Abstract

This study examines whether the gaps in four financial well-being (FWB) indicators—emergency fund availability, spending less than income, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt—between groups with varying levels of financial literacy changed during the economic disruptions of 2020–2022 compared to the more stable period of 2017–2019. Using data from the 2017–2022 waves of the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking conducted by the Federal Reserve Board, this study applies difference-in-differences and event study methods to explore these trends. Descriptive findings, consistent with prior research, show that respondents with higher financial literacy reported greater FWB across all years. Regression estimates based on respondents who provided definitive answers (correct or incorrect) to the Big Three financial literacy questions suggest that the pre-existing gaps in emergency fund availability and perceived financial comfort between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy widened in 2020–2022, whereas the gap in spending less than income remained unchanged. There is some evidence of a widening gap in the likelihood of having no credit card debt, but the estimates are less conclusive. In general, these results indicate that higher financial literacy might have served as a protective factor for some aspects of FWB amid the challenging economic conditions of 2020–2022. However, results based on respondents who provided either correct or “don’t know” answers to the same questions differ in direction from the results of the earlier analysis. The findings of this study have implications for measuring financial literacy and investigating its role in shaping FWB.

1. Introduction

Millions of people in the U.S. lack basic financial literacy, which limits their ability to manage personal finances effectively (Lusardi & Streeter, 2023). Previous studies find that financially literate individuals tend to plan more effectively, save more, achieve higher returns on their investments, and manage their finances more efficiently during retirement (Mitchell & Lusardi, 2015). As individuals with lower financial literacy are less likely to make prudent financial decisions, their financial well-being (FWB) may deteriorate to a greater extent during periods of economic instability. For example, individuals with lower financial literacy are less likely to have emergency savings (Hilgert et al., 2003), which potentially makes them more vulnerable during an economic crisis. In addition, a limited understanding of the consequences of rising inflation and interest rates may lead to suboptimal financial choices.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a wave of financial disruptions to individuals and households across the U.S. The economy plunged into a recession in 2020, pushing the unemployment rate to an unprecedented 14.8%, the highest level ever recorded (Congressional Research Service, 2021). To mitigate the crisis, the federal government introduced a series of relief measures, including three rounds of stimulus payments, safety net expansions, and eviction moratoriums. As recovery began, however, a new challenge emerged: inflation started rising in the second quarter of 2021 and reached a 40-year high in 2022 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). Supply chain disruptions and surging consumer demand fueled this inflationary spike, leading the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates in 2022 to levels not seen in 15 years (Cox, 2022).

These economic disruptions posed difficulties for everyone, but the burden was presumably heavier for those with limited financial literacy. Without adequate knowledge and preparation, such individuals might have been less equipped to navigate the challenges of recession and rising inflation. In this context, an important question arises: Did higher financial literacy protect FWB during this volatile period? If financial literacy provided a shield against financial hardship, we would expect to see an increase in pre-existing gaps in FWB indicators between groups with higher and lower financial literacy amid the challenging economic conditions of 2020–2022.

While prior research has found a link between financial literacy and FWB, most studies rely on cross-sectional data. Examining this relationship at a single point in time offers limited insight into how it changes under varying economic conditions. This study uses data from the 2017–2022 waves of the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) to address this issue. I examine whether the gaps in four FWB indicators—emergency fund availability, spending less than income, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt—between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy changed in 2020–2022 (less stable economic conditions) relative to 2017–2019 (more stable economic conditions). To explore these trends, I use difference-in-differences (DD) and event study methods.

This study contributes to the literature by moving beyond cross-sectional analyses that dominate research on the relationship between financial literacy and FWB. By leveraging repeated cross-sectional data and using DD and event study methods, this study sheds light on the role of financial literacy in shaping FWB amid varying economic conditions. The findings may offer relevant insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers interested in measuring financial literacy and examining its role in enhancing household financial security.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and discusses the background of this study. Section 3 explains the data and methods. Section 4 presents the regression estimates. Section 5 discusses the implications of the regression estimates. Lastly, Section 6 concludes with the limitations of this study and suggestions for future research.

2. Background

This section draws on economic theory and empirical research to explain the role of financial literacy and economic conditions in shaping FWB. First, I focus on the impact of financial literacy on financial behaviors and FWB. Next, I explain the influence of changing economic conditions, such as increases in unemployment and inflation, on FWB. Lastly, I discuss how financial literacy can moderate the impact of economic conditions on FWB.

2.1. Relationship Between Financial Literacy and FWB

The Life Cycle Hypothesis (Ando & Modigliani, 1963; Modigliani & Brumberg, 1954) posits that individuals save during high-income periods and dissave during low-income periods. While the theory does not explicitly mention the role of financial literacy, it is reasonable to assume that financial literacy enhances individuals’ ability to manage savings and plan for future financial needs. This assumption aligns with Huston’s (2010) conceptualization of financial literacy as a form of human capital that individuals use in financial decisionmaking to increase their expected lifetime utility from consumption. Also, the Permanent Income Hypothesis (Friedman, 1957) asserts that individuals base their consumption decisions on their expected long-term income rather than just current earnings. Here, too, financial literacy likely plays a critical role, enabling individuals to make informed decisions about savings and investments, thereby promoting stable consumption patterns and enhancing overall FWB.

Previous studies have found evidence aligning with the assumption that financial literacy promotes desirable financial behaviors. For example, Lusardi et al. (2021) found that those with higher financial literacy were more likely to have the ability to manage a medium-sized financial shock and save and plan for the future and less likely to feel constrained by debt. Similarly, Lusardi and Mitchell (2008, 2011) found evidence of the role of financial literacy in enhancing retirement preparedness. Chu et al. (2017) reported that households with higher financial literacy had a better chance of receiving a positive investment return. Furthermore, financial knowledge has been found to have a positive association with other desirable financial behaviors, such as cash flow and credit management, as well as saving and investment (Hilgert et al., 2003). Other studies have found that lower financial literacy is associated with holding a greater fraction of high-cost credit in a credit portfolio (Disney & Gathergood, 2013) and more frequent costly credit card behaviors (Mottola, 2013).

Despite the strong evidence of the link between financial literacy and financial behaviors that are presumably objective indicators of FWB, the relationship between financial literacy and subjective FWB appears to be less clear. Zhang and Chatterjee (2023) reported a positive association between financial literacy and FWB scores derived from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s FWB scale. In contrast, Xiao et al. (2014) found a negative association between objective financial knowledge (an indicator of financial literacy) and financial satisfaction (an indicator of subjective FWB). These diverging findings may be due to the differences in the conceptualization and measurement of both financial literacy and FWB, as well as variations in research design and sample characteristics.

To comprehensively understand the relationship between financial literacy, behavior, and well-being, Hwang and Park (2023) conducted a meta-analysis of fourteen peer-reviewed studies on financial literacy published in the field of consumer studies. The authors found that both subjective and objective financial knowledge are positively associated with financial behavior and FWB, with subjective knowledge showing a stronger association.

