2.1. The Impact of Trade Policies on Commodity Futures

As a core tool for regulating the global supply and demand pattern of commodities, trade policy shifts have a profound impact on the commodity futures market through channels such as tariff adjustments and policy uncertainties. In particular, in the context of trade frictions among major countries, this influence is characterized by rapid transmission, wide coverage, and complex fluctuation patterns (

Brander et al., 2023). Existing research has conducted multi-dimensional explorations of the interactive relationship between trade policy shocks and the commodity futures market, forming a relatively robust theoretical and empirical foundation.

While extensive literature focuses on commodity futures, it is crucial to recognize that trade policy shocks transmit risks across asset classes, including spot equity markets. Ref. (

Akhtaruzzaman et al., 2025) investigated the impact of the U.S. ‘reciprocal tariff’ announcement in April 2025 and found strong evidence of financial contagion among the U.S. and its top 20 trading partners. Their study highlights that while the U.S. stock market exhibited positive cumulative abnormal returns (

) due to protectionist optimism, trading partners—especially those with deep financial ties, like China—suffered significant negative abnormal returns. This suggests that the tariff shock was a systemic event, triggering simultaneous stress in both global equity spot markets and, as this study examines, commodity futures markets.

From the overall impact of macro-trade policy shocks, the policy uncertainty triggered by trade frictions is the key factor driving fluctuations in the commodity futures market. Ref. (

Fetzer & Schwarz, 2020) pointed out in their analysis of the 2018 Sino–U.S. trade conflict that targeted tariff measures between major countries disrupted the long-established equilibrium in commodity trade, directly raising market concerns over supply chain stability and, subsequently, transmitting to the futures market to intensify price volatility. This conclusion was empirically supported by Ref. (

Frazier & Sonka, 2019), which, in an early assessment of the impact of the Sino–U.S. trade conflict on the global soybean market, found that the U.S. tariffs on Chinese soybeans and China’s countermeasures significantly altered expectations of soybean supply and demand, leading to a significant jump in the volatility of soybean futures prices on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) and the Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE) before and after policy announcements, with the persistence of volatility also significantly enhanced. Ref. (

Feng et al., 2021) further expanded the boundary of the impact of policy uncertainty. They found that trade policy uncertainty not only directly affects futures price levels but also indirectly amplifies market volatility by changing investor risk preferences. This mechanism is particularly prominent in the agricultural futures market (

IndexBox, 2025), due to the fixed production cycle and low supply and demand elasticity of agricultural products, the expectation deviation brought about by policy shocks is difficult to digest through short-term capacity adjustments, thereby prolonging the duration of futures market volatility.

Among specific commodity categories, soybeans, as the core subject of the Sino–U.S. trade friction, have drawn significant attention to the reaction of their futures markets to trade policies. Ref. (

Guo et al., 2022) taking soybean, soybean oil, and soybean meal futures as the research objects, found that during the Sino–U.S. trade friction, the linkage between the futures markets of the two countries underwent significant changes: before the tariff adjustment, the U.S. soybean futures had a clear guiding effect on the prices of related futures in China; however, as the trade policy shock intensified, China’s independent pricing power increased, and the cross-market price transmission efficiency declined. Essentially, this change was an adaptive adjustment of the market after the trade policy disrupted the original supply and demand chain. Ref. (

Y. Wang et al., 2023) further quantified the extent of the impact of the trade war. Their results showed that the volatility of China’s agricultural futures market increased by more than 30% during the Sino–U.S. trade friction compared to the policy stable period. Among them, soybean futures, due to their high trade dependence, had a significantly higher volatility increase than other categories. In terms of the volatility spillover effect, the empirical analysis by Ref. (

Y. Wang et al., 2023) indicated that the trade policy shock not only intensified the volatility spillover within the soybean futures markets of China and the U.S. but also affected the futures of downstream products such as soybean oil and soybean meal through the industrial chain correlation effect, forming a cross-commodity and cross-market volatility transmission network.

