“Why Didn’t They Teach Us This?” A Qualitative Investigation of Pharmacist Stakeholder Perspectives of Business Management for Community Pharmacists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethics Approval

2.3. Australian Community Pharmacy Environment

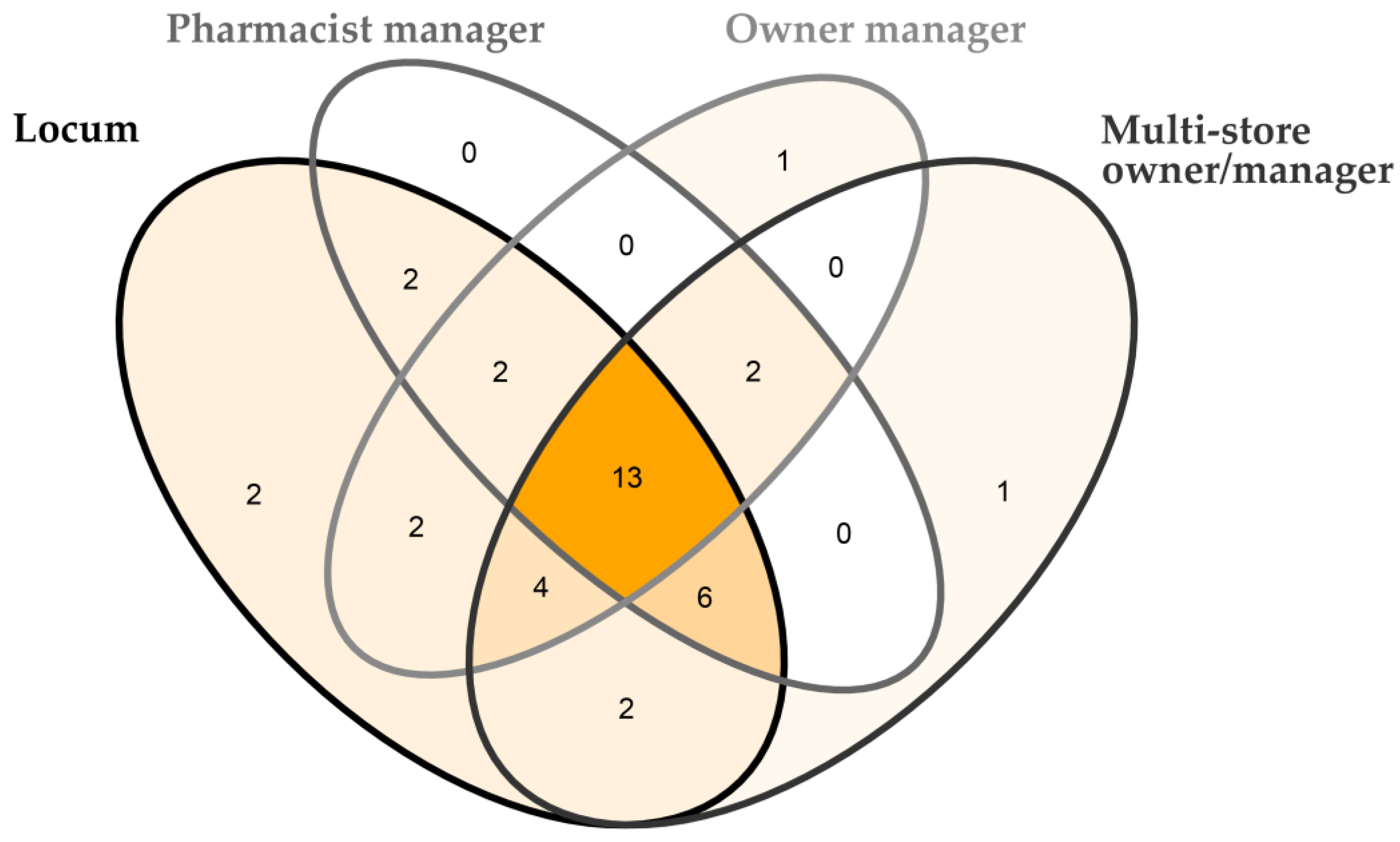

2.4. Study Population

2.5. Interviews

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extracted Business Management Skills

3.2. Barriers to Involving Business Management in the Pharmacy Curriculum

3.2.1. Not Covering Business Management in the Pharmacy Programs

“So much of the role is human resources these days…Definitely none of that taught at university”.(2-QLD)

“I didn’t learn anything about how to run the pharmacy and how to manage staff in university”.(1-TAS)

“Sometimes you work in pharmacy, and you think why did they not teach us how to do this [business management]”.(3-TAS)

“We didn’t get a single skerrick of business information, even just the basics”.(4-TAS)

“I think there is tight curriculum space and I think one of the things that tends to fall off is actual business management skills”.(5-TAS)

3.2.2. Delivering Clinical-Work-Ready Pharmacists… Not Managers

“The problem is that not every pharmacist that goes to university is going to want to manage or want to end up in management”.(2-QLD)

“In a class setting you are just mainly thinking about patient interaction and your clinical knowledge”.(3-QLD)

“My perception on BPharm would be to come out clinically ready to be a health practitioner to support patients in their community… I find that the business skill aspect isn’t necessarily aligned with what the community is expecting of a community pharmacist”.(2-TAS)

