1. Introduction

The United Nations has set forth seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for all nations to attain by 2030 (

UN 2022). Impact investing is garnering the utmost significance for effectively implementing the SDGs, as the fiscal deficit in reaching the goals has soared to USD 4.2 trillion in developing economies (

Convergence 2022). The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 a worldwide health pandemic on 11 March 2020 (

Gurcan et al. 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic has further deteriorated global financial, economic, and health problems, making achieving sustainability arduous (

Li et al. 2023;

Hepburn et al. 2020). The infusion of capital through impact investments, catalytic aid, and other innovative tools assists in overcoming the health crises and contributes towards achieving sustainability (

OECD 2018,

2020).

Impact investing via blended finance has emerged as an indispensable vehicle for bridging the rapidly expanding SDG funding gap. Blended finance is a structuring approach that mobilises private investment and public and philanthropic capital to achieve SDGs through financial leverage (

Convergence 2022;

Pereira 2017;

Chirambo 2021). The novelty of the blended finance concept lies in streamlining the group of heterogenous investors and innovative tools for a standard set of financial and development goals in line with the norms of SDGs (

IDFC 2019).

In the development of innovative approaches that deform the existing unsustainable practices and bridge the gap between sustainability and business models (

Farza et al. 2021), a partial risk guarantee (PRG) is one of the critical, innovative instruments in the blended finance approach that provides partial assurance to the risk investor to lend leveraged capital to the borrower (

World Bank 2008). Risk guarantees provide technical and infrastructural assistance to the borrower aiming to upscale the population struggling with poverty, hunger, illiteracy, and sanitation issues. Under the PRG scheme, philanthropic capital is employed as a risk guarantee to create financial and economic additionality through the multiplier effect. Through the accessibility of financial capital, PRG assists the vulnerable sections of society in overcoming atrocities of poverty and unemployment. PRG improves the cash flow situation of the borrower by meeting operating expenses through the disbursement of working capital loans. Overall, the borrower’s quality and adoption of innovative practices are enhanced through additional capital and subsidised costs.

Mobilisation of private investment is needed to meet the rising demand for a skilled workforce and financial capital that has escalated post COVID-19. As a result, we must look at creative ways to combine public and private funding for growth. The employment of a blended finance approach would assist philanthropic, private, and public investors in creating a pool of resources for upscaling the borrowers and optimising the number of beneficiaries. To meet this rising demand and contribute towards a sustainable environment, the financial leveraging of capital through blended finance that multiplies the access of funds and improvises the infrastructural facilities is essential (

Solanki et al. 2021). Companies nowadays are exploring emerging ways of utilising their CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) funds, such as blended finance, for sustainable and equitable growth of an economy. CSR integrates the environmental and social concerns of the companies, along with managing business operations and stakeholders’ interests (

UNIDO 2007). From a global perspective, an innovative economy has the potential to attain sustainable development and contribute towards a resilient ecosystem (

Bhaskaran 2023).

The lack of literature and awareness motivates the present study to highlight the significance and core research trends in the domain of blended finance for its effective implementation. The analysis of research articles provides a brief overview of the countries, authors, themes, keywords, organisations, and sources used in the literature on blended finance. The analysis shows that countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States are making strides in this domain, as they are leaders in the number of publications. Authors such as Emma Mawdsley, Lightfoot, and Szent-Iványi have the highest citations and are highly influential in this domain. They are affiliated with the top influential university, i.e., the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. The journals leading with the maximum number of publications are Dialogues in Human Geography, Agriculture and Human Values, and Ecosystem Services. Many developing or underdeveloped countries, such as India, Ghana, Brazil, etc., have started appearing on the list.

This study’s presented results pave the way for policymakers, academicians, and the government to locate the need for a combined financial approach and appropriate instruments to integrate private, public, and philanthropic capital.

This paper establishes the need and advantages of blended finance and partial risk guarantees. For this purpose, the article is organised into five sections.

Section 2 contains the materials and methods used to conduct the bibliometric analysis of partial risk guarantees and blended finance.

Section 3 provides the results and analysis of the bibliometric analysis to present a holistic picture to the reader of the current situation of blended finance and partial risk guarantee literature.

Section 4 offers discussion based on the literature analysis conducted in

Section 2 and

Section 3.

Section 5 concludes the whole study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database and Data Collection

This study aims to focus on the articles published on blended finance and partial risk guarantees using the Scopus© database. We primarily focus on the Scopus database, which has more detailed coverage of smaller research domains. Scopus has 20% more management and social sciences range than other databases, such as Web of Science (

Martín-Martín et al. 2018;

