Abstract

From reviewing the literature, there was still a scarcity of research about direct and indirect relationships between fintech adoption (FA) and banks’ environmental performance (BEP), particularly in developing countries. Therefore, this is a pioneering study that empirically explored the impacts of FA on BEP in the Middle East (ME) region, considering the mediating role of green accounting practices (GAPs)—such as green banking practices (GBPs), green finance (GF), and circular economy practices (CEPs)—based on legitimacy and ecological modernization (EM) theories to address these research gaps. Based on a structured survey and convenience sampling technique, the primary data were obtained from a sample of 500 members of staff from banks in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt, Oman, Iraq, and Jordan. The structural equation model (SEM) was utilized to investigate the relationships among this study’s variables. The findings indicated that FA positively and significantly impacts GBPs, GF, CEPs, and BEP, which answered the first research question. Furthermore, the linkage between FA and BEP is positively and significantly mediated by GBPs, GF, and CEPs; thus, the second research question was answered. The findings provide bank executives and policy makers with valuable understanding and suggestions to deploy more investments in eco-friendly practices to enhance the environmental performance (EP), societal legitimacy, and achieve competitive advantage. Additionally, collaboration among the banking institutions, governments, and international firms is essential to promote FA and GAPs and enhance the EP.

1. Introduction

The prioritization of economic growth, particularly in developing countries, has led to environmental problems like air pollution, climate change, degradation, and land loss because of industrialization, modernization, and unplanned urbanization (Zheng & Siddik, 2022). Due to the necessity of environmental preservation, stakeholders have pressed firms to adopt eco-friendly practices (M. S. Islam et al., 2023). Although the banking sector contributes significantly to global GDP and is being pressured to adopt eco-friendly policies, numerous studies have focused only on the manufacturing sector, as stated by Aslam and Jawaid (2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised interest in environmental performance (EP) among researchers and professionals in the financial industry (Naz et al., 2023). EP is defined as preserving physical environmental elements, which can be assessed through environmental indicators like emissions prevention, waste reduction, and resource efficiency (Zheng & Siddik, 2023). Banks are always considered environmentally friendly and have a crucial role in achieving the country’s economic prosperity and sustainable development (SD) by financing eco-friendly projects like renewable energy and waste recycling (Akter et al., 2018). However, recent changes in the banking sector, such as increased energy and paper usage due to extensive branches and ATMs, raise concerns about environmental impacts (Z. Chen et al., 2018). Banks also have a significant responsibility and accountability to finance various industries, which may result in negative environmental impacts if they finance the most polluting industries (Rehman et al., 2021).

Banks are increasingly adopting eco-friendly technologies like fintech and green accounting practices (GAPs), which are emerging practices to enhance EP (Naz et al., 2023). Toumi et al. (2023) and Serdarušić et al. (2024) stated that fintech’s prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in developing countries, facilitated banks’ transitions in operations. Fintech involves technology adoption like artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics (BDA), and blockchain to provide innovative financial products and services such as digital cash, investment, crowdfunding, wealth management, and digital currency (Dwivedi et al., 2021).

Previous studies have investigated FA’s impact on firms’ financial performance (Liu et al., 2022), firms’ sustainable performance (SP) considering the circular economy practices as a mediator (Siddik et al., 2023a), and GF and green innovation (GI) to boost organizational performance (Al Doghan & Chong, 2023).

On the other hand, fintech’s importance in financial institutions, particularly banks, results in an increasing interest in investigating FA’s impact on banks’ performance (X. H. Chen et al., 2021). Prior studies revealed that FA has significant impacts on banks’ competitiveness and performance (Dwivedi et al., 2021), banks’ FP (Ky et al., 2019), and the carbon footprint of banks’ internal operations (Vergara & Agudo, 2021). Thus, FA’s impact on banks’ performance has not been clearly illustrated in the literature because prior research highlighted the theoretical analysis of FA’s opportunities and threats (Elsaid, 2023), while others focused only on its effects on banks’ FP (Yan et al., 2023; Omarini, 2018). Also, the linkage between FA and BEP is explored in a general manner as stated by Udeagha and Muchapondwa (2023). However, there is still a lack of studies on the direct impact of FA on BEP, which is the first research gap in the extant literature.

Furthermore, there is still a scarcity in the literature about the indirect relationship between FA and banks’ performance, necessitating further investigation by considering various mediating variables. Some studies investigated financial literacy, GF, and GI (Yan et al., 2022; Zheng & Siddik, 2023) as mediators. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior research has investigated GAPs mediating role on the linkage between FA and BEP. Due to global environmental concerns, the banking sector is urged to adopt green accounting (GA), which is an innovative and preventive tool against environmental degradation, providing an understanding of environmental management practices and relevant environmental accounting information (EAI) for making decisions (S. Islam et al., 2023).

Although GA has received significant importance in developing countries, a few studies assessed the influence of adopting GAPs on banks’ performance. Deb et al. (2020) proxied GAPs with three variables involving GF, green banking (GB), and green activity management to examine whether these practices affect the banks’ FP in Bangladesh. Moreover, S. Islam et al. (2023) referred to GBPs and GF as examples of GAPs. Zhang et al. (2022) and Mir and Bhat (2022) defined GB as a banking model that promotes environmental and social practices to reduce banks’ internal and external carbon footprints and enhance their EP. Regarding GF, it is considered a financial investment in different environmentally friendly projects, which promotes EP (Yan et al., 2022) and sustainable economic growth (Zheng et al., 2021b). Additionally, Bag and Pretorius (2020) referred to the circular economy (CE) as an example of GAP that primarily focuses on the efficient use of resources to enhance EP.

Most previous studies on GBP adoption focused only on its prerequisites, challenges, and benefits. Recently, a few studies have explored the impact of GBP adoption on banks’ FP (Akter et al., 2018) while others focused on BEP (J. Chen et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022; Risal & Joshi, 2018; Rehman et al., 2021). Regarding GF, a few studies found that GF improves EP (Zhang et al., 2022), SP (Zheng et al., 2021a), and FP (Indriastuti & Chariri, 2021). Although the existing literature illustrates the linkage between GBPs or GF and banks’ performance, there is still a dearth of literature about FA’s role. FA can support GBP adoption in banks’ internal operations and make the whole banking system eco-friendly, as only stated by Naz et al. (2023) and Shaumya and Arulrajah (2017). Moreover, a few studies (Udeagha & Muchapondwa, 2023; Muganyi et al., 2021) provided limited empirical evidence about the roles of FA and GF toward enhancing BEP. FA can streamline funding processes related to environmental initiatives (Tian et al., 2023; Al Doghan & Chong, 2023) and enhance customer identification processes to mitigate information asymmetry and improve risk management capacities (Wan et al., 2023). Regarding CEPs, there is still a lack of research about FA’s role in facilitating banks’ transition toward CEPs to enhance their EP. Thus, the linkage between FA, GAPs, and BEP in the context of developing countries remains unclear, which is the second research gap.

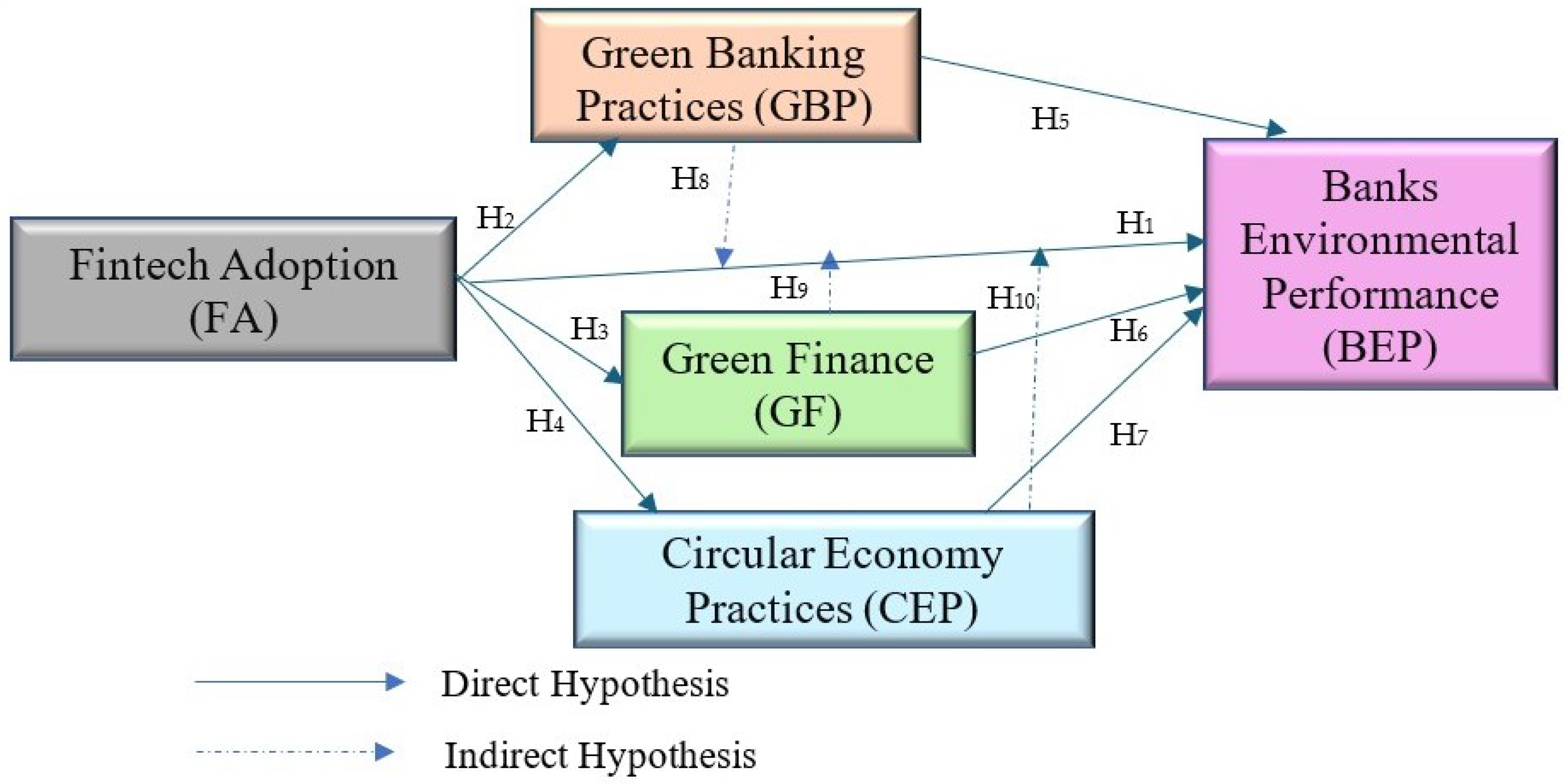

Therefore, to fill the above research gaps, the current study attempts to develop a conceptual model to demonstrate the relationships between FA and BEP in the ME region, considering the mediating role of GBPs, GF, and CEPs and utilizing SEM to test this model empirically. To attain the research goals, the research questions are identified as follows:

- RQ1. Does FA influence BEP?

