On the Functional Convergence of Pragmatic Markers in Arizona Spanish

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Y, no, ahora están muy mal los chamacos. (CESA031)‘And, yeah, now the kids are really bad’.1

- (2)

- Sigue el Spring Fling hasta el lunes, ¿qué no? (CESA073)‘The Spring Fling is going until Monday, right?’

- (3)

- You know, eso era lo que me gustaba a mí. (CESA013)‘You know, that’s what I liked’.

- (4)

- Y pues, sabes qué, estuvo mal de mi parte haberme enojado por eso. (CESA021)‘And well, you know, it was bad on my part to have gotten mad for that’.

- (i)

- What discourse functions (shared or otherwise) do different subtypes of PMs, including tags and DMs, fulfill in Arizona Spanish?

- (ii)

- Following Pichler (2013), among others (Kluge 2011; Palacios Martínez 2014; Schleef and Mackay 2022), are certain discourse functions correlated with certain syntactic positions in Arizona Spanish?

- (iii)

- What role, if any, does the incoming English loan you know have in conditioning codeswitching behavior in Arizona Spanish?

2. Pragmatic Markers

2.1. Pragmatic Markers: A Synopsis

2.2. Tag “Questions”: A Misnomer?

2.3. Pragmatic Systems in Contact

Due to their interconnected grammars, the bilingual speaker draws from a greater number of linguistic features than their monolingual counterparts (Otheguy et al. 2015), being able to deploy a number of different pragmatic resources at any given time. As borrowings become more frequent, they may lead to systematic changes, through filling in functional gaps, acquiring new functions, or bringing functions over from the donor language (Andersen et al. 2017; Bybee 2015).“…contact is seen not as an external factor that triggers change, but as one that is internal to the processing and use of language itself in the multilingual speaker’s repertoire of linguistic structures. Accordingly, speakers are seen as creative communicators who draw on their entire repertoire in order to make communication more efficient, and the functional value of linguistic categories is a factor that plays a role in the speaker’s ability to select structures within their repertoire”.(p. 74)

3. Methodology

3.1. The Data: Corpus del Español en el Sur de Arizona

3.2. Coding

- Information/confirmation-seeking: seeks a (usually affirmative) response.

- (5)

- Sigue el Spring Fling hasta el lunes, ¿qué no? (CESA073)‘The Spring Fling is going until Monday, right?’

- Action-seeking: seeks an action from an interlocutor, real or imagined, through commands/offers.

- (6)

- Todos juntos vamos a cambiar todo, ¿no? (CESA052)‘We’re going to change everything together, aren’t we?’

- Attitudinal/stance-taking: provides a subjective evaluation or position in relation to the topic.

- (7)

- You know, eso era lo que me gustaba a mí. (CESA013)‘You know, that’s what I liked’.

- Challenging/confrontation: lends illocutionary force to a negative speech act on the part of the speaker.

- (8)

- Pero, you know, si no te adaptas, pues… (CESA037)‘But, you know, if you don’t adapt, well…’

- Focusing: highlights or re-emphasizes a specific element within the discourse.

- (9)

- Cuando XY se estaba criando, tú sabes, XY tiene autism… (CESA016)‘When XY was growing up, you know, XY has autism…’

- Phatic/alignment: ensures that an interlocutor is following the stream of thought (differentiated from information/confirmation-seeking above by not needing a response).

- (10)

- Dices que es más informal, ¿no?, más, bueno sí… (CESA052)You say it’s more informal, right, more, well yeah…

- Discursive: brackets or structures speech itself.

- (11)

- Jamás los vas a conocer, al saber que, you know, que hay un niño. (CESA037)‘You’re never gonna know them, to know that, you know, that there’s a kid’.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

- Addressee-oriented

- (12)

- Los mexicanos siempre usan vestido blanco, ¿no? (CESA025)‘Mexicans always wear white dresses, right?’

- Speaker-oriented

- (13)

- Y, no, ahora están muy mal los chamacos. (CESA031)‘And, yeah, now the kids are really bad’.

- Exchange-oriented

- (14)

- Siempre era ir con familia, ¿no?, a festejar. (CESA044)‘It was always going with family, right, to celebrate’.

