Abstract

Elderly individuals who need the support of others may be subjected to abuse in managing their budgets and financial decisions. This situation is explained as financial exploitation, which is a subtype of elder abuse. The main purpose of this study is to evaluate the participants’ financial decision-making skills and their exposure to financial exploitation. In this study, which was designed according to qualitative research design, data were collected through semi-structured interview forms. The collected data were analyzed by creating themes according to the general framework coding method. The results of the study reveal that the participants receive help from their children in financial decision-making and that their children generally manage their budgets. Moreover, although the income levels of the participants are generally quite low, it is seen that they are exposed to financial exploitation by their families and people in their immediate vicinity.

1. Introduction

With advancing technology and health developments, human life expectancy has increased worldwide. The World Health Organization projects the population aged 60 and over will reach 2.1 billion by 2050. In 2017, one in eight people globally was over 60; by 2030, it will be one in six, and by 2050, one in five. Eighty percent of this population will live in less developed countries (UN Decade of Healthy Ageing: Plan of Action 2021–2030). Although developed countries have a higher ratio of elderly populations, developing countries, including Türkiye, are seeing increases too (OECD, 2023).

According to the “Elderly Statistics (2023)” report by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK), Türkiye’s elderly population increased by 21.4% over the past five years. The elderly population ratio was 8.8% in 2018, rising to 10.2% in 2023, placing Türkiye 67th among 184 countries. This ratio is expected to reach 12.9% by 2030, 16.3% by 2040, and 25.6% by 2080 (TÜİK, 2023).

The increasing global elderly population and the aging process have become focal points for many studies. Aging involves interdisciplinary components and plays a crucial role in identifying individual needs and determining social policies of the welfare state concerning human rights. Thus, it is essential to define aging across geriatric, sociological, economic, political, and cultural dimensions and support societies in managing old age. The Lifespan Development Theory is one approach highlighting these needs.

The Lifespan Development Theory posits development occurs through biological, socio-cultural, and personal factors. Development is lifelong, with each life stage having unique processes. It is multidimensional and multidirectional, exhibiting different characteristics based on life stages and individual needs. Development is also flexible and contextual, with the ability to maintain certain skills in later life stages being crucial. All development occurs within contexts such as family, peer groups, neighborhoods, or cities (Santrock, 2011, pp. 6–9). Thus, the new needs and problems arising from the “old age” stage become apparent both cognitively and developmentally. Hence, such a process is related with the concept of successful aging. Successful aging, as a natural progression of lifespan development and adaptation (P. B. Baltes & Baltes, 2010), is defined as a process of individual adaptive human development across the entire lifespan identified by the control of internal and external resources; that is, the relative escalation and accomplishment of gains (e.g., positive or desired outcomes) and the avoidance of losses (e.g., negative or undesired outcomes) (P. B. Baltes et al., 1999; Ommensen et al., 2025) as mentioned below.

With the increasing average life expectancy and the rise in the elderly population, numerous challenges emerge. As life progresses, aging brings various negative changes to our bodies, behaviors, emotions, and relationships. Key characteristics observed in physiological, cognitive, sensory, socio-emotional, and behavioral dimensions during old age include the following (Arpacı, 2005; Komşu, 2023; Macnicol, 2005):

- -

- Decline in basic senses;

- -

- Changes and deterioration in muscle and skeletal structure, and in basic systems (hormonal, digestive, respiratory, circulatory, immune);

- -

- Weakening of reflexes and motor coordination;

- -

- Slowing and delay in learning processes;

- -

- Cognitive declines due to brain structure changes (attention deficits, concentration impairments, memory decline, language skill deterioration);

- -

- Persistent sadness and depressive states.

These age-related characteristics lead to various problems for elderly individuals and their societal environment. Physical, social changes, and economic difficulties increase their need for support. Elderly individuals needing assistance are at high risk of abuse, which has serious consequences for victims, families, and society (Conrad et al., 2011). Cultural attitudes towards aging can have both positive and negative effects. Agism, or prejudices against aging, can cause social exclusion and decreased life satisfaction, leading to isolation. Additionally, neglect of elderly developmental needs (like new learning activities and economic pursuits) in social policies, combined with age discrimination, increases vulnerability to abuse (Arpacı et al., 2022; Komşu, 2023).

With the increasing elderly population, the problems faced by the elderly are becoming more pronounced. In developed countries, social security and social services help maintain social welfare standards for the elderly. However, in developing countries like Türkiye, new policies and practices lag behind the demographic aging rate. The growth rate of the population aged 60 years and above is about three times faster in less developed countries than in more developed countries. A faster growing elderly population in developing countries is going to face deepening crises in social security and pension, health care financing and provision, and long-term care. Many populous developing countries have very large elderly population although they are not efficiently prepared like the developed countries (Mondal, 2021). As Longman (2004) noted, many developed countries became enriched before their populations aged, while developing countries are aging without becoming enriched. Therefore, the elderly in developing countries face economic poverty and social loneliness more severely (Danış, 2009). Social isolation and loneliness can lead to abuse as individuals struggle to meet basic needs and ensure personal and property safety.

Elder abuse can be categorized as physical abuse (coercion, pain, injury, restriction), psychological and emotional abuse (mental pain), financial exploitation (illegal use of funds/resources), sexual abuse (non-consensual contact), and neglect (failure or refusal to care) (World Health Organization (WHO), 2002; National Center on Elder Abuse, 2006; Anthony et al., 2009; Patel et al., 2021). Despite regional differences, elder abuse is generally increasing. Studies show that 1 in 10 elderly in the USA is abused, although exact figures are unclear. Physical abuse is easier to detect, while psychological abuse and financial exploitation are harder to identify. The abuser is often a family member, complicating victims’ ability to report abuse (American Medical Association, 1987; Mukherjee, 2013; Nursing Home Abuse Center, 2020; Patel et al., 2021).

As the Lifespan Development Theory discusses, lifelong development continues into old age, necessitating ongoing economic and financial support. Financial decisions should be made with sufficient knowledge and skills. Likewise, stopping economic productivity does not mean ceasing the use of goods and money. Due to age-specific needs and health issues, skills in money and asset management may need further development. However, aging-related problems and social prejudices can hinder the elderly from accessing money and managing budgets effectively. Recent studies highlight difficulties from health issues and negative actions by family members regarding asset and money management.

Financial exploitation is a significant form of elder abuse. It involves the use or illegal seizure of a person’s money, property, or financial resources to control, abuse, or harm (Conrad et al., 2011; S. Wood & Lichtenberg, 2016; Beach et al., 2018; National Network to End Domestic Violence, 2023; National Adult Protective Services Association, 2023). Islington Council defines financial violence as leaving the victim penniless, forcing them to account for every expense, taking away their salary or pension (Islington Council, 2021). Financial exploitation also includes misuse of financial accounts, changing wills, stealing bank accounts, and making non-beneficial financial transactions (Patel et al., 2021). Indicators of this abuse include unreasonable bank withdrawals, decreases in assets, losses of valuables, difficulties in meeting expenses, fraudulent power of attorney, and inadequate care relative to income (Eryiğit, 2022).

Although financial exploitation of the elderly has become an increasingly recognized social problem, many factors such as the lack of a clear and unambiguous definition, the fact that more than one type of abuse may occur at the same time in the elderly, and the fact that the abuser is a family member or a relative of the victim make it difficult to identify this abuse. Therefore, secondary data on the financial exploitation of the elderly are quite limited. A significant portion of the studies in the literature cover developed countries with significant elderly populations. Despite that the proportion of the elderly population is increasing, studies on financial exploitation of the elderly in developing countries such as Türkiye, which has a lower elderly population compared to developed countries, remain quite limited. However, it is inevitable for every individual with the right to lifelong development to sustain their economic freedom and effectiveness in meeting their developmental needs. Moreover, having to continue one’s life with reduced income during retirement will necessitate being more active and cautious in financial matters. Ensuring this requires both the presence of a conducive socio-cultural infrastructure and a social state understanding that aims to achieve this through social policies. At this point, the need for “successful aging”, which encompasses both individual and societal levels, also includes the concept of “active aging” at a higher stage, as characterized in Lifespan Development Theory. Therefore, in the process of achieving these goals, it is of great importance to assess both the status of financial skills and various forms of abuse.