- RQ2. Do GBPs, CEPs, and GF mediate the linkage between FA and BEP?

This study explores FA’s impacts on BEP using ecological modernization (EM) and legitimacy theories. According to EMT, technological innovations like fintech adoption can overcome environmental challenges such as resource usage and pollution resulting from economic expansion, as argued by Tian et al. (2023). Thus, ecological modernization theory (EMT) provides clear insights into the role of technological innovation, such as fintech, in enhancing BEP. Additionally, legitimacy theory is used to analyze how and why banks adopt GAPs such as GBPs, GF, and CEPs. Siddik et al. (2023c) stated that these practices help the banks attain legitimacy, acceptance, and support from their stakeholders by demonstrating their commitment to society and the environment.

The study’s originality and contributions to the literature are summarized in the following points: First, it is a pioneering study that illustrates the direct relationship between FA and BEP in the ME’s developing countries based on EMT to fill the first research gap. Based on EMT, FA facilitates EM and enables banks to alleviate environmental consequences, enhancing their EP. Second, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, it is the first study that investigates the indirect relationship between FA and BEP in the ME region. Drawing from legitimacy theory, this is a pioneering study that investigates the mediating role of GBPs, GF, and CEPs—as common examples of GAPs—on the relationship between FA and BEP, to fill the second research gap. Third, the study incorporates GBPs, GF, and CEPs simultaneously in a single research model as mediators of the relationship between FA and BEP. Fourth, this study responds to Pizzi et al.’s (2021) and Toumi et al.’s (2023) calls to provide empirical evidence about FA’s impacts on BEP using SEM. Fifth, this is the first study in the ME region that can offer valuable insights for policy makers and banking executives about fintech and GAP adoption to enhance the EP.

The rest of the paper is presented as follows: Section 2 comprises the literature review and hypotheses development; the methodology is provided in Section 3; Section 4 presents the data analysis and results; and Section 5 contains a discussion of the results. Finally, the conclusion, implications, limitations, and paths for future research are provided in Section 6.

2. The Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

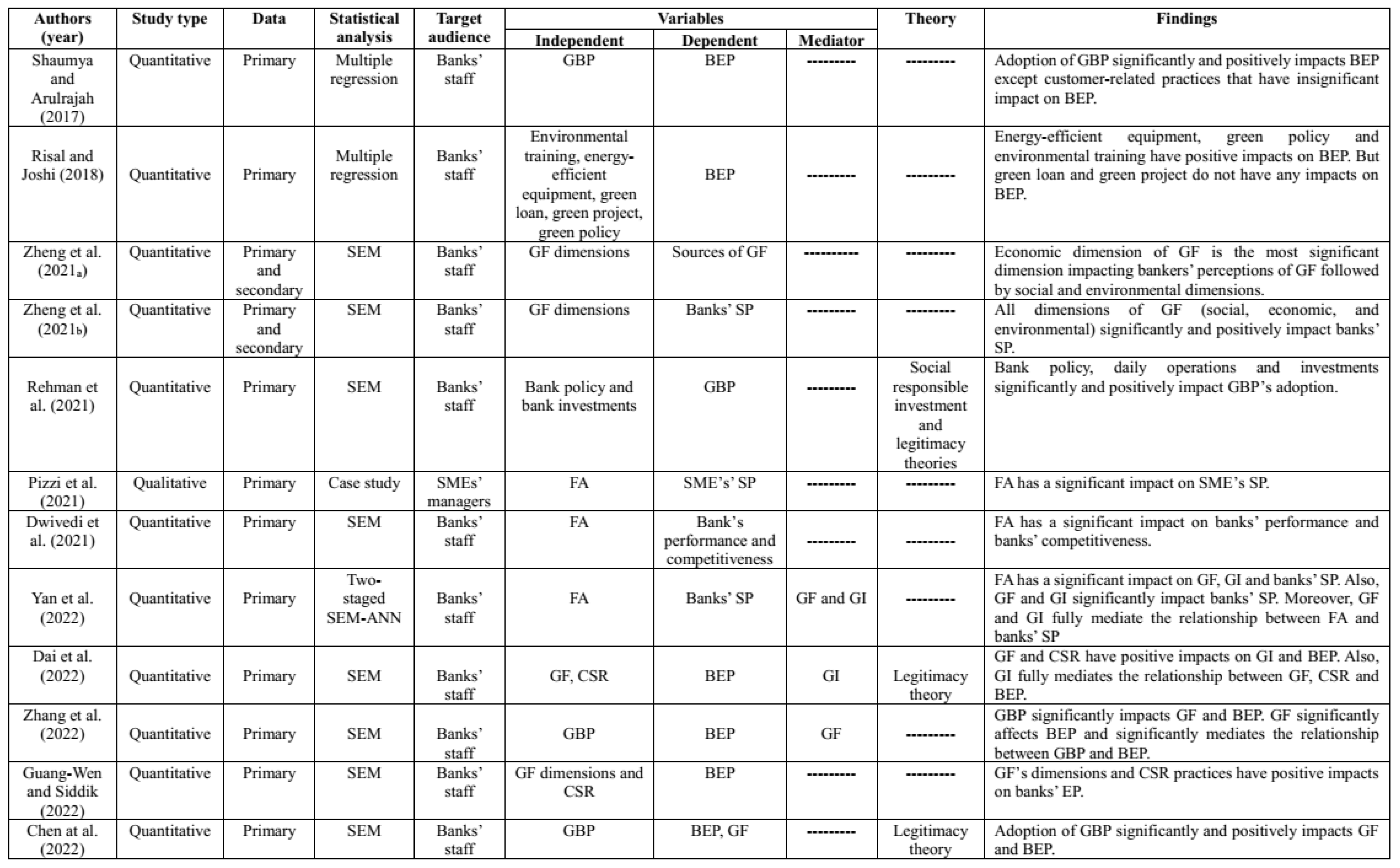

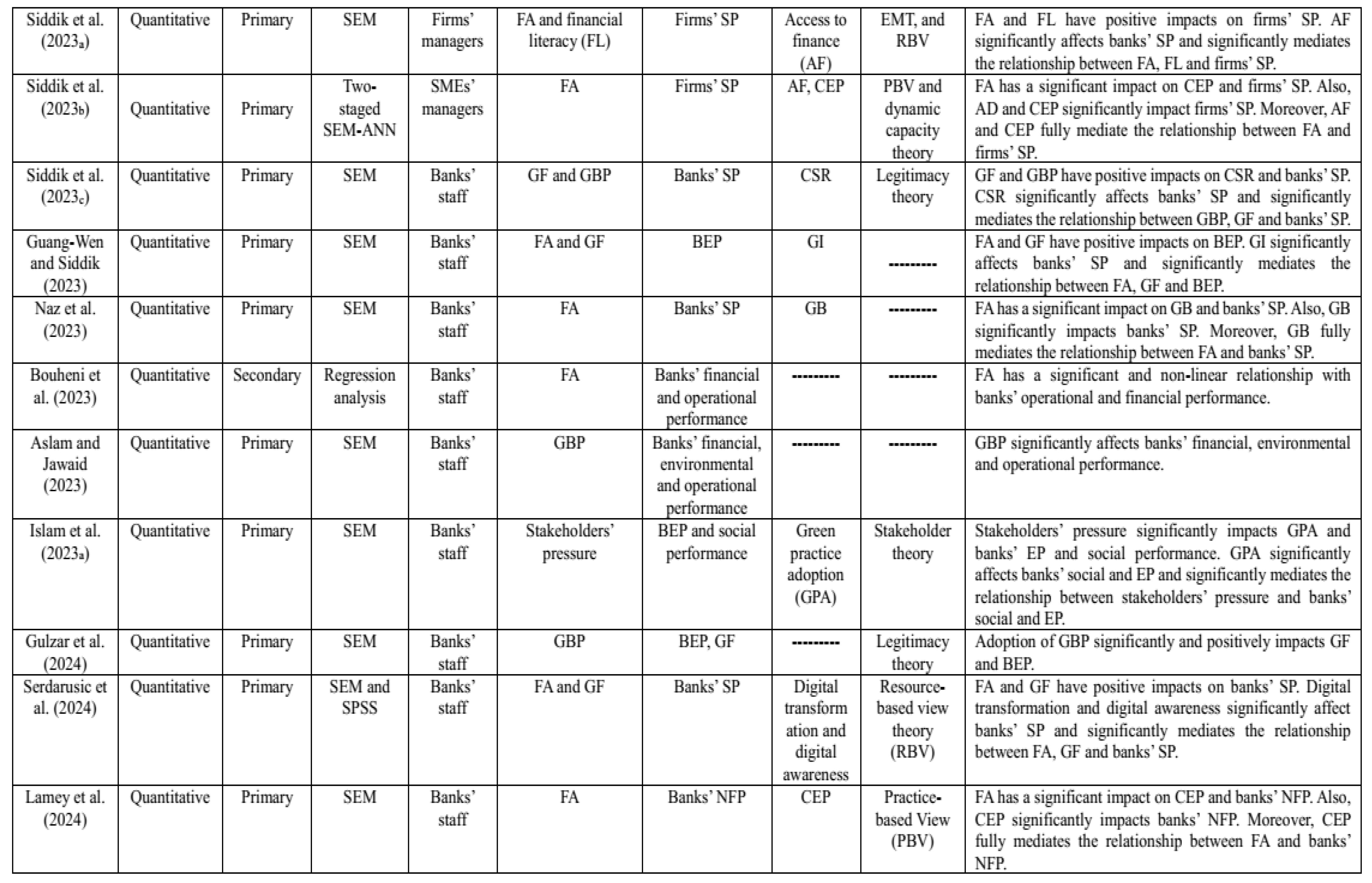

This section highlights the connection between FA and BEP in the context of EMT and legitimacy theories, starting with an overview of the theoretical frameworks and EP of banking institutions of developing countries. Then, an extensive literature review of FA, GBPs, GF, CEPs, and BEP is discussed and summarized in Appendix A.

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks

Several studies utilized different theoretical perspectives in technological adoption, environmental practices, and EP research, such as institutional theory (Wiredu et al., 2023), legitimacy theory (J. Chen et al., 2022; Rehman et al., 2021; Gulzar et al., 2024), stakeholder theory (M. S. Islam et al., 2023; I. U. Khan et al., 2023), and EMT (Tian et al., 2023; Siddik et al., 2023b). This study illustrates FA’s impact on BEP using ecological modernization (EM) and legitimacy theories. EMT presents a theoretical lens to consider fintech as an essential factor of firms’ SP (Siddik et al., 2023b) and firms’ EP (Tian et al., 2023). Similarly, the current study uses EMT to illustrate FA’s impact on BEP.

