Abstract

This paper analyzes whether the Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations set by Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) have influenced the auditing fees charged to football clubs. In addition, it explores the determinants of audit fees. We used a two-sample t-test with equal variances to determine whether differences are present. After this, we carried out a panel data regression with the clubs fix effect to estimate the determinants of audit fees in football clubs. Our findings revealed an increase of audit fees after the implementation of FFP regulations. On top of that, audit fees were explained by the presence of foreign investors if the audit firm was one of the Big 4 and if the auditor was a woman. The regulation change has had an impact on the audit fees charged by auditors for their services. However, this increase may be compensated over future years given the improving financial situation of clubs; therefore, the auditors’ risk diminishes and subsequent audit fees may be reduced. UEFA should monitor audit fees as well as the quality of the audit reports, which have become crucial to obtaining the license to participate in UEFA competitions.

Keywords:

football; audit fees; audit shopping; Financial Fair Play; UEFA; JEL Classification:

Z2; M41; M42

1. Introduction

Increasing debts and persistent deficits have characterized the financial situation of most of the European football clubs (Ascari and Gagnepain 2006; Barajas 2004; Barajas and Rodríguez 2010; Boscá et al. 2008; Deloitte 2014; Gammelsæter 2010; García and Rodríguez 2003; Gay 2009a, 2009b; Robinson and Simmons 2014; Storm and Nielsen 2012). Serious financial problems due to the imbalance between revenues and expenses and the subsequent increase in debt have affected European football; for this reason, some clubs are or have been on the edge of bankruptcy. Numerous clubs have been under administration. Kuper and Szymanski (2009) pointed out that 40 professional English football clubs were involved in processes of insolvency between 1992 and 2008. Beech et al. (2010) indicated that over half of the clubs in the Premier League and the English Football League Championship in season 2008–2009 had been insolvent over the last years. In Spain, at the end of 2011, 22 clubs were or had been under administration (Barajas and Rodríguez 2014).

Concerned with the financial health of the clubs, the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) approved the Financial Fair Play (FFP) Regulations in 2010, subsequently updated in 2012 and 2015. Since 2011, all clubs taking part in competitions organized by UEFA have had to fulfill the requirements of the FFP. These regulations aim to ensure the long-term financial viability and the sustainability of the clubs. They should be managed in break even, avoid reporting negative equity changes, set overdue payables, and finally prove their going concern ability (Morrow 2014; UEFA 2010).

The FFP Regulation stipulates that an independent external auditor must audit clubs’ financial statements. UEFA assesses the content of the auditing report and can deny the license if (i) the report has a disclaimer of opinion or an adverse opinion, (ii) the auditor’s report either has an emphasis of matter or a qualified ‘except for’ opinion in respect of going concern, and (iii) the auditor’s report has, concerning a matter other than going concern, either an emphasis of matter or a qualified ‘except for’ opinion, but they are significant in expressing the true and fair image of the equity and financial results of the club.

Failure of the clubs to meet the criteria established by the FFP Regulation may lead to sanctions and the denial of the license for participation in UEFA competitions. This could lead to serious losses for the sanctioned club, since competitions, such as the Champions League or the Europa League, provide clubs with significant revenues, thus potentially jeopardizing their financial viability (Dimitropoulos 2016).

Therefore, the role of auditors will become even more relevant. In many countries, when the football clubs presented their audited accounts, the opinion of the auditors had no repercussions on sporting. However, as previously explained, the implementation of the FFP has converted the opinion of the auditor into a crucial factor. In this way, auditors will increasingly become responsible for expressing their opinion. Along with this, audit efforts will have to be greater given the current financial problems of the clubs. The relevance of having an unqualified opinion can exert pressure on the auditor. Ruiz-Barbadillo (2016) asserts that an unqualified opinion for the users may generate an extra cost for the company and its managers. This fact implies pressure on the auditor to provide a positive opinion, which is a threat to the independence of the auditor. This possible attitude, on top of being fraud, could actually damage the interest of the shareholder and affect stakeholders using the financial information (De Angelo 1981; Archambeault and DeZoort 2001; Ruíz-Barbadillo and Gómez-Aguilar 2007).

On the other hand, the weak financial position of numerous football clubs—some of which have serious on-going problems—will increase the risk of the auditors and affect their work. The studies of Simunic (1980), Simunic and Stein (1996), Seetharaman et al. (2002), Choi et al. (2008), and Francis and Wang (2008) support the theory that auditors increase their effort in high risk environments. If the perception of business risk is higher, the auditors increase the audit procedures. This implies more evidence to be gathered, more time, more personnel, and consequently, higher fees (Mautz and Sharaf 1961; Davis et al. 1993; Bell et al. 2001; Bell et al. 2008; Bedard et al. 2008; Asthana et al. 2009; Redmayne et al. 2010).

Previous studies show that audit risk will be determined for the client business risk as well as for the financial reporting risk. In this regard, football clubs operate in a very competitive context. Part of their business is the transfer of players for huge amounts of money in comparison with their revenues. Moreover, those players receive extremely high salaries in order to maintain them. This leads to the fact, that, in many cases, club finances are affected by increasing debts and persistent deficits, leading to some clubs having real continuity problems (going concern problems), some of them operating on the verge of bankruptcy (Barajas and Rodríguez 2010; Dimitropoulos et al. 2016). In this environment, auditors must increase their audit procedures in order to evaluate the club’s compliance with the going concern principle. They have to reduce the risk of issuing an inadequate opinion (for example, issuing a more favorable opinion than the client deserves and then the company goes bankrupt). Brumfield et al. (1983) assert that when an audit firm accepts a client with high business risk the auditor reacts to that risk increasing the time for audit work. Auditors face higher chances to be sued if their clients go into bankruptcy or if they have extremely high losses (Rittenberg et al. 2012). Bell et al. (2001) also found a positive relationship between business risk and audit fees. They sustain that the increase in the audit fees is solely due to the higher number of working hours needed and that the auditor will try to be on the safe side with an additional audit effort when bigger losses are expected.

When auditors carry out their work in entities experiencing financial problems, the audit risk of issuing an inappropriate opinion will increase and subsequently the litigation risk will be higher. The relationship between litigation risk and increment in audit fees has been studied by Badertscher et al. (2014), Choi et al. (2009), Venkataraman et al. (2008). Abbott et al. (2017, p. 1104) affirm that these studies obtain evidence that ‘as the imposition of expected auditor losses from legal liability increases, ceteris paribus, audit fees will increase because auditors exert more effort to reduce audit firm litigation risk, charge a pure premium for bearing increased exposure to litigation risk, or both’. Seetharaman et al. (2002) and Venkataraman et al. (2008) found evidence on the relation between litigation risk and audit fees as well. In particular, they observed that auditors raise their fees when their exposure to litigation increases. Badertscher et al. (2014, p. 307) assert that auditors respond to the eventuality of litigation by increasing their fees in order to ‘(i) to cover the cost of increased audit production effort, (ii) to reduce the audit firm’s risk of failing to detect material misstatement, or (iii) to add a risk premium for higher expected future litigation costs’.

