Abstract

The constant evolution of Decentralized Finance (DeFi) calls for the continuous monitoring of its developments and implications through a critical review of the academic literature. While DeFi holds promise for enhancing economic activity by expanding market access for enterprises and promoting financial inclusion, concerns remain that digital assets are primarily used for speculative purposes rather than for financing the real economy. This study employs bibliometric methods to investigate whether and how the current academic literature addresses the potential influence of DeFi on real economic dynamics. Employing bibliometric methods—including co-citation, bibliographic coupling, and keyword co-occurrence analyses—focused on DeFi-related publications in the Economics and Business subject areas within the Scopus database, the study maps the knowledge base, author networks, and thematic trends and their temporal evolution, supporting regulators, researchers, and practitioners. The findings reveal that the integration of DeFi with the real economy has received limited attention in scholarly research. This highlights the need for further investigation into DeFi’s implications for financial stability, productive investment, and long-term economic growth.

1. Introduction

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) stands out currently as one of the most prominent topics of discussion (Zetzsche et al., 2020). As of 2 July 2024, the DeFi sector holds a significant position in the financial ecosystem, with a total value locked (TVL) of USD 249.99 billion, according to CoinMarketCap. This substantial figure underscores DeFi’s growing influence and its potential to reshape traditional financial systems. DeFi represents an alternative financial structure (Schär, 2021; Schwiderowski et al., 2023) that enables the democratization of finance (Herrmann & Masawi, 2022; Makarov & Schoar, 2022), thereby enhancing financial inclusion for the general public (Allen et al., 2022; Grassi et al., 2022; Schär, 2021). It is attracting the interest of many stakeholders such as companies, professionals, researchers, and even common citizens eager to benefit from the proposed ecosystems (El Haddaoui et al., 2023). Based on blockchain and smart contracts, DeFi offers efficiency, transparency, accessibility, and security (Gramlich et al., 2023; Schär, 2021), reducing the risk of manipulation and granting greater control to the parties involved in contracts (Andolfatto & Martin, 2022; Chiu et al., 2022; Schär, 2021). The cost reduction in transactions enables low-cost access to capital and fosters the creation of new business and a new landscape for entrepreneurship (Andolfatto & Martin, 2022; Chen & Bellavitis, 2020; Makarov & Schoar, 2022).

While the broader cryptocurrency market has garnered considerable academic attention, research specifically focused on DeFi remains relatively scarce (Corbet et al., 2021). This gap is, to some extent, understandable given the relatively recent emergence of DeFi as a distinct concept. However, recent years have witnessed a growing scholarly interest and more in-depth investigation into this rapidly evolving domain. The dynamic and constantly shifting nature of DeFi (Alamsyah et al., 2024) underscores the need for updated bibliometric analyses that map the progression of the field (Xu et al., 2024). Such efforts are essential to identify emerging trends, avoid redundant research, and support more coherent and cumulative knowledge development in DeFi studies.

Some previous studies have explored DeFi research with general reviews (Beinke et al., 2024; Chen & Bellavitis, 2020; Eikmanns et al., 2023; Popescu, 2020; Puschmann & Huang-Sui, 2024; Schär, 2021; Zetzsche et al., 2020), systematic literature reviews (Gramlich et al., 2023; Meyer et al., 2022; Szrajber et al., 2025), or bibliometric analyses (Aydaner & Okuyan, 2024; Batra et al., 2024). None of these previous analyses adopt a specific focus on the Business and Economics research fields.

DeFi research is grounded in several academic disciplines, including management, Economics, and Computer Science (Xu et al., 2024). While technological, market, and Business model aspects of DeFi have received considerable attention (Beinke et al., 2024; Chen & Bellavitis, 2020), relatively little research has explored the intersection between traditional finance (TradFi) and DeFi (Puschmann & Huang-Sui, 2024). The connections between DeFi, TradFi, and the broader real economy remain underexplored and warrant deeper investigation by academic research (Aquilina et al., 2024). Furthermore, the rapid expansion of DeFi is driving significant economic and social transformations (Bennett et al., 2023). In light of these dynamics, this study focuses specifically on scientific contributions within the Business and Economics domains, given the economic impact that DeFi can have on the real economy, and deliberately excludes other areas—such as Computer Science—that, while substantial in volume, fall outside the scope of this analysis. In this study, the “real economy” refers to economic activities involving production, consumption, entrepreneurship, and employment as distinct from speculative or purely financial transactions (Bezemer & Hudson, 2016; Borio & Zhu, 2012). This real economy concept can also be articulated under three specific and highly interrelated dimensions (Becha et al., 2025): the output (economic growth), the driver (the financial system, including financial inclusion and core functions of financial activity, namely lending, saving, and payments), and the guiding principles (sustainability).

This study aims to make a meaningful contribution by mapping the knowledge foundations, current research landscape, and potential future directions of DeFi within the Business and Economics domains, trying to discern whether current academic research in these areas is paying attention to the contribution of DeFi to the real economy. Using the bibliometric analysis of publications indexed in the Scopus database, it examines the relationships among authors, articles, and keywords to uncover the structural and thematic dynamics of the field. By highlighting research patterns and reducing the duplication of effort, the study seeks to support more efficient and cumulative knowledge development. Notably, this is the first bibliometric review specifically focused on DeFi within Business and Economics, underscoring the novelty of the topic in these disciplines. The findings provide valuable insights into the evolution of DeFi research, revealing emerging trends and guiding future academic inquiry and collaboration. Furthermore, they offer a comprehensive and contextualized view of how DeFi is being integrated into the broader scholarly discourse in these fields. The results are invaluable for regulators to understand and create new legislation that protects consumers without hindering the acceptance or evolution of DeFi technology. For researchers, the findings highlight potential collaborators, new emerging trends, and create new lines of research. For practitioners, the analysis helps to find specialized advisors to build diversified portfolios and explore new investment opportunities.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 presents a concise review of the existing literature on DeFi. Section 3 outlines the methodology employed to examine the DeFi research landscape within the Economics and Business subject areas. Section 4 discusses the main findings of the bibliometric analysis. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study by highlighting its limitations and proposing directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

DeFi represents an innovative approach to conducting business, offering an alternative financial structure to the existing traditional systems (Cevik et al., 2022; Makarov & Schoar, 2022; Metelski & Sobieraj, 2022; Schär, 2021; Wronka, 2021). At least theoretically, DeFi presents multiple benefits, including decentralization (Eikmanns et al., 2023), transparency, financial inclusion, self-sovereignty of users, and lower transaction costs (Chen & Bellavitis, 2020; Gramlich et al., 2023; Makarov & Schoar, 2022; Pelagidis & Kostika, 2022; Smith, 2021). Through DeFi, untrusted parties can engage in transactions without the need for intermediaries, thereby reducing costs and gaining greater control over agreement terms (Andolfatto & Martin, 2022; Herrmann & Masawi, 2022). This cost reduction could open up financial access to a significant portion of the population previously excluded, fostering the creation of new Business models (Chen & Bellavitis, 2020; Pelagidis & Kostika, 2022).

2.1. DeFi Main Features

Decentralization, efficiency, investors’ behavior, and risk diversification are some of the main elements sustaining the DeFi ecosystem. The academic literature has highlighted both the great potential of these features to drive a transformation of TradFi, as well as the doubts and limitations about them that could hinder their impact on the real economy sphere. A short revision of the main contributions regarding each one of these DeFi central elements will facilitate the understanding of the results of the bibliometric analyses to be conducted.

Decentralization is a central focus within DeFi. Decentralizing governance ensures that no single entity has exclusive control over the markets or services it offers (Grassi et al., 2022). Within DeFi, Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) exist, governed by rules written in code that enable automated decisions (Axelsen et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022). Although cryptocurrency users value the right to vote more than the token value (Makridis et al., 2023), few exercise their voting rights (Barbereau et al., 2023), primarily using tokens for speculation (Chu et al., 2023; Ghosh et al., 2023). Makridis et al. (2023) indicate a sustained loss of investor interest in Decentralized Exchanges (DEXs) in favor of Centralized Exchanges (CEXs), which offer convenience, liquidity, and security over the anonymity of the DEX (Aspris et al., 2021; Makridis et al., 2023). Furthermore, oligarchic tendencies challenge the idea of truly decentralized systems (Bongini et al., 2025), and the growing concentration of cryptocurrencies among wealthy economic agents may be giving disproportionate economic and political influence to a small elite (Tommerdahl, 2025). Thus, real decentralization has been questioned and even considered ultimately untenable (Aquilina et al., 2024). Additionally, despite DeFi promising disintermediation, decentralization implies high participation costs and unique crypto market risks that have led to an increase in intermediation (Grassi et al., 2022; Milkau, 2023). Thorough research and due diligence are needed to mitigate information asymmetry and technological vulnerabilities (Cumming et al., 2019; Momtaz, 2024).

