Abstract

This article conducts a corpus linguistics analysis of the dative–genitive subconstruction within the broader context of Old English double object complementation. The ditransitive construction in Old English has traditionally been perceived as a network of alternating subconstructions, including dat-acc, acc-dat, acc-gen, dat-gen, and acc-acc, as the most productive variants. Recent literature has primarily focused on dat-accs and acc-dats because they are the most productive patterns across the history of English, giving also rise to the current ditransitive construction. However, the less productive case frames have received considerably less recent attention. This work, part of an ongoing investigation aimed at creating an OE dat-gen database, builds upon Visser’s list, verified and implemented by findings obtained from a search conducted in the Dictionary of Old English Web Corpus. We obtain 88 verb types and 443 tokens, incorporating 19 new verb types and 260 tokens into the database. More significantly, we offer a detailed description of the conceptual domains and verb classes associated with OE dat-gens, which display a semantics characterized by the presence or absence of actual transfer, as well as transitions from literal to metaphorical transfer, with speech verbs playing a significant role.

1. Aims and Scope

In modern English, the ditransitive construction is characterized by a threefold combination of subject plus objects 1 and 2, corresponding to the semantic roles of agent, recipient, and theme, whether literal or metaphorical—such as in Sally baked her sister a cake and Bob told Joe a story (Goldberg 1995, pp. 141, 143). Word order now strictly governs this construction, favoring the indirect-direct object pattern over its reverse variant, which is primarily confined to Northern Englishes: She gave it the man (Hughes et al. 2013, p. 20; Yañez-Bouza and Denison 2015). A thousand years ago in Old English (OE), the case system allowed for greater variation as functions were marked by case endings. The two double object patterns mentioned above were not only possible but actively used. In fact, one of the most recent contributions to the analysis of double object constructions in OE suggests that acc-dats and dat-accs function as an alternation (Levin 1993) on their own terms (de Cuypere 2015a). Considering the current state as the endpoint, de Cuypere (2015b) recently conducted a study of the OE to-dative construction. Nevertheless, and despite their extremely high productivity, dat-accs/acc-dats represent just one aspect of the case frame system traditionally associated with ditransitives in OE. In what follows, I provide examples for the remaining case frames, which the literature assumes to be less productive (Visser 1963, pp. 621–35; Mitchell 1985, p. 452). These quotations are extracted from Visser (1963, pp. 608–11):

| (1) | & gif man cyninges ðegn beteo manslihtes, […] [acc-gen] | |

| If some.NOM king.GEN.servant.ACC sues murder.GEN | ||

| ‘and if someone accuses a king’s thane of murder, …’ (LawAGu B14.5; eWS) | ||

| (2) | Me hingrode. and ge me ætes forwyrndon; | [dat-gen] |

| I was angry and you.NOM me.DAT food.GEN denied | ||

| ‘I was hungry and you refused to give me food’ (CHom II, 7 B1.2.8; lWS) | ||

| (3) | […] hine axodon þæt bigspell þa twelfe þe mid him wæron. [acc-acc] | |

| him.ACC asked the.parable.ACC the.twelve.NOM who with him were | ||

| ‘the twelve that were with him asked him about the parable.’ | ||

| (Mk WSCp B8.4.3.2; lWS) | ||

In Old English, as observed in examples (1)–(3) above, the ditransitive construction encompasses at least three more distinct case frames: acc-gens, dat-gens, and acc-accs, ordered according to their assumed productivity. This suggests that the scope of the OE ditransitive construction includes a minimum of four major subconstructions, with the possibility of more. In this context, Visser includes another case frame, acc-dat(abl), which is also acknowledged by Mitchell (1985, p. 452). In this frame, the dative functions as ablative, partially overlapping with the instrumental case (Visser 1963, pp. 618–20):

| (4) | Ahrede me hearmcwidum heanra manna |

| Rid me.ACC reproaches.DAT ignoble.men.GEN | |

| ‘Free me from the insults of miserable men.’ (PPs A5; lWS, poet.) |

Finally, de Cuypere (2015a, p. 9) hints at the possibility of finding dat-dat combinations, which would not be surprising given their existence in other historical Germanic languages like Old Norse–Icelandic (Barðdal et al. 2011, pp. 70–76). Although lying relatively nearby, prepositional object constructions also compete with the previous variants in the space of double object complementation:

| (5) | […] þæt se man wandaþ þæt he hi æfre asecgge, | ||

| That the man turns away that he them.ACC ever tell, | |||

| buton se mæssepreost hie æt him geacsige. | [acc-prep] | ||

| unless the.priest.NOM these.ACC to.PREP him.DAT ask | |||

| ‘[…] that the man flinches from ever confessing his sins unless the | |||

| priest may ask about them to him’ (HomS 14 [BlHom 4] B3.2.14; lWS) | |||

| (6) | hu dear se gripan on ða scire ðæt he ærendige oðrum monnum to Gode [dat-prep] | ||

| how dare he seize to the job that he.NOM intercede other.men.DAT to God.PP | |||

| ‘(Or) how dare he (a bishop) seize the responsibility of interceding to God for other | |||

| men he who…’ | (CP B9.1.3; eWS) | ||

The two quotations selected involve two speech verbs operating ditransitively, with the difference being that in these double object constructions, one object is introduced prepositionally. The two patterns, acc-prep and dat-prep, are acknowledged by Visser (1963, pp. 637–39) and Mitchell (1985, p. 452) as alternatives to the case frames analyzed above. As observed in quotation (5), the preposition involved does not necessarily have to match the formal predecessor of the current ‘to’. This extremely variegated framework for double object complementation may even accommodate cases of prep-prep, where both objects are used prepositionally, and instances of triple object complementation (Mitchell 1985, p. 453)—for an example of dat-gen-prep in our corpus, see quotation (31) in Section 5.7 following.

It is against the backdrop of this complex scenario that the present work arises—a corpus linguistics study of dat-gens based on the Dictionary of Old English Web Corpus (DOEWC; Healey et al. 2015). To my knowledge, the recent literature on ditransitives has concentrated on the highest-frequency case frame(s) (acc-dat: de Cuypere 2015a; dat-acc: Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 555–620) while it is pending a much-needed corpus linguistics update of the remaining accepted case frame options and prepositional double object constructions.

In this work, we focus on dat-gens, an area of research relatively neglected during the last few decades. This serves as the first step toward reconstructing the full scope of the OE ditransitive construction. dat-gens are assumed to be less productive than acc-dats, dat-accs, and acc-gens, and their semantics tend to be succinctly described as being related to verbs of granting, thanking, refusing, and depriving. Aiming for the development of a dat-gen database in the near future, we begin with Visser’s list of verb types and tokens, augmenting it through a series of proximity searches in DOEWC, ultimately adding 19 unacknowledged verb types and 260 tokens to the future database.

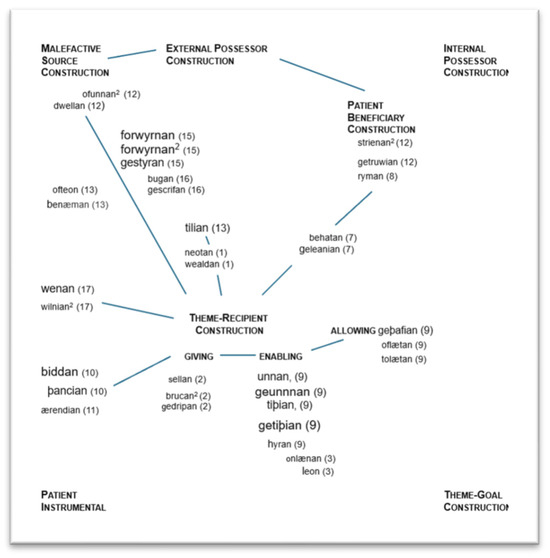

The increase in the dat-gen data, both in terms of verb types and tokens, undoubtedly contributes significantly to our understanding of how this subconstruction operates. A second major finding, derived from the expanded dataset and more noteworthy, is that dat-gens distribute themselves into the same conceptual areas used by dat-accs (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 571–92). Accordingly, all the verb types currently comprising the database are directly related to most of the verb classes and cognitive domains used by dat-accs. While the overlap is not complete, as dat-gens obviously display a distinct semantics of their own, this partial contiguity in semantic space undoubtedly points to the typological validity of the semantic map proposed for the ditransitive construction in a previous contribution (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 591–97).

Barðdal et al. (2011) is the only study on historical Germanic languages that has weighed the strength of the five different case frames (including dat-dats) within the scope of the Old Norse–Icelandic ditransitive construction. We pay special attention to their findings regarding dat-gens, which serve as a starting point for comparison and contrast. We also consider their comprehensive analysis of the partial overlap among the existing subconstructions in their proposed semantic map for the Old Norse–Icelandic ditransitive.

This work is primarily centered around dat-gens. We do not analyze why many of the verb types belonging to our database may also make use of alternating case frames and to what extent. It is indeed not uncommon to find instances of verbs displaying two slots—dat-gen and dat-acc, dat-gen and acc-gen, or acc-gen and dat-acc. In fact, a few verbs may seem to work with three patterns, and fewer still with all options. However, this reality, which is usually perceived as being one of the causes for the eventual collapse of the case frame system in ditransitives, is left out in favor of an account of dat-gens per se, how they work and what they express. Nevertheless, we sometimes formulate some hypotheses concerning the dat-gen/dat-acc alternation in Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3, Section 5.4, Section 5.5, Section 5.6, Section 5.7, and Section 5.8. Finally, since the kind of Diachronic Construction Grammar that we apply here (DCxG; Barðdal and Gildea 2015, pp. 1–50) is inextricably grounded on the syntax-semantics interface, we do not partake of the skepticism that sometimes appears in the literature concerning the impossibility of providing sound classifications for the verb types appearing in each of these case frames.

