Abstract

The current study investigated overregularization of Spanish irregular past participles (e.g., dicho ‘said’, regularized as decido) among 20 child heritage speakers of Spanish in New Mexico, ages 5;1–11;9. Overregularization occurs when a child produces an irregular form analogously to its regular counterpart (e.g., eated instead of ate). Typically, children first produce the irregular form and then, after they have learned a morphological pattern, they overapply it to the irregular form. Ultimately, children retreat from overregularization and once again produce the target irregular form. While there has been a wealth of studies on monolingual children’s overregularizations, very few have investigated this phenomenon in child heritage speakers, who may develop their grammars diversely due to their exposure to the heritage language. This study analyzed the impact of age, Spanish language experience, Spanish morphosyntax proficiency, and lexical frequency on overregularization among the 13/20 children who produced past participles (n = 233) in response to an elicited production task. Participles were overregularized at high rates (74%), resulting in forms like ponido (‘put’, cf: puesto). Results from a regression analysis indicate that overregularization was more likely among the younger children, the children with lower morphosyntax scores, and with lower-frequency participles. Further, an interaction between morphosyntax score and lexical frequency indicated that children with higher scores overregularized with lower frequency participles, but not higher frequency ones, whereas children with low scores overregularized with both low- and high-frequency forms. In summary, child heritage speakers overregularize Spanish past participles at high rates, and the retreat from overregularization is tied to overall grammatical development and lexical frequency, suggesting that the acquisition of irregular participles is dependent on experiencing multiple instances of the irregular verb form.

1. Introduction

The current study investigates child heritage speakers of Spanish and their development and overregularization of irregular past participles. Children overregularize these forms by relying on the dominant regular pattern in the language (Yang 2016), producing forms like escribido instead of escrito (‘written’). While overregularization has been widely studied in English, it has received less attention in languages with richer verbal morphology (Dąbrowska 2001; Kirjavainen et al. 2012; Saxton 2010). Moreover, many studies examining overregularization of Spanish have focused on monolingual speakers, leaving bilingual children unaccounted for. Child heritage speakers of Spanish provide an interesting case to examine and better understand children’s acquisition of morphology and the role of overregularization. Previous research demonstrates that their grammars develop uniquely and may differ from those of their age-matched monolingual counterparts. For example, compared to monolingual children, child heritage speakers of Spanish produce more gender mismatches inside the noun phrase (Cuza and Pérez-Tattam 2016; Montrul and Potowski 2007), as well as more gender mismatches between direct object clitics and the nouns they modify (Goebel-Mahrle and Shin 2020; Shin et al. 2023). They also omit direct objects altogether in contexts where other speakers would produce them overtly (e.g., ella abrió ‘she opened’) (Shin 2023), demonstrate an increased use of subject–verb word order in interrogatives (Cuza 2016), and show more variability in their use of the subjunctive (Dracos and Requena 2023). Importantly, child heritage speakers’ language development is closely related to their language experience. For example, the amount of exposure to Spanish has been shown to predict both gender matching and direct object expression (Shin 2023; Shin et al. 2023).

While there has been research on child heritage speakers’ acquisition of Spanish grammatical gender, direct object expression, word order, subjunctive mood, and other morphosyntactic phenomena, we still know little about their overregularization of morphology. The limited research to date has found that they overregularize some structures at higher rates and for longer timespans than do monolinguals (Baker 2022; Baker Martínez, forthcoming); Fernández-Dobao and Herschensohn 2020). The current study aims to address child heritage speakers’ overregularization of Spanish past participles and to highlight the patterns that constrain this phenomenon. It is expected that, like all children, child heritage speakers will vary between irregular and overregularized forms. At the same time, child heritage speakers may produce especially high rates of overregularization and may do so well into school age. Finally, since overregularization tends to occur more often with low-frequency forms than with high-frequency ones (Baker 2022; Bybee 2007; Ullman 2001), it is predicted that the child heritage speakers’ overregularization will be mediated by lexical frequency.

1.1. Children’s Overregularization of Verb Forms

Crosslinguistically, children apply patterns to forms that are irregular in adult speech. For example, children learning English produce tokens like eated for ate and falled for fell (Pinker and Prince 1988). This occurs through analogy using the schema in Example 1, whereby the “add–ed” pattern used for regular English past tense is applied to irregular verbs like ate. This linguistic phenomenon, called overregularization, demonstrates how children acquire language by using general learning mechanisms such as association and generalization (Yang 2016).

| (1) | Talk + ed = past tense ‘Talked’ |

| Eat + ed = past tense ‘Eated’ | |

| Fall + ed = past tense ‘Falled’ |

Overregularizations like 1 are of particular interest in child language acquisition research, as they demonstrate how children acquire morphology. Research shows that children begin to overregularize only once they have productive knowledge of the regular pattern or rule (Yang 2016). This period marked by more overregularization coincides with gains in the child’s vocabulary size and their grammatical knowledge in general (Frank et al. 2021; Mueller Gathercole et al. 1999; Marcus et al. 1992; Shin and Miller 2022; Yang 2016). This is because, as children learn more words, they are exposed to the regular pattern in more items and begin to overapply it to the irregulars. As such, overregularization demonstrates U-shaped development; that is, younger children produce more irregular forms like puse ‘I put’, sé ‘I know’, and hecho ‘done/made’ before learning the regular rule, at which point they go through a period during which they produce overregularized variants like poní, sabo, and hacido (Clahsen et al. 2002; Yang 2016). Ultimately, as children experience more irregular forms, they retreat from overregularization (Baker Martínez, forthcoming).

Lexical frequency effects provide further evidence that language experience plays an important role in the onset of and the retreat from overregularization. More specifically, children overregularize more with low-frequency forms as compared to high-frequency ones (Baker 2022; Bybee and Slobin 1982; Clahsen et al. 2002). Crosslinguistically, irregularity and high frequency correlate and, as such, high-frequency irregular forms become entrenched and are less susceptible to regularization or analogical leveling (Bybee 1985). In Spanish, some of the most common verbs are irregular: ser ‘to be’, estar ‘to be’, ir ‘to go’. These irregular forms are learned early, and frequency of use strengthens their mental representation; in turn, they are overregularized less often (Bybee 2007). Baker (2022) studied Spanish-speaking children’s production of the second person singular (2sg) preterit forms (e.g., fuiste ‘you were/went’ overregularized as fuistes) and found a prominent frequency effect. Results showed that children were more likely to overregularize low- and mid-frequency preterit forms like pintaste ‘you painted’ and diste ‘you gave’ (24% and 11%, respectively) in contrast to high-frequency verbs like hiciste ‘you did/made’ (6%). These studies demonstrate that lexical frequency should be considered when examining children’s overregularization of past participles.

While most of the research on overregularization has focused on monolingual children, bilingual children, including child heritage speakers, provide an exciting opportunity to better understand the impact of language experience on overregularization. For example, Baker (2022) found that Spanish children living in Galicia and Catalonia, areas with official regional languages in addition to Spanish, overregularized 2sg preterit –s as in dijistes ‘you said’ more often than children in non-contact regions like Madrid. Fernández-Dobao and Herschensohn (2020) studied overregularization of stem-changing verbs using a form-focused elicitation task with 77 children, ages 9–10 years old. Of the 77 children, 62 were bilingual, all enrolled in a dual immersion program in the U.S. Of the 62 bilinguals, 21/62 were child heritage speakers of Spanish who grew up with Spanish in the home, and 41/62 were native speakers of English who were second language learners of Spanish. The study also included 15 age-matched children born and raised in Spain. The child second language learners had the highest rate of overregularization of present tense stem-changing morphology (e.g., conto ‘I tell/count’ instead of cuento), followed by the child heritage speakers, and, lastly, the children in Spain, who almost never overregularized (overregularization rates were 66%, 39%, and 2%, respectively). This study supports the conclusion that varying amounts of Spanish language experience predict overregularization; children with less experience overregularize more and for an extended period of time.

