Scoping Pharmacy Students’ Learning Outcomes: Where Do We Stand?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Studies Sources

2.2. Searched Keywords

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

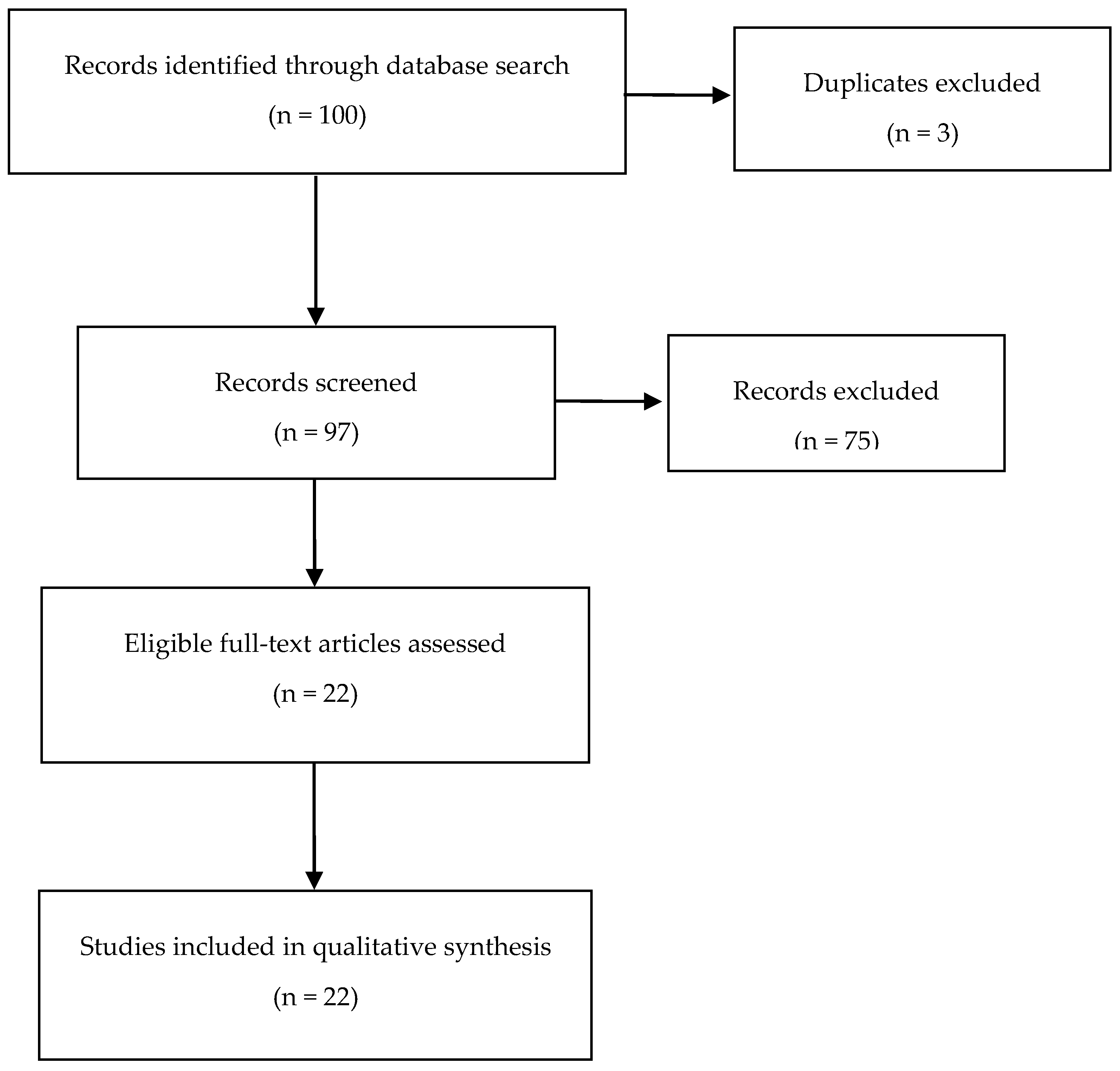

3.1. Selected and Excluded Studies

3.2. Brief Content Analysis of the Selected Studies

- Learning outcomes in real practice (n = 4);

- Learning and patients’ outcomes in real practice (n = 5);

- Learning outcomes using active strategies besides real practice (n = 5);

- Comparisons between different teaching pedagogies/models (n = 3);

- Pharmacy curriculum: design of new courses/topics (n = 2);

- Pharmacy residents as tutors (n = 1);

- Other evaluations (n = 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Real Practice

