Community Health Empowerment Through Clinical Pharmacy: A Single-Arm, Post-Intervention-Only Pilot Implementation Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

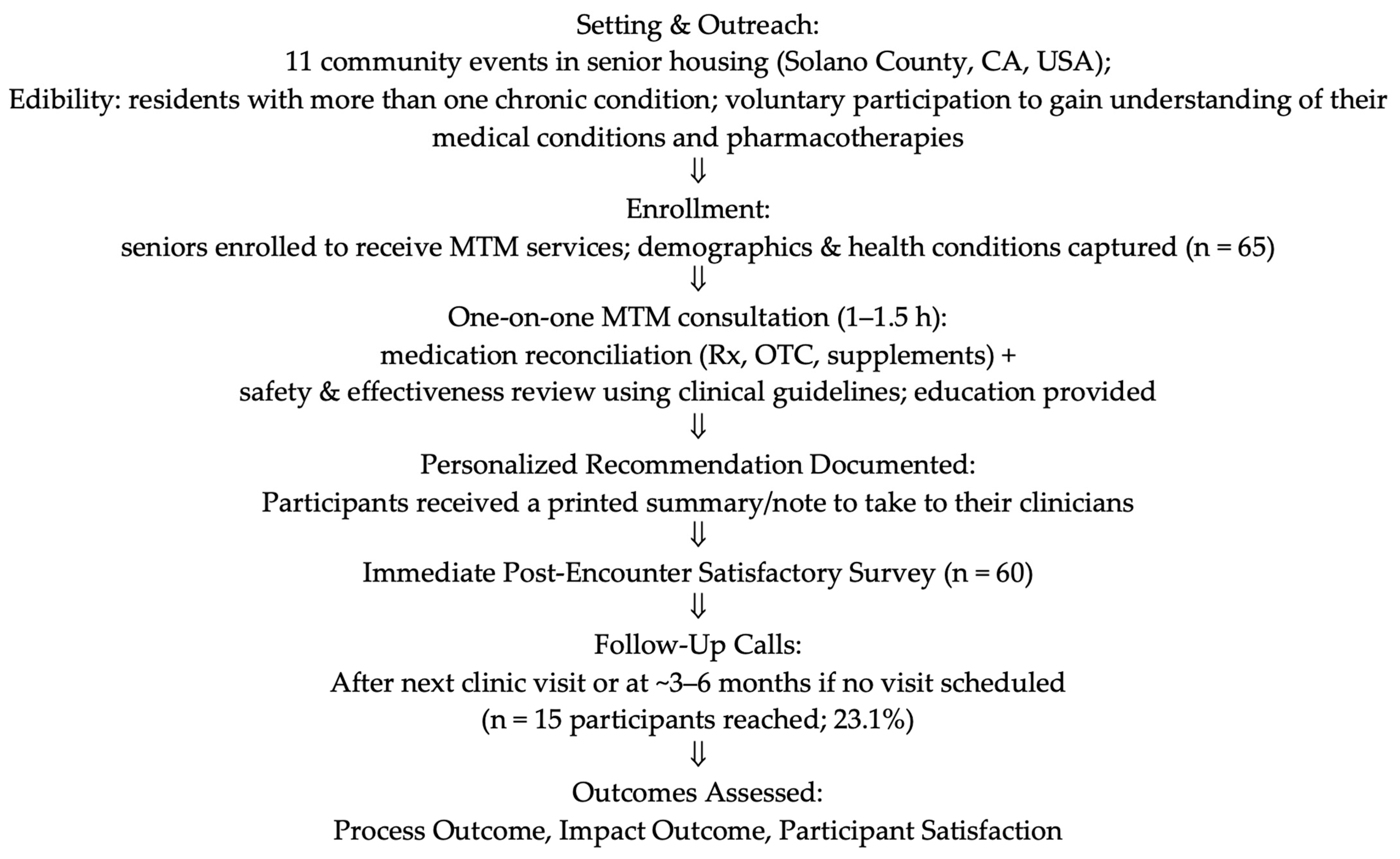

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. The Intervention

- Preparation: Thoroughly reviewed the medication lists (if provided) by the participant, including medication bottles and any associated records. If available, noted the participant’s renal and liver functions.

