Abstract

Factivity alternations received at least two kinds of explanations in the literature: there are approaches that attribute the two readings to two different LFs and approaches that derive the presence/absence of a factive inference by appealing to general pragmatic mechanisms. In this paper I investigate verbs displaying two different kinds of factivity alternations in Azeri and argue for the former view of how factivity alternations emerge.

1. Introduction

This paper is concerned with the phenomenon of factivity alternations: attitude verbs exhibiting factive inferences in some circumstances but not in others. For example, consider an example from Turkish in (1).1

- (1)

- Turkish (Özyıldız 2017b, ex. (39))

- a.

- Dilara [Aybike’nin sigara içtiğini] blyor.Dilara Aybike cigarette smoke.nmz knows‘Dilara knows that Aybike smokes cigarettes.’

- b.

- Dilara [Aybike’nin sgara içtiğini] biliyor.Dilara Aybike cigarette smoke.nmz knows‘Dilara believes that Aybike smokes cigarettes.’

- c.

- …ama içmiyor. ✘ after (1a), ✓ after (1b)but smoke.neg‘…but she doesn’t.’

Availability of the factive inference with the verb biliyor ‘know/think’ depends on where the main stress falls within the sentence: if it falls on the attitude verb, we get the factive inference and the continuation in (1c) is infelicitous, but if it falls elsewhere, for example within the embedded clause as in (1b), we do not get such an inference and the continuation in (1c) is felicitous.

There are two general ideas about how factivity alternations can emerge, both of which share the intuition that the factive inference is not a lexical presupposition always present in the meaning of the attitude verb. The first idea is that the embedded proposition can become presupposed via general pragmatic mechanisms (Abusch 2002, 2009; Abrusán 2011, 2016; Jeong 2021; Simons et al. 2017; Tonhauser 2016, a.o.): what we presuppose is dependent on the information structure of the sentence, in particular on the alternatives to the sentences that we are considering. I will call approaches that follow this idea pragmatic approaches to factivity alternations. The second idea is that factivity alternations emerge because attitude verbs can occur in different syntactic structures (Özyıldız 2017a, 2017b; Bondarenko 2020, a.o.): only some LFs (Logical Forms) in which the roots of factivity-alternating verbs can be inserted give rise to factive inferences. I will call approaches that follow this idea structural approaches.

The question that arises is: how do we distinguish between the two approaches? Data like in (1) lends itself well to both kinds of explanations (see Jeong (2021) vs. Özyıldız (2017b)): it could be that focus marking on certain verbs generates alternatives that give rise to the factive presupposition, or that a structural difference between (1a) and (1b) gives rise to the prosodic effects that we see. This paper examines factivity-alternating verbs in Azeri and provides an argument in favor of the structural approach.2 The gist of the argument is as follows. If factive inferences like in (1a) arise due to the nature of alternatives that placing focus on attitude verbs evokes, together with some general pragmatic principles, then we do not expect the structure of the complement clause and the LF it is in to matter for whether the factive inference will be present. If on the other hand it is a structural difference that is responsible for presence/absence of factive inferences, we expect that altering the syntactic configuration could in principle eliminate the observed prosodically-conditioned factivity alternation. I argue that Azeri has factivity-alternating verbs that fit the second description.

Just like Turkish (Özyıldız 2017b) and Korean (Jeong 2021), Azeri has a class of verbs that participate in prosodically-conditioned factivity alternations, with exactly the same prosodic pattern that was observed for Turkish and Korean: if the main stress falls on the attitude verb, there is a factive inference that the embedded proposition is true, but if it falls elsewhere, no factive inference is derived, (2).

- (2) a.

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] bil-ir.Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc know-prs‘Leyla knows that Ömer stole the car.’

- b.

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] bil-ir.Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc know-prs‘Leyla thinks that Ömer stole the car.’

- c.

- …amma bu elə deyil. ✘ after (2a), ✓ after (2b)but this ela be.neg.prs‘…but this is not so.’

In addition to the preverbal nominalized clauses as in (2), Azeri has postverbal non-nominalized CPs with the complementizer ki. Interestingly, the same verbs disallow non-factive readings with ki-clauses no matter what the prosody is, (3a). However, there is a different way to get non-factive readings: adding a particle elə ‘so’ before the verb eliminates the factive inference (to my knowledge, this fact was first observed in (Lee 2019, ex. (16))).

- (3) a.

- Leyla bil-ir [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla know-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla knows that Ömer stole the car.’

- b.

- Leyla elə bil-ir [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla ela know-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla thinks that Ömer stole the car.’

- c.

- …amma bu elə deyil. ✘ after (3a), ✓ after (3b)but this ela be.neg.prs (regardless of the prosody)‘…but this is not so.’

I argue that in a purely pragmatic approach the co-existence of the two different factivity alternations with the same verbs is difficult to account for: it is not clear why the form of the complement should determine whether we will see an alternation conditioned by prosody or an alternation conditioned by the presence of a certain particle. I propose that a version of the structural approach argued for in (Özyıldız 2017b, 2018), according to which factive and non-factive readings correspond to distinct LF representations, allows for a natural explanation of these data, once independently motivated syntactic differences between the two kinds of complements are taken into account (Halpert and Griffith 2018).

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 I discuss two proposals about prosodically-conditioned factivity alternations: Jeong (2021)’s proposal about Korean, which represents the pragmatic approach, and Özyıldız (2017b)’s proposal about Turkish, which represents the structural approach. In Section 3, I discuss the two factivity alternations that we observe in Azeri. Section 4 presents my proposal: I argue that linking the presence of factive inferences to scopal differences (Özyıldız 2017b) can explain the differences we see between the two kinds of complement clauses. Section 5 discusses a difference in projective behavior observed with the two verbs studied in this paper, and hypothesizes how it could be captured. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Two Approaches to Factivity Alternations

This section discusses two proposals for the prosodically-conditioned factivity alternations: the pragmatic approach (Jeong 2021) and the structural approach (Özyıldız 2017b).

2.1. The Pragmatic Approach (Jeong 2021)

The pragmatic approach takes inspiration in the literature on presupposition projection with semi-factive predicates like discover or remember (Heim 1983; Karttunen 1976; Abusch 2002, 2009; Simons 2005, 2013; Beaver 2004; Abrusán 2011, 2016; Simons et al. 2017; Tonhauser 2016, a.o.). The observation in this literature is that whether the embedded proposition is taken to be true in sentences where these predicates are embedded under some operators depends on the information structure of the sentence, which is reflected in the prosody. Consider the example (4):

- (4) a.

- If the T.A. discovers that your work is [plagiarized],I will be [forced to notify the Dean]. your work is plagiarized

- b.

- If the T.A. [discovers] that your work is plagiarized,I will be [forced to notify the Dean]. ⇝ your work is plagiarized(Beaver 2004, 27, ex. (73c)–(73d))

If the focus falls on the word plagirized within the embedded clause, (4a), we do not infer that the work of the student that the speaker of the sentence addresses is known to be plagiarized. If however the focus falls on the attitude verb discovered, (4a), we infer that it is known that the work of the student is plagiarized. This sensitivity to information structure has led to the proposal that the embedded propositions that occur with predicates like discover are not lexical presuppositions, but presuppositions that arise conversationally: these are entailments that can project and thus become presupposed when they are part of the not-at-issue content. The implementations of this general idea vary, but here is a toy illustration that we could apply to the example in (4):3

- (5) a.

- ALT = {plagiarized(your-work) ∧ (TA,plagiarized(your-work)),original(your-work) ∧ (TA,original(your-work))}

- b.

- ∨ALT = ∃p [p(your-work) ∧ (TA,p(your-work))]

- (6) a.

- ALT = {plagiarized(your-work) ∧ (TA,plagiarized(your-work)),plagiarized(your-work) ∧ (TA,plagiarized(your-work))}

- b.

- ∨ALT = plagiarized(your-work)

Focus activates alternatives: propositions in which the focus marked element is substituted by a different contextually salient element. For example, we could hypothesize that a salient alternative to the focus-marked plagiarized in (4a) is original. Then the set of alternatives ALT will contain the prejacent and the proposition T.A. discovers that your work is original, (5a). If we take the inference that the embedded proposition is true to be an entailment, the prejacent will have the conjunctive form Your work is plagiarized and The T.A. discovers that your work is plagiarized, and its alternative will have the conjunctive form Your work is original and The T.A. discovers that your work is original. If we place the focus on the attitude verb, we will activate different alternatives. E.g., we could hypothesize that a salient alternative to the focus-marked discover is not discover.4 Then the ALT set will contain propositions Your work is plagiarized and The T.A. discovers that your work is plagiarized and Your work is plagiarized and The T.A. does not discover that your work is plagiarized, (6a).

