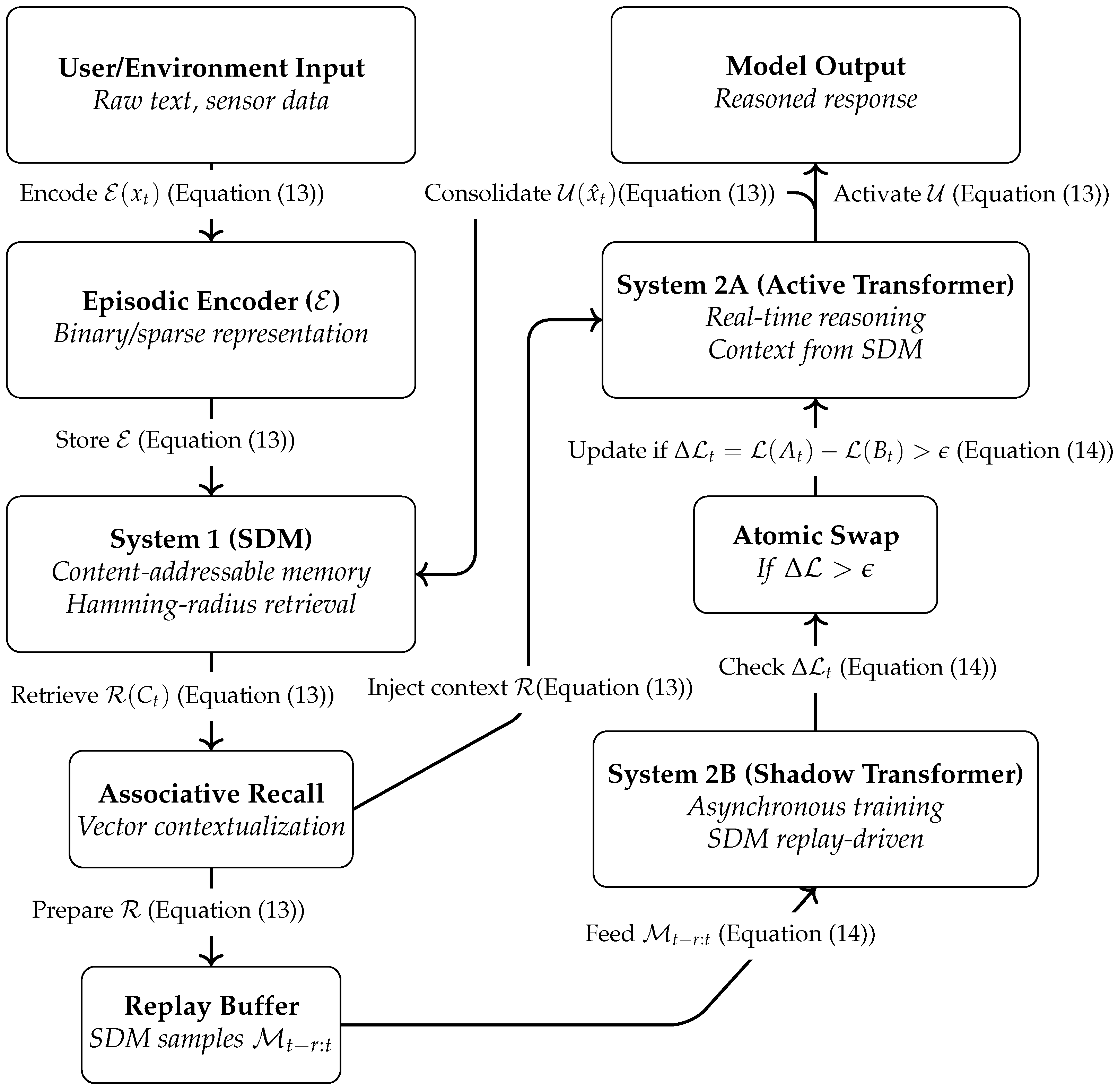

3.6. CALM Architecture

- Continual Adaptation: SDM is allowing rapid incorporation of new data without retraining.

- Memory Grounding: The system maintains an episodic trace of events, enabling structured recall and S1 operations.

- Biological Plausibility: The modular memory structure aligns with the distributed intelligence of the cortical columns and sensorimotor integration.

- 1.

