Prescriber-Initiated Engagement of Pharmacists for Information and Intervention in Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Context

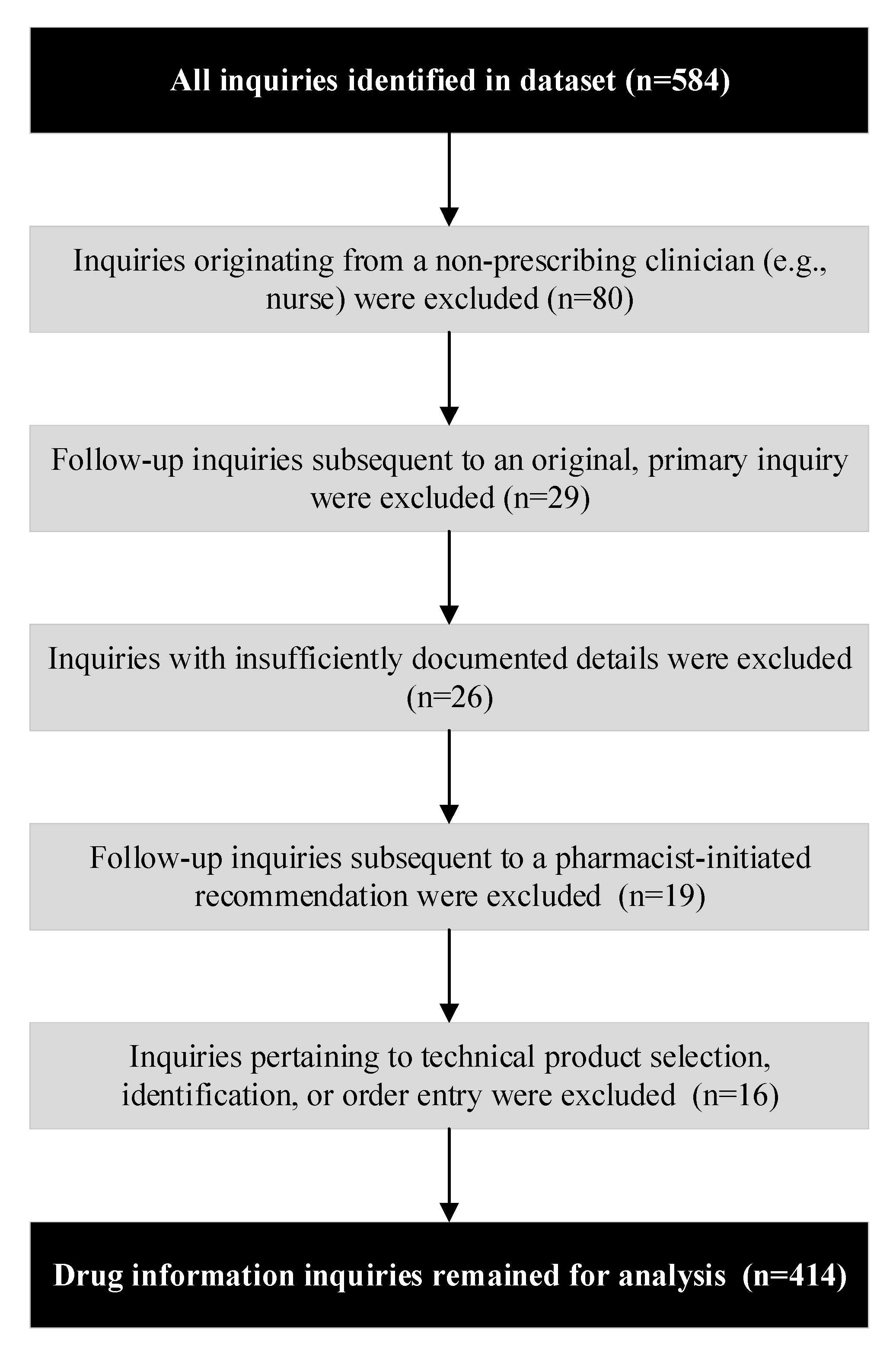

2.3. Data Source and Study Sample

2.4. Procedures and Definitions

2.5. Statistical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Terms | Number of Inquiries in Which Search Term Appears (N = 199 Inquiries) | % of Inquiries in Which Term Appears | Number of Inquiries Where This Is the Only Search Term Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommend | 64 | 32% | 17 |