4.2. Active-Learning Strategies

4.3. Comparisons between Different Pedagogies and Teaching Models

4.4. Pharmacy Curriculum: Design of New Courses and Topics

4.5. Pharmacy Residents as Tutors, and Other Evaluations

4.6. Limitations of the Scoping Review

4.7. Practical Implications

4.8. Limitations of the Selected Studies, Future Research and Final Remarks

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ozdalga, E.; Ozdalga, A.; Ahuja, N. The Smartphone in Medicine: A Review of Current and Potential Use among Physicians and Students. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, B.; Spooner, J.J.; Tanzer, K.; Dintzner, M.R. Design and Implementation of a Professional Development Course Series. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81, 6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. FIP Education 2018: What Is Pharmacy Education? Available online: https://www.fip.org/pharmacy_education (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Nunes-da-Cunha, I.; Arguello, B.; Martinez, F.M.; Fernandez-Llimos, F. A Comparison of Patient-centered Care in Pharmacy Curriculum in the United States and Europe. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockman, K.; Haines, S.T.; McPherson, M.L. Improved Learning Outcomes After Flipping a Therapeutics Module: Results of a Controlled Trial. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, K.V.; Knetemann, M.; Madison, J. Putting Structure to Flipped Classrooms Using Team-Based Learnin. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2017, 29, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hargie, O. The Handbook of Communication Skills, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 9780415359115. [Google Scholar]

- Gonyeau, M.J.; DiVall, M.; Conley, M.P.; Lancaster, J. Integration of the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process (PPCP) into a Comprehensive Disease Management Course Series. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, J.; Nelson, M.; Slack, M.; Warholak, T. Outcomes of a Multi-faceted Educational Intervention to Increase Student Scholarship. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2015, 79, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, D.; Nugus, P.; Travaglia, J.; Braithwaite, J. Factors that Shape the Development of Interprofessional Improvement Initiatives in Health Organisations. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011, 20, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepler, C.D.; Strand, L.M. Opportunities and Responsibilities in Pharmaceutical Care. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 1990, 47, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farland, M.Z.; Feng, X.; Franks, A.S.; Sando, K.R.; Behar-Horenstein, LS. Pharmacy Resident Teaching and Learning Curriculum Program Outcomes: Student Performance and Quality Assessment. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungnickel, P.W.; Kelley, K.W.; Hammer, D.P.; Haines, S.T.; Marlowe, K.F. Addressing Competencies for the Future in the Professional Curriculum. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009, 73, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. Standards. 2016. Available online: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Svensberg, K.; Sporrong, S.K.; Lupattelli, A.; Olsson, E.; Wallman, A.; Björnsdottir, I. Nordic Pharmacy Students’ Opinions of their Patient Communication Skills Training. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ax, F.; Branstad, J.O.; Westerlund, T. Pharmacy Counseling Models: A Means to Improve Drug Use. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2010, 35, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatnawi, A.; Latif, D.A. A Qualitative Assessment of West Virginia Pharmacist Activities and Attitude in Diabetes Management. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 58–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawes, E.M.; Misita, C.; Burkhart, J.I.; McKnight, L.; Deyo, Z.M.; Lee, R.A.; Howard, C.; Eckel, S.F. Prescribing Pharmacists in the Ambulatory Care Setting: Experience at the University of North Carolina Medical Center. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2016, 73, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, S.J.; Kelley, K.A.; Ha, J.; Matsunami, M. Measuring PreAdvanced Practice Experience Outcomes as Part of a PharmD Capstone Experience. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014, 78, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fejzic, J.; Henderson, A.J.; Smith, N.A.; Mey, A. Community Pharmacy Experiential Placement: Comparison of Preceptor and Student Perspectives in an Australian Postgraduate Pharmacy Programme. Pharm. Educ. 2013, 13, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fejzic, J.; Barker, M. Implementing Simulated Learning Modules to Improve Students’ Pharmacy Practice Skills and Professionalism. Pharm. Pract. 2015, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. National Competency Standards Framework for Pharmacists in Australia; Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA): Canberra, Australia, 2016; ISBN 978-0-908185-03-0. Available online: https://www.psa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/National-Competency-Standards-Framework-for-Pharmacists-in-Australia-2016-PDF-2mb.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2018).