The main goal of this study is to describe the financial decision-making profile of elderly individuals and their experiences of financial exploitation, considering the above factors conceptualized by the Theory of Lifespan Development. Additionally, the following research questions are addressed:

- What is the effectiveness of older persons in budget management processes, as an indicator of successful aging?

- What is the status of older individuals in terms of financial decision-making skills, as a key component of active aging?

- Have older people been subjected to abuse in financial matters, as a factor that hinders or complicates the lifespan development?

2. Literature Review

The concept of old age in Lifespan Development Theory (LDT) recognizes the challenges of aging while highlighting two key ideas: successful aging and active aging. Successful aging involves avoiding age-related illnesses, maintaining cognitive and physical functions, achieving high life satisfaction, and engaging actively in social life (D’Cosco et al., 2013; Badache et al., 2023). Active aging, on the other hand, ensures that people of all ages can participate fully in daily life across emotional, environmental, cognitive, physical, professional, social, financial, and spiritual dimensions (International Council on Active Aging; Uyanık & Başyiğit, 2018). Both concepts require policies to address individual and societal issues related to aging, including combating financial exploitation.

According to findings from the relevant literature, the fundamental indicators of healthy and successful aging are defined through the following components (Abud et al., 2022; Krivanek et al., 2021):

- Physical well-being, which includes physical capability, physical activity, daily exercises, and diet.

- Mental/cognitive well-being, which consists of four main determinants: self-awareness, outlook/attitude, life-long learning, and faith.

- Social well-being, which encompasses three main determinants: social support, financial security, and community engagement.

As evident from this structure, individual independence—defined as not being dependent on anyone and not subject to anyone’s directives—serves as the overarching indicator encompassing all other components. It represents a state that can only be achieved when all the other components are fulfilled. In this context, financial security, identified as one of the core components of successful aging, refers to the elderly individual possessing a level of financial strength that ensures a quality of life in which all basic needs can be met (Abud et al., 2022). Naturally, such a profile assumes that the individual is not subjected to any form of abuse. Therefore, in order to achieve these outcomes, the individual is expected to be actively engaged in social life—this expectation aligns with the concept of active aging.

According to the World Health Organization, active aging refers to preserving and enhancing the physical, social, and cognitive health of older people throughout their lives; ensuring care and protective measures within the scope of social security based on their needs; fostering their social relationships for greater societal participation; and minimizing the negative impacts of aging to enable a healthy and participatory later life (as cited in Akyıldız, 2024). WHO, which laid the theoretical foundation of this concept in the 1990s, proposes a process based on the pillars of health, participation, and security (as cited in Erbil & Hazer, 2023):

- The health dimension involves achieving successful aging through physical, cognitive, and social well-being.

- The participation dimension includes access to learning and educational opportunities, maintaining economic productivity through employment, and engagement in other socio-cultural activities.

- The security dimension refers to the protection of rights and needs through social, financial, and physical safety.

As emphasized in LDT, the key aspects of the aging stage can be summarized in three main points (B. B. Baltes & Dickson, 2001; Freund & Baltes, 1998):

- Individual development continues throughout life and can lead to certain vulnerabilities or sensitivities at different stages of development. For example, elderly individuals become more susceptible to financial exploitation due to cognitive decline (e.g., reduced ability to make financial decisions), social isolation (becoming more vulnerable to manipulation by scammers or even family members), and dependency (having to rely on others for financial matters). This aligns with Baltes’ Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) model. As elderly individuals lose certain skills, they develop new strategies (e.g., delegating financial tasks to a family member or caregiver). However, this situation can create opportunities for exploitation.

- Aging is not merely a biological process; it is shaped by cultural and socio-economic factors. Indeed, since elderly individuals were raised with different financial habits in their time, they may be less resistant to modern fraud methods such as digital banking scams.

- Individuals remain open to lifelong learning and change. In this context, through education and awareness programs, the deficiencies or inadequacies of elderly individuals in various areas can be addressed, thereby reducing risks arising from financial vulnerabilities. This is because individuals in old age can continue to develop.

In such a development process, due to both the natural challenges of the process and the adverse conditions specific to developing countries, some serious problems arise. Factors such as the rapid increase in the proportion of the population over the age of 60, issues related to food security, unfavorable urbanization conditions, and low average quality of life contribute to the inadequacy of the economic, financial, and political-administrative infrastructure of developing countries. This situation not only prevents the fulfillment of the fundamental developmental needs of the elderly population but also leads to serious deficiencies in security and care services (Bao et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021; Mondal, 2021). Consequently, it can be argued that rights violations, including various forms of abuse and exploitation, have become widespread. Financial exploitation is one of such issues.

Different methods and samples used in the literature on the definition and detection of financial exploitation make it difficult to determine the risk factors associated with financial exploitation. Studies, in general, examined the relationship between financial exploitation and risk factors such as gender (Biggs et al., 2009; Acierno et al., 2010; Lowenstein et al., 2009), income level (James et al., 2014), education level and numeracy (James et al., 2014; S. A. Wood et al., 2015; DeLiema, 2018), psychological and cognitive problems (James et al., 2014; Boyle et al., 2012; Lichtenberg et al., 2016), social support and social network (Beach et al., 2018; Choi & Mayer, 2000; James et al., 2014; DeLiema, 2018).

Research on gender and financial exploitation suggests varying findings: Some studies indicate no significant gender differences in the impact of financial exploitation on older adults (Biggs et al., 2009; Acierno et al., 2010). However, due to small sample sizes, these studies do not provide conclusive evidence and call for further research. Conversely, Lowenstein et al. (2009) found that financial exploitation ranked second among elderly individuals in Israel, with no gender difference observed, though women were more vulnerable to other types of abuse. O’Keeffe et al. (2007) reported that while the overall prevalence of financial exploitation among older adults in the UK (including 2100 elderly individuals aged 66 and over) was low (approximately one in 150), it increased with age for men but not for women. Soares et al. (2010) highlighted differences across European countries: in Germany, Greece, Italy, and Spain, elderly women were more likely to experience financial exploitation, whereas in Lithuania, Portugal, and Sweden, the opposite was observed.

The studies in the literature also show inconsistent findings regarding the role of economic status in elderly vulnerability to financial exploitation. The 1996 National Elder Abuse Incidence Study (NEAIS) found no association between income level and the likelihood of financial exploitation. Similarly, the National Elder Mistreatment Study (NEMS) indicated that income levels did not impact the risk of elder abuse (Acierno et al., 2010). However, James et al. (2014) and Peterson et al. (2014) argued that lower income was linked to higher susceptibility to financial exploitation. In a study of 4,156 individuals aged 60 and over in the USA, it was found that elderly people living below the poverty line face greater risks of financial exploitation, and victims of abuse tend to have less wealth compared to those with more financial resources. The study also highlighted that living with perpetrators in the same household increases the risk of financial exploitation among poorer individuals.