It has been argued in the literature that the disjunction of the set of alternatives is presupposed: i.e., when we activate alternatives, we presuppose that one of the propositions in the ALT set is true (Abusch 2002, 2009; Abrusán 2016; Simons et al. 2017, a.o.). Disjoining the propositions in the ALT in (5a) will only generate a presupposition that there is some property true of the student’s work that the T.A. will discover. Thus, that the work is plagiarized will not be a presupposition of this sentence. If on the other hand we disjoin the propositions in the ALT in (6a), we will generate the presupposition that the student’s work is plagiarized. Thus, the fact that discover exhibits a factive presupposition in some cases but not in others is explained by discover entailing that the embedded proposition is true, and having general pragmatic principles governing how entailments project.

The similarity between the prosodic pattern in (4), and the prosodically-conditioned alternations in Turkish, (1), Azeri, (2), and Korean, (7), is quite intriguing: in both cases having main stress of the sentence on the attitude verb leads to a factive inference, whereas putting main stress on other elements of the sentence allows for non-factive readings.5

- (7)

- Prosodically-conditioned factivity alternation in Korean (Jeong 2021, p. 2)

- a.

- Sun-eun [Byul-i pati-e o-n-jul] an-da.Sun-nom Byul-nom party-dat come-ptcp-c know/believe-decl‘Sun knows that Byul came to the party.’⇝ Byul came to the party

- b.

- Sun-eun [Byul-i pati-e o-n-jul] an-da.Sun-nom Byul-nom party-dat come-ptcp-c know/believe-decl‘Sun knows that Byul came to the party.’Byul came to the party

Jeong (2021) proposed to extend the ideas developed for prosodically-conditioned projection behavior of semi-factives to the prosodically-conditioned factivity alternations in unembedded environments which we see in Korean and in Turkic languages. The main difference between the two phenomena is that it is commonly assumed that in unembedded sentences, verbs like discover entail the truth of their complement, whereas what we see in Korean, Turkish and Azeri is that even in the unembedded contexts, the truth of the complement is not always entailed. Jeong (2021) proposes that factivity-alternating verbs like al- ‘know/believe’ in Korean do not lexically entail the embedded proposition, (8a): they just denote an epistemic relation () between the attitude holder and the embedded proposition.

- (8) a.

- factivity-alternating:al- ‘know/believe’: x p al- = (x,p)

- b.

- always factive:moreu- ‘not know’: x p moreu- = (x,p) ∧ p(w)

- c.

- always non-factive:mit- ‘believe’: x p mit- = (x,p)

This makes such verbs similar to completely non-factive verbs like mit- ‘believe’, which denote a doxastic relation () between the attitude holder and the embedded proposition, (8c). The difference between the two verbs lies in what lexical alternatives they have: whereas al- ‘know/believe’ has an always factive moreu- ‘not know’ (8b) as its alternative, there is no lexical item that would describe the same doxastic relation as mit-, but have a factive presupposition. The factive inference of moreu- is depicted in (8b) as entailment, but we could also encode it as a lexical presupposition.

Jeong (2021) proposes a pragmatic constraint on alternative sets that can be generated: Uni-dimensional Heterogeneity of Alternatives (UHA), (9).

- (9)

- Uni-dimensional Heterogeneity of Alternatives (UHA) (Jeong 2021, p. 15)Elements of a discourse salient set of alternatives ALT that enter into the disjunctive pragmatic inference ∨ALT only allow for a single dimension of semantic contrast.

This constraint does not allow propositions in the alternative set to vary across several dimensions. Let us now see how UHA can explain the behavior of factivity-alternating verbs.

When we have a sentence with focus on the factivity-alternating verb, (7a), our ALT will vary along two dimensions, (10a): the relation between the embedded proposition and the agent’s mental state ( vs. ¬) and the relation between the embedded proposition and the actual world (no relation vs. came-to-the-party(Byul)(w)). Thus, it is not UHA-compliant.

- (10) a.

- ALT for (7a) before UHA ={(Sun,came-to-the-party(Byul)),(Sun,came-to-the-party(Byul)) ∧ came-to-the-party(Byul)(w)}

- b.

- ALT for (7a) after UHA ={(Sun,came-to-the-party(Byul)) ∧ came-to-the-party(Byul)(w),(Sun,came-to-the-party(Byul)) ∧ came-to-the-party(Byul)(w)}

- c.

- ∨ALT: came-to-the-party(Byul)(w)

In order to observe UHA, al- will need to be enriched and be interpreted as (x,p) ∧ p(w), giving us the UHA-compliant ALT in (10b). Once we have such an ALT, the disjunctive presupposition that we will get is that the embedded proposition is true, as it will be entailed by both propositions in ALT, (10c). Hence, we get a factive reading.

When we have a sentence with focus not on the attitude verb, for example, with focus on the embedded subject, (7b), the ALT we will produce by substituting the embedded subject in the prejacent with other individuals will already be UHA-compliant, as it will vary only across one dimension, (11a), and thus no enrichment will be needed.

- (11) a.

- ALT for (7b){(Sun,came-to-the-party(Byul)), (Sun,came-to-the-party(Jin)),…}

- b.

- ∨ALT: ∃x[(Sun,came-to-the-party(x))]

The disjunctive presupposition that we will get is that there is some individual x such that Sun believes that x came to the party. Thus, the factive inference will not be derived.

An immediate worry about extending this account to languages like Azeri is that Azeri doesn’t seem to have a negative factive verb like moreu ‘not know’ that would be a counterpart to its alternating verb bilmək ‘think/know’. I would like to suggest though that there might be a plausible modification to Jeong (2021)’s account that would allow us to maintain the core insight of her proposal. We will need the ingredients in (12):

- (12) a.

- Focus on verbs can signal verum focus, and give rise to ALT = {V, ¬V}.

- b.

- Negating certain verbs gives rise to the requirement that the embedded proposition is presupposed.

The assumption in (12a) is straightforward: verum focus in Azeri is realized by putting the main stress on the verb, as is illustrated in (13). Intuitively, in (13) the relevant set of alternatives that we evoke is {Hasan didn’t eat pizza, Hasan ate pizza}, and the speaker B emphasizes that it is the positive sentence which is true.

- (13) A:

- Həsən pizza-nı ye-mə-di.Hasan pizza-acc eat-neg-pst‘Hasan didn’t eat pizza.’

- B:

- Həsən pizza-nı ye-di.Hasan pizza-acc eat-pst‘Hasan did eat pizza.’

Thus, we could hypothesize that in sentences like (2a), where putting prominence on the verb leads to factivity, we evoke {bilmək, ¬bilmək} alternatives by having verum focus.

The second assumption is more controversial, but it is based on the observation that matrix negation seems to often affect the status of the embedded proposition. For example, Djärv (2019) observes that even with completely non-factive verbs like tell and think, negation gives rise to a requirement that the embedded proposition must be discourse-old:

- (14)

- [Uttered out of the blue:] Guess what – / You know what – (Djärv 2019, p. 35)

- a.

- John told me that [Bill and Anna broke up].

- b.

- John thinks that [Bill and Anna broke up].

- c.

- #John didn’t tell me that [Bill and Anna broke up].

- d.

- #John doesn’t think that [Bill and Anna broke up].

In Azeri, my consultant did not like non-factive readings of negated verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’. For example, in (3b) we have seen that the verb bilmək ‘think/know’ is non-factive when it occurs with the particle elə and a ki-clause. As we see in (15), it does not seem to be possible to successfully negate this non-factive sentence.6

- (15)

- #Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb, Leyla da elə bil-m-irÖmer car-acc steal-neg-p Leyla also ela know-neg-prs[ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Ömer didn’t steal the car, and Leyla doesn’t think that Ömer stole the car.’

Thus, it could be that negating verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’ forces the embedded proposition to be presupposed. While why negation would behave this way is a mystery, if it does have this effect, then we will arrive at the same alternative set in (10a) for verbs like bilmək that bear verum focus. Verum focus on bilmək will evoke alternatives {bilmək(x,p), ¬bilmək(x,p)}, and if negation makes the embedded proposition presupposed, we will get the set {bilmək(x,p), ¬bilmək(x,p) ∧p}. This set is not UHA-compliant, and thus will have to undergo an enrichment, leading to ALT = {bilmək(x,p) ∧p, ¬bilmək(x,p) ∧ p}. As discussed above, such an ALT will give rise to the factive presupposition.

