Do Board Characteristics Affect Non-Performing Loans? GCC vs. Non-GCC Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

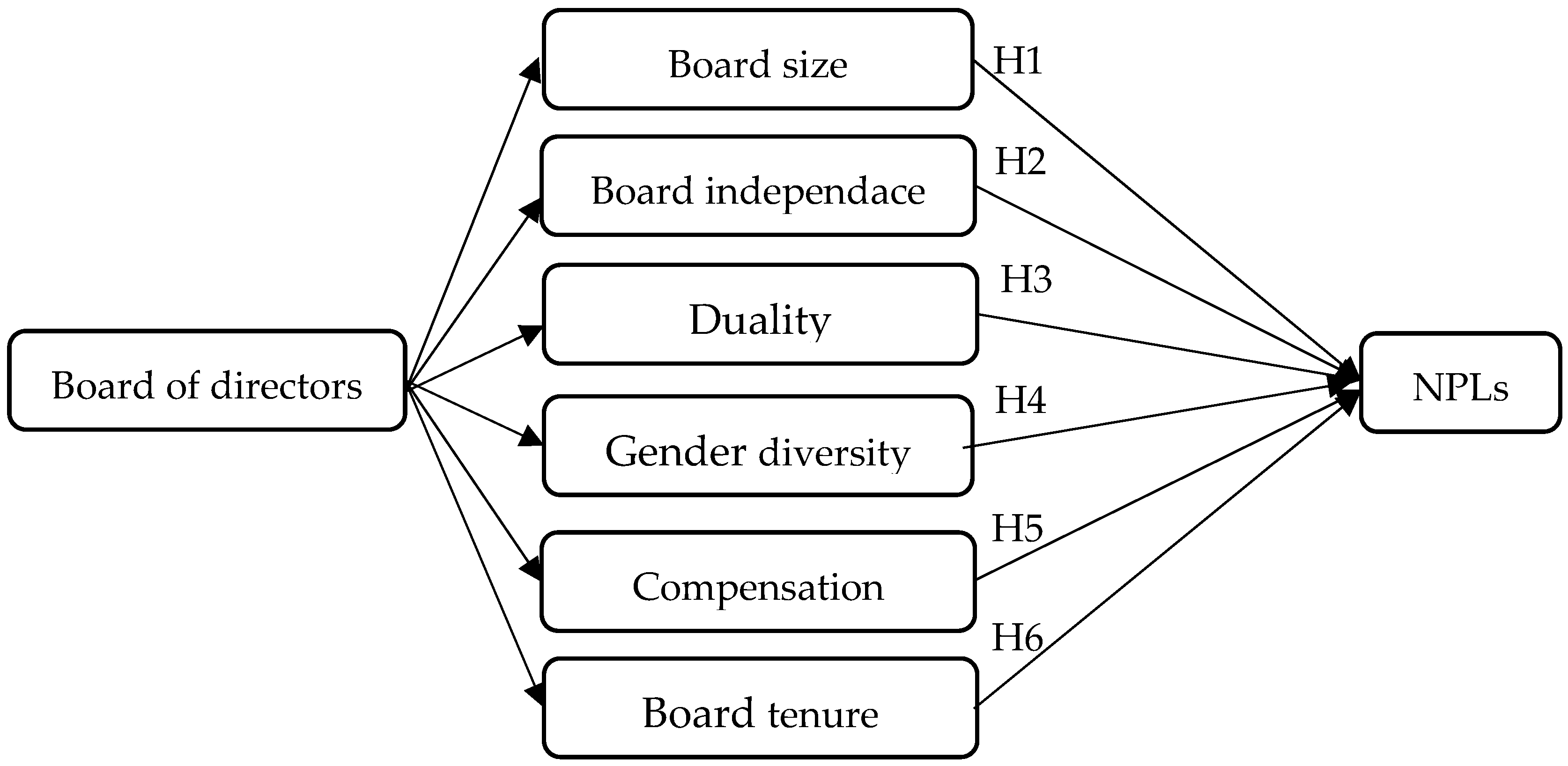

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Board Size and NPLs

2.2. Board Independence and NPLs

2.3. Duality and NPLs

2.4. Gender Diversity and NPLs

2.5. Board Tenure and NPLs

2.6. Board Compensation and NPLs

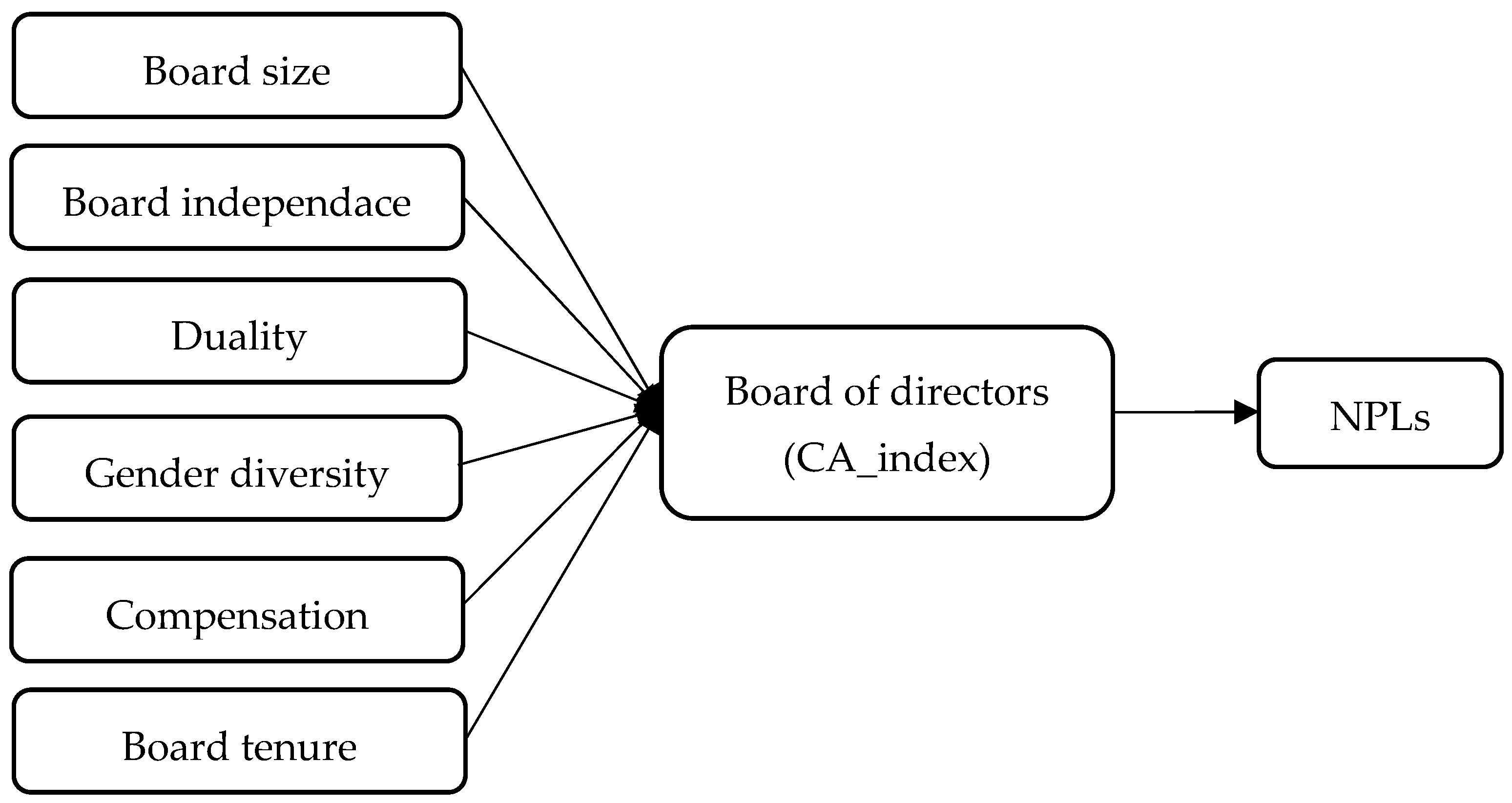

3. Methodology

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Empirical Approach, Model Specification and Variable Selection

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Summary Statistics and Correlation Matrix

4.2. Discussion of the Empirical Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abid, A., Gull, A. A., Hussain, N., & Nguyen, K. D. (2021). Risk governance and bank risk-taking behavior: Evidence from Asian banks. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money, 75, 101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R. B., & Funk, P. (2012). Beyond the glass ceiling: Does gender matter? Management Science, 58(2), 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusei, M., & Sarpong-Danquah, B. (2021). Institutional quality and the capital structure of microfinance institutions: The moderating role of board gender diversity. Journal of Institutional Economics, 17(4), 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, K. R., & Dittmar, A. K. (2012). The changing of the boards: The impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 137–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alandejani, M., & Asutay, M. (2017). Nonperforming loans in the GCC banking sectors: Does the Islamic finance matter? Research in International Business and Finance, 42, 832–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljughaiman, A. A., Almulhim, A. A., & Al Naim, A. S. (2024). Board structure, ceo equitybased compensation, and financial performance: Evidence from MENA countries. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnabulsi, K., Kozarevic, E., & Hakimi, A. (2022). Assessing the determinants of non-performing loans under financial crisis and health crisis: Evidence from the MENA banks. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10, 2124665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnabulsi, K., Kozarević, E., & Hakimi, A. (2023). Non-performing loans and net interest margin in the MENA region: Linear and non-linear analyses. International Journal of Financial Studies, 11(2), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saeed, A. (2023). Weak governance in mena region worsens deepening land crisis. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/01/18/weak-governance-in-mena-region-worsens-deepening-land-crisis (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Andres, P., & Vallelado, E. (2008). Corporate governance in banking: The role of the board of directors. Journal of Banking and Finance, 32, 2570–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A. B., Gharios, R., Abu Khalaf, B., & Seissian, L. A. (2024). Board characteristics and bank stock performance: Empirical Evidence from the MENA region. Risks, 12(5), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, U., Yu, Y., Hussain, M., Wang, X., & Ali, A. (2017). Do banking system transparency and competition affect nonperforming loans in the Chinese banking sector? Applied Economics Letters, 24(21), 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M. S. (1996). An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director composition and financial statement fraud. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 443–465. [Google Scholar]