4.1. Discourse Function, Revisited

4.2. You Know and Language Environment

- (15)

- I was happy, I was content with myself, you know, just either playing or whatever. (CESA076)

- (16)

- Pues la fiesta después, you know, like the after party. (CESA049)‘Well the party after, you know, like the after party’.

- (17)

- Like somebody who only speaks Spanish is trying to find something or, you know, alguien que se ayuda, and nobody speaks Spanish. (CESA076)‘Like somebody who only speaks Spanish is trying to find something or, you know, somebody that can help, and nobody speaks Spanish’.

- (18)

- Me gusta la cultura y soy, you know, rodeado con la cultura. (CESA027)‘I like the culture and I’m, you know, surrounded with the culture’.

- (19)

- You know, sabes qué, tengo una sobrina, la hija de mi tía… (CESA015)‘You know, you know, I have a niece, the daughter of my aunt…’

5. Conclusions and Future Study

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | All translations are my own. |

| 2 | “[Marcadores de discurso] son unidades lingüísticas invariables, no ejercen una función sintáctica en el marco de la predicación oracional (o sea, están fuera de la sintaxis oracional) y poseen un propósito en el discurso: el de guiar las inferencias que se realizan en la comunicación. O sea, señalan las relaciones que existen entre unidades del discurso” (Portolés Lázaro 1998, pp. 25–26). |

| 3 | We thank one reviewer for observing that whether we account for PM development under the framework of grammaticalization or not ultimately does not change the significance of our findings. |

| 4 | While other factors were coded for, including intonation, anchor mood, and polarity, they are outside the scope of the current work, and will not be discussed further. |

References

- Aaron, Jessi. 2004. “So respetamos un tradición del uno al otro”—So and entonces in new mexican bilingual discourse. Spanish in Context 1: 161–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, Jessi, and José Hernández. 2007. Quantitative evidence for contact-induced accommodation: Shifts in /s/ reduction patterns in Salvadoran Spanish in Houston. In Spanish in Contact: Policy, Social and Linguistic Inquiries. Edited by Kim Potowski and Richard Cameron. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 329–43. [Google Scholar]