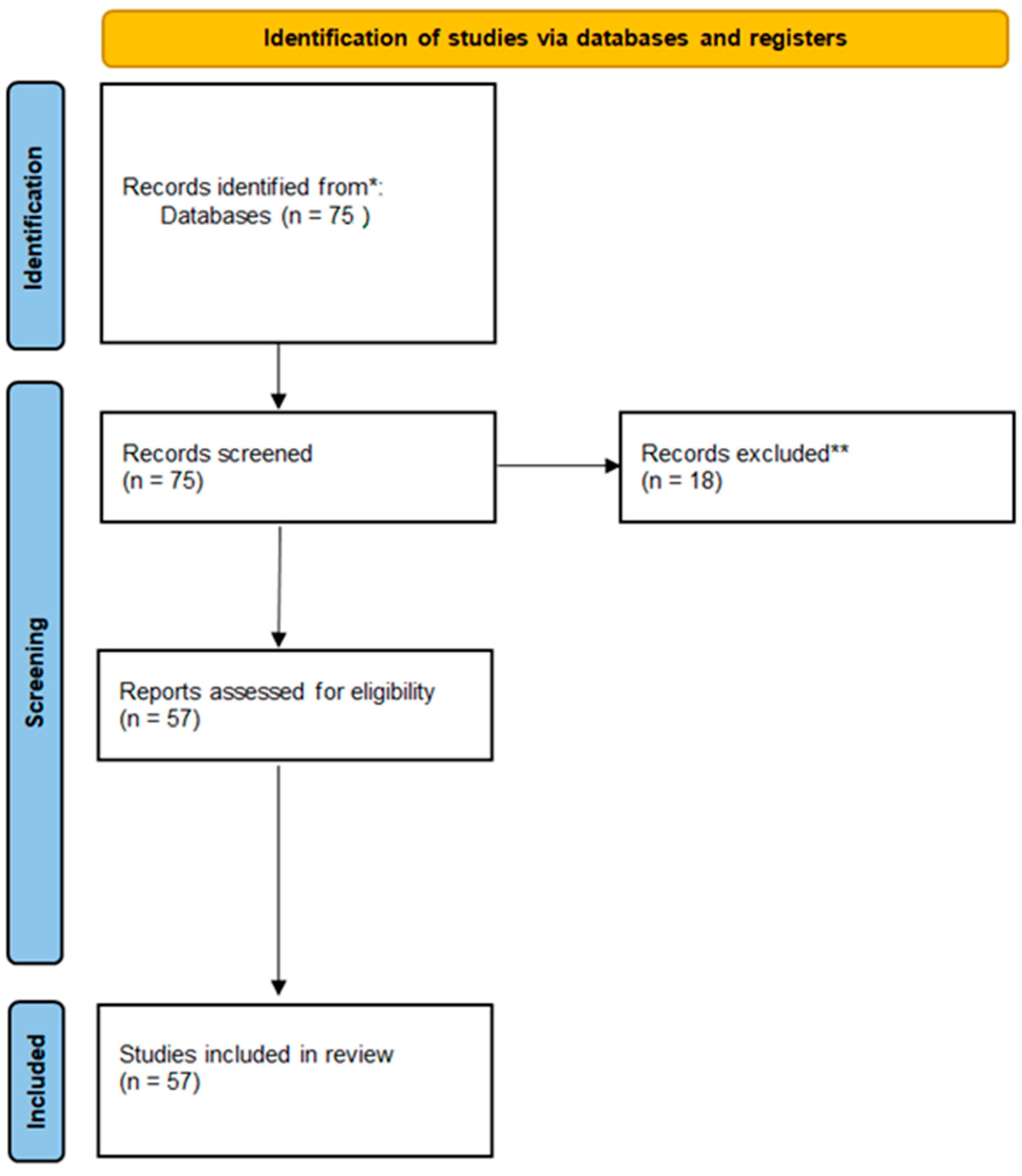

Singh et al. 2020). The search uses “Blended Finance” OR “Partial Risk Guarantee” keywords. There is no limit on the year, and all the articles published from 2005 to the date (March 2023) were considered in the report. The language is set to English and the source type to a journal. This resulted in 57 articles. Therefore, 57 articles were analysed to identify the key factors and trends in the blended finance and partial risk guarantee research area. The summary of the article identification process is presented in the

Figure 1 displayed below.

Figure 1 shows the bibliometric flowchart through PRISMA.

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis

Bibliometric analysis is a valuable review methodology that is computer-assisted. It is used to identify the current trends and core research areas. It is a rigorous methodology used to explore and analyse large data sets. The bibliometric analysis provides a macro view of studies and can generate networks and themes. It is a quantitative approach that tracks, evaluates, and explains the published research (

Small 1973;

Dzikowski 2018;

Vieira et al. 2022). The bibliometric analysis allows the author to examine the research area in many ways. Authors can analyse based on authors, countries, organisations, keywords, journals, and documents. It provides the researcher with a transparent and systematic idea of the area. This method also provides the researcher with quality and quantity information. The number of citations of specific published articles also measures the quality of the bibliometric research. At the same time, the quantity is measured by the total number of publications.

It is a structural analysis, as it provides the reader with current trends and patterns in the research area, along with information about the frontrunners in the domain in terms of countries, institutes, authors, and shifts (

Singh et al. 2020). Additionally, the interpretation is supported by a network visualisation. Graphs of co-citation analysis of journals, co-occurrences of crucial phrases, and bibliographical coupling of countries are developed using the VOS viewer and R Studio.

VOS viewer (v 1.6.19) is used for creating bibliometric networks and graphs. These are interpreted by VOSviewers, which provide the bibliometric data in an easily digestible format.

R Studio is used for creating bibliometric networks and descriptive statistics. The bibliometrix package in R Studio is used for network visualisation and descriptive statistics.

3. Results

The descriptive statistics of the bibliometric analysis are given below in

Table 1.

3.1. Publications and Citations

A partial risk guarantee is a novel concept that originated in the early 2000s. The first article published in the research areas is as late as 2005. The trend of partial risk guarantee and blended finance research picked up post COVID-19, with only approximately 20 articles published between 2005 and 2020. The author with the most citations is Professor Emma Mawdsley (University of Cambridge), with a total citation count of 79 (

Table 2).

Table 3 lists the authors with the highest number of documents. Seven authors have two publications each. As this is a relatively new domain, the literature is still developing.

3.2. Organisations and Countries

Table 4 enumerates the organisations with the highest total citations worldwide. The majority of citations emanate from universities in the United Kingdom. The table concludes that the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, is the leading organisation with the highest number of citations, i.e., 57. This distribution also includes many emerging nations.

Table 5 tabulates the organisations with the most documents—Blue Finance leads, and Centre De Recherche Insulaire Et Observatoire De L’environnement and the University of Cambridge follow close behind it.

The following network (

Figure 2) illustrates the organisations with the maximum number of co-authorships among them. This means the authors from specific universities authored a paper together. As observed from the figure, the Department of Economics (University of London), Cambridge University (London), Department of Humanities and Social Sciences (California), and Institute for Global Climate Change and Energy have co-authored the maximum number of documents.

Figure 3 represents the most productive countries and the co-authorships among them. The United Kingdom and the United States are two countries that have the maximum number of co-authorships with other countries and each other. Notably, a few emerging nations feature in the list, along with India. India is seeing significant developments in this area in recent times.

Table 6 below lists the countries according to the highest number of citations.

Table 7 depicts the most productive countries based on the highest number of publications. The United Kingdom and the United States lead the list with 18 and 10 publications, respectively, with decent representation from emerging nations.

Figure 4 represents the organisations with the maximum number of bibliographic couplings. This signifies that the work presented by the two organisations references a common third work in their manuscript. In other words, it means that one organisation has written a manuscript and referenced a third organisation, and the second organisation has also written a manuscript referencing the same third organisation in their work.

