Abstract

The uninsured population has much to gain from affordable sources of prescription medications. No prior studies have assessed the prevalence and predictors of low-cost generic drug programs (LCGP) use in the uninsured population in the United States. A cross-sectional study was conducted using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) during 2007–2012 including individuals aged 18 and older who were uninsured for the entire 2-year period they were in MEPS. The proportions of LCGP fills and users was tracked each year and logistic regression was used to assess significant factors associated with LCGP use. A total of 8.3 million uninsured individuals were represented by the sample and 39.9% of these used an LCGP. Differences between users and non-users included higher age, gender, year of participation, and number of medications filled. The proportion of fills and users via LCGPs increased over the 2007–2012 study period. Healthcare providers, especially pharmacists, should make uninsured patients aware of this source of affordable medications.

1. Introduction

Individuals lacking medical insurance are disproportionately likely to suffer from negative health outcomes and barriers to health services than individuals with private or public insurance plans [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Prescription medications can offer a powerful first line of defense against conditions that commonly lead to costly in-patient hospital admissions, such as infections, heart disease and hypertension. However, despite their ability to ameliorate both chronic and acute illnesses, the high-cost of medications often serves as a barrier to access for uninsured individuals [7,8,9,10]. Low-cost generic drug programs (LCGPs) offered by major chain pharmacies improve both the affordability and accessibility of medications that may be used to treat many common acute and chronic conditions [11,12].

LCGPs first appeared in the United States (U.S.) in mid-2006 with Kmart providing 90 days of certain generics for $15 and was shortly followed by Wal-Mart’s $4 program [13]. Since then, generic discount programs are now in place at almost all major pharmacy chains including 8 of the top 10 largest chain pharmacies in the nation and include one-third of the top 100 generics used by Americans by volume [11,13,14]. These programs include a wide variety of medication categories—cardiovascular, antibiotics, asthma, analgesics, anti-diabetes, mental health, men’s health, and women’s health, among others [15,16,17].

Poor and uninsured individuals arguably have the most to gain from the increased affordability and accessibility offered by LCGPs. Despite the tremendous impact that LCGPs may have on the uninsured population in the U.S., there is a relative dearth of literature assessing the prevalence of LCGP use in a nationally representative uninsured population. In 2008, over 70 million Americans were estimated to have used an LCGP to obtain a prescription medication—a figure that has likely expanded as the number and popularity of these programs has increased [13,17,18]. In this 2008 self-reported survey, one-third of adults and one-quarter of children without insurance coverage reported using these programs [18]. However, given that self-reported surveys are particularly prone to recall and selection bias it is difficult to ascertain whether these estimates accurately represent LCGP use in the uninsured population.

Few studies have assessed the demographic and clinical characteristics of LCGP users and non-users [19,20] and none to our knowledge have assessed LCGP use specifically in an uninsured population. Understanding the factors that influence which individuals currently utilize these programs is a crucial first-step in increasing use amongst patients that have the most to gain from LCGPs. This study had four objectives: (1) Assess the prevalence of LCGP use in a nationally representative uninsured population; (2) Compare demographic and clinical characteristics of LCGP users and non-users; (3) Determine significant predictors of LCGP use; and (4) Analyze trends in LCGP use amongst uninsured individuals from 2007–2012.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

This study utilized public use data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) for the years 2007–2012. MEPS is a nationally representative survey of civilian, non-institutionalized individuals in the U.S. and includes information on demographics, healthcare utilization, medical conditions, and prescription medication use. MEPS uses an overlapping panel design with a new cohort (“panel”) added each year and participating in the survey for up to two years. Data are collected in five rounds throughout a panel’s two years of participation. Survey sampling and response weights are included so that population estimates may be obtained.

2.2. Study Subjects and Design

A cross-sectional study design was used to compare differences between LCGP users and non-users. Rates of LCGP use from 2007–2012 were quantified to assess trends in the proportions of LCGP fills and LCGP users over these years. These years were chosen because 2007 was the first full year in which LCGPs were available and 2012 is the most recent year of data available from MEPS. Inclusion in the study cohort required that individuals lack medical and pharmacy health insurance for both years of their MEPS panel, had no third party payers in the MEPS pharmacy component, participated in all five rounds of data collection, and reported using at least one prescription medication during their two-year panel period. The final sample was representative of those who are “long-term uninsured” (i.e., ≥2 years) who have filled a prescription.

