Using Team-Based Learning to Teach Pharmacology within the Medical Curriculum

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Concept and Biology of Active Learning

1.2. Team-Based Learning as a Form of Active Learning in Medical Education

1.3. Understanding Team-Based Learning in Our Context

2. Materials and Methods

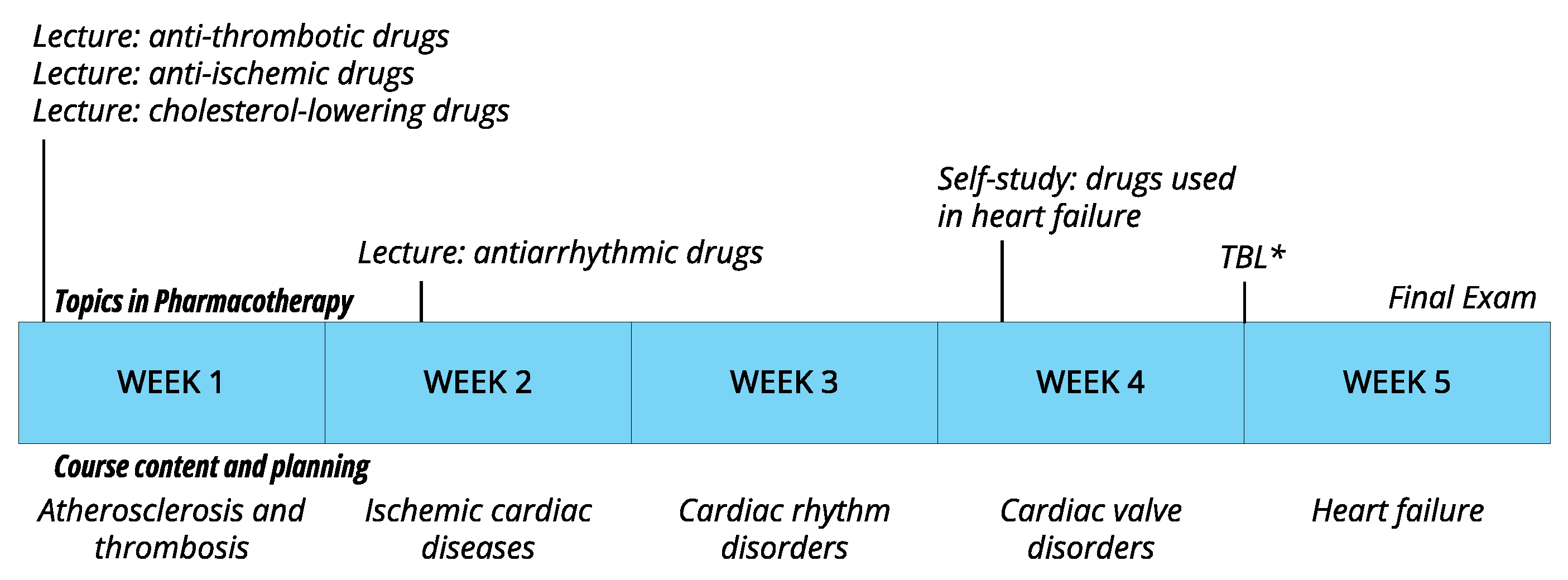

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Procedure

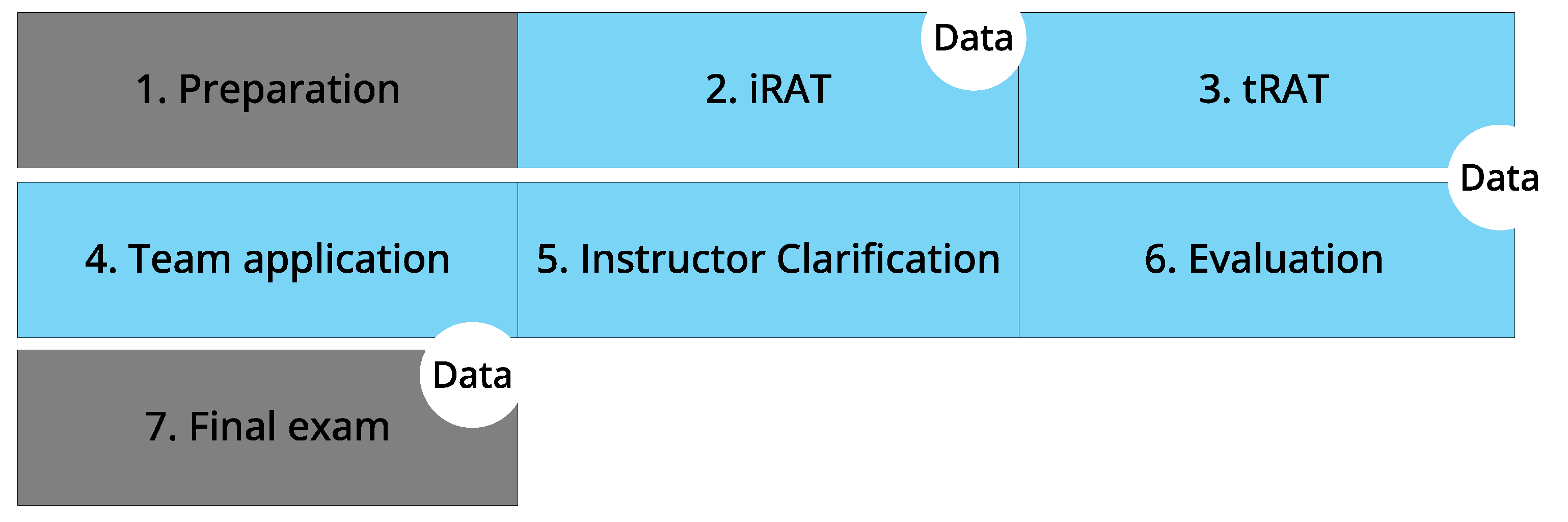

- Preparation: Two preparatory lectures delved into the pharmacological aspects of antianginal, antithrombotic, and antiarrhythmic drugs. Additionally, as preparation for TBL following these lectures, a preparatory study assignment was provided on heart failure medications. All educational activities were optional, with attendance prior to the TBL session left unrecorded. The preparatory study assignments were accessible for all students and included readings. The non-TBL group also had access to the same reading materials, and the slides of the TBL session were shared following the classes.

- Individual readiness assurance test (iRAT): PScribe, an electronic prescribing system was used for the iRAT. The iRAT consisted of seven questions covering all pharmacological topics of the course. Individual scores were recorded, which additionally served to note participation (attendance). The iRAT questions were closed-ended and were a mix of single and multiple correct answers for 2021–2022 and single correct answers for 2022–2023. For questions with multiple correct answers, a part of the full score was awarded for partially correct answers. Questions were at the level of understanding, applying or analyzing, according to Bloom’s taxonomy.

- Team readiness assurance test (tRAT): For the tRAT, students in groups discussed the same questions as during the iRAT and had to come to an agreement on the correct answers to the questions. This step differed from the traditional tRAT, as teams were not predefined, the tRAT scores were not formally registered, and the element of competition was not used in our setting. The reasons for the latter are two: we wanted to favor a low threshold for initiating discussion and engagement, and we also wanted to minimize administrative burden.

- Instructor clarification: topics considered complex by students were discussed with the entire class and clarified by the instructor.

- Team application: Students engaged in a collaborative problem-solving exercise involving a clinical case. For this, students were shown a patient video, followed by a set of questions, which students had to answer in groups.

- Feedback questionnaire: With the help of the online audience response system Wooclap, feedback on the TBL session on cardiovascular pharmacology was gathered through an anonymous digital questionnaire immediately at the end of the TBL session. The questionnaire comprised eight statements where students had to express their level of (dis)agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree). These statements were divided into two categories: (1) students’ own perception on knowledge and (2) feedback on using TBL as a learning method. Participation in the questionnaire via Wooclap was voluntary. There was no incentive provided to participate.

