Abstract

This paper examines the syntax of additive compound numerals in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), uncovering their unique properties related to number morphology, definiteness, and Case assignment within numeral–noun constructions. These properties necessitate a constituency analysis which reveals that compound numerals have the structure of copulative compounds in MSA, and they are phrases, not functional heads. Drawing on the distinction between inherent, lexical, and structural Cases, this paper posits that the accusative Case on the numerals is an inherent Case, inaccessible to syntactic transformations. Furthermore, the analysis of numeral–noun constructions as numerically quantified phrases (NQPs) explains the assignment of a structural accusative Case or the inherent genitive Case on the quantified noun, based on the overtness of NQ0. Finally, the paper addresses the intriguing question of how NQPs in MSA, despite lacking a nominative Case, can assume the subject position and govern agreement in both verbal and verbless sentences.

1. Introduction

Compound numerals are numbers formed by combining two individual numerals to express two types of arithmetic relations: addition and multiplication. The first type involves the addition of two individual values (e.g., twenty-two is equivalent to 20+2). The second type involves the multiplication of two numerals (e.g., two hundred is equivalent to 2 × 100). Despite the extensive study of individual numerals, compound numerals have received less attention in the literature (Ionin and Matushansky 2004, p. 101). Previous studies adopt two opposing approaches (Žoha et al. 2022); some researchers (e.g., Lyskawa 2020; Willim 2015; He 2015; He and Her 2022) propose that compound numerals are constituents on their own, forming a single, unitary numerical expression that quantifies over the counted entity, whereas other researchers (e.g., Ionin and Matushansky 2004, 2006, 2018) argue that the two numerals within the compound numeral do not form a single constituent to the exclusion of the quantified noun; they exist in a coordination relationship in which each numeral independently modifies the counted entity.

This paper examines additive compound numerals in Modern Standard Arabic1 and supports the former proposal. It focuses on the linguistic properties of these numerals, composed of two words, representing numbers below and equal to ten (e.g., ʾaḥada ‘one’ and ʿashara ‘ten’, yielding ʾaḥada ʿashara ‘eleven’). These compound numerals show unique properties compared to individual numerals. For example, they require the quantified entity to be both singular and indefinite and to bear the accusative Case. Consider the contrast below in (1a–c) with regard to the number morphology, definiteness, and Case of the quantified nominal2:

| 1. | a. ʾaḥad-a | ʿashar-a | rajul-a-n |

| one.masc-acc | ten-acc | man-acc-indef | |

| ‘eleven men’ | |||

| b. rajul-u-n | waḥid-u-n | ||

| man-nom-indef | one-nom-indef | ||

| ‘one man’ | |||

| c. ʿashra-t-u | rijāl-i-n | ||

| ten-fem-nom | men-gen-indef | ||

| ‘ten men’ |

Furthermore, the compound numeral maintains accusative Case on both digits regardless of syntactic context, even in positions where nominative Case would conventionally be assigned. This is evident in some structures involving syntactic transformations like passivization, raising, and exceptional Case marking (ECM). The preservation of Case becomes more peculiar when we consider how the numeral shows typical properties of DPs in constructions involving binding of quantifiers, coordination with other DPs, interaction and agreement with adjectival modifiers and demonstratives. Moreover, the external syntax of the numeral–noun construction at the clausal level further emphasizes its special syntactic properties especially when it occupies a subject position and controls agreement despite lacking a nominative Case.

These peculiarities (among other ones below) emphasize several issues, including, for example, the constituency of compound numerals to the exclusion of the quantified noun, the phrasal nature of the compound numerals, the assignment of three different types of Case (i.e., lexical, inherent, and structural Case) within the numeral–noun construction, and the interaction between the Case assignment and agreement within the clausal spine. These issues are based on the analysis of compound numerals along with the quantified noun as a numerically quantified phrase (NQP) that merges with a determiner to form a regular DP.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a brief overview of the Arabic number system. Section 3 critiques previous approaches and demonstrates the superiority of the constituency analysis for Arabic numerals. Section 4 examines the internal syntax of compound numerals, arguing that that the accusative Case is nonstructural and inherent, based on diagnostic tests proposed by Woolford (2006). Section 5 is divided into three subsections: Section 5.1 examines the semantic and syntactic evidence supporting the view of compound numerals as unified phrasal entities. Section 5.2 discusses the role of the quantified noun in relation to the compound numeral, emphasizing the influence of the functional head NQ0 on Case assignment within NQPs. Section 5.3 explores the mismatch between Case assignment in the NQP and the S-V agreement, proposing that the DP’s ability to control agreement depends on the assignment of a null nominative Case on top of other accusative Cases in the NQP. Section 6 provides the conclusion of the paper.

2. The Arabic Number System: A Brief Overview

The section offers a brief overview of Arabic numerals, categorizing them into three main types: simplex (1–10), compound (11–19), and complex (higher numerals). The simplex numerals are further divided into two groups: adjective-like (‘one’ and ‘two’) and noun-like (3–10). The former occurs post-nominally and exhibits agreement with the numerated noun in definiteness, Case, and gender.

| 2. | a. walad-u-n | wāḥid-u-n |

| boy-nom-indef | one.masc-nom-indef | |

| ‘one man’ | ||

| b. bint-u-n | wāḥid-at-u-n | |

| girl-nom-indef | one-fem-nom-indef | |

| ‘one woman’ |

The discussion on noun-like numerals (3–10) emphasizes three key characteristics. First, they are followed by the counted noun, which must be in the genitive plural form. Second, they demonstrate reverse gender agreement, known as ‘gender polarity’, wherein the numeral takes the masculine marker when defining a feminine noun and vice versa.

| 3. | a. ṯalāṯa-t-u | ʾawlād-i-n |

| three-fem-nom | boys-gen-indef | |

| ‘three boys’ | ||

| b. ṯalāṯ-u | banāt-i-n | |

| three.masc-nom | girls-gen-indef | |

| ‘three girls’ |

The compound numerals (11–19) have three primary peculiarities. Firstly, except for ‘12’ which shows Case variation, compound numerals are consistently marked accusative, regardless of their role in the sentence. Secondly, they necessitate the following counted noun to be singular and accusative. Thirdly, there are two patterns of gender agreement: the first digit exhibits gender polarity, while the second digit (‘ten’) agrees with the gender of the counted noun.

| 4. | ṯalāṯ-at-a | ʿašar-a | walad-a-n |

| three-fem-acc | ten.masc-acc | boy-acc-indef | |

| ‘thirteen boys’ |

The complex numerals can be divided into two groups. The first encompasses the multiples of 10 (20–90), and the second includes the numerals ‘hundred’, ‘thousand’, ‘million’, etc. The complex numerals exhibit common gender, regardless of the gender of the quantified nouns they modify, and they show Case variation depending on their structural position. Also, these numerals require the quantified noun to be singular and accusative when preceded by 20–90 or genitive when preceded by any of the other complex numerals like 100, 1000, etc.

| 5. | a. ʿišr-ūn | walad-a-n |

| twenty-nom | boy-acc-indef | |

| ‘twenty boys’ | ||

| b. ʾalf-u | walad-i-n | |

| thousand-nom | boy-gen-indef | |

| ‘one thousand boys’ |

This section has presented a concise overview of the Arabic number system, but it is essential to acknowledge certain aspects that warrant further attention. Firstly, it is crucial to note that this overview is not exhaustive; for an in-depth and comprehensive exploration of Arabic numerals, see, e.g., (Badawi et al. 2015; Buckley 2004; Ryding 2005; Alhawary 2011). Secondly, the paper refrains from delving into an extensive discussion of gender polarity, a phenomenon inherent in both simple and compound numerals. Previous studies, e.g., (Alqarni 2015, 2021; Alqassas 2017; Al-Bataineh and Branigan 2020), provide detailed analyses of this phenomenon. It is worth emphasizing that a more comprehensive examination and exploration of gender polarity demand a dedicated research paper solely focused on this intricate aspect.

3. Perspectives on the Constituency of Compound Numerals

Previous analyses disagree whether compound numerals are constituents on their own or not. There are two approaches: the nonconstituent account which argues that numerals do not form syntactic units by themselves, separate from the noun they quantify, and the constituent account that considers numerals as constituents on their own to the exclusion of the quantified noun (He and Her 2022). These two contrasting viewpoints are examined in this section to consider their suitability for explaining Arabic compound numerals.