- Encoding and Acquisition: New input is encoded as high-dimensional binary vectors and stored in SDM.

- 2.

- Retrieval and Reasoning: SDM provides associative recall to the Active Transformer, which generates responses and updates memory into the SDM.

- 3.

- Consolidation: The Shadow Transformer fine-tunes asynchronously on SDM replay data, ensuring gradual learning without disrupting live performance.

| Algorithm 1 S1–S2 Online Learning Loop with SDM Internals and Atomic Swap. | |

| |

| ▹ Episodic encoding: Equation (13) |

| ▹Associative recall: Equation (13) ; uses radius r from empirical SDM threshold |

| ▹ Lightweight S2 reasoning (transformer) |

| ▹ Consolidation: Equation (13) |

| |

| ▹ Construct replay batch for shadow transformer |

| ▹ Asynchronous shadow S2 update using replay batch |

| ▹ Equation (14): measurable improvement |

| |

| ▹ Atomic swap: update active S2 only if improvement exceeds threshold |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| ▹ Radius-based weight; see Section 3.1, Equations (5) and (10) |

| |

| |

| |

| ▹ Weighted aggregate retrieval; cf. Equations (3) and (4) |

| |

| |

| |

| ▹ Weighted accumulation; preserves prior memory and handles interference; see Equations (2) and (11) |

| |

| |

| |

| ▹ Replay batch construction; cf. Table 1 and discussion in Section 3.1 |

| |

| |

4. Preliminary Results

5. Discussion and Future Work

5.1. Convergence and Generalization

5.2. High-Load Degradation Considerations

- Capacity saturation curves: The empirical capacity factor (Equation (21)) suggests that match ratios remain high up to a threshold memory size, beyond which efficiency decreases due to overlapping activations.

- Dynamic radius adaptation: To maintain high recall under increased load, the optimal radius should scale with memory utilization, balancing miss and interference probabilities as described in Equation (20) [1,68]. Parameter tuning in high-dimensional vector spaces for associative memory retrieval can apply radius/threshold adaptation. Controlling these conditions is expected to accommodate high memory load at least partially if access radius and reinforcement strategies are adapted.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CALM | Continual Associative Learning Model |

| EGRU | Event-based Gated Recurrent Units |

| EWC | Elastic Weight Consolidation |

| FISTA | Fast Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm |

| GEM | Gradient Episodic Memory |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ISTA | Iterative Shrinkage–Thresholding Algorithm |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LSH | Locality-Sensitive Hashing |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| S1 | System 1 framework |

| S2 | System 2 framework |

| SDM | Sparse Distributed Memory |

| SI | Synaptic Intelligence |

| SoC | System-on-a-Chip |

| T/M | Time per Memory location |

| VC | Virtual Cities |

| WYSIATI | What You See Is All There Is |

References

- Kanerva, P. Sparse Distributed Memory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kanerva, P. Self-Propagating Search: A Unified Theory of Memory (Address Decoding, Cerebellum). Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Karunaratne, G.; Le Gallo, M.; Cherubini, G.; Benini, L.; Rahimi, A.; Sebastian, A. In-memory hyperdimensional computing. Nat. Electron. 2020, 3, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, J.D. Capacity for patterns and sequences in Kanerva’s SDM as compared to other associative memory models. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 1 November 1987; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, M.J.; Kanerva, P.; Bhadkamkar, N. Sparse Distributed Memory: Principles and Operation; Number RIACS-TR-89-53; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. A theory of cerebellar cortex. J. Physiol. 1969, 202, 437–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albus, J.S. Mechanisms of planning and problem solving in the brain. Math. Biosci. 1979, 45, 247–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawato, M.; Ohmae, S.; Hoang, H.; Sanger, T. 50 Years Since the Marr, Ito, and Albus Models of the Cerebellum. Neuroscience 2021, 462, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, P. Sparse Distributed Memory and Related Models; NASA Contractor Report NASA-CR-190553; NASA Ames Research Center: Moffett Field, CA, USA, 1992.