- Bebchuk, L. A., & Spamann, H. (2010). Regulating Bankers’ Pay. Georgetown Law Journal, 98(2), 247–287. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T., & Levine, R. (2004). Stock markets, banks, and growth: Panel evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 28(3), 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltratti, A., & Stulz, R. M. (2009). Why did some banks perform better during the credit crisis? A cross-country study of the impact of governance and regulation. Charles a dice center working paper No. 2009–2012. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N., Kick, T., & Schaeck, K. (2014). Executive board composition and bank risk taking. Journal of Corporate Finance, 28, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaada, R., Ammari, A., & Ben Arfa, N. (2018). Board characteristics and MENA banks’ credit risk: A fuzzy-set analysis. Economics Bulletin, 38(4), 2284–2303. [Google Scholar]

- Boussaada, R., Hakimi, A., & Karmani, M. (2020). Is there a threshold effect in the liquidity risk–nonperforming loans relationship? A PSTR approach for MENA banks. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(2), 1886–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaada, R., Hakimi, A., & Karmani, M. (2025). Board cultural diversity and nonperforming loans: What role does boardroom gender diversity play? Managerial and Decision Economics, 46(2), 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, E., Hunter, W. C., & Jackson, W. E. (2004). Investment opportunity, product mix, and the relationship between bank CEO compensation and risk-taking. Working paper n°36. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, J., Cooperman, E. S., & Wolfe, G. A. (2010). Director tenure and the compensation of bank CEOs. Managerial Finance, 36(2), 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaibi, H., & Ftiti, Z. (2015). Credit risk determinants: Evidence from a cross-country study. Research in International Business and Finance, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. R., Steiner, T. L., & Whyte, A. M. (2006). Does stock option-based executive compensation induce risk-taking? An analysis of the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30, 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I. H., Harrison, H., & Jose, A. S. (2015). Yesterday’s heroes: Compensation and risk at financial firms. The Journal of Finance, 70, 839–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.-H., & Ardaaragchaa, N. (2024). Analysis of factors affecting the loan growth of banks with a focus on non-performing loans. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(5), 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, R., & Goldberg, L. S. (2021). Bank complexity, governance, and risk. Journal of Banking & Finance, 134, 106013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (1994). Corporate governance and the bankrupt firm: An empirical assessment. Strategic Management Journal, 15(8), 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danisman, G. O., & Tarazi, A. (2020). Financial inclusion and bank stability: Evidence from Europe. The European Journal of Finance, 26(18), 1842–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, R., & Torna, G. (2013). Nontraditional banking activities and bank failures during the financial crisis. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 22(3), 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebali, N., & Zaghdoudi, K. (2019). Corporate governance in banks and its impact on credit and liquidity risks: Case of Tunisian banks. Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting, 11(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B., & Ekşi, H. İ. (2020). The effect of board of directors characteristics on risk and bank performance: Evidence from Turkey. Economics and Business Review, 6(20), 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M., Marchica, M. T., & Mura, R. (2016). CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 39, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlenbrach, R., & Stulz, R. M. (2011). Bank CEO incentives and the credit crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 99, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C., Farinha, J., Martins, F. V., & Mateus, C. (2021). The impact of board characteristics and CEO power on banks’ risk-taking: Stable versus crisis periods. Journal of Bank Regulation, 22, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J. G., Olsson, I. A. S., & De Castro, A. C. V. (2017). Do aversive-based training methods actually compromise dog welfare? A literature review. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 196, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. (2017). Sector-specific analysis of non-performing loans in the US banking system and their macroeconomic impact. Journal of Economics and Business, 93, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, B. R., & Zajac, E. J. (2001). When will boards influence strategy? Inclination × power = strategic change. Strategic Management Journal, 22(12), 1087–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golliard, J. T., & Poder, L. (2007). Optimal capital structure of capital in the banking sector [Doctoral dissertation, University Paul Cézanne]. [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi, A., Boussaada, R., & Karmani, M. (2022). Is the relationship between corruption, government stability and non-performing loans non-linear? A threshold analysis for the MENA region. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(4), 4383–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, A., Boussaada, R., & Karmani, M. (2023). Financial inclusion and non-performing loans in MENA region: The moderating role of board characteristics. Applied Economics, 56(24), 2900–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, A., & Khemiri, M. A. (2024). Bank diversification and non-performing loans in the MENA region: The moderating role of financial inclusion. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. K., Khan, A., & Paltrinieri, A. (2018). Liquidity risk, credit risk and stability in islamic and conventional banks. Research in International Business and Finance, 48, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., & Hilary, G. (2018). Zombie board: Board tenure and firm performance. Journal of Accounting Research, 56(4), 1285–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A. I., Jebabli, I., Thrikawala, S. S., Alawi, S. M., & Mehmood, R. (2024). How do corporate governance and corporate social responsibility affect credit risk? International Business and Finance, 67(PA), 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbouri, I., Naili, M., Almustafa, H., & Jabbouri, R. (2022). Does ownership concentration affect banks’ credit risk? Evidence from MENA emerging markets. Bulletin of Economic Research, 75(1), 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H., Alshareef, E., & Mohamad, A. (2021). The impact of corruption on commercial banks’ credit risk: Evidence from a panel quantile regression. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 28(2), 1364–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C. M. (1993). The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. In American finance association. The Journal of Finance, 48(3), 831–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L., Kanagaretnam, K., & Lobo, G. J. (2011). Ability of accounting and audit quality variables to predict bank failure during the financial crisis. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(11), 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K., De Masi, S., & Paci, A. (2016). Corporate governance in banks. