1. Introduction

In December 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak began in the city of Wuhan, Hubei region, China. As of 20 March 2020, the virus had already affected more than 500,000 people in more than 60 countries, with around 16% deaths due to this virus. Around 5% of the infected patients were in a critical or serious condition, while there seemed to be a recovery rate of 84% (

Worldometer 2020).

On 3 February 2020, the Shanghai stock market plunged 8% following the general distress over COVID-19 in China. This shocking disruption rapidly spread to international financial markets. For example, the United States (U.S.) stock prices logged their lowest level in February and the S&P 500 plummeted 4.4% on 28 February 2020. Initially ignored by many countries, the COVID-19 effect was raising serious concerns due to its rapid propagation outside China (

Albulescu 2020a,

2020b).

Can this be the “worst financial crisis the world has ever seen since 1929?” This is what some analysts, such as

Elliot (

2020), believe. He noted in his article that Stephen

Isaccs (

2020) of Alvine Capital highlighted that COVID-19 is “unprecedented”, with record levels of leverage and overbought stocks. Moreover, he highlights that both Goldman Sachs and HIS Markit revised their forecasts downwards for the world’s real GDP growth in 2020 to 1.25% and 0.7% respectively

1.

Herron and Hajric (

2020) highlighted the panic mode in the markets and noted that stock markets plunged 12% amid COVID-19 fears. However,

Desjardins (

2020) showed that some markets (of holdings, such as Zoom Video Communications (ZM), Domino Pizza (DPZ), Campbell Soup Company (CPB), Teladoc Health, Inc. (TDOC), The Clorox Company (CLX), Everbridge, Inc. (EVBG) and Virtu Financial, Inc. (VIRT)) were thriving from this situation by creating a vortex to suck up the alternate market universe, which he called “the pandemic economy”. He said that, on average, these companies saw an upward bump of 12.7%.

As we note, during a pandemic period, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the factors affecting portfolios change; therefore, to achieve a well-designed portfolio, we need to understand the impact of cases and deaths on market risk and the stock markets.

2. Literature Review

Most studies carried out by authors, such as

Haacker (

2004),

Lee and McKibbin (

2004),

Loh (

2006),

Kauffman and Weerapana (

2006),

McKibbin and Fernando (

2020),

Fernandes (

2020),

Albulescu (

2020a),

Albulescu (

2020b),

Ramelli and Wagner (

2020b),

Zeren and Hızarcı (

2020), on pandemics and their effect on the economies and financial markets relate mainly to HIV/AIDS and SARS. However, there is a small but growing literature emerging on the impact of COVID-19 on the stock markets.

In his research,

Fernandes (

2020) highlights that this pandemic (COVID-19) differs from other global crises since it is a global pandemic, which does not focus only on the low-to-middle-income countries, the interest rates are at historical lows, the world is much more integrated than before and there are spillover effects throughout the supply chains that disrupt the demand and supply.

Haacker (

2004) showed that HIV/AIDS affected economic units, such as businesses, households, governments, labour supply decisions, labour efficiency and household income. He noted that business costs, public expenditure on healthcare and support of disabled and children orphaned by AIDS increased, causing budget deficits in certain countries.

Kauffman and Weerapana (

2006) revealed that bad news about HIV/AIDS in the Republic of South Africa had a negative effect on the value of the South African rand against the U.S. dollar.

The SARS epidemic had significant effects on various economies that were caused by the reductions in total demand for various goods and services, increases in business operating costs and increases in each country’s risks, which in turn increased the risk premiums. Although the number of infected persons and deaths due to this epidemic was not the same in all countries, the impact on a global scale, which resulted in a cost of 54 billion USD in 2003, was significant (

Lee and McKibbin 2004). The capital outflow in Hong Kong and China rose to 1.4% and 0.8% of GDP, respectively, and their risk premium was increased by 200 basis points (

Lee and McKibbin 2004).

On the other hand,

Loh (

2006) showed that the SARS pandemic increased airline stocks’ volatility with lower mean returns in certain countries. However, it had a negligible impact on the mean stock market returns and had no significant long-run implications. The author highlighted that airline stocks tended to take on an “aggressive” characteristic in the presence of any pandemic outbreak.

