Abstract

This paper investigates the term “sea” (hai) in the four-character Chinese idioms according to conceptual metaphor and metonymy theory, attempting to illustrate their conceptualization, determine their possible underlying motivations, and explore Chinese maritime thought and culture. Based on idiomatic expressions, three types of conceptual metaphors are identified: abstract qualities of concrete entities are the sea, abstract entity is sea, and a certain aspect of a human being is sea. Moreover, the four types of conceptual metonymies are the part for the whole, the whole for the part, the place for the product, and the place for the responsible deities or goddesses. They are motivated by a culture of worship of and accordance with nature, the pursuit of achievements in traditional Chinese literature, “man paid, nature made” as the attitude towards the ups and downs of life, and a self-centered conceptualization of the world. The maritime culture represented in these conceptualizations comprises fear of and respect for the sea, harmony between humans and the sea, and static–dynamic integrations of river, land, and sea. The findings show that the motivations of these conceptualizations do not only originate from the embodiment and Chinese philosophy of the unity of heaven and humanity but are also constrained by the most influential talent selection mechanism, the Imperial Examination System, as well as by agriculture, the foundation of the economy in ancient China.

1. Introduction

Idioms play an important role in human languages, and are defined by Cambridge Dictionaries Online (2023) as “a group of words in a fixed order that has a particular meaning that is different from the meanings of each word on its own” (accessed on 30 May 2023), and “set phrases” or “fixed phrases” (Spears 2000). They contain an abundance of cultural implications, and the understanding of their connotations requires essential linguistic knowledge, as well as cultural information about the society from which they originated and in which they are used. Hence, mastering them constitutes a barrier for learners, and interpretation can be challenging for linguists. Generally, the major approaches to idiom studies fall into the three categories of the traditional, compositional, and cognitive perspectives. The first views idioms as syntactically fixed structures and semantically arbitrary chunks that function as conventional multi-word units (Hornby 2002; Richards and Schmidt 2013). The second contends that the literal meanings of the components of an idiom contribute to its idiomatic or figurative meanings, and their contributions vary in degree (Fernando 1996; Cristina et al. 2006). Both of these approaches maintain that idioms function at the linguistic level rather than the cognitive level. However, these views are challenged by cognitive semantics. Accordingly, the third cognitive approach treats idioms as the embodiment of human conceptualizations, which are grounded in human experiences of the world from within the bodies they inhabit. Therefore, idioms are motivated and predictable at a certain level, reflecting human cognition as well as providing a pathway to understanding cultural specificity (Kövecses 2005; Gibbs 1994). For this reason, idioms about the sea, which are largely figurative, offer one of the best ways to access and understand Chinese maritime culture, and conceptual metaphor and metonymy theories are applicable to their study (Kövecses and Szabco 1996; Gibbs et al. 1997; Gibbs 1990; Gibbs and O’Brien 1990; Gibbs and Nayak 1989).

In addition to their shared features with the idioms discussed from the three perspectives above, Chinese idioms are characterized by the dominance of four characters in lexical configurations. There are up to 45,000 Chinese idioms, and 96% of them are lexically composed of four Chinese characters (Zheng and Zhou 2019). The four syllables as two groups of twos in successions is another prominent feature of Chinese idioms (Wen 2005, p. 70). They are also characterized by enriched cultural meanings sourcing from parables and allegories, myths and legends, historical stories and events, ancient classical literary works, and folk colloquial sayings (Xu 2003). Some studies have even shown that Chinese tend to use more idioms than Westerners in daily communication (Zhang 2003; Jiang and Liao 2006; Liu 2018). Familiarity with idioms can also be helpful for the nonnatives in gaining credibility in Chinese society (Jiao et al. 2011, p. vi).

The Chinese character “海” (sea) first appeared in the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046–771 BC) (Rong et al. 1985). It has several synonyms in the ancient Chinese language, such as 天池 (sky-pool; heaven pool), 巨壑 (huge-gully; huge gully), 水王 (water-king; the king of water). However, only the character “海” (sea) withstands the force of evolution and manifests its great powers of productivity, while its synonyms have almost faded away and are rarely used in mandarin Chinese. The idioms containing such synonyms of the terms “海” (sea) cannot be founded in the database CNKI. Thus, we investigated the four-character Chinese idioms containing the term “sea” (hai) to reveal various aspects of Chinese maritime culture, as well as the underlying motivations of the conceptual metaphors and metonymies of the sea (hai). This study addresses the following four research questions: (1) what are the conceptual metaphors and metonymies underlying idioms of the “sea” (hai)? (2) How many idioms of the “sea” (hai) are distributed in conceptual metaphors and metonymies? (3) What are the underlying motivations of these conceptual metaphors and metonymies? (4) What is the nature of the Chinese maritime culture manifested by the idioms of the “sea” (hai)?

In what follows, first, conceptual metaphor and metonymy theory is briefly described as the framework for the analysis of idioms of the “sea” (hai) (Section 2). Second, the methodology and the data collection process are presented (Section 3). Third, the data are analyzed in the light of conceptual metaphor and metonymy theory (Section 4). Fourth, the motivations for these idioms and their relation to maritime culture are discussed (Section 5). Finally, the conclusions of this study are summarized (Section 6).

2. Background and Review of Conceptual Metaphor and Metonymy Theory

One of the basic tenets of cognitive semantics is that the structure of the human conceptual system is formed by human experience, derived from the interactions between their bodies and the world, mainly via moving and perceiving, which also can be referred to as embodiment (Gibbs et al. 2004; Gibbs 2021; Kövecses 2020; Lakoff and Johnson [1980] 2003). Cognitive linguists contend that “the very structure of reason itself comes from the details of our embodiment. The same neural and cognitive mechanisms that allow us to perceive and move around also create our conceptual systems and modes of reason” (Lakoff et al. 1999). Conceptual metaphor and metonymy are some of the results of this embodiment.

2.1. Conceptual Metaphor

Conceptual metaphor is not simply a rhetorical feature of language but rather a cognitive device for human thinking and acting, which can be used to structure, reconstruct, and even create reality. It is organized according to a target domain (a), which is usually less accessible through sensory perception, a source domain (b), which is, perceptually, more concrete and accessible, and cross-domain mappings or correspondences between the two conceptual domains, which can be represented by the formula a is b (Lakoff and Johnson [1980] 2003). Conceptual metaphor motivates linguistic expressions, and reflects the underlying conceptual system of the users of a certain language (Lakoff 1993; Kövecses 2010, 2020). Consider the four-character Chinese idioms沧海横流 and 四海波静, which literally mean “dark blue sea overflowing across” and “sea with waves calming down”, respectively; metaphorically, they correspond to states of war and peace in a country. The underlying concept of the two linguistic expressions is “a country is the sea”, in which the two typical states of motion and calmness in the sea are metaphorically mapped onto the states of a country at war and at peace. Such cross-domain mappings from the source domain “sea” to the target domain “country” are motivated by the experiences of Chinese people regarding the sea.

2.2. Conceptual Metonymy

Metonymy is a cognitive mechanism in which one conceptual entity, the vehicle, provides mental access to another conceptual entity, the target, within the single domain or matrix of domains (Kövecses 2010). It can be formulated as b for a, where B is the vehicle and A is the target, as contrasted with b for a in conceptual metaphor. Therefore, a metonymic relationship is built on reference and contiguity or conceptual proximity, which is motivated by the salience or emphasis of certain aspects of a domain (Evans 2006; Kövecses 2020). This is demonstrated by the four-character Chinese idiom 飘洋过海, which literally means “crossing ocean and sea” and metonymically refers to going to a foreign country, whereby “ocean” and “sea” stand for the whole process of travelling to another country. Here, “ocean” and “sea” are the vehicle, and “the whole process of travelling” is the target. A considerable amount of research has suggested that metonymy may be a more fundamental cognitive mechanism than metaphor (Kövecses and Radden 1998).