This article is structured as follows: In Section 2, theoretical background, we begin with a description of the scope of the current ditransitive construction as summarized by Goldberg, which is later enhanced and adapted for the current Germanic languages, Old Norse–Icelandic and Proto-Germanic. Due to the affinity holding between dat-gens and dat-accs, we explain the semantic map proposal for this other subconstruction. In Section 3, overview and data, we survey the most important contributions to the study of dat-gens in OE studies, focusing on Visser’s and Mitchell’s lists. After that, and to open up a comparative perspective, we include a brief analysis of dat-gens in Old Norse–Icelandic. Section 4, methodology, describes the criteria followed for a critical assessment of Visser’s and Mitchell’s lists, also explaining why we chose DOEWC and the type of searches conducted. In Section 5, the scope of the OE dat-gen subconstruction, we proceed to a detailed account of the conceptual domains and verb classes involved, providing an overall explanation for each, followed by the corresponding type lists, number of tokens for each type, and examples. Section 6, analysis and formalization, contains a semantic map proposal for OE dat-gens, which is explained in full. Making use of box formalism, the section also describes the most prototypical constructions in this subconstruction, before proceeding to partially reconstruct dat-gens in North-West Germanic by using a small correspondence set. Finally, in Section 7, we draw conclusions and specify directions for further research.

2. Theoretical Background

In this work, we define a ditransitive construction as a predicate consisting of three components: a subject, indirect object, and direct object, typically corresponding to the roles of agent, recipient, and theme (Goldberg 1995, pp. 141–42). As observed in the previous section, during the OE period, the construction’s scope allowed for this threefold predicate to be structured into each of the five major subconstructional case frames: dat-acc, acc-dat, acc-gen, dat-gen, or acc-acc. Unlike OE dat-accs, dat-gens morphosyntactically feature the direct object in the genitive. As illustrated in examples (7) and (8), the case frame alternates between dat-gen and gen-dat order:

| (7) | & se arcebiscop him þæs tiðude | |

| And the.archbishop.NOM him.DAT that.GEN concede | ||

| ‘And the archbishop granted that to him’ | (Ch 1464 [Rob 80] B15.5.23; WS) | |

| (8) | Ðæs him getiþað drihten crist: | |

| That.GEN them.DAT concede lord.Christ.NOM | ||

| ‘That (healing for ailing men) is granted to them by Christ our Lord.’ | ||

| (ÆCHom I, 4 B1.1.5; lWS) | ||

Visser (1963, pp. 606–7) affirms that the genitive object should be interpreted as some kind of adjunct (for an example, see quotation (9) in Section 3 below). We revisit these two issues in Section 6.

We utilize the framework of Diachronic Construction Grammar (Barðdal and Gildea 2015; Gildea and Barðdal 2023). This approach aims for the syntactic reconstruction of argument structure constructions in the world’s languages (Gildea and de Castro Alves 2020: pp. 47–107), the Indo-European family (Frotscher et al. 2022; Luján and Ruiz Abad 2014; Luján and López-Chala 2020, pp. 336–70), and, more particularly, in Germanic languages (Barðdal 2023; Bucci and Barðdal 2024; Barðdal et al. 2019; Dunn et al. 2017). In this contribution, we partially reconstruct dat-gens in North-West Germanic. Our approach primarily focuses on OE and contrasts results with a few data gathered from Old Norse–Icelandic. It is important to note that our analysis is limited to North-West Germanic, and that the reconstruction of dat-gens presented here is partial and preliminary. Further research will be necessary to fully reconstruct the scope of dat-gens in North-West Germanic and Proto-Germanic.

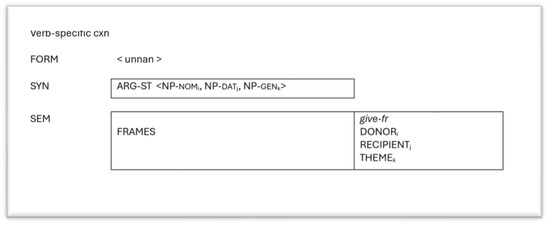

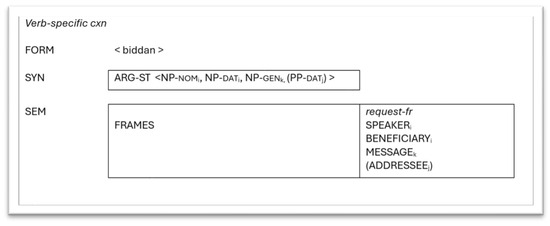

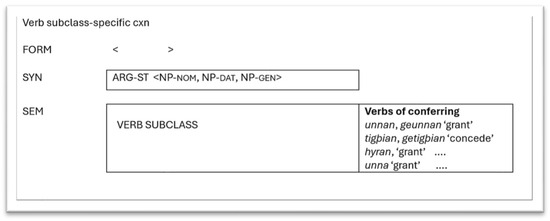

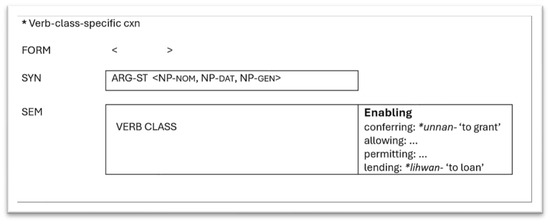

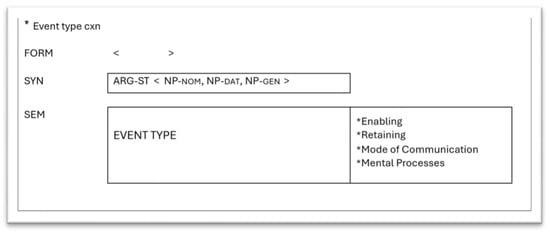

For decades, a widely held belief in structural and generative linguistics has been the impossibility of reconstructing syntax (Barðdal et al. 2020, pp. 9–13; Barðdal and Eythórsson 2020). This conviction stems from the view that syntax lacks inherent semantics, functioning solely as a repository of pattern-based information. Consequently, traditional approaches to comparative reconstruction, which rely on units comprising both form and meaning, have avoided the incorporation of syntax into their analysis. However, in Construction Grammar (CxG), constructions are conceived as form-meaning pairings, facilitating the operationalization of syntactic patterns in reconstructive terms (cf. Michaelis 2012, pp. 134–35, for an expanded definition of construction). In this article, we present a few correspondence sets containing Old English/Old Norse–Icelandic pairs to illustrate the reconstructive method employed. Additionally, following the customary practice in CxG formalism, we will employ boxes to describe the argument structure of the most relevant verb-specific types used in the Old English dat-gen subconstruction.

The current English ditransitive construction is associated with a well-defined and closed list of specific verb classes. In her pioneering 1995 contribution to CxG, Goldberg (1995, p. 38) specifies nine different verb classes.

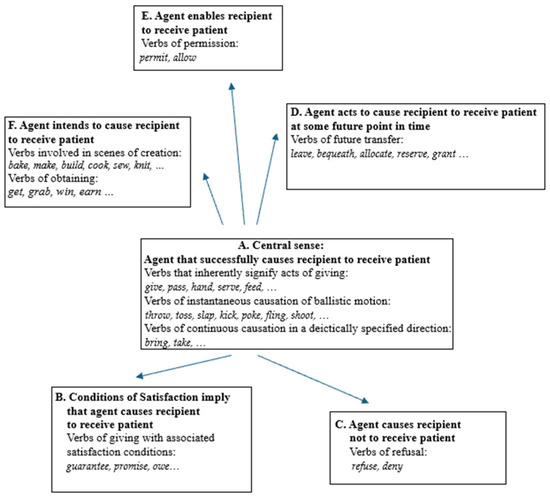

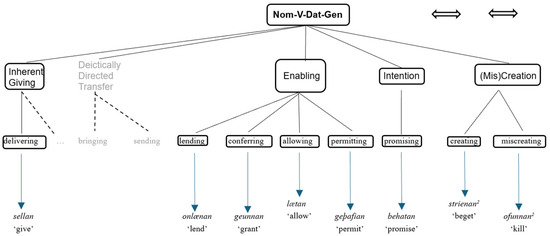

As observed in Figure 1 below, the nine verb classes are divided into core and periphery and are accounted for polysemically. The central sense encompasses verbs of giving, spontaneous, and continuous causation. Depending on their position along the cline moving from A to E, the remaining senses are perceived as more or less prototypical.

Figure 1.

The polysemy of the ditransitive construction (Goldberg 1995, p. 38).

Using a corpus of 18th-century Late Modern English, Colleman and De Clerck (2011) demonstrate that the scope of the ditransitive construction was broader during that period. While the verb classes summarized by Goldberg above were already fully operative, the authors also identify additional phenomena. These include terms for banishment (banish, dismiss, expel), manner of speaking verbs like whisper, as well as benefactive usages such as holding sb the torch, and malefactive units related to verbs of dispossession (spoil).

In the field of Germanic linguistics, and from a constructional perspective, Barðdal (2007, pp. 9–30) demonstrates that the list of verb classes for the ditransitive construction in Icelandic and Proto-Germanic is notably larger, comprising 17 verb classes. We proceed to list and exemplify those absent from English (Barðdal 2007, pp. 12–13) since many of them are included in the semantic map for OE dat-gens to appear in Section 6 below. For clarity, we retain the original numbering of each verb class, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Additional senses of the ditransitive construction in the Germanic languages.

