Abstract

A large body of cross-linguistic research has shown that complex constructions, such as subordinate constructions, are vulnerable in bilingual DLD children, whereas they are robust in bilingual children with typical language development; therefore, they are argued to constitute a potential clinical marker for identifying DLD in bilingual contexts, especially when the majority language is assessed. However, it is not clear whether this also applies to heritage contexts, particularly in contexts in which the heritage language is affected by L2 contact-induced phenomena, as in the case of Heritage Turkish in Germany. In this study, we compare subordination using data obtained from 13 Turkish heritage children with and without DLD (age range 5; 1–11; 6) to 10 late successive (lL2) BiTDs (age range 7; 2–12; 2) and 10 Turkish adult heritage bilinguals (age range 20; 3–25; 10) by analyzing subordinate constructions using both Standard and Heritage Turkish as reference varieties. We further investigate which background factors predict performance in subordinate constructions. Speech samples were elicited using the sentence repetition task (SRT) from the TODİL standardized test battery and the Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives (MAIN). A systematic analysis of a corpus of subordinate clauses constructed with respect to SRT and MAIN narrative production comprehension tasks shows that heritage children with TD and DLD may not be differentiated through these tasks, especially when their utterances are scored using the Standard Turkish variety as a baseline; however, they may be differentiated if the Heritage Turkish is considered as the baseline. The age of onset in the second language (AoO_L2) was the leading performance predictor in subordinate clause production in SRT and in both tasks of MAIN regardless of using Standard Turkish or Heritage Turkish as reference varieties in scoring.

1. Introduction

Developmental language disorder (DLD) is the term recommended by the international CATALISE consortium (Bishop et al. 2016, 2017) to replace specific language impairment (SLI) to refer to language deficits that are considered a public health concern (Law et al. 2013), pose obstacles to educational and/or social functioning, and carry over into middle childhood and beyond (Stothard et al. 1998; Tomblin 2008; Yew and O’Kearney 2013; Durkin et al. 2015). Language difficulties in children with DLD are observed in the absence of any known biomedical condition, such as brain injury, neurodegenerative conditions, genetic conditions, or chromosome disorders (Bishop et al. 2016, 2017). The comprehension and production of complex language, including morphosyntax, phonology, semantics, and pragmatics, are affected by DLD (Leonard 2014; Bishop et al. 2017). Researchers have estimated the prevalence of language disorders among school-age children at 5–7% (Tomblin et al. 1997), which would carry over to bilingual children for whom both languages would be affected.

Bilingual children acquiring a heritage language (HL) and a majority second language (L2) differ from same-age monolingual peers in several aspects. This difference may result from different factors, such as the typology of the HL and the L2; the age of first systematic contact with the L2, which is called the age of onset (AoO_L2); the length of exposure to the L2 (LoE_L2); the quantity and quality of input in HL and L2; the language status; and the socioeconomic status (SES) of the parents (Paradis 2023). Due to these differences, several studies have reported that employing L1 tests in heritage contexts is problematic (e.g., Blom et al. 2019; Hamann et al. 2020).

Recent research has focused on linguistic domains to disentangle typical language development (TD) from DLD in bilingual children (Marinis and Armon-Lotem 2015; Marinis et al. 2017; Tuller et al. 2018); however, morphosyntactic error patterns, such as the omission of object clitics in French or difficulties with verbal agreement in German, in bilingual children with TD (BiTD) (Paradis 2010; Hamann 2012) can overlap with the error patterns of monolingual children with DLD, leading to diagnostic confounds and over- and under-identification of DLD in bilingual children (Armon-Lotem et al. 2015; Paradis et al. 2022).

DLD as a genuine language impairment manifests in both languages of a bilingual child; hence, it is considered best practice to assess both languages of a bilingual child or at least the dominant language (ASHA 2004; Fredman 2006; RCSLT 2007; IALP 2011). However, the assessment of bilingual children in their heritage language may be problematic in HL-minority settings, as standardized language assessment tools are seldom available. In any case, clinicians able to speak bilingual children’s HL may not always be available (Boerma and Blom 2017; Tuller et al. 2018). The results of bilingual children tested in their heritage language using standardized language assessment tools may not be reliable due to the language–contact phenomena that may result in HL language change (Chilla and Şan 2017) and language attrition (Montrul 2008). For example, Ertanır et al. (2018) and Chilla (2022) used the Türkçe Erken Dil Gelişim Testi (TEDİL) (Topbaş and Güven 2011) and the Türkce Okul Çağı Dil Gelişim Testi (TODİL) (Topbaş and Güven 2017) assessment of Turkish HL abilities and showed that a significant proportion of heritage children performed not only below monolingual norms, but also below dominance-adjusted pathology cut-offs.

In order to avoid misdiagnosis with DLD in BiTD children, focus on the use of complex sentences in naturalistic production (conversation or narratives) may be a key research point, as it has been reported that school-age monolingual children with DLD are weak in this domain in English and other languages (Leonard 2014; Fletcher and Frizelle 2017; Paradis et al. 2022). Given the cross-linguistic vulnerability of complex constructions in DLD and their robustness in bilingual typical language development (BiTD) relative to other language domains, like vocabulary and inflectional morphology (Paradis 2005, 2011, 2016; Chondrogianni and Marinis 2011; Paradis et al. 2017, 2022; Scheidnes and Tuller 2019), they constitute a potential clinical marker for identifying DLD in bilingual contexts.

Sentence repetition tasks (SRTs) incorporating complex constructions have been shown to reliably identify DLD in monolinguals (Conti-Ramsden et al. 2001) and simultaneous and early successive bilinguals with sufficient exposure to the L2 (Armon-Lotem and Meir 2016; Meir et al. 2016; Almeida et al. 2017; Hamann and Abed-Ibrahim 2017; Tuller et al. 2018; Chilla et al. 2021). SRTs have proven sensitive and specific to the morphosyntactic abilities of the child, as repeating sentences includes sentence processing, analysis, and reconstruction thereof (Polišenská et al. 2014; Marinis and Armon-Lotem 2015). As DLD manifests across languages, the Language Impairment Testing in Multilingual Settings (LITMUS)-SR tasks (SRT) are constructed to include cross-linguistically vulnerable complex structures (Marinis and Armon-Lotem 2015); however, Paradis et al. (2022) pointed out that explicitly determining the differentiation potential of multi-clausal sentences may be difficult due to the inclusion of a small number of tokens in existing SRTs. For this reason, in the assessment of bilinguals, more naturalistic but ecologically valid language production tasks could be used as additional support to SRTs (Paradis et al. 2022).

The number of studies on DLD in Turkish-speaking children has increased in recent years (Topbaş 1997, 1999, 2005, 2007; Acarlar et al. 2006; Babur et al. 2007; Uzuntaş 2008; Topbaş and Güven 2008; de Jong et al. 2010; Rothweiler et al. 2010; Topbaş and Yavaş 2010; Acarlar and Johnston 2011; Topbaş et al. 2016; Güven and Leonard 2020; among others). In addition, Turkish, as a heritage language, has been systematically investigated in many studies (Yağmur 1997; Backus and Boeshoten 1998; Türker 2000; Herkenrath and Karakoç 2002; Akıncı and Decool-Mercier 2010; Onar-Valk and Backus 2013; Schroeder 2016; Chilla and Şan 2017; Şan 2018; Schmid and Karayayla 2020; Chilla 2022). A very recent study by Özsoy et al. (2022) focused on background factors, such as age and variation in shifting clause-combining strategies in Heritage Turkish varieties. They found that age and register (formal and informal registers) are the predictors that modulate the nonfinite clause connectors, which are more frequent in Heritage Turkish in Germany than the U.S. In line with previous research (Treffers-Daller et al. 2007; Bayram 2013; Onar-Valk and Backus 2013; Herkenrath 2014; Schroeder 2016; Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020) on subordinate clauses in Heritage Turkish, this paper investigates subordinate clauses in heritage BiTD and BiDLD children, in comparison with late successive bilingual (lL2 BiTD) children and adult heritage bilinguals. We also explore which background factors affect their performance in producing Turkish subordinate clauses in a heritage setting.

2. Subordination in Turkish

2.1. General Properties of the Turkish Language

Turkish, as a highly inflected language, is a morphologically rich agglutinative head-final (left-branching) language, in which each morpheme has a single morphological function (Kornfilt 1997). Unlike fusional languages, each suffix in Turkish encodes individually and can vary in form according to the rules of vowel harmony (Göksel and Kerslake 2005). In Turkish, basic grammatical relations are expressed by inflectional markings on verbs and nouns, leading to what is traditionally described as a flexible word order with prevailing SOV word order. The rich verbal morphology also gives rise to the possibility of leaving the subject unexpressed, often called pro-drop.

2.2. Subordinate Constructions in Standard Turkish and Their Acquisition

Complex constructions are sentences that include multiple clauses: at least one independent clause and either one or more dependent clauses or at least another independent clause. Thus, two types of complex sentence constructions can be distinguished: coordination and subordination. Coordination refers to syntactic constructions in which two or more independent clauses are combined into a larger sentence. Subordination refers to clauses that are dependent on a main clause, the latter called the matrix clause. As such, subordinate constructions are constituents of the matrix clause (arguments, adjuncts, or predicative expressions). In Turkish, noun clauses1, adverbial clauses, and relative clauses constitute the basic subtypes of subordination. Crucially, Turkish has finite and nonfinite subordinate constructions.