Furthermore, similar studies indicate that older adults with lower education levels, literacy deficits, and cognitive or psychological issues may face increased vulnerability to financial exploitation due to diminished financial decision-making abilities. James et al. (2014) examined 639 older adults without dementia, finding that susceptibility to financial exploitation was negatively linked to cognition, psychological health, and literacy. Boyle et al. (2012) studied 420 dementia-free individuals and noted that those with rapid cognitive decline exhibited poorer decision-making skills and were more prone to fraud. Lichtenberg et al. (2016) focused on 69 African American older adults, highlighting impaired decision-making as a vulnerability to financial exploitation. S. A. Wood et al. (2015) surveyed 201 community-dwelling adults aged 60 and older, revealing that low numeracy increased the risk of financial exploitation, alongside factors like physical and mental health and younger age. DeLiema (2018) similarly concluded that diminished financial capacity increased the risk of elder fraud and financial exploitation.

Other factors affecting the risk of financial exploitation are social support and social network. Beach et al. (2018) investigated the relationship between social support and social network and the risk of financial exploitation in a study of 903 older adults over the age of 60. The findings revealed that low social support and a large social network increased the risk. Acierno et al. (2010) demonstrated in their study conducted in the USA with approximately 5777 elderly individuals aged 60 and over that low social support increased the likelihood of experiencing abuse. These findings are also supported by James et al. (2014), who argued that a negative relationship existed between susceptibility to financial exploitation and social support. Choi and Mayer (2000) stated that financial exploitation and social support were correlated and as a result of their study, they found that older individuals with less social support were exposed to financial exploitation. O’Keeffe et al. (2007) found in their study conducted in the United Kingdom that financial exploitation was more prevalent among elderly individuals aged 66 and over living alone, particularly among divorced or separated women. They also found that women who reported feeling lonely were at a higher risk of experiencing financial exploitation. DeLiema (2018) revealed in his study that elderly individuals without children, trustworthy relatives, and social circles incurred a high risk of being victims of fraud. Similar results were also found by Feng and Lee (2018), who conducted semi-structured interviews with 12 elderly individuals in England. They concluded that loneliness and social isolation increased the risk of falling victim to fraud.

On the other hand, there are studies indicating that the risk of financial exploitation of elderly individuals stems from their family members rather than their social environment. According to NEAIS and the New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study (NYSEAPS), financial exploitation is mostly perpetrated by adult children, grandchildren, other relatives, and friends or neighbors (Stiegel, 2012, p. 75). Choi and Mayer (2000) and Acierno et al. (2010) asserted that financial exploitation was perpetrated by family members, whereas Laumann et al. (2008) revealed that older adults were most often financially exploited by siblings and adult children. It was also emphasized that married older adults incurred a lower risk of financial exploitation than unmarried older adults. This situation is further corroborated by the findings of O’Keeffe et al. (2007). The study’s results indicate that elderly individuals in the United Kingdom who receive home care services or are in communication with professionals are at a higher risk of experiencing financial exploitation, and perpetrators of abuse are often found to be other family members besides spouses. Lowenstein et al. (2009) stated that financial exploitation of the elderly in Israel was mostly perpetrated by adult children, who were often unemployed, undergoing separation or divorce processes, and tended to live with the victims. Peterson et al. (2014) emphasized that in the USA, perpetrators of financial exploitation were primarily family members, followed by friends, neighbors, or a paid home aide. It is also noted that the most common form of financial exploitation involves theft or misuse of money or property. Another form of abuse occurs when elderly individuals are coerced into surrendering or altering their rights, properties, or signing or changing a legal document. Mukherjee (2013) emphasized that adult children overestimated their parents’ ability to manage their finances; they preferred to manage their parents’ finances informally, and tended to think that their parents’ assets belonged to them.

Although there are studies in Türkiye aimed at developing data collection methods for elderly abuse and identifying risk factors for different types of abuse, financial exploitation has not received as much attention as other forms of abuse, and its conceptualization and measurement have not been extensively addressed. There is insufficient research on this topic in the national literature, with financial exploitation being examined categorically by Artan (2016) and Ünlü (2019). Artan (2016), in a study conducted with 100 elderly individuals staying in a nursing home in Istanbul, found that the elderly were mostly financially exploited by their children and that their relatives obtained financial benefits from elderly individuals due to financial hardship, purchase of goods, as well as starting a business and education, respectively. Additionally, it has been revealed that financial exploitation is more prevalent before entering nursing homes, while it continues to a lesser extent after entering such facilities. Ünlü (2019) found in their study that 63.1% of elderly individuals aged 65 and over living in Istanbul experienced financial exploitation, and the perpetrators were found to be predominantly the sons, daughters, spouses, and sons-in-law of the elderly. Moreover, the findings from the study indicated that 17.9% of the elderly had their belongings such as money, goods, or valuable jewelry taken without their permission, 13.6% were coerced by someone else to sell their own property, 55.7% were asked for financial support by others, and 18.6% took out loans against their pensions for any of their relatives. Likewise, the study concluded that there was no significant difference in the occurrence of financial exploitation based on the gender and marital status of the elderly.

Beyond these studies, it is also necessary to examine the current socio-economic and legal structure in Türkiye. Although a traditional oral culture once prevailed in Türkiye—one that advised respect for elders and affection for the young—the socio-cultural profile shaped by this tradition has largely deteriorated in the present day. This erosion can be attributed to various factors that have emerged since the 1980s, such as the problems caused by unplanned urbanization, the rise of the nuclear family model, the retreat of the welfare state and social policy practices, and the impoverishment resulting from the weakening of local governments in both financial and administrative terms. These developments have significantly damaged the social fabric. Moreover, issues such as discrimination and abuse have increasingly become part of the public discourse concerning the elderly (Çiçek, 2022; Doğmuş & Yıldırım, 2021; Pektaş et al., 2023).

Additionally, reforms in the social security system over the past 10–15 years have led to a substantial decline in retirees’ monthly incomes and overall quality of life. As a result, the financial independence (self-sufficiency) of the elderly population has been eroded, forcing many to cohabit with their children once again, as was common in previous generations. This situation has worsened when combined with the economic difficulties and health problems experienced by elderly individuals who remain in the labor market despite their advanced age, especially those excluded from the social security system (Aslan, 2024; Boyraz, 2024; Pelek & Polat, 2025).

On the legal front, it can be argued that there has been some progress toward a more mature understanding of the challenges facing the elderly. For instance, the National Plan of Action on Ageing and the Status of Older Persons in Türkiye (2007) included goals such as “eliminating all forms of neglect, abuse, and violence against older persons” and “providing support services to prevent elder abuse”. The plan recommended actions in four areas: legal regulation, professional training, preventive services, and public education. In the Healthy Ageing Action Plan and Implementation Program for 2015–2020, elder abuse and violence were again emphasized, with targets set for raising awareness among society, families, and institutions, preventing and identifying abuse, and developing health services specifically for elderly victims of violence. The strategy also included raising public sensitivity to elder abuse and violence, training healthcare professionals working in the field of geriatric care, and creating services to support elderly individuals who have been subjected to abuse (Akkaya & Çöl, 2022).

On the other hand, these legal frameworks appear insufficient for addressing current issues. In particular, when examining the distribution of social service expenditures, it is clear that the elderly receive one of the smallest shares. According to Eurostat data, while EU countries allocate 10.7% of public spending to retirees and elderly individuals, this figure is only 5.9% in Türkiye. Overall, social expenditures directed toward older adults in Türkiye are significantly lower than those in EU member states. Accordingly, the proportion of these expenditures in the national GDP is also relatively low, indicating a suboptimal level of social welfare among the elderly population (Boyraz, 2024).