2.3. Use of Low-Cost Generic Programs

MEPS captures medication fills at the pharmacy level; thus effectively capturing all medication fills paid by cash. Survey participants are first asked in-person about all medications which are have been filled. Surveyors obtain pharmacy information from prescription bottles and receive permission to contact the pharmacies for more information. Once permission is granted, details regarding each fill for each medication are extracted including name, NDC number, and the amounts paid by the customer or any third parties.

Four stipulations were used to define LCGP use: (1) The total cost of the drug was paid out of pocket; (2) The cost of the drug exactly matched the cost of an LCGP drug as reported by pharmacies; (3) The medication was listed on an LCGP formulary from a major chain pharmacy from 2007–2012; and (4) Oral medication fills were dispensed for 30 or 90 day supplies of medications, with the exception of anti-infectives, contraceptives, and steroids which were allowed to vary given differential dosing intervals for these classes. LCGP use was coded at the person level as a binary dependent variable for any use during the study period and at the medication level for each medication fill. Pharmaceutical utilization was determined for medications available from LCGPs based on Multum Lexicon classifications (Cerner Multum™, Denver, CO, USA), which is included in the MEPS pharmacy files for each medication.

2.4. Subject Characteristics

Cohort demographics and characteristics of interest included age, race, gender, family income level, number of prescriptions filled. For comparison, the cohort was divided by age categories: 0–17, 18–34, 35–54, 55–64, and 65+ years of age. Family income level was based on MEPS classifications of income levels which are stratified as a percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL): <100%, 100%–125%, 126%–200%, 201%–400%, and >400% of the FPL. Residence within a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) was recorded as a binary variable and region was categorized by U.S. Census regions. Race was divided between Whites, Hispanics, African-Americans, Asians, and others. Age, family income, region, MSA and insurance type were all assessed at the last round of data collection. A Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score was calculated for each individual based on the algorithm by Quan et al. [19].

2.5. Data Analysis

The proportions of LCGP uses and users were tracked from 2007 to 2012. These proportions were compared to overall pharmaceutical utilization for users and non-users over the same time period. Comparisons were conducted for cohort characteristics of interest between users and non-users using chi-square or t-tests. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with LCGP use. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals were reported. All data analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 [21] (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) implementing SAS procedures (SURVEYMEANS, SURVEYFREQ, and SURVEYLOGISTIC) that take into account the complex survey design of MEPS and use the longitudinal survey weights supplied by MEPS to calculate population estimates over the two-year period. This manuscript was drafted in accordance with STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Comparison

Over the years 2007–2012 a total of 2535 uninsured individuals met all inclusion criteria. Applying MEPS person weights, this population represents 8,327,690 uninsured individuals annually who filled a prescription medication—representing approximately one fourth of the U.S. uninsured population prior to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Of this population, 39.9% (N = 3,321,071) were classified as LCGP users, having filled at least one prescription through an LCGP during their two-year panel period.

Demographic and clinical comparisons between users and non-users are presented in Table 1. Significant differences between LCGP users and non-users existed in terms of age, sex, MEPS panel, number of medications filled, and number of unique medications used. LCGP users were significantly more likely to be aged 55 or greater than LCGP non-users (19.1% vs. 10.4%). Additionally, a significantly greater proportion of LCGP users were female than non-users (55.6% vs. 44.7%). In terms of the number of medications used, LCGP users filled significantly more unique prescriptions and had more total medication fills than non-users.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study cohort.

3.2. Predictors of LCGP Use

The full multivariable logistic regression model with adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals is presented in Table 2. Significant predictors of LCGP use included MEPS panel number and number of unique medications used. Participants in Panels 13–16—taking place from 2008–2012—had greater than double the odds of using an LCGP than individuals in panel 12 (2007–2008). The panel with the greatest odds of using LCGPs was observed to be panel 15 (2010–2011) with individuals in this panel being greater than four times more likely to use an LCGP than those in panel 12 (AOR: 4.02 (95% CI: 2.75–5.87)). Additionally, each unique medication used increased the odds of LCGP use by 43% (AOR: 1.43 (95% CI: 1.27–1.62)).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression results of predictive characteristics for LCGP use.