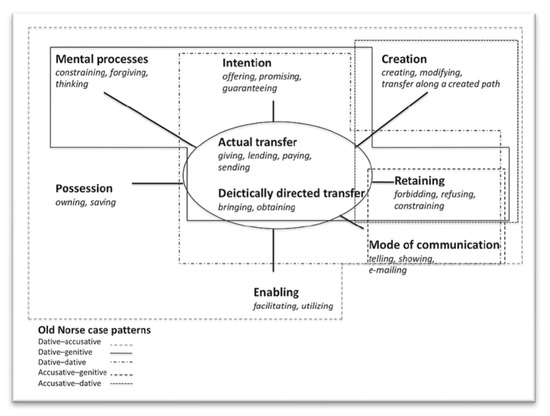

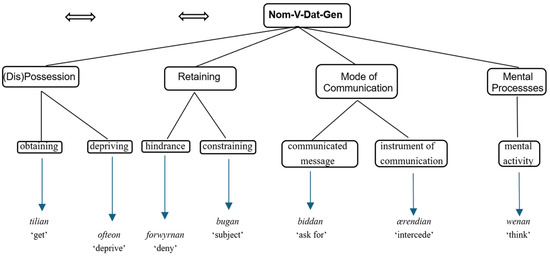

In 2011, a systematic study (Barðdal et al. 2011, pp. 53–104) of all West Scandinavian languages, both present and past, confirmed the existence of the 17 verb classes. Following Croft’s requirement for a lexicality–schematicity hierarchy (Croft 2003), which entails a continuum ranging from verb-specific vocabulary to highly schematic argument structure constructions, the authors categorized the 17 verb classes into nine major conceptual domains: Delivering (1), Enabling (2), Deictically Directed Transfer (3), Intention (4), Creation and Miscreation (5), Possession and Dispossession (6), Retaining (7), Mode of Communication (8), and Mental Processes (9). The taxonomy was validated in a later publication for the Old English dat-acc subconstruction and Proto-Germanic (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 574–91). Also, the data collected for Old English dat-gens in Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3, Section 5.4, Section 5.5, Section 5.6, Section 5.7, and Section 5.8 below confirm a practically identical picture.

It is important to remark the consistency that a lexicality–schematicity approach provides for the analysis of argument structure constructions in historical linguistics because it frames the study of these into a chained sequence arranged from bottom-to-top which makes formal reconstruction possible at all different levels, namely verb-subspecific (prefixed verbs), verb-specific, verb subclass-specific, verb-class-specific, higher-level conceptual domain, and event-type, the most schematic. In this work, we cover the first five levels for OE fully, but the reconstruction obtained for North-West Germanic of the event-type constructional level is as partial as the fragmentary data used from Old Norse–Icelandic (see Section 6 below).

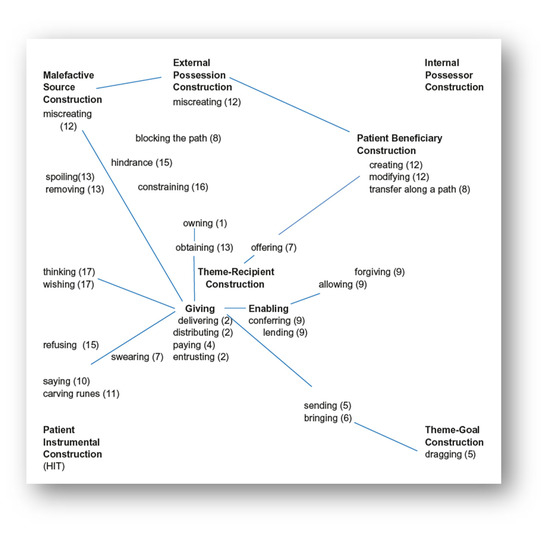

Finally, we also frame the results of this work typologically. In this sense, the findings obtained by Malchukov et al. (2007, 2010) for the current English ditransitive construction encapsulate the former’s scope into a semantic map consisting of core (Theme-Recipient construction), extensions (Patient-Beneficiary construction), and edges (Theme-Goal construction, Internal Possessor construction, External Possession construction, Malefactive Source construction, and Patient Instrumental construction; see Figure 2 below). In a previous publication, we demonstrated how the extremely productive diversity of dat-accs in OE could be represented in such a map, which originally consisted of a small number of verb types, since ditransitivity is not very prolific among non-Indo-European languages. Introduced in Figure 2 below, we distributed the cited 17 verb classes into the following map, which serves for OE (as exemplified below), Gothic, Old Norse–Icelandic, and Proto-Germanic at the same time (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 595–96).

Figure 2.

The semantics of the ditransitive construction in Old English.

There are also some minor differences between the cited 2011 and 2019 proposals. The 2019 semantic map repositions Enabling, placing it at the core of Actual Transfer, together with the different verb classes for giving. Verbs of lending are renumbered from 3 to 9 since they are reclassified as part of Enabling. Finally, class 14, verbs of utilizing, is not present because OE cognates like neotan (‘to enjoy, have the benefit of’) do not use the dat-acc slot. In this work, we take the 2019 semantic map proposal for Old English dat-accs as the starting point of comparison and contrast for the study of Old English dat-gens, assuming that dat-accs (and/or acc-dats) are the most productive subconstructional option (Mitchell 1985, p. 452). We draw the corresponding dat-gen map version, showing for the first time how dat-gens systematically match most of the major areas found for dat-accs and how they specialize in these areas, too.

3. Overview and Data

In this section, we mainly focus on the overviews of Visser (1963, p. 607) and Mitchell (1985, pp. 452, 455–64) since the two analyses shape the contemporary perspective on double object complementation in OE. Also, the list of verb types and tokens produced by Visser and Mitchell’s list of verbal rections make up the starting point of our dat-gen database. Apart from the cited authors, we briefly include Zanchi and Tarsi’s (2021, pp. 31–87) study of valency patterns in Gothic and Barðdal, Kristoffersen and Sveen’s analysis (2011: 53–104) of the ditransitive case frame system in Old Norse–Icelandic.

In the section devoted to syntactical units with one verb, Visser performs an exhaustive analysis of double object complementation (II. Two objects) starting with the study of dat-gens. The construction, according to the author, is frequent in OE and consists of an ‘Indirect Object + Causative Object’. The author seems to restrict the semantics of the indirect object to recipients—we have found addressees, benefactives, malefactives, and experiencers, and combinations of these, too—while at the same time providing an adverbial account of the direct object, which is why he terms it causative. In his words, the direct object expresses ‘a thing or a circumstance which occasions the action or with which the action has concernment’ (Visser 1963, p. 608). Accordingly, he believes that the genitive object in (9) below should not be interpreted literally as a direct object (‘you wouldn’t give me clothes’) but as some kind of adjunct (‘you did not give me concerning clothes’). We partially concur with his analysis, particularly in the case of abstract references, but not as much with literal ones, where it is difficult to escape the recipient-based semantics of this subconstruction.

| (9) | Ic wæs nacod. nolde ge me wæda tiðian |

| I was naked wouldn’t you.NOM me.DAT clothes.GEN concede | |

| ‘I was naked, and you did not consent to clothe me’ (ÆCHom II, 7 B1.2.8; lWS) |

Visser also produces a list of the most frequent verb types: forwyrnan, (ge)styran, (ge)tiþian, (ge)þancian, (ge)unnan, ofteon, ofunnan, tilian and wenan. The author proceeds to select biddan ‘to ask’ as an instance of dat-gen/acc-gen case frame alternation. He somehow seems to relate the cited alternation in particular and the diversity of alternating patterns in general to the gradual dissolution of the dat-gen case frame, which he dates back to the transition from the end of OE to the beginning of Middle English.

Section §677 is an alphabetical list containing verbs operating in this pattern (+3+2) and the tokens that justify their inclusion. I enclose a slightly reduced list comprising 48 verb types after excluding a small group of 11 units. We will revisit this in Section 4, methodology. The definitions are mainly sourced from Bosworth and Toller (1973) or A Thesaurus of Old English (Roberts et al. 1995): ærendian ‘to report, intercede on an errand’, asecean ‘to demand’, behatan ‘to promise’, beniman ‘to take away’, biddan ‘to ask, make a request’, ceapian ‘to buy’, ceosan ‘to choose’, forwyrnan ‘to refuse, deny’, geandwyrdan ‘to answer’, gedripan ‘to drip’, gehatan ‘to promise’, gelyfan ‘to trust, hope’, gescrifan ‘to shrive, impose penance’, gestyran ‘to restrain, withhold’, geswutelian ‘to explain, show’, getiþian ‘to grant, allow’, geþafian ‘to permit, consent’, geþancian ‘to thank, give thanks’, geunnan ‘to grant, allow, concede’, gewyrcan ‘to get by working, gain, obtain’, gewyscan ‘to wish for sth for sb’, gyrnan ‘to desire’, healdan ‘to keep, preserve’, hycgan ‘to think, consider’, oflætan ‘to let off’, ofsceamian ‘to refute, put to shame’, ofteon ‘to take away, deprive’, ofunnan ‘to refuse to grant’, oncweðan ‘to reply, respond’, ondrædan ‘to dread, fear’, onlænan ‘to lend, grant’, onleon ‘to grant the loan of sth’, onwendan ‘to subvert, disturb’, sprecan ‘to say, tell’, styran ‘to prevent sb from sth’, tilian ‘to get after seeking’, tiþian ‘to grant, concede’, þancian ‘to thank, give thanks’, þencan ‘to think’, unnan ‘to grant sb sth’, wealdan ‘to rule, have dominion over’, wenan ‘to think, suppose’, wyrnan ‘to refuse, refrain from granting’, wilnian ‘to desire’, wiþbregdan ‘to withhold, restrain’, wiþcweðan ‘to refuse, reject’, wiþstandan ‘to hinder, prevent’, and wyscan ‘to wish for, desire’. Over 70 years after the publication of Visser’s first volume, the list remains the most substantial contribution to the study of dat-gens to this day, comprising 48 verb types and 183 tokens. As we will see in Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3, Section 5.4, Section 5.5, Section 5.6, Section 5.7, and Section 5.8, the current availability of computerized corpora can help advance the study of this subconstruction.