3.3. Strategies to Improve Business Management in the Pharmacy Curriculum

3.3.1. How Do We Prepare Students for Business Management?… That Is a Really Good Question

“It’s important to place them in a pharmacy where there is a feedback mechanism where that particular pharmacy has a good reputation for developing students. I think where they are placed, those proprietors should really be held to account with some sort of checklist, some sort of standard. They should respect that when they have students these guys are being moulded”.(1-QLD)

“It really comes from experience over the years and it also comes from having mentors, people that I either looked up to or learn from. I’ve always had a business coach to help me, I’ve always had somebody to help me”.(1-QLD)

“Mentoring… it would be really helpful if there was a core group of experienced pharmacists that wish to impart their experiences on younger people”.(5-TAS)

3.3.2. Keep Business Management Simple

“Teaching basic management concepts, how to problem solve, how to critically access situations, strategic direction all of those things that are not really taught”.(2-QLD)

“A full year in your final year of university set purely for business… where you have to learn the real basics of pharmacy business management”.(4-QLD)

“You often don’t need the nitty-gritty detail. What you really need is a ‘big hands, small maps’ type of thing”.(5-TAS)

3.4. Barriers to Involving Business Management in the Community Pharmacy

3.4.1. Inconsistency in the Standards of Managerial Skills

“If you’re not managing a store there’s a whole skill set that’s less important… I mean they still overlap but, it’s less important”.(2-QLD)

“You have to have those basic [management] skills developed into you, similar to clinical skills, when you’re coming up”.(4-QLD)

“If people wish to pursue ownership, management, you know pharmacist in charge, with responsibilities for business administration, they’re skills that not everyone would necessarily need… I don’t think they are an essential requirement”.(2-TAS)

3.4.2. Finding Time for Business Management

“Short staffed everyday all day…just insanely busy and no good skilled staff… it’s hard to find good skilled staff”.(2-QLD)

“The reason there is a lack of employment and difficulty in maintaining pharmacists has exactly got to do with the environment that pharmacy is in right now”.(4-QLD)

“In a rural place they probably just want to try throw you straight in and get you going cause they’re desperate for staff… you just literally have to figure it out as you go”.(6-QLD)

3.5. Strategies to Improve Business Management in the Community Pharmacy

3.5.1. We Need a Dual Thinking Process

“They need to have this dual thinking process, always the professional with duty of care for the patient, but also being commercial”.(1-QLD)

“It’s good if you can have a balance between having some clinical work as well as management… after a while I really missed that patient contact”.(6-QLD)

“I think there is this disconnect, and I think a lot of pharmacists and perhaps young pharmacist proprietors have an opportunity to go either way, they can look at their clientele as being patients or consumers, they’ve lost the healthcare focus”.(5-TAS)

3.5.2. Leadership and Mentorship Are Rewarding

“The actual role itself is really enjoyable, it’s nice just to be able to help people and help them do better”.(1-QLD)

“One of things I do like to do is be helpful to people… to see them succeed in a very competitive world brings me satisfaction and joy”.(5-TAS)

“The biggest positive you can have… is when you actually make a change in someone’s life, when you actually do that, that’s an incredible feeling”.(6-TAS)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| State | Position | Location | Gender | Business Model | Unique Population Code | I.D. Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QLD | Multi-store owner manager | Urban | M | Banner group/Corporate | 1-QLD,MOM,U,M,B | 1 |

| QLD | Multi-store owner manager | Rural and remote | M | Banner group/Corporate | 2-QLD,MOM,R,M,B | 2 |

| QLD | Pharmacist in charge | Rural and remote | F | Independent | 3-QLD,PIC,R,F,I | 3 |

| QLD | Locum | Rural and remote | M | Independent | 4-QLD,L,U,M,I | 4 |

| QLD | Pharmacist manager | Urban | M | Banner group/Corporate | 5-QLD,PM,U,M,B | 5 |

| QLD | Locum | Rural and remote | F | Independent | 6-QLD,L,R,F,I | 6 |

| TAS | Pharmacist manager | Rural and remote | F | Independent | 1-TAS,PM,R,F,I | 1 |

| TAS | Owner manager | Rural and remote | M | Independent | 2-TAS,OM,R,M,I | 2 |

| TAS | Pharmacist manager | Urban | M | Banner group/Corporate | 3-TAS,PM,U,M,B | 3 |

| TAS | Multi-store manager | Urban | M | Banner group/Corporate | 4-TAS,MOM,U,M,B | 4 |

| TAS | Locum | Rural and remote | M | Independent | 5-TAS,L,R,M,I | 5 |

| TAS | Owner manager | Urban | M | Independent | 6-TAS,OM,U,M,I | 6 |

Appendix B

| Management Skill or Aptitude | Management Skills and Aptitudes Identified in Thematic Analysis of Community Pharmacist Interviews |

|---|---|

| Conceptual | |

| General business management | Giving advice how to run the store better, solve issues, audits and standards checks (1-QLD), different roles, dealing with rosters… orders, management dealing with deliveries and problems (2-QLD), and the all the standard stuff, PBS, pharmacy programs, claims (4-QLD), KPI’s, budgeting, growth of front shop (5-QLD) admin roles, emailing, ordering (6-QLD), I do what the owners do, all the day to day basics, the rosters and checking everything is okay (1-TAS) a wide array of tasks that fall on a daily basis (2-TAS), making sure tasks are completed (3-TAS), lots of different roles, the normal stuff, maximise the income for the pharmacy, each day is different (4-Tas), the day to day running of the pharmacy (6-Tas). |

