Analysis of the Justice Component of a JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) Inventory in a College of Pharmacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Project Description

2.1. Setting

2.2. Determining What to Inventory

2.3. Conducting the Inventory

3. Findings (The Inventory of Justice)

3.1. Representation (Inventory Items 1–3)

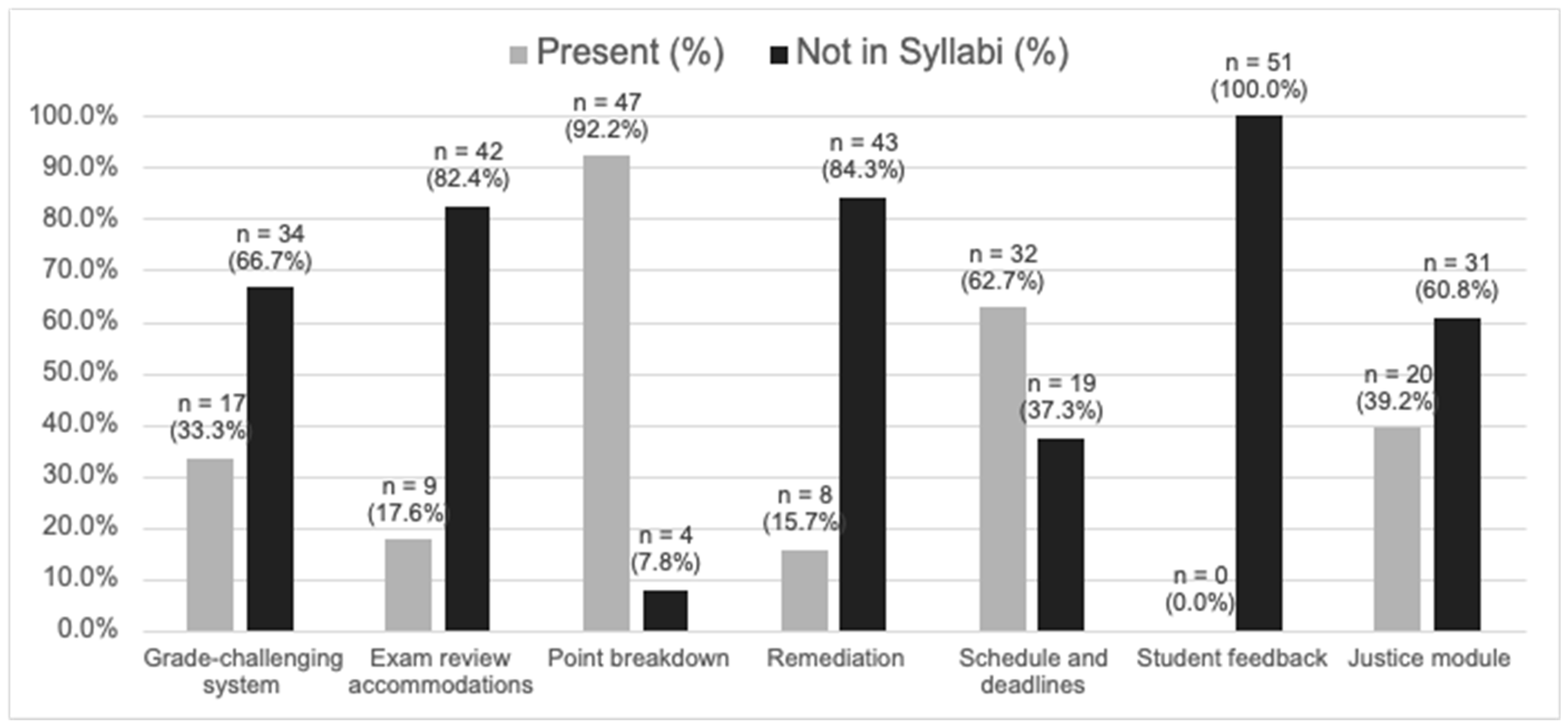

3.2. Curriculum and Education (Inventory Items 4–10)

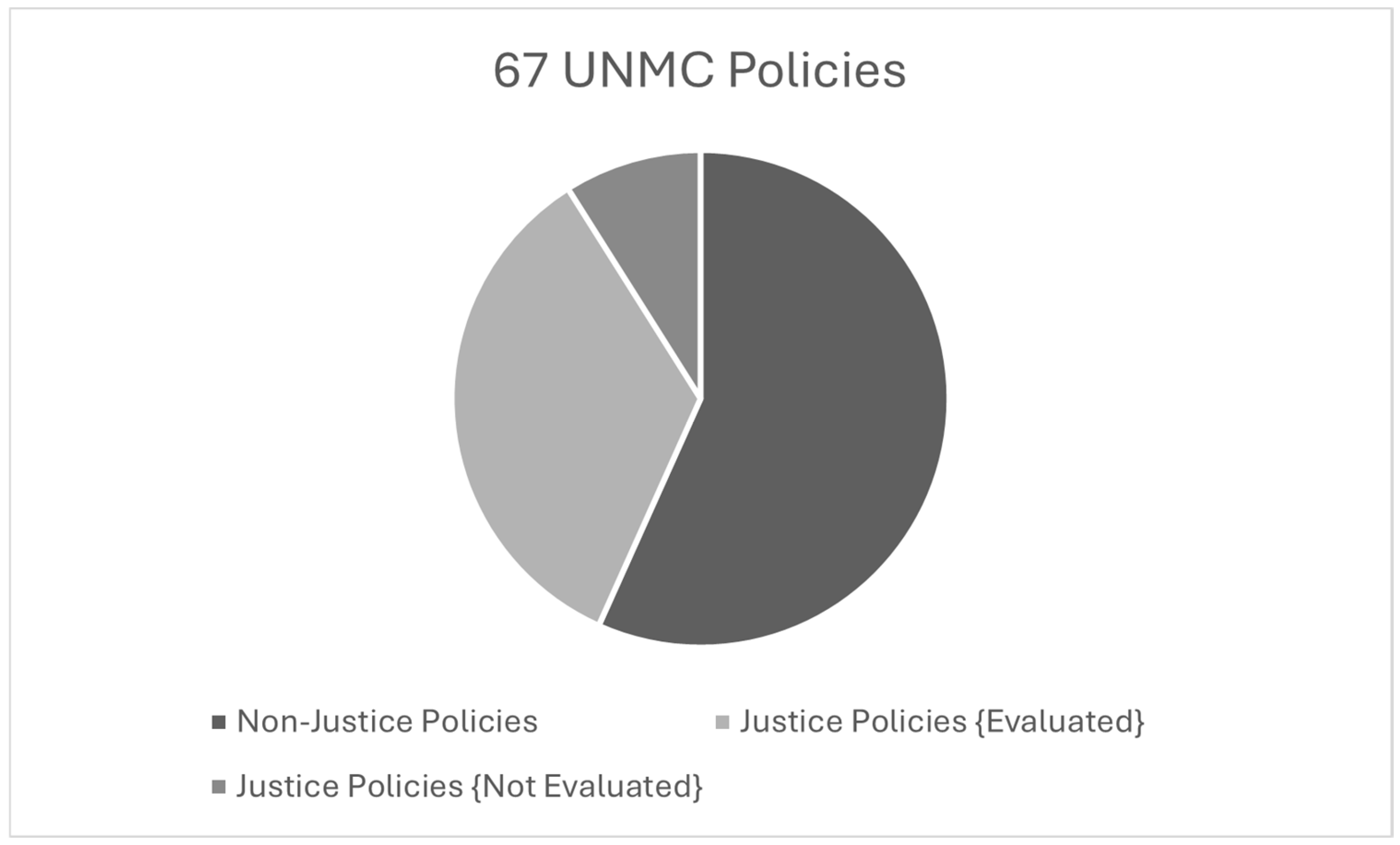

3.3. Policies and Procedures (Inventory Items 11–23)

3.4. Support and Available Resources (Inventory Items 24–26)

3.5. College Climate (Inventory Items 27–32)

4. Discussion

4.1. Representation

4.2. Curriculum and Education

4.3. Policies and Procedures

4.4. Support and Resources

4.5. College Climate

4.6. Additional Post-Inventory Changes

- The collaborative nature of this longitudinal process makes student input and involvement a key by focusing on APPE students interested in policy and Phi Lambda Sigma, the student leadership fraternity. It also merges the JEDI and Curriculum standing committees into this endeavor.