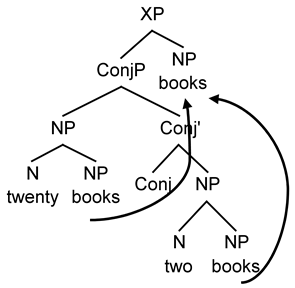

Adopting the nonconstituent approach, Ionin and Matushansky (2006, 2018) provide an interesting view on the process of addition involving compound numerals. They assert that additive numerals in English like twenty-two3, rather than forming a single constituent denoting the sum of numbers, are two distinct constituents in a coordinated expression involving two mechanisms, viz., right node raising and PF deletion. Right node raising refers ‘to a construction in which a shared argument surfaces at the right periphery of a coordinate structure (e.g., Phil loves, but Mary hates, Greek tragedies)’ (Sabbagh 2014, p. 24). Notice in (6) that the quantified nominal is raised from its original position to the right edge of the coordination (Ionin and Matushansky 2006, p. 340; Ionin and Matushansky 2018, p. 128; Meinunger 2015, p. 113).

| 6. |  |

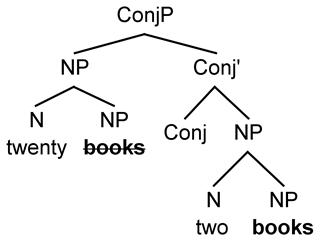

The second mechanism, PF deletion, pertains to a post-syntactic process where the phonological form of the first quantified nominal is deleted, as shown in (7):

| 7. |  |

Ionin and Matushansky’s viewpoint sheds light on the syntactic operations involved in additive numeral–noun constructions. However, although the two proposed mechanisms seem attractive to explain the formation and processing of compound numerals, they are not well-suited to account for Arabic compound numerals, as they do not adequately capture the unique linguistic properties of Arabic numeral constructions. The following are some arguments against adopting these mechanisms to account for Arabic compound numerals.

The use of right node raising (RNR) as a test for constituenthood can be problematic, as Abbott (1976, p. 642) notes, ‘the RNR sentences cannot be used uncritically as tests for constituent structure’. Additionally, Lyskawa (2020, p. 14) points out that ‘RNR usually influences prosody, i.e., there is a pause immediately before the raised constituent’. This expected pause or prosodic influence is not observed by the consulted native speakers. The number morphology further indicates the inadequacy of both RNR and PF deletion. Notice below that ʿashra ‘ten’ requires a plural quantified nominal whereas when it combines with the adjective-like ‘one’ (2a above), it forms a compound numeral that requires the nominal to be with singular morphology.

| 8. | a. ʿashra-t-u | rijāl-i-n | |

| ten-fem-nom | men-gen-indef | ||

| ‘ten men’ | |||

| b. ʾaḥad-a | ʿashar-a | rajul-a-n | |

| one-masc-acc | ten-acc | man-acc-indef | |

| ‘eleven men’ | |||

| http://digilib.uinsa.ac.id (accessed on 14 May 2023) | |||

In addition to number morphology, the RNR mechanism presents challenges to the morphological realization of the quantified noun, specifically, its gender morphology4, definiteness, and Case. Table 1 below illustrates the varying morphological requirements of quantified nominals for different numbers:

Table 1.

The morphological requirements of quantified nominals.

This table shows that the compound numeral requires the quantified noun to have the same gender morphology, to be indefinite, and to bear the accusative Case5. These three requirements are not shared by each numeral separately. These facts render RNR and PF deletion unsuitable for Arabic numerals. Furthermore, both mechanisms anticipate a conjunction like wa ‘and’ between the two numbers, contrary to fact. The conjunction is obligatorily absent in compound numerals. For these reasons, both mechanisms seem unsuited for Arabic numerals6. Furthermore, challenges arise for constructions with coordinated quantified nouns, as illustrated in ‘41 men and women’:

| 9. | waḥid-u-n | wa | ʾrbaʿ-ūna | rajul-a-n | wa | mrʾat-a-n |

| one-nom-indef | and | forty-nom | man-acc-indef | and | woman-acc-indef | |

| ‘41 men and women’ | ||||||

The proposed deletion approach would imply an underlying structure like waḥidun rajulan wa mrʾatan ‘one man and woman’, which does not align with the actual construction. Moreover, extending the analysis to numerals higher than one reveals further complications for the deletion approach. For instance, in ṯalāṯatun wa ʾrbaʿūna rajulan wa mrʾatan ‘43 men and women’ (43 men and women), ṯalāṯatun cannot be followed by singular nouns, and it cannot include the -n declension. These considerations challenge the applicability of a straightforward deletion approach.

The given challenges indicate that both RNR and PF deletion are unsuitable for Arabic compound numerals, and this indicates that the nonconstituent account involving coordination of two numerals along with two quantified nouns is not suitable. This view seems in line with other studies that argue for the inadequacy of the nonconstituency analysis for languages like German, Dutch, Irish (Meinunger 2015), English (He and Her 2022), Mandarin Chinese (He 2015; He et al. 2017), and Polish (Lyskawa 2020; Willim 2015).

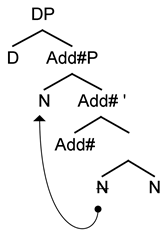

Adopting the alternative account, Al-Bataineh and Branigan (2020) propose an analysis supporting the constituency of the numerals. They suggest that the numerals stand as constituents on their own, independently from the nouns they quantify. Their approach analyzes Arabic compound numerals as two nouns initially formed as an unordered pair {N,N} with an exocentric, symmetric relationship. And, for this symmetric set to be organized hierarchically or linearly at the phonetic form (PF) level, the approach suggests the presence of the functional additive num head Add#, which triggers the raising of one of the two Ns to its specifier position and assigns the accusative Case to both nominals, as shown below:

| 10. |  |

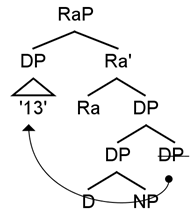

The formed compound numeral as a DP adjoins to another DP representing the quantified noun. The formed structure is also headed by another functional head, called restrictive accusative head ‘Ra’, which has the same properties as the additive number head Add# in triggering the movement of one constituent, viz., the compound numeral, and assigning the accusative Case to the quantified noun, as shown in the following representation:

| 11. |  |

Al-Bataineh and Branigan’s (2020) approach, analyzing numerals as constituents on their own, provides a deeper understanding of how compound numerals interact with the quantified nouns in the larger syntactic framework. However, although their approach offers a more intuitive analysis, it is not adopted here for several reasons. Firstly, the asymmetry-breaking head Add# does not seem theoretically needed. Based on the arguments in Section 4.1, it seems more convenient to analyze the compound numeral as a single compound noun, rather than two separate nouns, and this single compound numeral has an inherent, rather than a structural, accusative Case. Moreover, the semantics of addition can be achieved without a dedicated Case-assigner head. This can be observed in languages like English, where compounds such as thir-teen convey the additive semantics without the need for an additional head. Notice that the additive semantics in compound numerals can be achieved through other means, such as contextual interpretation or syntactic structure. For example, in Arabic numerals involving the conjunction wa ‘and’, as demonstrated in example 13 below, the additive meaning is conveyed without the presence of a functional Case-assigner.

Secondly, this approach does not explain how the Add# assigns Case to both nouns in the unordered set before movement takes place. Thirdly, the assumption that ‘Add#’ triggers the raising of one of the two numerals to its specifier position may appear problematic. This movement would theoretically involve the numeral with the lower value moving to the specifier of the AddP position. However, in principle, either numeral could potentially move, as they are both equidistant in their original position. This is because they form an unordered pair {N,N} with an exocentric, symmetric relationship. Considering the principles of merge, it is crucial to note that more features or heads would be required to filter out incorrect choices such as ‘31’, instead of the correct choice ‘13’. The process involves ensuring that the numerals are correctly ordered to convey the intended meaning. This highlights the complexity of determining which numeral moves in the compound numeral construction. While the assumption of movement triggered by ‘Add#’ provides one possible explanation, it raises questions about how such movement is precisely determined and filtered.

Fourthly, it is unclear how the Add# head assigns accusative instead of nominative Case to nouns lacking the indefinite determiner -n. In such cases, the absence of the determiner typically results in the default assignment of nominative Case, rather than accusative. This default assignment occurs because the determiner serves as the landing site for Case, and its absence creates an imperfect checking domain where only the default nominative Case is available. For example, consider the contrast between (12a) and (12b), where the -n declension is absent in rajul ‘man’. In this context, the structural accusative Case is disallowed, leaving only the default nominative Case to be assigned. This pattern is reminiscent of compound numerals, which also lack the -n declension. Despite this, the nominative Case is not permitted in compound numerals. For more explanation, see Fassi Fehri’s (2012, p. 193) distinction between ‘pure-bare’ nouns, like rajul-u ‘man-nom’, and ‘pseudo-bare’ nouns, like rajul-a-n ‘man-acc-n’.

| 12. | a. yā | rajul-u, | ʾaġliq | al-bāb-a |

| o | man-nom | close.2sg.sbj | def-door-acc | |

| ‘Man, close the door’. | ||||

| b. yā | rajul-a-n, | ʾaġliq | al-bāb-a | |

| o | man-acc-indef | close.2sg.sbj | def-door-acc | |

| ‘Man, close the door’. | ||||

Therefore, the mechanism by which the Add# head assigns accusative Case to nouns without the indefinite determiner -n remains unclear, especially given the default nominative Case assignment in Arabic. This raises questions about the consistency and applicability of the proposed analysis.

