Abstract

This study explores the motivation and attitudes of heritage speakers (HSs) of Spanish, focusing on the influence of their social networks. Previous research highlighted variations in HS motivation, attributed to social, cultural, and contextual factors. The study investigates how HS communities shape motivation and attitudes towards learning the heritage language (HL). Employing personal network analysis, the research surveyed 26 Spanish HSs in a Spanish heritage language program. Results revealed that HS networks primarily consisted of emotionally close family members. Positive and negative factors within these networks, such as language support, confidence, shame, and expectations, significantly influenced HS motivation and attitudes. Language attitudes within the network positively impacted individual attitudes, indicating a process of internalizing shared values. The study emphasizes the importance of considering the context surrounding HSs and suggests that addressing language expectations and fostering language support in communities may positively transform perceptions of Spanish in the United States. The findings underscore the effectiveness of a personal network approach in recreating the external environment beyond the language classroom.

1. Introduction

We all belong to communities of connected individuals who influence our behaviors, inform our thoughts, and shape our attitudes (e.g., Stoessel 2002). Although these communities surely have a significant impact in the ways we use and experience language, our knowledge of and insight into them is limited by the research methods we use and the questions we ask. Differently from more traditional bilingualism research approaches that have examined isolated instances of language structures or linguistic behavior (e.g., Montrul 2004; Rothman 2007), in this study I seek to understand more holistically how our communities influence our linguistic experiences.

As an analytical tool, social network analysis (SNA) makes this possible. With SNA, the focus is on ecologically understanding the relationship(s) that exist(s) among the members of our community of interest, such as school groups, work colleagues, and families, and their dynamics, such as who you go to for advice or help during an emergency. Within the field of bilingualism, SNA is currently receiving increased attention, given its methodological and theoretical implications (e.g., Cuartero et al. 2023; Navarro et al. 2022; Tiv et al. 2020).

The goal of this study is to apply this perspective to investigate Spanish heritage speakers’ (HSs) attitudes and motivation to study Spanish in the context of the US. Within the field of heritage language (HL) studies, HSs are individuals who are raised in a home where a non-English language is spoken, who may speak or understand the HL and be, to some extent, bilingual in English and the HL (Valdés 2005). The acquisition of the HL is often associated with a strong family connection, and the language is an important part of the individual’s cultural identity. That said, because of its minoritized status, it is not uncommon for members of the family and of the community to discourage HSs from learning the language beyond what is acquired at home (e.g., Noels 2005; Noels et al. 2019). In Noels’ studies, some parents controlled their children’s autonomy by requiring them to study a language different to the HL because it was “more useful”. Considering this, an important question to ask, and one that is often posed by Spanish HL instructors is, why do some HSs enroll in language classes and others do not? In this study, I aim to shed some light on this issue by examining two interrelated areas: the students’ motivation to register in courses in which the HL is taught, as well as their attitudes towards the HL. Importantly, the tight relationship between these two constructs has long been recognized. Gardner and Lambert (1959), for example, proposed that, in order to have a predisposition to nourish language learning motivation, it is necessary to have a positive attitude towards that language. Additionally, motivation influences language learning. Conversely, when learning takes place, it tends to positively impact learners’ attitudes towards the target language, towards its speakers, and ultimately it encourages the students to continue learning the language (e.g., Ortega 2009).

Motivation is a human behavior guided by the drive to self-determine our actions and activities (Ortega 2009). As framed in the self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan 1985; Ryan and Deci 2017), the framework employed in this study, motivation is categorized as ranging from being initiated by choice and inherent enjoyment (intrinsic motivation) to being imposed by outside sources (extrinsic motivation). This framework proposes that external values and behaviors may be progressively adopted into one’s own, thus allowing individuals to function more successfully (Ortega 2009). As part of these external values, we find attitudes, which are a fundamental part of what is learnt through human socialization (Garrett et al. 2003) that index group status and membership and lead inter-group relations (Achugar and Pessoa 2009). Particularly, language attitudes refer to subjective evaluations of social varieties, and given their nature, language attitudes are socially defined, related to language ideologies, and often, implicit beliefs about language practices or varieties.

Previous research on HL motivation borrowed frameworks from the L2 field, which has been widely criticized (e.g., Ducar 2012; Oxford and Shearin 1994). Although Oxford and Shearin argue about the different learning circumstances found in second language settings versus foreign language settings, they importantly highlight that integration in the community may be more important for the students in the former classroom than the latter. Later, Ducar (2012) proposed that any model that aims to account for HSs’ motivation and attitudes must frame them from a socially informed perspective in order to understand HSs in the larger context. In other words, examining motivations and attitudes at the individual level is not enough: HSs must be examined together with their social networks (i.e., family, friends, and peers). To the best of my knowledge, to date, no motivational framework has incorporated HSs and their communities in the way that SNA does. Considering this, the overarching goal of this study is to explore and demonstrate the potential of SNA as a tool to deepen our understanding of HL learning, HL attitudes, and HL motivations. Specifically, I seek to investigate how the network measures and characteristics of a learner’s community can shed light on various aspects of HL motivation and attitudes.

Among other important advances, this study will further our understanding of HL communities and the impact they may have on college-aged HSs. Because the students who participated in this study are representative of subjects analyzed in related HL research, by using SNA to examine the relationships and interactions within their social circles, this study can create a social picture of our HSs’ communities and even provide insights into how social factors influence HL learning, HL maintenance, and HL loss outcomes. In turn, this increased understanding of the HL networks will have pedagogical implications, as educators will be informed as to the benefits of having the students engage with their own communities. For example, by identifying the relevant community factors that drive motivation to study the HL, SNA can also help to answer questions about the relevance of class content outside of the classroom, especially with the introduction of critical language awareness in Spanish HL programs. SNA can isolate which elements in the community promote positive or negative attitudes towards the heritage language and which can inform efforts to promote positive language attitudes and increase HL maintenance among speakers.

2. Social Personal Network Analysis

Simply put, SNA measures the composition of personal communities; that is, the connections between people and the settings to which these people belong. As a research instrument, it has been previously used in a number of fields, which include, but are not limited to, sociology and anthropology. Within SNA, personal social network analysis (PSNA)1 focuses on a person and their relationship to a set of people, which suits my purpose of studying the relationship between one person (here, HSs) and their community. PSNA “explores[s] the social environment and isolate[s] its effect on people, using the variation from one person to another to explain the variation in what we think the social environment predicts or affects” (McCarty et al. 2019, p. 2). PSNA focuses on the individual and their close and distant relationships, in order to operationalize social contexts and look at the direct and indirect effects of such contexts on the individual (McCarty et al. 2019). Due to this, I am able to isolate certain contexts (represented in network members) in HSs’ networks and operationalize them. For example, PSNA has been used to describe the role of social networks for support (both emotional and tangible), influence or contagion (knowledge, rumors, behaviors, and innovations), major life stressors, and daily life challenges. This research has also shown that social interactions can be both positive or negative, or helpful or harmful, and just as they can integrate individuals into a community, they can reject them (McCarty et al. 2019). To understand how members in the personal network interact, I review primary components of PSNA with definitions extracted from Perry et al. (2018).

