1. Introduction

European club football has been confronted with a major regulatory intervention, UEFA’s Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations (FFP). Today, after five distinct applications of the break-even requirement, which represents the cornerstone of this intervention, it is time for an assessment: How has the situation changed since FFP first impacted European top-division football? Additionally, how has the regulatory intervention presumably affected this development?

In sum, the most recent data show that European club football is characterized by quick financial recovery and further polarization. While pre-FFP European club football was on a trajectory of ever-deepening financial distress until 2011, the data show a continuous improvement since financial year (FY) 2012, the first reporting period entering into a break-even assessment. Of course, the mere comparison of the financial indicators pre- and post-FFP does not prove that FFP is the (or the main) cause behind the financial comeback of the European football industry. Nonetheless, this article suggests a plausible economic story as to why FFP has had a significant impact on creating a more financially stable industry

1.

The newest data also show that financial recovery went hand in hand with further polarization. Absolute revenue growth has been much stronger at the top of the football pyramid, thereby further entrenching the sportive dominance of the “big clubs”. However, the mere coincidence of FFP and further polarization does not imply that FFP is a (or the) cause for this development. This article discusses good reasons why polarization has not been aggravated by FFP. Clearly identifying the main drivers of polarization is of fundamental importance before embarking on a new regulatory exercise beyond the scope of FFP.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 gives a short overview of the financial situation of European club football pre-FFP.

Section 3 briefly explains the main pillars, the assessment periods, and the judicial process of FFP.

Section 4 is devoted to the economic analysis of FFP: Where exactly does the regulation change the incentives of decision-makers in the football industry?

Section 5 presents facts and figures about the financial situation of post-FFP European club football.

Section 6 is devoted to the analysis of the polarization between the top-tier clubs and the rest.

Section 7 provides some first reflections on the European “super league” project.

Section 8 concludes.

2. The Financial Distress of Pre-FFP European Club Football

UEFA publishes a yearly Benchmarking report

2 covering the financial situation of approximately 700 first division clubs in 55

3 member associations.

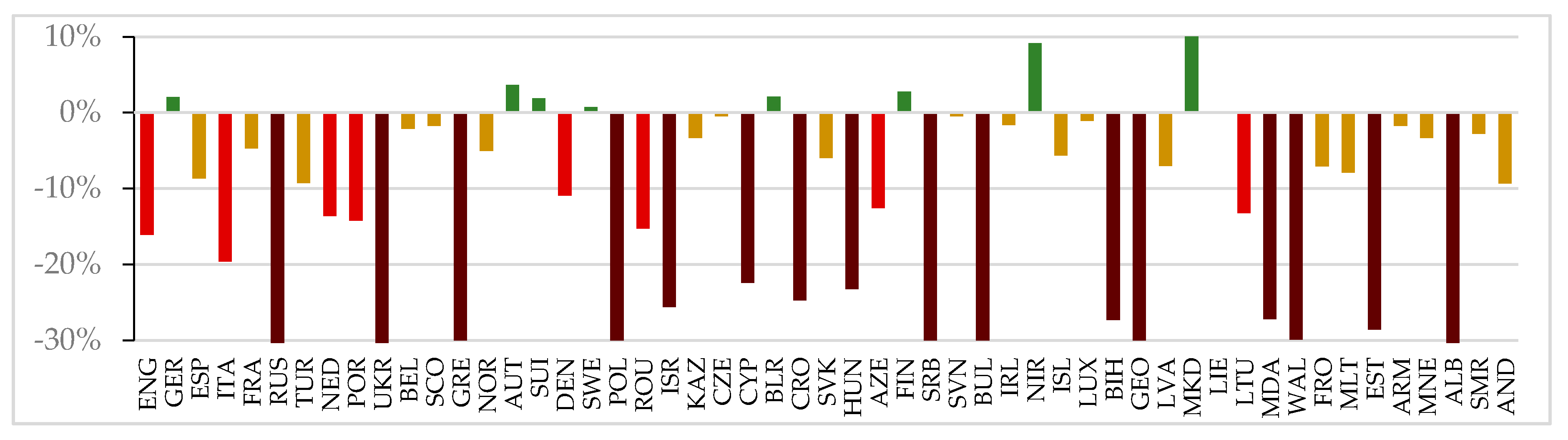

Figure 1 shows the aggregate “bottom line”, country by country, for the FY 2011. While football operating profits focus on the contribution from core football activities, the “bottom line” gives the performance of the clubs after including transfer activity, financing and divesting results, non-operating items, and tax. The country by country result in

Figure 1 sends a message of financial distress. The red columns show countries whose first division clubs had spent between €1.10 and €1.20 to gain €1.00 of revenue, whereas dark-red columns show countries where even more than €1.20 had been spent to gain €1.00 of revenue. The predominance of the red and dark-red colors indicates that, with rare exceptions, football was a largely unprofitable business in 2011.