Fifthly, this account may face overgeneration issues because it is unclear how the Add# can be restrained not to assign accusative Case to other numerals in constructions involving the semantics of addition in Arabic (as in (13) below) or other languages like English (e.g., twenty-one).

| 13. | qutila | ṯalāṯ-u-n | wa | ʿišrūna | jundy-a-n |

| killed-3sg.subj.pass | three.nom-indef | and | twenty.nom | soldier-acc-indef | |

| ‘Twenty-three soldiers were killed’. | |||||

| https://www.alalam.ir (accessed on 2 June 2023) | |||||

In summary, previous analyses provide valuable frameworks for understanding syntactic operations within compound numerals. Yet, their application to Arabic compound numerals encounters significant challenges in effectively accounting for the data in this paper.

4. The Internal Syntax of Compound Numerals

The rejection of the approaches discussed above (i.e., Ionin and Matushansky 2006, 2018; Al-Bataineh and Branigan 2020) prompts reconsidering the conventional DP structure for numerals. I posit that the structure of the numeral differs from other DPs in Arabic for several compelling reasons. Firstly, combining two nominals to convey a specific numerical value, as in ‘eleven’ above, sets compound numerals apart. In contrast with conventional DPs expressing addition, such as Ahmad wa Salim ‘Ahmad and Salim’, the compound numerals do not involve a conjunction like wa ‘and’. Secondly, in colloquial Arabic, the two components of compound numerals merge into a single word, further distinguishing them from other Arabic DPs (e.g., in Levantine Arabic, the two words denoting ‘eleven’ become the one word ʾiḥdaʿiš). Lastly, while standard DPs with two nominals assign the genitive Case to the second nominal, as well-documented in studies on construct states in Semitic languages (Al-Bataineh 2020), compound numerals assign an accusative Case instead. These unique features necessitate a distinct analysis of numeral syntax. A crucial inquiry arises: How are the two digits in compound numerals structured internally? To answer this question, we need first to explain how the Case is assigned on the two numerals. In the two subsections below, I provide a brief overview of Case types followed by my argument that the accusative Case on compound numerals is not a structural/configurational Case like in other Arabic DPs; it is a nonstructural inherent Case, based on several diagnostic tests.

4.1. A Sketchy Overview of Case Theory: Case Types

Starting from early government and binding theories in the 1980s, the significance of Case as a central theme has been emphasized in generative syntax and morphology. Markman (2010, p. 848) highlights that in Chomsky’s government and binding theory (Chomsky 1981), Case played a crucial role in licensing nouns (NPs) by rendering their theta-roles interpretable at the logical form level. Without Case, NPs would remain uninterpretable and, consequently, grammatically unacceptable. In minimalism, Case is viewed as a linguistic feature associated with and inherently present within NPs that is uninterpretable and needs to be checked off (Markman 2010, p. 850). However, the morphological Cases of NPs are divided into structural and nonstructural, which differ in how they are licensed within a sentence (Chomsky 1981, 1986). Chomsky (1981, p. 170, cited in Markman 2010, p. 860) distinguishes structural Cases (14a,b) that are assigned irrespective of the NP’s theta-role from Cases that are theta-related (14c–e), as follows:

| 14. | a. Nominative—assigned by Infl |

| b. Objective (accusative)—assigned by a transitive verb | |

| c. Genitive—assigned within the NP | |

| d. Oblique—assigned by a preposition | |

| e. Inherent—idiosyncratically assigned by a given verb to its argument |

Generally speaking, structural Case depends on the syntactic or grammatical position of an NP in a sentence, whereas nonstructural Case depends on the inherent characteristics of the NPs conveyed in a particular context. Therefore, as stated by Baker (2015, p. 11), ‘nearly every fully articulated Case theory draws a distinction between structural-grammatical Case and inherent-semantic-quirky Case in one way or another’. However, this distinction is further elaborated by Marantz (1991, p. 24), who outlines four types of morphological Case (for explanation and criticism of this proposal, see, e.g., Markman 2010; Baker 2015). Except for the lexically governed Case, the ‘other three types of Case [15b–d] fall into the domain [of] structural Case’ (Baker 2015, p. 48).

| 15. | Case realization disjunctive hierarchy: |

| a. Lexically governed Case (i.e., Case determined by the lexical properties of a given item) | |

| b. Dependent Case (accusative Case and ergative) | |

| c. Unmarked Case (nominative and genitive) | |

| d. Default Case (assigned to any NP not otherwise marked for Case) |

Another, more recent update on the distinction between Cases is provided by Woolford (2006). She argues that in Case theory, besides the structural and nonstructural Case categorization, two nonstructural Case types exist: lexical and inherent. Lexical Case is idiosyncratic, governed by certain lexical elements. Inherent Case, in contrast, follows a more systematic pattern, aligning with specific sentence positions, such as the inherent dative Case with DP goals and the ergative Case with external arguments. These two Case types exhibit different distribution patterns. Based on this distinction and the diagnostic tests by Woolford (2006), the following section argues that the accusative Case in compound numerals is nonstructural, more specifically, an inherent Case.

4.2. The Inherent Case on Compound Numerals

In this section, I examine the nature of the accusative Case found in compound numerals7 and argue that this accusative Case is best understood as an inherent Case, one that is assigned at the base structure level, known as the ‘deep’ syntactic level (D-structure). Consequently, it remains inaccessible to syntactic transformations. In order to affirm the nonstructural nature of the accusative Case, we can compare a compound numeral with a noncompound one when these numerals are placed in the external subject position. This position is typically associated with nominative Case. The examples below demonstrate that the accusative Case is preserved even when the numeral occupies the subject position. The presence of a nominative Case is precluded, even though the nominal in this position (i.e., the specifier of TP) is assigned the nominative Case (see Section 5.3 for more elaboration on this issue). The preservation of the accusative Case in compound numerals seems in contrast with the presence of the nominative Case in other noncompound numerals like ‘three’. Compare Case markings in the following:

| 16. | a. uṣība | ʾaḥad-a | ʿashar-a | mutaẓāhir-a-n |

| hit.3sg.subj.pass | one-acc | ten-acc | protester-acc-indef | |

| ‘Eleven protesters were injured’. | ||||

| https://www.bbc.com/arabic/live/46506784 (accessed on 20 July 2023) | ||||

| b. uṣība | ṯalāṯa-t-u | mutaẓāhir-īn | ||

| hit.3sg.subj.pass | three-fem-nom | protester-masc.pl.gen | ||

| ‘Three protesters were injured’. | ||||

| https://www.france24.com (accessed on 16 December 2023) | ||||

Additionally, the behavior of compound numerals as objects of prepositions reinforces the assertion that the accusative Case is nonstructural. Notice below that the compound numeral preserves the accusative forms whereas another noncompound numeral like ‘three’ in the same position is marked genitive:

| 17. | a. marar-tu | bi-ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | rajul-a-n |

| passed.1sg.subj | by-one-acc | ten-acc | man.acc-indef | |

| ‘I passed by eleven men’. | ||||

| https://al-maktaba.org/book/31874/29896 (accessed on 16 December 2023) | ||||

| b. marar-tu | bi-ṯalāṯa-t-i | rijāl-i-n | ||

| passed.1sg.subj | by-three-fem-gen | men.gen-indef | ||

| ‘I passed by three men’. | ||||

| https://ketabonline.com (accessed on 16 December 2023) | ||||

Based on these examples, I argue that the accusative Case on numerals is nonstructural as it is independent of the syntactic structure. This conclusion aligns with Baker’s (2015, p. 3) observation that ‘the structural-grammatical Cases are notably not like the inherent-semantic Cases, in that they can change depending on the syntactic context’. The accusative Case in question, however, remains constant regardless of the syntactic environment. Therefore, it is reasonable to categorize it as a nonstructural Case.

Building on Woolford’s (2006) distinction between the two nonstructural Case types, lexical Case and inherent Case which are present in several languages (e.g., Icelandic, German, Basque, Japanese, Faroese, Nez Perce, etc.), I argue that in Arabic the accusative Case on numerals is inherent rather than lexical for several reasons. Firstly, the accusative Case is inherent because it is ‘relatively predictable nonstructural Case’ (Woolford 2006, p. 126) as it aligns with compound numerals exclusively and not with other single-word numerals. This observation, as demonstrated in Al-Bataineh and Branigan (2020), indicates that simple and complex numerals display variable Case markings based on their structural positions within sentences, thus highlighting ‘the relative regularity and predictability’ of the accusative Case on compound numerals. Consequently, it is categorized as an inherent Case.