2.3. Previous Studies of Idioms Using the Approach of Conceptual Metaphors and Metonymies

This section reviews the relevant studies on the conceptualization of idioms from approaches to metaphors and metonymies in different languages. The idioms most commonly studied are mainly related to the following themes: (1) the human body (and body parts), (2) emotions, and (3) animals.

The conceptualization of idioms was explored in American English by Kövecses in 1996. His study piqued researchers’ interest in conducting similar studies in a variety of languages. For instance, the conceptualization of bodily idioms in different languages includes studies of the hand and face in Turkish by Hastürkoğlu (2018), the head, face, and eyes in English and Vietnamese by Vu et al. (2020), and the mouth, teeth, and tongue in Chinese by J. Chen (2010).

In addition, studies of the conceptualization of idioms of emotion have proven highly productive. Love is conceptualized as unity, closeness, choice, etc. (Giang 2023). Anger and happiness are structured by the obviously visible movements of the whole body in idioms in English and the less visible inwardness of movements of smaller body parts such as eyebrows, and even the invisible soul and vital energy in Chinese idioms (P. L. Chen 2010a, 2010b). In idioms of Greek and Bulgarian, surprise is represented as a loss of bodily control (Papadopulou 2018). The conceptualization of sadness in idioms of body parts in Turkish shows that the heart and liver or lung are more prevalent than idioms referring to other body parts (Baş and Büyükkantarcıoğlu 2019).

Humans and animals have a very close relationship. Some animals have been tamed by humans as labor forces, companions, or food sources. Dog idioms in both English and Chinese are used to describe human personalities and convey positive and negative meanings, and the distribution of negative senses (36%) in Chinese idioms is much higher than that seen in English (only 8%) (Wu and Zhao 2018). Idioms related to “tiger” in Chinese and “lion” in English tend to be identical in terms of their pure meaning. Chinese senses of “tiger” contain both goodness and badness, while “lion”, in Western cognition, is mostly good and admirable (Zhou 2005). Dragon idioms show that Chinese often hold this creature in positive regard, considering it in relation to divinity and worship (Wen and Chen 2021).

The research on idioms from the perspective of cognitive semantics largely focuses on the themes discussed above; most of these works are comparative, mainly comparing English with other languages to examine their similarities and differences. The findings of these studies support the ideas that conceptualization is not merely embodied but also culturally motivated, and that both body and culture play a role in the emergence of conceptual metaphors and metonymies (Kövecses 2015). Moreover, the evidence from this paper implies that social and economic systems also contribute to the conceptualization of language.

Drawing on the above literature, it seems that there are no reported studies of the conceptualization of the sea in Chinese idioms from the perspective of conceptual metaphor and metonymy. Hence, this study aims to contribute to the relevant literature by examining the four-character Chinese idioms containing the term “sea” (hai) to shed light on Chinese maritime culture and the elements motivating the conceptualization of the sea, aside from embodiment and culture, which have already been addressed in many studies.

3. Data Collection and Metaphor Identification Procedure

The data used in this study were collected from the most comprehensive database of Chinese academic studies, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (hereafter, “CNKI”), official portal http://gongjushu.cnki.net/rbook/ (accessed on 18 June 2023), which was constructed in 1999 for the purposes of academic research and knowledge transmission. It currently indexes about 4000 reference books including Chinese and bilingual dictionaries. For the sake of collection of data for this study, the following procedures were taken: firstly, the pattern “海 (sea)*”, “*海 (sea)”, and “*海 (sea)*”are to be taken as the keyword to retrieve the assigned database with the scope limited to the Chinese and bilingual dictionaries in which each asterisk stands for any Chinese characters in that position. The whole pattern means to retrieve all the expressions of containing the term “sea” (hai). Secondly, the idioms containing the term sea (hai) from the retrieved results are manually picked out based on the sources marked out by the database. Thirdly, the target data will be recorded in the document xls (version 97-2003), produced by Microsoft. All the four-character idioms containing the term sea (hai) in any position are extracted. As a result, a total of 309 four-character Chinese idioms containing the term sea (hai) were selected as the data for this study (seen Appendix A).

Based on the literal meaning, metaphorical meaning, and origins of the idioms, as well as their typical context of usage, three target domains of the “sea” (hai) in these idioms are identified: “abstract qualities of concrete entities”, “abstract entity”, and “a certain aspect of a human being”. Correspondingly, the three conceptual metaphors are abstract qualities of concrete entities are the sea, an abstract entity is the sea, and a certain aspect of a human being is the sea. The first one consists of three submetaphors: a literary article is the sea, calligraphy is the sea, and a large number of people and things are the sea. The second comprises five submetaphors: a country is the sea, life/one’s political career is the sea, a trend is the sea, difficulty is the sea, and a painful situation is the sea. The third also covers five submetaphors: appearance is the sea, longevity is the sea, fortune is the sea, an unreliable utterance is the sea, emotion is the sea, and cognition is the sea, which are used to describe one’s physical appearance, longevity, fortune, words or speeches, emotion, and cognition, respectively, as well the mind in general.

We also analyzed the metonymical meanings of the “sea” (hai) in these idioms, and four conceptual metonymies were identified: the part for the whole, the whole for the part, the place for the product, and the place for the responsible deities or goddesses. Below, we first illustrate each conceptual metaphor (Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3) and metonymy (Section 4.4) with examples and then analyze the distributions and frequencies of each type (Section 4.5).

4. Conceptual Analysis

4.1. abstract qualities of concrete entity are the sea

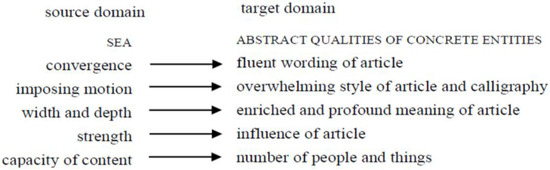

This metaphor consists of three submetaphors: a literary article is the sea, calligraphy is the sea, and a large number of people or things is the sea. The concrete entity (sea) is used to conceptualize the magnificent, flexible, and vigorous style of a literary article, calligraphy, or large number of people or things.

In the first submetaphor, a literary article is the sea, the attributes of rivers that imply motion, width, and depth, and the forces of the source domain “sea” are mapped onto the attributes of fluent wording, overwhelming style, enriched meaning, and the profound influence of a literary work. Such metaphorical mappings can be illustrated by 河奔海聚 (hereafter, the literal and metaphorical meanings will be separated by a semicolon) (rivers running and seas converging; the fluency of the wording of a literary work), 海立云垂 (the seas standing up and clouds hanging down; the literary work is imposing and overwhelming), 文江学海 (a work is like the Yangtse River and knowledge is like the sea; the profound meaning of a work and extensive knowledge), and 金翅擘海 (a kind of bird in Buddhism slapping the sea into two sections with its huge wings; the powerful and vigorous styles of literary works). The force of the sea is mapped onto the vigorous and elegant style of calligraphy in the second submetaphor calligraphy is the sea. The motivation of these two submetaphors originates from the most influential Chinese talent selection mechanism, the Imperial Examination System in ancient China, in which the quality of literary articles and calligraphy was taken as the standard for selecting candidates for national governance. Additionally, it promoted the thousand-year prosperity of ancient Chinese literature.