Similarly, it can be argued that deteriorations in the education system and national education policies, along with insufficient family-oriented social policies, have led to a growing segment of young people who are neither in education nor employment. When combined with cultural disintegration driven by globalization, these conditions have negatively affected intergenerational interaction and contributed to a breakdown in familial relationships. Indeed, the rising number of elderly victims in recent years—as reported in judicial cases and academic research—concerning discrimination, financial exploitation, and domestic violence clearly supports this argument (Akkaya & Çöl, 2022; Baran & Taşcı, 2024).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

In this study, a qualitative research design is employed. All qualitative research studies are concerned with how meanings are constructed, and the primary purpose of this “basic qualitative research” type of study is to identify and interpret meanings based on the research questions. In this model, the findings collected by employing the interview technique based on purposeful sampling are thematized and described through inductive data analysis (Merriam, 2018). Therefore, the process that started with the application of the interview form developed in accordance with the purpose of the research to the selected participants is finalized by classifying and describing the findings through codes and themes. In terms of general structure, this research is within the scope of the survey model. Research in the general survey model identifies and describes a situation that existed in the past or present (Karasar, 2019).

3.2. Participants

In qualitative research studies, sample size does not have the same function as in quantitative research studies. The aim is to acquire more in-depth information from a small sample. Therefore, some researchers argue that the sample size in qualitative research should be determined according to the employed data collection method (Başkale, 2016). The study group of this research, which collected data through in-depth face-to-face interviews, consists of 23 participants.

In qualitative studies, it is crucial to determine the suitability of the study group size for data collection processes and the adequacy of participation. In fact, the ideal sample size for qualitative research varies depending on the research objectives and the depth of the data. Recently, it has been widely accepted that the optimal sample size depends on the quality of the data obtained from the sample. However, there are also differing opinions suggesting varying sample sizes based on the type of qualitative research. For example, in phenomenological studies, sample sizes range from 1 to 325 participants, while in grounded theory models, recommendations generally suggest a minimum of 20 to 30 participants (Baltacı, 2018). If the researchers realize that in the data collection process, collecting more data does not contribute, the application is terminated and it is accepted that the most appropriate study group size has been reached (Merriam, 2018). On the other hand, in line with the nature of qualitative research, it is also possible for researchers to design the sample size based on their experience and intuition. In this study, it is observed that the average size of the study group, which is common in the literature, is around 13–18 people for basic qualitative research (Baltacı, 2018; Hennink & Kaiser, 2022), but it is thought that this might not be sufficient for the structure of the study. The study is initiated with a participation goal of 25 participants; when it is seen that the similarities increase too far after inclusion of the 20th participant, data collection is finalized at the 23rd participant.

Through snowball sampling, which is one of the types of purposive sampling, those who are willing to contribute and can express themselves among the candidates who fulfill the criteria are identified (Merriam, 2018). Purposive-intentional sampling is based on people who are believed to respond to the research questions and consists of participants determined according to certain criteria (Altunışık et al., 2010; Merriam, 2018). In this context, the study group is composed of individuals over the age of 65 who were identified as extroverted and had complaints about their financial situation The identification of ‘extraversion’ and the willingness to participate in such research were based on the researchers’ subjective observations. During this selection process, each researcher received support from their own relatives and graduate students. In this context, the study group consists of elderly individuals residing in two different cities in Turkey (Mersin and Adana). In the first stage, new participants were selected among the people in the social circle of the researchers, and then new participants were selected through volunteering friends of the first participants. When selecting suitable relatives, informal communication channels within the family were utilized. Similarly, preliminary information about individuals within the social circles of university students was conveyed to the researchers by the students themselves.

Table 1 presents the profile of the study group.

Table 1.

The information on participants’ demographical profile.

According to the data in Table 1, 12 of the participants were male and 11 were female. The average age of the participants was 72.6 years. Seven of the participants were widowed individuals who lost their spouses. The other 16 participants were married. They were also asked with whom they lived, and 5 of the 7 widowed participants stated that they lived alone, 1 participant lived with her son, and 1 participant lived with her grandson and grandson’s spouse. Among the married participants, 12 stated that they lived with their spouses, while 4 participants stated that they lived with their spouses and children. When we look at the monthly household income level of the participants, the lowest income belonged to the participant who stated that he/she received an elderly pension of USD 54. The highest high income was USD 1075. The average monthly income of the participants was USD 338, which is below the hunger threshold of USD 399.19 announced by the Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions (TİSK) during the period when the data were collected. Therefore, it can be observed that the profile of participants in this study is characterized by a monthly income lower than the monthly minimum wage of USD 348, which was in effect in Türkiye in 2022.

The majority of the respondents (21) were retired, 7 of whom were women who received part of their husband’s pension due to his death. Two of the retired respondents were also working. Finally, 5 of the participants stated that they had no health problems, one participant said that she was being treated for bladder cancer, while the others had chronic diseases such as diabetes, blood pressure, heart disease, cholesterol, and rheumatic diseases.

3.3. Development of the Data Collection Tool and Data Collection

The data of this study were collected through the interview/interview method. The interview technique is the collection of research data through oral communication (Karasar, 2019). “Face-to-face interview” was preferred as a data collection method among the interview types; a semi-structured interview form consisting of 14 questions was applied as a data collection tool. Face-to-face interviews were conducted through forms printed on paper. This format has more advantages than telephone or computerized applications (Tymms, 2017) and is more suitable for the purpose of this study. The data collection tool included 9 open-ended questions in addition to demographic questions. The wording of these questions was derived in a way that reflects the main research questions and allows for probing to identify attitudes and problems in the literature on financial exploitation in the elderly, as Table 2 illustrates.

Table 2.

Source of interview form questions.

As shown in Table 2, while designing the questionnaire—the primary data collection tool—three questions were developed for each research question in line with their respective scope. The topics and content of these questions were determined based on definitions of financial exploitation found in the relevant literature. Indeed, studies aiming to define and measure possible indications of financial exploitation typically focus on three main components (Collins, 2017; Lichtenberg et al., 2016; Soydaş, 2023; Wendt et al., 2015):

- The individual’s capacity to make financial decisions and manage income.

- The forced or unauthorized use or appropriation of income or resources by others.

- The transfer or appropriation of income or resources against the individual’s will (through methods resembling coercion), yet still within the bounds of legal frameworks.

Accordingly, the questions in the questionnaire were developed in line with the framework reflected in the relevant literature. Open-ended questions are often preferred in qualitative research based on the interview technique, because they enable in-depth information gathering (Tymms, 2017). In this study, in-depth interviews were conducted using semi-structured interview forms. The aim of this method is not to reach definitive answers, but to enable the participant to describe his/her perceived world in his/her own words (Merriam, 2018). For the pilot application, the comprehensibility of the questions was tested by first applying them to two people. After some changes were made to the sentence structures in questions 4 and 6, the interviews started.

Within the scope of internal validity or credibility criterion, for participant confirmation, the data collected through face-to-face interview technique were written and organized on papers and then read to the participants at the end of the interview to confirm their responses. Upon the request of a total of three participants, some corrections were made to the recorded responses. Participant 8 re-listened to questions 2 and 7 and had the answers reprinted; Participant 13 had the sentence fragments in the answer to question 9 corrected. Participant 22 further expanded and elaborated her answers to questions 5 and 7. The other participants approved what was written without any corrections or changes. All interviews were conducted in the participants’ own homes and lasted 40–45 min on average. The whole implementation was completed in 9 days. After every 3–4 completed interviews, the data status and the course of the research were evaluated by looking at the course and structure of the responses obtained.

3.4. Data Analysis

In the analysis of qualitative studies, descriptive analysis or content analysis is generally applied. Content analysis refers to creating themes in accordance with the relationships between the codes derived from the findings with an inductive approach. Three types of coding can be applied in this model: Coding based on concepts in the literature, coding based on research data, and general framed coding reflecting the combination of these (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2000). In this study, “general framed coding” was applied on the axis of content analysis. For this purpose, while creating the themes, both the terms in the literature were utilized and the codes based on the findings were evaluated. Thus, the functionality of the analysis was increased by ensuring that both the basic concepts in the literature and the results based on direct data were used together. A total of 22 main themes were defined and the details of the analysis process are described in the Validity and Reliability section.