- Allerton, D. J. 2009. Tag questions. In One Language, Two Grammars: Differences between British and American English. Edited by Günter Rohdenburg and Julia Schlüter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 306–23. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Gisle. 2022. What governs speakers’ choices of borrowed vs. domestic variants in discourse-pragmatic variables. In Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change: Theory, Innovations, Contact. Edited by Elizabeth Peterson, Turo Hiltunen and Joseph Kern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 251–71. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Gisle, Cristiano Gino Furiassi, and Biljana Mišić Ilić. 2017. The pragmatic turn in studies of linguistic borrowing. Journal of Pragmatics 113: 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenberg, Heidi, and Óscar Loureda Lamas. 2011. Marcadores del Discurso: De la Descripción a la Definición. Madrid: Iberoamericana Editorial Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2011. Usage-based theory and grammaticalization. In The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization. Edited by Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2015. Language Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana. 2012-. Corpus del Español en el Sur de Arizona (CESA). Tucson: University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana, and Joseph Kern. 2019. The permeability of tag questions in a language contact situation: The case of Spanish-Portuguese bilinguals. Pragmatics 29: 463–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, Claire. 2021. Mechanisms of grammaticalization in the variation of negative question tags. Journal of English Linguistics 49: 419–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, Steven, and Chase Raymond. 2021. You know as invoking alignment: A generic resource for emerging problems of understanding and affiliation. Journal of Pragmatics 182: 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crible, Ludivine, and Liesbeth Degand. 2019. Domains and Functions: A Two-Dimensional Account of Discourse Markers. Discours 24: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, William. 2022. Morphosyntax: Constructions of the World’s Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcy, Alexandra. 2005. Like: Syntax and Development. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Degand, Liesbeth, Zoé Broisson, Ludivine Crible, and Karolina Grzech. 2022. Cross-linguistic variation in spoken discourse markers. In Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change: Theory, Innovations, Contact. Edited by Elizabeth Peterson, Turo Hiltunen and Joseph Kern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, Derek, and Sali Tagliamonte. 2016. Innovation, right? change, you know? utterance-final tags in Canadian English. In Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change in English: New Methods and Insights. Edited by Heike Pichler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 86–112. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza, Sandra. 2017. /s/ Aspiration in Ciudad Juárez and Speech Accommodation. Master’s thesis, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- García Vizcaíno, María José. 2005. El uso de los apéndices modalizadores ¿no? y ¿eh? en español peninsular. In Selected Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Lotfi Sayahi and Maurice Westmoreland. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gazdik, Anna. 2022. On the prosodic realization of Spanish ¿no?—Tags from a pragmatic perspective. Isogloss 8: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez González, María de los Ángeles. 2012. The question of tag questions in English and Spanish. In Encoding the Past, Decoding the Future: Corpora in the 21st Century. Edited by Isabel Moskowich and Begoña Crespo. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press, pp. 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez González, María de los Ángeles. 2014. Canonical tag questions in English, Spanish and Portuguese. Languages in Contrast 14: 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Daniel. 2009. Getting off the goldvarb standard: Introducing rbrul for mixed-effects variable rule analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Daniel. 2023. Rbrul (version 4.2.2). Software. Available online: http://www.danielezrajohnson.com/rbrul.html (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Kern, Joseph. 2019. Like in English and como, como que, and like in Spanish in the speech of Southern Arizona bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism 24: 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimps, Ditte, Kristin Davidse, and Bert Cornillie. 2014a. A speech function analysis of tag questions in British English spontaneous dialogue. Journal of Pragmatics 66: 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimps, Ditte, Kristin Davidse, and Bert Cornillie. 2014b. The speech functions of tag questions and their properties: A comparison of their distribution in colt and llc. In Corpus Interrogation and Grammatical Patterns. Edited by Kristin Davidse, Caroline Gentens, Lobke Ghesquière and Lieven Vandelanotte. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 321–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, Bettina. 2011. Camino de un marcador del discurso: Una comparación del español ¿sabes? con el francés tu sais y el inglés you know. In Marcadores del Discurso: De la Descripción a la Definición. Edited by Heidi Aschenberg and Óscar Loureda Lamas. Madrid: Iberoamericana Editorial Vervuert, pp. 305–41. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Zorraquino, María, and José Portolés Lázaro. 1999. Los marcadores del discurso. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Real Academia Española, vol. 3, pp. 4051–213. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2011. Introducing Sociolinguistics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, Isabel. 2005. La moda del ¿sabes? en madrid: Un análisis sociolingüístico. In Filología y Lingüística: Estudios Ofrecidos a Antonio Quilis. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas—Universidad de Valladolid, vol. 1, pp. 1045–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo, Francisco. 2006. Movement towards discourse is not grammaticalization: The evolution of claro from adjective to discourse particle in spoken Spanish. In Selected Proceedings of the 9th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Nuria Sagarra and Almeida Toribio. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Press, pp. 308–19. [Google Scholar]