2.2. Relationship Between Economic Conditions and FWB

While much of the literature on FWB focuses on individual and household-level determinants, economic conditions can also shape the outcome (Friedline et al., 2021). Lee et al. (2023) found evidence of this relationship using World Values Survey data from 2010–2014 and 2017–2022, showing that inflation and unemployment rates have a negative relationship with financial satisfaction, while economic growth is positively associated with it. Similarly, analyzing data from a sample of Australian residents, Botha et al. (2021) reported a negative association between experiencing a labor market shock during the COVID-19 pandemic and subjective FWB. Further evidence comes from Pilkauskas et al. (2012), who used data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study to find that material hardship, an outcome related to FWB, increases with unemployment rate and rises sharply during an economic recession. In another study, Huang et al. (2016) reported that unemployment during the 2007–2009 economic recession was positively associated with food insecurity, a key dimension of material hardship.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, previous studies documented the increase in financial hardship following its onset. Karpman et al. (2020) found that in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, about 42% of nonelderly adults reported job or income losses. According to the authors’ findings, about 31% of adults reduced spending on food, 43% postponed major purchases, and 28% drew down savings or increased credit card debt, while approximately 31% experienced difficulties in paying rent, utility bills, and affording food and medical care. A Pew Research Center survey conducted in August 2020 found that about 25% of adults had difficulty paying their bills since the start of the coronavirus outbreak, 33% withdrew from savings or retirement accounts to cover usual expenses, 17% sought assistance from food banks, and 16% faced difficulty paying their rent/mortgage (Parker et al., 2020).

After these early struggles, FWB apparently improved in 2021 due to the unprecedented expansions of federal safety net programs. For instance, the federal government issued three rounds of stimulus payments, expanded unemployment insurance, distributed monthly Child Tax Credit benefits, and increased the eligibility and generosity of programs such as Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2023). Cooney et al. (2022) reported that expansions of safety net programs significantly improved the FWB of U.S. households in 2021 by reducing material hardship and increasing liquid assets and credit scores. However, as inflation rose and many pandemic relief measures expired in 2022, financial conditions worsened for many households, with rates of material hardship reaching their highest levels since the early months of the pandemic (Cooney & Shaefer, 2022). Findings by Das (2024) and Parolin et al. (2022) also indicate that while the safety net expansions reduced financial hardship, the impact was temporary, and hardship levels increased when these expansions ended.

Overall, the findings from previous studies indicate that fluctuations in economic conditions can affect various aspects of FWB.

2.3. Moderating Role of Financial Literacy in the Relationship Between Economic Conditions and FWB

Given the evidence that financial literacy has a positive relationship with FWB and that both recessionary and inflationary economic environments have negative relationships with FWB, a key question arises: How effective is financial literacy in protecting FWB during economic disruptions?

Using a panel dataset from Russia, Klapper et al. (2012) found a stronger association between financial literacy and the availability of unspent income during the 2008 financial crisis relative to prior years. Based on this evidence, the authors suggested that financial literacy equips individuals to better withstand macroeconomic shocks. In another study, Bucher-Koenen and Ziegelmeyer (2014) used a panel dataset from Germany and found that during the financial crisis, individuals with lower financial literacy were more likely to sell assets that lost value, making their losses permanent. The authors suggested that the flight from risky assets might persist, as the financial crisis could permanently affect investment behavior, resulting in lower long-term returns for those with lower financial literacy.

While previous studies provide valuable insights into the relationship between financial literacy and FWB amid economic instability, it is unclear how informative these findings are in the context of the disruptions following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. The financial crisis triggered by the pandemic differed from the 2008 financial crisis in its nature and policy response. It was marked by record-high unemployment in 2020, a high inflationary environment beginning in mid-2021, and unprecedented expansions of the social safety net between 2020 and 2022 (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2024). The structural differences between the two crises underscore the need to reevaluate the role of financial literacy in protecting FWB during periods of economic disruptions.

Empirical research on the role of financial literacy in shaping FWB in 2020 and subsequent years remains limited. Analyzing data from the 2021 wave of the TIAA Institute-GFLEC Personal Finance Index, Hasler et al. (2023) found that individuals who correctly answered more than half of the questions on financial literacy were substantially more likely to demonstrate financial resilience, remain unconstrained by debt, and engage in retirement planning, even after accounting for key demographic characteristics. In another study, Lusardi and Streeter (2023) analyzed data from the 2021 wave of the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) and found a positive association between financial literacy and different FWB indicators, such as planning for retirement, the ability to come up with $2000 within a month, and having a manageable level of debt.

While these studies provide consistent evidence of the association between financial literacy and FWB indicators, the reliance on cross-sectional data limits their ability to explore whether the relationship changed in the post-pandemic years compared to earlier years. Xiao et al. (2024) addressed this limitation by using a pooled sample from the NFCS waves conducted in 2009, 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2021. Their findings revealed a positive association between the financial capability index and financial satisfaction. Unexpectedly, they also identified a negative association between objective financial knowledge and financial satisfaction across both the pooled and annual samples. Despite variations in the relationship depending on how financial literacy was measured, the results from Xiao et al. (2024) suggest a relatively stable association between financial literacy and FWB indicators in the NFCS waves conducted before and after the pandemic.

As previous studies relied on cross-sectional or triennial data, it remains unclear whether the gaps in different FWB indicators between groups with varying levels of financial literacy changed in 2020–2022 relative to the years immediately before the pandemic. This study aims to fill this gap by utilizing annual data and using DD and event study methods to explore these trends.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED)

This study uses data from the SHED conducted by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in the U.S. The SHED has gathered data in the fourth quarter of each year since 2013. The survey questions are developed by the Federal Reserve Board staff in collaboration with other Federal Reserve System personnel, academics, and professional survey experts. Ipsos, a multinational market research and consulting firm, used its nationally representative probability-based online panel to collect data for these waves (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2024). The SHED is well-suited for this study for two reasons. First, it is one of the few publicly available datasets that include variables related to both financial literacy and FWB. Second, its annual data collection provides consistent data across years, which allows for the analysis of yearly trends before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. Key Explanatory Variable and Outcome Variables

3.2.1. Financial Literacy

The SHED contains three questions that assess knowledge of risk diversification, inflation, and interest rate. These are commonly referred to as the Big Three financial literacy questions. Responses to these questions are considered reliable indicators of financial literacy because they strongly predict financial behavior and well-being (Lusardi & Streeter, 2023). Table 1 shows these questions and the response options.

Table 1.

Big Three financial literacy questions in the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking.

As shown in the table, SHED respondents have the option to select “don’t know” in addition to providing a correct or incorrect response to the three financial literacy questions. In the 2017–2019 waves, all respondents were given the “don’t know” option; however, in the latter waves, only a randomly selected half were given this option. Tranfaglia et al. (2024) reported that removing the “don’t know” option from the financial literacy questions in the SHED led to an increase in the share of correct responses. Findings from other studies (Marley-Payne et al., 2024; Pearson et al., 2024; Wilmarth et al., 2023) indicate that “don’t know” responses do not always indicate a lack of financial literacy; rather, these responses can reflect uncertainty, lack of confidence, or hesitancy to engage with the questions. Findings presented in Appendix A Table A1 align with the findings of previous studies, showing a substantial increase in the proportion of respondents answering the three financial literacy questions correctly in the 2020–2022 waves relative to the 2017–2019 waves.

