2.2.1. Impact of CVC Holdings on the Labor Income Share

The labor income share, which is the labor pay component of the total factor compensation, is a key indicator for evaluating a company’s income distribution. According to the resource-based view theory, the competitive advantage of an enterprise comes from its unique resources and capabilities. CVC, as a strategic investment behavior of enterprises, may provide investees with more targeted input resources, drawing upon the parent company’s resources and expertise. If CVC owns more equity in the investee, the interests of the parent company and the investee will converge, and it is more likely to provide technical and resource support for the investee and reduce the technical uncertainty of the investee’s R&D investment (

Dushnitsky et al., 2021). Considering a firm’s ability to pay, the parent or affiliated firms behind CVC usually have higher productivity, and they are also able to provide higher levels of wage compensation. In addition, the entry of CVC increases competition in the market, and whether it is to enhance the firm’s competitiveness and incentivize employees or if the firm is competing for talent (

Decreuse & Maarek, 2015), CVC investors have incentives to increase compensation.

While the investee may be able to leverage the parent company’s complementary assets to create more value, this does not necessarily guarantee that the investee will derive more value from them. Resource dependence theory suggests that organizations depend on other organizations in order to obtain key resources, and that this dependence affects the organization’s behavior and decision making. Owing to the investee’s high dependence on the parent company’s resources, the two parties may be in an unequal position and, as the CVC’s holdings increase, the parent company tends to engage in potentially opportunistic behaviors, such as stealing the investee’s core technology, if the investee is unable to protect its interests through environmental conditions or deal structures (

Benson & Ziedonis, 2010). Second, investors generally have no incentive to nurture the independent commercialization capabilities of investee firms but rather use complementary assets to directly support the activities of investee firms. CVC may place more emphasis on linking the technological innovation outputs of investee firms to the products of their parent firms than on solving the problem from the perspective of the investee firms themselves (

Tian & Ye, 2018), thus reducing the incentives of investee firms concerning business innovation activities. While hurting the interests of the investee firms, this may also influence the firm’s labor income share. Additionally, CVC investment involvement encourages capital-biased technical advancement, which causes capital to continually replace labor and, eventually, reduces the labor income share (

