A Qualitative Study on Danish Student Pharmacists’ Attitudes Towards and Experience of Communication Skills Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Design and Interview Guide

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Sample Selection and Reqruitment

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

2.6. Interpretation of the Results

3. Results

3.1. Professional Communication vs. Normal Conversation

“Yes, but that is more or less just a conversation where you adapt a bit of the professional role.”(F1B)

“We have had some models, but when you get out there it has been my experience that you are just a normal decent human being”(F1A)

“You have to do a need assessment instead of standing there with some random communication models, which you can’t use for anything anyway.”(F1B)

3.2. Motivation to Engage in Training

“You can learn how to improve it [communication skills], but I also think that somehow, I don’t know, some willingness in relation to learning and so on.”(F3R)

“It’s about training; it’s about being committed and practice it.”(F2F)

“I am really not interested in learning it, that about communicating. /…/ Because I couldn’t see what we need it for.”(F1B)

3.3. How to Learn Communication Skills

“I think there are some who are more naturally talented than others, but I think everyone can acquire the right tools to be good at it [communication].”(F2I)

“I think a part of the problem is that, there is no good way to train it really.”(F1A)

“This [the CST experienced at the university] is kind of my only frame of reference, I am not really sure about how it could be done in a different way, I haven’t tried anything else.”(F3L)

“I think that is why we are a little vague about it [learning communication] now, because we ourselves are reflecting upon it [how to learn] as we speak. I believe.”(F2I)

“If you compare it to the laboratory work we’ve had, right, then we also had some theory at the lectures, and then we tried it in the lab; that does not mean we are Danish champions at titrating right? But it is kind of the same thing here, right. We get some theories, then we try it in practice afterwards at the pharmacy, and then later you need to specialize in communication if that is what you want.”(F1D)

“I think a lot of it was very theoretical. In general, I think that communication is practical so I think it gets like the theory of communication, I think it becomes a bit boring, but also difficult and hard to apply in practice.”(F3L)

“Like it is important to find the balance between receiving some tools that you can work with and try it in practice and get some personal feedback. Because that is what you really learn from. You don’t learn something from [looking at] someone standing and doing stuff that you are well aware that you shouldn’t do, but as soon as you get it told yourself [i.e., personal feedback], then you learn something.”(F3M)

3.4. Experience with CST

“Definitely, when I use them [the theories] in practice then I thought that it worked. Then there are at least some things you become aware of too, then you probably get some bad habits and so on, we all do, but at least it is something one thinks about and that you take with you, I think.”(F3O)

“I didn’t use them [the theories] I would say”. “I don’t think I did either”. “I don’t think I used them [the theories] consciously.”(F3Q, P, M)

“I think, or at least as I recall it, I remember it [CST] to be very pedagogical. That it wasn’t like a communication tool, but more like a ‘this is how you speak nice and friendly to the customers’ or like. I don’t remember that I got a tool out of it.”(F2I)

“I don’t necessary think it [improvement of communication] has something to do with it [the theory module at the university during internship]. Not in my case at least. I just think it was getting more and more experience.”(F2I)

3.5. Universities’ Role in Teaching Communications Skills

“I look at the university a bit like, it is a theoretically based education right. So well, all of the practical stuff, that might be something you learn besides from it or afterwards”(F1D)

“I think they [the university] have a small role, well they are supposed to, I understand that we should be more independent, but they should still prepare us for when we finish. It is an education we are taking, so well, they should prepare us for handling a job later on. So I definitely think that the university should play a role in it.”(F2G)

“The practical stuff like laboratory-work, that you can’t [learn without practical training] either. You can’t just sit and read McMurry [chemistry curriculum] three times in a row and then you are a champion in the laboratory.”(F1D)

4. Discussion

4.1. Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Affective Domain and Internalization