Figure 4 exhibits that the paper published by 18 out of the 109 organisations on blended finance and partial risk guarantees has the maximum bibliographic coupling. As seen in

Figure 4 above, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China; School of Rural Management, XIM University, India; Africa Policy Research Institute, Germany; Blue Finance Ecre (economics for coral reef ecosystems), Barbados; University of Nigeria, Nigeria; and University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, have the highest bibliographic coupling among them. This means that these organisations have cited a common work in their bibliography.

Figure 5 represents the bibliographic coupling of the documents/articles. The bibliographic coupling of documents shows the two papers that have cited a third common work the most. The document published by Havemann et al. (2020) has the maximum bibliographic coupling by citing a common third paper.

Figure 6 illustrates the bibliographic coupling among the countries. The figure depicts that the United Kingdom and the United States have the maximum bibliographic coupling by referencing a common third work. The most substantial network in the figure above is of (Havemann et al. 2020; Jia 2020; Murray and Spronk 2019; Anago 2022). This illustrates that these documents have referenced a third common work in their bibliography and have tried to explore a similar theme to each other.

3.3. Journals Analysis

Following is the list of journals with the maximum number of publications. As indicated in

Table 8 and

Figure 7, the

Dialogues in Human Geography journal has the highest number of citations (57), followed by the

Ecosystem Services (26) and

Agriculture and Human Values (25) journals.

Figure 8 depicts the journals with the maximum bibliographic coupling.

Agriculture and Human Values and

Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment have the highest bibliographic coupling among the journals.

3.4. Keywords Analysis

A keyword co-network analysis can be used to keep track of research themes and new domains because keywords offer crucial insight into the article’s content. Authors’ keywords, which are the original keywords provided by the authors, and keyword plus, which are Scopus’ indexing keywords, are two alternate sets of keywords that Scopus provides that the study analyses. The current study reveals new areas for research, such as impact investment, developing countries, conservation finance, public–private partnership, and philanthropic funds.

Figure 9 below depicts the authors’ keywords.

Figure 9 shows four crucial keywords that emerge from the list, i.e., Blended Finance, SDGs, Climate Finance, and Investment. There are other prominent keywords, albeit with lower co-occurrence. PRG, a part of blended finance, can be utilised to mobilise funds in various sections, such as climate finance, biodiversity conservation, water and sanitation, and SDGs. The co-occurrence analysis in

Table 9 highlights using keywords in tandem. This means the network highlights the keywords used in a single publication. As seen from the table below, Blended Finance is the most co-occurring keyword, along with other keywords. This showcases that Blended Finance has consistently been used as a keyword in the documents.

Figure 10 below depicts the indexed keyword co-occurrence. The most prominent circles denote the usage of keywords in the document. The more significant the node is, the greater the number of keyword co-occurrences. As seen from the figure below, Finance is the most central node, with blue colour, and is linked to other keywords to show the usage of two keywords together. For example, Finance is co-occurring with Climate Change in documents, so authors are exploring the domain of climate change and how to finance the fiscal deficit.

Table 10 describes the Scopus indexing keyword co-occurrence. The trend for the most mentioned keywords, i.e., Finance, Investment, Sustainable Development Goals, and Climate Change, has been increasing.

Figure 11 depicts all the keywords combined. This figure indicates that Blended Finance has the highest occurrence out of any other keywords mentioned in the figure. Blended Finance has the most substantial network and links, depicting that authors have used Blended Finance the most with Sustainable Development Goals, Investment, Climate Change, Climate Financing, Development, COVID-19, Environmental Economics, Public Spending, Developing World, etc.

3.5. Thematic Analysis Using Keywords

3.5.1. Climate Finance

The influence of climate change on an economy’s financial, economic, and health problems has been highly erratic (

Adhikari 2022). Up to 2050, growing and developing economies will need an astounding USD 6 trillion in funding for net zero emissions (

Songwe et al. 2022). Climate change must be addressed holistically to reduce adverse environmental impacts (

Bracking and Leffel 2021). Higher carbon footprints, lower cleaner energy, water pollutants, and many others depict the negative spillovers of climatic conditions and can be detrimental to human health. Private investment has been considered highly significant in curbing climate change’s adverse and inevitable effects. However, many private investors are reluctant to invest in emerging markets because of typical roadblocks, such as inadequate infrastructure, ambiguous climate regulations, and lax reporting requirements (

Mukherjee 2023). To overcome these obstacles, public and charitable donors need catalytic assistance to encourage private investment to help achieve the SDGs (

Li et al. 2022). Climate financing is adopting investment practices that enhance the contribution of resources from private and public entities to mitigate the negative repercussions of climate change (

Colenbrander et al. 2022).

Investments through blended finance involve the pivotal role of stakeholders, such as regulators, philanthropic institutions, governments, and private investors, to contribute to a sustainable ecosystem (

Ni et al. 2023). Blended financing aims to draw additional funding by offering private investors a subsidised credit line backed by guarantees (

Chhetri et al. 2021). Financial markets’ role in contributing towards improving climatic conditions has been crucial (

Gonçalves et al. 2022). The significance of the blended finance approach has been coherent post COVID-19, as policymakers and government officials are exploring more innovative vehicles to adapt to the prominent effects of climate policies (

Li et al. 2022).

3.5.2. Sustainable Development Goals

The agenda of the United Nations to implement 17 SDGs and 169 targets comprises a transformative shift from the myopic view of economic growth towards a more resilient and developed economy (

D’Souza and Jain 2022). However, limited funds’ financial and economic bottlenecks bind businesses to operate sustainably. In the wake of streamlining impact investments to bridge the upsurging demand and SDG deficit of USD 4.2 trillion (

Convergence 2022), sustainable financing has garnered the interest of various academicians, policymakers, and researchers.

The overall goal of impact investments is to contribute towards sustainability and optimise social welfare through adopting blended finance (

ODI 2019). Private and philanthropic investors are exploring instruments under blended finance, such as PRGs, to utilise the mandatory CSR expenditure by leveraging the financial resources to create a higher spillover effect. One of the critical goals of blended finance is to upscale the underprivileged sections of society, who can contribute towards economic growth and development and overcome poverty (

Arora and Sarker 2023). Blended finance can help de-risk the investment to achieve sustainable development goals through a robust mechanism involving public and private investors (

Farber and Reichert 2023). The crises of unemployment and poverty have gripped several economies, especially post COVID-19, which has crippled the potential of health and sanitation infrastructure and accessibility. The negative influence of the pandemic has posed operating challenges for businesses in developing and pacing with the sustainable environment (

Boichenko et al. 2022).