3.5. Validity and Reliability

In qualitative research, the criterion of credibility is recommended instead of the concepts of validity and reliability in quantitative research. Within the scope of credibility, “purposive sampling”, “participant confirmation”, and “researcher triangulation/triangulation” were used in this study. Participant confirmation refers to the verification of the data and report by contacting the participants at the end of each interview, and researcher triangulation refers to the involvement of more than one researcher in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data (Başkale, 2016; Merriam, 2018). In this context, a suitable study group was determined on the basis of purposive sampling in accordance with the basic qualitative research model, and the data collected were verified by the participants. Two of the researchers who conducted the study participated in the analysis process by conducting the data collection application, while the other two researchers constructed the theoretical structure.

In a good qualitative research study, a sincere explanation of how the results obtained were reached is an indicator of reliability or consistency. In this method, called the audit technique, it is necessary to describe the analysis process and how the findings were reached, as if recording in a ship’s logbook (Merriam, 2018). The analysis process of this study can be summarized as follows:

- Two researchers from the authors of this study performed the process of theme and code generation independently of each other. Twenty-three forms were shared and codes were defined; two rounds of analysis were completed by exchanging the finished forms. While the first researcher identified a total of 17 main codes, the second researcher created 20 codes. It was observed that the difference was due to the classification of monetary support and non-consensual reduction in material values. Consensus was reached on the distinction between children and social environment in monetary support and on the definition of household goods, immovable and movable property codes in the loss of material values. Afterwards, it was understood that the other codes were close to each other at the 90% level and a total of 22 themes were agreed upon.

- While creating the themes, a longer effort was required and the researchers worked in parallel on this process. For example, since it took a long time to define the codes that make up the themes of “self-efficacy in financial decisions”, “wrong investment decisions”, and “domestic fraud-fraud”, the derived codes were shared instantly. After the codes constituting the other themes were completed, they were combined with each other and those with similarities were eliminated. At this stage, a complete harmony was achieved in all 10 main themes. The level of agreement in the codes of the themes “losses in securities” and “signature forgery in financial transactions” remained at 70%, and the codes were corrected after discussions and re-reading of 14 forms.

- In the final stage, the interview forms were returned and the notes taken at the beginning were compared with the codes created. In this context, from the responses in forms 3, 11, 19, 22, and 23, it was seen that the theme of “financial aid to children and the social environment” should be categorized on the basis of consent/approval and the code “influence of family members in financial decisions” should be added.

4. Findings

The findings of this study are presented below according to the main research questions. The first interview question was related to the financial status of the participants.

- A.

- In this context, in response to the research question “How is the effectiveness of older individuals in budget management processes?”, 3 questions were asked in the interview forms:

- 1.

- The 14 codes and 5 themes generated according to the answers to the question “How satisfied are you with your financial situation in general? Briefly explain your income and expenditure situation” are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Financial status.

Table 3. Financial status.

The codes and themes in Table 3 show that the majority of the participants were dissatisfied with their income (78% of the participants), had difficulty paying bills such as electricity, natural gas, water, etc., and had to cut down on their kitchen expenses. Participants stated that their pensions are very low and the price of everything has increased a lot. Two of the participants stated that they used to be well off, but their economic situation deteriorated due to the pandemic and the economic crisis. Three participants stated that their income covered their expenses and that they were satisfied with their income.

Some examples chosen from the responses:

P2: “… Income does not cover expenses. Natural gas, electricity and water cost 1400 TL. I took out a loan. 189 TL is deducted from it. It is very difficult to make a living”.

P5: “I constantly borrow money and pay my debt with the next month’s salary. My married sons help me sometimes. We cannot buy and eat what we want”.

P13: “I live on my own and my deceased husband’s pension. I own my own house, so I am satisfied with my financial situation. My own pension is sufficient for my expenses. I sometimes use my husband’s pension to support my children”.

As can be seen from the above responses, participants complained that their income could not meet their expenses. P13, on the other hand, stated that his income was sufficient. This profile indicates that an elderly group experiencing economic difficulties needs to improve their budget management skills to cope with the challenges of life. Indeed, as the economic conditions in many developing countries, including Türkiye, become increasingly challenging, it is leading to a weakening of the financial capabilities of societal segments across all age groups. This situation may exacerbate problems related to household income management while, on the other hand, it could be expected to positively affect intra-family solidarity.

- 2.

- “Who do you think manages your money? Do you determine your monthly expenditures, savings and investment instruments by yourself? Explain.” In this context, 10 codes and 4 themes were formed and are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Management of money (budget management).

Table 4. Management of money (budget management).

Sixteen participants (69.5% of the participants) answered that I manage my money. Three of the participants said that their children manage their money, two of the participants said that their spouse manages their money, one participant said that he/she makes decisions together with his/her spouse, and one participant said that his/her granddaughter manages his/her money together with his/her daughter. Regarding the determination of investments and savings, 30.43% (7 people) of the participants said that they made their own decisions, 21.73% (5 people) received help from their children, 8.69% (2 people) received help from their spouses, 8.69% (2 people) received help from bank employees, and 4.34% (1 person) said that they made savings and investment decisions together with their spouses. Finally, 26.06% of the participants stated that they did not have enough income to save and invest and that they had difficulty in meeting their basic needs.

Examples of responses:

P8: “I manage it with my husband. We manage the joint family budget together. We make savings decisions together”.

P16: “I usually manage it myself. I also get support from my son for payments and savings. Since my son follows the trends for investment, I often consult him. For example, he opens a gold account for me and I try to invest a small amount every month”.

P17: “I manage my money myself. The pension I receive is barely enough to cover the expenses of the house. I cannot save money or buy anything else”.

P19: “I manage my money. I also get help from bank employees. They give me information on how to invest my money”.

An analysis of the participants’ responses reveals that the participants themselves make their own savings-investment decisions in money management, but they also receive help from family members and bank employees. Therefore, while there may be common aspects of income inadequacy, it can be said that elderly individuals have different attitudes and individual competencies related to budget management. However, the support provided by spouses and children within the family may facilitate overcoming challenges related to financial allocation.

- 3.

- “To what extent do you seek help with financial decisions? Do you trust others in such decisions? Explain.” was asked. The responses of the participants are presented in Table 5 with 8 codes and 5 themes.

Table 5. Assistance and trust in financial decisions.

Table 5. Assistance and trust in financial decisions.

The most repeated response to this question (10 people) was “I trust my children and get help from them”. Four of the participants stated that they receive help from and trust their spouses. Two participants stated that they trust and receive help from bank employees, 1 participant stated that they trust and receive help from their spouse and children, and 1 participant stated that they trust and receive help from their children and bank employees. One participant stated that they follow economic programs and make decisions accordingly. Four participants stated that they do not ask for help from anyone and do not trust anyone. The answers of the participants show that most of the elderly individuals in the study group trust their family members and receive help from them in financial decisions.

Examples of responses:

P4: “I do not trust others with money. I would like to help anyone who asks for help”.

P11: “I get help when necessary. I ask my children or bank employees. I trust the decisions of others”.

P15: “I do not ask for help from anyone other than my daughter and son in financial decisions, especially if there is a joint purchase, we decide together. For example, we bought the house we live in together”.

P16: “Today, there are many different financial investment instruments such as cryptocurrencies. I am a person with a traditional mindset. If I am going to make an investment decision, the person I trust the most is my son. I do not trust anyone other than my son in this regard”.

P17: “I do not trust anyone. I watch economic programs and news on TV. I cannot get help from anyone. I make my own decisions”.

