Spectral Ripples in Normal and Electric Hearing Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Spectral Ripple Test

1.2. Spectral-Temporally Modulated Ripple Test (SMRT)

1.3. Modeling Approach

2. Materials and Methods

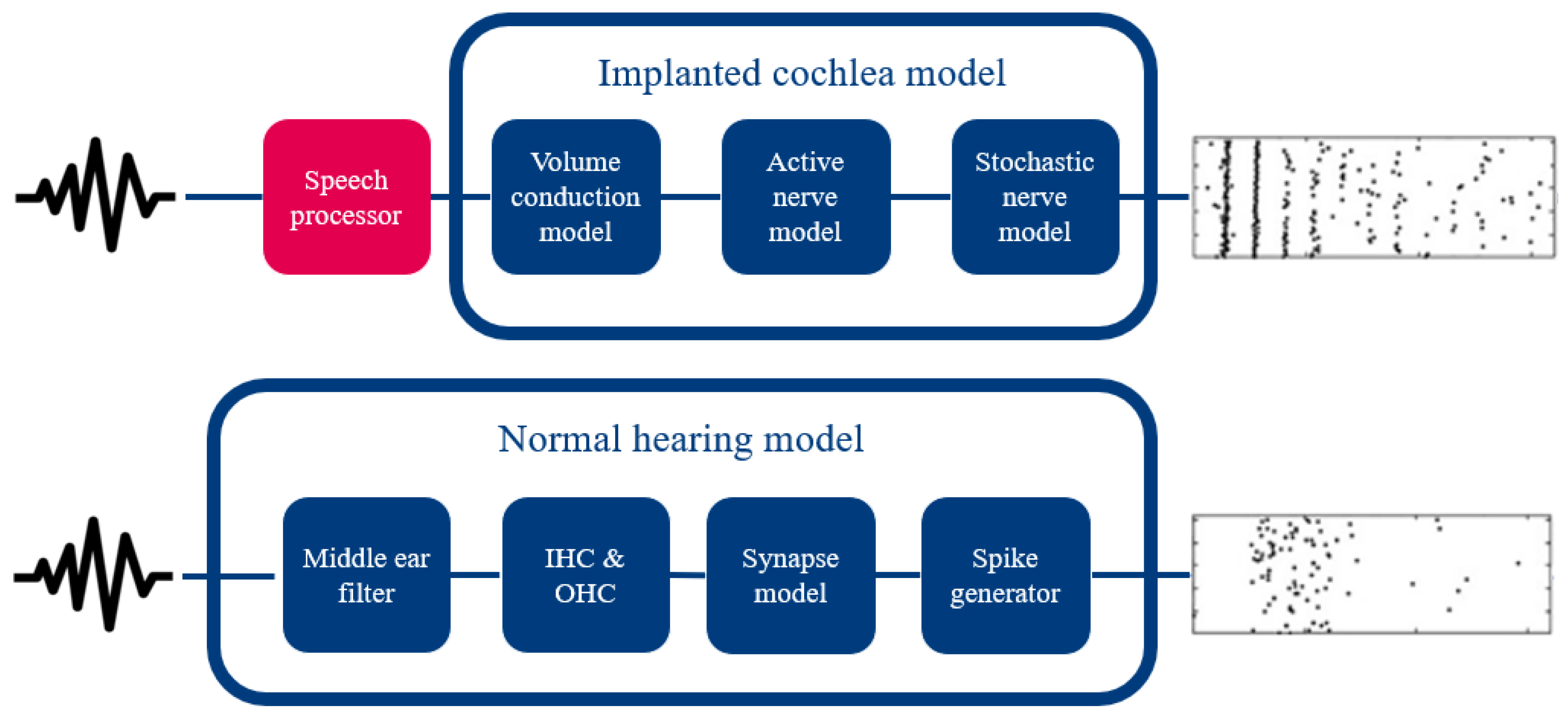

2.1. Electric Hearing

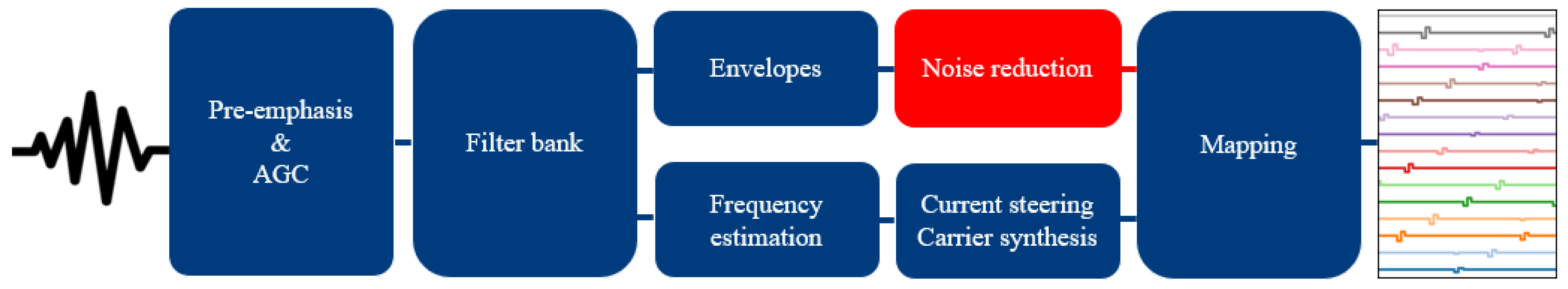

2.1.1. Speech Processor

2.1.2. The Implanted Cochlea Model