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(3), 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadima, M., & Louri, H. (2020). Non-performing loans in the euro area: Does bank market power matter? International Review of Financial Analysis, 72, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karismaulia, A., Ratnawati, K., & Wijayanti, R. (2023). The effect of macroeconomic and bank-specific variables on non-performing loans with bank size as a moderating variable. The International Journal of Social Sciences World, 5(1), 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervin, J. B. (1992). Methods for business research. Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Kinateder, H., Choudhury, T., Zaman, R., Scagnelli, S. D., & Sohel, N. (2021). Does boardroom gender diversity decrease credit risk in the financial sector? Worldwide evidence. Journal of International Financial Markets Institutions and Money, 73, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, V. W., Konrad, A. M., & Erkut, S. (2006). Critical mass on corporate boards: Why three or more women enhance governance. Report No. WCW 11. Wellesley Center for Women. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. R., Stauvermann, J. P., Patel, A., & Prasad, S. S. (2018). Determinants of non-performing loans in small developing economies: A case of Fiji’s banking sector. Accounting Research Journal, 31(2), 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2009). Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(2), 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., & Boateng, A. (2018). Board composition, monitoring and credit risk: Evidence from the UK banking industry. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 51, 1107–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., & Whidbee, D. A. (2016). US bank failure and bailout during the financial crisis: Examining the determinants of regulatory intervention decisions. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 8(3), 316–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lückerath-Rovers, M. (2013). Women on boards and firm performance. Journal of Management & Governance, 17(2), 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi, M. L. G. (2016). Effectiveness of best practices in corporate governance in combating corruption. Revista Científica Hermes, 15, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mehmood, R., Ahmad, I., Rahman, S. U., & Sattar, S. (2025). The role of corporate governance in bank risk-taking. In Advances in human resources management and organizational development book series (pp. 215–226). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsni, S., Otchere, I., & Shahriar, S. (2021). Board gender diversity, firm performance and risk-taking in developing countries: The moderating effect of culture. Journal of International Financial Markets Institutions and Money, 73, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchemwa, R., Padia, N., & Callaghan, C. W. (2016). Board composition, board size and financial performance of Johannesburg stock exchange companies. SAJEMS, 19(4), 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naili, M., & Lahrichi, Y. (2020). The determinants of banks’ credit risk: Review of the literature and future research agenda. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(1), 334–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamvilaikorn, K., Lhaopadchan, S., & Treepongkaruna, S. (2024). Corporate governance, social responsibility and sustainability commitments by banks: Impacts on credit risk and performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(6), 5109–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, F. O., & Adewumi, A. A. (2020). Corporate governance and the earnings quality of Nigerian firms. International Journal of Financial Research, 11(5), 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. (2012). Corruption, soundness of the banking sector, and economic growth: A cross-country study. Journal of International Money and Finance, 31, 907–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, S. (2009). Strong boards, CEO power and bank risk-taking. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploix, H. (2003). Bâle II et le capital-investissement. Revue d’Économie Financière, 73(4), 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, A. (2018). Macroeconomic determinants of non-performing loans: Case of Turkey and Saudi Arabia. Journal Of Business Research Turk, 10(3), 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C., Rahman, N., & Rubow, E. (2011). Diversity in the composition of board of directors and environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR). Business & Society, 50(1), 189–223. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, C. (2017). The relationship between corporate governance characteristics and credit risk exposure in banks: Implications for financial regulation. European Journal of Law and Economics, 43, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, V., & Saurina, J. (2003). Deregulation, market power and risk behaviour in Spanish banks. European Economic Review, 47, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, C., Farmanesh, P., & Athari, A. S. (2023). Does country risk impact the banking sectors’ non-performing loans? Evidence from BRICS emerging economies. Financial Innovation, 9(1), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallemi, M., Hamad, S. B., & Ellili, N. O. D. (2023). Impact of board of directors on insolvency risk: Which role of the corruption control? Evidence from OECD banks. Review of Managerial Science, 17(8), 2831–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, R., & Khoirotunnisa, F. (2020). The impact of board gender diversity on bank credit risk. The International Journal of Business Review, 3(2), 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W. G., & Gleason, A. E. (1999). Board structure, ownership, and financial distress in banking firms. Journal of Financial Services Research, 16(3), 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srairi, S. (2024). The impact of corporate governance on bank risk-taking: Evidence of islamic banks in gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. International Journal of Islamic Finance and Sustainable Development, 16(3), 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srairi, S., Bourkhis, K., & Houcine, A. (2021). Does bank governance affect risk and efficiency? Evidence from Islamic banks in GCC countries. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 15(3), 644–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, S., & Webb, E. (2005). Does corporate governance determine bank loan portfolio choice? Journal of Academy of Business and Economics, 5(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Switzer, L. N., & Wang, J. (2013). Default risk estimation, bank credit risk, and corporate governance. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments, 22(2), 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchouna, A., Jarraya, B., & Bouri, A. (2021). Do board characteristics and ownership structure matter for bank non-performing loans? Empirical evidence from US commercial banks. Journal of Management and Governance, 26(2), 479–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongurai, J., & Vithessonthi, C. (2018). The impact of the banking sector on economic structure and growth. International Review of Financial Analysis, 56, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeas, N. (2003). Length of board tenure and outside director independence. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 30(7–8), 1043–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbach, M. S. (1988). Outside directors and CEO turnover. Journal of Financial Economics, 20(1–2), 431–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Countries. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCC Countries | Non-GCC Countries | ||||