The impact of trade policies on the commodity futures market also exhibits significant asymmetric characteristics and structural differences. Cross-country research by Ref. (

Fatima et al., 2019) found that negative trade policy shocks have a significantly greater impact on the volatility of commodity futures than positive shocks. This asymmetric effect stems from the market’s aversion to risk—investors are more sensitive to the escalation of trade barriers, which can easily trigger panic trading behavior. In the soybean futures market, this asymmetry is even more pronounced. Ref. (

Yang et al., 2025) pointed out that the phased escalation of U.S. tariffs on Chinese soybeans not only directly pushed up the import cost premium of Chinese soybean futures but also led to a restructuring of the global soybean trade pattern as China sought alternative supply sources from Brazil and others, thereby causing a divergence in the price correlation of soybean futures from different production areas. Additionally, Ref. (

Goodwin et al., 2005) noted the impact of trade policies is not one-dimensional; its effects are also modulated by factors such as the intensity of policy implementation, consistency of market expectations, and availability of substitute goods. For instance, when there are clear alternative supply channels in the market, the impact of tariff policies on futures prices will be significantly weakened.

In recent years, high-level trade conflicts have emerged between China and the United States, significantly impacting the global economy (

Zeng et al., 2022). Under these bilateral trade frictions, numerous disputes have also arisen in the agricultural commodity market. Chinese soybeans have become a key commodity in cross-Pacific commercial wars (

Wise & Chonn Ching, 2017).

The foundation of China–U.S. trade frictions originated from the transformation of the economic relationship between the two countries. The United States has dominated the global economy for many years (

Kagan, 2013). In 2001, when China was admitted to the WTO, it suddenly rose to the status of a commercial superpower, and this economic rise profoundly altered its relationship with the United States (

Deng & Moore, 2004). In 2018, China already dominated as the United States’ first merchandise trading partner, the third-largest export partner, and the largest import source (

FAOSTAT, 2025). Such an exponential expansion simultaneously created complex trade deficits and policy differences that ultimately led to a stage of strategic confrontation.

The initial stages of the U.S.–China trade policy shock were felt in early 2025. The first stage of this round of the trade policy shock began on 1 February 2025, when President Trump announced the imposition of a 10% tariff on Chinese products (

Husch Blackwell LLP, 2025), a move he later promised would be followed by a further increase to 20%. In turn, China announced similar tariffs on American soybeans (

P.R. China B.C., 2025). This was a significant retaliation. Soybeans are a significant commodity in both countries’ bilateral trade. As the two top producers of soybeans, the U.S. agriculture-dependent exporting economy suffered significant harm due to China’s reciprocal retaliation. Reciprocal tariffs altered the built-in supply-and-demand dynamics between the world’s two largest economies.

As of 4 March 2025, a state of siege raged between trade partners. On 4 March, U.S. tariffs increased again by 20% (

Husch Blackwell LLP, 2025); China also adjusted its tariff system on soybean exports, from 10% to 15%. These actions were steps in a complex trade negotiation process, but not autonomous trade choices. The resulting counter-trade and counter-tariff decisions adopted by the U.S. and China reflected various domestic concerns, including trade balance adjustment and the defense of strategic sectors, as well as concerns for China’s macroeconomic stability and the interests of Chinese farmers and their strategic industries, which carry high political stakes. These increased tariffs underscore that these countries sought to maintain their economic sovereignty, notwithstanding the processes and obligations of international trade.

It began to rise to its peak level right after 9 April 2025, when the United States imposed tariffs on many Chinese goods at a rate of 145%. Following this, the Chinese government adopted a reciprocal response by adjusting tariffs on soybeans from 45% to 125% (

P.R. China B.C., 2025), which was significantly higher than the previous tariffs and indicated a further escalation of the trade policy shock between the U.S. and China. Hence, both the American and Chinese soybean markets faced huge changes in the trade policy. A U.S. farmer was overwhelmed by the dramatic supply–demand disequilibrium, where the dominant customer disappeared. They became immediately burdened by falling commodity market prices and unsold inventories, which became unmanageable within just a few months, resulting in a 40% decline (

IndexBox, 2025). At the same time, Chinese traders expanded domestic production programs and expedited diversification by consolidating long-term contract relationships with major export sources in Brazil and Argentina (

Dos Reis et al., 2025). This latter maneuver’s transformative effect was to alter not just the geography of commodity flows, but also the existing commodity trade arteries in a restructuring of global trade.