To sum up, the pragmatic approach to prosodically-conditioned factivity alternations suggests that the alternation arises because focus marking activates a set of alternatives ALT, which is constrained by pragmatic principles: first, disjunction of all propositions in ALT is presupposed to be true; second, propositions in ALT can only vary along a single dimension (UHA). When we place focus on the attitude verb, the disjunctive presupposition that we will derive is the factive inference. When we place focus elsewhere, the disjunctive presupposition will not give rise to factivity.

2.2. The Structural Approach (Özyıldız 2017b, 2018)

Özyıldız (2017b, 2018) suggests an account of prosodically-conditioned factivity alternations that does not rely on focus marking and activation of alternatives. Instead, he proposes that the prosodic contrast that we observe in examples like (1), repeated below as (16), is the effect of a syntactic difference between factive & non-factive reports: embedded clauses in factive sentences undergo QR, but embedded clauses in non-factive sentences stay in situ. This difference in syntactic configuration has consequences for where the main sentence stress will fall, which will give rise to two different prosodic patterns.

- (16)

- Turkish (Özyıldız 2017b, ex. (39))

- a.

- Dilara [Aybike’nin sigara içtiğini] blyor.Dilara Aybike cigarette smoke.nmz knows‘Dilara knows that Aybike smokes cigarettes.’ ⇝ Aybike smokes.

- b.

- Dilara [Aybike’nin sgara içtiğini] biliyor.Dilara Aybike cigarette smoke.nmz knows‘Dilara believes that Aybike smokes cigarettes.’ Aybike smokes.

Özyıldız (2017b) assumes a regular non-factive Hintikkan (Hintikka 1962) semantics for verbs like Turkish biliyor ‘know/believe’, (17).

- (17)

- bil-(w)(p)(x) = 1 ifffor all worlds w’ compatible with what x believes at w, p(w’) = 1.

Furthermore, he assumes that nominalized clauses in Turkish denote regular propositions:

- (18)

- 〚Aybike’nin sigara içtiği〛(w)=1 iff Aybike smokes at w.

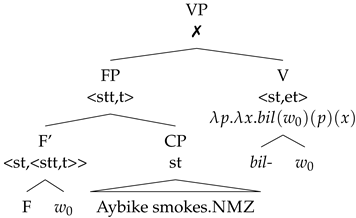

The sentence in which the main sentence stress falls inside of the embedded clause, e.g., (16b), has the LF in (19), in which the verb directly takes the clause as its argument.

- (19)

- LF for (16b)

The vP in (16b) will have the truth-conditions in (20): it will be true iff in all worlds compatible with Dilara’s beliefs in the world of evaluation, Aybike smokes.

- (20)

- 〚vP〛 = 1 ifffor all worlds w’ compatible with what Dilara believes at w, Aybike smokes in w’.

As we see, no factive inference arises from this LF.

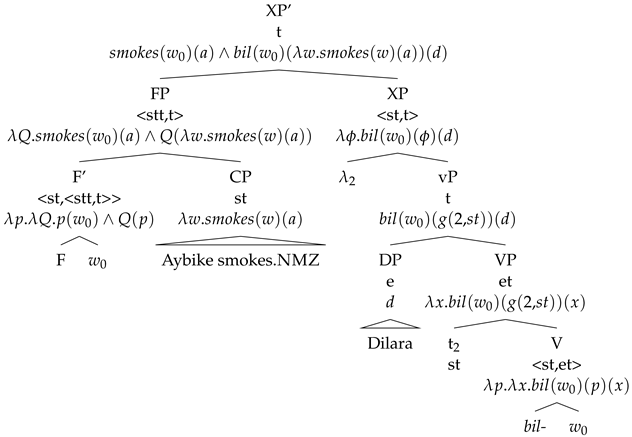

For the sentences with the main sentence stress falling on the attitude verb like (16a), Özyıldız assumes that the embedded clause first combines with a factive head F, which has the denotation in (21). After it combines with a world w and the embedded proposition, it also takes a function Q from propositions to truth-values as its argument, and then returns a truth-value. F asserts two things: that the embedded proposition is true in w, and that Q is true of the embedded proposition.

- (21)

- 〚F〛 = w.p.Q. p(w) ∧ Q(p)

Given its type (<stt,t>), FP will not be able to directly combine with the attitude verb, as this would lead to a type mismatch, (22). Thus, FP undergoes movement, leaving a trace of type <s,t>. FP then can combine with the vP that has undergone Predicate Abstraction, (23). This will result in the truth-conditions in (24).

- (22)

- FP doesn’t move: Type Mismatch

- (23)

- LF for (16a)

- (24)

- 〚vP〛 = 1 iff Aybike smokes at and for all worlds compatible with what Dilara believes in , Aybike smokes in .

The sentence will be true iff Aybike smokes in the world of evaluation, and Dilara believes that Aybike smokes. Thus, the factive inference is an entailment of sentences with the LF in (23). As Özyıldız (2017b, p. 43) notes, if we want this inference to be a lexical presupposition instead, we can modify the semantics of F accordingly to require that its p argument is true in the world of evaluation.

Now here is what Özyıldız (2017b) proposes about the syntax-prosody mapping. According to (Kahnemuyipour 2009), nuclear stress is assigned to the syntactically highest item within the spell-out domain of v. In an SOV language like Turkish, this means that the nucleus is some prosodic word close to the verb. So for example in a sentence like (25), the main sentence stress will fall onto the dative argument within the VP.

- (25)

- [[ ] [[ ] [ ]]]((Ali’nin arkadaşı) (sabahları) (okula gider))Ali’s friend mornings to school goes‘Ali’s friend goes to school in the mornings.’

If the domain of stress assignment is vacated by all other material, and the verb is the only thing left in the domain, the main sentence stress will fall onto the verb.

This general rule of stress assignment automatically derives the observed prosodic pattern with factivity-alternating verbs, (16), once the difference between the non-factive and factives LFs in (19) and (23) is assumed. In a non-factive LF, (19), the embedded CP is the highest phrase within v’s spellout domain, so the main stress should fall within it. Within the CP, the same process applies, and so the nuclear pitch accent will be placed onto the direct object ‘cigarette’. In a factive structure, (23), the embedded clause has vacated the vP, and so it is no longer eligible to receive the nuclear pitch accent. Thus, by the algorithm the verb itself is now the highest phrase within the stress domain, and so it receives the nuclear pitch accent. This derives the correlation between the prosody and factivity.

Assuming Azeri and Korean have the same algorithm for determining the main sentence stress, and the same factive head F, Özyıldız (2017b)’s proposal should be directly applicable to these languages without any changes: string-vacuous movement of the embedded clause should give rise to factive readings, and also remove the clause from the domain of stress assignment, resulting in the verb receiving the nuclear pitch accent; the absence of movement should correspond to a non-factive meaning, and since the embedded CP remains within the vP, the main sentence stress has to fall within it.

Now that we have seen the two approaches proposed for the prosodically-conditioned factivity alternations, let us turn to the Azeri data, and consider its attitude verbs that participate in two different kinds of factivity alternations.

3. Two Kinds of Factivity Alternations

The two kinds of factivity alternations that Azeri has seem to occur with the same verbs. Here I focus on two such verbs: bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’. I will be comparing them to the non-factive verb fikirləşmək ‘think’, which does not undergo the same alternations. Section 3.1 discusses the prosodically-conditioned alternation with diy-clauses, Section 3.2 discusses the factivity alternation that we observe with ki-clauses, and Section 3.3 discusses the particle elə in more detail.

3.1. Prosodically Conditioned Alternation with diy-Clauses

The prosodically-conditioned alternation in Azeri seems to be identical to the ones described for Turkish (Özyıldız 2017b, 2018) and Korean (Jeong 2021). It occurs with nominalized clauses with the complementizer diy (with allomorphs dig, duğ), (26).7

- (26)

- Həsən [Fatimə-nin yarışma-nı ud-duğ-u-nu]Hasan Fatima-gen competition-acc swallow-diy-3-accfikirləş-ir /bil-ir /xatırla-yır.think-prs /know-prs /remember-prs‘Hasan thinks/knows/remembers that Fatima won the competition.’

In (26) we see that the clause is overtly nominalized: it bears possessive marking and case, and the subject of the clause is marked with the genitive case. Such nominalized clauses are possible complements of both the verb fikirləşmək ‘think’ and the verbs bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’. Data on factivity with such clauses is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Factivity in diy-clauses.