On the other hand, Zheng and Siddik (2022) referred to the importance of society’s consent in promoting firms’ environmental sustainability. In accordance with legitimacy theory, firms continuously maintain legitimacy by incorporating their values, policies, and strategies with social values to operate in terms of the norms and bounds of their respective societies. Consequently, firms should select practices that are consistent with social beliefs and norms (Dai et al., 2022). Moreover, Siddik et al. (2023c) considered GB and GF as tools for banks to commit to social and environmental expectations and gain legitimacy and assistance from their stakeholders. Thus, the current study utilized legitimacy theory as an essential perspective to explore how GAPs such as GBPs, GF, and CEPs impact BEP.

2.2. Environmental Performance of Banking Institutions of Developing Countries

Banking institutions are special for some reasons: first, they are intermediaries between borrowers and lenders—offering a special form of asset transformation; second, liquidity is an essential service provided to the customers; finally, banks have a critical role in the macroeconomy (Heffernan, 2005).

Although the banking industry is not a polluting industry, it has direct and indirect negative environmental impacts (Aslam & Jawaid, 2023). Banks’ daily operations consume paper and energy extensively due to extensive branches’ networks and ATMs (Rehman et al., 2021), which directly and negatively impact their EP. Moreover, banks have significant indirect environmental impacts due to their financing role toward polluting industries (Aslam & Jawaid, 2023) that generate carbon emissions and harm the environment. Banks can mitigate these impacts by imposing restrictions on industries to adopt green practices and encouraging them through offering loans with lower interest rates (Z. Chen et al., 2018). Therefore, embracing financial technologies and GAPs in banks’ daily operations can reduce their negative environmental impacts to a great extent.

2.3. Fintech Adoption and Banks’ Environmental Performance in Developing Countries

Fintech solutions have rapidly emerged during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The Financial Stability Board (FSB, 2017) defined fintech as an I4.0T involving AI, blockchain, and BDA to promote new business practices and provide innovative financial products and services. This study uses EMT to explore fintech’s role in addressing environmental issues (Tian et al., 2023) like resource preservation, renewable energy usage, carbon emissions, waste reduction, and circular practices (Liu et al., 2022). FA significantly impacts firms’ EP by reducing carbon emissions and manual functions, promoting renewable energy usage and improving resource efficiency (Ashta, 2023; Yan et al., 2023; Awawdeh et al., 2022). Moreover, Liu et al. (2022) confirmed that FA can enhance EP through providing eco-friendly financial products and services. Thus, FA should be linked to firms’ environmental management strategies to enhance their EP, as argued by Zheng and Siddik (2023).

From reviewing the literature, there is still a lack of research pertaining to FA’s impacts on BEP because prior research mainly focused on FA’s impact on banks’ FP (Kharrat et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2023; Omarini, 2018) and non-financial performance (Lamey et al., 2024). The only study by Zheng and Siddik (2023) investigated FA and GF impacts on BEP in Bangladesh, considering GI as a mediator, and found that FA and GF have positive and significant effects on BEP, and the association between FA, GF, and BEP is significantly mediated by GI. According to these arguments, there is no study investigating FA’s impacts on BEP in the ME’s developing countries. Consequently, this study utilizes EMT to validate that FA as an environmental modernization tool can promote BEP, and the following hypothesis is derived as detailed below:

H1:

Fintech adoption has positive and significant impacts on banks’ EP.

2.4. Fintech Adoption and Green Accounting Practices in the Banking Institutions of Developing Countries

GA, or green accounting, is an innovative accounting tool that provides EAI, such as resource usage, waste generation, and emission releases, for decision-making and stakeholder disclosure purposes (Gunarathne et al., 2021). Due to the novelty of GAPs in most developing countries, few studies were conducted to explore the relationship between GAPs and firms’ EP (Wiredu et al., 2023; S. Khan & Gupta, 2023), ignoring the banking sector. However, GAPs have received significant interest in the banking industry due to the growing environmental concerns, necessitating banks to incorporate social and environmental factors into financial reporting, risk assessment, and decision-making processes (Wiredu et al., 2023).

S. Khan and Gupta (2023) referred to the scarcity in the literature about GAPs impact on banks’ performance. S. Islam et al. (2023) and Deb et al. (2020) explored the impact of GF and GI as examples of GAPs on the banks’ FP, respectively, and their findings indicated that GF and GI have significant and positive impacts on banks’ FP. Moreover, there is no previous study that considered GAPs as a mediating variable. Thus, to fill this gap and respond to the calls of S. Islam et al. (2023) and S. Khan and Gupta (2023), this study investigates GBPs, GF, and CEPs mediating roles on the relationship between FA and BEP in the ME region. Therefore, FA’s role in adopting GBPs, GF, and CEPs as GAPs to enhance BEP is presented in the further sections.

2.4.1. Fintech Adoption and Green Banking Practices

GB is an emerging concept that integrates eco-friendly practices into banking operations (Aslam & Jawaid, 2023). Initially, it was implemented by Triodos Bank in 1980, serving as a guideline for the banks to establish GB policies in 1990 (Mir & Bhat, 2022).

Mir and Bhat (2022) referred to the obstacles that may hinder the banks’ adoption of GBPs, such as the lack of technology. On the other hand, Vergara and Agudo (2021) asserted that information technology revolutions, such as Industry 4.0, are key drivers of influencing the banking industry. Fintech solutions can help banks’ adoption of GBPs such as branchless banking, paperless storage, and video conferences (Z. Chen et al., 2018) and enhance the involvement of environmental management within banks’ internal and external operations (Naz et al., 2023). Thus, based on the above discussion, fintech is considered a disruptive technological tool that facilitates banks’ adoption of GBPs. Therefore, the following hypothesis is derived as stated below:

H2:

Fintech adoption has positive and significant impacts on banks’ GBPs.

2.4.2. Fintech Adoption and Green Finance

GF is one type of GAP and is considered an innovative financial instrument that incorporates social and economic aspects with environmental concerns to drive green transformation in both developed and developing countries (J. Chen et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022; Deb et al., 2020). However, the lack of technological innovations poses a considerable challenge for banks’ GF, especially in developing countries (Zheng et al., 2021a, 2021b). Therefore, FA can help overcome this issue, as mentioned by Al Doghan and Chong (2023).

Prior research demonstrated that FA supports banks’ implementation of GF to enhance EP through adopting I4.0T like machine learning, blockchain, and BDA which can reduce information asymmetry between borrowers and lenders (Wan et al., 2023), promote crowdfunding for eco-friendly projects such as renewable energy projects (Tian et al., 2023; Udeagha & Muchapondwa, 2023), and facilitate risk assessment and making decisions (Yan et al., 2022). Therefore, based on these arguments, FA is considered a critical enabler for the banks’ GF. So, the following hypothesis can be postulated as outlined below:

H3:

Fintech adoption has positive and significant impacts on banks’ GF.

2.4.3. Fintech Adoption and Circular Economy Practices

CE has gained global prominence because of its significant impact on sustainability. CE is a business model that raises resources’ longevity and reduces waste generation (Ozili, 2021). Moreover, firms can enhance their green capabilities and CEPs through environmental competencies like EMS and GAPs, as mentioned by Bag and Pretorius (2020). Prior research demonstrated the relationship between CE and technological innovation to facilitate firms’ adoption of CEPs within their business model (Lamey et al., 2024; Ozili, 2021) to boost their EP.

Financial technologies play a crucial role in promoting the adoption of CEPs. Pizzi et al. (2021) confirmed the significant role of FA in promoting firms’ adoption of CEPs by offering new tools for financial resource accessibility. On the other hand, fintech promotes banks’ transformation into CE models by utilizing I4.0T such as BDA and AI, which enhance information disclosures and risk assessment (Siddik et al., 2023a). Thereby, the following hypothesis can be formulated as stated below:

H4:

Fintech adoption positively and significantly impacts banks’ C CEPs.

2.5. Green Banking Practices and Banks’ Environmental Performance

Vergara and Agudo (2021) highlighted the importance of GBPs in attaining banks’ competitive advantage, particularly in developing countries. S. Islam et al. (2023) referred to the importance of incorporating GBPs in banks’ environmental policies and strategies to enhance their EP, like solar energy systems, online bill payments, and green credit cards that can reduce deforestation, raise environmental awareness, and conserve natural resources.

Recently, Rehman et al. (2021) and Shaumya and Arulrajah (2017) demonstrated the impact of GBP adoption on BEP in Pakistan and Sri Lanka, respectively, and found that GBP adoption results in diminishing the negative environmental consequences of banking daily operations. The relationship between GBPs and BEP was investigated in Nepal (Risal & Joshi, 2018) using regression analysis and in Bangladesh focused on legitimacy theory and using SEM (Zhang et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2021b; Siddik et al., 2023c), and the findings revealed that GBP adoption has significant and positive impacts on BEP. Moreover, Aslam and Jawaid (2023) explored the GBPs’ impact on banks’ operational, financial, and environmental performance in Pakistan using SEM and based on resource-based view theory and found that GBP adoption significantly and positively impacts BEP, followed by operational and financial performance.

Based on the above discussion, there is no study exploring GBP adoption in banking institutions in the ME’s developing countries. Thus, to fill this research gap and based on legitimacy theory, this study considered GBPs as an example of GAPs, which improve BEP. Therefore, the following hypothesis is postulated as detailed below:

H5:

GBP adoption positively and significantly impacts banks’ EP.

2.6. Green Finance and Banks’ Environmental Performance

Zhang et al. (2022) and Gulzar et al. (2024) referred to GF as an essential financial tool for harmonizing the country’s financial progress, environmental stability, ecological security, and sustainable economic growth. On the other hand, due to the banks’ financial role, they are responsible for potential negative environmental impacts if they fail to analyze clients’ environmental risk before financing various companies and industries (Shaumya & Arulrajah, 2017; Akter et al., 2018). Moreover, Zheng et al. (2021a) and Rehman et al. (2021) asserted that GF’s implementation helps banks to reduce their negative environmental impacts through financing numerous eco-friendly projects. Based on legitimacy theory, GF motivates firms to achieve environmental, social, and financial sustainability (Dai et al., 2022), avoid legitimacy gaps, and resolve social and environmental conflicts (Indriastuti & Chariri, 2021). The linkage between GF and companies’ EP was extensively explored in the literature (Indriastuti & Chariri, 2021; Awawdeh et al., 2022; Dai et al., 2022); however, there is still a lack of research pertaining to the banking industry. Few studies have illustrated the linkage between GF and BEP in developing countries (Zheng & Siddik, 2022; Gulzar et al., 2024), indicating positive and significant impacts on BEP, while others (Risal & Joshi, 2018; J. Chen et al., 2022) revealed insignificant impacts on BEP. According to these arguments, GF’s impact on BEP is still inconclusive. Also, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, it is the first study to demonstrate the relationship between GF and BEP in the ME region. Thus, based on legitimacy theory, this study considered GF as a new financial practice and one of the GAPs that improve BEP. Thus, the following hypothesis is postulated as presented below:

H6:

GF positively and significantly impacts banks’ EP.

