Primary Care Pharmacy Competencies of Graduates from a Community-Focused Curriculum: Self- and Co-Worker Assessments

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. A Community-Focused Pharmacy Curriculum

1.1.1. Year 2 (Junior Students)

1.1.2. Year 5 (Senior Students)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. PCP Competencies

2.3. Questionnaire Validation

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Survey Respondents

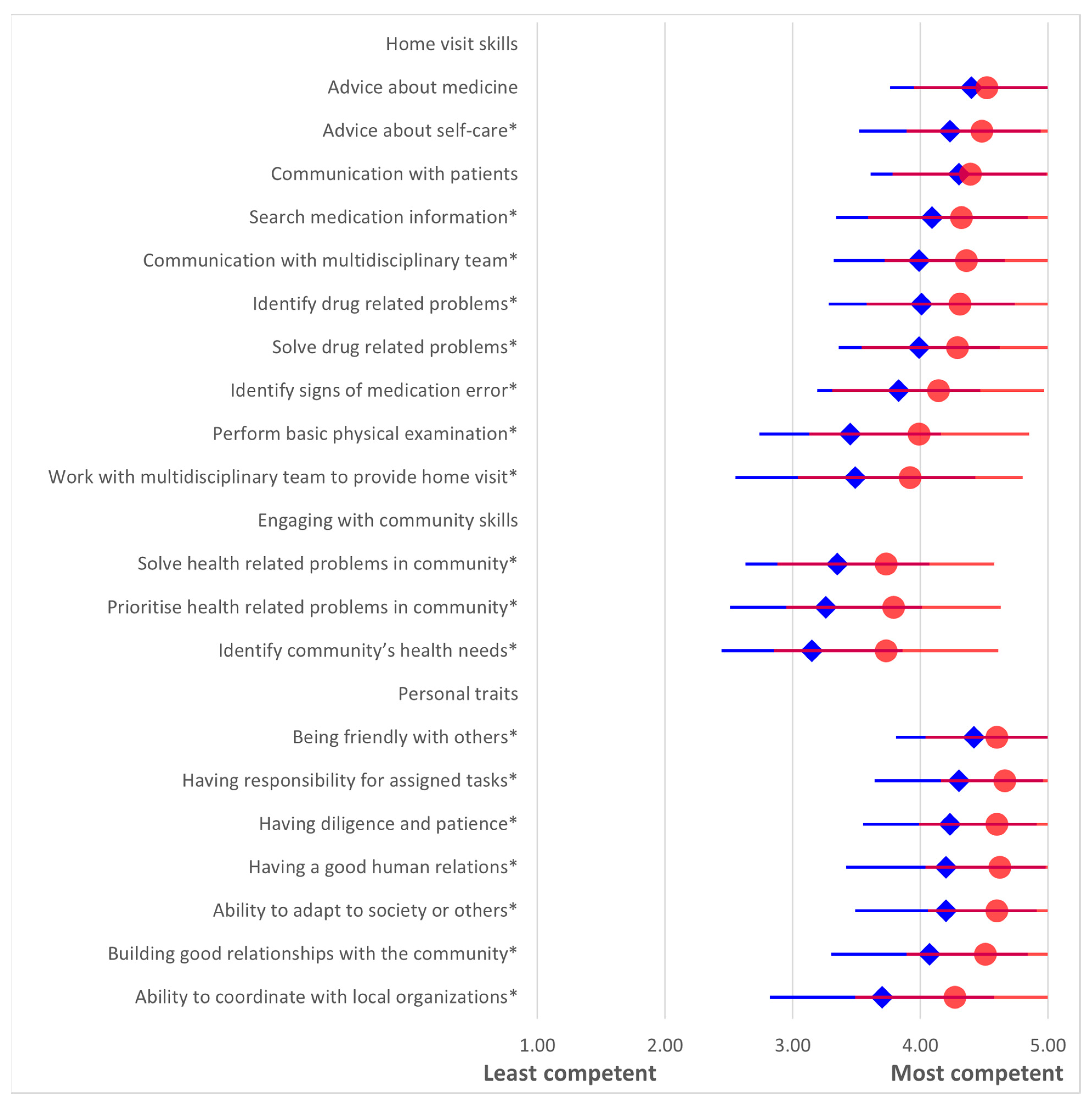

3.2. Primary Care Pharmacy Competency

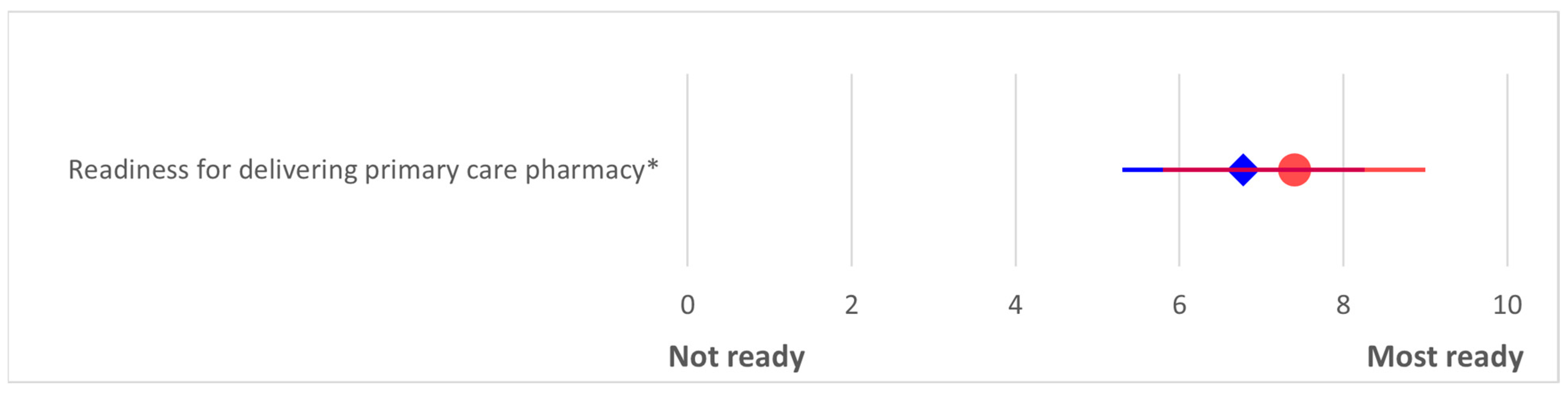

3.3. Readiness for Delivering Primary Care Pharmacy

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Pharmacy Education

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCP | Primary Care Pharmacy |

| CBE | Community-based education |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