1.2. Overregularization of Past Participles in Spanish

In Spanish, a morphologically rich language with some 53 verbal morphemes between regular and irregular verbs (Rojas-Nieto 2003), children have ample opportunities to overregularize. Indeed, research finds that Spanish-speaking children produce more innovative forms with irregular verbs than their regular counterparts (Clahsen et al. 2002; Johnson 1995). However, most of this research has focused on past and present tense irregular morphology, not past participles, which have been shown to be overregularized in other languages, including English (Bybee and Slobin 1982), French (Kresh 2008), and German (Clahsen and Rothweiler 1993). In German, Szagun (2011) examined German-speaking children’s spontaneous speech between the ages of 1;4 and 3;8 and found that overregularization of past participles like gesprungen ‘sprung’ as gespringt using the regular -t suffix were the most dominant substitutions among the children. Spanish past participles like rompido have also been found in studies of naturalistic child language production (Baker Martínez, forthcoming; Clahsen et al. 2002; Johnson 1995), but have not been investigated systematically in an experimental study controlling for factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of overregularization. The current study aims to fill this gap.

There is a strong regular pattern used for most Spanish past participles; these regulars combine the verb stem; the thematic vowel -a- or -i-, which groups verbs into classes; and –do, which is the inflectional morpheme that forms the participle. Examples are shown in (2).

| (2) | Verb stem | Thematic vowel | Past participle |

| Hablar ‘to speak’ | habl - | - a - | do |

| Comer ‘to eat’ | com - | - i - | do |

| Venir ‘to come’ | ven - | - i - | do |

Meanwhile, a small number of irregulars do not follow this pattern. Irregular past participles generally have a stem alternation and can take three possible inflectional morphemes, as illustrated by the examples in Table 1.

Table 1.

Irregular Spanish past participle morphemes and examples.

Children overregularize irregular past participles by applying the -do morpheme to forms that are irregular in adult speech, such as hacido instead of hecho. The examples below, taken from Baker Martínez (forthcoming), show an irregular past participle (3) and an overregularized variant of the same past participle (4) in naturalistic child speech from the CHILDES database (MacWhinney 2000).

| (3) | Todavía no me lo han dicho. |

| ‘They haven’t told me yet.’ (5;5, monolingual; BeCaCeSno) | |

| (4) | Discúlpeme mamá por haber *decido los cubiertos. |

| ‘Forgive me, mom, for having said dishes.’ (cf. dicho; 5;9, monolingual: | |

| BeCaCeSno) |

Baker Martínez (forthcoming) examined corpus data from 47 Peninsular Spanish-speaking children from Madrid, Valladolid, and Pamplona, whose ages ranged from 3;0 to 6;11. Two of the 47 Spanish children were growing up bilingual; they spoke English with their American mother. These children had higher MLUs in English than in Spanish. Averaging across all 47 children in the study, the past participles were overregularized 7% of time, resulting in forms like escribido instead of escrito. The study also found that past participle overregularization was predicted by the children’s language background, age, and lexical frequency. The two bilingual children were more likely across all ages to overregularize compared to the 45 monolingual children (14% and 3%, respectively). The results also showed an effect of age: The 3- and 4-year-olds overregularized more than the 5- and 6-year-olds (13% and 2%, respectively). Further, there was an interaction between age and language background whereby the bilingual children continued to overregularize through age 6;11, whereas the monolingual children’s rates significantly decreased by the age of 5 years. These findings indicate that the English–Spanish bilingual children overregularized more often and for a longer period of time as compared to the monolingual children.

In addition to finding age and language background effects, Baker Martínez (forthcoming) found that lexical frequency mediated the Spanish children’s overregularization of past participles. Baker Martinez’s frequency categories were based on counts from the Davies Corpus del Español NOW (Davies 2018). Low-frequency past participles were those that had 499,999 occurrences or less and included: puesto ‘put’, vuelto ‘returned’, escrito ‘written’, muerto ‘dead’, roto ‘broken’, and abierto ‘opened’. In contrast, the high-frequency items had more than 500,000 occurrences and included hecho ‘done/made’, dicho ‘said’, and visto ‘seen’. As predicted, the low-frequency participles were more likely to be overregularized than the high-frequency ones (27% and 1%, respectively).

The results for language background, age, and lexical frequency in Baker Martínez’s study indicate that overregularization of past participles is mediated by language experience. However, her study only included two bilingual children compared to 45 monolingual children. Thus, the current study aims to further investigate language background by focusing on child heritage speakers, who offer an excellent test case for investigating the impact of language experience on the developing heritage grammar (Flores et al. 2017; Mueller Gathercole and Thomas 2009; Rodina and Westergaard 2017; Shin et al. 2021; Shin et al. 2023; Silva-Corvalán 2014; Thordardottir 2015). The current study includes 20 children born and raised in the USA. It aims to increase our understanding of child heritage speakers’ overregularization of Spanish verbal morphology, in this case past participles, and addresses the following four research questions:

- What factors determine whether children use past participles?

- At what rates and ages do Spanish–English bilingual children born and raised in an English-dominant society produce overregularized past participles?

- How does lexical frequency affect children’s past participle overregularization?

- What is the role of Spanish language experience and proficiency in children’s overregularization of their past participles?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

The study included 20 heritage speakers of Spanish between the ages of 5;1 and 11;9. Children were recruited from a dual language K-8 school in Albuquerque, NM (N = 11) and via snowball sampling (N = 9). All children were born in the U.S.; 16 were born in New Mexico, and the remaining were born in Texas (N = 1), Ohio (N = 1), Massachusetts (N = 1), or Illinois (N = 1). Regarding the children’s caretakers, four children had two parents born in Mexico; eight children had one parent born in Mexico and one in the U.S. Meanwhile, there were four children with parents from other Spanish-speaking countries; one child had one parent from Puerto Rico and another parent from Mexico. Another child’s mother was from Spain, and her father was from Mexico. While this child, age 10;5, was exposed to a variety of Peninsular Spanish, where children have been found to acquire past participles earlier than in Mexico (Baker Martínez (forthcoming); also compare Mueller Gathercole et al. 1999, p. 145 and Grinstead 2000 to Jackson-Maldonado 2012, p. 162), she overregularized 100% of her participles. As such, she was more comparable to the other children in the current study than to children in Spain. Additionally, two siblings’ parents were both born in New Mexico with grandparents from New Mexico and Mexico. Lastly, three Mexican parents provided only the mother’s birthplace in response to the questionnaire and left out the father’s birthplace. In sum, the majority (17/20) of the children had at least one parent born in Mexico.

Parents filled out a language background questionnaire with 10 questions regarding the languages used in the home. There were seven questions that gauged how often each language was used at home and in school and three questions regarding how often the child used each language at home. Each question had five possible responses that corresponded to a number between 0 all English, 1 more English than Spanish, 2 same amount of Spanish and English, 3 more Spanish than English, and 4 all Spanish. Each child’s average language score was calculated. The average score across all 20 children was 2.23/4 (SD = 0.84), indicating that Spanish was used at a slightly higher rate than English in the sampled children’s homes.