| Interaction | 39 | 20% | 15 |

| Suggest | 35 | 18% | 11 |

| Advise | 20 | 10% | 5 |

| Cost | 20 | 10% | 1 |

| A1c | 14 | 7% | 3 |

| Monitor | 14 | 7% | 0 |

| Alternative | 12 | 6% | 2 |

| Experienc_ | 12 | 6% | 4 |

| Idea | 12 | 6% | 2 |

| Expens_ | 11 | 6% | 2 |

| Swallow | 10 | 5% | 2 |

| Incidental finding (no search term) | 9 | 5% | 9 |

| Complain | 8 | 4% | 4 |

| EKG | 8 | 4% | 3 |

| What dose | 8 | 4% | 4 |

| Input | 7 | 4% | 2 |

| Price | 7 | 4% | 1 |

| Conversion | 6 | 3% | 1 |

| C/o(i.e., complaining of) | 5 | 3% | 1 |

| Consult | 5 | 3% | 1 |

| SSRI | 5 | 3% | 0 |

| Antidepress_ | 4 | 2% | 1 |

| Choos_ | 4 | 2% | 1 |

| Compliance | 4 | 2% | 1 |

| Opioid | 4 | 2% | 1 |

| Advice | 3 | 2% | 1 |

| Convert | 3 | 2% | 1 |

| Guidance | 3 | 2% | 1 |

| Opinion | 1 | 1% | 0 |

| What labs | 1 | 1% | 0 |

| Search Terms and Filters | Number of Inquiries in Which Search Term Appears (N = 215 Inquiries) | % of Inquiries in Which Term/Filter Appears | Number of Inquiries Where This Is the Only Term/Filter Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended | 58 | 27% | 4 |

| Wanted | 50 | 23% | 1 |

| Recommendation | 34 | 16% | 1 |

| Call | 31 | 14% | 1 |

| MD | 31 | 14% | 1 |

| Disease state management with anonymous pharmacist #1 filters applied | 28 | 13% | 0 |

| First name of anonymous nurse practitioner 1 | 24 | 11% | 1 |

| Level | 23 | 11% | 0 |

| Request | 23 | 11% | 1 |

| Provider | 22 | 10% | 1 |

| Review | 22 | 10% | 2 |

| Prescriber | 21 | 10% | 1 |

| Asked | 20 | 9% | 2 |

| Question | 17 | 8% | 2 |

| Would like | 17 | 8% | 0 |

| Alternative | 16 | 7% | 0 |

| Asked for | 16 | 7% | 2 |

| Suggestion | 12 | 6% | 0 |

| Secure e-mail filter | 12 | 6% | 1 |

| Seek | 11 | 5% | 0 |

| Disease state management with anonymous pharmacist #2 filters applied | 11 | 5% | 2 |

| Experiencing | 10 | 5% | 1 |

| Seeking | 10 | 5% | 0 |

| Advised | 8 | 4% | 1 |

| Explain | 7 | 3% | 0 |

| Like to know | 7 | 3% | 0 |

| Provided | 7 | 3% | 1 |

| Conversion | 6 | 3% | 0 |

| Doctor wanted | 5 | 2% | 0 |

| Reporting | 5 | 2% | 0 |

| Swallow | 5 | 2% | 0 |

| Advice | 4 | 2% | 0 |

| Assistance | 4 | 2% | 0 |

| CRNP | 4 | 2% | 0 |

| Crush | 4 | 2% | 0 |

| Cultures | 4 | 2% | 1 |

| Discussed | 4 | 2% | 0 |

| Doctor asked | 4 | 2% | 1 |

| Draw | 4 | 2% | 0 |

| S/t (i.e., spoke to) | 4 | 2% | 0 |

| Looking for | 3 | 1% | 0 |

| Received | 3 | 1% | 0 |

| Reports | 3 | 1% | 0 |

| Wondering | 3 | 1% | 0 |

| Complaining | 2 | 1% | 0 |

| Consult | 2 | 1% | 0 |

| Last name of anonymous physician 1 | 2 | 1% | 0 |

| Experience | 2 | 1% | 0 |

| Inquiring | 2 | 1% | 0 |

| Questioned | 2 | 1% | 0 |

| Reported | 2 | 1% | 0 |

| Advisement | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| Created by | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| Dr asked | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| Incidental finding (no search term) | 1 | 0% | 1 |