2.7. Circular Economy Practices and Banks’ Environmental Performance

CE is a new economic approach aimed at preventing environmental degradation and reducing pollution and waste generation (Ali et al., 2022). Banks should engage in CE to promote socially and environmentally responsible behavior in the digital era (Ozili, 2021). Banks’ adoption of CEPs promotes the provision of new credit lines for circular projects, the creation of green banking, and the reduction in waste, pollution, and resource usage (Lamey et al., 2024). According to these arguments, there is no previous study that explored the association between CEPs and BEP in the ME’s developing countries. Thus, to fill this research gap and based on legitimacy theory, this study considered CEPs as one of the GAPs that improve BEP in the ME region. So, the following hypothesis is postulated as detailed below:

H7:

CEPs positively and significantly impact banks’ EP.

2.8. Mediating Role of Green Banking Practices, Green Finance, and Circular Economy Practices

Although fintech is a critical driver of BEP, its influence is not always direct (Tian et al., 2023). Based on reviewing the literature, there is still a dearth of literature illustrating indirect impacts of FA on BEP, which requires further investigation. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, prior research had not investigated the indirect effects of FA on BEP in the ME region considering the mediating role of GAP. Thus, the current study attempts to fill this gap by exploring the indirect impacts of FA on BEP, considering the mediating role of GBPs, GF, and CEPs based on legitimacy theory. As revealed by Wiredu et al. (2023) and M. S. Islam et al. (2023), GAPs are key prerequisites for enhancing the EP and SD’s achievement. Therefore, banks should adopt GAPs to enhance their EP and provide green financial products and services.

First, Zhang et al. (2022) indicated that BEP can be enhanced by involving GBPs into their internal operations. Udeagha and Muchapondwa (2023) and Serdarušić et al. (2024) stated that GBP adoption is focused on the FA level and revealed the necessity of creating a technologically adept banking industry that adopts new fintech solutions to promote GBPs and boost their EP. Moreover, Muganyi et al. (2021) confirmed that the combination of FA with GBPs helps the banks achieve higher levels of EP. Therefore, this study postulates the following:

H8:

The linkage between FA and banks’ EP is positively and significantly mediated by GBPs.

Second, FA can support the banks’ implementation of GF to enhance their EP as mentioned by Siddik et al. (2023c). BEP can be enhanced through FA, which facilitates the provision of funds for eco-friendly projects (Aslam & Jawaid, 2023; Muganyi et al., 2021). Moreover, Rehman et al. (2021) stated that banks’ GF is based on their level of FA. Serdarušić et al. (2024) and Liu et al. (2022) confirmed the GF’s positive impacts coupled with FA on BEP. Thus, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H9:

The linkage between FA and banks’ EP is positively and significantly mediated by GF.

Third, Siddik et al. (2023a) referred to FA’s role as one of I4.T in promoting CE CEPs adoption by offering real-time information about processes and resources and streamlining and providing diversified funding channels. Because banks are required to finance circular projects and provide funds to firms that intend to adopt CEPs, FA promotes the adoption of CE models through utilizing I4.0T (Ozili & Opene, 2021). Moreover, Lamey et al. (2024) illustrated the indirect relationship between FA and banks’ non-financial performance (NFP) with the mediating role of CEPs and found positive and significant influences between FA and CEPs and banks’ NFP. Moreover, CEPs significantly and positively mediate the linkage between FA and banks’ NFP. Therefore, this study postulates that FA indirectly impacts BEP through a transition toward CE models; consequently, the following hypothesis has been developed:

H10:

The linkage between FA and banks’ EP is positively and significantly mediated by CEPs.

The conceptual model is shown in Figure 1 as follows:

Figure 1.

The conceptual model (source: the authors).

3. Research Methodology

The research method, population, sample technique, and data collection methods are presented in this section. There is still a lack of understanding about FA’s impact on BEP, particularly in the ME region. Thus, Egypt, Iraq, Oman, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain were selected as the research setting in this study because, first, these Arab countries are highly susceptible to climate change and its associated environmental consequences, and on the other side, they are focusing on global climate finance to mitigate climate change impacts. Second, fintech, GBPs, GF, and CEPs are emerging rapidly in these countries to preserve the environment. Moreover, the critical motivations for conducting this study in the banking sector are as follows: first, the banks in Egypt (Hassouba, 2023), Oman (I. U. Khan et al., 2023), Jordan (Alkhazaleh & Haddad, 2021), Saudi Arabia (Al-Matari et al., 2023), Iraq (Neama et al., 2023), and Bahrain (Naser et al., 2024) are critical enablers for achieving economic growth and the SD of these countries; second, banking institutions are aware of environmental changes and are obligated to reduce carbon emissions through adopting eco-friendly technologies (Z. Chen et al., 2018); finally, the banks have a proactive role in financing diverse industries, motivating them to adopt green technologies and EMA systems before financing them (Rehman et al., 2021).

3.1. Research Design

This study intended to investigate FA’s impacts on BEP in the ME’s developing countries, considering GBPs, GF, and CEPs as mediating variables. Thus, a quantitative research approach was utilized due to its advantages, as mentioned by Serdarušić et al. (2024): first, this approach is suitable for collecting data from samples such as the banking industry and statistically evaluating the variables like FA, GBPs, GF, and CEPs; second, this approach promotes the validity of theories and hypotheses. According to the current study, the banks adopt GBPs, GF, and CEPs besides fintech solutions to enhance their EP and societal legitimacy. Thus, legitimacy and EM theories can be empirically tested.

3.2. Data Collection

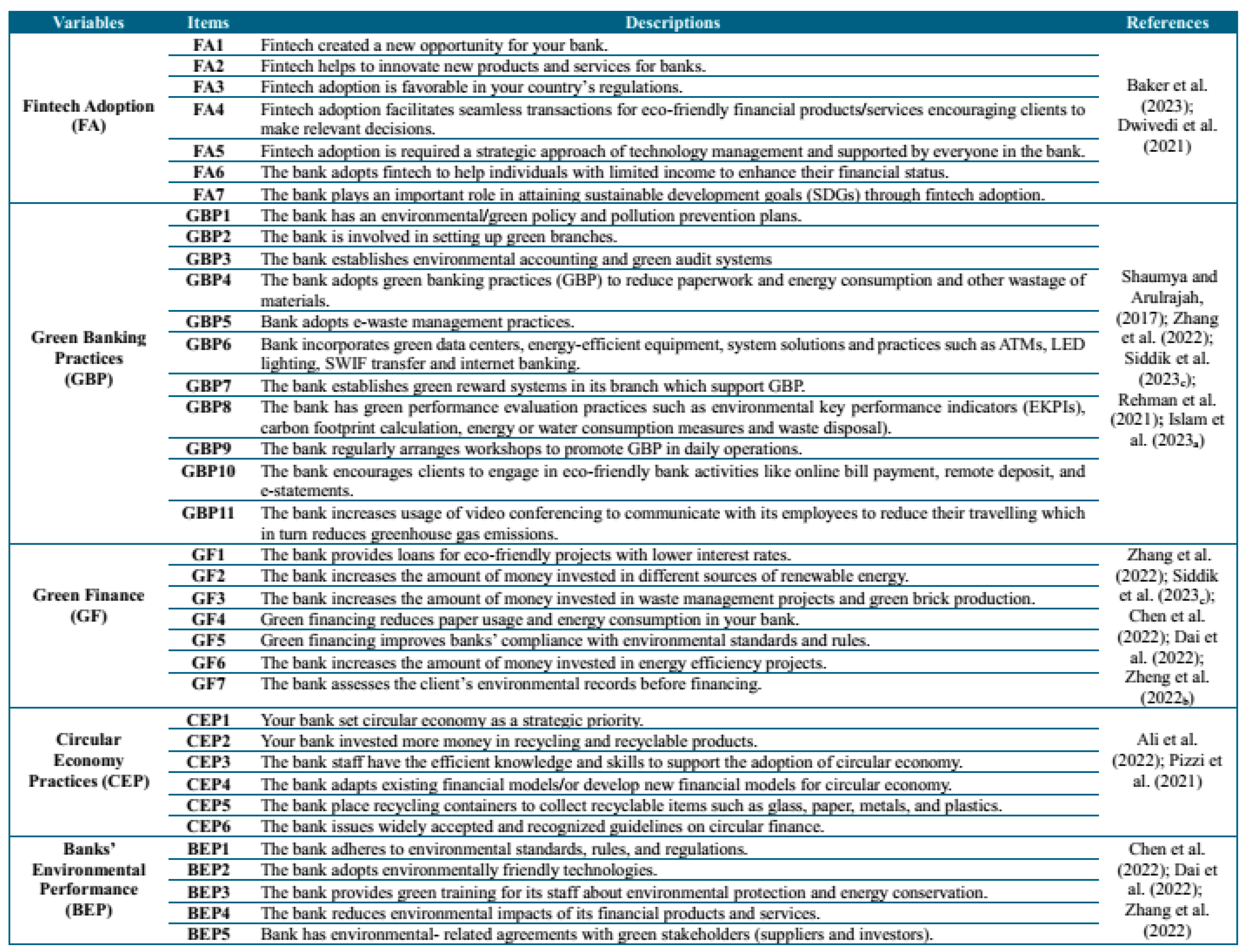

A self-structured questionnaire was designed based on the literature and pre-survey evaluation. The questionnaire was separated into two parts: Participants’ demographic information, such as age, gender, educational level, work position, and years of expertise in banks is presented in the first part. The second part covered the constructs’ items, which were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, within which 1 indicates strongly disagree and 5 indicates strongly agree. To confirm the measurement items’ reliability and validity, a pilot test was implemented among 25 experts who were chosen from bank managers, environmental specialists, academic professionals, and technologists who have sufficient knowledge about FA, GBPs, GF, CEPs and their importance to the banking sector. A few modifications were made according to pilot test results. The measurement items are presented in Appendix B.

