Nonverbal Communication in Classroom Interaction and Its Role in Italian Foreign Language Teaching and Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teachers’ Gestures in the L2 Classroom: Literature Review

- (a)

- Gestures to inform about language: these may refer to grammar, vocabulary, and phonology. Teachers may use them to explain morphosyntax and temporality (Matsumoto and Mueller Dobs 2016; Bianchi and Diadori 2018) or to focus on the forms and meanings of action verbs (Tellier and Stam 2012) and lexical items (Lazaraton 2004; Smotrova and Lantolf 2013; García-Gámez and Macizo 2023). They can also help in the physical production of phonemes and prosody (Smotrova 2017). Such gestures occur to solve misunderstandings, to anticipate students’ difficulties, to facilitate oral comprehension5, and to help students’ performance.

- (b)

- Gestures as assessment tools: they are used to approve students’ performance or, as corrective feedback, to report an error without verbally interrupting a student’s production (Mackey et al. 2000; Seo and Koshik 2010)

- (c)

- Gestures to manage the class: they are often used to indicate the beginning and the end of an activity and to decide speech turns (Mondada 2007). Gestures and eye gaze may be used by teachers in organizing students when giving instructions (Arnold 2012; Käänta 2012; Hall and Smotrova 2013; Azaoui 2014). Teachers may fill a period of silence with gestures with different communicative functions, e.g., to elicit an answer from the class, to help the interlocutor in verbal oral production, or to fill in an incomplete sentence (Stam and Tellier 2017).

1.2. Students’ Gestures in the L2 Classroom: Literature Review

1.3. Shared Gestures in the L2 Classroom: Literature Review

1.4. The Case of Teachers’ Gestures in the L2 Italian Classroom

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Iconic Gestures

- EXAMPLE 1

| DF in campagna ((CNV indica con le mani la forma di un oggetto piatto) ci sono le panche) per sedere |

- EXAMPLE 2

| DF CHE VUOL DIRE PIGRA, (.) qualcuno sa cosa significa pigra, SF quando una persona non (1.0) vuole fare niente DF ((CNV annuisce)) È IL CONTRARIO DI PIGRO È ATTIVO DINAMICO) |

- EXAMPLE 3

| DF qui c’è la tenda perché così ((CNV movimento delle mani mima l’atto di entrare) non entra) il sole nella stanza |

- EXAMPLE 4

| DF Tu saresti più aggressivo? fisicamente ((CNV fa segno di stringere un braccio e tirare con le mani) cioè con le mani) SM La lingua è ferma e le mani lavorano ((CNV ride). |