3.5.3. Investment

The only natural way to catch up to the sustainable development goals is to make genuine investments at scale (

UNCTAD 2023). Developing countries face a fiscal deficit of USD 4.2 trillion annually in sustainable development goal achievement (

UNCTAD 2023). There is a need to reform the whole financial system to catalyse private investment through mobilising public or philanthropic funding to bridge the financial gap for sustainable development (

Convergence 2022). Impact investment is another domain that has been highlighted in the bibliometric analysis. Impact investment is paramount for generating societal benefits; environmental benefits, if applicable in specific scenarios; and financial profits.

Through various financing arrangements, donors actively seek ways to “de-risk investment” (

Mawdsley 2018). One of the ways is to infuse private investment by utilising public or private funds to create opportunities and provide working capital (

Bayliss and Van-Waeyenberge 2018). There is a need to make investments that intend to have a verifiable, positive social and environmental impact and a financial return (Havemann et al. 2020).

Investment is crucial to increase sustainability across diverse stakeholders and financial ecosystems (

Havemann et al. 2022). The sustainable development goals aim to eradicate poverty and hunger in society. The underserved section of our community requires support to become economically better. For these people to receive genuine socioeconomic opportunities, for their local organisations to provide for the necessities of life, for their nations to develop, and for them to contribute to the sustainable management of the world’s natural resources, significant additional investment is needed (

Havemann et al. 2022). This is a strategy in investment, also known as impact investment. Impact assessment is performed for the investment made in terms of social, environmental, and economic benefit to society. This theme is upcoming in the blended finance and partial risk guarantee research areas, as the utmost need for finances is in the SDGs and climate financing domain.

PRG helps increase the investments’ effectiveness as the leverage effect occurs. However, real impact investments for sustainable development will rarely be profitable enough to compete with those focused on financial returns, rather than societal or economic returns (

Rode et al. 2019). PRG also promotes the combination of public–private partnerships through investments. This is achieved by using public/private/philanthropic funds to unlock additional capital through a private entity or a public entity for the betterment of society. Such genuine impact investments should be rewarded by investors willing to accept lower financial return rates (

Rode et al. 2019).

3.5.4. Blended Finance and Partial Risk Guarantee

A strategy known as blended finance uses grant and concessional funds from philanthropic sources to mobilise private resources for societal improvement and the pursuit of sustainable development goals (

Mawdsley 2018). It is a valuable instrument when investors feel they could lose money without a guarantor because the perceived risk is so significant. Blended finance uses public and charitable funds to bring in private capital to reduce the risk for the investor or lender, rather than making them the only parties (

NITI Aayog 2022).

Through blended finance, several players can accomplish multiple goals, such as societal advancement, economic diversification, monetary gain, innovation, etc. When conventional financing or market mechanisms are unavailable, blended finance is essential for the market because it benefits society, the economy, and donors by mobilising private and public capital to switch to market-based models (

NITI Aayog 2022).

However, the crucial issue is that even though different parties have started to employ the blended finance structure, its full potential has not yet been realised (

KPMG 2020). This issue can be tackled with the advent of PRG, a form of blended finance that works effectively in utilising private and public capital.

4. Discussion

The motive behind implementing the blended finance approach is to synchronise climate-based investments with the sustainability ecosystem. In the blended finance method, the partial risk guarantee (PRG) is a crucial financial tool since it enables cash to flow to the borrower to achieve desired goals while sharing the investor’s risk. Several barriers prevent the utilisation of charitable funds for social and financial support, notwithstanding corporations’ willingness to contribute to these initiatives. These challenges include murky rules, an absence of pertinent literature, and a lack of evidence for valuable models. Philanthropic funding can increase access to finance and lower the risk associated with commercial investment. Therefore, PRGs must be used to pool public and private resources, offer startup funding, and maintain the flow of money for small enterprises that they would otherwise be unable to assess. It is crucial to lyse the present literature on blended finance and partial risk guarantees to establish the needs and advantages.

PRG is an important blended finance tool, as it will help sort the issues arising in funding for sustainable development, climate financing, and the progress of developing nations. For this purpose, we conducted a bibliometric analysis to analyse the current literature and realise the recent trends, prominent authors, journals, organisations, and countries in the domain to have a holistic idea of the research area.

The keywords identified through the bibliometric analysis are integrated and complement each other regarding overall social welfare. The review exhibits that the maximum number of citations for the blended finance approach has been cited in the United Kingdom. At the same time, many emerging nations are researching more about utilising blended finance instruments. The emergence and need for innovative tools are arising to create sustainable impact and optimise additional investments to increase public–private partnerships. The analysis describes keywords that form a network and provides a comprehensive overview of blended finance and the arenas where it is mainly employed.

The evolution of any domain is the most critical aspect. Our results show that certain publications are a catalyst for jumpstarting the PRG domain. Around 50 articles have been published since 2005, when this area started developing. From its inception in the area of transportation in developing countries to the most influential in financing SDGs, it has numerous applications and directions.

The blended finance approach operates to combat climate risks and finance the rising SDG deficit. In accordance with the attainment of SDGs, the partial risk guarantee scheme offers various benefits to the implementation partners (borrowers) through additional funds and enhanced accessibility to function smoothly. The guarantee scheme integrates the pool of resources from private and public investors to de-risk capital and achieve a greener environment. It aligns the interests of borrowers and lenders by offering green and sustainability-linked loans and creating more opportunities for smart-based climate investments (

World Bank 2021).

From sustainable development and climate financing to political situations and innovative energy infrastructure, blended finance and PRG have no limits. The research and work in PRG must keep growing, as a substantial fiscal deficit will not be bridged with only public or private funds.

Many economies are eventually impacted by uncontrollable and adverse climatic conditions, such as pollution, floods, droughts, etc. It has been further intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has worsened the risks that need to be mitigated through financial support.