2.3. Finite Subordinate Clauses

Finite subordination includes subordinate clauses with finite inflection. Finite noun clauses are either concatenated with the main clause or linked to it using a subordinator, such as ki “that” or diye2,3 (see Appendix A for the list of conventions). As can be expected in a left-branching language, the subordinator diye “saying”, which is a converbial form4 of the verb de- “say”, occurs commonly at the end of nominal or verbal dependent clauses (Göksel and Kerslake 2005) (see (1)), whereas the subordinator ki derives from Persian and is the closest equivalent to the default English complementizer “that” and leads to right-branching subordination (Onar-Valk and Backus 2013), as in (2). In the case of verbs of belief in the main clause, the finite subordinate clause is an object and precedes the main verb following the SOV word order, as shown in (1) and (3).

| (1) | Ben sen bugün | ders | çalıș-acak-sın | diye | düșün-üyor-du-m. | ||

| I you today | lesson | study-FUT-2SG | that | think-PRES.PROG-PAST-1SG | |||

| “I thought that you were going to study today.” | |||||||

| (2) | Ben gör-üyor-um | ki | sen bugün kitap | oku-mu-yor-sun. | |||

| I see-PROG-1SG | that | you today book | read-NEG-PRES.PROG-2SG | ||||

| “I see that you are not reading a book today | |||||||

| (3) | Ahmet | (sen | İtalya’ya | git-ti-n) | san-ıyor. | ||

| Ahmet | you | Italy-DAT | go-PAST-2SG | believe-PRES.PROG | |||

| “Ahmet thinks that you went to Italy.” (Onar-Valk and Backus 2013) | |||||||

Finite adverbial clauses are constructed using subordinating conjunctions, of which diye “saying” and ki “that” have been described for Heritage Turkish. The use of ki in finite adverbial clauses leads to a clause type similar to those used in right-branching Indo-European languages, as seen in (4) (Onar-Valk and Backus 2013). As a subordinator, diye marks adverbial clauses and always stands at the end of the finite adverbial clause in which it is used, as in (5). Finite adverbial clauses in which diye is used as a conjunction express purpose, precaution, or understanding in informal speech (Göksel and Kerslake 2005).

| (4) | Çok | çalıș-mıș | ki | bir | ödül | kazan-mıș. | |

| very | work-PAST-EV/PF | that | a | award | gain-PAST-EV/PF | ||

| “He | worked so hard that he won | an award.” | |||||

| (5) | [Çocukları | getir-ir-ler diye] | porselen | eşyayı | ortadan kaldır-mış-tı. | ||

| children- PL-ACC | bring-AOR-3PL SUB | porcelain | object-ACC | make away-PAST-EV/PF-PAST | |||

| “(Thinking they would bring the children), she had put the china pieces away.” (Göksel and Kerslake 2005, p. 400) | |||||||

Relative clauses are noun phrase modifiers and thus complex adjectival constructions that have two sub-types: finite and nonfinite relative clauses. Finite relative clauses constructed with ki are attested (see (6)) but are rather limited in use (Kornfilt 1997).

| (6) | Öyle | bir | insan-la | tanış-tı-m | ki | onun-la | çok | gül-dü-m |

| such | a | person-INS | meet-PAST-1SG | ki | him-INS | a lot | laugh-PAST-1SG | |

| “I met a person with whom I laughed a lot.” | ||||||||

2.4. Nonfinite Subordinate Clauses

Nonfinite subordinate clauses contain nonfinite verb forms arising through suffixation with a subordinating morpheme. The verb form is suffixed with the subordinator, forming either nominalizations or converbial forms (Göksel and Kerslake 2005). Noun clauses, relative clauses, and adverbial clauses are the main types of nonfinite subordinate clauses in Turkish5.

Nonfinite noun clauses, as noun phrases, function as arguments of the matrix or another subordinate clause (Göksel and Kerslake 2005; Schmid and Karayayla 2020). Various nominalization suffixes are attached to the verbal stems to construct subordinate noun clauses (Kornfilt 1997, p. 45). Based on these nominalization suffixes, they can be divided into four groups: factive nominalization with nonfuture -DIK and future -AcAk,6 action nominalization with -mA, manner nominalization with -(y)Iș, and infinitival clauses with -mAk. We will not explain action manner nominalization here because of its restricted function. Factive nominalization is formed either with -DIK or with -AcAK depending on the tense component to be conveyed (nonfuture vs. future) (Göksel and Kerslake 2005) and form identical argument clauses (Onar-Valk 2015, p. 76), as seen in (7a) and (7b). For both types, the function of a noun clause is either as the subject (7a,b), a direct object with or without an obligatory accusative case marking, or oblique object. Action nominalization using -mA, known as a “short infinitive marker”, forms a subject clause, as seen in (8). Through suffixation with -mA, verbal nouns are lexicalized as ordinary nouns with concrete meanings. It is possible to distinguish between factive and action nominalizations via the semantics of the matrix verbs and with the help of factive or action markers. Lastly, infinitival clauses constructed using -mAK could be considered an alternative to the action nominal, as seen in (9).

| (7a) | (Orhan-ın | bir şey | yap-ma-dığ-ı) | belli-ydi. | ||||||

| Orhan-GEN | anything | do-NEG-FNOM-3SG.POSS | obvious-P.COP | |||||||

| “It was obvious (that Orhan wasn’t doing/hadn’t done anything).” (Göksel and Kerslake 2005, p. 367) | ||||||||||

| (7b) | (Orhan-ın | bir şey | yap-ma-yacağ-ı) | belli-ydi. | ||||||

| Orhan-GEN | anything | do-NEG-FNOM-3SG.POSS | obvious-P.COP | |||||||

| “It was obvious (that Orhan wouldn’t do/wasn’t going to do anything).” (Göksel and Kerslake 2005, p. 367) | ||||||||||

| (8) | (Fatma | Hanım-ın | üç | kat | merdiven | çık-ma-sı) | çok | zor. | ||

| Fatma | miss-GEN | three | storey | stairs | go.up-VN-3SG.POSS | very | difficult | |||

| “It’s very difficult (for Fatma Hanım to go up three flights of stairs).” (Göksel and Kerslake 2005, p. 364) | ||||||||||

| (9) | Ev-e | git-mek | ist-iyor-um. | |||||||

| Home-DAT | go-INF | want-PRES.PROG-1SG | ||||||||

| “I want to go home.” | ||||||||||

Turkish nonfinite adverbial clauses correspond to adverbial clauses in Indo-European languages. While lexical elements are used to construct adverbial clauses in Indo-European languages, nonfinite adverbial clauses in left-branching Turkish are headed by converbial suffixes as the right most morpheme in the subordinate construction, which attach to the dependent verb, making it non-finite. The subordinating suffixes have semantic nuances relating to manner, time, result, purpose, place, cause, condition, degree, and concession, i.e., the same kind of modification as expressed in adverbial clauses in Indo-European. In order to understand how nonfinite adverbial clauses in Turkish are constructed, we illustrate the working of converbial suffixes in adverbials giving just a few examples. For further details, see (Kornfilt 1997; Göksel and Kerslake 2005). Example (10) below presents the converbial marker -mAk için “in order to”. The formal counterpart of -mAk için is -mAk üzere and is used where the subject of a nonfinite clause expressing purpose is the same as that of the superordinate clause. The converb used in (11) includes suffixes, which are a combination of the factive nominalization marker -DIK with a possessive and locative case marker with the meaning “at the time of” (Demir 2015). The converbial suffixes -(y)ArAk, -(y)IncA, and -(y)ken, which often correspond to the manner of an action or to “when”, “while”, “because”, “as soon as”, “before”, or “after”, are attached directly to the subordinate verb (see (12)), and constitute a subclass of adverbial sentences with converbs.

| (10) | Aile-m-i | gör-mek için | Balıkesir’e | gid-iyor-um. | (purpose) | ||

| family-1SG. POSS-ACC | see-CV | Balıkesir-DAT | go-PRES.PROG-1SG | ||||

| “I am going to Balıkesir in order to see my family.” | |||||||

| (11) | Akşam | ev-e | gel-diğ-im-de | Selin | uyu-yor-du. | (time) | |

| evening | home-DAT | come-FNOM-1SG. POSS-LOC | Selin | sleep-IMPF-P.COP-PAST | |||

| “When I came home in the evening, Selin was sleeping.” | |||||||

| (12) | Ayşe | merdiven-ler-i | (koş-arak) | çık-tı. | (manner) | ||

| Ayşe | stair-PL-ACC | run-CV | go up-PAST | ||||

| “Ayşe went upstairs running (i.e., ran up the stairs).” (Schmid and Karayayla 2020, p. 60) | |||||||

Finally, Turkish nonfinite relative clauses are prenominal clauses that do not require a relative pronoun and are marked morphologically with a subject or object participle (Uzundağ and Küntay 2019, p. 1145). They constitute the most prevalent relative clause type in Turkish and may occur as a restrictive or nonrestrictive relative clause, which, according to Kornfilt (1997, p. 61), cannot be clearly distinguished. They contain one of the participial suffixes and factive nominalizers -DIK or -–(y)AcAK. While -(y)An is used for the subject relative, as in (13), -DIK and -(y)AcAK are used for the direct object (14,15), indirect object, and oblique relatives (16) (in O(S)V order). These suffixes correspond to the English relative pronouns “who”, “which”, “that”, “whom”, “whose”, and “where” (Onar-Valk 2015, p. 77). In non-subject relatives, the subject of the relative clause is marked with the genitive suffix, and -DIK is followed by a possessive suffix that marks agreement with the subject, as seen in (18). The examples of the five relativization strategies (see (13) to (22)) are taken from the following sources: Aksu-Koç 1994; Altan 2005; Göksel and Kerslake 2005; Ilgaz et al. 2021.