P21: “I do not trust anyone. If I had a lot of money, my children would buy it”.

Both the direct responses above and the codes in Table 3 indicate attitudes representing all kinds of tendencies among elderly individuals in the study group, regarding seeking help from others in financial matters. For instance, the point where those who trust no one but themselves differ from those who only trust their children could be related to their level of personal confidence or family environment. In a family where relationships based on trust with spouse and children prevail, it is expected that family members trust each other unconditionally. Similarly, elderly individuals with a high perception of personal confidence will be able to manage their money without consulting or asking for help from anyone.

- B.

- Indirect detection of financial exploitation is possible. For this purpose, it is important to identify individuals’ past financial losses and regrettable financial decisions, whether they experienced them or not. Such situations may provide key clues in determining potential cases of financial exploitation (Lichtenberg et al., 2016). In this context in response to one of the research questions, “How are the elderly individuals in terms of financial decision-making skills?”, the findings of the 3 questions in the interview form are presented below.

- 4.

- “Do you regret or worry about your recent financial decisions? Give an example”. Ten codes and 4 themes were generated from the responses and Table 6 presents them.

Table 6. Accuracy in financial decisions—satisfaction status.

Table 6. Accuracy in financial decisions—satisfaction status.

Six respondents (26%) regret having exchanged savings instruments such as gold and foreign currency when their value was low. The other 6 participants regretted not buying movable and immovable assets such as gold, houses, land, and cars. Five of the participants (21.7%) stated that they trust their financial decisions. Three participants stated that their income was insufficient to make financial decisions. One participant stated that her daughter manages her money and that she has no knowledge about this issue. In addition, one participant said that she gave her gold to her daughter, while another participant said that she regretted giving all her money to her daughter.

Examples of responses:

P1: “I invested in gold in bulk. It did not change for 3–4 years. Then I had to sell it, and it went up after I sold it. The same is true for my foreign currency investments”.

P13: “No, I have never made a decision that I regret, I do not worry about financial issues for myself, I only worry about the future of my children from time to time”.

P17: “I wish I had bought a house earlier. I regret not buying a house yet. I cannot buy a house after this time. I am just trying to make ends meet”.

P23: “My husband died last year. I gave all my money to my daughter. I regret it. I wish I had bought gold and kept it all, I regret it”.

In parallel with the previous responses, there is a group that responded positively to this question and was satisfied with the accuracy of their financial decisions. In contrast, a large portion of the participants either regretted their financial decisions due to various reasons or did not feel competent or empowered to deal with such decisions. This situation may reflect not only inadequacies in financial skills but also hints of financial exploitation. Indeed, subsequent questions and responses exhibit findings in this regard.

In Türkiye, the primary areas where individual savings can be directed include purchasing gold lira, foreign currency, or real estate. Asking for numerical values regarding such decisions may raise privacy concerns or may not be feasible, as elderly individuals might not accurately recall such figures. Therefore, the responses to this question were evaluated based on the perception of accuracy or appropriateness rather than a specific quantitative measure.

- 5.

- “In the last few years, have you given money to anyone because they asked you for money? If so, who and why?” was asked as the 5th question. When the findings with 16 codes and 3 themes were analyzed, it was seen that mostly family and close relatives were asked for money, and some aid organizations also requested support. The reason why money was usually requested was the financial difficulties experienced by the family and close relatives.

More than half of the participants (52.17%) stated that their children asked them for money. As seen in Table 7, the participants had to give money to meet their children’s needs or to pay their debts. Five of the participants stated that they gave money to their close relatives such as their siblings, nephews, and grandchildren. One of the participants stated that he gave money to his neighbor, 1 to his caregiver, and 1 to an aid organization. Two participants stated that no one asked for money. Participant 10 stated that her husband was in charge of her financial management and that she could not give money even if she was asked for money.

Table 7.

Status of requesting money from participants.

Selected examples of the responses:

P2: “My son wants it all the time. He usually gives his money to drink and gamble. He runs out of money, he asks me”.

P13: “My children sometimes ask for money, but not big amounts, I give them pocket money from time to time to buy things for themselves when I go to their homes”.

P17: “A few of my relatives who were in a difficult situation asked for money. My husband’s brother asked me for money to settle his debts. But I could not help because I did not have the means”.

P20: “My children hired a caregiver who comes 3 days a week to take care of me. She wants me from time to time, for her needs”.

P22: “I gave 5 bracelets to my daughter. She said she would give them to me after I paid off my debt, but she did not, now she is angry with me”.

The codes and direct response examples in Table 5 have indicated that half of the participants in the study group provide money to their children to support them, as shown. As mentioned above, this situation may be an indicator of social solidarity within family relationships, but it could also show signs of financial exploitation. It is necessary to examine under what context and conditions such income transfers take place.

- 6.

- “Have you ever provided financial assistance to anyone without your consent? If so, to whom and how?” When Table 8 is examined, it is seen that there are findings parallel to question 5; the participants generally support their family and close circle, albeit reluctantly.

Table 8. Involuntary financial assistance (forced financial assistance).

Table 8. Involuntary financial assistance (forced financial assistance).

Eight of the participants stated that they helped their children to meet their debts and needs even though they did not volunteer, and 6 participants stated that they provided financial support to their close relatives such as siblings and nephews against their will. In other words, 60.81% of the participants were forced to provide financial support against their will. Nine participants stated that they did not provide financial support to anyone against their will.

Examples of responses:

P2: “I give it to my eldest son against my will. I usually pay his loan and phone debts”.

P6: “I gave it to my brother, his wife had died and his children needed it, even though I did not want to.”

P7: “No, there was no such thing, I helped my daughter completely voluntarily”.

P12: “I helped my nephew to pay off his gambling debt even though I did not volunteer”.

P21: “I did it for my son, I gave him the house I inherited from my husband, and my daughter was very angry with me”.

The vast majority of participants have provided monetary assistance unwillingly, either to their own children or close relatives. This situation may reflect not the spirit of social solidarity within the family and among relatives, but rather a profile of exploitation where elderly individuals are coerced into doing things against their own consent.

- C.

- “Have elderly individuals been subjected to abuse in financial matters?” The findings of the three questions included in the interview form within the scope of this research question are presented below.

- 7.

- “Have there been unexplained losses of your money or possessions? Did someone take advantage of you to get your resources such as house, car or money?”. In this context, 12 codes and 5 themes were created.

Upon analyzing Table 9, we see that money and gold were lost from the participants’ homes. One participant stated that cleaning and food supplies were lost from their homes. When the table is analyzed in the context of the second question, it is seen that children especially take away their homes without the consent of their parents. Nine participants stated that their wealth and money were taken away by their children and close relatives, even though they did not want it. Two participants stated that their children wanted their houses but they did not give them to them.

Table 9.

Losses in money and wealth.

Examples of responses:

P2: “I had Euros and TL that I had saved at home and they disappeared. When my older son comes home, he rummages everywhere. He probably took them”.

P4: “I had a small empty shop and my brother constantly abused me emotionally. I gave him a very low rent to run the shop but he does not even pay the rent”.

P6: “My children always want my land and houses. My eldest son bought one of the houses by deceiving me”.

P14: “My children want my house sometimes. I have one house, they can buy it after I die”.

P18: “Yes, some of my belongings were taken by my children. For example, they took my TV, refrigerator, carpet”.

P21: “My son bought my house. He rented it out. He evicted me and put me in a cheaper house. I rented out my own house”.

According to the findings above, one-third of the participants have experienced adverse experiences, indicated in the first three questions and referred to as inevitable outcomes. Indeed, as observed in studies conducted in different countries, the majority of actions that could fall under the scope of financial exploitation originate from the closest family members. The children of elderly individuals in this study group may have engaged in such actions under the pretext of support or assistance in financial decisions, or even directly through coercion.