3.3. Sampling Technique and Participants

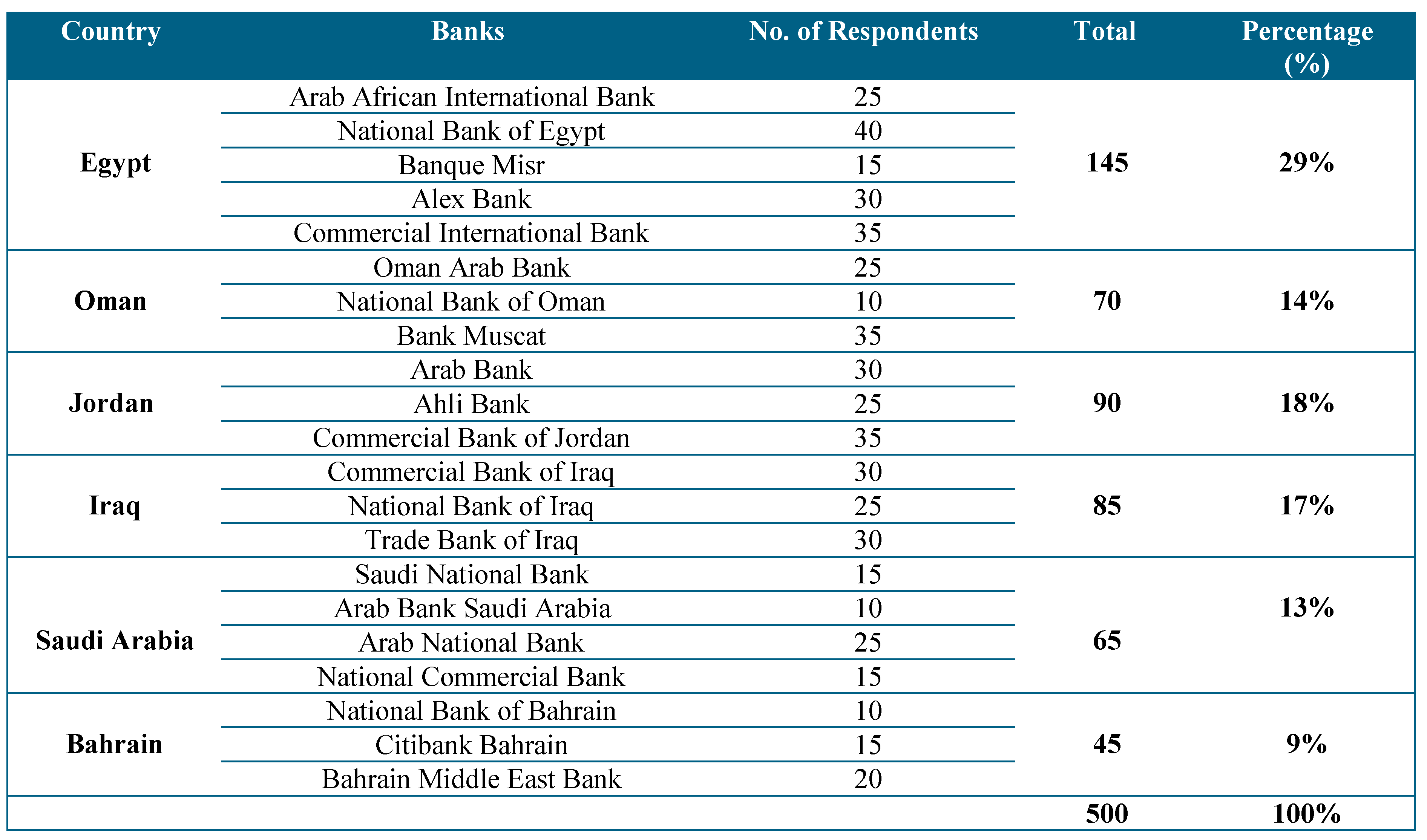

The primary data were collected from 500 members of staff from banks who occupied diverse positions and had sufficient expertise in commercial banks operating in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Iraq, Egypt, and Jordan in the ME region. The list of selected banks and participants is shown in Appendix C. Rehman et al. (2021) referred to the necessity of selecting bank staff in the data collection because their responses provide a comprehensive awareness of the banks’ strategies and performance indicators. This study was conducted in a real-world setting across 21 commercial banks operating in Egypt, Iraq, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Jordan, and a convenience sampling technique was used to choose the study participants based on some criteria as mentioned by Dai et al. (2022), such as the convenience of accessibility, geographic closeness, availability at a specific time, and desire to participate. The sample size was determined according to the 10 times sample rule, which is recommended by Hair et al. (2021), within which the maximum number of the survey’s measurement items used in the SEM technique was multiplied by 10. Consequently, the minimum number of participants required as a sample size was 360 because the 36 measurement items in the survey should have been initially addressed. Data was confidentially collected during the period from March 2024 to June 2024. A total of 950 surveys were distributed via WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and official e-mails to avoid a low response rate. Initially, 683 surveys were collected, out of which 208 were eliminated because of invalid responses. Thus, the actual sample size was 475, revealing a response rate of 69.5%.

3.4. Survey Instrument Development

The questionnaire items were extracted from the literature to assess the study variables such as FA, GBPs, GF, CEPs, and BEP. As shown in Appendix B, FA is the independent variable of this study and can be measured through 7 items that are derived from Dwivedi et al. (2021). Also, the dependent variable BEP was measured through 5 items adapted from (J. Chen et al., 2022; Dai et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). On the other hand, GBPs, GF, and CEPs were considered mediating variables in this study to explore whether these variables mediate the linkage between FA and BEP. Overall, 11 items were derived from (Shaumya & Arulrajah, 2017; Zhang et al., 2022; Siddik et al., 2023c; Rehman et al., 2021; M. S. Islam et al., 2023) to measure the GBP scale, 7 items were extracted from (Zhang et al., 2022; Siddik et al., 2023c; J. Chen et al., 2022; Dai et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2021a) to measure the GF scale, and the CEP scale was assessed through 6 items deriving from (Ali et al., 2022; Pizzi et al., 2021).

3.5. Data Analysis Technique

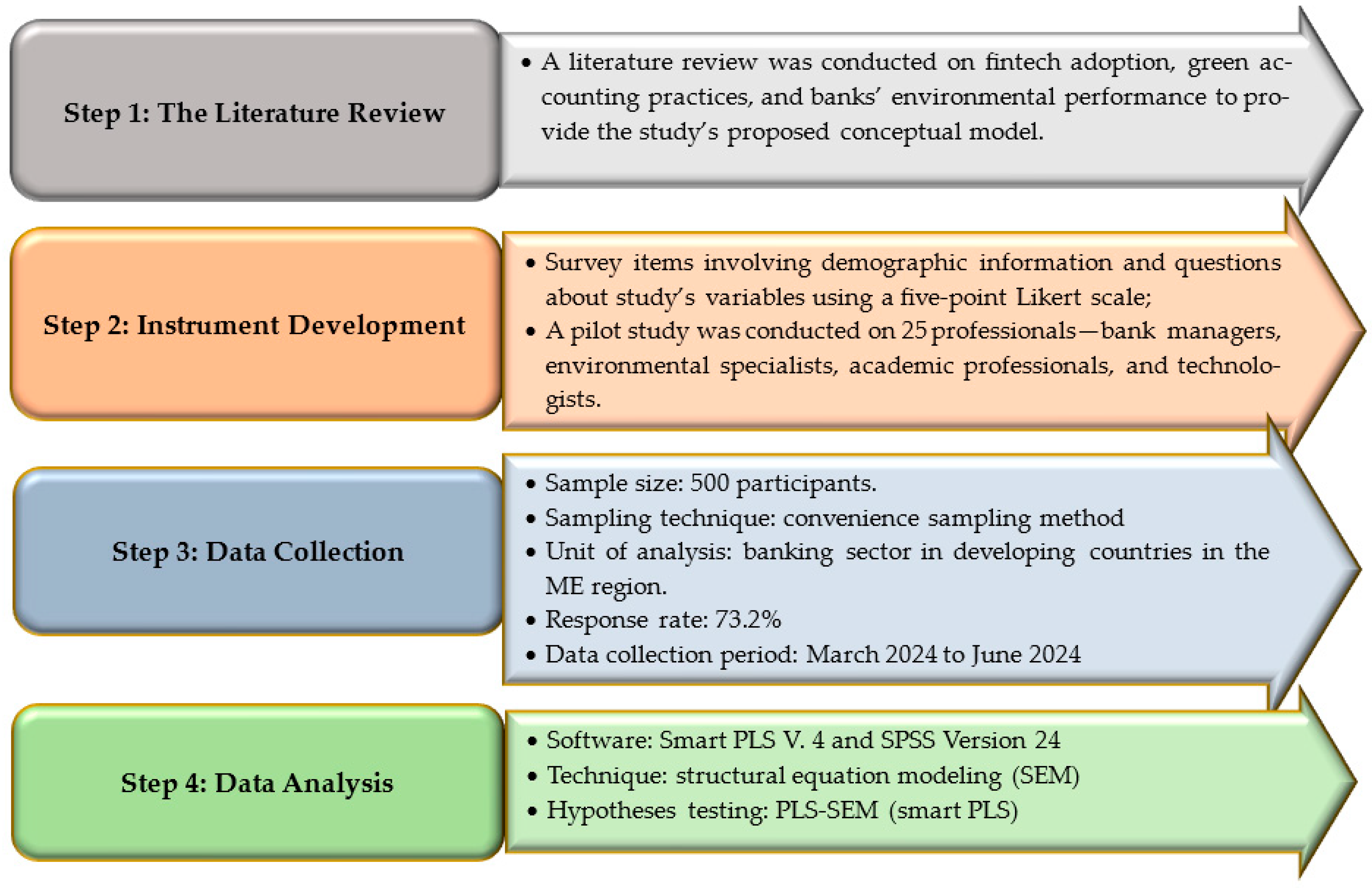

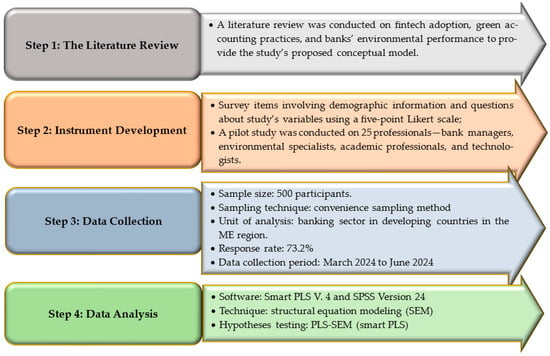

The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique (Smart PLS software version 4) and SPSS statistical analysis tools (version 24) were utilized for analyzing the data and testing the research hypotheses. SEM was used to evaluate the linkage between latent variables. As argued by Hair et al. (2021), SEM’s methodology and processing steps involve measurement and structural models. First, the relationship between the measured and latent constructs was determined in the measurement model. To assess the quality of variables, tests of reliability and validity were used. Reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR). Regarding the validity, it was assessed through establishing convergent and discriminant validity. Second, the structural model was conducted to investigate the interrelationships among latent variables. PLS-SEM is relevant for this study for many reasons. First, it is useful for handling complex models involving multiple latent and observed variables (Hair et al., 2021). Second, SEM is a powerful tool for testing complex cause–effect relationships among constructs. Third, this tool provides high levels of statistical significance with a small sample size (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Fourth, it can use data that do not have to be normally distributed (Hair et al., 2021). Fifth, measurement errors can be considered, and more accurate estimates for mediation effects can be provided than regression (Tawfik & Elmaasrawy, 2024). As this study investigates the mediating roles of GBPs, GF, and CEPs on the association between FA and BEP, the utilization of SEM is reasonable. As a result, Figure 2 represents the steps of the research methodology flowchart.

