Pharmacists’ Attitudes towards Medically Assisted Dying

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Investigate NZ pharmacists’ awareness of and influences on their attitudes toward legalising medically assisted dying under the End of Life Choice Act 2021.

- Investigate pharmacists’ willingness to provide services consistent with the End of Life Choice Act 2021.

2. Methods

3. Results

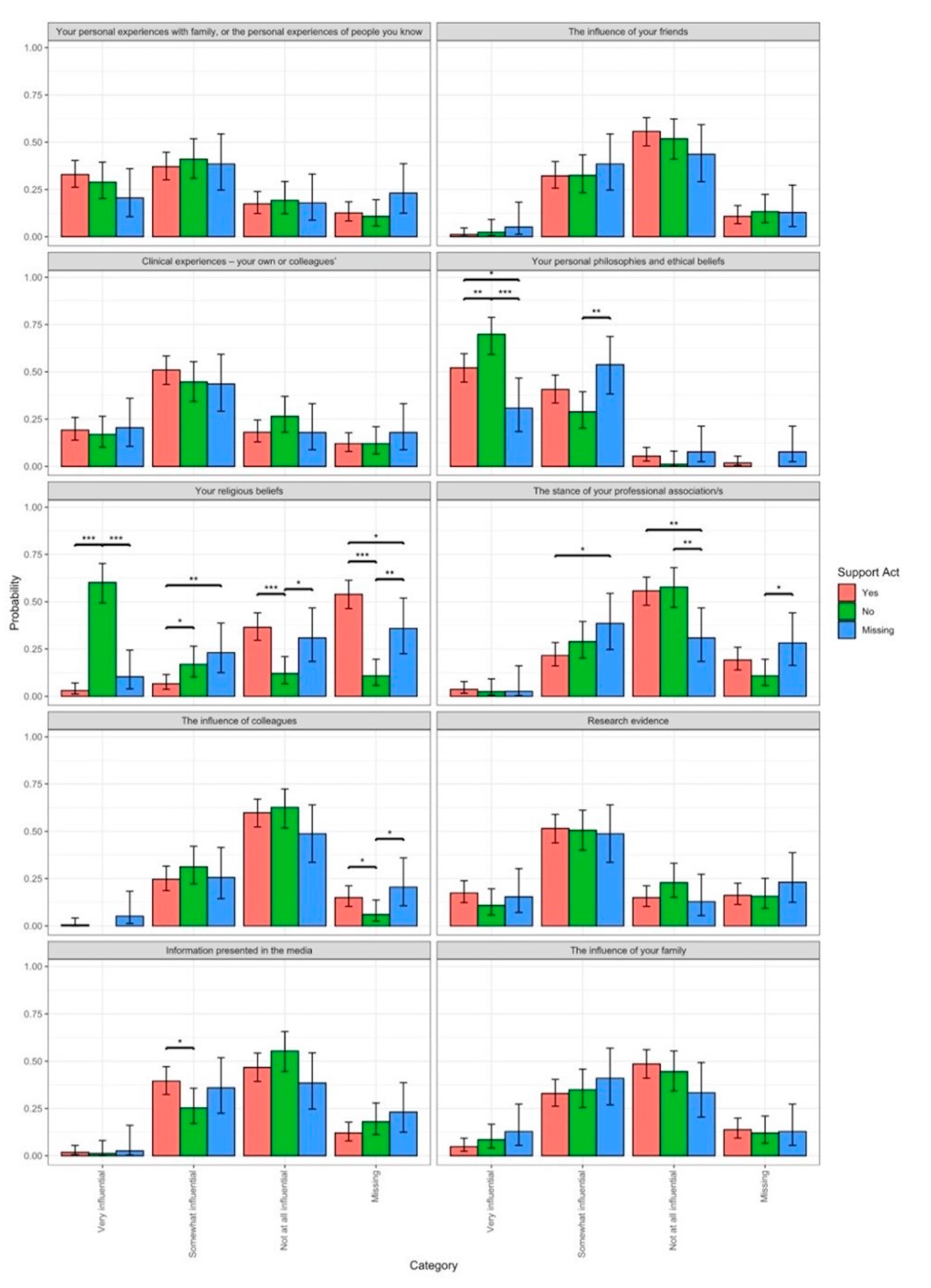

3.1. Other Factors Shaping Participants’ Views towards Legalising Medically Assisted Dying

3.2. Main Concerns around Legalising Medically Assisted Dying in New Zealand

3.3. Willingness to Provide EOLC-Based Services

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy Makers, Pharmacy Leaders, and Universities

