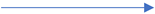

Metaphorical Personal Names in Mabia Languages of West Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Studies on Metaphorical Personal Names

3. Theoretical Framework

I have invested a lot of time in heryou do not use time profitably.

4. Data Collection and Research Methodology

5. Data Presentation and Analyses

5.1. EXPERIENCES ARE PERSONAL NAMES

5.2. BELIEF SYSTEMS AS PERSONAL NAMES

5.3. DEATH WEAPONS ARE PERSONAL NAMES

5.4. FLORA AND FAUNA NAMES ARE PERSONAL NAMES

5.4.1. Fauna Names as Personal Names

5.4.2. Flora Names as Personal Names

5.5. NAMES OF DEITIES ARE PERSONAL NAMES

6. Discussion

| (1) Ɓasɩmbεnsɔ ‘Don’t Maltreat Me’ | |

Source Domain Target Domain Target Domain | |

| Name giver | ‘Possible experiencer of maltreatment’ |

| Name-bearer; admonisher/carrier of message | Every listener or mentioner of the name is reminded to desist from maltreating the name-bearer, giver or every other potential victim of such an act. |

| Name | Historical oral account of the past experience of an individual or group of people. |

| (2) Ati’ewin ‘I Depend on God’. | |

Source Domain Target Domain Target Domain | |

| Name-giver | The name informs everyone of the name-giver’s belief in God. |

| Name-bearer; admonisher/carrier of message | Iconic figure who reminds everyone; mentioner or hearer of the name that the bearer and the giver believe in a Supreme Being. |

| Name | The name is an expression of a strong belief in God. It may be given to symbolise the difficulty the name-giver may have gone through or is going through but the person remains resolute based on his/her belief in God. |

| (3) Bije ‘They Do Not Want’ | |

Source Domain Target Domain Target Domain | |

| Name-giver | Expresses rejection of the child. |

| Name-bearer; admonisher/carrier of message | Every listener or mentioner of the name recognises the bearer as a survivor whose parents have suffered several neonatal deaths of their babies. The bearer is also identified as having survived because death also rejected him/her. |

| Name | Historical oral account of the past experience of parents of the name-bearer. |

| (4) Atiig ‘Tree’ | |

Source Domain Target Domain Target Domain | |

| Name-giver | Expression of name-giver’s reverence to the tree, or to carry a message in relation to the tree that may be known to the giver and the immediate family. |

| Name-bearer; admonisher/carrier of message | Every listener or mentioner of the name recognises the bearer as having been born under or close to a tree or the bearer may have been named after a tree because the parents want to show their reverence to the tree. |

| Name | Historical oral account of the location of birth of the bearer and/or family reverence to the tree. |

| (5) Name: Kipo ‘A Powerful Shrine Noted for Helping Barren Women’ | |

Source Domain Target Domain Target Domain | |

| Name-giver | Initiation of the bearer into the worship of the shrine. Expression of name-giver’s reverence for the shrine. |

| Name-bearer; admonisher/carrier of message | Every listener or mentioner of the name recognises the bearer as someone who was conceived with spiritual support from this shrine. The name-bearer is also initiated into the service of the shrine. |

| Name | Historical oral account of how the name-bearer was ‘conceived’. |

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In Kusaal the prefix A- turns the faunym baa ‘dog’ into a personal name. Thus, whilst baa is ‘dog’ and Abaa is a human being named after a dog. Similarly, whilst Ndeog is chameleon Andeog is a person named after the chameleon. |

References

- Abubakari, Hasiyatu. 2018. Aspects of Kusaal Grammar: The Syntax-Information Structure Interface. Ph.D. thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakari, Hasiyatu. 2020. Personal names in Kusaal: A sociolinguistic analysis. Lanuage and Communication 75: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Hasiyatu. 2021. Noun Class System of Kusaal. Studies in African Linguistics 50: 116–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Hasiyatu. 2022. A Grammar of Kusaal: An Introduction to the Structure of a Mabia Language. Accra: Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, Unpublished monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakari, Hasiyatu, A. Samuel Issah, O. Samuel Acheampong, D. Moses Luri, and N. John Napari. 2023. Mabia languages and cultures expressed through personal names. International Journal of Language and Culture 10: 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, Kofi. 2006. The sociolinguistics of Akan personal names. Nordic Journal African Studies 15: 206–34. [Google Scholar]