With fikirləşmək ‘think’, sentences with diy-clauses do not give rise to factive inferences: in (27) we see that it is possible to negate the truth of the embedded proposition.

- (27)

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] fikirləş-ir, amma bu elə deyil.Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc think-prs but this ela be.neg.prsÖmər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb.Ömer car-acc steal-neg-p‘Leyla thinks that Ömer stole the car, but this is not so. Ömer didn’t steal the car.’

My consultant could not think of a prosody that would give rise to a factive inference to sentences with diy-clauses with the verb fikirləşmək ‘think’.

With verbs bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ on the other hand, sentences with diy-nominalizations exhibit factive inferences if the main stress falls on the attitude verb, but not if it falls elsewhere, e.g., somewhere within the nominalization, (28).

- (28)

- Prosodically-conditioned alternation with diy-clauses:Main sentence stress within the nominalization ⇔ non-factive reading;Main sentence stress on the matrix verb ⇔ factive reading.

This is illustrated in (29) and (30) with the two verbs.

- (29)

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] bil-ir /xatırla-yır,Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc know-prs /remember-prs…amma bu elə deyil. Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb.but this ela be.neg.prs Ömer car-acc steal-neg-p‘Leyla thinks/remembers that Ö. stole the car, but this is not so. Ö. did not steal the car.’

- (30)

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] bil-ir /xatırla-yır,Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc know-prs /remember-prs…#amma bu elə deyil. Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb.but this ela be.neg.prs Ömer car-acc steal-neg-p‘Leyla knows/remembers that Ö. stole the car, but this is not so. Ö. did not steal the car.’

I will postpone the discussion of projection of the factive inference that is observed with diy-clauses until Section 5, as the two verbs considered here do not show the same behavior.

Since the pattern in (29) and (30) is exactly the same as in Korean and Turkish, both the pragmatic (Jeong 2021) and the structural approaches (Özyıldız 2017b) can account for Azeri diy-clauses.

3.2. Factivity Alternation with ki-Clauses & the Particle elə

In addition to diy-clauses, verbs like fikirləşmək ‘think’, bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ can also combine with postverbal clauses with the complementizer ki:89

- (31)

- Fatima fikirləş-ir /bil-ir /xatırla-yır [ki Leyla park-da gəz-ir-di].Fatima think-prs /know-prs /remember-prs ki Leyla park-dat walk-ipfv-pst‘Fatima thinks/knows/remembers that Leyla was walking in the park.’

A notable property of ki-clauses is that they are head-initial, and they cannot occur in the position between the subject and the verb:

- (32)

- *[Subject CP Verb] with ki-clauses*Fatima [ki Leyla park-da gəz-ir-di] fikirləş-ir /bil-ir /xatırla-yır.Fatima ki Leyla park-dat walk-ipfv-pst think-prs /know-prs /remember-prs‘Fatima thinks/knows/remembers that Leyla was walking in the park.’

I will adopt the proposal in (Halpert and Griffith 2018) that the source of the restriction in (32) is that head-final verbs cannot combine with clauses that have head-initial complementizers. Halpert and Griffith (2018) argue that embedded ki-clauses in Azeri are base-generated as complements to head-final verbs, but have to extrapose to obey a linearization constraint on headedness. For example, they show that the matrix subject can bind into the embedded CP, suggesting that it c-commands the embedded clause, (33), and that a paratactic analysis, according to which ki-clauses are not really embedded, but adjoin outside of the verbal domain, cannot be right for Azeri (cf. paratactic analysis of Turkish ki-clauses in Kesici (2013), which however is not uncontroversial—see Kornfilt (2005) for the base-generation analysis of these clauses).

- (33)

- hərkəs de-di [ki on-a çox soyuğ-dur].everyone say-pst ki 3sg-dat too cold-cop‘Everyone said that s/he is too cold.’ (Halpert and Griffith 2018, ex. (15a))

The authors also show that it cannot be the case that the headedness of the verbs that occur with ki-clauses is just flipped, as that would predict that ki-clauses should appear immediately to the right of the first verb in structures with multiple embeddings, however we see that in sentences like (34) the clause appears to the right of the second verb:

- (34)

- [Samir [mən-i t inan-dır-mağ-a] çalış-ır] [ki at-lar kök-lər-iSamir 1sg-acc convince-caus-inf-dat try-prs ki horse-pl carrot-pl-accye-yir-lər].eat-prs-3pl‘Samir tries to convince me that horses eat carrots.’ (Halpert and Griffith 2018, ex. (22))

- (35)

- Final-Over-Final Constraint (FOFC)Within a clausal or nominal extended projection, if a phase head bears ⌃, then all the categorially alike heads in its complement domain (i.e., those making up the “spine” of the projection in question) must have ⌃. (Biberauer et al. 2009b, p. 711)

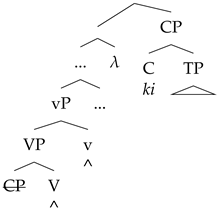

Biberauer et al. (2009b) propose that there is a linearization diacritic ⌃ which occurs on heads that want to be linearized to the right of their complements. The constraint in (35) then demands that if a head has such a diacritic, all categorially alike heads in its complement domain have to bear ⌃ as well. Thus, FOFC disallows head-final verbal heads (which bear ⌃) to combine with head-initial complementizers (which lack ⌃).

To comply with FOFC, Azeri ki-clauses have to extrapose. Such an extraposition can in principle be modeled in different ways. The literature on FOFC (Biberauer and Sheehan 2012; Biberauer et al. 2009a, 2009b) proposes that in order to comply with FOFC, head-initial clauses are forced to occur in a phonologically null nP layer, which breaks the domain of FOFC applicability. They adopt Kayne (1994)’s proposal that the linearization diacritic ⌃ triggers “roll up” (comp–to–spec) movement, and suggest that the null n triggers radical spellout that removes the embedded CP from the accessible derivation, and so the CP is spelled out in its base position.

Here I will not follow this implementation, as it requires ki-clauses to always surface in a nominal shell, and I will later suggest that ki-clauses vary in whether they are embedded in a nominal layer. In addition, Halpert and Griffith (2018) mention that there is some initial evidence that scrambling out of ki-clauses is impossible, suggesting that there might be Condition on Extraction Domain effects (Huang 1982), which would be unexpected if the clause remains in its base-generated position. Thus, I would like to suggest that extraposition of ki-clauses involves actual movement. If we assume that only copies of movement chains that will be pronounced have to be FOFC-compliant, then moving an embedded clause outside of the verbal domain and pronouncing the higher copy will be sufficient to avoid a FOFC violation. This is illustrated in (36).

Let us sum up our discussion of the syntax of ki-clauses. A prominent property of these clauses that makes them different from diy-clauses is that they are head initial embedded clauses in a head-final language. Such a switch in headedness is known to be impossible in natural languages (Final-Over-Final-Constraint). In order to be FOFC-compliant, ki-clauses then have to be extraposed. I have suggested that this extraposition involves real syntactic movement. If FOFC cares only about the copies that are pronounced, and thus undergo linearization, pronouncing the higher copy of the embedded clause should be sufficient for the structure to be FOFC-compliant.

- (36)

- FOFC triggers movement of the CP

Now let us turn to the factivity alternation that we observe with ki-clauses (first noticed in Lee (2019)). Consider the sentences with the factivity-alternating verbs in (3).

- (37) a.

- Leyla bil-ir /xatırla-yır [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla know-prs /remember-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla knows/remembers that Ömer stole the car.’

- b.

- Leyla elə bil-ir /xatırla-yır [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla ela know-prs /remember-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla thinks/remembers that Ömer stole the car.’

- c.

- …amma bu elə deyil. ✘ after (3a), ✓ after (3b)but this ela be.neg.prs (regardless of the prosody)‘…but this is not so.’

In (37a) only the factive reading is available: we necessarily infer from this sentence that Ömer stole the car, and there is no possible placement of pitch accents in (37a) that would result in a non-factive reading. The continuation in (37c) in this case is bad. In (37b) we see that adding the particle elə ‘so’ before the verb influences the factivity: such a sentence is compatible with Ömer not stealing the car, hence the felicity of the continuation in (37c) (cf. (Abrusán 2011, p. 517) on Hungarian úgy ‘so’).

Consistently non-factive verbs like fikirləşmək ‘think’ remain non-factive when they combine with ki-clauses, independently of whether they combine with the particle elə ‘so’:11

- (38)

- Leyla (elə) fikirləş-ir [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb], amma elə deyil.Leyla (ela) think-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p but ela be.neg.prsÖmər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb.Ömer car-acc steal-neg-p‘Leyla thinks that Ömer stole the car, but this is not so. Ömer didn’t steal the car.’