Secondly, unlike the lexical Case, which is not associated with specific thematic roles, the inherent Case is intrinsically associated with certain θ-positions. Woolford (2006) explains that the inherent Case shows a systematic association between limited and fixed thematic positions like dative and ergative arguments, which follow inherent Case patterns depending on their position in the sentence. For example, the inherent dative Case is typically associated with ditransitive goals, and the inherent ergative Case is typically associated with the agent of an action when the verb is transitive. The same connection seems to exist between this form of the accusative Case and specific thematic roles. Let us first highlight that the inherent Case is different from the structural Case because it fails to bear the final -n declension (called tanwīn in the literature)8. The failure to bear the final -n declension seems associated with specific thematic roles like manner, time, and location, as exemplified in (18):

| 18. | a. Spatiotemporal adverbials (e.g., ṣabāḥ-a masāʾ-a (morning-acc evening-acc) ‘everytime’, bayt-a bayt-a (house-acc house-acc) ‘everywhere’) |

| b. Manner adverbials (e.g., šaḏar-a maḏar-a (scatter-acc dispersal-acc) ‘pell-mell’, bayn-a bayn-a (between-acc between-acc) ‘halfway’) |

The inherent accusative Case (lacking -n declension) is assigned only to a limited set of fixed copulative compounds with thematic roles like manner, time, and location. In these copulative compounds (also termed co-compounds and hyperonymic coordinate compounds), ‘the referent of the whole compound is the sum of the meanings of the constituent lexemes [which] form a “conceptual unit” [that is] more general than the constituents themselves’ (Arcodia 2018, p. 1198). The inherent accusative is assigned to both nouns in the N+N copulative compounds in Arabic (or almurakkab almazjī ‘mixed compound’ in Arabic grammarian terms). Similarly, the accusative Case in compound numerals lacks the -n declension because these numerals form an N+N construction, constituting a unified conceptual unit representing a single numerical value.

A key distinction between adverbials with specific thematic roles at the CP domain and compound numerals is that the former operate within the CP domain, while the latter are assigned roles within the DP domain. This assignment of inherent Case within the DP domain finds support in expressions like bayt-a laḥm-a (house-acc meat-acc) ‘Bethlehem’, ḥaḍr-a mawt-a (house-acc house-acc) ‘Hadramawt’. In both cases, the inherent accusative Case correlates with the obligatory absence of -n declension9.

This discussion leads to a correlation between DP and CP based on the DP/TP analogy (Abney 1987) or the DP/VP parallel (Larson 2014). Specifically, following Larson’s perspective (Larson 2014, pp. 409–10), ‘determiners are semantically contentful and indeed can be viewed as possessing argument structure and valence, counterpart to verbs. […] The semantic parallels between V and D can be further extended to notions of thematic roles and thematic hierarchy’. In short, the inherent nature of the accusative Case seems to correlate with specific thematic roles either at the CP domain for compound adverbials or at the DP domain for compound numerals and common names.

The third argument supporting the characterization of the nonstructural accusative Case in compound numerals as inherent, rather than lexical, focuses on nonstructural Case licensing. Woolford (2006) introduces a distinction between lexical Case, which is licensed only by lexical heads (such as V, P), and inherent Case, which is licensed solely by little/light v heads. In line with this distinction, we posit that the accusative Case, lacking the -n declension, is an inherent Case present in all instances of Arabic mixed compounds. In the CP domain, compound adverbials receive the inherent Case through assignment by a little/light v, as proposed by Woolford (2006). However, within the DP domain, both compound proper names and compound numerals acquire the inherent Case through assignment by a little/light d, which is ‘fully analogous to little v’, as argued by Larson (2014, p. 413). The crucial point is that the accusative Case in compound numerals is analyzed as inherent because its valuation is attributed to functional elements like little v or little d, rather than lexical ones.

The argument that inherent accusative Case is associated with some lexicalized co-compounds may be considered insightful for the Case theory since this Case type is assigned DP internally, not externally. That is, while in typical situations, inherent Case is selected and licensed by functional heads like little v, this inherent Case may have a licensing functional head within the DP because it is associated with the morphological formation of the word itself (i.e., the internal structure of the numeral itself which has a high degree of conventionality and fixity). This argument aligns with other studies on Case. For example, McFadden (2004) argues for the separation between NP licensing, which is a syntactic process, and Case which is a morphological feature determined during the PF phase, separate from the narrow syntax and logical form branches. The disconnection between morphological Case and syntactic licensing is also advocated by Bobaljik (2008). Additionally, the argument for a nonstructural Case within the local DP domain emphasizes the ‘parallelism between noun phrase and sentence’ (Abney 1987, p. 4), as both domains allow Case assignment in analogous ways.

The final two discussion points pertain to the nature of both digits within a compound numeral and the fixed word order. First, the finding that both digits exhibit the inherent accusative Case offers valuable insights into the study of compound words. While they represent a single numerical value semantically, each digit maintains its distinct inherent Case. That is, both digits (e.g., ‘one’ and ‘ten’ in ʾaḥada ʿašra) have the accusative Case, and this seems insightful for the study of compounds since the two words are not treated as one word with regard to Case although, semantically, they denote one numerical value (e.g., ‘eleven’). This aligns with the typical realization of nonstructural Case in the morphology, wherein every element in a DP carries the Case marking (e.g., Asbury 2004, p. 87). Second, in the context of compound numerals, the lower-value digit (e.g., ‘three’) precedes the higher-value one (‘ten’) due to the fixed word order. This fixed order is analogous to the hierarchy of information status observed in copulative compounds. Lohmann (2014) notes a tendency for elements within such compounds to be arranged in order of decreasing information status, with lower-status constituents preceding higher-status ones. This preference for ordering from low to high information status is observed in compound numerals, where the digit with the lower value precedes the one with a higher value. The difference in informational status between ‘three’ and ‘ten’ lies in their respective roles within the compound numeral. While both contribute equally to the numerical value, ‘three’ represents a smaller or less significant quantity compared to ‘ten’. In linguistic terms, ‘three’ occupies a lower position on the numerical scale and carries less inherent significance than ‘ten’. Thus, ‘three’ is considered lower in informational status, leading to its precedence over ‘ten’ in the compound numeral.

In conclusion, the examination of the accusative Case in compound numerals, utilizing diagnostic tests such as passivization, raising, and exceptional Case marking, leads us to posit that it operates as an inherent Case, distinct from the structural Cases observed in other Arabic DPs. We demonstrated through a series of diagnostic tests that the accusative Case in compound numerals remains consistent across various syntactic contexts, indicating its nonstructural nature.

5. Exploring Remaining Issues: Case Assignment and Agreement Mechanisms

This section is divided into three subsections. The first addresses the debate regarding the analysis of compound numerals as heads or phrases and argues for the phrasal analysis, providing evidence related to binding quantifiers, and coordination, among others. The second draws parallels between numeral–noun constructions and quantifier phrases to support their analysis as numeral quantificational phrases (NQPs). This subsection refutes default accusative assignment and dismisses the quantified noun as the numeral’s complement to explain the absence of Case concord. The third explores how NQPs in Arabic influence subject–verb agreement despite lacking a nominative Case. This subsection emphasizes the role of nominative Case marking as a prerequisite for agreement based on the unique behavior of NQPs in the clausal spine.

5.1. Arabic Compound Numerals: Heads or Phrases?

At the heart of our inquiry lies the question: Are compound numerals best analyzed as heads or phrases? Existing literature (e.g., Borer 2005; Danon 2012; Norris 2018; Shlonsky 2004; He 2015; Asinari 2019) often characterizes numerals as functional heads embedded within the extended projection of nouns. This entails their function as heads that project quantifier phrases (QPs) while taking NPs as complements (see Ionin and Matushansky 2018, for references). Another camp of researchers argues for the phrasal nature of numerals in West Slavic languages like Polish (e.g., Willim 2015; Lyskawa 2020). However, adopting the assumption that compound numerals act as heads projecting QPs and governing NPs creates several complications. This section shows that the phrasal nature of compound numerals in Arabic is supported by a range of linguistic evidence, including syntactic transparency, binding quantifiers, coordination, modification capabilities, and locality constraints on word order.

As pointed out by a reviewer, the gender polarity observed in the lower numeral implies that the compound numeral lacks the attributes of a complex head. Complex heads usually entail intricate internal structures that may not be readily apparent. However, the clear-cut gender agreement in the lower numeral aligns with the idea that it does not possess the characteristics of a complex head. This indication implies that the conspicuous gender agreement of the lower numeral functions as a visible syntactic feature, strengthening the characterization of the compound numeral as a syntactically transparent element. Consequently, this reinforces its classification as a phrase rather than a complex head.