In light of these findings, it appears that treating the incorrect and “don’t know” responses as equivalent risks conflating financial literacy gaps with response behaviors unrelated to financial literacy. Therefore, in the main analysis of this study, I exclude respondents who selected “don’t know.” This approach has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, excluding respondents with “don’t know” answers potentially helps mitigate the error in measuring financial literacy gaps between two groups of respondents. On the other hand, the analytical sample is no longer nationally representative, as it excludes respondents who lacked the confidence, motivation, and/or knowledge to provide a definitive answer. Consequently, the findings of the main analysis are limited to SHED respondents who were willing or able to provide a definitive answer to the three financial literacy questions, and caution is warranted in generalizing beyond this group. Separately, I analyze data from SHED respondents who either answered correctly or selected “don’t know” for the three financial literacy questions. In other words, this alternative analysis excludes respondents who provided incorrect answers. The results of the main analysis are presented in the main text, and those of the alternative analysis are provided in Appendix B.

I operationalize financial literacy in two ways. In the first approach, I create a binary financial literacy variable that takes a value of 1 for respondents who answered all three questions correctly and 0 otherwise. In the second approach, the financial literacy variable can take an integer value between 0 and 3, depending on the number of correct answers.

3.2.2. FWB Indicators

This study uses four indicators of FWB that are consistently available across all waves of the SHED from 2017 to 2022. These variables are emergency fund availability, spending less than income, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt. Table 2 shows the operationalization of these variables. All outcomes are binary variables, where a value of 1 indicates a higher FWB.

Table 2.

Operationalizing financial well-being indicators.

3.3. Main Analytical Sample

Table 3 presents the summary statistics of the analytical sample (n = 42,661) for the emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort outcomes. The table categorizes respondents based on their financial literacy levels across two periods: 2017–2019 and 2020–2022. The sample for the three outcomes includes respondents who answered the corresponding questions and definitively (correctly or incorrectly) answered the three financial literacy questions. The sample (n = 38,501) for the no credit card debt outcome is further limited to respondents with credit cards who answered the question on their credit card debt (see Table A2 in Appendix A). The higher financial literacy group consists of those who answered all three questions correctly, and the lower financial literacy group consists of those who answered one or more of the questions incorrectly.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of the analytical sample for the emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort outcomes.

Despite some changes in the composition of each group in the two periods, the findings suggest persistent demographic and socioeconomic disparities in financial literacy. For instance, respondents in the lower financial literacy group are more likely to be female, younger, have lower incomes, and are less likely to have a college degree compared to those in the higher financial literacy group. Additionally, the lower financial literacy group included a smaller proportion of married respondents and those identifying as White. Similar differences between the two groups are observed in the analytical sample for the no credit card debt outcome (Appendix A Table A2).

3.4. Yearly Trends in FWB Indicators

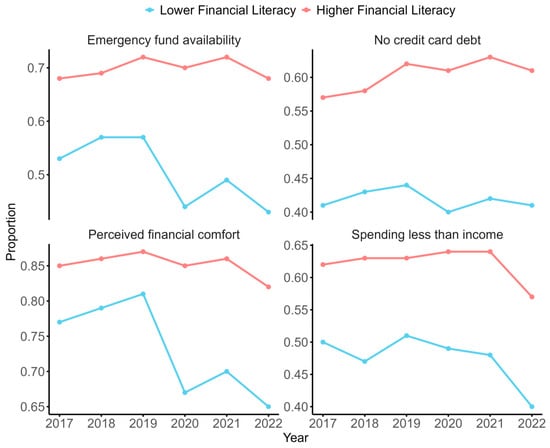

Figure 1 shows the yearly trends in the four FWB indicators for the respondents with higher and lower financial literacy. Similar to the existing literature, the findings show that respondents with higher financial literacy were substantially more likely to have emergency funds, spend less than income, have no credit card debt, and perceive financial comfort in all the years.

Figure 1.

Yearly trends in financial well-being indicators for respondents with higher and lower financial literacy. Notes: Author’s calculation based on data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) 2017–2022 waves. The analytical sample (n = 42,661) for emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort includes respondents who answered the corresponding questions and definitively answered the three financial literacy questions. The no credit card debt sample (n = 38,501) is further limited to respondents with credit cards who answered the question on their credit card debt. The higher financial literacy group includes those who answered all three questions correctly, while the lower financial literacy group includes those who answered one or more questions incorrectly. Survey weights are used in the analysis.

The gaps in three indicators—emergency fund availability, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt—between the two groups seem to have increased during the challenging economic conditions of 2020–2022 relative to the more stable conditions of 2017–2019. For the spending less than income outcome, it is less clear whether the gap between the two groups changed over time. These descriptive trends, in general, suggest that respondents with lower financial literacy experienced a greater decline in FWB in 2020–2022.

Table 4 shows how the four FWB indicators, on average, changed in 2020–2022 relative to 2017–2019 for respondents with higher and lower financial literacy. Findings suggest that the share of respondents with an emergency fund decreased by about 10 percentage points for those with lower financial literacy, while it remained unchanged for those with higher financial literacy. Additionally, the share of respondents spending less than income and perceiving financial comfort decreased by 3 and 11 percentage points, respectively, for those with lower financial literacy. In contrast, for those with higher financial literacy, these shares declined by approximately 1 percentage point and 2 percentage points, respectively. Lastly, the share of respondents having no credit card debt remained unchanged for those with lower financial literacy; on the contrary, the same increased by 3 percentage points for respondents with higher financial literacy. The last column of the table shows that the relative changes (DD) in all four FWB indicators are positive and significantly different from 0. In general, similar to the findings from Figure 1, these simple DD estimates suggest that FWB decreased to a greater extent in 2020–2022 for respondents with lower financial literacy. However, it is important to note that these results do not account for other factors that could influence the observed trends. Given the variations in the socioeconomic and demographic factors both within each group over time and between the two groups at any given point, these simple DD estimates may be biased.

Table 4.

Pre- and post-pandemic changes in financial well-being indicators for respondents with higher and lower financial literacy (simple DD estimates).

3.5. Regression Estimation

I estimate the following model using a DD approach to investigate whether there were differential pre- and post-pandemic changes in FWB indicators for respondents with varying levels of financial literacy, conditional on other factors:

where refers to the value of the outcome for respondent responding in year . represents year fixed effects. represents state fixed effects. refers to the level of financial literacy for respondent . is a dummy variable that takes a value of 1 for 2020–2022 and 0 for 2017–2019. refers to socioeconomic control variables (age, gender, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, annual household income category, marital status, employment status, and presence of children aged below 18). is the error term. The coefficient of interest in Equation (1) is , which, conditional on other factors, is an estimator of the following (for the binary operationalization of financial literacy):

Next, I estimate the following model using an event study approach to explore how the gaps in FWB indicators between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy evolved over the years:

refers to 2019 (reference year). −1 and −2 refer to 2018 and 2017, respectively, and 1, 2, and 3 refer to 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively. The coefficient of interest in Equation (2) is , which, conditional on other factors, is an estimator of the following (for the binary operationalization of financial literacy):

In simpler words, the estimated values of show how the gaps in FWB indicators between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy, conditional on other factors, varied in different years (i.e., 2017, 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2022) relative to 2019, the year immediately preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. A positive indicates that the gap in the outcome between the two groups was wider in year τ relative to 2019. A negative suggests that the gap was narrower, while a zero suggests no difference in the gap compared to 2019.

For estimating both Equations (1) and (2), I use linear regression with survey weights and heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors.