Thus, we see that without elə ‘so’, verbs like fikirləşmək ‘think’ are non-factive with ki-clauses, but verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ become obligatorily factive (Table 2). The latter two verbs can regain their non-factivity if elə ‘so’ is used.

Table 2.

Factivity in ki-clauses without elə ‘so’.

Before we turn to the discussion of elə ‘so’ in more detail, let us evaluate the two approaches discussed above with respect to the data we’ve seen so far. Both approaches can account for the prosodically conditioned alternation with diy-clauses, and teasing them apart based on the alternation observed with these clauses is very difficult, as it is very hard to distinguish a neutral context that leads to the default stress pattern from a context with an implicit Question Under Discussion due the availability of accommodation.1213 The two approaches however differ when it comes to ki-clauses.

The behavior of verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ with ki-clauses is unexpected on the pragmatic approach. It should be sufficient to not have focus marking (or perhaps verum focus marking) on the attitude verb in order to get the non-factive reading. It is not obvious why syntactic movement of the embedded clause should affect the possibility of focus marking, and the subsequent activation of alternatives. It seems that the pragmatic approach would need to say something additional about the syntax–prosody mapping and its relationship to semantics to explain why (37a) has to be factive. One could ask whether it is possible to incorporate the ideas about stress assignment from (Özyıldız 2017b; Kahnemuyipour 2009) to help out the pragmatic approach. For example, if we assume that the movement of the embedded clause leaves the verb alone in the stress domain, and so the verb must receive the nuclear pitch accent, could that make us activate the needed set of alternatives {V,¬V} and derive the factive inference? I’m afraid that this is not a legitimate move to make. We do not want to say whenever a phrase receives the nuclear pitch accent due to the rules of default accenting, we activate alternatives to this phrase. If that was so, we could never utter sentences in out-of-the-blue contexts. For example, the sentence from Turkish in (25), repeated below as (39), could then only be uttered in a context in which it is presupposed that Ali’s friend goes somewhere in the mornings.

- (39)

- [[ ] [[ ] [ ]]]((Ali’nin arkadaşı) (sabahları) (okula gider))Ali’s friend mornings to school goes‘Ali’s friend goes to school in the mornings.’

Thus, it is unclear how to implement the relationship between the movement of the embedded clause and presence of the factive inference on this approach, as evoking alternatives seems to be neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for creating factive inferences in sentences with ki-clauses.

The structural approach can attempt to account for the obligatory factivity of bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ with ki-clauses in the following way. Since clausal movement on this approach happens when the embedded clause is the complement of FP, and FP results in the factive reading of the sentence, we expect sentences in which clauses obligatorily move to always be factive. An underlying assumption that this approach has to make in order to pursue this explanation is that FP is necessary for clausal movement: it is not possible to move a bare CP just to satisfy FOFC, but still have a non-factive LF. This assumption turns out to be problematic when we consider ki-clauses that combine with fikirləşmək ‘think’: with them the clauses have to obligatorily move in syntax as well, but the interpretation of the sentence is nevertheless non-factive. Thus, the structural approach needs to say something additional about the difference between fikirləşmək ‘think’ on the one hand, and bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ on the other hand: there needs to be some difference between these verbs that requires the CP movement with the latter verbs to be semantically meaningful, but requires the CP movement with fikirləşmək ‘think’ to be semantically vacuous.

3.3. The Particle elə

The particle elə ‘so, in that way’ in Azeri is used not only in sentences with attitude verbs. It is a particle associated with the distal deixis which for example can be used to refer to a contextually salient property of an event, (40).14

- (40)

- Context: Leyla is dancing in a funny way. Hasan points at her and says:Fatimə elə rəqs ed-ir.Fatima ela dance do-prs‘Fatima dances in that way (= in the same way that Leyla is dancing)’

It can also be used anaphorically, and pick out a previously mentioned property:

- (41) Fatima:

- Leyla çox hündürə tullan-dı!Leyla very high jump-pst‘Leyla jumped very high!’

- Hasan:

- Hə, Leyla elə tullan-dı.yes Leyla ela jump-pst‘Yes, Leyla jumped in that way (= very high).’

I would like to suggest that such uses of elə ‘so’ suggest that it can be a pronominal expression that denotes a property of situations (type <s,t>).

The particle elə ‘so’ can occur with any attitude verb in its anaphoric guise. When it does so, there is no difference to the factivity of the sentence compared to when elə ‘so’ is absent. For example, consider (42) with a nominalized diy-clause and the non-factive fikirləşmək ‘think’.

- (42)

- Context: Someone says: “So we think that Ömer stole the car. I don’t know what Leyla thinks about this.” The other person responds:Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] elə fikirləş-ir.Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc ela think-prs‘Leyla thinks (in the same way) that Ömer stole the car.’

In (42) elə ‘so’ refers back to the proposition previously uttered by another participant in the conversation. It signals that the opinion that Leyla has is the same as the previously mentioned proposition “Ömer stole the car.” This use of elə ‘so’ is possible in factive sentences too, for example it is compatible with factive readings of diy-clauses with verbs bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ in addition to the non-factive ones, (43).

- (43)

- Context: We know that Ömer stole the car. Someone says to the speaker: “Don’t tell Leyla that Ömer stole the car!”, and they reply:Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] elə bil-ir /xatırla-yır.Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-dig-3-acc ela know-prs /remember-prs‘Leyla already knows /remembers that Ömer stole the car.’

If we update our table for factivity in diy-clauses with the information about elə ‘so’, we get what we see in Table 3: presence of elə ‘so’ seems to play no role for the presence of the factive inference in such cases, it just indicates that there is some salient proposition in the context that is identical to the content of the attitudinal eventuality.15

Table 3.

Factivity in diy-clauses with(out) elə ‘so’.

Now let us consider again sentences with ki-clauses. They can have anaphoric interpretations of elə ‘so’ as well, and so the whole empirical picture is as is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Factivity in ki-clauses with(out) elə ‘so’.

With the verb fikirləşmək ‘think’, this particle can have only anaphoric uses: for example, it’s good in a context where someone else previously expressed an opinion that Ömer stole the car, as is illustrated in (44).16

- (44)

- Context: Someone says: “So we think that Ömer stole the car. I don’t know what Leyla thinks about this.” The other person responds:Leyla elə fikirləş-ir [(ki) Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb], amma elə deyil.Leyla ela think-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p but ela be.neg.prsÖmər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb.Ömer car-acc steal-neg-p‘Leyla thinks that Ömer stole the car, but this is not so. Ömer didn’t steal the car.’

With verbs bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ on the other hand, elə ‘so’ seems to lead a double life: it can have a factivity-eliminating role in addition to the anaphoric role. Recall that without elə, these verbs are obligatorily factive with ki-clauses:

- (45)

- #Leyla bil-ir /xatırla-yır [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb], amma (bu)Leyla know-prs /remember-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p but (this)elə deyil. Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb.ela be.neg.prs Ömer car-acc steal-neg-pIntended: ‘Leyla thinks/remembers that Ömer stole the car, but this is not so. Ömer didn’t steal the car.’17

Adding the particle elə ‘so’ in an out-of-the-blue context gives rise to a non-factive reading:

- (46)

- Leyla elə bil-ir /xatırla-yır [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb], amma eləLeyla ela know-prs /remember-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p but eladeyil. Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-ma-yıb.be.neg.prs Ömer car-acc steal-neg-p‘Leyla thinks/remembers that Ömer stole the car, but this is not so. Ö. didn’t steal the car.’

But sentences that contain factivity-alternating verbs, the particle elə ‘so’, and ki-clauses are also compatible with factive contexts, and in such cases elə ‘so’ seems to refer back to some contextually salient proposition. For example, consider (47).

- (47)

- Context: Hasan and Fatima got married. They are going through their phonebook to see which of their friends they should call and tell the news.

- Hasan:

- Leyla bil-ir ki biz evlənmişik.Leyla know-prs ki we got.married‘Leyla knows that we got married.’

- Fatima:

- Ömər də elə bil-ir ki biz evlənmişik.Ömer also ela know-prs ki we got.married‘Ömer also knows (lit. ‘knows in this way’) that we got married.’

- Comment from the consultant: “elə ‘so’ is strengthening “also”, says that Ömer knows the same thing.”