Subject relativization with -(y)An as a subject relative:

| (13) | (Şu | konuş-an | kadın) | sen-i | sev-iyor. |

| that | talk-SUBP | woman | you-ACC | love-PRES.PROG | |

| “That woman who is talking likes you.” | |||||

Direct object relativization with –DIK/–(y)AcAk as an object relative:

| (14) | (Dün | seyret-tiğ-im | oyun-)u | beğen-di-m. |

| yesterday | watch-OBJP-1SG | play-ACC | like-PAST-1SG | |

| “I liked the play I watched yesterday.” | ||||

Direct object relativization with -(y)AcAk as an object relative:

| (15) | (Yarın | buluș-acağ-ım | öğretmen-im-)i | çok | sev-er-im. |

| tomorrow | meet-OBJP-1SG | teacher-1SG.POSS-ACC | very | love-AOR-1SG | |

| “I really like my teacher, whom I will meet tomorrow.” | |||||

Oblique object relative clause with -DIK, -(y)AcAk:

| (16) | (Ahmet’in | duvar-ı | boya-yacağ-ı | fırça-yı) | Ercan | al-mıș. |

| Ahmet-GEN | wall-ACC paint-OBJP-3SG.POSS | brush-ACC | Ercan | take-EV/PF-PAST | ||

| “Ercan took the brush with which Ahmet would paint the wall.” | ||||||

Adverbial relative clause with -(y)An, -DIK, -(y)AcAk:

| (17) | İç-in-den | nehir | ak-an | șehr-i | sev-di-m | ||||||||||

| in-3SG.POSS-ABL | river | flow-PART | town-ACC | love-PAST-1SG | |||||||||||

| “I loved the town through which a river flows.” | |||||||||||||||

| (18) | Üstünde kitap-lar-ın | dur-duğ-u | raf-ı | dün | ev-e | getir-di-m | |||||||||

| on | book-PL-GEN | stand-PART-3SG. POSS | shelf-ACC | yesterday | home-DAT | bring-PAST-1SG | |||||||||

| “I brought home the shelf on which the books are standing yesterday.” | |||||||||||||||

| (19) | Okula | birlikte | gid-eceğ-im | arkadaș-ım | çok | akıllı. | |||||||||

| school-DAT together | go-OBJP-1SG.POSS | friend-1SG.POSS | very | clever. | |||||||||||

| “My friend, with whom I will go to school, is very clever.” | |||||||||||||||

Possessor and possessed constituent relativization: subject clauses with -(y)An and non-subject clauses with -(y)AcAK and -DIK:

| (20) | Baba-sı | asker | olan | arkadaș-ım | bugün | Biz-e | gel-ecek. | ||||||||

| father-3SG.POSS | soldier | be-SUBP | friend-1SG.POSS | today | we-DAT | come-FUTURE | |||||||||

| “My friend, whose father is a soldier, is coming to us today.” | |||||||||||||||

| (21) | Şoför-ün | cam-ı-nı | sil-eceğ-i | otobüs | kaza | yap-tı. | |||||||||

| driver-GEN | window-3SG.POSS-ACC | wipe-PART-3SG.POSS | bus | accident | crash-PAST | ||||||||||

| “The bus of which the driver is/was going to wipe the window had a crash.” | |||||||||||||||

| (22) | Bisiklet-i-ni | ödünç al-dığı-m | arkadaș-ım-ı | özle-di-m | |||||||||||

| bicycle–3SG.POSS-ACC | borrow–OBJP-1SG.POSS | friend-1SG.POSS-ACC | miss-PAST-1SG | ||||||||||||

| “I missed my friend whose bicycle I borrowed on street a few days ago.” | |||||||||||||||

2.5. Acquisition of Subordinate Clauses in Standard Turkish

As to the acquisition of noun clauses in standard Turkish, previous studies (Aksu-Koç 1994; Altan 2005; Ilgaz et al. 2021) have suggested that, among all noun clause types, nominal constructions with -mAK are the most frequent construction in early child language, and first occur with the matrix predicate iste- “want” and çalış- “try” in 3-year-old children’s speech. The second most frequent nominalizer used in noun clauses is the -DIK participle, followed by the -mA verbal suffix and -(y)AcAk (Aksu-Koç 1994; Altan 2005; Ilgaz et al. 2021).

With respect to the acquisition of adverbial clauses in Standard Turkish, the existing research has found that converbial suffixes such as -(y)IncA, -(y)ken, and -(y)Ip are acquired earlier than others by monolingual Turkish-speaking children (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). However, children acquire the morphologically simple converbial suffix -(y)ArAK and the complex morphemes -DIĞI için and -mAK için after ages 5–7 years (Aksu-Koç 1994; Küntay and Slobin 1999).

Monolingual Turkish-speaking children have been reported to acquire relative clauses after the age of 5 years (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). Relative clauses constructed using a possessive relativizer appear in the utterances of these children in a more limited manner and later than other types of relative clauses (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). Previous studies have shown that monolingual Turkish children who are younger than nine years old avoid the use of relative structures altogether and commit formal errors in a Standard Turkish context (see, e.g., Aksu-Koç and Slobin 1985; Küntay and Slobin 1999; Aksu-Koç 2010; Özge et al. 2010).

2.6. Subordination in Heritage Turkish

Heritage Turkish is the minority language with the highest number of speakers in Germany and whose speakers constitute heterogeneous groups with different language dominance (Daller and Treffers-Daller 2014). One of the most researched Heritage Turkish phenomena in recent years is subordinate clauses (Herkenrath and Karakoç 2002; Treffers-Daller et al. 2007; Şimşek and Schroeder 2011; Yılmaz 2011; Onar-Valk and Backus 2013; Herkenrath 2014; Rehbein and Herkenrath 2015; Schroeder 2016; Chilla and Şan 2017; Akkuş et al. 2017; Turan et al. 2020, among others); however, the number of studies focusing on subordination in adults is very limited (see Yağmur 1997; Yağmur et al. 1999; Treffers-Daller et al. 2007; Yılmaz 2011; Iefremenko and Schroeder 2019). The studies of Treffers-Daller et al. (2007) and Onar-Valk (2015) investigated all types of subordinate clauses in Heritage Turkish adults, whereas Iefremenko and Schroeder (2019) and Turan et al. (2020) studied converbial (adverbial) clauses.

In their study, Treffers-Daller et al. (2007) focused on the different types of subordination. They compared the data of three groups of Turkish adolescent and adult heritage bilinguals and a monolingual control group 16–20 years of age. The bilingual groups were divided into three: the A group was born and raised in Germany; the B group, living in Turkey for around 7 years, was born and raised in Germany; and the C group were “recent returnees” (Treffers-Daller et al. 2007) at the time of the study. The groups were expected to describe a story presented in two comic strip series. The results show that the groups that had most contact with Standard Turkish could produce subordinated constructions better than the groups that had less. Although the use of nonfinite nouns and relative clauses in all the groups was low, adverbial clauses were used by all the groups frequently (Treffers-Daller et al. 2007).

The cumulative PhD project of Onar-Valk (2015) broadly and systematically investigated the change in the subordination strategies in Heritage Turkish in terms of finiteness and word order in subordinate clauses. The studies included spontaneous and elicited speech of bilingual adults aged 18–35 years who were born and grew up in the Netherlands in comparison with a monolingual control group living in Turkey. These groups participated in various elicitation experiments in monolingual (Turkish) and bilingual (Turkish–Dutch) modes. The results demonstrate that although heritage bilingual adults used nonfinite subordinate clauses similarly to the monolinguals in monolingual mode, they used finite subordinate clauses more than nonfinite ones in the bilingual mode. This study concludes that the use of juxtaposition and less use of conjunctions in Heritage Turkish may have resulted from the contact-induced change in the heritage setting (Onar-Valk 2015).

