Abstract

This paper presents empirical evidence to support the so-called syntactization of discourse, that is, the projection of relevant pragmatic features in the narrow syntax. In particular, it analyses deictic inversion in English, a construction which is used by the speaker to point at a proximal or distal location and bring the addressee’s attention to an entity related to that location (e.g., Here comes the bus). It offers a novel account of this construction, which takes it to be an evidential strategy in a language that does not have standard evidential markers; this evidential status explains its main differences with locative inversion, a construction with which it is pragmatically and structurally related. Deictic inversion therefore receives a natural explanation in a framework that maps syntax with the speech act and introduces in the derivation pragmatic information about the participants in the communicative exchange and about the source of the information for the proposition asserted.

1. Introduction

In recent years, generative grammarians have amply discussed whether pragmatic features should be configurationally represented, and, if so, which pragmatic information should be syntactically encoded in terms of specific categories and structural relations. In this respect, there exists general consensus that the different types of topics and foci must be syntactically represented, along with the type of information they convey.

Together with an articulation of the left/right periphery to represent information structure, there has been another productive line of research that explores the mapping between syntax and the speech act, that is, the need to introduce in the narrow syntax the discourse participants speaker/addressee, along with the notions of commitment, evidentiality and evaluation in which they are involved. Investigations along these lines have successfully shown the effects of various aspects of pragmatic prominence in the syntactic structure and have explained in a principled way a number of phenomena whose grammatical properties are crucially determined by the discursive status of the proposition (cf. among others, Ross 1970; Cinque 1999; Smith 2000; Speas and Tenny 2003; Speas 2004; Haegeman and Hill 2013; Haegeman 2014; Miyagawa 2022; Krifka 2023).

This paper goes in this direction, and here I propose a novel analysis of the so-called deictic inversion (DI) in English which hinges on an explicit codification of the relevant features active in the communication exchange and incorporates some of the insightful observations about the form and function of the construction made in Lakoff (1987).

Deictic inversion is used by the speaker to point at a proximal or distal location and bring the addressee’s attention to an entity related to that location. It therefore requires a perceptual field shared by both the speaker and the addressee, and this, as Green (1982, p. 130) has claimed, is what makes it basically an oral language construction:

| (1) | Here comes the bus. |

| (2) | Here comes Max with his new girlfriend. |

| (3) | There goes Mary. |

| (4) | There goes a beautiful car. |

As I will argue below, the structural properties of examples such as (1)–(4) (taken from Lakoff 1987) can be accounted for in terms of valuation of a pragmatic feature in the speech act projections of the sentence by a lexical verb, something that not only explains the full inversion of the verb with the subject in DI, but also certain restrictions in the form and reading of the verbal form and in the distribution of the construction.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 summarises the main arguments that have been used in the relevant literature to justify the syntactic projection of the discourse participants (speaker and addressee) and of the notion of evidentiality, both of which are essential for our understanding of a number of grammatical phenomena, among them deictic inversion. Section 3 presents an analysis of DI which formalises the role played in the derivation by a discourse feature of evidentiality and explains the main structural properties of the construction in a principled way; this analysis will also account for the differences between DI and locative inversion (At the gathering arrived some unexpected visitors), two constructions typically grouped together in grammatical descriptions. Section 4 offers some conclusions.

2. The Syntax of Speech Acts

Issues related to speech acts (i.e., how to do things with words, to use Austin’s (1962) seminal formulation) pertain to the actual use of language in communication and therefore have generally been treated as merely pragmatic. Nonetheless, a number of influential studies in the last few decades have led to what has been termed the “syntactization of discourse” (cf. Haegeman and Hill 2013), that is, the recognition that there must be a representation of the speaker and the addressee in the syntax, alongside some other structural layers that mediate between the communicative act and the meaning of the utterance.1

2.1. Speech Act Projections

As early as in 1970, Ross proposed that not only performative sentences in the sense of Austin (1962) (i.e., declarations, directives, commissives…), but also assertive declarative sentences should be derived from deep structures with a covert superordinate structure that contains a performative verb, the speaker and the addressee. Ross (1970) also observed that discursive relations are constrained by the same kind of hierarchical rules that constrain syntactic relations, a point made in Oswalt (1986) and Willett (1988) as well; similarly, Cinque (1999), in his influential work on the cartography of clausal functional projections, notes that those morphemes that express the source of information and evaluation of the sentence show striking crosslinguistic regularities in their position within a word.

Nevertheless, even if hierarchical relations in discourse significantly resemble those of the computational component, this is not enough to propose that discourse features encoding the speaker/addressee and their point of view in the proposition must be projected in the narrow syntax. One should also find robust empirical data which clearly show an interaction between the communicative act and some syntactic operation, that is, constructions in which the grammatical form crucially depends on the discursive properties of the proposition.

This seems to be the case of evidential morphemes in a number of languages, i.e., the morphemes that mark the speaker’s source for the information being reported in the utterance (see the next section); or logophoric pronouns in some African and native American languages, which refer to some individual whose point of view is being represented in the sentence (for details about logophoricity, see Sells 1987, Speas 2004, Miyagawa 2022, and references therein). Speas (2004) convincingly argues that the distribution of these grammatical elements can only be accounted for if one adopts a framework in which there are some syntactic projections that bear pragmatic features for the notions of speech act, evaluation, evidentiality and epistemicity. Along the same lines, Speas and Tenny (2003, p. 17) list a number of constructions whose description requires reference to some sentient individual, other than speaker or addressee, noting that there are systematic restrictions in all of them that would be surprising if the discourse-related properties of these constructions were purely pragmatic.

As for the pragmatic features that should be included in the syntactic representation, Speas (2004) adopts Cinque (1999)’s projections for Speech Act Mood, Evaluative Mood, Evidential Mood and Epistemological Mode, hierarchically organized above CP (or above ForceP, if one assumes the fine structure of the left periphery laid out in Rizzi 1997). She articulates these discourse categories under a Speech Act projection (SAP), and associates each of them with an implicit argument in their specifier position; these arguments represent the speaker, the evaluator, the witness and the perceiver, respectively:

| (5) | Speas (2004)’s Speech Act Phrase: |

| [SAP Speaker SA [EvalP Evaluator Eval [EvidP Witness Evid [EpisP Perceiver Epis [CP… |

As can be observed, the structure in (5) distinguishes the notion of evidentiality from the closely connected notions of evaluative mood and epistemological modality, all of which measure the information status of the sentence and share two salient properties: they involve a source of evaluation/reliability for the sentence and offer a scalar measure of the information status of that sentence (vid., Rooryck 2001). Actually, many analyses do not project them as separate categories (but see Section 2.2 below). For example, Speas and Tenny (2003) collapse this information into a Sentience Phrase, a projection whose arguments are the seat of knowledge (i.e., the sentient mind that can evaluate or comment on the truth value of the proposition) and evidence (i.e., the type of evidence available for evaluating that truth). This Sentience Phrase is dominated by the Speech Act Phrase, which includes the speaker and the hearer; in an unmarked statement, the speaker is the seat of knowledge, and in a question, the seat of knowledge is the hearer.