3.3. Medication Use

From 2007–2012 the study population filled a total of 20,143 prescriptions, with 81.7% of these prescriptions being available through LCGPs. Out of all medications available through LCGPs, only 34.7% were actually purchased through these programs. The majority of LCGP fills were for medications used to treat chronic conditions.

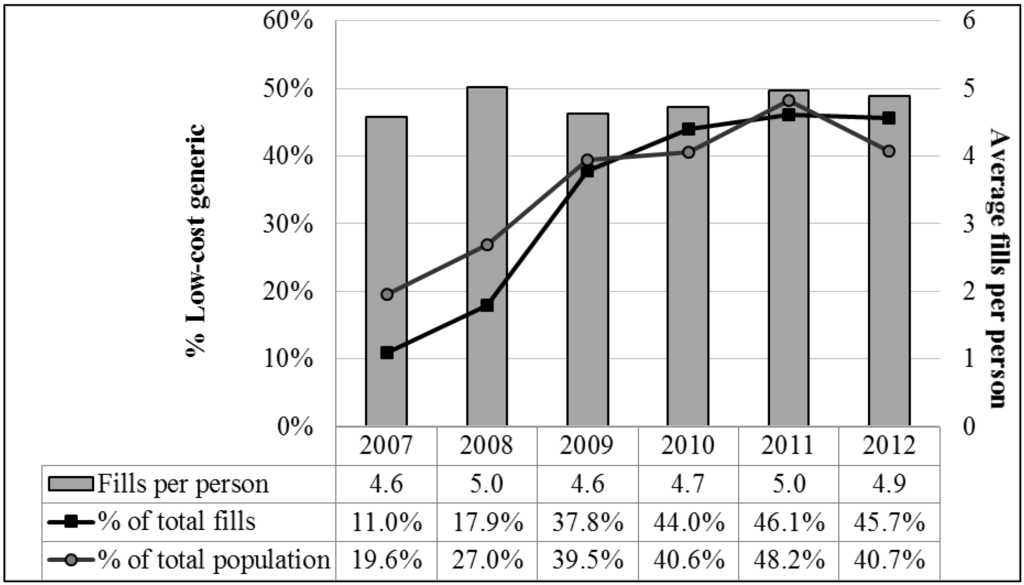

Trends in the use of LCGPs, including the proportions of LCGP fills and LCGP users in each year as well as the total number of prescription fills per person are presented in Figure 1. Proportions of both LCGP users and LCGP fills in each year increased significantly from 2007–2012. The proportion of prescriptions available through LCGPs that were obtained through LCGPs more than quadrupled from 11.0% in 2007 to 45.7% in 2012. Over the same time period, the proportion of LCGP users more than doubled from 19.6% in 2007 to 40.7% in 2012. While the proportions of LCGP users and LCGP fills both increased significantly from 2007–2012, overall pharmaceutical utilization remained relatively constant with approximately 4.8 prescription fills per person per year.

Figure 1.

Proportion of LCGP fills, LCGP users, and total average prescription fills per person during the study period.

4. Discussion

Individuals living for long periods of time without insurance have the most to gain from the affordable medications offered by LCGPs—especially so for those also suffering from chronic illness or living below the poverty line. Results of this study indicate that the increasing use of LCGPs in the uninsured population is not due to increasing pharmaceutical utilization but rather due to increasing popularity and knowledge of these programs. However, despite the dramatic increase in LCGP use amongst the uninsured, it is disconcerting that fewer than 40% of uninsured individuals in the U.S. who use prescription medications are LCGP users. These numbers are comparable to insured adults and lower than elderly adults with Medicare [20]. Even when only considering individuals who filled at least one prescription available through LCGPs less than half actually filled that medication through an LCGP.

Uninsured individuals who are living below the federal poverty threshold are disproportionately likely to experience cost of prescription drugs as an impediment to medication access. One would hope that individuals living below the federal poverty level would use LCGPs at a greater rate than individuals better off financially. However, no significant differences were observed regarding the income distribution of LCGP users and non-users and income level was not a significant predictor of LCGP use. Taken together these results indicate that income and specifically poverty are not significant drivers of LCGP utilization.