The children completed the Spanish Morphosyntax section of the BESA or BESA-ME. In these assessments, the researcher presents the child with images and prompts them to respond with target structures. See Figure 1 for an example stimulus and prompt from the BESA (Peña 2018).

| Prompt: | Los niños tienen unos carros. ¿Y aquí? ¿Qué tienen los niños? Los niños |

| tienen... | |

| ‘The children have some cars. And here? What do the children have? The children | |

| have...’ | |

| Correct response: | el/un carro. |

| ‘a/the car.’ |

Figure 1.

Example of a BESA stimulus testing for articles.

Children aged 6;11 and under completed the BESA, which includes a total of 15 cloze items testing children’s proficiency with articles, such as un/el pan; present progressive verbs, such as está leyendo ‘he/she is reading’; direct object clitics, like los abren ‘they open them’; and subjunctive, like la mamá quiere que se lave los dientes ‘the mom wants her to brush her teeth’. The children also completed a sentence repetition task with 37 target forms. One 5-year-old child’s BESA results were unusable, as the child did not cooperate during the test. In order to not lose this child’s experimental data, the average BESA score for children in her age group was calculated and assigned as her score (see Ellingson Eddington 2022 for a similar solution). Meanwhile, children aged 7;0 and older completed the BESA-ME (Peña et al. 2011 in development), which has a total of 19 cloze items testing for knowledge of irregular past-tense verbs like puso ‘he/she put’; relative clauses, such as el niño que tiene el globo rojo ‘the boy that has the red balloon’; subjunctive, like la maestra quiere que escriban ‘the teacher wants them to write’; imperfect verb forms, like cuando era niño siempre jugaba baloncesto ‘when he was a boy he always played basketball’; and adjective agreement, like este es un globo rojo ‘this is a red balloon’. The BESA-ME also includes a sentence repetition task with 32 forms. Children’s scores were scored according to the test guidelines, and their raw scores were calculated and included as a percentage in the analysis.

Table 2 includes the children divided into three age groups ranging from 5;1 to 11;9 and shows the number of children per age group, as well as their average language background questionnaire and BESA/ME morphosyntax scores according to age group. Even though the oldest children had the lowest average language background questionnaire score, age and questionnaire score were not significantly correlated [r(18) = − 0.20, p = 0.39]. Similarly, although morphosyntax scores appeared to increase across age groups, there was no significant correlation between morphosyntax score and age [r(18) = 0.33, p = 0.16]. Finally, there was no significant correlation between language background questionnaire and morphosyntax score [r(18) = 0.41, p = 0.07].

Table 2.

N children by age group, language background questionnaire, and morphosyntax score.

2.2. Materials and Procedure: Elicited Production Task

Children completed an elicited production task that contained 24 test items. The experimental task was designed to elicit a past participle in a compound tense with auxiliary verb haber ‘to have/to be’. Children were presented with two pictures side-by-side of a stick-figure character named Pablo (see Figure 2) and were told a short story about the character that ended with the auxiliary verb form hubiera ‘should have’.1 Children were expected to finish the sentence with a participle. For example, in Figure 2, the experimenter pointed to the stick figure writing the number and said En esta historia, Pablo está escribiendo un número ‘In this story, Pablo is writing a number’. Then, she pointed to the stick figure writing the letter A and said pero él hubiera ____ ‘but he should have _____’. The expectation was that children would respond with utterances like escrito un número ‘written a number’. The task included six irregular past participles (Table 3), each elicited in four trials. Following previous research on child heritage speakers in the U.S., no distractor items were included in order to keep the task as short as possible while including sufficient items that enabled analysis of predictor variables (Cuza et al. 2019).

Figure 2.

Past participle production task stimulus example.

Table 3.

Six past participles used in test items.

Before starting the production task, children were trained to complete the researcher’s sentence. In this training, the researcher acted out the voice of a puppet to model sentence completion. For example, in the following example, the researcher first presented the prompt, then took on the role of the puppet to complete the sentence with a gerund form, as in (5).

| (5) | Researcher: | Ayer, Pablo montó un caballo amarillo. Pero ahora él está…. |

| ‘Yesterday, Pablo rode a yellow horse, but now he is...’ | ||

| Puppet: | montando un caballo negro. | |

| ‘riding a black horse’ |

Following the training, to verify the child knew to finish each sentence prompt, there were four practice items, as in (6). These practice items prompted the use of four regular participles (montado ‘ridden’, comido ‘eaten’, llevado ‘worn’, ido ‘gone’) and followed the same overall structure as the test items (see examples (7) and (8)).

| (6) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo está montando una bicicleta amarilla. Pero |

| él hubiera.... | ||

| ‘In this story, Pablo is riding a yellow bike, but he should have...’ | ||

| Child: | montado una bicicleta azul. (11;4, m) | |

| ‘ridden a blue bike’ |

3. Coding

Participants’ responses were audio-recorded and transcribed and coded in Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2023) using an Editor Script.2 All participants’ responses that contained a past participle were included in the study. Five tokens were excluded because the verb/response was inaudible. The dependent variable of interest was the past participle form produced, whether it was a standard irregular past participle (7) or a non-standard overregularized past participle (8).

| (7) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo se está poniendo un suéter azul, pero él se |

| hubiera... | ||

| ‘In this story, Pablo is putting on a blue sweater, but he should | ||

| have...’ | ||

| Child: | puesto un suéter morado (11:2, f). | |

| ‘put on a purple sweater’ | ||

| (8) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo se está poniendo zapatos negros, pero él se |

| hubiera. | ||

| ‘In this story, Pablo is putting on a blue sweater, but he should | ||

| have...’ | ||

| Child: | ponido (cf. puesto) zapatos verdes (9;2, f). | |

| ‘put on green shoes’ |

The study aimed to investigate the effect of the following independent variables on children’s past participle production:

- i.

- Participant age: 61–141 months (range: 5;1–11;9 years; median: 8;9).

- ii.

- Language background questionnaire (score from 0 to 4; the higher the score, the more Spanish spoken in the child’s environment)

- iii.

- BESA/ME morphosyntax score (0–100%)

- iv.

- Lexical frequency of past participle (low, high).

The task included six irregular past participles, which were counterbalanced for lexical frequency between high- and low-frequency participles. Following Baker Martínez (forthcoming), lexical frequency counts were calculated by searching in the Davies’ (2018) Corpus de Español NOW for all compound tenses comprising haber + participle (for example: present perfect: he hecho, has hecho, ha hecho, etc.; pluperfect: había hecho, habías hecho; imperfect subjunctive: hubiera hecho, huberias hecho, etc.; future perfect: habré hecho, etc.; indicative perfect: haber hecho). Instances of participles used as adjectives or nouns were not included. Next, for each of the six participles, the frequency count in each compound tense was added together for the final lexical frequency count (Table 4). The frequency counts were cross-checked with two other Spanish-language online corpora (Real Academia Española 2023; Pallier et al. 2019), and the participles were ranked in the same order across corpora.

Table 4.

Past participle lexical frequency in compound tenses used in child speech.