The analyses in Speas (2004) and Speas and Tenny (2003) opened the door to a growing body of research devoted to the structure of speech acts (Sigurðsson 2004; Zanuttini 2008; Coniglio and Zegrean 2012; Miyagawa 2012, 2017, 2022; Woods 2016; Wiltschko and Heim 2016; Portner et al. 2019; Wiltschko 2021; Krifka 2001, 2015, 2023). For example, in his influential works, Krifka holds that a speech act obtains when a proposition joins to three structurally and functionally distinct layers that codify its illocutionary force: a Judgement Phrase, which represents subjective epistemic and evidential attitudes; a Commitment Phrase, which represents the social commitment related to assertion; and an Act Phrase, which represents the relation to the common ground of the conversation and distinguishes assertions from questions. The participants in the speech act are not explicitly represented in Krifka’s model (see Krifka 2023 and references therein).2

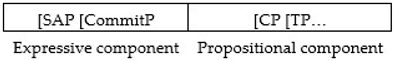

Recently, Miyagawa (2022) has returned to the idea that the speaker and the addressee should be represented in the syntactic structure and proposes a top layer, modelled on the Speech Act Phrase in Speas and Tenny (2003), with a shell-projection where SAP introduces the Speaker and saP the Addressee.3 Miyagawa (2022) also claims that the syntactic structure of a sentence is essentially partitioned into an expressive component above CP, which is about the performative act and does not contribute to the truth-value of the utterance; and a propositional component, reserved for elements that form the proposition and concern truth conditions. He integrates Krifka’s JudgeP in the propositional component (i.e., in the C-system), arguing that some linguistic elements that belong to this JudgeP contribute to the truth-value of the proposition (for example, certain modals and adverbs), and just leaves SAP and CommitP as the syntactic bases for the speech act:

| (6) | Miyagawa’s SAP: |

|

In what follows, I will assume Miyagawa’s analysis of speech acts in terms of an expressive component and a propositional component, but I will single out evidentiality as an independent category (EvidP) in the expressive component, in the spirit of Cinque (1999) and Speas (2004).4 To simplify the representations, I only project in the expressive component the categories SAP and EvidP, both essential for the analysis of DI; I therefore omit CommitP, which in this construction would have a head marking that the speaker makes a public commitment to the proposition. The relevant (simplified) structure for speech acts that I adopt here will then be as in (7):

| (7) | [SAP Speaker SA [saP Addressee sa [EvidP Evidence Ev [CP [TP… |

As I will show, the structure in (7) serves to offer a principled account of a construction such as DI, where the form of the sentence is clearly determined by its communicative function. Given the relevance of the notion of evidentiality for the proposal, the next section further discusses its status as an illocutionary functional category above CP.

2.2. The Syntactic Projection of Evidentiality

According to Jacobsen (1986), the term evidentiality was introduced into linguistics in a posthumously published grammar of Kwakiutl compiled by Franz Boas in 1947 (Boas 1947), and it was brought into common usage by Jakobson (1957). Since then, the topic has been dealt with from a wide variety of perspectives, ranging from typological studies to cognitive linguistics, grammatical description, and pragmatics.

Evidentiality refers to the grammatical expression of the information source for the content of the proposition and, as such, it serves to put that proposition in perspective. As was mentioned above, the relationship between evidentiality (which marks the source of the information), and epistemic modality (which marks the degree of reliability of that information) is not always easy to demarcate; for this reason, evidentiality has sometimes been treated as a subcategory of epistemic modality, under the view that the degree of commitment to the information depends on the information source, since this will be more reliable if the evidence is direct than if it is indirect; see, among others, Chafe and Nichols (1986), Palmer (1986) and Izvorski (1997). Krifka (2023), for example, encodes both, epistemic and evidential attitudes, in the single category Judgement Phrase; unlike Cinque (1999), Krifka does not make a structural distinction between evidential (reportedly, allegedly…), and epistemic adverbials (probably, possibly…) either, and projects the two of them as modifiers of JudgeP —one expressing the source of the judgement and the other the strength.

Other approaches treat the notions of evidentiality and epistemic modality as distinct but closely related. For example, Boye (2012, pp. 2–3) views evidentiality and epistemic modality as two subcategories of an epistemic domain: evidentiality will provide epistemic justification for the truth of the proposition (i.e., source of information, evidence or justification), whereas epistemic modality will provide epistemic support for it (i.e., degree of certainty and degree of commitment). Likewise, González et al. (2017) describe how certain lexical and grammatical resources can have both evidential and epistemic uses.

Finally, there are analyses that separate the evidential marking of the source of information from the speaker’s degree of confidence about the truth of the propositional content, on the basis of the differences that exist between the two. For example, de Haan (1999, 2005) argues that evidentials and epistemic modals differ in their lexical origins, and they also differ semantically: epistemic modality evaluates the evidence, whereas evidentiality asserts that evidence; moreover, fully-grammaticalized evidentials cannot occur within the scope of negation, unlike epistemic modal elements. Aikhenvald (2004, 2015) also points out that, even though evidentials can have epistemic extensions (relating to the degree of the speaker’s certainty concerning the statement), this does not need to be always the case, which for her means that evidentiality can be considered a category in its own right and not a subcategory of a specific type of modality (cf. Aikhenvald 2004; Nuyts 2005, among others). And Faller (2002, 2006) shows that, in languages such as Quechua, evidentiality and epistemic modality are expressed by clearly distinct sets of linguistic markers, which supports the development of a theory for each notion independently; she admits, though, that this does not preclude the possibility that specific linguistic markers may combine both.

To try and offer a conclusive answer to how evidentiality must be conceived in relation to epistemicity is well beyond the aim of this paper, but there seems to be sufficient ground to hold that they can be projected separately, and this is the turn that I will take here. It is then necessary to see whether the type of semantics involved in evidentials is illocutionary or propositional, since this is crucial to determine whether EvidP should be projected in the expressive component or in the propositional component (put differently, outside or inside the CP layer). It should be noted in this connection that even in those approaches that relate evidentiality to epistemicity, a distinction is customarily drawn between illocutionary evidentiality and epistemic evidentiality (see, among others, Izvorski 1997; Faller 2002, 2006; Matthewson et al. 2007; Murray 2010, 2021 and Demonte and Fernández-Soriano 2022). Assuming this divide, illocutionary evidentials are treated as functions from speech acts to speech acts, since they may modify the sincerity conditions of the act they apply to, but do not add to the propositional content of a sentence; thus, their contribution is not directly challengeable or up for negotiation (cf. Faller 2002, p. 231); on the contrary, epistemic evidentials may contribute to the propositional content and can be treated as epistemic modals with an evidential presupposition.5 Illocutionary evidentials will then contribute to the illocutionary or speech act content, while epistemic evidentials contribute to the propositional content. This distinction, particularly relevant in the case of indirect evidentials, has been tested on a set of diagnostics which basically check if embedding is possible, whether the evidential contribution can be challenged or not, what the relevant scope of evidentials is with respect to tense and modals, and how evidentials interact with questions (see Murray 2010). As will be shown at length below, DI—which involves direct evidentiality—clearly patterns with illocutionary evidentials under these tests: embedding is impossible, the content of the evidential operator cannot be challenged, the evidential cannot be in the scope of tense or modality, and there is no interaction with questions.

Therefore, the category EvidP in (7) stands for illocutionary evidentiality, and I assume that it contains features relevant for the speech act, not for the truth-conditional meaning of the sentence (i.e., it belongs to the expressive component). With regard to the particular features that head the projection, obviously only a short number out of the potentially infinite set of sources of evidence are grammaticized in evidential paradigms (cf., Speas 2004, p. 257). The main distinction here is between direct (i.e., attested) and indirect (i.e., inferred, or reportative) evidence (see Willett 1988, p. 57); Aikhenvald (2015, p. 240) reports the following as the recurrent meanings found in the evidential systems of human languages:

| (8) | (I) | Visual: evidence acquired through seeing; |

| (II) | Sensory: evidence through hearing, typically extended to smell and taste, and sometimes also touch; | |

| (III) | Inference: visible or tangible evidence, or visible results; | |

| (IV) | Assumption: based on reasoning and conjecture (and not on visible results); | |

| (V) | Reported: reported information with no reference to who it was reported by; | |

| (VI) | Quotative: reported information with an overt reference to the quoted source. |