- Medication Reconciliation (Collect): Compiled a comprehensive medication history, including prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, supplements, doses, frequencies, indications, adherence routines, and potential barriers to adherence. A history intake form and a clinical note template were developed to serve this purpose (See Supplemental Materials for more details).

- Clinical Assessment (Assess):

- a.

- Identified drug-related issues:

- i.

- Indication: Determined the appropriate use of the drug based on the participant’s medical conditions.

- ii.

- Effectiveness: Evaluated the drug’s efficacy in treating the participant’s symptoms.

- iii.

- Safety: Assessed the potential risks and side effects of the drug.

- iv.

- Adherence: Asked about the participant’s adherence to the prescribed medication regimen.

- b.

- Applied explicit criteria for appropriateness:

- i.

- AGS Beers: Ensured that the participant was not taking prescribed medications on this list.

- ii.

- Renal dose adjustments: Monitored the participant’s renal/liver functions and recommended adjustments to medication dosage as necessary.

- iii.

- Major interactions: Identified potential interactions between the prescribed medication and other medications the participant was taking.

- iv.

- Duplication: Verified that the participant is not taking two medications within the same class or with a similar mechanism of action.

- Education and Problem-Solving (Plan): Used plain language counseling, provided large-print handouts (if available), used pictograms, and facilitated teach-back to reinforce understanding. Addressed any capability or opportunity barriers (e.g., cost, accessibility, regimen complexity); offered pill organizers when feasible. The encounters were conducted in English, and for those who spoke a language other than English, a family member was present or a staff member from the site assisted with translation.

- Action Plan Sharing (Implement): Collaborated on a concise action plan, involving shared decision-making, to outline agreed-upon action steps, monitoring mechanisms, warning indicators, and tasks for the upcoming PCP discussion.

- Documentation: Completed the structured template at the end of the day, particularly focusing on a concise summary (medication regimen modification recommendations and rationale, Beers/interaction flags, monitoring requests) that would assist the participant in communicating with their PCP. This post-encounter clinical note was either emailed or mailed to the participant within one week after the encounter.

- Follow-Up Call to Inquire about the Acceptance of Recommendations (Follow-Up): A standardized follow-up call would be attempted within four weeks (up to three attempts at different times) by a clinical pharmacist. This call would be utilized to assess the participants’ uptake of our recommendations, including the implementation and discussion of these recommendations during the PCP’s office visit.

2.3. Participants and Data Sources

2.3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Managed one or more chronic diseases (self-reported);

- Resided in a low-income senior housing facility within Solano County, CA at the time of the event; and

- Provided informed consent to participate in the MTM encounter and surveys administered at the community events.

- Were not residents of the partnering senior housing sites;

- Declined or were unable to provide consent;

- Were acutely unwell and required urgent medical attention at presentation.

2.3.2. Data Collection

2.4. Medication Appropriateness

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Sample Size & Statistical Methods

- Missing responses were recorded as “no response available” and excluded from calculating specific outcome measures (such as participant satisfaction) that required participant feedback.

- For measures requiring a follow-up response (such as participant-reported behavioral changes or clinician acceptance of recommendations), percentages were calculated based on the available data rather than the initial number of participants enrolled.

- Given the voluntary nature of follow-up participation, we acknowledge that missing data can impact our overall study outcomes. To address this issue, future studies will implement structured follow-up strategies, such as scheduled calls or text reminders, to improve participant retention.