- Bricken, T.; Davies, X.; Singh, D.; Krotov, D.; Kreiman, G. Sparse Distributed Memory is a Continual Learner. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinkus, G.J. A cortical sparse distributed coding model linking mini- and macrocolumn-scale functionality. Front. Neuroanat. 2010, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutishauser, U.; Mamelak, A.N.; Schuman, E.M. Single-Trial Learning of Novel Stimuli by Individual Neurons of the Human Hippocampus–Amygdala Complex. Neuron 2006, 49, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixted, J.T.; Squire, L.R.; Jang, Y.; Papesh, M.H.; Goldinger, S.D.; Kuhn, J.R.; Smith, K.A.; Treiman, D.M.; Steinmetz, P.N. Sparse and distributed coding of episodic memory in neurons of the human hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9621–9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaider, J.; Franklin, S.; Strain, S.; George, E.O. Integer sparse distributed memory: Analysis and results. Neural Netw. 2013, 46, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furber, S.B.; John Bainbridge, W.; Mike Cumpstey, J.; Temple, S. Sparse distributed memory using N-Codes. Neural Netw. 2004, 17, 1437–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, L.; Rhodes, O. Parallelization of Neural Processing on Neuromorphic Hardware. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 867027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, H.A.; Huang, J.; Kelber, F.; Nazeer, K.K.; Langer, T.; Liu, C.; Lohrmann, M.; Rostami, A.; Schöne, M.; Vogginger, B.; et al. SpiNNaker2: A Large-Scale Neuromorphic System for Event-Based and Asynchronous Machine Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bellec, G.; Vogginger, B.; Kappel, D.; Partzsch, J.; Neumärker, F.; Höppner, S.; Maass, W.; Furber, S.B.; Legenstein, R.; et al. Memory-Efficient Deep Learning on a SpiNNaker 2 Prototype. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazeer, K.K.; Schöne, M.; Mukherji, R.; Mayr, C.; Kappel, D.; Subramoney, A. Language Modeling on a SpiNNaker 2 Neuromorphic Chip. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.09084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boahen, K. Dendrocentric learning for synthetic intelligence. Nature 2022, 612, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, M.; Ordonez, V.; Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. XNOR-Net: ImageNet Classification Using Binary Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.05279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vdovychenko, R.; Tulchinsky, V. Sparse Distributed Memory for Sparse Distributed Data. In Intelligent Systems and Applications; Arai, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vdovychenko, R.; Tulchinsky, V. Sparse Distributed Memory for Binary Sparse Distributed Representations. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Machine Learning Technologies, ICMLT ’22, Rome Italy, 11–13 March 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Paz, D.; Ranzato, M.A. Gradient Episodic Memory for Continual Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Pascanu, R.; Rabinowitz, N.; Veness, J.; Desjardins, G.; Rusu, A.A.; Milan, K.; Quan, J.; Ramalho, T.; Grabska-Barwinska, A.; et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3521–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnick, D.; Ahuja, A.; Schwarz, J.; Lillicrap, T.P.; Wayne, G. Experience Replay for Continual Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1811.11682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenke, F.; Poole, B.; Ganguli, S. Continual Learning Through Synaptic Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August July 2017; pp. 3987–3995. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.; Field, D. 3.14—Sparse Coding in the Neocortex. Evol. Nerv. Syst. 2007, 3, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyeler, M.; Rounds, E.L.; Carlson, K.D.; Dutt, N.; Krichmar, J.L. Neural correlates of sparse coding and dimensionality reduction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jääskeläinen, I.P.; Glerean, E.; Klucharev, V.; Shestakova, A.; Ahveninen, J. Do sparse brain activity patterns underlie human cognition? NeuroImage 2022, 263, 119633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drix, D.; Hafner, V.V.; Schmuker, M. Sparse coding with a somato-dendritic rule. Neural Netw. 2020, 131, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olshausen, B.A.; Field, D.J. Sparse coding of sensory inputs. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004, 14, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.D.H. Sparse Code Formation with Linear Inhibition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.04115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzeri, S.; Moroni, M.; Safaai, H.; Harvey, C.D. The structures and functions of correlations in neural population codes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 23, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisanguanthum, K.S.; Lisberger, S.G. A Neurally Efficient Implementation of Sensory Population Decoding. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 4868–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, K.; Dadush, D.; Gandikota, V.; Grigorescu, E. Lattice-based Locality Sensitive Hashing is Optimal. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.08558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, K.; LeCun, Y. Learning fast approximations of sparse coding. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML’10, Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; Omnipress: Madison, WI, USA, 2010; pp. 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Salakhutdinov, R.; Hinton, G. Semantic hashing. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2009, 50, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, J.; Ye, D.; Hua, G. LQ-Nets: Learned Quantization for Highly Accurate and Compact Deep Neural Networks. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11212, pp. 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Parekh, Z.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.; Sung, Y.H.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T. Scaling Up Visual and Vision-Language Representation Learning with Noisy Text Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 4904–4916. [Google Scholar]