One could then assume that the head of EvidP projects a [direct] or [indirect] discourse feature, together with the following specifications:

| (9) | Evid |

| [Direct] → {[visual] [sensory]} | |

| [Indirect] → {[inference] [assumption] [reported] [quotative]} |

It is estimated that around one quarter of the world’s languages have an evidential system (Aikhenvald 2004, p. 30). In these languages, evidential meanings are grammatically realized as autonomous particles or as (lexical or covert) morphemes fused with some other syntactically projected feature, normally tense or aspect (cf., Palmer 1986; Willett 1988; Aikhenvald 2015).6 An example of a language with autonomous evidentiality is Nheêngatú or Língua Geral, a Tupí-Guaraní lingua franca of north-west Amazonia. In this language, if the speakers want to assert something for which they just have indirect reported evidence, they use the autonomous evidential marker paá:7

| (10) | u-sú | u-piniatika | paá |

| 3sg-go | 3sg-fish | rep | |

| ‘He went fishing (they say/I was told)’. | |||

As for morphological evidentiality, we find examples in many Amerindian languages, as is the case of Jarawara, an Arawá language from Brazil, which has a direct (firsthand) and an indirect (non-firsthand) information source whose expression is fused with tense. For example, if a man is woken up by a dog (and has seen and/or heard it), he would use the direct sensory evidential morpheme -are fused with the immediate past:

| (11) | owa | na-tafi-are-ka |

| 1 sg.o | caus-wake-immpst.eyewit.m-decl.m | |

| ‘It did wake me (I saw it or heard it)’. | ||

English, as most Indo-European languages, lacks evidential markers of this sort and generally expresses evidentiality lexically, through adverbs (reportedly, allegedly…), complex prepositions (according to, as claimed by…) or complex sentences headed by perception verbs (I hear, I can see…), perception semi-copulas (looks like, sound…) or verbs of speaking (be said to, they say…); see Mélac (2022, p. 234). To these evidential strategies, I would like to add a syntactic construction which, to my knowledge, has not been explicitly approached this way in the relevant literature: deictic inversion. As I will show below, deictic inversion in English has some defining properties that find a natural explanation in a model which represents the syntax of speech acts and includes (a) the participants in the communicative exchange and (b) an evidential feature that encodes the speaker’s qualification of the proposition in terms of the type of evidence available for evaluating its truth. In the next section, I turn to this task.

3. A Formal Analysis of Deictic Inversion in English

English has an unmarked subject–verb order in declarative sentences, with the subject placed in front of the verb for formal reasons (i.e., it is an agreement-prominent language in the sense of Jiménez-Fernández and Miyagawa 2014). In a number of constructions, though, this basic word order is altered, and the subject occurs in a post-verbal position (following the lexical verb) while some other constituent is fronted. This so-called full inversion of the subject obtains for reasons which basically have to do with information packaging, the general condition being that the postponed subject, which becomes the informational focus, is less familiar informationally than the fronted constituent (see Birner 1996 and references therein); (12)–(14) are examples of constructions which involve full inversion in English:8

| (12) | ‘Leave me alone!’ shouts Harry. (quotative inversion) |

| (13) | In walked the cat. (directional inversion) |

| (14) | Behind him came Eton Lad, who fluttered. (locative inversion) |

Full inversion for discursive reasons is also found in deictic inversion (DI) structures, such as (1)–(4) repeated here as (15)–(18), which are used by the speaker to bring the addressee’s attention to an entity related to a proximal or distal location:

| (15) | Here comes the bus. |

| (16) | Here comes Max with his new girlfriend. |

| (17) | There goes Mary. |

| (18) | There goes a beautiful car. |

DI can be headed by the unaccusative verbs come and go, as in (15)–(18), or by copula be:9

| (19) | There is Harry with his red hat on. |

In this paper, I focus on the cases where DI is headed by a predicative verb, as in (15)–(18) above (i.e., the so-called perceptual deictic (sub)construction in Lakoff 1987, p. 482), and will only refer to the general construction with be when it bears on aspects which are relevant for the description.

Superficially, DI has much in common with standard locative inversion (LI). In both cases, the sentence is conceived as a non-predicative assertion of a state of affairs where the grammatical subject is a participant involved in that event (not the entity the proposition is about) and receives the informational focus. And both, DI and LI, have a locative constituent in initial position and are headed by a copula or an unaccusative verb (i.e., a verb that lacks an external argument and is informationally light); as examples (14) and (15) show, unaccusatives come and go may head both constructions.

Despite these similarities, DI cannot just be approached as a subtype of locative inversion since it has a discursive status which is different from that of LI. If one assumes that pragmatic information is syntactically encoded, the derivation of the two constructions is then predicted to be different as well, something which, in turn, will explain their structural differences. To show this, I will first discuss the derivation of LI to then compare it with DI and offer an analysis of the latter which shows the crucial role that a discursive feature of evidentiality has in its final form and distribution.

3.1. DI As an Evidential Strategy in a Non-Evidential Language

LI is a stylistic mechanism which has a presentational function. Structurally, it places a locative constituent in initial position to then (re)introduce the subject in the part of the scene that the fronted locative refers to (see, among others, Bresnan 1994; Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995; Birner 1996; Dorgeloh 1997 and references therein); therefore, any constituent which serves to locate the predicate may be fronted for this purpose. As for the verb, as mentioned above, the only condition is that it is not agentive and does not contribute new information to the discourse (i.e., it must be informationally light). The construction can thus be headed by copula be (20), unaccusative verbs of inherently directed motion, appearance and existence (21)–(23), and also unergative verbs that have been pragmatically emptied of their agentive meaning, that is, “unaccusativized” in the sense of Torrego (1989), as in (24):10

| (20) | In the vase are some flowers. |

| (21) | At the gathering arrived some unexpected visitors. |

| (22) | On the stage appeared a hideous creature. |

| (23) | Near his house lies a buried treasure chest. |

| (24) | Among the guests was sitting my friend Rose. |

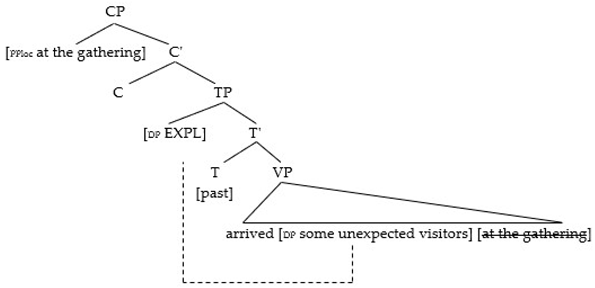

The (simplified) derivation of a LI structure such as (22) will be as follows (see, among others, Postal 1977, 2004; Hoekstra and Mulder 1990; Chomsky 2008; Bruening 2010; Ojea 2019, 2020):11

| (25) | |

|

As (25) shows, in the derivation of LI a locative phrase is fronted into CP, and the rest of the constituents remain in their underlying position. This is because T values its formal features on V via agreement—as is unmarkedly the case in English when the verb is lexical—and therefore, the lexical verb does not need to leave the VP domain. As for the subject (some unexpected visitors), it is E-merged VP-internally (i.e., it is an internal argument, since the verb is unaccusative) and remains there because the structural subject position Spec-TP is occupied by a covert expletive; this covert expletive receives empirical justification on the grounds of the existence of sentences where it is overtly realized:12

| (26) | On the stage, there appeared a hideous creature. |

| (27) | Near his house, there lies a buried treasure chest. |

| (28) | At the gathering, there arrived some unexpected visitors. |

The covert expletive hence satisfies the formal EPP requirement of T. As is well known, though, the expletive only has a partial set of phi-features (specifically, a person feature), and therefore, T must probe the DP subject some unexpected visitors to value the rest of its features on it, thus inducing verb–subject agreement. As for the nominative case feature of the subject, it gets valued via coindexing with the expletive in Spec-TP, with which it forms an A-chain.