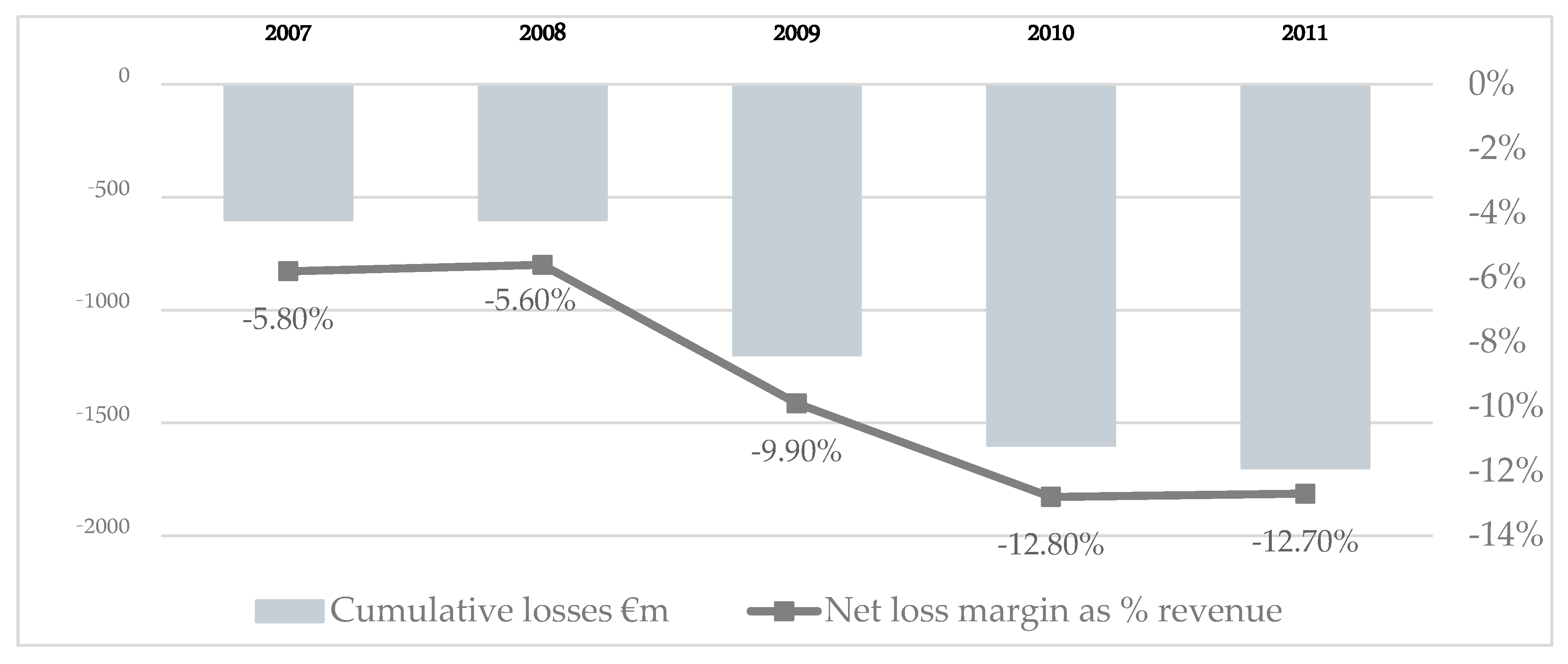

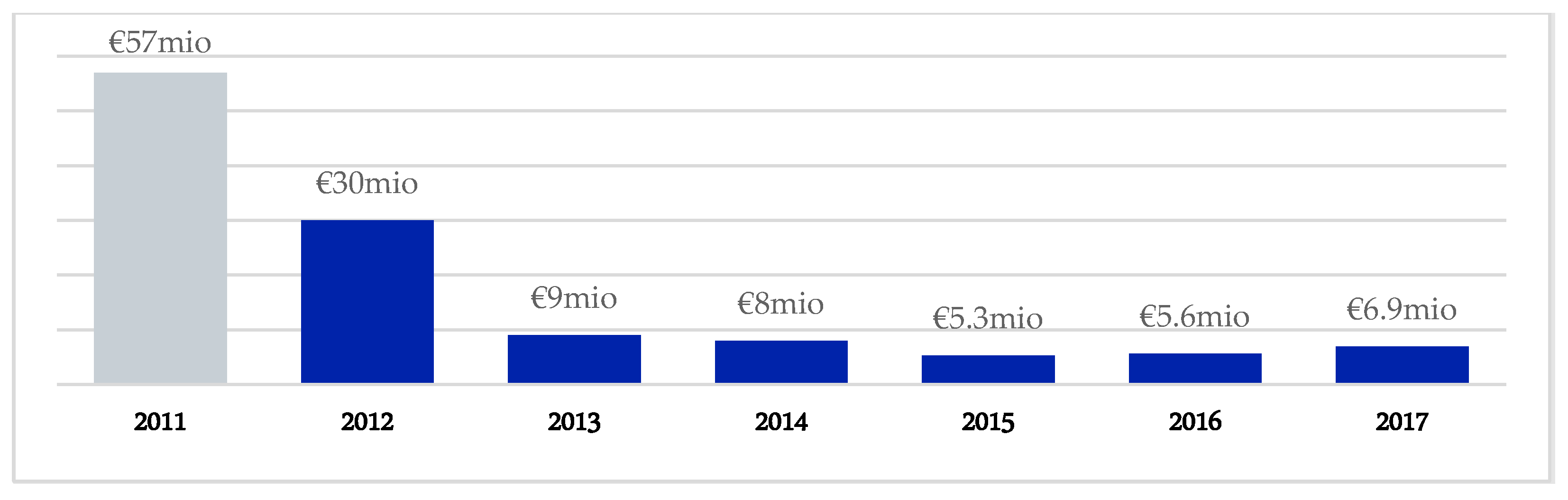

Figure 2 shows the development of the combined yearly net losses of all European top-division clubs from 2007 to 2011. The losses almost tripled from €0.6 billion to €1.7 billion.

The cause of increasing financial distress was that the clubs spent everything and even more than they could reasonably afford on players. While revenues had increased at an average rate of 5.6% per year

4, wages grew by 9.1% per year from 2007 to 2011.

5 The combined employee and net transfer costs to revenue ratio, which impacts bottom-line results, increased from 62% to 71%, meaning that the revenue increase between FY 2007 and FY 2011 had not been enough to cover the increase in combined employee and net transfer costs. As a consequence, the financial results of the clubs competing in European competitions were worsening year after year despite the fact that football as an industry was growing. The percentage of “financial zombies”, i.e., clubs with negative net equity, reached 38%.

6 Meanwhile, in 2011, 63% of all top-division clubs reported an operating loss and 55% a net loss.

7 The reported liabilities of the top-division clubs reached €18.5 billion in 2011, and auditors expressed “going concern” doubts (i.e., doubts whether the club could still trade normally in 12 months’ time) for one in every seven clubs.

8 As a reaction to this development, stakeholders in the football industry increasingly shared the perception that the long-term viability and sustainability of the entire system was being threatened by football clubs’ ever-deepening financial crisis. As clubs are strongly interconnected through their peculiar technology of producing a team output, the “championship race”

9, if some clubs go out of operation in mid-season, the credibility of the entire product of “championship” is severely harmed. Financial domino effects get triggered because bankrupt clubs cannot fulfill their obligations from transfer deals. Several factors, such as the high percentage of clubs with negative equity, the high level of overdue payables, the exit of “normal” investors

10 from the industry, etc., jointly indicated that the system was “overheating”

11.

Alerted by these developments, UEFA gathered internal and external experts to work on a regulation that would restabilize the football industry without entering into conflict with European Union competition law. The first version of the UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations was approved by the UEFA Executive Committee in September 2009.

3. The Two Main Pillars, the Assessment Periods, and the Judicial Process of FFP12

UEFA designed the new regulations as an enhancement of UEFA’s established “workhorse”, the club licensing system, which was introduced at the start of the 2004/2005 football season. In order to be admitted to UEFA’s club competitions, the Champions League and the Europa League, each club must fulfill a series of quality standards falling into five categories: Sporting, infrastructure, personnel, legal, and financial. With the introduction of the new FFP regulations, UEFA upgraded the financial standards by introducing two important new requirements, explained below. These requirements are monitored by a newly created body of independent experts, the Club Financial Control Body (CFCB).

The enhanced overdue payable rule, monitored from June 2011 onwards, is the first of the two new requirements. It demands that clubs playing in UEFA competitions must fulfill all their financial obligations towards other clubs, employees, and social or tax authorities punctually. While the established licensing system already assessed overdue payables, it only did so at one single date in the year, i.e., as of December 31. With the enhanced overdue payables rule, the CFCB monitors the fulfillment two more times per year, i.e., as of June 30 and September 30.

The break-even requirement, implemented in 2012 with the first assessment done during the 2013/2014 season, is the second and main pillar of FFP. The idea behind this requirement is that each club achieves a sustainable balance between its income and expenses in the football market. The income earned in the football market is called “relevant income” and consists mainly of gate receipts, broadcasting, sponsoring, advertising, and commercial income. The expenses in the football market are called “relevant expenses” and consist mainly of employee benefit expenses and player transfer amortization. Balancing these two factors means that clubs must be able to perform their core football activities without owner contributions and without incurring debt. At the same time, clubs can still invest and incur debt or expend owner contributions on infrastructure, youth development, and community activities. Because such investments are for the long-term benefit of the club, the corresponding expenses are not considered as “relevant” for the purpose of the break-even calculation.

Importantly, clubs must balance “relevant income” and “relevant expenses” not in one FY, but in monitoring periods usually consisting of three FYs.

Table 1 explains the concept of the applied “rolling three-year assessment”. The main consequence of the rolling three-year assessment is that every FY will be part of three break-even assessments until it drops out.

