The Effect of Javanese Language Videos with a Community Based Interactive Approach Method as an Educational Instrument for Knowledge, Perception, and Adherence amongst Tuberculosis Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

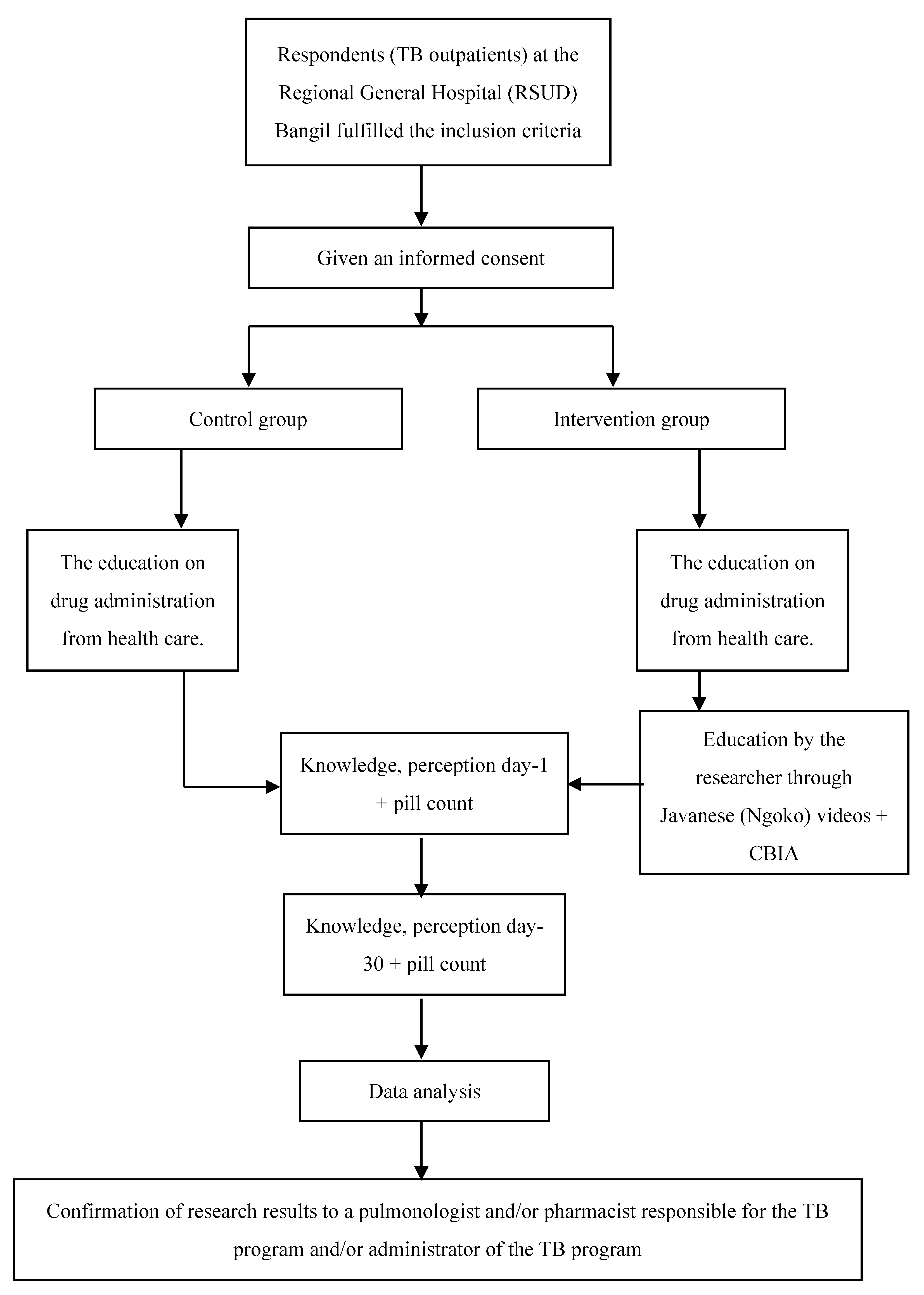

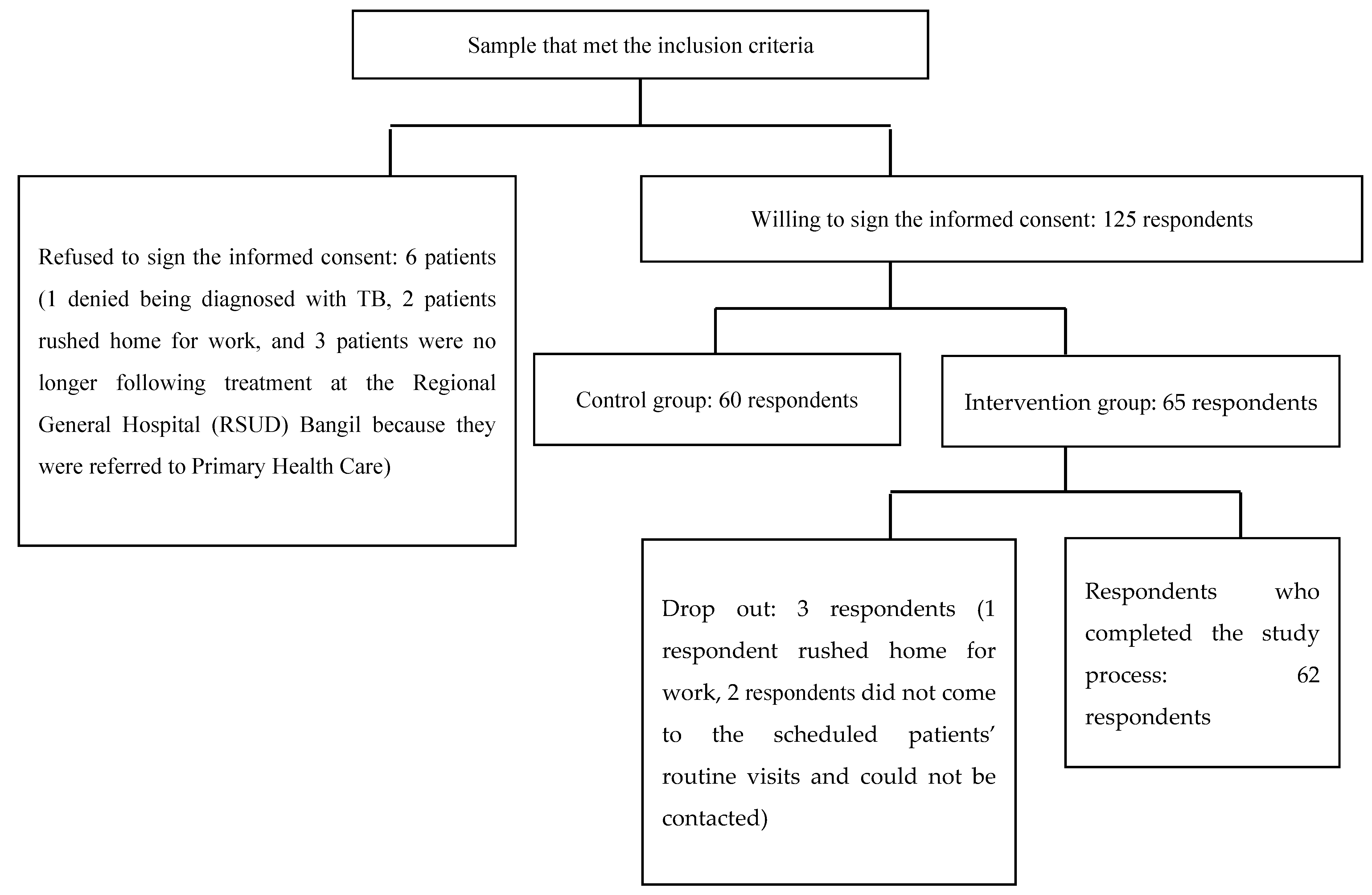

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Respondents

2.2. Data Validity Test

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- TBC iku mlebu penyakit nular opo gak?

- ☐

- Lara sing nular (poin = 1)

- ☐

- Dudu lara sing nular (poin = 0)

- ☐

- Gak ngerti utawa bingung (poin = 0)

- Lara TBC iki sebabe opo?