| Countries | N | % | Countries | N | % |

| 10 2 11 7 7 5 | 14.28% 2.86% 15.71% 10% 10% 7.14% |

| 3 4 1 2 10 8 | 4.28% 5.71% 1.43% 2.86 14.28% 11.43% |

| Total | 42 | 60% | Total | 28 | 40% |

| Variables | Definitions | Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||

| NPLs | Non-performing loans | Non-performing loans to total loans ratio (%). |

| Board characteristics | ||

| BS | Board size | Total number of directors within a Board of Directors |

| IND | Independent directors | Proportion of independent directors on a Board of Directors |

| DUAL | Duality | Binary variable takes 1 if the CEO is the Chairman of the Board, and 0 otherwise. |

| BGD | Gender diversity | Women on the board as a percentage of the total number of directors. |

| MAND | Board tenure | The term length of a board of directors. |

| COMP | Compensation | Total compensation of directors in US dollars relative to total assets (%). |

| CA_index | Board characteristics index | Composite index of board characteristics with values ranging from 0 to 1. For more details on the construction of this index, see the explanation on page 9. |

| Control variables | ||

| SIZE | Bank size | The natural logarithm of the total assets of each bank |

| CAP | Capital | Equity to total assets (%). |

| LTD | Liquidity risk | Loan-to-deposit ratio, (%). |

| ROA | Bank performance | Return on assets (ROA), (%) |

| NII | Bank diversification | Non-interest income as a percentage of total assets. |

| CONC | Concentration | The share of the five biggest banks’ assets to all banks’ assets (%). |

| GDP | Economic growth | Annual GDP growth rate, (%) |

| INF | Inflation rate | Annual growth of Consumer index price, (%) |

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPLs | 7.3 | 1.8 | 4.01 | 261 |

| BS | 10.52 | 1.95 | 5.02 | 19 |

| IND | 28.81 | 23.48 | 13.1 | 100 |

| BGD | 6.62 | 8.41 | 1.4 | 40 |

| MAND | 3.10 | 0.59 | 1 | 6 |

| COMP | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.18 |

| SIZE | 23.74 | 1.22 | 20.94 | 26.51 |

| CAP | 16.7 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 42.9 |

| ROA | 1.4 | 0.8 | −3.8 | 6.3 |

| LTD | 98.76 | 5.84 | 1.4 | 162 |

| NII | 38.44 | 17.26 | 9.55 | 96 |

| CONC | 82.20 | 13.36 | 56.04 | 100 |

| GDP | 3.12 | 4.07 | −2.4 | 19.59 |

| INF | 4.83 | 10.96 | −3.75 | 29.5 |

| DUAL | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 599 | 87.79% |

| 1 | 83 | 12.21% |

| Total | 682 | 100% |

| NPLs | BS | IND | DUAL | BGD | MAND | COMP | SIZE | CAP | ROA | LTD | NII | CONC | GDP | INF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPLs | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||||

| BS | 0.2801 * | 1.0000 | |||||||||||||

| (0.0000) | |||||||||||||||

| IND | −0.1264 * | −0.0729 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||

| (0.0023) | (0.0790) | ||||||||||||||

| DUAL | 0.0562 | 0.1680 * | −0.0999 * | 1.0000 | |||||||||||

| (0.1765) | (0.0000) | (0.0147) | |||||||||||||

| BGD | 0.2524 * | 0.2375 * | −0.1397 * | −0.0833 * | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0007) | (0.0428) | ||||||||||||

| MAND | −0.0235 | 0.0537 | −0.1279 * | 0.3443 * | −0.0853 * | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| (0.5765) | (0.2014) | (0.0020) | (0.0000) | (0.0407) | |||||||||||

| COMP | 0.1480 * | −0.0474 | −0.2020 * | 0.1559 * | 0.3829 * | −0.0748 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| (0.0111) | (0.4169) | (0.0005) | (0.0072) | (0.0000) | (0.2066) | ||||||||||

| SIZE | −0.1867 * | −0.0606 | 0.0904 * | 0.1377 * | −0.3643 * | 0.0912 * | −0.5102 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| (0.0000) | (0.1662) | (0.0376) | (0.0015) | (0.0000) | (0.0380) | (0.0000) | |||||||||

| CAP | −0.1057 * | −0.0414 | 0.1254* | 0.0712 | −0.1474 * | 0.2518 * | −0.3640 * | 0.1943 * | 1.0000 | ||||||

| (0.0023) | (0.3213) | (0.0024) | (0.0843) | (0.0004) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000 | ||||||||

| ROA | −0.1725 * | −0.0358 | −0.0224 | −0.0530 | 0.0695 | −0.0307 | 0.1635 * | 0.1648 *) | 0.0823 * | 1.0000 | |||||

| (0.0000) | (0.3876) | (0.5854) | (0.1956) | (0.0910) | (0.4591) | (0.0048) | (0.0000 | (0.0149) | |||||||