The first genuine break-even assessment took place in spring 2014. The CFCB had to wait until the clubs with a December year end closed their books for the FY 2013. In its first assessment, the CFCB assessed only the FYs 2012 and 2013 as an exception. In spring 2015, the CFCB then looked at the first complete monitoring period consisting of the FYs 2012, 2013, and 2014. The bottom box indicates the most recent assessment of the CFCB.

Due to the huge influence of sportive results on financial results—consider, for example, the financial impact of qualifying or not qualifying for the next round in the UEFA Champions League—the regulations give some flexibility to the clubs. More precisely, a break-even deficit of €5 million over three years is considered to be an “acceptable deviation”. Furthermore, the rules permit an additional deficit of up to €25 million over three years, provided that it is covered through the injection of equity by the owners. This gives some flexibility to redevelop mismanaged clubs into viable businesses

13.

Table 2 and

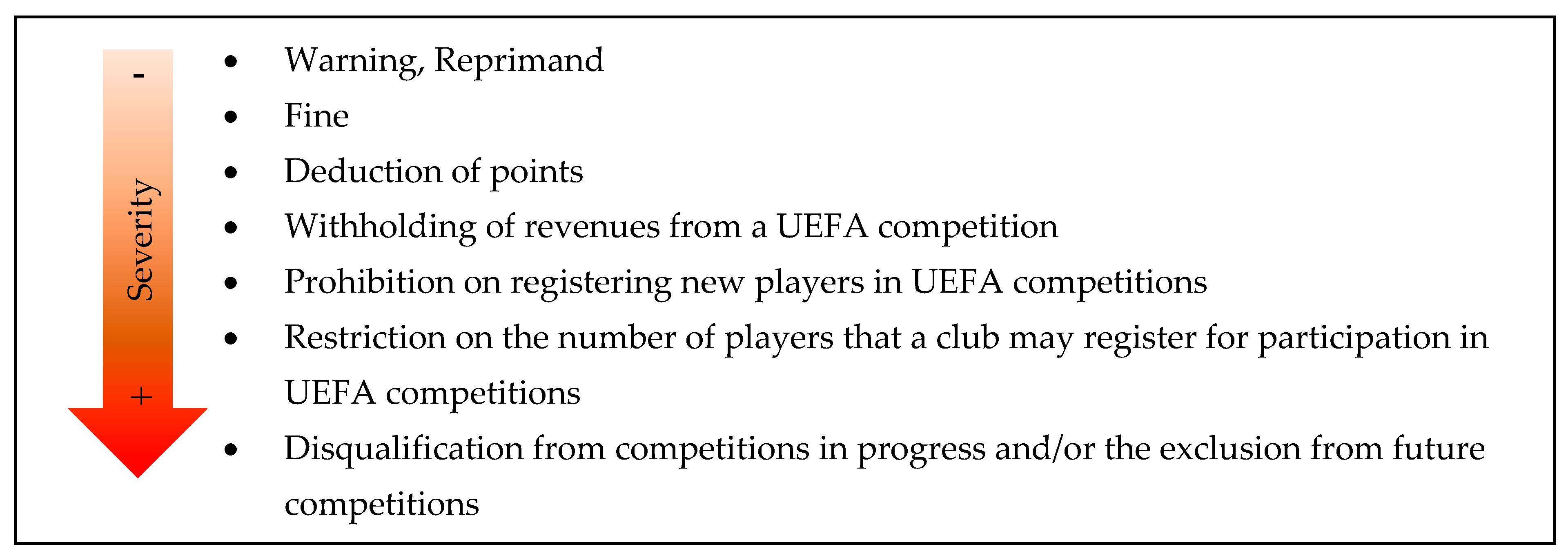

Figure 3 provide a brief overview of the judicial process of FFP. The CFCB comprises two chambers. The investigatory chamber conducts the investigation, determines the facts, and gathers all relevant evidence. It decides on every case, taking one of the following options:

Dismiss the case;

Impose minor disciplinary measures;

Conclude a settlement agreement;

Refer the case to the second chamber, the adjudicatory chamber.

The adjudicatory chamber takes a final decision on the case, which is either a dismissal or the instruction of disciplinary measures. As

Figure 3 shows, the disciplinary measures of the adjudicatory chamber reach from a warning to the exclusion from competitions and withdrawal of titles and awards. Clubs can appeal the decisions of the adjudicatory chamber before the Court of Arbitration of Sport in Lausanne (CAS).

The experience of the last years clearly shows that the most important instrument in the daily practice of the CFCB is the settlement agreements concluded by the investigatory chamber with individual clubs. A significant number of clubs—28 until today, among them prominent ones, such as Paris Saint-Germain FC, Manchester City FC, Inter Milan, AS Monaco, AS Roma, FC Zenit, or FC Porto—entered into settlement agreements.

Instead of going through a lengthy judicial procedure, clubs with the clear potential to come back into compliance rather quickly sign settlement agreements voluntarily with the investigatory chamber. These agreements contain a detailed plan with annual and aggregate break-even targets that have to be reached and a set of “provisions” that, from an economic point of view, can be seen as sanctions and restrictions. For example, there have been very high (unconditional and conditional) withholdings of prize money, up to €60 million, and also strict limitations of player registration activities.

UEFA publishes on its website summaries of all settlement agreements and of all the decisions of the adjudicatory chamber

14.

4. The Economic Analysis of FFP15

Football championships are examples of a certain form of economic competition, which is known as a contest in the literature. Research on contests shows that under certain circumstances, a phenomenon of overinvestment emerges.

16 While this “arms race” or “rat race” effect

17 explains why clubs may dissipate some resources in their attempt to achieve sporting success, it does not suffice to explain the extreme dissipation of resources in football, which transformed many clubs into “financial zombies” (i.e., a situation where the value of their liabilities exceeds the value of their assets). In other words, the concept of a “rat race” seems too weak to characterize an industry in which such a substantial part of the participants was technically bankrupt. Therefore, in this context, the concept of a “zombie race” seems more appropriate.

Obviously, a “zombie race” requires that the “normal” threat of dissolution of the club in case of insolvency is not functioning as a hard constraint. This leads to the second element of the story, i.e., to the soft budget constraints (SBCs) of many football clubs before the regulation.

18 Football club managers could rationally expect that in case of a deficit, some form of “supporting organization”, either the state or a private benefactor

19, would step in to relieve the club from the pressure to “cover its expenditures out of its initial endowment and revenue” (

Kornai et al. 2003, p. 4).

What is wrong with SBCs, though? Normally, economists would immediately discuss the differences between burning public or private money in football. However, this diverts from the main problem of bailouts in this specific context: They distort the incentives of decision-makers in football clubs.

4.1. Runaway Demand for Talent and the Emergence of a “Salary Bubble”20

If a club has a perfect SBC, the own price–elasticity of demand for player talent becomes zero, meaning that the demand for talent is not determined by the price but rather by other variables (

Kornai 1986, p. 9). It seems rational to assume that winning is desirable for club decision-makers and that talent contributes to winning. If the supply of talent is not sufficiently elastic, the direct consequence of the SBC is the formation of excess demand for player talent.

Frank and Bernanke (

2004) explain why the supply of talent is inelastic by definition: “Indeed, the most important input of all—highly talented players—is in extremely limited supply.