3.2. Metaphoric Gestures

- EXAMPLE 5

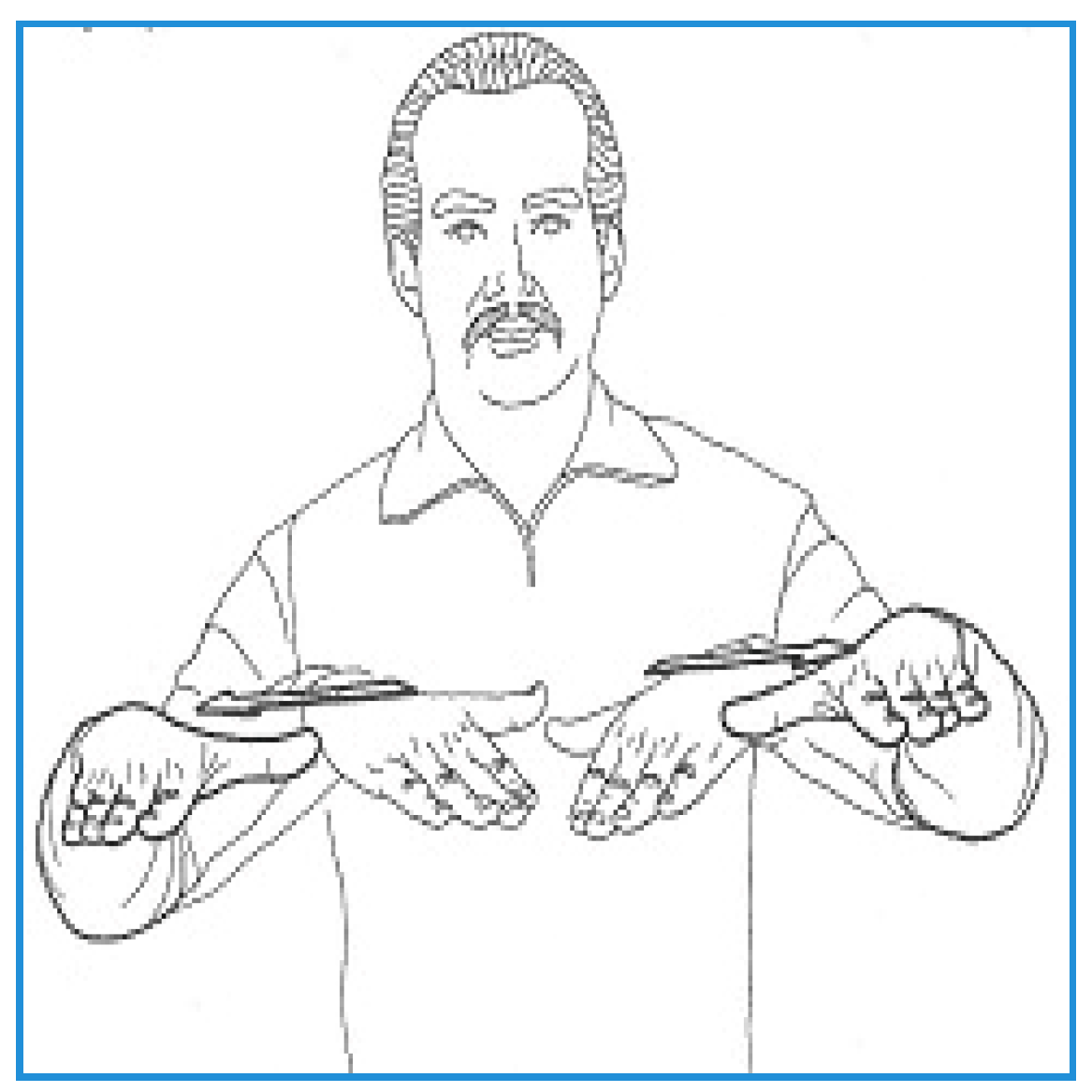

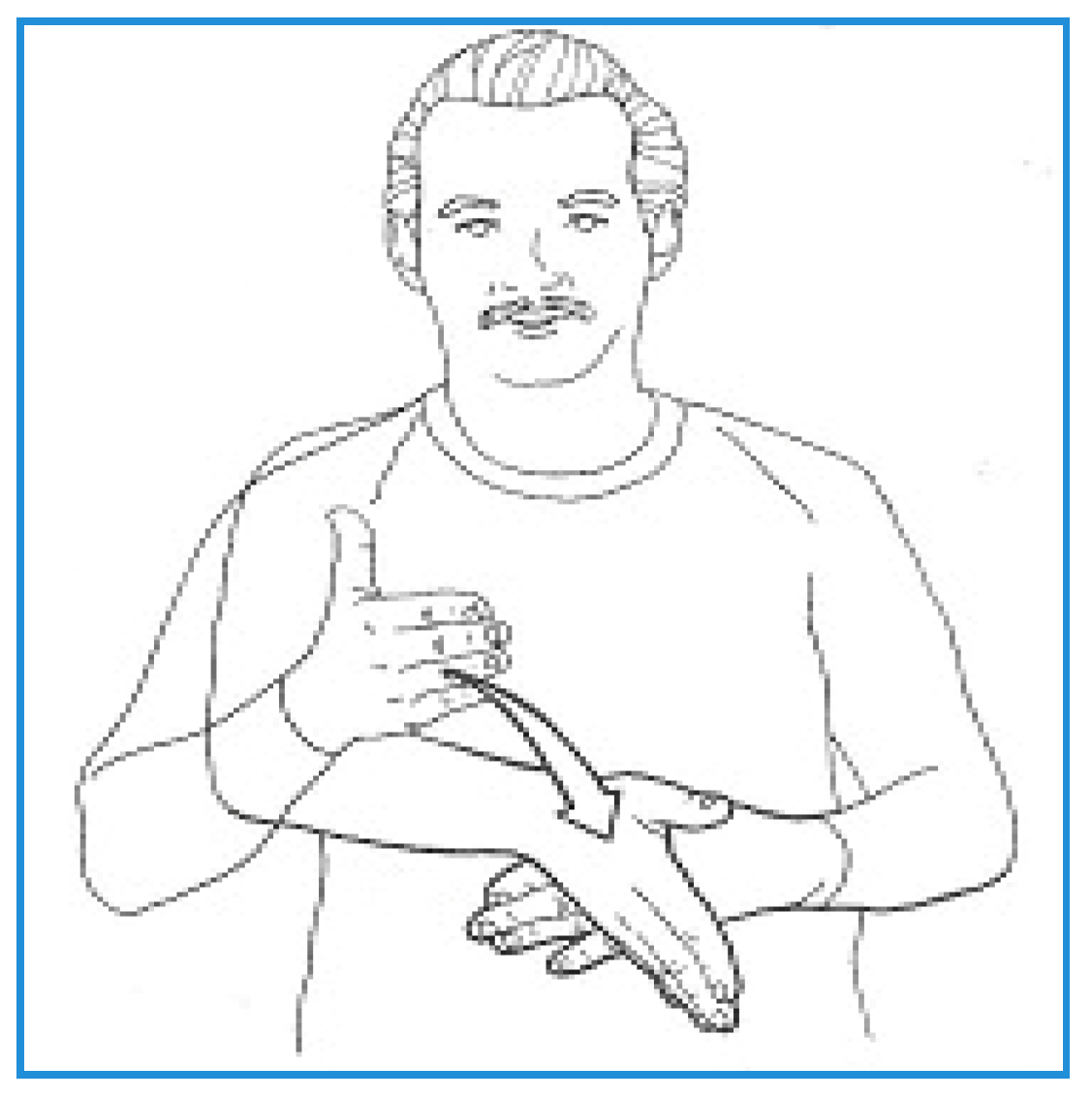

| DF qual è il congiuntivo del verbo stare, CLA stia DF che stia dormendo, (1.0) ((CNV allarga le braccia) chiaro ragazzi,) (.)quindi noi abbiamo lavorato ((CNV con le braccia disegna un cerchio immaginario) intorno all’idea) di esprimere un dubbio (.) adesso formiamo un aggettivo dalla parola dubbio, (.) |

- EXAMPLE 6

| DF quando vogliamo raccontare↑ (.) un’esperienza (.) passata. (.) d’accordo? (.) una cosa↑ (.) che è (.) del nostro passato (.) recente (.) ((CNV il pollice indietro indica un’azione passata) cinque minuti fa) (.) o anche molto lontano (.) venti anni fa. (.) d’accordo? (.) bene (.) dobbiamo usare questi due↑ (.) eh: mhm tempi verbali↑ |

- EXAMPLE 7

| DF (.) allora (.) ((CNV la mano indica l’altezza di un bambino) quando ero bambina quando ero piccola) (1.0) e a questo punto (.) anche se (.) il fatto (.) è di molto (.) tempo fa: (.) eh, (.) è successo (.) alcuni anni fa ((ridendo) insomma tu sei giovane ma (.) quando eri piccola) sono già passati qualcosa come vent’anni (.) ma BENE (.) in questo caso tu:: usi (.) preferibilmente (.) il passato prossimo |

- EXAMPLE 8

| SM (1.0) faccio una gas- de- gos- degustia- (.) degustazione (.) mangio il formaggio (.) con il miele e la marmellata di uva ((leggendo alla lavagna)) ANCH’IO CLA ((CNV risate)) DM anch’io? ((CNV movimento rotatorio della mano destra in avanti) e poi?) (3.0) che altro che altro (1.0) “what else” che altro altro |

- EXAMPLE 9

| DF è un periodo ipotetico della possibilità (.) cioè tutto può cambiare (.) magari (1.0) ((CNV guarda l’orologio) tra cinque minuti) viene fuori il sole e usciamo (.) eh, (.) però (.) |

- EXAMPLE 10

| DM nell’attività che vorrei fare ((CNV l’indice della mano destra indica in basso) oggi) con voi (1.0) vorrei anche (.) fare una specie di mercato |