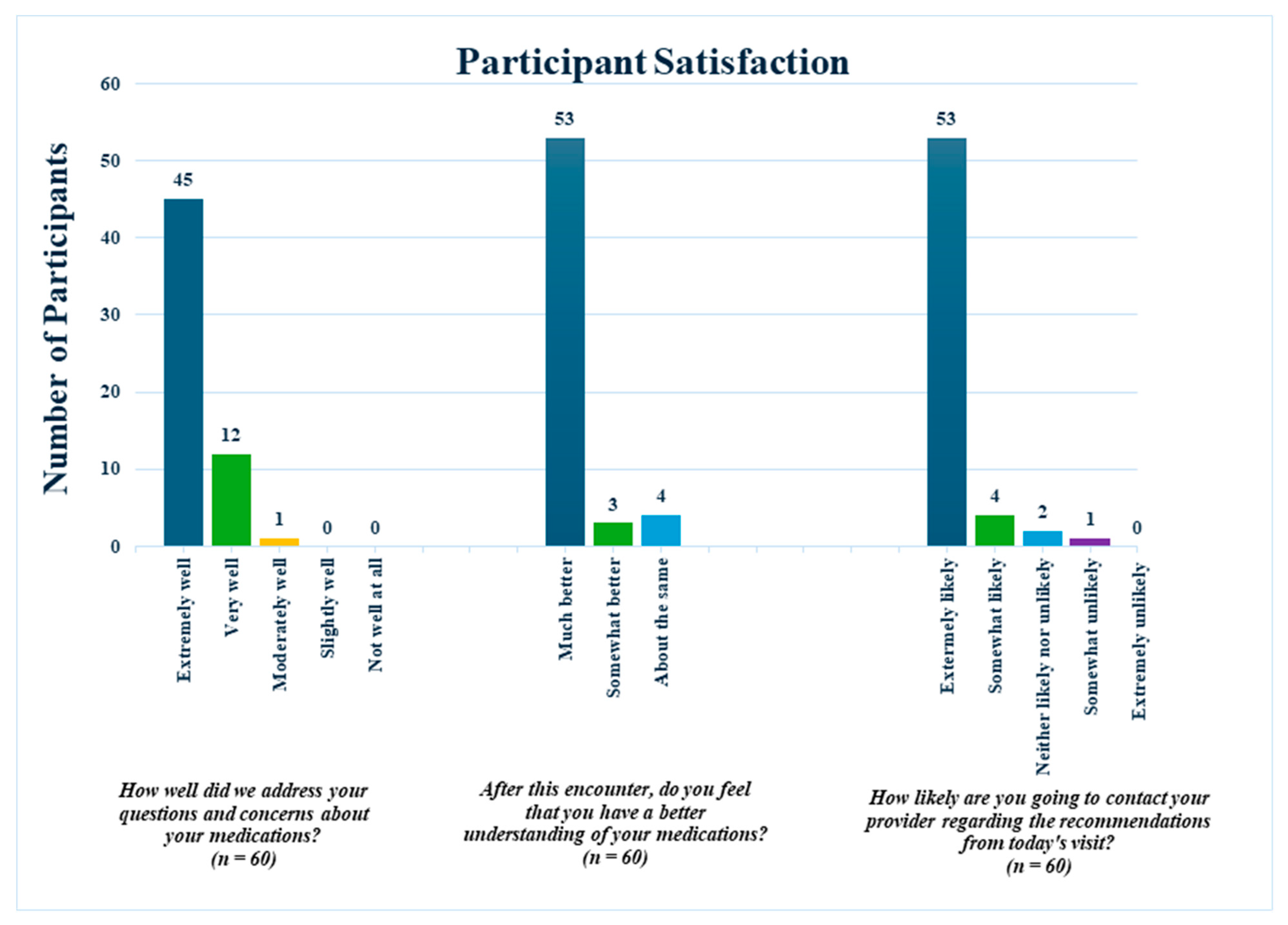

2.7. Bias

2.8. Participant Satisfaction Survey

2.9. Follow-Up Calls

2.10. Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Statement of Key Findings

4.2. Strengths: Reflecting on Aligning with Health Equity

4.3. Weaknesses

4.4. Interpretation: Implications for Practice

- (1)

- Our results underscore the importance of involving pharmacists in direct patient education and care management, extending beyond their traditional roles in pharmacies. Health promotion programs should integrate clinical pharmacists into community centers, senior homes, and local clinics, where they can provide personalized consultations and empower patients through education.