In (47) the embedded clause in Fatima’s sentence is presupposed to be true, but the use of elə ‘so’ is felicitous, because Hasan just mentioned the embedded proposition. Similarly, in (48) we see that xatırlamaq ‘remember’ can be used in a factive context with elə ‘so’ and a ki-clause, provided that the embedded proposition is salient in the context.18

- (48)

- Context: Hasan and Fatima know that Ömer stole the car, they saw him on the cameras. Now they have to talk to witnesses who remember this happening.

- Hasan:

- Leyla-yla danış-aq?Leyla-with talk-opt‘Should we talk to Leyla?’

- Fatima:

- Leyla elə xatırla-yır [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla ela remember-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla remembers (lit. ‘remembers in this way’) that Ömer stole the car.’

To sum up, we have seen that the particle elə ‘so’ can function as a pronominal expression that refers back to some salient property of a situation. When it combines with attitude verbs, it can always have an anaphoric interpretation (“the content of this attitude is the same as some salient proposition p”), and in this case it does not affect the factivity of the sentence. The verbs bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ are interesting in that with them elə ‘so’ can also have a different use: it can indicate the elimination of the factive inference that is normally present when these verbs combine with ki-clauses, and in this case it does not place any restrictions on the context.

Thus, these data raise the question: why can elə ‘so’ eliminate the obligatory factive inference with the verbs bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ when they combine with ki-clauses? Why does elə ‘so’ have these special uses only with these verbs?

4. Proposal

I propose that (Özyıldız)’s general idea that factive inferences can emerge due to Quantifier Raising (QR) of the embedded clause is on the right track: when a clause QRs and takes wide scope, we get factive inferences, but when it scopes low, non-factive readings emerge. My implementation of this idea will have a few departures from the proposal in (Özyıldız 2017b, 2018), which will be necessary to account for the factivity alternation with ki-clauses in addition to the prosodically-conditioned factivity alternation with nominalized clauses.

I will assume that both diy-clauses and ki-clauses denote propositions: sets of situations in which the embedded proposition is true, (49).19

- (49)

- 〚Ömərin maşını oğurladığını = 〚ki Ömər maşını oğurlayıb =s’. Ömer stole the car in s’.

I will further assume that the domain of situations is a subdomain of the domain of individuals (D⊂ D), and that embedded clauses can combine with a null existential quantifier, (50), in which case they become QPs, (51), which have to undergo QR.

- (50)

- 〚 = f.k. ∃x[x ⊑ s ∧ f(x) ∧ k(x)]

- (51)

- 〚QP = k. ∃s’[s’ ⊑ s ∧ Ömer stole the car in s’ ∧ k(s’)]

I propose that the core difference between factive and non-factive readings comes from a distinction in the argument structure of sentences with factivity-alternating verbs (cf. proposals in Bondarenko 2020, 2022a)). I assume a neo-Davidsonian approach to argument structure (Castaneda 1967, a.o.), according to which the verbal roots themselves take no arguments besides the situation argument, (52), and all the arguments they combine with have to be introduced by functional argument-introducing heads.

- (52)

- 〚xatırla = s’. s’ ⊑ s ∧ remember(s’)

I propose that verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ can combine with two such functional projections: , (53), and , (54).

- (53)

- 〚 = p.x.s’. p(s’) ∧ Theme(s’)=x

- (54)

- 〚 = p.q.s’. p(s’) ∧ Cont(s’)=q

Note a difference in the type of the second argument of these heads: whereas wants to combine with an individual (which could be a situation), wants to combine with a set of situations. This difference has the following consequence: when the verb combines with , it will take a QP containing a CP inside of it, but when the verb combines with , it will take a bare CP. The reverse combinations will result in type mismatches. If the verb takes a QP, the QP will undergo QR, and its trace will saturate the ’s second argument. If it takes a bare CP, such a CP is not a scope-taker, and thus it will not QR: if a bare CP moves, it will have to be sematically reconstructed (Cresti 1995; Rullmann 1995) into its base generated position. This is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Two paths of clausal embedding.

In what follows, I argue that the structure with the clause combining via the head produces a factive inference as an entailment, and the structure with the clause combining via the head does not give rise to a factive inference.

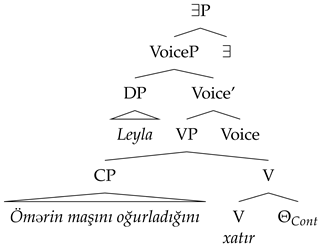

4.1. High Scope & the Factive Reading

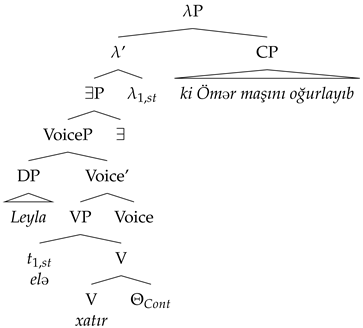

I propose that sentences with factive inferences like in (55) and (56) have the LF in (57) (it is achieved by string-vacuous movement in (55), and by observable movement in (56)).20

- (55)

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] xatırla-yır.Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc remember-prs‘Leyla remembers that Ömer stole the car.’⇝ Ömer stole the car.

- (56)

- Leyla xatırla-yır [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla remember-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla remembers that Ömer stole the car.’⇝ Ömer stole the car.

- (57)

- LF for (55) and (56)

Since in (57) the verb combines with , it won’t be able to combine with a bare CP: a predicate-denoting clause won’t be able to saturate the individual argument.21 But the verb can combine with a QP that has the CP as its restrictor. -abstraction that appears due to QR will apply to the constituent ∃P, which has the denotation in (58).

- (58)

- 〚∃P = 1 iff ∃s’[s’ ⊑ s ∧ remember(s’) ∧Exp(s’)=Leyla ∧Theme(s’)=]

It denotes “true” iff there is a situation s’ which is part of the situation of evaluation s, and s’ is a remembering situation with Leyla as the Experiencer, and the individual that the assignment function g returns when applied to index 1 as the Theme. After the Predicate Abstraction applies, and the QP is merged, we get the truth-conditions in (59).

- (59)

- 〚P = 1 iff ∃s”[s” ⊑ s ∧ Ömer stole the car in s” ∧∃s’[s’ ⊑ s ∧ remember(s’) ∧Exp(s’)=Leyla ∧ Theme(s’)=s”]]

The sentence will be true if there is a situation, which is part of the evaluation situation s, in which Ömer stole the car, and Leyla remembers this situation. Note that these truth-conditions entail that Ömer stole the car: because we’ve assumed that the meaning of the existential quantifier asserts existence of an individual in the situation of evaluation, (50), when an existential quantifier takes a proposition as its restrictor, it asserts that a situation of the kind described by this proposition exists in the situation of evaluation.

Note that the truth-conditions that we derive are those of an epistemically neutral report: the complement clause is transparent, and the embedded proposition is not evaluated in the situations compatible with beliefs of the attitude holder. All that (59) says is that Leyla stands in a remembering relation to a situation that is a situation of Ömer stealing the car in the actual world. An anonymous reviewer asks if this is in fact a desirable prediction. We can show that the beliefs of the attitude holder indeed do not have to be described by the embedded proposition. This is illustrated in (60a) for the diy-clauses and in (60b) for the ki-clauses.22

- (60)

- Context: Leyla sees a man getting into the car and driving away. She thinks this was Hasan getting into his own car and driving away. But in fact, this was Ömer stealing Hasan’s car.

- a.

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-dığ-ı-nı] xatırla-yır /bil-ir, ammaLeyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc remember-prs /know-prs buto elə bilir ki, maşın-la ged-ən həsən idi.3sg ela know ki car-by go-part Hasan was‘Leyla remembers/knows (the situation of) Ömer’s stealing of the car, but she thinks that it was Hasan going in the car’.

- b.

- Leyla xatırla-yır /bil-ir [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb], amma oLeyla remember-prs /know-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p but 3sgelə bilir ki, maşın-la ged-ən həsən idi.ela know ki car-by go-part Hasan was‘Leyla remembers/knows (the situation of) Ömer’s stealing of the car, but she thinks that it was Hasan going in the car’.

The embedded CPs in (60a) and (60b) are interpreted completely transparently: they contradict the beliefs of the attitude holder and just describe the situation in the world of evaluation. I take the fact that such interpretations are possible as evidence that we don’t need to introduce opacity into the semantics of these sentences,23 and factivity can be viewed as a consequence of transparent clauses scoping high (cf. Bondarenko 2020 and Bondarenko 2022b for similar proposals about factivity inferences in Buryat and in Russian).

Thus, a sentence with a quantificational clause will have the factive inference as its entailment. If we want to derive the factive inference as the presupposition of the sentence rather than entailment, we could demand that the introduces a presupposition about the argument that it introduces in the environment of certain verbal roots. As I will discuss in Section 5, bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ might warrant different treatment in this regard, as they show different projection behavior.