Mitchell’s overview (1985, pp. 449–64) of double rection complements that of Visser’s. The author lists four main frame options (acc-dat, dat-acc, acc-gen, and dat-gen; dat-accs are taken for granted), noting the existence of a less productive acc-dat (abl), which is one of the major types in Visser, and briefly referring to acc-preps and dat-preps. He relates dat-gens to actions such as ‘thanking, giving, refusing, and taking from’, selecting unnan and þancian for illustration.

In a way, Mitchell’s statements concerning the inconsistency of the rules for simple and double object complementation (1985: pp. 449–450) in OE focus on alternations and how these may have been partially responsible for the dissolution of the ditransitive case frame system. Although he does not explicitly admit it, he appears to share Visser’s viewpoint in this respect as well. In our opinion, his acknowledgment of the fact that ‘the same verb can take different constructions not only in the works of different writers or in different places in the works of the same writers, but even in the same sentence’ (1985: p. 453) should be interpreted as an indirect recognition of the role that case frame alternations like dat-accs/dat-gens play within the wider scope of the OE ditransitive construction. As stated in Section 2, these overlaps, seemingly arbitrary for Mitchell, are partial but systematic. We will demonstrate this in Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3, Section 5.4, Section 5.5, Section 5.6, Section 5.7, and Section 5.8 below.

Mitchell’s list of verbal rections includes 48 verb types. We specify the following 19, not included in Visser’s: geærendian ʿgo on an errand for sbʾ; ascian ʿto ask sb for sthʾ; abiddan, gebiddan ʿto ask, pray for sth for sbʾ; ætbregdan ʿto take sb/sth from sbʾ; dwellan, gedwellan ʿto lead sb astray from sthʾ; friþian, gefriþian ʿto protect sb/sth from sthʾ; tolætan ʿto releaseʾ; leanian, geleanian ʿto reward sb for sthʾ; benæman ʿto deprive sb of sthʾ; secgan ʿto say sth to sbʾ; getilian ʿto strive after, acquire sth for oneselfʾ; truwian, getruwian ʿto clear sb of sthʾ; þafian, ʿto permit sth to sbʾ; and gewenan ʿto hope for sth for sbʾ. We have only been able to retrieve from the corpus some of these terms. This is a topic we will revisit in Section 4, methodology.

Zanchi and Tarsi (2021, pp. 31–87) systematize the range of valency patterns existing in Gothic for three-place predicates from a typological perspective. Their contribution is based on the Valency Patterns Project or ValPaL, which retakes Levin’s belief (1993) that it is possible to provide a semantic classification for verbs by operationalizing their syntax. The project compiles a corpus of 80 basic verbs, studying the patterns associated with each item in 36 different languages. They ultimately develop a database of morphosyntactical patterns and a list of the major alternations for each of the languages covered. The two authors cited utilize an enlarged corpus of 87 verb types and 3447 tokens for their overall study of valency options in Gothic. In their analysis of three-verb predicates (agent, recipient-like, and theme arguments), they draw on previous literature (Ferraresi 2005; Rousseau 2016; Miller 2019) to propose the following case frame system for Gothic, where only major patterns are included: acc-dat, dat-acc, acc-gen, and acc-acc. The authors specify that acc-dats and dat-accs seem to be the highest-frequency pattern, and they also seem to list the case frames in terms of productivity, with acc-gens ranging second and acc-accs last. Finally, they proceed to exemplify the most relevant verbs exhibiting the options listed above (2021: pp. 49–51). Unfortunately for our purposes, since their excellent work systematizes data starting from a selection of 87 verb types and only the major valency patterns, they do not include the study of dat-gens, which seem to be less productive but may also be part of the picture (Miller 2019, p. 162; apud Rousseau 2016). The lack of data in Gothic is one of the reasons why we leave the reconstruction of the dat-gen subconstruction in Proto-Germanic for future works.

Barðdal, Kristoffersen, and Sveen’s contribution (2011: 53–104) is, to our knowledge, the only full-length analysis of the ditransitive case frame system for a historical Germanic language produced so far. The authors divide ditransitivity in Old Norse–Icelandic into five different case frames (dat-acc, acc-dat, acc-gen, dat-gen, and dat-dat), thus adding dat-dats to the case frame system, a slot still unacknowledged in OE. These subconstructions are quantitatively weighed in terms of the number of verb types, displaying an imbalance between the most productive variant (dat-accs: 140 predicates) and the rest: 43, 22, 15, and 15, respectively. They then proceed to exemplify and analyze each of the subconstructions in terms of the verb classes and conceptual domains involved in their usage, instantiating these. For the dat-gen subconstruction, which ranks low in the cited graded sequence (15 verb types), the authors cite the following quotation (2011: 73):

| (10) | Þrándur synjaði honum ráðsins. |

| Þrándur denied him.DAT option-the.GEN | |

| ‘Þrándur denied him that option.’ (Flóamanna saga 1987: 742) |

Synja relates to verbs of future transfer and to one of the major conceptual domains associated with the ditransitive construction, Retaining. The authors find evidence for the following areas of semantic space, displayed in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

The low type frequency dat-gen subconstruction (Barðdal et al. 2011, p. 74).

Old Norse–Icelandic dat-gens are thus used in five major cognitive domains (small caps in Table 2; verbs of obtaining were later reclassified as part of Possession) and six related verb classes. The verb classes involved range from verbs inherently signifying giving or delivering to those for mental activity. For the sake of conveniency, and since we are going to compare reconstructively in Section 6 below, it is perhaps more important to be aware of the semantic gaps applicable to Old Norse–Icelandic dat-gens. In this sense, the article does not include Enabling, Deictically Directed Transfer (verbs of sending; verbs of bringing), Creation (and Miscreation) or Mode of Communication (verbs of communicated message; verbs of instrument of communicated message). Concerning this last cognitive domain, we do find promises (væna e-m e-s) and refusals (synja e-m e-s), but the terms are distributed into different verb classes and domains.

The authors finally compare the semantic scope of the five Old Norse–Icelandic subconstructions, inserting these into a semantic map (2011: 75), see Figure 3 immediately below:

Figure 3.

The five case subconstructions in Old Norse–Icelandic (Barðdal et al. 2011, p. 75).

Drawing upon Croft’s semantic connectivity hypothesis (2003), they provide typological validation to their semantic map proposal encompassing all West Scandinavian languages, past and present, by proving that the five different Old Norse–Icelandic subconstructions accommodate to the same areas currently occupied by languages like Norwegian and Icelandic. The contiguous nature of these five case frame slots, which occupy ‘adjacent regions’ in the semantic map, is particularly noteworthy. Upon examination of the map, it becomes evident that besides the areas that may be exclusive and defining for each subconstruction, there are also significant partial overlaps among them. Notably, some of these overlaps—such as in the case of Actual Transfer—span more than two conceptual domains. While these overlaps might easily escape notice, they are crucial for the comparative analysis of Old English dat-gens and dat-accs. We will now describe the methodological criteria employed in this study.

4. Methodology

This section begins by revisiting Section 2, overview and data, to elucidate the criteria we employed for excluding a small group of verb types and tokens from Visser’s list. Following that, we discuss some of the issues raised by Mitchell’s list of verbal rections for the future OE dat-gen database. Subsequently, we detail the reasons for selecting DOEWC (Healey et al. 2015) as a corpus and proceed to explain the rationale behind the query searches conducted. Finally, the nature of the corpus thus gathered is framed both diatopically and diachronically.

Visser’s list, outstanding as it is, raises some issues regarding the compilation of types and tokens for our database. Since our analysis is exclusively focused on Nom-Dat-Gens, that is, on three-place predicates exhibiting a prototypical agent for the nominative case, we have left out a few tokens in the passive voice and a relatively significant group of verb types operating as what the literature unjustly terms impersonal constructions. Visser must have had his reasons for not categorizing them apart from regular Nom-Dat-Gens (cf. Somers et al. 2024, pp. 1–35, for a related alternation), but since they do not canonically comply with the pattern under study here, we have postponed their study. The list of excluded units exhibiting non-nominatives in the tokens is as follows: beon þearf (wana) ‘to be in need’, earmian ‘to commiserate, feel pity’, hlystan ‘to listen’, hreowan ‘to rue, grieve’, ofhreowan ‘to cause grief or pity’, ofþyncan ‘to cause regret or sorrow’, sceamian ‘to feel shame’, and tweoni(ge)an ‘to doubt’.

We have also ruled out afyrsian ‘to drive away, dispel’ and fyllan ‘to fill, replenish’ because the two quotations adduced are not clear instances of dat-gens. In the case of afyrsian, it is doubtful if the strong feminine nouns ðrowung and forhtung are either genitive or dative: þæt hit (þis fyr) þam geleaffullum afyrsige þære ðrowunge forhtunge ‘so that it (the fire) may drive the believers away from suffering (and) torment’ (ælfric’s Lives of Saints). If the feminine nouns are in the dative, they can be interpreted adverbially. Regarding fyllan, the DOEWC includes an extra word in the sentence, wis, adding ambiguity to the analysis. The quotation is Psalm 145, v. 16: <Onhlidest> ðu þine handa and hi hraðe fyllest, ealra wihta gehwam (wis) bletsunga ‘You open your hand and satisfy the desire of every living thing’. In the quote, the verb is omitted; wis bletsunga can be interpreted as an epithet for God, signifying ‘wise in/with blessings’; ealra withta gehwam may function adverbially, and the Latin input Aperis tu manum tuam, et imples omne animal benedictione shows a different syntactic pattern—accusative plus an instrumental. In our opinion, there is too much uncertainty to consider this type/token valid. In addition, a simple search conducted in DOEWC for fyll (217 matches) did not yield any dat-gen tokens.

