The Production of a Framework of Competences for Pharmacy Practice in the European Union

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Elaboration of the List of Competences

- Medical doctors by MEDINE.

- Dentists by ADEE [8]; the Association for Dental Education in Europe (ADEE) was founded in 1975 as an independent European organisation representing academic dentistry and the community of dental educators (from their website).

- Community pharmacists in SW England [9]. The Competency Development and Evaluation Group (CoDEG) is a collaborative network of specialist and academic pharmacists, developers, researchers and practitioners. Its aim is to undertake research and evaluation in order to help develop and support pharmacy practitioners and ensure their fitness to practice at all levels. Among its key outputs are the General Level Framework and the Advanced Level Framework (from their website).

- (I)

- Domain “Patient Care Competences”, subdivided into 9 major competences:

- (1)

- Patient consultation

- (2)

- Need for the drug

- (3)

- Promote health, engage with the population on health issues and work effectively in a healthcare system

- (4)

- Selection of drug

- (5)

- Drug specific issues

- (6)

- Provision of drug product

- (7)

- Medicines information and patient education

- (8)

- Monitoring drug therapy

- (9)

- Evaluation of outcomes

- (II)

- Domain “Personal Competences” subdivided into 10 major competences:

- (10)

- Organisation

- (11)

- Effective communication skills both orally and in writing

- (12)

- Teamwork

- (13)

- Professionalism

- (14)

- Learning and knowledge

- (15)

- The global pharmacist

- (16)

- Problem-solving knowledge

- (17)

- Problem solving; effective use of information and information technology

- (18)

- Providing information

- (19)

- Follow-up

- (III)

- Management and Organization Competences” subdivided into 8 major competences:

- (20)

- Clinical governance

- (21)

- Service provision

- (22)

- Budget setting and reimbursement

- (23)

- Organisation

- (24)

- Training

- (25)

- Staff management

- (26)

- Procurement (medicines purchasing)

- (27)

- Drug product-process development and manufacture

- (1)

- Capacity to learn, including continuous professional development;

- (2)

- Ability to teach others;

- (3)

- Analysis: ability to apply logic to problem solving, evaluating pros and cons and following up on the solution found;

- (4)

- Synthesis: capacity to gather relevant knowledge and summarise the key points;

- (5)

- Capacity to evaluate scientific data in line with current scientific and technological progress;

- (6)

- Ability to interpret pre-clinical and clinical evidence-based medical science and apply the knowledge to pharmaceutical practice;

- (7)

- Skills in scientific and biomedical research.

- (1)

- Not important

- (2)

- Quite important

- (3)

- Very important

- (4)

- Essential

2.2. Statistical Analysis

- (1)

- Descriptive statistics

- i.

- Parametric: means and standard deviations

- ii.

- Non-parametric: medians with 25 and 75% percentiles

- (2)

- Tests of normality of distribution:

- i.

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov

- ii.

- Skewness

- iii.

- Kurtosis

- (3)

- Comparisons

- i.

- Non-parametric

- Kruskal–Wallis

- Wilcoxon signed rank test

3. Results

3.1. Panel Members

| Panel member | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% percentile | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| Median | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

| 75% percentile | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Mean | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

| Standard deviation | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.75 |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) distance | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.45 |

| p value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Passed K-S normality test | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Skewness | −0.31 | −0.62 | −0.46 | −0.69 | −0.71 | −0.70 | −1.8 |

| Kurtosis | −0.91 | −0.47 | −0.52 | −0.51 | 0.44 | −0.63 | 2.0 |

3.2. Major Competences

| Rank | Major competence | Domain-number | Med | Mean | SD | CV% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Selection of drug | PCC-1.4 | 4 | 3.9 | 0.095 | 2 |

| 2 | Providing information | PC-2.18 | 4 | 3.8 | 0.38 | 10 |

| 4 | Problem solving: effective use of information and information technology | PC-2.17 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 0.31 | 9 |

| 5 | Need for the drug | PCC-1.2 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 0.43 | 12 |

| 8 | Provision of drug product | PCC-1.6 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.53 | 15 |

| 3 | Drug specific issues | PCC-1.5 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 0.23 | 6 |

| 9 | Effective communication skills both orally and in writing | PC-2.11 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 0.67 | 20 |

| 7 | Procurement (medicines purchasing) | MOC-3.26 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 0.53 | 16 |