Another important area of investigation revolves around the degree of efficiency of the DeFi market (Chowdhury et al., 2023; Kliber, 2022; Wang, 2022; Yousaf & Yarovaya, 2022a, 2022b; Zhou, 2023). Ghosh et al. (2023) assert that Non-Fungible Tokens (NFT) and assets in DeFi are predictable, suggesting complete inefficiency in these markets. Crypto-asset investors, unlike traditional ones, are technology-driven and display herding behavior and anchoring bias, contributing to market inefficiencies and speculative bubbles (Benedetti & Kostovetsky, 2021; Bongini et al., 2025; Maouchi et al., 2022).

There has also been great interest in studying investor behavior in DeFi. Investors in the DeFi market consistently exhibit herd behavior, indicating a continuous high dependency on events (Chowdhury et al., 2023; Chu et al., 2023; Yousaf & Yarovaya, 2022a). This herd behavior may stem from the lack of professionalism among DeFi investors, who prioritize high returns over accurate asset valuations within DeFi (Kreppmeier & Laschinger, 2023; Metelski & Sobieraj, 2022). Research has also explored how consumer sentiment influences DeFi markets (El Haddaoui et al., 2023; Hassan et al., 2021; Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2022, 2023). A gender participation gap has also been found in the cryptocurrency market (Alonso et al., 2023).

Another critical aspect within the DeFi market is the interconnectedness, relationships, hedging, diversification, or safe-haven capabilities provided by DeFi assets. It has been observed that DeFi assets move collectively, with greater co-movement detected within DEXs compared to CEXs, particularly during bearish market periods (Kumar et al., 2023; Park et al., 2023). Regarding the relationships or interconnectedness of DeFi assets with other assets, connection with NFTs is the most controversial. Several authors have indicated that NFTs are decoupled assets that provide good hedge and diversification in the DeFi and cryptocurrency markets (Abakah et al., 2023; Goodell et al., 2023; Yousaf & Yarovaya, 2022a, 2022b). Stablecoins (Gadi & Sicilia, 2022), altcoins, and meme coins (Li et al., 2023) have been found to be effective hedging instruments against cryptocurrencies, and DeFi would indeed function as a diversifier in portfolios consisting of traditional assets and NFTs (Abakah et al., 2023; Ghosh et al., 2023; Yousaf et al., 2023). The safe-haven capacity has been studied by several authors, concluding that DeFi and NFTs serve as safe havens during financial/geopolitical turmoil (Polat, 2023; Umar et al., 2022), similar to centralized Stablecoins (Kliber, 2022).

2.2. DeFi Challenges

DeFi also entails risks, vulnerabilities, and challenges (Wronka, 2021). The decentralized nature of DeFi, coupled with its global user base, presents significant complexities in navigating regulatory frameworks. It is difficult to determine legal jurisdiction and applicable regulations (Zetzsche et al., 2020). Furthermore, varying regulatory stances, even inside the same countries, among jurisdictions exacerbate the ambiguity surrounding DeFi assets’ treatment (Smith, 2021). The decentralized structure of DeFi platforms also fosters opportunities for fraudulent and without ethics activities and tax evasion, as many platforms operate without mandatory KYC (Know your Customer) or AML (Anti-Money Laundering) requirements (Kaur et al., 2023; Makarov & Schoar, 2022; Smith, 2021). Moreover, legislative uncertainties pose a threat, as overly stringent regulations could stifle innovation and force compliance-challenged platforms to shut down (Gramlich et al., 2023; Kaur et al., 2023). Market challenges include susceptibility to black swan events, scalability limitations leading to transaction congestion and high costs, and credit or counterparty risks associated with borrowing and lending within DeFi (Gramlich et al., 2023; Jensen et al., 2021; Kaur et al., 2023; Schuler et al., 2023). Various solutions have been proposed to prevent fraud and illicit activity (Makarov & Schoar, 2022), and efforts are also being made to address network congestion and enable interoperability between different blockchains (Park et al., 2023).

Regarding security and privacy issues, there is the possibility of the loss of private keys, either due to user forgetfulness or external attacks (Jensen et al., 2021; Kaur et al., 2023). Additionally, since most applications are on the Ethereum network, there is systemic risk, as interconnectedness means that a failure in one can lead to a failure in the entire network (Jensen et al., 2021; Kaur et al., 2023; Park et al., 2023). Another controversial issue is environmental impact. The blockchain’s energy-intensive protocols contribute to environmental concerns due to high electricity consumption and CO2 emissions (D. Zhang et al., 2023). Transitioning from energy-intensive protocols (like Proof of Work) to less intensive ones (like Proof of Stake) would help decarbonize cryptocurrencies (Kaur et al., 2023; D. Zhang et al., 2023).

2.3. Impact of DeFi on the Real Economy

The impact of DeFi developments on the real economy seems to be significantly underexplored in the academic literature. As shown in the previous paragraphs, much of the existing research focuses on techno-financial aspects of the DeFi ecosystem—such as market efficiency, volatility, return correlations, and asset co-movement—treating DeFi primarily as an emergent financial market rather than as a transformative infrastructure for economic systems (Alamsyah et al., 2024; Benedetti & Kostovetsky, 2021). These studies often overlook the ways in which DeFi could affect core economic functions, including credit intermediation, entrepreneurship, and financial inclusion.

Some emerging studies have begun to explore the potential of DeFi to drive broader societal and economic changes. Harir and Bel Mkaddem (2024) show that increases in DeFi’s TVL are significantly associated with a long-run decline in global bank deposits, suggesting a modest but measurable displacement effect on traditional financial institutions. Shyamaladevi et al. (2025) emphasize how DeFi can restructure financial ecosystems, particularly through blockchain-driven transparency and decentralized governance models. Musungwini and Furusa (2024) propose a framework for implementing DeFi to improve financial inclusion in developing economies, focusing on the unbanked population in Zimbabwe. Similarly, Aggarwal (2024) investigates how DeFi mechanisms can support entrepreneurial financing, while S. R. Ali et al. (2024) and Archana and Gloth (2024) explore the intersection between the blockchain, entrepreneurship, and innovation.

2.4. Previous DeFi Literature Reviews

Previous reviews about DeFi are rather descriptive and focused on the conceptualization of DeFi as a new field and the specification of DeFi taxonomies (Beinke et al., 2024; Chen & Bellavitis, 2020; Eikmanns et al., 2023; Popescu, 2020; Puschmann & Huang-Sui, 2024; Schär, 2021; Zetzsche et al., 2020). Popescu (2020), for instance, analyzed multiple studies on DeFi, highlighting its characteristics and subcategories, and providing a synthesis of how this ecosystem evolves and reshapes modern financial structures. Chen and Bellavitis (2020) perform a literature review to assess the benefits, challenges, and limitations of DeFi. More recently, Eikmanns et al. (2023) present DeFi not just as a collection of financial tools but as a complex, evolving technological ecosystem requiring specialized, interdisciplinary platform analysis. Puschmann and Huang-Sui (2024), under an innovative approach, applied a conceptual-to-empirical and empirical-to-conceptual approach, combining a literature review and data about 278 start-ups to construct a taxonomy of DeFi.

There have also been some systematic literature reviews (SLRs) and bibliometric analyses published on DeFi. Meyer et al. (2022), Gramlich et al. (2023), and Szrajber et al. (2025) analyze the DeFi literature through SLRs, trying to identify new avenues of research. Among the bibliometric analyses, Aydaner and Okuyan (2024) investigate the growth, geographical distribution, collaboration patterns, and main thematic trends in DeFi research, comparing results from Scopus and WoS, while Batra et al. (2024) conducted a bibliometric study focused on smart contracts within the DeFi ecosystem.