2.3. GARCH, EGARCH, and DGARCH Models Application

In time series linear regression, GARCH, DGARCH, and EGARCH models each have irreplaceable advantages. The GARCH model (

Lundbergh & Teräsvirta, 2002), as the fundamental framework for conditional heteroskedasticity modeling, has the core advantage of being able to capture volatility clustering concisely and efficiently. By expressing the conditional variance as a linear combination of lagged squared residuals and lagged conditional variances, it accurately depicts the pattern of alternating high and low volatility periods in financial time series. Moreover, the model is simple to specify, with parameters having intuitive economic meanings (such as the ARCH term coefficient reflecting the impact of current shocks on volatility, and the GARCH term coefficient reflecting the persistence of volatility), and has strong estimation stability, making it suitable as a benchmark model for analyzing volatility dynamics. The DGARCH model’s (

Caporin & McAleer, 2006) prominent advantage lies in introducing a discrete indicator function on the basis of GARCH, which can directly identify and quantify the leverage effect in volatility asymmetry by setting a regulating term that only takes effect when negative shocks occur. This clearly distinguishes the differential impact of negative shocks and positive shocks on volatility. Its asymmetric term parameter can intuitively determine whether negative shocks extraordinarily amplify volatility, without the need for complex function transformations, making it suitable for scenarios where the existence of asymmetry needs to be qualitatively verified.

The tariff policy shift in the 2025 U.S.–China soybean tariff conflict made its marginal impact on futures market volatility far exceed that of conventional variables such as South American climate, the USD/CNY exchange rate, and global oil prices, thereby naturally reducing interference from other factors. In terms of the extent of influence, existing literature has verified that the explanatory power of extreme trade policies for soybean futures volatility (