- ☐

- Bakteri Mycobacterium tuberculosis (poin = 1)

- ☐

- Jamur (poin = 0)

- ☐

- Virus (poin = 0)

- ☐

- Parasit (poin = 0)

- ☐

- Gak ngerti utawa bingung (poin = 0)

- Tondo-tondo TBC iku opo? Tau ngalami dewe? ...... Sak piro suwene? .......(lek jawaban bener ≥3 = poin 1; jawaban bener <3 = 0)

- ☐

- Metu kringet adem lek bengi

- ☐

- Lemah, lemes, lepok

- ☐

- Ambekan sesek lan dodo lara koyok disuduk

- ☐

- Panas sak wulan luwih

- ☐

- Bobote mudhun

- ☐

- Nafsu mangan mudun

- ☐

- Watuk riak’en rong minggu luwih lan onok getih e

- Coro TBC nular yo opo? (lek jawaban bener ≥2 = poin 1; jawaban bener <2 = 0)

- ☐

- Watuk ☐ Anginlek ☐ Wahing ☐ Ngidu ☐ Nafas

- Biasane sampeyan cara ngombe obate yo opo? (lek jawaban bener ≥1 = poin 1)

- ☐

- Sak-elinge

- ☐

- Diombe lek wayahe watuk tok, utawa panas tok

- ☐

- Isuk utawa bengi, sak jam sadurunge mangan (bener)

- ☐

- Isuk utawa bengi, rong jam sak wise mangan (bener)

- ☐

- Pas waktune utawa tetep waktune utawa pancet waktune ben dino e (bener)

- ☐

- Gak ngerti utawa lali utawa bingung

- Sampeyan tau lali ngombe obat TBC? (lek jawaban bener ≥1 = poin 1)

- ☐

- Tau →Langsung ngombe dobel obat e saka biasae

- ☐

- Tau →Langsung ngombe pas eling (bener)

- ☐

- Tau →Kandha dokter (bener)

- ☐

- Tau →Gak ngombe obat sampe wayahe kontrol maneh

- ☐

- Gak tau lali (bener)

- ☐

- Bingung

Lek tau lali, opo sing sampeyan lakukno ben gak gampang lali? (data deskriptif) - Jare dokter, sak piro suwene sampeyan kudu ngombe obat TBC iki? (jawaban bener poin = 1)

- ☐

- Rong minggu luwih (poin = 0)

- ☐

- 1 wulan (poin = 0)

- ☐

- 2 wulan (poin = 0)

- ☐

- 3 wulan (poin = 0)

- ☐

- 6 wulan utawa luwih tergantung penyakite (poin = 1)

- Opo ae macem e obat TBC sing sampeyan ombe? ngerti jeneng e? (lek jawaban bener ≥2 = poin 1; jawaban bener <2 = 0)

- ☐

- Isoniazid (INH) ☐ Pirazinamid

- ☐

- Rifampisin ☐ Streptomisin injeksi

- ☐

- Etambutol

- Tondo-tondo opo ae sing perlu diwaspadai marine ngombe obat TBC? (lek jawaban bener ≥2 = poin 1; jawaban bener <2 = 0)

- ☐

- Uyuh e abang ☐lara weteng ☐gringgingen

- ☐

- muneg-muneg lan muntah ☐ora nafsu mangan ☐nyeri sendi

- ☐

- budeg ☐gatel-gatel lan abang-abang nde kulit

- ☐

- kuning ☐mripat e bureng

- Opo sing sampeyan lakukno lek onok keluhan koyok muneg-muneg lan muntah, lara weteng, gak nafsu mangan marine ngombe obat? (jawaban bener 2 = poin 1; jawaban bener <2 = 0)

- ☐

- Mandeg ngombe obat, wes gak gelem ngombe obat maneh sateruse

- ☐

- Ganti ngombe obat herbal

- ☐

- Ganti obat liyane ora kandha dokter

- ☐

- Diombe isuk utawa bengi sakwise mangan (bener)

- ☐

- Kandha dokter (bener)

- Lek uyuh e abang sakwise ngombe obat, sampeyan ngerti penyebabe obat opo?