Figure 2.

Steps of research methodology’s flowchart (source: the authors).

4. Data Analysis and Results

There are three stages of data analysis: first, the analysis of participants’ demographic information; second, the assessment of the measurement model; and third, the structural model and hypotheses testing.

4.1. Demographic Information of Participants

Table 1 presents the participants’ demographic information and reveals that 73% and 27% were males and females, respectively. Regarding age, the majority (79%) of participants were between 30 and 40 years old and had operated in banks for more than 10 years (62.2%). Among the participants, 71.6% held a master’s degree, 15% held a bachelor’s degree, and only 8.4% had a Ph.D. degree. It can be noted that high educational levels support the banks to adopt fintech solutions, GBPs, GF, and CEPs to enhance their EP.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the participants (source: authors’ calculations).

Regarding the job positions held by the survey participants, 7.3% and 12.6% were employed as branch and assistant managers, respectively; 53.8% as accountants; 12.6% as financial analysts; 9.5% as loan officers; 2.1% as environmental managers; and 2.1% as others. Moreover, the majority (67.4%) of participants were accounting majors, followed by banking and finance (12.6%), management (8.4%), digitalization and technology (4.2%), and others (7.4%).

4.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

Assessment of the measurement model covers four tests, such as individual item reliability, internal consistency, and convergent and discriminant validity. The results of these tests are indicated in Table 2. First, factor loading of individual items ranges from 0.600 to 0.878, which exceeds the accepted value of 0.5 as recommended by Hair et al. (2021). Some items were removed from further exploration because of their lower factor loading, which was below 0.5, such as FA1 of the FA construct; GBP2, GBP4, GBP7, GBP8, GBP9, GBP10, GBP11 of the GBP construct; GF3, GF7 of the GF construct; CEP5, CEP6 of the CEP construct; and BEP5 of the BEP construct. Therefore, there are no reliability issues in the study’s individual items. Second, Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR) values were utilized to ascertain the constructs’ internal consistency. As recommended by Hair et al. (2021), CA and CR values must be above 0.7 to validate internal consistency, as also presented in Table 2, which indicates a strong internal consistency and reliability among each construct’s items. Thus, the study’s results can be trusted.

Table 2.

Findings of model validity and reliability tests (source: authors’ calculations).

Third, convergent validity (CV) can be verified by the average variance extracted (AVE). Table 2 indicates that the AVE values range from 0.510 to 0.666, which exceeds the recommended value of 0.5 as stated by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Therefore, this study confirms the CV criterion.

Fourth, Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criteria are used to evaluate the discriminant validity (DV). To assess DV, the square root of each construct’s AVE value should be above its correlation with other constructs. The values of the square root of AVE ranged from 0.759 to 0.801, which exceed their correlations with another construct as indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity test: Fornell–Larcker criterion (source: authors’ calculations).

Finally, the multicollinearity issue is assessed through the variance inflation factor (VIF), which must be less than 5 as recommended by Hair et al. (2021). Table 2 reveals that all constructs’ VIF values are below 5, which ascertains the absence of a multicollinearity issue among constructs.

4.3. Structural Equation Model and Hypotheses Testing

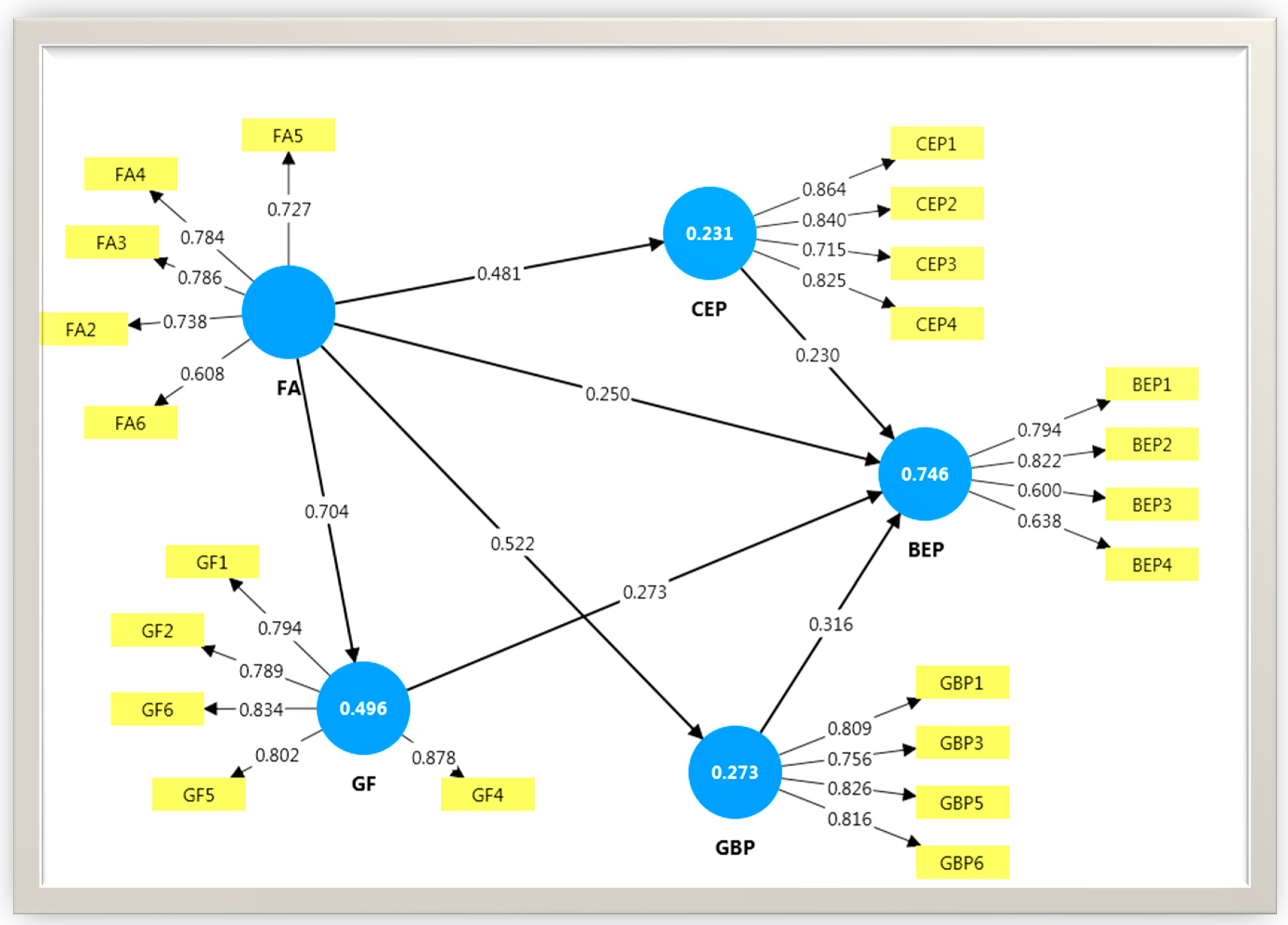

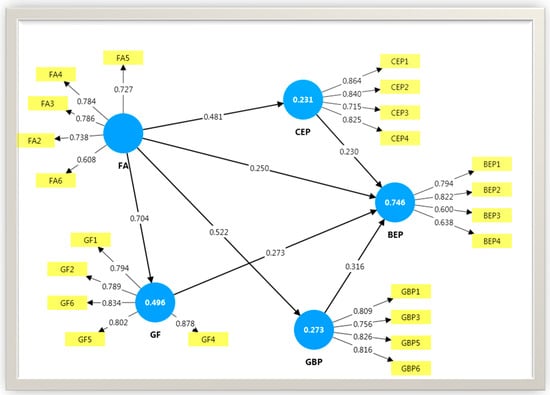

After the assessment of the measurement model, the hypotheses are tested using SEM as presented in Figure 3. Some conditions must be satisfied to accept the proposed hypotheses as mentioned by Hayes (2009). First, direct influence has a significant effect. Second, the direct effect’s path coefficient should be within the confidence interval. Third, the confidence interval should not contain zero. The findings of the hypotheses testing are presented in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Structural model’s findings (source: the authors).

Table 4.

Findings of hypotheses testing (source: authors’ calculations).

The hypotheses are validated if the t-value is above 1.96 or the p-value is below 0.05 and vice versa. Ten hypotheses are tested in this study, and the findings are indicated in Table 4.

On the other hand, the model’s predictive relevance is assessed through computing R-Square (R2) and adjusted R-Square values as stated by Hair et al. (2021) and Elmaasrawy et al. (2024). As revealed in Table 5, all R2 values are more than 0.10, which validates the predictive ability of the model’s constructs.

Table 5.

Coefficient of determination (R2) (source: authors’ calculations).

Moreover, the effect size (f2) of each path coefficient is computed to illustrate the extent to which independent variables influence the dependent variable, as indicated in Table 6. As guided by Cohen (2013) and Tawfik and Elmaasrawy (2024), the effect size is considered large, moderate, and small when f2 values are more than 0.3, 0.15, and 0.02, respectively.

Table 6.

Each path coefficient effect size (f2) (source: authors’ calculations).

5. Discussion and Results

Recently, FA, GBPs, GF, and CEPs have gained significant importance in developed and developing countries due to the rapid expansion of technological innovations and unstable economic circumstances (Zhang et al., 2022). However, a few studies explored FA’s impacts on banks’ performance, especially in developing countries (Zheng & Siddik, 2023; Bouheni et al., 2023; Lamey et al., 2024). Consequently, this is the first study that addressed this research gap through empirically exploring FA’s impacts, considering the mediating role of GBPs, GF, and CEPs as examples of GAPs on BEP in the ME region.