4.2. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model and CST

4.3. Practical Considerations

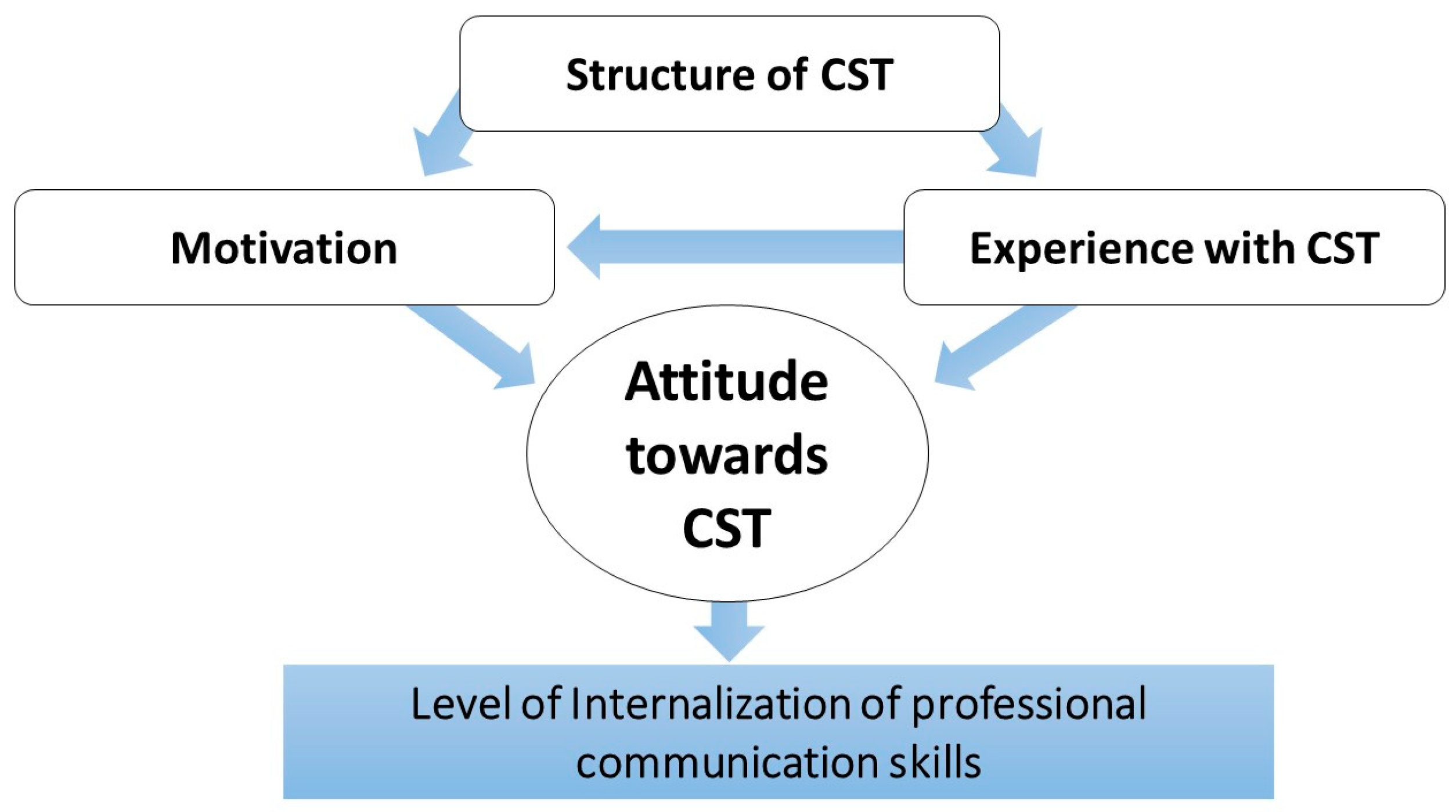

4.4. Practical Implications and Main Challenge

- Motivation: Getting all students to understand the importance of professional communication for a pharmacist, that this is learnable, and not something you are born with.

- Structuring CST: Structuring the training in such a manner that every student understands the necessity of it. Communicating this explicitly to the students so they feel they can use the feedback and knowledge constructively during their interactions with customers or other professionals.

- Experience: The Danish students have (almost) no experience of CST that they can relate to when discussing this subject. Hence, courses should be organized so that the students have some experience prior to theoretical teaching.