- Algeo, John. 2010. Is a theory of names possible? Names 58: 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, John, and Katie Algeo. 2000. Onomastics as an interdisciplinary study. Names 48: 265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awedoba, Albert K. 1996. Kasem Nominal Genders and. Names. Research Review 12: 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- Awedoba, Albert K. 2000. An Introduction to Kasena Society and Culture through Their Proverbs. New York: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Bisilki, Abraham Kwesi. 2018. A study of personal names among the Bikpakpaam (the Konkomba) of Ghana: The linguistics, typology and paradigm shifts. Language Sciences 66: 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisilki, Abraham Kwesi, and Kofi Yakpo. 2021. ‘The heart has caught me’: Anger metaphors in Likpakpaln (Konkomba). Sociolinguistic Studies 15: 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodomo, Adams. 2020. Mabia: Its etymological genesis, geographical spread, and some salient genetic features. In Handbook of the Mabia Languages of West Africa. Edited by Bodomo Adams, Abubakari Hasiyatu and Issah A. Samuel. Glienicke: Galda Verlag, pp. 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, William. 2003. What is a name? Reflections on onomastics. Language and Linguistics 4: 669–81. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William, and D. Alan Cruse. 2004. Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dakubu, Esther Mary Kropp. 2000. Personal names of the Dagomba. Research Review New Series 6: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fortes, Meyer. 1955. Names among the Talensi of the Gold Coast. In Afrikanistische Studien, Diedrich Westermann Zuin 80. Edited by Johannes Lukas. Geburtstag Gewidment. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, pp. 337–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gariba, Abudu Chieminah. 2009. Sissala Names and Meanings. Tumu: Chieminah Abudu Gariba/SHF. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts, Dirk. 2010. Theories of Lexical Semantics. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Karpenko, Elena Yu. 2006. Cognitive Onomastics as a Direction of Studying Proper Names. Doctoral dissertation, Odesa I. I. Mechnikov National University, Odesa, Ukraine. Unpublished. (In Ukrainian). [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2002. Metaphor: A Practical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, Franz. 1978. Übergangstriten im Wandel. Henschäftlarn: Kommissionsverlag Klause Renner. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1993. The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor. In Metaphor and Thought, 2nd ed. Edited by Andrew Ortony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Turner. 1989. More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, Eyo. 2020. Name this child: Religious identity and ideology in Tiv personal names. Names, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musah, Anthony Agoswin, and Aweaka Sandow Atibiri. 2020. Metaphors of Death in Kusaal. Journal of West African Languages 47: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, Samuel Gyasi. 1998a. Akan Death-Prevention Names: A Pragmatic and Structural Analysis. Names 46: 163–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, Samuel Gyasi. 1998b. Hypocoristic day-names. Multilingua 16: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Richards, Ivor Armstrong. 1936. The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robustova, V. V. 2014. Towards cognitive onomastics. Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta 1: 41–49. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Umar, Najirah, Yuyun Wabula, and Hazriani Zainuddin. 2020. Personal Popular Name Identification Through Twitter Data. International Journal of Advanced Trends in Computer Science and Engineering 9: 8184–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, Lionel. 2005a. Class-inclusion and correspondence models as discourse types: A framework for approaching metaphorical discourse. Language in Society 34: 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, Lionel. 2005b. Constructing the source: Metaphor as a discourse strategy. Discourse Studies 7: 363–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, Lionel. 2006. Proper names and the theory of metaphor. Journal of Linguistics 42: 355–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakub, Mohammed. 2023. “You can only see their teeth”: A pragma-linguistic analysis of allusive personal names among the Nzema of Ghana. Nomina Africana 37: 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dagbani | Kusaal | Likpakpaaln | Sisaali |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dinnani ‘it is possible’ | Amɔrbɔ ‘What do you have?’ | Mananjɔ ‘I don’t hate my friend’ | Ɓasɩmbεnsɔ ‘don’t maltreat me’ |

