Abstract

In this paper, we provide an overview of negative dependencies in Turkish. The first are elements such as hiçkimse, which sometimes seem to mean ‘anybody’ and sometimes ‘nobody’. We argue that unlike a standard Negative Polarity Item (NPI) like English anybody, these items should be analyzed as neg-words licensed under Negative Concord (NC). We also discuss further properties of these items, including whether they are universals or existentials. The second set of items that display a negative dependency are universal quantifiers such as herkes ‘everybody’. Unlike their counterparts in many languages, these items obligatorily scope under negation, which raises the question of why a universal is sensitive to negation in the way it is. We account for this behavior in terms of negative polarity sensitivity based on a referentiality requirement we dub the Non-Entailment-of-Non-Existence Condition, following a particular analysis of a class of NPIs in Mandarin. The final case of negative dependency we evaluate is modals that have to scope under or above negation. These cases constitute instances of polarity sensitivity in English and beyond, especially clearly in the case of modal PPIs. We show that in Turkish, however, they do not, and the apparent negative dependency follows from the syntax of Tense-aspect-modality (TAM) morphology.

1. Introduction

A familiar type of negative dependency is exemplified by existential Negative Polarity Items (NPIs) in languages like English, illustrated in (1) with anybody. Such elements can only appear alongside negation and in other Downward-Entailing (DE) or Non-Veridical (NV) contexts, including antecedents of conditionals and content questions (Ladusaw 1979; Giannakidou 2000, among others). They are not in themselves negative, unlike negative quantifiers like nobody.

| (1) | a. | *Sue saw anybody. |

| b. | Sue did not see anybody. | |

| c. | If Sue sees anybody, she will let me know. | |

| d. | Who saw anybody? |

Next to such English-like NPI-hood, several other kinds of negative dependencies have been identified, the most prominent of which is Negative Concord (NC; Giannakidou 2000; Zeijlstra 2004; Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017 a.o.). Negative Concord Items (NCIs), or neg-words, are the most restrictive kind of NPIs in that they are only licensed under negation and not under other DE/NV contexts (Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017). While these elements require licensing by negation just like anybody, they can induce semantic negation on their own, as the name neg-word implies, unlike anybody. This can be seen in their ability to answer a question negatively in fragment answers. (2) exemplifies the negative sensitivity of the Greek neg-word stressed TIPOTA in (2a) and its ability to induce semantic negation as exhibited by a fragment answer (2b).1

| (2) | a. | *(Dhen) ipa TIPOTA. | |

| not said.1sg n-thing | |||

| ‘I didn’t say anything.’ | |||

| b. | A: Ti idhes? | ||

| what saw.2sg | |||

| ‘What did you see?’ | |||

| B: TIPOTA. | |||

| n-thing | |||

| ‘Nothing.’/‘#Anything.’ | (Giannakidou 2000) |

Notice that TIPOTA acts like nothing in the fragment answer, whereas it acts like anything in the full sentence. This is the prime blueprint of a neg-word. Various attempts have been made to account for this dual behavior of neg-words, from syntactic licensing mechanisms (Zanuttini 1991; Watanabe 2004; Zeijlstra 2004, 2022) to restrictive semantic formulations (Ladusaw 1992; Giannakidou 2000, 2006). It is similarly debated whether these elements are existentials or universals in their various realizations across languages (cf. Giannakidou 2000; Zeijlstra 2004, 2022 a.o.). We remain theory-neutral in this article regarding the first point, but in Section 2, we will analyze a class of negative dependents in Turkish as neg-words and address the question of whether they are existentials or universals.

Another kind of negative dependency that goes beyond English-type NPI-hood is exhibited by quantifiers that are otherwise transparent universals that have to scope in a certain way with respect to negation. For example, in Dutch, iedereen ‘everybody’ obligatorily scopes over negation, instead of the two scopal construals available to English everybody in such constructions.

| (3) | Iedereen vertrok niet. | ||

| everybody left not | |||

| ‘Nobody left.’ | ∀ > ¬; ∗¬ > ∀ | (Zeijlstra 2017) |

Conversely, sometimes universals can avail themselves only of narrow scope readings with respect to negation. Amiraz (2021) calls these constructions where a universal subject precedes, yet underscopes, negation, inverse scope constructions.

| (4) | All that glitters is not gold. | ¬ > ∀; *∀ > ¬ |

There is comparatively little work on these phenomena in the literature. Zeijlstra (2017) argues that Dutch universals scoping above negation are effectively Positive Polarity Items (PPIs). The common wisdom regarding narrow scope universals is that languages that have no other transparent way to express this scope configuration exceptionally allow this reading under rules of blocking (Szabolcsi 1997 a.o.). We know of no treatment of universals that systematically prefer or require an inverse scope reading. In Section 3, we argue that Turkish universals exhibit exactly this pattern and sketch a preliminary analysis in terms of a referentiality requirement we call the Non-Entailment-of-Non-Existence Condition (NENEC).

A third kind of negative dependency observed in the literature concerns modals. Modals behave like quantifiers over individuals in many respects (Kratzer 1991), and hence they à priori may be subject to similar polarity and dependency relations. Based on this reasoning, Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2010, 2013) argue that the otherwise mysterious scope restrictions on modals such as English need and must arise due to a kind of negative dependency (5).2 In this approach, need is an NPI (it clearly requires negation; cf. Van der Wouden 1994), whereas must is a PPI (it obligatorily scopes over negation).

| (5) | a. | Mary need*(n’t) leave. | |

| b. | Mary mustn’t leave. | □ > ¬; *¬ > □ |

In Section 4, we will investigate whether a similar analysis can be pursued for Turkish modals, which have fixed scope with respect to negation but appear as suffixes on the verb in a concatenative morphological system, and conclude negatively.

As we will argue in the rest of this paper, Turkish is a language that exhibits NC and narrow scope universals, the latter being a crosslinguistically more novel finding. In addition, we will argue that modal scope in Turkish is better explained in terms of functional morphosyntax rather than polarity sensitivity. Our study will be descriptive, but we believe there are advantages to observing these lesser-understood negative dependencies in empirical detail within a single language.

Concretely, the three Turkish negative dependencies we will scrutinize in the rest of this paper are exemplified in (6).

| (6) | a. | Hiç-expressions: Negative Concord | |

| Deniz hiçbir şey bil*(-m)-iyor.3 | |||

| Deniz n-one thing know-neg-pres | |||

| ‘Deniz knows nothing.’ | |||

| b. | Her-expressions: Narrow scope universals | ||

| Her öğrenci yürü-me-yecek. | |||

| every student walk-neg-fut | |||

| ‘Not every student will walk.’ | ¬ > ∀; *∀ > ¬ | ||

| c. | Modals with fixed scope with respect to negation | ||

| Oya dans et-me-yebil-ir. | |||

| Oya dance do-neg-abil2-aor | |||

| ‘Oya is allowed not to dance.’ | ◊ > ¬; *¬ > ◊ | ||

In (6a), we see a structure quite similar to (1a), which has led to expressions with hiç in Turkish being termed NPIs (Kelepir 2001; Özyıldız 2017, among many others), as they cannot appear without the negative suffix -mA.4 We will demonstrate that their distribution is more complex and should not be analyzed as standard NPIs, unlike what is generally assumed in the Turkish literature (e.g., Kelepir 2001). In (6b), we see a (non-negative) universal subject quantifier taking obligatory scope under negation, despite Turkish being heavily scope-rigid (as discussed by Kelepir 2001).5 In (6c), we find a modal that does the opposite, scoping obligatorily over negation. On the face of it, this could be a negative dependency, specifically a PPI dependency. However, we will argue that the source of this behavior is different from polarity sensitivity.

2. Hiç-Expressions and Negative Concord

In this section, we look at a class of negative dependents in Turkish that have previously been labeled NPIs. This analysis and some of the observations made in this section are based on Kelepir (2001), who considered these items to be NPIs due to their dependent behavior in relation to negation. However, we will argue that subsequent research on NC, especially on Strict NC (Giannakidou 2000, 2006; Zeijlstra 2004), provides a more fitting, stricter label for these expressions as neg-words. Once this is established, we will explore whether Turkish neg-words should be analyzed as universal or existential neg-words.