In the third submetaphor, a large number of people or things is the sea, bodily experiences of the substantial content, width, and depth in the horizontal and vertical space of the “sea” are mapped onto a large number of people, words, and speeches or actions and behaviors, food, wealth, books, meetings, and scales of things. These submetaphors can be demonstrated, respectively, by 人山人海 (a mountain and a sea of people; huge crowds of people), 河涸海干 (a dried river and sea; leaving no room for negotiation), 胡吃海喝 (eat and drink as much as a sea; eat and drink without restraint), 肉山酒海 (a mountain of meat and a sea of wine; an extreme abundance of food, especially in a feast), 堆山积海 (piles up like the mountain and the sea; a large amount of wealth), 浩如烟海 (as vast as a misty sea; a tremendous number of books), 文山会海 (mountains of documents and seas of meetings; too many documents and meetings), and 排山连海 (continuous mountains and seas; a large quantity of scales). The mappings of the three submetaphors are shown Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The metaphorical mappings of the conceptual metaphor abstract qualities of concrete entity are the sea.

4.2. An Abstract Entity Is the Sea

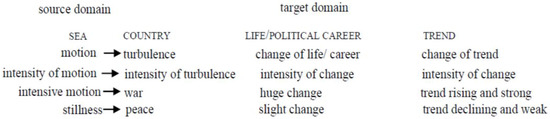

The five submetaphors in this category are a country is the sea, life/one’s political career is the sea, a trend is the sea, difficulty is the sea, and a painful situation is the sea. The first submetaphor, a country is the sea, involves three metaphorical mappings. The varied intensity of the motion of the “sea” is mapped onto the intensity of the turbulence in a country affected by wars (海水群飞: seawater surging; disorder in a country). The temperature is also used to conceptualize the intensity of wars in a country (海沸山裂: sea boiling and mountain cracking; a country is torn apart by war). The stillness of the “sea” is projected onto the peace of a country (海不扬波: no waves rising in the sea; a country is peaceful). The motivation for these submetaphors lies in the bodily experiences of the intensity of the motion or temperature of the “sea”, which are out of human control and threaten human lives, indicating that the war or peace in a country is always out of the control of the common people, although they are the ones who suffer the most.

The second submetaphor is life/one’s political career is the sea, in which the ups and downs experienced in life or a political career are projected onto the changes of the “sea”. This type is exemplified by 海水清浅 (the seawater becomes clean and shallow; things in life or in a political career are changeable and unpredictable), 东海扬尘 (the East China Sea turning into dusty land; human life changes significantly), and 沧海桑田 (dark-blue seas changing into fields of mulberry or crops; a life or career changing completely). These idioms record the changing processes of the “sea” from dim and deep to clean and shallow, then to dusty land, and finally to fields. The motion of the “sea” corresponds to the struggles and ups and downs of a political career, represented, respectively, by 宦海风波 (the wind and waves of the sea in a political circle; the struggles in political life) and 宦海浮沉 (floating and sinking in the political sea; the vicissitudes of the ups and downs of political life).

The third submetaphor, a trend is the sea, suggests that the unstoppable forces produced by the motion of the “sea” are projected onto the intensity of an irresistible trend. The greater the intensity of the trend, the more intense the motion of “sea”, and the less intense the irresistible trend, the less intense the motion of the sea, as conveyed by 翻江倒海 (overturned by rivers and seas; a trend is too powerful to resist) and 东海逝波 (the waves of the East China Sea are vanishing; a trend has been irretrievably lost).

The metaphorical mappings of the three submetaphors discussed above are all related to the motion of the “sea”, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The metaphorical mappings of the conceptual metaphors a country is the sea, life/one’s political career is the sea, and a trend is the sea.

In the fourth submetaphor, difficulty is the sea, the incredible width and depth of the sea are mapped onto the difficulties of journeys, successes, and the gap between people created by their social positions, as represented by, respectively, 航海梯山 (crossing a sea and climbing a mountain; a long and difficult journey), 擎天架海 (raise up the sky and cross the sea; extraordinary talents and the capacity to conquer the huge difficulties of accomplishing great missions), and 侯门如海 (the mansions of nobility are like a deep sea; the mansions of nobility are difficult for the common man to access). These idiomatic expressions of the submetaphor imply the significant difficulties in accomplishing great missions, suggesting that the talents required to complete them are well respected. They also express the alienation between friends or lovers that arises due to large gaps in social status.

The fifth submetaphor is a painful situation is the sea. It refers to the difficulties encountered in realizing one’s ambitions, insisting on one’s values, and having the indomitable will to combat a dangerous situation, as exemplified by, respectively, 海鳞未化 (the scales of a fish in the sea have not grown yet; the difficulty of realizing one’s ambitions), 鲁连蹈海 (Lulian jumped into the sea to kill himself; one insists on his own virtue and value, even to the point of losing his life), and 精卫填海 (the mythical bird Jingwei filling up the sea by carrying pebbles with her beak; an unshakeable will to face tough situations, even in vain). These idioms express positive sentiments that praise the qualities of loyalty, endurance, and bravery required to face difficult situations.

4.3. A Certain Aspect of a Human Being Is the Sea

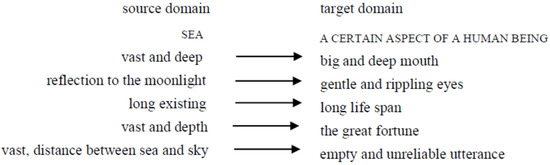

This metaphor comprises seven submetaphors: appearance is the sea, longevity is the sea, fortune is the sea, an unreliable utterance is the sea, emotion is the sea, and cognition is the sea. The first submetaphor, appearance is the sea, deals with the specific physical appearances of virtuous men and beautiful women, and it is used in a positive sense. Wide eyes and a big mouth are considered to be features of virtuous men. Gentle and shining eyes are regarded as aspects of the beauty of women. The examples of these metaphors are 河目海口 (river-like long eyes and a sea-like mouth; the distinguished appearance of a man) and 玉楼银海 (the shoulders are jade buildings, and the eyes are the silver sea; the appearance of a beautiful female).

The second and third submetaphors longevity is the sea and fortune is the sea are related to long lifespans and great fortune, respectively, in a positive sense. They can be evidenced by 海屋添筹 (counters recoding the changes of the sea into land or land into the sea increase; wish the respected elders long life) and 福如东海 (fortune as big as the China Eastern Sea; great fortune). In ancient China, most knowledge was acquired from the elders in a family and from hands-on experiences due to the limited channels of information transmission and the illiteracy that resulted from a lack of education opportunities. Usually, a farmer’s knowledge and experience of how to plant crops increased as he grew older. Thus, longevity is regarded as fortune. Moreover, the features of a long existence and the width and depth of the sea are mapped onto the long lifespan and great fortune of a person. Hence, both agricultural and bodily experiences motivate these metaphorical mappings.

The fourth submetaphor an unreliable utterance is the sea is concerned with the behaviors of boasting or boundless talking without a point. The unquantifiable distance between the sea and the sky is projected onto boundless and pointless talking and is further extended to the unreliability of utterances, as elaborated by 天南海北 (the sky is in the south and the sea is in the north; an unreliable utterance). The metaphorical mapping from the “sea” to the aspects of humans discussed above are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The metaphorical mappings of appearance is the sea, longevity is the sea, fortune is the sea, and an unreliable utterance is the sea.