In a pilot study, Iefremenko and Schroeder (2019) examined clause combining strategies in formal and informal written and spoken Turkish in monolingual and heritage settings within the German and U.S. contexts. The main aim of this study was to investigate whether Heritage speakers of Turkish overused constructions typically used in spoken Turkish in their written production. For this purpose, they compared spoken and written language samples of four 16–18-year-old monolingual Turkish speakers to that of six age-matched heritage speakers of Turkish in Germany and the U.S. To elicit formal spoken and written language samples, the participants were requested to report an imaginary accident they witnessed to a police officer orally and submit a written report to the police station. To elicit informal spoken and written samples, the participants were requested to tell a friend about the accident via a phone call (informal spoken) or a text message (informal written). As to formal written language, a crucial difference was observed between the monolingual and heritage speakers with respect to the rate of subordinate constructions. While the monolinguals mainly produced nonfinite subordinate clauses, such as relative and adverbial clauses, the heritage speakers predominantly opted for structurally simpler structures, namely juxtaposed and coordinated constructions rather than subordinate ones (Iefremenko and Schroeder 2019, p. 249). Moreover, the formal written language samples of the heritage speakers resembled the formal spoken language samples of the monolinguals in that nonfinite subordinate clauses were used to a lesser extent and whenever nonfinite subordinate constructions were produced, they were adverbial clauses constructed with the suffixes -(y)Ip and -(y)ken. With respect to formal spoken language, the heritage speakers opted for the same strategies observed in their formal written language samples, namely, producing paratactic constructions by combining clauses using coordinated conjunctions, such as ve “and”, ardından “after”, and ama “but”, and postpositions, such as ondan sonra” (and) then/after that. The monolingual speakers, on the other hand, tended to use finite subordinate clauses. Interestingly, aside from using paratactic constructions in place of nonfinite subordinate clauses, U.S. heritage speakers produced finite subordinate clauses primarily constructed using the quotative particle diye “saying” (Iefremenko and Schroeder 2019, p. 251). With respect to informal language (spoken and written samples combined), the heritage speakers resembled their monolingual counterparts in that they mainly produced coordinated constructions rather than subordinated ones with a rate of 75% for coordinated ones (Iefremenko and Schroeder 2019, p. 252). An interesting pattern was observed for the heritage speakers in Germany, namely the substitution of dative case marking in nonfinite noun clauses by accusative case marking and vice versa. In the informal language samples of the U.S. heritage speakers, a significant proportion of the produced subordinate clauses were nonfinite clauses, similar to their formal spoken language samples, especially those constructed with the quotative particle diye. Iefremenko and Schroeder (2019) concluded that Heritage Turkish varieties in Germany and the U.S. generally make less use of nonfinite subordinate clauses in formal Turkish compared to the Standard Turkish variety. The authors ascribe this to the potential influence of the HS’ dominant languages of English and German on Turkish in heritage settings. The authors state that it can be assumed that nonfinite subordinated structures are not fully acquired in heritage settings, as they constitute Standard Turkish phenomena and are less available in heritage language input (Iefremenko and Schroeder 2019, p. 253). It can be also said that from the 1950s until today, Heritage Turkish varieties in Germany and the U.S. may have changed due to their own dynamics (Iefremenko and Schroeder 2019, p. 254). According to the results of this pilot study, Heritage Turkish in the U.S. diverged more from Standard Turkish than Heritage Turkish in Germany (Iefremenko and Schroeder 2019, p. 254), e.g., U.S. heritage speakers of Turkish showed higher rates of finite subordinated clauses in comparison to heritage speakers of Turkish in Germany. The observed differences are likely to be tied to language policies in the U.S., e.g., a lack of formal instruction in Standard Turkish, the dominance and omnipresence of English in everyday life, and a paucity of Turkish-speaking communities paired with the much larger geographical distance to the homeland of Turkey.

Additionally, the results of a recent study (Turan et al. 2020) support the view that adult heritage bilinguals use fewer nonfinite structures and more “paratactic clause-combining strategies” (Iefremenko et al. 2021). The study by Turan et al. (2020) focused on the converbs -(y)Ip and -(y)IncA in the narratives of 18–20-year-old adult heritage bilinguals, in comparison with their monolingual peers. The results suggest that the use of converbs by adult heritage bilinguals was significantly lower than in their monolingual control group. According to the qualitative results, converbs were used in several cases ungrammatically and unconventionally, as seen in Example (23), in which the converb -(y)Ip would require the same subject and object in the main and subordinate clauses (Turan et al. 2020).

| (23) | Standard Turkish | ||||||||

| Çocuk-un | ağaç-lar-a | bak-tığ-ı sırada | kuş | çık-mış | ora-dan | ||||

| child-GEN-3SG | tree-PL-DAT | look-CV-3SG.POSS time | bird | leave-EV/PF | there-ABL | ||||

| “At the time when the child looked at the trees, a bird flew out.” (Turan et al. 2020, p. 8) | |||||||||

| Utterance produced by adult HS | |||||||||

| O sıra | çocuk | ağaç-lar-a | bak-ıp | kuş | çık-mış | ora-dan | |||

| meanwhile | child | tree-PL-DAT | look-CV | bird | leave-EV/PF | there-ABL | |||

| “That time the child looked at the trees and a bird flew out.” | |||||||||

Several acquisitional studies (Aarts 1998; Backus 2004; Herkenrath and Karakoç 2002; Pfaff 1991, 1994) have shown that child heritage bilinguals lag behind monolingual children after the onset of school regarding subordinating morphology (e.g., participials, nominalizations, and converbial constructions) (Herkenrath 2014). The lack of institutional encouragement with respect to literacy skills and text habitualization have been observed as reasons why child heritage bilinguals are not as good at acquiring subordinating constructions as monolingual children (Herkenrath 2014). However, Akıncı et al. (2006) showed in their studies on older children that Turkish-speaking child heritage bilinguals in France may have similar performance in subordinations during their later school years, subject to the encouragement of biliteracy activities in the migrant setting determined by the educational system. The discrepancy between them and monolingual Turkish-speaking children in including subordinates results from the change in Turkish acquired in a heritage context, resulting from the cultural and linguistic differences between Standard Turkish (written) and its varieties (spoken) (Treffers-Daller et al. 2007; Chilla 2022).

Different types of noun clauses produced by child heritage bilinguals have not been systematically described in the existing literature (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). As described in Section 2.1, the subordinators -DIK, -mA, -(y)AcAK, and -(y)Iş are the most prominent ones used to construct noun clauses. In her study, Herkenrath (2014) examined the different morphological forms of -DIK that occur in different syntactical functions, such as “noun clauses, complex converbs, non-subject attributive clauses, nominal actor clauses”. The entire corpora of two research projects including the development of complex language (ENDFAS and SKOBI projects; Rehbein 2009; Herkenrath and Rehbein 2012) were used in this study (Herkenrath 2014). The two corpora included longitudinal data of narratives elicited in a family setting from thirty-six bilingual children, twenty monolingual Turkish children, and five monolingual German children, covering an age range from 4 to 14, as well as from the adults present during the conversations (Herkenrath 2014). The results suggest that the competence of heritage children was similar to that of monolingual children. A contact-induced change was observed, however, in the use of factive nominalization with -DIK marked for possessive and accusative, which forms a noun clause roughly equivalent to a German dass “that” construction (Herkenrath 2014). The functional potential of -DIK is used by bilingual Turkish children in a limited way.

Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020) investigated subordinate clauses in the data of 102 heritage children living in Sweden aged 4–7 years and found that their participants produced different types of nonfinite subordinate constructions. As for noun clauses, the heritage children produced 300 nonfinite constructions in which the subject is coreferential with the subject of a matrix clause (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020), and only 16 nonfinite noun clauses, whose subjects were not coreferential with the matrix subject (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). Even though those noun clauses were similar to the ones produced in adult Standard Turkish, regarding the subjunctor choice, oblique subject case marking, and possessive suffix, there were some cases in which the children did not mark the subject in the genitive case (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). Nonfinite noun clauses containing the quotative particle diye “saying” and “complement-like finite structures” (terminology adopted from Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020, p. 175)) were included in the data for combination of the past tense marker -DI with diye, and of the future marker -(y) AcAK with diye, as seen in Example (24) (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). According to Herkenrath and Karakoç (2007), noun clauses containing the quotative particle diye are often constructed with the subordinate clause following the main clause, which resembles such structures in right-branching languages like German.

| (24) | Expected in Standard Turkish | |||||||||

| Sonra | anne | kuş da | yavru | kuş-ları | yi-yecek | diye | kork-tu. | |||

| then | mother | bird too | baby | bird-PL-ACC | EAT-FUT | saying | get afraid-PAST-3SG | |||

| “Then, the mother bird got afraid that it will eat baby birds.” | ||||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | ||||||||||

| Sonra | anne | kuş da | kork-tu | bunlar-ı | yi-yecek | diye | yavru kuş-lar-ı | |||

| then | mother | bird too | get afraid-PAST-3SG | these-ACC | EAT-FUT | saying | baby | bird-PL-ACC | ||

| “Then, the mother bird got afraid that it will eat them, the baby birds.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 175) | ||||||||||

That Heritage Turkish includes right-branching complement-like finite structures based on finite verb forms has been discussed in various studies (Treffers-Daller et al. 2007; Onar-Valk 2015; Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). These finite clauses are linked to the matrix clause with ki, which stands at the beginning of its clause, as in right-branching Indo-European subordination (Göksel and Kerslake 2005; Herkenrath and Karakoç 2007; Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020) (also see footnote 2). Verbs of utterance (e.g., de- “to say”), perception (e.g., duy- “to hear”, gör- “to see”), and cognition (e.g., bil- “to know”, zannet- “to think”) occur as matrix verbs, as seen in (25). In the absence of the junctor ki, Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020, p. 175) observed that the main clause, including verba dicendi, is followed by a “syntactically non-embedded complement clause which has a nominative subject and a finite predicate”, as seen in (26).