Superficially, DI may look like a sub-type of LI where the verb that heads the construction is lexically restricted (only be and unaccusatives come and go) and so is the locative constituent that is fronted (just here or there). Significantly, both the verb and the adverb have a locative deictic component which is measured with respect to the speaker: come expresses motion towards the speaker, whereas go expresses motion away from the speaker; here points at a proximal location with respect to the speaker, and there at a distal location with respect to the speaker. Moreover, in discourse, speakers use DI with a particularly complex intention which is not there in standard LI and involves coordinated acts and effects on three cognitive dimensions: speaking, visual perception and the construction of spatial mental models on the part of the addressee (cf., Webelhuth 2011, p. 91): the speaker brings the addressee’s attention to an entity (related to a proximal or distal location), which thus constitutes the informational focus of the proposition. In other words, DI is used as an evidential strategy when the speaker commits to the truth of a proposition relying on direct (visual) evidence and wants to make the addressee aware of this.

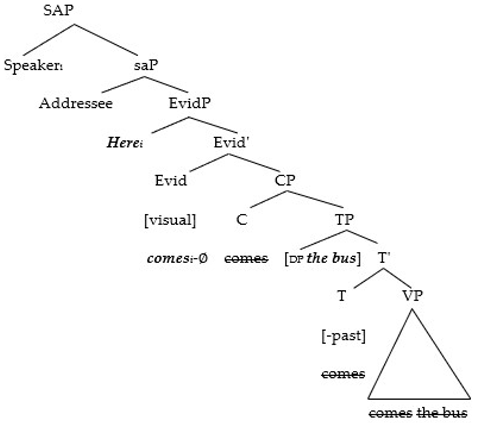

My proposal here is that it is this evidential status that determines the structural properties of the construction. To show this, I assume an analysis of speech acts along the lines discussed in Section 2, adopting the (simplified) structure in (7) (repeated here as (29)), modelled on Miyagawa (2022), but with evidentiality projected as a category in its own right in the expressive component:

| (29) | [SAP Speaker SA [saP Addressee sa [EvidP Evidence Ev [CP [TP… |

The (simplified) derivation of a sentence such as (21) (Here comes the bus) will then be as follows:

| (30) | |

|

As (30) shows, contrary to the case of LI, the derivation of DI crucially relies on the discursive categories in the expressive component, and both the verb and the locative adverbial—coindexed with the speaker—are placed in EvidP. In DI, the information source for the content of the proposition is always direct evidence on the part of the speaker, and EvidP is headed by the δ-feature [visual], encoded as a covert morpheme (one of the possibilities found in the evidential paradigm crosslinguistically); the head feature may be [sensory] instead of [visual], as in (31) and (32), when the source of the information is non-visual sensory experience (see Lakoff 1987, p. 484):

| (31) | Here comes the beep. |

| (Auditory evidence: when you hear the warning click of the alarm clock) | |

| (32) | Here comes the pain in my knee. |

| (Physical evidence: when you feel a twinge before the pain appears) |

As mentioned, the derivation of DI involves the expressive component, and the main structural differences between DI and LI have to do with the placement of the locative adverbial, the position of the subject and the eventual placement of the verb in the structure.

In DI, the deictic adverbial here/there (coindexed with the speaker) is E-merged in the evidential projection to mark the visual reference point as proximal or distal; the adverbial may therefore coexist with the expression of some other locative complement in the VP:

| (33) | Here comes a bus into the terminal. |

This contrasts with LI, where the fronted adverbial is I-merged in the CP projection and therefore leaves a copy in its underlying position, thus preventing the projection of another constituent of the same type:

| (34) | *At the gathering arrived some unexpected visitors there. |

As for the position of the subject, whereas in LI the structural subject position is occupied by an expletive, this is not the case in DI, where the presence of expletives is ruled out (compare (35), with an unstressed there (/ðə(r)/) in subject position, with (26)–(28) above):

| (35) | *Here there comes the bus. |

Therefore, the DP subject in DI structures is targeted into TP to satisfy the EPP, and it also values its own case feature there. Since the subject sits in the canonical Spec-TP position, no definiteness effect will be at play (Here comes a bus/the bus/Max) and, as expected, there will be agreement of the DP with the verb (examples taken from Kay and Michaelis 2017, p. 19):

| (36) | a. There goes John’s old tutor. |

| b. There go two boys who just turned twenty… |

If the DP subject is in Spec-TP, we would expect to find the same type of DPs here that we may find in any other assertive sentence, including pronominal DPs. These are nevertheless forbidden in the construction:

| (37) | *There comes he. |

Note, though, that this impediment to have a pronominal subject postverbally affects not only DI but all of the constructions which involve full inversion in English; compare (38)–(40) with (12)–(14):

| (38) | *‘Leave me alone!’ shouts he. |

| (39) | *In walked it. |

| (40) | *At the gathering arrived they. |

In all of these constructions, when the structure is transferred to the conceptual-intentional system, the subject follows the lexical verb and must be interpreted as the informational focus of the sentence. This suggests that the impossibility to have a postverbal pronominal subject in sentences such as (37)–(40) does not have to do with a formal restriction, but with a pragmatic constraint related to information requirements: given that the DP subject constitutes the informational focus, it must convey new—or at least less familiar—information than the other constituents (cf., Birner 1996’s Relative Familiarity Constraint). This is what rules out anaphoric pronouns, which, by definition, refer back to entities already in the common ground. If the pronoun contributed new or contrastive information (i.e., if it had a heavy stress and a focal reading) it could actually be a possible subject in DI, and this is attested by some native speakers who claim that, if the sentence in (37) were inserted in any of the dialogues below, it would be acceptable (stress indicated with capitals):13

| (41) | The only person who could save us now is Bob. |

| Oh, look! Here comes he! | |

| (42) | We really need Josh and Katie to get here, right now! |

| Oh look, there comes he, at least, though I still don’t see her anywhere. |

It is also significant that the pronominal subjects in (41) and (42) are in the nominative case, something which provides additional evidence for the placement of the subject in the Spec-TP position.14

Finally, the eventual placement of the verb in the head of EvidP has to do with the role of the verbal predicate in DI. Evidentials behave like indexicals (cf. Kaplan 1989), and direct evidentiality, in particular, is speaker-anchored. In English, there is no lexical morpheme which may mark this indexical relationship with the speaker and, therefore, the construction resorts to two unaccusative predicates, come and go, which include in their meaning a component path measured towards/away from the speaker and locate the speaker at the starting/end point of the motion event. The unaccusative predicate coindexed with the speaker is targeted into EvidP in the expressive component to value the evidential feature there, so that the sequence can be successfully transferred to the conceptual-intentional system. This means that the verb leaves the VP domain, contrary to the case of LI (see (25)), and this movement must satisfy the general considerations of simplicity and efficient design, i.e., it must take place in the most economical way under locality conditions. The implication is that the verb must move into Evid in a head-to-head fashion and thus values the formal features of T on its way to the speech act projection. Eventually, then, tense and evidentiality are fused, as is also the case in evidential systems, where evidential markers tend to appear fused with some syntactically projected grammatical feature (normally tense or aspect).

This derivation implies that T does not value its features under agreement with come and go, contrary to what is standardly the case with lexical verbs in present-day English; in other words, in DI, come and go behave as if they were auxiliary verbs. One should bear in mind, in this respect, that the overt movement of come/go in the construction is necessary for convergence with the external intentional system, that is, it is a marked operation where interface economy competes with computational economy, forcing a costly derivation (on interface economy, see Reinhart 2006). Furthermore, come and go group in DI with copula be, and they just differ in that the unaccusative predicates have a deictic locative component which is not there in the meaning of the auxiliary, and serves to mark more explicitly the spatial relationship between the speaker and the entity signalled (e.g., There is/goes Harry with his red hat on). Therefore, the fact that copula be (a real auxiliary) and come and go behave alike syntactically in DI may just be a natural consequence of the little semantic import of the latter, which makes them auxiliary-like in the construction.15 Note as well that come and go have a functional behavior in pseudo-coordinations (e.g., What has John gone and done all day?; see de Vos (2004) for details), which means that they can be semantically bleached in other constructions too.16

To summarize so far: DI can be analysed as a syntactic strategy which marks evidentiality in a language that is not evidential in the strict (morphological) sense. In it, the verb is eventually placed outside CP, in the head of EvidP in the expressive component, and there it values a discourse feature that encodes direct evidentiality—the information source for the content of the proposition is visual, or at least sensory, evidence. The deictic adverbial here or there in the specifier of that projection signals whether the visual reference point is proximate or distal to the speaker.