From the perspective of attainment of SDGs, risk guarantees provide a platform for assisting infrastructural and technical support to firms and organisations aiming to upscale people grappling with poverty, hunger, poor sanitation, unemployment, and illiteracy. Water, sanitation, agriculture, marine conservation, energy infrastructure, etc. all see the utilisation of partial risk guarantees. The authors in this area are developing innovative ways to implement this ecosystem to combat the abovementioned issues. Developed nations, such as the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands, Switzerland, etc., are becoming forerunners. Even though these countries are not fairing as severely as the developing and underdeveloped countries regarding the fiscal deficit, they are still looking for sustainable solutions in blended financing. Developing and underdeveloped countries are joining the foray, albeit at a slower pace.

Traditional finance carries some inherent investing risks. Nevertheless, blended finance reduces these risks by combining PRG with a guarantor, who assumes a portion of the risk. The financial rewards and impacts are transformed for the investor into social and economic implications as blended finance is used in the development sector. Using economic synergy, blended finance enables leveraging money to draw in many investors and boost their impact. Countries can lessen their reliance on public funding and the perceived investment risk using the PRG scheme. There is a need to encourage financial investment in climate-resilient and sustainable development initiatives and expand current public–private partnerships to advance the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal.

The underserved segment of our society will ultimately benefit from achieving sustainable development goals; hence, reducing the fiscal deficit is paramount. The PRG initiative empowers impoverished youth by providing them with jobs and the means to improve their economic circumstances, ultimately benefiting society.

The bibliometric analysis of blended finance and partial risk guarantees opens avenues for future researchers. There is considerable potential in figuring out the ecosystem for PRG and blended finance and how it can be implemented in theory and practice. Questions regarding identifying the best methods to implement PRG as an innovative tool of blended finance and its implications for managers, policymakers, and host governments remain unanswered. Researchers can further the research by answering these questions and contributing to the literature, which will help to understand PRG and, consequently, help reduce the sustainable development goal fiscal deficit. The factors examined in this study can be tested empirically. There is a lack of models that work for PRG and can be constructed to further this study.

5. Conclusions

The soaring SDG deficit and turbulent environmental conditions of economies have motivated donor governments, private investors, and philanthropic institutions to innovate the allocation of funds through grants, guarantees, concessional capital, and technical assistance funds. This research highlights the emergence of blended finance and partial risk guarantees as a structured approach for catalysing additional capital for the overall development of the involved stakeholders and communities. The emerging trend of blended finance and partial risk guarantees has been promoted further recently, especially after the health crisis due to COVID-19, which has alarmed governments, policymakers, and investors to adapt to this innovative approach. PRG, one of the archetypes of the blended finance approach, holds its relevance for shielding the interests of the risk investors by diversifying the potential risks. The sustainable motive invigorates the functionality and adoption of blended finance and partial risk guarantees by cumulating a pool of resources from private, public, and philanthropic investors. The growing demand for financial resources and a skilled workforce has necessitated the employment of a blended finance approach for developmental additionality.

The thematic analysis in this study showcases the integrity of the sustainability platform’s blended finance and partial risk guarantee approach. The results show that blended finance and partial risk guarantees are paramount in climate finance, biodiversity conservation, water, sanitation, public–private partnership, investment, impact investment, and SDGs to mobilise funding to reduce the fiscal deficit. This blended tool is gaining momentum in developed countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and other European countries. Developing countries are also starting to venture into the area. Organisations—such as the Department of Economics, University of London; Cambridge University, London; Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, California; and Institute for Global Climate Change and Energy—co-authoring the maximum number of documents highlights that renowned institutions realise the importance of this process. The United Kingdom and the United States of America have the maximum number of publications out of all the countries worldwide.

The study also underlines the PRG scheme as one of the crucial instruments of blended finance that provides partial coverage to the risk investor against the risk of default. The scheme leverages financial capital to assist small-scale borrowers, NGOs (Non-governmental organisations), and NPOs (Non-profit organisations) in meeting infrastructure and working capital requirements. Therefore, the role and cruciality of blended finance and partial risk guarantees as innovative vehicles need to culminate for the optimisation of sustainable development. These results are substantiated by the publications happening in the research area. Journals such as Dialogues in Human Geography, Ecosystem Services, and Agriculture and Human Values lead the list with maximum citations and clearly show the multifaceted use of partial risk guarantees and blended finance.

However, developing nations must push towards a faster approach towards adopting the process and publishing about it, as they are the ones that are in dire need of such innovative financial instruments to combat the fiscal deficit. Multinational companies and businesses are transitioning towards sustainability by deploying their CSR funds as partial risk guarantees. The mandate provides myriad opportunities for companies to contribute towards creating financial and economic additionality. Blended finance and partial risk guarantees assist the companies in overcoming challenges posed by creating leverage impact and multiplying the societal and economic gain for the country and its citizens, especially the underserved section of its society.

