Abstract

(1) Background: Patient-centered care for individuals with breast cancer requires multidisciplinary cooperation to ensure the appropriate use of medication and prevent medication-related problems. Pharmaceutical care has been associated with improved adherence in breast cancer management, a factor linked to patient outcomes and mortality. This study aims to summarize and explore the provision and utilization of pharmaceutical services for breast cancer patients by pharmacists. (2) Methods: A scoping review was performed to assess the pharmacist’s role in providing pharmaceutical services for patients with breast cancer. A comprehensive review of four databases (PubMed, Ovid Embase, Ovid International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, and Scopus) was completed between 1 January 2012 and 8 April 2025 according to PRISMA-ScR framework. (3) Results: A total of 46 articles met the inclusion criteria, which included RCTs, observatory studies, cohort studies, and reviews. Findings suggest that both clinical and community pharmacists play an important role in prevention, management, and education for breast cancer patients. (4) Conclusions: Pharmacists can improve health outcomes by providing pharmaceutical service in breast cancer care. Optimizing interventions, expanding services, and evaluating long-term cost-effectiveness is needed in the future.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) has become the most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide [1] with an estimated 2.3 million new cases in 2020 [2]. Although treatment varies according to the subtype of breast cancer, some patients receive maintenance pharmaceutical therapy at home for years, similarly to those with chronic disease like diabetes [3,4,5]. For example, adjuvant endocrine therapy for estrogen-positive breast cancer commonly lasts for 5–10 years [5]. This epidemiological landscape, characterized by a high incidence, the need for long-term treatment, and low adherence rates poses a significant challenge [6]. Patient adherence is key to successfully administered long-term treatment. Medication education, which can improve compliance, from a readily accessible source such as a local pharmacists could and has been shown to be beneficial in improving health outcomes [7].

Previous studies have confirmed the necessity and benefit of services provided by pharmacists [8,9]. Such examples include the identification of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) as part of pharmacists’ monitoring plan [10], and their ability to create personalized medication treatment plans for the geriatric high-risk population at different physiological or pathological stages to manage medication side effects and further ensure the best therapeutic outcomes [11]. Mekonnen [9] reported that pharmacist-led medication reconciliation during hospital admission and care transitions significantly reduces ADR-related readmissions and emergency department revisits for all causes. By communicating with doctors regarding therapy adjustment recommendations, pharmacists can improve the prognosis and quality of life (QOL) of patients [12]. Medication reconciliation and suggested adjustments of treatment plans from pharmacists ensure avoidance of harmful drug–drug interaction (DDI) and therapy side effects [13]. To facilitate patients’ active involvement in therapy and enhance medication adherence, pharmacists can counsel patients on symptoms and signs that facilitate hospital visits, prompt patients to take medicine as prescribed, encourage patients to adopt a better lifestyle, and have a basic understanding of disease and medicine [14,15,16]. Pharmacists can assist patients closely with treatment participation, aid in new therapy initiation, and ultimately improve the therapy effectiveness and adherence [17]. Thus, pharmacists are an important part of the multidisciplinary team [18].

Despite the array of research conducted on BC treatment, the battle against malignancy still faces challenges. For example, there is high heterogeneity in response to medication among patients with different BC subtypes, which could be linked to suboptimal matching of treatment medication [19]. Side effects of BC anticancer therapy, as well as the withdrawal of BC treatment, can be severe and can include nausea, vomiting, alopecia, fatigue, and premature menopause, leading to a significant decrease in QOL [20]. Long-lasting comprehensive monitoring and ongoing evaluation of anti-tumor medication from a pharmacist can be essential for effective treatment and QOL. Pharmacists, especially those in a community setting, can also offer comprehensive medical support for BC prevention, like education and training on breast self-examination (BSE) and medication counseling [21]. It is worth noting that community pharmacists do not have the ability and authority to review the prescription of antineoplastic drugs under China’s current policy. However, the development of direct-to-patient (DTP) pharmacy provides a potential space for community pharmacists to aid in the management of antineoplastic drugs. With emerging opportunities such as these, a critical review of the integrative and individual pharmaceutical services that serve and benefit BC patients can be of great benefit in the battle against malignancy. Thus, the objective of this scoping review was to explore pharmacists’ interventions that could improve pharmaceutical care for BC patients across all pharmacy settings (community, clinic, and hospital), exploring the similarities and differences in those settings and if/how cooperation with pharmacists could benefit BC patients.