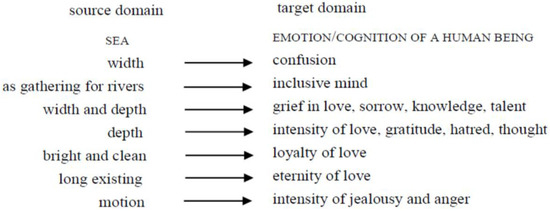

The fifth submetaphor, emotion is the sea, incorporates love is the sea, gratitude is the sea, hatred is the sea, sorrow is the sea, jealousy is the sea, and anger is the sea. Love is particularly pronounced. The width, depth, brightness and cleanness, and long existence of the “sea” are projected onto the extent, intensity, loyalty, and eternality of love, respectively, as shown by 情天泪海 (the sea of tears in love; the extent and intensity of grief in love), 情深似海 (love as deep as the sea; the intensity of love), 碧海青天 (a bright clean sea and an azure sky; the loyalty to love), and 山盟海誓 (oaths as firm as the mountains and vows as deep as the seas; the eternality of love). Gratitude and hatred are constructed as the depth of the sea, as described by 恩深似海 (gratitude as deep as the sea; the intensity of gratitude) and 血海深仇 (hatred as deep as the sea; the intensity of hatred). Sorrow is conceptualized according to the width and depth of the sea, for instance, in 愁海无涯 (the sea of sorrow is boundless; the extent of sorrow) and 愁山闷海 (sorrow as high as a mountain, as deep as the sea; the intensity of sorrow). Jealousy and anger are understood according to the motion of the sea, exemplified by 醋海生波 (the waves of a vinegar sea rising; jealousy caused by the love between men and women) and 海沸波翻 (the sea boiling and its waves rolling; the intensity of anger). The embodied experiences of the sea are mapped onto the emotions of love, gratitude, hatred, sorrow, jealousy, and anger in human beings.

The sixth submetaphor cognition is the sea involves confusion is the sea, knowledge is the sea, talent is the sea, thought is the sea, and mind is the sea. Sailing on the sea without navigation equipment was extremely challenging in ancient times. It is easy to lose one’s way, even for experienced sailors. This embodied experience is the motivation for the metaphor confusion is the sea, which expresses one’s confusion metaphorically (如堕烟海: like being lost on a foggy sea; confusion and being unable to get to the core of a problem). In the conceptual metaphors knowledge is the sea and talent is the sea, the width of the “sea” is mapped onto an abundance of knowledge and great talent, and in the conceptual metaphor thought is the sea, the depth of the sea is mapped onto the target domain to conceptualize the depth of a person’s thoughts, as demonstrated by 曾经沧海 (one experienced the wind and waves of the dark blue sea; a person with rich experiences does not pay attention to ordinary people or things), 学海波澜 (the big waves in the sea of knowledge; the talents in the world of literature), 才大如海 (talent as big as the sea; a great talent), and 海岳高深 (the sea is deep and the mountain is high; profound thought). All of these characteristics of human beings are thought to be virtuous and are promoted by the whole society.

The metaphorical mapping of mind is the sea is based on the nature of the “sea” as a gathering place for rivers. Specifically, the sea taking in every river and gathering them together maps onto the inclusive mind of a person who is open to and tolerant of different ideas and people and who learns from and absorbs their specific advantages (海纳百川: the sea takes in hundreds of rivers; an inclusive mind). The metaphorical mappings discussed above are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The metaphorical mappings of the conceptual metaphors emotion is the sea and cognition is the sea.

4.4. The Conceptual Metonymy of the Sea

The four conceptual metonymies are the part for the whole, the whole for the part, the place for the product, and the place for the responsible deities or goddesses. In the first metonymy, the part for the whole, “within (four) seas” and “outside (four) seas” stand for China and other countries, respectively. To the ancient Chinese, China constituted the Chinese mainland and the “four seas” located in the four different directions of the East, West, South, and North, which circled the mainland. Consequently, “within (four) seas” stands for China (囊括四海: including the four seas; the whole of China). The edges of the “four seas” are the boundaries of China and other countries. As a result, “outside (four) seas” stands for the sea stands for the whole process of travelling to a foreign country (漂洋过海: sail across the seas; go abroad). The idea of the “four seas” indicates that the ancient Chinese took China as the center when conceptualizing the world.

In the second metonymy, the whole for the part, the “sea” stands for uncertain, remote, and dangerous (hidden) locations, and the vast or free spirit realm, as demonstrated, respectively, by 石沉大海 (stones sinking into the sea; somebody or something disappearing to some place without news), 投山窜海 (cast into the mountain and the sea; exiled to some remote place), 放龙入海 (let the dragon return to the sea; leave the potential danger be), 春光如海 (the spring as wide and deep as sea; everywhere filled by spring), and 渔海樵山 (fishing in the sea and cutting wood on the mountain; live a reclusive life in some remote place). The idea of the sea as an uncertain and dangerous (hidden) location may originate from its extensive, intensive, and irresistible motion. Moreover, conceptualizing the “sea” as a space inhabited by free spirits may be inspired by its wide and empty surface without any obstacles while motionless.

In the third metonymy, the place for the product, the sea stands for its products, mainly salt and fish, as represented by 摘山煮海 (open mountains to extract copper and boil the sea for the salt) and 山珍海错 (delicious food from the mountain and the sea; an abundance of delicacies). In the fourth metonymy, the place for the responsible deities or goddesses, the sea stands for the deities and goddesses responsible for the affairs of the sea, as in 先河后海 (make sacrifice for the deities or goddesses of the river and then to those of the sea; distinguish between the primary and the secondary), which implies that the deities or goddesses of rivers are more important than those of the sea.

4.5. The Distribution of Idioms over Specific Conceptual Metaphors and Metonymies

In the previous sections, we discussed the relevant conceptual metaphors and metonymies and their mappings. However, it should be noted that there are significant variations in terms of distribution. For the sake of accuracy, we identified the types of metaphors and metonymies that every idiom belongs to according to their original and metaphorical meanings. The results are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The distributions of idioms across conceptual metaphors and metonymies.

Our analysis of the 309 idiomatic expressions has yielded the following findings, which can be observed from the metaphorical mappings (seen Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) and the distributions and frequencies of the idioms across each type of metaphor and metonymy (see Table 1).

The highlighted aspects of the source domain “sea” are its vast surface, depth, motion, and stillness, its changeability, its long almost eternal existence, its nature as a gathering place for rivers, and its remoteness, uncertainty, and danger (hidden). The unlimited width (depth) of the sea and the fact that it is too large to be quantified due to being a gathering place for all waters are utilized to conceptualize large numbers of people or things, physical traits (appearance and longevity), fortune, cognition (unreliable utterances, confusion, knowledge, talent, thought, and mind), and the intensity and extensiveness of emotions (love, gratitude, sorrow, jealousy, anger, and hatred). The uncontrollable motion and stillness of the sea are employed to conceptualize the imposing styles of literary works and calligraphy, the ups and downs of life and political careers, and the war or peace of a country. The unstoppable forces brought about by the motion of the sea are projected onto the irresistible trends of social movements. The sea changing into fields of mulberries and crops and vice versa are used to conceptualize the significant changes undergone by earthly things and political careers. The hardships of sailing on the sea are used to convey a difficult situation.

In terms of distributions and frequencies, the idioms ranked highest are themed around locations or spaces in which the sea is construed as vast and a space of spiritual freedom, as well as locations of uncertainty, remoteness, dangers (hidden), suffering, and obstacles. The number of such idioms totals 77, accounting for 24.92% of the total, as seen by the total numbers and frequencies of difficulty is the sea (14, 4.53%), a painful situation is the sea (7, 2.27%), and the whole for the part (56, 18.12%).