This is because the very definition of talented player is inescapably relative—simply put, such a player is one who is better than most others” (

Frank and Bernanke 2004, p. 113). Thus, talent, understood as the capacity of a few players to be better than most others, is extremely scarce and its price gets bid through the roof if enough clubs have SBCs and a very low price–elasticity of demand for talent as a consequence. The more clubs operate with SBCs, the more football becomes a “talent shortage economy”, resulting in a “salary bubble”

21, where the wages and transfer fees of the few talented players reach levels that are unsustainable without systematic money injections.

4.2. Managerial Moral Hazard: Too Much Risk and Too Little Care22

Another consequence of the declining price–responsiveness of football clubs operating with SBCs is risk escalation. The emergence of managerial moral hazard behavior in environments with SBCs is a standard result that has been studied in different contexts. A prominent example is the “too big to fail” problem in the financial sector

23, in which managers are inclined to take excessive risks because they can expect to be bailed out ex post.

Franck and Lang (

2014) analyzed money injections in football clubs based on a formal model. As soon as the option to be bailed out with a certain probability exists, club decision-makers are induced to make riskier investments.

Risk escalation is only one aspect of managerial moral hazard. In absence of what

Kornai (

1986, p. 12) called “‘dead-serious’ considerations of revenues and ultimately of supply”, decision-makers do not invest enough of their own time and energy to end bad projects and develop good projects. Therefore, money “coming like manna” (

Kornai 1986, p. 12) triggers waste and profuseness.

4.3. Managerial Rent-Seeking24

Managerial rent-seeking gives weak incentives to innovate and to develop the business, as

Kornai (

1986) explains: “Allocative efficiency cannot be achieved when input-output combinations do not adjust to price-signals. Within the firm there is no sufficiently strong stimulus to maximum efforts; weaker performance is tolerated. The attention of the firm’s leaders is distracted from the shop floor and from the market to the offices of the bureaucracy where they may apply for help in case of financial trouble” (

Kornai 1986, p. 10).

To the extent that rent-seeking behavior is systematically rewarded in SBC organizations, their managers invest less effort in developing competitive advantages by “improving quality, cutting costs, introducing new products or new processes” (

Kornai 1986, p. 10). If productive efforts can easily be substituted by asking the “sugar daddy” to compensate for unfavorable developments, SBC organizations will be less innovative and their managers less entrepreneurial in a dynamic perspective

25.

4.4. Crowding Out of Incentives for “Good Management”26

Clubs operating with hard budget constraints find themselves victims of the “salary bubble” produced by the clubs with SBCs. Maintaining their old level of playing strength by keeping their share of “star players” would require higher expenditure in the player market. At first sight, this could generate an additional incentive to further increase efficiency through “better management” in order to remain competitive on the pitch. However, what if the margin to further increase efficiency through “better management” becomes too small compared to the magnitude of the money injections of benefactors at their competitors?

It seems that these clubs will have no choice but to accept sportive decline or to change sides and start gambling on success and invest more aggressively. If we consider that sportive decline generates disutility both for club decision-makers and fans, it seems plausible that the SBCs of some clubs should intensify the incentives of other clubs to overspend.

Thus, “unlimited” money injections have a tendency to crowd out business models based on “good management”. More and more clubs tend to take more risk and chronically expend more than their earnings, hoping to be rescued by external money injections year after year if the gamble goes wrong. One might argue that this state of affairs had already been reached in the FY 2011, given the numbers presented in

Section 2.

4.5. The Role of FFP

Against this background, FFP is an instrument to move from a state of affairs with SBCs to a state of affairs with harder budget constraints

27. The message sent to football managers by the cornerstone of FFP, the break-even requirement, is that they should no more “hope for a bailout” when the payroll expenditures drive relevant expenses to a level that exceeds relevant income by more than the “acceptable deviation”. Clubs will be sanctioned and, in extreme cases, not receive a license to play if they do not break even in the football market. Thus, the existence of benefactors that would be willing to donate additional money to cover excessive salary and transfer payments becomes irrelevant.

In theory, the FFP regulation should therefore mitigate the inefficiencies resulting from SBCs and reduce the systemic risk of a severe financial crisis in the football industry. Clubs that break even in the football market and pay their bills punctually are sustainable and do not produce any kind of negative externalities, which might bring other clubs in trouble.

5. The Financial Situation of Post-FFP European Club Football

“Will football revenues drop substantially post-FFP?” This “prosperity concern” was a major criticism when FFP was introduced

28. “Will post-FFP football enter into a downward development if the money injections of benefactors no longer freely flow into the clubs?” The fear was that smaller money injections would lead to lower quality on the pitch, less attractive games, lower consumer interest, and lower sponsor interest, therefore driving clubs into a downward spiral.

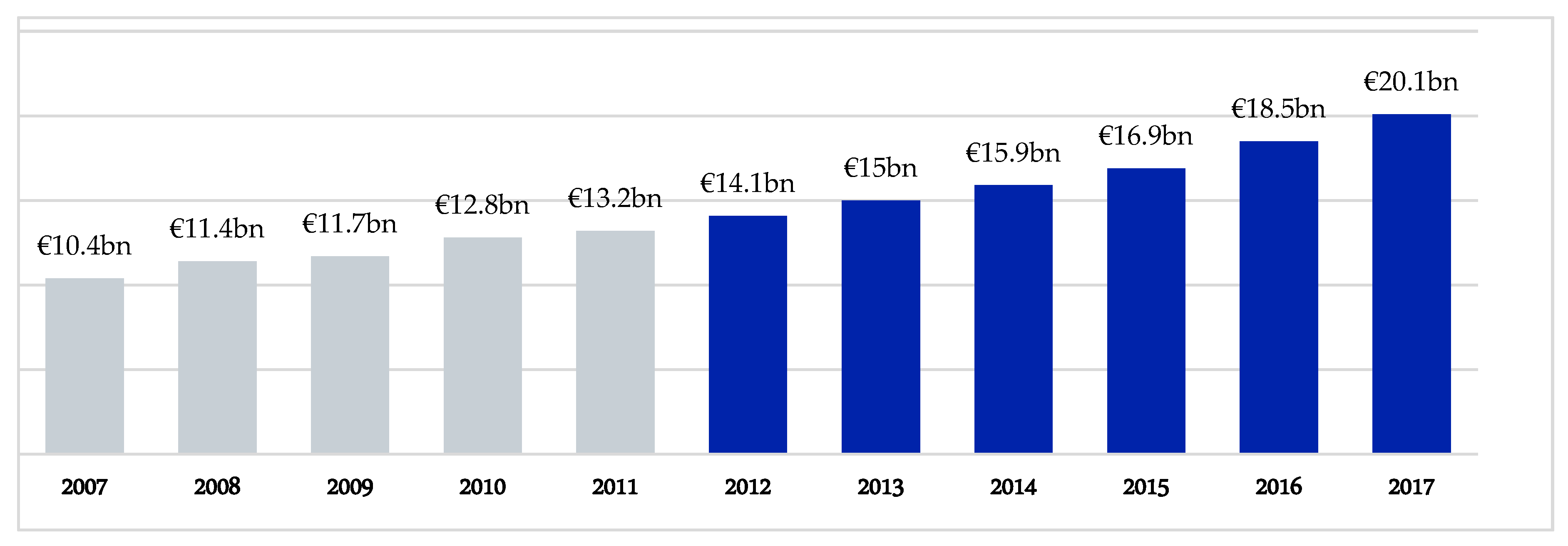

However,

Figure 4 shows that the post-FFP reality contrasted these criticisms. The post-FFP compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of revenues increased to an impressive 7.2%. There are at least two good reasons for this development.