2.1. Negatively Marked Elements in Turkish

Turkish has a set of negatively marked elements requiring licensing by negation. A class of these are formed with the morpheme hiç ‘n-at all’ appearing on its own or as part of a paradigm of morphologically complex expressions, such as hiçbir şey ‘n-one thing’ (7). In examples like the latter, hiç is written together with bir ‘one’ by orthographic convention. Some expressions, like asla ‘never’ and katiyyen ‘under no circumstances’ do not include the morpheme hiç but nevertheless show similar licensing restrictions (also see Kelepir 2001).

| (7) | a. | hiç | ‘n-at all, n-ever, n-amount’ |

| b. | (hiç) kimse | ‘n-person’6 | |

| c. | hiçbir şey | ‘n-thing’ | |

| d. | hiçbir yer | ‘n-place’ | |

| e. | hiçbir zaman | ‘n-time’ |

There are no (near) homonyms to hiç-expressions; the items in (7) represent the entire set of items corresponding to both typical English NPIs like ever and any x and English negative quantifiers like never and no x. This is irrespective of factors such as stress, unlike, for example, in Greek (Giannakidou 2000). If the hiç morpheme is missing, these elements are plain indefinites:

| (8) | a. | birisi/birileri | ‘someone’ (lit: one of that/them) |

| b. | bir şey | ‘something’ | |

| c. | bir yer | ‘some place’ | |

| d. | bir ara | ‘some time’ (lit: one interval) |

Turkish has only a limited set of expressions that require licensing by negation in NPI-like fashion, other than hiç-expressions. One such case is minimizers, which appear to be NPIs with a concealed even connotation, as in tek kuruş ‘single dime’ and bir Allah’ın kulu ‘a soul (lit: one servant of god)’. (9) shows that each of these three kinds of negative dependents requires sentential negation. (9a) has a hiç expression, (9b) includes katiyyen ‘under no circumstances’, and (9c) contains a minimizer NPI. Sentential negation is expressed by the suffix –mA in the verbal complex.

| (9) | a. | Recep hiçbir şey oku*(-ma)-z. |

| Recep n-one thing read-neg-aor | ||

| ‘Recep doesn’t read anything.’ | ||

| b. | Kedi katiyyen dışarı çık*(-ma)-yacak. | |

| cat under.n.circumstances out go-neg-fut | ||

| ‘The cat will under no circumstances go outside.’ | ||

| c. | Bütün gün dükkan-da dur-du-m ama bir Allah’ın kul-u gel*(-me)-di. | |

| all day shop-loc stay-past-1sg but one god-gen servant-poss3sg come-neg-past | ||

| ‘I was at the shop all day but not a soul stopped by.’ |

We focus in this section on the first class of these negation-requiring items with hiç, and argue that they are so-called neg-words or NCIs, not standard NPIs. To support this, we will draw upon comparisons between hiç-expressions and minimizer NPIs, among other evidence.

2.2. NPI Licensing and Negative Concord in European Languages

The main difference between NPIs and neg-words is that the latter, but not the former, can induce negation on their own in particular contexts, for instance, in fragment answers (see Giannakidou 2006; Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017). To set up the comparison, we will first look at the behavior of neg-words and plain NPIs in other European languages.

Typical NPIs, such as English anybody and ever, are indefinites. They do not encode negativity in themselves but generally require licensing by DE or NV environments, including negation (10) (see Ladusaw 1992; Giannakidou 2000). The fact that they do not encode negation is manifested by the inability to answer a question negatively on their own (11).

| (10) | I will *(not) meet anybody this afternoon. |

| (11) | A: Who did you say you will meet? |

| B: #Anybody. (intended: ‘Nobody.’) |

By contrast, negative quantifiers such as English nobody do not require (in fact, reject in standard varieties unless double negation is intended) licensing by a negative marker and always encode negativity by themselves.

| (12) | I will (*not) meet nobody this afternoon. |

| (intended: ‘I will not meet anybody this afternoon.’) |

| (13) | A: Who did you say you will meet? |

| B: Nobody. |

Neg-words are elements that, in certain contexts, require licensing by negation, just like standard NPIs, while in other contexts they behave like negative quantifiers, giving rise to NC effects. NC is the phenomenon where multiple elements that in certain configurations yield semantic negation of their own, jointly yield only one. English does not employ neg-words; it is not an NC language (at least in the standard variety), but many languages do. One such language is Italian. Italian nessuno is best translated as ‘anybody’ in (14a), but as ‘nobody’ in (14b). (14c) shows that nessuno is fine in a fragment answer, inducing negation on its own.

| (14) | a. | Non ha telefonato a nessuno. | |

| Not has called to n-body | |||

| ‘She hasn’t called anybody.’ | |||

| b. | Nessuno ha telefonato. | ||

| n-body called | |||

| ‘Nobody called.’ | |||

| c. | A: A chi ha telefonato? | ||

| to whom has called | |||

| ‘Whom has she called?’ | |||

| B: A nessuno. | |||

| to n-body | |||

| ‘Nobody.’ | (Zeijlstra 2004) |

In languages like Italian, postverbal neg-words must be licensed by a preverbal negative element (either the negative marker or a preverbal neg-word). Conversely, preverbal neg-words may not be licensed by the negative marker, as shown in (15). NC languages with such an asymmetry are called Non-strict NC languages.

| (15) | a. | *(Non) ha telefonato a nessuno. | |

| Not has called to n-body | |||

| ‘She hasn’t called anybody.’ | |||

| b. | Nessuno (*non) ha telefonato. | ||

| N-body called | |||

| ‘Nobody called.’ | (Zeijlstra 2004) |

Not all languages with neg-words have such restrictions with respect to the position of the neg-word. In so-called Strict NC languages, illustrated by Czech in (16), the negative marker must always accompany a neg-word, irrespective of the position of the neg-word in the clause, unlike in Italian. Only in fragment answers can neg-words induce semantic negation on their own (c).

| (16) | a. | Dnes nikdo *(ne-)volá | |

| today n-body neg-calls | |||

| ‘Today nobody calls.’ | |||

| b. | Dnes *(ne-)vola nikdo. | ||

| Today neg-calls n-body | |||

| ‘Today nobody calls.’ | |||

| c. | A: Co jsi viděla | ||

| What aux.2sg saw. sg.f | |||

| ‘What did you see?’ | |||

| B: Nic. | |||

| n-thing | |||

| ‘Nothing.’ | (Radek Šimík, p.c.) |

Next to the fact that plain NPIs can never induce semantic negation, but neg-words can (in any case in fragment answers), there is another characteristic difference between standard NPIs and neg-words. Most NPIs can be licensed, in addition to negation, in contexts such as polar and content questions and antecedents of conditionals (Ladusaw 1979; Giannakidou 2000; Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017 a.o.).7 Neg-words, however, are only licensed by the negative marker (Zeijlstra 2004) and, in some cases, in polar questions. Hence, an English NPI like any is licensed in content questions (17a), whereas neg-words like nic ‘n-thing’ in Czech are not (17b).8

| (17) | a. | Who noticed anything suspicious? | |

| b. | *Kdo viděl nic? | ||

| who saw.sg.m n-thing | |||

| (‘Who saw anything (at all)?’) | (Radek Šimík, p.c.) |

Another notable difference between standard NPIs and neg-words is that the licensing of neg-words is subject to syntactic locality, but NPI licensing is not. For this reason, the English NPI any is licensed in an adjunct island (18a), but Italian niente is not (18b):

| (18) | a. | Gianni doesn’t work in order to earn any money. | |

| b. | *Gianni non labora per guadagnare niente argente. | ||

| Gianni not works in.order.to earn no money | |||

| (‘Gianni doesn’t work in order to earn any money.’) | (Zeijlstra 2022) |

2.3. NPI Licensing and Negative Concord in Turkish

The first of our claims regarding Turkish negative dependencies is that Turkish expressions with hiç are neg-words and not plain NPIs (contra Kelepir 2001); hence, Turkish is an NC language. It is, in fact, a Strict NC language, as the subject position is also licensed by sentential negation (19b).

| (19) | a. | Bugün hiçkimse-yle toplantı yap*(-ma)-yacağ-ım. |

| today n-body-com meeting do-neg-fut-1sg | ||

| ‘I will meet nobody today.’ | ||

| b. | Hiçbir öğrenci toplantı-ya gel*(-me)-di. | |

| n-one student meeting-dat come-neg-past | ||

| ‘No student came to the meeting.’ |

Evidence for this comes from the fact that neg-words require a negative marker as a licenser (19), similar to NPIs, but can appear on their own in a fragment answer with the meaning of a negative quantifier (also see Kelepir 2001) (20).

| (20) | A: | Kim-in-le toplantı yap-acak-tı-n? |

| who-gen-com meeting do-fut-past-2sg | ||

| ‘Who did you say you were meeting?’ | ||

| B: | Hiçkimse-yle. | |

| n-body-com | ||

| ‘With nobody.’ |

Turkish neg-words further behave on par with NC items in that they require licensing by the negative marker and not just any DE/NV context, as shown in (21) below (also see Kelepir 2001). Contexts such as content questions and antecedents of conditionals do not license hiç-expressions; the negative marker is required.

| (21) | a. | *Kim şüpheli hiçbir şey fark et-ti? |

| who suspicious n-one thing notice do-past | ||

| (‘Who noticed anything suspicious?’) | ||

| b. | *Şüpheli hiçbir şey fark ed-er-se-niz biz-i ara-yın. | |

| suspicious n-one thing notice do-aor-cond-2pl we-acc call-imp.2pl | ||

| (‘Give us a call if you notice anything suspicious.’) |

Kelepir (2001) notes these facts concerning the ability of hiç-expressions to give rise to semantic negation in fragment answers and their inability to occur in NPI-licensing contexts other than negation, and discusses them in the context of whether they are NPIs (like anybody) or negative quantifiers (like nobody). She argues that the fact that these expressions do not induce double negation readings under negation (nor under multiple hiç-expressions; Kelepir 2001, p. 160) and the fact that they are licensed by –sIz ‘without’ are evidence that they are not negative quantifiers. She briefly considers and dismisses the possibility that they are neg-words, based on the fact that hiç-expressions require licensing also in the subject position, unlike Romance-type neg-words (as in 19b). However, if Turkish is a Strict NC language, as we claim, this argument would be moot. We give below two further arguments based on a contrast between Turkish minimizers and hiç-expressions to substantiate our claim that the latter are not licensed on par with NPIs in the same language.