- The careful adherence to criteria in the Scholarship and Awards Committee removes as much subjectivity and bias as possible. This standard operating procedure for the Scholarship and Awards Committee should be replicated. Where possible and appropriate, blinding the identity of the student/faculty/staff and basing decisions on pre-determined and publicized criteria is a laudable goal. Interestingly, this process of blinded application and criteria-based evaluation is the process chosen for issuing invitations to join the UNMC-COP Beta Xi Chapter of Phi Lambda Sigma.

- Recognition of the results of the UNMC student satisfaction survey is also appropriate given the positive results regarding well-being. This recognition has the potential to increase future response rates.

4.7. Identified Areas for Improvement at UNMC-COP

- Improving information without increasing survey burden.

- More clearly defining reporting channels for concerns and making recommendations for improvement. Education in reporting options and processes will be necessary.

- Creating a data repository and responsibility for maintaining the information to allow for all future inventories and quality improvement work to have access to needed data.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree (“Standards 2016”); Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Engle, J.P. Executive Director ACPE, Letter to College of Pharmacy Deans, February 2022. Available online: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/DearDeanJanuary2022BoardMeetingUpdate.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Kelderman, E. Squeezed by Politics, an Accreditor’s Annual Meeting Concludes with No Vote on a DEI Standard; The Chronicle of Higher Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kelderman, E. The New Accountability, How Accreditors Are Measuring Colleges’ Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Efforts; The Chronicle of Higher Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.Q. Principles of Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220 (Suppl. S2), S30–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A. Diversity Statements Are Being Banned. Here’s What Might Replace Them; The Chronicle of Higher Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pozgar, G.D. Legal and Ethical Issues for Health Professionals, 4th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2016; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Embracing Equity Newsletter; Equity vs. Equality: Where It Differs (And How to Embrace Justice). Available online: https://www.embracingequity.org/post/equity-vs-equality-where-it-differs-and-how-to-embrace-justice (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Paresky, P. ‘Moral Pollution’ at the University of Chicago: The Case of Dorian Abbott. FIRE. December 2020. Available online: https://www.thefire.org/news/blogs/eternally-radical-idea/moral-pollution-university-chicago-case-dorian-abbot (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- About Us. University of Nebraska Medical Center. n.d. Available online: https://www.unmc.edu/aboutus/index.html (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Schuff Zimmerman, M.M.; Maclean, S.J.; DeringAnderson, A.M.; Alexander, E.D.; Maeda, B.T.; Tran, A.T.; Hoff, K.L.; Majid, S.J.; Stukenholtz, K.L.; Hansen, H.L. Discussion of an approach to starting a JEDI inventory in a College of Pharmacy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2024, 16, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holder, R.L. Untangling the Meanings of Justice: A Longitudinal Mixed Methods Study. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2018, 12, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirth, E.; Biermann, F.; Kalfagianni, A. What do researchers mean when talking about justice? An empirical review of justice narratives in global change research. Earth Syst. Gov. 2020, 6, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Barry, M.; Geer, M.; Klein, C.F.; Kumari, V. Justice Education and the Evaluation Process: Crossing Borders. Wash. UJL Pol’y 2008, 28, 195. Available online: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1191&context=law_journal_law_policy (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Tarantola, D.; Camargo, K.; Gruskin, S. Searching for Justice and Health. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1511–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. What Is Health Equity? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/health-equity/what-is/index.html (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Wiley, L.F.; Yearby, R.; Clark, B.R.; Mohapatra, S. Introduction: What is Health Justice? J. Law Med. Ethics 2022, 50, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arneson, R. “Egalitarianism”. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2013 Edition). Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/egalitarianism/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Equity vs. Equality: What’s the Difference? Online Public Health. Available online: https://www.marinhhs.org/sites/default/files/boards/general/equality_v._equity_04_05_2021.