Y. S. Gao et al., 2024). Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

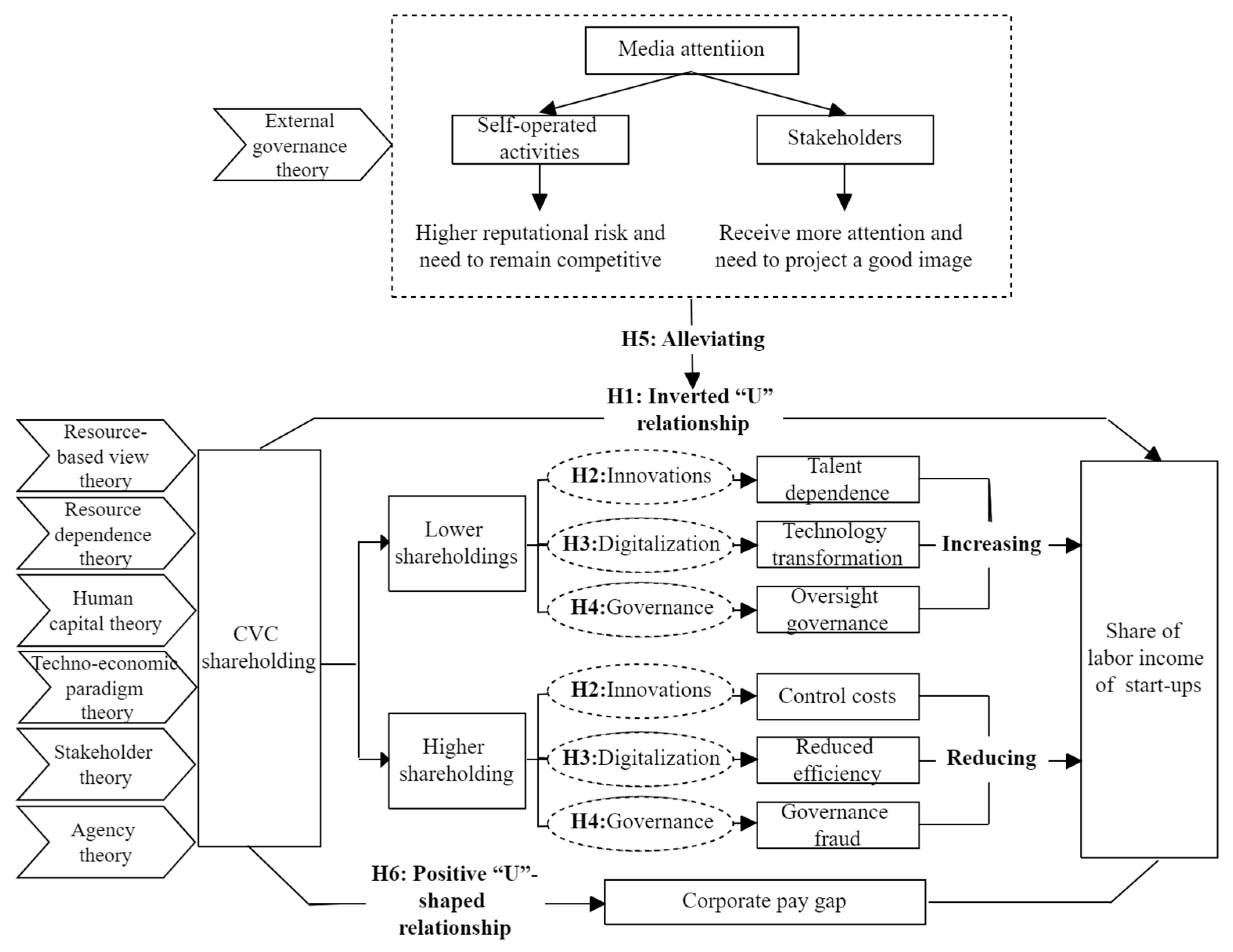

H1. The labor income share of investment firms and CVC holdings have a substantial inverted U-shaped relationship.

2.2.2. Examining How the Labor Income Share Is Impacted by CVC Shareholding

According to the human capital theory, the human capital of an enterprise, especially high-quality R&D personnel, is a key factor in creating value and increasing its share of labor income. CVC, as an important source of funding for enterprises, can help them attract and retain highly skilled personnel, especially R&D personnel, and thus enhance their human capital. CVC supports enterprises’ innovation through the provision of cutting-edge information on technological research and development, professional advice, and the dispatch of R&D personnel. personnel, etc., to support enterprise innovation and increase the demand for high-quality labor and salary expenses. However, when CVC ownership reaches a certain level, firms may tend to pursue short-term financial performance and shareholder returns, reducing investment in high-risk, long-cycle R&D projects in favor of investments that are stable and can achieve returns in the short term. This strategic shift prompts firms to tightly control their cost structure, including limiting the growth of R&D personnel compensation, which negatively affects the share of labor income.

CVC can provide investee enterprises with cutting-edge information on technologies and products and provide professional advice to investee enterprises, assist enterprises in developing and managing innovative projects, and dispatch R&D personnel to enterprises (

Braune et al., 2019). This process increases the demand for labor and expends more labor compensation. The process of transforming high-tech achievements promoted by CVC leads to a gradual increase in the demand for high-tech R&D personnel, leading to a sharp rise in high-tech labor costs. Compared with traditional fixed investment, enterprise innovation relies heavily on high-quality talent. With the increase in enterprise innovation ability, competition, demand, and reliance on high-quality labor will greatly increase (

Ye et al., 2022), which leads enterprises to take the initiative to increase monetary compensation to attract and retain high-quality labor. Furthermore, the dearth of highly skilled laborers will afford the company’s workforce greater bargaining power, leading to an increase in wages and, ultimately, an expansion of the labor income share.