The following category contains idioms related to a country (China); there are up to 53 such idioms, comprising 17.15% of the total, as shown by the total and frequency of a country is the sea (36, 11.65%) and the part for the whole (17, 5.5%). The third most common idioms relate to the irresistible trends of social or other movements, with a quantity of 39, accounting for 12.62% of all the relevant idioms. The idioms ranked fourth focus on the individual pursuits of literature, knowledge, inclusive minds, and love; there are 54 such idioms, with a proportion of 17.48%, as evidenced by the totals and frequencies of a literary article is the sea (11, 3.56%), knowledge is the sea (11, 3.56%), mind is the sea (18, 5.83%), and love is the sea (14, 4.53%).

The last set of idioms that appear in significant quantities relate to unreliable utterances, changes in one’s political career and in life, and the eternity of love. There are 34 such idioms, making up 11% of the total, as evidenced by an unreliable utterance is the sea (9, 2.91%) and life/one’s political career is the sea (11, 3.56%).

5. Discussion

In this section, we first discuss the potential motivations underlying the conceptual metaphors and metonymies of the idioms containing the term “sea”. Then, we explore the aspects of maritime culture represented in these idioms.

5.1. The Motivations of Conceptual Metaphors and Metonymies

5.1.1. The Culture of the Family Country

The culture of family country is an important component of traditional Chinese culture, in which it plays an important role in moral education, order maintenance, morality shaping, social governance, and civilization inheritance (Tian and Yang 2023). The culture of family is the cornerstone and even core of Chinese national culture (Chen and Chen 2022). In the spiritual world of Chinese people, individuals, and society, family and country are all integrated together and cannot be separated (Liu and Nie 2021). These ideas are manifested by the fact that the Chinese word “国” (guo, country) is often used with “家” (jia, family), and they are seldom separated. It literally means “country family” in English, signaling the significance of the country to the common people. The importance of family-country culture is also displayed by the quantities of idioms expressing the conceptual metaphor a country is the sea, which is distributed across 53 idioms and constitutes 17% of the total number, ranking second. It conveys that the people are eager for peace and care about the fate of the country just like being concerned with their own safety and fate, which is grounded in the ideology of family–country integration and interdependence. In summary, the idea of the country, families, and individuals being interdependent and integrated together are manifested well in the idioms. The motivation of the family country that underpins many idioms may be rooted in the fact that the political stability and peace of a country are prerequisites for planting and harvesting crops.

5.1.2. The Culture of Accordance with Nature

“Ziran” (自然) is one of the core concepts of Taoist philosophy, which is translated as being natural, its own course, or spontaneous in English by Roger T. Ames (2004). It roughly refers to the objective rules and laws of the world itself (Gu and Huang 2022). The core of accordance with nature (顺其自然) is to pursue the unity and harmony of heaven and man (Tao 2019), which is illustrated well by the idioms distributed across the conceptual metaphor a trend is the sea (the total quantity up to 39, accounting for 12.62% and ranking third). Such idioms convey that natural trends are hard to disobey. Humans should worship nature and behave in accordance with it. This does not mean that humans should give up without making any effort. Rather, what humans should do is act or behave according to the rules of nature and let nature decide. The fundamental aspect of accordance with nature can be summarized as “man paid; nature made”, which is likely motivated by the fact that agriculture is particularly dependent on nature, e.g., favorable weather and climates, rainfall when required, and sowing at the appropriate times. The metaphor then moves beyond the field of agriculture and becomes a highly important mechanism of psychological adjustment, which enables people to be enterprising as well as accepting their failures. Furthermore, the realities of farming also contribute to the key ideologies of the “unity of heaven and man” and “all in the universe connected together” in traditional Chinese philosophy, which is based on the long-term observations of the relationship between heaven and humanity.

5.1.3. Values and Pursuits

Among the things that are valued in Chinese life, the most valuable are abundant knowledge of and achievements in traditional Chinese literature and calligraphy, as shown by the conceptual metaphors a literary work is the sea and calligraphy is the sea, which can be attributed to the Imperial Examination System. This system lasted for about 1300 years and was initially used to select highly talented people to administer the country in ancient China. Moreover, the quality of a literary work, manifested by literary achievements, was used as one of the most important standards for selecting the candidates, which offered a reliable opportunity and effective path for the powerless ordinary people to change their fate (Wu 1999). This explains the fact that the government officials were also the greatest literary writers at the time. The Imperial Examination System was so influential that it largely promoted the continuous prosperity and shaped the values and pursuits of the Chinese people, such as persisting in one’s reading and studies of literature despite the impoverished material life for a better potential future (Fu 1984; Zhuge 2010; Wang 2016). Evidently, the pursuit of achievements in literature and calligraphy can be traced back to this social system.

5.1.4. The Attitude to Life

The ancient Chinese view is that all things on earth are changeable, without a fixed mode; hence, it is impossible to predict what will happen. This is also true for people’s lives and political careers, which are full of ups and downs, as can be observed in the sub-metaphor life/one’s political career is the sea. As for the things that are out of one’s control, it is necessary to “act or behave according to nature”, which is motivated by the culture of harmony and peacefulness with natural rules or laws as discussed in Section 5.1.2. Unlike the other submetaphors, an unreliable utterance is the sea is used in a strongly negative sense, which suggests that the ancient Chinese placed more value on putting words into practice than on words alone. This attitude to life is motivated by the features of agriculture, such as “no pains, no gains”, which requires step-by-step labor in accordance with the timing and natural seasons rather than waiting for chances, because any steps missed may be harmful to grain harvest (Wen and Chen 2021; Wang 2023).

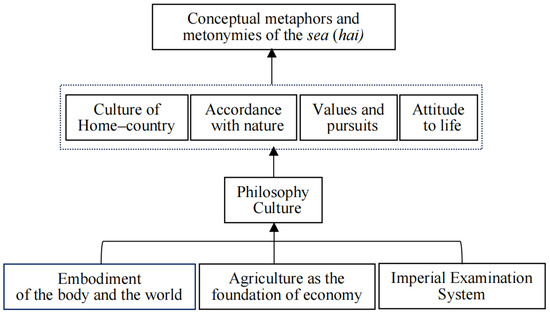

To sum up, the direct motivations underlying these conceptual metaphors and metonymies are the culture of the family country, accordance with nature, values and pursuits, and attitudes toward life. They are all based on agriculture as the economic foundation of ancient China and the social system of the Imperial Examination System as the mechanism for talent selection. The motivations of such cognitive conceptualizations are not only constrained by embodiment, based on the bodily interactions between humans and the world, but are also constrained by the country’s economic foundations and social systems, which are more fundamental than its culture. The elements that determine the motivations of the conceptual metaphors and metonymies of the sea (hai) are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The elements that determine the conceptual metaphors and metonymies.

5.2. The Maritime Culture Represented by Conceptual Metaphors and Metonymies

The sea is conceptualized as a vast space associated with spiritual freedom, as well as locations of uncertainty, remoteness, dangers (hidden), suffering, and obstacles. There are 77 idioms distributed across the related conceptual metaphors and metonymies, accounting for 24.92% of the total number and ranking first. In this sense, the sea is endowed with both positive and negative meanings. On the one hand, Chinese people are attracted to the charm of the sea. On the other hand, they are scared of the danger and uncertainty associated with it. They harbor feelings of fear of and respect for the sea (An 2010; An and Liu 2012).

The sea changing into fields of mulberries and crops and vice versa is predicated on the significant changes undergone by things on earth and on the ups and downs of political life (life/one’s political career is the sea). The sea is also the gathering place for the rivers that run into it, which is the motivation behind the conceptual metaphor the mind is the sea. These idioms indicate perceptions of the static–dynamic integration of rivers, land and sea, and the inclusiveness and tolerance of Chinese maritime culture (Lin and Tang 2014; Xu 2021).