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Mack, K. BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and the Power and Limitations of Umbrella Terms. MacArthur Foundation. January 2023. Available online: https://www.macfound.org/press/perspectives/bipoc-lgbtq-power-limitations-umbrella-terms (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Process for the Review and Approval of Student Policies. University of Nebraska Medical Center. n.d. Available online: https://catalog.unmc.edu/general-information/student-policies-procedures/policy-review-approval/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Faltin, A.; Robertson, A.; Werther, E. Student Satisfaction Survey 2022–2023; [Data set]; University of Nebraska Medical Center: Omaha, NE, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Faltin, A.; Robertson, A.; Werther, E. Student Satisfaction Survey 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.hedsconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2023-2024_HEDS_Student_Satisfaction_Instrument.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Student Legal Services Nebraska. Available online: https://asun.unl.edu/student-legal-services/welcome (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Servaes, S.; Choudhury, P.; Parikh, A.K. What is diversity? Pediatr Radiol. 2022, 52, 1708–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santucci, A. Belonging as an academic/educational developer: Breathing for justice, together. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2022, 27, 308–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooven, C.K. Academic Freedom Is Social Justice: Sex, Gender, and Cancel Culture on Campus. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 52, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, A. Opinion: Biological Science Rejects the Sex Binary, and That’s Good for Humanity. The Scientist. 12 May 2022. Available online: https://www.the-scientist.com/biological-science-rejects-the-sex-binary-and-that-s-good-for-humanity-70008 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Lachaud, Q.A. Academic and disciplinary narratives that inhibit teaching for racial justice. Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 29, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer University College of Pharmacy Assessment Plan. 2022. Available online: https://pharmacy.mercer.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/34/2022/11/Assessment-Plan.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Wagner, J.L.; Smith, K.J.; Johnson, C.; Hilaire, M.L.; Medina, M.S. Best Practices in Syllabus Design. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 87, ajpe8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, C.R.; Bowen, D.M.; Paarmann, C.S. Curriculum evaluation of ethical reasoning and professional responsibility. J. Dent. Educ. 2003, 67, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorter, D.D. Teaching Evaluations Are Racist, Sexist, and Often Useless; The Chronical of Higher Education: Washington, DC, USA, 11 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dluhy, L.A.; Ingelfinger, J.R.; Brown, F.L.; Dluhy, D.H. Delivering Justice-A Case for the Medical Civil Rights Act. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, H. “Imbalances”: Mental Health in Higher Education. Humboldt J. Soc. Relat. 2017, 39, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Główczewski, M.; Burdziej, S. (In)justice in academia: Procedural fairness, students’ academic identification, and perceived legitimacy of university authorities. High. Educ. 2023, 86, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Student Policies and Procedures. University of Nebraska Medical Center. n.d. Available online: https://catalog.unmc.edu/general-information/student-policies-procedures/ (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Addison, K.; Appleton, J.; Sankar Datta, G.; Flanagan, K.; Hayes, K.; Herget, D.; Hooper, M.; Lewis, R.; Little, R.J.A.; Zotti, A.; et al. School Survey Participation and Burden; Technical Expert Panel; National Institute of Statistical Sciences: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Justice Inventory Items | Counted | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | 3.1 | |

| Yes | Leadership by Gender see Table 2 |

| Yes | Scholarships and Awards Standing Committee |

| Yes | Students are prohibited from serving on the committee. Committee membership evaluated for diversity. |

| Curriculum and Education | 3.2 | |

| Yes | See Figure 1 |

| Yes | See Figure 1 |

| Yes | See Figure 1 |

| Yes | See Figure 1 |

| Yes | No accommodations have been requested for exam reviews/question challenges, to date |

| Yes | Title IX Training is readily available Bystander Training is readily available |

| Yes | See Section 3.3 |

| Policies and Procedures | 3.3 | |

| Yes | 29 out of 67 of UNMC’s campus-wide policies. See Figure 2 |

| No | Difficult to quantify effective communication |

| No | The UNMC-COP has not developed a specific college policy. The UNMC-COP has adopted the campus-wide grievance resolution procedure |