The following examples illustrate children’s production of a low-frequency participle (9) and a high-frequency participle (10).

| (9) | Researcher: | En esta historia, se está muriendo la araña de pablo, pero se |

| hubiera... | ||

| ‘In this story, Pablo’s spider is dying, but it should have...’ | ||

| Child: | morido su serpiete (11;2, f) | |

| ‘died his snake.’ | ||

| (10) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo está haciendo arte, pero él hubiera... |

| ‘In this story, Pablo is making art, but he should have...’ | ||

| Child: | hacido ejercicio (8;1, f) | |

| ‘worked out.’ |

4. Results

The children produced a total of 467 responses to test items in the elicited production task; of these, 250 included past participles. Thus, as has been observed in other experimental studies (Shin et al. 2023), the children did not always respond with the expected response (i.e., a past participle) in the target contexts and instead produced other forms, such as infinitives (11), noun phrases (12), or other verb forms such as the preterit past tense (13). Most of the past participles (233/250) were irregular verbs, such as roto ‘broken’, which were either produced as irregular, as in (7), or were overregularized, as in (8). The remaining 14 past participles were cases where children produced an adult-like regular past participle instead of the participle form of the verb in the prompt, as in quebrado instead of roto ‘broken’ (14).

| (11) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo está rompiendo la tele, Pero él hubiera… |

| ‘In this story, Pablo is breaking the TV, but he should have...’ | ||

| Child: | romper el puerta (10;1, f). | |

| ‘to break the door.’ | ||

| (12) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo está haciendo un pastel. Pero él hubiera… |

| ‘In this story, Pablo is making a cake, but he should have...’ | ||

| Child: | cookies (5;9, m). | |

| ‘cookies.’ | ||

| (13) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo está haciendo una sopa. Pero él hubiera… |

| ‘In this story, Pablo is making soup, but he should have...’ | ||

| Child: | hizo una pizza (8;2, f). | |

| ‘made (preterit past tense) a pizza.’ | ||

| (14) | Researcher: | En esta historia, Pablo está rompiendo la tele, Pero él hubiera… |

| ‘In this story, Pablo is breaking the TV, but he should have...’ | ||

| Child: | quebrado la puerta (7;3, f). | |

| ‘broken the door.’ |

4.1. Past Participles Versus Other Strategies

It is worth noting that seven of the 20 sampled children did not produce any past participles at all. On average, these children were younger than those who produced participles, had lower language background questionnaire scores (more English spoken in the home), and lower BESA/ME morphosyntax scores (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison between groups of children according to forms produced.

In order to examine further what predicted whether children would produce a past participle in the prompted context versus alternative responses like those in Examples (11)–(13) and address the first research question, a mixed-effects binary logistic regression was run in R (R Core Team 2019) using the glmer function in the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015). The three continuous variables included in the regression analysis in Table 6 were: children’s age, language background questionnaire scores, and BESA/ME morphosyntax scores. The dependent variable for the current analysis was past participle vs. other response, with the model set to predict past participle production. As such, positive coefficient estimates indicated that a factor increased the likelihood a child would respond with a past participle in the elicited contexts.

Table 6.

Mixed-effects logistic regression predicting the likelihood of past participle vs. other structure production, AIC = 249.9, 20 children.

The results from Table 6 demonstrate main effects for all of the predictor variables. That is, older children were more likely to produce a past participle in response to the stimuli; the more exposure and use of Spanish, the more the children produced a past participle, demonstrated by the main effect of their language background questionnaire score. Similarly, children’s grammatical knowledge and proficiency played a role in whether they used a past participle: the higher their BESA/ME morphosyntax scores, the more likely they were to produce a past participle. These results demonstrate that children with less exposure and proficiency in Spanish relied on other strategies to complete the task, while children with more exposure and proficiency in Spanish were likelier to respond with the past participles in their responses.

4.2. Overregularization of Past Participles

Turning to the main focus of the current study—overregularization of past participles—the next analysis zeroed in on the past participles produced with the six irregular verbs chosen for the study (Table 4), and thus excluded the 14 tokens of other participle forms like quebrado. Recall that there were 233 tokens of the six irregular verbs that were targeted; 173 (74%) were overregularized. The standard variants, like escrito and dicho, occurred 26% of the time (n = 60). Overregularized variants included forms like escribido, hacido, and rompido, as well as even more innovative forms that illustrated the overregularization of the participle ending as well as a stem change like dicido, muriedo, and pusido. The forms with the regular participle morpheme -do, like hacido, comprised the majority of regularized tokens (n = 135), while there were 38 tokens of the more innovative forms containing both a stem change and the regular morpheme, like pusido. For the analyses of overregularization, these 38 tokens with -do overregularization and stem changes were grouped with the other 135 tokens of -do overregularization. We discuss the 38 forms with stem changes in Section 5.

Table 7 lists the six irregular past participles used in the experimental design according to their frequency category, each participle’s token count, and their overregularization rates. Puesto and roto, the participles with the highest token count, were overregularized at rates of 70% and 84%, respectively. Meanwhile, hecho was produced less often and was overregularized at a rate of 63%.

Table 7.

Rates of overregularization of irregular past participles.

To test the effect of the predictor variables on children’s participle overregularizations, a mixed-effects binary logistic regression was run in R (R Core Team 2019) using the glmer function in the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015). The data set only includes responses from the children who produced irregular past participles in response to the stimuli (N = 13). The dependent variable was overregularized vs. irregular past participle forms. The best fit model was selected using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) score and included two continuous variables: age, BESA/ME morphosyntax score as a percent, and one categorical variable: lexical frequency (high, low).3 The language background questionnaire was dropped from the final model, as it was not significant. Additionally, all possible interactions were entered into the model, and the best fit model included two: lexical frequency*BESA/ME morphosyntax score and lexical frequency*age (AIC = 139.9). There were no issues of collinearity in the model; variance inflation factors (VIFs) ranged from 1.02 to 1.04. Table 8 presents the results from the final model. As the model was set to predict overregularization, positive coefficients indicated that a factor increased the likelihood of overregularization, and negative coefficients indicated that a factor decreased the likelihood of overregularization.

Table 8.

Logistic regression predicting the likelihood of overregularized vs. irregular past participles, AIC = 139.9, 13 children.