4. Regression Estimates

In this section, first, I explain the findings of the main analysis which includes SHED respondents with definitive answers to the three financial literacy questions. Table 5 presents estimates of the coefficient of interest () in Equation (1). Here, estimates whether the gaps in FWB indicators between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy, on average, changed in 2020–2022 relative to 2017–2019 (conditional on other factors). A positive indicates that the gap widened, a negative indicates that the gap narrowed, and a of zero indicates that gap remained the same in 2020–2022 relative to 2017–2019. In this estimation, financial literacy is operationalized as a binary variable. Columns (1)–(4) correspond to the four FWB indicators: emergency fund availability, spending less than income, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt. Appendix A Table A3 reports the estimated coefficients of all the predictors in Equation (1).

Table 5.

Difference in pre- and post-pandemic changes in financial well-being indicators between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy (DD estimates with binary operationalization of financial literacy).

The estimated coefficient for emergency fund availability is 0.06, which is smaller than the one (0.10) found in the simple DD estimation (Table 4) that did not control for other factors. Nevertheless, the coefficient remains statistically significant at the 5% level. A similar pattern is observed in the estimated coefficients for perceived financial comfort (0.06) and no credit card debt (0.03), both of which are positive and significant at the 5% level, but smaller than the ones from the simple DD estimation (0.09 and 0.04, respectively, in Table 4). In contrast, the estimated coefficient for spending less than income (−0.01) is not statistically significant, whereas the simple DD estimate (0.02) for the same outcome was significant at the 10% level. Taken together, these findings indicate that although accounting for socioeconomic and demographic factors and state and year fixed effects reduces the estimated coefficients to some extent, the coefficients remain positive and statistically significant for three FWB indicators (emergency fund availability, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt).

To assess the robustness of these findings, I re-estimate Equation (1) using an alternative measure of financial literacy, operationalized based on the number of correct responses to the three questions shown in Table 1. Table 6 shows the estimates of the coefficient of interest (), and Appendix A Table A4 shows the full set of coefficients for this estimation. The estimated coefficients for emergency fund availability (0.03) and perceived financial comfort (0.04) are positive and significant at the 5% level. However, the coefficients for the other two FWB indicators are statistically insignificant.

Table 6.

Difference in pre- and post-pandemic changes in financial well-being indicators between respondents with differential financial literacy (DD estimates with alternative operationalization of financial literacy).

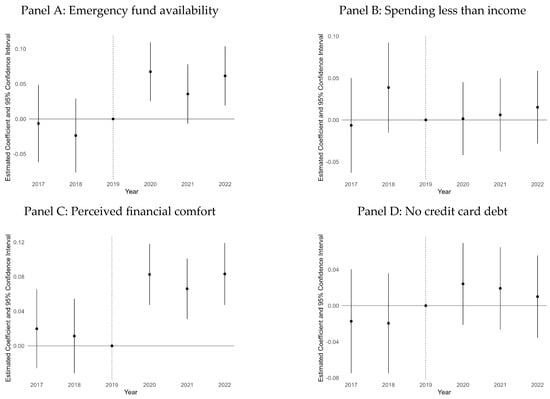

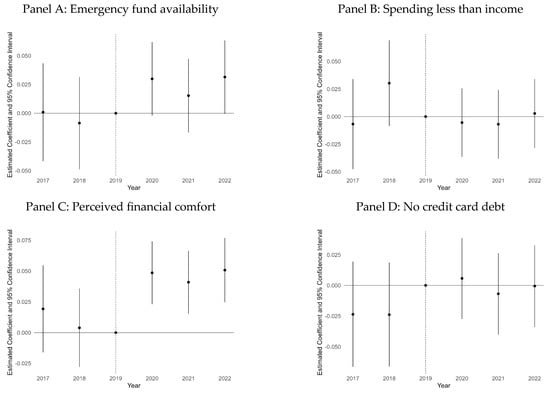

To investigate yearly variations in the relationship between financial literacy and FWB indicators, I estimate the event study specification shown in Equation (2). The coefficient of interest is , which estimates the changes in the gaps in FWB indicators between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy in different years (2017, 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2022) relative to 2019 (the reference year). A positive value of indicates that the gap between the two groups in year is greater than the gap in 2019, a negative value indicates that the gap is smaller, and a value of zero indicates that the gap is the same as in 2019. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the point estimates and 95% confidence intervals of estimated with binary and alternative operationalizations of financial literacy, respectively. Each figure includes four panels (A–D) corresponding to the four FWB indicators. Table A5 and Table A6 in Appendix A show the coefficients of all the predictors in Equation (2) estimated with binary and alternative operationalizations of financial literacy, respectively.

Figure 2.

Difference in yearly changes in financial well-being indicators relative to 2019 between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy (event study estimates with binary operationalization of financial literacy). Notes: Author’s calculation based on data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) 2017–2022 waves. The analytical sample (n = 42,661) for emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort includes respondents who answered the corresponding questions and definitively answered the three financial literacy questions. The no credit card debt sample (n = 38,501) is further limited to respondents with credit cards who answered the question on their credit card debt. The figure shows the point estimates (dots) of the coefficient of interest in Equation (2) for different years, with 2019 as the reference year, while the bars represent the 95% confidence intervals for these estimate. Survey weights and heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors are used in the analysis.

Figure 3.

Difference in yearly changes in financial well-being indicators relative to 2019 between respondents with differential financial literacy (event study estimates with alternative operationalization of financial literacy). Notes: Author’s calculation based on data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) 2017–2022 waves. The analytical sample (n = 42,661) for emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort includes respondents who answered the corresponding questions and definitively answered the three financial literacy questions. The no credit card debt sample (n = 38,501) is further limited to respondents with credit cards who answered the question on their credit card debt. The figure shows the point estimates (dots) of the coefficient of interest in Equation (2) for different years, with 2019 as the reference year, while the bars represent the 95% confidence intervals for these estimate. Survey weights and heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors are used in the analysis.

For emergency fund availability, the estimated coefficients in the Panel A of Figure 2 are 0.07 in 2020, 0.03 in 2021, and 0.06 in 2022. The 2020 and 2022 estimates are statistically significant at the 5% level, while the 2021 estimate is not statistically significant at conventional levels (p-value = 0.11). The coefficients for perceived financial comfort (panel C) are relatively more stable across years, estimated at 0.08 in 2020, 0.06 in 2021, and 0.08 in 2022, all statistically significant at the 5% level. In contrast, the estimated coefficients for spending less than income (panel B) and no credit card debt (panel D) are not significantly different from zero in any year. The results across the four panels of Figure 3 are largely consistent with those in Figure 2.