The sea is a vast space that facilitates spiritual freedom; as noted above, this refers to the harmony between humans and the sea. This exemplifies the ideology of a culture of accordance with nature and the doctrines of the “unity of heaven and man” and “all in the universe connected together” seen in traditional Chinese philosophy (An 2013; Ouyang 2017).

6. Conclusions and Prospects

In this study, we investigated the conceptualizations of the term “sea” in Chinese idioms. The three categories of conceptual metaphors identified are: abstract qualities of concrete entities are the sea, an abstract entity is the sea, and certain aspects of a human being are the sea. The four conceptual metonymies are: the part for the whole, the whole for the part, the place for the product, and the place for the responsible deities or goddesses.

From the perspective of cognitive conceptualization, we investigated the metaphorical and metonymical meanings of sea. The analysis suggests that the conceptualization of the term “sea” (hai) in four-character Chinese idioms is motivated by the views of the unity of heaven and humanity in traditional philosophy, the culture of country–family and accordance with nature, the valuing and pursuit of literary achievements, and the attitudes to the ups and downs in political careers and in life, which may originate from the reality of agriculture being the foundation of the economy and from the Imperial Examination System, which was used as the talent selection mechanism in ancient China.

We also explored the maritime culture represented in these idioms. The findings show that the ancient Chinese had complicated feelings towards the sea. On the one hand, they were attracted to the sea; on the other, they had a strong sense of its (potential) dangers. Thus, they harbored feelings of fear of and respect for the sea. They also perceived the static and dynamic integration of the rivers, land, and sea. Moreover, these idioms suggest that humanity can have a harmonious relationship with the sea. Maritime culture is a specific manifestation of the general ideologies of the “unity of heaven and man”, “all in the universe connected together”, “the harmony of man and nature”, and “nature worship” seen in Chinese traditional philosophy, which are largely shaped by the realities of agriculture being the economic foundation of ancient China. The results suggest that the motivations of cognitive conceptualization are not only constrained by the bodily interactions between humans and the world but are also constrained by the economic foundations and social systems of the country, which are the foundations by which culture is motivated.

The embodied basis of human beings’ interactions with the world in which they live is emphasized as the basic mechanism of cognitive conceptualization. However, other elements, such as social systems, have not yet been foregrounded in the relevant studies. Future research can be extended to include cross-linguistic and empirical studies related to the term “sea” in different cultures across different historical periods, so as to further develop the conceptual metaphor theory to include social and cultural factors, making it a more powerful interpretative framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, data analysis, investigation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, N.F.M.N.; supervision, I.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Development Program for the Yong Teachers in Universities of Guangxi, grant number: 2020KY10009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request to the first author.

Acknowledgments

We are appreciative to the Department of Guangxi Education, Guangxi, China, for funding this research through the Research Development Program for the Yong Teachers in Universities of Guangxi. We also acknowledge the constructive comments by the three anonymous reviewers and editors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. The Four-Character Chinese Idioms Related to the Sea