2.1. Components of Personal Social Network Analysis

PSNA seeks to explain the connections between any set of individuals and the relationships among them. When creating a personal network, the respondent and central component of the personal network (“ego”) informs the researcher about the other members (“alters”), who may be family members, friends, or colleagues. Then, we ask the ego about their ties with alters, in order to extract information about frequency of contact, language of interaction, and duration of the relationship, among other things. From this information, we can extract compositional (demographics, function, and content) and structural data (network density and core–periphery measures) to explain the network. Visually, this is represented in an “ego network”, a “social network”, or a “personal network”, consisting of alters connected to an ego and ties among alters. The information that we elicit from the ego allows researchers to “embed individuals [egos] and their decisions, outcomes, and life chances in the larger social context of relationships, group membership, and community [alters]” (Perry et al. 2018, p. 3). These data can be used to explain or predict behaviors, trends, and other conducts. That is, PSNA lets us obtain information about how someone’s group membership explains certain actions (e.g., socialization), revealing distinct structural and compositional features that can be used as predictors for behavioral outcomes. In order to construct a PSNA study like the previous study described above, we would have to go through the following steps:

- Demographic information regarding gender, age, education, and so on, is collected from the ego.

- The ego lists a number of alters who perform a type of exchange, provide services, or provide emotional support or appraisal, depending on the research interest.

- The ego responds about each individual listed in the previous step; questions may regard their attitudes, opinions, and beliefs, as well as more tangible experiences (Emirbayer and Goodwin 1994). During the analysis, measures from this step and the first become compositional data that can be used as independent variables to predict other variables.

- The ego answers whether an alter knows another, and more questions about the relationship between them (e.g., closeness between them and language of interaction), which creates the structure of the ego community that will allow us to grasp measures of the network.

When we refer to the network structure and composition, we are talking about the patterns of connections between the nodes or units in a network. These patterns can be represented in different ways, such as adjacency matrix tables or network graphics. Once we have a clear understanding of the network’s structure and composition, we can use various measures or metrics to quantify different aspects of the network’s behavior and dynamics. A set of powerful measurements from the network are as follows (McCarty et al. 2019):

- Homophily is the tendency to have social relationships with people like oneself. Similarity is a powerful predictor of socialization, because personal networks tend to be homogeneous with regard to many sociodemographic, behavioral, and intrapersonal characteristics (McPherson et al. 2001). Homophily may be a consequence of social influence (i.e., a person is impacted by existing contacts), but also a result from social selection, choosing contacts who are already similar to oneself, as this similarity is preexistent to the connection to the other person (Kandel 1996).

- Network density represents the existing ties out of all the potential ties, given the number of alters. It is a measure of overall network cohesion based on alter connectedness: a percentage of ties that exists out of all possible ties, ranging from zero (no actor is connected) to one (every actor is connected to each other).

- Core–periphery differentiates a core, a central and dense group of alters with whom the ego has the strongest ties and highest frequency of interaction (e.g., friends and family), and a periphery, referring to sparsely linked alters with fewer connections to core alters that are less strong and frequent.

These measures can be used for research purposes, such as to understand the network’s resilience in unexpected events, the spread of information, or the role of specific groups in the ego’s life. For example, Figure 1 provides an illustrative example from Strawbridge (2020) of a personal network and the main elements used in its analysis, as follows:

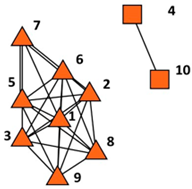

Figure 1.

Strawbridge’s (2020) social network graph from study abroad socialization: Anita. Graph key: circle = English native speaker; square = Spanish host family; diamond = Spanish peer.

In his doctoral dissertation, Strawbridge (2020) investigated how learning about network structure may inform bilingual development in study abroad programs. This work expands on Isabelli-García’s network research on study abroad students in Argentina (Isabelli-García 2006). Figure 1 shows Anita’s network, an American student in Spain. She reported the 17 alters with whom she contacted regularly in the host country. Two clusters are visible: one is a dense cluster in which every alter knows each other, because they are English native speakers in Anita’s Spanish class. The other cluster is the host family (n = 4), with the addition of a person who does not belong to the family but who may have friends in common with them, as well as with Anita. There is an isolated diamond representing a Spanish native speaker from her internship. Based on her responses about language use with each alter, roughly 75% of her communication was in English, despite being in a study abroad situation. Strawbridge gathered scores from Spanish proficiency tests (DELE, Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera) and elicited imitation tasks throughout the semester, and these tests showed that this participant did not improve her Spanish skills. Strawbridge’s study and, particularly this example, evidences the relevance of looking at structural and relational properties of personal networks in order to inform researchers about L2 proficiency development. For this participant, it seems that she did not take advantage of the study abroad context to improve her Spanish, since she mainly used English and contacted English speakers.

As presented, this research instrument uses the variation from one person’s social environment to another to explain its effect on them. Hence, PSNA is an adequate instrument to account for HL experiences, record societal values, and capture the linguistic, cultural, and societal implications of what it means to be a heritage speaker. So far, PSNA has been employed to examine a variety of issues in applied linguistics. For example, previous research in linguistics has explained the spread of dialectal features (Milroy and Milroy 1985), L1 shift by looking at personal networks from the home and the host country (Stoessel 2002; Wei 1995), second language identity development (Doucerain et al. 2015), and, as aforementioned, the progress of L2 proficiency in a study abroad context (Strawbridge 2020). These studies looked at how the strength of ties facilitated or impeded linguistic changes (Milroy and Milroy 1985), how secondary (periphery, less close) alters promoted home language maintenance (Stoessel 2002), and how high levels of interconnected alters predicted lower acculturative anxiety (Doucerain et al. 2015). This previous research was fruitful in explaining the relationship between network properties and language and language-related outcomes; this methodology could become key in providing answers to HL acquisition- and language-related issues (e.g., attitudes and insecurity).

2.2. Network Science and Heritage Languages

Stoessel’s (1998, 2002) work stands as an example of how network characteristics may inform L1 maintenance. Her purpose was to predict language maintenance and shift among migrants in the US. In order to achieve this, Stoessel gathered two networks: L1 networks in participants’ home countries (e.g., Greece, China and Peru) and L1 networks of 10 first-generation migrants in the USA. The network questionnaire included questions about alters’ relational characteristics (e.g., kin, friend, or neighbor), the type of support (e.g., borrowing money, advice, or childcare) between network alters and the ego, and the importance of alters to the ego (e.g., closeness). The questionnaire also included questions about the structure of the networks, such as size (alter number), density (connection among alters), and multiplexity (alters’ shared contexts). Stoessel divided participants into weak maintainers, for those who were prone to language shift, and strong maintainers, for those who would maintain the L1. Then, the home country network was categorized as primary, and the host country as secondary. Stoessel found that being in touch with L1 speakers (i.e., frequency of contact with alters in the home country network) in the home country (primary network) was a key factor for language maintenance. However, some participants relied on their L1 contacts in the host country for personal needs, which enabled them to speak their L1 in more contexts and made them “strong” maintainers. The approach in this study revealed the importance of looking at the structural and relational properties of bilinguals’ networks to learn about language maintenance. For HL bilingualism, this implies that it is possible to portray how HSs employ both languages in different situations, how often they do so, and with whom, among other issues.