- Medina, M.S.; Plaza, C.M.; Stowe, C.D.; Robinson, E.T.; DeLander, G.; Beck, D.E.; Melchert, R.B.; Supernaw, R.B.; Roche, V.F.; Gleason, B.L.; Strong, M.N. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes 2013. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013, 77, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRISMA. Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Clarivate Analytics. Endnote Web. Available online: https://access.clarivate.com/login?app=endnote (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- PubMed. PubMed Help. 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK3827/#pubmedhelp.FAQs (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- SciELO. Database. Available online: http://www.scielo.org/php/index.php (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- DOAJ. Directory of Open Access Journals. Available online: https://doaj.org/ (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- ResearchGate. Database. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/about (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Cochrane Library. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/reviews (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Pharmacy at a Glance—2015–2017; International Pharmaceutical Federation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017; Available online: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/publications/2017-09-Pharmacy_at_a_Glance-2015-2017.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP); World Health Organization (WHO). Joint FIP/WHO Guidelines on Good Pharmacy Practice: Standards for Quality of Pharmacy Services. Available online: https://www.fip.org/www/uploads/database_file.php?id=331&table_id= (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Sanders, K.A.; McLaughlin, J.E.; Waldron, K.M.; Willoughby, I.; Pinelli, N.R. Educational Outcomes Associated with Early Immersion of Second-year Student Pharmacists into Direct Patient Care Roles in Health-system Practice. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, K.R.; King, S.T.; Barber, K.E. Impact of an Infectious Diseases Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience on Student Knowledge. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 1022–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, T.A.; Lau, C.; Sy, E.; Moogk, H.; Weber, S.S.; Danielson, J. Analysis of the Student Experience in an Attending Pharmacist Model General Medicine Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.W.; Huang, Y.M.; Lo, Y.H.; Chiung-Sheue, K.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.J.; Fang Ho, Y. Learning by Doing at Community Pharmacies: Objectives and Outcomes. J. Med. Educ. 2016, 20, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shrader, S.; Jernigan, S.; Nazir, N.; Zaudke, J. Determining the Impact of an Interprofessional Learning in Practice Model on Learners and Patients. J. Interprofessional Care 2018, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Cioltan, H.; Goldsmith, P.; Heasley, B.; Dermody, M.; Fain, M.; Mohler, J. An Assisted Living Interprofessional Education and Practice Geriatric Screening Clinic (IPEP-GSC): A Description and Evaluation. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2018, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gortney, J.S.; Moser, L.R.; Patel, P.; Raub, J.N. Clinical Outcomes of Student Pharmacist-Driven Medication Histories at an Academic Medical Center. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagelkerk, J.; Thompson, M.E.; Bouthillier, M.; Tompkins, A.; Baer, L.J.; Trytko, J.; Booth, A.; Stevens, A.; Groeneveld, K. Improving Outcomes in Adults with Diabetes through an Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Program. J. Interprofessional Care 2018, 32, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertig, R.; Ackerman, R.; Zagar, B.; Tart, S. Pharmacy Student Involvement in a Transition of Care Program. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.J.; Grundmann, O.; Li, R.M. The Development and Impact of Active Learning Strategies on Self-confidence in a Newly Designed First-year Self-care Pharmacy Course-outcomes and Experiences. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwin, J.; Greenwood, K.C.; Rico, J.; Nalliah, R.; DiVall, M. Interprofessional Curbside Consults to Develop Team Communication and Improve Student Achievement of Learning Outcomes. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017 81, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bamgbade, B.A.; Barner, J.C.; Ford, K.H. Evaluating the Impact of an Anti-stigma Intervention on Pharmacy Students’ Willingness to Counsel People Living with Mental Illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, Y.M.; Marshall, J.L. “It’s Like Rotations, but in the Classroom”: Creation of an Innovative Course to Prepare Students for Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivkin, A. Thinking Clinically from the Beginning: Early Introduction of the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleske, B.E.; Remington, T.L.; Wells, T.D.; Klein, K.C.; Tingen, J.M.; Dorsch, M.P. A Randomized Crossover Comparison between Team-Based Learning and Lecture Format on Long-Term Learning Outcomes. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalets, E.L.; Williams, C.; Park, I. Ten-year Experience with Student Pharmacist Research within a Health System and Education Center. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, J.; Fernandez, J.; Shah, D.; Williams, L.; Zagaar, M. Case-based Studies in Teaching Medicinal Chemistry in PharmD Curriculum: Perspectives of Students, Faculty, and Pharmacists from Academia. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirier, T.I.; Stamper-Carr, C.; Newman, K. A Course for Developing Interprofessional Skills in Pre-professional Honor Students Using Humanities and Media. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nduaguba, S.O.; Ford, K.H.; Bamgbade, B.; Iwuorie, O. Comparison of Pharmacy Students’ Knowledge and Self-efficacy to Provide Cessation Counseling for Hookah and Cigarette Use. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillette, C.; Rudolph, M.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Blough, E.R.; Sizemore, J.A.; Hao, J.; Booth, C.; Broedel-Zaugg, K.; Peterson, M.; Anderson, S.; et al. Predictors of Student Performance on the Pharmacy Curriculum Outcomes Assessment at a New School of Pharmacy Using Admissions and Demographic Data. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conselho Federal de Farmácia—Brasil. Dados 2016. Available online: http://www.cff.org.br/pagina.php?id=801&titulo=Boletins (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- Stuart, T.H.; Amy, L.P.; Brenda, L.G.; Melissa, S.M.; Stephen, N. Validation of the Entrustable Professional Activities for New Pharmacy Graduates. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2018, 1, 1922–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbur-Lopes, M.O.; Mesquita, A.R.; Silva, L.M.; De Almeida Neto, A.; Lyra Jr, D.P. Virtual Patients in Pharmacy Education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012, 76, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cláudio, A.P.; Carmo, M.B.; Pinto, V.; Cavaco, A.; Guerreiro, M.P. Virtual Humans for Training and Assessment of Self-medication Consultation Skills in Pharmacy Students. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 10th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCsE), Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK, 22–24 July 2015; pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Gillette, C.; Rudolph, M.; Kimble, C.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Smith, L.; Broedel-Zaugg, K. A Meta-Analysis of Outcomes Comparing Flipped Classroom and Lecture. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, M.; Meštrovic, A. Quality Assurance of Pharmacy Education: The FIP Global Framework; International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014; Available online: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/Quality_Assurance/QA_Framework_2nd_Edition_online_version.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- Walpola, R.L.; Fois, R.A.; McLachlan, A.J.; Chen, T.F. Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Peer-led Education Intervention to Improve the Patient Safety Attitudes of Junior Pharmacy Students: A Cross-sectional Study Using a Latent Growth Curve Modelling Approach. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e010045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, C.; Battistella, M.; Austin, Z. Implementation of a Near-peer Teaching Model in Pharmacy Education: Experiences and Challenges. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2012, 65, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.; Kirkpatrick, S. Narrative Interviewing. Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-TW&lr=&id=UQewQ4FzHowC&oi=fnd&pg=PA57&dq=Narrative+Interviewing&ots=laAXZaH0HH&sig=h8isx7T86O7bMs2fbtiIn7yRCd4&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Narrative%20Interviewing&f=false (accessed on 20 October 2018).