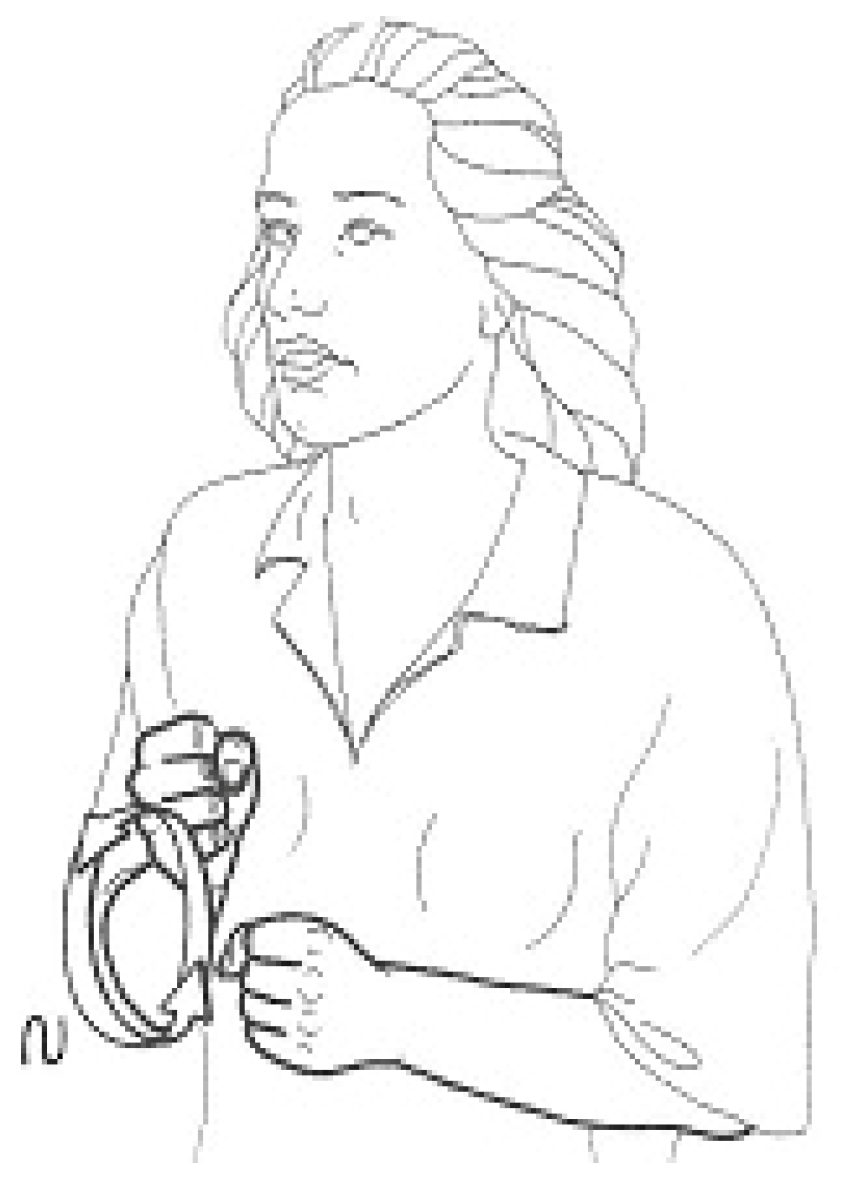

3.3. Metaphoric Gestures: The Case of Italian Emblems

- EXAMPLE 1119

| DF ho camminato) (.) ho mangiato (.) ho studiato (.) queste sono (.) azioni (.) che (.) ((CNV indica con la mano un punto di inizio) iniziano) (.) ((CNV scuote la mano in senso orizzontale a indicare la fine di qualcosa) e finiscono) (.) ieri (.) ho studiato (.) ((CNV con la mano indica il numero tre) tre ore) (2.0) ((CNV indica la frase alla lavagna) sono stata in Francia) (.) per ((CNV indica con il pollice il numero uno) un mese) (2.0) non è importante (.) ((CNV con le braccia larghe disegna un segmento in aria) quanto tempo è lunga quanto è lunga quest’azione) (.) non è importante ((CNV fa il gesto della mano sotto il mento) chi se ne frega) ((CNV cerchia una parola alla lavagna)) (3.0) ((CNV con l’indice alzato segnala il numero uno) un mese un’ora un minuto un giorno) (.) non importa (.) che cosa, è importante. SM1 °l’azione° SM2 ((CNV annuisce) è importante l’azione,) |

- ((CNV indica con la mano un punto di inizio) iniziano);

- ((CNV scuote la mano in senso orizzontale a indicare la fine di qualcosa) e finiscono);

- ((CNV con la mano indica il numero tre) tre ore);

- ((CNV indica la frase alla lavagna) sono stata in Francia);

- ((CNV indica con il pollice il numero uno) un mese);

- non è importante ((CNV con le braccia larghe disegna un segmento in aria) quanto tempo è lunga quanto è lunga quest’azione);