Author Contributions

K.S.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation. T.M.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation. S.J.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. S.D. (Sanjay Dhir): conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. N.R.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. R.Y.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. S.D. (Sidharth Dua): conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. A.G.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. A.B.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. H.S.: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualisation, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by IPE Global Limited (MI02658G). The financial support for this work did not influence its outcome.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article, as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adhikari, Ratnakar. 2022. Leveraging aid for trade to mobilise climate finance in the least developed countries. Global Policy 13: 547–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, Rashmi-Umesh, and Tapan Sarker. 2023. Financing for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the Era of COVID-19 and beyond. The European Journal of Development Research 35: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayliss, Kate, and Elisa Van-Waeyenberge. 2018. Unpacking the public-private partnership revival. The Journal of Development Studies 54: 577–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskaran, Rajesh Kumar. 2023. Sustainability Initiatives, Knowledge-Intensive Innovators, and ‘Firms’ Performance: An Empirical Examination. International Journal of Financial Studies 11: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boichenko, Kateryna, Stefan Cristian Ghergina, António Abreu, Mário Nuno Mata, and José Moleiro Martins. 2022. Towards Financing System of Integrated Enterprise Development in the Time of COVID-19 Outbreak. International Journal of Financial Studies 10: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracking, Sarah, and Benjamin Leffel. 2021. Climate finance governance: Fit for purpose? WIREs Climate Change 12: e709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, Arun-Khatri, Tek-B Sapkota, Bjoern-O Sander, Jacobo Arango, Katherine-M Nelson, and Andreas Wilkes. 2021. Financing climate change mitigation in agriculture: Assessment of investment cases. Environmental Research Letters 16: 124044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirambo, Dumisani. 2021. Corporate Sector Policy Innovations for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Implementation in the Global South: The Case of sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Sustainability Research 3: e210011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colenbrander, Sarah, Laetitia Pettinoti, and Yue Cao. 2022. A Share of Climate Finance: An Appraisal of Past Performance, Future Pledges, and Prospective Contributors. UNFCCC Working Paper. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/ODI_A_fair_share_of_climate_finance.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Convergence. 2022. Available online: https://www.convergence.finance/blended-finance (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- D’Souza, Renita, and Shruti Jain. 2022. Bridging the SDGs Financing Gap in Least Developed Countries: A Roadmap for the G20. Occasional Paper No. 376. Delhi: Observer Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Dzikowski, Piotr. 2018. A bibliometric analysis of born global firms. Journal of Business Research 85: 281–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, Vanina, and Patrick Reichert. 2023. Blended Finance and the SDGs: Using the Spectrum of Capital to de-Risk Business Model Transformation. In Measuring Sustainability and CSR: From Reporting to Decision-Making. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Farza, Khouloud, Zied Ftiti, Zaineb Hlioui, Waël Louhichi, and Abdelwahed Omri. 2021. Does it pay to go green? The environmental innovation effect on corporate financial performance. Journal of Environmental Management 300: 113695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, Tiago-Cruz, João Dias, and Victor Barros. 2022. Sustainability Performance and the Cost of Capital. International Journal of Financial Studies 10: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurcan, Faith, Gonca Gokce Menekse Dalveren, and Mohammad Derawi. 2022. COVID-19 and E-Learning: An Exploratory Analysis of Research Topics and Interests in E-Learning during the Pandemic. IEEE Access 10: 123349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havemann, Tanja, Christine Negra, and Fred Werneck. 2022. Blended finance for agriculture: Exploring the constraints and possibilities of combining financial instruments for sustainable transitions. Agricultural Human Values 37: 1281–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepburn, Cameron, Brian O’Callaghan, Nicholas Stern, Joseph Stiglitz, and Dimitri Zenghelis. 2020. Will COVID-19 fiscal recovery packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change? Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36: S359–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDFC. 2019. Blended Finance: A Brief Overview. Available online: https://www.idfc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/blended-finance-a-brief-overview-october-2019_final.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- KPMG. 2020. Blended Finance- an Underutilised Approach with Great Potential? Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/04/bended-finance-an-underutilized-approach-with-great-potential.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Li, Bo, Fabio Natalucci, and Prasad Ananthakrishan. 2022. How Blended Finance Can Support Climate Transition in Emerging and Developing Economies. IMF Blog. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/11/15/how-blended-finance-can-support-climate-transition-in-emerging-and-developing-economies (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Li, Boyan, Chao Wang, Yunchen Wang, Wei Wang, and Aiwen Lin. 2023. Impact assessment of China’s inter-provincial trade on sustainable development goals. Journal of Cleaner Production 388: 135983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, Alberto, Enrique Orduna-Malea, Mike Thelwall, and Emilio-Delgado López-Cózar. 2018. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. Journal of Informetrics 12: 1160–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawdsley, Emma. 2018. From billions to trillions. Dialogues in Human Geography 8: 191–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, Promit. 2023. Bridging the Climate Finance Gap: Catalysing Private Capital for Developing and Emerging Economies. Delhi: Observer Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Na, Dongrui Wu, Xiaofang Xie, Yingtong Chen, Zhui Jian, Jincheng Qiu, and Peichang Zhang. 2023. Foundations as sustainability partners: Climate philanthropy finance flows in China. Climate Policy 23: 446–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NITI Aayog. 2022. Reimagining Healthcare in India through Blended Finance. Available online: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-02/AIM-NITI-IPE-whitepaper-on-Blended-Financing.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- ODI. 2019. Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/blended-finance-in-the-poorest-countries-the-need-for-a-better-approach/ (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- OECD. 2018. Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/making-blended-finance-work-for-the-sustainable-development-goals_9789264288768-en (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- OECD. 2020. Building Back Better: A Sustainable, Resilient Recovery after COVID-19. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=133_133639-s08q2ridhf&title=Building-back-better-_A-sustainable-resilient-recovery-after-COVID-19 (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Pereira, Javier. 2017. Blended Finance: What It Is, How It Works and How It Is Used. Oxford: Oxfam International. [Google Scholar]

- Rode, Julian, Alexandra Pinzon, Marcelo C. C. Stabile, Johannes Pirker, Simone Bauch, Alvaro Iribarrem, Paul Sammon, Carlos A. Llerena, Lincoln Muniz Alves, Carlos E. Orihuela, and et al. 2019. Why ‘blended finance’ could help transitions to sustainable landscapes: Lessons from the Unlocking Forest Finance project. Ecosystem Services 37: 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Shiwangi, Sanjay Dhir, V. Mukunda Das, and Anuj Sharma. 2020. Bibliometric overview of the technological forecasting and social change journal: Analysis from 1970 to 2018. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 154: 119963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, Henry. 1973. Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 24: 265–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, Geetesh, Thomas Wilkinson, Emmanuelle Daviaud, Donela Besada, C. R. Tamandjou Tchuem, Sumaiyah Docrat, and Susan Cleary. 2021. Managing the healthcare demand-supply gap during and after COVID-19: The need to review the approach to healthcare priority-setting in South Africa. South African Medical Journal 111: 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songwe, Vera, Nicholas Stern, and Amar Bhattacharya. 2022. Finance for Climate Action: Scaling Up Investment for Climate and Development. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 2022. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2022.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- UNCTAD. 2023. More Investment Needed to Get Global Goals Back on Track, Says UNCTAD Chief. Available online: https://unctad.org/news/more-investment-needed-get-global-goals-back-track-says-unctad-chief-0#:~:text=Developing%20countries%20face%20a%20%244,at%20record%20speed%20in%202022 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- UNIDO. 2007. Corporate Social Responsibility and Public Policy: The role of Governments in Facilitating the Uptake of CSR among SMEs in Developing Countries. Discussion Paper. Available online: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2008-06/Discussion_Paper_0.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Vieira, Elisabete, Mara Madaleno, and Júlio Lobão. 2022. Gender Diversity in Leadership: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Directions. International Journal of Financial Studies 10: 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2008. World Bank Guarantee Products: IDA Partial Risk Guarantee. Available online: https://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01599/siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGUARANTEES/Resources/IDA_PRG.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- World Bank. 2021. What You Need to Know About Green Loans. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/10/04/what-you-need-to-know-about-green-loans (accessed on 10 March 2023).