| (25) | Standard Turkish | |||||||||||

| Anne-si | kedi-nin | yine | gel-diği-ni | gör-dü | ||||||||

| mother-3SG.POSS | cat-GEN | again | come-FNOM-ACC | see-PAST | ||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | ||||||||||||

| Anne-si | gör-dü | ki | kedi | gene | gel-iyo(r) | |||||||

| mother-3SG.POSS | see-PAST-3SG | that | cat | again | come-PRES.PROG | |||||||

| “Its mother saw that cat was coming again.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 176) | ||||||||||||

| (26) | Standard Turkish | |||||||||||

| Anne-ye | diyor | ki: | “Ben | yemek | ist-iyor-um”. | |||||||

| mother-DAT | say-PRES.PROG | that | I | food | want-PRES.PROG-1SG | |||||||

| “He says to the mother (that): I want to have food.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 176) | ||||||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | ||||||||||||

| Anne-ye | diyor | ben | yemek | ist-iyor-um | ||||||||

| mother-DAT | say-PRES.PROG | I | food | want-PRES.PROG-1SG | ||||||||

| “He says to the mother: I want to have food.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 176) | ||||||||||||

Adverbial clauses headed by converbs are among the main nonfinite subordination strategies in Turkish. According to previous studies conducted in different European heritage settings (Backus 2004; Onar-Valk 2015; Schroeder 2016), child heritage bilinguals, in comparison with their monolingual peers, use fewer subordinated structures and more paratactic structures; however, this generalization may not be valid when considering subordinated structures including converbs, as the results of previous studies (see, e.g., Treffers-Daller et al. 2007; Rehbein and Herkenrath 2015; Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020; Turan et al. 2020) differed in terms of the vulnerability of the converb forms, regarding qualitative and quantitative change, in the heritage setting (Iefremenko et al. 2021). Although it is reported that subordinated structures with converbs are robust against language contact change in Germany and Sweden, there are also individual differences resulting from background factors, such as social factors or language use within the family (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020).

Rehbein and Herkenrath (2015) studied converbial clauses in Turkish in monolingual and heritage settings with respect to contact-induced language change. The spoken Turkish data from monolingual and bilingual children aged 4–9 are from the corpora of ENDFAS-SKOBI projects (Rehbein 2009; Herkenrath and Rehbein 2012). The converbs -(y)ken, -(y)IncA, and -(y)Ip were frequently used by 4-year-old heritage children. Furthermore, the frequency of the converb suffix –(y)IncA increased in the production of child heritage bilinguals between 4 and 9 years. The converb suffix –(y)ken was produced frequently by child heritage bilinguals at the ages of 8 and 9. The results indicate that converbs appear robust against contact-induced language change (Rehbein and Herkenrath 2015). Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020) observed that Turkish heritage children in Sweden produced adverbial clauses more than twice as often in responses to comprehension questions than in their narrative production. Heritage children aged 4 already used the converbs -mAk için “in order to” and -DIĞI için “since/because”, and the converbs most frequently used were -(y)ken “while, when”, -(y)IncA “when/since”, and -(y)Ip “and (then)”, which are temporal converbial markers (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). One of the striking results of the study is the use of an extended version of the converbial marker -(y)ken” while, when” by a vowel e, as in -(y)kene, which is a nonstandard dialectal variant used extensively in Anatolian and Rumelian dialects (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). Although adverbial clauses are constructed by attaching -(y)ken (or -(y)kene) to the participial forms of verbs, as in the future participles -(y)AcAk and -(y)ken, ungrammatical formation was found in the data, such as *-DIyken (past marker -DI + -(y) ken), as seen in Example (27) from Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020).

| (27) | Standard Turkish | ||||||||

| Sonra | o | top-u | al-ır-ken | kedi | o-nun | balık-lar-ın-ı | bitir-di. | ||

| then | he | ball-ACC | take-PAST-CV | cat | he-GEN | fish-PL-3SG.POSS.ACC | finish-PAST | ||

| Utterance produced by child HS | |||||||||

| Sonra | top-u | al-dıy-ken, | kedi | kedi | işte | balık-lar-ın-ı | bitir-di. | ||

| then | ball-ACC | take-PAST-CV | cat | cat | well | fish-PL-3SG.POSS-ACC | finish-PAST | ||

| “Then, while he was taking the ball, the cat finished his fish.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 188) (Same for Standard Turkish) | |||||||||

Previous studies (Schaufeli 1991; Rehbein and Karakoç 2004; Karakoç 2007; Herkenrath 2016) have also reported the overuse of temporal deictic expressions by Turkish–Dutch and Turkish–German child heritage bilinguals. Similarly, Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020) found that child heritage bilinguals use paratactic sentences containing finite verbs in combination with temporal deictic adverbs, such as ondan sonra “(and) then/after that”, referring to posteriority, or o zaman “that time”, expressing simultaneity. The example below (28) shows that a six-year-old Heritage Turkish-speaking child in Sweden used a finite form of the past tense suffix -DI followed by a sentence with the initial word o zaman “that time” instead of using the converbial form -(y)IncA, where the combination of gördü o zaman da “he saw and that time” may mean görünce “when he saw”, as seen in Example (28).

| (28) | Standard Turkish | ||||||||||||||||

| O-nu | al-acağ-ı | zaman, | o-nu | gör-dü | ve | ye-di | |||||||||||

| it-ACC | take-CV-3SG.POSS | time | it-ACC | see-PAST | and | eat-PAST | |||||||||||

| “When he was going to take it, he saw it and ate it.” | |||||||||||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | |||||||||||||||||

| O | zaman | onu | al-acak-tı, | sonra | o-nu | gör-dü | o zaman da | onu | yedi. | ||||||||

| that | time | it-ACC | take-FUT-P.COP | then | it-ACC | see-PAST | that time | it-ACC | eat-PAST | ||||||||

| “That time he was going to take it, he saw it and that time he ate it.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 181) | |||||||||||||||||

Two more observations by Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020) are also important for our data: (a) the converbial marker -DIĞI için, which is a composite consisting of a multi-functional suffix added directly to the verb followed by a possessive suffix agreeing with the subject of the subordinate clause and/or postposition, was already used frequently at age 4; and (b) child heritage bilinguals combine the clause–final -DIĞI için “because” with clause–initial conjunctor çünkü “because” by marking causality twice, which is a nonstandard use in Turkish, as seen in Example (29). In the same vein, some causal sentences with diye (otherwise used correctly) included the free junctor çünkü, which is not a standard use, as seen in Example (30), which is an answer to a comprehension question from the MAIN (Gagarina et al. 2012; Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020).

| (29) | Standard Turkish | |||||||||

| balon-u-nu | al-dığ-ı | için. | ||||||||

| balloon-3SG.POSS-ACC | take-CV-3SG.POSS | for | ||||||||

| “Because he took his balloon.” | ||||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | ||||||||||

| çünkü | balon-u-nu | al-dığ-I | için | |||||||

| then | balloon-3SG.POSS-ACC | take-CV-3SG.POSS | for | |||||||

| “Then, while he was taking the ball, the cat finished his fish.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 188) | ||||||||||

| (30) | Question: | |||||||||

| Sence çocuk neden iyi/ güzel/ mutlu/ memnun hissediyor? | ||||||||||

| “Why do you think that the boy is feeling good?” | ||||||||||

| Possible answer in Standard Turkish | ||||||||||

| Çocuk | balon-un-u | al-abil-diğ-i | için | mutlu | hissediyor. | |||||

| child | balloon-3SG.POSS-ACC | take-PSB-CV-3SG.POSS | for | happy | feel-PRES.PROG | |||||

| “The child feels good because he was able to get his balloon.” | ||||||||||

| Child HS response | ||||||||||

| Çünkü | balon-un-u | al-abil-di | diye. | |||||||

| because | balloon-3SG.POSS-ACC | take-PSB-PAST | saying. | |||||||

| “Because he could take his balloon.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 183) | ||||||||||

Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020) noted the mixing of causal and purposive structures, which does not correspond to Standard Turkish. They present a small number of relevant examples, which may overlap with Heritage Turkish in Germany and/or the characteristics of DLD in Turkish. The complex form -mAK için or, similarly, -mAsI için, used in Standard Turkish for purposive clauses, was used in heritage children’s answers to a comprehension question with a causal function, as seen in Example (31). Complex forms, such as -mAsIn diye and -mAsI için, in purpose clauses involving subject differences were constructed by heritage children as purpose clauses with subject coreference (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020), as in Example (32). Forms including diye “saying” were produced by heritage children with omissions of the possessive marker after the future marker -(y)AcAk as nonstandard forms, as seen in Example (33).