4.2. Implication of the Findings for Practitioners

4.3. Implications of the Findings for Future Research

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Isaac, S.; McLachlan, A.; Chaar, B. Australian pharmacists’ perspectives on physician-assisted suicide (PAS): Thematic analysis of semistructured interviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berard, G.; Walker, J. CPhA surveys pharmacists on physician-assisted dying. Can. Pharm. J. CPJ 2016, 149, 54–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naafs, N.J. Pharmaceutical care until the end: The role of pharmacists in euthanasia in The Netherlands. Pharm. World Sci. PWS 2001, 23, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- End of Life Choice Act 2019 No 67 (as at 28 October 2021), Public Act Contents—New Zealand Legislation. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2019/0067/latest/DLM7285905.html (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- White, B.P.; Jeanneret, R.; Close, E.; Willmott, L. The impact on patients of objections by institutions to assisted dying: A qualitative study of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMC Med. Ethics 2023, 24, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, R.D.; Wilson, D.M.; Malpas, P. Assisted or Hastened Death: The Healthcare Practitioner’s Dilemma. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- End of Life Choice Act 2019 No 67 (as at 28 October 2021), Public Act 13 First Opinion to be Given by Attending Medical Practitioner—New Zealand Legislation. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2019/0067/latest/DLM7285958.html (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Isaac, S.; Pro, B.C.; Con, J.S. Should Pharmacists Be Allowed to Conscientiously Object to Medicines Supply on the Basis of Their Personal Beliefs? Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2018, 71, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buetow, S.; Gauld, N. Conscientious objection and person-centered care. Theor. Med. Bioeth. 2018, 39, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Pharmacy Council of New Zealand. Code of Ethics 2011. 2011. Available online: https://pharmacycouncil.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Code-of-Ethics-web.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Code of Ethics 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.psa.org.au/practice-support-industry/ethics/#:~:text=PSA%27s%20Code%20of%20Ethics%20for,of%20all%20pharmacists%20in%20Australia (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Woods, P.; Schindel, T.J.; King, M.A.; Mey, A. Pharmacy practice in the domain of assisted dying: A mapping review of the literature. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Wiechula, R.; Cusack, L.; Wilson, M. Nurses’ intentions to respond to requests for legal assisted dying: A Q-methodological study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Wilson, M.; Edwards, S.; Cusack, L.; Wiechula, R. Role of attitude in nurses’ responses to requests for assisted dying. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 670–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models. R Package Version 0.4.6. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scutari, M. Learning Bayesian Networks with the bnlearn R Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 35, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workforce Demographics. Pharmacy Council NZ-Public Site. Retrieved. 2021. 1 January 2022. Available online: https://pharmacycouncil.org.nz/public/workforce-demographics/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Oliver, P.; Wilson, M.; Malpas, P. New Zealand doctors’ and nurses’ views on legalising assisted dying in New Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 2017, 130, 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.; Oliver, P.; Malpas, P. Nurses’ views on legalising assisted dying in New Zealand: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 89, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E9 Statistics—Referendums Results. Available online: https://www.electionresults.govt.nz/electionresults_2020/referendums-results.html (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Submissions and Position Statements: Pharmaceutical Society of NZ. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.psnz.org.nz/Folder?Action=View%20File&Folder_id=101&File=PSNZ%20Submission-%20End%20of%20Life%20Choice%20Bill.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Newsletters. Pharmacy Council NZ—Public Site. Available online: https://pharmacycouncil.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Newsletter-Oct-2021-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Ministry of Health NZ. Roles in the Assisted Dying Service. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/life-stages/assisted-dying-service/information-health-professionals/roles-delivery-service (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Yazdanparast, E.; Davoudi, M.; Ghorbani, S.H.; Akbarian, A.; Chenari, H.A. Investigating the relationship between moral sensitivity and attitude towards euthanasia in nursing students of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. Clin. Ethics 2022, 17, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suazo, I.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.; Molero Jurado, M.D.; Martos Martínez, Á.; Simón Márquez, M.D.; Barragán Martín, A.B.; Sisto, M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Moral Sensitivity, Empathy and Prosocial Behavior: Implications for Humanization of Nursing Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koltko-Rivera, M. The Psychology of Worldviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2004, 8, 3–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, A.; Gould, O.; LeBlanc, M.; Manuel, L.; Brideau-Laughlin, D. Knowledge and Attitudes of Hospital Pharmacy Staff in Canada Regarding Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD). Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2019, 72, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Snelling, J.; Beaumont, S.; Diesfeld, K.; White, B.; Willmott, L.; Robinson, J.; Ahuriri-Driscoll, A.; Cheung, G.; Dehkhoda, A.; et al. What do health care professionals want to know about assisted dying? Setting the research agenda in New Zealand. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliative Care in New Zealand is Critically Ill—Hospice New Zealand. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.hospice.org.nz/about-hospice-nz/palliative-care-in-new-zealand-is-critically-ill-d-2/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Hanlon, T.R.; Weiss, M.C.; Rees, J. British community pharmacists’ views of physician-assisted suicide (PAS). J. Med. Ethics 2000, 26, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulugeta, T.; Alemu, S. Knowledge and attitudes toward euthanasia among final year pharmacy and law students: A cross-sectional study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2023, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francke, A.L.; Albers, G.; Bilsen, J.; de Veer, A.J.E.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D. Nursing staff and euthanasia in the Netherlands. A nation-wide survey on attitudes and involvement in decision making and the performance of euthanasia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansky, M.; Jaspers, B.; Radbruch, L.; Nauck, F. Einstellungen zu und Erfahrungen mit ärztlich assistiertem Suizid. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2017, 60, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrand, M.A.; Nordstrand, S.J.; Materstvedt, L.J.; Nortvedt, P.; Magelssen, M. Medisinstudenters holdninger til legalisering av eutanasi og legeassistert selvmord. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Legeforening 2013, 133, 2359–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, E.; Burkert, N.; Großschädl, F.; Rásky, É.; Stronegger, W.J.; Freidl, W.W. Determinants of Public Attitudes towards Euthanasia in Adults and Physician-Assisted Death in Neonates in Austria: A National Survey. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Responses to Support for Legalising Medically Assisted Dying in New Zealand | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unsure | Total | |||||