- Final exam: All students (TBL attendees and non-TBL attendees) took the final exam for the course on cardiovascular diseases via the digital examination platform Testvision. In the final exam, the content on cardiovascular pharmacology was assessed through seven questions in 2021–2022 and eight questions in 2022–2023. Closed-ended questions with single or multiple correct answers were used for this purpose. Similar to the iRAT, for questions with multiple correct answers, partially correct answers were rewarded with a part of the full score. Additionally, here, questions were at the level of understanding, applying or analyzing, according to Bloom’s taxonomy.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

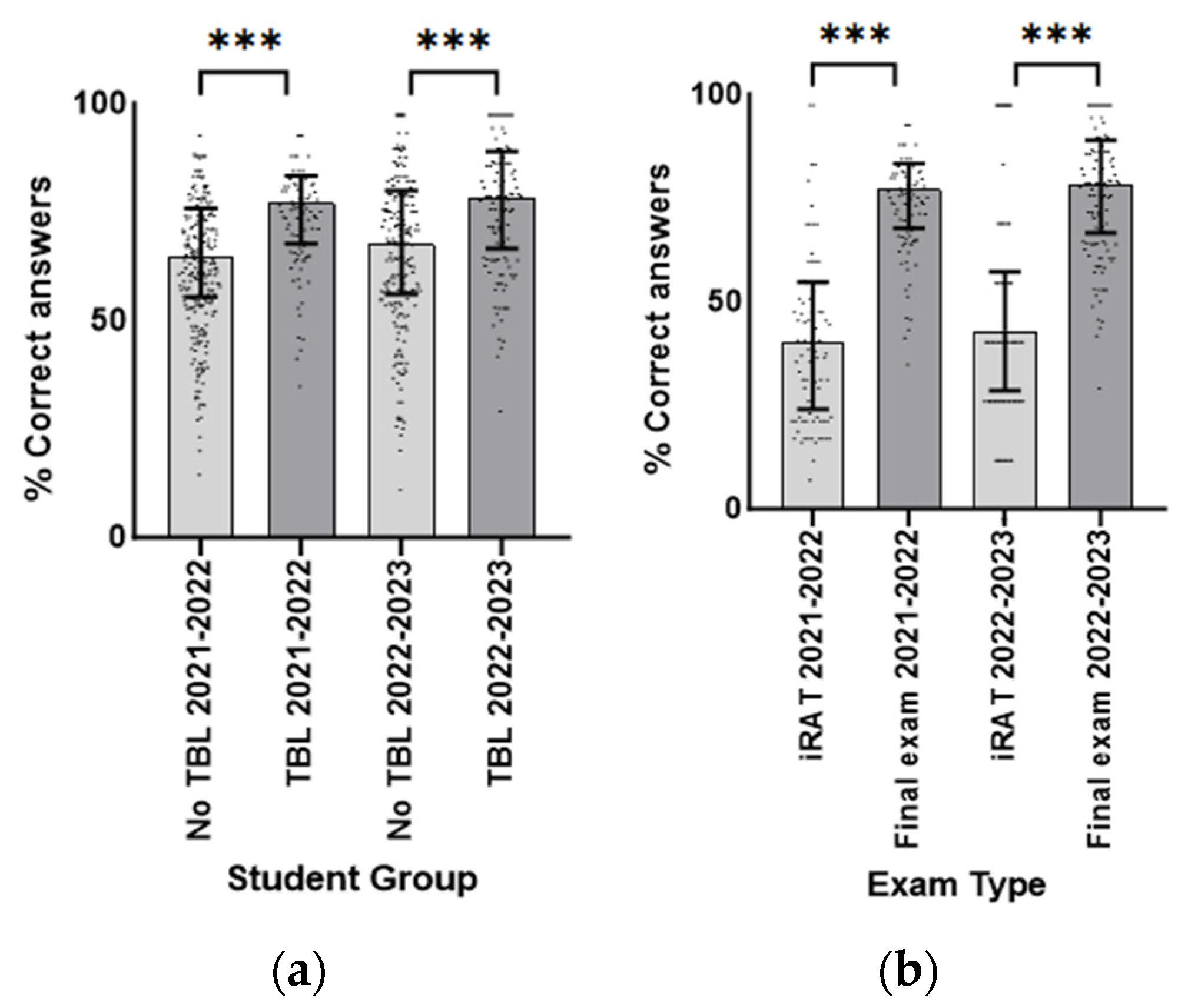

- The impact of TBL on students’ understanding of the subject matter was investigated by comparing final exam scores between TBL attendees and non-attendees, using the Mann–Whitney U test. Median scores are reported in percentages of correct answers.