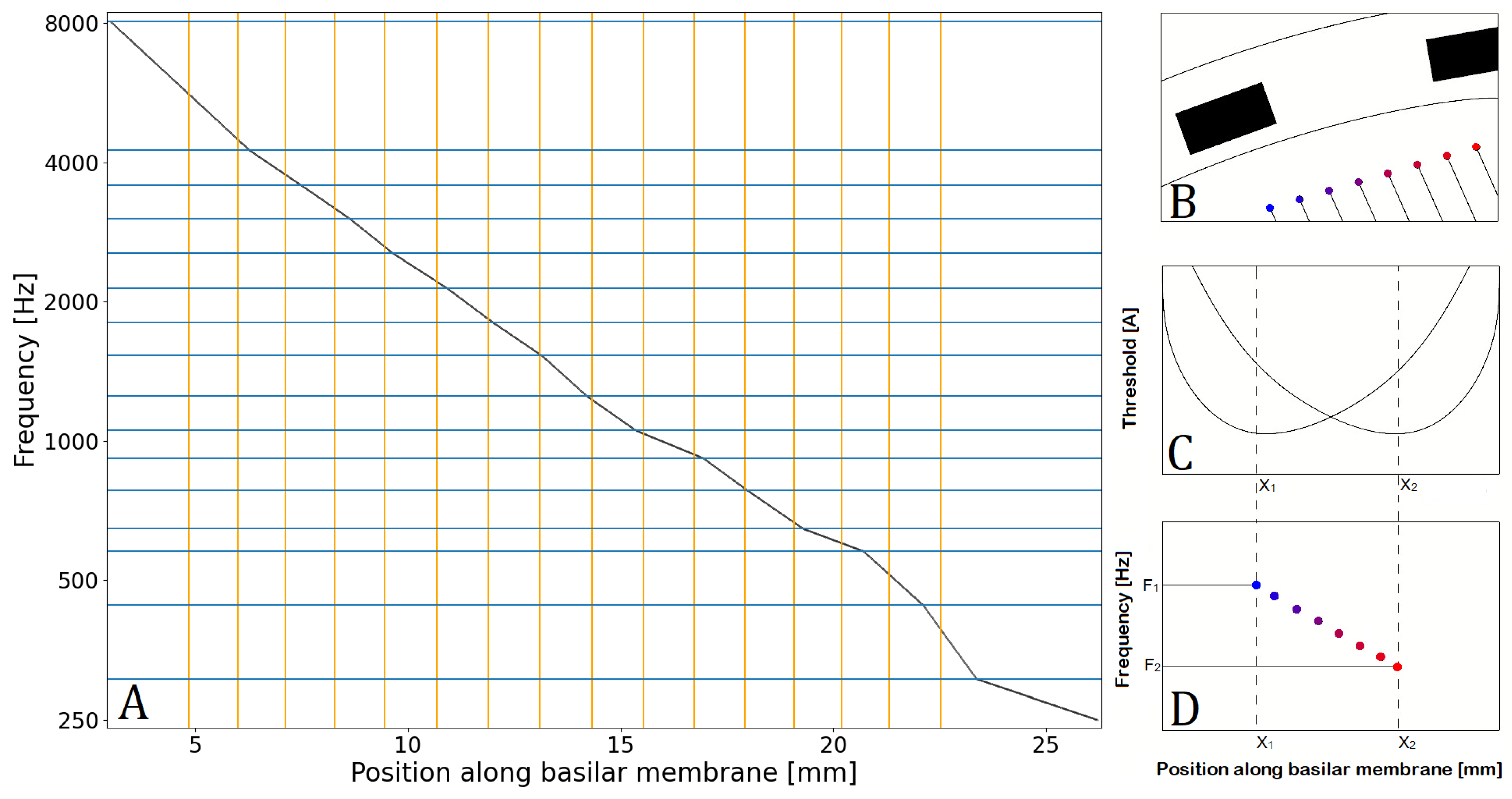

2.1.3. Fiber Frequency Allocation

2.2. Normal Hearing Model

2.3. Sounds

2.3.1. Spectral Ripple Test

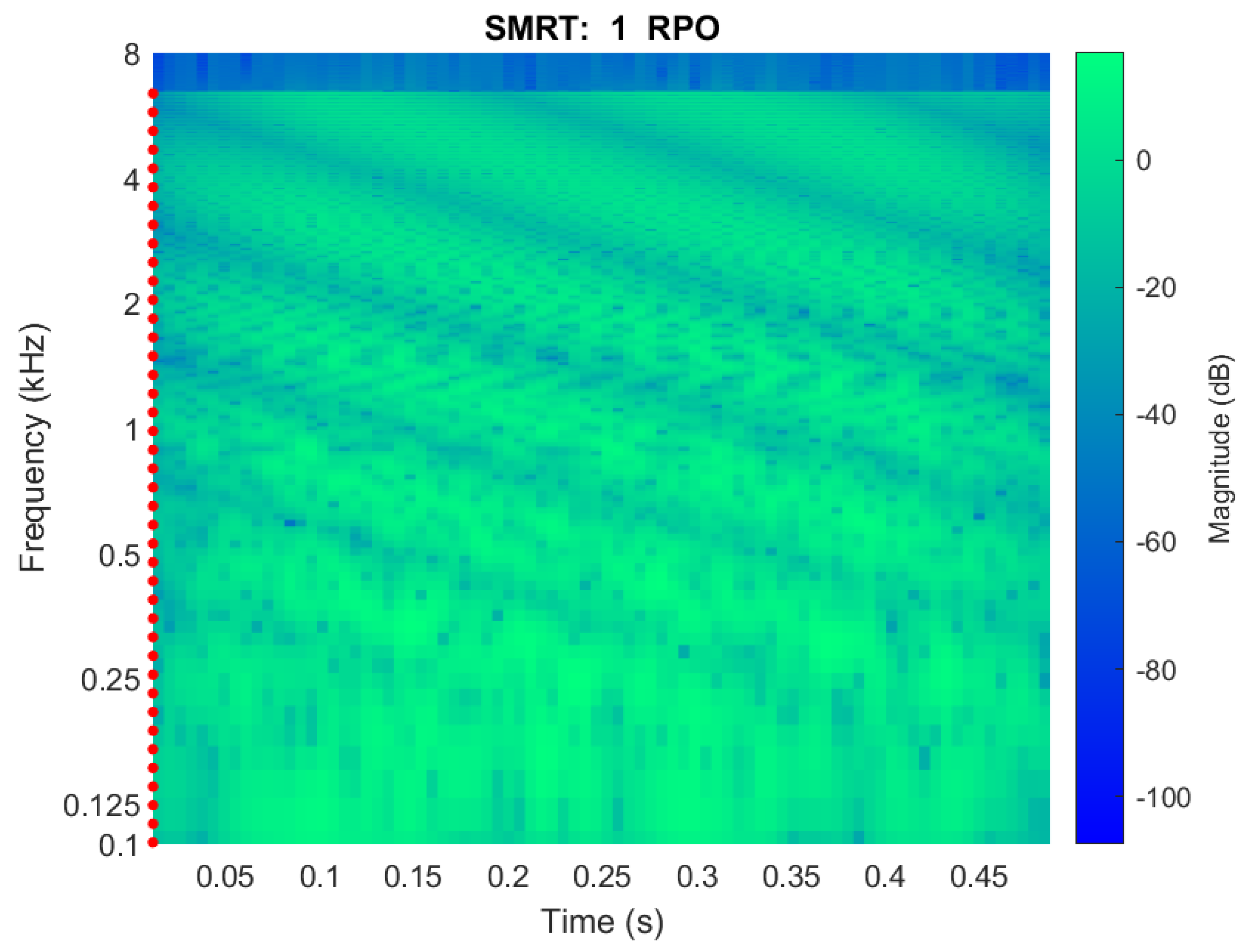

2.3.2. SMRT

2.4. Visualization