| First name of anonymous nurse practitioner 2 | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| First name of anonymous nurse practitioner 3 | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| Message from | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| Opinion | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| Received message | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| Treatment options | 1 | 0% | 0 |

| C/o (i.e., complaining of) | 0 | 0% | 0 |

| Gave prescriber | 0 | 0% | 0 |

| Got message | 0 | 0% | 0 |

| More information | 0 | 0% | 0 |

| New enrollee | 0 | 0% | 0 |

References

- Del Fiol, G.; Weber, A.I.; Brunker, C.P.; Weir, C.R. Clinical questions raised by providers in the care of older adults: A prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 005315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Fiol, G.; Workman, T.E.; Gorman, P.N. Clinical questions raised by clinicians at the point of care: A systematic review. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, H.; Gallagher, P.; Ryan, C.; Byrne, S.; O’Mahony, D. Potentially Inappropriate Medications Defined by STOPP Criteria and the Risk of Adverse Drug Events in Older Hospitalized Patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnitz, D.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Shehab, N.; Richards, C.L. Emergency Hospitalizations for Adverse Drug Events in Older Americans. New Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehab, N.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Geller, A.I.; Rose, K.O.; Weidle, N.J.; Budnitz, D. US Emergency Department Visits for Outpatient Adverse Drug Events, 2013–2014. JAMA 2016, 316, 2115–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, N.S.; Solomon, D.H.; Roth, C.P.; MacLean, C.H.; Saliba, D.; Kamberg, C.J.; Rubenstein, L.; Young, R.T.; Sloss, E.M.; Louie, R.; et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 139, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.-L.; Lu, Y.-H.; Chien, S.-C.; Chen, H.-H.; Chen, C.-Y. Questions Frequently Asked of Healthcare Professionals: A 2-Year Data Survey Conducted at a Medical Center. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotlib, D.; Bostwick, J.R.; Calip, S.; Perelstein, E.; Kurlander, J.E.; Fluent, T. Collaborative care in ambulatory psychiatry: Content analysis of consultations to a psychiatric pharmacist. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2017, 47, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schjott, J. Physicians’ questions concerning drug use among older patients: Experience from Norwegian drug information centres (RELIS) in the period 2010–2015. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; Fleming, M.; Martin-Misener, R.; Sketris, I.S.; MacCara, M.; Gass, D. Drug information resources used by nurse practitioners and collaborating physicians at the point of care in Nova Scotia, Canada: A survey and review of the literature. BMC Nurs. 2006, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Belden, J.; Koopman, R.; Steege, L.; Moore, J.; Canfield, S.M.; Kim, M.S. Information needs and information-seeking behaviour analysis of primary care physicians and nurses: A literature review. Heal. Inf. Libr. J. 2013, 30, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C.A.; Raehl, C.L.; Franke, T. Clinical pharmacy services and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 1999, 19, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, P.S.; Shevchuk, Y.M.; Remillard, A.J. Impact of the Dial Access Drug Information Service on Patient Outcome. Ann. Pharmacother. 2000, 34, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, U.; Damkier, P. Problem-oriented drug information: Physicians’ expectations and impact on clinical practice. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, T.; Zheng, J.; Jha, A. Use of UpToDate and outcomes in US hospitals. J. Hosp. Med. 2012, 7, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnsen, J.A.; Widnes, S.K.F.; Schjøtt, J. Analysis of questions about use of drugs in breastfeeding to Norwegian drug information centres. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2018, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazrou, D.A.; Ali, S.; Alzhrani, J.A. Assessment of queries received by the drug information center at King Saud medical city. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2017, 9, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjøtt, J.; Erdal, H. Questions about complementary and alternative medicine to the Regional Medicines Information and Pharmacovigilance Centres in Norway (RELIS): A descriptive pilot study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, C. The PACE Program: Home-Based Long-Term Care. Consult. Pharm. 2012, 27, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PACE by the Numbers. Available online: https://www.npaonline.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/pace_infographic_update_final_0719.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Vouri, S.M.; Tiemeier, A. The Ins and Outs of Pharmacy Services at a Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. Consult. Pharm. 2012, 27, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankes, D.L.; Amin, N.S.; Bardolia, C.; Awadalla, M.S.; Knowlton, C.H.; Bain, K.T. Medication-related problems encountered in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly: An observational study. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. (2003) 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, C.; Kraft, J.; Bungay, K. Optimizing inhaler use by pharmacist-provided education to community-dwelling elderly. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K.T.; Schwartz, E.J.; Knowlton, O.V.; Knowlton, C.H.; Turgeon, J. Implementation of a pharmacist-led pharmacogenomics service for the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PHARM-GENOME-PACE). J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. (2003) 2018, 58, 281–289 e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoth, A.B.; Carter, B.; Ness, J.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Shorr, R.I.; E Rosenthal, G.; Kaboli, P. Development and Reliability Testing of the Clinical Pharmacist Recommendation Taxonomy. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2007, 27, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.L.; McIlvain, H.E.; Lacy, N.L.; Magsi, H.; Crabtree, B.F.; Yenny, S.K.; Sitorius, M.A. Primary care for elderly people: Why do doctors find it so hard? Gerontologist 2002, 42, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, D.; Byrne, S.; Fleming, A.; Kearney, P.M.; Galvin, R.; Sinnott, C. GPs’ perspectives on prescribing for older people in primary care: A qualitative study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailabouni, N.J.; Nishtala, P.S.; Mangin, D.; Tordoff, J.M. Challenges and enablers of deprescribing: A general practitioner perspective. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, A.; Vartan, C.M.; Groppi, J.A.; Reyes, S.; Beckey, N.P. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy interventions in a Veterans Affairs medical center primary care clinic. Am. J. Heal. Pharm. 2013, 70, 1168–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Expert Panel, American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [CrossRef]