2. Materials and Methods

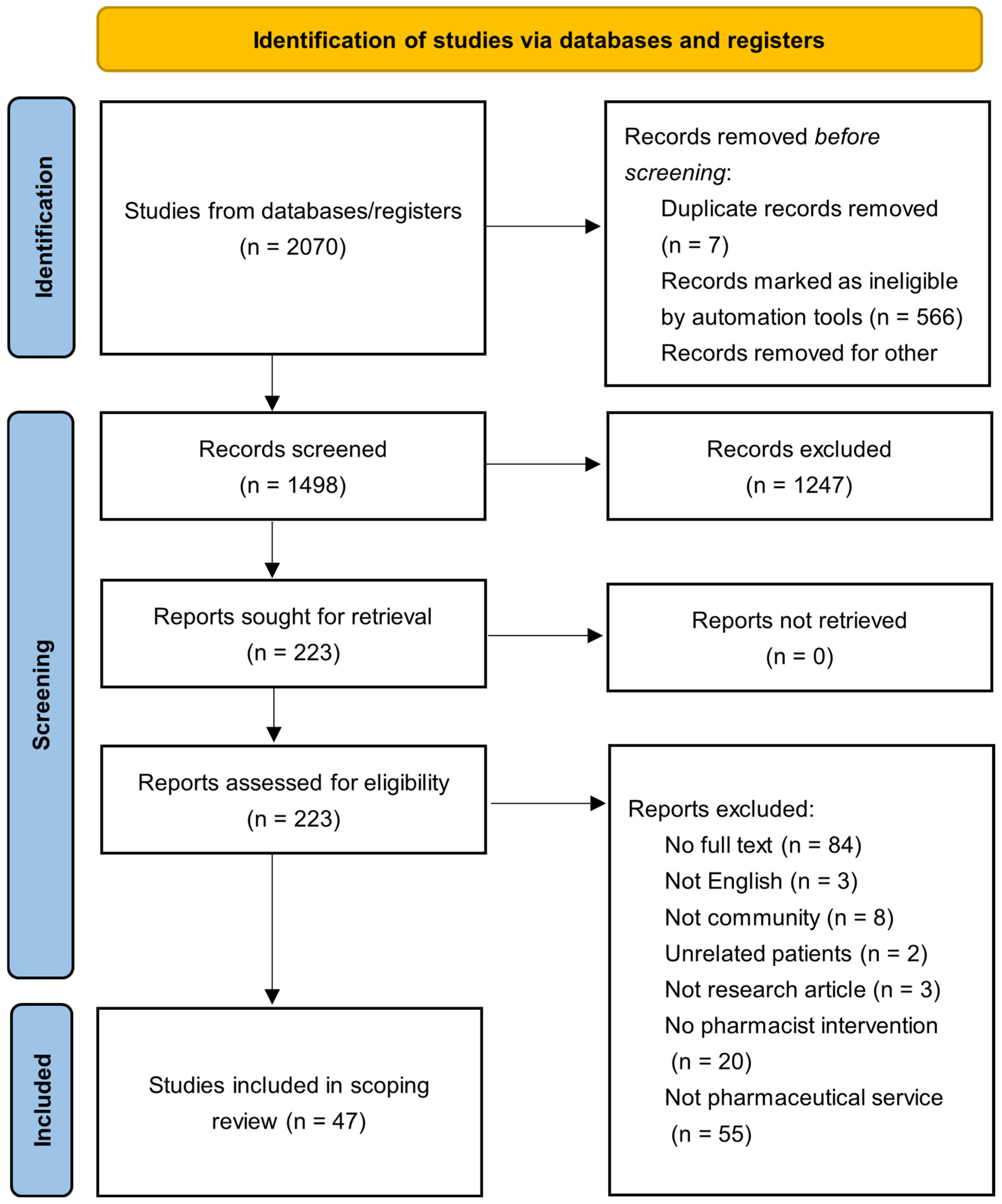

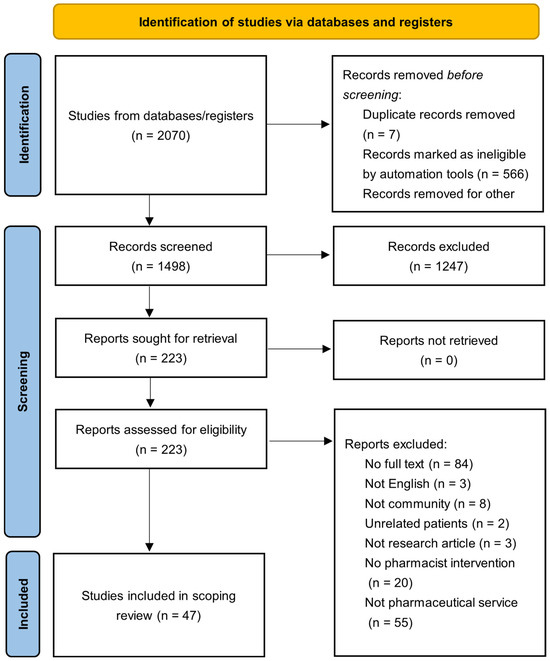

A search strategy was developed to identify studies that included pharmaceutical care for BC patients and the role(s) that pharmacists have in the BC treatment space. To identify pharmacy practice related to BC patients in clinic, hospital, and community pharmacies, the keywords pharmacist/s, pharmacies, pharmacy, pharmaceutical care, pharmaceutical service/s, and breast neoplasms [mesh] were used. The strategy was equally applied to PubMed (MEDLINE), Ovid Embase, Ovid International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, and Scopus from 2012 to 2025 (Appendix A.2). The gray literature was not searched. Search keywords were also applied to Google Scholar, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA). The study selection process, including identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion stages, is illustrated in Figure 1 accordance to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Appendix A.1) [22]. The protocol was retrospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) on 11 July 2025 (Available at: http://osf.io/wzqyp/).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for study selection.

Two authors independently scanned the title and abstract to evaluate relevance. The inclusion criteria consist of the following: (1) interventions conducted by a clinical or community pharmacist; (2) articles focusing their research on BC patients or pharmacists engaged in providing services related to BC; (3) all study types, with Chinese and English articles accepted, excluding those without full texts. Recommendations and guidelines were excluded. Reference lists of all included studies were searched for potentially relevant studies.

Retrieved articles were uploaded and managed using Covidence (www.covidence.org, accessed on 25 April 2025), including screening and data extraction. The automatic de-duplication function in Covidence was used and verified by reviewers. Features collected from each article, where applicable, included the country the study was conducted in, study type, pharmaceutical intervention, endpoint evaluation, clinical outcomes, and patients’ subjective and objective experiences with pharmaceutical care.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

After a review of all databases and reference lists, 2070 articles were identified. After the removal of duplicates, 1499 articles remained. After two rounds of review, 46 articles met the inclusion criteria. In total, 67% of the articles focused on interventions from pharmacists in a hospital or clinical setting (n = 31), with nineteen different countries represented across the included articles. Five RCTs were identified, with 82.6% of the articles being observatory or cohort studies (n = 38). A total of 87% of the articles discussed detailed pharmaceutical interventions (n = 40), and seven studies interviewed BC patients or community pharmacists on attitudes or knowledge. There are five articles (11%) that mentioned virtual pharmaceutical care (e.g., online, phone, etc.). Studies providing only subjective evidence: 13 out of 46 (28.3%). Studies providing objective evidence: 33 out of 46 (71.7%).