- Onodera, Noriko. 2011. The grammaticalization of discourse markers. In The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization. Edited by Bernd Heine and Heiko Narog. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 614–24. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Martínez, Ignacio. 2014. Variation, development and pragmatic uses of innit in the language of British adults and teenagers. English Language and Linguistics 19: 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, Heike. 2013. Structure of Discourse-Pragmatic Variation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, Heike. 2021. Grammaticalization and language contact in a discourse-pragmatic change in progress: The spread of innit in London English. Language in Society 50: 723–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en español: Towards a typology of code-switching. Linguistics 18: 581–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolés Lázaro, José. 1998. Marcadores del discurso. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Said-Mohand, Aixa. 2007. Aproximación sociolingüística del marcador del discurso tú sabes en el habla de jóvenes bilingües estadounidenses. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 26: 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sankoff, Gillian, Pierrette Thibault, Naomi Nagy, Hélène Blondeau, Marie-Odile Fonollosa, and Lucie Gagnon. 1997. Variation in the use of discourse markers in a language contact situation. Language Variation and Change 9: 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987. Discourse Markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schleef, Erik, and Bradley Mackay. 2022. Evaluation of pragmatic markers: The case of you know. In Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change: Theory, Innovations, Contact. Edited by Elizabeth Peterson, Turo Hiltunen and Joseph Kern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 40–60. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen, and Andrés Enrique-Arias. 2017. Sociolingüística y pragmática del español. Washington: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2003. Comparative sociolinguistics. In The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Edited by J. K. Chambers, Peter Trudgill and Natalie Schilling-Estes. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 729–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2006. Analysing Sociolinguistic Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2012. Variationist Sociolinguistics: Change, Observation, Interpretation. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Lourdes, and Kim Potowski. 2008. A comparative study of bilingual discourse markers in Chicago Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Mexirican Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 12: 263–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, Elizabeth, and Richard Dasher. 2001. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, Catherine. 2005. Discourse Markers in Colombian Spanish: A Study in Polysemy. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Uclés Ramada, Gloria. 2020. Las funciones interactivas del marcador español ‘¿no?’ Las fronteras entre la atenuación y protección de la imagen. Revista Signos: Estudios de Lingüística 53: 790–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tags | DMs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no | qué no | you know | saber | Total | |

| Tokens | 370 | 13 | 147 | 61 | 591 |

| % | 63% | 2% | 25% | 10% | |

| Tags | DMs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no | qué no | you know | saber | Total | |

| Participants | 34 | 5 | 15 | 18 | 36 |

| % of Total | 94% | 14% | 42% | 50% | |

| Tags | DMs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 82 | 19 | 101 |

| 21% | 9% | 17% | |

| Medial | 127 | 167 | 294 |

| 33% | 80% | 50% | |

| Final | 174 | 22 | 196 |

| 45% | 11% | 33% | |

| Total | 383 | 208 | 591 |

| Broad Discourse Function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Addressee | Speaker | Exchange | Totals |

| Initial | 1 | 34 | 66 | 101 |

| 2% | 31.5% | 15% | ||

| Medial | 2 | 42 | 250 | 294 |

| 4% | 38% | 58% | ||

| Final | 45 | 35 | 116 | 196 |

| 94% | 31.5% | 27% | ||

| Totals | 48 | 111 | 432 | 591 |

| Tags | DMs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 200 | 177 | 377 |

| 52% | 85% | 64% | |

| Male | 183 | 31 | 214 |

| 48% | 15% | 36% | |

| Total | 383 | 208 | 591 |

| Tags | DMs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–19 years | 138 | 20 | 158 |

| 36% | 10% | 27% | |

| Birth/20+ years | 245 | 188 | 433 |

| 64% | 90% | 73% | |

| Total | 383 | 208 | 591 |

| Tags | DMs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addressee | 44 | 4 | 48 |