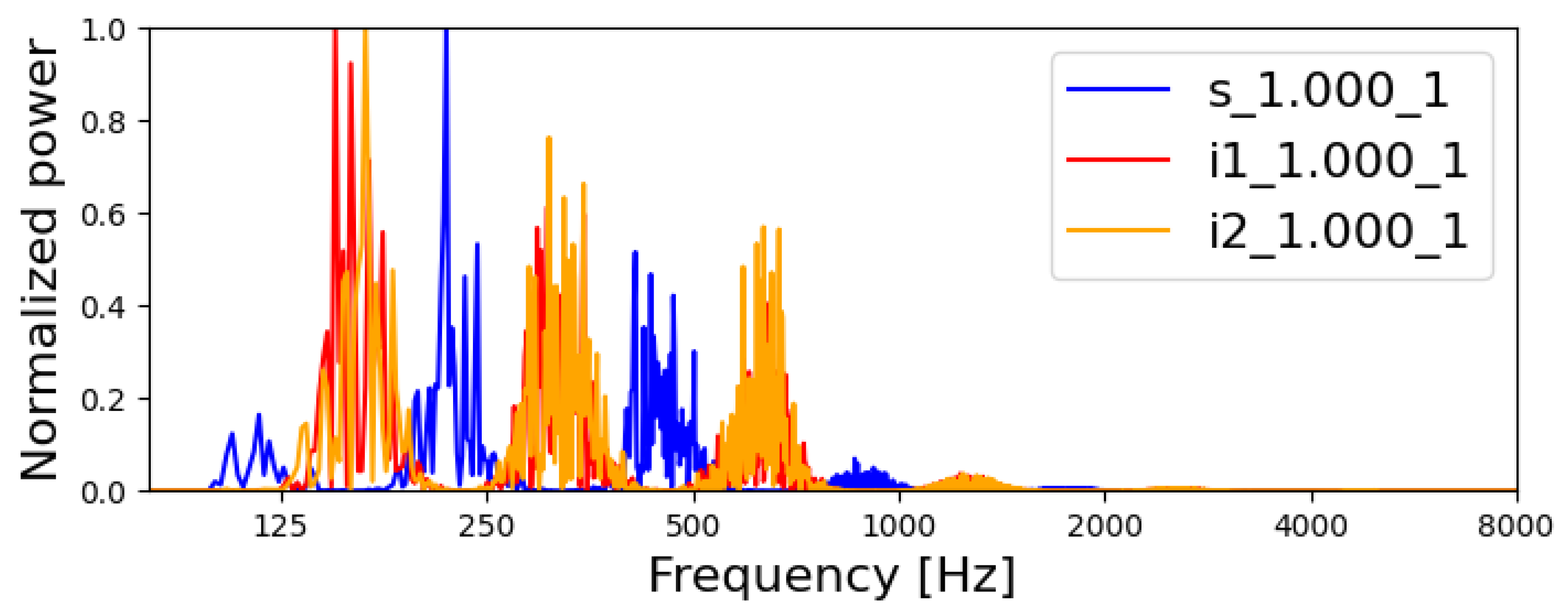

2.4.1. Spectrum

2.4.2. Neurogram

2.5. Spectral-Ripple Threshold

3. Results

3.1. Spectral Ripple Test

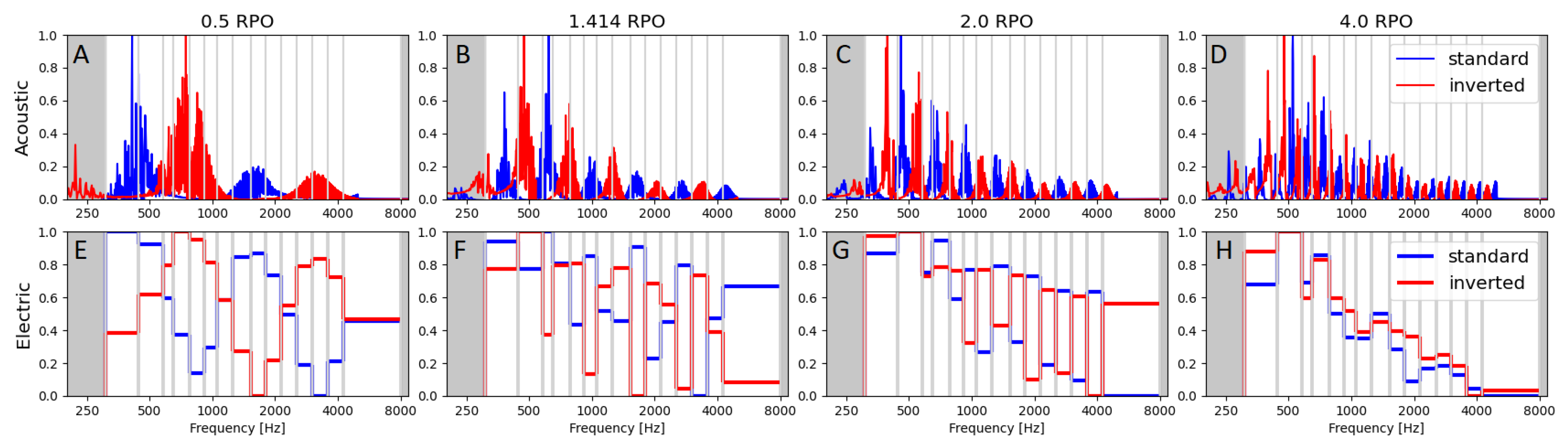