I follow (Özyıldız 2017b) in his account for how the movement of the embedded clause relates to the prosodic difference: in (57) the clause moves out of the stress domain, and thus the main stress has to be realized on the verb. The only difference between diy-clauses and ki-clauses is that for the latter there is no parse of a sentence where the clause would be in the same stress domain as the verb, as it is linearized not in the same phrase in which the verb is pronounced. Thus, the verb will always bear the main stress within its own domain in sentences with ki-clauses, unless we introduce some additional material that would remain within vP.24 Putting stress on the elements within the embedded clause will not affect the reading that we will get, as it is the movement of the clause that gives rise to the factive reading, not focus placement on the attitude verb. Note that the fact that putting prominence on the attitude verb is not necessary for creating factive inferences with ki-clauses suggests that even if focus alternatives can sometimes lead to factivity, as claimed by the pragmatic approach, it cannot be the only way of creating factive inferences.

4.2. Low Scope & the Non-Factive Reading In Situ

I propose that non-factive sentences with diy-clauses as in (61) have the LF in (62).

- (61)

- Leyla [Ömər-in maşın-ı oğurla-d̆ig-i-ni] xatırla-yır.Leyla Ömer-gen car-acc steal-diy-3-acc remember-prs‘Leyla remembers that Ömer stole the car.’Ömer stole the car.

- (62)

- LF for (61)

In (62) the verb combines with , this head introduces the propositional content associated with the eventuality described by the verb (cf. Kratzer 2006; Moulton 2009, 2015; Bogal-Allbritten 2016; Kratzer 2016; Elliott 2020, a.o.). Since this head requires a proposition as its second argument, only a bare CP will be able to combine with it, and we will get the truth-conditions for the sentence presented in (63).

- (63)

- 〚∃P = 1 iff∃s’[s’ ⊑ s ∧ remember(s’) ∧Exp(s’)=Leyla ∧ Cont(s’)={s: Ömer stole the car in s}]

It will be true iff there is a situation s’ in the situation of evaluation which is a situation of remembering by Leyla, and the propositional content associated with this situation s’ is the set of situations in which Ömer stole the car. Note that the head introduces displacement: it says that the embedded proposition is the content of a situation s’ that exists in the situation of evaluation. From this we cannot infer anything about whether there is a situation in the situation of evaluation of which the embedded proposition is true. Thus, the factive inference will not arise with the LF in (62).

Regarding the prosody of these sentences, the analysis in (Özyıldız 2017b), which I adopt, makes the right predictions. In (62), the embedded clause is inside the VP, and so it remains within the same stress domain as the verb. Since the CP is the highest XP within the stress domain, the main sentence stress will fall within it, which is what we observe.25

A question that arises at this point is: what would happen if we moved this clause outside of the VP? Note that this movement would have to be semantically vacuous. Recall that our clause is a predicate of situations, and this is exactly the type of argument that wants. Thus, in order for the derivation to converge, a diy-clause that would move would have to reconstruct into its base generated position: i.e., the movement operation would need to be completely undone as far as the semantics is concerned, either by syntactic reconstruction (Barrs 1986; Chomsky 1993, a.o.) or by semantic reconstruction (Cresti 1995; Rullmann 1995, a.o.). I would like to suggest that due to economy considerations (cf. Scope Economy in Fox 1995), diy-clauses in structures like (62) do not undergo movement: since there is no syntactic reason for them to move, and the movement would not yield a distinct semantic interpretation, they always remain in situ.26

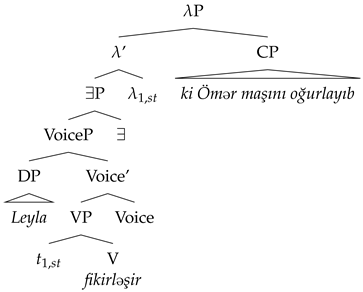

4.3. Low Scope & the Non-Factive Reading via Reconstruction

Finally, let us consider how elə can eliminate factivity with verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’. I propose that non-factive sentences like (64) have LFs like in (65). In this structure the verb combines with the head, and the resulting verbal head thus directly takes an embedded clause as its argument. While semantically this clause has to be interpreted in its base-generation position, in order to comply with FOFC, the CP has to vacate the verbal phrase. The syntactic movement of the clause satisfies the linearization requirement, but the clause then has to leave a higher type trace and reconstruct into its initial position for the structure to be interpreted. I propose that elə is the morphological exponence of the lower copy of the CP when it is interpreted as a higher-type trace, (66).

- (64)

- Leyla elə xatırla-yır [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla ela know-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla remembers that Ömer stole the car.’Ömer stole the car.

- (65)

- LF for (64)

- (66)

- 〚elə =

Once we perform the Predicate Abstraction in (65), we will get the denotation for the node ’ in (67): it will be a set of propositions p such that Leyla has a remembering state with the propositional content p. Then the clause saturates p, resulting in (68).

- (67)

- 〚’ = p.∃s’[s’ ⊑ s ∧ remember(s’) ∧Exp(s’)=Leyla ∧ Cont(s’)=p]

- (68)

- 〚P = 1 iff∃s’[s’ ⊑ s ∧ remember(s’) ∧Exp(s’)=Leyla ∧ Cont(s’)={s: Ömer stole the car in s}]

The sentence will be true iff there is a remembering state by Leyla with the content “Ömer stole the car”. Thus, we have arrived at the same non-factive reading that we got with diy-clauses. The only difference is that since ki-clauses had to undergo overt movement to comply with FOFC, reconstructing them to their base position was required. Note there is no way for a sentence with a ki-clause but without elə to receive a non-factive interpretation: ki-clauses can’t stay in situ due to FOFC, and if they were encapsulated in a QP and left an e-type trace, we would get a factive reading. The only path to the non-factive reading is to move a bare ki-clause that leaves an <s,t>-type trace, but that trace is then pronounced as elə.

Just as in other sentences with ki-clauses, on this account we do not expect prosodic manipulations to matter for the presence of factive inferences in these sentences: the embedded clause and the verbal phrase do not form a single prosodic domain, and the default main stress will be calculated within the VP and within the CP separately. Note that the pragmatic approach faces a problem when it comes to ki-clauses in sentences with elə: it cannot explain why such sentences don’t get factive readings even if we try to put prominence on the attitude verb.

I would like to suggest that the denotation in (66) is a plausible meaning for anaphoric uses of elə as well. In those cases, elə would denote a free pronoun that receives its interpretation from the assignment function g. Given its type, elə could combine with any verbal projection that denotes a predicate of situations by Predicate Modification and restrict the predicate to situations of which the contextually salient property is also true. For concreteness, we can assume that such anaphoric elə adjoins to the VP.

An anonymous reviewer asks whether an alternative analysis of sentences with elə is possible: could it be that elə saturates the argument position of the verb, and the clause is an unselected adjunct similar to the Japanese and Korean quotative CPs discussed in the literature (Kim 2018; Goodhue and Shimoyama 2022)? I would like to suggest that such an alternative proposal is untenable. First, even though ki-clauses have a use as purpose adjuncts (see Note 9), they do not seem to generally permit unselected readings where the clause would describe the mental state of the attitude holder, (69).

- (69)

- nənə-m mən-ə pul ver-digrandmother-1sg 1sg-dat money give-pstçünki /??ki mən çox oxu-muş-am.because /ki 1sg.nom a.lot study-perf-1sg‘My grandmother gave me money {because/ thinking that} I studied hard.’Comment about the ki-clause: “something is missing here, ‘because’ is missing.”

Second, if ki-clauses were able to have unselected uses, which would be the source of non-factive interpretations, we might expect them to be able to have the same uses in the absence of elə, falsely predicting ki-clauses without elə to be ambiguous between the factive (selected) and non-factive (unselected) interpretations.

Third, ki-clauses in sentences with the particle elə are just like ki-clauses in sentences without the particle in passing the diagnostics for being in the c-command domain of the matrix verb; they differ in this respect from adjunct clauses (Halpert and Griffith 2018). For example, in (70) we see that a quantificational subject can bind a pronoun in a ki-clause in a sentence with elə, and in (71) we see that ancaq ‘only’ can focus-associate with a DP inside of the ki-clause in a sentence with elə. These data would be unexpected if ki-clauses were unselected adjuncts that were not base-generated as complements to verbs.27

- (70)

- [hər tələbə] elə bil-ir [ki pro test-dən keç-ib]. (bound reading ok)every student ela know-prs ki test-abl pass-p‘Every student thinks that they passed the test.’