None of these previous studies have put a specific focus on the Business and Economics domains. A bibliometric analysis of DeFi within the fields of Business and Economics could help to identify emerging trends and guide future research toward its economic and societal implications. Moreover, current research faces several key limitations that constrain a comprehensive understanding of the potential of DeFi in the Business and Economics areas. First, the present boom may lead to redundant studies, impeding meaningful progress. Second, the diversity of research approaches necessitates identifying patterns and themes to clarify the starting point and direction of inquiry. Additionally, recognizing key authors of DeFi research is vital for fostering direct collaborations and detecting indirect connections through bibliometric analysis.

Given the recent surge in interest in Business and Economics within the DeFi research domain, where a bigger integration between DeFi and the real economy could be expected, this study complements previous literature reviews and bibliometric analyses to offer a detailed idea of the DeFi research front in these areas, unveil the latent relationships in the data, and reach some conclusions about how the academic literature is approaching the role of DeFi in supporting economic activities.

3. Method and Sample Description

3.1. Method

To conduct the bibliometric analysis of DeFi academic research on the Business and Economics areas, an initial search is performed in Scopus, applying a set of filters and a direct review of contents to only retain the relevant literature. Once a final sample of academic references was configured, the bibliometric data was cleaned in order to be adequately processed in the chosen software. Co-citation of references and authors is intended to delineate the knowledge base of DeFi in the Business and Economics fields, while the bibliographic coupling of articles and sources and the analysis of keyword co-occurrence are aimed at establishing its research front.

3.1.1. Selection of the Database and Initial Search

Although there is a big gray literature on DeFi, including non-academic whitepapers, unpublished papers on SSRN, or non-peer-reviewed contributions in arXiv, this study focuses on academic research. Since DeFi research is still evolving, it is crucial to establish its academic foundation through peer-reviewed contributions. Relying on high-quality academic sources helps to identify the most influential theoretical and empirical advancements that drive future research rather than transient industry trends or speculative discussions. To conduct the bibliometric analysis, the Scopus database was employed. Aydaner and Okuyan (2024) found that the Scopus database contains a much richer and more extensive range of publications on DeFi compared to the Web of Science (WoS) database. As acknowledged by Levine-Clark and Gil (2008), Scopus stands out as a more robust database than WoS for the area of Economics and Business. This is due to Scopus indexing approximately 8000 more journals than WoS, resulting in slightly more citations (Aghaei Chadegani et al., 2013; Levine-Clark & Gil, 2008; Martín-Martín et al., 2018) and covering niche research areas that might not be adequately represented in WoS (Zupic & Čater, 2015). An additional benefit of Scopus is that it incorporates comprehensive data for all authors cited in references, thereby improving the precision of author-based citation and co-citation analysis (Aghaei Chadegani et al., 2013; Zupic & Čater, 2015). Additionally, Scopus offers extensive bibliographical information, including title, abstract, authors, keywords, cites, etc. (Aghaei Chadegani et al., 2013; Zupic & Čater, 2015). Furthermore, the data imported from Scopus is compatible with the commonly used bibliometric software packages (Zupic & Čater, 2015). The research has also prioritized reproducibility, which strengthens the reliability of the authors’ findings and effectively reduces the risk of possible subjective bias (Kraus et al., 2020) following the recommendations of Zupic and Čater (2015) to clean the data.

Data were collected from Scopus, encompassing the period from 2008 (publication of the Bitcoin white paper) to 12 November 2024. With the objective of conducting a literature search as openly as possible, and similarly to Puschmann and Huang-Sui (2024) or Aydaner and Okuyan (2024), the following search string was used in the title, abstract, and keywords: “DeFi” OR “Decentralized Finance”. By limiting the search to the foundational terms, the study ensures that the analyzed literature is centrally focused on the concept of DeFi itself. A broad search using specific related terms (e.g., “smart contracts,” “liquidity mining,” “DAO,” “yield farming,” and “flash loans”) risks including a high volume of noise that would dilute the analysis due to the presence of studies focused on these terms where DeFi is just a marginal sub-topic. The chosen general string provides a higher quality, lower-noise dataset essential for accurately mapping the core intellectual structure, key contributors, and thematic evolution of the formalized academic discourse on DeFi within the Business and Economics areas. This initial search retrieved 8252 publications.

3.1.2. Application of Filtering Criteria

Given that Scopus can classify contributions under more than one subject area, a cross-section analysis was conducted to verify that around 30% of the publications were uniquely classified under the Computer Science Subject area, 18% in Economics; Econometrics, and Finance; and 11% in Business, Management, and Accounting. To focus specifically on the Business and Economics areas, the results were filtered accordingly, resulting in 1.040 publications. Further refinement was made by including only articles, reducing the sample to 576 items. Finally, acknowledging the significant importance of English as a language for writing, publishing, and achieving broader global visibility (Duszak & Lewkowicz, 2008; Flowerdew & Li, 2009; López-Navarro et al., 2015), it was decided to filter the results by language, resulting in a final sample of 509 articles.

Then, a careful review of sample articles was conducted to verify their alignment with the research objective. Inclusion criteria required the articles to be relevant within the Business and Economics DeFi fields and accessible to allow comprehensive analysis. Many articles were found to be incorrectly included in the Scopus search due to typographical errors and the misclassification of indexed keywords. After this final refinement, the resulting sample comprised 215 articles. Accounting for the possible overlap between subject areas in Scopus, this final list of articles was checked to verify that only five contributions were simultaneously classified under the Economics, Business, and Computer Science Scopus subject areas, reinforcing the objective of making a substantial contribution to analyze the state of the art of DeFi in academic research more directly related to real economy.

3.1.3. Data Cleaning

The data cleaning process involved using a text file format and Microsoft Excel. Once the raw data were downloaded, the keywords were thoroughly reviewed to avoid semantic duplications and to merge all terms with equivalent meaning under a single label, ensuring their actual representativeness within the dataset. Without this adjustment, identical concepts written in different ways would have been treated as separate entities, distorting their real significance in the sample. Examples of terms that were standardized include “DeFis”, “Defi”, “DeFi”, “Decentralized Finance”, “Decentralized finance (DeFi)” merged under “DeFi”; “Distributed Ledger”, “DLT”, Distributed Ledger Technology” unified as “DLT”, or “Decentralized Autonomous Organization”, “DAO”, and “DAOs” grouped under “DAO”, among other words. This process ensured conceptual consistency and avoided duplicities. In addition, author names were carefully reviewed to correct potential typographical errors or inconsistencies in compound surnames, which could otherwise affect the accuracy of bibliometric analyses. This verification involved checking the authors’ ORCID profiles or institutional affiliations to control for the existence of different listed names referring to the same individual.

3.1.4. Bibliometric Analyses

Bibliometrics, through mathematical and statistical methods (Pritchard, 1969), enables the revelation of intellectual traditions within a field and the tracking of their evolution over time to identify opportunities and potential directions for future research (Kraus et al., 2022; Sauer & Seuring, 2023; Vogel & Güttel, 2013). The Vosviewer program (version 1.6.18) was used to subject the sample to comprehensive bibliometric analyses. These involved co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling analysis, and author keywords co-occurrence analysis. Co-citation analysis entails examining how often two publications have been cited together by a third document (Small, 1973; Üsdiken & Pasadeos, 1995). A higher frequency of such co-citations indicates a greater likelihood that these publications cover similar topics, enabling the identification of shared interests or objectives (Zupic & Čater, 2015). Moreover, co-citation analysis establishes the research bases of a field (López-Cabarcos et al., 2020; Zupic & Čater, 2015). Bibliographic coupling creates links between publications that share a common research approach (Jarneving, 2007; Peters et al., 1995). This method evaluates the extent of similarity in authors’ bibliographies (Kovács et al., 2015; Zupic & Čater, 2015). The distinction between co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling lies in the fact that bibliographic coupling examines the overlap in authors’ bibliographies, whereas co-citation focuses solely on the frequency with which two authors have been cited (Kovács et al., 2015; Zupic & Čater, 2015). In addition, bibliographic coupling indicates the current and future directions of a research domain (López-Cabarcos et al., 2020; Zupic & Čater, 2015). The author keywords co-occurrence analysis offers valuable insights into the prevalent themes that have been extensively studied in the context of DeFi (Zupic & Čater, 2015). This analysis exclusively employs author keywords due to their precise relevance regarding the content of each publication (Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2025; J. Zhang et al., 2016).

Setting the thresholds or minimum number of citations/occurrences is critical, because it directly controls the granularity and focus of the resulting clusters. An iterative testing process was applied, increasing the thresholds until the total number of nodes is manageable and the clusters are distinct enough to interpret.