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; et al. Flamingo: A Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 23716–23736. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. BLIP: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training for Unified Vision-Language Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 12888–12900. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 19730–19742. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Changpinyo, S.; Piergiovanni, A.J.; Padlewski, P.; Salz, D.; Goodman, S.; Grycner, A.; Mustafa, B.; Beyer, L.; et al. PaLI: A Jointly-Scaled Multilingual Language-Image Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2209.06794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Zolna, K.; Parisotto, E.; Colmenarejo, S.G.; Novikov, A.; Barth-Maron, G.; Gimenez, M.; Sulsky, Y.; Kay, J.; Springenberg, J.T.; et al. A Generalist Agent. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.06175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Lin, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Guo, W. Lightweight bilateral network of Mura detection on micro-OLED displays. Measurement 2025, 255, 117937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, B. Multi-task learning for hand heat trace time estimation and identity recognition. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, B.; Xue, H. Deep soft threshold feature separation network for infrared handprint identity recognition and time estimation. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 138, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Z. ELDER: Enhancing Lifelong Model Editing with Mixture-of-LoRA. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 24440–24448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Thérien, B.; Ibrahim, A.; Richter, M.L.; Anthony, Q.; Belilovsky, E.; Rish, I.; Lesort, T. Continual Pre-Training of Large Language Models: How to (re)warm your model? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.04014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.N.; Quarantiello, L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Q.; Mukherjee, S.; Hurtado, J.; Lomonaco, V. Parameter-Efficient Continual Fine-Tuning: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.13822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Mozafari, B. Transformer with Memory Replay. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 7567–7575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resta, M.; Bacciu, D. Self-generated Replay Memories for Continual Neural Machine Translation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagirova, A.; Burtsev, M. Extending Transformer Decoder with Working Memory for Sequence to Sequence Tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Computation, Machine Learning, and Cognitive Research V; Kryzhanovsky, B., Dunin-Barkowski, W., Redko, V., Tiumentsev, Y., Klimov, V.V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xu, Q.; Pan, G.; Chen, B. Improving the Sparse Structure Learning of Spiking Neural Networks from the View of Compression Efficiency. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, P.; Huang, X.; Laborieux, A.; Nikpour, B.; Shi, T.; Eshaghi, A. Memory-Augmented Transformers: A Systematic Review from Neuroscience Principles to Enhanced Model Architectures. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Hu, D. Lifelong learning with Shared and Private Latent Representations learned through synaptic intelligence. Neural Netw. 2023, 163, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W. Towards General Purpose Robots at Scale: Lifelong Learning and Learning to Use Memory. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2501.10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksander, I.; Stonham, T.J. Guide to pattern recognition using random-access memories. IEE J. Comput. Digit. Tech. 1979, 2, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Yin, W. Theoretical Linear Convergence of Unfolded ISTA and its Practical Weights and Thresholds. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilov, U.S.; Mansour, H. Learning optimal nonlinearities for iterative thresholding algorithms. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2016, 23, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Optimal Lower Bounds for Locality-Sensitive Hashing (Except When q is Tiny). ACM Trans. Comput. Theory 2014, 6, 5:1–5:13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, L.; Sun, Y. Differentiable Product Quantization for End-to-End Embedding Compression. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 12–18 July 2020; Daumé, H., III, Singh, A., Eds.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research (PMLR): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 119, pp. 1617–1626. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, T.; He, K.; Ke, Q.; Sun, J. Optimized Product Quantization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 36, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Frederic, S. 2—Representativeness Revisited: Attribute Substitution in Intuitive Judgment. In Heuristics and Biases The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plate, T. Holographic reduced representations. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1995, 6, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechesov, A.; Dorokhov, I.; Ruponen, J. Virtual Cities: From Digital Twins to Autonomous AI Societies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13866–13903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruponen, J.; Dorokhov, I.; Barykin, S.E.; Sergeev, S.; Nechesov, A. Metaverse Architectures: Hypernetwork and Blockchain Synergy. In Proceedings of the MathAI, Sochi, Russia, 24 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dorokhov, I.; Ruponen, J.; Shutsky, R.; Nechesov, A. Time-Exact Multi-Blockchain Architectures for Trustworthy Multi-Agent Systems. In Proceedings of the MathAI, Sochi, Russia, 24 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | SDM-encoded event trace (binary vector + metadata) |