| 1 | 海立云垂 | 66 | 搅海翻江 | 131 | 天空海阔 | 196 | 量如江海 | 261 | 情天孽海 |

| 2 | 云垂海立 | 67 | 搅海翻天 | 132 | 海阔天高 | 197 | 江海同归 | 262 | 孽海情天 |

| 3 | 韩潮苏海 | 68 | 荡海拔山 | 133 | 情天泪海 | 198 | 囊括四海 | 263 | 黑风孽海 |

| 4 | 苏海韩潮 | 69 | 覆海移山 | 134 | 碧海青天 | 199 | 囊扩四海 | 264 | 辞金蹈海 |

| 5 | 韩海苏潮 | 70 | 倒海移山 | 135 | 情深似海 | 200 | 五湖四海 | 265 | 鲁连蹈海 |

| 6 | 潘江陆海 | 71 | 移山倒海 | 136 | 情深如海 | 201 | 九州四海 | 266 | 蹈海之节 |

| 7 | 陆海潘江 | 72 | 压山倒海 | 137 | 盟山誓海 | 202 | 五洲四海 | 267 | 精卫填海 |

| 8 | 潘陆江海 | 73 | 排山倒海 | 138 | 海誓山盟 | 203 | 四海九州 | 268 | 精禽填海 |

| 9 | 文江学海 | 74 | 移山拔海 | 139 | 誓海盟山 | 204 | 四海之内 | 269 | 衔沙填海 |

| 10 | 河奔海聚 | 75 | 移山竭海 | 140 | 海盟山咒 | 205 | 海水一泓 | 270 | 衔石填海 |

| 11 | 金翅擘海 | 76 | 移山回海 | 141 | 海约山盟 | 206 | 志在四海 | 271 | 春光如海 |

| 12 | 群鸿戏海 | 77 | 移山填海 | 142 | 山盟海誓 | 207 | 名扬四海 | 272 | 春深似海 |

| 13 | 飞鸿戏海 | 78 | 移山造海 | 143 | 誓山盟海 | 208 | 扬名四海 | 273 | 江南海北 |

| 14 | 胡打海摔 | 79 | 移山跨海 | 144 | 海涸石烂 | 209 | 富有四海 | 274 | 大海捞针 |

| 15 | 山吃海喝 | 80 | 摧山搅海 | 145 | 石烂海枯 | 210 | 纵横四海 | 275 | 大海捞针 |

| 16 | 胡吃海塞 | 81 | 回山倒海 | 146 | 石泐海枯 | 211 | 云游四海 | 276 | 大海一针 |

| 17 | 胡吃海喝 | 82 | 拔山超海 | 147 | 恩山义海 | 212 | 海岱清士 | 277 | 海底捞针 |

| 18 | 瓮天蠡海 | 83 | 倒山倾海 | 148 | 义海恩山 | 213 | 四海他人 | 278 | 东海捞针 |

| 19 | 持蠡测海 | 84 | 跨山压海 | 149 | 义山恩海 | 214 | 四海为家 | 279 | 海中捞月 |

| 20 | 以蠡测海 | 85 | 转海回天 | 150 | 恩深似海 | 215 | 四海飘零 | 280 | 钻山塞海 |

| 21 | 文山会海 | 86 | 山奔海立 | 151 | 愁山闷海 | 216 | 四海一家 | 281 | 挟山超海 |

| 22 | 肉山酒海 | 87 | 山呼海啸 | 152 | 闷海愁山 | 217 | 海内无双 | 282 | 入海算沙 |

| 23 | 堆山积海 | 88 | 山崩海啸 | 153 | 云悲海思 | 218 | 眼空四海 | 283 | 涉海凿河 |

| 24 | 浩如烟海 | 89 | 海啸山崩 | 154 | 云愁海思 | 219 | 目空四海 | 284 | 河清海竭 |

| 25 | 浩若烟海 | 90 | 气吞湖海 | 155 | 愁海无涯 | 220 | 四海横流 | 285 | 一毛吞海 |

| 26 | 连山排海 | 91 | 汪洋大海 | 156 | 醋海生波 | 221 | 四海鼎沸 | 286 | 海枯见底 |

| 27 | 排山连海 | 92 | 东海逝波 | 157 | 醋海翻波 | 222 | 海内鼎沸 | 287 | 龙归大海 |

| 28 | 如山似海 | 93 | 沧海一粟 | 158 | 醋海波澜 | 223 | 祸延四海 | 288 | 江海之士 |

| 29 | 河落海干 | 94 | 沧海一鳞 | 159 | 海沸波翻 | 224 | 威动海内 | 289 | 乘桴浮海 |

| 30 | 河涸海干 | 95 | 逾山越海 | 160 | 海沸江翻 | 225 | 四海安危 | 290 | 浮泛江海 |

| 31 | 沧海横流 | 96 | 涉海登山 | 161 | 海沸河翻 | 226 | 四海承平 | 291 | 渔海樵山 |

| 32 | 海沸山摇 | 97 | 航海梯山 | 162 | 恨海难填 | 227 | 四海升平 | 292 | 海怀霞想 |

| 33 | 海沸山裂 | 98 | 栈山航海 | 163 | 尸山血海 | 228 | 四海昇平 | 293 | 海上鸥盟 |

| 34 | 海沸山崩 | 99 | 梯山航海 | 164 | 血海尸山 | 229 | 四海承风 | 294 | 摘山煮海 |

| 35 | 海水群飞 | 100 | 山行海宿 | 165 | 血海深仇 | 230 | 海内澹然 | 295 | 铸山煮海 |

| 36 | 东海鲸波 | 101 | 漫天过海 | 166 | 血海冤仇 | 231 | 海内淡然 | 296 | 山珍海错 |

| 37 | 海晏河清 | 102 | 侯门如海 | 167 | 曾经沧海 | 232 | 四海晏然 | 297 | 山珍海味 |

| 38 | 海晏河澄 | 103 | 侯门似海 | 168 | 学海波澜 | 233 | 四海波静 | 298 | 山珍海胥 |

| 39 | 河清海晏 | 104 | 擎天架海 | 169 | 学海无涯 | 234 | 海外扶余 | 299 | 山海之味 |

| 40 | 河海清宴 | 105 | 檠天架海 | 170 | 学海无边 | 235 | 扶余海外 | 300 | 山肴海错 |

| 41 | 河溓海晏 | 106 | 檠天驾海 | 171 | 道山学海 | 236 | 飘洋过海 | 301 | 海错江瑶 |

| 42 | 河清海宴 | 107 | 架海擎天 | 172 | 如江如海 | 237 | 飘洋航海 | 302 | 后海先河 |

| 43 | 河溓海夷 | 108 | 架海金梁 | 173 | 江海之学 | 238 | 石沉大海 | 303 | 先河后海 |

| 44 | 时清海宴 | 109 | 海鳞未化 | 174 | 地负海涵 | 239 | 石投大海 | 304 | 枕山负海 |

| 45 | 海不扬波 | 110 | 芒芒苦海 | 175 | 海涵地负 | 240 | 大海沉石 | 305 | 枕山襟海 |

| 46 | 海波不惊 | 111 | 苦海无边 | 176 | 法海无边 | 241 | 泥牛入海 | 306 | 凭山负海 |

| 47 | 海不波溢 | 112 | 苦海无涯 | 177 | 如堕烟海 | 242 | 冤沉海底 | 307 | 海市蜃楼 |

| 48 | 宦海浮沉 | 113 | 苦海茫茫 | 178 | 才大如海 | 243 | 珠沉沧海 | 308 | 蜃楼海市 |

| 49 | 宦海风波 | 114 | 无边苦海 | 179 | 如江如海 | 244 | 珠沉沧海 | 309 | 海翁失鸥 |

| 50 | 海水清浅 | 115 | 生死苦海 | 180 | 海水难量 | 245 | 海角天涯 | ||

| 51 | 海浅蓬莱 | 116 | 河目海口 | 181 | 海岳高深 | 246 | 天涯海角 | ||

| 52 | 东海扬尘 | 117 | 银海生花 | 182 | 原宥海涵 | 247 | 海涯天角 | ||

| 53 | 沧海桑田 | 118 | 玉楼银海 | 183 | 宽洪海量 | 248 | 海角天隅 | ||

| 54 | 桑田沧海 | 119 | 海屋添筹 | 184 | 海涵春色 | 249 | 海涯天隅 | ||

| 55 | 海水桑田 | 120 | 海屋筹添 | 185 | 海涵春育 | 250 | 山南海北 | ||

| 56 | 桑田碧海 | 121 | 寿山福海 | 186 | 湖海之士 | 251 | 山陬海澨 | ||

| 57 | 海生桑田 | 122 | 福如东海 | 187 | 山包海容 | 252 | 山陬海筮 | ||

| 58 | 海桑陵谷 | 123 | 福如海渊 | 188 | 山包海汇 | 253 | 山陬海噬 | ||

| 59 | 翻江倒海 | 124 | 海说神聊 | 189 | 山容海纳 | 254 | 东洋大海 | ||

| 60 | 翻江搅海 | 125 | 胡吹海嗦 | 190 | 海纳百川 | 255 | 放龙入海 | ||

| 61 | 倒海翻江 | 126 | 河门海口 | 191 | 百川归海 | 256 | 放鱼入海 | ||

| 62 | 江翻海倒 | 127 | 胡吹海嗙 | 192 | 百川赴海 | 257 | 火山汤海 | ||

| 63 | 江翻海沸 | 128 | 天南海北 | 193 | 百川朝海 | 258 | 刀山火海 | ||

| 64 | 江翻海搅 | 129 | 海北天南 | 194 | 众流归海 | 259 | 火海刀山 | ||

| 65 | 江翻海扰 | 130 | 海阔天空 | 195 | 众川赴海 | 260 | 刀山血海 |

References

- Ames, Roger T. 2004. Indigenizing Globalization and the Hydraulics of Culture: Taking Chinese Philosophy on its Own Terms. Globalizations 1: 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Jun L. 安俊丽. 2010. Cultural perspective on the sea related idioms (“涉海”成语的文化透视). Journal of Changzhou Institute of Technology (Social Science) (常州工学院学报<社科版>) 28: 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- An, Jun L. 安俊丽. 2013. Influence on Chinese maritime culture by traditional ideology (传统哲学思想对中国海洋文化的影响). Journal of Yancheng Teachers University (Humanities & Social Sciences) (盐城师范学院学报<人文社会科学版>) 33: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- An, Jun L. 安俊丽, and Yang Liu 刘扬. 2012. Similarities and differences of Chinese and western ocean cultures based on proverbs (基于谚语的中西方海洋文化差异研究). Journal of Jiangsu Ocean University (Humanities & Social Sciences) (淮海工学院学报<人文社会科学>版) 10: 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baş, Melike, and Nalan Büyükkantarcıoğlu. 2019. Sadness metaphors and metonymies in Turkish body part idioms. Dilbilim Araştırmaları Dergisi 2: 273–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionaries Online. 2023. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/idiom?q=idioms (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Chen, Jie. 2010. A cognitive approach to the comparative study of mouth organs in Chinese and English idioms. Journal of Changchun Normal University 6: 137–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Pei L. 2010a. A cognitive study of “anger” metaphors in English and Chinese idioms. Asian Social Science 6: 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, Pei L. 2010b. A cognitive study of “happiness” metaphors in English and Chinese idioms. Asian Culture and History 2: 172–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yan B. 陈延斌, and Shu J. Chen 陈姝瑾. 2022. Traditional Family culture: Status, connotation and time value (中国传统家文化:地位、内涵与时代价值). Journal of Hunan University (Social Sciences) (湖南大学学报<社会科学版>) 36: 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cristina, Cacciari, Fabiola Reati, Maria Rosa Colombo, Roberto Padovani, Silvia Rizzo, and Costanza Papagno. 2006. The comprehension of ambiguous idioms in aphasic participants. Neuropsychologia 44: 1305–14. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Vyvyan. 2006. Cognitive Linguistics. Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, Chitra. 1996. Idioms and Idiomaticity. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Xuan C. 傅璇琮. 1984. The Life of Literati under the Tang Dynasty Imperial Examination System (唐代科举制度下的文人生活). Journal of Zaozhuang University (枣庄师专学报) 1: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Giang, Dang N. 2023. Vietnamese Concepts of Love Through Idioms: A Conceptual Metaphor Approach. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 13: 855–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr., and Nandini P. Nayak. 1989. Psycholinguistic studies on the syntactic behavior of idioms. Cognitive Psychology 21: 100–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. 1990. Psycholinguistic studies on the conceptual basis of idiomaticity. Cognitive Linguistics 1–4: 417–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. 1994. The Poetics of Minds: Figurative Thought, Language, and Understanding. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. 2021. Metaphorical Embodiment. In Handbook of Embodied Psychology: Thinking, Feeling, and Acting. Edited by D. Robinson Michael and Laura E. Thomas. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 101–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr., and Jennifer E. O’Brien. 