McKibbin and Fernando (

2020) used the G-Cubed multi-country model to calculate the effect of COVID-19 on the global economy in the early stages of the pandemic while the outbreak was still only in China. They explored seven different scenarios of how COVID-19 might develop and influence macroeconomic outcomes and financial markets using global hybrid dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) and computable general equilibrium (CGE) models developed by

McKibbin and Wilcoxen (

1999,

2013). They found that the impact of the spread of COVID-19 on the financial risk in the United States was high relative to the G-20 and OECD countries and that England and several developing countries, such as Argentina, South Africa and Turkey, had a higher degree of relative financial risk resulting from the spreading of COVID-19 than the United States. Therefore, they note that the spreading of COVID-19 to these countries would deeply affect the financial markets. Using these scenarios, they demonstrated that even a controlled outbreak could have a significant impact on the global economy in the short run and that the costs may be avoided by greater investment in public health systems.

Fernandes (

2020) analysed the economic effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on the world economy as of 22 March 2020. The author noted that most stock markets on that date collapsed and registered their largest recorded one-day falls on record; some well-known companies saw their stock prices fall by more than 80% in a few days. He noted that in the United States, stock markets saw their worst performance with a fall of over 25% and British markets had the largest hit of all developed markets with a decline of more than 35%. He further highlighted that the impact of the outbreak of this pandemic (COVID-19) was being underestimated and could not be compared to other pandemics, such as SARS and the 2008/2009 financial crisis. His findings demonstrated that in a mild scenario, GDP would take a hit ranging from 3–5% depending on the country and that specifically service-oriented and tourism-reliant economies would be negatively affected, with the largest job losses.

In the first 40 days of international monitoring of the COVID-19 outbreak,

Albulescu (

2020a) found in his study that the death ratio positively influenced the VIX and that this influencing effect was stronger outside China. In another study,

Albulescu (

2020b) found that following the outbreak of the virus infections resulted in a marginally negative impact on crude oil prices in the long run. Moreover, COVID-19 also has an indirect effect on crude oil prices when the volatility of the financial markets was amplified.

Ramelli and Wagner (

2020b) noted that after the outbreak of COVID-19 in China and the United States, industry stock returns faced disruptions. Stock returns in some sectors, such as telecom services, healthcare and software services, were on the increase in China and the United States. However, stock returns in other sectors, such as energy, transportation, insurance, real estate, retailing and automobiles, were on the decrease.

Ramelli and Wagner (

2020a,

2020b) stated that the Chinese and the U.S. stock markets were quick to respond to concerns about the possible economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and explain that this resulted because the investors became increasingly worried about corporate debt and liquidity, which mutated into an economic crisis that was augmented through financial channels.

Zeren and Hızarcı (

2020) investigated the co-integration relationship between COVID-19 cases and some selected stock markets. They used data between 23 January 2020 and 13 March 2020. Their findings showed that there was a co-integration relationship between the COVID-19 cases and the SSE, KOSPI and IBEX35, and no relationship with the FTSE MIB, CAC40 or DAX30 was found. This result showed the geographical effect of COVID-19 on stock markets as the virus spread to the European countries at the beginning of March.

Cheng (

2020) highlighted that stock investors underpriced the risk of the COVID-19 pandemic and showed that trading in the VIX futures market was a step behind in relating the risks. He noted that although the cases of COVID-19 were increasing rapidly in Europe starting in March and there were reports of community spreading and deaths in the United States, the S&P 500 had declined slightly, while the price of the VIX had risen by 42%.

Onali (

2020) investigated the impact of the COVID-19 cases and deaths on the U.S. stock market, specifically the Dow Jones and the S&P500 indices. He allowed for changes in trading volume and volatility expectations, as well as day-of-the-week effects. Using a GARCH(1,1) model on the data collected during the period from 8 to 9 April 2020, he found that, except for China (where reported cases had an effect), changes in the number of cases and deaths in the United States and six other countries strongly affected by the COVID-19 crisis did not have an impact on the U.S. stock market returns. However, he further noted that his findings evidenced a positive impact for some countries on the conditional heteroscedasticity of the Dow Jones and S&P500 returns, that the VAR models indicated that reported deaths in Italy and France had a negative impact on stock market returns, a positive impact on the VIX returns and that the magnitude of the negative impact of the VIX on stock market returns spiked threefold.