3.2. Pharmaceutical Service in Hospital or Clinic

Results from the 31 articles that were specific to pharmaceutical services in hospital or clinical settings indicate that pharmacists play a crucial and multi-faceted role in various aspects of BC care. A summary of all these articles is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies focused on hospital or clinic pharmacists (n = 31).

3.2.1. Medication Therapy Management (MTM)

MTM was a focus in four studies. The role of clinical pharmacists in MTM included reviewing medications, comorbidities, referring to multidisciplinary teams, education, and the identification of toxicity. All four studies showed positive change on clinical outcomes [24,30,44,53]. There was only one study that mentioned the billing of MTM, in which a ‘no charging standard’ was established [44].

3.2.2. Patient Education and Adherence Improvement

Nearly half of these hospital- or clinic-based studies (n = 14) discussed the application and benefit of patient education. Verbal expression [39], written documents [40,52], and online platforms [29] were effectively used to offer knowledge of BC and its affiliated treatments. The education provided by pharmacists encompasses the following aspects: medication tables [40], prevention and management of ADRs [29,42], information on BC, the necessity of therapy [32,34,46], interventional strategies for anticipated adverse events [36,42], medication guide [29,51], handling of missed doses [34], lifestyle recommendations (dietary advice) [51,52], and pharmaceutical counseling [27,50].

3.2.3. Optimization of Drug Therapy

Medication reconciliation [23,25,45,50], multidisciplinary collaboration and care coordination [26,31,38,45], deprescribing, and prevention of DDI [32,35,43,47] were commonly found among these hospital- and clinic-based articles. These articles showcased how pharmacists in these settings were able to identify potential and current DRPs, document changes in medicine, suggest alternative treatment plans when necessary, and keep the doctor informed in a timely manner [31]. The result of laboratory examinations was also part of a shared pharmacy care model [28]. The management of symptoms and ADRs was shown to enhance the adherence of BC patients and improve the safety of the treatment used [27].

3.2.4. Quality of Life and Humanistic Outcomes

These articles also showed improvement in QOL [32,46], patients’ satisfaction [37], and humanistic outcomes such as patient mobility and physical function, activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, pain and discomfort management, and negative emotions [38].

3.3. Pharmaceutical Service in Community

Fifteen articles that were specific to pharmaceutical services in a community setting were identified. A summary of all these articles is listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of studies focused on community pharmacists (n = 15).

3.3.1. Health Education and Prevention

In total, 60% of these identified articles engaged community pharmacists in the delivery of education to BC patients (n = 9). Examples included disease education [57], BSE [59], breast examination and assessment [55], health education booklets [65], and enhancing patients’ understanding of the rehabilitation process [68]. Prevention strategies shared by pharmacists included education on BC symptoms, risk factors, methods of detection and diagnosis, prognosis, and severity of breast cancer [59,65].

3.3.2. Medication-Related Services

These articles also showcased community pharmacists offering online platforms for comprehensive medication-related services [57], cooperation with medical teams to optimize therapy plans [54], consistent follow-up [56], management of AEs [60,63], and extended services and community care [60,62,67,69]. These articles also showed that pharmacists in community settings intervene in cases of AEs, DDIs, and side effects, embrace the identification of potential adverse reactions [54], manage side effects [63], and report AEs. Other forms of care provided by community pharmacists in these articles included counseling around weight management and lifestyle modification [62], the evaluation of dosage adjustment [67], and implementing medication delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic [60].

3.3.3. Attitude Towards Pharmaceutical Services in Community

Two articles captured the attitude towards pharmaceutical services in communities [58,61]. The lack of knowledge about cancer, the focus on healthcare issues other than cancer, and the perceived role of pharmacy staff were identified as the greatest barriers preventing staff from providing comprehensive consultations to cancer patients/survivors [58]. It was suggested that incentives are used to showcase the value of pharmacists’ roles in caring for BC patients [61].

4. Discussion

This scoping review synthesized evidence from 31 studies on hospital/clinic pharmacists and 15 on community pharmacists, comprehensively elucidating their roles in delivering pharmaceutical services to BC patients. The findings highlight the far-reaching benefits of pharmacist-driven and pharmacist-engaged interventions and underscore the crucial significance of MTM in breast cancer care.

4.1. Benefits of Pharmacist Services for Breast Cancer Patients

Pharmacists are integral in enhancing medication adherence among BC patients through strategies such as personalized counseling, reminder systems, and educational materials. These strategies can enhance adherence, directly impacting treatment effectiveness and patient prognosis. For example, the included clinical pharmacist-led patient education and follow-up intervention conducted in Iraq notably optimized breast cancer patients’ adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy [40]. This outcome was also found in an included Canadian study, where pharmacist-provided pharmaceutical care, including medication counseling and follow-up, increased patients’ adherence to CDK4/6 inhibitors [56]. Supporting adherence can help avoid treatment failure and disease recurrence, highlighting the importance of this outcome.

Pharmacists contribute significantly to augmenting patients’ knowledge about breast cancer and its treatment. For example, in an included study conducted in Egypt, it was demonstrated that community pharmacists’ teaching significantly increased knowledge of breast cancer prevention and preventive actions [59]. Ramzi et al. found that community pharmacists in a Palestinian context played a role in warning people about breast cancer risks and prevention methods [64]. Well-informed patients are more likely to actively engage in their treatment, make well-informed decisions, and adhere to treatment plans.

Pharmacists play a key role in managing the side effects of breast cancer treatments. Colombo et al.’s systematic review in Brazil indicated that pharmacist interventions, mainly centered on educating and counseling patients on adverse event management, could improve outcomes in cancer outpatients [54]. In the Netherlands, Selma et al. found that women on adjuvant endocrine therapy desired more side effect management education from pharmacists [63]. By providing information on side effect prevention and management, pharmacists can enhance patients’ quality of life during treatment.