Within this framework, previous related research on Spanish HL speakers in the US is very limited (see Gonzalez 2011; Velazquez 2013; Zalbidea et al. 2023). Gonzalez (2011) looked at Spanish HL maintenance in Arizona, to analyze how Spanish speakers use their language resources in oral interaction and the linguistic insecurity that may emerge from it. The application of PSNA allowed her to investigate the language maintenance tendencies of HSs of Spanish residents in a predominantly English community. Twenty-five participants from a Spanish HL (SHL) classroom filled out a linguistic insecurity questionnaire adapted from a foreign language anxiety scale (Horwitz et al. 1986), an oral proficiency assessment (from the same institution), a language use questionnaire (Rasi Gregorutti 2002, based on Kenji and D’andrea 1992), a network questionnaire (Stoessel 1998), and an interview. This last SN questionnaire included questions such as when alters would be contacted, language use with them, and self-confidence. Additionally, Gonzalez carried out an interview with some of the participants. She split participants in three groups depending on proficiency (lower, intermediate, and high), and categorized alters’ relations according to domain (neighborhood or family home), contact frequency (“stay-in-touch” questions), relationship, and language use (in each domain). After analyzing her data, she found that there was more linguistic self-confidence as the oral proficiency of the participants improved and as alters’ age in the family home increased (e.g., grandparents were present). Along the same lines, linguistic self-confidence increased as English use decreased. Similarly, linguistic insecurity decreased but Spanish proficiency increased when students reported having more Spanish-speaking contacts in the family and school domains. In sum, the author concluded that the networks of her participants correlated with HL use (speaking and listening) in relation to the levels of reported HL insecurity. Additionally, interview data revealed that participants in the study were not only evaluating their language abilities but also considering the abilities of others with whom they were interacting and the context in which the interaction was taking place. This finding highlights the fact that language abilities are not static but are influenced by various factors, including the communicative context, the speaker’s level of proficiency, and the perceived expectations of the interlocutors.

Relatedly, Velazquez (2013) focused on parental motivations, attitudes, and linguistic practices related to the intergenerational language transmission in a Spanish-speaking community. Her goal was to examine HL transmission to children depending on community linguistic ecology, given the centrality of family linguistic policies for the loss or maintenance of Spanish (Silva-Corvalán 1994; Tse 2001; Arriagada 2005; Worthy and Rodríguez-Galindo 2006). Velazquez quantified language attitudes (Karan 2000; Karan and Stalder 2000), ethnolinguistic vitality (Bourhis et al. 1981; Yagmur et al. 1999), family language use (Tse 2001), and the mother’s network of social interaction (L. Milroy 1987). Velazquez looked at multiplexity (actors bound by more than one tie to each other), cohesion of network structure (interconnectedness between network actors), strength of ties, and density (total ties divided by all possible ties). Her study showed that, in cases where the mother perceived that Spanish was an important component of their children’s identity and economic opportunities, there were more opportunities to develop oral and written competence. This analysis yielded potential opportunities for HL interaction and demonstrated attitudes toward Spanish use and maintenance in the family.

2.3. Heritage Language Motivations and Heritage Language Attitudes

In this study, I am mainly interested in the extrinsic motivations that guide HL learning and the language attitudes towards the HL, which have been often explained as being linked together (Gardner and Lambert 1972). In this last section, I will review how I analyzed HL learning motivations, HL attitudes, and an exemplary study researching the connections between HL motivation and attitudes through a network lens.

The self-determination theory emphasizes the influence of cultural and social factors on an individual’s sense of volition and initiative, ultimately affecting their well-being and performance (Ryan and Deci 2017). These factors contribute to a spectrum of motivation types, ranging from intrinsic motivation, stemming from personal desires, to external pressures to conform. Deci and Ryan (1985) define intrinsic motivation as the internal drive that leads individuals to engage in an activity solely for their interest and enjoyment, without any external rewards or control. Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, encompasses various subtypes that differ in the extent to which the activity is controlled by external factors. External regulation is a subtype characterized by performing an activity to obtain rewards or avoid punishments. Introjected regulation involves carrying out an activity to alleviate internal pressures like guilt or to boost one’s ego. Identified regulation refers to engaging in an activity for personally relevant reasons, where the regulation is embraced as one’s own. Integrated regulation is the final form of extrinsic motivation, where the learner feels that the learning process has become integrated into their identity and aligns with their broader life goals.

This continuum reflects how behaviors are internalized or integrated into one’s own sense of self (Dörnyei and Ushioda 2011). Internalization is described as a psychological process corresponding to the socialization process, where external behaviors become a part of oneself by adopting practices and values from the social context. Society, through this internalization, transmits behavioral regulations, attitudes, and values, both positive and negative, enabling individuals to maintain their connection to groups.

As mentioned above, an aspect that is socially distributed are language attitudes, which are reflections of locally constructed language ideologies and subjective evaluations of different social varieties (L. Milroy 2004; Leeman and Serafini 2016). Like attitudes towards other aspects, language attitudes are learned through socialization and are socially structured and structuring phenomena (Garrett et al. 2003, p. 5). Furthermore, they serve as indicators of group status and membership, influencing inter-group relations (Achugar and Pessoa 2009). Because of this, we can say that language attitudes are socially defined and connected to language ideologies, which are often implicit beliefs about language practices or varieties.

Language attitudes serve as ideological stances. These ideologies are often rooted in the belief that there is but one standard language that is built on the principles of correctness, authority, prestige, and legitimacy (J. Milroy 2007). All other versions of that same language (and consequently its speakers) are considered to be inferior. It is no coincidence that the standard variety is often the one spoken by the socially dominant and economically affluent group. And so, because in the context of the US (Spanish) HSs are minoritized and racialized subjects (e.g., Flores and Rosa 2015), their linguistic practices are also considered inferior and/or illegitimate (e.g., Beaudrie et al. 2021).

Zalbidea et al. (2023) conducted a study on the interconnections among psycho-affective variables for Spanish HL learning in higher education. They created a psychological network model, contrasting the association of language learning motivation and several variables: possible L2 selves2 (Dörnyei 2009) adapted for HSs, family influence (Taguchi et al. 2009), intended HL learning effort (Taguchi et al. 2009), HL achievement goal orientations (Papi and Khajavy 2021), HL enjoyment and anxiety (Dewaele et al. 2019), perceived classroom environment (Peng and Woodrow 2010), and critical language awareness (Beaudrie et al. 2019). The psychological network modeling (based on Costantini et al. 2015) helped to conceptualize variables as part of a complex system of interconnected elements that are associated between them and then used to establish predictions and multicollinearities among all of them (Epskamp et al. 2018). Participants (n = 209) filled out questionnaires for each variable, which were later correlated to each other. The most salient variables were the possible HL selves (ideal and ought-to), HL enjoyment, and intended HL learning effort. Of particular interest to my focus is the strong salient relationship found between the ought-to HL self and family influence, since it is likely that participants include family members in their alter list for my study. The results found that HSs who have a stronger sense of duty towards their heritage language and feel external pressure to study it in formal settings are more likely to have a performance-oriented goal, which seeks to demonstrate their ability in Spanish and outperforming their peers. In other words, these learners are more focused on achieving better results compared to others and demonstrating their language proficiency to gain recognition.

This is informative for my study because the ought-to L2 (here, HL) self is strongly correlated with introjected motivation (Takahashi and Im 2020), and this may inform my network analysis, even if I am only looking at alter connections and not psychological constructs. Secondly, critical language awareness seemed to be accompanied by a positive perception of the HL classroom, but also with lower familial pressure to study the HL in the formal context. According to their hypothesis, the pressure from family to prioritize studies in the HL contributed to the negative perceptions and beliefs about HL speech. This further reinforces the process of socialization of conventional language models. However, by fostering critical language awareness, HL learners can gain valuable resources to address linguistic discrimination and develop a better understanding of the legitimacy of language practices among bilingual individuals born in the US.

3. The Present Study

With this study I seek to further our understanding of the influence that HSs’ social networks may have on their attitudes and motivations towards their HL. To achieve this, I have formulated the following exploratory question:

To what extent are the language learning motivations and attitudes of HSs influenced by their social networks?

3.1. Setting

This study took place at a southeastern university in spring 2022. This public university is located in Florida, in a midsize city with a population of 134,661. This city is below the state level of percentage of Hispanic population (11.9% vs. 25.8%, US Census, 2019), and it is not comparable in population to other urban regions of the state, such as Miami or Florida. However, this university has experienced an increase in enrolment from students of Hispanic background, from 13.68% (6855) in 2010 to 20.8% (12,743) in 2021 (Student Information File, 2010–2021).