In their study,

Baker et al. (

2020) used textual analysis to quantify the impact of news on COVID-19 cases on the volatility in the stock market, specifically the Dow Jones index, using data up to 9 April 2020 for cases and deaths in the United States, China, France, Iran, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. They found that the volatility impact was much larger during this pandemic than during similar disease outbreaks and that the COVID-19 crisis had caused a change in the relationship between volatility expectations and stock market returns.

In a further study,

Yilmazkuday (

2020) investigated the impact of the number of deaths related to COVID-19 on the S&P500 index. He used daily data collected during the period between 31 December 2019 and 1 May 2020 and used a structural vector autoregression model, using a measure for the global economic activity, the spread between 10-year treasury maturity and the federal funds rate. The results showed that a 1% increase in the U.S. cumulative daily COVID-19 cases resulted in around a 0.01% cumulative reduction in the S&P 500 Index after one day and around a 0.03% reduction after one month, with the largest observations during March 2020.

Using data up to June 2020 from the aggregated stock market and the dividend futures,

Gormsen and Koijen (

2020a,

2020b) measured the investors’ expectations on economic growth as a response to the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent policy responses until June 2020. They showed that the growth expectations across maturities evolved and provided a simple model for understanding the joint dynamics of short-term dividend futures, stock markets and bond markets.

As noted from the literature, there are a limited number of papers that study the impact of COVID-19 cases on the VIX index and the impact of the VIX index on the major stock markets during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially using U.S. data.

3. Aim and Data

Therefore, given the above discussion and the uncertainties during this COVID-19 “pandemic economy”, we aimed to answer the following research questions: (1) What was the impact of COVID-19 data on the VIX index in the United States?

We hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Bad news on COVID cases and deaths in the United States did not influence the VIX index.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Bad news on COVID cases and deaths in the United States influenced the VIX index.

(2) What was the impact of the VIX on the major world stock exchanges during the same period?

We hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). As the VIX index increased, the major world stock exchange prices would also increase.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). As the VIX index increased, the major world stock exchange prices would decrease.