- 8.

- “Have you granted power of attorney or personal authority to someone, willingly or unwillingly, to conduct financial transactions on your behalf? If yes, to whom and for what purposes?” In response to this question, 56.52% of the participants (13 people) stated that they did not give power of attorney to anyone for any financial transaction, and a total of 10 codes and 5 themes derived from this question are shown in Table 10.

Table 10. Asset abuse through power of attorney.

Table 10. Asset abuse through power of attorney.

Seven respondents stated that they usually give power of attorney to family members for monetary and other transactions or to a lawyer for business follow-up. Three participants gave their cards and passwords to children for internet and ATM transactions. While asking this question to participants, the term (power of attorney) specifically referred to the officially recognized power of attorney type, issued through formal channels and valid across Türkiye. The responses received also contained information related to this type of power of attorney. The sample responses below are presented within this framework. Examples of responses:

P2: “I have some land plots inherited from my parents; I gave power of attorney to a lawyer for their follow-up”.

P6: “I gave it to my eldest son and he transferred my rented house to his own name”.

P11: “I did not give a legal power of attorney. I gave my passwords to my children to make mobile banking transactions. All transactions are made by them”.

P19: “I had given it to my eldest son. He transferred many plots of land to his own name and sold them. I fell out with my other children. Then I canceled it”.

P23: “I gave it to my daughter even though I did not want to, I am illiterate. She also draws my salary”.

The factors underlying the responses to this question also encompass multidimensional components. It could be said that the socio-economic status of families and individuals, socio-cultural conditions, adequacy of social policies targeting the elderly, and characteristics of the legal system constitute the underlying systematic structure of these responses. For instance, an elderly adult with insufficient basic literacy skills is particularly vulnerable to financial exploitation. Moreover, the rapidly changing technological environments of today’s world can quickly render the financial competencies of older generations obsolete. Naturally, in such circumstances, elderly individuals may have no choice but to seek support from others/experts. Undoubtedly, the granting of a power of attorney does not necessarily indicate that exploitation is occurring, but under certain conditions, it could be seen as an indication of such a possibility.

Moreover, the inherent ambiguity of ‘free will’ in such power of attorney transactions leads to an implicit suspicion, regardless of whether the transactions are of an official nature or not. However, this aspect of the matter falls outside the scope of this study. In other words, aside from the legal risks and consequences of appointing an attorney, only the existence and content of the power of attorney itself can be considered in the assessment of potential financial exploitation.

- 9.

- “Has anyone ever persuaded you to sign any document even if it was not in your best interest? If yes, to whom and on what issues?” was directed as the final question. In response to this question, 52.17 of the participants (12 participants) stated that they did not sign any document. Seven codes and 3 themes were derived.

According to Table 11, 11 respondents who were made to sign any document were usually persuaded or coerced to sign a document by family members, especially by their children. Three participants were subjected to fraud during the shopping process. The relevant situation can be seen in the sample responses below.

Table 11.

Misuse of signature.

Some examples of the responses:

P2: “He said he was a carpet seller and made me sign a promissory note. When I went later, the shop was closed. I thought I bought a carpet, but I got into debt much higher than the price of the carpet. They defrauded me. My children were very angry with me”.

P3: “As I said before, my son convinced me to sign the document that I gave him the house on condition that I pay my daughter’s debts. He said give me the house, we will live together anyway, but when he gets bored, he kicks me out of the house”.

P5: “My wife had an accident in the past. A relative of mine said he would help her for her treatment. He handed me a paper and asked me to sign it. I trusted him at the time and signed it. It turned out that he made me sign a promissory note and took away my house. He deceived me”.

P9: “I sign when banks or official places ask for a signature. Once I went for my wife’s phone line. My wife’s line was not working. They asked for my signature and I signed. It turned out that they had sold me a phone line. I paid for 1 year for nothing.”

Findings suggest that a small subset of participants were financially exploited through coercive measures or persuasive efforts relying on the signature as a means of personal consent. In such cases, the perpetrators were again often the children or close family members of the participants. Another small group recounted experiences indicating classic scams. Examples of such scams originating from individuals outside the family circle may relate to both the education level of elderly individuals and their susceptibility to isolation due to disconnection from social networks.

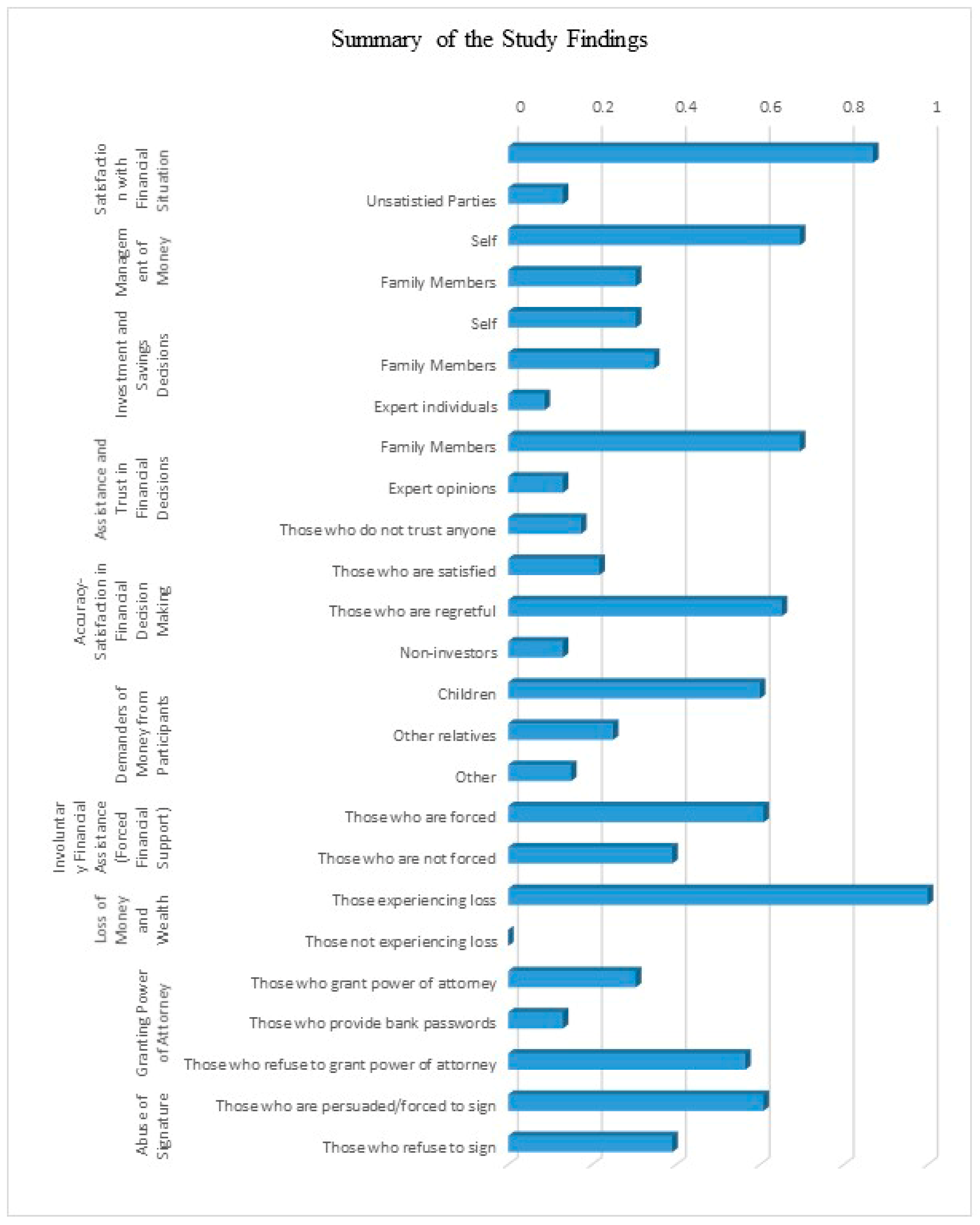

As seen, the content and progression of the findings indicate the presence of a certain level of financial exploitation. The overall descriptive summary of all findings can be summarized as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The graphical illustration of the main findings.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