As I will show next, an analysis along these lines not only accounts for the discursive and formal properties of DI just mentioned but also explains the main differences between DI and LI, which, as expected, basically follow from the different illocutionary value of the two constructions.

3.2. Empirical Predictions of the Analysis

The analysis of DI in (30) explains one of the aspects which most notably distinguishes this construction from its non-inverted counterpart and from similar structures such as LI: the temporal interpretation of the verbal form. As discussed above, the evidential feature in the expressive component targets the lexical verb, which values tense on its way up. This means that the grammatical feature tense will eventually be fused with the discourse feature of evidentiality that marks that the speaker has visual or sensory evidence of the facts. Accordingly, if the verbal form is present (see all of the examples used so far), it will have the interpretation that the speaker has direct evidence for the proposition at the moment of speech. Consequently, the simple present does not have here the imperfective generic interpretation which is the unmarked reading of a “true” simple present in English (i.e., it will be a present of evidentiality). This is quite evident if we compare DI with its non-inverted counterpart:

| (43) | Here comes a bus now/* regularly. |

| (vs. A bus comes here * now/regularly.) |

A similar situation is found in the past. Even though most instances of DI are in the present tense, examples of DI where the verbal predicate has past morphology are also possible, as Kay and Michaelis (2017, p. 21) show:

| (44) | Here came the waitress. She had on a mini-skirt, high heels, see-through blouse with padded brassiere. |

| (45) | So I looked, and here came a white horse! |

| (46) | Here came the Princess, and as she passed hats were lifted. |

| (47) | There went Dr. and Mrs. Sorabjee, leaving little Amy alone at their table. |

The past in these sentences must also be understood as a past of evidentiality, since it marks that the speaker had direct evidence of a situation which was ongoing at the reference time of the narration. This reading, as in the case of the present above, contrasts with the standard reading of the simple past in English, which unmarkedly places the event as anterior to the time of the assertion; note in this respect that the sentences in (44)–(47) are not compatible with an adverbial such as yesterday, which marks anteriority:

| (48) | *Yesterday, here came the waitress… |

| (49) | *Yesterday I looked, and here came a white horse! |

| (50) | *Yesterday, here came the Princess, and as she passed hats were lifted. |

| (51) | *Yesterday, there went Dr. and Mrs. Sorabjee, leaving little Amy alone at their table. |

In DI, therefore, the verbal form indicates simultaneity with the assertion-time (be this coincident with the time of the utterance or not), a reading which is customarily expressed with progressive forms in English. Note, though, that if a progressive auxiliary were present in the Numeration, locality restrictions would prevent I-merge of the deictic predicate in Evid, since the auxiliary would be structurally closer to the probe than the main verb. This is why examples such as (52)–(55) below are not possible in English:

| (52) | *Here is coming the bus. |

| (53) | *There is going Mary. |

| (54) | *So I looked, and here was coming a white horse! |

| (55) | *There were going Dr. and Mrs. Sorabjee, leaving little Amy alone at their table. |

As expected, in LI, where the verb remains in the VP throughout the derivation (see 25), the impediment for progressive forms does not exist, something which De Wit (2016) has attested in an extensive corpus that she elicited from native speakers’ surveys ((56) and (57) are her examples (33) and (34); also see sentence (24) above):

| (56) | In that house are living strange people. |

| (57) | On top of the square block is lying another block. |

The form and reading of the verb in DI are therefore crucially conditioned by the role of the predicate as the category that eventually encodes evidentiality in the derivation.

Another interesting prediction of the analysis in (30) has to do with the syntactic distribution of deictic inversion in English, which shows restrictions that are not present in its non-inverted counterpart or in LI. Once more, these restrictions can only be properly explained in terms of the specific pragmatic value of the construction.

DI, as all constructions involving full inversion in English (including LI), is a root/main clause phenomenon (Emonds 1970, 2004), and, as such, it occurs in main clauses, direct quotations, parentheticals and coordinate clauses:

| (58) | Here comes my bus. |

| (59) | She said: “Here comes my bus”. |

| (60) | Here comes the bus, she said. |

| (61) | I really should stay, but here comes my bus. |

Nevertheless, while LI allows embedding in contexts which are root-like (“root-like indirect discourse embedding” contexts, RIDEs in Emond’s terminology), DI heavily restricts embedding even in these cases:

| (62) | It seems that on the opposite corner stood a large Victorian mansion. |

| (63) | *It seems that here comes my bus. |

This again has to do with the fact that DI (contrary to LI) codifies illocutionary evidentiality, given that, as has been repeatedly claimed, illocutionary evidentials cannot embed (see Murray 2010; Demonte and Fernández-Soriano 2014, Aikhenvald 2015, and references therein). Significantly, the only context in which DI can be embedded and may still sound natural is the complement position of a perception verb, as in (64):17

| (64) | I can see that here comes my bus. |

The subordination of DI to the verb see in (64) may be understood as the result of applying a double strategy of evidentiality (lexical and syntactic), through which the information source for the proposition is reinforced. The possibility to have DI as the complement of a lexical marker of visual evidentiality therefore provides additional support for the analysis of the construction as an evidential strategy.

It is also possible to find DI in peripheral adverbials which provide background propositions for the assertion in the main clause and are also root-like (see Haegeman 2004 for the distinction between central and peripheral adverbials in this respect); these clauses serve to structure the discourse, that is, to articulate the speech act, and are therefore compatible with an evidential strategy of this sort:

| (65) | I’d better leave, since here comes my bus. |

| (66) | I’d stay a little longer, except here comes my bus. |

It is interesting to note that Lakoff (1987, pp. 471–81), from where examples (61), (65) and (66) have been taken, aligns DI in terms of distribution with other constructions in English which convey assertions, such as negative questions (Didn’t Harry leave?), inverted exclamations (Boy! Is he ever tall!), wh-exclamations (What a fool he is!), rhetorical questions (Who on earth can stop Bernard?) and reversal tags (He is coming, isn’t he?). For him, the reason why all of these apparently unrelated constructions group together distributionally has to do with the fact that they are all speech act constructions, that is, constructions which are restricted in their use to expressing certain illocutionary forces. He claims that an adequate analysis of these constructions must necessarily pair their grammar with the illocutionary force they express, which is also the point I am making here.

In this regard, the impossibility to have DI in the interrogative or negative form also has to do with its illocutionary value as an evidential strategy. Whereas the non-inverted counterpart of the construction can be questioned (Is the bus coming here?), DI is used for the speaker to assert a proposition on the basis of some visual/sensory evidence; that is, the speaker is committed to the proposition, and this assertive value cannot be suspended. This is why the interrogative sentence in (67), though grammatical in English, cannot have an evidential reading (i.e., (67) is not a case of DI inversion, as the imperfective reading of the verb shows):

| (67) | Does the bus come here (regularly/* now)? |

Additionally, illocutionary evidentiality does not contribute to the truth conditions of the proposition, and for the same reason, it cannot be accessed by linguistic operations bearing on propositional truth, such as negation. DI, in particular, involves direct evidentiality, which implies that the evidential contribution (i.e., the fact that the speaker sees, hears, or feels something) can be neither challenged nor denied; in other words, the addressee cannot reply no or that’s not true to mean that the speaker did not see/hear/feel that (see Murray 2021). Also note that EvidP, the category which finally hosts the verb, is structurally projected in the expressive component and thus outside the scope of the negative operator: negation can therefore access (some of the elements in) the proposition, but not the source of information for the proposition itself (see de Haan 1999, 2005; Demonte and Fernández-Soriano 2014; Murray 2021 among others).