We have also skipped one or two cases when the quotation is actually dat-prep, containing a preposition introducing the indirect object: No þæs fela Daniel to his drihtne gespræc soðra worda þurh snytro cræft ‘Daniel could not say so many true words to his Lord using all his wits’ (Dan A1.3). More noticeably, Visser does not provide for semantic definitions of the verb types listed, nor does he discriminate between the different senses of a given term, giving us a straightforward list of tokens for just one unit each time. This involves forwyrnan ‘to refuse, deny’ and ‘to hinder, prevent’; ofteon ‘to take away, deprive’ and ‘to withhold, withdraw’; ofunnan ‘to refuse to grant’ and ‘to wish to deprive sb of sth’; and steoran ‘to prevent sb from’, ‘to reprove, rebuke’, and ‘to correct’. Since each sense relates to a specific verb type, we have proceeded to number the former conveniently. We have also reclassified Visser’s tokens into their corresponding sense for the construction of our database.

We now return to Mitchell’s alphabetical list of verbal rections (1985: 454–464). In Section 3 above we included a group of 19 verb types proposed by Mitchell which were absent from Visser’s. However, we have not been able to validate nine of these, in DOEWC or elsewhere: geærendian ʿgo on an errand for sbʾ; gebiddan ʿto ask, pray for sth for sbʾ; friþian, gefriþian ʿto protect sb/sth from sthʾ; leanian ʿto reward sb for sthʾ; getilian ʿto strive after, acquire sth for oneselfʾ; truwian ʿto clear sb of sthʾ; þafian ʿto permit sth to sbʾ; and gewenan ʿto hope for sth for sbʾ. The searches we have conducted in DOEWC involve the most common base form for each of these terms, and sometimes even more than one base form if the term is productive—gebid- and gebæd for present and past tense options from gebiddan, for instance. We have also checked DOE dictionary entries when available. In this respect, geærendian is highly illustrative of less productive units. The DOE entry includes 17 out of a total of 18 quotations existing for the term. None of the instances included in the entry specify dat-gen usage. We have additionally checked in DOEWC for geær(e)nd-, geerend, and giærend-, but have not retrieved the last remaining token. This leads us to think that this term and many of the units listed above do not use the related pattern. In fact, we are under the impression that except for þafian and getilian, whose related derivative and non-derivative variants are common exponents of dat-gens, this confusion arises from Mitchell’s editing decision of grouping prefixed and unprefixed terms together in the list. If this is so, the corpus we have gathered covers all terms except for friþian, whose pattern seems to be acc-gen.

It is now time to describe why DOEWC has been chosen and the queries conducted, starting with the latter. The main search string involves two members: a personal pronoun word form like him situated in the neighborhood of a genitive singular -es. We have focused on him because pronominality is one of the triggers activating the use of ditransitives nowadays. So, according to probabilistic syntax (Bresnan 2007, pp. 27–96), it would not seem very risky to argue that the situation in OE times may have been similar. For now, we concentrate on just this word form for the third-person singular pronoun option, leaving aside a full analysis of personal pronouns for future works, both regarding the dat-gen pattern and the rest.

Focusing on a personal pronoun word form has its consequences, particularly concerning corpus selection. We have opted to use the DOEWC since it is the only existing tool that allows the retrieval of the totality of him occurrences in the over 3,000,000 OE words distributed among the totality of 3060 extant texts, prose and poetry. Other equally valid and powerful resources like the syntactically annotated York-Toronto-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose (Taylor et al. 2003) contain a selection of prose texts and cannot provide us with a full account for him in all OE works. Pronominality, together with the low productivity of dat-gens, which necessitates compensation with massive amounts of data, are the two major reasons why we chose to use the DOEWC. Additionally, by focusing on the him + -es pattern over other alternatives, we aim to describe the entirety of a selected sample, thus adhering to the maxims of corpus size (McEnery and Brookes 2022, pp. 36–41) and authenticity, too. These considerations somewhat compensate for the forced lack of corpus balance existing in Old English corpora.

Among the research tools available in DOEWC, we chose to utilize proximity searches. As mentioned earlier, our query comprised two elements, him followed by -es, allowed to collocate within a maximal separation of 120 characters. The query returned 11,050 matches, which were then examined individually. Initially, we did not intend to conduct single searches in DOEWC since the dat-gen subconstruction requires two word forms that may be separated in space. Unlike Boolean searches, proximity searches enable us to restrict the distance between query members. We selected a separation of 120 characters rather than 80 or 40 because, considering the relative freedom of word order in Old English, we aimed for our query to be as comprehensive as possible within the limited range derived from searching only for him.

As is evident from the explanation above, one of the elements in our query is a complete word, while the other is just a word ending. We chose the third-person singular masculine pronoun to represent the indirect object because, unlike other options such as me, þe, or us, which can also function as accusatives, him is exclusively dative. Despite some overlap with the third-person plural option, this word form is exceedingly common in Anglo-Saxon records. The second query member is the nominal ending -es. We chose this ending to avoid ambiguity deriving from the high level of syncretism in Anglo-Saxon noun declensions. OE -es can only refer to strong masculine and neuter nouns in the singular, making it the most productive nominal subcategory. Additionally, this ending also covers athematic nouns. For comparison, consider the ineffectiveness that would result from hypothetically selecting -e/-a (strong feminine nouns in singular and plural) or -an (weak nouns in singular and plural).

It is important to note here that the string used operationalizes our search for a more relevant third hidden component—verbs collocating with him and -es. In other words, at this initial stage, our focus is on designing a query that can efficiently retrieve not just an ad hoc specific verb type, but every one of them together with their corresponding tokens. The 11,050 quotations obtained in the DOEWC were like quotations (11) and (12), corresponding to matches 1 and 15, respectively, under the first 100 series:

| (11) | Næs him fruma æfre, or geworden, ne nu ende cymþ ecean drihtnes | |

| Wasn`t him.DAT start ever or become, nor end.NOM come eternal.lord.GEN | ||

| ‘There was never a beginning for Him, and there will be no end to the | ||

| Eternal Lord’ | (GenA,B A1.1; lWS) | |

| (12) | Hwy sceal ic æfter his hyldo ðeowian, bugan him swilces geongordomes? | |

| Why shall I.NOM after his favor obey bow him.DAT such.obedience.GEN | ||

| ‘Why should I serve after his favor, bow to him in such young subjection?’ | ||

| (GenA,B A1.1; lWS) | ||

Example (11) serves as an illustration of the over 10,500 quotations that we have meticulously examined and dismissed, since the query members are not morphosyntactically related or do not render the dat-gen pattern. However, quotation (12) showcases one verb type, bugan ‘to subject, bow, yield’, which fits the pattern. Despite this, the term is unacknowledged as dat-gen, and the pattern is not included in the DOE (see entry for bugan).

While verifying the validity of the 11,050 matches, we also checked those instances from Visser’s list containing him + -es. Nevertheless, Visser’s list is obviously not restricted to this personal pronoun, containing others and noun phrases, too. After completing the analysis of the main proximity search, during a second phase of corpus compilation, we proceeded to validate the rest of Visser’s verb types and tokens not covered yet. We did so by performing single searches in DOEWC which retrieved the exact context for each token. In those few cases when Visser’s token did not clearly conform to dat-gen, we performed proximity searches using other personal pronouns and/or single searches for specific word forms to prove if the term involved operated the pattern. Sometimes, particularly if the term showed a high frequency, it was possible to find dat-gen usages. However, this proved more difficult for units displaying poor productivity, and frequently, combining single and proximity searches did not suffice. We also had a look at the corresponding DOE dictionary entries if available (Healey 2016). Regarding Mitchell’s list, as he does not provide examples in his list of verbal rections, we were able to incorporate four more types into our database, which we acknowledge here: geleanian ‘to reward, recompense’, getruwian ‘to clear sb from sth’, dwellan ‘to lead into error, deceive’, and gedwellan ‘to deceive, lead astray’. Additionally, we also proceeded to detect unacknowledged types we came across through collocations, validating a few of these, too.

During this second phase of corpus compilation, the scope of our search widens, not restricting itself to him + -es instances, but also accepting indirect objects rendered by noun phrases, other genitive endings (gen. pl. -a; gen. sg. (þæ)-s), and a few doubtful cases, usually involving strong feminine nouns whose verb is acknowledged to render the pattern—for instance, unnan ‘to grant’. Therefore, we end up accepting other variants to the main query search, sometimes. After all, the database we intend to create is built upon cumulatively. While this may be irrelevant in terms of the compilation of a future dat-gen database, it matters in terms of frequency. In this work, we confine ourselves to presenting raw frequency, indicating the total number of occurrences found for a given term in our corpus. We refrain from calculating normalized frequencies (Jones 2022, pp. 127–30) for each of the verb types identified using the dat-gen pattern, which might be highly unlikely in numerous cases of low-frequency terms—44 types show only one quotation so far. In the end, we obtained a total of 88 verb types and 443 tokens for the future dat-gen database, adding 19 new verb types and 260 new verb tokens to Visser’s list. This increase in the data, already a contribution to the study of OE dat-gens on its own terms, more significantly allows for the reconstruction of the scope of this ditransitive subconstruction.

Old English is a convenient label for texts from different regions (Northumbrian, Mercian, Kentish, and West Saxon) and periods, with early OE spanning from 700 AD to around 880–890 and late OE covering approximately 900–1150. It is well known that the four manuscripts containing most of the poetry have been preserved in texts written in late West Saxon, despite clear Anglian influences. Similarly, the majority of OE prose texts also show late West Saxon provenance. The lack of records and the influence of the court have thus probably prevented the DOEC from being a balanced corpus in terms of geographic and chronological representation. There is much less representation of the Anglian (Northumbrian, Mercian) and Kentish varieties, and a predominance of late OE (West Saxon) works which are largely prose (Mölig-Falke 2015, pp. 399–402).

The data gathered from the DOEC for this investigation align with the cited predominance of late West Saxon over the rest of the options. However, we have also found many quotations attributed to early West Saxon, which, when gathered together with the late ones, support our findings with a sense of continuity during the whole OE period. For referencing, we have followed the DOE’s classification of OE texts, adding a tag distinguishing between early West Saxon (eWS) and late (lWS). In a few cases when dating is unclear, only the variety has been specified (WS). When the quotations are taken from poetic works, the lWS tag is understood to also include Anglian features. We now turn to describing the verb classes and conceptual domains involved in Section 5.