| 6 | Medicines information and patient education | PCC-1.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.37 | 16 |

| 12 | Problem-solving knowledge | PC-2.16 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.2 | 6 |

| 14 | Professionalism | PC-2.13 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.13 | 4 |

| 10 | Monitoring drug therapy | PCC-1.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 0.38 | 12 |

| 11 | Follow-up | PC-2.19 | 3 | 3.3 | 0.52 | 15 |

| 13 | Training | MOC-3.24 | 3 | 3.3 | 0.57 | 17 |

| 15 | Learning and knowledge | PC-3.24 | 3 | 3.2 | 0.39 | 12 |

| 16 | Patient consultation | PCC-1.1 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 0.57 | 18 |

| 17 | Promote health, engage with population on health issues and work effectively in a health care system | PCC-1.3 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.43 | 14 |

| 18 | Drug product-process development and manufacture | MOC-3.27 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | Clinical governance | MOC-3.21 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.41 | 14 |

| 19 | Organisation | MOC-3.23 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.55 | 19 |

| 21 | Teamwork | PC-2.12 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.46 | 16 |

| 23 | The global pharmacist | PC-2.15 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.54 | 20 |

| 24 | Staff management | MOC-3.25 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.39 | 15 |

| 22 | Evaluation of outcomes | PCC-1.9 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.38 | 14 |

| 25 | Organisation | PC-2.10 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 13 |

| 26 | Service provision | MOC-3.21 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 0.72 | 34 |

| 27 | Budget setting and reimbursement | MOC-3.22 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.51 | 35 |

3.3. Ranking Data for All Competences

| Rank | Lowest | Lowest | Lowest | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competence | Describes the key drivers for national and local service development | Claims reimbursement appropriately for services provided | Ensures the prescriber’s intentions are clear | Ensures appropriate timing of dose | Supplies information on documents | Accesses information from appropriate sources | Demonstrates ability to describe the mechanisms of interactions | Provides information that is appropriate to the recipient’s needs | Establishes the priority of information provision when it is needed |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Maximum | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 25% percentile | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 75% percentile | 3 | 2.5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Standard deviation | 0.82 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| Coefficient of variation | 40.82% | 54.77% | 47.14% | 9.80% | 9.80% | 9.80% | 9.80% | 9.80% | 9.80% |

| K-S distance | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| p value | 0.2 | 0.0359 | 0.0192 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Deviation from normality | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| W value | 15 | 10 | 15 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Sum of + ranks | 15 | 10 | 15 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Sum of − ranks | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p value | 0.0625 | 0.125 | 0.0625 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 |

| Skewness | 0 | 1.4 | −0.99 | −2.6 | −2.6 | −2.6 | −2.6 | −2.6 | −2.6 |

| Kurtosis | −1.2 | 2.5 | −1.2 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Likert Scales

4.2. Statistical Analysis of the Rankings

- (1)

- There is a lack of sphericity: the variances of the differences between all possible pairs of rankings are not equal. The difference between Rank 1 (not important) and 2 (quite important) is not the same as between 3 (very important) and 4 (essential).

- (2)

- Data are discrete rather than continuous variables: rankings cannot take on any value between two specified values.

- (3)

- Data are skewed to higher ranking values. They do not follow any pre-specified distribution; some data even show an inverse bell-shaped form. In spite of this, there is a significant correlation between median and mean in several cases. This generally implies the normality of data, but in this case is probably affected by the small number of observations. Finally, it should be noted that there is a wide spread in values for the coefficient of variation.

- (1)

- Descriptive statistics: reduce and summarize complex data to a few comprehensible variables without losing any of the original information. In this case, parametric statistics (means and standard deviations, coefficient of variation, etc.) are more useful, as they are more precise.

- (2)

- Decisional statistics: reveal the statistical importance of such variables while taking into account errors from known or unknown disturbing influences. In this case, non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon signed rank, Kruskal-Wallis, etc.) are more appropriate in the case of non-continuous variables, such as ranks, although parametric tests (analysis of variance, etc.) do show a certain robustness [13]. It should be noted that in the Wilcoxon comparison of the ranks observed with a theoretical rank of “1” (= not important), the test is affected by the fact that the sum of negative ranks = 0. This arises because there are no observed ranks <1. As Likert ranks are integral, a rank <1 would be equal to “0”, and this would bring in a binary scale of an “important/not important” nature. This is against the philosophy behind the Likert scale, which is used to create nuance in a questionnaire (not important, quite important, very important, essential) and so goes beyond a binary scale.