| Authors and Country | Year | Objective | Number of Students | Methods and Results | Main Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Learning outcomes in real practice | ||||

| Sanders et al. [34] USA | 2018 | To assess the educational impact of engaging second-year student pharmacists in active, direct patient care experiences in health system practice. | 28 | Setting: A skill-based four-week introductory pharmacy practice experience in health system practice. Main outcomes: Students were required to complete skills checklists in pre- and post-surveys. Operational and clinical self-efficacy statements were evaluated, e.g., performing proper aseptic technique to compound IV admixtures and gather pertinent patient information from the medical record, respectively. Students also self-identified contributions to patient care. Findings: Significant outcomes were achieved: 81.8% of operational and 100% of clinical self-efficacy statements (p < 0.05), and positive perceptions of the program. | Students’ skills were significantly enhanced. It is fundamental to assess data from the experiential education environment to further refine didactic curricula. |

| Stover et al. [35] USA | 2018 | To determine students’ knowledge acquisition during an infectious diseases (IDs) advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE). | 40 (5 control) | Setting: IDs consult service at a Level I trauma center and academic medical center. Pre- and post-test evaluations: multiple-choice examination, comprising 50 questions. Main outcomes: Control patients were not integrated in IDs consult. Experimental students were responsible for working with assigned patients daily. These students had access to patient-related pharmacotherapy discussions. Findings: Pre-test scores did not significantly differ between experimental and control students [61.7 (10.9) % versus 62.0 (5.1) %, respectively]. Post-test scores [80.2 (7.9) %] were significantly better than pre-test scores for both experimental and control students. | The IDs APPE improved student performance on a knowledge-based examination. This strategy may be incorporated into pharmacy curricula. Besides experimental education, infectious diseases concepts through coursework and active-learning exercises should be incorporated or strengthened in pharmacy courses. |