References

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Astana. In Proceedings of the Global Conference on Primary Health Care, Astana, Kazakhstan, 25–26 October 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann, J.; Oliveira, A.P.C.d.; Maier, C.B.; Ray, S.; Dussault, G. Health and care workforce. In Implementing the Primary Health Care Approach: A Primer (Global Report on Primary Health Care); Rajan, D., Rouleau, K., Winkelmann, J., Jakab, M., Kringos, D., Khalid, F., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vogler, S.; Leopold, C.; Suleman, F.; Wirtz, V.J. Medicines and pharmaceutical services. In Implementing the Primary Health Care Approach: A Primer (Global Report on Primary Health Care); Rajan, D., Rouleau, K., Winkelmann, J., Jakab, M., Kringos, D., Khalid, F., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, P.S.; Barns, A. Current perspectives on pharmacist home visits: Do we keep reinventing the wheel? Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2018, 7, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpradit, N.; Chongtrakul, P.; Anuwong, K.; Pumtong, S.; Kongsomboon, K.; Butdeemee, P.; Khonglormyati, J.; Chomyong, S.; Tongyoung, P.; Losiriwat, S.; et al. Antibiotics Smart Use: A workable model for promoting the rational use of medicines in Thailand. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. FIP Global Competency Framework: Version 2 (GbCFv2); International Pharmaceutical Federation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bajis, D.; Al-Haqan, A.; Mhlaba, S.; Bruno, A.; Bader, L.; Bates, I. An evidence-led review of the FIP global competency framework for early career pharmacists training and development. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yongpraderm, S.; Sornlertlumvanich, K. Exploring Competencies of Primary Care Pharmacists Practicing in Public Sector: A Qualitative Study. Thai J. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 19, 276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Chanasopon, S.; Saramunee, K.; Rotjanawanitsalee, T.; Jitsanguansuk, N.; Chaiyasong, S. Provision of primary care pharmacy operated by hospital pharmacist. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwannaprom, P.; Suttajit, S.; Eakanunkul, S.; Supapaan, T.; Kessomboon, N.; Udomaksorn, K. Development of pharmacy competency framework for the changing demands of Thailand’s pharmaceutical and health services. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 18, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. National Competency Standards Framework for Pharmacist in Australia; Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd.: Deakin, ACT, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Uakarn, C.; Chaokromthong, K.; Sintao, N. Sample Size Estimation using Yamane and Cochran and Krejcie and Morgan and Green Formulas and Cohen Statistical Power Analysis by G*Power and Comparisions. APHEIT Int. J. 2021, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, V.; Wong, C.; Coombes, I.; Cardiff, L.; Duggan, C.; Yee, M.L.; Lim, K.W.; Bates, I. Use of a general level framework to facilitate performance improvement in hospital pharmacists in Singapore. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012, 76, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestrovic, A.; Stanicic, Z.; Hadziabdic, M.O.; Mucalo, I.; Bates, I.; Duggan, C.; Carter, S.; Bruno, A. Evaluation of Croatian community pharmacists’ patient care competencies using the general level framework. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2011, 75, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstzen, D.V.; Schmutz, A.M.S.; Meyer, I.S. The learning experiences and perspectives of physiotherapy students during community-based education placements. In Transformation of Learning and Teaching in Rehabilitation Sciences: A Case Study from South Africa; Ernstzen, D.V., Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi, L.A.J., Bardien, F., Eds.; Human Functioning, Technology and Health: Cape Town, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Claramita, M.; Setiawati, E.P.; Kristina, T.N.; Emilia, O.; van der Vleuten, C. Community-based educational design for undergraduate medical education: A grounded theory study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, E. Notes for primary care teachers: Teaching methods used in primary care. Malays. Fam. Physician 2008, 3, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeier, K.C.; Spivey, C.A.; Chisholm-Burns, M. A community-based partnership collaborative practice agreement project to teach innovation in care delivery. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullatif Alnasir, F.; Jaradat, A.A. The effect of training in primary health care centers on medical students’ clinical skills. ISRN Fam. Med. 2013, 2013, 403181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanchatchai, C.; Khuancharee, K.; Rattanamongkolgul, S.; Kongsomboon, K.; Onwan, M.; Seeherunwong, A.; Chewparnich, P.; Yoadsomsuay, P.; Buppan, P.; Taejarernwiriyakul, O.; et al. The effectiveness of community-based interprofessional education for undergraduate medical and health promotion students. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saramunee, K.; Arparsrithongsakul, S.; Poophalee, T.; Chaiyasong, S.; Ploylearmsang, C. Community Learning Program integrated in PharmDCurriculum [in Thai]. Thai J. Pharm. Pract. 2015, 7, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Saramunee, K.; Srisaknok, T.; Chaiyasong, S.; Arparsrithongsakul, S.; Ploylearmsang, C.; Poophalee, T.; Chumalee, I. Learning outcomes from a 7-day health promotion camp organised by pharmacy students in community. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramunee, K.; Chaiyasong, S.; Anusornsangiam, W.; Kansutti, N.; Phasuk, P. A Survey of Need to Improve Knowledge and Skills for Primary Care Pharmacies. J. Sci. Technol. Mahasarakham Univ. 2017, 36, 543–552. [Google Scholar]

- Auimekhakul, T.; Suttajit, S.; Suwannaprom, P. Pharmaceutical public health competencies for Thai pharmacists: A scoping review with expert consultation. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2024, 14, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, B.; Bataille, E.; Hardouin, J.-B. validscale: A command to validate measurement scales. Stata J. 2018, 18, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kak, N.; Burkhalter, B.; Cooper, M.-A. Measuring the Competence of Health Care Providers; The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) by the Quality Assurance (QA) Project: Woodstock, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deffuant, G.; Roubin, T.; Nugier, A.; Guimond, S. A newly detected bias in self-evaluation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.; Soufi, L. Physical assessment in pharmacy practice: Perspectives from pharmacists, nonpharmacist health care providers and the public. Can. Pharm. J. 2021, 154, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfik, E.H.; El-Sayed, N.M. Effect of Community Engagement on Acquired Teamwork Skills of Nursing Students. Int. J. Community Health Nurs. 2018, 1, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel, C.M.M.; Alumno, M.C.; Alcantara, M.K. Community Immersion: It’s Effect on the Lifelong Learning Skills of NSTP Students. Innovations 2024, 76, 443–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, I.; Mehta, K. Engaging Faculty across the Community Engagement Continuum. J. Public Scholarsh. High. Educ. 2016, 6, 108–123. [Google Scholar]

| Graduates (n = 103) | Co-Workers (n = 77) | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 22 (21.4) | 24 (31.2) |