- (2)

- Given our participants’ high appreciation for personalized education sessions, health systems should consider developing targeted educational materials that address the specific needs and common conditions of the senior population. These programs should focus on managing medication, understanding prevalent chronic conditions, and navigating the healthcare system effectively.

- (3)

- Encouraging self-management is a key component of the P2H Initiative. Future programs should incorporate tools and resources that help seniors track their medication schedules, understand their prescriptions, and identify when to seek medical advice. This would promote greater independence and confidence in managing their health and wellness.

4.5. Potential Pathways to Improve Communication and PCP Acceptance of Recommendations

- Situation: A concise summary of the patient’s problem.

- Background: Information regarding relevant medications and contraindications.

- Assessment: Concerns regarding safety and effectiveness, Beers violations, and any drug–drug interactions.

- Recommendations: Specific actions, monitoring, and follow-up intervals.

- This revised summary includes clear guideline citations and, where applicable, renal dose or drug–drug interactions to reduce cognitive load. For high-risk items (e.g., Category D interactions, clear Beers violations), schedule a same-week P2H-to-PCP call to discuss the most critical change and agree on a monitoring plan.

4.6. Looking into the Future: Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aging In America: Get the Facts on Healthy Aging. National Council on Aging. 2024. Available online: https://www.ncoa.org/article/get-the-facts-on-healthy-aging (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Importance of Health Literacy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/older-adults/importance-health-literacy.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/audiences/olderadults/importance.html (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Chronic Care Model. Rural Health Information Hub. 2024. Available online: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/chronic-disease/2/chronic-care (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Valliant, S.N.; Burbage, S.C.; Pathak, S.; Urick, B.Y. Pharmacists as accessible health care providers: Quantifying the opportunity. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2022, 28, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRemer, C.E.; VanLandingham, J.; Carswell, J.; Killough, D. Pharmacy outreach education program in the local community. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 94. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2576433/ (accessed on 29 March 2025). [PubMed]

- Harms, M.; Haas, M.; Larew, J.; DeJongh, B. Impact of a mental health clinical pharmacist on a primary care mental health integration team. Ment. Health Clin. 2017, 7, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs): Overview. 2023–2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023—Chronic Conditions; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2023/11/health-at-a-glance-2023_e04f8239/full-report/chronic-conditions_2dfe9bb5.html (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Das, D.C.; Sunna, T.C.; Beyene, J.; Hossain, A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.C.P.; Maximiano-Barreto, M.A.; Martins, T.C.R.; Luchesi, B.M. Factors associated with poor health literacy in older adults: A systematic review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 55, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP). 2025 Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process (PPCP): Revision of the 2014 PPCP. Approved 20 May 2025. Available online: https://jcpp.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Pharmacists-Patient-Care-Process-Document-2025.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- American Geriatrics Society. American Geriatrics Society 2023 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 2052–22081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.X.; Zhu, C.; Liang, H.Y.; Wang, K.; Chu, Y.Q.; Zhao, L.B.; Jiang, D.C.; Wang, Y.Q.; Yan, S.Y. Associations Between Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Adverse Health Outcomes in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2019, 53, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.B.; Redley, B.; de Courten, B.; Manias, E. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and its associations with health-related and system-related outcomes in hospitalized older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 4150–4172. [Google Scholar]

- Issel, L.M. Health Program Planning and Evaluation: A Practical, Systematic Approach for Community Health, 2nd ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0763753344. [Google Scholar]