| O’Sullivan et al. [36] USA | 2017 | To characterize and determine the quality of students’ experience with an attending pharmacist model (APM). | 22 Year 1 and 29 Year 2 | Setting: Two general medicine services. Longitudinal study of 2 academic years: 2013–2014 (Year 1) and 2014–2015 (Year 2). Main outcomes: Qualitative information collected via in-depth interviews. Quantitative information about student learning and interprofessional interactions also collected. Findings: Strengths and areas needing improvement of APM were identified: some constraints were acknowledged by few students at one site, such as more delineation of expectations, initial support, and initial responsibility. | The APM model is suitable for providing a high-quality learning experience and qualitative results showed precisely the areas needing improvement. APM may be better than the traditional preceptor model for students’ integration in practice. Supervisors should evaluate students’ adaptation and provide educational programs at APM sites. |

| Tang et al. [37] China | 2016 | To study curricular effectiveness and impact on students of a community pharmacy experimental course. | 61 | Setting: 33 pharmacies (and 34 preceptors). Main outcomes: Pre- and post-evaluations of the Community Pharmacy Practice Experience (CPEE) preparatory course. The CPEE comprised the following learning domains: (i) community pharmacy basics; (ii) medications; (iii) dispensing practices; (iv) dietary supplements and health care products; (v) drug information and pharmacy informatics; (vi) pharmacy operation; (vii) pharmacy management; and (viii) off-site elective activities (180 h). A 22-statement, five-point scale questionnaire, was applied before and after the CPEE. Findings: 95.5% of the evaluated ability statements were significantly better self-perceived after the CPPE. | The CPPE was deemed appropriate for teaching community pharmacy practices at the mid-level stage students. It seems that a structured introductory-level CPPE course is valuable for students’ progression. Experimental learning should start from the time of admission. |

| 2. | Learning and patients’ outcomes in real practice | ||||

| Shrader et al. [38] USA | 2018 | To evaluate the impact on students of interprofessional learning using a practice model, as well as patient outcomes, in ambulatory care. | 382 students and 401 patients | Setting: Intervention period: 24-month ambulatory care; 179 students completed the survey instruments. A model was designed to relate students’ practice experience with an interprofessional education curriculum. Main outcomes: Patients’ clinical parameters and students’ professional activities indicators. Findings: Patients’ HbA1c was reduced by 0.5% and screening of depression improved by up to 91%. | Students reported a positive experience and acquired interprofessional collaboration skills. Students’ interventions improved patient clinical outcomes. |

| Lee et al. [39] USA | 2018 | To demonstrate the value of training interprofessional students in geriatrics and gerontology within an assisted living facility (elders’ residence). | 159 (2014–2015), and 270 (2015–2016) | Setting: Eight sessions on common aging conditions, chronic diseases, and geriatric syndromes (practice), once a month in multiple clinics. Students were placed in interprofessional teams with medicine, pharmacy, nursing and public health students (40% of pharmacy undergraduates); 3–4 students per team, following a minimum of two elders. Main outcomes: After each practice, students and patients were given a five-question Likert-scale survey. Students self-evaluated their communication, knowledge of elder-centered care, understanding of the importance of the clinical topic in delivering elder-centered care, observation of interprofessional collaboration or willingness to participate in future clinics. A similar survey was completed by elders. Findings: Students and patients’ self-evaluations were positively rated. | These practices led to increased perceived knowledge, and improved attitudes and perceptions among students. In addition, self-worth, self-care, and enjoyment increased among the elders. Real-world training in geriatrics and interprofessional team-care of older adults is vital. |

| Gortney et al. [40] USA | 2018 | To evaluate the impact of medication histories obtained by students on the identification of medication discrepancies and clinical outcomes. | 17 | Setting: A total of 215 patients’ medication histories were obtained by 17 students over a 12-month period (students interviewed 148 patients, other professionals interviewed 149 control patients, and both interviewed 67 patients). Main outcomes: Medication histories obtained by students as well as by other health providers were retrospectively compared between students and controls: discharge medication list and 30-day readmissions. Findings: In the period of 30 days after the interviews, there were fewer emergency visits in the student-interviewed group (8 vs. 18; p = 0.045). | Medication histories obtained by students improved the information available for identifying inpatients’ drug-related problems, the completeness of the discharge medication list, and reduced the occurrence of emergency department visits within 30 days. |

