Adherence and Cost–Utility Analysis of Antiretroviral Treatment in People Living with HIV in a Specialized Clinic in Mexico City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measuring Adherence to ART

2.2.1. ART Adherence Follow-Up Questionnaire

2.2.2. Selection of PLwHIV to Be Surveyed

2.2.3. Consultation of Clinical Data of the Surveyed PLwHIV

2.2.4. Data Categorization and Statistical Analysis of Results

2.2.5. Logistic Regression

2.3. Cost of HIV Care

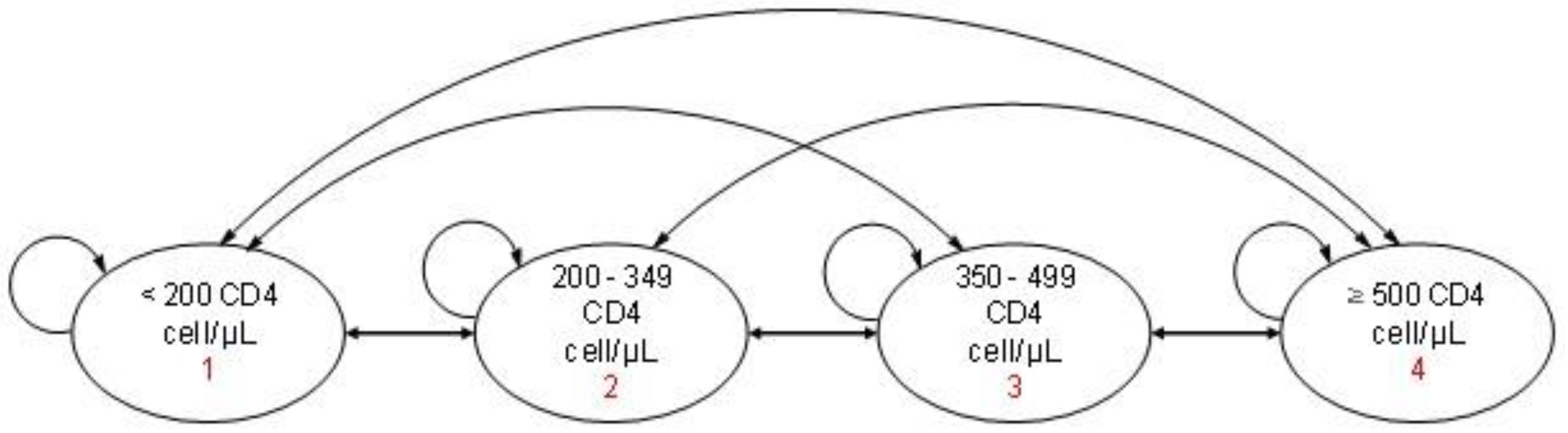

2.3.1. Economic Model

2.3.2. Model Inputs

2.3.3. Model Population

2.3.4. Costs

2.3.5. Utilities

2.3.6. Transition Probabilities

2.3.7. Monte Carlo Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of the Economic Model

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

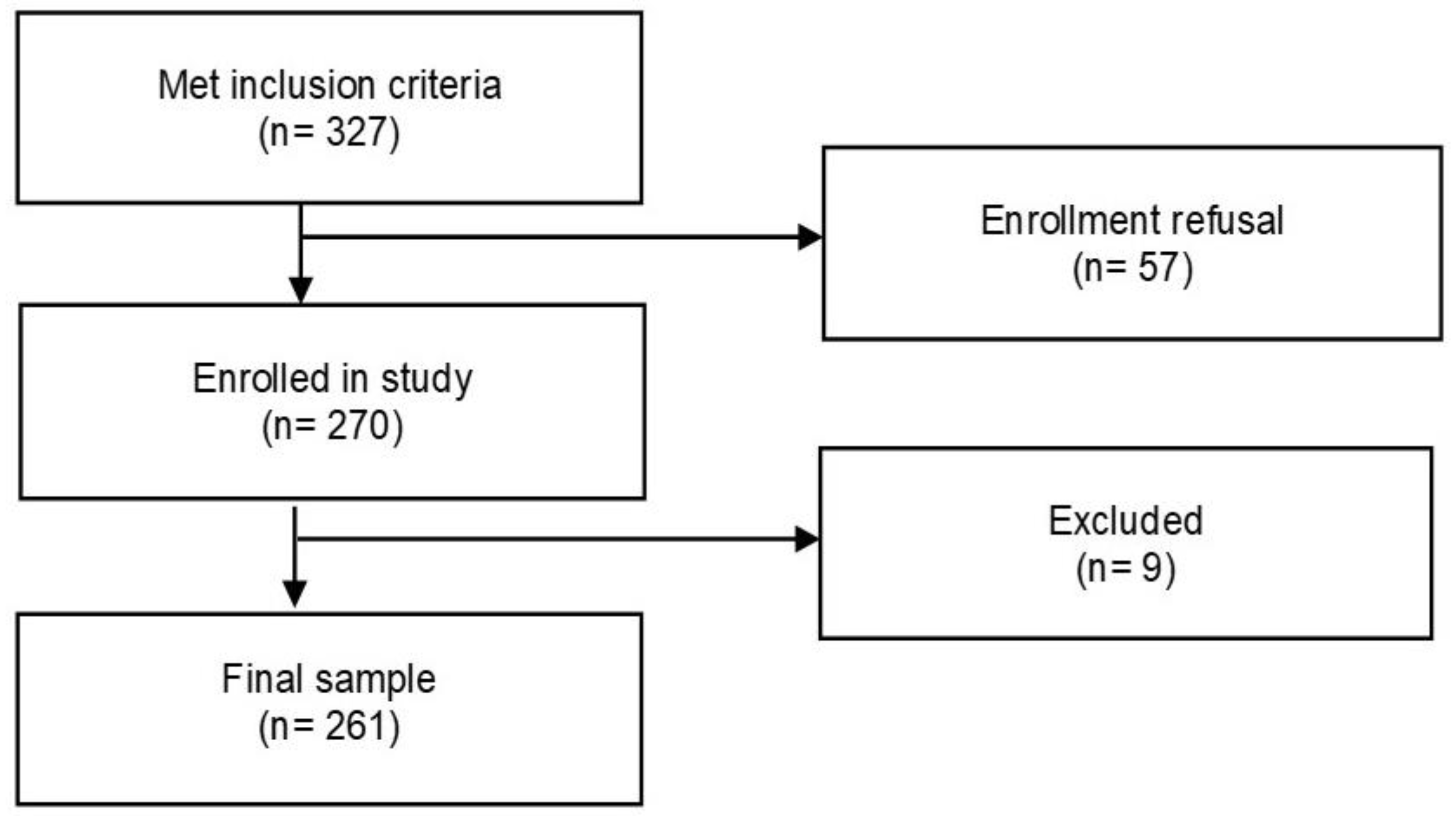

3.1. Study Sample

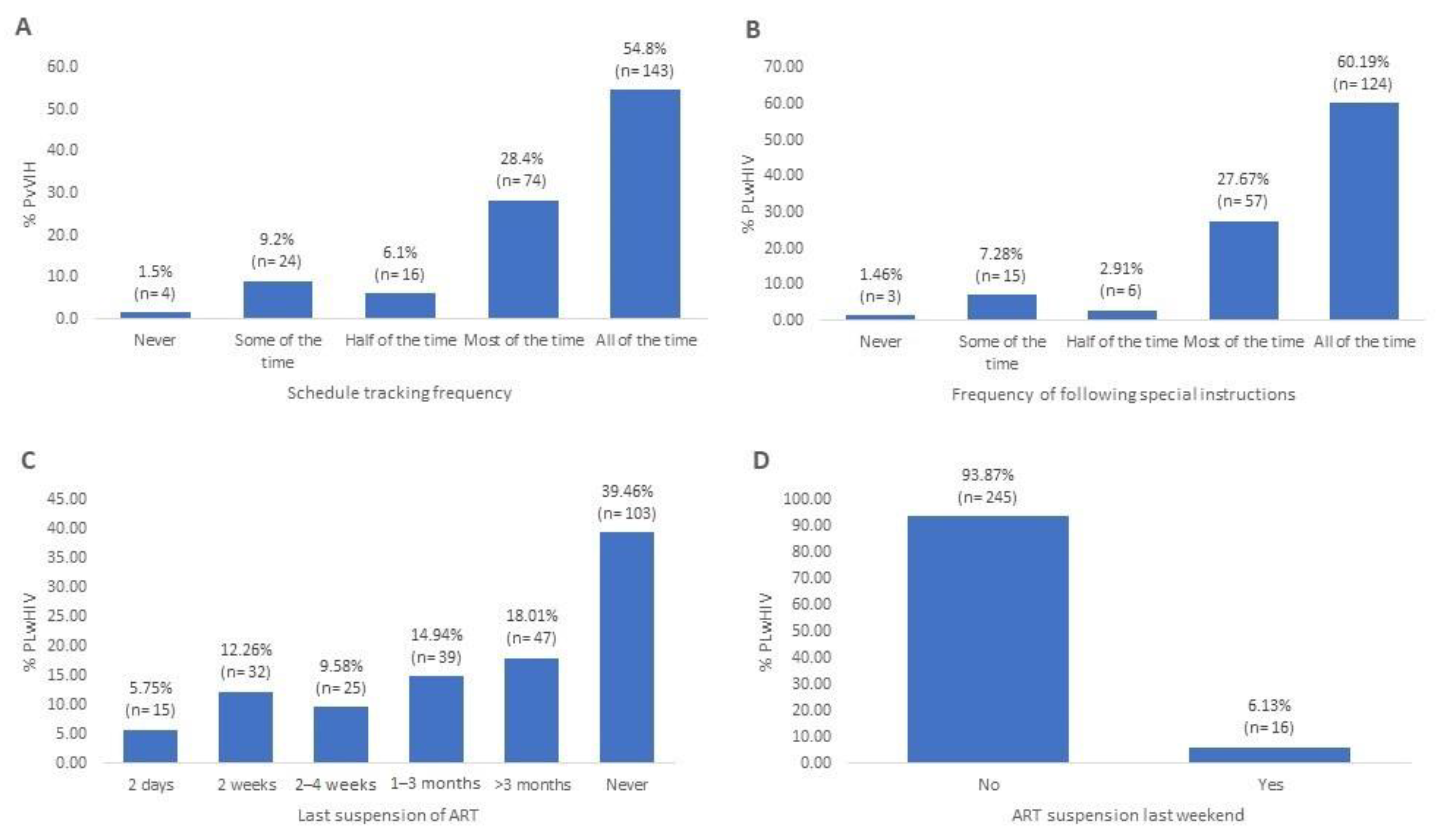

3.2. Therapeutic Adherence, Adherence Index and Causes of Non-Adherence

3.3. Factors Associated with Treatment Adherence

3.4. Analysis of Clinical Progression in the Markov Cohort

3.5. Costs of HIV Care

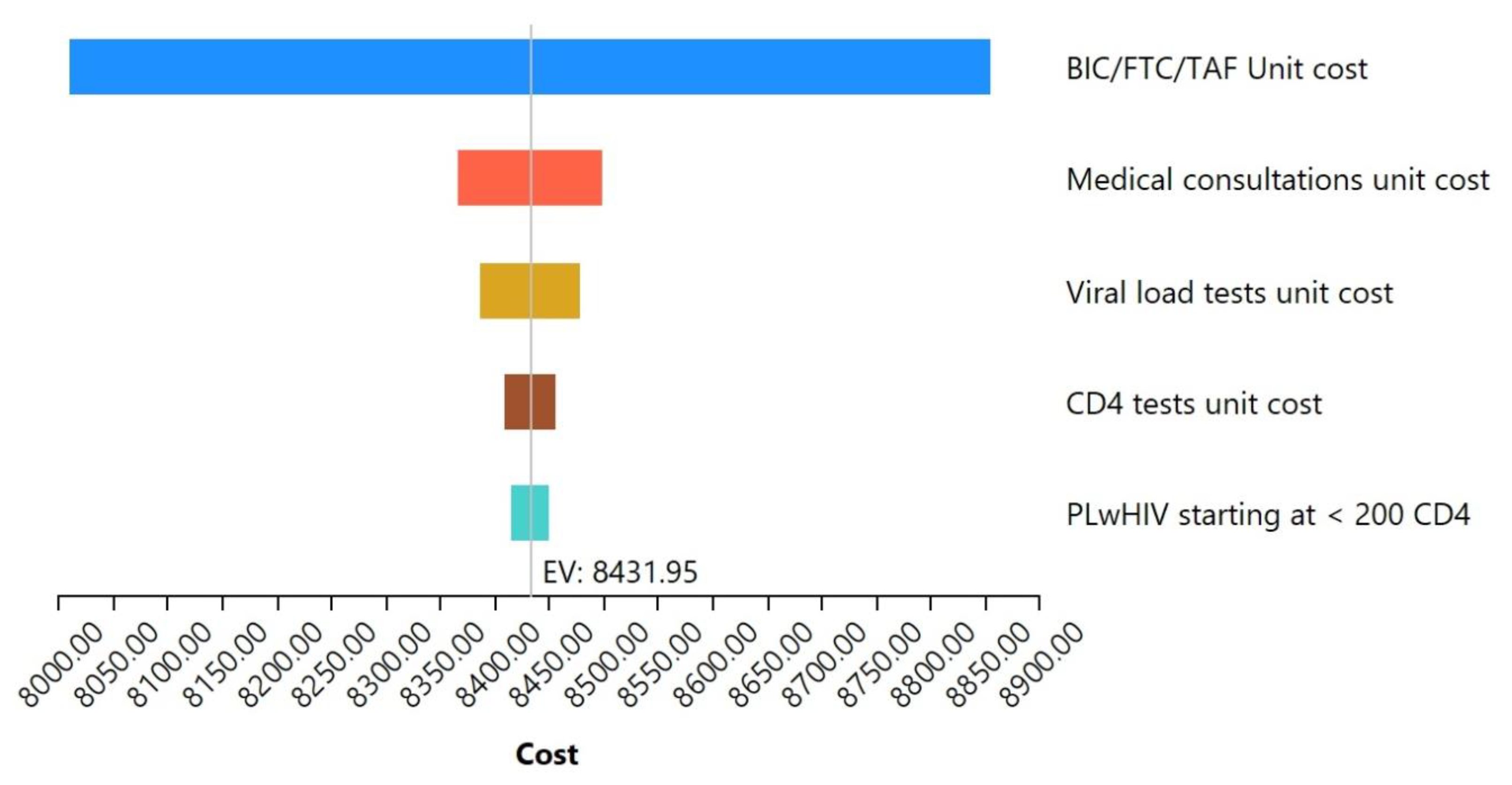

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menéndez-Arias, L.; Delgado, R. Update and Latest Advances in Antiretroviral Therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treviño-Pérez, S.C.; Vega-Yáñez, A.; Martínez-Abarca, C.I.; Estrada-Zarazúa, G.; Pérez-Camargo, L.A.; Borrayo-Sánchez, G. Atención a Personas Que Viven Con VIH En El IMSS. Rev. Méd. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2022, 60, S96–S102. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelinecentral. Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. 2023. Available online: https://www.guidelinecentral.com/guideline/41769/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- IMSS. Nuevo Esquema Antirretroviral Ofrece Diversos Beneficios a Derechohabientes Del IMSS Que Viven Con VIH. 2020. Available online: http://www.imss.gob.mx/prensa/archivo/202002/071 (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Cooke, C.E.; Lee, H.Y.; Xing, S. Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Managed Care Members in the United States: A Retrospective Claims Analysis. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2014, 20, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.D.M.; Torres, T.S.; Coelho, L.E.; Luz, P.M. Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2018, 21, e25066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México. Guía de Manejo Antirretroviral de Las Personas Que Viven Con VIH. 2022. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/712164/Gu_a_TAR_fe_erratas_2022.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Trapero-Bertran, M.; Oliva-Moreno, J. Economic Impact of HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review in Five European Countries. Health Econ. Rev. 2014, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de Vigilancia Epidemiologica de VIH. Informe Histórico Día Mundial VIH 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/informe-historico-dia-mundial-vih-2022 (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- CENSIDA. Boletín de Atención Integral de Personas con VIH/Censida. 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/964278/BOLET_N_VIH_DICIEMBRE_2024.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Clínicas Especializadas Condesa. Clínica Especializadas Condesa. 2023. Available online: https://condesa.cdmx.gob.mx/index.php (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- INEGI. Estadísticas a Propósito del día Mundial de la Lucha Contra el VIH/SIDA (1 de Diciembre). 2022. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/saladeprensa/noticia.html?id=7799 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Reynolds, N.R.; Sun, J.; Nagaraja, H.N.; Gifford, A.L.; Wu, A.W.; Chesney, M.A. Optimizing Measurement of Self-Reported Adherence with the ACTG Adherence Questionnaire: A Cross-Protocol Analysis. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2007, 46, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mudgal, S.; Thakur, K.; Gaur, R. How to Calculate Sample Size for Observational and Experiential Nursing Research Studies? Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Role of HIV Viral Suppression in Improving Individual Health and Reducing Transmission: Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Interim WHO Clinical Staging of HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS Case Definitions for Surveillance: African Region; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Melhuish, A.; Lewthwaite, P. Natural History of HIV and AIDS. Medicine 2018, 46, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitham, H.K.; Hutchinson, A.B.; Shrestha, R.K.; Kuppermann, M.; Grund, B.; Shouse, R.L.; Sansom, S.L. Health Utility Estimates and Their Application to HIV Prevention in the United States: Implications for Cost-Effectiveness Modeling and Future Research Needs. MDM Policy Pract. 2020, 5, 2381468320936219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. ACUERDO ACDO.AS3.HCT.281123/311.P.DF Dictado Por El H. Consejo Técnico, En Sesión Ordinaria Del 28 de Noviembre de 2023, Relativo a La Aprobación de Los Costos Unitarios Por Nivel de Atención Médica Actualizados Al Año 2024 y Sus Anexos 1 y 2. 2023. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5711444&fecha=14/12/2023#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. CONVENIO Modificatorio Al Convenio Específico En Materia de Transferencia de Insumos y Ministración de Recursos Presupuestarios Federales Para Realizar Acciones En Materia de Salud Pública En Las Entidades Federativas, Que Celebran La Secretaría de Salud y El Estado de Tabasco. 2024. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5742333&fecha=05/11/2024#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Emery, S.; Neuhaus, J.A.; Phillips, A.N.; Babiker, A.; Cohen, C.J.; Gatell-Artigas, J.M.; Girard, P.M.; Grund, B.; Law, M.; Losso, M.H.; et al. Major Clinical Outcomes in Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)–Naive Participants and in Those Not Receiving ART at Baseline in the SMART Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar]