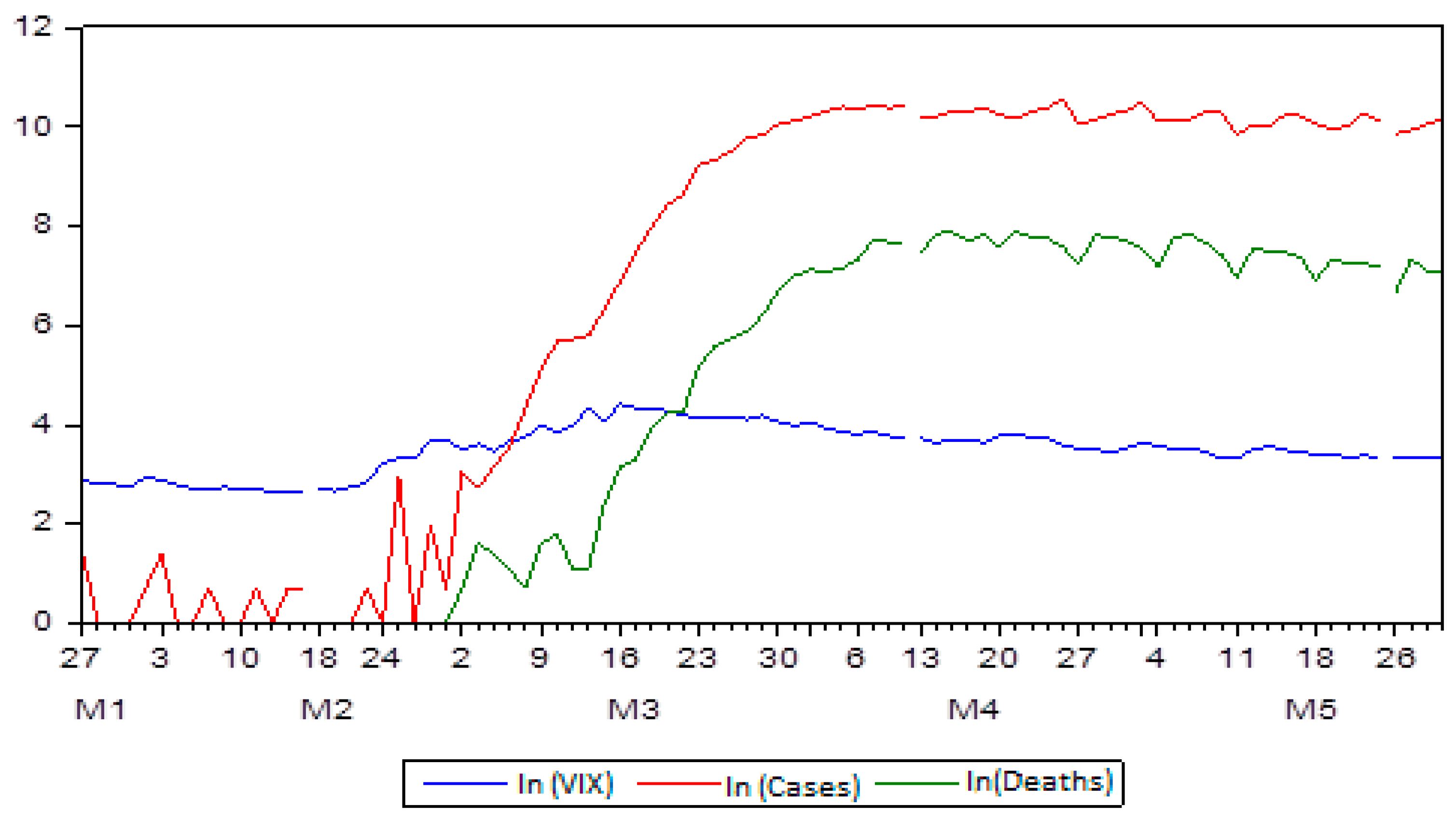

To address the first research question, we used daily new case and death numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Since the cases started to increase as of 27 January 2020 in the USA, we collected data for the period of 27 January 2020 to 29 May 2020 (the analysis period).

Then, to determine the VIX effect on the major stock exchanges during the COVID-19 pandemic period, we collected and analysed daily closing price data for the USA (DJIA), Germany (DAX), France (CAC40), England (FTSE100), China (SSEC), Japan (Nikkei225) and Italy (MIB) for the period between 2 January 2020 and 29 May 2020. The COVID-19 data was collected from

www.worldometers.info (accessed on 13 May 2021) (

Worldometer 2020), while the index data was collected from

www.investing.com (accessed on 13 May 2021) (

Investing 2020). We conducted the analysis presented below to determine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the VIX index and the effect of the VIX index on the major stock markets during the pandemic period.

This study is especially equally important for those portfolio and fund managers who build their portfolios around the market indexes and academics who study the effects of specific announcements. In addition, this can be of benefit to risk managers, underwriters and actuaries who might need to revise their measurements in line with new data and information and for portfolio diversification and portfolio management decisions. The research period was chosen to eliminate as much as possible any noise that may have been introduced due to pandemic fatigue and the news of vaccines and antiviral medicines since there was no fatigue yet and no news about the vaccines in this period; the concentration of everyone was on the element of uncertainty. We wanted to specifically understand how news of the widespread pandemic affected the so-called fear index and major markets.