First, consider the syntactic contexts in which minimizer NPIs are licensed in Turkish. Unlike hiç-expressions, these expressions cannot yield negation and hence cannot appear in fragment answers (22). Also unlike hiç-expressions, they are fine in content questions and conditionals (23).

| (22) | A: | Kim-in-le toplantı yap-acak-tı-n? |

| who-gen-com meeting do-fut-past-2sg | ||

| ‘Who did you say you were meeting?’ | ||

| B: | *Bir Allah’ın kul-u-yla. | |

| one god-gen servant-poss3sg-com | ||

| ‘*With a soul.’ |

| (23) | a. | Kim tatil-de bir Allah’ın kul-u-yla görüş-tü? |

| who holiday-loc one god-gen servant-poss3sg-com meet.up-past | ||

| ‘Who met a soul during the holidays?’ | ||

| b. | Bun-u bir Allah’ın kul-un-a söyle-r-se-n sen-in-le | |

| this-acc one god-gen servant-poss3sg-dat say-aor-cond-2sg you-gen-com | ||

| arkadaşlığ-ı kes-er-im. | ||

| friendship-acc stop-aor-1sg | ||

| ‘If you tell a soul about this, I will stop being friends with you.’ |

Another difference between Turkish minimizer NPIs and neg-words is their ability to appear in non-negated ne…ne… ‘neither nor’ constructions, as exemplified in (24b). This is one of the very few documented constructions in Turkish that express negation without requiring the negative marker on the verb.9 In failing to mark negation on the verb, the construction is similar to the English neither…nor… construction, both in meaning and structure (see Jeretič 2022; Gračanin-Yüksek 2023).

First, contrast the negated (24a) and non-negated (24b) ne…ne… constructions. The non-negated construction that we are interested in needs to carry focus (cf. Şener and İşsever 2003). We indicate this by underlining the rightmost word of the ne…ne… sequence where the resulting nuclear pitch accent falls (see 24b). In the negated construction in (24a), the nuclear pitch accent falls on the verbal complex, where the negative morpheme is found. In the non-negated construction in (24b), there is no negation on the verb, yet the interpretation is negative, as in (24a).

| (24) | a. | Ne Emre ne Merve okul-a git-me-di. |

| NE Emre NE Merve school-dat go-neg-past | ||

| ‘Neither Emre nor Merve went to school.’ | ||

| b. | Ne Emre ne Merve okul-a git-ti. | |

| NE Emre NE Merve school-dat go-past | ||

| ‘Neither Emre nor Merve went to school.’ |

Negated ne…ne… constructions like in (24a) should straightforwardly provide a licensing context for negative dependencies due to the presence of the negative marker. This is indeed true for all negative dependents, including hiç-expressions (25).

| (25) | Ne Emre ne Merve hiçbir yer-e git-me-di. |

| NE Emre NE Merve n-one place-dat go-neg-past | |

| ‘Neither Emre nor Merve went anywhere.’ |

The non-negated construction, however, has limited licensing powers. It can license minimizer NPIs, as in (26a).10 Hiç-expressions, on the other hand, are not licensed by the non-negated ne…ne… construction (26b). This suggests, again, that hiç-expressions are genuine neg-words requiring the negative marker in the clausal spine.

| (26) | a. | (?)Ne Emre ne Merve tek kuruş harca-dı. |

| NE Emre NE Merve single dime spend-past | ||

| ‘Neither Emre nor Merve spent a dime.’ | ||

| b. | *Ne Emre ne Merve hiç para harca-dı. | |

| NE Emre NE Merve n-amount money spend-past | ||

| (‘Neither Emre nor Merve spent any money.’) |

All of this indicates that Turkish expressions with hiç are neg-words. Unlike other kinds of NPIs, they may appear without negation in fragment answers, yet they need to be licensed otherwise. And, again unlike other NPIs, they need to be licensed strictly by clausal negation. Other DE/NV contexts or the likes of the non-negated ne…ne… construction cannot license them.11 This indicates that this dependency does not involve regular NPI licensing but rather NC (see Ladusaw 1992; Giannakidou 2000; Zeijlstra 2004, and others).

One point of discussion, though, concerns polar questions. We have noted that in Turkish and elsewhere, neg-words cannot appear in content questions. In many NC languages, they are also banned from polar questions. Japanese is such an example (see Giannakidou 2000 for more examples). Negation is required to license the neg-word nani-mo ‘n-thing’ (lit. what-also) in (27a). Content questions are not licensing environments (27b). Neither are polar questions (27c).

| (27) | a. | Taroo-wa nani-mo mie*(-naka)-tta. | |

| Taroo-top n-thing see-neg-past | |||

| ‘Taroo didn’t see anything.’ | |||

| b. | *Dare-ga nani-mo mi-mashi-ta-ka? | ||

| who-nom n-thing see-hon-past-q | |||

| (‘Who saw anything?’) | |||

| c. | *Taroo-wa nani-mo mi-mashi-ta-ka? | ||

| Taroo-top n-thing see-hon-past-q | |||

| (‘Did Taroo see anything?’) | (Daiki Matsumoto, p.c.) |

While we have seen that Turkish presents the same pattern as Japanese with respect to declaratives and content questions, the situation with polar questions is different. Polar questions constitute an NC context in Turkish (28a; also see Kelepir 2001). However, this is only true for a subset of polar question configurations. The focus-sensitive polar question clitic must be on the verbal complex to license NC. In other placements (indicated in triangular brackets), licensing is not possible (28b) (Kamali 2011).

| (28) | a. | Hiçkimse yemek yap(-ma)-dı mı? |

| n-body dinner make-neg-past pq | ||

| ‘Did(n’t) anyone make dinner?’ | ||

| b. | Hiçkimse <mi> yemek <mi> yap*(-ma)-dı? | |

| n-body pq dinner pq make-neg-past | ||

| (‘Did NOONE make dinner?’) | ||

| (‘Did noone make DINNER?’) |

This begs the question as to why neg-words may appear in this particular polar question configuration. It is known from Non-strict NC languages (e.g., Spanish/Italian; Zeijlstra 2004) that neg-words may appear in polar questions, but this has not been reported for Strict NC languages. We leave this question open for further research (but see Kamali and Matsumoto, forthcoming, for a recent proposal).

2.4. The Domain of Negative Concord in Turkish

Before drawing a final conclusion, we would like to briefly investigate the locality of NC in Turkish. Long-distance licensing of NC is generally considered impossible (Giannakidou 2000; Zeijlstra 2004), but certain matrix predicates and their morphosyntactic associates have been shown to provide transparent domains (see, for example, Giannakidou and Quer 1997). Turkish hiç-expressions, on the other hand, appear to be licensed across clause boundaries with a few exceptions.

Turkish uses a few strategies to embed clauses. The standard method is nominalization, where the embedded subject carries the genitive case instead of the nominative, and the predicate carries a nominalizing morpheme. The internal structure of the nominalization is not fully morphologically transparent, but possessive agreement inside and case marking outside the embedded clause clearly indicate that it is nominalized (29a). To see this, compare (29a) with root embedding in (29b), which is also grammatical under certain matrix predicates, potentially with an accusative-marked embedded subject.

| (29) | a. | Biz kedi-nin su iç-tiğ-in-i san-ıyor-uz. |

| we cat-gen water drink-nomin-poss3sg-acc think-pres-1pl | ||

| ‘We think that the cat is drinking water.’ | ||

| b. | Biz kedi(-yi) su iç-iyor san-ıyor-uz. | |

| we cat-acc water drink-pres think-pres-1pl | ||

| ‘We think the cat is drinking water.’ |

It has been known since Kornfilt (1984) that some embedded clauses in Turkish are transparent to licensing by matrix negation, while others are opaque. Kelepir (2001) shows that the complement clauses of a set of verbs, including neg-raising verbs (30), perception verbs (31), and attitude verbs (32), are transparent to the long-distance licensing of hiç-expressions. However, factive verbs introduce opaque domains (33). The same holds for root embeddings (34).12

| (30) | Biz kedi-nin hiçbir şey iç-tiğ-in-i/-e |

| We cat-gen n-one thing drink-nomin-poss3sg-acc/-dat | |

| san-m-ıyor-uz/inan-m-ıyor-uz. | |

| think-neg-pres-1pl/believe-neg-pres-1pl | |

| ‘We don’t think/believe that the cat is drinking anything.’ |

| (31) | Biz kedi-nin hiçbir şey iç-tiğ-in-i |

| we cat-gen n-one thing drink-nomin-poss3sg-acc | |

| gör-me-di-k/duy-ma-dı-k. | |

| see-neg-past-1pl/hear-neg-past-1pl | |

| ‘We didn’t see/hear the cat drink anything.’ |

| (32) | Biz kedi-nin hiçbir şey iç-me-sin-i |

| We cat-gen n-one thing drink-nomin-poss3sg-acc | |

| iste-m-iyor-uz/onayla-m-ıyor-uz. | |

| want-neg-pres-1pl/approve-neg-pres-1pl | |

| ‘We don’t want the cat to drink anything.’ | |

| ‘We don’t approve of the cat’s drinking anything.’ |

| (33) | *Biz kedi-nin hiçbir şey iç-tiğ-in-i |

| we cat-gen n-one thing drink-nomin-poss3sg-acc | |

| öğren-me-di-k/bil-m-iyor-uz. | |

| learn-neg-past-1pl/know-neg-pres-1pl | |

| ‘*We didn’t find out that the cat was drinking anything.’ | |

| ‘*We don’t know that the cat is drinking anything.’ |

| (34) | ?*Biz kedi(-yi) hiçbir şey iç-ti san-m-ıyor-uz. |

| We cat-acc n-one thing drink-past think-neg-pres-1pl | |

| ‘We don’t think the cat drank anything.’ |

We may add that complement clauses of reportative verbs, which are neither neg-raising nor factive, are also transparent to NC.