Hospital and clinic pharmacists are essential in optimizing drug therapy. A.C. Ferracini’s cross-sectional, prospective study in Brazil showed that clinical pharmacist reviews of patients’ medical records and prescriptions, along with interventions when prescribing errors were detected, avoided significant prescribing errors [25]. In Spain, Carmen’s prospective study demonstrated that hospital pharmacists’ systematic review of treatment, detection of interactions, and recommendations reduced medication-related problems and optimized drug therapy [47]. This ensures that patients receive safe, effective, and appropriate medications.

Pharmacist-led interventions have a positive impact on patients’ quality of life. Avinash et al.’s study in India showed that the provision of oncology pharmacist services led to an improvement in QALY [38]. In Japan, Kazuhide’s cohort study found that personal counseling by pharmacists improved the treatment environment and enhanced the quality of life of breast cancer patients [42]. By addressing various aspects of treatment, such as medication-related issues, side effect management, and patient education, pharmacists contribute to a better overall quality of life for patients.

4.2. Significance of Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Services in Breast Cancer Care

In the realm of breast cancer care, MTM services hold significant importance. These services foster multidisciplinary collaboration, as evidenced by Pedro’s study in Brazil, which showed that oncology-focused MTM involved referrals to multidisciplinary team members. In the United States, Koshy’s research on the Cancer and Aging Interdisciplinary Team (CAIT) clinic model further demonstrated the crucial role of collaboration between pharmacists and other healthcare providers [49]. As part of the multidisciplinary team, pharmacists bring their specialized medication therapy knowledge, which complements the skills of oncologists, nurses, and other professionals, resulting in more comprehensive patient care. MTM services are also essential for identifying and resolving DRPs. Jianping Zhang’s retrospective study in China on an independent anti-neoplastic MTM system revealed that it effectively facilitated the identification and resolution of DRPs, with a particular emphasis on improving medication adherence [30]. Minoh’s retrospective analysis in a Korean hospital found that the collaborative deprescribing service within the Consultation-Based Palliative Care Team (CB-PCT) was successful in identifying and addressing medication-related issues. By detecting and resolving DRPs, pharmacists can prevent adverse drug events, optimize drug therapy, and enhance patient safety [45]. Moreover, MTM services enable tailored, patient-centered care. Huijie’s study in China on integrated pharmacy services indicated that professional pharmacists, as part of a multidisciplinary team, enhanced compliance and improved cancer treatment outcomes through personalized care [29]. In Switzerland, Carole Bandiera’s RCT on community pharmacists’ medicine management for breast cancer patients, which involved monthly motivational interviews to monitor adherence to palbociclib, serves as an excellent example of personalized care [66]. Tailored care considers patients’ individual needs, preferences, and circumstances during treatment, leading to better treatment outcomes and higher patient satisfaction. Finally, MTM services provided by pharmacists can help alleviate the shortage of oncology providers. Elaine’s observational study in a Canadian hospital showed that integrating pharmacists into a shared-care model reduced the number of ambulatory patient visits for oncologists [28]. By leveraging pharmacists’ medication expertise, healthcare systems can better manage the growing number of breast cancer patients, ensuring that patients receive timely and appropriate care.

4.3. Comparison Between Hospital and Community Pharmacists in Breast Cancer

Pharmacists who operate primarily within hospital or clinic settings (also known as hospital pharmacists) have their services directly integrated into the inpatient and outpatient treatment processes. In the studies of Pedro in Brazil and Avinash in India, they worked closely with on-site oncology teams, having immediate access to patients’ medical records, test results, and treatment plans [24,38]. This setup allows in-depth, real-time patient care but is restricted to the hospital’s patient population. Community pharmacists, conversely, offer services in community pharmacies, which are more accessible to the public. Xie Chengsheng’s study in China used a WeChat-based platform to extend services to cancer patients outside the hospital, reaching those who may not frequently visit a hospital [57]. Community pharmacists can interact with patients in their daily lives, facilitating long-term follow-up and continuous care. Hospital pharmacists concentrate on aspects like MTM, the prevention and resolution of DRPs, and ensuring medication safety and efficacy. In a study by A.C. Ferracini in Brazil, they reviewed patients’ medical records and prescriptions to detect and correct prescribing errors [25]. They also play a significant role in multidisciplinary teams. Based on our findings, community pharmacists focus more on health education and preventive care when it comes to BC (Table 3). In Egypt, Osama et al. educated females about breast cancer prevention [59]. They also assist with medication adherence and provide basic side-effect management counseling, though to a lesser extent than hospital pharmacists. For example, Selma et al. in the Netherlands found that women desired more side effect management education from community pharmacists [63]. Hospital pharmacists customize their services based on the complex medical conditions of in-patient and out-patient breast cancer patients. Kazuhide’s cohort study in Japan provided personalized counseling on expected adverse events and correct medication use for supportive therapy [42]. They often handle acute and severe cases, coordinating with other medical staff to optimize treatment plans. Current studies show cooperation between community pharmacists and hospital pharmacists, which reveals a new approach, to ensure BC patient receive a full-process service [67,69].

Table 3.

Comparison between the community pharmacist and the clinical pharmacist.