| LTD | −0.0520 | 0.0380 | −0.0515 | −0.0430 | 0.1046 * | −0.0191 | −0.0184 | −0.0411 | 0.0197 | 0.0950 * | 1.0000 | ||||

| (0.1298) | (0.3617) | (0.2136) | (0.2980) | (0.0116) | (0.6478) | (0.7524) | (0.2804) | (0.5680) | (0.0050) | ||||||

| NII | −0.0016 | 0.0723 | −0.0744 | 0.0164 | −0.1013 * | 0.3225 * | −0.1536 * | 0.3106 * | 0.1425 * | −0.0791 * | 0.0853 * | 1.0000 | |||

| (0.9643) | (0.0814) | (0.0699) | (0.6902) | (0.0138) | (0.0000) | (0.0083) | (0.0000) | (0.0001) | (0.0256) | (0.0176) | |||||

| CONC | −0.2255 * | −0.3393 * | 0.2763 * | −0.1467 * | −0.4319 * | 0.0805 | −0.5140 * | 0.2194 * | 0.2336 * | −0.0099 | −0.1181 * | −0.0298 | 1.0000 | ||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0004) | (0.0000) | (0.0538) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.7689) | (0.0006) | (0.4088) | ||||

| GDP | −0.0666 | 0.1410 * | −0.0188 | 0.0578 | 0.0442 | 0.0737 | - 0.0813 | 0.0757 * | 0.0386 | 0.3077 * | 0.0578 | 0.1127 * | −0.0360 | 1.0000 | |

| (0.0521) | (0.0006) | (0.6469) | (0.1586) | (0.2834) | (0.0758) | (0.1632) | (0.0462) | (0.2547) | (0.0000) | (0.0885) | (0.0014) | (0.2879) | |||

| INF | 0.0638 | 0.1093 * | 0.0283 | 0.0279 | 0.1209 * | −0.2337 * | 0.3666 * | 0.0022 | −0.0548 | 0.1216 | 0.0732 * | −0.0661 | −0.2669 * | 0.0281 | 1.0000 |

| (0.0625) | (0.0082) | (0.4898) | (0.4954) | (0.0032) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.9533) | (0.1054) | (0.0002) | (0.0309) | (0.0622) | (0.0000) | (0.3981) |

| (M1) BS and NPLs | (M2) IND and NPLs | (M3) DUAL and NPLs | (M4) BGD and NPLs | (M5) MAND and NPLs | (M6) COMP and NPLs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | |

| NPLs (−1) | 0.134 | 365.73 *** | 0.157 | 299.01 *** | 0.159 | 412.39 *** | 0.154 | 452.94 *** | 0.157 | 455.77 *** | 0.151 | 5.38 *** |

| SIZE | −0.055 | −19.72 *** | −0.047 | −25.26 *** | −0.049 | −24.43 *** | −0.052 | −45.92 *** | −0.049 | −42.24 *** | −0.029 | −14.31 *** |

| CAP | −0.014 | −3.43 *** | −0.016 | −4.33 *** | −0.014 | −4.16 *** | −0.015 | −2.90 *** | −0.016 | −5.60 *** | −0.106 | −10.04 *** |

| ROA | −0.412 | −5.77 *** | −0.612 | −10.12 *** | −0.569 | 12.55 *** | −0.647 | −10.22 *** | −0.849 | −13.17 *** | −0.319 | −7.17 *** |

| LTD | −0.0002 | −0.30 | 0.001 | 0.39 | −0.000 | −0.35 | −0.000 | −0.37 | −0.001 | −0.62 | −0.003 | −2.48 ** |

| NII | −0.003 | −60.85 *** | −0.002 | −42.31 *** | −0.002 | −34.85 *** | −0.002 | −53.72 *** | −0.002 | −74.34 *** | −0.001 | −6.15 *** |

| CONC | 0.003 | 30.01 *** | 0.001 | 34.61 *** | 0.002 | 33.14 *** | 0.002 | 49.53 *** | 0.001 | 26.01 *** | 0.002 | 16.63 *** |

| GDP | −0.002 | −29.95 *** | −0.001 | −28.82 *** | −0.001 | −26.11 *** | −0.001 | −31.49 *** | −0.002 | −39.41 *** | −0.001 | −20.39 *** |

| INF | −0.0004 | −9.68 *** | −0.0003 | −8.16 *** | −0.000 | −9.96 *** | −0.000 | −9.59 *** | −0.000 | −3.66 *** | 0.003 | 16.36 *** |

| BS | 0.019 | 78.11 *** | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| IND | - | −0.0003 | −13.38 *** | - | - | - | - | |||||

| DUAL | - | - | 0.006 | 1.87 * | - | - | - | |||||

| BGD | - | - | - | −0.002 | −35.54 *** | - | - | |||||

| MAND | - | - | - | - | 0.082 | 255.71 *** | - | |||||

| COMP | - | - | - | - | - | −4.819 | −0.72 | |||||

| _cons | 1.035 | 14.59 *** | 1.140 | 24.30 *** | 1.190 | 22.79 *** | 1.221 | 42.77 *** | 0.971 | 29.56 *** | 0.617 | 14.32 *** |