| (35) | Biz kedi-nin hiçbir şey iç-tiğ-in-i |

| we cat-gen n-one thing drink-nomin-poss3sg-acc | |

| söyle-m-iyor-uz/iddia et-m-iyor-uz. | |

| say-neg-pres-1pl/claim do-neg-pres-1pl | |

| ‘We are not saying/claiming that the cat is drinking anything.’ |

Locality domains such as adjunct islands still create opaque domains for NC, though, for reasons not properly understood by us, in certain adjuncts hiç-items may appear. (36) provides two examples under the same adverbial clause with differing acceptability.

| (36) | a. | *Ahmet hiçbir yer-e git-sin diye para kazan-m-ıyor-uz. |

| Ahmet n-one place-dat go-opt so.that money earn-neg-pres-1pl | ||

| (‘We do not earn money so that Ahmet travels anywhere.’) | ||

| b. | Hiçkimse onayla-sın diye çalış-m-ıyor-uz. | |

| n-body approve-opt so.that work-neg-pres-1pl | ||

| ‘We aren’t working so that anybody approves.’ |

This short review suggests that long-distance licensing of NC is the rule rather than the exception in Turkish. We leave it to future research to explore why this may be the case and what may connect factive domains, root embedding, and certain adverbial clauses in their inability to license long-distance NC.

2.5. Are Turkish Neg-Words Universals or Existentials?

One of the central questions in the domain of neg-words and NPIs concerns whether neg-words/NPIs are universals or indefinites/existentials. NPIs are widely considered to be existentials licensed under a licensing operator such as negation (starting with Ladusaw 1979). However, it is also possible that they are universals obligatorily outscoping negation. This possibility arises because it is normally impossible to tease apart the narrow scope existential constellation ¬ > ∃ from the wide scope universal constellation ∀ > ¬, as the two are truth-conditionally equivalent (37) (see Giannakidou 2000; Shimoyama 2011).

| (37) | Sue didn’t meet anybody. |

| ¬∃x.[Human(x) & Meet(s,x)] | |

| ∀x.[Human(x) →¬Meet(s,x)] |

In the domain of neg-words, Ladusaw (1992) and Zeijlstra (2004) assume the existential analysis, whereas Szabolcsi (1984) and Giannakidou (2000) make a case for the universal analysis. Shimoyama (2011) has argued that Japanese NPIs are universals, but as Shimoyama’s primary data are argued to be neg-words by others (Watanabe 2004 a.o.), we assume her analysis to be applicable to neg-words.

Giannakidou (2000, 2006) proposes a set of diagnostics, such as modification by almost/absolutely, the inability to bind donkey-pronouns, and the absence of neg-words in predicate nominals, to distinguish universals from existentials. For instance, I saw almost somebody is strongly degraded, while I saw almost everybody is fine. Also, universals, unlike existentials, do not bind donkey anaphora: The students that have {somethingi/anythingi/*nothingi/*everythingi} to say should say iti now. Similarly, universals cannot appear in predicate nominals, but existentials can: Mary is {a/*every} doctor. Then, she shows that neg-words in Greek pattern with universals like every x and not with existentials like some x in English in these respects, indicating that they must be universals.

Shimoyama (2011) introduces fixed scope quantificational elements into the picture to sidestep the equivalence illustrated in (37). Suppose Q+ is a scope-taking element that outscopes negation. With such an element, only universal NPIs can give rise to the scope construal ∀ > Q+ > ¬, because this construal is not equivalent to any construal involving Q+, ¬ and ∃. By contrast, with Q−, a scope-taking element that takes scope below negation, only existential/indefinite NPIs can give rise to the scope construal ¬ > Q− > ∃, as it is not equivalent to any construal involving ¬, Q− and ∀.

Shimoyama then tests the quantificational status of Japanese NPIs based on examples like (38). The adverb hudan ‘usually’ is a Q+ adverb: it has to outscope negation. With the neg-word dare-mo in the subject position, we observe the decisive reading ∀ > Q+ > ¬, which indicates that the neg-word is a universal.13 The reading Q+ > ¬ > ∃ (or the equivalent Q+ > ∀ > ¬) may be present as well, but this reading is uninformative exactly because it has existential and universal equivalents.

| (38) | Nihonzin gakusei-no dare-mo hudan(-wa)/taitei sankasi-nakat-ta. |

| Japanese student-gen n-body usually-top/mostly participate-neg-past | |

| ‘For every Japanese student, it was usually the case that they did not participate.’ |

On the flipside, the construal ¬ > Q− > ∃ would constitute evidence for the existential analysis. To demonstrate the quantificational status of an NPI unequivocally, one must test this diagnostic reading too, this time with a Q− adverb.

Now, we first check the quantificational status of Turkish her-expressions based on Giannakidou’s diagnostics (Giannakidou 2000, 2006). Here, we apply two tests: modification with almost and the occurrence of predicate nominals. The test involving donkey anaphora cannot be applied to Turkish as these require relative clauses where neg-words are independently banned in Turkish. Other diagnostics by Giannakidou are more language-specific and only hold for Greek or are no longer theoretically up to date (in the case of diagnostics based on syntactic locality14 or existential commitment15). The two diagnostics we apply below point in the direction of neg-words being universals:

| (39) | a. | Hemen hemen hiçbir öğrenci ders-e gel-me-di. |

| almost n-one student class-dat come-neg-past | ||

| ‘Almost no student came to class.’ | ||

| b. | *Leyla hiçbir doktor değil. | |

| Leyla n-one doctor not | ||

| (‘Leyla is no doctor.’) |

As seen, in Turkish, the neg-word may be modified by almost and may not appear in a predicate nominal. These are universal-like characteristics: every can also be modified by almost and cannot appear in a predicate nominal, whereas the facts are reversed for the existential some. Hence, these data would suggest that Turkish neg-words are universals.16

Next, let us look at Shimoyama’s diagnostics. Turkish and Japanese share important morphosyntactic features such as SOV constituent order and wh-in-situ, in addition to being Strict NC languages. In the context of this discussion, a particularly relevant parallelism is the relative scope between the subject position and negation. In Korean and partly also Japanese, the subject position is typically interpreted outside of the scope of negation (Shimoyama 2011). Turkish has this feature as well. Consider (40). If we have a class of ten students and three of them skipped class, this sentence can be truthfully uttered, indicating that the subject outscopes negation. In the reading where the subject takes scope under negation, seven to ten students are said to have skipped class, where (40) would not be a true statement.17

| (40) | Üç veya daha fazla öğrenci ders-e gel-me-di. | |

| three or more many student class-dat come-neg-past | ||

| ‘For three or more students, they did not come to class.’ | 3 or more > ¬ | |

| ??’It is not the case that three or more students came to class.’ | ??¬ > 3 or more |

According to Shimoyama, if the subject position typically outscopes negation, there is reason to suspect that a subject neg-word may be outscoping negation as well. Structures with a neg-word subject should then potentially yield a reading with a universal outscoping negation (∀ > ¬), as Shimoyama claims to be the case in Japanese, and not a reading with an existential under the scope of negation (¬ > ∃).

Let us then see what Shimoyama’s tests for neg-words reveal for Turkish hiç-expressions. Turkish also has quantificational adverbs with a preferred Q+ (Q > ¬) reading such as çoğu zaman ‘mostly’, just like the Japanese hudan. The reading where the adverb scopes under negation requires untypical prosody if at all possible (see Note 17).

| (41) | Ahmet çoğu zaman bisiklet-e bin-m-iyor. | |

| Ahmet most times bicycle-dat ride-neg-pres | ||

| ‘Ahmet doesn’t ride a bike most of the time.’ | mostly > ¬ | |

| ??‘It is not most of the time that Ahmet rides a bike.’ | ??¬ > mostly |

In the Japanese examples considered by Shimoyama, the negative element in the subject position scopes over the quantificational adverb, hence automatically over the negation that the adverb scopes over, leading to the ∀ > Q+ > ¬ reading that provides evidence for the high scope universal analysis.