1990. Idioms and mental imagery: The metaphorical motivation for idiomatic meaning. Cognition 36: 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr., Josephine M. Bogdanovich, Jeffrey R. Sykes, and Dale J. Barr. 1997. Metaphor in Idiom Comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language 37: 141–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr., Paula Lenz Costa Lima, and Edson Francozo. 2004. Metaphor is grounded in embodied experience. Journal of Pragmatics 36: 1189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Zhong T. 顾中婷, and Ai G. Huang 黄爱国. 2022. The Application of the Going-with-the-flow model in Psychotherapy (顺其自然模型在心理治疗中的应用). Journal of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Social Science) (南京中医药大学学报<社会科学版>) 23: 191–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hastürkoğlu, Gökçen. 2018. A Cognitive and Cross-Cultural Study on Body Part Terms in English and Turkish Colour Idioms. Studies in Linguistics, Culture, and FLT 4: 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, Albert Sydney, ed. 2002. Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. Beida Li, trans. Shanghai: The Commercial Press. Cambridge: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Cheng S., and Ding Liao Z. Liao. 2006. A Review of the Studies of Idioms in Both Chinese and English from a Perspective of Cognitive Linguistics (汉英成语的认知语言学研究述评). Journal of Guangdong University of Technology (Social Sciences Edition) (广东工业大学学报<社会科学版>) 6: 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Li W., C. Kubler Cornelius, and Wei G. Zhang. 2011. 500 Common Chinese Idioms: A Frequency Dictionary. London and New York: Routledge, pp. vii–viii. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2005. Metaphor in Culture: Universality and Variation. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2010. Metaphor and culture. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica 2: 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2015. Where Metaphors Come from: Reconsidering Context in Metaphor. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2020. Extended Conceptual Metaphor Theory. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán, and Günter Radden. 1998. Metonymy: Developing a Cognitive Linguistic View. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán, and Peter Szabco. 1996. Idioms: A view from cognitive semantics. Applied Linguistics 17: 326–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 2003. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, Mark Johnson, and John F. Sowa. 1999. Review of Philosophy in the Flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. Computational Linguistics 25: 631–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1993. The contemporary theory of metaphor. In Metaphor and Thought. Edited by Andrew Ortony. London: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Jia Q. 林加全, and Tian Y. Tang 唐天勇. 2014. On Constructing Harmonious Culture of Occean-Human (人海和谐海洋文化及其构建理路探究). Journal of Xi’an University (Social Sciences) (西安文理学院学报<社会科学版>) 17: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yang. 2018. A Review of Cognitive Research on Chinese Idioms (汉语成语认知研究述评). Journal of Anqing Normal University (Social Science Edition) (安庆师范学院学报 <社会科学版>) 037: 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yu L. 刘余莉, and Fei L. Nie 聂菲璘. 2021. The Spiritual Realm, Historical and Cultural Connotations of Family and Country (家国情怀的精神境界与历史文化内涵). Gansu Social Sciences (甘肃社会科学) 5: 152–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Yan 欧阳焱. 2017. The Inclusiveness, Harmony, and Innovation of Chinese Maritime Culture (中国海洋文化的包容和谐与开拓创新). People’s Tribune (人民论坛) 34: 140–41. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopulou, Sotiria. 2018. Comparative Analysis of Modern Greek and Bulgarian’s Surprise-expressing Idioms from Cognitive Perspective. Филoлoгически фoрум 4: 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Jack C., and Richard W. Schmidt. 2013. Longman Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Geng, Zhen L. Zhang, and Guo Q. Ma, eds. 1985. A Compile Book of Inscriptions on Ancient Bronze Objects (金文编). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, p. 733. [Google Scholar]

- Spears, Richard A. 2000. NTC’s American Idioms Dictionary: The Most Practical Reference for the Everyday Expressions of Contemporary American English. New York: NTC Publishing Group, p. xi. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Jin L. 陶金玲. 2019. Education is to let nature take its course (教育即顺其自然). Journal of Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University (陕西学前师范学院学报) 35: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Xu M. 田旭明, and Zheng M. Yang 杨正梅. 2023. Interpretation and practice of the Chinese family culture in the new era (中华家国文化的新时代阐发与实践). Academic Journal of Zhongzhou (中州学刊) 3: 115–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, Nguyen Ngoc, Nguyen Thi Thu Van, and Nguyen Thi Hong Lien. 2020. Cross-linguistic Analysis of Metonymic Conceptualization of Personality in English and Vietnamese Idioms Containing “Head”, “Face” and “Eyes”. International Journal of English Language Studies 2: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wen J. 2016. The Influence of the Imperial Examination System on the Literature of the Tang Dynasty (浅析科举制度对唐代文学的影响). Journal of Gansu Radio & Television University (甘肃广播电视大学学报) 26: 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yan 王琰. 2023. The Ideological Meaning, Era Value, and Inheritance Path of Chinese Excellent Traditional Agricultural Culture (中华优秀传统农耕文化的思想意涵、时代价值及传承路径). Theoretical Investigation (理论探讨) 5: 105–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Duan Z. 2005. Chinese Phraseology (汉语语汇学). Beijing: The Commercial Press, p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Xu, and Chuan H. Chen. 2021. Cultural conceptualizations of Loong (龙) in Chinese idioms. Review of Cognitive Linguistics 19: 563–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Rui X., and Zu R. Zhao. 2018. A Comparative Study on Conceptual Metaphors Between English and Chinese Dog Idioms. International Journal of Arts and Commerce 7: 125–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Zai Q. 吴在庆. 1999. The Influence of the Imperial Examination System on Tang Dynasty Literature (科举制度对唐代文学的影响). Journal of Xiamen University (Arts & Social Sciences) (厦门大学学报<哲学社会科学版>) 4: 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Ji H. 徐续红. 2003. On the Classification of Idioms (成语分类问题研究). Journal of Yichun University (Social Science) (宜春学院学报) <社会科学> 25: 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Wen Y. 徐文玉. 2021. Maritime Culture and the Building of “a Maritime Community with a Shared Future” (海洋文化与“海洋命运共同体”的构建). Journal of Jimei University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) (集美大学学报<哲学社会科学版>) 24: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. 2003. Idioms and Their Comprehension: A Cognitive Semantic Perspective. Beijing: Military Yiwen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Wei L., and Qian Zhou. 2019. 中华成语大词典 (Complete Collections for Chinese Idioms). Beijing: The Commercial Press International Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Hong 周红. 2005. A Comparative Study of Chinese “Hu” Idioms and English “Lion” Idioms from the Cognitive Perspective. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuge, Yi B. 诸葛忆兵. 2010. The Imperial Examination System and Literary Creation (科举制度与文学创作). Journal of Tsinghua University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) (清华大学学报<哲学社会科学版>) 25: 43–46. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).