| AR(1) | −1.21 | −1.1286 | −1.124 | −1.1217 | −1.1271 | −2.033 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.2263 | 0.2591 | 0.2610 | 0.2620 | 0.2597 | 0.0421 | ||||||

| AR(2) | −1.4448 | −1.3284 | −1.2352 | −1.6401 | −1.1391 | −0.09712 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.1485 | 0.1840 | 0.2168 | 0.1010 | 0.2546 | 0.9226 | ||||||

| Sargan test | 62.498 | 59.559 | 59.780 | 61.835 | 66.302 | 42.885 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.8671 | 0.9176 | 0.9143 | 0.8798 | 0.7788 | 0.9992 | ||||||

| N | 682 | 682 | 682 | 682 | 682 | 682 | ||||||

| (M1) BS and NPLs | (M2) IND and NPLs | (M3) DUAL and NPLs | (M4) BGD and NPLs | (M5) MAND and NPLs | (M6) COMP and NPLs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | |

| NPLs (−1) | 0.130 | 7.95 *** | 0.146 | 340.69 *** | 0.150 | 797.51 *** | 0.149 | 682.04 *** | 0.158 | 18.97 *** | .248 | 9.91 *** |

| SIZE | −0.013 | −13.66 *** | −0.008 | −4.70 *** | −0.010 | −10.09 *** | −0.010 | −6.68 *** | −0.008 | −6.19 *** | −0.005 | −2.66 *** |

| CAP | −0.114 | −3.21 *** | −0.158 | −5.17 *** | −0.124 | −5.39 *** | −0.157 | −6.81 *** | −0.142 | −8.71 *** | 0.049 | 2.24 ** |

| ROA | 0.138 | 0.61 | 0.231 | 2.03 ** | 0.019 | 0.25 | 0.095 | 1.03 | −0.311 | −4.45 *** | 0.160 | 3.13 *** |

| LTD | −0.00007 | (0.07) | −0.0004 | 0.31 | −0.001 | −0.43 | −0.001 | −0.79 | −0.001 | −0.82 | 2.37 | 0.03 |

| NII | −0.002 | −43.14 *** | −0.002 | −29.65 *** | −0.002 | −71.64 *** | −0.002 | −33.32 *** | −0.002 | −65.17 *** | −0.00006 | −1.58 |

| CONC | 0.005 | 23.99 *** | 0.003 | 20.92 *** | 0.003 | 22.86 *** | 0.003 | 32.54 *** | 0.003 | 34.78 *** | −0.0003 | −2.89 *** |

| GDP | −0.002 | −31.02 *** | −0.002 | −29.40 *** | −0.002 | −32.48 *** | −0.002 | −26.91 *** | −0.002 | −54.82 *** | −0.0005 | −6.52 *** |

| INF | −0.001 | −6.10 *** | −0.001 | −9.60 *** | −0.001 | −17.17 *** | −0.001 | −12.21 *** | −0.0004 | −12.16 *** | −0.0003 | −16.04 *** |

| BS | 0.020 | 69.00 *** | -- | - | - | - | - | |||||

| IND | - | −0.0003 | −11.86 *** | - | - | - | - | |||||

| DUAL | - | - | 0.016 | 2.19 ** | - | - | - | |||||

| BGD | - | -- | - | −0.0001 | −2.99 *** | - | - | |||||

| MAND | - | - | - | -- | 0.087 | 173.37 *** | - | |||||

| COMP | - | - | - | - | -- | −16.867 | −2.50 ** | |||||

| _cons | −0.128 | −4.01 *** | 0.093 | 1.94 * | 0.125 | 4.22 *** | 0.111 | 2.99 *** | −0.171 | −4.72 | 0.191 | 3.34 *** |

| AR(1) | −1.1294 | −1.0873 | 1.0893 | −1.0897 | −1.1601 | −2.18 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.2587 | 0.2769 | 0.2760 | 0.2759 | 0.2460 | 0.0293 | ||||||

| AR(2) | −1.2813 | −1.4329 | −1.2058 | −1.281 | −1.106 | −1.2647 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.2001 | 0.1519 | 0.2279 | 0.2002 | 0.2687 | 0.2060 | ||||||

| Sargan test | 46.192 | 44.385 | 46.099 | 49.552 | 49.875 | 31.191 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.9973 | 0.9986 | 0.9974 | 0.9919 | 0.9911 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| N | 436 | 436 | 436 | 436 | 436 | 436 | ||||||

| (M1) BS and NPLs | (M2) IND and NPLs | (M3) DUAL and NPLs | (M4) BGD and NPLs | (M5) MAND and NPLs | (M6) COMP and NPLs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | |

| NPLs (−1) | 0.130 | 1.90 * | 0.171 | 5.28 *** | 0.186 | 4.34 *** | 0.120 | 2.56 ** | 0.160 | 3.69 *** | 0.110 | 50.47 *** |

| SIZE | −0.029 | −1.68 * | −0.024 | −6.10 *** | −0.018 | −1.97 ** | −0.035 | −3.92 *** | −0.014 | −2.99 *** | −0.022 | −1.93 * |