- ☐

- Rifampisin (poin = 1)

- ☐

- Isoniazid (poin = 0)

- ☐

- Etambutol (poin = 0)

- ☐

- Pirazinamid (poin = 0)

- ☐

- Streptomisin (poin = 0)

- Opo akibat e lek ngombe obat TBC gak teratur? (lek jawaban bener ≥2 = poin 1; jawaban bener <2 = 0)

- ☐

- Ngulang pengobatane utawa tambah suwe waras e (bener)

- ☐

- Obat e gak mempan maneh (bener)

- ☐

- Penyakit e tambah akeh (bener)

- ☐

- Gak ngerti utawa bingung

References

- de Kraker, M.E.A.; Stewardson, A.J.; Harbarth, S. Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report: Executive Summary 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/GraphicExecutiveSummary.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Surya, A.; Setyaningsih, B.; Nasution, H.S.; Parwati, C.G.; Yuzwar, Y.E.; Osberg, M.; Hanson, C.L.; Hymoff, A.; Mingkwan, P.; Makayova, J.; et al. Quality tuberculosis care in Indonesia: Using Patient Pathway Analysis to optimize public–private collaboration. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S724–S732. (accessed on 29 August 2019). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasuruan Regency Health Office. Profil Kesehatan Kabupaten Pasuruan Tahun. 2015. Available online: http://www.depkes.go.id/resources/download/profil/PROFIL_KAB_KOTA_2015/3514_Jatim_Kab_Pasuruan_2015.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Pradipta, I.S.; Houtsma, D.; van Boven, J.F.M.; Alffenaar, J.-W.C.; Hak, E. Interventions to improve medication adherence in tuberculosis patients: A systematic review of randomized controlled studies. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2020, 30, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, L.A.; Zamzami, M.; Aldin, S.; Pazdirek, J. Clinical consequences of non-compliance with directly observed therapy short course (DOTS): Story of a recurrent defaulter. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2012, 1, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürthauer, J.; Flamm, M.; Sönnichsen, A. Patient and physician related factors of adherence to evidence based guidelines in diabetes mellitus type 2, cardiovascular disease and prevention: A cross sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indonesian Ministry of Health (IMOH). Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 72 Tahun 2016 tentang Standar Pelayanan Kefarmasian di Rumah Sakit; Direktorat Jenderal Bina Kefarmasian dan Alat–Kesehatan Kementerian Kesehatan RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016; Available online: http://farmalkes.kemkes.go.id/?wpdmact=process&did=NDA5LmhvdGxpbms= (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Clark, R.C.; Mayer, R.E. E-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning, 4th ed.; John Wiley &Sons Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, M.; Nair, G.; Staunton, C.; Pather, M.; Garrett, N.; Baadjies, D.; Kidd, M.; Moodley, K. Impact of an educational video as a consent tool on knowledge about cure research among patients and caregivers at HIV clinics in South Africa. J. Virus Erad. 2018, 4, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Owaifeer, A.M.; Alrefaie, S.M.; Alsawah, Z.M.; Al Taisan, A.A.; Mousa, A.; Ahmad, S.I. The effect of a short animated educational video on knowledge among glaucoma patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 12, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieland, M.L.; Nelson, J.; Palmer, T.; O’Hara, C.; Weis, J.A.; Nigron, J.A.; Sia, I.G. Evaluation of a tuberculosis education video among immigrants and refugees at an adult education center: A community-based participatory approach. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, H.; Grandjean Lapierre, S.; Razafindrina, K.; Andriamiadanarivo, A.; Rakotosamimanana, N.; Razafindranaivo, T.; Seimon, T.; Blalock, B.; Bello-Bravo, J.; Pittendrigh, B.; et al. Evaluating the use of educational videos to support the tuberculosis care cascade in remote Madagascar. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2020, 24, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.W.; Ramos, J.G.; Castillo, F.; Castellanos, E.F.; Escalante, P. Tuberculosis patient and family education through videography in El Salvador. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2016, 4, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhany, S.; Achmad, H.; Singgih, M.F.; Ramadhany, Y.F.; Inayah, N.H.; Mutmainnah, N. A review: Knowledge and attitude of society toward tuberculosis disease in Soppeng District. Sys. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Indonesian Ministry of Health (IMOH). Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor HK.01.07/MENKES/755/2019 tentang Pedoman Nasional Pelayanan KedokteranTata Laksana Tuberkulosis; Direktorat Jenderal Bina Kefarmasian dan Alat–Kesehatan Kementerian Kesehatan RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Pedoman Nasional Penanggulangan Tuberkulosis, 2nd ed.; Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2007.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis and Patient Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, N.E. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2015, 103, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgill, B.D.; Nolin, J. Learning Taxonomies in Medical Simulation; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Islands, FL, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559109/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Moss-Morris, R.; Petrie, J.W.K.; Horne, R.; Cameron, L.; Buick, D. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol. Health 2002, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achappa, B.; Madi, D.; Bhaskaran, U.; Ramapuram, J.T.; Rao, S.; Mahalingam, S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Alipanah, N.; Jarlsberg, L.; Miller, C.; Linh, N.N.; Falzon, D.; Jaramillo, E.; Nahid, P. Adherence interventions and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials and observational studies. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukartini, T.; Widianingrum, T.R.; Yasmara, D. The relationship of knowledge and motivation with anti tuberculosis drugs compliance in tuberculosis patients. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 603–606. [Google Scholar]