| No | Difficult to quantify or determine awareness of these policies |

| Yes | 23 out of the 29 UNMC campus-wide justice-relating policies have been reviewed, while 6 policies have not been reviewed since their implementation |

| Yes | Standard approval procedure in place for implementation of new policies, but no policy that specifically considers impact that administrative decisions have on diverse groups |

| No | Difficult to determine and quantify awareness |

| No | No specific questions in satisfaction surveys were identified. No comments or concerns have been documented. |

| No | There is no identified feedback mechanism |

| Yes | Students urged to speak to Deans/faculty members or can look at the student policies and procedure page on UNMC’s website to find the correct person to report to |

| No | Data were not quantified at the UNMC level |

| Yes | 1007 students from the total UNMC student population (~23%) and 68 students from the COP (~36%) |

| Yes | 97% |

| Support and Resources | 3.4 | |

| Yes | Assistant Vice Chancellor of Inclusion for UNMC, Director of JEDI within the UNMC-COP, Dean of Student Affairs |

| Yes | JEDI Committee, student discipline committee, grade appeals committee |

| No | Lack of legal services—unable to be quantified |

| College Climate | 3.5 | |

| Yes | End-of-year surveys and individual course evaluations |

| Yes | 5 incidents within the last 5 years |

| No | Unable to identify reporting procedures, nor to locate any records of reports |

| No | Unable to identify reporting procedures, nor to locate records of reports |

| No | Deferred to the Diversity component of this project |

| No | Deferred to the Diversity component of this project |

| Leadership Role | N = 141 | Male, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Total, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty Advisor | 10 (77) | 3 (23) | 13 | |

| Class President | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 | |

| Class Vice-President | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 4 | |

| Class Secretary | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 4 | |

| Class Treasurer | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 4 | |

| Class Social Chair | 3 (33) | 6 (67) | 9 | |

| Class Historian | 1 (12) | 7 (88) | 8 | |

| Class Fundraising Chair | 1 (8) | 11 (92) | 12 | |

| Class Tech Chair | 4 (50) | 4 (50) | 8 | |

| Student Senate Representative | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 | |

| Student Organization President | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | 12 | |

| Student Organization President-Elect | 5 (62) | 3 (38) | 8 | |

| Student Organization Vice President | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 4 | |

| Student Organization Secretary | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | 10 | |

| Student Organization Treasurer | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 10 | |

| Miscellaneous Student Organization Position * | 9 (31) | 20 (69) | 29 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schulz, C.W.; Dubas, J.J.; Dering-Anderson, A.M.; Hoff, K.L.; Roskam, A.L.; Kasbohm, N.A.; Holtmeier, B.W.; Hansen, H.L.; Stukenholtz, K.L.; Carron, A.N.; et al. Analysis of the Justice Component of a JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) Inventory in a College of Pharmacy. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12040118

Schulz CW, Dubas JJ, Dering-Anderson AM, Hoff KL, Roskam AL, Kasbohm NA, Holtmeier BW, Hansen HL, Stukenholtz KL, Carron AN, et al. Analysis of the Justice Component of a JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) Inventory in a College of Pharmacy. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(4):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12040118

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchulz, Chad W., Jackson J. Dubas, Allison M. Dering-Anderson, Karen L. Hoff, Adam L. Roskam, Noah A. Kasbohm, Brady W. Holtmeier, Hannah L. Hansen, Kaitlyn L. Stukenholtz, Ashley N. Carron, and et al. 2024. "Analysis of the Justice Component of a JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) Inventory in a College of Pharmacy" Pharmacy 12, no. 4: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12040118

APA StyleSchulz, C. W., Dubas, J. J., Dering-Anderson, A. M., Hoff, K. L., Roskam, A. L., Kasbohm, N. A., Holtmeier, B. W., Hansen, H. L., Stukenholtz, K. L., Carron, A. N., & Tjards, L. M. (2024). Analysis of the Justice Component of a JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) Inventory in a College of Pharmacy. Pharmacy, 12(4), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12040118