- Aghili, M.; Kasturirangan, M.N. Management of Drug-Drug Interactions among Critically Ill Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: Impact of Clinical Pharmacist’s Interventions. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marupuru, S.; Roether, A.; Guimond, A.J.; Stanley, C.; Pesqueira, T.; Axon, D.R. A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes from Pharmacist Provided Medication Therapy Management (MTM) among Patients with Diabetes, Hypertension, or Dyslipidemia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doellner, J.F.; Dettloff, R.W.; DeVuyst-Miller, S.; Wenstrom, K.L. Prescriber acceptance rate of pharmacists’ recommendations. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017, 57, S197–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcum, Z.A.; Jiang, S.; Bacci, J.L.; Ruppar, T.M. Pharmacist-led interventions to improve medication adherence in older adults: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 3301–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gray, S.L.; Perera, S.; Soverns, T.; Hanlon, J.T. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Interventions to Reduce Adverse Drug Reactions in Older Adults: An Update. Drugs Aging 2023, 40, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roncal-Belzunce, V.; Gutiérrez-Valencia, M.; Leache, L.; Saiz, L.C.; Bell, J.S.; Erviti, J.; Martínez-Velilla, N. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of multidisciplinary interventions to address polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 98, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregan, A.; Heydon, S.; Braund, R. Understanding the factors influencing prescriber uptake of pharmacist recommendations in secondary care. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 3438–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Ray, R.; Feng, L.; Singh, T.; Rudkin, K.; Emmons, S.; Groves, E.; Kirkham, H. Pharmacists as clinical care partners: How a pharmacist-led intervention is associated with improved medication adherence in older adults with common chronic conditions. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2024, 30, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, P.H.; Leasure, A.R. Use and Effectiveness of the Teach-Back Method in Patient Education and Health Outcomes. Fed. Pract. 2019, 36, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Tool: Teach-Back; AHRQ: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/curriculum/communication/tools/teachback.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Ploenzke, C.; Kemp, T.; Naidl, T.; Marraffa, R.; Bolduc, J. Design and Implementation of a Targeted Approach for Pharmacist-mediated Medication Management at Care Transitions. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2015, 56, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, M.; Crisafulli, S.; Vitturi, G.; Besco, M.; Hinek, D.; Sartorio, A.; Tanara, V.; Spadacini, G.; Selleri, M.; Zanconato, V.; et al. Clinical impact of medication review and deprescribing in older inpatients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 3219–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, K.; Taljaard, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Hooper, R.; Copas, A.; Thompson, J.A.; Dixon-Woods, M.; Aldcroft, A.; Doussau, A.; Grayling, M.; et al. Reporting of stepped wedge cluster randomised trials: Extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement with explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2018, 363, k1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linsky, A.M.; Motala, A.; Booth, M.; Lawson, E.; Shekelle, P.G. Deprescribing in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e259375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Selection Bias | Participating in the MTM sessions was voluntary, which could potentially introduce self-selection bias. To mitigate this concern, all eligible seniors residing in the housing facilities were invited to participate through standardized outreach efforts, thereby ensuring a board and representative sample. |

| Recall Bias | Recall bias, which occurs when participants share information based on their memory rather than objective facts, could have influenced their responses during and after the encounters. To address this, the team implemented a check-and-balance system by incorporating subjective and objective information during the encounters. However, during the encounters, the team was limited to responding to what the participants were willing to share, which posed a challenge in determining whether recall bias was present. |

| Confounding Bias | Given the influence of various factors beyond our team’s interventions on chronic disease management, potential confounders like healthcare access, baseline health literacy, and socioeconomic status were present. Whenever possible, our findings were contextualized within the broader healthcare context. Future studies may include control groups or more structured comparisons to validate our results. |

| Measurement Bias | The use of study-specific forms and short surveys without validation may have introduced measurement bias. |

| n = 65 | |||

| Mean Age (SD) | 74.5 (7.6) years old | ||

| Gender | Educational Level | ||

| Male | 19 (29.2%) | 8th Grade or Less | 10 (15.4%) |

| Female | 46 (70.8%) | Some High School | 8 (12.3%) |

| Nonbinary/Transgender/Bisexual/Prefer not to say | 0 (0%) | High School Degree | 18 (27.7%) |

| Race | Some College | 22 (33.8%) | |

| Asian | 19 (29.2%) | Bachelor’s Degree | 6 (9.2%) |

| African American | 19 (29.2%) | Prefer Not To Say | 1 (1.5%) |

| Caucasian/White | 16 (24.6%) | Marital Status | |

| Native Hawaiian | 1 (1.5%) | Married | 13 (20%) |

| Other | 9 (13.8%) | Single | 20 (30.1%) |

| Ethnicity | Divorced/Separated | 16 (24.6%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (15.4%) | Widowed | 15 (23.1%) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 55 (84.6%) | Prefer Not To Say | 1 (1.5%) |