The analysis of DI as a construction which marks evidentiality through syntactic means therefore formalizes its illocutionary force in discourse and accounts for its structural restrictions in a principled way. Obviously, this analysis should be further tested to fully confirm its empirical validity. Two questions immediately arise in this regard: is DI a syntactic strategy for evidentiality cross-linguistically, and (b) is DI the only construction where evidentiality is signalled syntactically? I offer a tentative answer for these questions here, leaving full treatment of the corresponding issues for future research.

With regard to the first (is DI a syntactic strategy for evidentiality cross-linguistically?), I expect DI to be possible in other non-evidential languages and have the same (or similar) restrictions that the construction manifests in English. At first sight, this seems to be the case for Spanish and probably other Indo-European languages as well.

Spanish word order is not as rigid as that of English and, as is well-known, the subject can be preverbal or postverbal in unmarked declarative sentences.18 Postverbal subjects are also possible for discourse-dependent reasons, and the options here are also broader than in English. In the case of locative inversion, for example, not only unaccusatives (68) but also (in)transitive verbs (69) may undergo full inversion (see Ojea 2019 for details):

| (68) | En | la | puerta | apareció | una | extraña | criatura. |

| in | the | doorway | appear-3sing.past | a | strange | creature | |

| ‘In the doorway appeared a strange creature’. | |||||||

| (69) | En | este | garaje | guarda | Juan | su | bicicleta. |

| in | this | garage | keep-3sing.pres | John | his | bicycle | |

| ‘John keeps his bicycle in this garage’. | |||||||

Spanish also displays a VS ordering in DI with venir and ir, a construction that has the same evidential reading as in English, that is, one in which the speaker brings the addressee’s attention to an entity related to a proximal or distal location:

| (70) | Aquí | viene | el | autobús. |

| here | come-3sing.pres | the | bus | |

| ‘Here comes the bus’. | ||||

As in the case of English, the progressive forms that express ongoing situations in Spanish cannot be used in DI; as a matter of fact, verbal forms in DI cannot be analytic, even though full inversion with analytic forms is possible in other stylistic inversions, such as LI. Compare, in this respect, the DI examples (71) with standard cases of LI (72):

| (71) | a. | *Aquí | está viniendo | el | autobús. |

| here | be-3sing.pres come-progr | the | bus | ||

| ‘* Here is coming the bus’. | |||||

| b. | *Aquí | ha venido | el | autobús | |

| here | have-3sing.pres come-perf | the | bus | ||

| ‘* Here has come the bus’. | |||||

| (72) | a. | En | mi | jardín | ya | están floreciendo | los | rosales |

| in | my | garden | already | be-3sing.pl flourish-progr | the | rosebushes | ||

| ‘Rosebushes are flourishing in my garden’. | ||||||||

| b. | En | mi | jardín | ya | han florecido | los | rosales | |

| in | my | garden | already | have-3sing.pl flourish-perf | the | rosebushes | ||

| ‘Rosebushes have already flourished in my garden’. | ||||||||

Further, the tensed verbal form in Spanish DI must be understood as present/past of evidentiality with a reading of simultaneity with the assertion time, something we also observed for English. Therefore, the present form in the construction is not compatible with adverbs which express habitualness instead of simultaneity, such as habitualmente (habitually) (73); as expected, adverbs like this can freely modify LI structures (74):

| (73) | Aquí | viene | el | autobús | ahora | /* habitualmente. |

| here | come-3sing.pres | the | bus | now | /usually | |

| ‘Here comes the bus now/* usually’. | ||||||

| (74) | En | este | terreno | habitualmente | florecen | rosales |

| in | this | ground | usually | flourish-3pl.pres | rosebushes | |

| ‘Rosebushes usually flourish in this ground’. | ||||||

Similarly, past DI excludes adverbials which place the event as anterior to the time of the assertion, as is the case of ayer (yesterday) in (75):

| (75) | *Ayer | ahí | venía | el | bus. |

| yesterday | there | come-3sing.past.imperf | the | bus | |

| ‘*Yesterday there came the bus’. | |||||

Note that only the imperfective past is possible in Spanish DI (as in (75)); the reason for this restriction is that Spanish perfective past focuses the limits of the event, and this makes it incompatible with the expression of simultaneity required by the evidential reading of the construction:

| (76) | Se fijó | y, | en | efecto, | ahí | venía/* vino | el | bus. |

| look-3sing.past.perf | and, | in | effect, | there | come-3sing.past.imperf/*come-3sing.past.perf | the | bus | |

| ‘She looked closely, and, in effect, there came the bus’. | ||||||||

And again, as expected, none of these restrictions are there in the structurally similar LI (i.e., nothing impedes past adverbials or the perfective past):

| (77) | En | este | terreno | floreció | el | año | pasado | un | rosal |

| in | this | ground | flourish-3sing.past.perfect | the | year | past | a | rosebush | |

| ‘Last year a rosebush flourished in this ground’. | |||||||||

These facts therefore suggest that the derivation of DI in Spanish may also involve a discourse feature that drives the derivation and forces certain options over others. Hopefully, further investigation on DI in Spanish and other non-evidential languages may provide compelling evidence in favour of the status of the construction as a form of evidential marking.

As an anonymous reviewer has observed, it would also be interesting to explore how English DI is translated into proper evidential languages and check if the translation includes an evidential marker of some sort; if this were the case, the evidential status of DI would clearly be substantiated. Note, though, that the morphological marking of evidentiality is heavily language-dependent (i.e., there is not a systematic one-to-one correspondence between possible sources of evidence and morphology in evidential languages) and, as Aikhenvald (2015) mentions, evidential languages show fewer evidential distinctions in non-past tenses than in past tenses. Therefore, it could be the case that none of these evidential languages has a specific morpheme to signal direct visual evidence in the present, but this will not necessarily constitute a counterargument to the existence of a syntactic strategy for it in other languages.

As for the second question (is DI the only construction where evidentiality is signalled syntactically?), one would expect evidentiality to play an active role in the syntax of some other constructions as well. Speas (2004, p. 258), following observations from Oswalt (1986) and Willett (1988), points out that the categories of evidentiality lie in a hierarchy which corresponds to the degree to which the evidence directly involves the speaker’s own experience:

| (78) | Evidentiality hierarchy: |

| personal experience >> direct (e.g., sensory) evidence>> indirect evidence >> hearsay. |

It is therefore important to explore not only if other constructions mark evidentiality through syntactic means in English, but also if syntactic evidentiality is subject to the same hierarchy found in the morphological system of evidential languages. As noted by an anonymous reviewer, if DI marks the kind of evidence which is at the top of the hierarchy (i.e., personal experience of the situation and direct evidence), the prediction will be that other constructions may mark the lower sources of evidence as well—i.e., indirect evidence.

Again, this seems to be the case. For example, Jiménez-Fernández and Tubino-Blanco (2023) offer a syntactic analysis of inferential questions in Spanish (whose main claims also apply to English: What are you, on a diet?) where indirect evidentiality plays an important role in the interpretation and form of these sentences. And, probably, word order in some of the constructions which Lakoff (1987, pp. 471–81) labels speech act constructions, such as negative questions (Isn’t it a beautiful day?) or reversal tags (He is coming, isn’t he?), could also be explained in terms of syntactic expression of indirect evidentiality.

4. Concluding Remarks

As Demonte and Fernández-Soriano (2014, p. 40) claim, investigation into the syntax–pragmatics interface must try to clarify the relevant elements which are explicitly elicited by the interaction between these components, and also the level of analysis which is most appropriate to characterize such interactions.