It can be theorized that an increase in the percentage of employees engaged in research and development (R&D) roles at high remuneration levels may encourage a corresponding rise in the proportion of labor income. This might act as a proxy for how much emphasis a business places on innovation. However, it is important to note that this effect may be subject to variation when the CVC shareholding is high. Specifically, when the proportion of CVC ownership reaches a certain level, a firm’s business strategy may be tilted toward short-term financial performance and immediate shareholder returns (

Hill & Birkinshaw, 2006), and accordingly, it will reduce the resources tilted toward high-risk, long-cycle R&D projects and shift to a preference for investments that are highly stable and with short-term realizable returns. This strategic shift has prompted firms to tightly control their cost structure, which inevitably involves scaling back funding for R&D personnel. In the context of high CVC shareholding, firms may limit the growth of R&D personnel compensation in pursuit of short-term financial health. While an increase in the proportion of employees engaged in research and development (R&D) may be necessary to enhance the long-term core competitiveness of businesses, this could lead to an unintended consequence of a reduction in the proportion of labor income.

H2. CVC holdings have an inverted U-shaped effect on the labor income share by affecting the proportion of R&D personnel.

According to techno-economic paradigm theory, technological progress is the core driving force for enterprise change and economic growth. Technological innovation not only changes the production mode of enterprises, but also reshapes their organizational structure and competitive advantages, which in turn affects the pattern of income distribution. CVC accelerates this process of technological change by supporting the digital transformation of investee enterprises, which improves their productivity and innovation capacity, thus affecting the share of labor income. CVC plays a key role, which not only provides the necessary financial support, but also effectively reduces the risk of transformation and accelerates the application and marketization of digital technologies. However, when the shareholding of CVC is too high, it may lead to excessive centralization and rigidity in decision making, ignoring the actual needs of enterprises and market dynamics, and affecting the formulation and implementation of digital strategies. As a result, the relationship between CVC shareholding and the share of labor income of an enterprise may exhibit an inverted U-shaped characteristic, and this relationship is mediated by the level of digitization of the enterprise.

Unlike general venture capital, CVC focuses more on strategic orientation, industrial resource integration, business synergy, and long-term cooperation and thus can work more closely with investee firms. Although digital transformation has the potential to increase company revenues and productivity (

Hasan et al., 2018;

Sezer et al., 2021), numerous businesses are confronted with a lack of clarity regarding their transformation strategies, substantial technology R&D expenditures, and a dearth of skilled professionals. CVC not only provides the necessary financial support but also, more importantly, can effectively reduce transformation risks, and accelerate the application and marketization of digital technology. CVC investors use their strong information and capital advantages to help digital transformation enterprises overcome financial constraints, including providing financial support for infrastructure construction, such as digital equipment and platforms, supporting enterprises in adopting new technologies, and developing better business partners. At the same time, CVC investors can also play a supervisory role, encouraging enterprises to coordinate and integrate resources promptly and improve their risk-resistant ability to cope with the risks of long cycles and high uncertainty caused by digital transformation. Conversely, CVC investors pay attention to the effectiveness of the implementation of the enterprise’s digital transformation, including the scope, goals, and outcomes, and consider whether the transformation will lead to an increase in enterprise value (

Gurbaxani & Dunkle, 2019), whereas CVC investors expect enterprises to optimize their management teams, deploy leaders with digital thinking and technology backgrounds, and establish streamlined digital transformation teams to lead top-down digital transformation initiatives. The implementation of digital technology also facilitates enhancements to a company’s R&D capabilities and human capital structure, which subsequently enhances the efficiency of technological innovation and, ultimately, increases revenue through increased production efficiency. As digital technology continues to advance, the distribution of labor resources can be expected to decline further, accompanied by a reduction in production and operating costs. As a result of digitalization and intelligence, labor is likely to benefit from increased profits (

Sun, 2023), allowing businesses to increase their labor income share.