| Nagelkerk et al. [41] USA | 2018 | To improve the health of diabetic patients and practice efficiency within an interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP). | 25 students and 20 staff | Setting: The IPCP involved the completion of educational modules, addressing patient visits, responding to phone calls, team-based case presentations, medication reconciliation activities, and student-led group diabetes education classes. Staff and students agreed on providing consistent patient education during 1 year in a family practice setting. A mixed methods study design was followed. Main outcomes: Results from several tools were obtained, e.g., Interdisciplinary Education Perception Scale (IEPS), the Entry-level Interprofessional Questionnaire, the Collaborative Practice Assessment Tool, and pre/post module knowledge tests. Diabetic indicators were HgbA1c, glucose, lipid, body mass index, blood pressure, and information on annual dental, foot and eye examinations. Qualitative data from focus groups with staff and students were also gathered. Findings: Students and staff significantly improved their knowledge on Team Dynamics and Tips for Behavioral Changes knowledge. Only HgbA1c and glucose levels showed a significant decrease. Interprofessional perceptions were higher at the beginning and did not change throughout the study. | Patients’ outcomes improved in this family practice setting. In addition, students and staff benefited from this program. |

| Hertig et al. [42] USA | 2017 | To evaluate students’ performance in a Community Paramedic Program (CPP); assessing drug-related problems identified by students. | 11 students and 124 patients | Setting: CPP intended to improve the adaptation of hospitalized patients to home care. Besides pharmacists, 4th-year pharmacy students followed patients in one home visit during the 43-day study period. Main outcomes: Students’ interview data, after a previously assessed role-play. Drug-related problems and other issues with medication at home were identified in home visits. Students provided face-to-face information, and re-evaluated medicines. Findings: From 92 home interviews, 145 drug-related problems were identified, with the most frequent issue being on medicines usage, e.g., continuing hospital medication after discharge. Twenty-two and 25 drug-related problems were identified by students and pharmacists, respectively, in the 15 initial home visits. | Students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills were consolidated. This program may avoid hospital readmissions due to patients’ inadequate understanding of drug regime changes. |

| 3. | Learning outcomes using active strategies besides real practice | ||||

| Smith et al. [43] USA | 2018 | To determine the effectiveness of different active-learning exercises in a newly-designed flipped classroom self-care course; the effectiveness in applying the newly acquired knowledge and the improvement of self-confidence to recommend self-care treatments and counsel patients, were also assessed. | 208 pre-course and 197 post-course | Setting: Active-learning sessions using case scenarios for non-prescription and dietary supplements intake for 1st-year students. Main outcomes: Evaluation data from an anonymous students’ survey, administered pre- and post-course. A final and midterm exam was also applied. Findings: Students self-rated as significantly more confident to develop treatment plans or to counsel patients/family at end of course, although a low performance was registered at the final exam. | Active-learning sessions contributed to increase students’ self-confidence. |

| Kirwin et al. [44] USA | 2017 | To design and implement a series of activities focused on developing interprofessional communication skills; to assess the impact of the activities on students’ attitudes and the achievement of educational goals. | 130 | Setting: Pharmacy practice skills laboratory sessions. Prior to the first pharmacy practice skills laboratory session, a classroom lecture about team communication and short videos about roles/responsibilities/work environments concerning four types of health professionals were administered (registered nurses, physical therapists, nurse practitioners, and dentists). Four subsequent sessions, with role-play, involving a standardized health care professional who asked the students a medication-related question. Main outcomes: Besides students’ performance on the role-play, pre- and post-intervention surveys were administered. Findings: Students’ average scores in all sessions: 90% (SD = 57.4), and survey results showed better student attitudes concerning team-delivered care. | The role-play contributed to improve team communication. The activity was classified as valuable and realistic by students. Students need more exposure to team communication skills, since outcomes from the role-play were poor in some cases. |

| Bamgbade et al. [45] USA | 2017 | To evaluate the Willingness to Counsel (WtC) in diabetes, depression and schizophrenia | 88 | Setting: Third-year pharmacy undergraduates. The study intervention comprised presentations (e.g., on mental illness prevalence, signs and symptoms), videos, discussions and active-learning exercises. Pre- and post-intervention tests were applied. Main outcomes: Data from Link and Phelan’s framework, applied to evaluate the independent variable stigma, namely, comfortability (5 items relating to, or feeling comfortable around, a person with mental illness). Findings: WtC evaluations included medication-related favorable quotes such as “I am likely to screen for medication-related problems in patients with [disease state]”. In the pre-test, diabetes and schizophrenia achieved the highest and lowest WtC scores, respectively. Only the WtC of schizophrenia significantly improved in the post-test. WtC of diabetes was significantly higher than WTCs of depression and schizophrenia in the post-test. Regression results showed that comfortability was a predictor of WtC in both evaluated mental illnesses. | WtC may impact patients’ health; thus, pharmacy schools should support experiential education involving counseling, namely, on mental illnesses. |