3.2. Sample Description

Figure 1 shows the annual publications on DeFi in the database. The initial article in the database is from 2020, creating a gap between this year and the publication date of the Bitcoin white paper. This gap might be attributed to DeFi being in its early stages (Chen & Bellavitis, 2020; Zetzsche et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the figure illustrates a continuous rise in interest in DeFi, possibly driven by users seeking more decentralized, innovative, interoperable, borderless, and transparent financial alternatives (Zetzsche et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Number of articles per year. This Figure represent a bar chart depicting the annual number of publications on DeFi from 2020 to 2025, illustrating a consistent increase in research interest over the period.

In Table 1, Lotka’s law has been applied to examine the individual productivity of each author. Lotka’s law suggests that approximately 60% of authors will only produce one article. However, in this case, the data deviates from Lotka’s expectations, as nearly 90% of authors in the sample have contributed only once, exceeding the 60% threshold. On the other hand, authors who have made more than one contribution fall below the expected threshold (Lotka, 1926). This suggests that the field of DeFi is attracting great attention from both insiders and outsiders as a hot topic that can show interlinkages with many other lines of research in the Business and Economics subject areas. DeFi has thus been related to research on climate change (D. Zhang et al., 2023), financial crime (Wronka, 2021), accounting (Smith, 2021), social metrics (Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2023), risk analysis (Kaur et al., 2023), renewable energy (Goodell et al., 2023), and gender issues (Alonso et al., 2023).

Table 1.

Lotka law and authors per publication.

In alignment with the spirit of Lotka’s law, which delves into author productivity, it is found that 38.60% of the publications have between one or two authors, 59.07% of the publications have between three and five authors, and only 2.33% of the sample has more than six authors.

In Table 2, the top ten most cited articles are presented. The analysis of the most cited articles is important to know the foundational works in a discipline. Notably, two of the oldest articles are among them, which was expected given their longer time frame for accruing citations. The most cited article, with 366 citations, is Chen and Bellavitis (2020). This article, corresponding to the initial period of the sample, delves into the promises, explores major Business models, and outlines the limitations of DeFi. Schär (2021) is the second seminal work in the sample, providing a comprehensive analysis of DeFi’s infrastructure, applications, and potential implications, which has been instrumental for researchers and practitioners in understanding the complex architecture of DeFi. Another cornerstone for the DeFi knowledge base is Zetzsche et al. (2020), who focus on DeFi’s potential to disrupt traditional financial systems and the regulatory challenges it introduces, offering insights into how regulatory frameworks might evolve to address the unique challenges posed by DeFi. The rest of the articles explore the interconnectedness, market behavior, and financial implications of emerging digital assets—particularly DeFi tokens, NFTs, and cryptocurrencies—within broader financial systems. Yousaf stands out as one of the most prolific authors, with numerous publications that explore various aspects of these digital assets, particularly their interconnectedness with traditional financial markets and implications for portfolio management.

Table 2.

Most cited articles.

Upon delving deeper into Table 2, a certain concentration has been observed regarding the journals contributing to the research. Among the ten most cited articles, five belong to only two journals: Finance Research Letters and International Review of Financial Analysis. Hence, it was decided to apply Bradford’s law. Bradford’s law suggests that a few sources will be highly productive, generating approximately a third of all scientific contributions, while a larger number of sources will have a moderate production, and a vast number of sources will contribute minimally and decline over time. A total of 215 articles from the sample have been sourced from 116 journals. Given the novelty of the topic, it was determined that journals with 4 or more contributions would be classified as highly productive sources. Consequently, it was found that 10 journals contributed 76 articles, 23 journals contributed 56 articles, and the remaining 83 journals contributed the remaining 83 articles. These findings align with Bradford’s law, suggesting a core group of journals specializing in the topic, another set with frontier publications, and additional journals with sporadic contributions (Bradford, 1985).

4. Results and Discussion

Results from the co-citation, bibliographic coupling, and keyword co-occurrence analyses are shown in the following subsections, with the support of figures that share some common aspects. Each element under analysis is depicted by a label, with the size indicating the frequency of citation. A larger label means a higher frequency of citation. The proximity of the labels and the color of the clusters indicate the likelihood of being cited together. Closer labels are more likely to be cited together, and labels within the same cluster suggest a higher likelihood of being referenced together. Additionally, Link Strength indicates the robustness of the connections, with a higher Link Strength number indicating stronger associations with that citation (van Eck & Waltman, 2022). The lines in the figures represent the strength of the connections. Lines that are more prominent and have a deeper color indicate a greater Link Strength.

4.1. Co-Citation of References

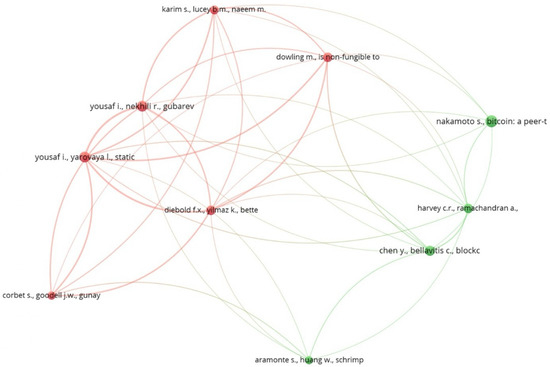

Table 3 and Figure 2 show the reference co-citation analysis. The criteria for inclusion in this analysis required a minimum of 12 cited references to highlight the ten most prominent authors within the network. Table 3 displays the references with the most frequent co-citations within the publications analyzed. It is notable that all the cited sources, except for Nakamoto (2008) and Harvey et al. (2021), consist of articles. Another interesting observation is that, among the top ten most co-cited articles, three belong to the same journal, Finance Research Letters.

Table 3.

Most co-cited references.

Figure 2.

Clusters derived from reference co-citation analysis. This Figure visualizes the network of the ten most cited references in the DeFi literature, with two distinct clusters: Cluster I (red), which focuses on interrelations between crypto assets, and Cluster II (green), exploring the conceptual foundations and influences of DeFi.

Figure 2 displays the ten most cited references in the sample, revealing two distinct clusters: red and green. It is worth noting that of the six publications included in the red cluster, three belong to the journal Finance Research Letters, consistent with Table 3. This observation is not surprising, since articles with similar scopes will choose to publish in similar journals.

Cluster I (red) is labeled “Interrelations between crypto assets” and includes six articles, primarily focused on the interrelations between crypto assets and traditional assets. Karim et al. (2022), with 13 citations, investigate diversification opportunities among NFTs, DeFi tokens, and cryptocurrencies. They identify Theta (NFT) as an effective diversifier for DeFi tokens and cryptocurrencies. This aligns with another two articles in the cluster, Dowling (2022), with 16 citations, and Yousaf and Yarovaya (2022b), with 21 citations. Both articles concluded that NFTs and DeFi are special markets. Dowling (Dowling, 2022) suggests that the NFT market could be considered a distinct market containing multiple asset classes, and Yousaf and Yarovaya (2022b) indicate that NFTs and DeFi assets are decoupled from traditional asset classes. Yousaf et al. (2022), with 21 citations, also conclude that a low connection exists between the Defi market and conventional currency (fiat) market. Corbet et al. (2022), with 12 citations, formulate an index comprising five DeFi tokens and evaluated them against Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Google Trends. This article identifies influences among the different assets analyzed. Diebold and Yilmaz (2012), with 16 citations, study volatility spillovers across US stock, bond, foreign exchange, and commodity markets. The study finds that cross-market volatility spillovers were relatively limited until the global financial crisis in 2007, after which spillovers from the stock market to other markets became more pronounced.

Cluster II (green) is named “Understanding DeFi and Influences” and includes four publications. The main focus of these publications is comprehending DeFi, including its opportunities, challenges, and the interconnections that it can generate with other cryptocurrencies. This cluster, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, contains the oldest publication, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” by Nakamoto (2008), with 26 citations. This white paper is the precursor to cryptocurrencies, introducing the concept of Bitcoin, which aims to facilitate peer-to-peer payments without intermediaries. This document could be considered the basis of exploration for this group. Subsequently, two papers and one book delve into understanding DeFi: Chen and Bellavitis (2020), with 17 citations, Aramonte et al. (2021), with 12 citations, and the book by Harvey et al. (2021), with 15 citations. These publications provide a comprehensive overview of DeFi, encompassing promises, major Business models, and limitations within the DeFi landscape.