| Female | 81 (78.6) | 53 (68.8) |

| Age (yrs) | ||

| 20–29 | 101 (99.0) | 37 (48.1) |

| 30–39 | 1 (0.9) | 29 (37.7) |

| 40–49 | - | 10 (12.9) |

| >50 | - | 1 (1.3) |

| Graduation year | ||

| Class 2015 | 23 (22.3) | - |

| Class 2016 | 33 (32.0) | - |

| Class 2017 | 47 (45.6) | - |

| Co-workers highest education | ||

| 5-year pharmacy curriculum | - | 29 (37.7) |

| 6-year PharmD curriculum | - | 41 (53.2) |

| Master’s degree | - | 6 (7.8) |

| Current workplace a | ||

| Public hospital | 85 (82.5) | 69 (89.6) |

| Private hospital | - | 1 (1.3) |

| Community pharmacy | 17 (16.5) | 14 (18.2) |

| Pharmaceutical company | 1 (0.9) | - |

| Responsible for primary care pharmacy | 39 (38.2) | 45 (59.2) |

| Roles of primary care pharmacy a | ||

| Consumer health protection in community | 11 (15.5) | 22 (33.9) |

| Home visit | 17 (23.9) | 23 (35.4) |

| Medicine dispensing and managing medicine supply in primary care center | 30 (42.3) | 36 (55.4) |

| Competencies | Mean | SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home visit skills | |||

| Advice about medicine | |||

| Involve in home visit (n = 17) | 4.7 | 0.5 | 0.018 |

| Not involve in home visit (n = 54) | 4.3 | 0.6 | |

| Perform basic physical examination | |||

| Work in community pharmacy (n = 17) | 3.8 | 0.1 | 0.011 |

| Not work in community pharmacy (n = 86) | 3.4 | 0.7 | |

| Identify drug related problems | |||

| Work in community pharmacy (n = 17) | 4.4 | 0.6 | 0.035 |

| Not work in community pharmacy (n = 86) | 3.9 | 0.7 | |

| Solve drug related problems | |||

| Male (n = 22) | 4.2 | 0.7 | 0.048 |

| Female (n = 81) | 3.9 | 0.6 | |

| Work with multidisciplinary team to provide home visit | |||

| Male (n = 22) | 3.9 | 0.9 | 0.043 |

| Female (n = 81) | 3.4 | 0.9 | |

| Responsible for primary care pharmacy (n = 39) | 3.8 | 0.9 | 0.004 |

| Not responsible for primary care pharmacy (n = 63) | 3.3 | 0.9 | |

| Involve in consumer health protection (n = 11) | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.031 |

| Not involve in consumer health protection (n = 60) | 3.5 | 0.9 | |

| Involve in home visit (n = 17) | 4.2 | 0.8 | 0.001 |

| Not involve in home visit (n = 54) | 3.4 | 0.9 | |

| Involve in medicine dispensing and managing medicine supply in primary care (n = 30) | 3.9 | 0.9 | 0.026 |

| Not involve in medicine dispensing and managing medicine supply in primary care (n = 41) | 3.3 | 0.9 | |

| Personal characters | |||

| Building good relationships with the community | |||

| Work in community pharmacy (n = 17) | 4.4 | 0.6 | 0.046 |

| Not work in community pharmacy (n = 86) | 4.0 | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saramunee, K.; Srirawatra, C.; Buaban, P.; Chaiyasong, S.; Phimarn, W. Primary Care Pharmacy Competencies of Graduates from a Community-Focused Curriculum: Self- and Co-Worker Assessments. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050139

Saramunee K, Srirawatra C, Buaban P, Chaiyasong S, Phimarn W. Primary Care Pharmacy Competencies of Graduates from a Community-Focused Curriculum: Self- and Co-Worker Assessments. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(5):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050139

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaramunee, Kritsanee, Chakravudh Srirawatra, Pathinya Buaban, Surasak Chaiyasong, and Wiraphol Phimarn. 2025. "Primary Care Pharmacy Competencies of Graduates from a Community-Focused Curriculum: Self- and Co-Worker Assessments" Pharmacy 13, no. 5: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050139

APA StyleSaramunee, K., Srirawatra, C., Buaban, P., Chaiyasong, S., & Phimarn, W. (2025). Primary Care Pharmacy Competencies of Graduates from a Community-Focused Curriculum: Self- and Co-Worker Assessments. Pharmacy, 13(5), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13050139