| 11% | 2% | 8% | |

| Speaker | 78 | 33 | 111 |

| 20% | 16% | 19% | |

| Exchange | 261 | 171 | 432 |

| 68% | 82% | 73% | |

| Total | 383 | 208 | 591 |

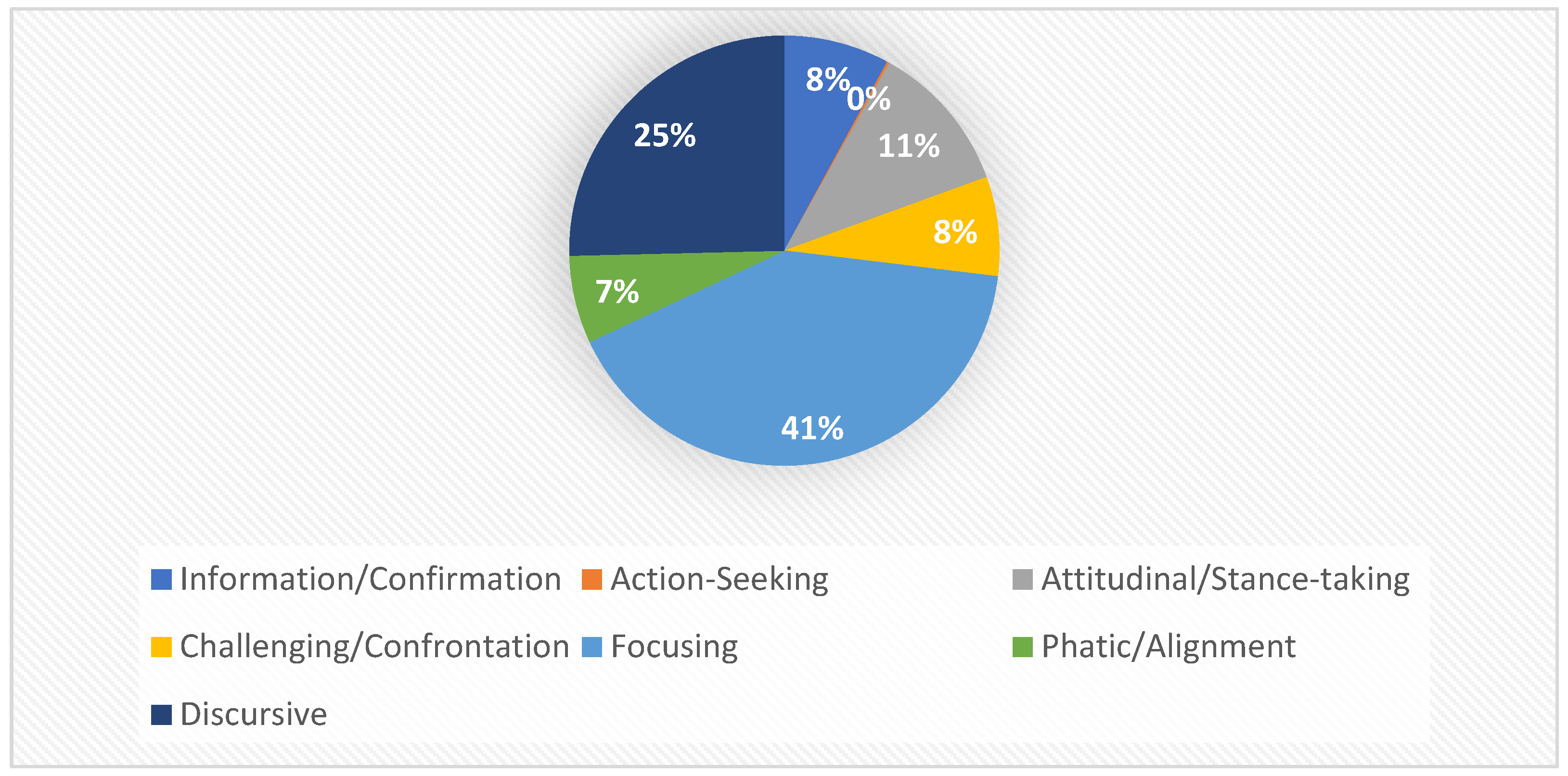

| Conducive | Non-Conducive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressee | Speaker | Exchange | |||||

| Information | Action | Attitudinal | Challenging | Focusing | Phatic | Discursive | |

| N | 47 | 1 | 67 | 44 | 243 | 39 | 150 |

| % | 8% | 0% | 11% | 7% | 41% | 7% | 25% |

| Spanish Variants | You Know | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English→English | 4 | 50 | 54 |

| 1% | 35% | 11% | |

| Spanish→English | 9 | 32 | 41 |

| 2% | 22% | 8% | |

| English→Spanish | 6 | 11 | 17 |

| 2% | 8% | 3% | |

| Spanish→Spanish | 345 | 50 | 395 |

| 95% | 35% | 78% | |

| Total | 364 | 143 | 507 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez, B.J. On the Functional Convergence of Pragmatic Markers in Arizona Spanish. Languages 2024, 9, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040148

Martínez BJ. On the Functional Convergence of Pragmatic Markers in Arizona Spanish. Languages. 2024; 9(4):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040148

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez, Brandon Joseph. 2024. "On the Functional Convergence of Pragmatic Markers in Arizona Spanish" Languages 9, no. 4: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040148

APA StyleMartínez, B. J. (2024). On the Functional Convergence of Pragmatic Markers in Arizona Spanish. Languages, 9(4), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040148