Pharmacist Intervention Models in Drug–Drug Interaction Management in Prescribed Pharmacotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Models of Pharmacist Interventions

2.3. DDI Interaction Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Svensson, A. The Integral Role of Pharmacists in Patient Centered Medication Management. J. Basic Clin. Pharma. 2024, 15, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Zellars, M. The evolving role of clinical and hospital pharmacists in patient-centered care. Asian J. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 14, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Farhat, N.; Abbas, M. Planning and Developing a Clinical Pharmacy Practice. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schindler, E.; Richling, I.; Rose, O. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) drug-related problem classification version 9.00: German translation and validation. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juurlink, D.N.; Mamdani, M.; Kopp, A.; Laupacis, A.; Redelmeier, D.A. Drug–drug interactions among elderly patients hospitalized for drug toxicity. JAMA 2003, 289, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.J.G.; Tang, J.; Schrecker, J.; Hild, C. Impact of Definitive Drug–Drug Interaction Testing on Medication Management and Patient Care. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2018, 5, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palleria, C.; Di Paolo, A.; Giofrè, C.; Caglioti, C.; Leuzzi, G.; Siniscalchi, A.; De Sarro, G.; Gallelli, L. Pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction and their implication in clinical management. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Fidalgo, S.; Guzmán-Ramos, M.I.; Galván-Banqueri, M.; Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Santos-Ramos, B. Prevalence of drug interactions in elderly patients with multimorbidity in primary care. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, O.; Karimzadeh, I.; Davani-Davari, D.; Shafiekhani, M.; Sagheb, M.M.; Raees-Jalali, G.A. Drug–Drug Interactions among Kidney Transplant Recipients in the Outpatient Setting. Int. J. Organ Transpl. Med. 2020, 11, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.E.; Russo, V.; Walsh, C.; Menditto, E.; Bennett, K.; Cahir, C. Prevalence and factors associated with potential drug–drug interactions in older community-dwelling adults: A prospective cohort study. Drugs Aging 2021, 38, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahri, K.; Araujo, L.; Chen, S.; Bagri, H.; Walia, K.; Lau, L.; Legal, M. Community pharmacist perceptions of drug–drug interactions. Can. Pharm. J. 2022, 156, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, A.C.; Sloeserwij, V.M.; Zwart, D.L.; de Bont, A.A.; Bouvy, M.L.; de Gier, J.J.; de Wit, N.J.; Leendertse, A.J. Design of the POINT study: Pharmacotherapy Optimisation through Integration of a Non-dispensing pharmacist in a primary care Team (POINT). BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Luxembourg: European Commission. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Barrons, R. Evaluation of personal digital assistant software for drug interactions. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2004, 61, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazbar, J.; Locatelli, I.; Horvat, N.; Kos, M. Clinically relevant potential drug–drug interactions among outpatients: A nation-wide database study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toivo, T.M.; Mikkola, J.; Laine, K.; Airaksinen, M. Identifying high risk medications causing potential drug–drug interac-tions in outpatients: A prescription database study based on an online surveillance system. Res. Social Admin. Pharm. 2016, 12, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, L.; Arzenton, E.; Leone, R.; Stano, M.G.; Vezzaro, M.; Rudolph, A.; Castagna, I.; Moretti, U. Identifying and Characterizing Serious Adverse Drug Reactions Associated with Drug–Drug Interactions in a Spontaneous Reporting Database. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 622862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirosevic Skvrce, N.; Macolic Sarinic, V.; Mucalo, I.; Krnic, D.; Bozina, N.; Tomic, S. Adverse drug reactions caused by drug–drug interactions reported to Croatian Agency for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices: A retrospective observational study. Croat. Med. J. 2011, 52, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Létinier, L.; Cossin, S.; Mansiaux, Y.; Arnaud, M.; Salvo, F.; Bezin, J.; Thiessard, F.; Pariente, A. Risk of Drug–Drug Interactions in Out-Hospital Drug Dispensings in France: Results from the DRUG–Drug Interaction Prevalence Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual Report on Drug Utilisation for 2023—Croatian Document. Available online: https://halmed.hr/Novosti-i-edukacije/Publikacije-i-izvjesca/Izvjesca-o-potrosnji-lijekova/Izvjesce-o-potrosnji-lijekova-u-Republici-Hrvatskoj-u-2023/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Patel, P.S.; Rana, D.A.; Suthar, J.V.; Malhotra, S.D.; Patel, V.J. A study of potential adverse drug–drug interactions among pre-scribed drugs in medicine outpatient department of a tertiary care teaching hospital. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2014, 5, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, R.L.; Hanlon, J.; Hajjar, E.R. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2014, 13, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, S.; Scotti, L.; Galimberti, F.; Xie, S.; Casula, M.; Olmastroni, E. Operational definitions of polypharmacy and their association with all-cause hospitalization risk: A conceptual framework using administrative databases. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngcobo, N.N. Influence of ageing on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of chronically administered medicines in geriatric patients: A review. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 64, 335–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajizadeh, A.; Hafezi, R.; Torabi, F.; Akbari Sari, A.; Tajvar, M. Consequences of population ageing on health systems: A concep-tual framework for policy and practice. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2025, 35, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, T.; Leoni, T.; Reschenhofer, P.; Spielauer, M. The impact of ageing, socio-economic differences and the evolution of morbidity on future health expenditure—A dynamic microsimulation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinovic, I.; Bacic Vrca, V.; Samardzic, I.; Marusic, S.; Grgurevic, I. Potentially inappropriate medications involved in drug–drug interactions at hospital discharge in Croatia. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Momo, K. Impact of potentially inappropriate medications on emergency ambulance admissions in geriatric patients after discharge. Pharmazie 2024, 79, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 2052–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renom-Guiteras, A.; Meyer, G.; Thürmann, P.A. The EU(7)-PIM list: A list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somogyi-Végh, A.; Ludányi, Z.; Erdős, Á.; Botz, L. Countrywide prevalence of critical drug interactions in Hungarian outpatients: A retrospective analysis of pharmacy dispensing data. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type A—Independent Pharmacist Interventions |