about 38.6821%) is significantly higher than that of climate factors (

about 7.4934%), exchange rate fluctuations (

about 4.3972%), and oil price changes (

about 5.3799%) (

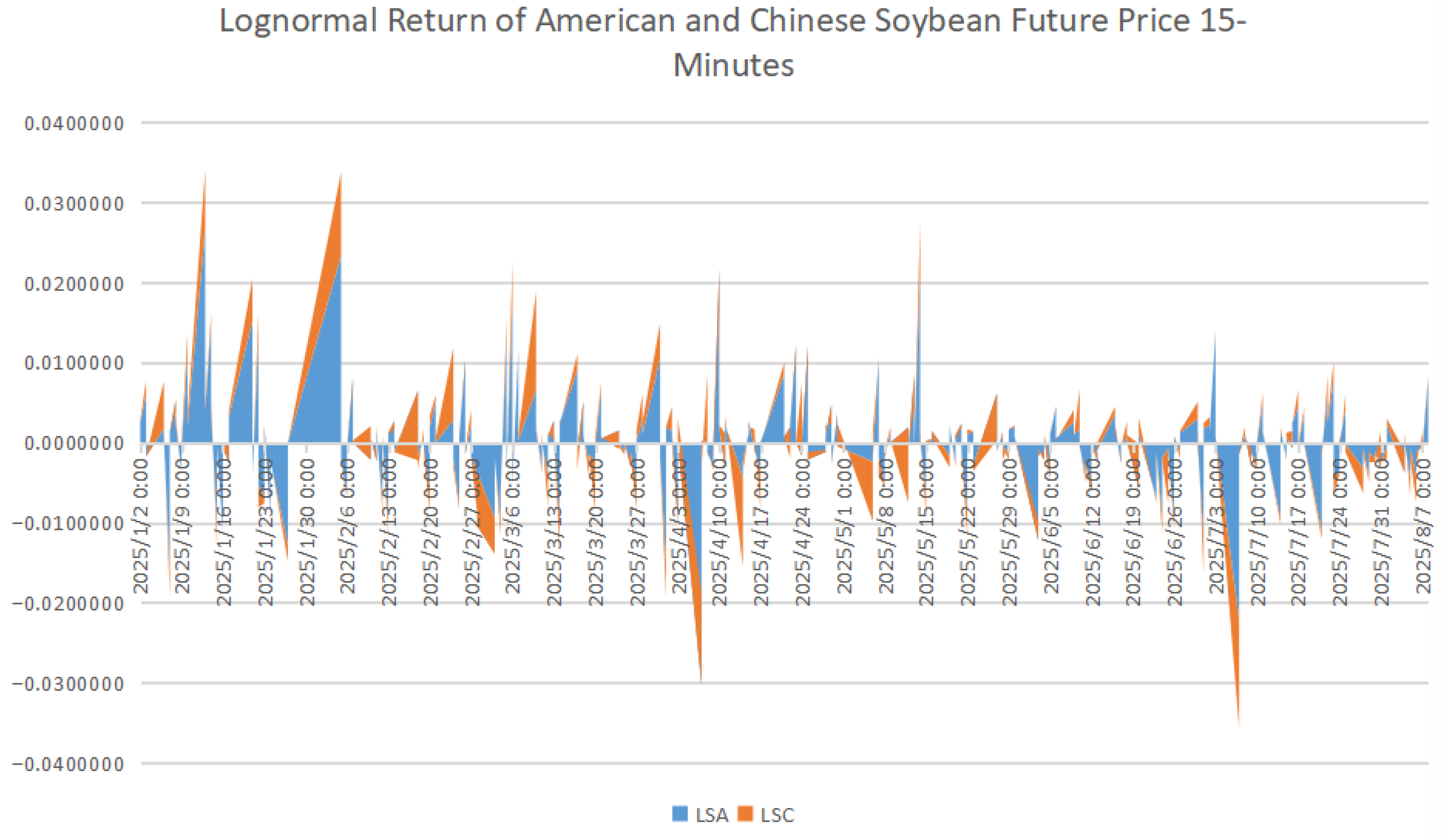

Frazier & Sonka, 2019). Specifically, in the sample of this study, on 9 April 2025 (the date of the third stage tariff announcement), the standard deviation of the logarithmic return rate of China’s DCE soybean futures reached 0.1863 (

Table 2), which was five to nine times higher than the impact of the precipitation anomaly rate in the main soybean production areas of Brazil (±5%, within the normal fluctuation range), the USD/CNY exchange rate volatility (2.1%), and the WTI crude oil price volatility (3.2%).

It is worth noting that the current mainstream volatility modeling tools (DGARCH and EGARCH) still have significant limitations in characterizing the regulatory effects of trade policies. For the DGARCH model (represented by GJR-GARCH), its core limitation lies in its reliance on a discrete indicator function to distinguish the direction of shocks, which can only qualitatively determine whether negative shocks amplify volatility, but cannot quantify the marginal impact of the intensity gradient of trade policies (such as tariffs rising from 15% to 125%) on asymmetry, and it is difficult to capture the dynamic evolution characteristics of volatility asymmetry during the implementation of policies (

Caporin & McAleer, 2006). While the EGARCH model can quantify the difference in shocks through a continuous asymmetric term, it is difficult to effectively separate the independent contributions of various factors when dealing with the superimposed shocks of trade policies and other macro variables (such as exchange rates, global supply and demand), and it is prone to parameter estimation bias caused by multicollinearity. At the same time, in 15-min high-frequency data, the EGARCH model has a relatively weak ability to resist market microstructure noise (such as liquidity fluctuations, changes in transaction costs), and may mistakenly regard noise as volatility caused by policy shock (

Lundbergh & Teräsvirta, 2002).

As a core tool for capturing the asymmetric characteristics of financial time series volatility, the EGARCH (Exponential GARCH) model, since its proposal by (

Nelson, 1991), has demonstrated strong adaptability in research on commodity futures markets under trade policy shocks. Compared with the traditional GARCH model, its key breakthrough lies in taking the natural logarithm of the conditional variance. This approach not only circumvents the non-negative constraint of variance but also directly quantifies the differential impact of positive and negative shocks on volatility through the asymmetric term, providing a rigorous econometric framework for analyzing the nonlinear transmission of policy shocks.