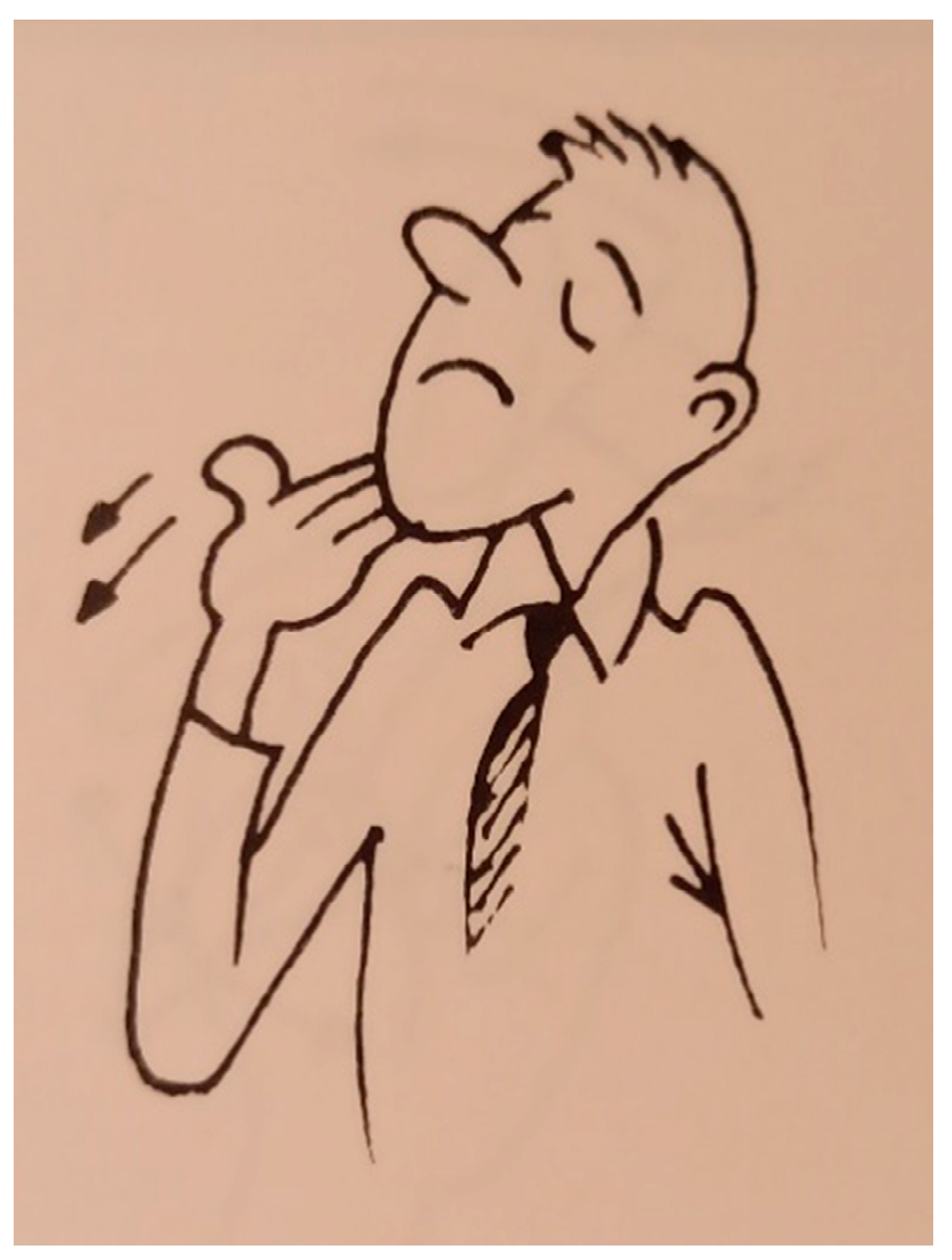

- non è importante ((CNV fa il gesto della mano sotto il mento) chi se ne frega);

- ((CNV cerchia una parola alla lavagna));

- ((CNV con l’indice alzato segnala il numero uno) un mese un’ora un minuto un giorno);

- ((CNV annuisce) è importante l’azione).

3.4. Mirroring Effect in Teacher/Students’ Interaction

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Brief pause, usually between 0.08 and 0.2 s | (.) |

| Longer pauses (0.2, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0 s, etc.) | (0.2) |

| Underlining indicates emphasis | text |

| Upper case indicates syllables or words louder than surrounding speech by the same speaker | TEXT |

| Degree signs indicate syllables or words distinctly quieter than surrounding speech by the same speaker | °text° |

| Falling intonation | text. |

| Flat intonation | text_ |

| Slight rising intonation | text, |

| Sharp rising intonation | text? |

| Colon indicates prolonged vowel | te:xt |

| Marked shift in pitch, up (↑) or down (↓). Double arrows can be used with extreme pitch shifts. | ↑text ↓text |

| Right/left carats indicate increased speaking rate (speeding up) | >text< |

| Left/right carats indicate decreased speaking rate (slowing down) | <text> |

| Double parentheses contain analyst comments or descriptions | (( )) |

| Parentheses indicate uncertain text | (text) |

| Parentheses and asterisks indicate inintelligible text | (***) |

| Overlapping talk | [text] [text] |

| End of turn and beginning of the next one with no gap/pause in between | = |

| Parts in bold are used to identify the section of text considered for analysis | text |

| Text in a different language, code-switching | “text” |

| Reported word or sentence | text |

| Nonverbal communication and symultaneous speech (CNV Comunicazione Non Verbale) | ((CNV) text) |

| Female teacher (DF Docente Femmina) | DF |

| Male teacher (DM Docente Maschio) | DM |

| Female student (FS Studentessa Femmina) | SF |

| Male student (SM Studente Maschio) | SM |

| Class | CLA |

| 1 | Recent cognitive studies consider gestures as simulated actions, a kind of visible embodiment that arise from an embodied cognitive system and mental imagery (Hostetter and Alibali 2008). On the deep connection of gesture, speech and cognition see also (McNeill 1992, 2000, 2005). |

| 2 | A holistic approach to gestures in second language acquisition and classroom research can be found in various introductory studies like (McCafferty and Stam 2009, chap. 5). |

| 3 | For English L2 see, among others, (Hauge 1998, 1999, 2000; Lazaraton 2004; Wanphet 2015; Matsumoto and Mueller Dobs 2016; Matsumoto 2019; Yamane et al. 2019). For Italian L2 see (Peltier and McCafferty 2010; Tummillo 2016; Ery and Huszthy 2017; Bianchi and Diadori 2018; Huszthy 2020; Capponi 2022). For French L2 see (Faraco 2010; Saydi 2010; Azaoui 2014; Tellier et al. 2021). For German L2 see (Heidemann 1983; Kodakos 1992; Rosenbusch 1995; Hammer 1995; Kaiser 1998). For Spanish L2 see (Cestero 1999, 2017; Belío-Apaolaza and Hernández Muñoz 2021). A comparison between gestures in teaching Italian L2 and Korean L2 in Korea is offered in (Mondin 2022). On gestures in teaching German L2 and Persian L2 in the USA see (Taleghani-Nikazm 2008). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | An example on algebra lessons facilitated by the use of gestures as scaffolding technique in (Alibali and Nathan 2007). |

| 6 | On students’ embodied actions cf. (Gullberg 1998, 2008, 2014; Gullberg and McCafferty 2008; Goldin-Meadow and Alibali 2013). |

| 7 | “Interlanguage” is the idiolect of an L2 student, containing some aspects of the L2, some of the L1 or other familiar languages, and some that are due to one’s own hypothesis of how L2 functions (Selinker 1972; Tarone and Han 2014). |

| 8 | On students’ gestures as visible representation of their cognitive activity cf. (McNeill 1992, 2000; Kita 2000; Goldin-Meadow 2003, 2004; Olsher 2008; Ianì and Formichella 2017; De Iaco 2020). For a scientifically based argument on the connection of gesture and speech from a neurological point of view, see (Willems et al. 2007). |

| 9 | On the positive impact of gestures on L2 listening comprehension cf. (Kellerman 1992; Sueyoshi and Hardison 2005; Tellier 2009). |

| 10 | On misunderstandings due to symbolic or culturally specific gestures cf. (Azaoui 2014; Hauge 1998, 1999; Sime 2006, 2008; Tellier 2008a, 2009). |