In Turkish, we do not find this to be the case. (42), which now has a neg-word subject, is marginally acceptable to begin with, and in the allowed prosody (to the extent that it could be controlled), the critical ∀ > Q > ¬ reading is absent.18

| (42) | ??Hiçbir komşu-m çoğu zaman bisiklet-e bin-m-iyor. | |

| n-one neighbor-poss1sg most times bicycle-dat ride-neg-pres | ||

| ??‘No neighbor of mine rides a bike most of the time.’ | ??¬ > ∃ > Q | |

| Not: ‘For all my neighbors, most of the time they do not ride a bike.’ | *∀ > Q > ¬ |

On the flipside, an adverb that supports a Q− (¬ > Q) reading can provide evidence for the narrow scope existential analysis by providing (or failing to provide) the decisive construal ¬ > Q > ∃. One such adverb in Turkish is çok ‘much’.

| (43) | Ahmet çok ye-me-di. | |

| Ahmet much eat-neg-past | ||

| ‘Ahmet didn’t eat much.’ | ¬ > Q | |

| ??‘There is much Ahmet didn’t eat.’ | ??Q > ¬ |

Now, with a neg-word subject, if we get a ¬ > Q− > ∃ construal, then we can safely conclude that the neg-word has an existential interpretation. As shown in (44), this reading is indeed available (in addition to the non-decisive ¬ > ∃ > Q−).

| (44) | Hiçkimse çok ye-me-di. | |

| N-body much eat-neg-past | ||

| ?‘It’s not much that was eaten.’ | ?¬ > Q > ∃ |

So, based on Shimoyama’s tests, scope-sensitive quantificational adverbs in Turkish provide evidence for the existential analysis and not for the universal analysis: they do not allow the ∀ > Q > ¬ reading (with Q+ elements) that would be evidence for the universal analysis. In fact, they allow the ¬ > Q > ∃ reading (with Q− elements), which is evidence for the existential analysis.

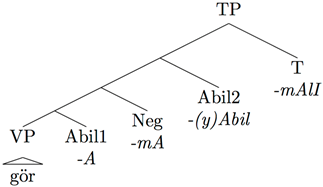

Let us also test this with modals. Just like adverbials, modals can be employed as the disambiguating Q element in these tests. As we will see in detail in Section 4, this is a particularly clear test because Turkish modals always take fixed scope with respect to negation, leading to unambiguous scope construals. Below, what we gloss as abil1 is a Q− element, as it has to scope below negation (45a). Abil2, on the other hand, has to scope above negation (45b).19

| (45) | a. | Dans ed-e-me-z-sin. | |

| dance do-abil1-neg-aor-2sg | |||

| ‘You may not dance.’ | ¬ > ◊/*◊ > ¬ | ||

| b. | Dans et-me-yebil-ir-sin. | ||

| dance do-neg-abil2-aor-2sg | |||

| ‘You are allowed not to dance.’ | ◊ > ¬/*¬ > ◊ |

Now, let us take the two instances of existential modal in (45a–b) for our test. If the Q− modal leads to a ¬ > ◊ > ∃ reading with a neg-word subject, this is evidence for a narrow scope existential analysis of the neg-word. Indeed, we do find this evidence. This sentence is ambiguous between a total prohibition and an individual prohibition reading, the first of which exemplifies the diagnostic configuration.

| (46) | Hiçkimse dans ed-e-me-z. | |

| n-body dance do-abil1-neg-aor | ||

| ‘Nobody may dance.’ | ¬ > ◊ > ∃ | |

| ?‘There is no particular individual who may dance. (Mary because her knee is injured, John because he is grounded, etc.)’ | ?¬ > ∃ > ◊ = ∀ > ¬ > ◊ |

If, on the other hand, the Q+ modal abil2 leads to a ∀ > ◊ > ¬ reading with a neg-word subject, this would be evidence for a wide scope universal analysis of the neg-word. However, this reading is marginal if at all acceptable. The sentence has the total permission reading, and not a reading where for each individual there is separate permission granted not to dance.

| (47) | Hiçkimse dans et-me-yebil-ir. | |

| n-body dance do-neg-abil2-aor | ||

| ‘It is permitted that nobody dances.’ | ◊ > ∀ > ¬ = ◊ > ¬ > ∃ | |

| ??‘Each is individually permitted not to dance.’ | ??∀ > ◊ > ¬ |

Hence, the data on modals and quantificational adverbs converge. Shimoyama’s wide scope universal analysis of Japanese negative elements is not tenable for Turkish neg-words. According to these tests, Turkish neg-words behave like existentials.

At this stage, the results are conflicting. Giannakidou’s diagnostics point in the direction of Turkish hiç-expressions being universals; Shimoyama’s, in the direction of existentials. We can therefore not draw a safe conclusion here, though Penka (2011) and Gajić (2016) have argued that some of Giannakidou’s diagnostics for a universal analysis, for instance, almost-modification, are also possible in languages where neg-words are clearly existential (e.g., Italian or Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian), casting doubt on the validity of this test.

2.6. Summing Up

To sum up, we have argued that hiç-expressions in Turkish are neg-words and are licensed strictly under NC. They are thus separated from minimizer NPIs, which have a broader distribution. The domain of NC includes complex clauses with a non-factive matrix predicate and polar questions with verbal attachment of the question clitic, both of which point to points of variation deserving further investigation. In terms of their meaning, unlike the comparable class of negative elements in Japanese, Turkish neg-words do not present any evidence for Shimoyama’s (2011) analysis of these elements as wide scope universals but violate some of the diagnostics for existentials by Giannakidou (2000, 2006) as well.

3. Narrow Scope Universals and the Non-Entailment-of-Non-Existence Condition

The second negative dependency we inspect on the basis of data from Turkish is a crosslinguistically relatively uncommon negative dependency: universals that take obligatory narrow scope with respect to negation.

3.1. Turkish Universals and Negation

Turkish has three forms denoting universal quantification over individuals: bütün/tüm (the two are fully equivalent), her, and hep-. All of these forms can occur in affirmative sentences; hence, they are not NPIs (or neg-words) in the standard sense, but neither of them can outscope negation in negative clauses (see Kelepir 2001; Öztürk 2005; Özyıldız 2017 a.o.). (48–50) exemplify these forms in affirmative and negative sentences. The (a) examples show that they are fine without negation. The (b) examples illustrate that in the presence of negation, the interpretation is one of partial negation and not total negation, that is, the universals scope below negation.20

| (48) | a. | Her öğrenci gel-ir. | |

| every student come-aor | |||

| ‘Every student comes.’ | |||

| b. | Her öğrenci gel-me-z. | ||

| every student come-neg-aor | |||

| ‘Not every student comes.’ | |||

| Not: ‘No student comes.’ | ¬ > ∀; *∀ > ¬ |

| (49) | a. | Bütün/tüm öğrenci-ler gel-ir. | |

| all student-pl come-aor | |||

| ‘All students come.’ | |||

| b. | Bütün/tüm öğrenci-ler gel-me-z. | ||

| all student-pl come-neg-aor | |||

| ‘Not all students come.’ | |||

| Not: ‘No student comes.’ | ¬ > ∀; *∀ > ¬ |

| (50) | a. | Hep-si gel-ir. | |

| all-poss3sg come-aor | |||

| ‘All of them come.’ | |||

| b. | Hep-si gel-me-z. | ||

| all-poss3sg come-neg-aor | |||

| ‘Not all of them come.’ | |||

| Not: ‘None of them comes.’ | ¬ > ∀; *∀ > ¬ |

In the rest of this section, we focus on her (48). Combining with singular nominals and not requiring a possessive construction, this form is morphologically simpler and hence more akin to English every. Also, her is noted to be rather distributive, unlike bütün (Kelepir 2001; Özyıldız 2017). This feature of her makes for a particularly compelling illustration of the narrow scope requirement of Turkish universals with respect to negation, as its default tendency is outscoping rather than underscoping other quantificational elements.

What could be the source of this rare scope requirement of the universals in Turkish? To our knowledge, neither universals nor negation are restricted in their scope potential on their own in Turkish, so this requirement is observed only when universals and negation occur together. Turkish is generally taken to be scope-rigid; hence, universal subjects can and do scope over object quantifiers (Zidani-Eroğlu 1997; Kelepir 2001; Özyıldız 2017; Demirok 2021 a.o.). Also, with respect to modals, which are verbal suffixes like negation, universal subjects may take ambiguous scope (51).

| (51) | Her öğrenci maç-ı izle-yebil-ir. | |

| every student game-acc watch-abil-aor | ||

| ‘Every student may watch the game.’ | ||

| i. | ◊ > ∀: It is permitted that the entire student population watches the game (hence classes are canceled). | |

| ii. | ∀ > ◊: Each student is individually permitted to watch the game (e.g., by their parents. Classes take place as usual). | |

The scope of negation is similarly flexible. Most notably, negation may scope over or below quantifiers such as many and numerals in the subject position (52). Unlike with universals, these structures even present a slight dispreference for the narrow scope reading (which improves under the compressed prosody mentioned in Note 17).

| (52) | Birçok/birkaç/beş öğrenci gel-me-di. | |

| many/a few/five student come-neg-past | ||

| ‘Many/a few/five students did not come.’ | ||

| iii. | Many/a few/five > ¬: Many/a few/five students are such that they did not come. | |

| iv. | ¬ > many/a few/five: It is not the case that many/a few/five students came. | |

A potential explanation for such restricted scope behavior is polarity sensitivity. Indeed, Turkish universals are a bit like NPIs: they scope below negation in the presence of negation. However, the similarity ends there, as these elements are not licensed by negation. On the other hand, another class of familiar polarity-sensitive elements, Positive Polarity Items, act similar to Turkish universals: they must scope in a certain way alongside negation, but their presence does not hinge on the presence of negation. We illustrate this in (53) with English some as well as Turkish bazı, shown to be a PPI by Kelepir (2001).

| (53) | a. | Bazı öğrenci-ler gel-di. | |

| some student-pl come-past | |||

| ‘Some students came.’ | |||

| b. | Bazı öğrenci-ler gel-me-di. | ||

| some student-pl come-neg-past | |||

| ‘Some students are such that they did not come.’ | |||

| Not: ‘There are no students who came.’ | ∃ > ¬; *¬ > ∃ |

English PPIs outscope negation in most contexts (Szabolsci 2004), which is also the case with the Turkish PPI bazı ‘some’ (Kelepir 2001) (53b). The universals we are dealing with must scope below negation. However, in both cases, the resulting interpretation cannot be one of total negation. In combination with restricted scope with respect to negation while not requiring it, one might say that Turkish universals act as the mirror image of standard PPIs of English.