| (31) | Question | ||||||||||||||

| Sence Köpek_ kendini neden iyi/ güzel/ mutlu/ memnun vs. hissediyor? | |||||||||||||||

| “Why do you think that the boy is feeling good?” | |||||||||||||||

| Possible response in Standard Turkish | |||||||||||||||

| Kedi-yi | kovala-dığ-ı | için | o | da | acık-mış. | ||||||||||

| cat-ACC | chase-CV-3SG.POSS | for | it | too | get hungry-EV/PF | ||||||||||

| “It also got hungry because it chased the cat.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 189) | |||||||||||||||

| Child HS response | |||||||||||||||

| Çünkü | o | da | acık-mış | kedi-yi | kovala-mak | için | |||||||||

| because | it | too | get hungry-EV/PF | cat-ACC | chase-CV | for | |||||||||

| “Because it also got hungry to chase the cat for.” | |||||||||||||||

| (32) | Question: | ||||||||||||||

| Çoçuk | neden | yukarıya | doğru | uzanıyor? | |||||||||||

| “Why | does | the boy | jump | up?” | |||||||||||

| Standard Turkish | |||||||||||||||

| Balon-un-u | al-mak için | ||||||||||||||

| baloon-3SG.POSS-ACC | take-CV | ||||||||||||||

| “In order to take his balloon.” | |||||||||||||||

| Child HS response: | |||||||||||||||

| çünkü | balon-un-u | al-ma-sı | için. | ||||||||||||

| because | balloon-3SG.POSS-ACC | take-CV-3SG.POSS | for | ||||||||||||

| “Because, in order to take his balloon.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 190) | |||||||||||||||

| (33) | Standard Turkish | ||||||||||||||

| Kedi | de | onlar-ı | korkut-acağ-ım | diye | gel-iyor. | ||||||||||

| cat | too | they-ACC | scare-FUT-GEN.1SG | saying | come-PRES.PROG | ||||||||||

| “The cat is coming to scare them.” | |||||||||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | |||||||||||||||

| Kedi | de | gel-iyo(r) & | ehm onlar-ı & | äehm korkut-acak | diye | ||||||||||

| cat | too | come-PRES.PROG | they-ACC | scare-FUT | saying | ||||||||||

| “The cat also comes, ehm, in order to scare them.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 191) | |||||||||||||||

The acquisition of relative clauses in Heritage Turkish has been the subject of several studies in different European countries, such as the Netherlands (Aarssen 1996), the U.K. (Bayraktaroğlu 1999), Germany (Treffers-Daller et al. 2007; Bayram 2013; Boeshoten 1990; Pfaff 1991, 1994), and France (Akıncı et al. 2001). The results of these studies suggest that heritage children show a tendency towards the use of simple declarative sentences, not complex relative clauses (Backus 2004). In his study, Bayram (2013) investigated the development of the linguistic system of child and adolescent heritage bilinguals aged 7–16 in terms of various morphosyntactic phenomena, including relative clauses. Bayram (2013) collected data from 24 child heritage bilinguals aged 10–15 years living in Germany, in comparison to monolingual children aged 7–10 years. The groups completed communicative oral tasks. With respect to relative clauses, the majority of child heritage bilinguals used individual clauses instead of constructing relatives through a subordination procedure. In Example (34), child heritage bilinguals used a paratactic construction, instead of the factive nominalizer -DIK, with which possessor and possessed constituent relativization is carried out (Bayram 2013).

| (34) | Standard Turkish | ||||||||||

| Sen-in | resm-in-de | köpeğ-in | ısır-dığ-ı | tavşan | var | mı? | |||||

| you-GEN | picture-2SG.POSS-LOC | dog-GEN | bite-OBJP-3SG.POSS | rabbit | exist | INT | |||||

| “In your picture, is there a rabbit which is bitten by a dog?” | |||||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | |||||||||||

| Sen-in | resim-de | bir | tavsan | var mı? | Köpek | tavşan-ı | ısır-ıyor. | ||||

| you-GEN | picture-LOC | one | rabbit | exist INT | dog | rabbit-ACC | bite-PRES.PROG | ||||

| “In your picture, is there a rabbit? The dog is biting the rabbit.” (Bayram 2013, p. 148) | |||||||||||

Additionally, Bayram (2013) found that heritage children differed significantly from their peers in the production of relative clauses with respect to word order. As example (35) shows, the child heritage bilinguals had not mastered obligatory subject–verb inversion yet: the relative clause kadını seven “who loves the woman”, used as the subject relative should precede the noun phrase bir adam “a man”, as in the Standard Turkish sentence (Bayram 2013).

| (35) | Standard Turkish | |||||||

| Senin | resmi-n-de | kadın-ı | sev-en | bir | adam | var | mı ? | |

| your | picture-2SG.POSS-LOC | woman-ACC | love-OBJP | a | man | exist INT | ||

| “In your picture, is there a man who loves the woman?” | ||||||||

| Child HS response | ||||||||

| Evet. | Senin | resim-de | bir | adam | kadın-ı | sev-en | var mı? | |

| yes | your | picture-LOC | a | man | woman-ACC | love-PART | existent INT | |

| “Yes. In your picture, is there a man the woman who loves?” (Bayram 2013, p. 150) | ||||||||

Similar results emerge in Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020): heritage children in Sweden produced mostly juxtaposed finite clauses instead of constructing relative clauses, as seen in (36), an error type which has also been described for monolingual Turkish-speaking children (Özge et al. 2010); however, the performance of heritage children showed no correlation with increasing age (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020). Coşkun-Kunduz and Montrul (2022) corroborated these findings in their study on the comprehension and production of relative clauses by child heritage bilinguals in Turkish and English. For Turkish, a picture–sentence matching task and SRT were completed by 32 heritage children aged 6–15 and 48 monolingual children aged 3–15. The heritage children showed better performance in comprehension than production, preferring replacement of complex relative clauses with juxtaposition, as well as a subject–relative-clause advantage in comprehension (Coşkun-Kunduz and Montrul 2022). These authors suggest that relative clauses do not develop fully in heritage children in the U.S.

| (36) | Standard Turkish | |||||||||

| Orada | kelebek | yakala-ma-ya | çalış-an | bir kedi | gör-üyor-um | |||||

| there | butterfly | catch-FNOM-DAT | try-OBJP | a cat | see-PRES.PROG-1SG | |||||

| “There I see a cat which tries to catch a butterfly.” | ||||||||||

| Utterance produced by child HS | ||||||||||

| Orada | bir | kedi | gör-üyor-um | kelebeğ-i | yakala-ma-ya | çalış-ıyor. | ||||

| there | one | cat | see-PRES.PROG-1SG | butterfly-ACC | catch-FNOM-DAT | try-PRES.PROG | ||||

| “There I see a cat; it is trying to catch butterfly.” (Bohnacker and Karakoç 2020, p. 166) | ||||||||||

2.7. Subordination in DLD in Turkish

According to a significant number of studies on DLD in Turkish, difficulties with counterfactuals, tense, and negation in verb morphology and case marking in nominal morphology have been observed in children with DLD (Babur et al. 2007; Acarlar and Johnston 2011; Yarbay-Duman et al. 2015; Topbaş et al. 2016; Yarbay-Duman and Topbaş 2016; Chilla and Şan 2017; Şan 2018; Chilla 2022). Derivational morphology has also been shown to pose problems for children with DLD in SRT (Topbaş 2010). Compared to typically developing age-matched groups, particular morphological and morphosyntactic errors are reported for Turkish DLD children, such as the omission of bound morphemes, production of fewer morphemes, and difficulties with subordinate clauses (Topbaş et al. 2016).

In their study, Güven et al. (2009) compared the data of three children (mean age 5;7) with DLD to three age-matched TD children from the T-SALT Database (mean MLU = 4.23) and examined spontaneous speech in conversational and narrative samples of these children. Their most outstanding result was that children with DLD produced fewer subordinate clauses than children with TD. In another study, Topbaş et al. (2016) compared the data of three children with DLD (mean age 5;2) with three age-matched TD children from the T-SALT Database. The aim of the study was to identify several morphological difficulties and errors based on spontaneous speech samples of children with DLD in order to ameliorate the assessment of DLD. TEDİL (Topbaş and Güven 2011) was used for DLD identification in children. Picture descriptions and the narrative tasks from the same test were applied to collect the speech samples. The results show that, in addition to the morphological errors in noun and verb morphology, children with DLD overwhelmingly used simple sentences, whereas coordinated or subordinated clauses rarely occurred in their speech samples (Topbaş and Güven 2011).

Topbaș and Güven (2008) compared the sentence repetition data of monolingual Turkish-speaking children aged 2;0 to 7;0 with DLD (n = 30) with those of children with TD (n = 30). The aim of the study was to identify differences between TD and DLD children’s capacity to repeat simple versus complex (subordinate) clauses, as well as to identify any differences in error types. As material, they used SRT items from TEDİL (Topbaș and Güven 2011), which is an adaption of the Test of Early Language Development (TELD-3) developed by Hresko et al. (1999). The results concerning subordinate clauses in this study indicate that children with DLD omitted subordinate clauses. They also deleted non-obligatory constituents, such as adverbial phrases.