3.1.1. Acoustic and Electric Spectra

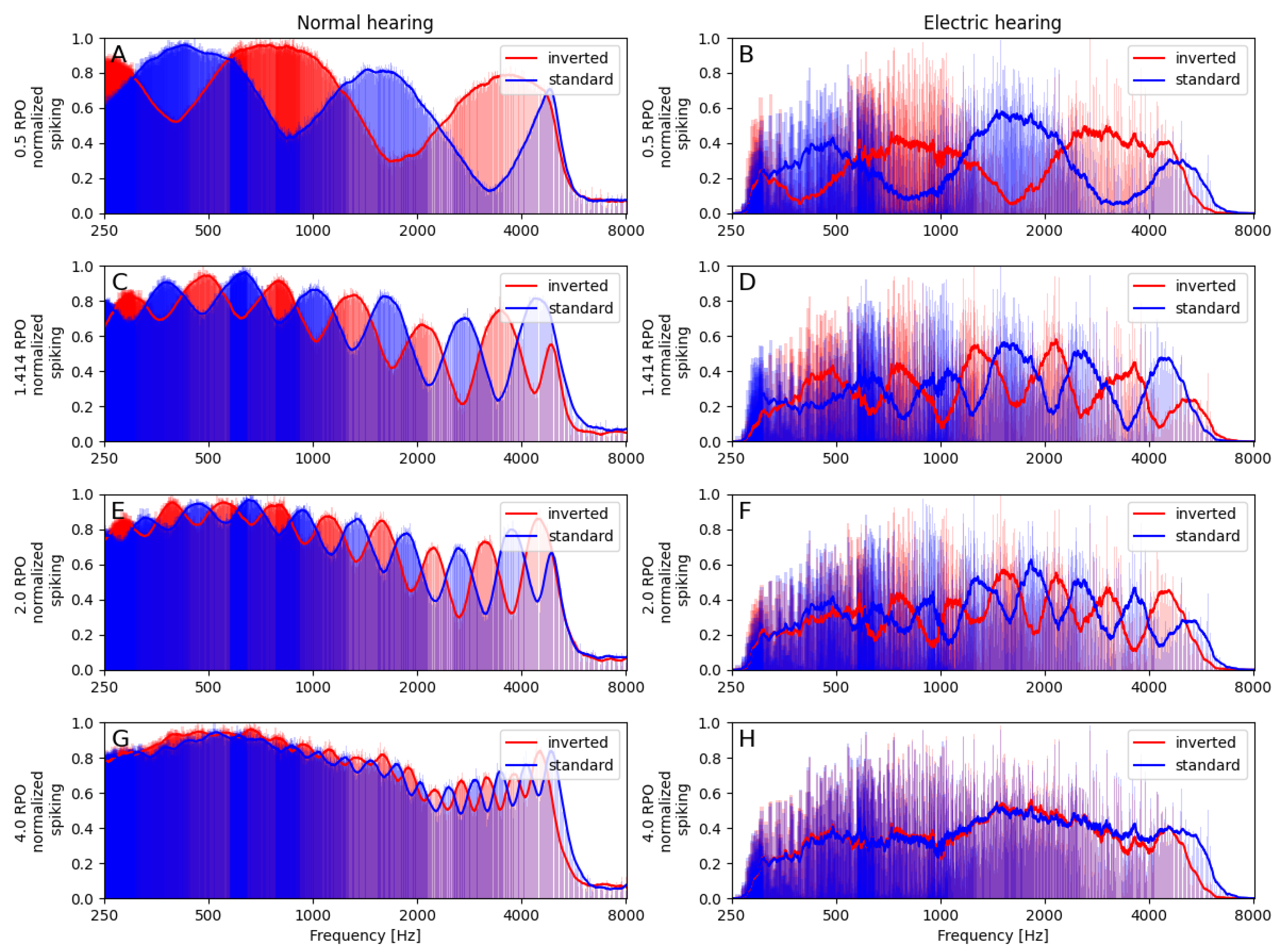

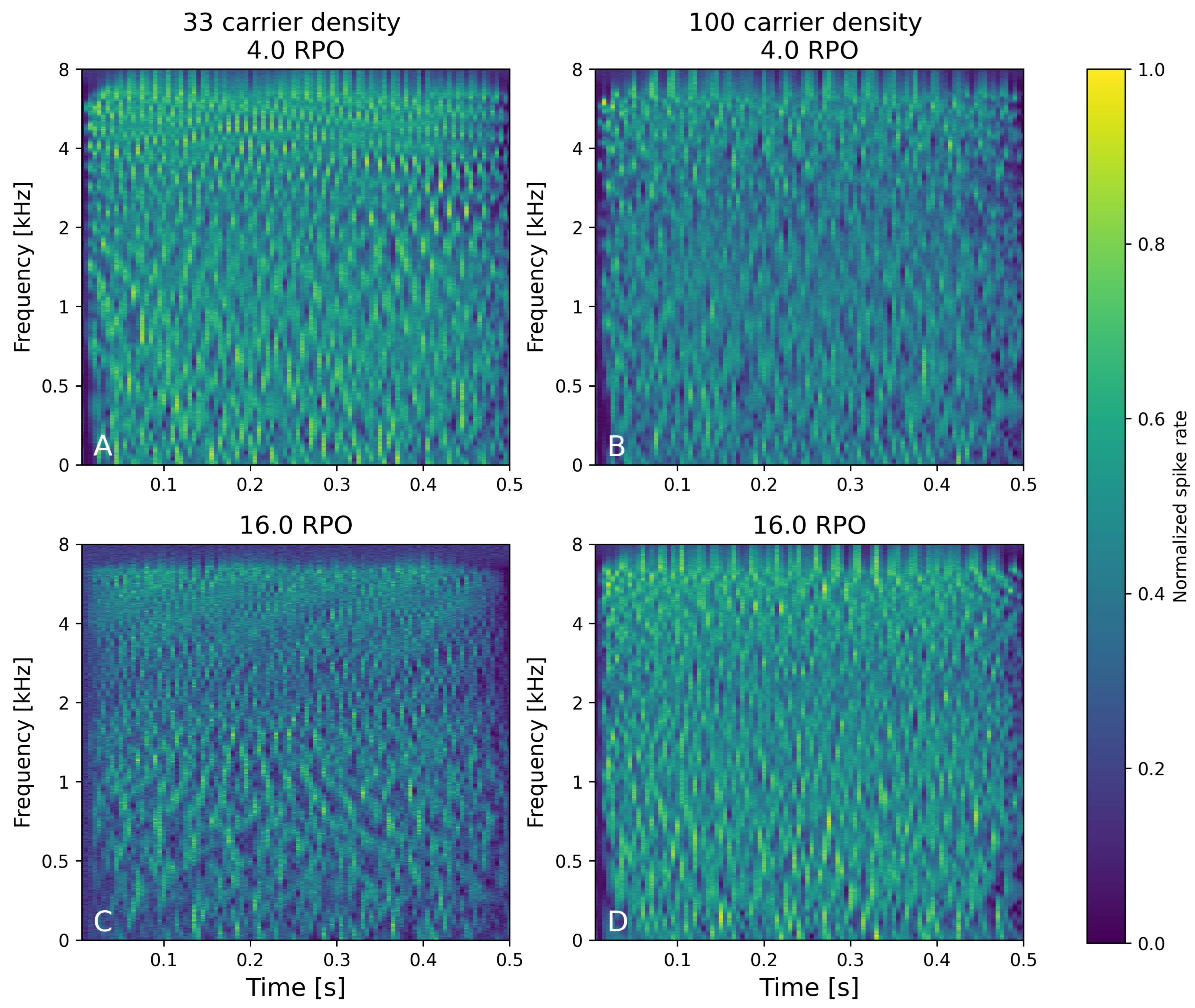

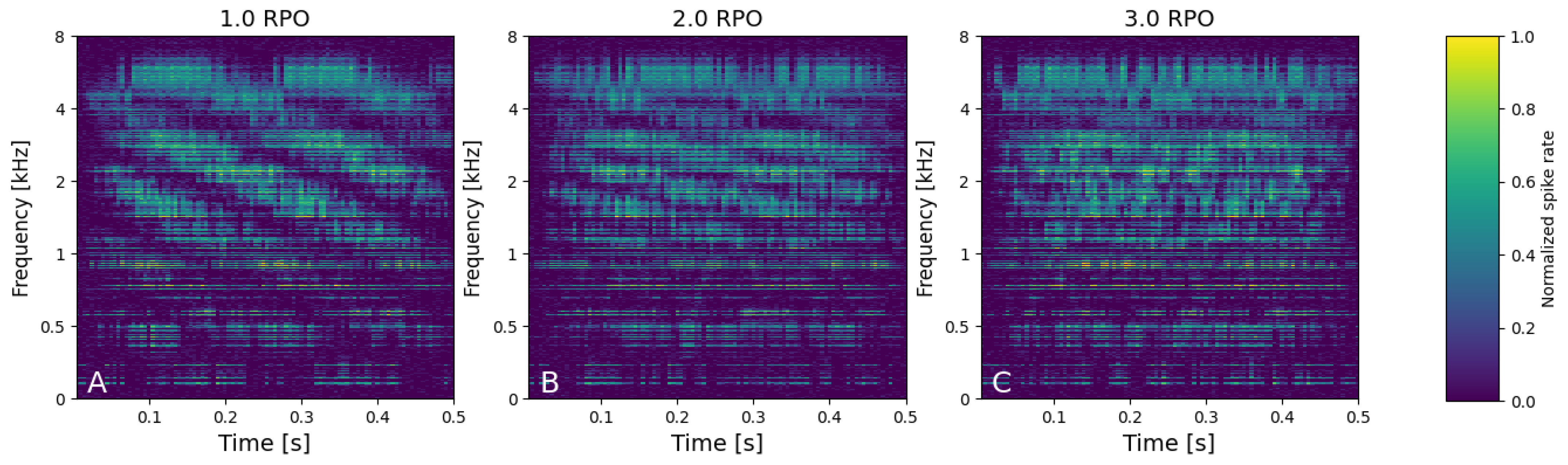

3.1.2. Neural Spectra

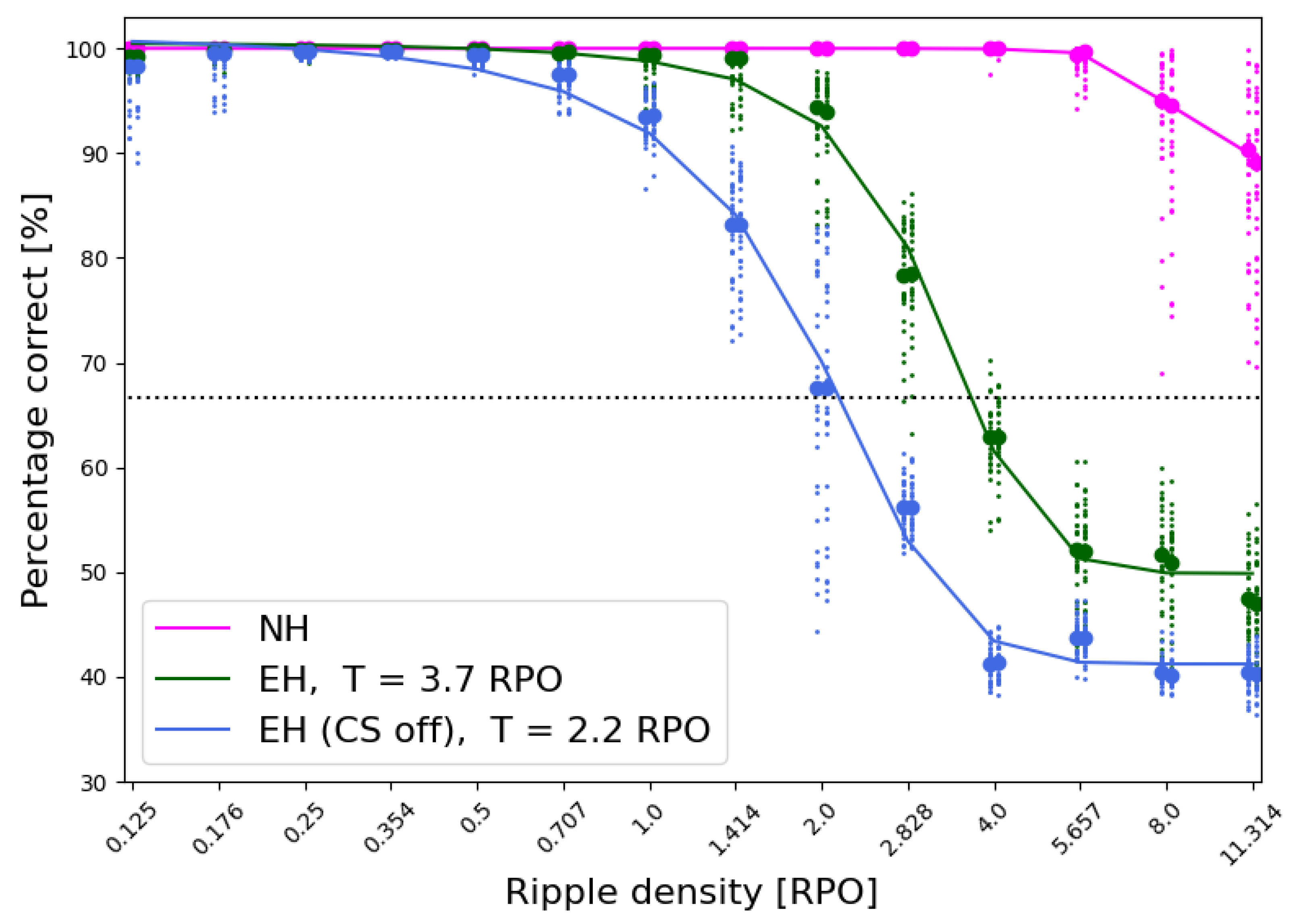