Relating to the first issue, the expression of the information source for the proposition through syntactic means constitutes a clear case of syntax–pragmatics interaction. One should note, though, that there exist different views on how to define evidentiality within the domain of grammar. For some scholars—mainly typologists—the notion of evidentiality should be restricted to the so-called evidential languages and, accordingly, to morphological marking; for others, evidentiality can be considered a more general functional category whose scope also includes lexical phenomena and can thus be extended to languages traditionally considered non-evidential. Squartini (2007), who offers an interesting account of these conflicting views, suggests that it is plausible to consider that morphological marking and lexical strategies might in fact be the opposite endpoints of a continuum which could admit intermediate stages, that is, linguistic forms less paradigmatic than evidential morphemes but more morphosyntactically constrained than, for example, evidential adverbs.

Adopting this intermediate view, languages which are not evidential in the strict sense may nonetheless employ syntactic and phonological means for the linguistic expression of evidentiality, and, as a result, the syntactic or phonological properties of some constructions in those languages may follow from the evidential reading that they have. I have suggested here that this is the case for deictic inversion, a construction whose word order and distribution can be explained in terms of a syntactic operation that places the verbal predicate high in the structure to signal direct evidentiality.

DI will then constitute a strategy of evidentiality in a language that does not codify evidentiality in the morphological system (i.e., which is not evidential in the strict sense). As I have shown, in this it differs from LI, which does not express the source of the information; table (79) summarizes the main structural differences between the two constructions that follow from this fact:

| (79) | DI | LI | |

| Type of verb | Come/Go Copula be | Unaccusative verbs of inherently directed motion, appearance or existence. Copula be | |

| Initial locative constituent | Here/There | Any locative phrase | |

| Expletive subject there |  Ex. (35) Ex. (35) |  Ex. (26)–(28) Ex. (26)–(28) | |

| Analytic verbal forms |  Ex. (52)–(55) Ex. (52)–(55) |  Ex. (24), (56), (57) Ex. (24), (56), (57) | |

| RIDE |  Ex. (63) Ex. (63) |  Ex. (62) Ex. (62) |

The analysis of DI as an evidential strategy also accounts for its restricted distribution and for the otherwise unexpected difference between DI and its non-inverted counterpart in the reading of the present/past tense (cf., 43 and 48–51).

As regards the second issue (i.e., the level of analysis which is most appropriate to characterize syntax–pragmatics interactions), I have shown that the morphosyntactic expression of evidentiality in DI involves what Miyagawa (2022) terms the expressive component, that is, a structural layer “in the treetops” (i.e., above CP). A construction such as DI, whose grammar reflects its illocutionary force, therefore provides indirect evidence in favour of this upper level of structure which mediates between the act that the speaker engages in and the meaning of the utterance, encoding information about the speaker’s commitment to the proposition and the information source for its content.

If this view is on the right track, the approach taken here to deictic inversion will hopefully pave the way for further research into the role of evidentiality and other discourse features in the syntactic derivation. Eventually, in-depth studies about the organization and structure of the expressive domain will serve to furnish principled explanations of a number of phenomena traditionally considered pragmatic and, consequently, to formalize the way in which central programmatic notions such as competence and performance interact.

Funding

This research has been funded by Spain’s Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MICINN), grant number PID2022-137233NB-I00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are based on the author’s own judgements or taken from publications cited and properly referenced.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the anonymous reviewers of Language for their very insightful remarks and suggestions, and to Julio Villa-García for fruitful discussion on the topic. I would also like to express my gratitude to the conference abstract reviewers and audience at the IV Encontro de Gramática Gerativa (Bahia, Brazil) and the 46th AEDEAN Conference (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain). Needless to say, all remaining errors are exclusively my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The syntactization of discourse is not unanimously accepted in the generative framework. See, for example, Fanselow (2008) and references therein for a defence of the hypothesis that syntax must be blind to categories of information structure. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Though eventually published in 2023, this work by Krifka has circulated extensively in its pre-print form since 2020. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | SAP in Miyagawa’s analysis actually stands for Speaker-Addressee Phrase, but it is equivalent in the relevant sense to the Speech Act Phrase in Speas and Tenny (2003). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Note, in this respect, that even if evidentiality, evaluative mood and epistemological modality are pragmatically connected, the existence of distinct heads for each of these notions has been shown to be necessary for certain grammatical accounts (for example, to provide a classification of logophoric predicates in terms of the projection they select; see Speas 2004). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | For Murray (2010, p. 47), illocutionary evidentials are similar to certain English parentheticals (like …, I hear; …, I find; …, they say; …, it’s said; …, I take it; …, it seems), while epistemic evidentials behave more like epistemic modals (such as must, definitely, reportedly, apparently…). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | As Willett (1988, p. 51) points out, very few languages actually encode evidentiality as a separate grammatical category. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | The abbreviations in examples (10) and (11), taken from Aikhenvald (2015, pp. 244–45), stand for sg (singular), rep (reported), o (object), caus (causative), immpst (immediate past) eyewit (eyewitness), m (masculine), decl (declarative). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Examples taken from De Wit (2016, p. 110), Lakoff (1987, p. 504) and Kim (2003, p. 155). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | As Lakoff (1987, pp. 469–70) points out, DI with copula be is very similar in its structure to the existential-there construction (e.g., There is a man with a red hat on in the room), to the point that it is even possible to find cases where both only differ in stress (stress indicated with capitals):

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Examples taken from Ojea (2020). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | For an alternative analysis where the locative phrase sits in TP at some point of the derivation, preventing the DP subject from moving there, see, among others, (den Dikken and Naess 1993; Bresnan 1994 and Rizzi and Shlonsky 2006). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Presentational sentences with a lexical or a covert expletive are not totally equivalent in structural terms, though: when the expletive is lexical (as in 26–28), it imposes a definiteness effect on its associate, which is not there if the expletive is covert. Therefore, a sentence such as (i) is grammatical in English, whereas (ii), its counterpart with the lexical expletive there, is not:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Examples taken from an internet log: https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/246050/here-he-comes-here-comes-he-the-order-of-pronoun-and-verb-in-inversion (accessed on 10 November 2023). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | One may object that in DI inversion with copula be, pronominal subjects cannot appear in the nominative:

This is not construction-specific, though, but a general constraint on predicate nominals with copula be (It is me/* I; The murderer is her/* she); according to Newson (2018), this peculiarity has to do with the fact that the case system only sees arguments, and thus, predicate nominals of this sort get default case, which in English has the same form as the accusative. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | This is not totally exceptional in English, and come and go pattern here with other cases of semantically light main verbs that can behave as auxiliaries and be subject to overt V to T (and T to C) movement, such as possessive have in some dialects (e.g., Have you enough money?). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | I owe this observation to an anonymous reviewer of the paper. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | I thank an anonymous reviewer, a native speaker of British English, for this observation. The same reviewer notes that a sentence such as (i) below could also be acceptable:

Note, though, that the subordinate clause in (i) does not point at a real location shared by the speaker and the hearer (i.e., does not mark visual evidence), and therefore, its derivation could be different from that of standard perceptual deictic inversion. I leave the study of constructions of this type for future research. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | See Fernández Ramírez (1986, p. 430 and ff.) for a very exhaustive description of the position of the subject in Spanish. As discussed there and in Ojea (2017) (and references therein), SV is not always the canonical position of the subject. As a matter of fact, VS is the default option when the subject is not the external argument of the verb; for example: (a) with psychological verbs such as gustar ‘like’, preocupar ‘worry’, or molestar ‘bother’, whose external argument is a dative experiencer (i); (b) with verbs such as faltar ‘lack’, sobrar ‘excede’, or ocurrir ‘occur’, whose external argument is a locative phrase which signals the place where the state or event originates (ii); and (c) with unaccusative verbs, the postverbal position being preferred in this case when the subject has an indefinite, set referring or existential reading (see Ojea 2017 for a description of the syntactic and semantic reasons which favour postverbal subjects of this type) (iii). The subject must also appear after the verb when there are no postverbal modifiers, probably for prosodic reasons (e.g., the Weight to Prominence constraint; see Gutierrez-Bravo 2005) (iv):