5. The Scope of the OE dat-gen Subconstruction

In this section, we present the evidence gathered for the dat-gen subconstruction. Assuming the existence of the semantic connectivity hypothesis within a CxG framework, and considering the close relations between the dat-gen and dat-acc subconstructions, we proceed to describe the conceptual domains and verb classes identified for the dat-gen subconstruction in the corpus we have assembled. We start by describing each conceptual domain. After this, we catalog the verb classes and types associated with the given domain, providing raw frequencies for the latter and selecting representative quotations for elucidation.

5.1. Verbs Inherently Signifying Giving and Delivering

This conceptual domain, positioned at the core of the Theme-Recipient construction, exhibits remarkably low productivity (Perek 2020). In the dat-acc subconstruction, there are four verb classes—verbs of giving, entrusting, distributing, and giving back (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 574–76)—with verbs of paying (Class 4 in 2011) being a subclass of giving back. However, we have only been able to provide evidence of the dat-gen subconstruction for the first of these, verbs of giving. We list the verb types included first and then proceed to exemplify sellan and brucan2, which have not been acknowledged as dat-gen usages so far, in quotations (13) and (14).

list of verb types. Verb class 2, verbs of giving: sellan ‘to give’ (1), gedripan ‘to drip’ (1), brucan2 ‘to feed oneself’ (1).

| (13) | Ne syle þu unscyldigra sawla deorum þe þe andettað earme þearfan; | |

| Not give you.NOM innocent.souls.GEN beasts.DAT who you praise miserable.people | ||

| ‘Don’t give to wild beasts innocent souls of those the miserable poor who praise | ||

| you.’ | (PPs A5 [0345 (73.17)]; lWS, poet.) | |

| (14) | he sceall […], forgange flæsc and win, and bruce him oðra metta, | |

| he.NOM will forget food and win and feed him.DAT other.edibles.GEN | ||

| ‘Then he shall fast […], abstaining from food and win and enjoying other food | ||

| for himself.’ | (Conf 2.1 [Spindler A-Y] B11.2.1; lWS) | |

Quotation (13) exemplifies a single search (syl(l)e) conducted in DOEWC to confirm that sellan operationalizes the dat-gen subconstruction. This term serves as the prototype for ditransitive constructions, thus explaining its wide range of meanings as documented in Bosworth-Toller—‘to give sth to sb, pay tribute, offer, furnish, give one thing for another, sell, hand over, deliver, entrust, give up, betray, give an answer, give leave, give punishment, reward, endow, give one’s heart to sb’. Observing this term functioning as dat-gen partially supports the assumption that, as a prototype, sellan must represent all alternating case frames within the ditransitive construction. A proximity search combining one word form (sell, syl(l), seald, etc.) with him in DOEWC produces dat-acc usages in the two figures. On the other hand, brucan2 presents a distinct, more specialized case. This verb should be interpreted as an extension of brucan ‘to enjoy, make use of’, with a specialization in edibles as the referent.

Given the symbolic quantity of verb types (three) and tokens (three, each represented by a single quotation), and the absence of instances for verbs of entrusting, distributing, and giving back (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, p. 609), it is reasonable to conclude that the dat-gen subconstruction was infrequently utilized among the described verb classes.

5.2. Enabling

Occupying a relatively secondary position in modern English (verbs of future transfer under sense D in Goldberg’s scheme), this conceptual domain is repositioned in OE as an integral part of the Theme-Recipient construction alongside verbs of giving (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 576–78). There are four verb groups identified for dat-accs: verbs of granting or conferring, lending (loans are conceptualized as temporal gifts), allowing, and permitting or consenting (2019: 609). This domain exhibits high productivity for dat-gens, encompassing the four cited verb classes and comprising 11 types and 112 tokens out of a total of 443 in the database. Notably, hyran ‘to accede to, grant’ and lætan ‘to allow, let go’ have hitherto been unrecognized uses of dat-gen. We proceed to enumerate the verb types identified and their respective classes, providing examples for many of them due to their significance.

list of verb types. Verb class 9. Verbs of conferring: unnan ‘to grant’ (22), geunnan ‘to grant, concede’ (31), ti(g)þian ‘to grant, concede’ (17), geti(g)þian ‘to grant, concede’ (25), and hyran ‘to accede to, grant’ (1). Verbs of lending (9): onlænan ‘to lend, grant’ (4), onleon ‘to grant the loan of sth’ (4). Verbs of allowing reluctantly (9): lætan ‘to allow, let go’ (1), oflætan ‘to let off’ (1), tolætan ‘to release, let go’ (1). Verbs of permitting or consenting (9): geþafian ‘to permit, consent, approve’ (5).

| (15) | […] wen is, þæt […] he him ne unne naðer ne æhta ne lifes. | |

| norm is that he.NOM him.DAT not grant neither goods.GEN nor life.GEN | ||

| ‘(If the lord then through his servants constantly reminds him of the tax, | ||

| and he (the tenant) is inflexible, opting for withholding the payment | ||

| wrongfully), the norm is that he (the Lord) will not grant him (the tenant) | ||

| either land or life’. | (LawIVEg B14.18; lWS) | |

| (16) | he us georne friðes bæd ac we him nanes ne tiþodon | |

| He us eagerly peace asked but we.NOM him.DAT none.GEN not conceded | ||

| ‘(we sinned against our brother; we saw his anguish), he asked us for peace but | ||

| we granted him none, (hence our troubles now)’ | (Gen [Ker] B8.1.2; lWS) | |

| (17) | Be ðon þe mon sweordes onlæne oðres ðeowe. | |

| About the.free.man.NOM sword.GEN lends other’s.servant.DAT | ||

| ‘Regarding the freeman who may lend a sword to another freeman’s servant.’ | ||

| (LawIneRb B14.4.2; eWS) | ||

| (18) | & se Godes wer nænigra þinga him hyran nolde to þon þe he hine bæd, | |

| god’s.man.NOM no.things.GEN him.DAT accede not about what he him bid | ||

| ‘Then this man of God would not consent to any of the things he had asked him’ | ||

| (GDPref and 3 [C] B9.5.5; eWS) | ||

| (19) | […] þene bid ic Eadmær þæt he him læte þara twegra landa, […] | |

| Then ask I Eadmær that he.NOM him.DAT let go the.two.lands.GEN | ||

| ‘(And if God wills that Eadwold grows up in his father’s time so that he may hold land), then I ask Eadmr to let go of two lands to him, (either at Coleshil or at Eadburgusbury.’ (Ch 1535 [Whitelock 3] B15.6.52; lWS) | ||

Unnan, tiþian, and their derivatives comprise 95 tokens, constituting an overwhelming majority of the usages within this conceptual domain. Except for some sporadic acc-gen usages for tiþian and a late Old English dat-acc instance for geunnan mentioned by Visser (1963, p. 607), verbs of conferring mostly operate within the subconstruction under study. However, verbs of lending, allowing, and permitting or consenting are also active in the dat-acc subconstruction, showing a higher number of types for lending and permitting—including lænan ‘to lend, grant’, gelænan ‘to lend, lease’, leon ‘to lend, grant’, lyfan ‘to give leave, allow’, alyfan ‘to give leave, grant’, þafian ‘to consent to, permit’, and geþafian ‘to favor, support’ (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, p. 609). In this regard, it is conceivable that high-frequency dat-acc verb types like giefan ‘to give, assign’ and/or forgiefan ‘to allow, permit’ could compete with unnan and tiþian. Across both subconstructions, most of the types are predominantly speech verbs or have the potential to function as such.

5.3. Intention

The ditransitive construction in modern usage is primarily focused on the idea of actual transfer, wherein the theme undergoes a movement from an agent to a recipient. In the context of Intention, this transfer typically occurs in the future, although it may not occur at all, as the emphasis lies on the agent’s desire for it to be accomplished. The verbs involved belong to class 7, which includes the so-called verbs of future transfer and those that meet Goldberg’s pragmatic Conditions of Satisfaction (CS; Goldberg 1995, p. 38). We will proceed to list the types, providing examples of some tokens for clarification.

list of verb types. Verb class 7: geleanian ‘to reward, recompense’ (1), beodan ‘to offer’ (1), foresceawian ‘to provide for in advance’ (1), behatan ‘to promise sth to sb’ (3) (CS), and gehatan ‘to promise’ (2) (CS).

| (20) | […] þæt Crist […] þonne geleanað manna gehwylcum ærran gewyrhta. | |

| That Christ.NOM then reward men.GEN.each.DAT earlier.deeds.GEN | ||

| ‘(Then everyone who did not want to believe in the truth before will understand) | ||

| that Christ (through his power) will then reward every one of them according | ||

| to their deeds.’ | (WHom 3 B2.1.3; lWS) | |

| (21) | Se þe […] næfð nænne truwan […] þæt he him foresceawie andlyfene & gewæda. | |

| He who hasn’t no faith that he.NOM him.DAT foresee food.GEN? clothes.GEN | ||

| ‘(Whoever turns to monastic life with double purpose) […] and has no faith in | ||

| that the Lord will foresee sustenance and clothing for him’ | ||

| (ÆCHom I, 27 B1.1.29; lWS) | ||

| (22) | (an his cnapena) eode þa to anum drymen […], and behet him sceattes, | |

| One his.servants went then to a.sorcerer and promised him.DAT money.GEN | ||

| ‘One of his young servants went then to a sorcerer, promising him money (if)…’ | ||

| (ÆLS (Basil) B1.3.4; lWS) | ||

Quotation (20), an excerpt from one of Wulfstan’s homilies, verifies one of Mitchell’s proposed terms, geleanian. We retrieve a new dat-gen type, foresceawian, in (21), from a line coming from Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies. Finally, promises are fulfilled by means of either behatan or gehatan. The number of types and tokens for Intention is indeed very low, four and seven, respectively. The types listed above are all operative in the dat-acc slot, which shows 12 types (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 580–81). The quotation found for beodan in the dat-gen pattern, also attested in the corresponding DOE entry, seems to be more an exception than the norm, since the unit’s unprefixed and prefixed options are commonly rendered by dat-accs. The DOE entries for the rest of the terms seem to give higher productivity to dat-accs. In conclusion, it can be deduced that Intention is sometimes activated for dat-gen usage, but its productivity remains low, just as happens with domain 1 above.