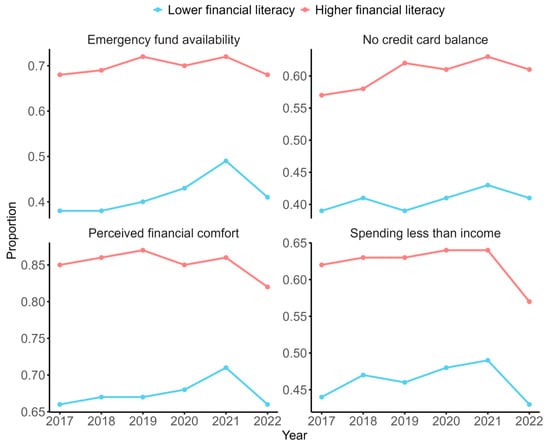

Appendix B presents the results of the additional analysis, which includes SHED respondents who selected either the correct answer or “don’t know” to the three financial literacy questions. In this analysis, the higher financial literacy group consists of those who answered all three questions correctly, while the lower financial literacy group includes those who selected “don’t know” for at least one question. Based on the summary statistics in Table A7 and Table A8, those who chose at least one “don’t know” are, on average, more demographically and socioeconomically similar to those who answered at least one question incorrectly (see Table 3 and Appendix A Table A2). Surprisingly, descriptive findings in Figure A1 suggest that the pre-existing gaps in FWB indicators between the two groups either decreased or remained the same in 2020–2022. The simple DD findings in Table A9 align with findings in Figure A1. Also, regression estimates from Equations (1) and (2) presented in Table A10, Table A11, Table A12 and Table A13 broadly support the descriptive findings, showing evidence of either a decreasing gap or no change in the gap. Some exceptions are the results of the DD analyses shown in Table A10 and Table A11, which suggest a widening gap in no credit card debt, though the event study estimates in Table A12 and Table A13 do not support this trend. Overall, the findings of the alternative analysis diverge from the ones in the main analysis.

5. Discussion

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic brought about unprecedented challenges for households in the U.S., including a record-high increase in the unemployment rate followed by a substantial rise in the cost of living. While expansions of safety net programs helped protect FWB, these measures might have provided only temporary relief. Amid the challenging economic environment, what role did financial literacy play in protecting FWB? This study investigated whether the gaps in four FWB indicators—emergency fund availability, spending less than income, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt—between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy changed during the difficult economic conditions of 2020–2022 compared to the more stable period of 2017–2019, using data from the 2017–2022 waves of the SHED.

The descriptive findings align with existing literature, showing that respondents with higher financial literacy were substantially more likely to have emergency funds, spend less than their income, perceive financial comfort, and carry no credit card debt consistently from 2017 to 2022. Beyond the descriptive analysis, this study used DD and event study methods to investigate these trends.

The main analysis focused on respondents who provided definitive answers (correct or incorrect) to the Big Three financial literacy questions. The findings indicate that the pre-existing gaps in emergency fund availability and perceived financial comfort between respondents with higher and lower financial literacy widened in 2020–2022, while the gap in spending less than income remained stable over time. For the no credit card debt outcome, the evidence is mixed: DD estimates suggest a widening gap, but event study results do not support this finding.

These results align with those of previous studies, such as Klapper et al. (2012), who found that financial literacy bolstered financial resilience during the 2008 financial crisis, and Bucher-Koenen and Ziegelmeyer (2014), who reported that lower financial literacy led to suboptimal investment decisions with potentially lasting consequences. Although this study investigated changes in FWB indicators different from the ones examined by prior studies, the findings of the main analysis are broadly in a similar direction by suggesting that financial literacy can protect some aspects of FWB during a challenging economic environment.

From a policy perspective, these findings imply that expansions of financial literacy programs can help improve the FWB of individuals and households amid varying economic conditions. However, the results also indicate that financial literacy alone may not be sufficient to fully protect FWB from economic disruptions. Therefore, policy initiatives should complement financial education with structural interventions such as targeted savings incentives and credit management programs to strengthen financial security.

To complement the main analysis, a separate analysis was conducted using data from SHED respondents who either answered the Big Three questions correctly or selected “don’t know.” The decision to separately explore the trends of those who selected incorrect answers and those who selected “don’t know” against those who selected correct answers was guided by recent literature suggesting that “don’t know” responses do not always reflect a lack of financial literacy and, thus, should not be grouped together with incorrect responses. Surprisingly, the results of the additional analysis differed in direction from those of the main analysis. One possible explanation is that respondents who selected “don’t know” might have behaved differently during the challenging economic environment of 2020–2022. They might have been more aware of their lack of understanding of fundamental financial concepts than those who answered incorrectly, which could have led to more cautious financial decisions.

The diverging results of the two analyses raise important questions about how different responses to the financial literacy questions should be classified and how such classifications may affect empirical estimates of the relationship between financial literacy and FWB. In particular, more research is needed to better understand the impact of including “don’t know” responses in measuring financial literacy. As recommended by Wilmarth et al. (2023), future studies should investigate the empirical and ethical implications of including or excluding this response option. If researchers determine that retaining the “don’t know” option offers more advantages than disadvantages, it will be crucial to find a way to differentiate between those who genuinely do not know the answers and those who select “don’t know” due to other factors. As suggested by Pearson et al. (2024), survey designers may consider implementing strategies such as incorporating confidence ratings to enhance the accuracy of financial literacy measurement.

Beyond the challenges of more accurately measuring financial literacy, there is a pressing need for a comprehensive framework that explains its role in shaping different aspects of FWB. Such a framework should account for factors operating at different levels, including individual financial knowledge, confidence, and behaviors, household financial dynamics, and structural factors. A framework integrating all these factors may give us a clearer understanding of how financial literacy interacts with factors at various levels to shape FWB.

6. Conclusions

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the use of repeated cross-sectional data (instead of panel data) limits the ability to draw causal conclusions about the relationship between financial literacy and FWB amid varying economic conditions. Second, reliance on self-reported data might have introduced biases, as individuals may not accurately report their financial conditions. Third, this study operationalized financial literacy based on the responses to the Big Three financial literacy questions. Although these questions have been shown to be valid measures of financial literacy across the world, they focus only on objective financial knowledge and do not measure subjective financial knowledge. Previous studies suggest that subjective financial knowledge can have a greater impact on financial behaviors than objective financial knowledge (Hwang & Park, 2023). Lastly, due to data limitations, this study did not explore potential mechanisms explaining the observed trends. Future research should address these limitations by combining survey data (for objective and subjective financial literacy, as well as subjective FWB) with credit bureau and administrative data (for objective FWB indicators such as credit score, credit card debt, and income) for a panel of respondents. This approach would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how financial literacy plays a role in shaping FWB amid more and less stable economic environments.

Despite its limitations, this study contributes to the literature by examining the relationship between financial literacy and FWB across varying economic conditions from 2017 to 2022. The divergence in findings between the main and additional analyses suggests that current approaches to measuring and operationalizing financial literacy may need refinement. Consistent with recent studies, the results indicate that combining “don’t know” responses with incorrect ones may obscure meaningful behavioral differences and lead to inaccurate estimates of the relationship between financial literacy and FWB. More research is needed to better understand the conceptual and empirical implications of including or excluding a “don’t know” response option and to develop better methods for distinguishing between higher and lower levels of financial literacy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study analyzed publicly available anonymized secondary data (the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking conducted by the Federal Reserve Board). The data are publicly available. No human participants or animals were involved, so no IRB approval was required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

This article uses data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking conducted by the Federal Reserve Board. The data are publicly available at the following link: https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/shed_data.htm.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declares no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| DD | Difference-in-differences |

| FWB | Financial Well-Being |

| GFLEC | Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center |

| NFCS | National Financial Capability Study |

| SHED | Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| TIAA | Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Distribution of responses to the Big Three financial literacy questions in the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking 2017–2022 waves.

Table A1.