| Area of Work | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Community Pharmacy Owner | 34 | 20.4% | 15 | 18.1% | 6 | 16.7% | 55 | 19.2% |

| Community Pharmacy Manager | 16 | 9.6% | 4 | 4.8% | 1 | 2.8% | 21 | 7.3% |

| Community Pharmacist | 65 | 38.9% | 39 | 47% | 15 | 41.7% | 119 | 41.6% |

| Academic Pharmacist | 5 | 3.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.8% | 6 | 2.1% |

| Hospital Pharmacist | 26 | 15.6% | 16 | 19.3% | 8 | 22.2% | 50 | 17.5% |

| Other | 21 | 12.7% | 9 | 10.8% | 5 | 13.9% | 35 | 12.2% |

| 167 | 100% | 83 | 100% | 36 | 100% | 286 | 100% | |

| Missing response | 3 | 1.0% | ||||||

| Age | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| 20–25 | 18 | 10.8% | 7 | 8.4% | 5 | 13.9% | 30 | 10.5% |

| 26–30 | 25 | 15.0% | 11 | 13.3% | 6 | 16.7% | 42 | 14.7% |

| 31–35 | 23 | 13.8% | 8 | 9.6% | 5 | 13.9% | 36 | 12.6% |

| 36–40 | 22 | 13.2% | 11 | 13.3% | 5 | 13.9% | 38 | 13.3% |

| 41–45 | 13 | 7.8% | 7 | 8.4% | 2 | 5.6% | 22 | 7.7% |

| 46–50 | 17 | 10.2% | 10 | 12.0% | 3 | 8.3% | 30 | 10.5% |

| 51–55 | 20 | 12.0% | 11 | 13.3% | 3 | 8.3% | 34 | 11.9% |

| 56–60 | 11 | 6.6% | 7 | 8.4% | 1 | 2.8% | 19 | 6.6% |

| 61–65 | 9 | 5.4% | 8 | 9.6% | 5 | 13.9% | 22 | 7.7% |

| >65 | 9 | 5.4% | 3 | 3.6% | 1 | 2.8% | 13 | 4.5% |

| 167 | 100% | 83 | 100% | 36 | 100% | 286 | 100% | |

| Missing response | 3 | 1.0% | ||||||

| Years of practice | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| 0–2 | 18 | 10.8% | 8 | 9.6% | 5 | 13.9% | 31 | 10.9% |