Aware of the financial reporting risk in football clubs, UEFA has set strict financial rules in the FFP Regulations to ensure clubs’ financial sustainability. These regulations affect the audit work because changes or new regulations usually imply a higher auditing effort. This is due to the additional time for learning the rules and the additional time (working hours). Subsequently, the audit fees will be affected. In this sense, previous studies, such as Griffin et al. (2009), Vieru and Shadewitz (2010), Kim et al. (2012), De George et al. (2013), De Fuentes and Sierra-Grau (2015a), Higgins et al. (2016), and Lin and Yen (2016), have studied the impact of new rules or changes in regulations on audit fees in several countries from an accounting perspective. Menon and Williams (2001), Oxera Report (2006), Raghunandan and Rama (2006), Griffin and Lont (2007), Ghosh and Pawlewicz (2009), Huang et al. (2009), Salman and Carson (2009), Charles et al. (2010), and De Fuentes and Sierra-Grau (2015b) have analyzed the impact of changes in auditing standards on audit fees. However, no paper has analyzed the impact of FFP Regulation implementation on audit fees charged by football club auditors. Dimitropoulos (2016) pointed out the need for future research on audit fees paid by clubs before and after FFP implementation. This paper aims to fill this gap in the literature. To this end, we have used the Spanish clubs in First Division during the period 2007 to 2016 as the sample to be tested. FFP regulation was inexistent from 2007 to 2010, the period from 2010 to 2013 was a transition period, and FFP regulation was totally implemented throughout 2014 to 2016. Additionally, this paper also studies the factors that determine audit fees.

This paper makes two main contributions; firstly, it examines one of the economic consequences of implementing FFP regulations and analyzes its effect on audit fees. Secondly, it analyzes the behavior of audit fees within a particular context, namely the football industry.

The methodology that is employed is in line with previous studies. After a t-test to determine the presence of significant changes in audit fees, we use an OLS to test the hypothesis that the change in regulation and other variables affects the audit fees. The model includes features that are related to both the auditor and the clubs.

As aforementioned, this paper analyzes the clubs in the Spanish First Division. These clubs can qualify for the UEFA competitions (Champions League and Europa League) and they would need the UEFA license to do so. The period under study began in 2007–2008 and spanned until 2015–2016. The study divides this period into three periods: Pre-FFP, the time before the regulations were set (from June 2007 to 2010); trans-FFP, a transitory period (from June 2010 to 2013); and, FFP, when the regulations fully apply (from June 2013 to 2016). Dimitropoulos (2016) and Dimitropoulos et al. (2016) have employed similar divisions. Financial data have been deflated. We have therefore worked with real (not nominal) prices.

The results show that the new FFP rules have increased audit fees in real terms. Moreover, audit fees are explained by the presence of foreign investors if the audit firm is one of the Big 4 and if the auditor is a woman.

The remainder of this paper is organized, as follows; Section 2 provides an overview of the relevant literature and introduces the hypotheses, while the model and data are described in Section 3 and the results are presented in Section 4. Section 5 summarizes the main findings and discusses some implications.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

The literature evidences that the implementation and changes in rules of both accountancy and auditing have driven to increased audit fees. Changes in account rules affect the audit fees because auditors will need to invest in acquiring the necessary knowledge on the new rules, which will subsequently increase their cost. Moreover, the inherent risk of the financial statements will increase, and in turn, the audit risk. According to De Fuentes and Sierra-Grau (2015a), IFRSs implied a significant change for most European countries. Their results show that, between 2004 and 2006, audit fees increased for the group accounts of Spanish listed companies given the incremental costs that are associated with the mandatory adoption of IFRS. On the other hand, they also reflect an increase for parent audit fees in 2008 with the new domestic accounting rules.

Griffin et al. (2009) found that the audit fees increased significantly in the year prior to IFRS adoption, the year of adoption, and in subsequent years in New Zealand. Higgins et al. (2016) confirm the results of Griffin et al. (2009), indicating higher audit fees post-IFRS, but they extend the prior analysis by considering a longer sample period (2002–2012).

Vieru and Shadewitz (2010) indicate that IFRS adjustments, as a measure of the disparity between Finnish Accounting Standards (FAS) and IFRS, positively and significantly affect total audit fees paid to statutory auditors. Additionally, Kim et al. (2012) conclude that mandatory IFRS adoption leads to an increase in audit fees, which suggests that the increase in audit task complexity is the driving force behind the IFRS-related audit fee increase. In the same line, De George et al. (2013) provide evidence of a directly observable and significant cost of IFRS adoption. Their results imply an overall increase of approximately 9 percent in the average level of audit fees in the year of IFRS adoption.

For a sample of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, Lin and Yen (2016) found that auditors with IFRS experience charged significantly higher audit premiums in the initial years of IFRS adoption. They also found that audit clients with IFRS experience paid significantly lower incremental fees. In the UK, the Oxera Report (2006) identified high audit fees between 2002 and 2004 due to changes in regulation and accounting rules.

Regarding auditing rules, Menon and Williams (2001) observed increased audit fees between 1980 and 1997. In particular, they noted a significant increase in 1988, when the Auditing Standards Board issued the “expectation gap” standards. Most of the research focuses on the implementation of the Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX 2002), which revealed high audit fees that were charged to customers during the post-SOX period in relation to the pre-SOX period as consequence of the increased auditing procedures, increased liability litigation, and a more highly regulated audit environment.

Thus, for the United States, Raghunandan and Rama (2006) examine the association between audit fees and internal control disclosures pursuant to section 404 of the SOX Act, which requires management and the auditor to report on internal controls over financial reporting. They found that audit fees for the firms were on average 86 percent higher for fiscal 2004 than the corresponding fees for 2003.

Huang et al. (2009) hypothesized that initial-year audit fee discounts would be less likely in the post-SOX period than in the pre-SOX period. They examined the audit fees for clients changing auditors in 2001 and 2006 and found that there was a significant initial-year audit fee discount in 2001 for clients of the Big 4 audit firms. The new clients paid, on average, about 24 percent less than continuing clients. In contrast, a significant premium for new Big 4 clients was present in 2006. Initial-year client premiums were, on average, 16 percent higher than those of continuing clients.

Charles et al. (2010) found a positive statistically and economically significant relationship between financial reporting risk and audit fees that were paid to Big 4 auditors. The relation between financial reporting risk and audit fees strengthened significantly in 2002 and 2003. This is consistent with a shift in the way auditors priced risk in likely response to the events surrounding the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.