3.2. Participants

At the beginning of the semester, I recruited students from the SHL program by asking their instructors to distribute an email with information about the survey and visiting their classes. Twenty-six HSs agreed to participate in my study; six identified as men and twenty as women. Before completing the social network questionnaire, they filled out the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP; Birdsong et al. 2012). This language dominance instrument has been widely used in bilingualism studies because of its reliability and it has also been previously used in the SHL field (e.g., Amengual 2018; Calandruccio et al. 2021; Olson 2020). Although the BLP is not a background questionnaire per se, it was ultimately selected because it included questions about previous language use, self-measured proficiency, background history (i.e., education in Spanish, life abroad), and language attitude items, which could be useful in interpreting results. This initial survey showed that HSs acquired English and Spanish sequentially or simultaneously (e.g., Montrul 2016, 2018). Since their average age of acquisition of English was 1.65 (SD = 1.68) and 2.23 (SD = 4.42) for Spanish, they had fewer years of schooling or literacy in Spanish (e.g., Mancilla-Martínez 2018); they therefore felt less comfortable speaking in the HL than in the dominant language (e.g., Prada et al. 2020), and, in most cases, Spanish was spoken at home.

On average, participants had received 15 years (SD = 2) of education in English and 5.1 (SD = 4.1) in Spanish. Looking specifically at the question regarding the language spoken with family, participants reported having lived 17.8 (SD = 4.8) years speaking English with their families, and 17.4 (SD = 5.43) years speaking Spanish with their families, which can be taken as evidence of their bilingual upbringing before coming to the University of Florida. Looking at the percentages of language use, English was chosen with a frequency over 80% of the time as the language in the domains of friendship, school, and talking to oneself. Regarding the preferred language to communicate with family members, English was used 59.9% (SD = 30.43) and Spanish 40.5% (SD = 33.42); the high standard deviations may suggest some of these participants come from households which range from using Spanish only to English only, and both to differing degrees. It is possible that they use English to talk to their siblings and Spanish to talk to their parents and grandparents.

Additionally, participants were asked if they had taken SHL classes before: fifteen reported having no previous experience in the HL classroom, six reported having registered in one course before, and five reported having taken two courses. I also asked them about their family origin, which allowed me to extract the sociolinguistic generation3, heritage origin, and hometown.

3.3. Research Instruments

In addition to the BLP data, I collected information about the participants and their networks using a language motivation questionnaire (Noels 2005), and a language attitude questionnaire (Beaudrie et al. 2019), which lasted from 13 to 48 min4. Noels’ (2005) and Beaudrie et al.’s (2019) questionnaires were completed by students in their own time, but then they met me on a different day for an in-person session. During this session, participants completed a network survey based on Krenz and Losee (2022), which lasted from 21 to 39 min. In total, participants completed 385 questions.

- Language Motivation Questionnaire

To measure HSs’ language learning motivations, participants completed Noels’ (2005) questionnaire, adapted to Spanish HSs. This questionnaire included a total of 24 items: 3 items were rated as student amotivation (a lack of motivation), 12 items were rated as extrinsic motivations (a motivation source as external to oneself), and 9 items were rated as intrinsic motivations (motivation source as internal); I present a sample below. Importantly, although Noels et al.’s (2000) survey was originally designed with L2 learners in mind, a few years later, Noels (2005) modified it for German HSs in Canada. For the context of this study, the items were reworded for addressing the Hispanic community in Florida. This questionnaire was composed of questions with five-point Likert scales (one = completely disagree; five = completely agree).

- Amotivation: I can’t come to see why I study Spanish, and frankly, I don’t care.

- Extrinsic regulation: I study Spanish because it will help me get a better salary later on.

- Intrinsic regulation: I study Spanish for the pleasure I experience when surpassing myself in my heritage language.

- Language Attitude Questionnaire

- To measure language attitudes, I utilized Beaudrie et al.’s (2019) survey. As indicated in the literature section, in using this questionnaire (19 items), a higher index of critical language awareness (CLA) would represent more positive attitudes towards US Spanish (and dialectal variation), bilingualism (e.g., code switching), and language maintenance. Similar to the previous questionnaire, participants used a five-point Likert scale. I provide examples below.

- Dialectal variation: In my opinion, people should use standard Spanish to communicate all the time.

- Bilingualism: I would not code-switch in front of my teachers because they may think I am less intelligent.

- Language maintenance: After college, I would commit to reading, writing, speaking, and listening in Spanish every day to continue developing my language.

- Personal Network Survey

After participants completed the previous questionnaires, they continued with the PN survey, based on Krenz and Losee’s (2022) customizable personal network survey. Amounting to a total of 166 questions, this survey was organized in the following four sections:

- Ego attribute questions (four questions): participants answered about their age, gender, course, and previous course experience in the Spanish and Portuguese department.

- Alter naming list (one question): participants listed the names of 10 people to whom they were close, and preferably, with whom they spoke Spanish. The question read “Please write down the names or initials of people close to you. For instance, it can be five relatives and five friends (in UF, or not), four relatives and six friends, and so on. Preferably, these are people that speak Spanish to you, but if you can’t think of anybody else, please complete the other slots with English-speaking people that are close to you”. The number of alters per network was not random. Previous studies with HSs and PSNA elicited 10 alters to allow for concise answers and avoid cognitive exhaustion (e.g., Perry et al. 2018). Furthermore, 10 alters may give a representative approximation of the people who belong to the most intimate layers of participant networks. However, it should be noted that network size itself is not a relevant variable here, but rather closeness, density, and alter characteristics, which were elicited in the following step.

- Alter attribute questions (18 questions): First, participants were asked to provide information about individual alters in their social network (six questions: gender, age group, based on Krenz and Losee 2022). Some of these questions were adapted to fit my participants; for example, for domain, where alter and ego have met, it mentioned “University of Florida”. Secondly, to look at motivation, four items elicited information about the linguistic rapport between the participant (ego) and their social connections (alters). Participants considered a specific alter and their relationship when answering each item. These items were based on Noels et al. (2019): expectations and shame of language use, support to learn the HL, and ease to speak the HL.

- Language expectation: “This person” (alter’s name) expects me to speak Spanish.

- Language shame: I would feel ashamed if I could not speak Spanish to “this person” (alter’s name).

- Language support: “This person” (alter’s name) supports and encourages me to learn Spanish.

- Language confidence: I feel comfortable in my use of Spanish with “this person” (alter’s name).

Finally, five items from the attitude questionnaire (Beaudrie et al. 2019) were selected, based on their representation of each aspect of the questionnaire (language variation, language ideologies, Spanish in the US, bilingualism). In this last section, the ego responded in lieu of the alter; that is, they speculated what the alter would answer (prompt: “Do you think ALTER'S NAME agrees or disagrees with the following statements?”)- Language variation: I believe certain Spanish varieties are better than other.

- Language ideologies: People should use standard Spanish to communicate all the time.

- Spanish in the US: I believe Spanish-speaking Hispanics in the US don’t speak correct Spanish.

- Bilingualism: I believe growing up with both Spanish and English confuses children.

- Code-switching: I would try to avoid mixing Spanish and English in the same conversation as much as I can because it is not a proper way of speaking a language.

- Alter–alter connections (up to 135 questions): the last section inquired about alter–alter connections. It elicited the ties or connections between alters in order to see the participant’s network structure and density. Once participants confirmed the existence of an alter–alter connection, they were prompted with a question about alters’ closeness and language use among themselves. Depending on whether there was a connection between one alter and another, participants were prompted to answer another question about language use and emotional closeness between them.