|---|

| A1—Patient counseling and education |

| A2—Monitoring therapeutic parameters |

| A3—Change/split dosing interval |

| A4—Monitoring side effects |

| Type B—Dependent pharmacist interventions (recommendations to the physician) |

| B1—Monitoring (therapeutic effect, drug concentration, side effects) |

| B2—Dose adjustment |

| B3—Substitution of one of the interacting drugs |

| B4—Therapy duplication—discontinuation of one of the drugs |

| B5—Evaluation of drug use |

| B6—Limiting the duration of drug use |

| B7—Necessity to introduce an additional drug |

| B8—Change in pharmaceutical form of the drug |

| B9—Temporary discontinuation of one interacting drug |

| B10—Discontinuation of a specific drug with a washout period before introducing a new one |

| B11—Gradual drug withdrawal |

| Total | <65 Years | ≥65 Years | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, N (%) | 4107 (100) | 1528 (47.2) | 2579 (62.8) | <0.001 |

| Female gender, N (%) | 2322 (56.5) | 824 (53.9) | 1498 (58.1) | 0.010 |

| ICD diagnoses, N mean ± SD range | 14,026 3.42 ± 1.65 (1–11) | 4636 2.03 ± 1.54 (1–11) | 9390 3.64 ± 1.67 (1–11) | <0.001 |

| Medications, N mean ± SD range | 22,668 5.52 ± 2.58 (2–18) | 7533 4.93 ± 2.45 (2–17) | 15,135 5.87 ± 2.59 (2–18) | <0.001 |

| DDIs, N (median) average rang range | 14,175 2 (1–5) (0–31) | 4817 (2.0) 1926.5 (0–25) | 9358 (2.0) 2129.5 (0–31) | <0.001 |

| C interactions, N (median) average rang range | 11,803 2 (0–4) (0–28) | 3891 (1.0) 1906.9 (0–20) | 7912 (2.0) 2141.1 (0–28) | <0.001 |

| D interactions, N (median) average rang range | 2182 0 (0–1) (0–13) | 835 (0.0) 2034.7 (0–10) | 1347 (0.0) 2065.4 (0–13) | 0.326 |

| X interactions, N (median) average rang range | 190 0 (0–0) (0–3) | 91 (0.0) 2079.7 (0–2) | 99 (0.0) 2038.8 (0–3) | 0.002 |

| Total | Rural Areas | Urban Areas | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, N (%) | 4107 (100) | 2050 (49.9) | 2057 (50.1) | 0.913 |

| Age, years mean ±SD range | 67.47 ± 13.674 (18–102) | 67.35 ±13.617 (18–96) | 67.60 ± 13.733 (19–102) | 0.566 |

| ≥65 years, N (%) | 2579 (62.8) | 1261 (61.5) | 1318 (64.1) | 0.093 |

| Female gender, N (%) | 2322 (56.5) | 1141 (55.7) | 1181 (57.4) | 0.257 |

| ICD diagnoses, N mean ± SD range | 14,026 3.42 ± 1.647 (1–11) | 7095 3.46 ± 1.692 (1–11) | 6931 3.37 ± 1.599 (1–11) | 0.075 |

| Medications, N mean ± SD range | 22,668 5.52 ± 2.585 (2–18) | 11,545 5.63 ± 2.642 (2–18) | 11,123 5.41 ± 2.521 (2–16) | 0.005 |