| Problem solving | I look around and hone in on where I can see weakness (1-QLD), how to problem solve, how to critically access situations (2-QLD), having to make decisions and learn things (6-QLD), coming up with unique and creative solutions (2-TAS), fill gaps, make the decisions to make things easier for people (4-TAS), having a business strategy, knowing how to do things and the value of doing them (5-TAS). |

| Pharmacy operations | It’s doing compliance audits, DD’s, all of our standards (1-QLD), various standing operating procedures, the workflow of the pharmacy (4-QLD), the other side of management was KPI’s, budgeting and front of shop (5-QLD), recording, auditing data, medication safety type of work (6-QLD), same as the owners, all the day to day basics, checking everything is okay to work (1-TAS), I’m intimate with the operations of my business (2-TAS), it’s hard to define because two days can be very different…dispensing, to nursing homes, maximising the income of the pharmacies (4-TAS), how to do things structurally and develop a purpose for the business (5-TAS), ensure the day-to-day running of the pharmacy from an operational perspective (6-TAS). |

| Organizational skills | Organisation, connecting people (1-QLD), organising training (6-QLD), organising changes and managing subcontractors, that’s the hard part knowing where to find the information and who to call (4-TAS), developing structures, what you want to do and how you might want to do that (5-TAS), day-to-day running of the pharmacy, the operations and make sure it runs smoothly (6-TAS). |

| Innovation | The big problem we have is how do we service these additional activities [expanding scope of practice]. Robotics is an area that we have to look at (5-TAS). |

| Business planning | Strategic direction, risk management (2-QLD), planning and implementing professional services (4-QLD), change management (6-QLD), viability sustainability of services (2-TAS), business model planning and viability (4-TAS), business strategy and structures (5-TAS), identify and develop new business opportunities (6-TAS). |

| Inventory management | Ordering, management with deliveries and associated problems (2-QLD), stock control management (3-QLD), stock ordering (5-QLD), consulting around supply and storage (6-QLD), orders and everything (1-TAS), stock management, ordering (2-TAS), stock, ordering and deciphering what you need (3-TAS), logistics (4-TAS). |

| Networking and relationships | National support offices, accounting teams, admin teams, marketing buying teams… spend time and learn from them (1-QLD), multidisciplinary type consults, like nurses (6-QLD), outsourcing business roles, engaging lawyers, accountants to support and develop gaps in skills (2-TAS), negotiating changes, managing the subcontractors, locum agencies (4-TAS), networking with small group of other pharmacies (5-TAS). |

| Retail operations | I deal with the manager about running the store better or helping solve issues (1-QLD), the day-to day basics, all the tills and orders, just everything (1-TAS), I’m intimate with the operations of my business (2-TAS), make sure stores are running profitably and trying to sort of streamline those operations where practical as much as possible (4-TAS), the day-to-day running of the pharmacy (6-TAS). |

| Larger perspective | But, that’s on the big scope…the skills differ on the grander scope (4-QLD), understanding how pharmacy works (6-QLD), sustainability of community pharmacy (2-TAS), step outside the pharmacy machine (5-TAS). |

| Entrepreneurship | Nil. |

| Human | |

| Communication | Mentoring people, I look out for personal problems, whether they are sleeping okay, how their home life is, you never know what you are going to find (1-QLD), if you manage to create an environment where the team is happy and clicking, it’s excellent (2-QLD), patient education (3-QLD), management of staff (4-QLD), all the H.R. issues, recruiting, interviewing, so staffing (5-QLD), multidisciplinary consults, meetings, education committee meetings (6-QLD), your behaviour, how you affect people and asking for feedback (1-TAS), part of my role is assisting the retail manager and working as a team to help each other (3-TAS), how to talk to people, as far as managing staff (4-TAS), I’m mentoring at the moment, working with pharmacists to try and run a business (5-TAS). |

| Professionalism | Some people are superb at legislation, others are slack and you have to pull them-up, c’mon mate you can’t do that (1-QLD),professional self-respect… put your professionalism foot down (4-QLD), one pharmacist staffed on their own in a busy pharmacy, they are never doing their job properly (6-QLD), earning respect… it’s about your behaviour and how you affect people (1-TAS), brining-in elements of professionalism within the business (5-TAS). |

| Leadership | We look at students as future pharmacists…I think they lack leadership skills (1-QLD), creating an environment where everybody works well together (2-QLD), regardless of what role you are in, there’s always some form of leadership (3-QLD), providing guidance in those early years (5-QLD), be able to get people on board with what you are trying to achieve (6-QLD), very big on being a leader (1-TAS), I’m mentoring at the moment…seeing others succeed, that’s my motivation (6-TAS). |

| Teamwork | Working with managers in the group (1-QLD), creating an environment where everyone is working well together and clicking (2-QLD), the difficult part is to get other people on board with what you are trying to achieve (6-LD), it’s about your behaviour and how you affect people, I often ask for feedback (1-TAS), that’s part of the role and part of the challenge, to through these things and work together (3-TAS), working with other pharmacists has been good, being able to roll ideas off them (4-TAS), using the 70,000 people we have in our workforce, pharmacy assistants, that’s an untapped resource we have to look at (5-TAS). |