4.4. Challenges of Community Pharmacists’ Medication Therapy Management for Breast Cancer Patients

Community pharmacists may face challenges due to limited resources, such as restricted access to comprehensive patient medical records and advanced monitoring tools. Compared to hospital pharmacists, they may also have less in-depth training in oncology-specific MTM. Nazri et al.’s review in Malaysia indicated that although community pharmacists have potential extended services, the lack of specialized training might limit their ability to provide high-quality oncology care. BC patients have diverse needs, and some may have complex medical conditions and comorbidities. Community pharmacists may find it difficult to handle complex cases without the immediate support of a multidisciplinary team, as available in hospitals. For example, Selma et al. in the Netherlands found that women on adjuvant endocrine therapy have specific side effect management needs that community pharmacists may struggle to fully address. Integrating community pharmacy services into the broader healthcare system can be challenging, because economic evaluation (cost–benefit ratio) is awaiting further research [37,69]. There may be limited communication and collaboration channels between community pharmacists and hospital-based healthcare providers. Community pharmacist used email to send reports on evaluations to hospitals, which may not be timely [67]. Strengthening timely information sharing between community pharmacists and medical service providers in hospitals or clinics may be the potential direction for pharmacists to better participate in BC management in the future. This can result in gaps in patient care, such as inconsistent treatment information and a lack of coordinated follow-up. Ensuring the seamless transfer of patient information between hospitals and community pharmacies remains a hurdle to providing comprehensive care for breast cancer patients.

4.5. Limitations

Although we searched multiple databases (e.g., PubMed, Scopus, Ovid Embase), we only examined articles written in English and Chinese, which may have led to language bias and the exclusion of relevant findings from other regions. Gray literature papers and preprints were excluded. This study included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies, which broadened perspectives, but methodological heterogeneity hindered the unified integration of topics. This methodology was appropriate for our objective of mapping existing evidence; however, scoping reviews inherently emphasize breadth over depth, which limits detailed evaluation of intervention effectiveness or comparative outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, pharmacists play a pivotal role in providing pharmaceutical services to breast cancer patients. Their services offer numerous benefits for therapy and health outcomes, and MTM services are of great significance. However, to further optimize these services, future research should focus on improving pharmacist-led interventions, expanding their reach, and evaluating their long-term cost- effectiveness in BC care. In addition, the quantity and quality of services provided by community pharmacists are far less than those provided by clinical pharmacists, and many community pharmacists are not too active in providing professional services for BC. Therefore, future research on the BC pharmaceutical service management system, while also considering economic factors such as cost-effectiveness and pharmacist revenue to guide the further development of community pharmacists and evaluate their healthcare and economic benefits, may help community pharmacists and clinical pharmacists complement each other and provide the most comprehensive services for patients.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to this scoping review as follows: Y.P. and R.H. jointly conceptualized the research question, designed the search strategy, screened articles, extracted data, synthesized findings, and drafted and revised the manuscript, sharing equal contributions as first co-authors; F.C. developed and implemented the search protocol, conducted quality assessment, and contributed to the methodology; S.V. extracted data and revised the manuscript; Y.H. focused on data analysis, developed the coding framework, conducted statistical analyses, visualized data, and contributed to the Section 4; Y.Z. handled results and the Section 4, ensured reporting compliance, coordinated with editors, managed correspondence, and supervised manuscript formatting; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and take full responsibility for the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data was obtained from PubMed (MEDLINE), Ovid Embase, Ovid International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to April 2025), and Scopus (2012 to 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hung Nguyen and Caitlin Carter from the University of Waterloo School of Pharmacy for their guidance on publication researching.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BC | Breast cancer |

| ADR(s) | Adverse drug reaction(s) |

| DDI | Drug–drug interaction |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| BSE | Breast self-examination |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| MTM | Medication therapy management |

| CMM | Comprehensive medication management |

| OHT | Oral hormonal therapy |

| QALYs | Quality-adjusted life years |

| ER | Emergency room |

| DRP | Drug-related problem |

| CSI | Clinically significant interactions |

| CDTM | Collaborative drug therapy management |

| CAIT | Cancer and Aging Interdisciplinary Team |

| CB-PCT | Consultation-Based Palliative Care Team |

| EPR | Electronic patient record |

| AET | Adjuvant endocrine therapy |

| CDK4/6i | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor |

| COVID-19 | Corona Virus Disease 2019 |

| HFS | Capecitabine-related hand–foot syndrome |

| AEs | Adverse events |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

PRISMA-ScR framework Table.

Table A1.

PRISMA-ScR framework Table.

| Section | Item | Prisma-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 1–2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 2 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 3 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 2–3 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 2–3 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 2 |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 2–3 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 3 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 3 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | (-) |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 4 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 4 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 4–14 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | (-) |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 4–15 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 9–10,14–15 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 15–18 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 18 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 19 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 19 |

Appendix A.2

PubMed(MEDLINE):

(pharmacists[mesh] OR pharmacies[mesh] OR pharmaceutical services[mesh] OR practice patterns, pharmacists’[mesh] OR pharmacist*[tiab] OR pharmacy[tiab] OR pharmacies[tiab] OR “pharmaceutical care”[tiab] OR “pharmaceutical service*”[tiab]) AND (breast neoplasms[mesh] OR “breast cancer”[tiab:~2] OR “breast neoplasm”[tiab:~2] OR “breast neoplasms”[tiab:~2] OR “breast carcinoma”[tiab:~2] OR “mammary cancer”[tiab:~2] OR “breast tumor”[tiab:~2] OR “breast tumors”[tiab:~2] OR “breast tumour”[tiab:~2] OR “breast tumours”[tiab:~2] OR “ductal carcinoma in situ”[tiab] OR “invasive ductal carcinoma”[tiab] OR “lobular carcinoma in situ”[tiab] OR “invasive lobular cancer”[tiab] OR “breast carcinoma in situ”[tiab]) AND English[lang] AND 2012:2025[edat]

Embase

(TITLE-ABS-KEY ((pharmacist* OR pharmacy OR pharmacies OR “pharmaceutical care” OR “pharmaceutical service*”)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (breast W/2 (cancer OR neoplasm* OR carcinoma OR tumor* OR tumour*)) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“mammary cancer” OR “ductal carcinoma in situ” OR “invasive ductal carcinoma” OR “lobular carcinoma in situ” OR “invasive lobular cancer” OR “breast carcinoma in situ”)) AND LANGUAGE (english)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2025) OR (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2024) OR (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2023) OR (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2022) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2021) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2020) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2019) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2018) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2017) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2016) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2015) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2014) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2013) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2012))

Ovid International Pharmaceutical Abstracts

- (pharmacist* or pharmacy or pharmacies or “pharmaceutical care” or “pharmaceutical service*”).ti,ab.