The strongest Link Strength is observed in Yousaf and Yarovaya (Total Link Strength equal to 46), followed by Diebold and Yilmaz, with a Total Link Strength of 35. Despite being the most cited publication, Nakamoto has the lowest Total Link Strength.

These findings reveal that the most important seminal papers in DeFi research are still those mainly focused on the delimitation of the concept and its main features, especially regarding its applications for risk diversification in financial markets.

4.2. Co-Citation of Authors

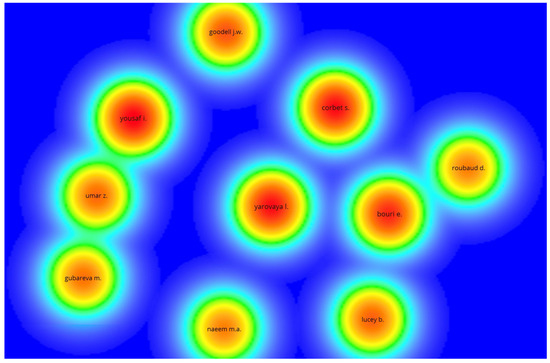

Table 4 and Figure 3 present the outcomes of the most frequently co-cited authors. The criteria for inclusion in this analysis required a minimum number of citations for an author of 92 citations to isolate only the most impactful authors across the entire DeFi literature within the Business and Economics fields. A comparison of Table 4 with Table 3 or Figure 2 reveals that certain authors listed in Table 4 also appear in Table 3 and Figure 2. Additionally, by examining the table, it can be observed that the Total Link Strength is generally stronger among authors who have been more frequently cited. However, this dynamic changes when it comes to Goodell. Goodell has a Link Strength of 1880 compared to Umar, which is 2212. Total Link Strength serves as an indicator of the strength of that connection with other authors in terms of co-citation. Furthermore, it can be observed that the authors are included in two different clusters, but with the same weight, five authors per cluster. This clustering is indicative of a similar thematic focus among these authors.

Table 4.

Top ten co-cited authors.

Figure 3.

Density map of author co-citation analysis. This figure shows a density map illustrating the co-citation probabilities of authors in DeFi literature, with redder circles indicating higher citation frequencies and greener circles denoting lower frequencies, highlighting strong co-citation relationships between author pairs.

Figure 3 has been employed to examine the probability of two authors being co-cited. The density map represents authors with colors, where a redder circle indicates more citations, and a greener circle suggests fewer citations. Yousaf is highly likely to be cited in a document with Umar but less likely with Lucey. Similarly, it is highly likely that Bouri is cited with Roubaud (mainly because they are co-authoring many publications) but less likely with Goodell.

These results reveal some interesting patterns regarding the different focuses of DeFi research in the Business and Economics fields. While mainly paying attention to market aspects, Yousaf and Umar share an incipient interest in some specific topics, such as sustainability issues (S. Ali et al., 2025a, 2025b).

4.3. Bibliographic Coupling of Articles

As DeFi is still in an early stage of development, and considering the proximity of the study dates, a minimum threshold of two citations per document was set for conducting the bibliographic coupling of articles. With two citations, it is considered that the document has already established a certain foundational level of base knowledge, making it worthwhile to analyze its relationship with other documents. While two citations may appear insignificant, it is noteworthy that a significant portion of scientific papers are rarely or never cited in the subsequent scientific literature (Aksnes, 2003).

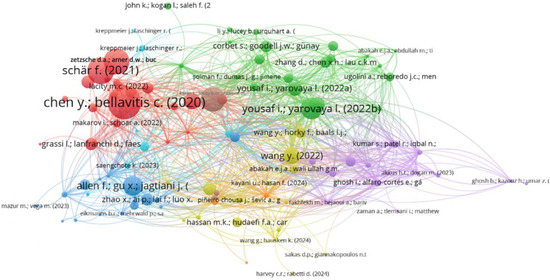

Figure 4 presents the bibliographic coupling of articles. The colors of the labels represent the various clusters of cited references included in the analysis. By setting a limit of two citations, the figure consists of 111 interconnected articles, forming eight distinct clusters. The cluster with more articles is the red one, with 26 articles, followed by the green cluster, which is composed of 21 articles.

Figure 4.

Clusters derived from the bibliographic coupling analysis. This Figure shows the bibliographic coupling network of 111 DeFi articles, visualized with a minimum of two citations, creating eight different clusters.

It is worth noting that the two most cited articles, Chen and Bellavitis (2020) and Schär (2021), align with the data presented in Table 2 and the co-citation references listed in Table 3, emphasizing the importance of this cluster. The orange and brown cluster are the smaller ones, with 3 articles each. The clusters identified from the analysis are

- Cluster I (red) is titled “Decoding DeFi” and consists of 26 articles. The main theme of these articles is the understanding of DeFi, covering how it works, the analysis of potential business opportunities, the associated risks, and the implications of decentralization.

- Cluster II (green) is titled “What drives crypto asset markets?” and comprises 21 articles. The articles explore, through various comparisons, how cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and DeFi behave in relation to traditional assets such as the stock market and gold or fiat currencies, as well as the relationships among them. They even address how energy prices or geopolitical conflict impact the expected returns in blockchain markets.

- Cluster III (blue) is titled “Governance and oversight in DeFi” and includes 19 articles. The main topics discussed in these articles are the control within DeFi from its architecture to its ability to generate financing. They delve into topics including new regulation, blockchain auditing processes, and mechanisms for control in the innovative financing methods enabled by DeFi.

- Cluster IV (yellow) is titled “Cryptocurrency dynamics and integration in financial ecosystems” and consists of 16 articles. The main theme of these papers is speculative risks, regulatory challenges, and financial inclusion, while investigating market interactions (through traditional and digital assets as well as investor sentiment), environmental impacts, and emerging financial technologies.

- Cluster V (purple) is titled “Price movements in decentralized financial and crypto assets” and comprises 14 articles. The primary focus of these articles is the correlation and behavior that different crypto assets show in different scenarios.

- Cluster VI (light blue) is titled “Decentralized governance and disintermediation” and comprises nine articles. The main topics discussed in these articles are the governance in DeFi and the real or unreal possibility of the disintermediation through DeFi.

- Cluster VII (orange) is titled “How and why to own NFTs?” and included three articles. The primary focus of these articles is NFTs. Through these articles, the different strategies and motivations for owning and issuing NFTs are exposed.

- Cluster VIII (brown) is titled “Financial innovations and Metaverse ecosystems” and includes three articles. The articles provide a comprehensive analysis of the role of DeFi in advanced digital markets. They delve into topics including financial integration within the Metaverse, diversification and risk transmission in blockchain markets, and the determinants of interest rates in cryptocurrency lending.

From these results, we can highlight the scarce attention paid to real economy issues in the existing research. The different clusters are mainly related to the analysis of the main features of DeFi, namely decentralization (Clusters I and VI), risk diversification and market efficiency (Clusters II and V), and investors’ behavior (Cluster VII). Cluster IV is the most related to the real economy, paying attention to topics such as DeFi regulation and sustainability-related worries such as financial inclusion or environmental impacts.

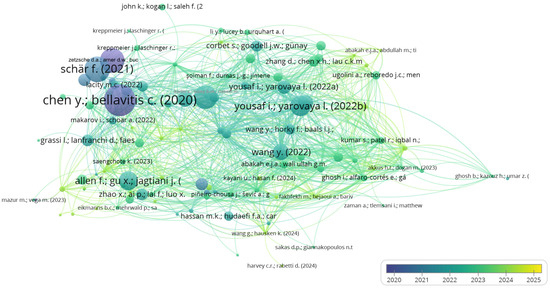

Figure 5 provides an analysis of how the bibliographic coupling of articles has evolved over the years. The color of the labels indicates the period to which the articles belong, ranging from a deep purple tone for the earliest period to a soft yellow tone for the latest period. On the left side of the figure, notable works by Chen and Bellavitis (2020), Schär (2021), and Zetzsche et al. (2020) stand out in a darker shade, reflecting the period in which they were published. These works, being from the earliest period, had more time to accumulate citations, as seen in Table 2, and can be considered pioneers in the field of DeFi, building the knowledge base in the field.

Figure 5.

Bibliographic coupling of articles over time. This Figure illustrates the bibliographic coupling analysis over time, with label colors transitioning from deep purple for earlier publications to soft yellow for recent ones.