- English, B.A.; Dortch, M.; Ereshefsky, L.; Jhee, S. Clinically significant psychotropic drug-drug interactions in the primary care setting. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCance-Katz, E.F.; Sullivan, L.E.; Nallani, S. Drug interactions of clinical importance among the opioids, methadone and buprenorphine, and other frequently prescribed medications: A review. Am. J. Addict. 2010, 19, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Evans, A.; Jester, R. Nurse prescribers’ experiences of prescribing. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogdill, K. Information needs and information seeking in primary care: A study of nurse practitioners. J. Med Libr. Assoc. 2003, 91, 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Petriceks, A.; Olivas, J.C.; Srivastava, S. Trends in Geriatrics Graduate Medical Education Programs and Positions, 2001 to 2018. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holveck, C.A.; Wick, J.Y. Addressing the Shortage of Geriatric Specialists. Consult. Pharm. 2018, 33, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K.; Matos, A.; Knowlton, C.H.; McGain, D. Genetic variants and interactions from a pharmacist-led pharmacogenomics service for PACE. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K.T.; Knowlton, C.H.; Turgeon, J. Medication risk mitigation: Coordinating and collaborating with health care systems, universities, and researchers to facilitate the design and execution of practice-based research. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.A.M.; Austin, Z. Trust in interprofessional collaboration: Perspectives of pharmacists and physicians. Can. Pharm. J. (Ott) 2016, 149, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, D.; Laubscher, T.; Lyons, B.; Palmer, R. Integrating pharmacists into primary care teams: Barriers and facilitators. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 22, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillich, A.J.; McDonough, R.P.; Carter, B.; Doucette, W.R. Influential Characteristics of Physician/Pharmacist Collaborative Relationships. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004, 38, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motivation: | A Prescriber’s Primary Motivation for Contacting a Pharmacist is: |

| effectiveness | for help treating a medical condition that either (a) has not yet undergone treatment or (b) has not been adequately treated. |

| safety | to avoid, manage, mitigate, or identify actual or potential drug toxicity or unintended adverse reactions that may be in the context of clinical or laboratory abnormalities, drug allergies, unnecessary drug therapy, or drug interactions. |