Distribution of responses to the Big Three financial literacy questions in the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking 2017–2022 waves.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 12,447 | 11,316 | 12,173 | 11,648 | 11,874 | 11,667 |

| Risk Diversification | ||||||

| Not In Universe (not asked) | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Don’t know | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| Refused | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| True | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| False | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| Inflation | ||||||

| Not In Universe (not asked) | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Don’t know | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Refused | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| More than today | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Exactly the same | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Less than today | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| Interest | ||||||

| Not In Universe (not asked) | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Don’t know | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Refused | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| More than $102 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| Exactly $102 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Less than $102 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

Notes: Correct answers are shown in bold. Numbers are rounded to two decimal places.

Table A2.

Summary statistics of the analytical sample for the no credit card debt outcome.

Table A2.

Summary statistics of the analytical sample for the no credit card debt outcome.

| Lower Financial Literacy | Higher Financial Literacy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–2019 | 2020–2022 | 2017–2019 | 2020–2022 | |

| Sample size | 2720 | 6327 | 13,106 | 16,348 |

| Female | 0.48 (0.50) | 0.58 (0.49) | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.44 (0.50) |

| White | 0.60 (0.49) | 0.56 (0.50) | 0.77 (0.42) | 0.73 (0.44) |

| Black | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.06 (0.23) | 0.07 (0.25) |

| Hispanic | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.08 (0.28) | 0.11 (0.31) |

| Other | 0.09 (0.28) | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.10 (0.29) |

| College | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.57 (0.50) | 0.54 (0.50) |

| Age | 49.42 (16.80) | 48.73 (17.44) | 51.49 (16.50) | 51.13 (17.14) |

| Income below $50k | 0.30 (0.46) | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.13 (0.34) |

| Income between $50k and $100k | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.35 (0.48) | 0.28 (0.45) | 0.28 (0.45) |

| Income above $100k | 0.37 (0.48) | 0.34 (0.47) | 0.57 (0.49) | 0.59 (0.49) |

| Employed | 0.69 (0.46) | 0.65 (0.48) | 0.70 (0.46) | 0.69 (0.46) |

| Unemployed (not retired, no disabilities) | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.07 (0.25) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.04 (0.20) |

| Retired | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.22 (0.41) | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.24 (0.43) |

| Has disabilities | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.12) |

| Married | 0.63 (0.48) | 0.56 (0.50) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.67 (0.47) |

| Presence of children aged below 18 | 0.28 (0.45) | 0.30 (0.46) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.26 (0.44) |

Notes: Author’s calculation based on data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking 2017–2022 waves. The analytical sample (n = 38,501) consists of respondents with at least one credit card who answered questions on emergency fund availability, spending less than income, perceived financial comfort, and no credit card debt and provided definitive responses to the three questions on financial literacy. Survey weights are used in the analysis. Numbers are rounded to two decimal places.

Table A3.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (1) (financial literacy operationalized as a binary variable).

Table A3.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (1) (financial literacy operationalized as a binary variable).

| (1) Emergency Fund Availability | (2) Spending Less Than Income | (3) Perceived Financial Comfort | (4) No Credit Card Debt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.31 *** (0.06) | 0.48 *** (0.06) | 0.60 *** (0.04) | 0.49 *** (0.07) |

| FL | 0.03 ** (0.01) | 0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.02 * (0.01) | 0.07 *** (0.01) |

| Year_2018 | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.004 (0.01) | 0.004 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Year_2019 | 0.02 * (0.01) | −0.002 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.03 ** (0.01) |

| Year_2020 | −0.04 ** (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | −0.07 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Year_2021 | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | −0.05 *** (0.01) | 0.04 * (0.02) |

| Year_2022 | −0.06 *** (0.01) | −0.06 *** (0.01) | −0.10 *** (0.01) | 0.02 (0.02) |

| Alabama | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Arkansas | −0.14 * (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.08) |

| Arizona | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.15 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| California | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Colorado | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.07) |

| Connecticut | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.05 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| District of Columbia | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.13 † (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Delaware | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.18 ** (0.07) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.05 (0.08) |

| Florida | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.16 ** (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Georgia | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.11 † (0.06) | 0.004 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Hawaii | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.11 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.08) |

| Iowa | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.08) |

| Idaho | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.10 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.08) |

| Illinois | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Indiana | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Kansas | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.0004 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.08) |

| Kentucky | −0.12 † (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.0002 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Louisiana | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.11 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Massachusetts | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Maryland | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.07) |

| Maine | 0.07 (0.07) | −0.07 (0.07) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.08) |

| Michigan | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.15 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Minnesota | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Missouri | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Mississippi | −0.10 (0.07) | −0.13 * (0.07) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.16 * (0.08) |

| Montana | −0.17 * (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.08) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.09) |

| North Carolina | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.12 † (0.07) |

| North Dakota | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.15 † (0.08) |

| Nebraska | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.12 † (0.06) | 0.004 (0.05) | −0.12 (0.08) |

| New Hampshire | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.08) |

| New Jersey | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| New Mexico | −0.13 † (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.07) | −0.002 (0.05) | −0.11 (0.08) |

| Nevada | −0.07 (0.07) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.13 † (0.08) |

| New York | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Ohio | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.08 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Oklahoma | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.09 † (0.05) | −0.13 (0.08) |

| Oregon | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.04 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Pennsylvania | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Rhode Island | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.08 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.08) |

| South Carolina | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| South Dakota | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.19 ** (0.07) | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.002 (0.08) |

| Tennessee | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.10 (0.07) |

| Texas | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Utah | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Virginia | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.07) |

| Vermont | −0.04 (0.08) | −0.05 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.09) |

| Washington | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Wisconsin | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| West Virginia | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.19 ** (0.07) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.08) |

| Wyoming | −0.12 (0.08) | −0.27 ** (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.10) |

| Female | −0.001 (0.01) | −0.02 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.004) | −0.03 *** (0.01) |

| Black | −0.09 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.27 *** (0.01) |

| Hispanic | −0.03 ** (0.01) | −0.03 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.13 *** (0.01) |

| Other | −0.004 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 † (0.01) | 0.06 *** (0.01) |

| College | 0.13 *** (0.01) | 0.03 *** (0.01) | 0.07 *** (0.004) | 0.13 *** (0.01) |

| Age | 0.003 *** (0.0002) | 0.001 *** (0.0002) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | −0.001 *** (0.0002) |

| Income between $50k and $100k | 0.12 *** (0.01) | 0.13 *** (0.01) | 0.19 *** (0.01) | 0.01 † (0.01) |

| Income above $100k | 0.22 *** (0.01) | 0.24 *** (0.01) | 0.28 *** (0.01) | 0.10 *** (0.01) |

| Unemployed (not retired, no disabilities) | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.03 ** (0.01) | 0.12 *** (0.01) |

| Retired | 0.09 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.07 *** (0.01) | 0.20 *** (0.01) |

| Has disabilities | −0.18 *** (0.02) | −0.13 *** (0.02) | −0.20 *** (0.02) | −0.06 * (0.02) |

| Married | 0.06 *** (0.01) | 0.04 *** (0.01) | 0.05 *** (0.01) | 0.002 (0.01) |

| Presence of children aged below 18 | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.09 *** (0.01) | −0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.07 *** (0.01) |

| FL × Post | 0.06 *** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.06 *** (0.01) | 0.03 * (0.01) |

| Observations | 42,661 | 42,661 | 42,661 | 38,501 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

Notes: Author’s calculation based on data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) 2017–2022 waves. The analytical sample (n = 42,661) for emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort includes respondents who answered the corresponding questions and definitively answered the three financial literacy questions. The no credit card debt sample (n = 38,501) is further limited to respondents with credit cards who answered the question on their credit card debt. Survey weights and heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors are used in the analysis. Most numbers are rounded to two decimal places; however, small coefficients and standard errors are reported with greater precision to ensure clarity. Significance codes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, † p < 0.1.