Upon closer inspection, it becomes apparent that the work of Karim et al. (2022) stands out in the upper middle, while that of Yousaf and Yarovaya (2022b) is prominent in the right center. These articles, more distant from the works of the early years but with a prominent label, may indicate a new research trend. The works by Chen and Bellavitis (2020), Schär (2021), and Zetzsche et al. (2020) focused on understanding what DeFi is and the opportunities it brings, while the works by Karim et al. (2022) and Yousaf and Yarovaya (2022b) focus on how DeFi behaves in relation to other assets and its hedging power when it is included in a portfolio. The primary themes addressed in these papers align with progression over time, transitioning from an understanding of DeFi to its practical application as a new development in financial markets.

4.4. Bibliographic Coupling of Sources

Table 5 presents the bibliographic coupling of sources, with a minimum requirement of four documents for each source to be included in the analysis, thereby focusing on the core publication venues with a sustained focus on DeFi research. This analysis reveals three clusters. The most prominent cluster, Cluster I, has garnered a total of 724 citations, accounting for approximately 62% of the total citations received. Cluster I comprises journals dedicated to advancing the core body of knowledge in Finance. According to the Journal Citation Indicator (JCI), all the journals, except Frontiers in Blockchain, are positioned in Q1 in Business and Finance or solely in Business. Frontiers in Blockchain, however, is positioned in Q3 in the Computer Science Interdisciplinary Applications field. These rankings are supported by the Scimago Journal and Country Rank (SJR). While Finance Research Letters, Research in International Business and Finance, and Technological Forecasting and Social Change maintain Q1 rankings in Finance or Business, the Journal of Risk and Financial Management is ranked in Q2 in these fields, and Frontiers in Blockchain is not ranked.

Table 5.

Most cited sources.

4.5. Author Keywords Co-Occurrence Analysis

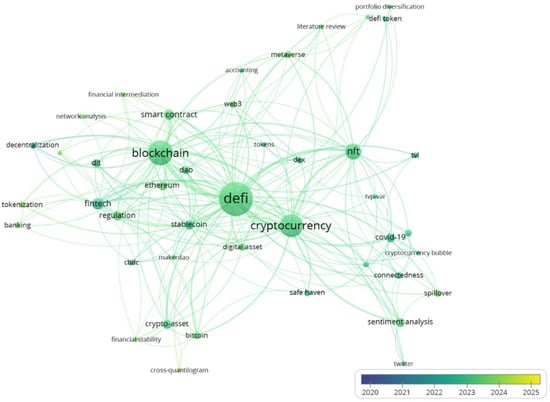

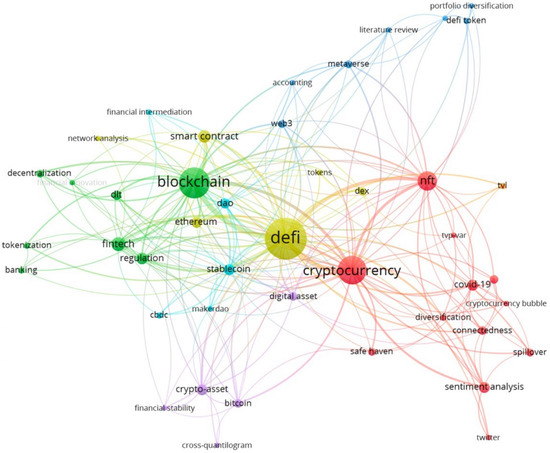

The criterion for inclusion in the author keywords co-occurrence analysis was at least three co-occurrences in order to reduce noise and focus on robust concepts. This decision was made to capture a larger set of author keywords and thus draw more general conclusions, avoiding those words that were used only once or twice and could introduce noise into the sample rather than contribute interesting insights. With this criterion, a total of forty-four keywords were identified.

Figure 6 presents the analysis of author keywords occurrence over time. The color of the labels indicates the period to which the articles belong, ranging from a deep purple tone representing the earliest period to a soft yellow tone representing the latest period. The analysis resulted in a total of forty-four keywords mostly used by the authors. Dominating the center of the figure is the word “DeFi,” which stands out as the most frequently employed term by authors in the sample, totaling 138 occurrences. Two other prominent words are “blockchain” and “cryptocurrency”. These words are used 78 and 66 times, respectively. These terms are frequently utilized because the blockchain serves as the underlying technology for DeFi, and cryptocurrencies play a fundamental role within this new technology as the means of exchange and payment in protocols. They are highlighted in soft green, suggesting that most of the articles were recently written. Thus, Figure 6 aligns with Figure 1, which indicated that many of the articles were from 2023 and 2024. Furthermore, as their temporal weights are recent, this suggests that these keywords remain among the most frequently used.

Figure 6.

Evolution of author keywords co-occurrence over time. This Figure illustrates the author keywords co-occurrence analysis over time, with label colors transitioning from deep purple for earlier publications to soft yellow for recent ones.

Figure 7 presents the different thematic clusters derived from the author keywords. The results show a total of seven distinct clusters.

Figure 7.

Results from the author keywords co-occurrence analysis. This Figure represents the results from the author keywords co-occurrence analysis from the DeFi literature, revealing seven distinct clusters.

- Cluster I (red) is organized around the keyword “cryptocurrency”, which appears 66 times and is linked to 11 other items. The keywords in this cluster relate to the asset’s behavior within portfolio composition. Among them are terms such as “safe haven”, “diversification”, “TVP-VAR”, and “sentiment analysis”, among others.

- Cluster II (green) has “Blockchain” as its most cited keyword, with 78 occurrences and connections to seven other items. This cluster comprises keywords related to the underlying technology and its anticipated impact on sectors such as banking. Notable terms include “tokenization”, “decentralization”, “financial innovation”, and “regulation”, among others.

- Cluster III (blue) has the keyword “Metaverse” as the most cited, with six occurrences and connections to six other items. This is a relatively small and emerging cluster. However, it already shows the presence of the literature reviews aimed at understanding its mechanisms and potential as a diversifying asset in investment portfolios with “literature review” or “portfolio diversification” between the words that are included in this cluster.

- Cluster IV (yellow) is organized around the keyword “DeFi”, with 138 occurrences and connections to five other items. The focus of this cluster lies in the decentralization aspect of DeFi itself and its operation within the Ethereum network.

- Cluster V (purple) has “Crypto-asset” as its most cited keyword, with 10 occurrences and connections to four other items. Between the keywords that appear in this cluster, Bitcoin shows seven occurrences. It is surprising that Bitcoin is not the dominant keyword in its cluster, given that it was the first crypto asset and cryptocurrency.

- Cluster VI (light blue) has the keyword “Stablecoin” as the most cited, with 11 occurrences and connections to other four items. This cluster represents a segment of the literature concerned with stabilizing mechanisms within the cryptocurrency market. A major concern in the crypto market is the high volatility that prevents cryptocurrencies from being treated like traditional currencies. Stablecoins attempt to mitigate this volatility, enabling public adoption for commercial purposes.

- Cluster VII (orange) consists solely of the keyword “TVL”, which appears four times and has direct links to “DeFi”, “Blockchain”, “NFTs”, and “COVID-19”.

This set of keywords is consistent with that found by Aydaner and Okuyan (2024) in their co-occurrence of keywords analysis, including the identification of the Metaverse as an emerging term on the DeFi research front. The identified clusters reveal, once again, an absence of focus on real economy issues in current research. Some expected keywords if the current DeFi literature had a bigger connection to the real economy could be

- -

- In relation to sustainability issues: ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance), Impact Investing, Carbon Credits, and Green Bonds…

- -

- In relation to economic growth: Productivity, Efficiency, Innovation, Entrepreneurship, Supply Chain, and Labor Market…

- -

- In relation to financial activity and inclusion: Unbanked, Remittances, Microfinance, and Decentralized Lending…

4.6. Final Discussion

Although DeFi continues to evolve rapidly, its exploration in Business and Economics areas remains nascent and reveals a limited focus on DeFi’s impacts on the real economy (Aquilina et al., 2024). The results from the bibliometric analyses performed are consistent with those obtained by the previous, more directly comparable bibliometric study on DeFi, that of Aydaner and Okuyan (2024), particularly regarding the specification of the DeFi knowledge base through the analysis of the co-citation of references and the analysis of the DeFi research front through the analysis of keyword co-occurrences.