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hepler, C.D.; Strand, L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 1990, 47, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S. The state of the world’s pharmacy: A portrait of the pharmacy profession. J. Interpr. Care 2002, 16, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. ASHP Statement on Pharmaceutical Care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1993, 50, 1720–1723. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Consultative Group on the Role of the Pharmacist in the Health Care System; World Health Organization. Division of Drug Management and Policies. The Role of the Pharmacist in the Health Care System: Preparing the Future Pharmacist: Curricular Development: Report of a Third WHO Consultative Group on the Role of the Pharmacist; WHO/PHARM/97/599; World Health Organization: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1997; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Consultative Group on the Role of the Pharmacist in the Health Care System; World Health Organization. Pharmaceuticals Unit & WHO Meeting on the Role of the Pharmacist: Quality Pharmaceutical Services—Benefits for Governments and the Public, The Role of the Pharmacist in the Health Care System: Report of a WHO Consultative Group, New Delhi, India, 13–16 December 1988; Report of a WHO Meeting, Tokyo, Japan, 31 August–3 September 1993; WHO/PHARM/94.569; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP); International Pharmaceutical Students’ Federation (IPSF). Counseling, Concordance, Communication—Innovative Education for Pharmacists, 2nd ed.; International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP): The Hauge, The Netherlands, 2012; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Quality Assurance of Pharmacy Education: The FIP Global Framework, 2nd ed.; Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley, R.S. Communication Skills in Pharmacy Practice, a Practical Guide for Students and Practitioners, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, S.; Barber, N.; Elliott, R.; Hartley, E.; Horne, R. Patient-centred advice is effective in improving adherence to medicines. Pharm. World Sci. 2006, 28, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse. Lov om ændring af lov om apoteksvirksomhed og lov om tinglysning. In LBK nr 580; Lovtidende, A., Ed.; Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse: Vejle, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Toklu, H.Z.; Hussain, A. The changing face of pharmacy practice and the need for a new model of pharmacy education. J. Young Pharm. 2013, 5, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-da-Cunha, I.; Arguello, B.; Martinez, F.M.; Fernandez-Llimos, F. A Comparison of Patient-Centered Care in Pharmacy Curricula in the United States and Europe. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). FIPEd Gloabal Education Report; International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP): The Hauge, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jalal, Z.; Cox, A.; Goel, N.; Vaitha, N.; King, K.; Ward, J. Communications Skills in the Pharmacy Profession: A Cross Sectional Survey of UK Registered Pharmacists and Pharmacy Educators. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Silverman, J.; Draper, J. The ‘how’: Principles of how to teach and learn communication skills. In Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine, 2nd ed.; Radcliffe Medical: Abingdon, UK, 2005; pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Aspegren, K. BEME Guide No. 2: Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine-a review with quality grading of articles. Med. Teach. 1999, 21, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallman, A.; Vaudan, C.; Sporrong, S.K. Communications Training in Pharmacy Education, 1995–2010. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013, 77, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensberg, K. Facilitators and Barriers to Pharmacists’ Patient Communication: The Pharmacist Profession, the Regulatory Framework, and the Pharmacy Undergraduate Education. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Svensberg, K.; Björnsdottir, I.; Wallman, A.; Sporrong, S.K. Strategies for Enhancing Communication Skills Training: Lessons from 11 Nordic Pharmacy Schools. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. in press.