| DDIs, N (median) average rang range | 14,175 2 (1–5) (0–31) | 7555 2 (1–5) (0–31) | 6620 2 (1–4) (0–29) | <0.001 |

| C interactions, N (median) average rang range | 11,803 2 (0–4) (0–28) | 6261 2 (1–4) (0–24) | 5542 2 (0–4) (0–28) | <0.001 |

| D interactions, N (median) average rang range | 2182 0 (0–1) (0–13) | 1179 0 (0–1) (0–13) | 1003 0 (0–1) (0–12) | 0.003 |

| X interactions, N (median) average rang range | 190 0 (0–0) (0–3) | 115 0 (0–0) (0–3) | 75 0 (0–0) (0–3) | 0.009 |

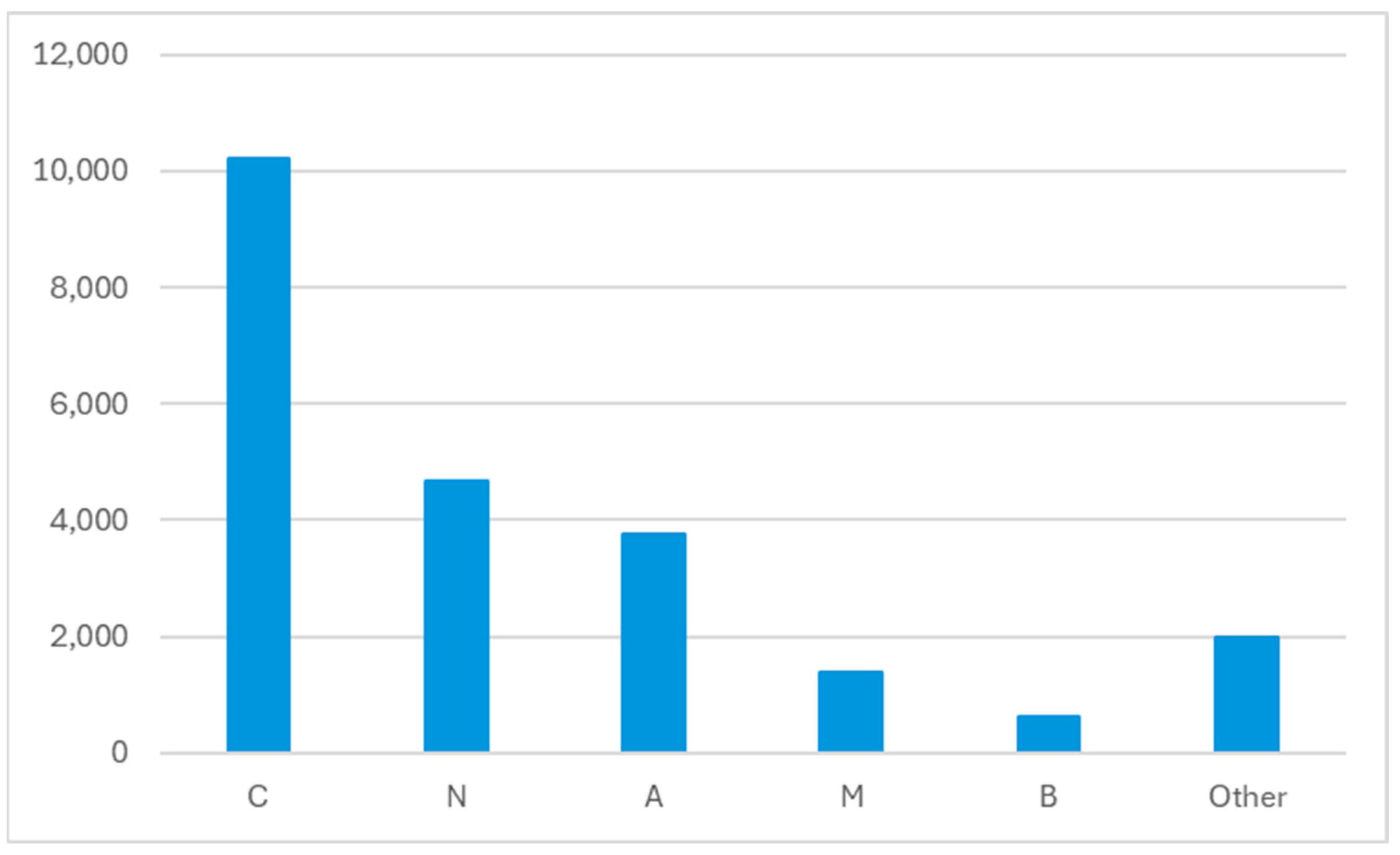

| ATC | Drug | N |

|---|---|---|

| C08CA01 | amlodipine | 1055 |

| C07AB07 | bisoprolol | 1038 |

| C09AA04 | perindopril | 778 |

| A02BC02 | pantoprazole | 774 |

| N05BA01 | diazepam | 741 |

| C10AA05 | atorvastatin | 732 |

| C09AA05 | ramipril | 718 |

| C03AA03 | hydrochlorothiazide | 697 |

| A10BA02 | metformin | 676 |

| C03BA11 | indapamide | 625 |

| N02AX02 | tramadol | 588 |

| C03CA01 | furosemide | 544 |

| N05BA12 | alprazolam | 514 |

| M01AE01 | ibuprofen | 488 |

| N02BE01 | paracetamol | 468 |

| H03AA01 | levothyroxine | 426 |

| C09CA03 | valsartan | 370 |

| C10AA07 | rosuvastatin | 356 |

| C07AB12 | nebivolol | 315 |

| G04CA02 | tamsulosin | 304 |

| Total | DDIs Categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | D | X | ||

| DDIs, N (%) | 14,175 (100) | 11,803 (83.3) | 2182 (15.4) | 190 (1.3) |

| Patients with DDIs, N (%) | 3228 (78.6) | 3043 (74.1) | 1289 (31.4) | 169 (4.1) |

| DDIs, median (IQR) (range) | 2 (1–5) (0–31) | 2 (0–4) (0–28) | 0 (0–1) (0–13) | 0 (0–0) (0–3) |

| C DDIs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Drug | Potential DDI Consequence | DDI Management and Model |

| perindopril | indapamide | Indapamide may increase the nephrotoxic and hypotensive effects of ACEIs. |

|

| valsartan | HCTZ | Hydrochlorothiazide may increase the hypotensive effect of valsartan. Valsartan may increase the serum concentration of hydrochlorothiazide. |

|

| lizinopril | HCTZ | Hydrochlorothiazide may enhance the nephrotoxic and hypotensive effects of ACEIs. |

|

| ramiprile | HCTZ | Hydrochlorothiazide may enhance the nephrotoxic and hypotensive effects of ACEIs. |

|

| metformin | perindopril | ACEIs may increase the risk of side effects/toxic effects of metformin. |

|

| D DDIs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Drug | Potential DDI Effect | DDI Management and Model |

| diazepam | tramadol | Increased risk of CNS depression. |

|

| alprazolam | tramadol | Increased risk of CNS depression. |

|

| diazepam | zolpidem | Increased risk of CNS depression. |