| 3–5 | 18 | 10.8% | 11 | 13.3% | 8 | 22.2% | 37 | 13.0% |

| 6–10 | 28 | 16.9% | 8 | 9.6% | 3 | 8.3% | 39 | 13.7% |

| 11–15 | 22 | 13.3% | 15 | 18.1% | 5 | 13.9% | 42 | 14.7% |

| 16–20 | 16 | 9.6% | 5 | 6.0% | 2 | 5.6% | 23 | 8.1% |

| 21–25 | 14 | 8.4% | 7 | 8.4% | 3 | 8.3% | 24 | 8.4% |

| 26–30 | 16 | 9.6% | 7 | 8.4% | 2 | 5.6% | 25 | 8.8% |

| 30 and above | 34 | 20.5% | 22 | 26.5% | 8 | 22.2% | 64 | 22.5% |

| 166 | 100% | 83 | 100% | 36 | 100% | 285 | 100% | |

| Missing response | 4 | 1.4% | ||||||

| Emerging Theme | Subtheme | Data Quotation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Criminality | Legalities Enforcement Historical Precedence Loopholes and exemptions Interpretation disagreement | “I am not happy with how the law has been written, too many loopholes” (Pharmacist 170) “I have concerns about the end point of this legislation with the right to die extended to an inappropriate extent and with vulnerable people being pressured to make choices they do not actually want” (Pharmacist 40) “I am not against euthanasia, I do believe however that this piece of legislation is very poor” (Pharmacist 241) |

| Palliation | Service provision Lack of service offer Role of service | “Best practice palliative care should make assisted dying unnecessary” (Pharmacist 115) “I support the principal of assisted dying for individual cases, but, certainly in the UK, and possibly in NZ I would hate future governments to push assisted dying at the expense of good palliative care” (Pharmacist 131) “There has not been an option proposed to increase funding and availability of palliative care to this subset of patients so patients not well managed aren’t provided with the full array of options” (Pharmacist 191) |

| Vulnerability | Professional ethics Power of attorney Financial burden Disability | “Concern the process may be influenced by people other than the person concerned” (Pharmacist 141) “Politicians start out with an idea but over time the safeguards get whittled away. How long before the end-of-life choice is extended to disabilities or IHC people”. (Pharmacist 148) “Wavering support as this is a personal decision for the person and so it is important to have safeguards—and I’m not sure the Act addresses the people who would most ‘benefit, i.e., the very end of life. It is very situation dependent and I’m unclear how a legal Act can cover all personal situations” (Pharmacist 229) |

| Suffering and Indignity | Emotional response Helplessness Reduction in suffering Dealing with suffering Current death process | “The pain for everyone involved watching someone suffer while having no quality of life” (Pharmacist 69) “I see people at the end of life, stuck in bodies that no longer function and these people are often in pain” (Pharmacist 117) “Seeing patients and knowing what they must go through” (Pharmacist 167) |

| Autonomy | Choice Freedom to decide Personal experience with friends or family Emotional responses | “Speaking to a specialist palliative care pharmacist leader, and an ethicist as part of the information gathering helped me understand my own “philosophies” and personal feelings on assisted dying”. (Pharmacist 8) “I still believe in and support the hospice aim to improve quality of life until the end, but my some of my experiences there and the people I encountered have lead me to feel quite strongly that individuals should have the right to end their suffering if they choose” (Pharmacist 188) “Working in the environment I do—I find that hope drives the decisions we make to fight help people live. I struggle to reconcile my fight for hope with assisted dying” (Pharmacist 325) |

| Emerging Theme | Subtheme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Legality | Criminality Legalities Enforcement Historical Precedence Exemptions Interpretation disagreement Accountability | “The legislation will be under great pressure to extend it to other inappropriate groups” (Pharmacist 40) “The regulations around it have to be tight enough that people won’t be able to do it on a whim, along with children who can’t understand the decision fully or people who will try to misuse it” (Pharmacist 228) “The current legislation is very loose and extremely short for something as important as the ending of a person’s life, especially when considering other medical legislation within NZ law and comparisons to legislation in other countries on assisted dying. It does not provide safeguards to the widening of criteria” (Pharmacist 296) |

| Personal Bias | Objective bias Personal opinions Conscious bias | “I’m concerned about supplying the medicine myself, I support the bill but don’t want to be involved in supplying the medicine” (Pharmacist 26) “I do not believe providing this tool under a legislation as national ‘act’ is in any way promoting a human beings right of life” (Pharmacist 43) “Personally I think it’s such a burden to place on medical professionals. This includes pharmacists- who may have to dispense medication that is intended for this use” (Pharmacist 156) |