- Krathwohl, D.R.; Bloom, B.S.; Masia, B.B. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook II: Affective Domain; David McKay: New York, NY, USA, 1964; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, C.; Sheard, C.; McPherson, A. A qualitative study to explore undergraduate medical students’ attitudes towards communication skills learning. Med. Teach. 2002, 24, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisetter, B.C.; Grussing, P.G. Students’ perceived satisfaction with and utility of pharmacy communications course work. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 1997, 61, 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Svensberg, K.; Sporrong, S.K.; Lupattelli, A.; Olsson, E.; Wallman, A.; Björnsdottir, I. Nordic Pharmacy Students’ Opinions of their Patient Communication Skills Training. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensberg, K.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Björnsdottir, I.; Sporrong, S.K. Factors associated with pharmacy students’ attitudes towards learning communication skills—A study among Nordic pharmacy students. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2017, 14, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlak, H.; Gemalmaz, A.; Gurel, F.S.; Dereboy, C.; Ertekin, K. Communication skills training: Effects on attitudes toward communication skills and empathic tendency. Educ. Health 2008, 21, 62. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sakran, T.M. Pharmacy Students’ Attitudes Towards Learning Communication Skills: The Case of the United Arab Emirates. AJHS 2015, 6, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hess, R.; Hagemeier, N.E.; Blackwelder, R.; Rose, D.; Ansari, N.; Branham, T. Teaching Communication Skills to Medical and Pharmacy Students Through a Blended Learning Course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, A.R.; Lyra, D.P., Jr.; Brito, G.C.; Balisa-Rocha, B.J.; Aguiar, P.M.; de Almeida Neto, A.C. Developing communication skills in pharmacy: A systematic review of the use of simulated patient methods. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 78, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, L.G.; Er, N.L. A systems approach to scaffold communication skills development. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning, Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- University of Southern Denmark. Odense. 2017. Available online: https://www.sdu.dk/da/om_sdu/dokumentation_tal/gennemsnit/odense (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- University of Copenhagen. Antal Optagne. Available online: https://studier.ku.dk/bachelor/ansoegning-og-optagelse/optagelsesstatistik/2017/antal-optagne/ (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- Department of Pharmacy. Pharmacy Internship (30 ECTS); University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Pharmacy. Information and Communication about Medicines (7,5 ECTS); University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 1995, 311, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibeck, V. Fokusgrupper, om Fokuserade Gruppintervjuer som Undersökningsmetod; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C.; McCartan, K. 11 Surveys and questionnaires. In Real World Research, A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 243–283. [Google Scholar]

- Traulsen, J.M.; Almarsdóttir, A.B.; Björnsdóttir, I. Interviewing the Moderator: An Ancillary Method to Focus Groups. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.E.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N. A Guide to Conducting Consensual Qualitative Research. Couns. Psychol. 1997, 25, 517–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, P.; Fairbairn, S.; Fletcher, C. Consultation skills of young doctors: I--Benefits of feedback training in interviewing as students persist. Br. Med. J. 1986, 292, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, R.P.; Bennett, M.S. Improving Communication Skills of Pharmacy Students Through Effective Precepting. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2006, 70, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, E.; McGee, H.M.; O’Boyle, C.A.; Shannon, W.; Bury, G.; Williams, A. Communication skills training in undergraduate medicine: Attitudes and attitude change. Ir. Med. J. 1992, 85, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yedidia, M.J.; Gillespie, C.C.; Kachur, E.; Schartz, M.D.; Ocken, J.; Chepaitis, A.E.; Snyder, C.W.; Lazare, A.; Lipkin, M.J. Effect of communications training on medical student performance. JAMA 2003, 290, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeier, N.E.; Hess, R.; Hagen, K.S.; Sorah, E.L. Impact of an Interprofessional Communication Course on Nursing, Medical, and Pharmacy Students’ Communication Skill Self-Efficacy Beliefs. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014, 78, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, N.; Anderson, C.; Avery, A.; Pilnick, A. Analysis of pharmacist–patient communication using the Calgary-Cambridge guide. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 83, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, A.; Latchford, G. Using motivational interviewing to improve medicines adherence. Pharm. J. 2016, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Students (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median | 24 |

| Range | 23–28 | |

| Gender | Women | 5 |

| Men | 10 | |

| Completed other education | Yes | 1 |

| No | 14 | |

| Completed elective communication course | Yes | 3 |

| No | 12 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duijm, N.P.; Svensberg, K.; Larsen, C.; Kälvemark Sporrong, S. A Qualitative Study on Danish Student Pharmacists’ Attitudes Towards and Experience of Communication Skills Training. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7020048

Duijm NP, Svensberg K, Larsen C, Kälvemark Sporrong S. A Qualitative Study on Danish Student Pharmacists’ Attitudes Towards and Experience of Communication Skills Training. Pharmacy. 2019; 7(2):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7020048

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuijm, Neeltje P., Karin Svensberg, Casper Larsen, and Sofia Kälvemark Sporrong. 2019. "A Qualitative Study on Danish Student Pharmacists’ Attitudes Towards and Experience of Communication Skills Training" Pharmacy 7, no. 2: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7020048

APA StyleDuijm, N. P., Svensberg, K., Larsen, C., & Kälvemark Sporrong, S. (2019). A Qualitative Study on Danish Student Pharmacists’ Attitudes Towards and Experience of Communication Skills Training. Pharmacy, 7(2), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7020048