| 11 | See, for example, (Matsumoto and Hwang 2013) for cultural differences in emblematic gestures and Pika’s studies (e.g., Pika et al. 2006) for cultural differences using gestures in specific contexts. |

| 12 | On teachers’ gestures in the L2 Italian classroom see, among others, (Diadori 2002, 2013; Ery and Huszthy 2017; Capponi 2022). |

| 13 | CLODIS—Corpus di Lingua Orale dei Docenti di Italiano per Stranieri (described in Diadori and Monami 2020; Diadori 2021) is a audiovisual database which is part of a research project on Italian language teaching, directed by Pierangela Diadori at the Università per Stranieri di Siena. An appendix with CLODIS transcription symbols can be found at the end of this paper. |

| 14 | For this study, all the selection, recording, and coding processes were conducted by the author, who has extensive experience in the subject. |

| 15 | See (Krashen 1985) for the hypothesis of “comprehensible input” in foreign language teaching. |

| 16 | The images of LIS signs are taken from Angelini et al. (1991). On Italian LIS see also (Volterra 2004). |

| 17 | This representation is to be found also in an essay on Neapolitan gestures of the XIX century (De Iorio 1832), and in (Angelini et al. 1991). |

| 18 | 100 contemporary Italian emblems are described in (Diadori 1990) (see also Caon 2010; Nobili 2023). On symbolic gestures that occur sometimes with the same form but with different meanings in various cultures, see (Morris 1994) and on nonverbal cross-cultural differences (Kita 2009). |

| 19 | The image of the chin flick gesture expressing “I don’t care” is taken from Diadori (1990, p. 54). |

| 20 | According to (Morris et al. 1979), who investigated in their different meanings these 20 gestures by interviewing 1200 informants in 40 towns all over Europe, the chin flick gesture, also attested in De Iorio (1832), is mostly used in Italy with the meaning of “I don’t care” but also as a negative answer, especially in southern Italy. In the rest of Europe either it is not used (half of the informants) or it is used with different meanings. |

| 21 | On the role of laughter in interaction see also (Glenn 2003). |

| 22 | On the importance of nonverbal pedagogical competence in teacher training see, among others, (Heidemann 1983; Neill and Caswell 1993; Freeman and Johnson 1998; Alibali et al. 2013; Tellier and Cadet 2014; Cestero 2017; Tellier et al. 2021; Stam and Tellier 2022). |

| 23 | Southern European, Mediterranean, and Latin American countries are traditionally referred to as “high-contact cultures”, where people tend to use more gestures, touch each other more often, maintain closer interpersonal distance, make more eye contact, and speak louder, as opposed to “low-contact cultures” of Northern European, Northern American, and Eastern countries (Morris et al. 1979, e.g., considered 20 “emblems” in 25 countries in the Mediterranean area). |

References

- Abner, Natasha, Kensy Cooperrider, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2015. Gesture for Linguists: A Handy Primer. Language and Linguistics Compass 9: 437–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibali, Martha W., and Mitchell J. Nathan. 2007. Teachers’ gestures as a means of scaffolding students’ understanding: Evidence from an early algebra lesson. In Video Research in the Learning Sciences. Edited by Ricki Goldman, Roy Pea, Brigid Barron and Sharon J. Derry. Mahwah: Erlbaum, pp. 349–65. [Google Scholar]

- Alibali, Martha W., Andrew G. Young, Noelle M. Crooks, Amelia Yeo, Matthew S. Wolfgram, Jasmine M. Ledesma, Mitchel J. Nathan, Ruth Breckinridge Church, and Eric J. Knuth. 2013. Students learn more when their teacher has learned to gesture effectively. Gesture 13: 210–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibali, Martha W., Dana C. Heath, and Heather J. Myers. 2001. Effects of visibility between speaker and listener on gesture production: Some gestures are meant to be seen. Journal of Memory and Language 44: 169–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Linda Q. 1995. The effects of emblematic gestures on the development and access of mental representations of French expressions. The Modern Language Journal 79: 521–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Linda Q. 2000. Nonverbal accommodations in foreign language teacher talk. Applied Language Learning 11: 155–76. [Google Scholar]

- Angelini, Natalia, Rossano Borgioli, Anna Folchi, and Matteo Mastromatteo, eds. 1991. I Primi 400 Segni. Piccolo Dizionario Della Lingua Italiana dei Segni per Comunicare con i Sordi. Firenze: La Nuova Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Lynnette. 2012. Dialogic embodied action. Using gesture to organize sequence and participation in instructional interaction. Resarch on Language & Social Interaction 45: 269–96. [Google Scholar]

- Azaoui, Brahim. 2014. Multimodalité des signes et enjeux énonciatifs en classe de FL1/FLS. In Le Corp et la Voix de L’enseignant: Mise en Context Théorique et Pratique. Edited by Marion Tellier and Lucile Cadet. Paris: Maison des Langues, pp. 115–26. [Google Scholar]

- Belío-Apaolaza, Helena S., and Natividad Hernández Muñoz. 2021. Emblematic gestures learning in Spanish as L2/FL: Interactions between types of gestures and tasks. Language Teaching Research 7: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Valentina, and Pierangela Diadori. 2018. Gesti di tempo nella classe di italiano L2. SILTA—Studi Italiani di Linguistica Teorica e Applicata XLVII: 293–316. [Google Scholar]

- Caon, Fabio. 2010. Dizionario dei Gesti Degli Italiani. Una Prospettiva Interculturale. Perugia: Guerra. [Google Scholar]

- Capponi, Lavinia. 2022. Grammatiche del corpo. Un percorso sulla gestualità nella didattica dell’italiano L2. LIA Lingua in Azione 1–2: 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cestero, Ana M. 1999. La Comunicación no Verbal y Enseñanza de Lenguas Extranjeras. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Cestero, Ana M. 2017. La Comunicación no Verbal, In Manual del Profesor de ELE. Edited by Ana M. Cestero Mancera and Immaculada Penadés Martínez. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá, pp. 1051–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, Kensy, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2017. Gesture, Language, and Cognition. In Cambridge Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Edited by Barbara Dancygier. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 118–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Tove I., and Susanne Ludvigsen. 2014. How I see what you’re saying: The role of gestures in native and foreign language listening comprehension. The Modern Language Journal 98: 813–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iaco, Moira. 2020. Mani che aiutano ad apprendere. Gesti, lingue, educazione linguistica. Lecce: Pensa Multimedia. [Google Scholar]