All surveys were administered via Qualtrics. Reports were downloaded and read into RStudio, an instrument used for analyzing and visualizing quantitative data. In RStudio, I utilized the package tidyverse (Wickham et al. 2019) for the processing of data from the BLP questionnaire and the motivation and attitudes questionnaire. Then, the packages egor (Krenz et al. 2023) and igraph (Csárdi and Nepusz 2022) were used for the descriptive statistics and visualization of the social network survey.

4. Results

From the loaded data, I extracted informative measures that have been useful in previous research, such as compositional data, homophily, density, core–periphery division, and alters’ context (McCarty et al. 2019). First, for the compositional data (e.g., gender, age, and relation), I presented descriptive statistics in relative frequencies. Then, I presented the graphical visualization of participants’ networks. Subsequently, I compared alters after dividing them into groups, dependent on whether they were the same age and gender as the majority of egos (for homophily), emotional closeness (core–periphery), and depending on the context assigned by the ego (family, school, other). I carried out t-tests and analyses of variance (ANOVAs), looking for statistical differences between groups. Lastly, with multiple regression analyses, I explained which and how network variables contributed to ego’s language motivation and attitudes. Multiple regression analyses were successfully used in Doucerain et al. (2015) to investigate communication-related acculturative stress and general acculturative stress. Lastly, I implemented a simpler version of the psycho-affective model, based on Zalbidea et al. (2023), to understand the connections in alters’ subjective variables.

4.1. Composition

My participants were a sample of predominantly college age female5 students (n = 20, male n = 6) which may have predisposed the alter sample to be mainly female, as a 61% of alters (n = 159) were female. The most numerous alter age group was 19–30, at 42% (n = 109). The majority of alters were part of the family (59%) or school (30%). The participants' frequency of speaking to these alters had a more diverse set of answers: about 49% of alters were spoken to every day or several times per week, 31% were spoken to once a week or every two weeks, and 20% were spoken to only once a month. Lastly, not all alters held the same intimacy/proximity to alters; 32% were not close, and 68% were very close to participants.

4.2. Density

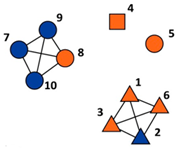

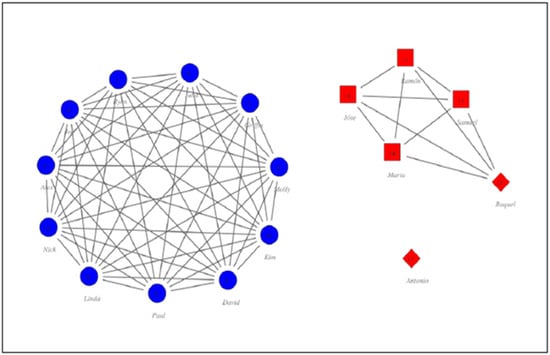

Density, one of the most basic and widely used structural metrics for social networks (McCarty et al. 2019), measures overall network cohesion or connectedness. In other words, it calculates how many alters know each other (existing ties). Density values are obtained calculating the percentage of ties that exist out of all possible ties. It ranges from zero to one: a lower density number represents a network in which only a few alters know each other, whereas a higher density number represents a network where more alters know each other. Each of my participants (n = 26) named 10 alters with whom they spoke Spanish (for a total of 260 alters) and the average density was 0.388 (SD = 0.116), with some networks presenting a 60% of alters connected (density = 0.6) and other presenting only 20% (density = 0.2). I present below three social networks, representing the densest network, the sparsest network, and the average network. The symbols represent whether an alter was family (triangle), school (square) or other (circle), and the colors represent the emotional core (orange) and periphery (blue). In the following networks, the only person that ties the four alters together is the ego; it is therefore not represented because it is visually uninformative, as it is connected to every alter (see more in McCarty et al. 2019).

As presented in Table 1, these examples represent different social pictures of my participants and the people with whom they spoke Spanish. The networks above portray one dense network in which nearly everybody knew each other (A), one with two connected clusters (B), and a sparse one (C). Looking at network density may help researchers understand how the structure is fostering alter subjective variables or egos’ motivation and attitudes. That said, correlation analyses between network density and alter variables did not yield any significant results. This may imply that, for certain affective variables such as expectations, shame, support, or confidence, density does not seem to be a determinant measure, although it can be useful to visualize the ego’s networks and provide an initial understanding of network analysis.

Table 1.

Network structures. Orange dots are core alters; blue dots are peripheric. The triangle is a symbol for family, the square for school, and the circle for others.

4.3. Homophily

As explained earlier, homophily is the tendency to have social relationships with people like oneself, based on similar ages, genders, and interests, among other factors, and it is a powerful predictor of socialization (McCarty et al. 2019). Because most of my participants were college female students, I selected the female alters of the 19–30 age group, which yielded a group of 71 alters (28% of all alters). Then, I compared the variables between the homophily sample and the remaining alters, using t-tests and Cohen D’s effect sizes.

Table 2 shows that this alter division yielded three factors that were significantly different between these groups, as confirmed by both moderate effect sizes and p-values. As can be seen, language expectation (t = 4.29, df = 138.07, p-value = 3.227 × 10−5; d = 0.56, CI = [0.288; 0.847]) and language shame (t = 4.56, df = 132.16, p-value = 1.143 × 10−5; d = 0.61, CI = [0.335; 0.895]) were lower in the homophily group than in the remaining alter group. Because of the lower language expectations, egos may have felt less compelled to use Spanish with people who were in the same age group, and fewer negative emotions if they used English or Spanglish9. Interestingly, language confidence (t = 2.813, df = 106.66, p-value = 0.0058; d = 0.42, CI = [0.149; 0.704]) was higher for the remaining alters than for those of the same age as my participants. Though apparently a contradiction when contrasted with the other two variables, it is likely that egos do not use Spanish with their peers as often as they do with their family. If they speak to their peers in Spanish, it may mostly be in an educational setting, which may heighten unease. Egos may be reporting here that they are expected to use Spanish likely with their family. Although Spanish may not be their preferred or dominant language, if they did not speak it with their close relatives, that could be taken as breaking an implicit family language policy.

Table 2.

Alter subjective variable means and standard deviation divided by homophily group. Average score and standard deviation for variables in each group over a scale of five (one = lowest; five = highest). Cohen D’s and p-values are provided. Statistical signification is boldened and moderate to large effect sizes are in italics.

4.4. Core and Periphery

Core–periphery refers to a network structure that examines the density and interconnectedness of alters. In this structure, certain alters create a densely connected core, while others, situated in the periphery, have fewer connections with both the core and among themselves. Generally, the core represents the group of contacts with whom the ego has the strongest emotional ties and, usually, the highest frequency of interaction, such as intimate friends. A way to visualize core and periphery is by splitting alters according to the ego’s given score of closeness10; in this case, alters evaluated as “extremely close” and “very close” were assigned to the core.

In Table 3, I present the means of alter variables as a general group, average network core (n = 178), and periphery (n = 82). Table 2 shows that only language support was significantly different between these groups, as confirmed by both moderate effect sizes and low p-values: t = 4.685, df = 121.67, p-value = 7.336 × 10−6; d = 0.70, CI = [0.432; 0.972]. Since the core group scored higher in language support, we can interpret this as the core providing more encouragement towards egos’ effort to learn and speak Spanish than the alters in the periphery. The remaining variables had high p-values and negligible effect sizes.

Table 3.

Alter subjective variable means and standard deviation divided by core and periphery. Average score and standard deviation for variables in each group over a scale of five (one = lowest; five = highest). Cohen D’s and p-values are provided. Statistical signification is boldened and moderate to large effect sizes are in italics.