Another indication of compound numerals’ phrasal nature is seen through binding quantifiers, where the quantifier kull ‘all’ is bound by the numeral–noun construction, and it requires the pronominal hum ‘them’, akin to regular subjects, which are phrases rather than heads (Citko 2011, p. 125).

| 19. | haʾulāʾ | al-ʾaḥad-a | ʿašr-a | rajul-a-n | kull-u-hum | |

| these | def-one-acc | ten-acc | man-acc-indef | all-nom-3sg.pl.masc | ||

| yaraūna | bi-manḓūr-i-n | waḥid-i-n | ||||

| see.3pl.masc | from-perspective-gen-indef | one-gen-indef | ||||

| ‘All these eleven men see from the same perspective’. | ||||||

| https://www.almaany.com (accessed on 17 July 2023) | ||||||

Furthermore, coordination also shows that the numeral is a phrase that can be adjoined to another phrase. Notice in (20) that ‘the eleven’ is coordinated with the following DP ‘all the remainders’. As noted by Lyskawa (2020, p. 14), ‘if numerals constitute their own phrase, numerals can be coordinated to the exclusion of the quantified NP/DP’.

| 20. | wa | rijʿna | min | al-qabr-i | wa | aḳbarna | |

| and returned.3pl.subj.fem | from def-grave.gen | and | informed.3pl.subj.fem | ||||

| al-ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | wa | jamīʿ-a | al-bāqīn-a | |||

| def-one-acc | ten-acc | and | all-acc | def-remaining-acc | |||

| bi-haḏā | kullih-i | ||||||

| with-this.gen | all-gen | ||||||

| ‘And they returned from the grave and informed the eleven and all the rest about all of this’. | |||||||

| https://st-takla.org/books (accessed on 26 July 2023) | |||||||

Furthermore, this example illustrates that the numeral is preceded by the definite article al- ‘the’, signifying that the numeral is a typical nominal phrase. This observation suggests that the numeral can be headed by a determiner, forming a determiner phrase. Without the numeral being a conventional nominal phrase, it would lack eligibility for a preceding determiner, and conjoining with another determiner phrase would be precluded.

This perspective aligns with the idea that numerals as phrases rather than heads allow for numeral modification, as evident in examples like the following, where the numeral is preceded by the modifier ḥawālī ‘about’. However, it is important to demonstrate that ḥawālī applies specifically to the numeral itself, as it is incompatible with the NP alone, such as in the phrase *tadūmu ħawāli sanawāt ‘they lasted about years’, though this may involve pragmatic considerations as well.

| 21. | wa | ʾḳīr-a-n | marḥalat-u | al-ʿamalyāt-i | ar-rasmyat-i | min | |

| and | finally-acc-indef | stage-nom | def-operations-gen | def-official-gen | from | ||

| ḥawālī | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | sanat-a-n | famā | fawq-a | ||

| about | one-acc | ten-acc | year-acc-indef | and | above-acc | ||

| ‘Finally, the official operations phase lasted for about eleven years or more’. | |||||||

| https://books.google.com.kw (accessed on 20 May 2023) | |||||||

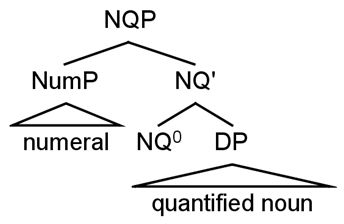

Considering the previous arguments, I assume that the compound numerals are phrases, rather than heads and, consequently, they do not assign Case to the quantified noun. Agreeing with Lyskawa (2020) in her analysis of numerical–noun constructions as numerically quantified phrases (NQPs), I propose that the compound numeral, represented below as a numerical phrase (NmrP), occupies the specifier position of the NQP. Within this structure, the quantified noun occupies the complement position, as shown in the simplified diagram (22), with more details in the following sections.

| 22. |  |

As shown in the examples above, the numeral consistently precedes the quantified noun, as a consequence of its specifier position. This strict word order is further supported by evidence from the Arabic corpus ArabiCorpus10, providing additional empirical validation. Also, searching the corpus results in another related issue which is the absence of any intervening material between the numeral and the quantified noun, and this supports the role of the functional head NQ0 in enforcing a linear proximity between the two phrasal constituents, viz., the numeral and the quantified noun, as it mediates between NmrP and DP and assigns Case to the quantified noun. As evident in all previous examples, the quantified noun is assigned the accusative Case, and this assignment seems consistent, regardless of the structural position of the NQP in the sentence. For example, in (21), even when the NQP occupies the subject position, and the quantified noun has the accusative Case:

| 23. | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | fard-a-n | yaʿīšūna | bi | 50 | diynār-a-n |

| one.acc | ten.acc | individual.acc-idef | live.3pl.masc | on | 50 | dinar-acc-indef | |

| šahry-a-n | |||||||

| monthly-acc-indef | |||||||

| ‘Eleven people live on 50 dinars per month’. | |||||||

| https://arabicorpus.byu.edu/index.php (accessed on 8 May 2023) | |||||||

This suggests that the mediating functional head in the NQP is present and active, and it makes the quantified noun beyond the reach of D and, consequently, the nominative Case does not spread throughout the whole phrase. Since the quantified noun is in the complement position in NQ0, it is beyond the influence of D which normally would cause this DP to take on the nominative Case. This phenomenon seems cross-linguistically valid (see, e.g., Rutkowski (2002) for Estonian, Willim (2015) and Lyskawa (2020) for Polish, and Pesetsky (2013) for Russian).

5.2. NQ0 and Case Assignment in Arabic NQPs

The previous two sections discuss the role of compound numerals in numerically quantified phrases (NQPs), challenging their status as heads responsible for Case assignment. This perspective proposes the existence of the functional head, NQ0, crucial for ensuring consistent accusative Case assignment to the quantified NP across sentence structures. However, these arguments necessitate further elaboration to firmly establish the presence and significance of this functional head. This section provides a comprehensive exploration of NQ0, providing both theoretical and empirical grounding by examining various Case assignment scenarios on the quantified NP.

To begin, the first scenario is that the accusative Case is the default Case assigned to the NP, but this is ruled out by the fact that, in Arabic, the nominative Case holds default status. This is evident in contexts like vocative phrases (Al-Bataineh 2020), pronominal conjuncts, fragment answers, and broad subjects (Doron and Heycock 1999) in (24). Notice that accusative in these contexts is not allowed because in Arabic it is more marked than the nominative Case. In such imperfect checking domains, only the default nominative is allowed, and this refutes the notion of default accusative assignment to the quantified noun.

| 24. | a. yā | rajul-u | ||||||||

| oh man-nom | ||||||||||

| ‘Oh man’ | ||||||||||

| b. ʾanā/ | *ʾiyyāy | wa | missī | ʿišnā | fī | jaḥīm | ||||

| I/ | *me | and | Messi | lived.1pl.subj | in | hell | ||||

| ‘Messi and I/ *me lived in hell’. | ||||||||||

| https://195sports.com (accessed on 17 July 2023) | ||||||||||

| c. saʾl-nā | baʿd-hā | man | min-kum | sayḏhab | maʿ-ī | |||||

| asked.3sg.subj-1pl.obj | after-that | who | among-1pl | will.go | with-1sg.obj | |||||

| l-maḥaṭat | al-waqūd | fa-qult | la-hu | ʾanā/ | *ʾiyyāy | |||||

| to-station | the-fuel | so-said1sg.subj | to-him | I/ | *me | |||||

| ‘After that, we asked, “Who among you will go with me to the gas station?” So I said to him, “I/ *Me.”’ | ||||||||||

| https://www.alriyadh.com (accessed on 17 July 2023) | ||||||||||

| d. hand-u-n | yuqābilu-hā | aṭ-ṭulāb-u | ||||||||

| Hind-nom-indef | meet-3sg.obj.fem | def-students-nom | ||||||||

| ‘The students are meeting Hind’. | ||||||||||

| Literally: ‘Hind, the students are meeting her’. | ||||||||||

The second possibility is to assume that the quantified noun is the complement of the compound numeral, but this is also dismissed because the numeral is phrasal (not a head) and cannot assign Case to its complement. Relatedly, the two phrases, NumP and NP, do not form a structure like a construct state (CS) because the second nominal must be assigned genitive, not accusative, Case. As argued by Ritter (1991, p. 40), among others, ‘CSs are DPs headed by Dgen’, and this abstract Case-assigning head does not carry accusative Case in Semitic languages including Arabic. Similarly, the Case concord cannot take place as well because the numeral does not immediately c-command the quantified NP, as they do not form a single extended projection DP, therefore, the inherent Case feature on the numeral cannot be copied to the quantified NP (for more details on Case concord, see, e.g., Norris 2018).