Figure 1.

Bibliometric analysis flowchart through PRISMA. * Database used for identification of article- SCOPUS. ** Records excluded due to irrelevancy to the research question/objective, lacking data, duplication, not related to the topic.

Figure 1.

Bibliometric analysis flowchart through PRISMA. * Database used for identification of article- SCOPUS. ** Records excluded due to irrelevancy to the research question/objective, lacking data, duplication, not related to the topic.

Figure 2.

Co-authorship of organisations.

Figure 2.

Co-authorship of organisations.

Figure 3.

Co-authorship of countries.

Figure 3.

Co-authorship of countries.

Figure 4.

Bibliographic coupling of organisations.

Figure 4.

Bibliographic coupling of organisations.

Figure 5.

Bibliographic coupling of documents.

Figure 5.

Bibliographic coupling of documents.

Figure 6.

Bibliographic coupling of countries.

Figure 6.

Bibliographic coupling of countries.

Figure 7.

Top sources with the highest citations.

Figure 7.

Top sources with the highest citations.

Figure 8.

Bibliographic coupling of journals.

Figure 8.

Bibliographic coupling of journals.

Figure 9.

Author keyword co-occurrence.

Figure 9.

Author keyword co-occurrence.

Figure 10.

Indexed keyword co-occurrence.

Figure 10.

Indexed keyword co-occurrence.

Figure 11.

All keywords’ co-occurrence.

Figure 11.

All keywords’ co-occurrence.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of bibliometric analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of bibliometric analysis.

| Main Information |

|---|

| Timespan | 2005:2023 |

| Sources (Journals, Books, etc.) | 47 |

| Documents | 57 |

| Document average age | 2.19 |

| Average citations per doc | 4.509 |

| References | 3280 |

| Author’s keywords | 229 |

| Authors | 137 |

| Single-authored docs | 19 |

| Co-authors per doc | 2.53 |

| International co-authorships % | 31.58 |

| Articles | 50 |

| Note | 1 |

| Review | 6 |

Table 2.

Top 20 most influential authors based on the highest number of citations.

Table 2.

Top 20 most influential authors based on the highest number of citations.

| S. No. | Authors | Total Citations | Total Documents |

|---|

| 1 | Mawdsley E. | 79 | 2 |

| 2 | Lightfoot S. | 22 | 1 |

| 3 | Szent-Iványi B. | 22 | 1 |

| 4 | Havemann T. | 20 | 1 |

| 5 | Negra C. | 20 | 1 |

| 6 | Werneck F. | 20 | 1 |

| 7 | Alaerts G.J. | 19 | 1 |

| 8 | Bauch S. | 16 | 1 |

| 9 | Iribarrem A. | 16 | 1 |

| 10 | Llerena C.A. | 16 | 1 |

| 11 | Muniz Alves L. | 16 | 1 |

| 12 | Orihuela C.E. | 16 | 1 |

| 13 | Pinzon A. | 16 | 1 |

| 14 | Pirker J. | 16 | 1 |

| 15 | Rode J. | 16 | 1 |

| 16 | Sammon P. | 16 | 1 |

| 17 | Stabile M.C.C. | 16 | 1 |

| 18 | Wittmer H. | 16 | 1 |

| 19 | Bracking S. | 14 | 1 |

| 20 | Leffel B. | 14 | 1 |

Table 3.

Top 20 most influential authors based on the highest number of documents.

Table 3.

Top 20 most influential authors based on the highest number of documents.

| S. No. | Authors | Total Documents | Total Citations |

|---|

| 1 | Brathwaite A. | 2 | 13 |

| 2 | Chowdhury A. | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | Clua E. | 2 | 13 |

| 4 | Mawdsley E. | 2 | 79 |

| 5 | Pascal N. | 2 | 13 |

| 6 | Snel M. | 2 | 0 |

| 7 | Sorensen N. | 2 | 0 |

| 8 | Abraham-Dukuma M.C. | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | Ahmed Y. | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | Alaerts G.J. | 1 | 19 |

| 11 | Alfaro E.P. | 1 | 0 |

| 12 | Alhassan L. | 1 | 2 |

| 13 | Aliyu Abubakar H.K. | 1 | 0 |

| 14 | Ameli N. | 1 | 2 |

| 15 | Anafo A. | 1 | 11 |

| 16 | Anago C.J. | 1 | 2 |

| 17 | Anago J.C. | 1 | 1 |

| 18 | Asamoah E. | 1 | 11 |

| 19 | Badjie F. | 1 | 1 |

| 20 | Baroncelli E. | 1 | 1 |

Table 4.

Top 20 most influential organisations based on the highest number of citations.

Table 4.

Top 20 most influential organisations based on the highest number of citations.

| S. No. | Affiliation | Country | Total Citations | Total Documents |

|---|

| 1 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom | 57 | 1 |

| 2 | Clarmondial Ag | Switzerland | 20 | 1 |

| 3 | Versant Vision Llcny | United States | 20 | 1 |

| 4 | Global Center on Adaptation | Netherlands | 19 | 1 |

| 5 | IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education | Netherlands | 19 | 1 |

| 6 | Global Canopy Programme | United Kingdom | 16 | 1 |

| 7 | Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research | Germany | 16 | 1 |

| 8 | Instituto De Pesquisa Ambiental Da Amazônia | Brazil | 16 | 1 |

| 9 | Instituto Nacional De Pesquisas Espaciais | Brazil | 16 | 1 |

| 10 | International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis | Austria | 16 | 1 |

| 11 | International Institute for Sustainability | Brazil | 16 | 1 |

| 12 | Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina | Peru | 16 | 1 |

| 13 | Vivid Economics | United Kingdom | 16 | 1 |

| 14 | Department of Geography, School of Global Affairs, King’s College London | United Kingdom | 14 | 1 |

| 15 | Department of Sociology, University of California | United States | 14 | 1 |

| 16 | Blue Finance Ecre | Barbados | 13 | 2 |

| 17 | Centre De Recherche Insulaire Et Observatoire De L’environnement | French Polynesia | 13 | 2 |

| 18 | Department of Computer Science, University of Ghana | Ghana | 11 | 1 |

| 19 | Department of Construction Technology and Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology | Ghana | 11 | 1 |

| 20 | Department of Management Studies | Ghana | 11 | 1 |

Table 5.