4.5. Alters’ Context

Lastly, I looked at the division of participants per context. Although participants provided information about nine different contexts (family, significant other, college friends, non-college friends, neighbors, work, through someone else, common interests, and other), I grouped these categories into three: family (family and significant ones), school (college and non-college) and other (the remaining categories). Dividing participants in this way revealed which settings fostered or hindered language motivation and attitudes towards Spanish in the US, as reflected by critical language awareness.

As can be seen in Table 4, ANOVAs were performed to compare the effect of the context on each dependent variable (alter subjective variables). This revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in language expectation (F(2, 257) = 15.77, p = 3.48 × 10−7), language shame (F(2, 257) = 14.97, p = 7.06 × 10−7), and language support (F(2, 257) = 9.079, p = 0.0001). Language expectation and shame were higher in the family context, compared to the school and other contexts. The interpretation may be similar to the results in the homophily group division: the egos may be assumed to speak Spanish to their families and corrected if they do not do so, especially given the fact that family is encouraging them to speak Spanish.

Table 4.

Alter subjective variable means and standard deviation divided by context. Average score for variables and standard deviation in each group over a scale of five (one = lowest; five = highest). Statistical signification is boldened.

4.6. Multiple Regression Analyses

After these first observations, I created linear models in order to describe language attitudes and motivation as a function of alter predictor variables. The dependent variables were the ego’s CLA scores and the ego’s motivation regulation scores. I provide independent/predictor variables below in Table 5.

Table 5.

List of alter and ego variables utilized in the multiple regression analyses. The levels of categorical variables are in brackets.

All the demographic and alter-grouping variables were utilized in the multiple regression analysis, and, then, only those that stood out were isolated into a second, and sometimes third, regression. Per each ego variable, a definition is provided for motivation (Noels et al. 2019; Ryan and Deci 2017) and language attitudes (L. Milroy 2004; Garrett et al. 2003).

4.6.1. External Regulation

External regulation is a type of motivation directly controlled by outside forces: one performs an activity because of a demand or contingency, which results in a reward or a punishment (e.g., better pay at a job or language requirement). In my results, the following two variables stood out: alters’ age, especially those who were older than 50 (24% of sample11) and language support (b = 0.168, t = 3.048, p = 0.0025). Alters’ age negatively predicted external regulation. In having aged alters in their networks, egos may consider Spanish as a hand-me-down past-oriented language. Language support also seemed to contribute to external regulation, possibly due to network encouragement to learn or speak Spanish for their academic requirements or future careers. Although the overall model was close to significance (R2 = 0.056, F(9, 250) = 2.729, p = 0.056), it was not statistically significant at the conventional threshold of 0.05.

4.6.2. Introjected Regulation

Introjected regulation is a motivation that is partially controlled by one who is holding up to others’ evaluations (e.g., community demands) creating a controlling internal force, which may lead either to anxiety or self-pride. In my results, the following three variables stood out: alters’ age, especially those who were in two age groups (31–39 and 60–69; 11% of sample12), language shame (b = 0.146, t = 3.128, p = 0.001), and language confidence (b = −0.194, t = −3404, p = 0.0007). As it could be expected, it was likely that having more language shame would contribute to introjected regulation because of the emotional load depends on alters’ judgments. Alternatively, it is reasonable to hypothesize that having more language confidence would negatively influence introjection. Overall, the model was significant (R2 = 0.08, F(9, 250) = 3.625, p = 0.0002).

4.6.3. Identified Regulation

Identified regulation is a conscious engagement in a behavior because it is personally meaningful. It endorses already existent values and beliefs. In other words, one “identifies” with the new value and sees it as personally important. Language support (b = 0.0822, t = 2.450, p = 0.015) and language confidence (b = 0.05, t = 2.381, p = 0.018) were positive predictors of this regulation. Alter variables, such as encouragement and comfort in speaking, provided by a majority of alters (no distinguishment in terms of context or emotional closeness), were positive towards a regulation that does not depend on community demands or requirements. These two variables foster relatedness to identity; that is, the ego’s network provides the elements that benefit and satisfy relationships with other individuals and the larger social whole (Noels et al. 2019). The model was statistically significant (R2 = 0.05, F(6, 253) = 3.668, p = 0.001).

4.6.4. Integrated Regulation

Integrated regulation is the most autonomous and volitional type of motivation and does not conflict with other abiding identifications (Ryan and Deci 2004, 2006). In my results, the following four variables stood out: alters’ age (only six people, 80–100; b = −0.452, t = −2.427, p = 0.011), language expectation (b = −0.060, t = −2.276, p = 0.020), language support (b = 0.124, t = 3.645, p = 0.0009), and language attitudes (b = −0.141, t = −3.753, p = 0.0002). Having an integrated behavior may imply that the motivation is internalized to oneself. Alters’ low expectations may signify that the ego has internalized the behavior and considers him/her as a genuine community member. Feeling alters’ language support in speaking Spanish is congruent with their identity and belonging to the community, similar to the identity regulation above. Lastly, there was a negative influence of language attitudes on integrated orientation; that is, the lower the score of the alter on the CLA items, the higher the integration. This may be due to the items in the questionnaire measuring particularly US Spanish. Egos may have hypothesized alters’ attitudes based on their own heritage varieties and standard language ideologies, but not necessarily US Spanish phenomena. In the case of linguistically conservative networks; egos may display less CLA in order to integrate in their individual language communities and perpetuate them as part of socialization in their community. This model was significant (R2 = 0.074, F(11, 248) = 2.892, p = 0.001).

4.6.5. Language Attitudes

Language attitudes are “manifestations of locally constructed language ideologies” (L. Milroy 2004, p. 16) that signal group membership (Achugar and Pessoa 2009; Garrett et al. 2003). Positive attitudes towards US Spanish challenge standard language ideologies13 and may be represented in heightened critical language awareness, which is the questioning and the understanding of the relationship between language variation, language status, sociopolitical ideologies, and the repercussions of this relationship (Leeman 2005, 2012; Correa 2011). The variables that stood out were alters’ age (31–39; 70–79; 7% of the sample14) and alters’ language attitudes (b = 0.206, t = 6.495, p = 4.44 × 10−10). This means that, if alters had high scores of language attitudes (i.e., critical language awareness of US Spanish), the egos had high scores too, which is relevant, because having the same attitudes as the community is key in becoming part of a social group (Ryan and Deci 2017). The model was significant (R2 = 0.198, F(9, 250) = 8.116, p = 1.48 × 10−10).

4.7. Alter Variable Correlations

To comprehend the impact of each subjective variable on other variables, I conducted correlations to determine item associations. This is a simpler version of the psychological network analysis presented by Zalbidea et al. (2023) in which they contrasted their motivation and socio-affective variables.

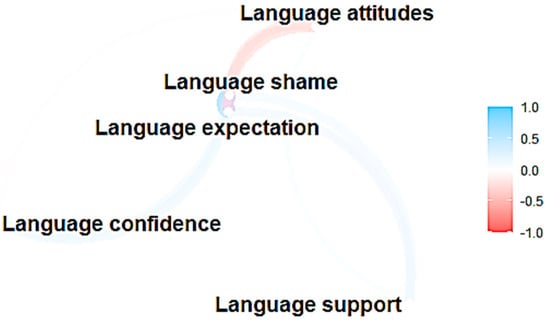

In Figure 2, I am drawing correlations between alters’ subjective variables. That is, the ego answers in lieu of the alter (language attitudes) or the ego reports her feelings towards that alter when speaking Spanish (language expectation, shame, support, confidence). There were small positive but significant correlations between most variables (cor < ±0.30; p < 0.001). Language shame, expectation, support, and confidence showed small correlations, but a strong correlation occurred between language shame and language expectation (cor = 0.678, CI = [0.607; 0.739], t = 14.843, df = 258, p-value = 2.2 × 10−16). This association can be interpreted as having an expectation, which is accompanied by disappointment if the expectation is not met; in this case, if the ego did not use Spanish with the alter (as per their expectation), the alter would be ashamed of the ego. For the smaller positive correlations, if alters support ego’s language endeavor, they may expect more use of Spanish with them. Lastly, as the nominated alters were close and frequently visited, language confidence may be added to the expectation–shame–support association, because the ego is accustomed to using Spanish with them.