- Nezenega, Z.S.; Perimal-Lewis, L.; Maeder, A.J. Factors influencing patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Ethiopia: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarjana, K.D.; Sukartini, T.; Makhfudli, M. Level of attitude, medication adherence, and quality of life among patients with tuberculosis. J. Nurs. Healthc. Res. 2019, 2, 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfahuneygn, G.; Medhin, G.; Legesse, M. Adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment and treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients in Alamata District, northeast Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandwalo, E.R.; Morkve, O. Knowledge of disease and treatment among tuberculosis patients in Mwanza, Tanzania. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2000, 4, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, R.; Hamilton, A.F. How does your own knowledge influence the perception of another person’s action in the human brain? Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2012, 7, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.; Chung, C.; Jung, S.S.; Park, H.K.; Lee, S.-S.; Lee, K.M. Understanding illness perception in pulmonary tuberculosis patients: One step towards patient-centered care. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putera, I.; Pakasi, T.A.; Karyadi, E. Knowledge and perception of tuberculosis and the risk to become treatment default among newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis patients treated in primary health care, East Nusa Tenggara: A retrospective study. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyasulu, P.; Sikwese, S.; Chirwa, T.; Makanjee, C.; Mmanga, M.; Babalola, J.O.; Mpunga, J.; Banda, H.T.; Muula, A.S.; Munthali, A.C. Knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions of tuberculosis among community members in Ntcheu district, Malawi. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Nagla, S.; Morten, S.; Asma, E.; Arja, A. Illness perceptions and quality of life among tuberculosis patients in Gezira, Sudan. Afr. Health Sci. 2015, 15, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jamaludin, T.S.S.; Ismail, N.; Saidi, S. Knowledge, awareness, and perception towards tuberculosis disease among International Islamic University Malaysia Kuantan students. Enferm. Clin. 2019, 29, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodor, E.A. The feelings and experiences of patients with tuberculosis in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolitan District: Implications for TB Control Efforts. Ghana Med. J. 2012, 46, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zainal, S.M.; Sapar; Syafruddin; Irwandy. The effect of patients’ perception about tuberculosis (TB) against treatment compliance. Enferm. Clin. 2020, 30, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Boogaard, J.; Msoka, E.; Homfray, M.; Kibiki, G.S.; Heldens, J.J.H.M.; Felling, A.J.A.; Aarnoutse, R.E. An exploration of patient perceptions of adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Tanzania. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesty, U.A.F.; Tjekyan, R.M.S.; Zulkarnain, M. Medical compliance determinants for tuberculosis patients in Palembang. J. Ilmu Kesehat. Masy. 2020, 11, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, A.P.; Fathana, P.B.; Affarah, W.S. The correlations of knowledge, attitude and practice with compliance in treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Puskesmas Cakranegara. J. Biol. Trop. 2021, 21, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhao, A.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Z.; Jian, X.; Wang, W.; et al. Non-adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment among internal migrants with pulmonary tuberculosis in Shenzhen, China: A cross-sectionalstudy. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, M.S.; Suryani, N.; Murdani, P. Hubungan persepsi dan tingkat pengetahuan penderita tuberkulosis dengan kepatuhan pengobatan di wilayah kerja puskesmas buleleng I. J. Magister Kedokt. Kel. 2013, 1, 14–23. Available online: https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/13494-ID-hubungan-persepsi-dan-tingkat-pengetahuan-penderita-tuberkulosis-dengan-kepatuha.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Molina, R.L.; Kasper, J. The power of language-concordant care: A call to action for medical schools. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Intervention Group (n = 60) | Control Group (n = 62) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.46 | ||