5.1. First Reason29

Critics exaggerated the “prosperity concern” because they failed to precisely study the new regulations. In that case, they would have easily found out that the payments of owners made for the absorption of losses in the past would not entirely disappear post-FFP. A substantial part of them would simply become a fair market value transaction and continue to flow into football.

As an example, consider the German chemicals corporation Bayer AG, which is the 100% owner of the Bayer 04 Leverkusen football club. The question to be answered under FFP is how much would the Bayer AG have to invest in public relations (PR) activities per year in order to achieve a similar level of brand awareness as that produced by Bayer Leverkusen? The Bayer AG can continue to absorb losses of this level at its subsidiary club under FFP by simply concluding a sponsorship agreement and paying the fair market value sponsorship fee.

The major difference to the ex-post absorption of losses common in the past, is that such sponsorship deals have to be concluded ex ante. Because managers of football clubs have complete knowledge of the sponsorship revenues, which are a component of relevant income, they have no reason to develop any kind of SBC expectations with all the associated incentive problems. All the former money injections of club owners that constitute a fair market value compensation for transacted goods or services will therefore continue to flow into football, for example, by being transformed into sponsorships. However, they enter the system without creating SBCs.

Only payments that would constitute contributions above the fair market value of goods or services exchanged between the club and the owner will not be counted as relevant income under FFP. If, for example, the Bayer AG would pay more to its subsidiary club in a sponsoring agreement than a comparable amount of exposure/image transfer costs in the free market, this “sponsoring in excess of fair market value” would not count as relevant income.

Under FFP, the club can still take this money and spend it on infrastructure, youth development, or community activities. However, the club cannot use this money to cover relevant expenses, that is, for player salaries and transfer amortizations. For owners with a longer-term perspective, investments in infrastructure, youth development, etc. outside the direct payroll may still make good sense. These owners will not reduce their money injections to a “fair market value” level, but they will simply not use the “excess” to directly inflate payrolls in the club.

Thus, it could be expected that a substantial part of the owner injections seen in the past would still flow into football as fair market value transactions, and another substantial part would continue to flow into football as investment in infrastructure, youth development, and community projects outside the fair market value adjustment.

5.2. Second Reason

New revenue sources would emerge in a regime with different managerial incentives. A lot more money would be generated in the football market if managers facing hard budget constraints stopped playing moral-hazard and rent-seeking games and started doing “a good job”, concentrating on productive efforts, taking adequate risks, and developing the business

30. Taking all these reasons together, concerns that FFP would lead to decreasing revenues and to a downward spiral seemed unfounded.

Until 2011, growing revenues went hand in hand with deteriorating club finances. After the introduction of FFP, this is no longer the case.

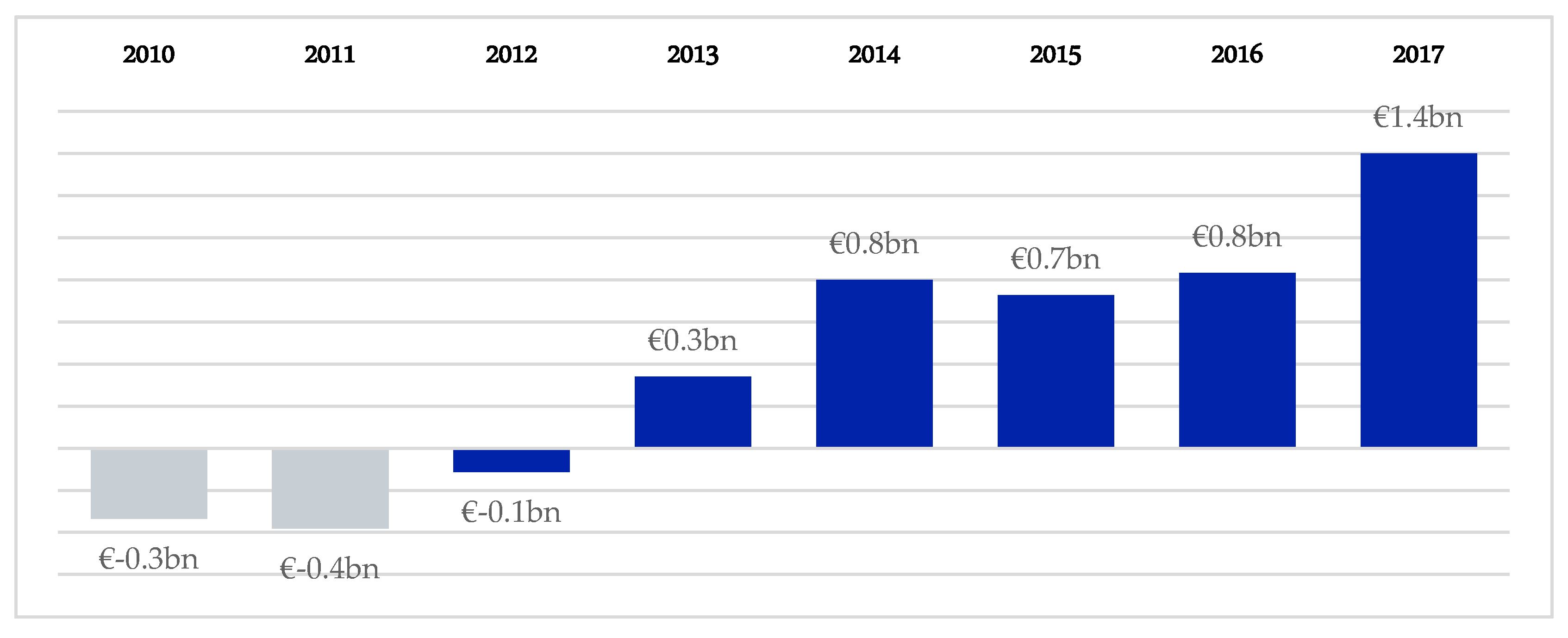

Figure 5 shows that the post-FFP overdue payables decreased by more than 90% compared to pre-FFP.

Figure 6 shows the aggregate operating results for the European top division clubs. For the first time, clubs reported decreasing operating losses in 2012, the first year entering into a break-even assessment. Since 2013, top-division clubs have reported positive operating profits: They generated €2.9 billion in operating profits over the 2015–2017 period.