We will outline an account below following this lead. We propose addressing the narrow scope behavior of Turkish universals in terms of polarity sensitivity and connecting these NPI-like and PPI-like characteristics under one principle. In this account, the obligatory narrow scope of Turkish universals points to a novel kind of negative dependency. The source of this polarity sensitivity is a referentiality requirement that essentially bans readings with total negation. It affects existentials and universals alike, turning the former into PPIs and the latter into Turkish-type non-standard NPIs. In this way, the unusual scope behavior of Turkish universals not only receives an explanation but also possibly provides an important missing piece of the puzzle of types of polarity sensitivity.

3.2. The Non-Entailment-of-Non-Existence Condition

We take as a starting point a prominent analysis of NPIs that are licensed in all NV contexts (“broad NPIs” according to Giannakidou 2006, “superweak NPIs” according to Zeijlstra 2022). Unlike a weak NPI such as English any, superweak NPIs are grammatical in all non-veridical contexts, including modal contexts. An example of such an NPI is Mandarin shenme ‘what, any’, which is licensed under certain modals (54a) and negation (54b) (cf. Lin 1998 for more discussion and examples).

| (54) | a. | Mali zuotian *(haoxiang) mai-le shenme shu. | |

| Mary yesterday probably bought-perf what book | |||

| ‘Mary has probably bought a book yesterday.’ | |||

| b. | Mali zuotian *(mei) mai shenme shu. | ||

| Mary yesterday neg bought what book | |||

| ‘Mary didn’t buy any book yesterday.’ | (Lin 1998) |

Lin’s (1996, 1998) explanation for the source of this kind of NPI-hood is the lexically encoded Non-Entailment-of-Existence Condition (NEEC), similar to what Giannakidou (2011) dubs referential deficiency. In this framework, certain elements may not appear in contexts that would entail the existence of a referent satisfying their description, where such contexts are formed by the proposition whose widest scope operator is a scope operator that the NPI is in the scope of. This means the sentences in (54) with the modal or negation are fine because the existence of a book bought yesterday by Mary is not entailed. If the modal or negation is absent, the sentence becomes ungrammatical, as the sentence would then entail that there is a book bought yesterday by Mary, which violates NEEC.

In the same vein, Giannakidou (1998, 2011) argues that NPIs sensitive to non-veridicality (i.e., NPIs that, unlike any or ever, are licensed by all NV operators, not just by DE ones) are NPIs because they are referentially deficient in the sense that they cannot give rise to an existentiality entailment.

As a next step, we would like to argue that the reverse of Lin’s Non-Entailment-of-Existence Condition, a lexically encoded condition we dub the Non-Entailment-of-Non-Existence Condition (NENEC), also has grammatical reality. Elements sensitive to NENEC should not appear in contexts that would entail the non-existence of referents satisfying their description, where such contexts are formed by the proposition whose widest scope operator is a scope operator that they are in the scope of. An element sensitive to NENEC would thus display polarity sensitivity that bans it from contexts where its non-existence is entailed.

English-type PPIs, we would argue, are prime examples of NENEC-sensitive elements. Empirically, an expression like the English existential some is a PPI because it must scope over negation (e.g., nobody) and not under it. Hence, (55) means ‘there is a book that nobody read’, not ‘nobody read a (certain) book’.

| (55) | Nobody read some book. | ∃ > nobody; *nobody > ∃ |

Under NENEC, the reason that (55) does not allow a reading with a scope construal nobody>some is that its assertion under this scope construal would entail that there is no book read by anybody (¬ > ∃). This violates NENEC, which forbids negating the existence of such books. When the scope construal is reversed (∃ > ¬), it is asserted that there is a book read by nobody, which no longer violates NENEC. Thus, PPIs like some cannot take scope below elements that negate the existential import they can make. Hence, these PPIs are predicted to be banned under negation and negative quantifiers like nobody, i.e., they are banned in anti-additive contexts.

In this line of thinking, we would expect existential PPIs to scope freely under or over DE elements that are not anti-additive or anti-veridical, because these block the existential import in neither construal. In (56), under both construals, there can be books read by few or at most three students: either there are few/at most three students who read some book (few/at most 3 > ∃;), or some book is read by few/at most three students (∃ > few/at most three).21 In neither case is the non-existence of such books entailed. In fact, the presence of such students/books is inferred.

| (56) | a. | Few students read some book. | few > ∃; ∃ > few |

| b. | At most three students read some book. | at most 3 > ∃; ∃ > at most 3 |

Thus, under NENEC, English-type existential PPIs are predicted to be so-called weak PPIs: PPIs that are only anti-licensed under anti-additivity and not under other downward-entailing contexts, a prediction that, to the best of our knowledge, is borne out. This makes NENEC a viable source of polarity sensitivity, which we, in turn, use to approach the peculiar behavior of Turkish universals.

3.3. Turkish Universals as Universal NPIs Mirroring PPIs

To see how NENEC applies to Turkish, let us first look at PPIs like bazı ‘some’. We have already seen in (53) that bazı is a PPI, so it may be hypothesized that bazı is subject to NENEC: staying under negation would entail the non-existence of referents satisfying its description (students who came), so it has to scope above negation.

PPIs subject to NENEC should only be sensitive to negation, as only negation leads to the offending non-existence entailment; hence, they must be weak PPIs like the English some. Let us see if bazı is a weak PPI. We test this with the non-anti-additive elements exemplified in (56). We use a dative-assigning verb to stay clear of the widely discussed added semantic effects of overt accusative on our object with bazı (Enç 1991 among many others), but plural marking is inescapable.

| (57) | a. | Birkaç/az sayıda öğrenci bazı sınav-lar-a gir-di.22 | |||

| a.few few in.number student some exam-pl-dat enter-past | |||||

| ‘Few students took some exams.’ | few > ∃; ∃ > few | ||||

| b. | En fazla üç öğrenci bazı sınav-lar-a gir-di. | ||||

| most many three student some exam-pl-dat enter-past | |||||

| ‘At most three students took some exams.’ | at most 3 > ∃; ∃ > at most 3 | ||||

In both (57a) and (57b) in Turkish, we see a scope ambiguity similar to English. These sentences may both mean that few/at most three students took a number of exams (few/at most 3 > ∃), or that certain exams were taken (only) by few/at most three students (∃ > few/at most 3).23 The presence of the first reading, where bazı scopes under few/at most n (while being unable to scope under negation), suggests that bazı is a weak PPI whose polarity sensitivity can be accounted for by NENEC.

English some and Turkish bazı are, as widely assumed for all PPIs, existentials. Hence, if the PPI is under negation, we get a ¬ > ∃ constellation which leads to a non-existence entailment. What if the polarity item were a universal? If that were the case, the ∀ > ¬ reading, which means total negation, would cause a non-existence entailment. If this polarity item were subject to NENEC, it would then be forced to take scope under negation in the partial negation constellation ¬ > ∀. This would make that item an NPI (scoping under negation) with no requirements to occur with negation. Could a universal be an NPI? Polarity items have, until recently, been assumed to consist of existentials only, but this assumption is challenged by Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2013) and Zeijlstra (2017), who argue for universal PPIs in the domain of modals and individuals, respectively. So, such a universal NPI subject to NENEC is possible to imagine.