| Palliation | Service provision Lack of service offer Role of service Alternative service provision | “Ensuring that the person has had good, appropriate access to palliative care and mental health services BEFORE the decision to take the medically assisted dying route” (Pharmacist 8) “Less money could potentially be spent on hospice and end-of-life care leading to people who do NOT choose medically assisted dying being left with fewer options for treatment and care” (Pharmacist 148) “That palliative care will continue to be underfunded leaving people without access to adequate palliative are and then they feel like they don’t have any other option but to seek medically assisted dying, when this option could be avoided” (Pharmacist 224) |

| Stigma | Personal Professional Pharmacist Peers Fear Discrimination | “Patients and providers being publicly persecuted for using or providing the service” (Pharmacist 15) “Pressure from people who don’t think similarly—as always, there are always those who will spread misinformation about the Act and its consequences” (Pharmacist 114) “Potential to put the profession in a ‘tough place’—should it get to the stage where people are collecting the drugs needed to carry out the medically assisted suicide from the pharmacy, that would be extremely distressing…. this goes against the core principle that a healthcare professional should be able to practise according to their own beliefs and values” (Pharmacist 179) |

| Vulnerability | Professional ethics Power of attorney Disability Access Rural care Inappropriate influence Coercion Timing to access | “I am concerned that this will become an expectation, and that those with terminal illness will feel obliged to take this route. I am also concerned that people will feel coerced into this” (Pharmacist 31) “The ‘right’ of an individual to choose to die may become a ‘duty” to die for reasons apart from what it is originally outlined, such as pressure from burdened family members, financial hardships, emotional distress or psychological conditions that may hinder their abilities to make the right and honest decision” (Pharmacist 43) “Detecting coercion from the patient is difficult—we do not know what happens behind close doors and how much pressure the patient may have been given to influence their decision to take this choice. …Several long-term conditions that cannot be cured, such as Multiple Sclerosis, that cause disability are also terminal illnesses hence will meet the criteria” (Pharmacist 221) |

| Emerging Theme | Subtheme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Legal | Referral to medical practitioner Scope of Practice Obtain consent Obedience to Legislation | “I would have no concerns discussing the Act and process—as described within the permissions of the Act” (Pharmacist 8) “Whatever that is relevant to our scope of practice” (Pharmacist 89) “Services consistent with the role of a pharmacist” (Pharmacist 265) |

| Professionalism | Counselling and support Whanau support Provision of some service Service awareness Information queries Multi-disciplinary team meetings | “Counselling and support of patient” (Pharmacist 4) “Supportive services to outline what other services are available” (Pharmacist 112) “Whatever is asked of me by any GP I work with who may provide the service” (Pharmacist 114) |

| Service/Access | Dispensing/preparation of medicine Provision of medication Procedural information Delivery of medications Provision of leaflets Procurement of medicine Medication review | “I would be willing to help supply or in a collaborative setting provide support through the process or administering of such a service” (Pharmacist 35) “Procurement and preparation of medicines involved” (Pharmacist 57) “Dispensing prescriptions; advice on use of end of life medicines” (Pharmacist 182) |

| Education | Education Upskilling | ” Education re medication provision and admin” (Pharmacist 13) “Advice on how the medicine works, how to take it, how quickly it works. If they were unsure then advice about other pain relieving or other treatments that may ease their suffering a bit if pain was a problem (so if their medicine management was suboptimal)” (Pharmacist 54) “Education of people or medical staff as appropriate” (Pharmacist 156) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, L.S.; Scahill, S.L.; Barton, E.; Van der Werf, B.; Boey, J.; Ram, S. Pharmacists’ Attitudes towards Medically Assisted Dying. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12020040

Wong LS, Scahill SL, Barton E, Van der Werf B, Boey J, Ram S. Pharmacists’ Attitudes towards Medically Assisted Dying. Pharmacy. 2024; 12(2):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12020040

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Lun Shen, Shane L. Scahill, Emma Barton, Bert Van der Werf, Jessica Boey, and Sanyogita (Sanya) Ram. 2024. "Pharmacists’ Attitudes towards Medically Assisted Dying" Pharmacy 12, no. 2: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12020040

APA StyleWong, L. S., Scahill, S. L., Barton, E., Van der Werf, B., Boey, J., & Ram, S. (2024). Pharmacists’ Attitudes towards Medically Assisted Dying. Pharmacy, 12(2), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12020040