Regarding football, as mentioned in the introduction, the FFP regulations implemented by UEFA will imply a more influential role on the part of the auditors in this process. One way to see this is to consider audit fee changes. Silva et al. (2016) highlight the relevant role of independent audits in the reduction of informational asymmetry in the football industry. The perception is that a special role can bring about changes in auditor service charges. Moreover, Dimitropoulos et al. (2016) evidenced that club managers became more inclined towards aggressive Earning Management after the FFP regulation was established. They additionally found that club managers tended to move from big-4 company auditors to local auditors. Moreover, these authors consider that regulatory monitoring that is related to accounting data will inevitably lead to a deterioration in accounting quality. Nevertheless, financial statements must be audited by independent auditors and the reports must be ‘clean’; new tensions are thus likely to appear and may be reflected in the audit fees. For this reason, studying audit fees sheds light on a wider debate than just auditor earnings; audit fees point to a deeper effect in the changes brought about by FFP regulation.

Therefore, according to the previous evidence, audit fees are expected to increase with the establishment of the FFP regulation given the greater auditing effort and risk with higher exposure of their responsibility when the auditors send opinion. The weak financial situation of many football clubs implies a greater audit effort due to the higher perception of auditor risk. This perception of risk usually represents more working hours and therefore higher fees. The FFP regulation emphasizes the going concern. If auditors perceive symptoms of going concern, they will modify the audit processes to investigate the impact of risk factors in depth. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Auditors increase their audit fees after implementing Fair Play regulation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

The study conducts the empirical analysis for the football teams of the Spanish First Division. It uses the information included in the individual annual accounts and their corresponding audit reports. Financial Statement are reported according to Spanish GAAP, rather than using the IFRS. We have gathered this information from several sources: websites of football teams, Spanish Professional Football League (La Liga), House of Companies, and the Amadeus database. Therefore, the initial sample consists of data from 20 football teams with a nine-year follow-up for each of the seasons between 2007/08 and 2015/16, that is, 180 records. We have only analyzed the first division teams as they are the ones that have the chance to qualify for UEFA competitions (Champions League and Europa League). Finally, the data for Osasuna (from 2009/10 to 2012/13), Xerez (2009/10) and Levante (2007/08) are missing. Therefore, the database contains 174 records. None of the Spanish football clubs were listed on the stock exchange. As there is promotion and relegation, we have an unbalanced panel.

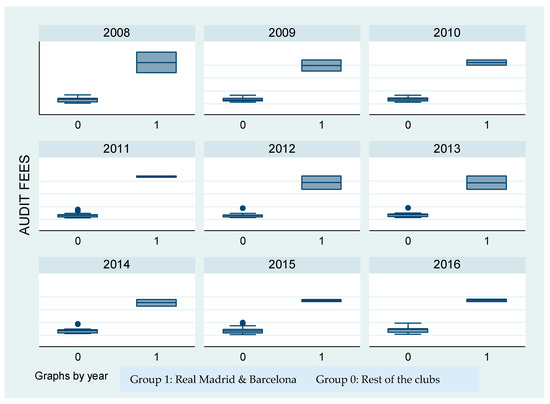

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, the audit fees paid by Real Madrid and Barcelona (group 1 in the graph) are much higher on average than those that are paid by the rest of the clubs (group 0 in the Figure 1). This is why Real Madrid and Barcelona have been excluded from the sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for Real Madrid (RM) and Barcelona audit fees and those of the rest of the clubs. (Data in Euros corrected for inflation).

Figure 1.

Differences, on average, between the Real Madrid and Barcelona audit fees and those of the rest of the clubs.

Before analyzing the factors that explain the audit fees, we conducted different t-tests for the two samples to detect significant differences among the three periods. First, the comparison is between each of the periods and the rest (Table 2 and Table 3). We do this on the sample without Real Madrid and Barcelona and when comparing real values to avoid problems with inflation.

Table 2.

Two-sample t-test with equal variances (pre-FFP).

Table 3.

Two-sample t-test with equal variances (Financial Fair Play (FFP)).

The audit fees in the period before the FFP are slightly lower than the two other periods. However, the transition period showed no significant difference in audit fees. Secondly, the audit fees in the period of full FFP implementation are significantly higher than those of the two previous periods (Table 3).

As it has been said, there is no statistically significant difference between the audit fees in the transition period regarding the fees before the implementation of FFP and the fees when the FFP was fully implemented. As it could be expected that rational clubs and auditors could have used the transition period to adapt the fees, we have also compared the fees before FFP and when the regulations are fully implemented. Table 4 presents the results. The difference is significant, and clubs with the FFP Regulation implemented pay that is, on average, €3569 more in audit fees. This amount is presented in real terms.

Table 4.

Two-sample t-test with equal variances (pre-FFP vs. FFP).

3.2. Regression Model and Variable Definitions

The model proposed by Simunic (1980) is the starting point for literature on the study of fees. In this seminal work, audit fees are considered to be a cost in the client’s accounting system, which clients attempt to minimize.

The research conducted so far in different countries signals a set of independent variables that are linked to the determination of audit fees for both the audited company and the auditor. The variables related to the audited company are fundamentally size, complexity and risk.

Following Simunic (1980), the model used to explain audit fees and test the stated hypothesis presents the following expression:

Table 5 presents the variables included in the model. The dependent variable is the amount of money paid for audit services. As well as the other financial variables, this variable has been taken in real terms adjusted for inflation. In the model, three dummy variables reflect the different periods that are under scrutiny in this paper. They are related directly to FFP. The seasons before the FFP (PRE_FFP) are considered as a basis. The total assets variable has been included to control for size. We have considered whether the owner of the club is a foreigner as a factor that may increase the audit fees. We have also included other variables to analyze the impact of risk, these being ROA, leverage, liquidity, whether the club had losses in the previous season, and whether the auditing report presented going concern opinion. The features of the auditor are included to analyze the effect of the auditor being one of the Big 4 and whether choosing to change the auditor and selecting an auditor of another gender affects the fees and the perception of non-audit fees by the auditor. Our work includes the report lag in the audit report to capture the potential existence of more complex audit work. Finally, we introduce the possible effect of sporting factors in the model through the points that were obtained in the previous season, the average attendance to the stadium and whether the club participated in the previous season UEFA competitions. The following subsections explain all of these variables.

Table 5.

Description of the variables included in the model and expected sign (financial variables in real terms).