Firms backed by CVC investors can mimic the digital business model of the originating firm, take an outsourcing approach to digital transformation, etc. (

Furr & Shipilov, 2019) While this reduces the cost of transformation and the risk of failure, it also does not allow them to truly take ownership of the digital transformation, which may achieve only superficial digital mimicry rather than deep, endogenous digital transformation. As CVC investors increase their shareholding, employees and customers may become anxious and resistant. Excessive control may lead to overly centralized and rigid decision making, ignoring the actual needs of the enterprise and market dynamics and affecting the formulation and execution of a digital strategy that suits its development. CVC’s strategic orientation may lead the investee company to reduce its investment in digital transformation and instead invest its resources in projects that can generate economic benefits more quickly. In the long run, this could prevent companies from improving efficiency and innovation through digital transformation, affecting labor productivity and revenue share. Therefore, this paper proposes research Hypothesis H3:

H3. CVC holdings have an inverted U-shaped effect on the labor income share by affecting the level of digitization.

According to the resource dependence theory and stakeholder theory, the effectiveness of corporate governance is affected by a variety of factors. When CVC has a low shareholding, it, as an external investor, has an incentive to improve corporate governance and optimize the governance structure through supervision and resource investment. This helps firms attract and retain highly skilled employees and improve the quality of human capital, thereby increasing the labor income share. However, as CVCs’ shareholding increases, their strategic objectives may be more inclined to pursue short-term interests and market competitiveness, leading to excessive intervention in internal governance. This excessive intervention may cause corporate decisions to deviate from long-term development strategies and weaken the protection of employees’ interests, which in turn affects the labor income share. At the same time, CVCs’ resource investment and governance participation may gradually shift from promoting corporate development to protecting their own return on investment, reducing their investment in R&D and employee welfare.

CVC can effectively diversify investment risks by constructing a portfolio that contains multiple projects. This diversified investment strategy reduces the impact of the failure of a single project on the entire enterprise, reduces losses due to information asymmetry or forecasting errors at the macro level, and essentially reduces the information processing costs associated with decision making (

Ramaligegowda et al., 2021). By reducing information costs, CVC can identify and respond to potential problems more efficiently, which in turn leads to a more effective regulatory mechanism, improves firms’ tolerance for failures in R&D activities, and promotes firms’ innovation (

K. Gao et al., 2019). CVC investors are empowered to require that an investee company promptly address any misconduct and safeguard the rights and interests of its employees in instances where the actions of the managers in question are deemed to violate those rights and interests. Such action may include the rectification of harmed rights and interests, the provision of compensation, the enhancement of the working environment, or the modification of the management system. Moreover, CVC investors can monitor the implementation of corrective measures and require management to improve governance in the interest of companies’ long-term development. According to the capital–skill complementarity hypothesis, corporate governance improvements driven by CVC investors often require the support of many senior managers, and firms rely more on human capital and are willing to attract and hire highly skilled employees through greater compensation.

Despite the positive role of CVC investment in promoting corporate governance, however, there are potential negative effects on the other side of its shareholding. The purpose of CVC shareholding is not only to improve the governance environment of the firms in which it holds a stake but also, more importantly, to utilize its advantage in accessing information to seek benefits in the market. Therefore, from the perspective of governance fraud, as CVC shareholding increases, its supervision of investee firms may be weakened by the pursuit of self-interests, leading to a reduction in governance efficiency (

W. A. Li & Li, 2008). The short-sightedness of CVC investors may encourage or require investee firms to reduce their costs, which may lead to slow wage growth, cuts in benefits, or deterioration in working conditions (

Du & Ma, 2021), which directly affects the share of firms’ labor income. An increase in CVC shareholding, particularly within the principal–agent framework, provides it with greater influence, which in turn makes management more likely to prioritize short-term CVC interests over long-term development (

Falato et al., 2022), thereby further undermining the labor income share. Therefore, when the shareholding ratio is low, CVC shareholding plays the role of “monitoring governance”, whereas when the shareholding ratio exceeds a certain percentage, CVC shareholding has the effect of “governance fraud”. Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis H4.

H4. CVC holdings have an inverted U-shaped effect on the labor income share by affecting the extent of corporate governance.