Based on these arguments, I assume that the accusative Case on the quantified noun is assigned by a mediating head that carries the [acc] feature. Before we discuss its syntactic properties, let us consider the following which shows how the numeral–noun construction can be expressed by a partitive structure involving the preposition min ‘of’. Notice that in both structures the numeral precedes the quantified noun, but the quantified noun is not the same. In the former, it is indefinite and singular and bears accusative Case whereas in the latter it is definite and plural and bears the genitive Case.

| 25. | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | šaḳṣyyat-a-n | ʾakādīmyyat-a-n |

| one.acc | ten.acc | character-acc-indef | academic-acc-indef | |

| ‘eleven academic characters’. | ||||

| https://alwatan.kuwait.tt/articledetails.aspx?id=348959&yearquarter=20142 (accessed on 17 July 2023) | ||||

| 26. | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | min | al-šaḳṣiyyāt-i | al-ʾakādīmyyat-i |

| one.acc | ten.acc | of | def-characters.gen | def-academic-gen | |

| ‘eleven of the academic characters’. | |||||

| https://www.alalam.ir/news (accessed on 17 July 2023) | |||||

These constructions show that in numeral–noun constructions, numerals are similar to quantifiers in having two possible readings11, cardinality/quantity and quantification (see, e.g., Rutkowski 2002). Both (25) and (26) can be interpreted in two ways: either as ‘eleven academic figures’, under the cardinality/quantity reading which implies a reference to the exact number of academics as a whole entity, or as a portion or part of a larger whole involving all academics, under the quantificational reading which implies the existence of unmentioned individuals falling under the same description. These two possible readings are indicative of at least two aspects of the numeral–noun constructions; the noun phrase serves as a restrictor for the numeral, suggesting that the numeral should have scope over it (Rutkowski 2002) and, consequently, the NumP and the NP are asymmetrically arranged and hierarchically related in the syntax, with the NumP in a higher position than the quantified NP. Returning to the examples at hand, since both have the same readings, the presence of the partitive marker min ‘of’ indicates that it is the overt counterpart of the null morpheme that assigns accusative Case. To illustrate, the quantified noun seems to be assigned either the inherent genitive Case carried by the partitive preposition min ‘of’ or the structural accusative Case by the covert partitive marker NQ0.

This argument can be supported by two pieces of evidence. First, the two heads occur in complementary distribution; either the quantified nominal is plural and definite, and in this case, it occurs with the overt partitive marker min ‘of’, or it is singular and indefinite, and it occurs with the covert counterpart NQ0. Since we are dealing with opposite patterns regarding number morphology and definiteness, the syntactic environment does not seem just a matter of c-selection. The second evidence comes from the existence of the accusative partitive Case assigner in Arabic, namely, lā ‘no’, which is similar to NQ0 in selecting a singular and indefinite noun, as exemplified in (27). Notice that lā ʾaḥada has the denotation of ‘no one’, ‘none of the people’, or ‘not a single person’, thus, the partitive marker lā ‘no’ can head a partitive construction (Hoeksema 1995):

| 27. | lā | ʾaḥad-a | yajruʾu | ʿalā | intiqad-i | isrāʾīl |

| no | one-acc | dare.3sg.subj | to | critique-gen | Israel | |

| ‘Not a single one dares to criticize Israel’. | ||||||

| https://www.aljazeeramubasher.net/opinions (accessed on 17 July 2023) | ||||||

Based on the similarity between the partitive marker lā and the null morpheme in selecting an indefinite, singular noun and assigning the accusative Case, it seems that the null morpheme is present in the structure. A reviewer highlights an observation regarding the -n declension, noting its incompatibility with the complement of the partitive marker lā ‘no’ (as seen in lā rajula-(*n)...), which stands in contrast to its presence on the quantified noun in numeral constructions. Despite both lā ‘no’ and NQ0 selecting a singular and indefinite noun and assigning accusative Case, they differ in their categorial selection. Specifically, although both lā ‘no’ and NQ0 do not c-select a definite DP, they differ with regard to the indefinite D -n; NQ0 c-selects an indefinite DP with the -n declension, whereas lā ‘no’ does not. This distinction aligns with Al-Bataineh’s (2021, p. 458) analysis, where lā is interpreted as a negative determiner taking an NP as its complement. This interpretation becomes evident in the following contrast: when lā is separated from the NP, moving to the left periphery, the NP must bear the indefinite article -n. This indicates that lā can exist in two configurations, [DP lā +NP] and lā [DP].

| 28. | a. lā | rajul-a-(*n) | fi | al-bayt-i | ||

| no | man-acc-(*indef) | in | def-house-gen | |||

| ‘No man is in the house’. | ||||||

| b. lā | fi | al-bayt-i | rajul-u-*(n) | |||

| no | in | def-house-gen | man-nom-*(indef) | |||

| ‘No man in the house’. | ||||||

In essence, both NQ0 and lā exhibit similarities by selecting an indefinite, singular noun and assigning the accusative Case. However, a crucial distinction arises in their categorial selections, with lā opting for an NP and NQ0 for a DP. The parallel between these elements becomes more apparent when we draw a comparison with the counterpart of lā, which is mā. Interestingly, mā is accompanied by the partitive preposition min ‘of’, as shown in (29), reminiscent of NQ0, which also employs the same partitive preposition to assign the inherent genitive Case to the quantified noun. This parallelism underscores the intricate syntactic relationships at play within these linguistic structures.

| 29. | mā | min | rajul-in | fi | al-bayt-i |

| no | of | man-acc-(*indef) | in | def-house-gen | |

| ‘No man is in the house’. | |||||

Assuming the correctness of these arguments, we find that the Case marking on the quantified NP pertains to two types: the nonstructural genitive which is assigned when the lexical overt preposition min ‘of’ is present, and the structural accusative which is assigned when the functional covert head NQ0 is present. This indicates that the distinction between the inherent Case and the structural Case is available within the same syntactic structure, but at two different levels or timings: the D-structure and the S-structure. The timing of assigning Cases during the derivation of the NQP directly affects the surface form. Different Case assignments at different levels lead to distinct morphological realizations (Lyskawa 2020, p. 18). Inspired by Norris (2018) and Lyskawa (2020), the following proposal seems to hold in Arabic: assign structural accusative to a noun that is a complement of NQ0 and does not have a lexical genitive Case value by the preposition when the NQP extended projection is complete.

This proposal is comparable to that of Bailyn (2004), since Case alternation depends on the variation in the overtness of the functional head NQ0. However, the ability of NQ0 to assign accusative only when it is null finds analogy in other constructions in Arabic. Consider, for example, that the overtness/covertness of the complementizer ʾinna leads to Case variation (Al-Hroot 1987, p. 20):

| 30. | zayd-u-n | ṭālb-u-n | |

| Zayd-nom-indef | student-nom-indef | ||

| ‘Zayd is a student’. | |||

| 31. | ʾinna | zayd-a-n | ṭālb-u-n |

| comp | Zayd-acc-indef | student-nom-indef | |

| ‘Verily, Zayd is a student’. |

Similarly, Case variation is affected by the overtness of the copula kāna ‘was;’ when it is overt, it assigns accusative to the predicate, but when it is null, no accusative Case is valued (Benmamoun 2000, p. 43).

| 32. | al-walad-u | marīḍ-u-n | |

| def-boy-nom | sick-nom-indef | ||

| ‘The boy is sick’. | |||

| 33. | kāna | al-walad-u | marīḍ-a-n |

| was | def-boy-nom | sick-acc-indef | |

| ‘The boy was sick’. |

Based on these analogies, I assume that the overtness of a head has an influence on Case assignment in Arabic. This is in line with other studies (e.g., Aldridge 2004; Polinsky 2016; Lyskawa 2020) maintaining that the ability of the same functional head to assign two distinct Cases is constrained by the requirement that one of the Cases is nonstructural and the other is structural. This distinction of Cases seems to prevent Case syncretism from taking place; no single Case can be valued in the structure to fulfill the same function. The remaining question here is why the accusative Case in particular is valued by the null NQ0. To answer this question, we need to highlight that the adverbial nominals ‘have a quantitative meaning, which is a point of similarity with numerals’ (Lyskawa 2020, p. 31), and these adverbial nominals always bear the accusative Case in Arabic.