Table A4.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (1) (financial literacy operationalized based on the number of correct responses to the three financial literacy questions).

Table A4.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (1) (financial literacy operationalized based on the number of correct responses to the three financial literacy questions).

| (1) Emergency Fund Availability | (2) Spending Less Than Income | (3) Perceived Financial Comfort | (4) No Credit Card Debt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.27 *** (0.06) | 0.39 *** (0.06) | 0.63 *** (0.05) | 0.43 *** (0.08) |

| FL | 0.02 ** (0.01) | 0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.02 ** (0.01) | 0.04 *** (0.01) |

| Year_2018 | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.004 (0.01) | 0.004 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Year_2019 | 0.02 * (0.01) | −0.002 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.03 ** (0.01) |

| Year_2020 | −0.07 * (0.03) | 0.05 † (0.03) | −0.12 *** (0.02) | −0.004 (0.03) |

| Year_2021 | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.05 † (0.03) | −0.10 *** (0.02) | 0.02 (0.03) |

| Year_2022 | −0.09 ** (0.03) | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.15 *** (0.02) | 0.001 (0.03) |

| Alabama | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.08) |

| Arkansas | −0.14 * (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.08) |

| Arizona | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.15 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| California | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Colorado | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.07) |

| Connecticut | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.06 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| District of Columbia | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.13 † (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Delaware | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.07) | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.05 (0.08) |

| Florida | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.16 ** (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Georgia | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.11 † (0.06) | 0.003 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Hawaii | −0.03 (0.07) | −0.11 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.08) |

| Iowa | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.08) |

| Idaho | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.08) |

| Illinois | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Indiana | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Kansas | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.0001 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.08) |

| Kentucky | −0.12 † (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.001 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Louisiana | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Massachusetts | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Maryland | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Maine | 0.07 (0.07) | −0.07 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.08) |

| Michigan | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.15 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Minnesota | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Missouri | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Mississippi | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.13 * (0.07) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.16 * (0.08) |

| Montana | −0.17 * (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.08) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.19 * (0.09) |

| North Carolina | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.12 † (0.07) |

| North Dakota | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.15 † (0.08) |

| Nebraska | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.12 † (0.06) | 0.003 (0.05) | −0.12 (0.08) |

| New Hampshire | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.08) |

| New Jersey | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| New Mexico | −0.13 † (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.07) | −0.004 (0.05) | −0.12 (0.08) |

| Nevada | −0.07 (0.07) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.14 † (0.08) |

| New York | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Ohio | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.08 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Oklahoma | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.12 † (0.06) | −0.09 † (0.05) | −0.13 (0.08) |

| Oregon | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.04 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Pennsylvania | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Rhode Island | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.07 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.13 (0.08) |

| South Carolina | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| South Dakota | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.19 * (0.07) | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.002 (0.08) |

| Tennessee | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.10 (0.07) |

| Texas | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Utah | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Virginia | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.07) |

| Vermont | −0.04 (0.08) | −0.04 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.09) |

| Washington | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Wisconsin | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| West Virginia | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.19 ** (0.07) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.08) |

| Wyoming | −0.11 (0.08) | −0.27 ** (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.03 (0.10) |

| Female | −0.003 (0.01) | −0.02 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.004) | −0.03 *** (0.01) |

| Black | −0.09 *** (0.01) | −0.03 *** (0.01) | −0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.27 *** (0.01) |

| Hispanic | −0.03 *** (0.01) | −0.03 ** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.13 *** (0.01) |

| Other | −0.004 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 † (0.01) | 0.06 *** (0.01) |

| College | 0.13 *** (0.01) | 0.03 *** (0.01) | 0.07 *** (0.004) | 0.14 *** (0.01) |

| Age | 0.003 *** (0.0002) | 0.001 *** (0.0002) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | −0.001 *** (0.0002) |

| Income between $50k and $100k | 0.12 *** (0.01) | 0.13 *** (0.01) | 0.19 *** (0.01) | 0.01 † (0.01) |

| Income above $100k | 0.23 *** (0.01) | 0.24 *** (0.01) | 0.28 *** (0.01) | 0.10 *** (0.01) |

| Unemployed (not retired, no disabilities) | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.03 ** (0.01) | 0.12 *** (0.01) |

| Retired | 0.09 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.07 *** (0.01) | 0.20 *** (0.01) |

| Has disabilities | −0.18 *** (0.02) | −0.13 *** (0.02) | −0.20 *** (0.02) | −0.06 * (0.02) |

| Married | 0.06 *** (0.01) | 0.04 *** (0.01) | 0.05 *** (0.01) | 0.003 (0.01) |

| Presence of children aged below 18 | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.08 *** (0.01) | −0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.07 *** (0.01) |

| FL × Post | 0.03 ** (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.04 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Observations | 42,661 | 42,661 | 42,661 | 38,501 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.12 |

Notes: Author’s calculation based on data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) 2017–2022 waves. The analytical sample (n = 42,661) for emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort includes respondents who answered the corresponding questions and definitively answered the three financial literacy questions. The no credit card debt sample (n = 38,501) is further limited to respondents with credit cards who answered the question on their credit card debt. Survey weights and heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors are used in the analysis. Most numbers are rounded to two decimal places; however, small coefficients and standard errors are reported with greater precision to ensure clarity. Significance codes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, † p < 0.1.

Table A5.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (2) (financial literacy operationalized as a binary variable).

Table A5.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (2) (financial literacy operationalized as a binary variable).

| (1) Emergency Fund Availability | (2) Spending Less Than Income | (3) Perceived Financial Comfort | (4) No Credit Card Debt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.31 *** (0.06) | 0.49 *** (0.06) | 0.59 *** (0.05) | 0.50 *** (0.07) |

| FL | 0.04 * (0.02) | 0.04 * (0.02) | −0.03 * (0.01) | 0.08 *** (0.02) |

| Year_2018 | 0.03 (0.03) | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.03) |

| Year_2019 | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.03) |

| Year_2020 | −0.05 * (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.07 *** (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Year_2021 | −0.0001 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.03 † (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) |

| Year_2022 | −0.06 ** (0.02) | −0.07 ** (0.02) | −0.09 *** (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) |

| Alabama | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Arkansas | −0.14 * (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.08) |

| Arizona | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.15 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| California | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Colorado | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.07) |

| Connecticut | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.05 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| District of Columbia | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.13 † (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Delaware | −0.07 (0.07) | −0.18 ** (0.07) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.05 (0.08) |

| Florida | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.16 ** (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Georgia | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.11 † (0.06) | 0.004 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Hawaii | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.11 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.08) |

| Iowa | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.08) |

| Idaho | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.10 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.08) |

| Illinois | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Indiana | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Kansas | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.0004 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.08) |