| Nniŋdini ‘What is my offence?’ | Abangiba ‘I know them’ | Torbi ‘The reconciler has spoilt it’ | chεwɩɩrɩtɔɔ ‘angry world’ |

| Chentiwuni ‘leave to God’ | Apeligiba ‘God has exposed them’ | Binantɔb ‘They hate each other.’ | Ɓasɩn-aɓee ‘what did they asked me to do’ |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dagbani | Bεcheti | ‘They have left us’ |

| Kusaal | Adi’ebɔ | ‘What have you gained?’ |

| Likpakpaaln | N-neebini | ‘I am in their midst’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | Ɓasɩn-abee | ‘What did they asked me to do’ |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dagbani | Salpawuni | ‘Human being is not God’ |

| Kusaal | Azing | ‘Fish’ |

| Likpakpaaln | Udinaanu | ‘The enemy does not smell’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | Harɩwanawɩε | ‘Those behind see things’ |

| Dagbani | Kusaal | Likpakpaaln | Sisaali |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wumpini ‘God’s gift’ | Abewin ‘It is with God’ | Uwumbɔrakumi ‘God has not killed me’ | Luri/Haluri ‘medicine spirit’ |

| Tɔŋpaɣa ‘a child gifted by this deity (tɔŋ) who is a female’ | Abʋgʋr ‘deity’ | Uwumbɔrkan ‘God has seen’ | Javuno ‘deity’ |

| Buɣili ‘shrine’ | Agɔswin ‘Looking to God’ | Uwumbɔrapuan ‘God’s power’ | Lopawɩɩsɩ ‘leave to God’ |

| Jaagbo ‘deity’ | Ati’ewin ‘I depend on God.’ | Uwumbɔradak ‘God does not think so’ | Nala/Hanala ‘Shrine’ |

| Kɔŋbo ‘what don’t I have?’ | Abewin ‘It is with God/I leave it with God’ | Ubinche ‘He (God) is with me’ | Fuo/Hafuo ‘river spirit’ |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dagbani | Ŋebuni | ‘Name of a deity’ |

| Kusaal | Awin | ‘God’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | Bawɩɩsɩ/Hawɩɩsɩ | ‘God’ |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dagbani | Busaɣiri | ‘God alone is enough’ |

| Kusaal | Awingur | ‘God preserves/protects’ |

| Likpakpaaln | Uwumbɔrja | ‘God defends/fights’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | Wɩɩsɩwero | ‘God is good’ |

| Dagbani | Kusaal | Likpakpaanl | Sɩsaalɩ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sando ‘male stranger/traveller’ | Akʋmbaŋ ‘will not know’ | Nkunsiimi ‘Death has insulted me’ | Mυɔsɩ ‘wickid person’ |

| Modoo(M)/Mopaɣa(F) ‘Moshi man/Woman’ | Abindau/Abinpu’a Bimoba man/Bimoba woman | Taakicha ‘Do not go again’ | N-yɔɔsυυ ‘I bought death’ |

| Fulaani ‘Fulaani man/woman’ | Moja/Mopii man/Bimoba woman | Sʋʋneŋ ‘Death has seen me’ |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dagbani | Kumbicheso | ‘death does not leave out anyone’ |

| Kusaal | Akpiid | ‘Death’ |

| Likpakpaln | Nkumbaan | ‘The same death’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | Nkasʋʋ | ‘I am death’ |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Likpakpaln | Nkumfami | ‘Death has hit me’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | Sʋʋtaŋ | ‘will death spare me’ |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dagbani | Bije | ‘They do not want’ |

| Kusaal | Azi | ‘Unknown’ |

| Likpakpaln | Maanyi | ‘I don’t know’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | N-yɩrɩpa | ‘I will not name you’ |

| Dagbani | Kusaal | Likpakpaanl | Sɩsaalɩ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tia/Tidoo/Tipaɣa ‘Names after a tree’ | Atiig ‘Names after a tree’ | Ujankpa ‘Fish’ | Tɩε ‘Named after a tree spirit’ |