|

| bisoprolol | moxonidine | Alpha2-agonists may potentiate the AV-blocking effect of beta-blockers. Sinus node dysfunction may also be potentiated. Beta-blockers may potentiate the rebound hypertensive effect of alpha2-agonists. This effect may occur when the alpha2-agonist is abruptly withdrawn. |

|

| alprazolam | zolpidem | Increased risk of CNS depression. |

|

| X DDIs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Drug | Potential DDI Effect | DDI Management and Model |

| diazepam | olanzapine | Olanzapine may enhance the effects of benzodiazepines. | Avoid concomitant use, consider another drug combination. B3 |

| furosemide | promazine | Loop diuretics may increase the QTc potential of promazine. | Avoid concomitant use, consider another drug combination. B3 |

| alprazolam | olanzapine | Olanzapine may enhance the effects of benzodiazepines. | Avoid concomitant use, consider another drug combination. B3 |

| carbamazepine | tramadol | Tramadol may increase the CNS depressant effect of carbamazepine. Tramadol may decrease the therapeutic effect of carbamazepine. Carbamazepine may decrease the concentration of tramadol. | Avoid concomitant use, consider another drug combination. B3 |

| diclofenac | ibuprofen | Increased risk of gastrointestinal toxicity. | Duplication of medications, it is necessary to exclude one of the medications from the same therapeutic group. B4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samardžić, I.; Marinović, I.; Marović, I.; Kuča, N.; Bačić Vrca, V. Pharmacist Intervention Models in Drug–Drug Interaction Management in Prescribed Pharmacotherapy. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060167

Samardžić I, Marinović I, Marović I, Kuča N, Bačić Vrca V. Pharmacist Intervention Models in Drug–Drug Interaction Management in Prescribed Pharmacotherapy. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(6):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060167

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamardžić, Ivana, Ivana Marinović, Iva Marović, Nikolina Kuča, and Vesna Bačić Vrca. 2025. "Pharmacist Intervention Models in Drug–Drug Interaction Management in Prescribed Pharmacotherapy" Pharmacy 13, no. 6: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060167

APA StyleSamardžić, I., Marinović, I., Marović, I., Kuča, N., & Bačić Vrca, V. (2025). Pharmacist Intervention Models in Drug–Drug Interaction Management in Prescribed Pharmacotherapy. Pharmacy, 13(6), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060167