| Kentucky | −0.12 † (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.0002 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Louisiana | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.11 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Massachusetts | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Maryland | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.07) |

| Maine | 0.07 (0.07) | −0.07 (0.07) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.08) |

| Michigan | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.15 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Minnesota | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Missouri | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Mississippi | −0.10 (0.07) | −0.13 * (0.07) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.16 * (0.08) |

| Montana | −0.17 * (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.08) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.09) |

| North Carolina | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.12 † (0.07) |

| North Dakota | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.15 † (0.08) |

| Nebraska | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.12 † (0.06) | 0.004 (0.05) | −0.12 (0.08) |

| New Hampshire | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.08) |

| New Jersey | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| New Mexico | −0.13 † (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.07) | −0.002 (0.05) | −0.11 (0.08) |

| Nevada | −0.07 (0.07) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.13 † (0.08) |

| New York | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Ohio | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.08 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Oklahoma | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.09 † (0.05) | −0.13 (0.08) |

| Oregon | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.04 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Pennsylvania | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Rhode Island | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.08 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.08) |

| South Carolina | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| South Dakota | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.19 ** (0.07) | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.001 (0.08) |

| Tennessee | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.10 (0.07) |

| Texas | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Utah | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Virginia | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.07) |

| Vermont | −0.04 (0.08) | −0.04 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.09) |

| Washington | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Wisconsin | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| West Virginia | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.19 ** (0.07) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.08) |

| Wyoming | −0.12 (0.08) | −0.27 ** (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.10) |

| Female | −0.001 (0.01) | −0.02 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.004) | −0.03 *** (0.01) |

| Black | −0.09 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.27 *** (0.01) |

| Hispanic | −0.03 *** (0.01) | −0.03 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.13 *** (0.01) |

| Other | −0.004 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 † (0.01) | 0.06 *** (0.01) |

| College | 0.13 *** (0.01) | 0.03 *** (0.01) | 0.07 *** (0.004) | 0.13 *** (0.01) |

| Age | 0.003 *** (0.0002) | 0.001 *** (0.0002) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | −0.001 *** (0.0002) |

| Income between $50k and $100k | 0.12 *** (0.01) | 0.13 *** (0.01) | 0.19 *** (0.01) | 0.01 † (0.01) |

| Income above $100k | 0.22 *** (0.01) | 0.24 *** (0.01) | 0.28 *** (0.01) | 0.10 *** (0.01) |

| Unemployed (not retired, no disabilities) | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.03 ** (0.01) | 0.12 *** (0.01) |

| Retired | 0.09 *** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.07 *** (0.01) | 0.20 *** (0.01) |

| Has disabilities | −0.18 *** (0.02) | −0.13 *** (0.02) | −0.20 *** (0.02) | −0.06 * (0.02) |

| Married | 0.06 *** (0.01) | 0.03 *** (0.01) | 0.05 *** (0.01) | 0.002 (0.01) |

| Presence of children aged below 18 | −0.07 *** (0.01) | −0.09 *** (0.01) | −0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.07 *** (0.01) |

| FL × Year_2017 | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.03) |

| FL × Year_2018 | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.03) |

| FL × Year_2020 | 0.07 ** (0.02) | 0.001 (0.02) | 0.08 *** (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) |

| FL × Year_2021 | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.06 *** (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) |

| FL × Year_2022 | 0.06 ** (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.08 *** (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Observations | 42,661 | 42,661 | 42,661 | 38,501 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

Notes: Author’s calculation based on data from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) 2017–2022 waves. The analytical sample (n = 42,661) for emergency fund availability, spending less than income, and perceived financial comfort includes respondents who answered the corresponding questions and definitively answered the three financial literacy questions. The no credit card debt sample (n = 38,501) is further limited to respondents with credit cards who answered the question on their credit card debt. Survey weights and heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors are used in the analysis. Most numbers are rounded to two decimal places; however, small coefficients and standard errors are reported with greater precision to ensure clarity. Significance codes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, † p < 0.1.

Table A6.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (2) (financial literacy operationalized based on the number of correct responses to the three financial literacy questions).

Table A6.

Estimated coefficients of the predictors in the model shown in Equation (2) (financial literacy operationalized based on the number of correct responses to the three financial literacy questions).

| (1) Emergency Fund Availability | (2) Spending Less Than Income | (3) Perceived Financial Comfort | (4) No Credit Card Debt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.26 *** (0.07) | 0.43 *** (0.07) | 0.60 *** (0.06) | 0.45 *** (0.09) |

| FL | 0.03 † (0.01) | 0.04 ** (0.01) | −0.03 * (0.01) | 0.06 *** (0.01) |

| Year_2018 | 0.04 (0.06) | −0.11 † (0.06) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.07) |

| Year_2019 | 0.03 (0.06) | −0.02 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.05) | −0.03 (0.06) |

| Year_2020 | −0.07 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.05) | −0.10 * (0.05) | −0.04 (0.05) |

| Year_2021 | −0.01 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) |

| Year_2022 | −0.09 † (0.05) | −0.08 (0.05) | −0.13 ** (0.05) | −0.02 (0.05) |

| Alabama | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.08) |

| Arkansas | −0.14 * (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.08) |

| Arizona | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.15 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| California | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Colorado | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.07) |

| Connecticut | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.06 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| District of Columbia | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.13 † (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Delaware | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.07) | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Florida | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.16 ** (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Georgia | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.11 † (0.06) | 0.003 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Hawaii | −0.03 (0.07) | −0.11 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.08) |

| Iowa | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.08) |

| Idaho | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.08) |

| Illinois | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Indiana | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Kansas | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.0001 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.08) |

| Kentucky | −0.12 † (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.001 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Louisiana | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Massachusetts | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Maryland | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Maine | 0.07 (0.07) | −0.07 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.08) |

| Michigan | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| Minnesota | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Missouri | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Mississippi | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.16 * (0.08) |

| Montana | −0.17 * (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.08) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.18 * (0.09) |

| North Carolina | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.14 * (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.12 † (0.07) |

| North Dakota | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.15 † (0.08) |

| Nebraska | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.12 † (0.06) | 0.003 (0.05) | −0.12 (0.08) |

| New Hampshire | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.08) |

| New Jersey | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.07) |

| New Mexico | −0.13 † (0.07) | −0.15 * (0.07) | −0.003 (0.05) | −0.11 (0.08) |

| Nevada | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.14 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.13 † (0.08) |

| New York | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Ohio | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.08 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Oklahoma | −0.15 * (0.06) | −0.12 † (0.06) | −0.09 † (0.05) | −0.13 (0.08) |

| Oregon | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | 0.04 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Pennsylvania | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Rhode Island | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.07 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.13 (0.08) |

| South Carolina | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.07 (0.07) |

| South Dakota | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.19 * (0.07) | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.001 (0.08) |

| Tennessee | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.10 (0.07) |

| Texas | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Utah | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.13 * (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Virginia | −0.07 (0.06) | −0.12 * (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.07) |

| Vermont | −0.04 (0.08) | −0.04 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.09) |

| Washington | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.07) |

| Wisconsin | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.10 † (0.06) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| West Virginia | −0.16 * (0.07) | −0.19 ** (0.07) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.08) |

| Wyoming | −0.11 (0.08) | −0.27 ** (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.03 (0.10) |