| Hardy and Marshall [46] USA | 2017 | To discuss course development and results of a survey assessing students’ perceived confidence in performing various skills after course completion. | 69 (2010–2011) and 67 (2011–2012) | Setting: Third-year students from 2010 and 2012 were enrolled. All activities were carried out in a fictitious health system, using virtual patients. Twenty-two cases were used in the fall semester and 54 in the spring semester. Main outcomes: Data from a survey applied to evaluate students’ perceived confidence in clinical skills. Findings: Students’ confidence in their clinical skills was improved. Students’ knowledge on therapeutic principles and pharmacotherapeutic recommendations was reinforced. | Students were able to apply knowledge in simulated clinical settings, adding to an increase in their confidence in some of the topics. |

| Rivkin [47] USA | 2016 | To describe a student-centered teaching method used to introduce a pharmacist patient care process (PPCP). | 85 | Setting: A sample of first-year pharmacy students was selected to receive the PPCP. The PPCP was aimed at preparing students for taking medication history, learning to write Subjective Objective Assessment & Plan notes, and patients’ information and drug-related problems assessment. Examples were the “deconstruction” of a patient case or reorganization of patients’ story, as well as identifying a drug-related problem from the medication history. Main outcomes: Data from students’ evaluations comprising multiple-choice examinations, online course evaluations, and the assessment of students’ SOAP notes submissions. Findings: Mean exam question marks ranged from 3.7% to 18.8%, with sampled students’ performance significantly better than the comparative cohort. | Teaching methods were effective. Consistent and systematic delivery of the PPCP may improve students’ skills and confidence, offering a safety environment for introducing patient care into the pharmacy curriculum. |

| 4. | Comparisons between different teaching pedagogies/models | ||||

| Bleske et al. [48] USA | 2018 | To compare two different teaching methodologies, i.e., team-based learning with lecturing, evaluating the long-term learning outcomes. | 30 | Setting: Final-year pharmacy students taught in six therapeutic topics, with a sample split into 3 team-based learning groups and 3 traditional lectured groups. Main outcomes: Results from a 47-item questionnaire, six months after course completion. Findings: No statistically significant difference was found between the scores of students from the two different teaching methodologies. | No advantages were gained by employing team-based learning or lectures. |

| Michalets et al. [49] USA | 2018 | To compare two co-curricular models in relation to external dissemination rates and preceptor-classified impact on patient care. | 65 | Setting: The existing co-curricular model was compared to a new model: the longitudinal (12-month) advanced pharmacy practice experience (L-APPE). Among others, the L-APPE model included diverse courses on research didactics and training, and/or the utilization of a research catalogue and a research planning tool. Main outcomes: Patients’ data registered by students enrolled in the new model, as well as projects completion. Posters and peer-reviewed publications were also used as outcome measures. Data from students’ project preceptors gathered through an electronic survey on practice changes. Findings: Posters and peer-reviewed publications had a 350% higher occurrence (RR 4.5, 95% CI 1.9–10.9; p < 0.01). L-APPE projects were classified by preceptors 1.5 times more often, leading to a change or confirmation of a practice model or prescribing pattern (83.3% vs. 57.1%; p = 0.03). | Besides increasing external dissemination, L-APPE resulted in a more expressive practice model or prescribing pattern benefits. |

| Lockman et al. [5] USA | 2017 | To evaluate the impact on learning outcomes of flipping a pain management module. | 156 (2015) and 162 (2016) | Setting: First-professional-year (2015 and 2016) involved in a pain management module. The 2015 cohort used the normal model: (instructor-centered), while the 2016 cohort used the flipped model: (learner-centered). The flipped model was based on diverse pre-class activities and in-class active-learning exercises. Pre-class learning activities were ordered as follows: pre-recorded lectures, YouTube-style videos, online interactive modules, case-based guided learning questions, textbooks reading, guidelines reading, review articles reading, and clinical trials reading. Main outcomes: Data collected from both cohorts by two equal assessments at end-of-module, e.g., objective structured clinical examination and multiple-choice exam information. Findings: Learning outcomes significantly improved in the flipped model. | Students’ performance on knowledge- and skill-based assessments was significantly improved by a flipped model on pain management. |

| 5. | Pharmacy curriculum: design of new courses/topics | ||||

| Das et al. [50] USA | 2018 | To determine students’ perceptions regarding the importance of medicinal chemistry. | 112 (2017) and 99 (2016) | Setting: Prospective survey to evaluate the self-perceived impact of incorporating case-based studies in the medicinal chemistry syllabus. Students were asked: (i) how helpful the cases were to enhance interest in medicinal chemistry, and (ii) how positive was the influence of the basic-science knowledge, including their ability to apply the basic principles learned. Main outcomes: Data collected from the evaluation comprising dichotomous replies (yes/no) to the previous questions. Findings: 88% of students from the 2017 class and 92% from the 2016 class responded “yes”. | Demonstrating the connection between foundational medicinal chemistry and its application in pharmacy practice seemed positive. The syllabus can be redesigned, taking into consideration the enhancement of critical thinking and therapeutic decision-making skills through medicinal chemistry principles. |