Figure 2.

Network showing the correlation between alter subjective variables. Blue indicates a positive correlation, white indicates an absence of correlation, and red indicates a negative correlation.

Language attitudes, however, were negatively correlated with expectation (cor = −0.365, CI = [−0.466; −0.254], t = −6.3005, df = 258, p-value = 1.274 × 10−9) and shame (cor = −0.316, CI = [−0.422; −0.202], t = −5.3615, df = 258, p-value = 1.833 × 10−7). That is, alters with more positive language attitudes were associated with fewer language expectations and shame than alters with negative attitudes towards HL Spanish.

4.8. Summary of Results

In the previous section, I investigated my participants’ Spanish-speaking networks, which may be representative of most informants who participate in HL studies, since most of the previously researched populations are college-aged HSs: most alters were family members, emotionally close, and frequently contacted. After dividing alters by homophily, I found that alters with the same age and gender as the ego provided fewer language expectations and language shame than the rest of alters, but these alters provided more language confidence. After the emotional closeness division, I could see that alters in the core provided more language support than alters in the periphery. Lastly, those alters in the context of family provided more language expectation and language shame, but also more language confidence, than alters in school. After these group divisions, multiple regression analyses utilizing the alter variables to explain motivational regulations revealed further interactions, as follows: introjected regulation was positively affected by language shame, but negatively by language confidence; language confidence and language support contributed to identified regulation; integrated regulation was negatively affected by language expectations and language attitudes, but positively associated with language support. Lastly, alters’ language attitudes contributed significantly to the egos’ own. The results from the multiple regressions above, besides being reliable, yielded an R-squared value congruent with the previous literature on language attitudes, which give a range from 3% to 16% of explanatory power to psychosocial factors (e.g., Masgoret and Gardner 2003; Serafini 2013; Torres et al. 2019). Lastly, the association among alter variables showed that language expectation, language shame, and language support may be representative of HSs, who have, in the same context, people that praise their efforts to learn Spanish and people that are disappointed in their bilingual English-influenced skills.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the extent to which social network analysis can contribute to the understanding of HL learning attitudes and motivations; in other words, how network measures, or characteristics of one’s community, can contribute to HL motivation and attitudes. To this end, I recruited 26 HSs to complete questionnaires gauging language learning motivation (based on Noels 2005), language attitudes as reflected by critical language awareness (based on Beaudrie et al. 2019), and a SN survey (based on Krenz and Losee 2022). The following exploratory research question guided this research:

- To what extent are the language learning motivations and attitudes of HSs influenced by their social networks?

Answering the first part of the question, learning about HSs’ network composition and the subsequent group divisions (homophily, core–periphery, and context) was helpful in two ways. First, it helped me in visualizing the social picture of my egos/participants. This social picture may portray the typical Spanish-speaking college-aged community of HSs in Florida, especially of people who live in long-established and dense Hispanic areas (most of my participants were from Miami). The social situation may help to keep families and communities closer than newer migratory destinations (e.g., North Dakota) because business and culture have already prospered, and the community can be extended beyond the household. I propose that the location and setting also influence motivational regulations. For instance, my results showed that a predictor of external regulation, which not only deals with language requirements but also pragmatic/instrumental value of Spanish, was language support. Given the Florida context, the fact that my participants felt supported to speak Spanish and that they had external motivations to do so may indicate that their networks consider the HL relevant for their bilingual careers (but see Lynch 2022).

Secondly, although not statistically significant, I was able to isolate which alters may play an important role in language expectations, shame, and support (e.g., family), and those who did not (e.g., same-age alters). Additionally, in the multiple regression analyses, a predictor of introjected regulations emerged: language shame and language confidence, which both contributed negatively to this regulation. This finding is relevant because it may illustrate heritage speakers’ preference for standard varieties of Spanish (e.g., Gasca Jiménez and Adrada-Rafael 2021), due to the support they receive from alters who may be monolingual Spanish speakers (e.g., older family members). Simultaneously, HSs may have disdain for their own bilingual features (e.g., Beaudrie et al. 2021) because of the shame and disappointment they also experience from their same network community.

Since this study utilizes the self-determination theory framework for the analysis of language learning motivation, it presupposes four types of motivation regulations that depend on extrinsic forces: external, introjected, identified, and integrated (Ryan and Deci 2017; Deci and Ryan 1985). In the previous multiple regression analyses, I found that the alter subjective variables that would yield negative emotions, i.e., language shame, were related to introjected regulation. This type of regulation involves approval from others and creates a controlling internal force, a sense that one “should” or “must” do something (Ryan and Deci 2017). Earlier studies have revealed the pressure students experience within their families to uphold their heritage language. Consequently, they enroll in courses as a means to fulfill this obligation, even if it may not be personally fulfilling for them (Comanaru and Noels 2009). Alternatively, language support and language confidence were present at different levels playing different roles. Above, I interpreted that support to study the language may influence instrumental motivations (external regulation) to learn Spanish, but also identity (identified regulation) and integration (integrated regulation) of behaviors, which are explained by the fulfillment of relatedness15.

Answering the second part of the research question, a predictor of egos’ attitudes was alters’ attitudes. That is, if the participant was part of a network with positive language attitudes towards US Spanish, theirs would be positive too. My research confirms what others have found, that individuals’ mindsets often align with those of the community due to the absorption of external principles and convictions, regardless of their positivity or negativity, in other words, the phenomena of interiorization (Deci and Ryan 1985; Ryan and Deci 2017). Sharing these values is a result of socialization, and they gradually become part of oneself as they develop into being more congruent with one’s identity (Ryan and Deci 2017).

However, I also found that language attitudes, more particularly challenges to standard language ideologies, were negatively predicting integrated regulation. In order to tap into the deepest source of motivation for HSs to speak Spanish, they needed to assimilate the prevailing language ideologies within their community. As I previously mentioned, having the same values towards language may be part of socialization, even if these attitudes are somewhat linguistically conservative. The results from Zalbidea et al. (2023) support this idea, as they found, in their network model, tentative evidence of less critical language awareness being associated with more familial pressure to study the HL in formal contexts. In other words, formally studying the HL was promoted in contexts with lower critical language awareness, probably due to the belief that education institutions are central in internalizing dominant ideologies about language appropriateness and standardness (Leeman 2012). It may be possible that the negative schemas surrounding the HL may be present in HSs’ social context and subsequently interiorized. Despite being linguistically conservative, language attitudes such as these index integration in their communities (Achugar and Pessoa 2009).

This finding is particularly relevant and, in connection with a critical language awareness approach, has great potential for pedagogical implications. It was shown that students’ perceptions of language expectations could lead to feelings of language shame. To combat these expectations, instructors ought to help HSs become conscious of the social nature of linguistic ideologies so that students can become agents of change (e.g., Freire 1976). Instructors ought to help students to advocate for their HL and for other HL speakers who have not had the opportunity to engage with critical thinking about language. In other words, once HSs take our SHL courses, they can become HL ambassadors in their communities emblazoning bilingual varieties, honoring all dialects, and representing a future for the HL. This can be achieved by empowering students with knowledge, letting them research their relationship to Spanish and their families, community-based projects, and so on (e.g., Parra 2021).