People inevitably age throughout their journey of life. This aging process progresses continuously and irreversibly, and this process causes some changes in people’s bodies and affects their cognitive skills, attitudes, behaviors, and relationships with their environment. With the increasing human lifespan, the time individuals spend in old age has also increased, and older individuals have started to make plans to live a more comfortable life in this part of their lives. It is possible to say that a significant part of these plans is aimed at acting in a healthier, safer, and more financially comfortable manner. However, it has become a common situation for elderly individuals to be exposed to some kind of abuse at the point of managing their budgets and making financial decisions. This situation is explained as “financial exploitation”, which is a sub-type of elder abuse. Although financial exploitation of the elderly has become an increasingly widespread social problem, many factors such as the lack of a clear and precise definition, or the fact that the abuser is a family member or a relative of the victim make it difficult to identify such abuse.

In Türkiye, the number of households consisting of individuals aged 65 and over living alone exceeds 1.5 million (TÜİK, 2021). This indicates a significant number of elderly individuals living alone and thus requiring support in terms of healthcare, caregiving, and social security services. These figures highlight the need for Türkiye to implement various new social policies to prepare for the aging population process. Therefore, it is evident that institutions in Türkiye need to conduct a situational analysis as a priority in adopting and achieving the goals of “successful aging” and “active aging” in compliance with the LDT. Through such research and similar studies, a detailed profile of the elderly population can be obtained, and fundamental policy models for successful and active aging can be discussed. This study demonstrates that forms of abuse such as financial exploitation need to be clearly defined within emerging theoretical frameworks. Furthermore, it highlights the necessity of supporting these definitions through periodic international research to inform future theoretical developments.

Upon evaluating the findings of this study, it was determined that participants experienced financial exploitation, albeit dependent on various factors. In this context, these results comply with the studies of NEAIS (1998), Biggs et al. (2009), Lowenstein et al. (2009), Acierno et al. (2010), Boyle et al. (2012), James et al. (2014), S. A. Wood et al. (2015), Lichtenberg et al. (2016), DeLiema (2018), Beach et al. (2018), and Choi and Mayer (2000), indicating elder abuse is a reality in Türkiye.

According to the research results, the first research question sought to be answered is found to be related to the effectiveness of elderly individuals in budget management processes. Upon analyzing the responses to the questions in this context, first of all, it is determined that the income level of most of the participants is quite low and that the participants have difficulty in fulfilling even their basic needs, especially due to the high inflation in Türkiye in recent years. In addition, it was observed that the participants’ budgets were mostly managed by their children. This is in line with the findings of Mukherjee (2013), who found that adult children are quite willing to manage their parents’ financial means and perceive their parents’ assets as their own. Moreover, the fact that the income level of the participants was below the poverty line in Türkiye is in line with the findings of many studies around the world. Similarly, Acierno et al. (2010) stated that the likelihood of financial exploitation is not related to income level and pointed out that some institutional studies, like the National Elder Abuse Incidence Study, on the elderly in the US also have findings in this direction.

Within the scope of the other research question, we tried to determine the situation of elderly individuals in terms of their financial decision-making skills. It was found that the participants received help especially from their children in financial decision-making, while the participants with higher income benefited from the opinions of bank employees when necessary. The most important finding of this research question is that most of the participants regret their financial decisions. Elderly people who regret their financial decisions in the past may lose confidence in their budget management and may need the help of others to make financial decisions. This situation makes the elderly vulnerable to financial exploitation and can be both the cause and the consequence of possible exploitation. Furthermore, 13.04% of the respondents claimed that they did not have enough income to be able to save and invest.

Lastly, we attempted to determine the indications of the exposure of elderly individuals to abuse in financial matters. In this context, the findings, especially regarding abuse through power of attorney, showed that more than half of the participants did not experience any abuse of power of attorney. The findings related to the misuse of signature, on the other hand, showed that more than half of the participants did not experience such abuse. It can be said that the other respondents might be exposed to financial exploitation by both family members and marketers. When all of the questions related to exposure to financial exploitation were evaluated, it was seen that although the income levels of the participants were generally very low, there were partly some indications of mistreatment, so they might be exposed to financial exploitation by family and close relatives, which is in line with most of the research findings around the world (Choi and Mayer (2000); Acierno et al. (2010); Laumann et al. (2008); O’Keeffe et al. (2007); Lowenstein et al. (2009); Peterson et al. (2014)).

Many studies investigating financial exploitation of the elderly have examined factors such as the elder’s financial decision-making ability, gender, and economic status to determine their influence on financial exploitation. Discrepancies exist among the findings of these studies regarding the evaluation of these factors. While some studies have indicated gender as a significant factor in financial exploitation (O’Keeffe et al., 2007; Soares et al., 2010), others, consistent with the findings of our study, have concluded that gender is not a significant factor in financial exploitation (Biggs et al., 2009; Lowenstein et al., 2009; Acierno et al., 2010).

The number of studies examining the situation of elderly individuals regarding financial exploitation in Türkiye is quite limited. As indicated in the literature review section, the precursors of these studies are the works of Artan (2016) and Ünlü (2019). The significant findings of these studies, such as the levels of financial exploitation experienced by the elderly and the perpetrators of exploitation primarily being family members and close acquaintances, are supported by our study. Additionally, Köroğlu ve Ersöz (2019) conducted a study aimed at determining the financial literacy levels of elderly individuals residing in nursing homes in Türkiye. Despite finding that the majority of elderly individuals lack sufficient knowledge in finance and economics, particularly in banking and inflation, they concluded that they possess high skills in investment, expenditure, and money management. Although our study is qualitative in nature, it complies with the quantitative study of Köroğlu ve Ersöz (2019), especially regarding the management of finances.

In contemporary Türkiye, particularly regarding the care of the elderly (especially those in the advanced elderly group), children are primarily seen as responsible. However, changes in family structure, transitioning from extended families to nuclear families, the increase in the duration of women’s education, and their participation in the workforce will lead to an increased need for practices and institutional care services that enable the elderly to maintain their daily lives (Tezcan & Seçkiner, 2012). This situation highlights the necessity for social state bodies and civil institutions to intervene and produce supportive and preventive social policies to address these needs and prevent abuse.

Compared with the existing literature, the findings of this study reflect characteristics commonly observed in developing countries, particularly regarding the financial vulnerability of elderly individuals, their dependence on family members for financial decision-making, and limited economic resources. In many developing contexts, insufficient income, inadequate social security mechanisms, and the reliance on family-based care-giving systems make financial exploitation more difficult to detect and report (Yon et al., 2017; DeLiema, 2018). By contrast, in developed countries, well-established social welfare systems and more effective legal and institutional mechanisms enable better identification and intervention in cases of elder financial abuse (Pillemer et al., 2016). Our study, especially its findings on exploitation by close family members, underscores the structural vulnerabilities faced by older adults in developing countries. In addition, one common finding emerges across both country groups: older adults’ frequent regrets about financial decisions and their subsequent loss of confidence in financial management (Lichtenberg et al., 2016; Köroğlu ve Ersöz, 2019). This comparison highlights the universal aspects of elder financial exploitation despite cultural and institutional differences. Thus, this study contributes both empirically and comparatively to the growing literature on elder financial exploitation, particularly from the perspective of a developing country.