| adherence | to resolve known or suspected (a) non-adherence, (b) non-receipt of a medication (e.g., inability to swallow, patient refusal of certain medications), or (c) risk factors that may cause non-adherence (e.g., improving a needlessly complex drug regimen). |

| cost | for assistance with pharmacotherapeutic decisions based on price quotes, pharmacoeconomic data, or formulary restrictions. |

| Information Need: | A Prescriber Needs a Pharmacist to: |

| modification of existing drug therapy | advise how to add to or change the existing therapy because the underlying disease has not been optimally treated, has been over-treated, has not been cost-effectively treated, or has been potentially unsafely treated with the current drug regimen. |

| dose selection or adjustment | advice regarding adjusting, selecting, tapering, or cross-tapering doses. |

| adverse events and side effects | identify, manage, or explain actual or suspected side effects or clinical abnormalities related to suspected drug toxicity; provide advice to change therapy to resolve the actual or potential adverse event/side effect. |

| new drug therapy selection | choose a drug for a new, untreated indication. |

| drug interactions | identify, manage, or explain drug-drug, simultaneous multi-drug, drug-disease, drug-gene, or drug-food interactions. |

| price quote | provide pricing information to help make a treatment decision. |

| monitoring parameters | advise how to monitor drug therapy for safety and/or efficacy or to interpret or explain aberrations in laboratory/clinical data, where aberrations are not suspected to be related to an adverse event. |

| general drug information | provide general drug information (pharmacology, contraindications/warnings, mechanism of action, storage conditions, active ingredients, intravenous flow rates, timing of administration, ability to crush/split, product availability, etc.) for educational purposes in order to inform decision making. |

| Characteristic | Value * |

|---|---|

| Participants | 359 |

| Age, mean ± SD (range) | 72.9 ± 9.8 (55–98) |

| Female | 251 (69.9) |

| Medications, mean ± SD (range) | 16.6 ± 6.6 (1–42) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 77 (21.4) |

| African American | 37 (10.3) |

| Hispanic | 5 (1.4) |

| Asian | 2 (0.6) |

| American Indian | 2 (0.6) |

| Unspecified | 236 (65.7) |

| DIIs per patient, mean ± SD (range) | 1.2 ± 0.4 (1–4) † |

| Prescribers | 102 |

| DIIs per prescriber, mean ± SD (range) | 4.1 ± 5.4 (1–29) |

| DIIs per prescriber, median (IQR) | 2 (1.5) |

| Physicians | 35 (34.3) |

| Female | 21 (60.0) |

| ≤5 years in practice | 1 (2.9) |

| 6–10 years in practice | 7 (20.0) |

| ≥11 years in practice | 27 (77.1) |

| Non-physician Prescribers | 67 (65.7) |

| Female | 64 (95.5) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 65 (97.0) |

| Physician Assistant | 2 (3.0) |

| ≤5 years in practice | 32 (47.8) |

| 6–10 years in practice | 21 (31.3) |

| ≥11 years in practice | 14 (20.9) |

| Pharmacists | 23 ‡ |

| Female | 16 (69.6) ‡ |

| DIIs per pharmacist, mean ± SD (range) | 18.0 ± 18.1 (1-65) ‡ |

| DIIs per pharmacist, median (IQR) | 12 (4,25) ‡ |

| PACE Sites | 59 |

| US Region | |

| Northeast | 28 (46.7) |

| South | 14 (23.3) |

| Midwest | 12 (20.0) |

| West | 5 (8.3) |

| Census | |

| <120 participants | 21 (35.6) |

| 120–220 participants | 25 (42.4) |

| >220 participants | 13 (22.0) |

| All Prescribers | Physicians | NPPs | P-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Information Inquiries, n (%) | 414 (100) | 149 (36.0) | 265 (64.0) | |