5. Conclusions

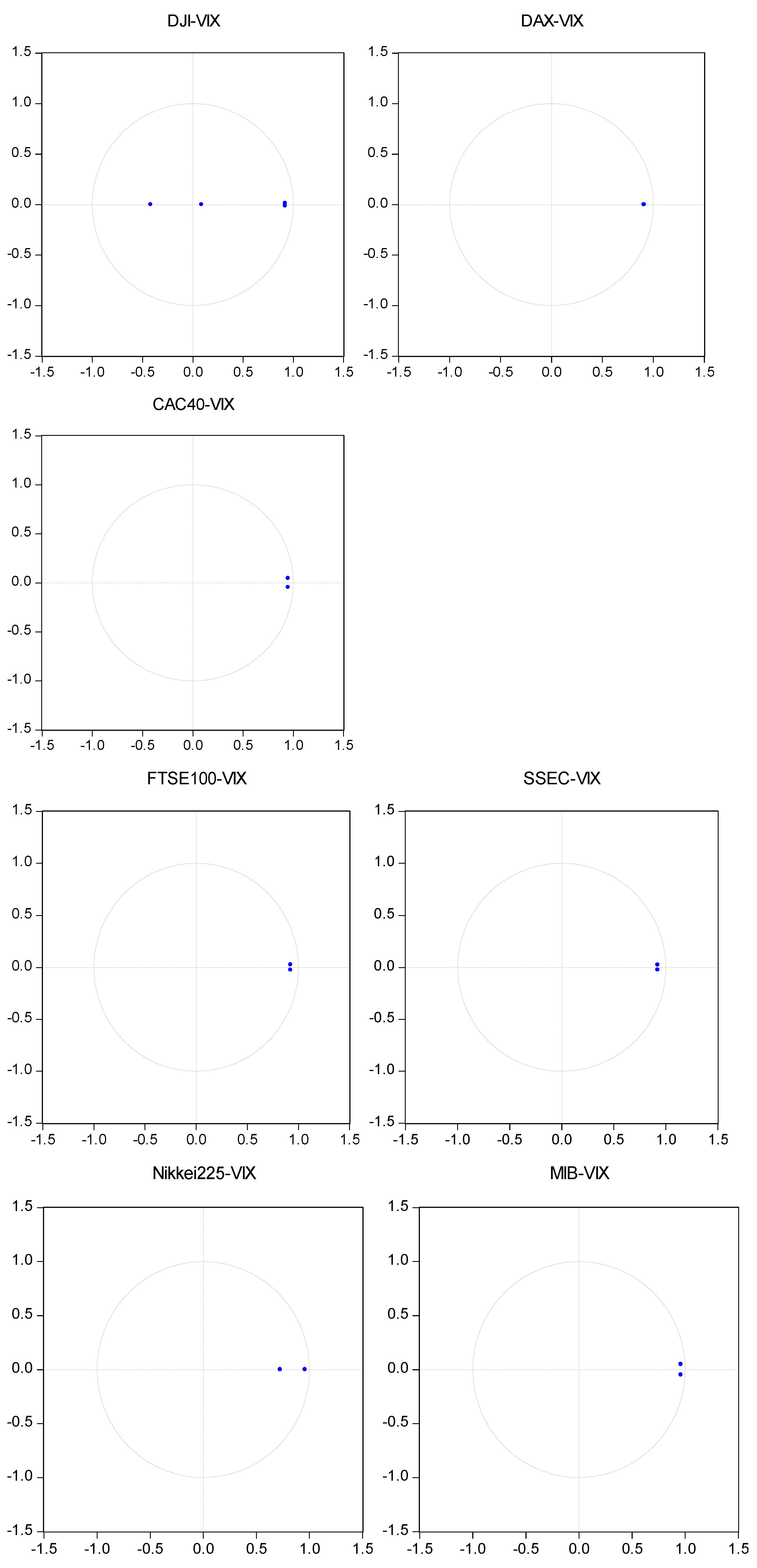

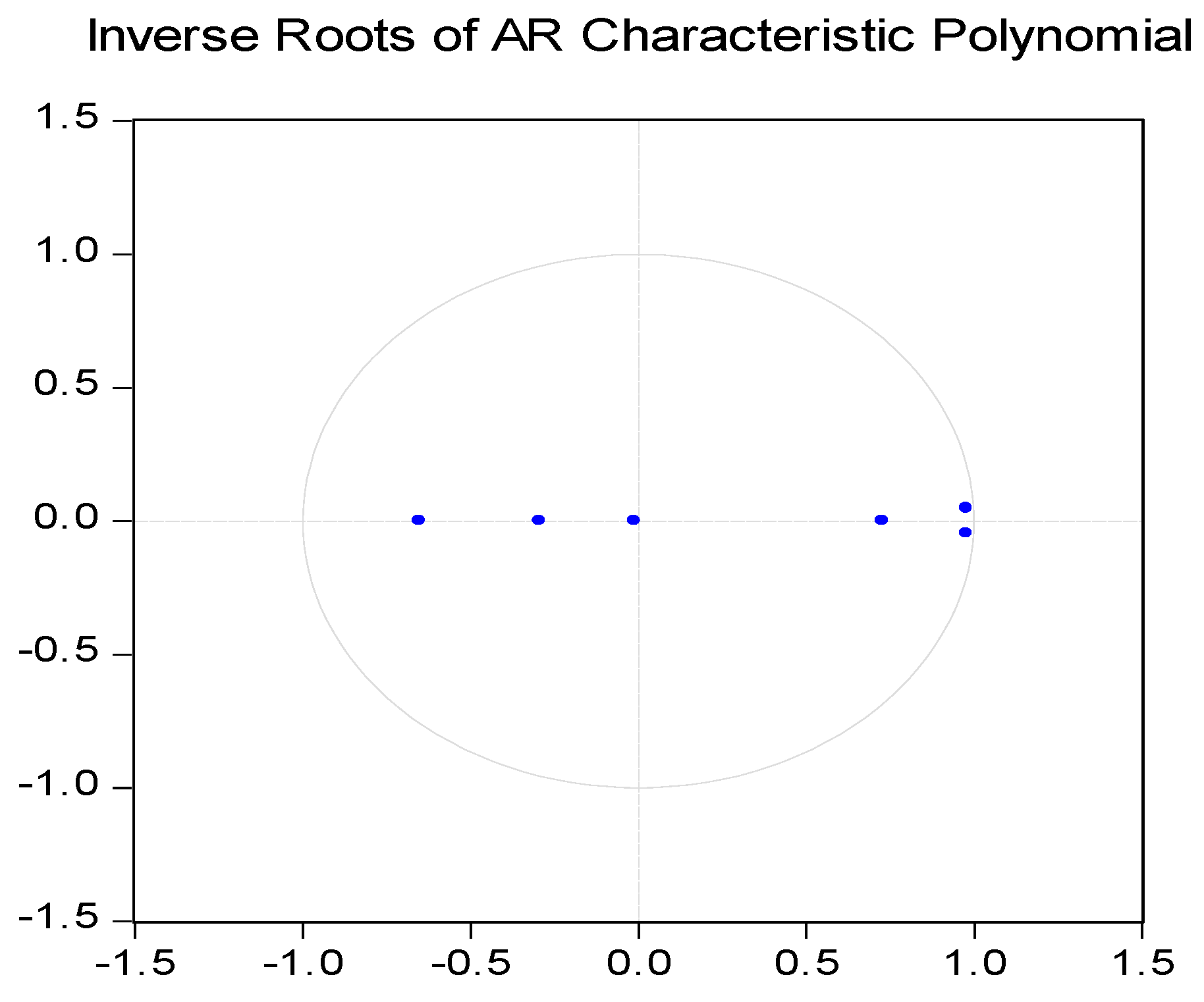

In this study, we had two objectives: (i) that of understanding the impact of COVID-19 cases on the VIX fear index during the period studied and (ii) that of determining the impact of the VIX on major stock indexes, specifically the DJIA, FTSE100, DAX, CAC40, FTSEMIB, SSEC, Nikkei225 and MID. To do this, we examined the co-integration relationships between variables and determined the effect levels using the FMOLS regression analysis.

One of the best measures of fear in the markets is the VIX. This is derived from the price of Standard and Poor (S&P 500) index options; it provides an objective measure of real-time sentiment and market stress (

Ritholtz 2020). A number of authors (

Gilboa and Schmeidler 1989;

Epstein and Schneider 2003) have developed models that suggest that the uncertainty of outcomes is related to risk and has a negative impact on market prices. They assumed that when faced with uncertainty, investors take a risk-averse approach and base their expectations on worst-case scenarios (maxmin expected utility).

Williams (

2009) and

Bird and Yeung (

2010) noted that both changes in the VIX and the level of VIX are a proxy for uncertainty and explain how the market responds to earnings information. They found evidence that at times when there is high uncertainty, the market sentiment plays a role in counteracting the resultant pessimism of that uncertainty.