| Customer care | Patient education and counselling (3-QLD), for example, a patient is nervous about being vaccinated, they want the pharmacist to reassure them and this takes time (4-QLD), patient centred care and patient contact (6-QLD), we give the patient value for money, they pay more and get more information and advice (1-TAS), first and foremost, engaging with my patient cohort and providing care (2-TAS), making the decisions to make things easier for people…depending on what you want to do for the people on the ground (4-TAS), professionalism is important, a risk with being a businessman is that you can lose track of your primary training, which is healthcare (5-TAS), making a change in someone’s life, that an incredible feeling (6-TAS). |

| Self-awareness | I probably overload myself, cram too much and that’s probably self-inflicted (1-QLD), at the end of the day, it really just depends on what your interests are (3-QLD), most pharmacists don’t see themselves as pharmacist…this is me, this is my character (4-QLD), try to figure it out and problem solve instead of just complaining about it (6-QLD), it’s about your behaviour and affect to people, and asking for feedback (1-TAS), learning from the world around me, asking questions (2-TAS), I’m a self-driven person, you need that drive (3-TAS), I like using my brain in a different way (4-TAS), step outside the pharmacy machine, ask yourself as an individual how you wish to practice (5-TAS), try to get yourself out of those roles, concentrate on the business rather than being in the being in the business, it’s easier said than done (6-TAS). |

| Personnel management | Mentoring people, looking out for personal problems… looking for issues (1-QLD), dealing with different staff personalities…just insanely busy and no good skilled staff (2-QLD), what makes it hard in community pharmacy is staff management and the personalities that work there (4-QLD), conflict resolution, interviewing, … all H.R. issues, so staffing, rostering (5-QLD), some of the roles are around other staff, working with pharmacy assistants, making sure they’re on track and supporting them (6-QLD), how to earn respect, and not just become a manager…I often ask for feedback from assistants (1-TAS), staff, H.R. (2-TAS), it can be difficult to manage staff at times…being sick, resigning, poor performance, clashes (3-TAS), making sure there is sufficient staff, … hiring, firing, H.R. (4-TAS), I’m mentoring at the moment…assisting with business management (5-TAS), people management (6-TAS). |

| Dedication | I’m up for the challenge (6-QLD), everything I’ve learnt is self-taught and self-considered (2-TAS), I’m pretty well embedded in the pharmacy profession (5-TAS), we identified opportunities and we’re like dogs with bones at it (6-TAS). |

| Independent | I was the sole pharmacist as well as the actual manager (5-QLD), in regional or remote areas, you just have to figure it out as you go (6-QLD), we don’t have a second pharmacists, I’m the only pharmacist here (1-TAS), a lot of it was self-taught (2-TAS), no one helped me (5-TAS). |

| Being ethical | Caring whether a pharmacist is speaking to ethics (4-QLD), being instructed to bend the rules and laws for personal gain, it’s so wrong (6-QLD), it’s about your behaviour and how you affect people (1-TAS), we have consumerised healthcare, we should be a health service, not a commodity-based service (5-TAS). |

| Being proactive | Looking for gaps and filling them (1-QLD), I learnt this through my own research, it was self-taught, seeing the world around me, asking questions (2-TAS), the business side is good because you are challenging yourself (6-QLD), I’m a self-driven person, that drive helps you go that extra mile (3-TAS), no one helped me, one you have the guts to sort of start charging for your brain activity, cognition, then things will change for that business (5-TAS), the thrill of the chase is what drove me, and you’d get one on the hook and then to um, to manage to land it was what it was all about in my book (6-TAS). |

| Adaptable | Looking for gaps and filling them (1-QLD), depending on your personality, you can overcome challenges or not (4-QLD), it’s challenging always being the one on call and balancing work and being a mom, trying to get the balance right (6-QLD), being stuck with lack of staff, employing locums after locums (1-TAS), the last three years in we’ve seen the most changes ever in pharmacy (3-TAS), I enjoy the variety (4-TAS). |

| Empathy | Preceptors can lack enthusiasm, don’t really care about them (1-TAS), someone that’s newly a graduated pharmacist… handing over the managing aspects of the business to them, that’s a significant requirement to place on someone and probably a bit unfair (2-TAS), most pharmacists don’t see themselves as pharmacists, I can guarantee that. They don’t want know or want to except what the meaning of a pharmacist is (4-QLD). |

| Time management | I cram too much, that’s probably self-inflicted (1-QLD), H.R. takes up a lot of my time, it’s not particularly enjoyable… there is not enough time in the day (2-QLD), out of pressure from time, they tend to deviate from professional standards (4-QLD), trying to balance work that you need to get done, if you had an office that you didn’t get disturbed, you could get the work done. (6-QLD), I had a 2-h hand over, that’s the nature of the business, they don’t want to pay people more than they need to (4-TAS). |

| Ambition, risk taking | It drives me to keep going, I’m self-driven and when you have that drive behind you, it helps you go the extra mile (3-TAS), once you’ve got the guts to start changing your brain activity, cognition then things will change for the business, people will see the value and you can manage a crisis better (5-TAS), identified the opportunities, and went at it like dog’s with bones, it’s fun, the thrill is in the chase (6-TAS). |