- El Banco de México SIE-Mercado Cambiario. 2024. Available online: https://www.banxico.org.mx/tipcamb/tipCamMIAction.do?idioma=sp (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Consejo de Salubridad General (CSG). Guía Para La Conducción de Estudios de Evaluación Económica Para La Actualización Del Compendio Nacional de Insumos Para La Salud. 2023. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/920130/GCEEE_Enero_2023.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Banco Mundial. PIB per Cápita (US$ a Precios Actuales)–México. 2025. Available online: https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=MX (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Hunter, R.M.; Baio, G.; Butt, T.; Morris, S.; Round, J.; Freemantle, N. An Educational Review of the Statistical Issues in Analysing Utility Data for Cost-Utility Analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, A.K.; Adamson, B.J.; Saldarriaga, E.M.; Grecca, R.D.L.; Wood, D.; Babigumira, J.B.; Sanchez, J.L.; Lama, J.R.; Dimitrov, D.; Duerr, A. Finding and Treating Early-Stage HIV Infections: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of the Sabes Study in Lima, Peru. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 12, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CENSIDA. Epidemiología/Registro Nacional de Casos de VIH y Sida. 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/censida/documentos/epidemiologia-registro-nacional-de-casos-de-sida (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Secretaría de Salud. Boletín de Atención Integral de Personas Que Viven Con VIH. Día Mundial del SIDA. 2021. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/684194/BAI_DAI_2021_4.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Hernández-Romieu, A.C.; Del Rio, C.; Hernández-Ávila, J.E.; Lopez-Gatell, H.; Izazola-Licea, J.A.; Zúñiga, P.U.; Hernández-Ávila, M. CD4 Counts at Entry to HIV Care in Mexico for Patients under the “Universal Antiretroviral Treatment Program for the Uninsured Population,” 2007–2014. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azamar-Alonso, A.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.A.; Smaill, F.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Costa, A.P.; Tarride, J.E. Patient Characteristics and Determinants of CD4 at Diagnosis of HIV in Mexico from 2008 to 2017: A 10-Year Population-Based Study. AIDS Res. Ther. 2021, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbi, J.C.; Forbi, T.D.; Agwale, S.M. Estimating the period between Infection and Diagnosis Based on CD4+ Counts at First Diagnosis among HIV-1 Antiretroviral Naïve Patients in Nigeria. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2010, 4, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, G. Di Clinical Pharmacology of the SingleTablet Regimen (STR) Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide (BIC/FTC/TAF). Le Infez. Med. 2023, 31, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Taramasso, L.; Andreoni, M.; Antinori, A.; Bandera, A.; Bonfanti, P.; Bonora, S.; Borderi, M.; Castagna, A.; Cattelan, A.M.; Celesia, B.M.; et al. Pillars of Long-Term Antiretroviral Therapy Success. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 196, 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucquemont, J.; Pai, A.L.H.; Dharnidharka, V.R.; Hebert, D.; Zelikovsky, N.; Amaral, S.; Furth, S.L.; Foster, B.J. Association between Day of the Week and Medication Adherence among Adolescent and Young Adult Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boni, R.B.; Zheng, L.; Rosenkranz, S.L.; Sun, X.; Lavenberg, J.; Cardoso, S.W.; Grinsztejn, B.; La Rosa, A.; Pierre, S.; Severe, P.; et al. Binge Drinking Is Associated with Differences in Weekday and Weekend Adherence in HIV-Infected Individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 159, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Gwadz, M.; Francis, K.; Hoffeld, E. Forgetting to Take HIV Antiretroviral Therapy: A Qualitative Exploration of Medication Adherence in the Third Decade of the HIV Epidemic in the United States. SAHARA-J J. Soc. Asp. HIV/AIDS 2021, 18, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheinfil, A.Z.; Foley, J.D.; Moskal, D.; Dalton, M.R.; Firkey, M.; Ramos, J.; Maisto, S.A.; Woolf-King, S.E. Daily Associations Between Alcohol Consumption and Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Adherence Among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 3153–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellbrink, H.J.; Lazzarin, A.; Woolley, I.; Llibre, J.M. The Potential Role of Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide (BIC/FTC/TAF) Single-Tablet Regimen in the Expanding Spectrum of Fixed-Dose Combination Therapy for HIV. HIV Med. 2020, 21, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIMA. Ficha técnica de Atripla 600 mg/200 mg/245 mg comprimidos recubiertos con película. 2012. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/dochtml/ft/07430001/ft_07430001.html (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- CIMA. Ficha técnica de Biktarvy 50 mg/200 mg/25 mg comprimidos recubiertos con película. 2023. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/dochtml/ft/1181289001/FT_1181289001.html (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Zuge, S.S.; de Paula, C.C.; de Mello Padoin, S.M. Effectiveness of Interventions for Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Adults with HIV: A Systematic Review. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2020, 54, e03627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, E.; Derrick, C.; Smalls, D.; Smith, H.; Kremer, N.; Weissman, S. Short-Term Adverse Events With BIC/FTC/TAF: Postmarketing Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, N.; Ritz, J.; Hughes, M.D.; Matoga, M.; Hosseinipour, M.C. Discontinuation of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate from Initial ART Regimens Because of Renal Adverse Events: An Analysis of Data from Four Multi-Country Clinical Trials. PLOS Glob. Public Heal. 2024, 4, e0002648. [Google Scholar]