| Primary Language | Hospitalization/Surgery < 12 Months | ||

| English | 40 (61.5%) | Yes | 28 (43.1%) |

| Tagalog | 11 (16.9%) | No | 37 (56.9%) |

| Spanish | 6 (9.2%) | Immunized a | |

| Mandarin | 2 (3.1%) | Yes | 13 (20%) |

| Punjabi | 2 (3.1%) | No | 51 (78.5%) |

| Other | 4 (6.2%) | Unsure | 1 (1.5%) |

| Insurance | COVID-19 Vaccines (Initial Series) | ||

| Medicare | 20 (30.8%) | Yes | 56 (86.2%) |

| Medicaid | 6 (9.2%) | No | 9 (13.8%) |

| Both Medicare and Medicaid | 34 (52.3%) | COVID-19 Booster Vaccine | |

| Commercial | 5 (7.7%) | Yes | 51 (78.5%) |

| No | 14 (21.5%) | ||

| Process Outcomes (Interventions Made During the Encounters) | |

| # of Over-The-Counter (OTC) and Supplement Items Evaluated | 106 |

| # of Prescriptions Evaluated | 385 |

| Total Number of Items Evaluated | 491 |

| Issues Identified (Total = 118) | |

| # of Expired Medications | 26 (5.3% a) |

| # of Untreated Conditions | 21 (4.3% a) |

| # of Therapeutic Duplications | 8 (1.6% a) |

| # of Medications without an Indication | 20 (4.1% a) |

| # of Category D b Drug–Drug Interactions | 16 (3.3% a) |

| # of Contraindications | 4 (0.81% a) |

| # of Medications on Beers Criteria | 14 (2.8% a) |

| # of Adverse Drug Reactions Identified | 9 (1.8% a) |

| 118/491 = 24.0% | |

| Consultations (Total = 126) | |

| Medication Counseling | 61 (48.4%) |

| Immunization Counseling | 23 (18.3%) |

| Lifestyle Counseling | 21 (16.7%) |

| Other Counseling c | 21 (16.7%) |

| Impact Outcomes (Data Collected Post-Encounter) | ||||||

| Event | Number of Participants Served | Number of Recommendations Made or Education Points Shared | Number of Participants Followed-Up | Number of Modifications Made by Participants | Number of Recommendations P2H Encouraged Participants Bringing to Their PCPs/Clinicians | Number of Recommendations Accepted by Participants’ PCPs at a Subsequent Medical Appt |

| 1 | 12 | 34 | 8 | 10 | 23 | 16 |

| 2 | 7 | 35 | 2 | 8 | 14 | 6 |

| 3 | 8 | 26 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 2 |

| 4 | 7 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 5 |

| 7 | 6 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| 8 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 9 | 6 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| 10 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 7 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sum | 65 | 192 | 15 | 23 | 93 | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Young, C.F.; Shubrook, C.; Myung, C.; Rigby, A.; Wong, S.M.T. Community Health Empowerment Through Clinical Pharmacy: A Single-Arm, Post-Intervention-Only Pilot Implementation Evaluation. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050141

Young CF, Shubrook C, Myung C, Rigby A, Wong SMT. Community Health Empowerment Through Clinical Pharmacy: A Single-Arm, Post-Intervention-Only Pilot Implementation Evaluation. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(5):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050141

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoung, Clipper F., Casey Shubrook, Cherry Myung, Andrea Rigby, and Shirley M. T. Wong. 2025. "Community Health Empowerment Through Clinical Pharmacy: A Single-Arm, Post-Intervention-Only Pilot Implementation Evaluation" Pharmacy 13, no. 5: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050141

APA StyleYoung, C. F., Shubrook, C., Myung, C., Rigby, A., & Wong, S. M. T. (2025). Community Health Empowerment Through Clinical Pharmacy: A Single-Arm, Post-Intervention-Only Pilot Implementation Evaluation. Pharmacy, 13(5), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050141