| Conflict resolution | Handling difficult customers or staff, how to handle pressure (1-QLD), so much of the role it’s H.R. these days, dealing with different staff personalities (2-QLD), the H.R. side of things is average, the staff can have a lot of issues with each other, conflict resolution and that sort of stuff (5-QLD), one assistant gave me a little bit of a hard time (1-TAS), it can be quite difficult to handle staff at times, clashes between staff or staff with customers, but it’s part of the role (3-TAS), staff will do it the way they think it’s correct, there can be a lot of resistance and fightback implementing changes (4-QLD). |

| Resilient | I look for personal problems, are they sleeping okay, how their home life is, any health issues (1-QLD), the last 6 months have been incredible stressful, you are constantly behind the eight-ball (2-QLD), there is definitely the feeling out there, people are just like why are we expected to do all this extra stuff because I think people are tired after Covid (6-QLD). |

| Confidence | You just might not be confident with business, have staff issue or culture issues (1-QLD), I have confidence from witnessing a management crisis, I now know I cannot be the worst (1-TAS), really deliver the skills that are going to be required, to help build up the confidence (2-TAS), sometimes you assume you don’t have it (4-TAS), learn things and reach out to people, it just builds up your confidence (6-TAS). |

| Affinity to role repetitiveness | Not to say you don’t use your brain day to day, but when you do something enough, you sort of you can develop habits and develop things that are probably good for avoiding errors. but maybe don’t stretch you as much as they should. I definitely enjoy the variety and probably using my brain in a different way (4-TAS). |

| Technical | |

| Professional development | Mentoring people…, reviewing business goals and progress with those goals… having a coach to help (1-QLD), gaining new skills, as it opens up new doors (6-QLD), I worked with ten different pharmacists and saw ten different styles of management (1-TAS), stepping in and learning completely from the bottom (4-TAS), one thing we do wrong in pharmacy is continuing professional development, we don’t modulate things very well (5-TAS), my mentor invested in me quite heavily, going to industry specific courses such as finance and management… I was lucky to have a mentor (6-TAS). |

| Financial analysis | Whether something is worthwhile pursuing from a financial standpoint (2-QLD), a greater competition, the pure finances and sticking to your procedures… that’s the negative, too focussed on the dollar (4-QLD), management stuff like, KPI’s, budgeting. The business analysis was good, to see how the business was performing (5-QLD), the viability of expanding scope services (6-QLD), what a profit and loss sheet looks like (2-TAS), the financial side of things, which I didn’t know much about (3-TAS), read profit and loss… maximise the profits (4-TAS), how do you wish to exploit your business in a profitable sense (5-TAS), understanding the nuances of the pharmaceutical benefit scheme and how that relates back to a profit and loss (6-TAS). |

| Marketing and promotion | I throw a business cap on, marketing, a wide array of various tasks that might fall on a daily basis (2-TAS). |

| Business acumen | Very strong business minded (4-QLD), good healthcare is good business…being efficient and sustainable (2-TAS), you need to make sure it’s viable, because we are a business from a community pharmacy perspective (3-TAS), from a business side, I think it’s a good chance to make decisions…the long term viability… maximising income (4-TAS), a lot of young owners out there don’t have a good business head (5-TAS), my job… business development, identify opportunities, chase them up… understand how it all worked (6-TAS). |

| Pharmacy law | Reviewing all the standards, the DD’s, S3′s, S4′s (1-QLD), out of time or pressure…deviate from professional standards, sometimes unfortunately legal aspects (4-QLD), you should know your obligations are, because there’s a legal or legislation to what you are claiming (5-QLD), there’s a lot of legislation…each state has its own legislation (6-QLD). |

| Technology | Auditing data, generating data and the software that goes with that (6-QLD), additional business structures, such as adding in robotics (5-TAS). |

| Business model diversity | It’s the structure of the individual business, different roles will be delegated to different pharmacists (3-QLD), we all need the same skills, the difference comes down to metro or somewhere where there is greater competition (4-QLD), it depends on the size of the pharmacy (5-QLD), I learned in a bigger chain pharmacy, it’s actually not one person’s job, everyone has different roles and responsibilities (1-TAS), awareness of the environment community pharmacists are entering, various business structures or workplaces (2-TAS), it depends on the size of the pharmacy, the way the pharmacy is run (4-TAS), work with the discount models that are around us, be aware of pricing, but you can win the battle with cognitive services (5-TAS), modern pharmacy is becoming more and more corporatized (6-TAS). |

| Prior experience | It really comes from having experience (1-QLD), with the shortage of pharmacists, there’s probable more early career pharmacists going into management that might not be experienced enough yet, not just a pharmacist as a human (5-QLD), I don’t think you come out of university being business management ready, it’s all experience (6-QLD), a lot of these skills are learnt over the years through working in community pharmacy (2-TAS), I have had a lot of experience in owning businesses, both pharmacy and non-pharmacy related (5-TAS). |

| Community Pharmacist Position | Business Model | Location | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business Management Skill or Aptitude | Locum (n = 3) | Manager (n = 4) | Owner Manager (n = 2) | Multi-Store Owner/Manager (n = 3) | Independent (n = 7) | Banner Group or Corporate (n = 5) | Urban (n = 5) | Rural and Remote (n = 7) | Skills/Aptitudes Used across All Populations |

| Conceptual | |||||||||

| General business management | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 3 (5-QLD), (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 5 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 5 (1-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (2-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | Yes |

| Problem solving | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 1 (2-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 4 (2-QLD), (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Pharmacy operations | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 2 (3-QLD), (3-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 6 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (5-QLD), (4-TAS). | 4 (1-QLD), (5-QLD), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