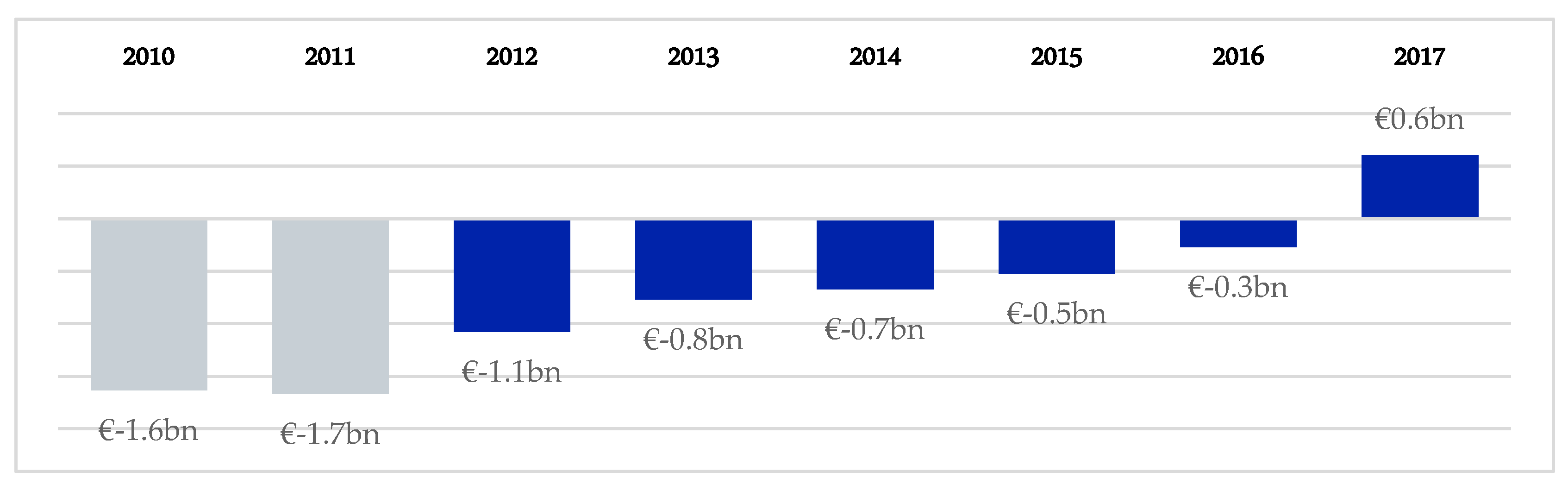

Figure 7 shows the aggregated net results after including transfer activity, financing, and investment/divestment and taxes. Since the FY 2012, a clear positive development in the aggregated net results is apparent. For the first time in 2017, European club football even reported an aggregate bottom line profit. This is remarkable when considering that European football clubs are generally not seen as “normal” profit-maximizing firms. Even after fixing the problem of SBCs through regulation, football remains a contest between win-maximizing participants. FFP does not force participants “to make profit”, but only to break even in the football market by and large (with an acceptable deficit of somewhere between €5 and €30 million in 3 years, as long as the owner covers the difference through equity injections).

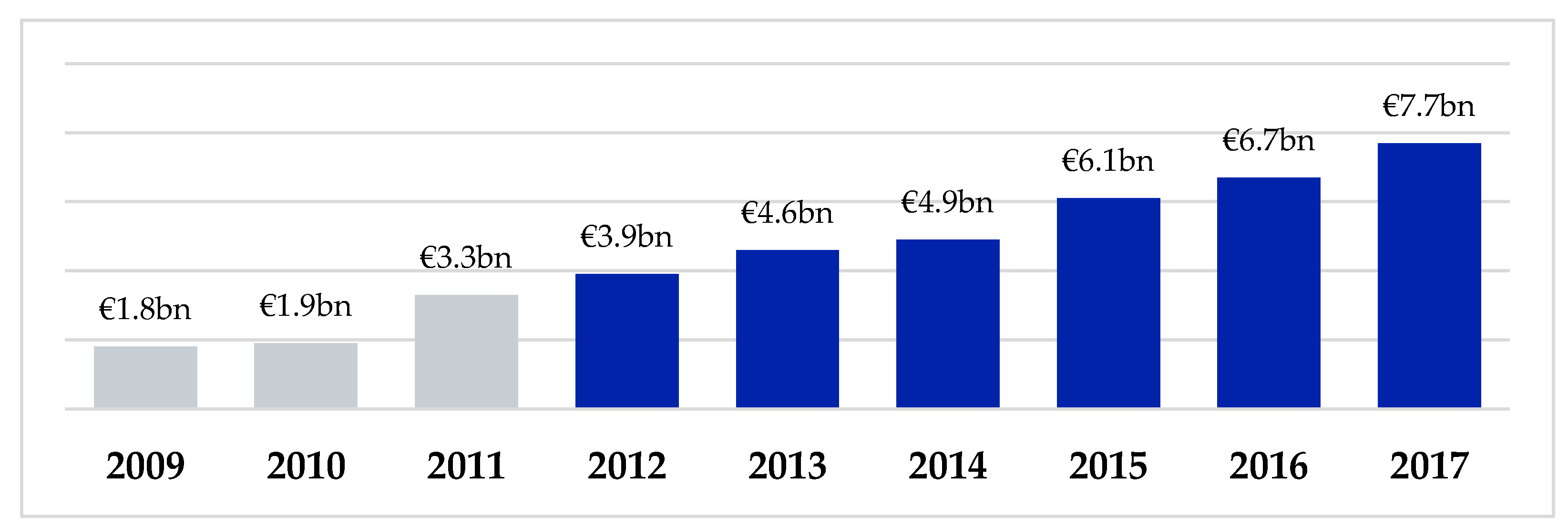

Figure 8 shows the evolution of top-division club net equity (assets less liabilities). A significant improvement of the balance sheets has taken place, meaning that the “zombie race” problem disappears. Net equity has more than tripled since the rules were approved in 2009.

The numbers presented in this section undeniably show the financial comeback of the European football industry.

6. Polarization: A Challenge Not Directly Addressed by FFP

The Deloitte Football Money League, a report produced annually by the accountancy firm Deloitte, ranks European football clubs based on their revenues

31.

Table 3 shows that in Season 2016/2017, the top 10 clubs in this ranking had revenues of €535 million on average, while the clubs ranked 11–20 had revenues of €255 million on average. In the Season 2011/2012, the revenues were €334 million for the top 10 and €150 million for the 11–20, whereas in the Season 2006/2007, the revenues were €251 million for the top 10 and €122 million for the 11–20.

The last column exhibits the difference between the top 10 and the 11–20 clubs in the different seasons. The difference was €129 million in 2006/2007 and grew to €184 million in 2011/2012 and to a €280 million in 2016/2017. These absolute numbers

32 show that in the last five years, the clubs at the top have literally “pulled away” away from the rest.

At the same time, these “big clubs” seem to become more dominant on the pitch. In

Table 4, the top panel shows that the Bundesliga, the Serie A, and the French League 1 are dominated by one club, whereas the bottom panel shows that the final stages of the UEFA Champions League (UCL) look more and more like a closed and exclusive competition, because the number of different semifinalists decreased.

In the period covering the Seasons 1997/1998 to 2003/2004, 16 different clubs reached the UCL semifinals. In the period covering the Seasons 2004/2005 to 2010/2011, the number of clubs in UCL semifinals decreased to 13. Finally, in the period covering the Seasons 2011/2012 to 2017/2018, only 11 different clubs entered the UCL semifinals.

In sum, the numbers suggest that a process of polarization has taken place:

An important question is whether there is a causal relationship between FFP and polarization. Indeed, FFP has been at times attacked by pointing to the fact that it has not worked as an effective remedy against polarization. However, it is important to note that FFP was not designed as a remedy against polarization. For example, if Real Madrid and FC Basel follow the rules and balance relevant income and expenses, the consequence is not that they become equal competitors on the pitch. If “big clubs” and “small clubs” live within their own means, in line with the break-even requirement, this does not imply that they rely on equal means.

FFP has also been attacked with the argument that it contributed to further polarization

33 because even the richest “sugar daddies” have to compete based on payrolls largely financed through income generated in the football market. As a consequence, they will no longer be able to challenge the “bigger clubs” by spending more money on players. The idea that FFP might therefore entrench the dominance of already “big clubs” seems plausible at first sight. However, the key question is whether a mechanism exists that systematically allocates payroll injections according to a pattern that makes “small clubs” relatively more competitive

34.