Our results highlighted the co-integration between the VIX “fear” index and the COVID-19 cases. A 1% increase in the COVID-19 cases increased the “fear” index by 32.5%. Furthermore, we found co-integration between the VIX index and the major indexes, except for the CAC 40 and the MIB. Increases in the VIX index led to a fall in the major indexes. The largest effect was on the DAX (−23.26%) and the FTSE100 (−22.15%), while the lowest effect was on the SSEC (China) (−4.45%).

As noted by

Li (

2019), this is seen as an unusual trend in the stock market, as she highlighted that the VIX index typically trades inversely with other indexes and bad news. Moreover, she noted that this implies that something else or some noise was driving the markets.

Moreover, we determined that the COVID-19 cases had a larger impact on the VIX index than the COVID-19 deaths. The effect of the VIX index on the German and the British stock markets was larger than on the U.S. and the Chinese stock markets. This may have been due to the fact that the Federal Reserve (FED) in the United States can manage USD volume and apply policy. Regarding China, this may be explained by the fact that they had announced that the COVID-19 cases decreased before they peaked in other parts of the world. Furthermore, China has its regional market structure, which can be noted from other studies, such as that by

Özen and Tetik (

2019).

Our findings corroborate earlier findings by, for example,

Fernandes (

2020),

Yilmazkuday (

2020) and

Cheng (

2020). The former found that the British markets declined by more than 35%, while the U.S. stock market plummeted by over 25%. He noted that British stocks were affected by the COVID-19 cases in the USA and the VIX index because of its integration with the US economy. While the latter author highlighted that starting in March, the cases of COVID-19 were increasing rapidly in Europe and there were reports of community spreading and deaths in the United States. The S&P 500 had declined slightly, while the VIX index had risen to 33 from 14. Moreover,

Yilmazkuday (

2020), showed that a 1% increase in the U.S. cumulative daily COVID-19 cases resulted in around a 0.01% cumulative reduction in the S&P 500 Index after one day and around a 0.03% reduction after one month, with the largest observations found during March 2020.

On the other hand and different from our findings,

Albulescu (

2020a) found that the death ratio positively influenced the VIX index and that this influencing effect was stronger outside China.

Zeren and Hızarcı (

2020) found no co-integration with the FTSE MIB, CAC40 or DAX30.

Onali (

2020) argued that the COVID-19 crisis did not have an impact on the U.S. stock market returns between 8 and 9 April 2020, with the VIX negatively affecting the stock market returns. However, the main reason for this may be due to the use of data collected from different areas, such as in the case of

Onali (

2020) in which data was collected mainly from China, and to the different periods under observation.

The findings of the study clearly showed the impact of the uncertainty and fear in the market, which resulted from the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic outbreak and the daily new cases and deaths on the CBOE volatility index. Moreover, the study showed that there was a significant effect of the VIX index on the DJIA, DAX, FTSE100, SSEC and Nikkei225 indexes, thus showing the indirect effect of fear in the market. The findings are of special importance to portfolio and fund managers, as well as risk managers, underwriters and actuaries.

One must however understand that the findings of this study are limited to the period under study and to the markets that have been analysed. Therefore, although they can be somewhat generalisable to other similar or even smaller markets, further studies should be carried out on other markets and in different periods to determine whether the effects were similar or specific to the market in question. In addition, COVID-19 data was available 7 days a week, while the financial data reflected the working days of the week. However, we assumed that this limitation would not have much effect on our analysis since, in normal circumstances, other news is still available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Furthermore, we tried to eliminate the noise from spillover effects, such as pandemic fatigue and news on available vaccines and medicines, as much as possible by taking a period at an early stage of the outcome of the pandemic; as such, we assumed that there was no noise effect in our findings.

Moreover, above all, one must note that all models have various assumptions, which users such as risk managers, portfolio managers and policymakers need to be aware of; these findings, which are dependent on the model assumptions and the strength of other factors (considered herein as noise), might result in a distorted version of the social reality. However, models such as these are needed to build expectations and to understand the determinants of deviations from findings and results obtained, which help us develop forecasts and risk management decisions.