- De Iorio, Andrea. 1832. La Mimica Degli Antichi Investigata nel Gestire Napoletano. Napoli: Associazione Napoletana per i Monumenti e il Paesaggio. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, Pierangela. 1990. Senza Parole. 100 Gesti Degli Italiani. Roma: Bonacci. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, Pierangela. 2002. La gestualità nell’insegnamento dell’italiano lingua straniera. In La Competenza Linguistica in Italiano: Non Solo Parole. Edited by Marie-Reine Blommaert. Brussels: Studiereek Interfacultair Departement voor Taalonderwijs, Vrije Universiteit, pp. 23–65. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, Pierangela. 2013. Gestualità e didattica della seconda lingua: Questioni interculturali. In Aspetti Comunicativi e Interculturali Nell’insegnamento delle Lingue. Edited by Enrico Borello and Maria Cecilia Luise. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 71–102. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, Pierangela. 2021. CLODIS. Una banca dati di natura multimodale per l’insegnamento dell’italiano L2. In La Nuova DITALS Risponde. Edited by Pierangela Diadori. Roma: Edilingua, pp. 504–9. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, Pierangela. 2022. Ridere nella classe di italiano L2: Non solo humor. Un’indagine corpus-based in contesti universitari in Italia e all’estero. RISU Rivista Italiana di Studi sull’Umorismo 5: 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Diadori, Pierangela, and Elena Monami. 2020. CLODIS: Una banca dati multimodale per la formazione dei docenti di italiano L2. RID—Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia. Lingue, Dialetti, Società XLIV: 151–69. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, David. 1941. Gesture and Environment. New York: King’S Crown Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, Paul, and Wallace Friesen. 1969. The Repertoire of Nonverbal Behavior: Categories, Origins, Usage, and Coding. Semiotica 1: 49–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ery, Anna, and Alma Huszthy. 2017. Le caratteristiche verbali e non verbali della comunicazione dell’insegnante di italiano. In Presente e Futuro Della Lingua e Letteratura Italiana: Problemi, Metodi, Ricerche. Edited by Elena Pîrvu. Firenze: Cesati, pp. 383–94. [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen, Søren W., and Johannes Wagner. 2013. Recurring and shared gestures in the L2 classroom: Resources for teaching and learning. European Journal of Applied Linguistics 1: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraco, Martine. 2010. Geste et prosodie didactiques dans l’enseignement des structures langagières en FLE. In Enseigner les Structures Langagières en FLE. Edited by Olga Galatanu, Michel Pierrard, Dan Van Raemdonck, Marie-Eve Damar, Nancy Kemps and Ellen Schoonheere. Brussels: Peter Lang, pp. 203–12. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Donald, and Karen E. Johnson. 1998. Reconceptualizing the knowledge-base of language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly 32: 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, Alexia, and Susan E. Brennan. 2013. Speakers adapt gestures to addressees’ knowledge: Implications for models of co-speech gesture. Language and Cognitive Processes 29: 435–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gámez, Ana B., and Pedro Macizo. 2023. Gestures as Scaffolding to Learn Vocabulary in a Foreign Language. Brain Sciences 13: 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, Phillip. 2003. Laughter in Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2003. Hearing Gesture: How Our Hands Help Us to Think. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2004. Gesture’s Role in the Learning Process. Theory into Practice 43: 314–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan, and Martha W. Alibali. 2013. Gesture’s role in speaking, learning, and creating language. Annual Review of Psychology 64: 257–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Barbara, and Dorothy Grant Hennings. 1971. The Teacher Moves: An Analysis of Non-Verbal Activity. Theory and Research in Teaching. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano, Maria, and Marianne Gullberg. 2013. Gesture production and speech fluency in competent speakers and language learners. In Proceedings of the Tilburg Gesture Research Meeting (TiGeR). Tilburg: Tilburg University. [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg, Marianne. 1998. Gesture as a Communication Strategy in Second Language Discourse. Lund: Lund University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg, Marianne. 2008. Gestures and second language acquisition. In Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Nick C. Ellis and Peter Robinson. London: Routledge, pp. 276–305. [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg, Marianne. 2014. Gestures and second language acquisition. In Body-Language-Communication: An International Handbook on Multimodality in Human Interaction. Edited by Cornelia Müller, Alan J. Cienki, Ellen Fricke, Silva H. Ladewig, David McNeill and Sedinha Tessendorf. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 1868–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg, Marianne, and Steven G. McCafferty. 2008. Introduction to Gesture and SLA: Toward an Integrated Approach. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 30: 133–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Joan K., and Stephen D. Looney, eds. 2019. The Embodied Work of Teaching. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Joan K., and Tetyana Smotrova. 2013. Teacher self-talk: Interactional resource for managing instruction and eliciting sympathy. Journal of Pragmatics 47: 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Wolfgang. 1995. Körpersprache des Lehrers. Rostocker Pädagogische Hefte; Rostock: LISA Studienseminar Rostock für Gymnasien/Landesbildstelle. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, Elisabeth. 1998. Gesture in the EFL class: An aid to communication or a source of confusion? In Crosscultural Capability. Edited by Danielle Killik and Mike Parry. Leeds: Leeds Metropolitan University, pp. 271–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, Elisabeth. 1999. Some common emblems used by British English teachers in EFL classes. In Crosscultural Capability. Promoting the Discipline. Edited by Danielle Killik and Mike Parry. Leeds: Leeds Metropolitan University, pp. 405–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, Elisabeth. 2000. The Role of Gesture in British ELT in a University Setting. Southampton: University of Southampton. [Google Scholar]