- Prosperi, M.C.F.; Fabbiani, M.; Fanti, I.; Zaccarelli, M.; Colafigli, M.; Mondi, A.; D’Avino, A.; Borghetti, A.; Cauda, R.; Di Giambenedetto, S. Predictors of First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy Discontinuation Due to Drug-Related Adverse Events in HIV-Infected Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Feng, A.; Luo, D.; Yuan, T.; Lin, Y.F.; Ling, X.; Zhong, H.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Zou, H. Factors Associated with Immunological Non-Response after ART Initiation: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmacias Especializadas FESA. BIKTARVY 50/200/25 Mg TAB CAJ C/30. 2025. Available online: https://www.farmaciasespecializadas.com/biktarvy-50-200-25-mg-tab-caj-c-30.html?srsltid=AfmBOorD2oZwrXxW-eMQAGdzakiHqPqepx-6i1jS2_roAD6sjhg3FnFT (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Gutiérrez-Lorenzo, M.; Rubio-Calvo, D.; Urda-Romacho, J. Effectiveness, Safety, and Economic Impact of the Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide Regimen in Real Clinical Practice Cohort of Hiv-1 Infected Adult Patients. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2021, 34, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz-Bayo, E.; Navarro-Aznárez, H.; Pinilla-Rello, A.; Díaz-Calderón-Horcada, C.I. Evolución Temporal de La Terapia Antirretroviral (2017–2021): Análisis de La Modificación Del Tratamiento y Su Impacto Económico. Rev. Española Quimioter. 2023, 36, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clínicas Especializadas Condesa. Respuesta Epidemiológica Al VIH Sida y Hepatitis C En La Ciudad de México 2022. 2022. Available online: http://data.salud.cdmx.gob.mx/ssdf/portalut/archivo/Actualizaciones/1erTrimestre24/Dir_VIH-SIDA/Informe%20de%20VIH%202022%20-%20Ciudad%20de%20Mexico%20v%20Cierre2022.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Amapola-Nava, V. A 35 Años de La Caracterización Del Sida, Investigación de Vanguardia En El Cieni|Comisión Coordinadora de Institutos Nacionales de Salud y Hospitales de Alta Especialidad. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/insalud/articulos/a-35-anos-de-la-caracterizacion-del-sida-investigacion-de-vanguardia-en-el-cieni (accessed on 31 May 2024).