The self-administered questionnaire in the MEPS household component includes questions regarding whether or not the participant experienced delays in getting necessary prescription medications, and if so, what the cause of the delay was. Given the widespread availability and relative affordability of LCGPs, one might expect that LCGP users would be less likely to experience delays in obtaining necessary medications. Our study found that there is not a significant difference between the number of LCGP users and non-users experiencing delays in obtaining prescription medications; nor do delays in obtaining medications make individuals significantly more or less likely to use LCGPs. Additionally, only 53.5% of individuals who reported cost of medication as the reason for a delay in obtaining medication were classified as LCGP users. Both of these results imply that LCGPs are not adequately being used to prevent delays in obtaining medication, particularly where cost is a prohibitive factor.

Many state and community public health service organizations supply prescription savings cards to uninsured individuals or include outreach programs to supply medications to the needy. These outreach services are a tacit reflection that public health entities understand the benefits of alleviating cost of medications as a barrier to medication access. In addition to these discount cards, public health entities should also actively promote the use of LCGPs and attempt to improve health literacy regarding the comparative efficacy of generic pharmaceutical products. Since many public health organizations already maintain online instructions regarding how to obtain prescription drug assistance, they can also include information about the widespread availability of LCGPs at little to no cost for the organization. Furthermore, prescribers as well as major chain pharmacies should take more of an active role in encouraging the use of LCGPs to treat common chronic and acute illnesses. These programs are being widely used by the rest of the population [20,22] and the implications of their use have been discussed elsewhere [11].

Given the recent expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, many of the uninsured individuals included in this study will now be eligible for Medicaid benefits. Although these individuals will now receive prescription drug benefits through Medicaid plans, it is still vitally important to encourage LCGP use in this newly insured population. Previous research has demonstrated that individuals who are uninsured for long periods and subsequently gain insurance will dramatically increase their healthcare utilization and spending once they become insured [23,24,25]. Newly insured individuals under the Affordable Care Act should be encouraged to use LCGPs to decrease the barrier to effective pharmaceutical intervention where cost may still be a limitation even with insurance. This also has the potential to be cost saving for state and federal payers by offsetting the costs of prescription medications as well as decreasing clinical sequelae of conditions which the medications are meant to treat. Also, given the ongoing challenges to the Affordable Care Act, if it were to be totally dismantled, it would be very beneficial for the newly uninsured population to understand that affordable medications are available even without insurance coverage.

Our study is subject to some limitations. It may remain possible that not all medication use is recorded if all pharmacies used were not surveyed. Our study definition of LCGP use may allow for overestimation of use if only pricing is considered. However, this effect is mitigated by requiring specific quantities supplied for oral medications. Our algorithm passed face validity by not detecting medications that are not on LCGP formularies (e.g., benzodiazepines and narcotics) and also included estimates of generic use close to other estimates using surrogate markers of medication use (e.g., 10% of warfarin fills) [20,26]. We included a population representative of those who are uninsured for at least two continuous years and that have filled a prescription medication. Given the data source, we cannot verify the presence of unfilled medications in the population or account for those included in MEPS that did not report at least one medication fill. Finally, it is possible that some individuals exclusively use pharmacies in which LCGPs are not available and thus this population was never eligible for inclusion in the LCGP user cohort.

5. Conclusions

A significant proportion of individuals who were uninsured for two consecutive years from 2007–2012 used an LCGP during this period. Furthermore, the proportion of LCGP users and the proportions of LCGP fills out of all medications available through LCGPs both increased significantly from 2007–2012. Despite the tremendous gains in the rate of LCGP use, certain subgroups including individuals living below the poverty threshold and those experiencing delays in obtaining necessary medications could stand to benefit from greater use of these programs. State and community public health services should work alongside prescribers and major pharmacy chains to encourage greater use of LCGPs among the uninsured population.

Acknowledgments

No funds were used for the conduct of this study.

Author Contributions

Joshua D. Brown conceived and designed the study. Nathan J. Pauly performed the data analysis. All authors interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| FPL | Federal poverty limit |

| LCGP | Low-Cost generic program |

| LD | linear dichroism |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MEPS | Medical Expenditure Panel Survey |

| MSA | Metropolitan Statistical Area |

| NDC | National Drug Code |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| U.S. | United States |