Top 20 most influential organisations based on the highest number of documents.

Table 5.

Top 20 most influential organisations based on the highest number of documents.

| S. No. | Affiliation | Country | Total Documents | Total Citations |

|---|

| 1 | Blue Finance Ecre | Barbados | 2 | 13 |

| 2 | Centre De Recherche Insulaire Et Observatoire De L’environnement | French Polynesia | 2 | 13 |

| 3 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom | 1 | 57 |

| 4 | Clarmondial Ag | Switzerland | 1 | 20 |

| 5 | Versant Vision Llcny | United States | 1 | 20 |

| 6 | Global Center on Adaptation | Netherlands | 1 | 19 |

| 7 | IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education | Netherlands | 1 | 19 |

| 8 | Global Canopy Programme | United Kingdom | 1 | 16 |

| 9 | Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research (Ufz) | Germany | 1 | 16 |

| 10 | Instituto De Pesquisa Ambiental Da Amazônia | Brazil | 1 | 16 |

| 11 | Instituto Nacional De Pesquisas Espaciais | Brazil | 1 | 16 |

| 12 | International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis | Austria | 1 | 16 |

| 13 | International Institute for Sustainability | Brazil | 1 | 16 |

| 14 | Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina | Peru | 1 | 16 |

| 15 | Vivid Economics | United Kingdom | 1 | 16 |

| 16 | Department of Geography, School of Global Affairs, King’s College London | United Kingdom | 1 | 14 |

| 17 | Department of Sociology, University of California | United States | 1 | 14 |

| 18 | Department of Computer Science, University of Ghana | Ghana | 1 | 11 |

| 19 | Department of Construction Technology and Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology | Ghana | 1 | 11 |

| 20 | Department of Management Studies, University of Education | Ghana | 1 | 11 |

Table 6.

Top 15 countries with the highest number of citations.

Table 6.

Top 15 countries with the highest number of citations.

| S. No. | Country | Total Documents | Total Citations |

|---|

| 1 | United Kingdom | 18 | 121 |

| 2 | United States | 10 | 35 |

| 3 | Netherlands | 3 | 29 |

| 4 | Switzerland | 4 | 23 |

| 5 | Germany | 4 | 17 |

| 6 | Barbados | 2 | 13 |

| 7 | France | 2 | 13 |

| 8 | French Polynesia | 2 | 13 |

| 9 | South Africa | 4 | 8 |

| 10 | Belgium | 2 | 6 |

| 11 | Italy | 5 | 4 |

| 12 | Qatar | 2 | 4 |

| 13 | Nigeria | 3 | 3 |

| 14 | Australia | 3 | 2 |

| 15 | India | 2 | 2 |

Table 7.

Top 15 countries with the maximum number of publications.

Table 7.

Top 15 countries with the maximum number of publications.

| S. No. | Country | Total Documents | Total Citations |

|---|

| 1 | United Kingdom | 18 | 121 |

| 2 | United States | 10 | 35 |

| 3 | Italy | 5 | 4 |

| 4 | Switzerland | 4 | 23 |

| 5 | Germany | 4 | 17 |

| 6 | South Africa | 4 | 8 |

| 7 | Netherlands | 3 | 29 |

| 8 | Nigeria | 3 | 3 |

| 9 | Australia | 3 | 2 |

| 10 | Indonesia | 3 | 1 |

| 11 | Barbados | 2 | 13 |

| 12 | France | 2 | 13 |

| 13 | French Polynesia | 2 | 13 |

| 14 | Belgium | 2 | 6 |

| 15 | Qatar | 2 | 4 |

Table 8.

Top journals with the highest citations.

Table 8.

Top journals with the highest citations.

| S. No. | Journals | Total Documents | Total Citations |

|---|

| 1 | Dialogues in Human Geography | 1 | 57 |

| 2 | Agriculture and Human Values | 2 | 25 |

| 3 | Ecosystem Services | 2 | 25 |

| 4 | Political Quarterly | 1 | 22 |

| 5 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 3 | 20 |

| 6 | Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change | 1 | 14 |

| 7 | International Journal of Energy Sector Management | 1 | 11 |

| 8 | Water (Switzerland) | 1 | 10 |

| 9 | Geoforum | 1 | 8 |

| 10 | Development (Basingstoke) | 2 | 7 |

| 11 | Journal of Contemporary European Research | 1 | 6 |

| 12 | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment | 2 | 6 |

| 13 | Development Policy Review | 1 | 4 |

| 14 | Journal of Development Studies | 1 | 4 |

| 15 | Journal of Environmental Management | 1 | 4 |

Table 9.

Author keyword co-occurrence.

Table 9.

Author keyword co-occurrence.

| S. No. | Author Keywords | Co-Occurrence |

|---|

| 1 | Blended Finance | 27 |

| 2 | Climate Finance | 4 |

| 3 | Investment | 4 |

| 4 | Sustainable Development Goals | 4 |

| 5 | Conservation Finance | 3 |

| 6 | Finance | 3 |

| 7 | Impact Investment | 3 |

| 8 | SDGs | 3 |

| 9 | Sustainable Development | 3 |

| 10 | Africa | 2 |

Table 10.

Indexed keyword co-occurrence.

Table 10.

Indexed keyword co-occurrence.

| S. No. | Author Keywords | Co-Occurrence |

|---|

| 1 | Finance | 11 |

| 2 | Private Sector | 11 |

| 3 | Investment | 9 |

| 4 | Investments | 6 |

| 5 | Sustainable Development Goals | 6 |

| 6 | Sustainable Development | 5 |

| 7 | Climate Change | 4 |

| 8 | Public–Private Partnership | 4 |

| 9 | Risk Assessment | 4 |

| 10 | Banking | 3 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).