| Immune Stage | Baseline Probability | Utility Score (QALYs) | Initial Cost (Cycle 1) (USD$) | Incremental Cost (Cycles 2–5) (USD$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 < 200 cells/μL | 0.39 | 0.67 | 2147.37 | 2025.54 |

| CD4 200–349 cells/μL | 0.22 | 0.70 | 2118.01 | 1440.75 |

| CD4 350–499 cells/μL | 0.16 | 0.71 | 2118.01 | 1406.49 |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/μL | 0.23 | 0.73 | 2118.01 | 1400.78 |

| Sources | CSCs | Whitham, et al. (2020) [18] | CSCs and Official Gazette of the Federation [19,20] | CSCs and Official Gazette of the Federation [19,20] |

| Transition Between CD4 Stages | Year 1 | Year 2 | Years 3–5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| <200–<200 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.57 |

| <200–200–349 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.43 |

| <200–350–500 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| <200–500 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| <200–349–<200 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| <200–349–200–349 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.32 |

| <200–349–350–500 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.43 |

| <200–349–500 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| <350–500–<200 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| <350–500–200–349 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| <350–500–350–500 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.38 |

| <350–500–500 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.52 |

| <500–<200 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| <500–200–349 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| <500–350–500 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| <500–500 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| Variable | (N = 261) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 232 (88.9%) |

| Female | 20 (7.7%) |

| Transgender female | 9 (3.4%) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 35.74 ± 9.43 years |

| <28 years | 63 (24.1%) |

| 28–34 years | 63 (24.1%) |

| 35–42 years | 80 (30.7%) |

| >42 years | 55 (21.1%) |

| History of ART switch | |

| With switch history | 24 (9.2%) |

| No switch history | 237 (90.8%) |

| Time with current ART (mean ± SD) | 2.70 ± 1.28 years |

| 1–2 years | 130 (49.8%) |

| 3–4 years | 98 (37.6%) |

| 5 years | 33 (12.6%) |

| AI (mean ± SD) | 89.97 ± 11.98 |

| Non-adherents (AI < 95%) | 154 (59.0%) |

| Adherents (AI ≥ 95%) | 107 (41.0%) |

| Viral load | |

| Undetectable (<50 copies/mL) | 249 (95.4%) |

| Unsuppressed (≥50 copies/mL) | 12 (4.6%) |

| Current CD4 (mean ± SD) | 502.11 ± 251.46 |

| CD4 < 200 cel/µL | 21 (8.1%) |

| CD4 200–349 cel/µL | 56 (21.5%) |

| CD4 350–499 cel/µL | 68 (26.0%) |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cel/µL | 116 (44.4%) |

| Baseline CD4 (mean ± SD) | 320.10 ± 238.01 |

| CD4 < 200 cel/µL | 102 (39.1%) |

| CD4 200–349 cel/µL | 57 (21.8%) |

| CD4 350–499 cel/µL | 47 (18.0%) |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cel/µL | 55 (21.1%) |

| Variable | Mean AI ± SD | p-Value | <95% n (%) | ≥95% n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male (n = 232) | 89.92 ± 11.54 | 139 (59.9%) | 93 (40.1%) | ||

| Female (n = 20) | 88.91 ± 17.92 | 0.616 | 11 (55.0%) | 9 (45.0%) | 0.606 |

| Transgender female (n = 9) | 93.61 ± 6.56 | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | ||

| Age | |||||

| <28 years (n = 63) | 88.79 ± 12.79 | 38 (60.3%) | 25 (39.7%) | ||

| 28–34 years (n = 63) | 89.91 ± 12.43 | 0.623 | 40 (63.5%) | 23 (36.5%) | 0.778 |

| 35–42 years (n = 80) | 90.16 ± 13.07 | 46 (57.5%) | 34 (42.5%) | ||

| >42 years (n = 55) | 91.10 ± 8.57 | 30 (54.5%) | 25 (45.4%) | ||

| Time with current ART | |||||

| 1–2 years (n = 130) | 89.74 ± 10.94 | 83 (63.8%) | 47 (36.1%) | ||

| 3–4 years (n = 98) | 89.99 ± 14.24 | 0.497 | 51 (52.0%) | 47 (48.0%) | 0.196 |

| 5 years (n = 33) | 90.80 ± 8.30 | 20 (60.6%) | 13 (39.4%) | ||

| Viral load | |||||

| Undetectable (<50 copies/mL) (n = 249) | 89.90 ± 12.13 | 147 (59.0%) | 102 (41.0%) | ||

| Unsuppressed (≥50 copies/mL) (n = 12) | 91.41 ± 8.76 | 0.744 | 7 (58.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | 0.961 |

| Current CD4 | |||||

| CD4 < 200 cells/μL (n = 21) | 90.14 ± 5.64 | 16 (76.2%) | 5 (23.8%) | ||

| CD4 200–349 cells/μL (n = 56) | 89.28 ± 14.49 | 0.741 | 34 (60.7%) | 22 (39.3%) | 0.348 |

| CD4 350–499 cells/μL (n = 68) | 90.28 ± 12.44 | 37 (54.4%) | 31 (45.6%) | ||

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/μL (n = 116) | 90.08 ± 11.33 | 67 (57.8%) | 49 (42.2%) | ||

| Initial CD4 | |||||

| CD4 < 200 cells/μL (n = 102) | 89.18 ± 12.54 | 65 (63.7%) | 37 (36.3%) | ||

| CD4 200–349 cells/μL (n = 57) | 90.42 ± 13.32 | 0.215 | 29 (50.9%) | 28 (49.1%) | 0.198 |

| CD4 350–499 cells/μL (n = 47) | 92.86 ± 7.27 | 24 (51.1%) | 23 (48.9%) | ||

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/μL (n = 55) | 88.48 ± 12.55 | 36 (65.5%) | 19 (34.6%) |