| Primary Motivation for Inquiry | 0.41 | |||

| Safety | 223 (53.9) | 84 (56.4) | 139 (52.5) | |

| Effectiveness | 107 (25.8) | 39 (26.2) | 68 (25.7) | |

| Adherence | 54 (13.0) | 14 (9.4) | 40 (15.1) | |

| Cost | 30 (7.2) | 12 (8.1) | 18 (6.8) | |

| Information Need | 0.09 | |||

| Modifications of existing drug therapy | 94 (22.7) | 30 (20.1) | 64 (24.2) | |

| Adverse events and side effects | 75 (18.1) | 23 (15.4) | 52 (19.6) | |

| Dose selections or adjustments | 61 (14.7) | 16 (10.7) | 45 (17.0) | |

| New drug therapy selections | 57 (13.8) | 24 (16.1) | 33 (12.5) | |

| Drug interactions | 52 (12.6) | 28 (18.8) | 24 (9.1) | |

| General drug information | 48 (11.6) | 18 (12.1) | 30 (11.3) | |

| Price quotes | 17 (4.1) | 6 (4.0) | 11 (4.2) | |

| Monitoring parameters | 10 (2.4) | 4 (2.7) | 6 (2.3) | |

| Drug Class Referenced by Prescriber † | ||||

| Antidepressants | 49 (11.8) | 20 (13.4) | 29 (10.9) | |

| Antidiabetic agents | 35 (8.5) | 8 (5.4) | 27 (10.2) | |

| Opioid analgesics | 30 (7.2) | 15 (10.1) | 15 (5.7) | |

| Antibiotics | 28 (6.8) | 14 (9.4) | 14 (5.3) | |

| Antihypertensives | 28 (6.8) | 6 (4.0) | 22 (8.3) | |

| Anticonvulsants | 26 (6.3) | 8 (5.4) | 18 (6.8) | |

| Antipsychotics | 15 (3.6) | 5 (3.4) | 10 (3.8) | |

| Hyperlipidemia agents | 14 (3.4) | 6 (4.0) | 8 (3.0) | |

| Inhaled agents for COPD/asthma | 13 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) | 11 (4.2) | |

| Antiplatelets/anticoagulants | 12 (2.9) | 4 (2.7) | 8 (3.0) | |

| Anxiolytics | 11 (2.7) | 7 (4.7) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Antifungals | 10 (2.4) | 5 (3.4) | 5 (1.9) | |

| Antisecretory agents | 9 (2.2) | 2 (1.3) | 7 (2.6) | |

| Vitamins/minerals | 9 (2.2) | 4 (2.7) | 5 (1.9) | |

| Natural products | 8 (1.9) | 2 (1.3) | 6 (2.3) | |

| Antigout agents | 7 (1.7) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (1.9) | |

| PDE inhibitors | 6 (1.4) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Sedative hypnotics | 6 (1.4) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Urinary incontinence agents | 5 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) |

| Recommendation | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Start alternative therapy | 70 (18.0) |

| Start or restart medication | 65 (16.7) |

| Dose change (reduce or increase) | 47 (12.1) |

| Start/alter therapy at specific dose | 42 (10.8) |

| Discontinue medication | 33 (8.5) |

| Laboratory or symptom monitoring | 33 (8.5) |

| Dosage form change | 29 (7.5) |

| Specific taper/titration plan | 20 (5.1) |

| Confirm a prescriber’s plan | 18 (4.6) |

| Schedule change | 15 (3.9) |

| No change in therapy | 10 (2.6) |

| Duration of treatment change | 4 (1.0) |

| Hold medication | 2 (0.5) |

| Specialist referral | 1 (0.3) |

| Total | 389 (100) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bankes, D.L.; Schamp, R.O.; Knowlton, C.H.; Bain, K.T. Prescriber-Initiated Engagement of Pharmacists for Information and Intervention in Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010024

Bankes DL, Schamp RO, Knowlton CH, Bain KT. Prescriber-Initiated Engagement of Pharmacists for Information and Intervention in Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleBankes, David L., Richard O. Schamp, Calvin H. Knowlton, and Kevin T. Bain. 2020. "Prescriber-Initiated Engagement of Pharmacists for Information and Intervention in Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly" Pharmacy 8, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010024

APA StyleBankes, D. L., Schamp, R. O., Knowlton, C. H., & Bain, K. T. (2020). Prescriber-Initiated Engagement of Pharmacists for Information and Intervention in Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. Pharmacy, 8(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010024