- Heidemann, Rudolf. 1983. Körpersprache vor der Klasse. Ein praxisnahesTrainingsprogramm zum Lehrerverhalten. Heidelberg: Quelle. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter, Autumn B., and Martha W. Alibali. 2008. Visible Embodiment: Gestures as Simulated Action. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 15: 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszthy, Alma. 2020. La comunicazione dell’insegnante durante la lezione d’italiano in contesto scolastico ungherese: Caratteristiche comuni e strategie individuali. ItalianoLinguaDue 2: 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ianì, Francesco, and Marco Formichella. 2017. Il ruolo cognitivo dei gesti. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 4: 849–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, Gail. 1984. Transcription Notation. In Structures of Social Interaction. Edited by John Atkinson and John Heritage. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. ix–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, Gail. 2004. Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation. Edited by Gene H. Lerner. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Susan, and Isabel Parra. 2003. Multiple layers of meaning in an oral proficiency test. The complementary role of nonverbal, paralinguistic and verbal behaviors in assessment decisions. Modern Language Journal 87: 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käänta, Leila. 2012. Teacher’s embodied allocations in instructional interaction. Classroom Discourse 3: 166–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Constanze. 1998. Körpersprache der Schüler. München: Luchtenhand. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Seokmin, Gregory L. Hallman, Lisa K. Son, and John B. Black. 2013. The different benefits from different gestures in understanding a concept. Journal of Science Education and Technology 22: 825–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellerman, Susan. 1992. “I see what you mean”. The role of kinesic behavior in listening and implications for foreign and second language learning. Applied Linguistics 13: 239–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Spencer D., Dale J. Barr, Ruth Beckinridge Church, and Katheryn Lynch. 1999. Offering a hand to pragmatic understanding: The role of speech and gesture in comprehension and memory. Journal of Memory and Language 40: 577–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendon, Adam. 1980. Gesticulation and Speech. Two aspects of the process of utterance. In The Relationship of Verbal and Nonverbal Communication. Edited by Mary R. Key. The Hague: Mouton, pp. 207–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kendon, Adam. 1995. Gestures as illocutionary and discourse structure markers in Southern Italian conversation. Journal of Pragmatics 23: 247–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendon, Adam. 2004. Gesture. Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, Sotaro. 2000. How representational gestures help speaking. In Language and Gesture: Window into Thought and Action. Edited by David McNeill. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 162–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, Sotaro. 2009. Cross-cultural variation of speech-accompanying gesture: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes 24: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodakos, Anastassios. 1992. Zur Körpersprache des Lehrers im Unterricht. Stuttgart: Flugschriften der Volkshochschule Stuttgart, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen, Stephen D. 1985. The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, Robert M., and Ezequiel Morsella. 2001. Movements Facilitates Speech Production: A Gestural Feedback Model. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaraton, Anne. 2004. Gesture and Speech in the vocabulary explanations of one ESL teacher: A Microanalytic Inquiry. Language Learning 54: 79–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedonia, Manuela, and Wolfgang Klimesch. 2014. Long-term effects of gestures on memory for foreign language word trained in the classroom. Mind, Brain and Education 8: 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, Alison, Susan Gass, and Kim McDonough. 2000. How do learners perceive interactional feedback? Studies in Second Language Acquisition 22: 471–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majlesi, Reza, and Numa Markee. 2018. Multimodality in Second Language Talk: The Impact of Video Analysis on SLA Research. Tartu Semiotics Library 19: 247–60. [Google Scholar]

- Markee, Numa, ed. 2015. The Handbook of Classroom Discourse and Interaction. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, David, and Hyi Sung Hwang. 2013. Cultural influences on nonverbal behavior. In Nonverbal Communication: Science and Applications. Edited by David Matsumoto, Mark G. Frank and Hyi Sung Hwang. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, Yumi. 2019. Embodied Actions and Gestures as Interactional Resources for Teaching in a Second Language Writing Classroom. In The Embodied Work of Teaching. Edited by Joan K. Hall and Stephen D. Looney. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, Yumi, and Abby Mueller Dobs. 2016. Pedagogical gestures as interactional resources for teaching and learning tense and aspect in the ESL grammar classroom. Language Learning 67: 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, Steven G. 2002. Gesture and Creating Zones of Proximal Development for Second Language Learning. The Modern Language Journal 86: 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, Steven G., and Gale Stam, eds. 2009. Gesture: Second Language Acquisition and Classroom Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, David. 1992. Hand and Mind: What Gesture Reveal about Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, David, ed. 2000. Language and Gesture. Window into Thought and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, David. 2005. Gesture and Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2007. Multimodal resources for turn-taking: Pointing and the emergence of possible next speaker. Discourse Studies 9: 194–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2014. Pointing, talk, and the bodies. Reference and joint attention as embodied interactional achievements. In From Gesture in Conversation to Visible Action as Utterance. Edited by Mandana Seyfeddinipur and Marianne Gullberg. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mondin, Lisa. 2022. Il ruolo del linguaggio non verbale nella didattica delle lingue. Analisi della gestualità utilizzata dai docenti italiani e coreani nelle lezioni. Mater’s thesis, Università per Stranieri di Siena, Siena, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Desmond. 1994. Bodytalk. A World Guide to Gestures. London: Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Desmond, Peter Collett, Peter Marsh, and Marie O’Shaughnessy. 1979. Gestures. London: Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Neill, Sean, and Chris Caswell. 1993. Body Language for Competent Teachers. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Neu, Joyce. 1990. Assessing the role of nonverbal communication in the acquisition of communicative competence in L2. In Developing Communicative Competence in a Second Language. Edited by Robin C. Scarcella, Elaine S. Andersen and Stephen D. Krashen. New York: Newbury House, pp. 121–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nobili, Claudio. 2023. L’italiano Senza Parole: Segni, Gesti, Silenzi. Firenze: Cesati. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Rafael, and Kensy Cooperrider. 2013. The tangle of space and time in human cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17: 220–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsher, David. 2008. Gesturally-enhanced repeats in the repair turn: Communication strategy or cognitive language-learning tool? In Gesture. Second Language Acwuisition and Classroom Research. Edited by Steven G. McCafferty and Gale Stam. New York: Routledge, pp. 109–30. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jaeuk. 2017. Multimodality as an Interactional Resource for Classroom Interactional Competence. Linguistics 3: 121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, Ilaria Nardotto, and Steven G. McCafferty. 2010. Gesture and identity in the teaching and learning Italian. Mind, Culture and Activity 17: 331–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pika, Simone, Elena Nicoladis, and Paula F. Marentette. 2006. A cross-cultural study on the use of gestures: Evidence for cross-linguistic transfer? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 9: 319–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, Isabella. 2006. Le parole del Corpo. Introduzione alla Comunicazione Multimodale. Roma: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbusch, Heinz S. 1995. Nonverbale Kommunikation im Unterricht. In Körpersprache in der Schulische Erziehung. Edited by Heinz S. Rosenbusch and Otto Schober. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider. [Google Scholar]

- Saydi, Tilda. 2010. Mimogestualité: Une composante pragmatique pour les apprenants du FLE. Synergies Turquie 3: 205–13. [Google Scholar]