Topbaş (2010) focused on a quantitative analysis of SRT items for the standardization of TEDİL with the assumption that the difference in the abilities of children with TD and DLD to repeat sentences of syntactic complexity from the SRT would identify DLD. For comparison, 30 TD and 30 DLD children were sorted into five age groups: 3;0 (n = 5), 4;0 (n = 5), 5;0 (n = 9), and 6;0–7;0 (n = 11). An analysis of the coordinate clauses and subordinate clauses was conducted with respect to their type (adverbial clause, relative clause, noun clause). They found that children with DLD produced remarkably more errors in subordinate clauses than in coordinations, mainly by the omission of significant elements of the sentence (Topbaş 2010). Example (37) depicts a relative clause with -DIK having the structure of a genitive possessive. The possessed constituent is part of the direct object of the verb. While repeating, the child omits the relativized constituent with the -DIK particle, which is marked for possessive agreement with the subject and the genitive case marker in the subject. As for the adverbial clauses, whereas children with TD made errors in 14% of the test items, children with DLD made errors in 30% of the stimuli, such as the substitution error shown in example (38), wherein the child replaces -Ip “and/and then” by the earliest acquired converb -IncA “when” (Topbaş 2010). With respect to relative clauses, omission of the subordinate clause was observed in both groups; in the production of noun clauses, the TD group produced no errors while the DLD group did (7%). In Example (39), instead of using a nominal clause constructed with the -MAK suffix inflected with the accusative case, the child constructs coordinated clauses with identical inflections for negation and person (Topbaş 2010). Whereas children with DLD produced errors in both simple and complex SRTs (including subordinate clauses), the TD children made errors in only 3% of their subordinate clauses (Topbaş 2010). In the repetition of sentences for which complexity and length increase, morphosyntactic errors were observed to be the major difficulties for children with DLD.

| (37) | Target | ||||

| Ece | anne-si-nin | al-dığ-ı | oyuncağ-ı | kaybet-ti. | |

| Ece | mother-3SG.POSS-GEN | buy-PART-3SG.POSS | toy-ACC | lose-PAST | |

| “Ece lost the toy her mother bought.” (Topbaş 2010, p. 157) | |||||

| Repetition by a child with DLD | |||||

| Ece | anne-si (*0) | (0) | oyuncağ-ı | kaybet-ti | |

| Ece | mother-3SG.POSS | toy-ACC | loose-PAST | ||

| *“Ece her mother her toy lost.” | |||||

| (38) | Target | ||||

| Çocuk-lar | (cam-ı | kır-ıp) | kaç-tı-lar. | ||

| child-PL | (window-ACC | break-VN | run away-PAST-3PL | ||

| “Having broken the window, the children ran away.” (Topbaş 2010, p. 157) | |||||

| Repetition by a child with DLD | |||||

| Çocuk-lar | cam-ı | kıy-ınca | kaç-tı-(0) | ||

| Child-PL | window-ACC | break-VN | run away-PAST | ||

| “When the children broke the window, they run away.” | |||||

| (39) | Target | ||||

| Barış | tek başına | çalış-ma-yı | sev-me-z | ||

| Barış | alone | study-FNOM-ACC | like-NEG-AOR | ||

| “Barış doesn’t like studying by himself.” (Topbaş 2010, p. 157) | |||||

| Repetition by a child with DLD | |||||

| Barış | kendi | çalış-ma-z | iste-me-z | ||

| Barış | himself | study-NEG-AOR | want-NEG-AOR | ||

| “Barış | doesn’t work doesn’t want.” (Topbaş 2010, p. 157) | ||||

To summarize, overlap areas between DLD in Turkish and Heritage Turkish can be listed as the use of fewer subordinate clauses or avoiding subordination, the use of juxtaposition of finite clauses instead of subordination, and the unconventional use, particularly substitution, of subordinators. In sentence repetition, morphological errors in noun and verb morphology have been frequently observed. Finally, it should be investigated whether sentential fragments, which are cross-linguistically characteristic for DLD, are also attested in heritage Turkish children.

2.8. The Current Study

Since subordination in Turkish appears to be affected by language contact in the heritage setting, this study examines whether it can still be used as a clinical marker for DLD in child heritage bilinguals. To this end, the study provides a detailed analysis of subordinate constructions in the utterances of child heritage BiTDs and BiDLDs, comparing them to typically developing lL2 BiTD children and adult heritage bilinguals. The reason for including adult heritage bilinguals in this study is that adult heritage bilinguals use a variety divergent from the Standard Turkish baseline, whereas heritage children still receive input in HL. Even if both groups live under similar sociolinguistic conditions, such as living in an L2-dominant country, the differences include the rapid switch to L2, decreasing input in HL due to increasing time in school, and the absence of formal education in the HL (Polinsky 2018). lL2 BiTD children were also included in this study because the language abilities of late successive bilinguals, who are first-generation children, are better than those of simultaneous and successive bilingual children in the HL (Montrul 2016; Paradis et al. 2021). This results from their exclusive exposure to a non-heritage variety for a long period, which is acquired in a qualitatively rich language environment, and their access to formal language registers during the school-age period.

Considering the features of Heritage Turkish and DLD markers regarding subordinate clauses, the following research questions are addressed in this study:

- How do heritage BiDLD children compare to their heritage BiTD peers, lL2 BiTDs, and adult heritage bilinguals in their production of Standard Turkish subordinate constructions in a sentence repetition and a narrative task?

- Which age and input variables predict variance in performance in the use of subordination in Standard and Heritage Turkish?

- Given the potential overlap between features of Heritage Turkish and clinical markers of DLD in Standard Turkish, can subordination identify DLD in the bilingual German–Turkish heritage context? Does performance on subordinate constructions improve if certain features of Heritage Turkish are considered?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

This study compares the data of 13 child heritage bilinguals with and without DLD (age range 5;11–12;0) to 8 lL2 BiTD children (age range 7;2–12;6) and 10 adult heritage speakers (age range 20;3–25;10). The bilingual children were recruited within the research project BiliSAT7 (Bilingual Language Development in School-age Children with/without Language Impairment with Arabic and Turkish as first languages) from kindergartens, schools, community centers, and speech–language therapy facilities in different parts of Germany. The adult heritage bilinguals were recruited at the University of Applied Sciences Frankfurt. At the time of testing, they were attending Turkish language courses at the university in order to improve their academic skills in Standard Turkish. Written informed consent, approved by the “Kommission für Forschungsfolgenabschätzung und Ethik” of the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, was obtained from all the adult participants and the children’s parents/legal guardians for the purpose of data collection and analysis.

All the child and adult heritage bilinguals were born in Germany and have been primarily exposed to the Heritage Turkish variety in their day-to-day life alongside the ambient language, German, to which they were exposed either from birth (i.e., simultaneous bilingualism) or upon kindergarten entry around age 3–4 (early successive bilingualism). The participants of the late successive bilingual typically developing group (lL2 BiTD), on the other hand, were born in Turkey and moved to Germany at school age and beyond, i.e., they started acquiring L2 German at a considerably older age than the heritage groups and were exclusively exposed to the Standard Turkish variety in a monolingual environment for an extended period of time; hence, lL2 bilinguals are expected to retain superior Standard Turkish abilities relative to their heritage bilingual peers. The clinical status of each bilingual child as likely to have typical language development (BiTD) or developmental language disorder (BiDLD) was verified using an extensive evaluation procedure based on standardized language assessment in both of the child’s languages adapting pathology cut-off points according to the language dominance of the child (cf. Thordardottir 2015). For assessment of L2 German, the LiSe-DaZ (Schulz and Tracy 2011), WWT 6–10 (Glück 2007), TROG-D (Fox 2009), and PLAKSS (Fox-Boyer 2014) were used. The latter L2 tests assess different language domains, including expressive and receptive vocabulary (WWT) and morpho-syntax comprehension (LiSe-DaZ, TROG-D) and production (LiSe-DaZ), as well as phonology (PLAKSS). L1 Turkish abilities were assessed using the TEDİL test battery (Topbaş and Güven 2011), which assesses receptive and expressive (standard) language skills. Following the project’s experimental protocol outlined in Hamann and Abed-Ibrahim (2017) and Tuller et al. (2018), a bilingual child is to be assigned to the BiDLD group if she scores within the pathology range on (monolingual) norm-referenced tests in two language domains in both her L1 and L2 after adjusting monolingual cut-off points in accordance with the child’s language-dominance as estimated by the Parents of Bilingual Children Questionnaire (PaBiQ; Tuller 2015). However, the TEDİL test battery only offers two global composite scores for production and comprehension without providing separate norms for the individual language domains (i.e., morphosyntax, vocabulary, and phonology) assessed in the expressive and receptive modules of the test; hence, Turkish bilingual children were assigned to the BiDLD group if they scored in the pathology range in either of the receptive or productive subtests. A participant overview (based on the verified clinical status) is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants: and overview of background variables related to bilingualism (mean, SD, and range), N/A: not applicable.

Comparisons of the latter background variables between the child groups (heritage BiTD, heritage BiDLD, and lL2 BiTD) revealed significant overall effects as a function of group on all the variables expect for chronological age (Kruskal–Wallis test): L2 AoO [Χ2 (2, n = 21) = 14.590, p = 0.001], L2 LoE [Χ2 (2, n = 21) = 9.018, p = 0.011], early L1 exposure [Χ2 (2, n = 21) = 10.353, p = 0.006], current L1 use at home [Χ2 (2, n = 21) = 8.038, p = 0.018], L1 richness [Χ2 (2, n = 21) = 8.362, p = 0.015], and current L1 skills [Χ2 (2, n = 21) = 12.448, p = 0.002]. Concerning chronological age, only a marginally significant effect emerged [Χ2 (2, n = 21) = 5.694, p = 0.058], suggesting that the bilingual child groups are comparable with respect to this variable.