| 34. | ḥallaqat | aṭ-ṭāʾirat-u | saʿat-a-n | mīl-a-n |

| flew.3sg.fem | def-plane-nom | hour-acc-indef | mile-acc-indef | |

| ‘The plane flew for one hour/ one mile’. | ||||

| http://www.alwasatnews.com (accessed on 17 July 2023) | ||||

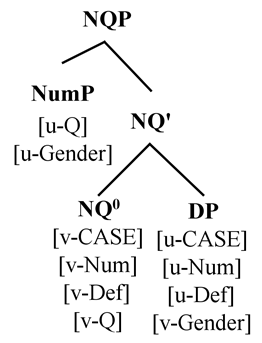

Based on the arguments presented, I assert that the functional head NQ0 plays a crucial role in the syntactic and semantic operations related to quantification in Arabic numeral–noun constructions. Since compound numerals are phrasal, and the head of the entire NQP is the null NQ0, this functional element c-selects the compound numeral as its specifier and the quantified noun as its complement. In the NQP, the null element mediates syntactically between the two phrases in order for the semantics of both measure (cardinality/quantity) and quantification to be expressed at the LF. The NQ0 is endowed with a Case feature which is [acc] or [gen], depending on its overtness. This feature determines the Case of the c-commanded complement DP (i.e., the quantified nominal) only, the compound numeral enters the derivation with its inherent Case already determined in the lexicon. To provide a more comprehensive view of the features involved in the components of the NQP, I suggest the following sets of valued/unvalued12 features:

| 35. | The morphosyntactic features of the quantified nominal a- [u-Case]: The nominal enters the derivation as a Caseless DP and is assigned either [acc] or [gen] by the NQ0. b- [u-Num]: The nominal comes with unvalued [u-Num] feature; it can be either singular or plural depending on the feature carried by the NQ0. c- [u-Def]: the nominal can be either definite or indefinite, depending on the feature carried by the NQ0. d- [v-Gender]: The nominal enters the derivation lexically specified as either masculine or feminine. |

| 36. | The morphosyntactic features of the NQ0 a- [v-Case]: NQ0 can assign either accusative or genitive depending on its overtness. b- [v-Num]: NQ0 comes with a valued [Num] feature which agrees with the matching [u-Num] feature on the quantified noun. Consequently, the nominal surfaces as singular or plural. c- [v-Def]: NQ0 carries this feature and determines the definiteness of the quantified noun. d- [v-Q]: Following Willim (2015), I assume that the NQ0 carries the valued [Q] feature, not the numeral, because it is the element that is associated with the semantics of quantification13. |

| 37. | The morphosyntactic features of the NumP a- [u-Gender]: The compound numeral carries an unvalued [u-Gender] feature because it shows either gender agreement or gender polarity depending on the matching valued feature on the quantified noun. b- [u-Q]: NQ0 comes with an unvalued [Q] feature which agrees with the matching [v-Q] feature on NQ0. Consequently, the cardinality and quantificational readings can be obtained. |

In the light of these assumptions, I suggest the following representation:

| 38. |  |

This representation supposes that the quantified DP enters the syntax with its [v-Gender] feature already valued but its [u-Case], [u-Num], and [u-Def] features as yet unvalued. The DP merges with NQ0, which carries the valued [v-Case], [v-Num], [v-Def], and [v-Q] features to form NQ’. The formed structure merges with the NumP (i.e., the compound numeral) that carries the unvalued [u-Q] and [u-Gender] features to form the NQP. However, to account for the syntactic operations (Agree and valuation) in this structure, I adopt the framework MS-Agree proposed by Ke (2019, 2023a, 2023b).

MS-Agree incorporates minimal search (MS) into the Agree operation, allowing for the independent assignment of search target (ST) and search domain (SD). This accommodates both upward and downward agreement phenomena. Ke (2019, p. 44) defines minimal search (MS) as <SA, SD, ST>, where SA stands for search algorithm, SD represents search domain (the domain SA operates on), and ST denotes search target. Given SD and ST, SA matches against every head member of SD to find ST. If ST is found, it returns the heads bearing ST; otherwise, it proceeds to further steps in the algorithm.

Returning to our representation, the DP carrying unvalued [u-Case], [u-Num], and [u-Def] features is a valuee that initiates the MS-Agree to look for the valuer (the one that bears corresponding valued features). MS-Agree assigns the NQ0 as the SD because it is the sister/co-member of the value, in accordance with the locality constraint of c-command and the intervention condition (Baker 2008). MS-Agree locates the ST within the SD, identifying the NQ0 with the matching feature attributes. Consequently, the minimal search is terminated, leading to valuation between the two syntactic objects, DP and NQ0. Given their mutual accessibility (see, e.g., Bjorkman and Zeijlstra 2019, p. 536), valuation results in copying the value of the ST (i.e., NQ0) in the search output to the corresponding unvalued features in the trigger (i.e., DP).

Another round of MS-Agree is triggered by the NumP, which carries the unvalued features [u-Q] and [u-Gender]. These features activate minimal search to locate the SD that is locally available. In this case, MS finds the sister of the trigger (NQ’), designating it as the SD. Within this SD, two potential valuers emerge: NQ0 bearing the corresponding valued [v-Q] feature, and DP carrying the matching valued [v-Gender] feature. MS-Agree successfully identifies both STs, prompting the termination of minimal search. Consequently, the valuation process, triggered by the unvalued features on NumP, is initiated, resulting in the values [Q] and [Gender] of the STs being copied to the corresponding unvalued features in the trigger. The adoption of the MS-Agree approach offers at least two advantages: minimal search and valuation as two distinct components in MS-Agree arise naturally from the definition of MS; and MS-Agree determines which syntactic objects will be returned by the search algorithm (Ke 2023b, pp. 6–7).

To conclude, this section shows that NQPs are headed by NQ0 which ensures consistent accusative and genitive Case assignment to the quantified noun. This argument is based on the refutation of the accusative Case being assigned by default and the quantified noun acting as the complement of the compound numeral. Instead, this section proposes that NQ0 serves as a mediator between the compound numeral and quantified noun, drawing on the parallel between partitive and numeral–noun constructions which also correlates with the distinction between structural and nonstructural Case assignment on the quantified nominal.

5.3. Resolving the Mismatch between Case Assignment and Agreement

The final issue to be addressed pertains to the NQP’s capacity to occupy a subject position and control agreement despite its lack of a nominative Case. Arabic exhibits subject–verb agreement, and this agreement corresponds with the subject in the CP requiring nominative Case assignment. This correlation is not exclusive to Arabic, as observed by Ganenkov (2022, p. 779), ‘a connection between agreement and Case assignment is commonly assumed for accusative languages’. This section seeks to explain how the two phenomena—agreement and nominative Case assignment—are interrelated, emphasizing that numeral–noun constructions do not deviate from this correlation.

Initially, let us examine the behavior of the NQP as a typical subject in verbal sentences and as a regular topic in verbless nominal sentences. In (39–41) extracted from ArabiCorpus, we observe that the NQP functions as the subject in both active and passive sentences:

| 39. | marra | ʿalā | taḥrīr-i | al-kawaīt-i | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | ||

| passed.3sg.subj | on | liberation.gen | def-Kuwait.gen | one-acc | ten-acc | |||

| ʿām-a-n | ||||||||

| year-acc-indef | ||||||||

| ‘Eleven years have passed since the liberation of Kuwait’. | ||||||||

| 40. | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | mussalaḥ-a-n | wa | madanyy-a-n | qutilū | ||

| one-acc | ten-acc | armed-acc-indef | and | civilian-acc-indef | killed.3pl.subj.pass | |||

| fī | al-jazāʾir-i | |||||||

| in | def-Algeria-gen | |||||||

| ‘Eleven people, both armed individuals and civilians, were killed in Algeria’. | ||||||||

Similarly, in verbless nominal sentences, the NQP functions as a topic, as demonstrated in (41).

| 41. | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | kilūgrām-a-n | min | al-kuwkāyīn | al-ḳām-i |

| one-acc | ten-acc | kilogram-acc-indef | of | def-cocaine.gen | def-raw-gen | |

| muḳabaʾat-u-n | dāḳila | kaʾs-i | al-ʿālam-i | |||

| hidden-nom-indef | inside | cup-gen | def-world-gen | |||

| ‘Eleven kilograms of raw cocaine were hidden inside the World Cup’. | ||||||

Further evidence supporting the function of the NQP as a standard subject comes from its ability to adjoin to another nominative DP in a coordinated phrase and to bind a reflexive pronoun, as shown in (42a,b). Notice, in (42a), how the NQP conjoins the nominative DP mraaʾatun waḥidatun ‘one woman’, and in (42b), how it binds the reflective anaphora nafsuhum ‘themselves’ and associates with the pronominals hum ‘they’ and allaḏīna ‘who’.