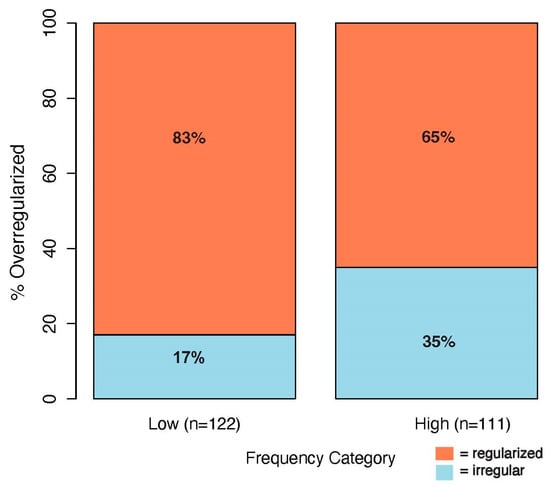

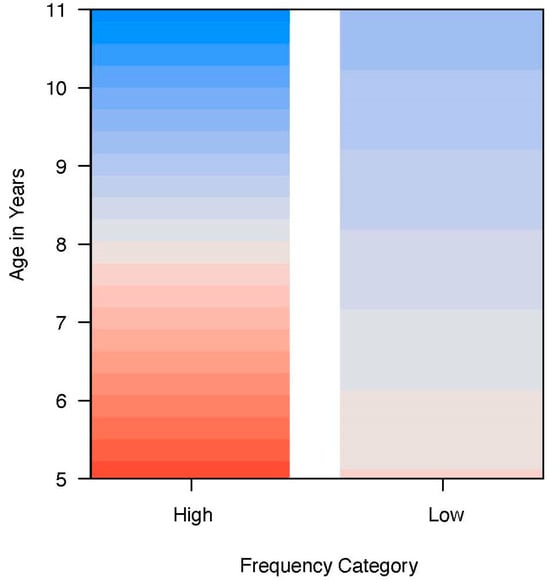

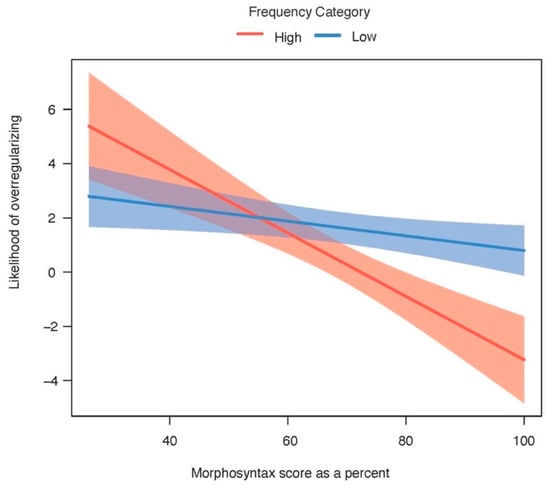

The regression analysis results in Table 8 demonstrate a main effect of age: younger children were likelier to overregularize than older ones. Additionally, the sampled children’s past participle overregularizations were predicted by lexical frequency: low-frequency participles (e.g., rompido) were likelier to be overregularized as compared to high-frequency ones (e.g., decido) (Figure 3). Additionally, there was an interaction between children’s age and lexical frequency, whereby younger children were more likely to overregularize high-frequency participles (Figure 4); however, there was no effect of age on the low-frequency participles. Children’s grammatical development was also a significant predictor of whether they overregularized; specifically, the higher the Spanish morphosyntax scores, the less likely they were to overregularize the past participle. Finally, the interaction between lexical frequency and morphosyntax score indicated that the higher the child’s morphosyntax score, the less likely they were to overregularize high-frequency past participles like dicho (Figure 5). These findings are presented in more detail below.

Figure 3.

Distribution of overregularized forms according to frequency, χ2 (1, n = 233) = 7.1, p = 0.007.

Figure 4.

Interaction between age and lexical frequency on children’s overregularization.

Figure 5.

Interaction between lexical frequency and morphosyntax score on children’s overregularization.

4.2.1. Age Results

The ages of the 13 children who produced irregular past participles ranged from 5;1 to 11;4, with an average age of 9;1. Results from the regression analysis (Table 8) indicate that the older the child, the less likely they were to overregularize. Table 9 presents the number of children and distribution of irregular versus overregularized tokens across age groups and shows that by 10–11 years of age, the average rate of overregularized past participles decreased to 53%, while the averages for other age groups were 90% and 100%.

Table 9.

Distribution of children across ages and overregularization rates.

4.2.2. Frequency Results

The results from the regression analysis (Table 8) demonstrate that lexical frequency significantly predicted children’s overregularization of irregular past participles. Specifically, children were more likely to overregularize low-frequency past participles like roto and escrito than high-frequency ones like hecho or dicho. Figure 3 presents the frequency results and illustrates that the sampled children overregularized low-frequency forms like muerto (83%) at significantly higher rates than high-frequency forms like dicho (65%).

4.2.3. Age and Lexical Frequency Interaction

In addition to a main effect for both age and frequency, there was an interaction between these two variables. This effect is visualized in Figure 4. The red in the Figure represents the likelihood of producing overregularized -do. Specifically, with high-frequency past participles, younger children between the ages of 5 and 8 years were more likely to overregularize these forms (e.g., hacido), whereas older children were more likely to produce the standard irregular form (e.g., hecho). In contrast, there was no effect of age on the likelihood of overregularizing the low-frequency participles like roto.

4.2.4. Lexical Frequency and Morphosyntax Score Interaction

The results in Table 8 demonstrate that the higher the morphosyntax score, the less likely the child was to overregularize. In addition to the significant main effects for lexical frequency and morphosyntax score, the results from Table 8 show a significant interaction between these two variables. This interaction is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5 demonstrates that the children, regardless of their morphosyntax score, overregularized low-frequency participles. By contrast, the higher the children’s morphosyntax score, the less likely they were to overregularize high-frequency past participles hecho, dicho, and puesto. This interaction suggests that, as children’s Spanish grammatical knowledge increases, they produce more high-frequency irregular past participle forms as irregulars, that is, they refrain from overregularizing these forms. The low-frequency past participles do not show this same effect; these forms continue to be overregularized even as the child’s morphosyntax score increases.

5. Discussion

The current study investigated child heritage speaker’s overregularization of Spanish past participles, as in escribido (cf. escrito), by means of an elicited production task. Four research questions guided the study, the first focusing on what factors predicted whether the children would respond with a participle in the production task. Meanwhile, the second question examined the overall rates of overregularization and the ages at which overregularization occurs. The third question focused on the impact of lexical frequency on overregularization, which has ramifications for our understanding of the role of language experience underlying overregularization and children’s retreat from it. Finally, the last question focused on whether overregularization is predicted by Spanish language experience and proficiency, factors that have been shown to predict other areas of the developing child heritage grammar (e.g., Shin et al. 2023). In this section, we discuss each research question in turn. Regarding the first research question, it must be noted that seven out of 20 children produced no past participles at all (Table 5). Compared to the children who did produce participles, the ones who did not were significantly younger and had significantly lower language background questionnaire scores, indicating less Spanish language experience in the home and at school, as well as lower Spanish morphosyntax scores. It is possible that these children had not yet acquired past participles, although it would be necessary to test the children’s receptive knowledge of these forms to establish that this is the case (e.g., Giancaspro and Sánchez 2021). The lack of a comprehension task to test for the children’s knowledge of past participles in the structure studied is a limitation of the current study. Next, we turn our discussion to overregularization among the 13 child heritage speakers whose responses included past participles.

5.1. Overall Rates and Age of Overregularization

Our second research question addressed the overall rates and ages at which Spanish-English bilingual children born and raised in an English-dominant society produce overregularized past participles. The sampled children overregularized past participles at unusually high rates; 74% of their past participles were an overregularized variant (e.g., hacido). Not only did children produce expected overregularized variants like hacido using the infinitival stem and the regular -do morpheme, but there were also innovative variants like hicido, pusido, and muriedo. Table 10 presents the overall frequency of occurrence of the past participle variants produced by the children.

Table 10.

Distribution of past participle forms in production task.

Table 10 demonstrates that the most frequently produced variants were overregularized variants like hacido. In these tokens, children used the infinitival base of the verb and applied the regular -do inflection for past participles. However, children also produced more innovative forms like hicido, in which cases they applied the regular -do inflection and a stem change. The use of these types of variants across children suggests that these children were aware that the participle forms had irregularities; however, they were not able to produce the adult-like irregular form and instead produced an innovative variant with an irregular stem and a regularized inflection. With hicido and pusido, it appears they applied the regular participle form -do to the base used to form preterit verbs (hice, hiciste, etc. ‘I did/made, you did/made’; puse, pusiste, etc. ‘I put, you put’). Further, these results also demonstrate that children do not just overregularize past participles in one way, but rather, these forms can vary according to speakers as well as lexical items.