As the keen reader can see, we propose that Turkish universals are exactly those universal NPIs subject to NENEC. Take (48)–(50) again. Under the surface reading ∀ > ¬, it would be entailed that there are no students that came, which violates NENEC. The inverse scope reading ¬ > ∀, where not all students came, does not violate NENEC, and hence is the only available reading. For this reason, Turkish universal quantifiers display a novel type of negative dependency. Just like weak PPIs, they are subject to NENEC, and therefore must scope under negation when negation is present. If negation is absent, NENEC is trivially satisfied. No negative existential commitment is made when somebody utters that all students came.24

As expected under this account, just like their existential PPI counterparts, Turkish universals are only sensitive to anti-additivity. When they appear above a non-anti-additive downward-entailing operator, a surface scope reading should be available, and indeed it is:

| (58) | Her öğrenci birkaç/az sayıda sınav-a gir-di. | |

| every student a.few/few in.number exam-dat enter-past | ||

| ‘Every student took few exams.’ | ∀ > few | |

Further evidence comes from overt accusative case on direct objects with a universal. It is a well-known fact in Turkish that overt accusative case is obligatory on direct objects that are specific nominals, such as proper names and demonstratives (Enç 1991). Mysteriously, the same holds for direct objects with universal quantifiers (59), even though they do not show the same discourse saliency as other accusative-requiring nominals.

| (59) | Selma her öğrenci*(-yi) gör-dü. |

| Selma every student-acc see-past | |

| ‘Selma saw every student.’ |

Our proposal is in line with this specificity-like behavior of universals. Given that specificity requires an existential commitment, it is not surprising that universal quantifiers that are subject to NENEC pattern with proper names and demonstratives.

3.4. On the Syntactic Source of Narrow Scope Universals

Before closing this section, we would like to briefly discuss how the narrow scope behavior of Turkish universals may be represented in the syntax. Do they occupy a position under negation in surface syntax, or do they reconstruct? How are they different from other subjects in this respect?

It has been observed, at least since Kornfilt (1984), that subjects in Turkish may show characteristics in line with a syntactic position lower than the canonical subject position in Spec, TP. For Öztürk (2005), whose analysis is partly motivated by narrow scope universals, subjects stay inside vP unless they are optionally raised, such as in cases of topicalization. Hence, data like (60) receive a simple explanation.

| (60) | a. | Her öğrenci sıklıkla depresyon-a gir-er. |

| every student frequently depression-dat enter-aor | ||

| ‘Every student becomes depressed frequently.’ | ||

| b. | Sıklıkla her öğrenci depresyon-a gir-er. | |

| frequently depression-dat enter-aor | ||

| ‘Frequently every student becomes depressed.’ |

In (60), the frequency adverb sıklıkla ‘frequently’ can either precede or follow the universal subject and take scope accordingly. If subjects were always placed in Spec, TP, one would expect this adverb to always follow the subject or exhibit some markedness when it precedes the subject, contrary to fact. Furthermore, according to Şener (2010), Japanese-style scrambling also cannot be an option to derive the two surface orders with accompanying scope construals. If subjects typically stay in vP in Turkish, then the narrow scope of the universals would be accounted for.

A second option is to assume that the subject raises to TP but reconstructs to vP at LF. Reconstruction lends itself well to phenomena involving an ambiguity between surface and inverse scope. In such an account, if an element only has a scope reading associated with its higher surface position, this would mean that the item may not reconstruct. This would be the case for PPIs. If an element only has a reading associated with its low base position, then this would indicate that this item must obligatorily reconstruct. Items for which two scope construals are available are said to be free to reconstruct. In this way, a uniform syntactic mechanism may be used to address various scope behaviors. Additionally, one may argue that a semantic constraint such as NENEC must be accessible at LF once all narrow syntactic computation is completed, rather than at first merge. It has been argued, in particular, that the violation of polarity sensitivity requirements makes LF target lower copies (i.e., leads to reconstruction) (Iatridou and Zeijlstra 2013). Moreover, reconstruction would be in line with the generally accepted relationship between case and agreement, both of which Turkish marks overtly and involves the canonical subject position in Spec, TP (cf. Baker 2008; though see Preminger 2011 for an exception in Basque).25

In this section, we have mainly focused on why Turkish universals scope below negation and not how. As far as the facts of scope-taking are concerned, both accounts could, in principle, be adopted: to be interpreted under negation, the universal subject could be staying in vP or reconstructing to vP. However, let us note that data indicating variable scoping from the subject position, such as (40), (51), and (52), are more in line with the reconstruction approach, as they reveal that both vP and TP are positions where the subject quantifier may take scope. Moreover, we have noted for these cases that the preferred reading is one where the quantifier takes scope over negation, which would mean that under approaches like Öztürk’s, some quantifiers must routinely topicalize, begging the question why.

3.5. Summing Up

In this section, we have demonstrated that Turkish universals must scope below negation, unlike other quantifiers, which constitutes a case of non-standard NPI-hood. We have argued that once it is assumed that universals, like Turkish her, as well as existential PPIs, such as English some and Turkish bazı, are subject to the Non-Entailment-of-Non-Existence Condition we are proposing, their scope behavior is readily accounted for. Hence, such universals show an NPI-like scope construal with respect to negation without requiring negation. This approach not only uncovers a seemingly rare kind of negative dependency of universal quantifiers but, if the account sketched is on the right track, also points to a parallelism between such universals and existential PPIs as mirror images of one another.

4. Modal Morphemes and Polarity Sensitivity

The third and last instance of negative dependency we will consider, based on Turkish, is an apparent dependency that holds between negation and modals where certain modals are interpreted over negation and some under it. On the face of it, obligatory scope-taking with respect to negation may be a case of polarity sensitivity in the domain of modals, as Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2010, 2013) argue.

4.1. The Verbal Complex in Turkish: Modals and Negation

In agglutinative Turkish, negation and tense-aspect-modality (TAM) morphemes are verbal suffixes. The head-final verbal morphological complex, based on a single verb stem, may include as many as four TAM suffixes (see Kornfilt 1996; Kelepir 2001 for syntactic underpinnings). (61) exemplifies a rich verbal complex with negation and three modal expressions, as well as additional tense.

| (61) | Oya ekran-ı gör-e-me-yebil-meli-y-di. |

| Oya screen-acc see-abil1-neg-abil2-nec-cop-past | |

| ‘Oya should have had permission not to be able to see the screen.’ |

As the translation suggests, all TAM suffixes are ordered in a way that reflects their scope: an outer (rightward) position means higher scope (Kelepir 2001 and references therein, Cinque 2001 for a cartographic proposal; but see Göksel 1997 for arguments against such a view). The negative morpheme –mA itself occupies a strict slot, where it is lower than all TAM positions but one. As seen in (61), three slots in the verbal complex are available to modality. Indeed, all three modal positions take scope in line with their linear order, as we briefly saw in Section 2.5.

Zooming in on modals, we see in (62) that the universal modal, the necessitative –mAlI, is outside of and outscopes the existential modal, the abilitative –Abil.26

| (62) | Oya gör-ebil-meli. | |

| Oya see-abil-nec | ||

| ‘Oya must be able to see.’ | □ > ◊; *◊ > □ |

This scope rigidity persists in interactions with negation. The universal modal appears in a slot outside of the negative morpheme and takes scope over it.27

| (63) | gör-me-meli | |

| see-neg-nec | ||

| ‘must not see’ | □ > ¬; *¬ > □ |

For existential modality, there are two slots: to the left of negation, we see the suffix –A, and to the right of negation, we see –Abil. In both cases, scope continues to follow the linear order of the suffixes (64). We gloss these as abil1 and abil2, respectively, to highlight their position with respect to negation. Note that the negation of the ability reading of –A in (64a) is familiar, but the ‘permission not to’ (◊ > ¬) reading realized by –Abil in (64b) cannot be expressed with the existential modals in more widely studied languages, such as English may and can (unless a particular prosody is employed; see Iatridou and Zeijlstra 2013).

| (64) | a. | gör-e-me-z | |

| see-abil1-neg-aor | |||

| ‘may not see’ | ¬ > ◊; *◊ > ¬ | ||

| b. | gör-me-yebil-ir | ||

| see-neg-abil2-aor | |||

| ‘is allowed not to see’ | ◊ > ¬; *¬ > ◊ |

As (63) and (64b) show, the universal modal –mAlI and the existential modal –Abil obligatorily scope over negation. This could potentially indicate that they are PPIs. Moreover, the existential –Abil scoping over negation instantiates a typologically uncommon pattern according to Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2010). Hence, we ask in this section if these Turkish modals are PPIs.

Conversely, the existential modal –A not only obligatorily takes scope below negation but also requires the presence of negation, creating a poorly understood gap in the paradigm (65a). When expressing the non-negated existential modal, the only available form is –Abil (65b).

| (65) | a. | *gör-e-r |

| see-abil1-aor | ||

| (‘may see’) | ||

| b. | gör-ebil-ir | |

| see-abil-aor | ||

| ‘may see’ |

We will hence ask if –A is an NPI and what such an analysis would entail for this paradigmatic gap and for the polarity sensitivity of existentials crosslinguistically.

Before moving on, let us clarify a few assumptions we make. While the non-negated existential form in (65b) appears to be identical to our abil2, its semantic import is that of abil1.28 This discrepancy creates the illusion that –A “turns into” –Abil, but the two forms are not related morphophonologically (at least in the synchronic grammar). We will address this issue under a simple proposal in this section. We start by making the straightforward assumption of two distinct modal morphemes representing these two distinct surface forms. To keep things simple, we will gloss an existential modal appearing without negation simply as “abil”.