Table 6 presents the values of the sample variables. The first thing to remark is that upon using lagged variables to avoid problems of lag causality, the number of observations drops considerably. However, when using the variables of the same year, the results of the regression are similar. In that sense, we consider that it is better to maintain the lag variables. Audit fees in real terms vary notably from the fees that are paid by SD Eibar in 2015—a promoted team with healthy ratios of liquidity (1.73), leverage (0.47), ROA (0.31)—and the fees paid by Valencia CF in 2015, a club struggling with huge financial problems (losses over 1.7 million Euros, low liquidity and high leverage). Many clubs (42.95%) do not contract non audit services. RCD Espanyol and Valencia CF spent €45,320.98 and €55,362.68, respectably in 2016. The amount paid that year by Valencia CF was higher than the maximum amount paid for audit fees in the whole period. Two clubs—CD Osasuna and Hercules CF—had a delay of more than two years in presenting the audit report for season 2011. Some figures on financial ratios may sound odd. However, studies on the finances of Spanish football show that these values have not been very uncommon (see for example Ascari and Gagnepain 2006; Barajas and Rodríguez 2010; 2014). ROA is negative in 37.74% of the observations. In the case of Hercules CF, in 2011 its operating losses were higher than its total assets. That season, the club had returned to First Division after more 14 years and made a big effort to be competitive by hiring well-known players. However, at the end of the season the team ended second to last and was relegated. This fact meant huge losses, further relegation to Second B Division, and it is on the brink of disappearing. On the other hand, there are also cases with high ROA. Having entered under administration in 2011 and attaining its best league position in 2013 while simultaneously qualifying for the UEL (the club did not receive the UEFA license due to its financial situation), Rayo Vallecano SAD made a remarkable profit in 2014. Clubs with high values in Leverage ratio usually benefit from having been under administration. That is the case of RC Deportivo de La Coruña in 2015 and 2016 (4.5 and 3.6, respectively). It is also worth noting that the audit reports of the clubs presented ongoing concerns in 53% of the cases. Almost 40% presented losses in the previous year. This situation is improving in the period of fully implementation of FFP regulations (29.6%). In only 9% of the cases is there a foreign owner, and the auditor is one of the Big 4 in only 3%.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics (financial variables in real terms).

3.2.1. Regulation

As stated, Griffin et al. (2009), Vieru and Shadewitz (2010), De George et al. (2013), De Fuentes and Sierra-Grau (2015a), Higgins et al. (2016), and Lin and Yen (2016) have analyzed the impact of changes in accountancy rules, or the impact of new ones on audit fees. Menon and Williams (2001), Ghosh and Lustgarten (2006), Raghunandan and Rama (2006), Griffin and Lont (2007), Ghosh and Pawlewicz (2009), Huang et al. (2009), Salman and Carson (2009), Charles et al. (2010), and De Fuentes and Sierra-Grau (2015b) have studied the impact of changes in auditing rules. Most of these studies distinguish between two or three periods: before the application of the regulation, during the first years of implementation, and after the implementation. This paper analyzes the time before the FFP (seasons 2007–2008, 2008–2009, and 2009–2010), a transitory period (2010–2011, 2011–2012, and 2012–2013), and the period when the FFP was fully implemented (2013–2014, 2014–2015, and 2015–2016). The first period is the basis. Audit fees are expected to be higher after the transitory or full implementation periods than they were before the new rules. The complexity of the audit work will increase with a subsequent increase in auditing effort. Moreover, the responsibility of auditors will be more highly exposed when they report their opinion.

3.2.2. Non Audit Fees

Studies trying to conjunctly determine the fees for audit and non-audit services have observed interdependency between both fees and they have identified the presence of efficiencies deriving from the exchange of knowledge between both activities (Monterrey and Sánchez 2007). Simunic (1984) discovered a positive association between both fees. He concluded that firms hiring non-audit services from the same auditor assume cost in the audit fees that are higher than those assumed by firms that do not do so. Palmrose (1986) and Bell et al. (2001) point out that the positive coefficients that are associated among audit and non-audit fees originate in scale economies that reduce the number of required auditing hours. Nevertheless, other authors, like Stein et al. (1994) and Whisenant et al. (2003), did not find a direct relationship between both variables.

3.2.3. Size of the Firm (the Club)

The size of the club is a widely tested explanatory variable and, according to Hay et al. (2006) it typically explains more than 70% of the variation in audit fees. This paper uses the lagged total assets in real terms of the company to avoid endogeneity. Casterella et al. (2004), and Basioudis et al. (2008) also use total assets to control for size. We expect a positive association with audit fees.

3.2.4. Foreign Ownership

Wilson et al. (2013) assert that foreign ownership may help clubs to improve their accounts, make them sustainable and improve their finances. At the same time, foreign investors have more difficulties in getting information than the local ones (Beneish and Yohn 2008; He et al. 2014). To compensate for this, foreign investors will look for more qualified auditors (Dimitropoulos 2016). We therefore expect a positive relationship regarding audit fees.

3.2.5. Delay in the Report

The existence of problems can imply longer periods of time to finish audit reports (Knechel and Payne 2001). Stanley (2011) found a positive relationship between audit fees and the time spent until the final audit report. More complex audit work may take longer to perform and it may imply a subsequent delay in the signing of the audit report. In such case, higher fees are expected. This is why the model includes the variable REPORTLAG.

3.2.6. Risk

Extensive literature reveals that the audit fees are positively related to risk, as evinced in the papers by Xu et al. (2013), Zhang and Huang (2013), Alexeyeva and Svanström (2015), and Groff et al. (2017). That is, higher client risk may expose the auditor. The auditor will then apply more tests and thereby increase the time employed. Thus, fees would be higher. Several variables measure risk direct or indirectly. ROA is included because a low return on assets may be symptomatic of mismanagement. We would therefore expect a negative relationship.

Leverage (LEV) and liquidity (LIQ) ratios, two of the proxies that are most commonly used to measure indebtedness (Hay et al. 2006; Hay 2013), reflect whether the club could have financial problems. A positive relationship between leverage and audit fees is expected (Callaghan et al. 2009; Casterella et al. 2004). On the contrary, a negative relationship is expected with the liquidity (Craswell et al. 1995; Simunic 1980).

Moreover, Casterella et al. (2004), Callaghan et al. (2009) find that firms with losses (LOSS) represent higher risk. This would imply higher audit fees as well.

3.2.7. Additional Risk

Football clubs have real financial difficulties in their operations (Ascari and Gagnepain 2006; Barajas and Rodríguez 2010 and 2014; Beech et al. 2010; Boscá et al. 2008; Kuper and Szymanski 2009), which in some cases have led to bankruptcy. This creates an additional risk for the auditor. The auditor will have to pay special attention to these events, which can imply going concern. Audit fees are expected to be higher in the presence of a going concern opinion (Krishnan and Wang 2015; Stanley 2011; Wang and Chui 2015).

3.2.8. BIG 4

Previous studies indicate that the big international audit firms have a differential reputation that is derived from having a recognized brand name, and deliver audits of a higher quality than small and medium-sized audit firms (DeAngelo 1981; DeFond 1992). The existence of a relationship between audit fees and an auditor’s reputation has been studied by various authors with positive results. This is the case of Liu (2007), Monterrey and Sánchez (2007), and Whisenant et al. (2003). The variable BIG 4 has been included in the model as a dummy variable, making a distinction between the Big 4 (PwC, E&Y, KPMG, or Deloitte) and the other firms. A positive relation with the audit fees variable is expected.