5.4. (Mis)Creation

This conceptual domain comprises two verb-specific classes. The first, 12, encompasses verbs associated with creation and preparation. The second, 8, involves transfer along a path. The distinction between creation and preparation lies in the fact that in the latter case, the theme (accusative object) and, less prototypically, the indirect object (dative) in reflexive ditransitives require preparation or implementation in some manner.

These two verb-specific classes are associated with the Patient-Beneficiary construction. However, they are also operative within the Malefactive Source and External Possession constructions—blocking the path (18) and miscreating (12). The list of types includes strynan2 and ryman, which are currently unattested dat-gens, along with getruwian, dwellan, and gedwellan, terms derived from Mitchell’s list, now validated through newly obtained tokens.

list of verb types. Verb class 12, creation: strynan2 ‘to beget, generate, create’ (1). Preparation: getruwian ‘to clear sb from sth’ (1). Miscreation: ofunnan2 ‘to wish to deprive sb of life’ (3), dwellan ‘to lead into error, deceive’ (1), gedwellan ‘to deceive, lead astray’ (1). Verb class 18, transfer along a path: ryman ‘to clear a way, make room for sb’ (1).

| (23) | Adam […] ongan him to <eðelstæfe> oðres strienan bearnes be bryde, | |

| Adam began him.DAT as family another.GEN beget child.GEN by bride | ||

| ‘Adam (was), when he then began to beget children through the bride into | ||

| the household,..’ | (GenA,B A1.1; lWS, poet.) | |

| (24) | þa seo sæ […] him rymde þreora mila dries færeldes […] | |

| Then the.sea.NOM them.DAT opened three.miles.GEN dry.journey.GEN | ||

| ‘Then the sea (through God’s command) by flowing out cleared for them | ||

| (the Christians) three miles of dry path…’ | (ÆCHom I, 37 B1.1.39; lWS) | |

| (25) | Oft him brogan to laðne gelædeð, se þe him lifes ofonn, | |

| Often them terror to fiery directs he.who.NOM them.DAT life.GEN destroy | ||

| ‘Often someone (the devil) directs fiery terror into them (hermits), he who | ||

| would kill life in them’ | (GuthA,B A3.2; lWS, poet.) | |

In line with our findings for domain 1, the situation in domain 3 exhibits similar characteristics. We have identified a total of six types along with their corresponding eight tokens, indicating the presence of the dat-gen subconstruction within this domain. Unlike with domain 2, we do not observe the same level of productivity. Nevertheless, in contrast to domain 1, we have sufficient evidence to support the existence of both verb classes (12 and 18) and all verb-specific subclasses, with the exception of blocking the path.

The higher productivity of dat-accs compared to dat-gens is evidenced by a substantial list of confirmed types for the former (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 610–11). Among the units functioning as dat-accs, examples include strienan ‘to gain, beget’, cennan ‘to beget, conceive’, and acennan ‘to bring forth, conceive’ for verb class 12 and ryman ‘to clear, make room’ for class 18. However, our data confirm that the remaining terms listed at the beginning of this section are exclusively associated with the dat-gen subconstruction. Quotation (24) illustrates how some of these units combine creation with modification, as exemplified by ryman ‘to make clear by removing obstructions, to clear a way’, according to Bosworth-Toller. Regarding (25), ofunnan2 is defined in lexicographical works as part of dispossession rather than miscreation. In our corpus, we have identified four instances of dat-gen usage, three of which clearly specify ‘lifes’ as a genitive object. This serves as evidence for the unit’s classification as Miscreation in our database.

5.5. (Dis)Possession

In this domain, two major verb classes are prominent: verbs of owning (1) and obtaining (13). Additionally, within class 1, there exist two verb-specific subclasses, delineating the contrast between stative and dynamic verbs, namely owning and getting (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, p. 573). Furthermore, we have identified usages for the two verb-specific subclasses associated with Dispossession, encompassing verbs of removal and spoliation. Notably, instances where types exhibit more than one token do not significantly differentiate between the two usages, removal and spoliation. However, since the two subclasses clearly exist independently within the OE dat-acc subconstruction, we have specified below when both subclasses are applicable.

Domain 5 comprises 14 verb types and 42 tokens, rendering it larger than Giving, Intention, and (Mis)Creation, yet falling short of Enabling. Notably, the types brucan, neotan, strynan, and wyrcan are unattested dat-gen usages. It is essential to recognize that this domain transcends mere expressions of ‘taking away’, as it encompasses both stative and dynamic variants of owning verbs, which are well represented.

list of verb types. Class 1, Possession, verbs of owning, stative: wealdan ‘to rule, have dominion over’ (4), healdan ‘to keep, preserve’ (1), brucan ‘to have and enjoy, make use of’ (2), neotan ‘to have the benefit of, enjoy’ (2). Class 13, verbs of owning, dynamic: tilian ‘to get after seeking’ (13), strynan ‘to get, obtain’ (1), wyrcan ‘to work, attain an object’ (2), gewyrcan ‘to get by working, gain, obtain’ (1), ceapian ‘to buy’ (3), ceosan ‘to choose’ (1). Verb class 1, Dispossession: ofteon ‘to take away, deprive’ (7) (removal, spoliation), benæman ‘to take away’ (3) (removal, spoliation), beniman ‘to take away’ (1) (removal), and ætbre(g)dan ‘to take away’ (1) (removal).

| (26) | ‘ac niotað inc þæs oðres ealles, forlætað þone ænne beam, […] ’ | |

| and enjoy you.two.DAT the.other.all.GEN leave out the.one.tree.ACC | ||

| ‘you can enjoy yourselves with everything else, but you should leave out this | ||

| particular tree,’ | (GenA,B A1.1; lWS, poet.) | |

| (27) | Brihtric […] þohte þæt he him micles wordes wyrcan sceolde, […] | |

| Brihtric thought that he.NOM him.DAT big.words.GEN make would | ||

| ‘(Then this) Brihtric (took 80 ships), (he) thought he would gain acclaim for | ||

| himself,’ | (ChronD (Cubbin) B17.8; lWS) | |

| (28) | sum wælhreow heretoga […] wolde him benæman his lifes and his rices. | |

| a.cruel.chief.NOM would him.DAT rob his.life.GEN and his.kingdom.GEN | ||

| ‘Then a barbarous general (…) (he) wanted to deprive him of his life and | ||

| kingdom’ | (ÆCHom II, 19 B1.2.22; lWS) | |

Quotation (26) illustrates a small subset of units, neotan and brucan, which add the notion of enjoyment to that of possession inherent in recipient-based semantics. This belongs to class 14, a verb-specific option found in contemporary West Scandinavian languages as well as Old Norse–Icelandic (Barðdal et al. 2011). However, in Old Norse–Icelandic, this class is exclusively associated with the dat-acc subconstruction, and in languages like Icelandic, Norwegian, or Faroese, it aligns with the current ditransitive (Barðdal 2007, p. 11; Barðdal et al. 2011, p. 71). In Old English, neotan and brucan typically function with two arguments, operating as monotransitive verbs requiring a genitive object (Ogura 2010), which is the prevalent pattern. Although evidence for their usage with three arguments is limited, it does exist, primarily involving reflexivity. This syntactic–semantic mismatch between Old Norse–Icelandic and Old English warrants further investigation.

The list of dat-acc types for (Dis)Possession is extensive. Among the 25 types, there are some overlaps with dat-gens. Ceosan and geceosan appear to be exclusively used in the highest-frequency option, unless a partitive genitive is involved, as happens with the only token we could retrieve for ceosan here. Ætbre(g)dan and beniman function in both subconstructions. However, despite the limitations of our corpus, stative verbs of class 1 seem to be relatively well-attested in the dat-gen subconstruction. Quotation (28) exemplifies how units like benæman and ofteon are used to express removal (of one’s life) and spoliation (of somebody’s kingdom) interchangeably. Finally, as with Possession in modern Icelandic, OE, and Old Norse–Icelandic dat-accs, all stative and most dynamic variants of owning verbs are straightforward instances of reflexive ditransitives.