Secondly, as (63) and (64b) show, the universal –mAlI and the existential –Abil obligatorily scope over negation. Regarding existential modals, it has been suggested that those with a deontic flavor (denoting permission) rarely (if ever) take high scope, but epistemic existential modals (denoting possibility) straightforwardly outscope other elements (Iatridou and Zeijlstra 2010; Zeijlstra 2022). All three Turkish modals we are addressing, including the uncommon high scope existential –Abil, have deontic readings (66). We hence base our observations on deontic readings where relevant, and use deontically flavored translations such as be allowed to reflect that.

| (66) | Ayakkabı-lar-ın-ı çıkar(-ma)-yabil-ir-sin. |

| shoe-pl-poss2sg-acc take.off-neg-abil(2)-aor-2sg | |

| ‘You are allowed (not) to take your shoes off.’ |

What is at the root of these scope interactions concerning the three Turkish modal morphemes and negation? As suggested in the literature, this behavior may follow from their position in the verbal complex and the underlying syntax. However, as we discussed, one could also consider the modals to be polarity-sensitive. The two approaches based on fixed morphosyntactic positions and polarity sensitivity are not mutually exclusive. Hence, we ask in this section if one can find traces of polarity sensitivity in the scope-sensitive behavior of Turkish modal suffixes.

4.2. Polarity-Sensitive Modals

As we have amply seen, a restriction to occur under negation could be an NPI characteristic. Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2013), following Van der Wouden (1994), argue that NPI modals do exist. Part of the reasoning is motivated by data like in (67), where some modals require the presence of negation and hence qualify as NPIs.

| (67) | Mary need*(n’t) leave. |

Other modals such as must and may take selective scope with respect to negation, as shown in (68). While must takes wide scope, (deontic) may takes narrow scope. However, there appears to be no reason for the English modals in (68a) and (68b) to take different scopes with respect to negation, while they syntactically appear in the same position in the surface form.

| (68) | a. | Mary must not leave. | □ > ¬ |

| b. | Mary may not leave. | ¬ > ◊ |

To account for these facts, Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2013) argue that some modals, like English must, are PPIs, and hence have to outscope negation. Evidence for this claim comes from tests indicating the PPI status of universal modals in English, Dutch, and Greek. We illustrate below with English must for simplicity.

As we saw in Section 3, standard PPIs such as English some scope over negation in simple contexts. But as documented extensively by Szabolcsi (2004), certain contexts alleviate this requirement. While in (69a) some girl has to scope over negation (as in, there is some girl Mary didn’t see), in (69b–d), someone can scope under negation (as in, it is not the case that John called someone). These rescue contexts are created by intervention (69b), and NPI-licensing contexts such as antecedents of conditionals (69c) and in combination with only (69d).29

| (69) | a. | Mary didn’t see some girl. | ∃ > ¬;*¬ > ∃ |

| b. | John didn’t call someone because he was lonely (but because he needed a lift). | ¬ > because > ∃ | |

| c. | If we don’t call someone, we are doomed. | if [¬ > ∃] | |

| d. | Only John didn’t call someone. | only > ¬ > ∃ |

Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2013) show that English universal modals that outscope negation like must do not only appear to be PPIs in simple contexts like (69a), but also show the same characteristic rescue effects in the environments in (69b–d). Below, the simple (70a) illustrates the typical high scope ‘requirement not to’ reading of the modal, whereas in (70c) and (70d), the reverse reading of ‘not required’ suddenly becomes available. In (70b), the reading is equivalent to ‘it is not because he is handsome that she must marry him’, where, again, necessity is not negated.

| (70) | a. | Mary mustn’t leave. | □ > ¬;*¬ > □ |

| b. | She must not marry him because he is handsome but because he is smart. | ¬ > because > □ | |

| c. | If he must not work tonight, he is allowed to go out with his girlfriend. | if [¬ > □] | |

| d. | Only John must not work tonight. | only > ¬ > □ |

A further argument establishing the PPI-hood of universal modals in English is that various modals exhibit different strengths of polarity sensitivity just like PPIs in the nominal domain. While strong PPIs are banned from all DE contexts, weaker PPIs are banned only from anti-additive contexts (see Van der Wouden 1994). We see in this respect that should is a strong PPI whereas must is a weaker PPI, as must can scope over at most n.

| (71) | a. | At most five boys must leave. | must > at most 5; at most 5 > must |

| b. | At most five boys should leave. | should > at most 5; *at most 5 > should |

Iatridou and Zeijlstra then propose a unified syntactic account of modals in English. All English modals merge as verbal heads and subsequently raise to the finite T where they are routinely realized. PPI modals do not normally reconstruct; therefore, they take surface scope over negation. Only in PPI rescue contexts do they reconstruct. In contrast, modals that are not PPIs, like may, occupy T in surface syntax but always reconstruct to their original position, hence scope below negation.

In English, Greek, and Spanish, there is an intriguing gap in the inventory of modals: while universal modals may be PPIs, existential modals are polarity-neutral in their deontic reading. This means that existentials always reconstruct to their base position. Another gap, which is less obvious due to the scarcity of NPI modals in general, like the universal need in (67), is the apparent absence of deontic existential modals that are NPIs. Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2010) observe these gaps and suggest that they are universal features of existential modals pending a systematic treatment.

4.3. Are Turkish Modal Morphemes Polarity-Sensitive?

In light of this discussion, let us see if the three Turkish modals can be taken to be polarity-sensitive. Recall that there are three forms of interest: the wide scope universal, the wide scope existential, and the narrow scope existential, none of which appear to take variable scope in normal circumstances.

The lower existential modal –A is a good candidate for an NPI modal because its presence hinges on the presence of negation, and it scopes below negation (64a). We know of no good reason to rule out this analysis. On the contrary, if it is true, it would provide an explanation for the paradigmatic gap we illustrated in (65). The morpheme –A is an NPI; hence, it cannot appear outside the scope of negation (65a). Thus, it can only be employed in ¬ > ◊ readings such as inability and prohibition (64a). –Abil, on the other hand, is the non-NPI existential modal. It is used to express existential modality outside the scope of negation: in affirmative sentences (65b) and scoping over negation (64b). However, when scoping over negation, the modal can only express readings of ability or permission to a negated prejacent (◊ > ¬), not a negation of ability (¬ > ◊) (cf. Note 28). To express this meaning, the modal –A has to be used. This is why it looks as if –Abil turns into –A when negated. The only remaining question is what stops –Abil from appearing under negation as well.

The existential –Abil, as well as the universal –mAlI, appear and scope above negation. This suggests that they may be PPIs. Moreover, if –Abil is a PPI, its failure to appear under negation would be explained, giving more credence to the suggestion we made in the previous paragraph about the existential modal paradigm. So, let us evaluate this possibility with tests of PPI-hood from Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2013).

We start with the universal –mAlI and test if the contexts given in (70) rescue the modal from its PPI-like scope restriction. Both the Turkish –mAlI and the English must are high scope universal modals, so they are maximally comparable.

However, the tests show that, unlike English must, the Turkish modal continues to express a requirement, outscoping negation (72). PPI rescue contexts do not have an effect on the scope construal. Based on this, –mAlI is not a PPI.

| (72) | a. | Gülfer dans et-me-meli. | |

| Gülfer dance do-neg-nec | |||

| ‘Gülfer must not dance.’ | □ > ¬;*¬ > □ | ||

| b. | Bu aday-a kadın ol-duğ-u için oy | ||

| this canditate-dat woman be-nomin-poss3sg because vote | |||

| ver-me-meli-sin. (Sicil-i sebebiyle | |||

| give-neg-nec-2sg record-poss3sg because.of | |||

| ver-meli-sin.) | |||

| give-nec-2sg | |||

| ‘You must not vote for this candidate because she is a woman. (You must do so because of her track record.)’ | □ > ¬ > because30 | ||

| c. | Bugün iş-e git-me-meli-yse-n bir gün daha | ||

| today work-dat go-neg-nec-cond-2sg one day more | |||

| dinlen-ir-sin. | |||

| rest-aor-2sg | |||

| ‘If you are required not to go to work today, you rest one more day.’ | if [□ > ¬] | ||

| d. | Sadece Bilgen iş-e git-me-meli. | ||

| only Bilgen work-dat go-neg-nec | |||

| ‘Only Bilgen is required not to go to work.’ | only > □ > ¬; □ > ¬ > only |

We do the same with the existential –Abil in (73). If the high scope behavior of –Abil is indicative of its PPI status, PPI rescue contexts should reverse its scope. Recall that English does not have an equivalent existential modal, so we rely on paraphrases.

| (73) | a. | Oya dans et-me-yebil-ir. | |

| Oya dance do-neg-abil2-aor | |||

| ‘Oya is allowed not to dance.’ | ◊ > ¬;*¬ > ◊ | ||

| b. | Bu aday-a kadın ol-duğ-u için oy | ||

| this canditate-dat woman be-nomin-poss3sg because vote | |||

| ver-me-yebil-ir-sin. (Ama sicil-i sebebiyle | |||

| give-neg-abil2-aor-2sg but record-poss3sg because.of | |||

| ver-me-n-i bekle-r-im.) | |||

| give-nomin-poss2sg-acc expect-aor-1sg | |||

| ‘You are allowed not to vote for this candidate because she is a woman. (But I would expect you to do so because of her track record.)’ | ◊ > ¬ > because31 | ||

| c. | Bugün iş-e git-me-yebil-ir-se-n bir gün daha | ||