3.2.9. Auditor Change

One of the most common reasons given by clients for deciding to change auditor is that the audit fee will decrease. Lower audit fees can have their origin in the intention of audit firms of attracting new customers (lowballing). Another reason would be that the new auditor can offer a more efficient service which could reduce their fees. Regardless of the reason for the decrease in the fees, previous research suggests that the continuity of the auditor must be considered in the audit fees models. The two most common proxies that are used to include the continuity of the auditor are a dummy variable that reflects a recent change in the auditor and the actual length of the current auditor in that role (Hay et al. 2006). Hay (2013), Wang and Chui (2015), and De Fuentes and Sierra-Grau (2015a) use a dummy variable that reflects the auditor change. This paper also includes this variable and expects it to be negatively related to audit fees.

Auditor Features

Gul et al. (2013), Ittonen and Peni (2012), Ittonen et al. (2013), and Sundgren and Svanström (2014) have recently studied the effect of auditor features on auditing service quality. Hardies et al. (2015) affirm that audit fees may be higher for female auditors due to greater engagement effort (i.e., more hours) by female auditors. Female auditors may demand more audit effort because of systematic differences in knowledge, skills, abilities, preferences, and behavior. Ittonen and Peni (2012) found that audits performed by women in Denmark, Sweden, and Finland were more expensive that those performed by men. These authors justify their results due to the existence of factors, such as gender differences in risk tolerance, which may affect pricing decisions by increasing the audit investment and/or increasing the audit fee risk premium. In addition, they also refer to female auditors’ diligence, lower overconfidence, and higher level of preparation could also lead to an increase in audit investment, and thereby result in higher audit fees.

Ittonen et al. (2013) refer to several papers considering cognitive psychology and behavioral economy that have found the existence of important gender differences related to information processing, diligence, conservatism, overconfidence, caution, and risk tolerance (Eckel and Grossman 2002; Nettle 2007; Schmitt et al. 2009). Other studies affirm that women are more conservative and risk adverse than men, and that their behavior is less risky when making economic and financial decisions (Barber and Odean 2001; Dwyer et al. 2002; Watson and McNaughton 2007). Our model includes a variable considering gender and we expect a positive association with audit fees.

Sporting Features

We expect those teams with better performance in the previous season to be capable of increasing their clubs’ revenue and reducing financial risk. However, some clubs could overspend to achieve good sporting performance and this would make risk higher. Therefore, the sign of the coefficient could be positive or negative. After the FFP, with higher financial control, the chances of getting a negative sign could be greater.

On the other hand, we may expect reduced club risk if the average attendance to the stadium is high, because it reflects a wide fan base that would help to increase revenues. If the risk is low, the audit fees should also decrease. Therefore, the model includes variables that gather the information about points (performance measure) and average attendance in the previous season.

Finally, we have also included participation in the previous edition of UEFA competitions (Champions League and Europa League) to reflect the effect of sporting features. If a team took part in previous editions, it had to fulfill financial requirements in that season and this facilitates the fulfillment of the financial requirements of the current season. What is more, participation usually provides extra revenue to the club and it may reduce an eventual going concern situation under financial control.

4. Results

We have verified the Hypothesis (H1). The results are presented in Table 7. It has been demonstrated that on average auditors significantly increased their audit fees after implementing Fair Play regulation in comparison to pre-implementation fees. On average, the difference is slightly lower than €3500 in real terms.

Table 7.

Outputs of the regression (real terms).

On the other hand, some results regarding the determinants of audit fees in football clubs corroborate what was expected. However, most of the variables do not present a significant influence on audit fees. First, we find that the audit fees increased by nearly 1700 Euros (2000 in nominal terms) in the transition period as compared to the period in which FFP did not exist. That amount was practically two-fold in the period of full FFP regulation implementation. This was the expected result, even more so after the t-test.

Foreign ownership is another significant factor that explains the audit fees. In clubs with local owners, audit fees increased by nearly 4500 euros in the advent of foreign investment.

If the auditor is one of the Big 4, then audit fees are about 11,700 Euros higher than those of smaller audit firms, which falls in line with previous research. We should point out that apart from Real Madrid and Barcelona—both excluded from this analysis—only Sevilla CF and Valencia CF were audited by a Big 4 audit firm in seasons 2014–2015 and 2015–2016, in addition to Málaga CF in season 2015–2016, periods in which the FFP regulations were fully implemented. Moreover, Valencia CF and Málaga CF have foreign investors. On the other hand, only Ernst and Young and Deloitte, both of which belong to the Big 4, had audited football clubs throughout the whole period.

Another interesting result is that when the auditor is a woman, audit fees are about 3500 Euros higher than when the auditor is a man. It should be noted that only one of the female auditors works for a Big 4 (Ernst&Young). Recent studies find similar results when considering the gender of the auditor. Ittonen and Peni (2012) introduced gender differences in risk tolerance as potential reasons to explain this effect. These authors claim that this may increase audit investment and audit fee risk premium. They also point out other factors, such as the diligence of female auditors, lower overconfidence, and a higher level of preparation could lead to an increased audit fees. Moreover, Ittonen et al. (2013) found that female auditors might have a constraining effect on earnings management, which may also contribute to higher audit fees. The results obtained by Hardies et al. (2015) show that firms pay higher audit fees (by about 7 percent) to female auditors. They suggest the existence of a female audit fee premium due to differences in knowledge, skills, abilities, preferences, and behavior or due to supply-side factors. Hu et al. (2014) found that female auditors charge significantly higher audit fees than their male counterparts. They explain that this is due to female auditors’ preference for reducing audit risk. In the case of football clubs, the perception of risk by female auditors may also be a plausible reason.

No evidence supports the possible influence of sporting factors on audit fees, which could possibly be explained by the absence of a relation between sports performance and economic results in Spanish football (Barajas et al. 2005). Variables that are related to risk have resulted in being non-significant as well. Increased risk for the auditor was expected to increase audit fees. In this sense, we expected that higher leverage, and the presence of losses and going concern opinion, to have an impact on higher audit fees. On the contrary, a higher return on assets and liquidity ratio resulted in lower risk and lower expected audit fees too. However, none of these variables were significant. This may be related to the real influence of the FFP regulations on club finances. In fact, as shown in Table 8, the financial situation of clubs improved on average. Throughout the period when the FFP regulations were fully implemented, the return on assets was much higher on average than it had been in the previous periods. The average of these three years was 11.5%, while the average of both previous periods was negative. A similar situation arose with the other indicators. The leverage was around 1 on average in the last period; this was lower than it had been in the previous years. Liquidity clearly improved with a 0.82 average over the last three years as compared to its prior 0.6 average. The number of clubs declaring losses declined to less than a third as compared to the peak of the whole period, in which over 60% of companies had reported losses. Finally, the percentage of clubs with problems of going concern dropped notably over the last years, especially in 2016. All of this may explain the contribution of FFP regulations to improving the financial situation of the clubs, thereby reducing risk and not influencing the fees that are charged by the auditors. This may represent a problem of endogeneity, but we must recall that we used lagged variables in the regression to avoid this.