As expected, the subject can also invert with the verb for reasons which have to do with information structure, as is the case of locative inversion or deictic inversion. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2015. Evidentials: Their links with other grammatical categories. Linguistic Typology 19: 239–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, John Langshaw. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Birner, Betty J. 1996. The Discourse Function of Inversion in English. New York: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, Franz. 1947. Kwakiutl Grammar, with a Glossary of the Suffixes. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 37: 201–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, Kasper. 2012. Epistemic Meaning. A Crosslinguistic and Functional-Cognitive Study. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnan, Joan. 1994. Locative Inversion and the Architecture of Universal Grammar. Language 70: 72–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, Benjamin. 2010. Language-Particular Syntactic Rules and Constraints: English Locative Inversion and Do-support. Language 86: 43–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, Wallace, and Johanna Nichols, eds. 1986. Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Norwood: Ablex. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On Phases. In Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory: Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Edited by Robert Robert Freidin, Carlos Peregrín-Otero and María Luisa Zubizarreta. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 133–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coniglio, Marco, and Julia Zegrean. 2012. Splitting up force: Evidence from discourse particles. In Main Clause Phenomena. Edited by Lobke Aelbrecht, Liliane Haegeman and Rachel Nye. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 229–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, Ferdinand. 1999. Evidentiality and Epistemic Modality: Setting the Boundaries. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 18: 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- de Haan, Ferdinand. 2005. Encoding Speaker Perspective: Evidentials. In Linguistic Diversity and Language Theories. Edited by Zygmunt Frajzyngier, Adam Hodges and David S. Rood. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 379–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, Mark. 2004. Pseudo coordination is not subordination. In Linguistics in the Netherlands. Edited by Leonie Cornips and Jenny Doetjes. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, Astrid. 2016. The relation between aspect and inversion in English. English Language and Linguistics 20: 107–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demonte, Violeta, and Olga Fernández-Soriano. 2014. Evidentiality and Illocutionary force: Spanish Matrix que at the Syntax-Pragmatics Interface. In Left Sentence Peripheries in Spanish. Diachronic, Variationist and Comparative Perspectives. Edited by Andreas Dafter and Álvaro S. Octavio de Toledo y Huerta. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 217–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demonte, Violeta, and Olga Fernández-Soriano. 2022. A Multidimensional Analysis of the Spanish Reportative Epistemic Evidential dizque. Lingua 266: 103–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Dikken, Marcel, and Åshild Naess. 1993. Case dependencies: The case of predicate inversion. Linguistic Review 10: 303–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorgeloh, Heidrun. 1997. Inversion in Modern English. Form and Function. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Emonds, Joseph. 1970. Root and Structure-Preserving Transformations. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Emonds, Joseph. 2004. Unspecified Categories as the Key to Root Constructions. In Peripheries: Syntactic Edges and Their Effects. Edited by David Adger and Cécile De Cat y George Tsoulas. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 75–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, Martina. 2002. Semantics and Pragmatics of Evidentials in Cuzco Quechua. Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Faller, Martina. 2006. Evidentiality and Epistemic Modality at the Semantics/Pragmatics Interface. Paper presented at the Workshop on Philosophy and Linguistics, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, November 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow, Gisbert. 2008. In need of mediation: The relation between syntax and information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55: 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Ramírez, Salvador. 1986. Gramática española. Vol. 4: El verbo y la oración. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- González, Montserrat, Paolo Roseano, Joan Borràs-Comes, and Pilar Prieto. 2017. Epistemic and Evidential Marking in Discourse: Effects of register and debatability. Lingua 186–87: 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Georgia. 1982. Colloquial and Literary Uses of Inversion. In Spoken and Written Language: Exploring Orality and Literacy. Edited by Deborah Tannen. Norwood: Ablex, pp. 119–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Bravo, Rodrigo. 2005. Subject Inversion in Spanish Relative Clauses. A Case of Prosody-induced word Order Variation without Narrow Focus. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2003. Edited by Twan Geerts and Ivo van Ginneken y Haike Jacobs. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegeman, Liliane. 2004. The Syntax of Adverbial Clauses and its Consequences for Topicalisation. Antwerp Papers in Linguistics 107: 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Haegeman, Liliane. 2014. West Flemish Verb-Based Discourse Markers and the Articulation of the Speech Act layer. Studia Linguistica 68: 116–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegeman, Liliane, and Virginia Hill. 2013. The Syntactization of Discourse. In Syntax and its Limits. Edited by Raffaella Folli, Christina Sevdali and Robert Truswell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 370–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, Teun, and René Mulder. 1990. Unergatives as Copular Verbs; Locational and Existential Predication. Linguistic Review 7: 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izvorski, Roumyana. 1997. The Present Perfect as an Epistemic Modal. In Proceedings of SALT VIII. Edited by Aaron Lawson. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 222–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, William H., Jr. 1986. The Heterogeneity of Evidentials in Makah. In Evidentiality. The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Edited by Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols. Norwood: Ablex, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1957. Shifters, Verbal Categories and the Russian Verb. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Fernández, Ángel L., and Mercedes Tubino-Blanco. 2023. Inferential Interrogatives with qué in Spanish. Languages 8: 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Fernández, Ángel L., and Shigeru Miyagawa. 2014. A feature-inheritance approach to root phenomena and parametric variation. Lingua 145: 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, David. 1989. Demonstratives. An Essay on the Semantics, Logic, Metaphysics and Epistemology of Demonstratives and other Indexicals. In Themes from Kaplan. Edited by Joseph Almog, John Perry and Howard Wettstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 481–563. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, Paul, and Laura Michaelis. 2017. Partial inversion in English. Paper presented at the 24th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Lexington, KY, USA, July 7–9; pp. 212–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jong-Bok. 2003. English Locative Inversion: A Constraint-Based Approach. Korean Journal of Linguistics 28: 207–35. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, Manfred. 2001. Quantifying into Question Acts. Natural Language Semantics 9: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifka, Manfred. 2015. Bias in Commitment Space Semantics: Declarative Questions, Negated Questions, and Question Tags. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 25. Phoenix: LSA Open Journal Systems, pp. 328–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifka, Manfred. 2023. Layers of Assertive Clauses: Propositions, Judgements, Commitments, Acts. In Propositionale Argumente Im Sprachvergleich: Theorie und Empirie/Propositional Arguments in Cross-Linguistic Research: Theoretical and Empirical Issues. Edited by Jutta M. Hartmann and Angelika Wöllstein. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 116–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. What Categories Reveal About the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Beth, and Malka Rappaport Hovav. 1995. Unaccusativity at the Syntax-Lexical Semantics Interface. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthewson, Lisa, Henry Davis, and Hotze Rullmann. 2007. Evidentials as Epistemic Modals: Evidence from St’át’imcets. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 7: 201–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mélac, Eric. 2022. The Grammaticalization of Evidentiality in English. English Language and Linguistics 26: 331–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2012. Agreements that Occur Mainly in Main Clauses. In Main Clause Phenomena: New Horizons. Edited by Lobke Aelbrecht, Liliane Haegeman and Rachel Nye. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 79–112. [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2017. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph. In Agreement Beyond Phi. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2022. Syntax in the Treetops. Cambridge: MIT University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Sarah E. 2010. Evidentiality and the Structure of Speech Acts. Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Sarah E. 2021. Evidentiality, Modality, and Speech Acts. Annual Review of Linguistics 7: 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, Mark. 2018. Default Case. The Even Yearbook 13: 29–55. [Google Scholar]