| CAP | −0.005 | −0.87 | −0.013 | −1.40 | −0.006 | −0.59 | −0.020 | −1.65 * | −0.004 | −3.26 *** | −0.002 | −0.36 |

| ROA | 0.004 | 0.01 | −0.801 | −0.97 | −1.004 | −1.67 * | −0.255 | −0.59 | −1.649 | −2.32 ** | 0.474 | 0.54 |

| LTD | 0.001 | 0.26 | −0.001 | 0.32 | 0.0008 | 0.00 | −0.0004 | −0.25 | −0.001 | −0.33 | 0.00006 | 0.26 |

| NII | −0.005 | −16.15 *** | −0.003 | −8.69 *** | −0.002 | −5.36 *** | −0.003 | −5.02 *** | −0.004 | −7.87 *** | −0.003 | −5.36 *** |

| CONC | 0.004 | 6.01 *** | 0.003 | 3.74 *** | 0.002 | 4.95 *** | 0.003 | 4.92 *** | 0.002 | 5.31 *** | 0.004 | 5.65 *** |

| GDP | −0.003 | −5.63 *** | −0.003 | −7.93 *** | −0.003 | −8.30 *** | −0.003 | −11.96 *** | −0.003 | −7.96 *** | −0.003 | −9.92 *** |

| INF | −0.001 | −1.85 * | −0.0003 | −0.98 | 0. 00009 | 0.28 | −0.001 | −1.82 * | 0.0002 | 0.93 | −0.001 | −2.64 *** |

| BS | 0.026 | 12.80 *** | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| IND | - | −0.0004 | −2.27 ** | - | - | - | - | |||||

| DUAL | - | - | 0.005 | 0.69 | - | - | - | |||||

| BGD | - | - | - | −0.003 | −16.93 *** | - | - | |||||

| MAND | - | - | - | - | 0.064 | 44.72 *** | - | |||||

| COMP | - | - | - | - | - | −17.897 | −1.71 * | |||||

| _cons | 0.364 | 0.87 | 0.593 | 5.08 *** | 0.434 | 2.00 ** | 0.817 | 3.74 *** | 0.215 | 1.83 | 0.473 | 1.64 |

| AR(1) | −1.2841 | −1.1358 | −1.2184 | −1.0025 | −1.5868 | −1.0848 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.1991 | 0.2561 | 0.2231 | 0.3161 | 0.1126 | 0.2780 | ||||||

| AR(2) | −0.94766 | −0.94337 | −1.3721 | −1.2485 | −0.98756 | −0.79825 | ||||||

| Prob | 0.3433 | 0.3455 | 0.1700 | 0.2118 | 0.3234 | 0.4247 | ||||||

| Sargan test | 18.290 | 21.813 | 13.879 | 21.457 | 16.603 | 16.929 | ||||||

| Prob | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| N | 292 | 292 | 292 | 292 | 292 | 292 | ||||||

| MENA | GCC | Non-GCC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | Coef. | Z | |

| NPLs (−1) | 0.156 | 313.48 *** | 0.151 | 11.28 *** | 0.104 | 2.28 ** |

| SIZE | −0.064 | −47.50 *** | −0.028 | −15.77 *** | −0.029 | −3.03 *** |

| CAP | −0.017 | −8.75 *** | −0.198 | −12.12 *** | −0.017 | −1.76 * |

| ROA | −0.787 | −12.53 *** | −0.074 | −1.75 * | −0.781 | −2.26 ** |

| LTD | −0.002 | 1.82 | −0.001 | −0.68 | −0.00001 | −0.01 |

| NII | −0.002 | −67.39 *** | −0.001 | −27.27 *** | −0.003 | −5.84 *** |

| CONC | 0.002 | 43.96 ** | 0.003 | 32.00 *** | 0.002 | 4.37 *** |

| GDP | −0.001 | −39.08 *** | −0.001 | −16.56 *** | −0.003 | −4.49 *** |

| INF | −0.000 | −5.09 *** | −0.001 | −16.82 *** | −0.000 | −2.07 ** |

| CA_index | −0.136 | −19.67 *** | −0.094 | −8.20 *** | −0.130 | −3.82 *** |

| _cons | 1.476 | 40.63 *** | 0.495 | 10.21 *** | 0.709 | 3.21 *** |

| AR(1) | −1.1312 | −1.1043 | −1.9127 | |||

| Prob | 0.2580 | 0.2694 | 0.0558 | |||

| AR(2) | −1.6633 | −1.3959 | −1.3593 | |||

| Prob | 0.0962 | 0.1627 | 0.1741 | |||

| Sargan test | 63.481 | 47.206 | 17.022 | |||

| Prob | 0.8467 | 0.9961 | 1.0000 | |||

| N | 682 | 436 | 292 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hakimi, A.; Saidi, H.; Saidi, S. Do Board Characteristics Affect Non-Performing Loans? GCC vs. Non-GCC Insights. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020101

Hakimi A, Saidi H, Saidi S. Do Board Characteristics Affect Non-Performing Loans? GCC vs. Non-GCC Insights. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(2):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020101

Chicago/Turabian StyleHakimi, Abdelaziz, Hichem Saidi, and Soumaya Saidi. 2025. "Do Board Characteristics Affect Non-Performing Loans? GCC vs. Non-GCC Insights" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 2: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020101

APA StyleHakimi, A., Saidi, H., & Saidi, S. (2025). Do Board Characteristics Affect Non-Performing Loans? GCC vs. Non-GCC Insights. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(2), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020101