| Organizational skills | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 1 (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | No |

| Innovation | 1 (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 1 (5-TAS). | No |

| Business planning | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 5 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 2 (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (2-QLD), (4-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Inventory management | 1 (6-QLD). | 4 (3-QLD), (5-QLD), (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 1 (2-TAS). | 2 (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 4 (3-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | 4 (2-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 3 (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 5 (2-QLD), (3-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | Yes |

| Networking and relationships | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 1 (2-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Retail operations | 0 | 1 (1-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | No |

| Larger perspective | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 1 (2-TAS). | 0 | 4 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 4 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Entrepreneur | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Human | |||||||||

| Communication | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 4 (3-QLD), (5-QLD), (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 0 | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 5 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | 5 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 4 (1-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 6 (2-QLD), (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Professionalism | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 1 (1-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 4 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 4 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Leadership | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 3 (3-QLD), (5-QLD), (1-TAS). | 0 | 2 (1-QLD), (2-QLD). | 0 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (5-QLD). | 2 (1-QLD), (5-QLD). | 5 (2-QLD), (3-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Teamwork | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 2 (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 0 | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | 4 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 4 (2-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Customer care | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 2 (3-QLD), (1-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 1 (4-TAS). | 6 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 1 (4-TAS). | 2 (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 6 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

| Self-awareness | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 3 (3-QLD), (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 6 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 4 (1-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | Yes |

| Personnel management | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 3 (5-QLD), (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 5 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 5 (1-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (2-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | Yes |

| Dedication | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 0 | 4 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 0 | 1 (6-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Independent | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 2 (5-QLD), (1-TAS). | 1 (2-TAS). | 0 | 0 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 1 (5-QLD). | 1 (5-QLD). | 4 (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Being ethical | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 1 (1-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 4 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 4 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (5-TAS). | No |

| Being proactive | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 1 (3-TAS). | 2 | 1 (1-QLD). | 4 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (3-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (3-TAS), (6-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

| Adaptable | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 2 (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 0 | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS). | No |

| Empathy | 0 | 1 (1-TAS). | 1 (2-TAS). | 1 (1-QLD). | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 1 (1-QLD). | 1 (1-QLD). | 2 (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | No |

| Time management | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 3 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (2-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | No |

| Ambition, risk-taking | 1 (5-TAS). | 1 (3-TAS). | 1 (6-TAS). | 0 | 0 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 1 (3-TAS). | 2 (3-TAS), (6-TAS). | 1 (5-TAS). | No |

| Conflict resolution | 1 (4-QLD). | 3 (5-QLD), (1-TAS), (3-TAS). | 0 | 2 (1-QLD), (2-QLD). | 2 (4-QLD), (1-TAS). | 4 (1-QLD), (2-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS). | 3 (2-QLD), (4-QLD), (1-TAS). | No |

| Resilient | 1 (6-QLD). | 0 | 0 | 2 (1-QLD), (2-QLD). | 1 (6-QLD). | 2 (1-QLD), (2-QLD). | 1 (1-QLD). | 2 (2-QLD), (6-QLD). | No |

| Confidence | 1 (6-QLD). | 1 (1-TAS). | 1 (2-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS). | Yes |

| Affinity to role repetitiveness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4-TAS). | 0 | 1 (4-TAS). | 1 (4-TAS). | 0 | No |

| Technical | |||||||||

| Professional development | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 1 (1-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 5 (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (1-QLD), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 4 (6-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

| Financial analysis | 3 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 2 (5-QLD), (3-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (2-QLD), (4-TAS). | 5 (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 4 (2-QLD), (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 4 (5-QLD), (3-TAS), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (2-QLD), (4-QLD), (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

| Marketing and promotion | 0 | 0 | 1 (2-TAS). | 0 | 1 (2-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 1 (2-TAS). | No |

| Business acumen | 2 (4-QLD), (5-TAS). | 1 (3-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 1 (4-TAS). | 4 (4-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (3-TAS), (4-TAS). | 3 (3-TAS), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 3 (4-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

| Pharmacy law | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 2 (5-QLD). | 0 | 1 (1-QLD). | 2 4-QLD), (6-QLD). | 2 (1-QLD), (5-QLD). | 2 (1-QLD), (5-QLD). | 2 (4-QLD), (6-QLD). | No |

| Technology | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 0 | 0 | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | No |

| Business model diversity | 2 (4-QLD), (5-TAS). | 3 (3-QLD), (5-QLD), (1-TAS). | 2 (2-TAS), (6-TAS). | 1 (4-TAS). | 6 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS), (6-TAS). | 2 (5-QLD), (4-TAS). | 3 (5-QLD), (4-TAS), (6-TAS). | 5 (3-QLD), (4-QLD), (1-TAS), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

| Prior experience | 2 (6-QLD), (5-TAS). | 1 (5-QLD). | 1 (2-TAS). | 1 (1-QLD). | 3 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | 2 (1-QLD), (5-QLD). | 2 (1-QLD), (5-QLD). | 3 (6-QLD), (2-TAS), (5-TAS). | Yes |