| Poirier et al. [33] USA | 2017 | To design and implement an undergraduate course for pre-health professional students of pharmacy and senior undergraduate students from a variety of majors including pre-medical, pre-dental, nursing, exercise science, and the physical and biological sciences, using a variety of resources from the humanities. | 22 | Setting: Undergraduate course for pre-health professional students that used literature, films, and podcasts to promote students’ discussion. Focused topics were public health, stigmatization, portrayals of health care providers, patient experiences, health care ethics, aging, and death and dying. A quasi-experimental design was followed. Main outcomes: Data from tasks of reflective writings, a formal written and oral presentation on a selected health-related book, and data from pre- and post-course surveys. Findings: Students’ interpersonal skills improved, as well as their critical thinking, concerning different health care issues. | Humanities could excel in supporting indispensable patient care skill enhancement in students. |

| 6. | Pharmacy residents as tutors | ||||

| Farland et al. [12] USA | 2018 | To evaluate: (1) students’ performance on subjects taught by 1st and 2nd year postgraduate pharmacy residents (PR) and (2) the quality of the learning objectives and multiple-choice questions developed by the PR. | Students (n = 442): year 1 (n = 170); year 2 (n = 143) and year 3 (n = 129); pharmacy residents: 11 (responsible for content development) | Setting: Pharmacy students enrolled in the Medication Therapy Management course (2010 to 2012). Main outcomes: Data from students’ performance assessments through individual and team readiness assurance tests, and course examinations. The assessment of the quality of the learning objectives and multiple-choice questions written by PR followed pre-defined criteria by authors. Findings: Students performed heterogeneously across the evaluated areas. Twenty (42%) learning objectives and 73 (79%) of the multiple-choice questions met all the quality review criteria. | Impact of resident instructors on student course performance was not educationally significant. Students’ performance varied. Pharmacy residents should be taught to create quality learning objectives that help students to focus on learning the most important course content. |

| 7. | Other evaluations | ||||

| Nduagub et al. [51] USA | 2017 | To evaluate students’ self-efficacy to provide cessation counseling for cigarette and hookah tobacco. | 169 | Setting: Training session in the College of Pharmacy on cigarette (82%) and hookah smoking cessation (16%). Main outcomes: Data from an email survey comprising the confidence in counseling and perception of knowledge, based on the Ask–Advise–Assess–Assist–Arrange follow-up (5A’s) model. Findings: Students’ self-confidence in counseling and perception of knowledge was higher for smoking cessation than hookah tobacco. | Training in tobacco cessation is still desirable. Pharmacy students need further training to provide counseling on alternative tobacco products. |

| Gillette et al. [52] USA | 2016 | To characterize how independent variables predicted students’ performance on the Pharmacy Curriculum Outcomes Assessment (PCOA) during 1st to 3rd professional years. | Not described | Setting: All students at Marshall University School of Pharmacy participated in surveys, including the PCOA, a national examination used to measure the academic progress of pharmacy students. The PCOA is composed of 4 domains: basic biomedical sciences (16%); pharmaceutical sciences (30%); social, behavioral, and administrative sciences (22%); and clinical sciences (32%). Main outcomes: Data obtained from the Pharmacy College Admissions Test (PCAT), the Health Science Reasoning Test (HSRT), and the PCOA (as a target variable). Findings: PCAT, HSRT, and cumulative pharmacy grade point average were significant predictors of a higher PCOA. | Admission criteria and performance while studying pharmacy were associated with a higher score in PCOA. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pires, C.; Cavaco, A. Scoping Pharmacy Students’ Learning Outcomes: Where Do We Stand? Pharmacy 2019, 7, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010023

Pires C, Cavaco A. Scoping Pharmacy Students’ Learning Outcomes: Where Do We Stand? Pharmacy. 2019; 7(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010023

Chicago/Turabian StylePires, Carla, and Afonso Cavaco. 2019. "Scoping Pharmacy Students’ Learning Outcomes: Where Do We Stand?" Pharmacy 7, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010023

APA StylePires, C., & Cavaco, A. (2019). Scoping Pharmacy Students’ Learning Outcomes: Where Do We Stand? Pharmacy, 7(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010023