3.1.3. Spectral Ripple Test Threshold

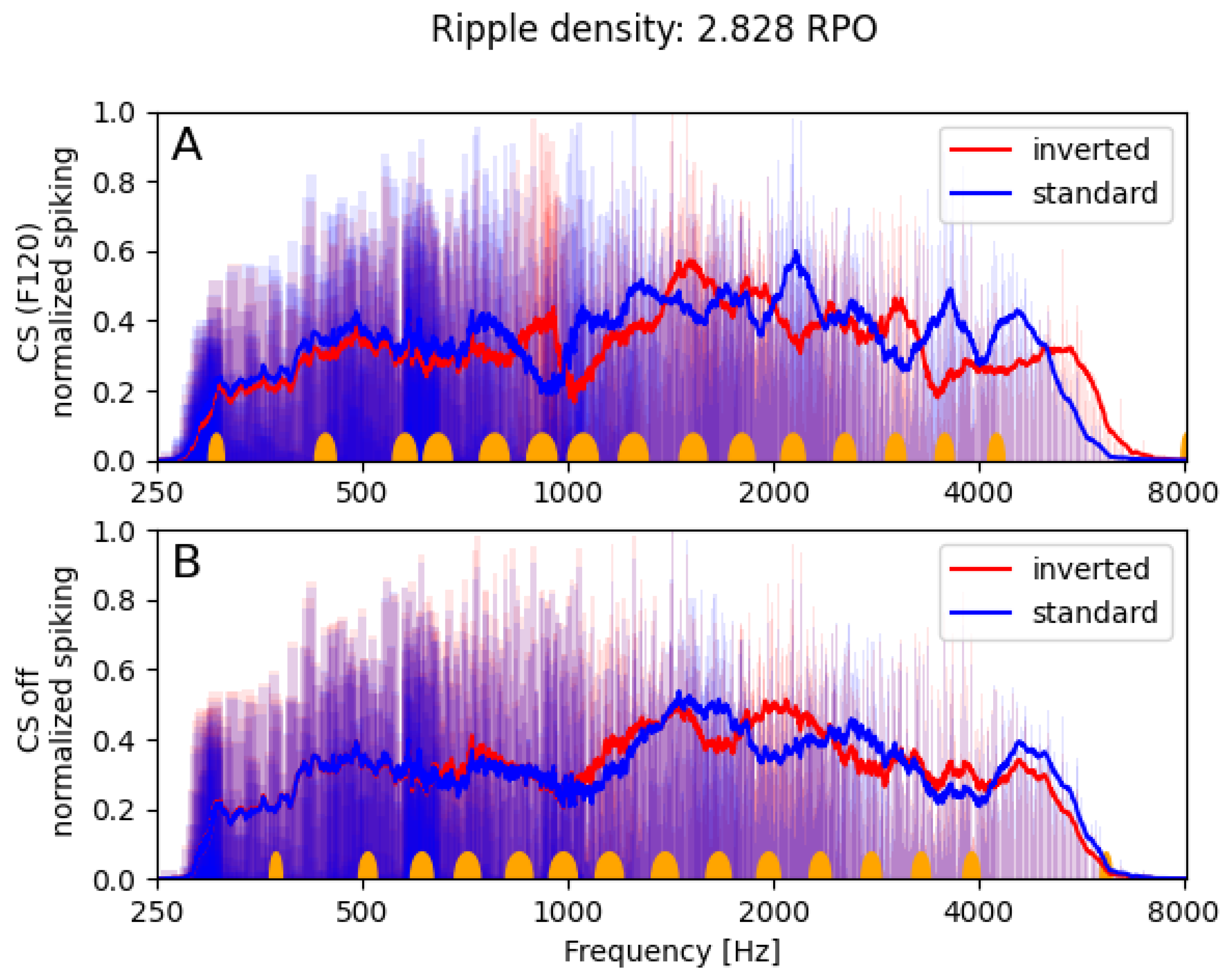

3.2. SMRT

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3AFC | 3-alternative forced choice |