References

- Perepelkin, J.; Dobson, R.T. Influence of ownership type on role orientation, role affinity, and role conflict among community pharmacy managers and owners in Canada. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2010, 6, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.; Jensen, M.; Blucher, C.; Lilly, R.; Kim, R.; Scahill, S. Pharmacists as managers: What is being looked for by the sector in New Zealand community pharmacy? Asia Pac. J. Health Manag. 2015, 10, 36. Available online: https://www.achsm.org.au/Portals/15/documents/publications/apjhm/10-01/APJHM_Vol_10_No_1_Complete_Journal.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Dalton, K.; Byrne, S. Role of the pharmacist in reducing healthcare costs: Current insights. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pr. 2017, 6, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hamarneh, Y.N.; Charrois, T.; Lewanczuk, R.; Tsuyuki, R.T. Pharmacist intervention for glycaemic control in the community (the RxING study). BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hamarneh, Y.N.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Curtis, C.; Balint, C.; Jones, C.A.; Tsuyuki, R.T. Community pharmacist targeted screening for chronic kidney disease. Can. Pharm. J. 2015, 149, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, S.K.; Bascom, C.S.; Rosenthal, M.M. Clinical outcomes and satisfaction with a pharmacist-managed travel clinic in Alberta, Canada. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 23, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavcev, R.A.; Waite, N.M.; Jennings, B. Shaping pharmacy students’ business and management aptitude and attitude. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2016, 8, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Fleming, H.; Jones, R.; Menzie, K.; Smallwood, C.; Surendar, S. The inclusion of a business management module within the master of pharmacy degree: A route to asset enrichment? Pharm. Pr. 2013, 11, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perepelkin, J. Redesign of a Required Undergraduate Pharmacy Management Course to Improve Student Engagement and Concept Retention. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012, 76, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Ooi, A.S.H.; Zenn, M.R.; Song, D.H. The Utility of a Master of Business Administration Degree in Plastic Surgery: Determining motivations and outcomes of a formal business education among plastic surgeons. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2018, 6, e1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, J.; Nissen, L. Teaching Pharmacy Students How to Manage Effectively in a Highly Competitive Environment. Pharmacy Education. 1 April 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277945229_Teaching_Pharmacy_students_how_to_manage_effectively_in_a_highly_competitive_environment (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Augustine, J.; Slack, M.; Cooley, J.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Holmes, E.; Warholak, T.L. Identification of Key Business and Management Skills Needed for Pharmacy Graduates. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, D.A. A Management Skills Course for Pharmacy Students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2004, 68, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, D.A. Model for teaching the management skills component of managerial effectiveness to pharmacy students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2002, 66, 377–381. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.134.845&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Katz, R.L. Skills of an Effective Administrator (Harvard Business Review Classics), Harvard Business Review Press. 2009. Available online: https://amzn.asia/d/cELfF1a (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Pickle, H. Personality and Success: An Evaluation of Personal Characteristics of Small Business Managers. Google Books. Available online: https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Xv-l2HQY8poC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=personality+characteristics+and+success+in+business+management&ots=bxIoU37CKe&sig=_rKMPB1sZfTxqgU9yILMUFeLHMI#v=onepage&q=personality%20characteristics%20and%20success%20in%20business%20management&f=false (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Davey, B.J.; Lindsay, D.; Cousins, J.; Glass, B.D. Scoping the required business management skills for community pharmacy: Perspectives of pharmacy stakeholders and pharmacy students. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2022, 14, 909–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottewill, R.; Jennings, P.L.; Magirr, P. Management competence development for professional service SMEs: The case of community pharmacy. Educ. + Train. 2000, 42, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, K.C.; Horne, S. A Didactic Community Pharmacy Course to Improve Pharmacy Students’ Clinical Skills and Business Management Knowledge. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, B.L.; Broedel-Zaugg, K.; Reiselman, J.; Sullivan, D. Assessment of pharmacy students’ perceived business management knowledge: Would exclusion of business management topics be detrimental to pharmacy curricula? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2012, 4, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education: Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. Available online: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Danielson, J.; Besinque, K.H.; Clarke, C.; Copeland, D.; Klinker, D.M.; Maynor, L.; Newman, K.; Ordonez, N.; Seo, S.-W.; Scott, J.; et al. Essential Elements for Core Required Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, M.J. Should Business Training Be a Significant Element of Pharmacy Training? Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorafi, K.J.; Evans, B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2016, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brod, M.; Tesler, L.E.; Christensen, T.L. Qualitative research and content validity: Developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputting, P. Research Methods in Health: Foundations for Evidence-Based Practice, 3rd ed.; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 40–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, L.; Wong-Wylie, G.; Rempel, G.; Cook, K. Expanding Qualitative Research Interviewing Strategies: Zoom Video Communications. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. Data analysis in qualitative research: A brief guide to using Nvivo. Malays. Fam. Physician 2008, 3, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calomo, J.M. Teaching Management in a Community Pharmacy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2006, 70, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, G.L.; Marsh, W.A.; Castleberry, A.N.; Kelley, K.A.; Boyce, E.G. Pharmacists’ Opinions of the Value of CAPE Outcomes in Hiring Decisions. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejzic, J.; Barker, M. ‘The Readiness is All’—Australian Pharmacists and Pharmacy Students Concur with Shakespeare on Work Readiness. Pharmacy Education. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275488883_’The_readiness_is_all’_-_Australian_pharmacists_and_Pharmacy_students_concur_with_Shakespeare_on_work_readiness (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- White, S.J. Will there be a pharmacy leadership crisis? An ASHP Foundation Scholar-in-Residence report. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2005, 62, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.W. Mentorship: The heart and soul of health care leadership. J. Health Leadersh. 2010, 2, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Ye, G.Y.; Choflet, A.; Barnes, A.; Zisook, S.; Ayers, C.; Davidson, J.E. Longitudinal analysis of suicides among pharmacists during 2003–2018. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuade, B.M.; Reed, B.N.; DiDomenico, R.J.; Baker, W.L.; Shipper, A.G.; Jarrett, J.B. Feeling the burn? A systematic review of burnout in pharmacists. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Kelm, M.J.; Bush, P.W.; Lee, H.-J.; Ball, A.M. Prevalence and risk factors of burnout in community pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balayssac, D.; Pereira, B.; Virot, J.; Collin, A.; Alapini, D.; Cuny, D.; Gagnaire, J.-M.; Authier, N.; Vennat, B. Burnout, associated comorbidities and coping strategies in French community pharmacies—BOP study: A nationwide cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.; Johnson, S.; Hassell, K. Managing workplace stress in community pharmacy organisations: Lessons from a review of the wider stress management and prevention literature. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 26, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocic, D.D.; Krajnovic, D.M. Pharmaceutical education state anxiety, stress and burnout syndrome among community pharmacists: Relation with pharmacists’ attitudes and beliefs. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2014, 48, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Ashcroft, D.; Hassell, K. Qualitative insights into job satisfaction and dissatisfaction with management among community and hospital pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2011, 7, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munger, M.A.; Gordon, E.; Hartman, J.; Vincent, K.; Feehan, M. Community pharmacists’ occupational satisfaction and stress: A profession in jeopardy? J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2013, 53, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, V.M.; Corlett, S.A.; Rodgers, R.M. Workload and its impact on community pharmacists’ job satisfaction and stress: A review of the literature. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2012, 20, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhile, I.; Anderson, C.; McGrath, S.; Bridges, S. Is the Global Pharmacy Workforce Issue All About Numbers? Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newlon, J.L.; Clabaugh, M.; Plake, K.S.I. Policy solutions to address community pharmacy working conditions. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksey, J.A.; Knapp, K.K.; Walton, S.M.; Cultice, J.M. Challenges to The Pharmacist Profession from Escalating Pharmaceutical Demand. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.D.; E Fenn, N. The future of pharmacy leadership: Investing in students and new practitioners. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2019, 76, 1904–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.A.; Seuthprachack, W.; Austin, Z. Community pharmacists’ perceptions of leadership. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 1737–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, C.K.; Ascione, F.J.; Bauman, J.L.; Brueggemeier, R.W.; Letendre, D.E.; Roberts, J.C.; Speedie, M.K. Are We Producing Innovators and Leaders or Change Resisters and Followers? Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012, 76, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Pharmacy Council. Accreditation Standards for Pharmacy Programs in Australia and New Zealand 2020 Perfor-mance Outcomes Framework. 2020. Available online: https://www.pharmacycouncil.org.au/resources/pharmacy-program-standards/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Patterson, B.J.; Garza, O.W.; Witry, M.J.; Chang, E.H.; Letendre, D.E.; Trewet, C.B. A Leadership Elective Course Developed and Taught by Graduate Students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013, 77, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatwood, J.; Hohmeier, K.; Farr, G.; Eckel, S. A Comparison of Approaches to Student Pharmacist Business Planning in Pharmacy Practice Management. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepler, C.D.; Strand, L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Health Pharm. 1990, 47, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvey, R.; Hassell, K.; Hall, J. Who do you think you are? Pharmacists’ perceptions of their professional identity. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2013, 21, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, A.M.; Elgizoli, B. Exploring self-perception of community pharmacists of their professional identity, capabilities, and role expansion. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 5, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, T.J. Commentary: Understanding professionalism’s interplay between the profession’s identity and one’s professional identity. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, ajpe8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.; Ashcroft, D.; Hassell, K. Culture in community pharmacy organisations: What can we glean from the literature? J. Health Organ. Manag. 2011, 25, 420–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, B. Organizational Culture and Employee Satisfaction: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2013, 4, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellar, J.; Lake, J.; Steenhof, N.; Austin, Z. Professional identity in pharmacy: Opportunity, crisis or just another day at work? Can. Pharm. J. 2020, 153, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item check-list for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davey, B.; Lindsay, D.; Cousins, J.; Glass, B. “Why Didn’t They Teach Us This?” A Qualitative Investigation of Pharmacist Stakeholder Perspectives of Business Management for Community Pharmacists. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11030098

Davey B, Lindsay D, Cousins J, Glass B. “Why Didn’t They Teach Us This?” A Qualitative Investigation of Pharmacist Stakeholder Perspectives of Business Management for Community Pharmacists. Pharmacy. 2023; 11(3):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11030098

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavey, Braedon, Daniel Lindsay, Justin Cousins, and Beverley Glass. 2023. "“Why Didn’t They Teach Us This?” A Qualitative Investigation of Pharmacist Stakeholder Perspectives of Business Management for Community Pharmacists" Pharmacy 11, no. 3: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11030098

APA StyleDavey, B., Lindsay, D., Cousins, J., & Glass, B. (2023). “Why Didn’t They Teach Us This?” A Qualitative Investigation of Pharmacist Stakeholder Perspectives of Business Management for Community Pharmacists. Pharmacy, 11(3), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11030098