The high rates of regularized forms contrast with previous research on overregularization of Spanish verbal morphology. For example, for irregular present and past tense morphology, Clahsen et al. (2002) found rates of 14% and 1.5%, respectively. Meanwhile, Baker Martínez (forthcoming) examined Spanish children’s overregularization of Spanish past participles in corpus data and found 7% overregularization. Why were the overregularization rates so high in the current study, especially in comparison to the rates in Baker Martínez’s corpus study of Spanish children’s past participles discussed above? One possibility is related to differences in the populations studied; Baker Martínez included 47 Spanish children living in Spain, whereas the current study included U.S. born bilingual English–Spanish speaking children. Children in Spain are exposed to abundant instances of past participles due to the frequency of the present perfect tense, including hodiernal perfective uses (Schwenter and Torres-Cacoullos 2008). Previous research has found that children in Spain produce present perfect verbs earlier than do children learning varieties of Spanish in which the past participles are less frequent. For example, the first tense/aspect contrast among Mexican monolingual children is the present simple/preterit (Jackson-Maldonado 2012, p. 162), whereas it is the present simple/present perfect among monolingual children in Spain (Mueller Gathercole et al. 1999, p. 145; Grinstead 2000, p. 128). Given the frequency of past participles in Spanish in much of Spain, which affords children extensive practice with these forms, Spanish children may overregularize these forms less often and may retreat from overregularization earlier. In fact, in Baker Martínez’s study, the 45 monolingual children in Spain retreated from overregularization by 5 years of age.

Another difference between the population in Baker Martínez’s study and that in the current study is that the former included only two bilinguals who overregularized at overall rates of 12% and 16% and were living in Spain, where the dominant language is Spanish. In contrast, in the current study, the bilingual children were living in the U.S. in an environment where the dominant language is English. Clearly, these are vastly different bilingual language development scenarios. Such differences across communities are also evident in studies of 2sg preterit forms: Baker (2022) found lower overregularization rates among children in Spain (18%) as compared to Lerner (2016), whose study focused on bilingual Spanish–English children in Philadelphia; these children overregularized the 2sg preterit forms 66% of the time. As such, the current study’s high overregularization rates are comparable to Lerner’s (2016) 2sg overregularization rates among bilingual children, which demonstrates that rates of overregularization among bilingual children in the U.S. are extended in comparison to monolingual children living in Spanish-speaking countries. These findings bolster the conclusion that language experience and bilingualism play a role in overregularization, a point to which we will return in our discussion of research question 4 below.

Another possible explanation for the differences in rates across studies has to do with methodology. Baker Martínez (forthcoming) studied overregularization of past participles in naturalistic production data, whereas the current study employed an elicited production task. Other studies also suggest differences between experimental and corpus data. For example, children overregularize English past tense -ed at higher rates in experimental studies than in natural language production (Ambridge and Rowland 2013). The same is true for Spanish gender agreement; children produce mismatches in gender more often in experimental studies than in natural language production (e.g., Goebel-Mahrle and Shin 2020). There are various possible explanations for higher rates of overregularization or mismatching during experiments. Experiments may be more taxing and thus could slow down retrieval of an irregular form. Also, the words children rely on during natural conversations may be especially frequent words, which in general are less susceptible to overregularization. Furthermore, the use of the complex form of the auxiliary verb haber used in the elicited production task (i.e., hubiera) could have also amplified overregularization rates, as the complexity of a morphological form can affect its likelihood of overregularization (Bybee 1985; Mueller Gathercole et al. 1999). In sum, the vastly different rates of overregularization across linguistic structures and across studies may be due to population differences, the methodology used, as well as the structures and lexical items targeted in each study.

Regarding the age at which children overregularize past participles, children in the current sample produced overregularized variants from the ages of 5;1 up to 11;4. Results from a mixed-effects regression analysis (Table 8) found a main effect of age; the older the children were, the less likely they were to produce an overregularized form like escribido. This age effect is most likely tied to increased experience with the Spanish language. Frank et al. (2021) found that the onset of overregularization in English, Norwegian, Danish, and Slovak correlates more tightly with vocabulary size than with age. Kirjavainen et al. (2012) found that Finnish children’s vocabulary size was a strong predictor of Finnish past-tense verbs. The current study suggests a similar conclusion for the retreat from overregularization and the production of adult-like irregular participles. As demonstrated in Table 8, the effect size for the morphosyntax score was larger than the one for age, indicating that increased knowledge of Spanish grammar was a stronger predictor of adult-like irregular participle production as compared to age. In sum, while the current study found an age effect indicating that the older children overregularized less than younger children, it seems that retreat from overregularization is more closely tied to language experience and proficiency than to age.4 We discuss the impact of these factors in more detail in the following sections.

5.2. Lexical Frequency

The third research question dealt with the impact of lexical frequency on children’s past participle overregularization. The study included low-frequency past participles escrito, roto, muerto and high-frequency past participles puesto, dicho, hecho (Table 4). The children were more likely to overregularize the low-frequency past participles like roto in contrast to the high-frequency ones like hecho (Table 8). More specifically, children overregularized low-frequency past participles at a rate of 83%, while they overregularized 65% of their high-frequency past participles (Figure 2). Thus, while both low- and high-frequency past participles were overregularized often in the experimental data, the low-frequency forms were significantly more likely to undergo overregularization and be produced as variants like rompido. These results suggest that the more often children are exposed to irregular past participles, the less likely these forms will be overregularized (Bybee 2007).5

The frequency results align with previous research on overregularization in corpus studies, which finds that lexical frequency plays an important role in children’s overregularization of irregular verbal morphology in Spanish, German, English, and French (Baker 2022; Clahsen et al. 2002; Clahsen and Rothweiler 1993; Szagun 2011). Baker’s (2022) corpus study on Spanish children’s overregularization of the 2sg preterit forms (e.g., pintastes) found that children were more likely to overregularize low- and mid-frequency verbs (e.g., pintaste 24%, pusiste 11%) than high-frequency 2sg forms (e.g., fuiste 6%). Regarding past participles, Baker Martínez (forthcoming) found that Spanish children overregularized low-frequency past participles like abierto 27% of the time, while their high-frequency participles like hecho were only overregularized 1% of the time.

While lexical frequency was a significant predictor of children’s overregularization, with low-frequency past participles increasing the likelihood of an overregularized form (e.g., escribido), it is worth noting that even the high-frequency past participles did undergo quite a bit of overregularization in the current study (65%); however, the interaction between lexical frequency and morphosyntax scores (Figure 5) indicates that overregularization of frequent forms was found among children with lower morphosyntax scores. The higher the children’s grammatical proficiency, the less likely they were to overregularize the high-frequency past participles like dicho. Furthermore, an additional interaction between lexical frequency and age showed that the children between the ages of 5 and 8 years were more likely to overregularize the high-frequency participles like dicho, while these forms were less likely to be overregularized in the older children. Meanwhile, there was no age effect found for the low-frequency participles like escrito. These findings further bolster the conclusion that children’s retreat from overregularization is tied to overall grammatical development and experience with the language.