References

- Ayanian, J.Z.; Weissman, J.S.; Schneider, E.C.; Ginsburg, J.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA 2000, 284, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadley, J. Sicker and poorer—The consequences of being uninsured: A review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care use, health, work, and income. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2003, 60 (Suppl. S2), 3S–75S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.W.; Sudano, J.J.; Albert, J.M.; Borawski, E.A.; Dor, A. Lack of health insurance and decline in overall health in late middle age. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, P.A.; Penman-Aguilar, A.; Campbell, V.A.; Graffunder, C.; O’Connor, A.E.; Yoon, P.W. Conclusion and future directions: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2013, 62 (Suppl. S3), 184–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sabik, L.M.; Dahman, B.A. Trends in care for uninsured adults and disparities in care by insurance status. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2012, 69, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Hui, X.; Schneider, E.B.; Ali, M.T.; Canner, J.K.; Leeper, W.R.; Efron, D.T.; Haut, E.R.; Velopulos, C.G.; Pawlik, T.M.; et al. Worse outcomes among uninsured general surgery patients: Does the need for an emergency operation explain these disparities? Surgery 2014, 156, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisler, M.; Wagner, T.H.; Piette, J.D. Patient strategies to cope with high prescription medication costs: Who is cutting back on necessities, increasing debt, or underusing medications? J. Behav. Med. 2005, 28, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, T.H.; Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D. Prescription drug co-payments and cost-related medication underuse. Health Econ. Policy Law 2008, 3, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felland, L.E.; Reschovsky, J.D. More nonelderly Americans face problems affording prescription drugs. Track Rep. 2009, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pelaez, S.; Lamontagne, A.J.; Collin, J.; Gauthier, A.; Grad, R.M.; Blais, L.; Lavoie, K.L.; Bacon, S.L.; Ernst, P.; Guay, L.; et al. Patients’ perspective of barriers and facilitators to taking long-term controller medication for asthma: A novel taxonomy. BMC Pulm. Med. 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, N.K.; Shrank, W.H. Four-dollar generics—Increased accessibility, impaired quality assurance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1885–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrank, W.H.; Liberman, J.N.; Fischer, M.A.; Girdish, C.; Brennan, T.A.; Choudhry, N.K. Physician perceptions about generic drugs. Ann. Pharmacother. 2011, 45, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czechowski, J.L.; Tjia, J.; Triller, D.M. Deeply discounted medications: Implications of generic prescription drug wars. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2010, 50, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.K.; Dwibedi, N.D.; Omojasola, A.; Sansgiry, S.S. Impact of Generic Drug Discount Programs on Managed Care Organizations. Am. J. Pharm. Benefits 2011, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. $4 Generics. Available online: http://i.walmartimages.com/i/if/hmp/fusion/customer_list.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2015).

- Walgreens Co. Value-Priced Medication List. Available online: http://www.walgreens.com/images/psc/VPG_List_Update_7-25-2014.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2015).

- Rucker, N.L. $4 generics: How low, how broad, and why patient engagement is priceless. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2010, 50, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital: National Poll on Children’s Health. Nearly 70 Million Americans Using Discount Generic Rx Programs. 2008. Available online: http://mottnpch.org/reports-surveys/nearly-70-million-americans-using-discount-generic-rx-programs.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2015).

- Quan, H.; Sundararajan, V.; Halfon, P.; Fong, A.; Burnand, B.; Luthi, J.C.; Saunders, L.D.; Beck, C.A.; Feasby, T.E.; Ghali, W.A. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care 2005, 43, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauly, N.J.; Talbert, J.C.; Brown, J.D. The Prevalence and Predictors of Low-Cost Generic Program Use in the Pediatric Population. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2015, 2, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS, version 9.4; statistical software; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2013.

- Pauly, N.J.; Brown, J.D. Prevalence of Low-Cost Generic Program Use in a Nationally Representative Cohort of Privately Insured Adults. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2015, 21, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, J.D.; Kadiyala, S.; Bell, J.F.; Martin, D.P. The causal effect of health insurance on utilization and outcomes in adults: A systematic review of US studies. Med. Care 2008, 46, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baicker, K.; Chernew, M.E.; Robbins, J.A. The spillover effects of Medicare managed care: Medicare Advantage and hospital utilization. J. Health Econ. 2013, 32, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWilliams, J.M.; Meara, E.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Ayanian, J.Z. Use of health services by previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauffenburger, J.C.; Balasubramanian, A.; Farley, J.F.; Critchlow, C.W.; O’Malley, C.D.; Roth, M.T.; Pate, V.; Brookhart, M.A. Completeness of prescription information in US commercial claims databases. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2013, 22, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).