| Semantic Memory | Transformer parameters and embeddings representing structured knowledge |

| Consolidation | Shadow Transformer fine-tuning on SDM replay to update active transformer |

| Atomic Swap | Replacement of the active transformer (S2A) with shadow transformer (S2B) using version control guarantees |

| Replay | Retrieval of historical SDM events for training or consolidation |

| Active Transformer (S2A) | Transformer module serving real-time user interactions and receiving SDM recall as context |

| Shadow Transformer (S2B) | Transformer module trained asynchronously using SDM replay, replacing S2A upon validation |

| Access Radius (r) | Hamming distance threshold defining which SDM memory locations are activated |

| Binary Encoding | Conversion of dense transformer embeddings into sparse high-dimensional binary vectors for SDM storage |

| Sparsification | Process enforcing low-activity representations, reducing interference and increasing memory capacity |

| Semantic Encoding | Structured latent code reflecting conceptual similarity for SDM retrieval |

| Locality-Preserving Hashing | Mapping method ensuring geometrically similar input patterns activate nearby SDM locations |

| Quantization | Discretization or compression of vectors to reduce storage and memory footprint |

| Stabilization/Preconditioning | Transformations that make SDM representations robust, noise-tolerant, and well-conditioned |

| Match Ratio | Retrieval accuracy metric in SDM benchmarks |

| BER (Bit Error Rate) | Fraction of corrupted bits in a query compared to stored SDM pattern |

| Voting Mechanism | Aggregation method in SDM modules to resolve noisy or ambiguous activations |

| Hierarchical Integration | Combining outputs from multiple SDM modules to form higher-level episodic representations |

| CALM | Cognitive architecture integrating SDM (System 1) with dual transformers (System 2) for continual learning |

| System 1/System 2 | SDM-based associative memory vs. transformer-based reasoning modules |

| Parameter | Values | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Vector Dimension | 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024 | Tests scaling from embedded to server deployment |

| Memory Locations Access Radius Factor | 500, 1K, 3K, 5K, 8K 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.78, 0.9 | Evaluates capacity vs. interference trade-offs Explores specificity vs. generalization spectrum |

| Reinforcement Cycles | 1, 5, 10, 15, 30, 50, 100 | Standard strengthening for reliable storage |

| Address Vector (Binary) | Payload | Confidence |

|---|---|---|

| 001010001000010100… | “person detected” | 0.87 |

| 111000000101100010… | “car detected” | 0.92 |

| 000100100000000001… | “no motion” | 0.95 |

| Regime | Radius Range | Match Ratio | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under-activation | 0.4–0.6 | No successful retrieval, recalled_ones = 0 | |

| Transition Zone | 0.6–0.9 | Unstable, configuration-dependent | |

| Over-activation | 1.0 | Perfect recall, full pattern recovery |

| Locations | Match Ratio | Latency (ms) | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1.0 | 0.090 | High |

| 1000 | 1.0 | 0.188 | Medium |

| 3000 | 1.0 | 0.564 | Medium |

| 5000 | 1.0 | 0.942 | Low |

| 8000 | 1.0 | 1.501 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nechesov, A.; Ruponen, J. CALM: Continual Associative Learning Model via Sparse Distributed Memory. Technologies 2025, 13, 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120587

Nechesov A, Ruponen J. CALM: Continual Associative Learning Model via Sparse Distributed Memory. Technologies. 2025; 13(12):587. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120587

Chicago/Turabian StyleNechesov, Andrey, and Janne Ruponen. 2025. "CALM: Continual Associative Learning Model via Sparse Distributed Memory" Technologies 13, no. 12: 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120587

APA StyleNechesov, A., & Ruponen, J. (2025). CALM: Continual Associative Learning Model via Sparse Distributed Memory. Technologies, 13(12), 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120587