Subsequent Mann–Whitney U tests with Holm–Bonferroni adjustment showed no significant differences between the heritage BiTDs and heritage BiDLDs for any of the input variables, implying comparable exposure patterns between the groups. Interestingly, no significant effects emerged for current L1 skills (oral abilities) as estimated by the children’s parents either. Compared to their heritage BiTD and BiDLD peers, the lL2 BiTDs were exposed to L2 German at a significantly older age and had a significantly shorter length of exposure to L2. Moreover, the lL2 BiTDs differed from their heritage BiTD and BiDLD peers by having significantly earlier and more current L1 input (Standard Turkish), richer L1 environments, and better L1 skills according to parental estimates (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons on input background variables and current L1 skills (Mann–Whitney U tests).

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. The Parental Questionnaire PaBiQ

The PaBiQ (Tuller 2015), developed during COST Action IS0804, was used to collect background information including the children’s age, past and current quantity and quality of L1/L2 input and use, as well as risk factors for DLD (Hamann and Abed-Ibrahim 2017). Importantly, it allowed the calculation of a purely experiential language-dominance index that served as the basis for adjusting pathology cut-off points. The age and input variables considered for the current study are as follows: chronological age, age of onset of sustained exposure to the L2 (AoO_L2), length of exposure to the L2 (LoE_L2), early L1 exposure (measured by frequency of early language use and exposure and diversity of exposure contexts before the age of 4), current L1 use (measured by the proportion of relative L1 use within the family), and L1 linguistic richness (richness of the L1/HL language environment within and outside the child’s home). Additionally, the current L1 skills based on parental judgement were explored as a further potential predictor of performance. The Turkish translation of the PaBiQ was used with the children’s parents either in a phone- or face-to-face interview. Relevant background information, such as age, AoO_L2, and LoE_L2, were also collected for adult heritage bilinguals.

3.2.2. Elicited Production of Turkish Subordinate Clauses

The TODİL Sentence Repetition Task

For elicited production of subordinated construction in Turkish, the sentence repetition subtest from the TODİL8 test battery, which is designed for testing the Turkish competence of children between 4;0-8;11 (Topbaş and Güven 2017), was used. The subtest consists of 36 sentences increasing in complexity. According to the test manual, the test is to be aborted following five consecutive incorrect responses; however, for the purposes of the current study, the subtest was administered in full and used as a corpus to extract subordinated constructions. For an overview of the subordinated constructions investigated in this study, see Table 3. Note that some sentences feature deep embedding, hence providing more than one obligatory context.

Table 3.

Overview of sentence types with subordinate constructions in the TODİL SRT (Topbaş and Güven 2017) and number of obligatory contexts per structure type.

MAIN Narrative Task

The MAIN (Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives; Gagarina et al. 2012) was constructed during COST Action IS0804 as part of the Language Impairment Testing in Multilingual Settings (LITMUS) toolbox with the aim of disentangling typical from impaired bilingual language development (Armon-Lotem et al. 2015). It is an assessment tool used to elicit narratives from bilingual children (3–10 years) from different linguistic, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds and can be used to assess narrative skills (production and comprehension) in both languages of a bilingual child. It has different elicitation modes, (i.e., model story, retelling, and telling) based on four parallel stories, each with a six-picture sequence. In this study, the narratives were not evaluated for story grammar according to the MAIN protocol. Instead, the elicited utterances of bilingual children and adults in the production and comprehension parts were used as semi-spontaneous language samples to extract subordinate constructions, following the recommendation of Paradis et al. (2022). Note that the comprehension mode features a number of questions that require the production of subordinate constructions, e.g., Warum spring die Katze hoch? “Why does the cat jump up the tree?” As in Bohnacker and Karakoç (2020), the latter questions (6 in total) were treated as obligatory contexts for subordinated clauses in the comprehension part of the MAIN.

3.3. Scoring

Responses from children and adults were obtained in individual sessions, comprising the data corpus used for this study. The responses were recorded using special dictaphones in a quiet room. Two linguistically trained raters independently transcribed, verified, and coded the data (ensuring that the percentage of agreement was at least 90%).

For each participant, the subordinate constructions collected via TODIL’s SRT and the production and comprehension parts of the MAIN narrative task were analyzed for morphological form and syntactic function using both Standard and Heritage Turkish as reference varieties, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Examples of responses not conforming to Standard Turkish, structure types are given in bold.

For the SRT, the scoring procedure followed the test handbook, with 1/0 for correct/incorrect repetition of a sentence. As the test manual uses the Standard Turkish variety as a baseline, sentences in SRT in this study were first scored as correct (target structure only disregarding lexical errors not affecting the targeted construction) or incorrect, using Standard Turkish as a baseline. Incorrect repetitions, i.e., responses not conforming to the Standard Turkish variety were scored again to determine whether they would constitute target-like responses in Heritage Turkish. The latter category is referred to as correct with respect to either Standard or Heritage Turkish. Responses that were non-target-like in either Standard or Heritage Turkish were subsequently analyzed for error types, which were grouped into 3 categories: null responses, responses that constitute DLD markers in Standard Turkish, and others. The category “others” includes all the subordinate clauses that could not be scored as previously described. The sentences in the MAIN comprehension part were scored in the same way as those in the SRT since the obligatory contexts for subordination in SRT and MAIN comprehension are directly elicited via the tasks. As to the MAIN production part, the rate of successful subordinations was calculated as a percentage of the total number of utterances produced by a participant taking either Standard or Heritage Turkish as a baseline. Examples of responses not conforming to Standard Turkish, responses categorized as target-like in Heritage Turkish, and errors, namely, DLD markers and other error types, are provided in Table 4.

3.4. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS 27 software (IBM Corp. Released 2020) was used to conduct statistical analyses. Due to the small sample sizes and violation of the normality assumption of parametric tests, nonparametric tests, such as the Kruskal–Wallis test, were conducted for group comparisons. A post hoc Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni–Holm correction was run to further explore the between-group differences. Note that the Bonferroni–Holm correction is less conservative compared to the Bonferroni correction, thereby reducing the risk of type I and type II statistical errors. The effect sizes (r) were also calculated, with an effect size > 0.5 corresponding to a strong effect.

The background variables obtained via the PaBiQ were examined using non-parametric Spearman correlations for significant correlations with the percentages of correct and incorrect subordinate construction use, which were treated as dependent variables in the subsequent hierarchical regression analyses. As potential predictors, only those background variables yielding significant moderate-to-strong correlations with the dependent performance measure were selected as potential predictors. These were later entered as independent variables in regression modelling to determine which background factors influenced the performance on subordination constructions in the different tasks using both standard and Heritage Turkish as reference varieties. To this end, we report the standardized regression coefficients, the R2 values, and the p-values of the most parsimonious regression models.

4. Results

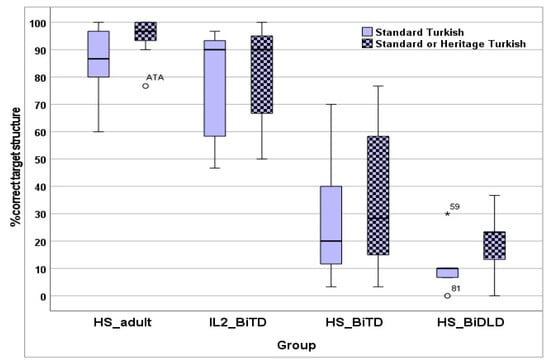

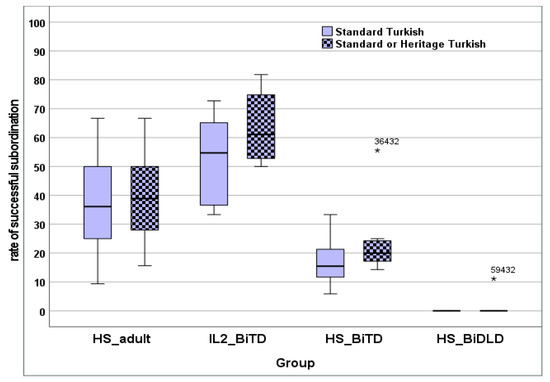

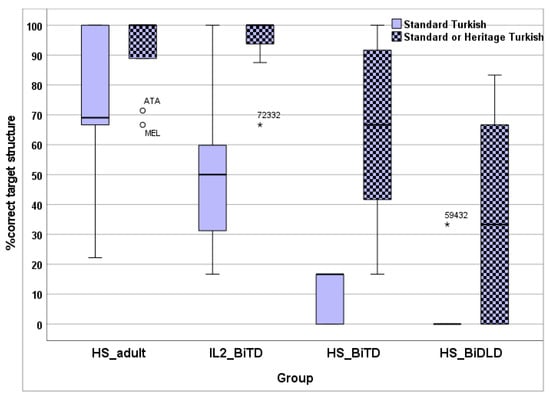

4.1. TODİL SRT: Subordinate Clause Comparisons