First of all, FPP only caps “inflated” owner payments. A sponsoring agreement, where the owners pay a fair market price in exchange for the exposure/image transfer generated by the team for their other businesses, is in line with the regulations. In order to be affected by FFP, the owners must be willing to inject more money into payrolls than the publicity and image transfer generated through the success of their teams. In other words: Those owners that will be restrained by FFP in their “usual” spending behavior are “pure” success-seekers. “Pure” success-seekers by definition will try to spend their money where winning probabilities are the highest. As a consequence, they will systematically search for the clubs with the largest market potential available on the market.

It is widely accepted that the behavior of European football clubs is best described as “win maximization” subject to a budget constraint. Which is the likely result of a matching process between success-seeking benefactors and win-maximizing clubs? This article suggests that, in equilibrium, “money comes to money” because success-seeking benefactors look for the clubs with the largest market potential available and win-maximizing clubs by definition prefer the largest payroll injection. If unregulated, this simultaneous competition for money injections and market potential should converge to a state where the benefactors with the deepest pockets get allocated to the clubs with the largest market potential (the “favorites”), making them even more dominant.

One could argue that by preventing “pure” success-seekers from inflating payrolls, FFP is also preventing the deepest pockets from supporting clubs from the largest markets. Thus, FFP actually slows down the speed of polarization.

However, what else may be driving polarization? Polarization is likely the result of the concurrence of several factors, such as digital technologies, globalization, and the “winner-take-most” dynamic in many entertainment markets. The basic mechanism has been explained in the seminal paper of

Rosen (

1981).

New technology dramatically enlarges the market for producers of football entertainment. While before the advent of TV, the potential number of consumers of a football game was limited by the size of the stadium and the local population, later, with national TV rights, the national market became the crucial limitation. Nowadays, with new technologies, such as high-speed internet and mobile digital platforms, potentially the entire world is the relevant market.

If consumers prefer higher to lower quality, the likely outcome is a sort of “superstar” development: The attention of consumers with a preference for quality migrates to the producers of top content. During the first phase of market enlargement, from local stadium to national TV markets, national “top clubs” emerge. These producers will attract more attention. To the extent that revenues are attached to attention, these producers can further increase their quality. The larger the national TV market is, the more these “top clubs” can increase their quality and revenues. They are in a favorable position to exploit the next phase of market enlargement, the development of global entertainment demand through new technologies. Quality-sensitive consumers from the all over the world will be attracted by the “best product” offered by these “top clubs” that were able to grow and develop in their “big national markets” in the past. As a consequence, they will attract even more quality-sensitive consumers and further increase their revenues. In the end, these winners will take most of the market. As a consequence, attention and correlated revenues concentrate at the top of the producer hierarchy.

Adler (

1985) has added to this theory the insight that new fans tend to attach to the clubs that already have many fans. A person interested in football derives utility not only from watching games, but also from discussing and interacting with other likeminded people. The more popular the club in question is, the lower the searching costs to find fellow fans will consequently be.

To sum up, the very skewed distribution of attention, correlated earnings, and success are the result of the following two factors:

First, new technology has dramatically enlarged the market for producers and quality-sensitive worldwide demand has migrated to the top of the producer hierarchy (i.e., the Rosen effect).

Second, once a club has a large “installed base” of fans, “popularity effects” kick in. New fans patronize the superstar club because of the network externalities emerging from a large fan base (i.e., the Adler effect).

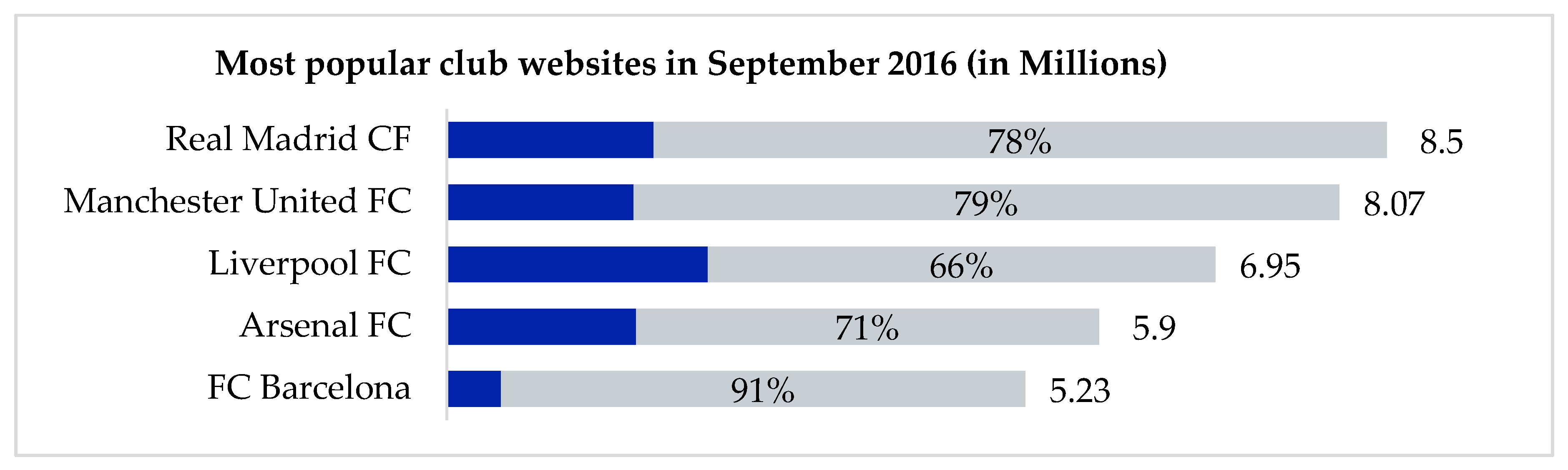

In order to capture their global profile, UEFA measured the traffic on clubs’ websites in September 2016.

Figure 9 shows that 5 European club websites had more than 5 million visitors. The large portion of foreign online visitors (in grey) clearly suggests that these clubs are “global brands” reaching out to a worldwide audience, just as the Rosen–Adler superstar theory would predict. The extreme case is FC Barcelona: 91% of the online traffic on the FC Barcelona website originates from outside Spain.

Finally, an obvious consequence of polarization is the proliferation of “unequal pairings”, i.e., matches between the “big clubs” and the rest. The “big clubs” literally dominate the other teams in domestic league games and the same happens in the group phase of the Champions League, where the “big clubs” encounter teams from much smaller domestic leagues. As a consequence, one may ask if in the future there will be sufficient suspense left in the system to attract fans, sponsors, or commercial partners. Should the preservation of sufficient suspense be addressed by changing the format of the competition? Is the European “super league” a possible solution?

7. Some Reflections on the Incentives of the “Big Clubs” in the European “Super League” Project

Discussions about the creation of a closed European league of “big clubs” recently gained new momentum

35. A look at the current top-level format of the competition is helpful to clarify the incentives of the “big clubs”. Two main characteristics stand out:

Overlapping competitions, i.e., the “big clubs” play in the domestic leagues and in the Champions League simultaneously;

Openness, i.e., access to the Champions League is mainly based on sportive qualification in the domestic leagues.

The overlapping competitions at the top of the football pyramid are an anomaly when compared to all other levels of the pyramid. Second division clubs, third division clubs, etc. normally only play in their respective divisions of the domestic competitions, if we abstract from cup games. A first approach to dealing with the problem of “unequal pairings” would be to abolish this anomaly of overlapping competitions and preserve openness by creating a European “super league” with promotion and relegation on top of the domestic leagues.