- (breast adj2 (cancer or neoplasm* or carcinoma or tumor* or tumour*)).ti,ab.

- (“mammary cancer” or “ductal carcinoma in situ” or “invasive ductal carcinoma” or “lobular carcinoma in situ” or “invasive lobular cancer” or “breast carcinoma in situ”).ti,ab.

- 2 or 3

- 1 and 4

- limit 5 to (english language and yr = “2012 -Current”)

Scopus

(TITLE-ABS-KEY ((pharmacist* OR pharmacy OR pharmacies OR “pharmaceutical care” OR “pharmaceutical service*”)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (breast W/2 (cancer OR neoplasm* OR carcinoma OR tumor* OR tumour*)) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“mammary cancer” OR “ductal carcinoma in situ” OR “invasive ductal carcinoma” OR “lobular carcinoma in situ” OR “invasive lobular cancer” OR “breast carcinoma in situ”)) AND LANGUAGE (english)) AND LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2025) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2024) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2023) OR (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2022) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2021) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2020) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2019) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2018) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2017) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2016) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2015) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2014) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2013) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2012))

References

- Xia, C.; Dong, X.; Li, H.; Cao, M.; Sun, D.; He, S.; Yang, F.; Yan, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, N.; et al. Cancer Statistics in China and United States, 2022: Profiles, Trends, and Determinants. Chin Med. J. 2022, 135, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, H.J.; Lacchetti, C.; Griggs, J.J. Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, 106–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, S.-A.; Gennari, A.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; Jiang, Z.-F.; Gupta, S.; Fadjari, T.H.; Tamura, K.; Mastura, M.Y.; Abesamis-Tiambeng, M.L.T.; et al. Pan-Asian Adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Staging and Treatment of Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradishar, W.J.; Moran, M.S.; Abraham, J.; Aft, R.; Agnese, D.; Allison, K.H.; Anderson, B.; Burstein, H.J.; Chew, H.; Dang, C.; et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 2022, 20, 691–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershman, D.L.; Shao, T.; Kushi, L.H.; Buono, D.; Tsai, W.Y.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Kwan, M.; Gomez, S.L.; Neugut, A.I. Early Discontinuation and Non-Adherence to Adjuvant Hormonal Therapy Are Associated with Increased Mortality in Women with Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 126, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Clark, R.; Tu, P.; Bosworth, H.B.; Zullig, L.L. Breast Cancer Oral Anti-Cancer Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review of Psychosocial Motivators and Barriers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 165, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, F. Impact of Clinical Pharmacy Services on KAP and QOL in Cancer Patients: A Single-Center Experience. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 502431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, A.B.; McLachlan, A.J.; Brien, J.-A.E. Effectiveness of Pharmacist-Led Medication Reconciliation Programmes on Clinical Outcomes at Hospital Transitions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossouo Tagne, J.; Yakob, R.A.; Dang, T.H.; Mcdonald, R.; Wickramasinghe, N. Reporting, Monitoring, and Handling of Adverse Drug Reactions in Australia: Scoping Review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023, 9, e40080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenguer, B.; La Casa, C.; De La Matta, M.J.; Martin-Calero, M.J. Pharmaceutical Care: Past, Present and Future. CPD 2004, 10, 3931–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.R.; Ramalhinho, I.; Sleath, B.L.; Lopes, M.J.; Cavaco, A.M. Probing Pharmacists’ Interventions in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachuer, C.; Perrin, G.; Chastel, A.; Aboudagga, H.; Thibault, C.; Delanoy, N.; Caudron, E.; Sabatier, B. Pharmaceutical Consultation to Detect Drug Interactions in Patients Treated with Oral Chemotherapies: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicary, D.; Hutchison, C.; Aspden, T. Demonstrating the Value of Community Pharmacists in New Zealand Educating a Targeted Group of People to Temporarily Discontinue Medicines When They Are Unwell to Reduce the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 28, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.K.; Kennedy, G.A.; Stupans, I. Pharmacist Health Coaching in Australian Community Pharmacies: What Do Pharmacy Professionals Think? Health Soc. Care Commun. 2020, 28, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, A.; Tyszka, M. Evaluating the Patient-Perceived Impact of Clinical Pharmacy Services and Proactive Follow-up Care in an Ambulatory Chemotherapy Unit. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 23, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posey, L.M. Proving That Pharmaceutical Care Makes a Difference in Community Pharmacy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2003, 43, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, S.; Pelone, F.; Harrison, R.; Goldman, J.; Zwarenstein, M. Interprofessional Collaboration to Improve Professional Practice and Healthcare Outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD000072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, R. Challenges and Future of Precision Medicine Strategies for Breast Cancer Based on a Database on Drug Reactions. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataseven, B.; Frindte, J.; Harter, P.; Gebers, G.; Vogt, C.; Traut, A.; Breit, E.; Bluni, V.; Reinisch, M.; Heitz, F.; et al. Perception of Side Effects Associated with Anticancer Treatment in Women with Breast or Ovarian Cancer (KEM-GO-1): A Prospective Trial. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3605–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, J.T.; Kennedy, D.T.; Dunn, E.C.; Wallace, W.L.; Meadows, S.L.; Cafiero, A.C. Results of a Community Pharmacy-Based Breast Cancer Risk-Assessment and Education Program. Pharmacotherapy 2001, 21, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darcis, E.; Germeys, J.; Stragier, M.; Cortoos, P. The Impact of Medication Reconciliation and Review in Patients Using Oral Chemotherapy. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 29, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Amaral, P.A.; Mendonça, S.D.A.M.; de Oliveira, D.R.; Peloso, L.J.; Pedroso, R.D.S.; Ribeiro, M.Â. Impact of a Medication Therapy Management Service Offered to Patients in Treatment of Breast Cancer. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 54, e00221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracini, A.C.; Rodrigues, A.T.; De Barros, A.A.; Derchain, S.F.; Mazzola, P.G. Breast and Gynaecological Cancer at a Brazilian Teaching Hospital. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Mendonça, S.A.M.; Filardi, A.R.; Dos Anjos, A.C.Y.; De Oliveira, D.R. Implementation and systematization of a comprehensive medication management (CMM) service delivered to women with breast cancer. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staynova, R.; Gavazova, E.; Kafalova, D. Clinical Pharmacist-Led Interventions for Improving Breast Cancer Management-a Scoping Review. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 4178–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Labelle, S.; Chan, A. Implementation and Evaluation of a Shared Care Model between Oncologists and Pharmacists for Breast Cancer Patients at a Canadian Regional Ambulatory Cancer Centre. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 30, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, H.; Zhu, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhan, Q.; Le, T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Reduced Emergency Room Visits and Improved Medication Adherence of an Integrated Oncology Pharmaceutical Care Practice in China. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 27, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, R.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xiao, M.; Hu, H.; Tang, L.; Shen, Z.; Guo, C. The Effectiveness of an Independent Anti-Neoplastic Medication Therapy Management System in Ambulatory Cancer Patients. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novosadova, M.; Filip, S.; Molnarova, V.; Priester, P.; Svecova, D. Clinical Pharmacist in Oncology Palliative Medicine: Drug Compliance and Patient Adherence. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 13, e1308–e1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrag, D.K.; Sabri, N.A.; Tawfik, A.S.; Shaheen, S.M. Evaluation of the Clinical Effect of Pharmacist Intervention: Results of Patient Education about Breast Cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Pharm. 2020, 3, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElBaghdady, N.S.; El Gazzar, M.M.; Abdo, A.M.; Magdy, A.M.; Youssef, F.A.; Sayed, K.A.; Hussein, M.M.; Megala, J.E.; Hossam Eldien, S.; Elmaboud, Z.M.; et al. Adherence to Oral Hormonal Treatment among Breast Cancer Patients in Egypt. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2024, 25, 3619–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feral, A.; Boone, M.; Lucas, V.; Bihan, C.; Belhout, M.; Chauffert, B.; Lenglet, A. Influence of the Implementation of a Multidisciplinary Consultation Program on Adherence to the First Ever Course of Oral Antineoplastic Treatment in Patients with Cancer. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 28, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenhardt, F.; Alexandre, M.; Guiu, S.; Pouderoux, S.; Beaujouin, M.; Lossaint, G.; Philibert, L.; Evrard, A.; Jacot, W. Impact of Pharmacist Consultation at Clinical Trial Inclusion: An Effective Way to Reduce Drug–Drug Interactions with Oral Targeted Therapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2021, 88, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürr, P.; Schlichtig, K.; Kelz, C.; Deutsch, B.; Maas, R.; Eckart, M.J.; Wilke, J.; Wagner, H.; Wolff, K.; Preuß, C.; et al. The Randomized AMBORA Trial: Impact of Pharmacological/Pharmaceutical Care on Medication Safety and Patient-Reported Outcomes During Treatment with New Oral Anticancer Agents. JCO 2021, 39, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liekweg, A.; Westfeld, M.; Braun, M.; Zivanovic, O.; Schink, T.; Kuhn, W.; Jaehde, U. Pharmaceutical Care for Patients with Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadela, A.; Bhikadiya, V.; Vyas, B. Impact of Oncology Pharmacist Services on Humanistic Outcome in Patients with Breast Cancer. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 28, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puspitasari, A.W.; Kristina, S.A.; Prabandari, Y.S. Effect of Pharmacist Interventions on Medication Adherence to Capecitabine in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Indones. J. Pharm. 2022, 33, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeea, I.; Saad, A.; Waleed, S.; Al-Jalehawi, A.; Kermasha, Z. The Impact of Pharmacist Intervention in Augmenting the Adherence of Breast Cancer Women to Oral Hormonal Therapy. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2023, 42, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, S.; Kamata, H.; Sugama, Y.; Demachi, K.; Ikegawa, K.; Igarashi, T.; Yamaguchi, M. Impact of Pharmacy Collaborating Services in an Outpatient Clinic on Improving Adverse Drug Reactions in Outpatient Cancer Chemotherapy. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 25, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Hori, A.; Tachi, T.; Osawa, T.; Nagaya, K.; Makino, T.; Inoue, S.; Yasuda, M.; Mizui, T.; Nakada, T.; et al. Impact of Pharmacist Counseling on Reducing Instances of Adverse Events That Can Affect the Quality of Life of Chemotherapy Outpatients with Breast Cancer. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todo, M.; Ueda, S.; Osaki, S.; Sugitani, I.; Takahashi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Makabe, H.; Saeki, T.; Itoh, Y. Improvement of Treatment Outcomes after Implementation of Comprehensive Pharmaceutical Care in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Everolimus and Exemestane. Pharmazie 2018, 73, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, J.L.; Landgraf, A.; Barnett, C.M.; Michaud, L. Evaluation of Pharmacist-Provided Medication Therapy Management Services in an Oncology Ambulatory Setting. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2012, 52, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, M.; Kim, S.; Suh, S.Y.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, I.-W.; Yoo, S.H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Oh, J.M. Consultation-Based Deprescribing Service to Optimize Palliative Care for Terminal Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, S. Effectiveness of a Developed Module in Improving Quality of Life among Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy at Institut Kanser Negara. Med. J. Malays. 2025, 80, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Martin, C.; Garrido Siles, M.; Alcaide-Garcia, J.; Faus Felipe, V. Role of Clinical Pharmacists to Prevent Drug Interactions in Cancer Outpatients: A Single-Centre Experience. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 36, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birand, N.; Boşnak, A.S.; Diker, Ö.; Abdikarim, A.; Başgut, B. The Role of the Pharmacist in Improving Medication Beliefs and Adherence in Cancer Patients. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 25, 1916–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, K.; Hamlin, P.A.; Tew, W.P.; Trevino, K.; Tin, A.L.; Shahrokni, A.; Meditz, E.; Boparai, M.; Amirnia, F.; Sun, S.W.; et al. Development and Implementation of an Interdisciplinary Telemedicine Clinic for Older Patients with Cancer—Preliminary Data. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganihong, C.J.; Singh, A.; Dimarco, R. Evaluating the Impact of a Clinical Pharmacist in Patients Receiving New Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer: Analysis of a Pilot Study. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, M.J.; Reid, J.H.; Nachar, V.R.; Benitez, L.L.; Brown, A.M.; Kraft, S.; Hough, S.; Christen, C.; Frame, D.; McDevitt, R.L. Implementation and Outcomes of a Pharmacist-Led Collaborative Drug Therapy Management Program for Oncology Symptom Management. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6505–6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.V.; Hughes, D.M.; Ko, N.Y. OPTIMAL Breast Cancer Care: Effect of an Outpatient Pharmacy Team to Improve Management and Adherence to Oral Cancer Treatment. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, e306–e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, J.M.; Ajewole, V.B.; Schneider, A.M.; Sharma, M.; Bernicker, E.H. Evaluation of the Prescribing Patterns, Adverse Effects, and Drug Interactions of Oral Chemotherapy Agents in an Outpatient Cancer Center. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 25, 1564–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, L.R.P.; Aguiar, P.M.; Lima, T.M.; Storpirtis, S. The Effects of Pharmacist Interventions on Adult Outpatients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havlicek, A.J.; Mansell, H. The Community Pharmacist’s Role in Cancer Screening and Prevention. Can. Pharm. J. CPJ 2016, 149, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marineau, A.; St-Pierre, C.; Lessard-Hurtubise, R.; David, M.-È.; Adam, J.-P.; Chabot, I. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitor Treatment Use in Women Treated for Advanced Breast Cancer: Integrating ASCO/NCODA Patient-Centered Standards in a Community Pharmacy. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 29, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Zhan, X.; Li, J.; Xia, Z.; Shen, X.; Meng, J.; Zeng, W. Design and construction of tumor pharmaceutical care system based on WeChat: Taking the whole-process management for breast cancer patients as an example. Anti-Tumor Pharm. 2023, 13, 509–514. [Google Scholar]