A preliminary sample description reveals, through Table 1, a surge in publication since 2020, reflecting growing academic interest. Bibliometric analyses, including co-citations, bibliographic coupling, and author keyword co-occurrences, identify key development pillars, such as DeFi’s theoretical foundations (Chen & Bellavitis, 2020; Schär, 2021; Zetzsche et al., 2020), DeFi’s market dynamics (Karim et al., 2022; Yousaf & Yarovaya, 2022b), and governance challenges (Alamsyah et al., 2024; Makridis et al., 2023).

The results show the big focus of past and current research on market dynamics (e.g., Cluster I in the co-citation references analysis and several clusters in the bibliographic coupling analysis). A comprehensive understanding of DeFi is a missing component (Puschmann & Huang-Sui, 2024). There is a scarcity of scientific publications on the taxonomy of DeFi (Alamsyah et al., 2024), DeFi Business models (Beinke et al., 2024), and how DeFi can directly transform the real economy, particularly in terms of its structural impact on entrepreneurship, production, and employment beyond the financial sector. Although some recent works (Aggarwal, 2024; S. R. Ali et al., 2024; Archana & Gloth, 2024; Harir & Bel Mkaddem, 2024; Musungwini & Furusa, 2024; Shyamaladevi et al., 2025) have started to explore the role of DeFi as a complement or substitute to traditional finance, these investigations remain fragmented and relatively scarce compared to the broader volume of the DeFi literature.

There are many underexplored connections to real economy activities like entrepreneurship and financial inclusion (Aggarwal, 2024; S. R. Ali et al., 2024; Archana & Gloth, 2024; Musungwini & Furusa, 2024), such as how DeFi platforms facilitate credit access for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and entrepreneurs, the adoption of decentralized lending, or the understanding of the structural implications of applying DeFi in everyday economic activities.

This lack of academic focus on the intersection between DeFi and the real economy appears to mirror prevailing trends within DeFi markets. Up to now, DeFi has primarily supported transactions within the crypto ecosystem rather than contributing to real-world economic activities (Aquilina et al., 2024), while the main use of DeFi tokens by investors seems to be speculation (Chu et al., 2023; Ghosh et al., 2023). For many researchers, this demands an acceleration towards the reasonable regulation of DeFi (Bennett et al., 2023).

The findings provide a comprehensive overview of DeFi’s landscape, uncovering hidden structures and dynamics in the academic literature (Zupic & Čater, 2015). This is highly relevant for researchers, guiding them towards underexplored areas, such as the interactions between DeFi and the Metaverse (Kumar et al., 2024), as well as for regulators and practitioners.

5. Conclusions, Future Directions, and Limitations

The surge in interest in DeFi among researchers, with academic publications multiplying by more than double digits in recent years, demands periodic updates of the academic landscape to capture the rapidly evolving DeFi space (Puschmann & Huang-Sui, 2024).

Bibliometric analyses have explored the foundational knowledge, author relationships, emerging trends, and temporal shifts within the DeFi landscape in the Economics and Business fields, offering valuable insights into comprehending its evolution and progress. These analyses allow practitioners, researchers, and regulators to understand the state of knowledge and future trends in DeFi. Regulators need to build on this knowledge base to develop laws that facilitate the transition to DeFi while protecting consumers. Researchers can explore the foundations of DeFi, seek new collaborations based on the authors’ identified networks, and propose new lines of research inspired by the emerging trends found in the analyses. These opportunities also help to reduce research redundancy and advance cumulative knowledge in the field. Finally, practitioners could find specialized advisors among authors publishing on DeFi and use these insights to create diversified cryptocurrency portfolios or explore tokenization for investment opportunities or interactions in the Metaverse.

The findings highlight that DeFi research is predominantly focused on crypto ecosystem transactions and speculative token uses, with limited exploration of its potential to transform real-world economic activities. More research is needed on the connections between DeFi and the incumbent financial system (Puschmann & Huang-Sui, 2024). More systematic research is needed to examine how DeFi can influence key economic indicators such as savings behavior, SME financing, wealth distribution, and infrastructure development—particularly in contexts underserved by traditional finance. This study responds to this gap by highlighting the need for a more integrated understanding of DeFi’s role in shaping real economic outcomes beyond its financial and speculative dimensions.

Building on this identified gap, future research should delve into the mechanisms through which DeFi can generate tangible benefits for the real economy. Key questions could be structured into three orientations to enhance practical applicability: (i) Theoretical: Develop frameworks to conceptualize how DeFi platforms facilitate credit access for SMEs and self-employed individuals, particularly in developing or underbanked regions. What are the socioeconomic profiles of DeFi users engaging in productive rather than speculative activities? (ii) Empirical: How does the adoption of decentralized lending, insurance, or payment systems affect financial stability and monetary policy transmission in different economic contexts? Additionally, to better understand its structural implications, researchers should investigate the long-term effects of DeFi on conventional banking models, labor markets, and investment behavior, as well as the impact on environmental protection, social equity, and governance. (iii) Policy: Explore regulatory models that balance consumer protection with DeFi innovation. Exploring these dimensions will be essential to determine whether DeFi merely serves as a parallel speculative arena or becomes an integral pillar of inclusive, innovation- and sustainability-driven economic development.

One notable limitation of this bibliometric study lies in the exclusive use of the keywords “DeFi” or “Decentralized Finance” as a search criterion. While this approach ensures the retrieval of research that explicitly engages with the DeFi concept as a whole, it may have inadvertently excluded academic contributions that, although not labeled under “DeFi,” explore the interactions between specific DeFi components (such as decentralized lending, Stablecoins, or Decentralized Exchanges) and the real economy. As a result, the analysis may underrepresent the extent to which the academic literature has examined the economic implications of these technologies. Nevertheless, the decision to prioritize the overarching term “DeFi” or “Decentralized Finance” responds to a deliberate interest in capturing the conceptual and systemic treatment of DeFi as an integrated phenomenon. Studying DeFi provides a better understanding of its potential to reshape financial infrastructure, governance, and institutional design—dimensions that may be overlooked when focusing on isolated mechanisms or platforms. The use of Scopus is another limitation, as it does not contain references before 1996, although this does not affect the current sample, which starts from 2008. Nonetheless, relying on a single database may result in the loss of relevant information from other databases such as the Web of Science or Google Scholar. Additionally, the sample size is limited due to the emerging nature of the knowledge, which may not be extensive enough for Bradford’s Law or Lotka’s Law. Future research could expand the sample to include more databases or even consider the existing gray literature.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft and previous versions of the manuscript were written and commented on by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Bibliometric data employed in this work can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AML | Anti Money Laundering |

| CEX | Centralized Exchanges |

| DAO | Decentralized Autonomous Organizations |

| DeFi | Decentralized Finance |

| DEX | Decentralized Exchanges |

| KYC | Know your Customer |

| NFT | Non Fungible Tokens |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SME | Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises |

| TradFi | Traditional Finance |

| TVL | Total Value Locked |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Abakah, E. J. A., Wali Ullah, G., Adekoya, O. B., Osei Bonsu, C., & Abdullah, M. (2023). Blockchain market and eco-friendly financial assets: Dynamic price correlation, connectedness and spillovers with portfolio implications. International Review of Economics & Finance, 87, 218–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, J. (2024). DeFi and investing in entrepreneurial ventures. In S. Basly (Ed.), Decentralized finance: The impact of blockchain-based financial innovations on entrepreneurship (pp. 11–30). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei Chadegani, A., Salehi, H., Yunus, M., Farhadi, H., Fooladi, M., Farhadi, M., & Ale Ebrahim, N. (2013). A Comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2257540 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Aksnes, D. W. (2003). Characteristics of highly cited papers. Research Evaluation, 12(3), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, A., Kusuma, G. N. W., & Ramadhani, D. P. (2024). A review on decentralized finance ecosystems. Future Internet, 16(3), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Youssef, M., Umar, M., & Naeem, M. A. (2025a). ESG meets DeFi: Exploring time-varying linkages and portfolio implications. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 30(3), 3119–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Zhang, T., & Yousaf, I. (2025b). Interlinkage between lending and borrowing tokens and US equity sector: Implications for social finance. Research in International Business and Finance, 73, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. R., Mandava, S. K., Shuja, T. B., Faraz, M., & Gulzar, S. (2024). Blockchain and entrepreneurship: Managing technological innovation for business transformation. International Journal of Trends and Innovations in Business & Social Sciences, 2(4), 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F., Gu, X., & Jagtiani, J. (2022). Fintech, cryptocurrencies, and CBDC: Financial structural transformation in China. Journal of International Money and Finance, 124, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S. L. N., Jorge-Vázquez, J., Rodríguez, P. A., & Hernández, B. M. S. (2023). Gender gap in the ownership and use of cryptocurrencies: Empirical evidence from Spain. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(3), 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolfatto, D., & Martin, F. M. (2022). The blockchain revolution: Decoding digital currencies. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 104, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilina, M., Frost, J., & Schrimpf, A. (2024). Decentralized finance (DeFi): A functional approach. Journal of Financial Regulation, 10(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramonte, S., Huang, W., & Schrimpf, A. (2021). DeFi risks and the decentralisation illusion. Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- Archana, K., & Gloth, A. (2024). Blockchain and entrepreneurship. In Applying business intelligence and innovation to entrepreneurship (pp. 35–51). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspris, A., Foley, S., Svec, J., & Wang, L. (2021). Decentralized exchanges: The “wild west” of cryptocurrency trading. International Review of Financial Analysis, 77, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsen, H., Jensen, J. R., & Ross, O. (2022). When is a DAO Decentralized? Complex Systems Informatics and Modeling Quarterly, 31, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydaner, G., & Okuyan, H. A. (2024). Decentralized finance: A comparative bibliometric analysis in the Scopus and WoS databases. Future Business Journal, 10(1), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbereau, T., Smethurst, R., Papageorgiou, O., Sedlmeir, J., & Fridgen, G. (2023). Decentralised finance’s timocratic governance: The distribution and exercise of tokenised voting rights. Technology in Society, 73, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, S., Aggarwal, V., Yadav, M., & Kumar, P. (2024, January 3–5). A bibliometric visualization of decentralized finance in smart contracts. 2024 18th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM) (pp. 1–5), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becha, H., Kalai, M., Houidi, S., & Helali, K. (2025). Digital financial inclusion, environmental sustainability and regional economic growth in China: Insights from a panel threshold model. Journal of Economic Structures, 14(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinke, M., Beinke, J. H., Anton, E., & Teuteberg, F. (2024). Breaking the chains of traditional finance: A taxonomy of decentralized finance business models. Electronic Markets, 34(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, H., & Kostovetsky, L. (2021). Digital tulips? Returns to investors in initial coin offerings. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D., Mekelburg, E., & Williams, T. H. (2023). BeFi meets DeFi: A behavioral finance approach to decentralized finance asset pricing. Research in International Business and Finance, 65, 101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezemer, D., & Hudson, M. (2016). Finance is not the economy: Reviving the conceptual distinction. Journal of Economic Issues, 50(3), 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongini, P. A., Mattassoglio, F., Pedrazzoli, A., & Vismara, S. (2025). Crypto ecosystem: Navigating the past, present, and future of decentralized finance. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 50, 2054–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, C., & Zhu, H. (2012). Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: A missing link in the transmission mechanism? Journal of Financial Stability, 8(4), 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S. C. (1985). Sources of information on specific subjects 1934. Journal of Information Science, 10(4), 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, E. I., Gunay, S., Zafar, M. W., Destek, M. A., Bugan, M. F., & Tuna, F. (2022). The impact of digital finance on the natural resource market: Evidence from DeFi, oil, and gold. Resources Policy, 79, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., & Bellavitis, C. (2020). Blockchain disruption and decentralized finance: The rise of decentralized business models. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 13, e00151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J., Kahn, C. M., & Koeppl, T. V. (2022). Grasping decentralized finance through the lens of economic theory. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne d’économique, 55(4), 1702–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M. A. F., Abdullah, M., Alam, M., Abedin, M. Z., & Shi, B. (2023). NFTs, DeFi, and other assets efficiency and volatility dynamics: An asymmetric multifractality analysis. International Review of Financial Analysis, 87, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J., Chan, S., & Zhang, Y. (2023). An analysis of the return–volume relationship in decentralised finance (DeFi). International Review of Economics & Finance, 85, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, S., Goodell, J. W., Gunay, S., & Kaskaloglu, K. (2021). Are DeFi Tokens a separate asset class from conventional cryptocurrencies? Annals of Operations Research, 322(2), 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, S., Goodell, J. W., & Günay, S. (2022). What drives DeFi prices? Investigating the effects of investor attention. Finance Research Letters, 48, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D. J., Johan, S., & Pant, A. (2019). Regulation of the crypto-economy: Managing risks, challenges, and regulatory uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(3), 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F. X., & Yilmaz, K. (2012). Better to give than to receive: Predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. International Journal of Forecasting, 28(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M. (2022). Is non-fungible token pricing driven by cryptocurrencies? Finance Research Letters, 44, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duszak, A., & Lewkowicz, J. (2008). Publishing academic texts in English: A Polish perspective. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7(2), 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikmanns, B. C., Mehrwald, P., Sandner, P. G., & Welpe, I. M. (2023). Decentralised finance platform ecosystems: Conceptualisation and outlook. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 37(4), 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haddaoui, B., Chiheb, R., Faizi, R., & El Afia, A. (2023). The influence of social media on cryptocurrency price: A sentiment analysis approach. International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems, 13(1), 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowerdew, J., & Li, Y. (2009). English or Chinese? The trade-off between local and international publication among Chinese academics in the humanities and social sciences. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadi, M. F. A., & Sicilia, M.-A. (2022). Analyzing safe haven, hedging and diversifier characteristics of heterogeneous cryptocurrencies against G7 and BRICS market indexes. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(12), 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I., Alfaro-Cortés, E., Gámez, M., & García-Rubio, N. (2023). Prediction and interpretation of daily NFT and DeFi prices dynamics: Inspection through ensemble machine learning & XAI. International Review of Financial Analysis, 87, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, J. W., Yadav, M. P., Ruan, J., Abedin, M. Z., & Malhotra, N. (2023). Traditional assets, digital assets and renewable energy: Investigating connectedness during COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war. Finance Research Letters, 58, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, V., Guggenberger, T., Principato, M., Schellinger, B., & Urbach, N. (2023). A multivocal literature review of decentralized finance: Current knowledge and future research avenues. Electronic Markets, 33, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L., Lanfranchi, D., Faes, A., & Renga, F. M. (2022). Do we still need financial intermediation? The case of decentralized finance—DeFi. In Qualitative research in accounting and management (Vol. 19, pp. 323–347). Emerald Group Holdings Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harir, N., & Bel Mkaddem, Z. (2024). The impact of decentralized finance development on banks deposits variability: PVAR approach. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 33(2), 244–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C. R., Ramachandran, A., & Santoro, J. (2021). DeFi and the future of finance. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M. K., Hudaefi, F. A., & Caraka, R. E. (2021). Mining netizen’s opinion on cryptocurrency: Sentiment analysis of Twitter data. Studies in Economics and Finance, 39(3), 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H., & Masawi, B. (2022). Three and a half decades of artificial intelligence in banking, financial services, and insurance: A systematic evolutionary review. In Strategic change (Vol. 31, pp. 549–569). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarneving, B. (2007). Bibliographic coupling and its application to research-front and other core documents. Journal of Informetrics, 1(4), 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J. R., von Wachter, V., & Ross, O. (2021). An introduction to decentralized finance (DeFi). Complex Systems Informatics and Modeling Quarterly, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S., Lucey, B. M., Naeem, M. A., & Uddin, G. S. (2022). Examining the interrelatedness of NFTs, DeFi tokens and cryptocurrencies. Finance Research Letters, 47, 102696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S., Singh, S., Gupta, S., & Wats, S. (2023). Risk analysis in decentralized finance (DeFi): A fuzzy-AHP approach. In Risk management (Vol. 25). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliber, A. (2022). Looking for a safe haven against American stocks during COVID-19 pandemic. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 63, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, A., Van Looy, B., & Cassiman, B. (2015). Exploring the scope of open innovation: A bibliometric review of a decade of research. Scientometrics, 104(3), 951–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S., Breier, M., & Dasí-Rodríguez, S. (2020). The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(3), 1023–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S., Breier, M., Lim, W. M., Dabić, M., Kumar, S., Kanbach, D., Mukherjee, D., Corvello, V., Piñeiro-Chousa, J., Liguori, E., Palacios-Marqués, D., Schiavone, F., Ferraris, A., Fernandes, C., & Ferreira, J. J. (2022). Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for academic practice. Review of Managerial Science, 16(8), 2577–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]