| 42. | a. min bayni-him | ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | rajul-a-n | |

| among-3pl.obj.gen | one-acc | ten-acc | man-acc-indef | ||

| wa | mraʾat-u-n | waḥidat-u-n | |||

| and | woman-nom-indef | one-nom-indef | |||

| ‘Among them are eleven men and one woman’. | |||||

| https://www.youm7.com (accessed on 11 December 2023) | |||||

| b. ʾaḥad-a | ʿašar-a | šāʿir-a-n | hum | nafs-u-hum | |

| one-acc | ten-acc | poet-acc-indef | 3pl.sub.masc.nom | self-nom-3pl.masc | |

| allaḏīna | waradat | ʾasmāʾ-u-hum | sābiq-a-n | ||

| who.3pl.masc | mentioned.3sg.sub.fem.pass | names-nom-3pl.nom | previously-acc-indef | ||

| ‘Eleven poets are the same individuals whose names were mentioned earlier’. | |||||

| https://www.aleftoday.org/article.php?id=977 (accessed on 11 December 2023) | |||||

Based on the examples provided, it is evident that the NQP, functioning as a typical DP, is engaged in subject–verb agreement. This indicates that the NQP appears to merge with a determiner to form a DP. However, two critical points necessitate emphasis before we consider how this formed DP enters the derivation and determines agreement at the clausal level. First, the TP is projected in both verbal sentences and verbless nominal sentences. For example, as highlighted by Al-balushi (2012, p. 1), verbless sentences in Arabic are ‘finite clauses (encoding [T], [φ], and [Mood]) composed of a topic and a predicate’. Consequently, agreement plays a role in all types of Arabic sentences. Second, since the DP formed of a D and NQP is not merely an NP with D, consideration must be given to how the phi-features on the quantified nominal become accessible for the formed DP.

Winchester (2019, p. 5) offers two potential scenarios: either ‘the features of these adjoined heads percolate up to DP so as to be easily accessible for agreement [or they] are simply accessible as features of the adjoined heads within D’. Both possibilities hold validity and, to present a unified analysis, I assume that the formed DP abides by two conditions; category inheritance (Keine 2019, pp. 38–39) and the No Tampering Condition (Chomsky 2008, p. 138). Category inheritance ‘states that if a head takes a complement that is part of the same extended projection, the category of the resulting constituent is a function of both the category of the head and the category of its complement’. This implies that the D head encompasses all the subfeatures of the lower projections (NumP, NQ’, and NP) within the same extended projection DP. This assumption aligns with the No Tampering Condition (Chomsky 2008, p. 138), which mandates that ‘the merge of X and Y leaves the two SOs unchanged’. Thus, the merger of NQP and D does not change the inherent characteristics of the elements involved, rather, the merger of the two elements yields the preservation of the information encoded as morphosyntactic features.

Drawing on these points, let us consider how the DP involving NQP interacts with T in agreement and Case assignment within the clausal spine. As discussed earlier, the quantified noun bears either an accusative or genitive Case based on the nature of NQ0, whether it is functional or lexical. Rezac (2008) suggests that in such situations, the assigned Case becomes inaccessible from the outside. Similarly, the accusative Case on the compound numeral is also inaccessible because it is an inherent Case. Consequently, once D merges with the NQP, percolation of Case from either the quantified noun or the numeral is disallowed. Bearing in mind that ‘a Case assigned in a lower position does not block further Case assignment’ (Bejar and Massam 1999, p. 74), the formed DP possesses a D that requires its Case feature to be valued once the DP is in a checking configuration with a functional head, which is, in this case, T. Put differently, the formed DP appears in a position to control agreement only when it is c-commanded by T.

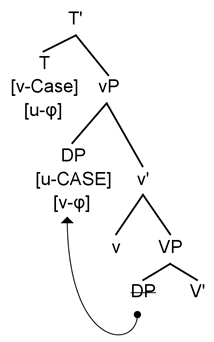

Building on the insights from Ganenkov (2022), I propose that the DP receives nominative Case from T since it occupies the highest structural position within the c-command domain of T, as shown below (some elements are omitted for brevity):

| 43. |  |

Once the DP has the nominative Case, it becomes structural in the sense that it becomes recognized by T to participate in syntactic operations related to agreement. In the representation given in (43), T is endowed with the valued [v-Num], which is responsible for nominative Case assignment on the DP. Since T carries unvalued [u- φ] features, it assumes the role of the valuee and initiates the MS-Agree to search for the valuer, namely, the element bearing corresponding valued features. MS-Agree assigns the DP as the SD because it is contained within the sister node vP. This process leads to the identification of the ST within the SD, i.e., locating the D with the matching feature attributes. As a result, minimal search concludes, paving the way for valuation between the two syntactic objects T and D, both of which are accessible to each other for valuation purposes. This results in copying the value of the ST (i.e., the φ-features) in the search output to the corresponding unvalued φ-features in the trigger T.

From a morphological perspective, this proposal posits that the covert (unpronounced) nominative Case appears on top of the overt (pronounced) Cases carried by the numeral and the quantified noun. This implies that the nominative Case overlays other lexical, inherent, or structural Cases within the DP. Consequently, regardless of the overt Cases within the DP, the nominative Case overwrites other previously assigned Cases. The assignment of the nominative Case makes the DP available and active for agreement without it, the DP would be invisible to minimal search and valuation. As explained by Ganenkov (2022, p. 785), ‘only DPs in structural Cases can trigger agreement, though the relation between Case and agreement is reverse compared to what is assumed under the agreement-based theory of Case assignment’. This perspective regards Case assignment as obligatory and a prerequisite for subject–verb agreement, rather than an automatic outcome of valuation of agreement features on T.

This view finds support in various studies cited in Ganenkov (2022, p. 742). For example, Baker (2015) argues that Case assignment to a DP can occur independently of agreement, demonstrated in instances of accusative Case assignment and object agreement, as well as the assignment of ergative Case to the subject of a transitive verb. This indicates that Case assignment does not always align with traditional notions of subject and object. Additionally, Bobaljik (2008) discusses scenarios where agreement with a DP depends on the Case it bears, rather than solely its structural position relative to the agreeing functional head. This phenomenon, termed ‘Case discrimination’ by Preminger (2014), implies that agreement is influenced by the Case marking of the DP. Drawing on the dissociation between Case assignment and agreement (Baker 2015) and the Case-dependent agreement (Bobaljik 2008), we can assert with greater confidence that in the clausal spine the DP’s capacity to control agreement is determined by its nominative Case marking through a Case assignment operation by T.

To conclude, this section shows how the NQP, despite lacking a nominative Case, functions as a subject and influences agreement in Arabic. The NQP’s role as subject in verbal and topic in verbless nominal sentences supports its role in agreement. Based on the finiteness of nominal sentences, and requirements like category inheritance and the No Tampering Condition, it is shown that the capacity of the DP to govern agreement relies on nominative Case assignment. This emphasizes the pivotal role of nominative Case marking as a prerequisite of agreement.

6. Concluding Remarks

This paper examines the syntax of additive compound numerals in Arabic, aiming to explain the underlying syntactic mechanisms governing their unique properties. It becomes evident that these numerals present challenges to prior approaches, necessitating an alternative analysis that accounts for the challenging issues surrounding number morphology, definiteness, and Case assignment within numeral–noun constructions. By adopting a constituency analysis, this paper argues against the applicability of syntactic operations such as right node raising (RNR), PF deletion, or the projection of functional elements within the structure. Upon close examination of the internal numeral, it is revealed that the two numerals form a compound word, aligning with the structure of other copulative compounds in Arabic.

Drawing on the distinction between inherent, lexical, and structural Cases, the paper proposes that the accusative Case on the numerals is best understood as an inherent Case invisible to syntactic transformations. Additionally, the interaction between compound numerals and various linguistic elements such as quantifiers and adjoined DPs strongly suggests the phrasal nature of the numeral. This interpretation finds further support in the inflexibility of word order and the absence of Case concord between the numeral and the quantified noun.

Moreover, the paper advocates for an analysis of numeral–noun constructions as numerically quantified phrases (NQPs), where the NQ0 serves as a mediator between the numeral and the quantified noun, offering both cardinality and quantificational readings of the entire NQP. It also assigns either the functional accusative Case or the inherent genitive Case based on its morphological realization as either a null functional head or an overt lexical head. The influence of the overtness of the head on Case assignment is supported by other analogous constructions in Arabic involving Case assigners like complementizers and copulas.

Finally, the paper addresses the question of how NQPs in Arabic, despite lacking a nominative Case, can take up the subject position and govern agreement in both verbal and verbless sentences. It argues that the interaction between the DP (resulting from the merger of D with NQP) and T is the outcome of T assigning a null nominative Case due to the structural position of DP within the c-command domain of T. This nominative Case renders the DP active for agreement.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are accessible in the ArabiCorpus at [https://arabicorpus.byu.edu/, accessed on 12 May 2024]. The data extracted from Arabic websites were obtained from publicly available resources, with specific URLs referenced after each example in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See, for example, (Buckley 2004; Badawi et al. 2015) for in-depth discussions on Modern Standard Arabic grammar. | ||||||||||||