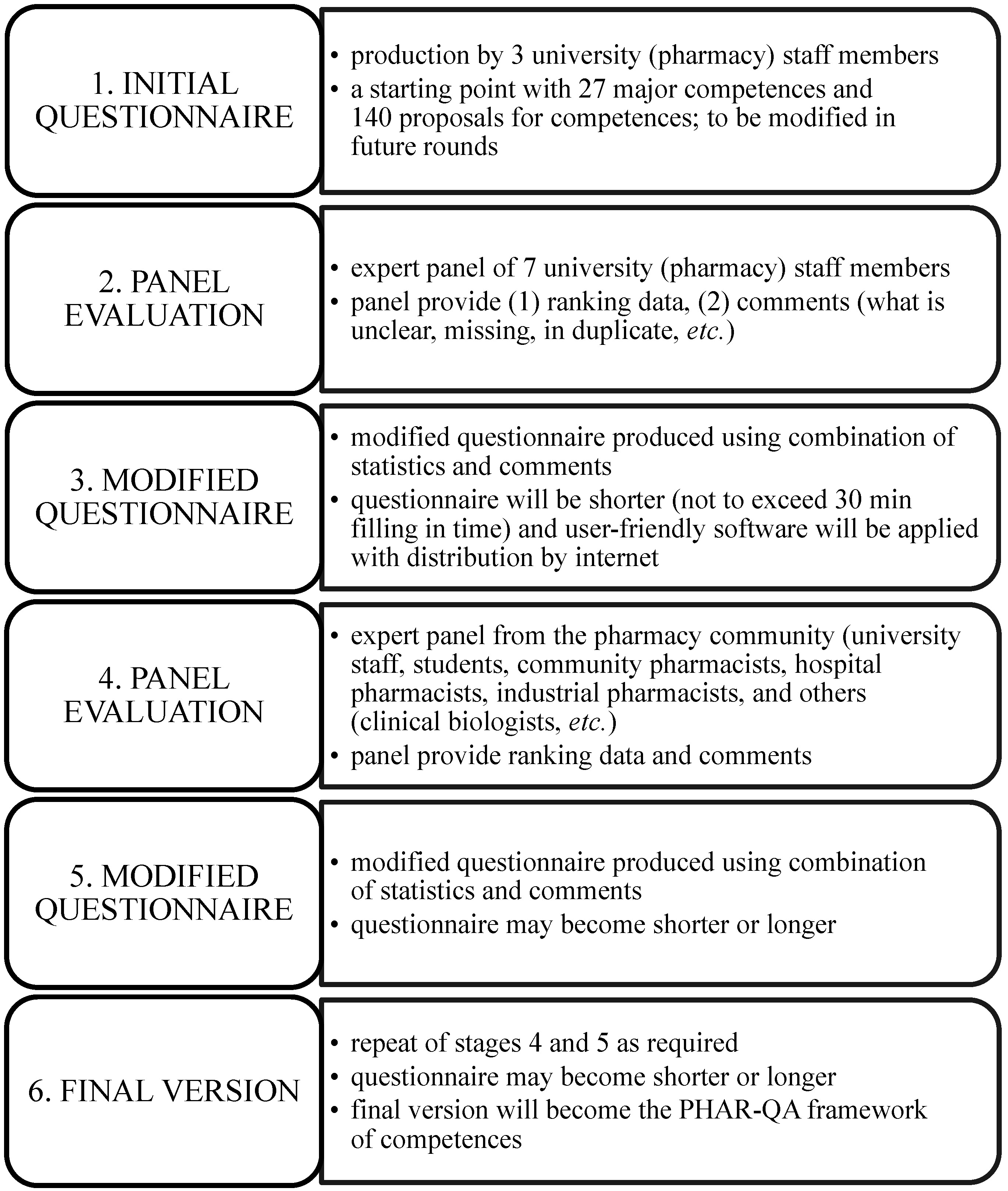

4.3. The Modified Delphi Process and the Rankings of the Proposals (Figure 1)

- (1)

- It is a two-stage process with the first university staff panel producing a questionnaire that is run through a wider pharmacy community panel at a second stage. This will “even out” discrepancies between the different actors. Thus, for instance, several university staff members gave a low rank to management and organization competences (although there was wide variability on some of these points). It may be that active pharmacists will give such competences a higher rank. The process will ensure that the final framework is universally accepted.