5.3. Spanish Language Experience and Proficiency

Our final research question examined the relationship between Spanish language experience and grammatical proficiency on the one hand and overregularization of past participles on the other. Spanish language experience, as measured by language background questionnaire scores, did not predict overregularization of past participle forms (and, as such, this factor was excluded from the regression model in Table 8). In contrast, there was a main effect of the children’s BESA/ME morphosyntax scores on the likelihood of overregularizing (Table 8). The results indicate that, as children’s Spanish morphosyntax scores increased, the less likely they were to overregularize. These findings suggest that children’s acquisition of irregular past participles is directly tied to their grammatical proficiency. As children acquire more complex grammatical structures and more morphological forms, their past participle overregularization decreases.

6. Conclusions

The current study investigated Spanish past participle overregularization among 20 child heritage speakers. Children were presented with prompts that ended with the auxiliary verb haber (e.g., hubiera _______) and were trained to respond in order to complete the sentence prompts (e.g., escrito ‘written’). Seven of the 20 children did not produce any past participles, and instead relied on other strategies such as the use of an infinitive or noun phrase. These children had significantly lower language background questionnaire scores and morphosyntax scores as compared to the 13 children who produced past participles in response to the prompts. Thus, past participle production was dependent on the children’s exposure to and proficiency in Spanish (Table 7).

Among the 13 children who produced past participles, overregularized variants like escribido were the most frequently produced (74%), and they occurred across the ages 5;1 to 11;4. These results demonstrate that, for child heritage speakers, irregular past participles are susceptible to overregularization. At the same time, the study showed that overregularization was mediated by various factors. Specifically, the children’s age and the lexical frequency of the participle were both predictors of past participle overregularization; as children got older, they overregularized less. Similarly, the children in the current study were likelier to overregularize low-frequency past participles like roto (83%) in contrast to high-frequency ones like dicho (65%). The past participle the children overregularized the most often was low-frequency escrito (88%), while high-frequency hecho and dicho both underwent the least overregularization (63%). Additionally, their morphosyntax scores were also a predictor of past participle overregularization; the higher the children’s morphosyntax scores, the less likely they were to overregularize forms like decido. These results indicate that child heritage speakers’ acquisition of irregular verb forms like Spanish past participles is mediated by their language experience: with more exposure to the language, they retreat from past participle overregularization and instead produce irregular forms like roto.

The current study adds to our understanding of how child heritage speakers acquire Spanish grammar and highlights topics of interest to consider in future research. For example, when considered in tandem with previous research, findings demonstrate that overregularization is often mediated by lexical frequency, but it can manifest differently across different speaker groups (e.g., bilinguals vs. monolinguals) and across different language experience profiles depending on the structure of interest. The child heritage speakers in the current study were born and raised in the U.S., where English is the dominant language, and their overregularization rates were extended in comparison to results from a corpus study examining naturalistic speech from children living in a Spanish-speaking country (Baker Martínez, forthcoming). While results show different rates and periods of overregularization across the two studies, both confirm that Spanish-speaking children rely on linguistic patterns like the regular past participle morpheme -do to produce irregular forms they are unfamiliar with. Furthermore, results from both studies suggest that overregularization of past participles is a product of a child’s experience with the language; the more exposure the child has to the language in their daily lives and the more advanced their grammatical knowledge, the less likely they will produce forms like escribido. Future research on Spanish overregularization should include more varied speaker groups (e.g., heritage speakers, second-language speakers, etc.) across broader ages to further investigate the interaction between language experience and overregularization of grammatical patterns. Furthermore, it would be of interest to compare the children’s speech to that of adults as well as a group of age-matched monolingual children to better understand how these forms are regularized across speaker groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.M.; methodology, E.B.M.; software, E.B.M.; validation, E.B.M. and N.S.; formal analysis, E.B.M. and N.S.; investigation, E.B.M.; resources, E.B.M. and N.S.; data curation, E.B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.M.; writing—review and editing, E.B.M. and N.S.; visualization, E.B.M.; supervision, E.B.M. and N.S.; project administration, E.B.M.; funding acquisition, E.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author received a Student Research Grant from UNM’s Graduate and Professional Student Association as well as funding from UNM’s Latinx Linguist Fund. Participants were compensated using these funds. In addition, the first author is grateful to have received PhD fellowships from the Bilinski Foundation and UNM’s Latin American and Iberian Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of New Mexico (protocol number 2250030404 and 05/04/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all child subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No data in this study are publicly available at the time of publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and their families who participated in the study as well as the schools where data collection was carried out. Additionally, they thank Elizabeth Peña and the lab managers at UC Irvine’s HABLA Lab for providing access to BESA and BESA-ME Morphosyntax materials. Further, the authors thank Sarah Lease for providing the Praat Editor Script. Finally, the authors thank the two external reviewers for their feedback and helpful suggestions. Any remaining errors are ours alone.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The auxiliary form hubiera was used in the experimental design due to a trend found in CHILDES data spanning Spain and Latin America whereby children overregularized the past participles more often in the imperfect subjunctive (e.g., hubiera dicho ‘should have said’) and the compound infinitive (e.g., haber dicho ‘having said’) than in the present perfect (e.g., he dicho ‘I have said’). |

| 2 | The authors thank Sarah Lease for providing the Praat Editor Script. |

| 3 | We also ran a separate mixed-effects model including lexical frequency as a continuous variable, but the model failed to converge. |

| 4 | One anonymous reviewer rightly noted that overregularization generally follows a U-shaped trajectory. If child heritage speakers also follow this trajectory, they should produce hecho before hacido and then hecho again. Unfortunately, our study does not capture this trajectory, as 7/20 of the children did not produce any participles. After removing those seven children, only one 5-year-old remained; the other children were 7 years of age or older. It is possible that these children, whose overregularization rates were very high, went through a previous stage in which they produced the irregular verb forms (e.g., hecho). |

| 5 | One anonymous reviewer asked what these frequency results tell us about how language is represented in the mind. There has been a longstanding debate about how regular and irregular forms are stored (see Ambridge and Lieven 2011, pp. 169−87 for an overview). According to the single-route model, both types of forms are stored in an associative memory system (e.g., Bybee and Moder 1983; Bybee and Slobin 1982). By contrast, according to the dual-route model, irregular forms are stored as words in the lexicon, whereas regular forms are the outcome of a computational rule (e.g., Marcus et al. 1992; Pinker and Prince 1988; Ullman 2001). While frequency effects have sometimes been invoked as evidence in favor of the single-route model (e.g., Maslen et al. 2004; Matthews and Theakston 2006), Ambridge and Lieven (2011, p. 180) note that current dual-route models also account for frequency effects. As such, the findings in the current study cannot contribute to the debate. At the same time, it is worth mentioning that Ambridge and Lieven (2011, p. 186) argue that frequency effects in combination with other findings, such as the impact of vocabulary size on regular and irregular forms and the lack of impact of children’s performance on declarative and episodic memory tests, indicate that both regular and irregular forms are stored in memory, which fits well with a single-route model. |

References

- Ambridge, Ben, and Caroline L. Rowland. 2013. Experimental methods in studying child language acquisition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 4: 149–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambridge, Ben, and Elena V. M. Lieven. 2011. Child Language Acquisition: Contrasting Theoretical Approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Martínez, Elisabeth. forthcoming. Y luego un tiburón blanco ha abrido la boca: Spanish children’s overregularization of irregular past participles. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics.