- The TBL attendees’ individual performance in the final exam was examined by comparing their iRAT scores and final exam scores using the Mann–Whitney U test. Median scores are reported in percentages of correct answers.

- The correlation between iRAT scores and exam scores, to understand whether the performance in the former correlated with performance in the latter, was explored using Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

- The difficulty index of the individual questions (p-value) of both the iRAT and the final examination was analyzed to understand whether a possible disparity in the level of difficulty could explain the differences in student performance. The p-value for questions for one correct answer indicates the proportion of students who correctly answered the question. For questions with multiple possible answers or open-ended questions, the p-value indicates the proportion of the points obtained by students for a particular question [23]. In both cases, p-values range from 0 to 1, with easier items resulting in higher p-values. Differences between the p-values (iRAT vs. final exam) were tested using the Mann–Whitney U test.

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Student Perception Regarding Team-Based Learning

3.2. Student Performance with Team-Based Learning versus No Team-Based Learning

3.3. The iRAT Scores versus the Final Exam Scores

3.4. The Relationship between Individual Results during the iRAT and the Final Exam

3.5. The Difficulty Index (p-Value) of the iRAT and Final Examination Questions

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of Results for Pharmacology Educators

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wittich, C.M.; Burkle, C.M.; Lanier, W. Medication Errors: An Overview for Clinicians. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornan, T.; Ashcroft, D.; Heathfield, H.; Lewis, P.; Miles, J.; Taylor, D.; Tully, M.; Wass, V. An in Depth Investigation into Causes of Prescribing Errors by Foundation Trainees in Relation to Their Medical Education. EQUIP Study. Available online: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/FINAL_Report_prevalence_and_causes_of_prescribing_errors.pdf_28935150.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- McHugh, D.; Yanik, A.J.; Mancini, M.R. An innovative pharmacology curriculum for medical students: Promoting higher order cognition, learner-centered coaching, and constructive feedback through a social pedagogy framework. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, R.; Poleij, M.C.S.; Gerrits, M.A.F.M. Student Perception of Knowledge and Skills in Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapy in a Bachelor’s Medical Curriculum. Int. Med. Educ. 2023, 2, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslauriers, L.; McCarty, L.S.; Miller, K.; Callaghan, K.; Kestin, G. Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19251–19257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, G. Active learning in a constructivist framework. Educ. Stud. Math. 1996, 31, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, P.; Doolittle, P.; Wojdak, K.; Wojdak, K.; Walters, A.; Walters, A. Defining Active Learning: A Restricted Systemic Review. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.G.; Rotgans, J.I.; Rajalingam, P.; Low-Beer, N. A Psychological Foundation for Team-Based Learning: Knowledge Reconsolidation. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1878–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squire, L.R.; Genzel, L.; Wixted, J.T.; Morris, R.G. Memory Consolidation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a021766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberini, C.M.; LeDoux, J.E. Memory reconsolidation. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R746–R750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmelee, D.; Michaelsen, L.K.; Cook, S.; Hudes, P.D. Team-based learning: A practical guide: AMEE Guide No. 65. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, e275–e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; van Diggele, C.; Roberts, C.; Mellis, C. Team-based learning: Design, facilitation and participation. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20 (Suppl. 2), 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrynchak, P.; Batty, H. The educational theory basis of team-based learning. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.A. The pharmacology course for preclinical students using team-based learning. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2020, 32, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, S.; Motta, P.; Ferri, P.; Bonetti, L. The effectiveness of team-based learning in nursing education: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 97, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A. A Critical Review of Constructivist Theory and the Emergence of Constructionism. Am. Res. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G.E. Constructivist Learning Theory. In Proceedings of the CECA (International Committee of Museum Educators) Conference, Jerusalem, Israel, 15–22 October 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, N.E. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2015, 103, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koriťáková, E.; Jivram, T.; Gîlcă-Blanariu, G.-E.; Churová, V.; Poulton, E.; Ciureanu, A.I.; Louis, C.; Ștefănescu, G.; Schwarz, D. Comparison of problem-based and team-based learning strategies: A multi-institutional investigation. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1301269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelsen, L.K.; Davidson, N.; Major, C.H. Team-based learning practices and principles in comparison with cooperative learning and problem-based learning. J. Excell Coll. Teach. 2014, 25, 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Koens, F.; Mann, K.V.; Custers, E.J.F.M.; Cate, O.T.J.T. Analysing the concept of context in medical education. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneroso, D.; Erans, M. Team-based learning: An ethnicity-focused study on the perceptions of teamwork abilities of engineering students. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 46, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowski, M.J.; Bean, A.G. Believe it or not! longer questionnaires have lower response rates. J. Bus. Psychol. 1990, 4, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, T. Understanding Medical Education. In Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory, and Practice; Forrest, K., O’Brien, B.C., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, B.S.; Zeppa, R. Stress in junior medical students: Relationship to personality and performance. J. Med. Educ. 1984, 59, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Banna, M.M.; Whitlow, M.; McNelis, A.M. Improving Pharmacology Standardized Test and Final Examination Scores Through Team-Based Learning. Nurse Educ. 2020, 45, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgheib, N.K.; Simaan, J.A.; Sabra, R. Using team-based learning to teach pharmacology to second year medical students improves student performance. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterpu, I.; Herling, L.; Nordquist, J.; Rotgans, J.; Acharya, G. Team-based learning (TBL) in clinical disciplines for undergraduate medical students—A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.A.; Artino, A.R. Motivation to learn: An overview of contemporary theories. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Malcolm, C. Degrees of change: The promise of anti-racist assessment. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8, 972036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Wood, W.B.; Adams, W.K.; Wieman, C.; Knight, J.K.; Guild, N.; Su, T.T. Why Peer Discussion Improves Student Performance on In-Class Concept Questions. Science 2009, 323, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EChang, E.K.; Wimmers, P.F. Effect of Repeated/Spaced Formative Assessments on Medical School Final Exam Performance. Health Prof. Educ. 2017, 3, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.R.; Whitcomb, M.E.; Weitzer, W.H. Multiple surveys of students and survey fatigue. New Dir. Institutional Res. 2004, 2004, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, P.; Sanders, L. Understanding academic confidence. Psychol. Teach. Rev. 2006, 12, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.N.; Eva, K.W.; Rusticus, S.A.; Lovato, C.Y. The Readiness for Clerkship Survey. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SD (1) | D (2) | N (3) | A (4) | SA (5) | ME | MD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The TBL session has aided in achieving the learning objectives. | 0 | 4 | 15 | 72 | 52 | 4.2 | 4 |