| Male | 25 (42) | 30 (48) | |

| Female | 35 (58) | 32 (52) | |

| Age (years old) | 0.69 | ||

| 15 to <23 | 9 (15) | 10 (16) | |

| 23 to <31 | 16 (27) | 12 (19) | |

| 31 to <39 | 12 (20) | 7 (11) | |

| 39 to <47 | 7 (12) | 12 (19) | |

| 47 to <55 | 6 (10) | 6 (10) | |

| 55 to <63 | 7 (12) | 9 (15) | |

| 63 to <71 | 2 (3) | 5 (8) | |

| ≥71 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Education | 0.77 | ||

| Primary school | 20 (33) | 25 (40) | |

| Secondary school | 13 (22) | 13 (21) | |

| High school | 20 (33) | 20 (32) | |

| University | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | |

| Other 1 | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Knowledge | |||

| Lara TB 2 | 1.68 | 1.65 | 0.80 |

| Cara ngombe OAT 3 | 1.48 | 1.53 | 0.89 |

| Efek samping OAT 4 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.24 |

| Perception | |||

| Timeline | 3.13 | 3.27 | 0.51 |

| Consequence | 6.40 | 6.32 | 0.64 |

| Personal control | 5.94 | 5.93 | 0.31 |

| Treatment control | 4.11 | 3.95 | 0.12 |

| Illness coherence | 7.00 | 6.82 | 0.30 |

| Variable | Intervention Group (n = 60) | Control Group (n = 62) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||

| Lara TB 1 | 3.95 | 1.75 | <0.001 |

| Cara ngombe OAT 2 | 3.47 | 1.52 | <0.001 |

| Efek samping OAT 3 | 3.21 | 0.80 | <0.001 |

| Perception | |||

| Timeline | 2.56 | 3.30 | <0.001 |

| Consequence | 6.26 | 6.38 | 0.70 |

| Personal control | 6.00 | 5.85 | 0.01 |

| Treatment control | 4.10 | 3.97 | 0.17 |

| Illness coherence | 3.00 | 6.70 | <0.001 |

| Time | Intervention Group (n = 60) | Control Group (n = 62) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pill count, day-1 | 58.06% | 51.67% | 0.48 |

| Pill count, day-30 | 95.16% | 63.33% | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herawati, F.; Megawati, Y.; Aslichah; Andrajati, R.; Yulia, R. The Effect of Javanese Language Videos with a Community Based Interactive Approach Method as an Educational Instrument for Knowledge, Perception, and Adherence amongst Tuberculosis Patients. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020086

Herawati F, Megawati Y, Aslichah, Andrajati R, Yulia R. The Effect of Javanese Language Videos with a Community Based Interactive Approach Method as an Educational Instrument for Knowledge, Perception, and Adherence amongst Tuberculosis Patients. Pharmacy. 2021; 9(2):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020086

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerawati, Fauna, Yuni Megawati, Aslichah, Retnosari Andrajati, and Rika Yulia. 2021. "The Effect of Javanese Language Videos with a Community Based Interactive Approach Method as an Educational Instrument for Knowledge, Perception, and Adherence amongst Tuberculosis Patients" Pharmacy 9, no. 2: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020086

APA StyleHerawati, F., Megawati, Y., Aslichah, Andrajati, R., & Yulia, R. (2021). The Effect of Javanese Language Videos with a Community Based Interactive Approach Method as an Educational Instrument for Knowledge, Perception, and Adherence amongst Tuberculosis Patients. Pharmacy, 9(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9020086