Table 8.

Evolution of risk indicators.

We have included clubs fixed effect as there are features of the clubs that remain constant throughout the period. It is interesting to observe which clubs pay more or less than the base team, which is Almeria CF in our case. The clubs that pay significantly higher audit fees are Atletico de Madrid (understandable due to its size), Athletic de Bilbao, Deportivo de la Coruña, Osasuna, Racing de Santander, Rayo Vallecano, Real Sociedad, and Zaragoza CF. Most of these clubs had faced serious financial problems. On the other hand, the clubs that pay significantly less are Eibar, Getafe, and Granada CF. All of them are ‘small’ clubs and Eibar had only been in First Division in the last 2 seasons, and for the first time in its history.

5. Summary and Discussion

As it has been proven, the audit fees have grown in real terms after the implementation of FFP regulations. Moreover, audit fees are explained by the presence of foreign investors, having one of the Big 4 as the auditing firm and having a female auditor. The fact that the Big 4 audit companies charge higher audit fees seems clear. The fact that the presence of a female auditor may increase the fees is surprising, but it is even more surprising to find that other studies have obtained results akin to ours. These studies explain the higher audit fees given female auditors’ perception of risk. This may be relevant in the case of football clubs, which are ‘risky businesses’.

This paper makes two main contributions. On the one hand, it analyzes the economic consequences of the implementation of FFP regulations by mainly considering their effect on audit fees. On the other hand, the behavior of audit fees is analyzed within a particular context, the football industry. It reveals no influence of sporting factors, even when they had been expected.

With respect to the implications of the paper, it seems that the change in regulations has had an impact on audit fees charged by auditors for their services. However, this increase may be compensated over future years because the clubs’ financial situation is improving, and, subsequently, the risk taken by auditors is diminishing. This facilitates the reduction in audit fees. UEFA should monitor whether the audit fees are reasonable as well as the quality of the audit reports, which have become crucial for obtaining a license to participate in UEFA competitions.

Audit fees are symptomatic of the deeper effects of the changes brought about by FFP regulation. Furthermore, the role of auditors imposed by UEFA can contribute to avoiding the problem of earning management, as pointed out by Dimitropoulos et al. (2016).

This study presents some limitations. Some of them are derived from the nature of the study and it is almost impossible to address them. One of them is the problem of the size of the sample, but only 18 clubs each year (as Real Madrid and Barcelona are excluded) are affected by these regulations. Nevertheless, Hay et al. (2006) present a summary of 148 papers on audit fees describing the sample. The size of the samples varies, but 20.3% of the papers have a sample smaller than 100 and 46.6% smaller than 200. The size of the sample is relevant when the model includes many independent variables, as these diminish the degrees of freedom. This problem is common for most of the papers on this issue. However, the results are pretty much similar upon excluding some of the non-significant variables. For that reason, we consider it best to maintain them as they could theoretically determine audit fees.

On the other hand, some variables such as other personal features of the auditors or other types of ownership could be missed, as well as other changes in audit or accountancy regulations. At this point, it is worth remarking that during the period of study some changes in audit or accountancy regulations took place. In accounting matters, the reform of the Spanish General Accounting Plan (Spanish GAAP) was approved in 2007, with the aim of accommodating the new IRFS to Spanish accounting regulations. Subsequently, in 2010, a new modification of the Spanish GAAP standards was made and the rules for the formulation of the Consolidated Annual Accounts were approved. In 2016, new amendments were incorporated into Spanish legislation to comply with the provisions of the EU Directive 34/2013. Regarding auditing, there were two amendments of the Audit Act with the purpose of adapting Spanish domestic legislation to EU Directives 43/2006 EC and 56/2014 in 2010 and in 2015, respectively. These changes overlap the period that we have taken. These kinds of variables could be used for more specific studies on the topic. Moreover, studies with companies from other industries would help to understand if the changes in general regulations affect football clubs in different ways.

The results of this study provide several future research lines. First, it would be interesting to carry out this analysis on other European leagues. Second, it would also be worth studying other possible effects of FFP regulations such as the presence of significant changes in auditor opinion. Third, seeing whether the adoption of FFP regulation would lead to an increased likelihood of clubs choosing a Big 4 accounting firm is a further line of study to be pursued.

Author Contributions

Authors equally contributed to the research and writing of the paper

Funding

This research was funded by National Research University Higher School of Economics in its Basic Research Program.