This “super league”

36 would replace the current European competitions, and its participants would no longer play and earn revenues in domestic competitions simultaneously. This model would be much more effective with respect to the avoidance of “unequal pairings” than the current format

37. Teams that dominate domestically get promoted to the presumably stronger European level and teams that underperform at the European level “go back” to their domestic competitions. Of course, many details of this open “super league” model would have to be worked out properly before putting it into practice. In particular, the heterogeneity of domestic competitions is difficult to tackle in this context.

However, comparable problems have been solved in the past at other levels. For example, when the German Bundesliga was created in 1963, it was introduced as the “German super league” and the new “top” of the domestic football pyramid, which previously consisted of five different regional leagues (“Oberligen”). Why should the project of an open European “super league” be less successful today than the project of an open German “super league” was in 1963? If the Rosen–Adler superstar theory holds, games between strong teams attract quality-sensitive consumers. The current European competitions already show the existence of a supranational market for football entertainment. Moreover, travel time between the big European cities has become shorter than, for example, between provincial towns in Germany, thanks to modern transportation technologies. Why then do we not see any significant attempt to embark on projects that would further develop and implement this solution of an open European “super league” with promotion and relegation?

An important reason is presumably that the “big clubs” are not interested in this model. Their strategy seems to aim in the opposite direction, namely, to preserve overlapping competitions, and, at the same time, to put pressure on UEFA in order to increasingly “close” the final stages of the Champions League:

The number of slots in the group phase of the Champions League has been increased to currently four for each of the “big” domestic leagues. Since the “big clubs” all come from the “big” domestic leagues, they have almost “safe access” to the Champions League. Even in less successful domestic seasons, their much more expensive squads will manage to finish on one of the first four ranks of the domestic league table;

The group phase then systematically sorts out the “underdogs”, which might win single games but cannot survive in a series of games against the star squads of the “big clubs”;

Finally, seeding ensures that the “big clubs” do not meet and sort out each-other in the first stages of the competition;

Thus, the final and most lucrative stages of the Champions League look more and more like a closed competition of the “big clubs”.

Recently, the media have spread the idea that the “big clubs” intend to leave domestic competitions entirely to play only in a new hermetic self-operated European “super league”. However, there is a difference between the threat, which the “big clubs” have systematically produced in the past in order to improve their own bargaining position in negotiations with UEFA, and the strategy they have pursued in reality. The threat to leave the football pyramid and the current system is a proven instrument to pressure UEFA into giving ever larger pieces of the Champions League “pie” to the “big clubs”. By definition, the threat to leave “the current system” can only be the creation of a hermetic, self-operated league, because there is no other football pyramid, which the “big clubs” could target as their new “home”. Therefore, the “big clubs” started to invest resources in what can be called the “perpetual hermetic super league project”. This project goes back to at least the year 1998 and gained additional momentum in 2000 with the G14 initiative

38.

A closer look at the incentives of the “big clubs” suggests that the credibility of their threat is rather moderate for a number of reasons.

First, if they would make real their threat and break away, they would automatically lose the advantages stemming from the current system of overlapping competitions, e.g.,:

Multiple sources of income: The current modus of overlapping competitions at the national and the European level allows the “big clubs” to earn money in their domestic competitions and in the European competitions simultaneously. The more developed and prosperous the respective domestic competitions are, the higher the incentives of “big clubs” to preserve the link and play domestically.

Multiple chances to lift trophies: A detailed inspection of a letter written by clubs such as Real Madrid, Manchester United or Bayern Munich is helpful to see the point made in this section. Half of the space on the left side of the letter typically lists the trophies these clubs have won in the past. For such “big clubs”, years with only one “minor” trophy (for example, a domestic cup title) are considered as failures. Overlapping competitions create multiple chances to lift trophies.

Second, if the “big clubs” exited the current system, they would exit the football pyramid and lose the advantages related to this pyramid, e.g.,:

Multiple sources of suspense: By preserving the link to the pyramid, the “big clubs” make sure that fan interest is fueled by several open questions that generate suspense. Instead of a single potentially open question such as “which team will win the closed league?”, many questions are open in a multilevel contest format, such as “which team will win the championship race in every league of the system? Which team will get promoted to the next level? Which team will be able to avoid relegation? Which team will be demoted? Which team will be able to qualify for the UCL from a domestic league? Which team will qualify for the Europa League?”, etc.

Multiple sources of surprise: Entertainment demand is not only driven by suspense, but also by surprise

39. The rise and unexpected performance of underdogs fascinates people and attracts new fans to the game. The current system, the football pyramid, is open to “success stories”. Consider the rise of RB Leipzig from the bottom to the top of the German football leagues within only seven seasons, or FC Leicester City winning the Premier League in 2016. Compared to that, the model of a closed, balanced “big club”-league leaves little room for surprise because “underdogs” are nonexistent by definition.

Third, “hermetic leagues” function according to a different logic, which would require a complete redesign of the governance and incentives systems. To make a closed league attractive, the “big clubs” would need to guarantee “openness of outcome” as long as possible in every season through revenue redistribution, salary caps, drafts systems, etc. Is it realistic to assume that the win-maximizing “big clubs” of today, which voluntarily engage in genuine arms races, will convert to an “egalitarian regime”, where they share their resources and voluntarily respect “arms-control” regulations? Redesigning the governance and incentives systems would generate very substantial transaction costs, which the “big clubs” would then bear. In addition, if they really succeeded in creating such a league with 16 clubs, every club would lift a trophy only every 16 years, on average. It is hard to imagine that the owners and executives running these clubs at the moment and also their fans can really adapt to such a “trophy tax” situation.

8. Outlook

Football clubs are strongly interconnected because they jointly produce the championship race. If some clubs go out of operation in mid-season, the credibility of the entire championship is severely harmed through incomplete schedules. Financial domino effects get triggered because bankrupt clubs no longer fulfill their obligations from transfer deals, which brings other clubs in danger.

Clubs that manage to break even and live within the income generated in the football market are sustainable and do not produce this kind of negative externalities. In that sense, the clubs respecting the break-even requirement and the no-overdue-payables rule behave in a “financially fair” way. The FFP regulation derives its specific notion of “fairness” from this link to the overall goal of systemic financial stability. Given the numbers presented, it seems difficult to deny that the football industry has become financially much more stable since the introduction of FFP.

However, systemic financial stability is not the only concern among the stakeholders of the European football industry. Polarization raises new challenges. The “normal” solution for the problem of “unequal pairings” would be to abolish overlapping competitions and create a European “super league” with promotion and relegation on top of the domestic leagues. However, the strategy of the “big clubs” is not compatible with this model. Their “perpetual hermetic super league project” has been used as a threat to improve their bargaining power in negotiations with UEFA. So far, they succeeded to capture ever larger pieces of the Champions League “pie”, while continuing to simultaneously play and earn money and lift trophies in their prosperous domestic leagues.

In conclusion, if this path continues into the future, polarization and the question of adequate regulation will presumably remain the hot topics of the coming years. Recently, UEFA has announced the reform of the Europa League and the introduction of a third level of club competitions

40. In the context discussed here, this can be interpreted as a first “corrective move”. Given that the “big clubs” already profit from overlapping competitions, the reform creates the chance for more football clubs in Europe to profit from simultaneous participation in domestic and European competitions, thus redirecting some revenues and attention to the lower levels of the pyramid.