- (2)

- The initial suggested framework is only a starting point: it may be modified by suggestions to remove or add competences as the process evolves. In the initial stages, it was realised that some competences were duplicates (e.g., major Competences 16 and 17); other competences were not described with sufficient clarity. There have also been changes in the organisation of the questionnaire. At the end of Stage 3 in Figure 1, PHAR-QA will put forward a proposal that represents a consensus (not unanimity) of the opinions of the expert panel members. This constitutes a starting point, and pharmacists around Europe will participate in order to ensure that the final proposed competences will have the widest possible acceptance.

- (3)

- The final framework will be validated by the large number of responses from pharmacists with widely varying occupations throughout Europe. Thus, the framework will be European, consultative and will encompass pharmacy practice in a wide sense.

- (4)

- In order to stimulate participation, the time needed to fill in the questionnaire is set at 30 min; thus, the number of questions is limited to 60–70.

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- PHAR-QA “Quality Assurance in European Pharmacy Education and Training”. 527194-LLP-1-2012-1-BE-ERASMUS-EMCR. Available online: http://www.pharmine.org/PHAR-QA/ (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- Bologna process on the website of the European Universities Association. Available online: http://www.eua.be/eua-work-and-policy-area/building-the-european-higher-education-area/bologna-basics.aspx (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- EU directive 2013/55/EU on the recognition of professional qualifications. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:255:0022:0142:EN:PDF (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- Hsu, C.C.; Sandford, B.A. The Delphi Technique: Making Sense of Consensus. Practical Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12. Available online: http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=12&n=10 (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- Cumming, A.D.; Ross, M.T. The Tuning Project for medicine: Learning outcomes for undergraduate medical education in Europe. Med. Teach. 2007, 29, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PHARMINE “Pharmacy Education and Training in Europe”. 142078-LLP-1-2008-1-BE-ERASMUS-ECDSP. Available online: http://www.pharmine.org/ (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- PHARMINE work programme 3. Available online: http://enzu.pharmine.org/media/filebook/files/PHARMINE%20WP3%20Lisbon%200611.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- Association for Dental Education in Europe. Available online: http://www.adee.org/ (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- CoDEG. The Competency Development and Evaluation Group. Available online: http://www.codeg.org/ (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- European Observatory on Health System and Policies. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/who-we-are/partners/observatory/eurohealth (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- Edmondson, D.R. Likert scales. A history. Available online: http://faculty.quinnipiac.edu/charm/CHARM%20proceedings/CHARM%20article%20archive%20pdf%20format/Volume%2012%202005/127%20edmondson.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- GraphPad®. Available online: http://www.graphpad.com/ (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- Raschi, D.; Guiard, V. The robustness of parametric statistical methods. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 46, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- The survey of the European network evaluation of the PHAR-QA framework of competences for pharmacists. Available online: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/pharqasurvey1 (accessed on 18 March 2014).

- European, Education, Audio-visual and Culture Agency (EACEA). Available online: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/index_en.php (accessed on 18 March 2014).

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Atkinson, J.; Rombaut, B.; Pozo, A.S.; Rekkas, D.; Veski, P.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. The Production of a Framework of Competences for Pharmacy Practice in the European Union. Pharmacy 2014, 2, 161-174. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2020161

Atkinson J, Rombaut B, Pozo AS, Rekkas D, Veski P, Hirvonen J, Bozic B, Skowron A, Mircioiu C, Marcincal A, et al. The Production of a Framework of Competences for Pharmacy Practice in the European Union. Pharmacy. 2014; 2(2):161-174. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2020161

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtkinson, Jeffrey, Bart Rombaut, Antonio Sánchez Pozo, Dimitrios Rekkas, Peep Veski, Jouni Hirvonen, Borut Bozic, Agnieska Skowron, Constantin Mircioiu, Annie Marcincal, and et al. 2014. "The Production of a Framework of Competences for Pharmacy Practice in the European Union" Pharmacy 2, no. 2: 161-174. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2020161

APA StyleAtkinson, J., Rombaut, B., Pozo, A. S., Rekkas, D., Veski, P., Hirvonen, J., Bozic, B., Skowron, A., Mircioiu, C., Marcincal, A., & Wilson, K. (2014). The Production of a Framework of Competences for Pharmacy Practice in the European Union. Pharmacy, 2(2), 161-174. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy2020161