Acknowledgments

This paper is an output of a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abbott, Laurence J., Katherine Gunny, and Troy Pollard. 2017. The impact of litigation risk on auditor pricing behavior: Evidence from reserve mergers. Contemporary Accounting Research 34: 1103–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeyeva, Irina, and Svanström Tobias. 2015. The impact of the global financial crisis on audit and non-audit fee. Managerial Auditing Journal 30: 302–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambeault, Deborah, and Tood DeZoort. 2001. Auditor opinion shopping and the audit committee: An analysis of suspicious auditor switches. International Journal of Auditing 5: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascari , Guido, and Philippe Gagnepain. 2006. Spanish football. Journal of Sports Economics 7: 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, Shara, Steven Balsam, and Sungsoo Kim. 2009. The effect of Enron, Andersen, and Sarbanes-Oxley on the US market for audit services. Accounting Research Journal 22: 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badertscher, Brand, Bjorn Jorgensen, Sharon P. Katz, and William Kinney. 2014. Public equity and audit pricing in the United States. Journal of Accounting Research 52: 303–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, Angel. 2004. Modelo de Valoración de Clubes de Fútbol Basado en los Factores clave de su negocio [Valuation model for football clubs based on the key factors of their business]. MPRA Paper 13158. Munich: University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Barajas, Angel, Carlos Fernández-Jardón, and Liz Crolle. 2005. Does Sports Performance Influence Revenues and Economic Results in Spanish Football? MPRA Paper 3234. Munich: University Library of Munich. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=986365 (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Barajas, Angel, and Plácido Rodríguez. 2010. Spanish football clubs’ finances: Crisis and player salaries. International Journal of Sport Finance 1: 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barajas, Angel, and Plácido Rodríguez. 2014. Spanish football in need of financial therapy: Cut Expenses and Inject Capital. International Journal of Sport Finance 9: 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, Brad M., and Terrance Odean. 2001. Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. Quarterly Journal of Economics 116: 261–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basioudis, Ilias G., Evangelos Papakonstantinou, and Marshall A. Geiger. 2008. Audit fees, non-audit fees and auditor going-concern reporting decisions in the United Kingdom. Abacus, A Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business Studies 44: 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, John, Simon Horsman, and Jamie Magraw. 2010. Insolvency events among English football clubs. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship 11: 53–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, Jean C., Donald R. Deis, Mary B. Curtis, and J. Gregory Jenkins. 2008. Risk monitoring and control in audit firms: A research synthesis. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 27: 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Timothy B., Rajib Doogar, and Ira Solomon. 2008. Audit labor usage and fees under business risk auditing. Journal of Accounting Research 46: 729–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Timothy, Wayne R. Landsman, and Douglas A. Shackelford. 2001. Auditor´s perceived business risk and audit fees: Analysis and evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 39: 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneish, Messod D., and Teri Lombardi Yohn. 2008. Information friction and investor home bias: A perspective on the effect of global IFRS adoption on the extent of equity home bias. Journal Accounting Public Policy 27: 433–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscá, José E., Vicente Liern, Aurelio Martínez, and Ramón Sala. 2008. The Spanish football crisis. European Sport Management Quarterly 8: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumfield, Craig A., Robert K. Elliott, and Peter D. Jacobson. 1983. Business risk and the audit process. Journal of Accountancy 155: 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan, Joseph, Mohinder Parkash, and Rajeev Singhal. 2009. Going-concern audit opinions and the provision of non-audit services: Implications for auditor independence of bankrupt firms. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 28: 153–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casterella, Jeffrey R., Jere R. Francis, Barry L. Lewis, and Paul L. Walker. 2004. Auditor industry specialization, client bargaining power and audit pricing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 23: 123–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Shannon L., Steven M. Glover, and Nathan Y. Sharp. 2010. The association between financial reporting risk and audit fees before and after the historic events surrounding SOX. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 29: 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jong-Hang, Jeong Bon Kim, Xiaohong Liu, and Dan A. Simunic. 2008. Audit pricing, legal liability regimes, and Big 4 premiums: theory and cross-country evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research 25: 55–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jong-Hang, Jeong-Bon Kim, Xiaohong Liu, and Dan A. Simunic. 2009. Cross-listing audit fee premiums: Theory and evidence. The Accounting Review 84: 1429–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craswell, Allen T., Jere R. Francis, and Stephen L. Taylor. 1995. Auditor brand name reputation and industry specializations. Journal of Accounting and Economics 20: 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Larry R., David N. Ricchiute, and Greg Trompeter. 1993. Audit effort, audit fees, and the provision of non-audit services to audit clients. The Accounting Review 68: 135–50. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelo, Linda Elizabeth. 1981. Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics 3: 183–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fuentes, Cristina, and Eva Sierra-Grau. 2015. IFRS adoption and audit and non-audit fees: Empirical evidence from Spanish listed companies. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting 44: 387–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fuentes, Cristina, and Eva Sierra-Grau. 2015. Industry specialization and audit fees: A meta-analytic approach. Academia, Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 28: 419–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De George, Emmanuel T., Colin B. Ferguson, and Nasser A. Spear. 2013. How much does IFRS cost? IFRS adoption and audit fees. Accounting Review 88: 429–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, Mark L. 1992. The association between changes in client company agency costs and auditor switching. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 11: 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2014. Annual Review of Football Finance 2014 Highlights, Sports Business Group. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/sports-business-group/deloitte-uk-annual-review-football-finance.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Dimitropoulos, Panagiotis. 2016. Audit selection in the European football industry under Union of European Football Associations Financial Fair Play. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 6: 901–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulos, Panagiotis, Stergios Leventis, and Emmanouil Dedoulis. 2016. Managing the European football industry: UEFA’s regulatory intervention and the impact on accounting quality. European Sport Management Quarterly 16: 459–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Peggy, James Gilkeson, and John List. 2002. Gender differences in revealed risk taking: Evidence from mutual fund investors. Economics Letters 76: 151–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, Catherine C., and Philip J. Grossman. 2002. Sex differences and statistical stereotyping in attitudes toward financial risk. Evolution and Human Behavior 23: 281–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Jerre R., and Dechun Wang. 2008. The joint effect of investor protection and Big 4 audits on earnings quality around the world. Contemporary Accounting Research 25: 157–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, José M. 2009a. Fútbol finanzas: La economía de la liga de las estrellas (I). Radiografía económica del fútbol español (temporada 2006–07) [Football finance: The economy of the league of the stars (I). Economic in-depth analysis of Spanish football (season 2006–07)]. Partida Doble 208: 62–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, José M. 2009b. Fútbol finanzas: La economía de la liga de las estrellas (II). Radiografía económica del fútbol español (temporada 2006–07) [Football finance: The economy of the league of the stars (II). Economic in-depth analysis of Spanish football (season 2006–07).]. Partida Doble 209: 62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gammelsæter, Hallgeir. 2010. Institutional pluralism and governance in ‘Commercialized’ sport clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly 10: 569–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Jaume, and Plácido Rodríguez. 2003. From sports clubs to stock companies: The financial structure of football in Spain 1992–2001. European Sport Management Quarterly 3: 235–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Aloke, and Steven Lustgarten. 2006. Pricing of initial audit engagements by large and small audit firms. Contemporary Accounting Research 23: 333–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Aloke, and Robert Pawlewicz. 2009. The impact of regulation on auditor fees: evidence from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 28: 171–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Paul A., and David H. Lont. 2007. An analysis of audit fees following the passage of Sarbanes-Oxley. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics 14: 161–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Paul A., David. H. Lont, and Estelle Y. Sun. 2009. Governance regulatory changes, international financial reporting standards adoption, and New Zealand audit and non-audit fees: Empirical evidence. Accounting & Finance 49: 697–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groff, Maja Z., Domen Trobec, and Aleksander Igličar. 2017. Audit fees and the salience of financial crises: Evidence from Slovenia. Economic Research Ekonomska Istraživanja 30: 922–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Ferdinand, Donghui Wu, and Zhifeng Yang. 2013. Do individual auditors affect audit quality: Evidence from archival data. The Accounting Review 88: 1993–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardies Kris, Diane Breesch, and Joël Branson. 2015. The female audit fee premium. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 34: 171–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, David. 2013. Further evidence from meta-analysis of audit fee research. International Journal of Auditing 17: 162–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, David, W. Robert Knechel, and Norman Wong. 2006. Audit fees: A meta-analysis of the effect of supply and demand attributes. Contemporary Accounting Research 23: 141–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Xianjie, Oliver Rui, Liu Zheng, and Hongjun Zhu. 2014. Foreign ownership and auditor choice. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 33: 401–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Stephen, David Lont, and Tom Scott. 2016. Longer term audit costs of IFRS and the differential impact of implied auditor cost structures. Accounting and Finance 56: 165–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Naw-wei, Wen-si Ouyang, and Ning-jiao Deng. 2014. Research on auditors’ gender and audit fees. Paper presented at 2014 International Conference on Management Science Engineering (ICMSE), Nirjuli, India, May 7–8; pp. 1307–12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Hua-Wei, Kannan Raghunandan, and Dasaratha Rama. 2009. Audit fees for initial audit engagements before and after SOX. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 28: 171–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittonen, Kim, and Emilia Peni. 2012. Auditor’s gender and audit fees. International Journal of Auditing 16: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittonen, Kim, Emilia Vähämaa, and Sami Vähämaa. 2013. Female auditors and accruals quality. Accounting Horizons 27: 205–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jeong-Bong, Xiaohong Liu, and Liu Zheng. 2012. The impact of mandatory IFRS adoption on audit fees: Theory and evidence. The Accounting Review 87: 2061–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knechel, W. Robert, and Jeff L. Payne. 2001. Additional evidence on audit report lags. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 20: 137–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, Gopal V., and Changjiang Wang. 2015. The relation between managerial ability and audit fees and going concern opinions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 34: 139–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, Simon, and Stefan Szymanski. 2009. Soccernomics: Why England Loses, Why Germany and Brazil Win, and Why the US, Japan, Australia, Turkey—and Even Iraq—Are Destined to Become the Kings of the World’s Most Popular Sport. New York: Nation Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Hsiao-Lun, and Ai-Ru Yen. 2016. The effects of IFRS experience on audit fees for listed companies in China. Asian Review of Accounting 24: 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ji-Hong. 2007. On determinants of audit fee: New evidence from China. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing 3: 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mautz, Robert Kuhn, and Hussein Amer Sharaf. 1961. The Philosophy of Auditing. Sarasota: American Accounting Association Monograph, No. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, Krishnagopal, and David D. Williams. 2001. Long term trends in audit fees. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 20: 115–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrey, Juan, and Amparo Sánchez. 2007. Un estudio empírico de los honorarios del auditor [An Empirical Study of auditor’s fees]. Cuadernos de Economía y Empresa 32: 81–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2014. Financial Fair Play-Implications for Football Club Financial Reporting. The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland. Available online: http://www.storre.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/21393/1/ICAS%20Financial%20Fair%20Play%20Report%20-%20Stephen%20Morrow.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Nettle, Daniel. 2007. Empathizing and systemizing: What are they, and what do they contribute to our understanding of psychological sex differences? British Journal of Psychology 98: 237–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxera Report. 2006. Competition and Choice in the UK Audit Market. Prepared for Department of Trade and Industry and Financial Reporting Council. Oxford: Oxera Consulting Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Palmrose, Zoe-Vonna. 1986. The effect of nonaudit services on the pricing of audit services: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 24: 405–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunandan, Kannan, and Dasaratha Rama. 2006. Sox section 404 material weakness disclosures and audit fees. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 25: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmayne, Nives Botica, Michael E. Bradbury, and Steven F. Cahan. 2010. The effect of political visibility on audit effort and audit pricing. Accounting and Finance 50: 921–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittenberg, Larry E., Karla Johnstone, and Audrey Gramling. 2012. Auditing, 8th ed. Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Terry, and Robert Simmons. 2014. Gate-sharing and talent distribution in the English football league. International Journal of the Economics of Business 21: 413–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barbadillo, Emiliano. 2016. Regulación frente a reputación como medio de salvaguarda de la independencia del auditor [Regulation versus reputation as a means of safeguarding the independence of the audit]. Revista de Contabilidad y Tributación 401–402: 161–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz-Barbadillo, Emiliano, and Nieves Gómez-Aguilar. 2007. Análisis empírico de los factores que explican la mejora de opinión de auditoría: compra de opinión y mejora en las prácticas contables de la empresa [An empirical analysis of the factors explaining the change in audit opinion: opinion shopping and accounting practices improvements in firms]. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting 36: 317–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, Fazlina Mohd, and Elizabeth Carson. 2009. The impact of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act on the audit fees of Australian listed firms. The International Journal of Auditing 13: 127–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, David, Anu Realo, Martin Voracek, and Jüri Allik. 2009. Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in big five personality traits across 55 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94: 168–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seetharaman, Ananth, Ferdinand A. Gul, and Stephen G. Lynn. 2002. Litigation risk and audit fees: evidence from UK firms cross-listed on US markets. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33: 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Rosana Cristina, Felipe Silva Moreira, José Emerson Firmino, Jaspe Padilha Miranda, and José Dionísio Gómez Silva. 2016. Julgamento dos Auditores Independentes sobre o Ativo Intangível: Um estudo sobre a qualidade da auditoria em clubes de futebol do Brasil [Judgment of independent auditors regarding intangible assets: A study on audit quality in Brazillian football clubs]. Revista Contabilidade e Controladoria 8: 65–88. Available online: http://revistas.ufpr.br/rcc/article/view/39449 (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- Simunic, Dan A. 1980. The pricing of audit services: Theory and evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 18: 161–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunic, Dan A. 1984. Auditing, Consulting, and Auditor Independence. Journal of Accounting Research 22: 679–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunic, Dan A., and Michael T. Stein. 1996. Impact of litigation risk on audit pricing: A review of the economics and the evidence. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 15: 119–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbanes Oxley-SOX. 2002. Committee on Financial Services, Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Available online: http://www.sarbanes-oxley.com (accessed on 23 February 2018).