- Selinker, Larry. 1972. Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 10: 209–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Mi-Suk, and Irene Koshik. 2010. A conversation analytic study of gestures that engender repair in EFL conversational tutoring. Journal of Pragmatics 42: 2219–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, Olcay. 2015. Social Interaction and L2 Classroom Discourse. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seymen, Aylin. 2014. Einsatz der Körpersprache im Fremdsprachenunterricht. International Journal of Language Academy 2: 546–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sime, Daniela. 2006. What do learners make of teacher’s gestures in the language classroom? International Review of Applied Linguistics 44: 211–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sime, Daniela. 2008. Because of her gesture, it’s easy to understandd. Learners’ perception of teachers’ gestures in the foreign language class. In Gesture: Second Language Acquisition and Classroom Research. Edited by Steven G. McCafferty and Gale Stam. New York: Routledge, pp. 259–79. [Google Scholar]

- Smotrova, Tetyana. 2017. Making Pronunciation Visible: Gesture in Teaching Pronunciation. TESOL Quarterly 51: 59–89. [Google Scholar]

- Smotrova, Tetyana, and James P. Lantolf. 2013. The function of gesture in lexically focused L2 instructional conversations. The Modern Language Journal 97: 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, Gale. 2008. What gestures reveal about second language acquisition. In Gesture: Second Language Acquisition and Classroom Research. Edited by Steven G. McCafferty and Gale Stam. New York: Routledge, pp. 231–55. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, Gale. 2012. Gestes et recherche de mots en langue seconde. In La Corporalité du Langage: Multimodalité, Discours et Écriture. Edited by Robert Vion, Alain Giacomi and Claude Vargas. Aix-en-Provence: Université de Provence, pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, Gale. 2016. Gesture as a window onto conceptualization on multiple tasks: Implications for second language teaching. Yearbook of the German Cogitive Association 4: 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, Gale. 2018. Gesture and speaking a second language. In Speaking in a L2. Edited by Rosa Alonso Alonso. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, Gale, and Marion Tellier. 2017. The sound of silence: The functions of gestures in pauses in native and non-native interaction. In Why Gesture? How the Hands Function in Speaking, Thinking and Communicating. Edited by Ruth Breckinridge Church, Martha W. Alibali and Spencer D. Kelly. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 353–77. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, Gale, and Marion Tellier. 2022. Gesture helps second and foreign language learning and teaching. In Gesture in Language: Development Across the Lifespan. Edited by Aliyah Morgenstern and Susan Goldin-Meadow. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 335–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sueyoshi, Ayano, and Debra M. Hardison. 2005. The role of gestures and facial cues in second language listening comprehension. Language Learning 55: 661–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabensky, Alexis. 2008. Expository discourse in a second language classroom: How learners use gesture. In Gesture: Second Language Acquisition and Classroom Research. Edited by Steven G. McCafferty and Gale Stam. New York: Routledge, pp. 298–320. [Google Scholar]

- Taleghani-Nikazm, Carmen. 2008. Gestures in Foreign Language Classroom: An Empirical Analysis of their Organization and Function. In Selected Proceedings of the 2007 Second Language Research Forum. Edited by Melissa Bowles, Rebecca Foote, Silvia Perpiñán and Rakesh Mohan Bhatt. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 229–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tarone, Elaine, and ZhaoHong Han, eds. 2014. Interlanguage. Fourty Years Later. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, Marion. 2008a. Dire avec des gestes. Français dans le Monde. Recherche et Application 44: 219–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, Marion. 2008b. The effect of gestures on second language memorization by young children. Gesture 8: 219–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellier, Marion. 2009. Usage pédagogique et perception de la multimodalité pour l’accès au sens en langue étrangère. In La Place des Savoir Oraux dans le Context Scolaire D’aujourd’hui. Edited by Réal Bergeron, Ginette Plessis-Belaire and Lizanne Lafontaine. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Quebec, pp. 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, Marion, and Gale Stam. 2012. Stratégies verbales et gestuelles dans l’explication lexicale d’un verbe d’action. In Spécificités et Diversité des Interactions Didactiques. Edited by Véronique Rivière. Paris: Riveneuve, pp. 357–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, Marion, and Lucile Cadet, eds. 2014. Le corp et la voix de l’enseignant. Théorie et pratique. Paris: Maison des Langues. [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, Marion, Gale Stam, and Alain Ghio. 2021. How future language teachers adapt their gestures to their interlocutor. Gesture 20: 30–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickle-Degnen, Linda, and Robert Rosenthal. 1990. The nature of rapport and its nonverbal correlates. Psychological Inquiry 1: 285–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummillo, Federica. 2016. Gestualità e didattica L2. Spunti teorici e piste di lavoro. LEND Lingua e Nuova Didattica 2: 122–31. [Google Scholar]

- Volterra, Virginia, ed. 2004. La Lingua dei Segni italiana. La Comunicazione Visivo-Gestuale dei Sordi. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Steve. 2006. Investigating Classroom Discourse. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Steve. 2013. Classroom Discourse and Teacher Development. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Steve. 2014. Classroom Interaction for Language Teachers. Alexandria: TESOL. [Google Scholar]

- Wanphet, Phalangchok. 2015. A conversation analysis of EFL teachers’ gesture in language elicitation stage. ELIA Estudios de Linguística Inglesa Aplicada 15: 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Willems, Roel M., Asli Özyürek, and Peter Hagoort. 2007. When language meets action: The neural integration of gesture and speech. Cerebral Cortex 17: 2322–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, Noriko, Masahiro Shinya, Brian Teaman, Marina Ogawa, and Soushi Akahoshi. 2019. Mirroring beat gestures: Effects on EFL learners. Paper presented at 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Melbourne, Australia, August 5–9; pp. 3523–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Jang-Yuan, and Wei Guo. 2012. Who Is Controlling the Interaction? The Effect of Nonverbal Mirroring on Teacher-Student Rapport. US-China Education Review 7: 662–69. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diadori, P. Nonverbal Communication in Classroom Interaction and Its Role in Italian Foreign Language Teaching and Learning. Languages 2024, 9, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050164

Diadori P. Nonverbal Communication in Classroom Interaction and Its Role in Italian Foreign Language Teaching and Learning. Languages. 2024; 9(5):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050164

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiadori, Pierangela. 2024. "Nonverbal Communication in Classroom Interaction and Its Role in Italian Foreign Language Teaching and Learning" Languages 9, no. 5: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050164

APA StyleDiadori, P. (2024). Nonverbal Communication in Classroom Interaction and Its Role in Italian Foreign Language Teaching and Learning. Languages, 9(5), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050164