In sum, this study has ultimately depicted language motivation and attitudes through a socially informed perspective, aligning with the recommendations put forth by previous research (Beaudrie and Loza 2022; Ducar 2012; Ortega 2021). It has allowed me to analyze more in depth the roles that language shame, support, and confidence play with motivation, especially with introjected, identified, and integrated regulations. These results align with the range of previous literature on explanatory power to psychosocial factors (e.g., Masgoret and Gardner 2003; Serafini 2013; Torres et al. 2019).

6. Conclusions

This study has provided novel insights into the understanding of the influence of social networks on HSs’ motivation and attitudes towards learning Spanish. It has shown evidence of alters being a source of both negative (e.g., language shame) and positive (e.g., language support) influence to learn and maintain the HL. The findings offer methodological and pedagogical implications on how we need to consider the context beyond HSs. In this sense, this SN survey has been efficient for recreating the environment outside of the classroom and showing how language shame, support, and confidence shape students. However, these findings should be interpreted considering their own limitations.

To begin with, the network size was not large enough to capture a clear emotional core and periphery. In the case of HSs, it is probable that only 10 specific alters would be the most relevant people in their social circles, but not enough to represent the complex relationships in the network; 15 may provide a more complex analysis (Burt 2000). Furthermore, most alters provided were mainly Spanish speakers, but there may be English-speaking alters who may also influence students’ decision regarding learning Spanish. This is a shortcoming that must be addressed in future research. Lastly, an important factor to take into account when drawing the alter list is the current age and situation of my participants, since the college years may be, for many students, the moment in which they choose, with freedom, their own social circles and in which they start developing their own communities. PSNA literature has acknowledged the impact of the college years on cultural minority students (e.g., Lukács and Dávid 2019; Rios Aguilar and Deil-Amen 2012).

Beyond the sample size, answers depended on egos’ subjectivity, and they may not be fully reliable, especially in questions in which HSs’ guessed alters’ opinion—alters may have never explicitly expressed their opinion on the same items that egos were asked about. Similarly, egos reported how they felt about their alters and the repercussion of speaking (or not) Spanish with them but alters may not have voiced their concern or support. Egos may have adjusted alters’ answers to the supposed role of those people in their lives (e.g., “how is my father not going to support my decision to learn Spanish?”). Lastly, further research would benefit from including a sample of alters and egos who belong to different backgrounds (e.g., not registered in a Spanish HL program or not enrolled in college) because we would be able to capture heritage speakers’ network configurations in more diverse life situations.

I conclude with pedagogical suggestions to improve HL learners’ outcomes. Considering the alters’ role in generating language expectations, language shame, and language support, I propose that students should know about their networks. That is, they should be aware of the people in their respective networks and how they influence their learning. For instance, by utilizing a user-friendly app like Network Canvas Architect (Janulis et al. 2023), students can visualize with whom they speak Spanish and set goals to broaden their language usage beyond those limited interactions. By helping students acknowledge the context in which they use Spanish, they may be inclined to actively expand their Spanish-speaking networks. Future studies should investigate the implementation of social network-based activities in the classroom to promote language use and student retention. Similarly, students can work on lowering language shame and fostering language support by talking about Spanglish with members of their network and research about misperceptions of it in order to dismantle language ideologies. This can be achieved with oral histories and/or family cultural projects. In theory, the network effect should work both ways. If students can effectively engage with their communities to address language expectations and cultivate language support, we may observe a positive transformation in their networks regarding the perception of Spanish in the United States.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Florida (protocol code IRB202102707 and date of approval 12 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | SNA is divided into sociocentric network analysis and personal social network analysis. Sociocentric or whole networks investigate the pattern of relationships between actors in a defined and limited community in a context (McCarty et al. 2019). For instance, with sociocentric network analysis, we could research the relationships between the employees of a company or students in a classroom. |

| 2 | This term is borrowed from the theory of possible L2 selves (Dörnyei 1994, 2009), which posits that learners perceive an association between their current and future self-concepts, and they desire to move from one’s actual to future L2 selves, which drives their motivated learning behavior. |

| 3 | Here, “generation” refers to Silva-Corvalán’s (1994) definition of sociolinguistic generation, which labels individuals depending on an individual’s age or their predecessors’ when they arrived or were born in the United States. |

| 4 | Students were able to stop and resume with the questionnaire later. |

| 5 | In the SHL program, the majority of students are female; hence, there were more female participants. |

| 6 | LM was a 3rd generation Cuban student taking her first class in the SHL program (intermediate proficiency level). She spoke regularly in Spanish with her grandparents and relatives. |

| 7 | GC was a 3rd generation speaker from a Puerto Rican background taking her first SHL class (intermediate proficiency level). She would speak Spanish regularly with her mom and her girlfriend. |

| 8 | AR was a 2nd generation speaker from Nicaragua. She was raised by her parents exclusively in Spanish and was regularly in touch with family in Nicaragua. |

| 9 | Spanglish refers to the linguistic phenomenon resulting from the contact between Spanish and English in the United States (Fairclough 2003). |

| 10 | On a scale of one to five, how close are you to this person? one = not close at all; two = less close; three = somewhat close; four = very close, five = extremely close. |

| 11 | Age group: 50–59 (b = −0.326, t = −1.969, p = 0.05); age group: 60–69 (b = −0.373, t = −2.013, p = 0.045); age group: 80–100 (b = −0.662, t = −2.280, p = 0.023). |

| 12 | Age group: 31–39 (b = −1.061, t = −2.375, p = 0.018); age group: 60–69 (b = −0.777, t = −2866, p = 0.004). |

| 13 | Standard language ideologies assume that there is a variety that holds correctness, authority, prestige, and legitimacy over others (J. Milroy 2007). |

| 14 | Age group: 31–39 (b = −0.514, t = −3.124, p = 0.001); age group: 70–79 (b = 0.269, t = 2.235, p = 0.026). |

| 15 | Relatedness refers to a sense of warmth, security, and connection between the learner and other people in that social context (Comanaru and Noels 2009). |

References

- Achugar, Mariana, and Silvia Pessoa. 2009. Power and Place. Spanish in Context 6: 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual, Mark. 2018. Asymmetrical Interlingual Influence in the Production of Spanish and English Laterals as a Result of Competing Activation in Bilingual Language Processing. Journal of Phonetics 69: 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, Paula A. 2005. Family Context and Spanish-Language Use: A Study of Latino Children in the United States. Social Science Quarterly 86: 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara, and Sergio Loza. 2022. Heritage Language Program Direction Research into Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara, Angelica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2019. Critical Language Awareness for the Heritage Context: Development and Validation of a Measurement Questionnaire. Language Testing 36: 573–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara, Angélica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2021. Critical Language Awareness in the Heritage Language Classroom: Design, Implementation, and Evaluation of a Curricular Intervention. International Multilingual Research Journal 15: 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David, Libby Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis, Richard Yvon, Howard Giles, and Doreen Rosenthal. 1981. Notes on the Construction of a ‘Subjective Vitality Questionnaire’ for Ethnolinguistic Groups. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 2: 145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, Ronald S. 2000. The Network Structure of Social Capital. Research in Organizational Behavior 22: 345–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandruccio, Lauren, Isabella Beninate, Jacob Oleson, Margaret K. Miller, Lori J. Leibold, Emily Buss, and Barbara L. Rodriguez. 2021. A Simplified Approach to Quantifying a Child’s Bilingual Language Experience. American Journal of Audiology 30: 769–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comanaru, Ruxandra, and Kimberly A. Noels. 2009. Self-Determination, Motivation, and the Learning of Chinese as a Heritage Language. The Canadian Modern Language Review 66: 131–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]