- Baker, Elisabeth. 2022. ¡Casi te caistes!: Variation in second person singular preterit forms in Spanish Children. Journal of Child Language 49: 1256–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2023. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program]. Version 6.0.37. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Bybee, Joan L. 1985. Morphology: A Study of the Relation between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2007. Frequency of Use and the Organization of Language. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan L., and Carol Lynn Moder. 1983. Morphological classes as natural categories. Language 59: 251–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L., and Dan I. Slobin. 1982. Rules and schemas in the development and use of the English past tense. Language 58: 265–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, Harald, and Monika Rothweiler. 1993. Inflectional rules in children’s grammars: Evidence from German participles. In Yearbook of Morphology. Edited by Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, Harald, Fraibet Aveledo, and Iggy Roca. 2002. The development of regular and irregular verb inflection in Spanish child language. Journal of Child Language 29: 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro. 2016. The status of interrogative subject-verb inversion in Spanish-English bilingual children. Lingua 180: 124–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Rocío Pérez-Tattam. 2016. Grammatical gender selection and phrasal word order in child heritage Spanish: A feature re-assembly approach. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Lauren Miller, Rocio Perez Tattam, and Mariluz Ortiz Vergara. 2019. Structure Complexity Effects in Child Heritage Spanish: The Case of the Spanish Personal A. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 1333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2001. Learning a morphological system without a default: The Polish genitive. Journal of Child Language 28: 545–74. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Mark. 2018. Corpus del Español NOW: 6.2 Billion Words, 21 Countries. Available online: https://www.corpusdelespanol.org/now (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Dracos, Melissa, and Pablo E. Requena. 2023. Child heritage speakers’ acquisition of the Spanish subjunctive in volitional and adverbial clauses. Language Acquisition 30: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson Eddington, David. 2022. Processing Spanish Gender in a Usage-based Model with Special Reference to Dual-gendered Nouns. Mental Lexicon 17: 34–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Dobao, Ana, and Julia Herschensohn. 2020. Acquisition of Spanish verbal morphology by child bilinguals: Overregularization by heritage speakers and second language learners. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 24: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Cristina, Ana Lúcia Santos, Alice Jesus, and Rui Marques. 2017. Age and input effects in the acquisition of mood in Heritage Portuguese. Journal of Child Language 44: 795–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Michael C., Mika Braginsky, Daniel Yurovsky, and Virginia A. Marchman. 2021. Variability and Consistency in Early Language Learning: The Wordbank Project. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giancaspro, David, and Liliana Sánchez. 2021. Me, mi, my: Innovation and variability in heritage speakers’ knowledge of inalienable possession. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 6: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel-Mahrle, Tom, and Naomi Shin. 2020. A corpus study of child heritage speakers’ Spanish gender agreement. International Journal of Bilingualism 24: 1088–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John. 2000. Case, inflection, and subject licensing in child Catalan and Spanish. Journal of Child Language 27: 119–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Maldonado, Donna. 2012. Verb morphology and vocabulary in monolinguals, emerging bilinguals, and monolingual children with primary language impairment. In Bilingual Language Development and Disorders in Spanish-English Speakers, 2nd ed. Edited by Brian Goldstein. Baltimore: Brookes, pp. 153–73. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Catalina M. 1995. Verb errors in the early acquisition of Mexican and Castilian Spanish. In The Proceedings of the 27th Annual Child Language Research Forum. Edited by Eve V. Clark. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language & Information, pp. 175–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kirjavainen, Minna, Alexandre Nikolaev, and Evan Kidd. 2012. The effect of frequency and phonological neighbourhood density on the acquisition of past tense verbs by Finnish children. Cognitive Linguistics 23: 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresh, Sarah. 2008. L’acquisition et le traitement de la morphologie du participe passé en français. Master’s thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Marielle. 2016. The Acquisition Of Sociolinguistic Variation In A Mexican Immigrant Community. Publicly Accessible Penn dissertations, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analysing Talk. Mawah: Erlbaum, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Gary F., Steven Pinker, Michael T. Ullman, Michelle HollanderMichelle, John T. Rosen, Fei Xu, and Harald Clahsen. 1992. Overregularization in language acquisition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 57: 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslen, Robert J. C., Anna L. Theakston, Elena V. M. Lieven, and Michael Tomasello. 2004. A Dense Corpus Study of Past Tense and Plural Overregularization in English. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 47: 1319–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Danielle E., and Anna L. Theakston. 2006. Errors of Omission in English-Speaking Children’s Production of Plurals and the Past Tense: The Effects of Frequency, Phonology, and Competition. Cognitive Science 30: 1027–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Kim Potowski. 2007. Command of gender agreement in school-age Spanish-English bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism 11: 301–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller Gathercole, Virginia C., and Enlli Môn Thomas. 2009. Bilingual first-language development: Dominant language takeover, threatened minority language take-up. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 12: 213–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller Gathercole, Virginia C., Eugenia Sebastian, and Pilar Soto. 1999. The early acquisition of Spanish verbal morphology; across-the-board or piecemeal knowledge. The International Journal of Bilingualism 3: 133–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallier, Christopher, Boris New, and Jessica Bourgin. 2019. Openlexicon, Github Repository. Available online: https://github.Com/chrplr/openlexicon (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Peña, Elizabeth D. 2018. Bilingual English-Spanish Assessment (BESA). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, Elizabeth. D., Lisa. M. Bedore, Vera. F. Gutierrez-Clellen, Aquiles Iglesias, and Brian Goldstein. 2011. In Development. Bilingual English-Spanish Assessment-Middle Elementary (BESA-ME). [Google Scholar]

- Pinker, Steven, and Alan Prince. 1988. On Language and connectionism: Analysis of a parallel distributed processing model of language acquisition. Cognition 28: 73–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española: Banco de Datos (Corpes xxi) [En Línea]. Corpus del Español del Siglo XXI (CORPES). 2023. Available online: http://www.rae.es (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Rodina, Yulia, and Marit Westergaard. 2017. Grammatical gender in bilingual Norwegian-Russian acquisition: The role of input and transparency. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Nieto, Cecilia. 2003. Early acquisition of Spanish verb inflexion. A usage-based account. Psychology of Language and Communication 7: 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, Matthew. 2010. Child Language: Acquisition and Development. Sauzend Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenter, Scott A., and Rena Torres-Cacoullos. 2008. Defaults and Indeterminacy in Temporal Grammaticalization: The “Perfect” Road to “Perfective”. Language Variation and Change 20: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi L. 2023. Está Abriendo, La Abrió: Lexical Knowledge, Verb Type, and Grammatical Aspect Shape Child Heritage Speakers’ Direct Object Omission in Spanish. The International Journal of Bilingualism 27: 842–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi, Alejandro Cuza, and Liliana Sánchez. 2023. Structured variation, language experience, and crosslinguistic influence shape child heritage speakers’ Spanish direct objects. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 26: 317–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi, and Karen Miller. 2022. Children’s Acquisition of Morphosyntactic Variation. Language Learning and Development 18: 125–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi, Mariana Marchesi, and Jill P. Morford. 2021. Pathways of development in child heritage speakers’ use of Spanish demonstratives. Spanish as a Heritage Language 1: 222–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 2014. Bilingual Language Acquisition: Spanish and English in the First Six Years. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szagun, Gisela. 2011. Regular/irregular is not the whole story: The role of frequency and generalization in the acquisition of German past participle inflection. Journal of Child Language 38: 731–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thordardottir, Elin. 2015. The relationship between bilingual exposure and morphosyntactic development. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 17: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, Michael T. 2001. The declarative/procedural model of lexicon and grammar. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 30: 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Charles D. 2016. The Price of Linguistic Productivity: How Children Learn to Break the Rules of Language. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).