| ACE | Advanced Combination Encoder |

| CPO | Carriers-per-octave |

| CI | Cochlear implant |

| CIS | Continuous interleaved sampling |

| F120 | Fidelity 120 |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| FS | Full scale |

| HiRes | High Resolution |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| RPO | Ripples-per-octave |

| SMRT | Spectral-temporally modulated ripple test |

| STRIPES | Spectro-temporal ripple for investigating processor effectiveness |

| T | Threshold |

Appendix A. Electric Hearing: Neural Parameters

| Parameter | Value (SD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute refractory period (ARP) | 0.0004 s (0.0001 s) | [24] |

| Relative refractory period (RRP) | 0.0008 s (0.0005 s) | [24] |

| Relative spread (RS) | 0.06 (0.04) | [24] |

| Accommodation rate () | 0.014 | [28] |

| Adaptation rate () | 19.996 | [28] |

| Accommodation amplitude () | 0.072 | [28] |

| Adaptation amplitude () | 7.142 | [28] |

| Fiber spacing | 9.6 μm (0.46 μm) | [25] |

| Spontaneous rate (SR) | 10 Hz |

References

- Budenz, C.L.; Cosetti, M.K.; Coelho, D.H.; Birenbaum, B.; Babb, J.; Waltzman, S.B.; Roehm, P.C. The effects of cochlear implantation on speech perception in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calmels, M.N.; Saliba, I.; Wanna, G.; Cochard, N.; Fillaux, J.; Deguine, O.; Fraysse, B. Speech perception and speech intelligibility in children after cochlear implantation. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2004, 68, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, A.; Nittrouer, S. Speech perception in noise by children with cochlear implants. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2013, 56, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterman, B.L.; Domico, E.H. Speech recognition in background noise of cochlear implant patients. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2002, 126, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P.E.; Ruhl, D.S.; Camacho, M.; Tolisano, A.M. Music appreciation after cochlear implantation in adult patients: A systematic review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 158, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, D.R. Plasticity in the auditory system. Hear. Res. 2018, 362, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, L.A.; Turner, C.W.; Erenberg, S.R.; Gantz, B.J. Changes in pitch with a cochlear implant over time. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2007, 8, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, L.R.; Green, D.M. Detection of changes in spectral shape: Uniform vs. non-uniform background spectra. Hear. Res. 1988, 34, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.A.; Turner, C.W. The resolution of complex spectral patterns by cochlear implant and normal-hearing listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003, 113, 2861–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.H.; Drennan, W.R.; Rubinstein, J.T. Spectral-ripple resolution correlates with speech reception in noise in cochlear implant users. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2007, 8, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.S.; Nelson, D.A.; Kreft, H.; Nelson, P.B.; Oxenham, A.J. Comparing spatial tuning curves, spectral ripple resolution, and speech perception in cochlear implant users. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 130, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.S.; Oxenham, A.J.; Nelson, P.B.; Nelson, D.A. Assessing the role of spectral and intensity cues in spectral ripple detection and discrimination in cochlear-implant users. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2012, 132, 3925–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.H.; Noble, J.H.; Camarata, S.M.; Sunderhaus, L.W.; Dwyer, R.T.; Dawant, B.M.; Dietrich, M.S.; Labadie, R.F. The relationship between spectral modulation detection and speech recognition: Adult versus pediatric cochlear implant recipients. Trends Hear. 2018, 22, 2331216518771176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, M.B.; O’Brien, G. Distortion of spectral ripples through cochlear implants has major implications for interpreting performance scores. Ear Hear. 2022, 43, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drennan, W.R.; Won, J.H.; Nie, K.; Jameyson, E.; Rubinstein, J.T. Sensitivity of psychophysical measures to signal processor modifications in cochlear implant users. Hear. Res. 2010, 262, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aronoff, J.M.; Landsberger, D.M. The development of a modified spectral ripple test. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, EL217–EL222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadpour, M.; McKay, C.M. A psychophysical method for measuring spatial resolution in cochlear implants. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2012, 13, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, J.M.; Horn, D.L.; Noble, A.R.; Rubinstein, J.T. Spectral aliasing in an acoustic spectral ripple discrimination task. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 147, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narne, V.K.; Sharma, M.; Van Dun, B.; Bansal, S.; Prabhu, L.; Moore, B.C. Effects of spectral smearing on performance of the spectral ripple and spectro-temporal ripple tests. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 140, 4298–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, M.; Yu, J.; Aronoff, J.M. Comparison of the spectral-temporally modulated ripple test with the Arizona Biomedical Institute Sentence Test in cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2017, 38, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddi, Z.; Lotfi, Y.; Moossavi, A.; Bakhshi, E.; Hashemi, S.B. Correlation between auditory spectral resolution and speech perception in children with cochlear implants. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 44, 382. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, I.C.; Erfani, Y.; Zilany, M.S. A phenomenological model of the synapse between the inner hair cell and auditory nerve: Implications of limited neurotransmitter release sites. Hear. Res. 2018, 360, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkman, R.K.; Briaire, J.J.; Frijns, J.H. Current focussing in cochlear implants: An analysis of neural recruitment in a computational model. Hear. Res. 2015, 322, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gendt, M.J.; Briaire, J.J.; Kalkman, R.K.; Frijns, J.H. A fast, stochastic, and adaptive model of auditory nerve responses to cochlear implant stimulation. Hear. Res. 2016, 341, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkman, R.K.; Briaire, J.J.; Dekker, D.M.; Frijns, J.H. The relation between polarity sensitivity and neural degeneration in a computational model of cochlear implant stimulation. Hear. Res. 2022, 415, 108413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briaire, J.J.; Frijns, J.H. 3D mesh generation to solve the electrical volume conduction problem in the implanted inner ear. Simul. Pract. Theory 2000, 8, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijns, J.H.; Briaire, J.J.; Schoonhoven, R. Integrated use of volume conduction and neural models to simulate the response to cochlear implants. Simul. Pract. Theory 2000, 8, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nobel, J.; Martens, S.S.; Briaire, J.J.; Bäck, T.H.; Kononova, A.V.; Frijns, J.H. Biophysics-inspired spike rate adaptation for computationally efficient phenomenological nerve modeling. Hear. Res. 2024, 447, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, W.; Litvak, L.; Edler, B.; Ostermann, J.; Büchner, A. Signal processing strategies for cochlear implants using current steering. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2009, 2009, 531213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.A.; Briaire, J.J.; Frijns, J.H. Take-Home Trial Comparing Fast Fourier Transformation-Based and Filter Bank-Based Cochlear Implant Speech Coding Strategies. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 7915042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Jagt, M.A.; Briaire, J.J.; Verbist, B.M.; Frijns, J.H. Comparison of the HiFocus Mid-Scala and HiFocus 1J electrode array: Angular insertion depths and speech perception outcomes. Audiol. Neurotol. 2017, 21, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronoff, J.M.; Staisloff, H.E.; Kirchner, A.; Lee, D.H.; Stelmach, J. Pitch matching adapts even for bilateral cochlear implant users with relatively small initial pitch differences across the ears. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2019, 20, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, L.A.; Turner, C.W.; Karsten, S.A.; Gantz, B.J. Plasticity in human pitch perception induced by tonotopically mismatched electro-acoustic stimulation. Neuroscience 2014, 256, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlyon, R.P.; Macherey, O.; Frijns, J.H.; Axon, P.R.; Kalkman, R.K.; Boyle, P.; Baguley, D.M.; Briggs, J.; Deeks, J.M.; Briaire, J.J.; et al. Pitch comparisons between electrical stimulation of a cochlear implant and acoustic stimuli presented to a normal-hearing contralateral ear. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2010, 11, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nobel, J.; Briaire, J.J.; Baeck, T.H.; Kononova, A.V.; Frijns, J.H. From Spikes to Speech: NeuroVoc–A Biologically Plausible Vocoder Framework for Auditory Perception and Cochlear Implant Simulation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.03959. [Google Scholar]