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Ref. Male) | |||

| Female | 1.190 | 0.454–3.120 | 0.724 |

| Transgender female | 1.576 | 0.396–6.276 | 0.518 |

| Age (Ref. < 28 years) | |||

| 28–34 years | 0.802 | 0.374–1.720 | 0.571 |

| 35–42 years | 0.998 | 0.484–2.057 | 0.995 |

| >42 years | 1.279 | 0.576–2.838 | 0.545 |

| Treatment time (Ref. 1 year) | |||

| Treatment Time (2 years) | 1.008 | 0.467–2.174 | 0.985 |

| Treatment Time (3 years) | 1.847 | 0.827–4.126 | 0.134 |

| Treatment Time (4 years) | 1.197 | 0.482–2.974 | 0.699 |

| Treatment Time (5 years) | 1.090 | 0.402–2.951 | 0.866 |

| Viral load (Ref. Undetectable (<50 copies/mL)) | |||

| Unsuppressed (≥50 copies/mL) | 1.012 | 0.293–3.500 | 0.985 |

| Current CD4 (Ref. < 200 cells/μL) | |||

| CD4 200–349 cells/μL | 2.567 | 0.771–8.055 | 0.125 |

| CD4 350–499 cells/μL | 3.323 | 1.021–10.816 | 0.046 * |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/μL | 2.882 | 0.918–9.046 | 0.070 |

| Suspended ART over the weekend (Ref. No suspension) | 0.173 | 0.037–0.803 | 0.025 * |

| Cause | n (%) (N = 158) |

|---|---|

| Simply forgot | 78 (49.37%) |

| Was far from home | 72 (45.57%) |

| Had a change in daily routine | 41 (25.95%) |

| Busy with other things | 39 (24.68%) |

| Ran out of pills | 35 (22.15%) |

| Fell asleep through the dose time | 32 (20.25%) |

| Had trouble taking the pills at a specific schedule | 15 (9.49%) |

| Wanted to avoid side effects | 10 (6.33%) |

| Felt good | 10 (6.33%) |

| Did not want others to notice while taking medication | 9 (5.70%) |

| Felt sick or unwell | 8 (5.06%) |

| Had too many pills to take | 7 (4.43%) |

| Felt depressed or overwhelmed | 7 (4.43%) |

| Felt like the drug was toxic/harmful | 2 (1.27%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heyerdahl-Viau, I.; Prado-Galbarro, F.J.; Ávila-Ríos, S.; Rosas-Becerril, O.A.; Cruz-Flores, R.A.; Sánchez-Piedra, C.; Martínez-Núñez, J.M. Adherence and Cost–Utility Analysis of Antiretroviral Treatment in People Living with HIV in a Specialized Clinic in Mexico City. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030076

Heyerdahl-Viau I, Prado-Galbarro FJ, Ávila-Ríos S, Rosas-Becerril OA, Cruz-Flores RA, Sánchez-Piedra C, Martínez-Núñez JM. Adherence and Cost–Utility Analysis of Antiretroviral Treatment in People Living with HIV in a Specialized Clinic in Mexico City. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(3):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030076

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeyerdahl-Viau, Ivo, Francisco Javier Prado-Galbarro, Santiago Ávila-Ríos, Osmar Adrian Rosas-Becerril, Raúl Adrián Cruz-Flores, Carlos Sánchez-Piedra, and Juan Manuel Martínez-Núñez. 2025. "Adherence and Cost–Utility Analysis of Antiretroviral Treatment in People Living with HIV in a Specialized Clinic in Mexico City" Pharmacy 13, no. 3: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030076

APA StyleHeyerdahl-Viau, I., Prado-Galbarro, F. J., Ávila-Ríos, S., Rosas-Becerril, O. A., Cruz-Flores, R. A., Sánchez-Piedra, C., & Martínez-Núñez, J. M. (2025). Adherence and Cost–Utility Analysis of Antiretroviral Treatment in People Living with HIV in a Specialized Clinic in Mexico City. Pharmacy, 13(3), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13030076