The study’s empirical results confirmed the EMT’s proposition by offering empirical evidence on FA’s role in improving BEP (Zheng & Siddik, 2023). It was revealed that BEP is positively and significantly influenced by FA (β = 0.250, p-value = 0.049, f2 = 0.112 small, and confidence interval “0.051, 0.541” does not include 0) as shown in Figure 3 and Table 4. This finding aligned with the results of Muganyi et al. (2021) and Awawdeh et al. (2022), which revealed that FA can boost BEP through adopting eco-friendly digital technologies and practices, reducing carbon emissions, and enhancing resource efficiency; thus, H1 is accepted. Furthermore, this study formulated hypotheses relating to FA’s impacts on GBPs, GF, and CEPs. First, the empirical results confirmed the validity of H2, indicating that GBPs are positively and significantly impacted by FA (β = 0.522, p-value = 0.000, f2 = 0.375 large, and confidence interval “0.314, 0.749” does not include 0). This finding is akin to prior research (Vergara & Agudo, 2021; Naz et al., 2023), which demonstrated that banks’ FA can promote GBPs such as branchless banking, paperless storage, and video conferences. Second, the findings indicated that banks’ GF is positively and significantly influenced by FA (β = 0.704, p-value = 0.000, f2 = 0.983 large, and confidence interval “0.532, 0.844” does not include 0), implying that FA has a crucial role in promoting GF by utilizing digital technologies such as AI, BDA, and blockchain, which is consistent with Yan et al. (2022). Also, this finding corroborated with the results of Tian et al. (2023) and Serdarušić et al. (2024) that revealed FA’s role in mobilizing GF by streamlining new financial and investment paths; thereby, H3 is supported. Third, Pizzi et al. (2021) and Siddik et al. (2023a) mentioned the crucial role of FA in promoting CEPs. The study’s results confirmed that CEPs are positively and significantly affected by FA (β = 0.481, p-value = 0.000, f2 = 0.301 large, and confidence interval “0.218, 0.708” does not include 0), thus H4 is validated. This finding is also consistent with the findings of Bag and Pretorius (2020) and Ali et al. (2022), which revealed that FA accelerates banks’ adoption of CEPs by adopting digital financial technologies and facilitating financial resource accessibility.

On the other hand, this study investigated the impacts of GBPs, GF, and CEPs on BEP based on legitimacy theory and revealed that these practices help the banks to demonstrate their commitment toward society and the environment to maintain their societal legitimacy. This study’s empirical results asserted legitimacy theory and indicated a positive and significant relationship between GBPs, GF, CEPs, and BEP. GBPs positively and significantly influence BEP (β = 0.316, p-value = 0.018, f2 = 0.25 moderate, and confidence interval “0.038, 0.507” does not include 0), thus H5 is accepted. This result is corroborated by the results of Zhang et al. (2022), Aslam and Jawaid (2023), I. U. Khan et al. (2023), and Gulzar et al. (2024), which indicated that GBPs enhance BEP through reducing resource usage, the efficient utilization of digital file processing, offering environmental training to bank staff, and reducing carbon emissions. Regarding GF, the empirical findings revealed that GF is considered a strategy that supports banks to maintain their legitimacy through aligning their strategies and policies with community values. This finding demonstrated the soundness of H6, verifying that banks’ involvement and participation in GF has positive and significant effects on their EP (β = 0.273, p-value = 0.047, f2 = 0.126 small, and confidence interval “0.066, 0.639” does not include 0). This result is aligned with the findings of Yan et al. (2022), Zheng and Siddik (2023), Dai et al. (2022), and Zhang et al. (2022) revealing that GF significantly enhances BEP by financing several environmentally friendly projects. However, this finding does not agree with the findings of Risal and Joshi (2018) and Shaumya and Arulrajah (2017), which revealed an insignificant relationship between GF and BEP. According to the study’s findings, GF is a key enabler for green growth acceleration and the promotion of social and environmental responsibilities. Moreover, the results revealed a positive and significant linkage between CEPs and BEP (β = 0.230, p-value = 0.049, f2 = 0.144 small, and confidence interval “0.022, 0.488” does not include 0), thereby, H7 is confirmed. Although this is a pioneering study that attempts to investigate the association between CEPs and BEP in the ME’s developing countries, a few scholars have demonstrated that banks’ transformation toward CE models promotes new credit lines for circular projects, creating green banking and promoting a reduction in waste, pollution, and resource usage (Lamey et al., 2024; Ali et al., 2022).

Finally, mediation relationships have been explored in this study and are summarized in Table 7. GBPs, GF, and CEPs are examples of GAPs and considered as mediators of the linkage of FA and BEP. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is a pioneering study that explores the mediating impacts of GAPs on the linkage between FA and BEP in the ME region. It was noted that BEP was positively and significantly influenced by GBPs, GF, and CEPs (β = 0.165, p-value = 0.039, and confidence interval “0.019, 0.302” does not include 0), (β = 0.192, p-value = 0.044, and confidence interval “0.061, 0.428” does not include 0), and (β = 0.110, p-value = 0.049, and confidence interval “0.013, 0.218” does not include 0), respectively. This finding concluded that FA influences BEP both directly and indirectly. Therefore, FA can promote GBPs, GF, and CEPs, which consequently enhance BEP. These findings are corroborated with the findings of prior studies indicating that the linkage between FA and BEP is significantly mediated by GBPs (Serdarušić et al., 2024; Naz et al., 2023; Muganyi et al., 2021) and GF (Zheng & Siddik, 2023; Yan et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Also, the findings revealed a significant mediation impact of CEPs on the linkage between FA and BEP but there is no supportive literature for this finding because no prior research has investigated this mediation relationship.

Table 7.

Mediating roles of GBPs, GF, and CEPs on linkage between FA and BEP (source: the authors).

6. Conclusions

Recently, the banking sector’s contribution to environmental preservation has received significant attention. Although the banking sector is not considered a polluting sector, it may have adverse impacts on the environment through its internal operations and by financing the most polluting industries (Aslam & Jawaid, 2023). I. U. Khan et al. (2023) confirmed that banks are required to be pro-environmental institutions through adopting the most innovative and technological practices, like fintech solutions, to make financial transactions more secure and accessible. According to the literature review, there is still a scarcity in the literature about FA’s effects on BEP, particularly in the developing countries of the ME region. To address this gap, the current study illustrated FA’s impacts on BEP, considering the mediating role of GBPs, GF, and CEPs based on EMT and legitimacy theories in the context of the ME region.

Therefore, this study fills the literature gap on FA and GAPs (GBPs, GF, and CEPs) from the banking sector’s perspective. Moreover, the study’s results provide valuable theoretical, practical, and social implications for academics, bank managers, policy makers, and regulators in developing countries.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The study provides valuable theoretical implications in terms of the existing literature. First, the results contribute to the banking sector field in the ME region and expand EMT’s scope through investigating FA’s impacts on BEP. EMT posits that negative environmental impacts of banks’ operations can be mitigated through FA (Dai et al., 2022), and the results ascertained the positive and significant effects of FA on GBPs, GF, CEPs, and BEP, which is a significant theoretical contribution to the literature. Second, the empirical results verified and expanded the legitimacy theory’s scope through exploring the direct impacts of GBPs, GF, and CEPs on BEP. Indriastuti and Chariri (2021) stated that the adoption of these practices can boost BEP and help the banks to maintain their societal legitimacy and attain long-term sustainable growth. Third, prior research explored the direct impacts of GBPs (Zhang et al., 2022), GF (Siddik et al., 2023c; Zheng et al., 2021a, 2021b), and CEPs (Lamey et al., 2024) on banks’ performance independently, ignoring their mediating roles. Given this research gap, this is the first study that investigates GBPs, GF, and CEPs as mediators simultaneously, which is another theoretical contribution to the literature. Fourth, the proposed conceptual model can be applied in other developing or developed countries in other regions. Therefore, this study can be replicated in the future because the measurement scales are verified by utilizing statistical analyzing techniques like SEM.

6.2. Practical Implications

The study’s empirical results present some noteworthy practical implications for bank managers, policy makers, and regulators. Regarding bank managers, first, the bank managers are recommended to provide their staff with training programs to raise their awareness about FA, GAPs, and their impacts on BEP; second, this is the first study that considers the interplay among FA, GAPs, and BEP in a unified conceptual model, which is considered a reference guide for bank managers; third, according to legitimacy theory, the findings indicated the significant and positive impacts of GBPs, GF, and CEPs on BEP. Therefore, bank managers should deploy more investments in eco-friendly practices such as FA and GAPs to enhance their EP and maintain societal legitimacy. Regarding policy makers and regulators, the developing countries’ governments should take proactive measures to prevent environmental degradation by setting environmental regulations that can be categorized into the following forms: (a) mandatory environmental regulations are laws and regulations enacted by executive authorities to enforce the banks to comply with adopting eco-friendly initiatives and technologies; (b) market-based environmental regulations can be utilized by the government to encourage the banks to adopt fintech and GAPs to reduce their negative environmental impacts through providing tax-free incentives or subsidies. Moreover, the government, fintech firms, and banking authorities should cooperate, as recommended also by Ashta (2023), to organize seminars and educational training to raise the awareness of banks’ clients and the public about financial technologies and various GAPs. Finally, each country’s laws and regulations should prioritize FA localization based on its capabilities and goals. Additionally, policy makers should enforce all listed banks to disclose their FA, GBP, GF, and CEP strategies in their financial reports to raise their stakeholders’ awareness. On the other hand, the study’s findings provide some valuable social implications. First, based on the study’s findings, the banking institutions, government, and international organizations should cooperate to promote FA and GAPs that boost EP. Second, this study can promote FA and GAPs in a socially responsible way, which enables society to become familiar with green practices and involves such norms in the local community. Third, the banks act as a guardian and mediator toward economic transition and provide several opportunities for eco-friendly investments to achieve a low-carbon economy.

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Although this study offers valuable theoretical and practical implications, there are some limitations. First, this study is based on the banking sector in the ME region, which has unique cultural aspects that may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Thus, it is recommended to conduct comparable studies in other sectors and countries to expand the results’ application and provide a more reliable conclusion. Second, primary data were collected from the banks’ internal stakeholders, which may also limit the findings’ generalizability. Thus, it is recommended to replicate this study to assess the opinions of external stakeholders such as clients to observe the results’ changes. Also, it is recommended to use secondary data in the future to validate the studies’ results. Third, the sampling technique used is considered another limitation. Although the convenience sampling technique is practical and time-efficient, it is not as representative as judgment sampling, which may limit the findings generalizability. Thus, it is recommended to utilize other sampling techniques in the future to further validate the current results. Fourth, this study only explored the mediating role of GBPs, GF, and CEPs on the linkage between FA and BEP. Therefore, we call for further empirical exploration of other mediators like financial literacy, corporate social responsibility, GI, or other moderating variables such as bank size, capital structure, gender, or governmental regulation. Finally, a cross-sectional technique is utilized due to the limitation of time and resources. As a result, it is uncertain whether FA, GBPs, GF, and CEPs in the banks provide similar results over time. Therefore, a longitudinal research approach could be conducted in the future to observe if the results change or remain constant over time.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation: Y.M.L.B. Methodology: H.E.E. data curation: O.I.T. Writing—Reviewing and Editing: M.I.S. and M.A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Department of the Research Ethics Committee of Dhofar University and approved under Reference Number (DU/AY/2024-25/QUES-054). Due to the revisions performed, the study’s title was slightly modified without altering the objectives, methodology, or ethical considerations; thus, the original ethical approval remains applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participants was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. All participants were fully informed of their anonymity, the purpose of the research, and that their data would be used only for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the academic editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful and insightful remarks and recommendations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Summary of the Literature Review (Source: The Authors)

Appendix B. Measurement Items (Source: The Authors)