- Shera, C.A.; Guinan, J.J., Jr.; Oxenham, A.J. Revised estimates of human cochlear tuning from otoacoustic and behavioral measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 3318–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D.; Dillon, H.; Tran, K.; Arlinger, S.; Wilbraham, K.; Cox, R.; Hagerman, B.; Hetu, R.; Kei, J.; Lui, C.; et al. An international comparison of long-term average speech spectra. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994, 96, 2108–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.J.; Fitter, M.J. What is the best index of detectability? Psychol. Bull. 1973, 80, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Geisler, W.S. Methods to integrate multinormals and compute classification measures. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.14331. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, N.A.; Creelman, C.D. Detection Theory: A User’s Guide; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo, L.T. On a signal detection approach to m-alternative forced choice with bias, with maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches to estimation. J. Math. Psychol. 2012, 56, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.M.; Swets, J.A. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics; Wiley New York: New York, NY, USA, 1966; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom, A.A.; Prins, N. Psychophysics: A Practical Introduction; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, B.A.; Turner, C.W.; Behrens, A. Spectral peak resolution and speech recognition in quiet: Normal hearing, hearing impaired, and cochlear implant listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 118, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drennan, W.R.; Anderson, E.S.; Won, J.H.; Rubinstein, J.T. Validation of a clinical assessment of spectral-ripple resolution for cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, e92–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipscheer, B.; Briaire, J.J.; Frijns, J.H. Characterization of a Psychophysical Test Battery for the Evaluation of Novel Speech Coding Strategies in Cochlear Implants. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the Conference on Implantable Auditory Prosthesis. Conference on Implantable Auditory Prosthesis, Tahoe, CA, USA, 9–14 July 2023; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Archer-Boyd, A.W.; Southwell, R.V.; Deeks, J.M.; Turner, R.E.; Carlyon, R.P. Development and validation of a spectro-temporal processing test for cochlear-implant listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2018, 144, 2983–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamacher, V. Signalverarbeitungsmodelle des Elektrisch Stimulierten Gehors. Ph.D. Thesis, RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Electric Hearing | Normal Hearing |

|---|---|---|

| Number of fibers per frequency | 1 | 50 |

| Loudness | 65 dB SPL (FS 111.6 dB) | 65 dB RMS SPL |

| Spontaneous rate [spikes/s] | 10 | 0.1 (n = 10), 4 (n = 10), 70 (n = 30) |

| Analysis Band | Lower Edge | Upper Edge |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 306 | 442 |

| 2 | 442 | 578 |

| 3 | 578 | 646 |

| 4 | 646 | 782 |

| 5 | 782 | 918 |

| 6 | 918 | 1054 |

| 7 | 1054 | 1257 |

| 8 | 1257 | 1529 |

| 9 | 1529 | 1801 |

| 10 | 1801 | 2141 |

| 11 | 2141 | 2549 |

| 12 | 2549 | 3025 |

| 13 | 3025 | 3568 |

| 14 | 3568 | 4248 |

| 15 | 4248 | 8054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martens, S.S.M.; Briaire, J.J.; Frijns, J.H.M. Spectral Ripples in Normal and Electric Hearing Models. Technologies 2025, 13, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13110505

Martens SSM, Briaire JJ, Frijns JHM. Spectral Ripples in Normal and Electric Hearing Models. Technologies. 2025; 13(11):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13110505

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartens, Savine S. M., Jeroen J. Briaire, and Johan H. M. Frijns. 2025. "Spectral Ripples in Normal and Electric Hearing Models" Technologies 13, no. 11: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13110505

APA StyleMartens, S. S. M., Briaire, J. J., & Frijns, J. H. M. (2025). Spectral Ripples in Normal and Electric Hearing Models. Technologies, 13(11), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13110505