- Buhl, C.; Olsen, N.L.; Nørgaard, L.S.; Thomsen, L.A.; Jacobsen, R. Community Pharmacy Staff’s Knowledge, Educational Needs, and Barriers Related to Counseling Cancer Patients and Cancer Survivors in Denmark. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, O.M.; El-bassiouny, N.A.; Dergham, E.A.; Mazrouei, N.A.; Meslamani, A.Z.A.; Ebaed, S.B.M.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Sadeq, A.; Kassem, A.B. The Effectiveness of Pharmacist-Based Coaching in Improving Breast Cancer-Related Health Behaviors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 19, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larbre, V.; Romain-Scelle, N.; Reymond, P.; Ladjouzi, Y.; Herledan, C.; Caffin, A.G.; Baudouin, A.; Maire, M.; Maucort-Boulch, D.; Ranchon, F.; et al. Cancer Outpatients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Oncoral Has to Teach Us about Medical Drug Use and the Perception of Telemedicine. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 13301–13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, L.; Liswi, M.; Al-Ajlouni, R.; Shafei, D.; Fakheraldeen, R.E. Community Pharmacists’ Readiness for Breast Cancer Mammogram Promotion: A National Survey from Jordan. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 4475–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordin, N.; Hassali, M.A.A.; Sarriff, A. Actual or Potential Extended Services Performed by Malaysian Community Pharmacists, Perceptions and Barriers Towards It’s Performance: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- En-Nasery-de Heer, S.; Tromp, V.N.M.F.; Westerman, M.J.; Konings, I.; Beckeringh, J.J.; Boons, C.L.M.; Timmers, L.; Hugtenburg, J.G. Patient Experiences and Views on Pharmaceutical Care during Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawahna, R.; Awawdeh, H. Pharmacists’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Barriers toward Breast Cancer Health Promotion: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Palestinian Territories. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzykcy, K.; Nowaczyk, P.; Liwiarska, J.; Waszyk-Nowaczyk, M. Community Pharmacists’ Role in Prevention of Breast Cancer —Is It Possible? Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2024, 29, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandiera, C.; Locatelli, I.; Courlet, P.; Cardoso, E.; Zaman, K.; Stravodimou, A.; Dolcan, A.; Sarivalasis, A.; Zurcher, J.-P.; Aedo-Lopez, V.; et al. Adherence to the CDK 4/6 Inhibitor Palbociclib and Omission of Dose Management Supported by Pharmacometric Modelling as Part of the OpTAT Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, S.; Umehara, K.; Kanae, T.; Kimura, Y.; Yuta, F.; Karin, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Maeda, H.; Tomioka, N.; Watanabe, K.; et al. Usefulness of Hospital and Community Pharmacists Collaborating to Manage Capecitabine-Induced Severe Hand-Foot Syndrome in Patients with Breast Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2024, 25, 3877–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, L.; Husband, A.; Nazar, H.; Todd, A. Promoting the Early Detection of Cancer: A Systematic Review of Community Pharmacy-Based Education and Screening Interventions. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015, 39, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, A.; Azami, A.; Azami, Y.; Sugeno, T.; Yasui, A.; Gonda, K.; Tanimoto, T.; Tachibana, K.; Ohtake, T. Fukushima Outpatient Pharmacotherapy Model for Breast Cancer. JMA J. 2024, 7, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).