| 2 | The structure of the TBL session was good. | 0 | 3 | 19 | 62 | 59 | 4.2 | 4 |

| 3 | The organization (planning, supervision, etc.) of the TBL session was good. | 0 | 0 | 16 | 60 | 67 | 4.4 | 4 |

| 4 | The content of the TBL session was informative. | 0 | 2 | 4 | 61 | 76 | 4.5 | 5 |

| 5 | I think I have sufficient knowledge on this subject. | 7 | 26 | 54 | 46 | 10 | 3.2 | 3 |

| 6 | I learnt a lot from the collaboration during the TBL session. | 1 | 14 | 42 | 59 | 27 | 3.7 | 4 |

| 7 | I learnt a lot from the practice questions. | 0 | 3 | 18 | 51 | 71 | 4.3 | 4 |

| 8 | The patient’s story has contributed to learning about the application of medicines in real life. | 2 | 15 | 45 | 57 | 25 | 3.6 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luitjes, N.L.D.; van der Velden, G.J.; Pandit, R. Using Team-Based Learning to Teach Pharmacology within the Medical Curriculum. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030091

Luitjes NLD, van der Velden GJ, Pandit R. Using Team-Based Learning to Teach Pharmacology within the Medical Curriculum. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(3):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030091

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuitjes, Nora L. D., Gisela J. van der Velden, and Rahul Pandit. 2024. "Using Team-Based Learning to Teach Pharmacology within the Medical Curriculum" Pharmacy 12, no. 3: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030091

APA StyleLuitjes, N. L. D., van der Velden, G. J., & Pandit, R. (2024). Using Team-Based Learning to Teach Pharmacology within the Medical Curriculum. Pharmacy, 12(3), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12030091