- Stanley, Jonathan D. 2011. Is the audit fee disclosure a leading indicator of clients’ business risk? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 30: 157–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Michael. T., Dan A. Simunic, and Terrence B. O’Keefe. 1994. Industry differences in the production of audit services. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 13: 128–42. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, Rasmus K., and Klaus Nielsen. 2012. Soft budget constraints in professional football. European Sport Management Quarterly 12: 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgren, Stefan, and Tobias Svanström. 2014. Auditor-in-charge characteristics and going concern reporting. Contemporary Accounting Research 31: 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UEFA. 2010. UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations, Edition 2010 ed. Nyon: UEFA. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman, Ramgopal, Joseph P. Weber, and Michael Willenborg. 2008. Litigation risk, audit quality, and audit fees: Evidence from initial public offerings. The Accounting Review 83: 1315–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieru, Markku, and Hannu Shadewitz. 2010. Impact of IFRS transition on audit and non-audit fees: Evidence from small and medium-sized listed companies in Finland. The Finnish Journal of Business Economics 1: 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuequan, and Andy C.W. Chui. 2015. Product market competition and audit fees. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 34: 139–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, John, and Mark McNaughton. 2007. Gender differences in risk aversion and expected retirement benefits. Financial Analysts Journal 63: 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whisenant, Scott, Srinivasan Sankaraguruswamy, and Kannan Raghunandan. 2003. Evidence on the Joint Determination of Audit and Non-Audit Fees. Journal of Accounting Research 41: 721–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Robert, Daniel Plumley, and Girish Ramchandani. 2013. The relationship between ownership structure and club performance in the English Premier League. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 3: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Yang, Elizabeth Carson, Neil Fargher, and Liwei Jiang. 2013. Responses by Australian auditors to the global financial crisis. Accounting and Finance 53: 301–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Tianshu, and Jun Huang. 2013. The risk premium of audit fee: Evidence from the 2008 financial crisis. China Journal of Accounting Studies 1: 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).