Appendix C. List of Banks and Participants (Source: The Authors)

References

- Akter, N., Siddik, A. B., & Mondal, S. A. (2018). Sustainability reporting on green financing: A study of listed private commercial banks in Bangladesh. Journal of Business and Technology, 12, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Al Doghan, M. A., & Chong, K. W. (2023). Fintech adoption and environmental sustainability: Mediating role of green finance, investment and innovation. International Journal of Operations and Quantitative Management, 29(2), 296–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Q., Parveen, S., Yaacob, H., Rani, A. N., & Zaini, Z. (2022). Environmental beliefs and the adoption of circular economy among bank managers: Do gender, age and knowledge act as the moderators? Journal of Cleaner Production, 361, 132276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhazaleh, A. M. K., & Haddad, H. (2021). How does the Fintech services delivery affect customer satisfaction: A scenario of Jordanian banking sector. Strategic Change, 30(4), 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matari, E. M., Mgammal, M. H., Senan, N. a. M., Kamardin, H., & Alruwaili, T. F. (2023). Fintech and financial sector performance in Saudi Arabia: An empirical study. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 12(2), 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashta, A. (2023). How can Fintech companies get involved in the environment? Sustainability, 15(13), 10675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, W., & Jawaid, S. T. (2023). Green banking adoption practices: Improving environmental, financial, and operational performance. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 39(4), 820–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awawdeh, A. E., Ananzeh, M., El-Khateeb, A. I., & Aljumah, A. (2022). Role of green financing and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in technological innovation and corporate environmental performance: A COVID-19 perspective. China Finance Review International, 12(2), 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S., & Pretorius, J. H. C. (2020). Relationships between industry 4.0, sustainable manufacturing and circular economy: Proposal of a research framework. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 30(4), 864–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouheni, F. B., Tewari, M., Sidaoui, M., & Hasnaoui, A. (2023). An econometric understanding of Fintech and operating performance. Review of Accounting and Finance, 22(3), 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Siddik, A., Zheng, G., Masukujjaman, M., & Bekhzod, S. (2022). The Effect of green banking practices on banks’ environmental performance and green financing: An empirical study. Energies, 15(4), 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. H., You, X., & Chang, V. (2021). FinTech and commercial banks’ performance in China: A leap forward or survival of the fittest? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Hossen, M. M., Muzafary, S. S., & Begum, M. (2018). Green banking for environmental sustainability-present status and future agenda: Experience from Bangladesh. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 8(5), 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X., Siddik, A. B., & Tian, H. (2022). Corporate social responsibility, green finance and environmental performance: Does green innovation matter? Sustainability, 14(20), 13607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, B. C., Saha, S., & Rahman, M. M. (2020). Does green accounting practice affect bank performance? A study on listed banks of Dhaka stock exchange in Bangladesh. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt, 17(9), 7225–7247. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, P., Alabdooli, J. I., & Dwivedi, R. (2021). Role of fintech adoption for competitiveness and performance of the Bank: A study of banking industry in UAE. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 16(2), 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaasrawy, H. E., Tawfik, O. I., & Abdul-Rahaman, A. (2024). Effect of audit client’s use of blockchain technology on auditing accounting estimates: Evidence from the Middle East. Journal of Financial Reporting & Accounting, 23(2), 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, H. M. (2023). A review of literature directions regarding the impact of fintech firms on the banking industry. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 15(5), 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSB. (2017). Financial stability implications from Fintech. Financial Stability Board. Available online: https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/R270617.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2017).

- Gulzar, R., Bhat, A. A., Mir, A. A., Athari, S. A., & Al Adwan, A. S. (2024). Correction to: Green banking practices and environmental performance: Navigating sustainability in banks. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 31(15), 23227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, A. N., Lee, K., & Kaluarachchilage, P. K. H. (2021). Institutional pressures, environmental management strategy, and organizational performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hassouba, T. A. (2023). Financial inclusion in Egypt: The road ahead. Review of Economic and Political Science, 10(2), 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the New Millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, S. (2005). Modern banking. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Indriastuti, M., & Chariri, A. (2021). The role of green investment and corporate social responsibility investment on sustainable performance. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1960120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. S., Rubel, M. R. B., & Hasan, M. M. (2023). Environmental and social performance of the banking industry in Bangladesh: Effect of stakeholders’ pressure and green practice adoption. Sustainability, 15(11), 8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S., Islam, M. S., Hassan, M. R., Arafat, A. B. M. Y., Ahmed, S., Hoque, S., & Sultana, T. (2023). Evaluating the success of green accounting practices in the banking sector of Bangladesh. International Journal of Applied Economics Finance and Accounting, 17(2), 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I. U., Hameed, Z., Khan, S. U., & Khan, M. A. (2023). Green banking practices, bank reputation, and environmental awareness: Evidence from Islamic banks in a developing economy. Environment Development and Sustainability, 26(6), 16073–16093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., & Gupta, S. (2023). The interplay of sustainability, corporate green accounting and firm financial performance: A meta-analytical investigation. Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal, 15(5), 1038–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, H., Trichilli, Y., & Abbes, B. (2023). Relationship between FinTech index and bank’s performance: A comparative study between Islamic and conventional banks in the MENA region. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 15(1), 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ky, S. S., Rugemintwari, C., & Sauviat, A. (2019). Is fintech good for bank performance? The case of mobile money in the East African community. Social Science Research Network, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamey, Y. M., Tawfik, O. I., Durrah, O., & Elmaasrawy, H. E. (2024). Fintech adoption and banks’ non-financial performance: Do circular economy practices matter? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Jiang, Y., Gan, S., He, L., & Zhang, Q. (2022). Can digital finance promote corporate green innovation? Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(24), 35828–35840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A. A., & Bhat, A. A. (2022). Green banking and sustainability—A review. Arab Gulf Journal of Scientific Research, 40(3), 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muganyi, T., Yan, L., & Sun, H. (2021). Green finance, fintech and environmental protection: Evidence from China. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, 7, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, H., Sultanova, G., & Nahar, S. (2024). The impact of Fintech innovation on bank’s performance: Evidence from the Kingdom of Bahrain. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 14(1), 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S., Asif, M., & Hameed, S. (2023). Fintech’s role in sustainable banking performance: Are green banking policies driving sustainability in Pakistan’s banking system? Gomal University Journal of Research, 39(3), 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neama, N. H., Abbood, R. H., & Aref, S. a. S. (2023). Financial technology and its role in Iraqi banking industry (analyzing study for selected private banks of Iraq). Open Journal of Business and Management, 11(4), 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarini, A. E. (2018). Banks and Fintechs: How to develop a digital open banking approach for the bank’s future. International Business Research, 11(9), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2021). Circular economy, banks, and other financial institutions: What’s in it for them? Circular Economy and Sustainability, 1(3), 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K., & Opene, F. (2021). The role of banks in the circular economy. Social Science Research Network, 19(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S., Corbo, L., & Caputo, A. (2021). Fintech and SMEs sustainable business models: Reflections and considerations for a circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 281, 125217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A., Ullah, I., Afridi, F., Ullah, Z., Zeeshan, M., Hussain, A., & Rahman, H. U. (2021). Adoption of green banking practices and environmental performance in Pakistan: A demonstration of structural equation modelling. Environment Development and Sustainability, 23(9), 13200–13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risal, N., & Joshi, S. K. (2018). Measuring green banking practices on bank’s environmental performance: Empirical evidence from Kathmandu valley. Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 1(1), 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdarušić, H., Pancić, M., & Zavišić, Ž. (2024). Green finance and fintech adoption services among croatian online users: How digital transformation and digital awareness increase banking sustainability. Economies, 12(3), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaumya, S., & Arulrajah, A. (2017). The impact of green banking practices on bank’s environmental performance: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Journal of Finance and Bank Management, 5(1), 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, A. B., Li, Y., & Rahman, M. N. (2023a). The role of Fintech in circular economy practices to improve sustainability performance: A two-staged SEM-ANN approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(49), 107465–107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddik, A. B., Rahman, M. N., & Li, Y. (2023b). Do fintech adoption and financial literacy improve corporate sustainability performance? The mediating role of access to finance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 421, 137658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, A. B., Yong, L., & Sharif, A. (2023c). Do sustainable banking practices enhance the sustainability performance of banking institutions? Direct and indirect effects. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 42(4), 672–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, O. I., & Elmaasrawy, H. E. (2024). Determinants of the quality of tax audits for content creation tax and tax compliance: Evidence from Egypt. SAGE Open, 14(1), 21582440241227755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H., Siddik, A. B., Pertheban, T. R., & Rahman, M. N. (2023). Does fintech innovation and green transformational leadership improve green innovation and corporate environmental performance? A hybrid SEM–ANN approach. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(3), 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, A., Najaf, K., Dhiaf, M. M., Li, N. S., & Kanagasabapathy, S. (2023). The role of Fintech firms’ sustainability during the COVID-19 period. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(20), 58855–58865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udeagha, M. C., & Muchapondwa, E. (2023). Green finance, fintech, and environmental sustainability: Fresh policy insights from the BRICS nations. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 30(6), 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, C. C., & Agudo, L. F. (2021). Fintech and sustainability: Do they affect each other? Sustainability, 13(13), 7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S., Lee, Y. H., & Sarma, V. J. (2023). Is Fintech good for green finance? Empirical evidence from listed banks in China. Economic Analysis and Policy, 80, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiredu, I., Agyemang, A. O., & Agbadzidah, S. Y. (2023). Does green accounting influences ecological sustainability? Evidence from a developing economy. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2240559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C., Siddik, A. B., Akter, N., & Dong, Q. (2023). Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of FinTech. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(22), 61271–61289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C., Siddik, A. B., Li, Y., Dong, Q., Zheng, G., & Rahman, M. N. (2022). A two-staged SEM-Artificial neural network approach to analyze the impact of FinTech adoption on the sustainability performance of banking firms: The mediating effect of green finance and innovation. Systems, 10(5), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Wang, Z., Zhong, X., Yang, S., & Siddik, A. B. (2022). Do green banking activities improve the banks’ environmental performance? The mediating effect of green financing. Sustainability, 14(2), 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W., & Siddik, A. B. (2022). Do corporate social responsibility practices and green finance dimensions determine environmental performance? An Empirical study on Bangladeshi banking institutions. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 890096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W., & Siddik, A. B. (2023). The effect of Fintech adoption on green finance and environmental performance of banking institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of green innovation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(10), 25959–25971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W., Siddik, A. B., Masukujjaman, M., & Fatema, N. (2021a). Factors affecting the sustainability performance of financial institutions in Bangladesh: The role of Green Finance. Sustainability, 13(18), 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W., Siddik, A. B., Masukujjaman, M., Fatema, N., & Alam, S. S. (2021b). Green finance development in Bangladesh: The role of Private Commercial Banks (PCBs). Sustainability, 13(2), 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).