| Jaŋgbariga ‘Mouse’ | Anya’ar ‘Named after the root of a tree’ | Ukpiin ‘Horn used as a trumpet especially during warfare/funerals’ | Bapaal/Hapaal Named after a mountain |

| Duunga ‘Mosquito’ | Alaal ‘Named after a doormouse’ | Umeen ‘Turtle’ | Diiwie/Hadiiwie ‘Named after a bird’ |

| Baa napɔŋ ‘dog leg’ | Abaa ‘Named after a dog’ | Ukaa ‘Hawk’ | Kachu ‘Hawk’ |

| Garinga ‘Snake’ | Andeog ‘Named after a chameleon’ | Salma ‘the precious mineral ‘Gold’ | Anwon ‘lion’ |

| Name | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Aniig | ‘Named after a cow’ The tail of the cow is a totemic symbol of the Na’aram clan among the Kusaas (Abubakari 2021, pp. 132–33) |

| Awaaf | ‘Named after a snake’ The Python is a totemic animal of Tensʋƞ clan among the Kusaas (Abubakari 2021, pp. 132–33) |

| Awief | ‘Named after a horse’ The horse is a totemic animal of the Nabidib clan among the Kusaas (Abubakari 2021, pp. 132–33) |

| Names from Kusaal | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Adoonr | ‘named after the African locust bean tree’ |

| Atiig | ‘Named after a tree’ |

| Dagbani | Kusaal | Likpakpaanl | Sisaali |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wumbee ‘Means God’s leg. Every house has God’s leg they worship’ | Atʋbig Tʋbig is the name of a shrine that protects a house and can be used against your enemies. | Kipo ‘A powerful shrine noted for helping barren women’ | Gbεnε/Hagbεnε chameleon spirit/a guardian shine |

| Buɣili ‘shrine’ | Abʋgʋr ‘deity’ | Tingbaki ‘The earth goddess has accepted me’ | Luri Hunting/healing/war spirit |

| ŋmambuɣu ‘calabash’. | Awin ‘god’ | ‘Liwaal’ ‘Shrine/god’ | Veni/Haveni family deity Nala/Hanala initiated into a deity |

| Laasiche ‘deity’ | Azʋʋr ‘tail/tail god’ | Chito Children with this name are believed to have been given to the parents by ‘Chito’ goddess. | Tɩɩwυ/Hatɩɩwυ magic spirit family deity |

| Buɣulana ‘A name given to the one who is in charge of the shrine and other deities that belongs to the community’ | Anwεliŋ Nwεliŋ is a shrine spirit. It is believed to have powers/charms that confuse or attack the enemy. | Krupɔ Named after the shrine ‘Krupɔ’ | Batɔŋ/Hatɔŋ deity/god |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dagbani | Wumbee | ‘Means God’s leg’ | Every house has God’s leg they worship. This name does not imply that the bearer is ‘God’s leg’ but rather that the bearer is named after the deity which is supposed to provide some protection for the baby. |

| Kusaal | Asataŋ | ‘Sataŋ’ is a blacksmith’s anvil-stone’ | It is used as a personal or shrine god. Similarly, the Kusaas give this name when it symbolically means that the deity is the bearer’s personal spirit and protector. |

| Likpakpaln | Kundi | ‘A shrine that is believed to protect and also give children’. | This name may suggest that the name-bearer is dedicated to this shrine. |

| Language | Personal Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Kusaal | Zan’ar | ‘A traditional iron hammer used by the blacksmith’ |

| Sɩsaalɩ | Luki or Balu/Haluki or Halu | ‘blacksmith god’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abubakari, H.; Issah, S.A. Metaphorical Personal Names in Mabia Languages of West Africa. Languages 2024, 9, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050163

Abubakari H, Issah SA. Metaphorical Personal Names in Mabia Languages of West Africa. Languages. 2024; 9(5):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050163

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbubakari, Hasiyatu, and Samuel Alhassan Issah. 2024. "Metaphorical Personal Names in Mabia Languages of West Africa" Languages 9, no. 5: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050163

APA StyleAbubakari, H., & Issah, S. A. (2024). Metaphorical Personal Names in Mabia Languages of West Africa. Languages, 9(5), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050163