5.6. Retaining

Retaining comprises classes 15 and 16, consisting of verbs of hindrance and constraining, respectively. For these verb-specific groups, actual transfer may be rendered difficult or impossible. Despite the difficulty, transfer may eventually occur, typically within a malefactive context. Many constraining verbs express social norms. Goldberg’s verbs of refusal are a subclass within class 15 (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, p. 573).

list of verb types. Verb class 15: forwyrnan2 ‘to hinder, prevent’ (28), wiþstandan ‘to hinder, obstruct, prevent’ (4), wiþbregdan ‘to withhold, restrain, hold back’ (1), ofteon2 ‘to withhold, withdraw’ (4), styran ‘to prevent sb from’ (1), gestyran ‘to restrain, withhold’ (9). Verb class 15, subclass verbs of refusal: wyrnan ‘to refuse, refrain from granting’ (16), forwyrnan ‘to refuse, deny’ (28), ofunnan ‘to refuse to grant’ (1), wiþcweþan ‘to refuse, reject’ (2), and ofsceamian ‘to refute’ (1). Verb class 16: bugan ‘to subject, bow, yield’ (1), gescrifan ‘to shrive, impose penance’ (1), and onwendan, ‘to subvert, disturb’ (1).

| (29) | […] eac se broc, […], ðonne þær micel stan […] him his rihtrynes wiðstent. | |

| too the brook when there big.stone.NOM him.DAT his.course.GEN checks | ||

| ‘(Look,) also the brook, […] when a great stone (rolling down from the high hills | ||

| falls in there, […],) withholding it (the brook) from its right course’ (Bo B9.3.2; eWS) | ||

| (30) | He com hider mid hiwunge, […] ac se cingc him <ælces> þinges forwyrnde. | |

| He came here with trick but the king him.DAT each.thing.GEN refused | ||

| ‘He came here pretending, said (that he would be his man), […] but the king | ||

| refused him everything’ | (ChronC (O’Brien O’Keeffe) B17.7; lWS) | |

The domain is similar in size to (Dis)Possession, comprising 13 types, but larger in tokens, displaying 84 instances. Except for a newly attested type, bugan (refer to quotation (12) above for the corresponding context), and the addition of 42 new verb tokens to the database, the remaining terms and usages can be found in Visser’s list. Classes 15 and 16 are confirmed, but their distribution is not the same, with a clear emphasis on 15, where hindering and denying are extensively covered. Unlike the 12 attested dat-acc types in verbs of constraining (2019: 612), their counterparts in the dat-gen subconstruction do not appear to be equally productive. However, examination of quotation (12) above clearly confirms their presence and connections with social norms. In fact, bugan is very similar to dat-acc alternatives like hyrsumian ‘to obey, serve’ or ðegnian ‘to serve, minister’.

Quotation (29), the only token from Visser’s list included in this section so far, illustrates a non-prototypical non-human agent for hindering. Quotation (30) exemplifies the most productive type, forwyrnan ‘to refuse, deny’ (28 tokens). Despite competition from forbeodan ‘to forbid, prohibit’ and more directly from the family-related geteon wearne ‘to give (sb) a denial/refusal’ (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, p. 612), the 44 valid tokens for wyrnan and forwyrnan, as well as the existence of wiþcweþan and ofunnan, provide sufficient evidence to certify that denying, refusing, or rejecting was primarily performed by the dat-gen subconstruction.

5.7. Mode of Communication

This domain consists of verbs of communicated message (10) and instrument of communication (11). The diversity of types found (22) manifests the various ways in which metaphorical transfer (Reddy 1979; Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Lakoff et al. 1991; Lakoff 1993; Middeke 2022, p. 2) is expressed in OE. The 100 tokens available (nearly one-fourth of the database) further demonstrate the significance of speech verbs in the dat-gen subconstruction. The existence of class 11, verbs of instrument of communication, relates to concepts involving errands, songs, and charms (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 573–74). In this work, only evidence for the role of messengers is found. Additionally, we retrieve the following unattested dat-gen types: æteowian, andwyrdan, manian, and frignan.

list of verb types. Verb class 10: secgan ‘to say’ (3), spræcan ‘to say, tell’ (1), þancian ‘to give thanks’ (23), geþancian ‘to thank’ (4), fægnian ‘to rejoice, applaud’ (1), ætywan ‘to show, reveal’ (2), geswutelian ‘to explain, show’ (1), andwyrdan ‘to respond’ (3), geandwyrdan ‘to answer’ (2), oncweðan ‘to reply, respond’ (1), manian ‘to remind, suggest’ (1), asecan ‘to demand’ (1), styran2 ‘to reprove, chide, rebuke’ (4), styran3 ‘to correct’(1), biddan ‘to ask, make a request’ (36), abiddan ‘to pray for sth to sb’ (1), frignan ‘to ask sb about sth’ (5), rædes axian ‘to ask counsel of sb’ (1), wilnian ‘to desire, ask for’ (5), gewyscan ‘to wish for sth for sb’ (2), gyrnan ‘to desire’ (1). Verb class 11: ærendian ‘to report, intercede on an errand’ (1).

| (31) | an seoc man […] bæd him helpes æt þan mannum þe þær forðferdon. | |

| a.sick.man.NOM asked him.DAT help.GEN to.the.men.DAT that there went | ||

| ‘(Then it happened one day that) an ill man begged for help for himself to | ||

| the men that went there’ | (LS 9 (Giles) B3.3.9; lWS) | |

| (32) | ða […] cweð, feder, is me alyfed þet ic þe mote ohtes fregnan? | |

| Then said father is me allowed that I.NOM you.DAT may something.GEN ask | ||

| ‘Then (he who had heard the heavenly song turned, bowing down onto the floor | ||

| and) said, Father, am I allowed to task you something?’ | (LS 3 (Chad) B3.3.3; lWS) | |

| (33) | And se munuc him ða woplicre stefne georne þæs fultumes þancode | |

| And the monk him.DAT then weeping.voice sincerely the.help.GEN thanked | ||

| ‘And the monk, with a mournful voice, sincerely thanked him for the help’ | ||

| (LS 35 (VitPatr) B3.3.35; lWS < Angl.) | ||

| (34) | we […] witon ðæt se esne ðe ærendað his woroldhlaforde wifes, | |

| we know that the.servant.NOM who pleads his.lord.DAT wife.GEN | ||

| ‘Look! We know well enough that the servant who intercedes for his lord | ||

| about his wife’ | (CP B9.1.3; eWS) | |

The diversity of types is noticeable, encompassing options for saying, showing, telling, explaining, thanking, answering, reminding, asking for or demanding, desiring, etc. The most productive units are related to requests (biddan, frignan) and thanking (þancian, geþancian), but the remaining terms show low outputs. This is in contrast to what happens with Enabling, where there are 114 tokens distributed among a very small number of types.

Mode of Communication displays a diversity of subconstructional patterns. In speech verbs, the usual roles for the Nom and Dat cases are the communicator and addressee, respectively. Consider þancian in quotation (33) and frignan (32) as examples. The former operates exclusively as dat-gen, while the latter alternates between dat-gen and dat-acc, but both exhibit an addressee in the indirect object. However, a verb like biddan, which has 36 tokens in the database, features a Dat case that actually represents a beneficiary matching the agent, not the addressee. In these cases, we are dealing with a dative of interest. Thus, bæd him helpes in (31) means ‘begged for help for himself’. Optionally, the addressee may appear, but when it does, it is introduced prepositionally by æt ‘to, from’—æt þan mannum ‘to the men’. Other verbs like ærendian in quotation (34), wilnian, gewyscan, and gyrnan operate similarly.

In the dat-acc subconstruction, the total number of types rises to 59 (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, p. 613). Many terms alternate between the two subconstructions: secan, sprecan, andwyrdan, ætywan, geswutelian, and geærendian (instrument of communication). Some lexical families are more productive in the dat-acc subconstruction (cweðan, tocweðan, swutelian and geswutelian, ywan and ætywan), but the existence of types like biddan or acsian is marginal among dat-accs. Sometimes, we find idiomatic phrases operating as alternatives to types restricted to dat-gens—don þancas ‘to thank, give thanks’.

We have also validated the presence of benefactive and malefactive usages in Mode of Communication (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019, pp. 589–90). Thanking, the second-highest-frequency term displaying 27 tokens for its unprefixed and prefixed variants, centers around a positive evaluation performed by the communicator. For instance, see quotation (33) from Ælfric’s Lives of Saints. Both types, prefixed and unprefixed, are exclusively linked with the dat-gen subconstruction. The evaluation, however, turns negative in cases like styran2 ‘to reprove, chide, rebuke’. Example (34) is the only attested dat-gen existing for class 11, instrument of communication. The quotation, extracted from King Alfred’s West Saxon version of Gregory’s Pastoral Care, depicts messengers who fall in love with the ladies they were tasked with acquiring. Finally, units like wilnian, gewyscan, and gyrnan also specify the close conceptual links existing between Mode of Communication and Mental Processes, the domain we now turn to studying.

5.8. Mental Processes

Mental Processes encompasses class 17, Mental Activity, and subclasses for verbs of thinking and wishing. We have also found evidence for fearing, but since there is only one type involved, we include the latter under subclass for thinking, leaving this aside for further investigation. Class 17 is constructionally very different from verbs of giving or granting, which display prototypical recipient-based semantics. In this domain, we find Nom experiencers operating different sorts of metaphorical transfer. We have found 13 verb types and 53 tokens. Gewilnian, cepan, and adrædan have not been attested in the dat-gen subconstruction so far.

list of verb types. Class 17. Subclass for thinking: wenan ‘to ween, suppose, think’ (23), hycgan ‘to think, consider’ (1), þencan ‘to think’ (2), gelyfan ‘to confide, trust, hope’ (4), ondrædan ‘to dread, fear’ (13), and adrædan ‘to fear, be afraid’ (1). Subclass for wishing: wilnian2 ‘to wish, desire’ (2), gewilnian ‘to wish, desire’ (1), wyscan ‘to wish for, desire’ (1), unnan2 ‘to wish sth for sb’ (1), cepan ‘to meditate, desire’ (2), unnan yfeles ‘to wish sb ill’ (1), and þencan yfeles ‘to wish sb ill’ (1).

| (35) | […] him gescruncan ealle þa ædra, þæt him mon þæs lifes ne wende |

| him dried up all the veins that him.DAT someone.NOM life.GEN not thought | |

| ‘(Then he began to bathe […] so sweaty that, due to the cold,) all his arteries | |

| dried up to such an extent that nobody thought he would escape with his life’ | |

| (Or 3 B9.2.4; eWS) | |

| (36) | Se ðe oðerne lufað […] nele he him hearmes cepan |

| He who other loves no.want he.NOM him.DAT harm.GEN observe | |

| ‘He who loves another (without pretense) should not wish him any harm.’ | |

| (ÆCHom II, 40 B1.2.44; lWS) | |

| (37) | […] he bið ðonne him self gewita ðæt he wilnað him selfum gielpes; |