- (71)

- Leyla ancaq elə bil-ir [ki Həsən Bakı-ya ged-ib].Leyla only ela know-prs ki Hasan Baku-dat go-p‘Leyla only thinks that Hasan went to baku.’(She doesn’t think he went to Istanbul, She doesn’t think he went to London, etc.)

Thus, I conclude that elə is never a Theme argument of the verb.28 There is however another proform element in Azeri which might conform better to the suggested analysis: a third person pronominal o ‘(s)he, it’, which also can co-occur with ki-clauses. Interestingly, in these cases only the factive interpretation is available (see Sudhoff 2003; Frey et al. 2016 for similar observations about German es). While this construction requires more research, one way to analyze it within the approach pursued in this paper is to say that the pronominal o ‘(s)he, it’ can be the spell-out of an e-type trace of the QP-encapsulated ki-clause that was base-generated as the Theme argument. I.e., the structure for (72) could be the same that we postulated in (57) for other factive sentences, with the only difference being that the trace from the moved clause is overtly realized in (72) as o-nu.

- (72)

- (#Həsən Istanbul-da-dır, amma) Leyla o-nu bil-ir ki, Həsən Bakı-ya(Hasan Istanbul-loc-is but) Leyla 3sg-acc know-prs ki Hasan Baku-datged-ib.go-p‘(#Hasan is in Istanbul, but) Leyla knows that Hasan went to Baku.’

4.4. Verbs That Are Never Factive

Recall that one challenge that the structural approach faces is the need to distinguish verbs like fikirləşmək ‘think’ from verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’. If our explanation of factivity alternations relies on clausal movement resulting in a factive LF, we need to say something additional to explain how verbs like fikirləşmək ‘think’ exhibit overt clausal movement in sentences with ki-clauses but nevertheless receive non-factive readings, (73).

- (73)

- Leyla fikirləş-ir [ki Ömər maşın-ı oğurla-yıb].Leyla think-prs ki Ömer car-acc steal-p‘Leyla thinks that Ömer stole the car.’Ömer stole the car.

I propose that the difference between factivity-alternating verbs and fikirləşmək ‘think’ lies in the argument structure, and suggest that sentences like (73) have LFs like in (74).

- (74)

- LF for (73)

I would like to suggest that what is unique about fikirləşmək ‘think’ is that it does not combine with any functional argument-introducing heads, but instead it actually takes the embedded proposition as its true argument, (75).

- (75)

- 〚fikirləş = p.s’. s’ ⊑ s ∧ think(s’) ∧(s’)=p

Since it selects for a proposition that is its propositional content, will not be needed. And I assume that eventualities that fikirləş is true of do not have Theme arguments.29

Thus, for a sentence with the verb fikirləşmək ‘think’ and a ki-clause, the LF that leads to factivity (LF with a QP-encapsulated clause that is the Theme argument) is not possible: the verb just does not combine with the functional head that is needed for such an LF, as fikirləşmək-eventulatities have no Themes. Embedded clauses that combine with this verb must still observe FOFC, so when fikirləşmək combines with a ki-clause, such a clause will have to undergo overt movement. Given the argument structure of fikirləşmək ‘think’, the moved ki-clause will have no other choice but to reconstruct in order for the semantic interpretation to successfully compose.

The remaining puzzle that we have is this: why does the higher-type trace that we get as the lower copy of the ki-clause with fikirləşmək ‘think’ remain silent? Why is it not exponed with elə, like the higher-type trace in sentences with factivity-alternating verbs? While I do not have a very satisfying answer to this question, we can capture this difference under my proposal by an allomorphy rule, as the higher-type trace in the LFs in (74) and (65) is inserted into a slightly different environment. I provide a possible rule in (76).

- (76)

- For any index i:t ⇔ elə /___ V+⌀ /___ otherwise

When the trace of this type occurs in the context of a complex V+ head, it is exponed as elə, otherwise it is left unpronounced. This will account for the examples with fikirləşmək like (73), where we get a non-factive reading by semantic reconstruction, but do not see elə. A functional explanation behind such a difference in exponence might be that sentences with fikirləşmək correspond unambiguously to an LF with a <s,t> type CP, but sentences with factivity-alternating verbs and ki-clauses are ambiguous between a clause that left an e type trace and a clause that left an <s,t>-type trace. Under the assumption that type e is the default type of traces (cf. Ruys 2011, 2015), a special marking might be required to signal that the clause has left a non-default <s,t>-type trace behind.

5. Differences in Projection: bil- vs. xatırla-

The anlaysis presented above derives the factive inference with verbs bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ as an entailment, which arises due to the existential inference introduced by a quantifier that there is situation of the kind described by the embedded clause in the situation of evaluation. In order to determine whether this inference is not just an entailment, but a presupposition, we need to see how it projects from entailment-canceling operators. Here I show that when we embed bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ in questions and in antecedents of conditionals, they do not behave the same.

The difference lies in what has to (not) be present in the common ground to felicitously utter the sentence. Both verbs require that the common ground does not contradict the embedded proposition. This is shown in (77) with a question and in (78) with a conditional.

- (77)

- Context: There was a competition and we know that Fatima lost it (e.g., Zahra is the winner). Hasan was drunk during the competition and I suspect he does not remember what was happening. I suspect he confused Zahra with Fatima.#Həsən bil-ir /xatırlay-ır ki Fatimə yarışma-nı udu-b?Hasan know-prs /remember-prs ki Fatima competition-acc swallow-pIntended: ‘Does Hasan think/remember that Fatima won the competition?’

- (78)

- Context: Ömer didn’t rob the bank, but he is being suspected. Hasan and Fatima are Ömer’s lawyers who are trying to decide how to make sure that the innocent Ömer doesn’t go to jail. They know that a big gun is a key piece of evidence in the investigation and that Ömer doesn’t own a big gun. Leyla is a policewoman working on the robbery case, who hates Ömer and wants to put him in jail.

- Hasan:

- səncə Ömər şəhəri tərk etməlidir?you-ptcl Ömer city out.of do.should‘Do you think Ömer should leave the city?’

- Fatima:

- #əgər Leyla bil-ir-sə /xatırlay-ır-sa ki Ömər-inif Leyla know-prs-cond /remember-prs-cond ki Ömer-genböyük silah-ı var, onda Ömər getməlidir.big gun-acc has then Ömer go.should‘If Leyla thinks/remembers that Ö. has a big gun, he should leave the city.’

If it is common ground that (Fatima lost the competition, Ömer doesn’t own a big gun), then one cannot ask a question of the form Subject bilmək /xatırlamaq p?. One can also not felicitously utter conditionals with antecendents of the form if bilmək /xatırlamaq p. This behavior is expected if the factive inference projects.

If the factive inference has to project, we also expect that it should not be possible to utter such sentences in contexts where common ground is undecided with respect to the truth of p: if something is a presupposition, it imposes a requirement that p has to be true throughout the context set. In this respect however, the two verbs behave differently. In contexts where the truth of p is not known to the speech act participants, bilmək p is infelicitous, but xatırlamaq p is felicitous.30 This is illustrated with a question in (79) and with a conditional in (80).

- (79)

- Context: There was a competition and there is disagreement as to who won it. We weren’t there and don’t know who won, but we are trying to decide whose opinion is correct. People who were at the contest have left their opinions written down. I am interested in how Hasan remembers the competition.

- a.

- #Həsən bil-ir ki Fatimə yarışma-nı udu-b?Hasan know-prs ki Fatima competition-acc swallow-pIntended: ‘Does Hasan think that Fatima won the competition?’

- b.

- Həsən xatırlay-ır ki Fatimə yarışma-nı udu-b?Hasan remember-prs ki Fatima competition-acc swallow-p‘Does Hasan remember that Fatima won the competition?’

- (80)

- Context: Ömer is being suspected in robbing a bank. Hasan and Fatima are Ömer’s lawyers and they don’t know if Ömer actually did the robbery but are trying to defend him. They know that a big gun is a key piece of evidence in the investigation. They don’t know if Ömer has a big gun. Leyla is a policewoman working on the robbery case, who hates Ömer and wants to put him in jail.

- Hasan:

- səncə Ömər şəhəri tərk etməlidir?you-ptcl Ömer city out.of do.should‘Do you think Ömer should leave the city?’

- Fatima:

- əgər Leyla #bil-ir-sə /xatırlay-ır-sa ki Ömər-inif Leyla know-prs-cond /remember-prs-cond ki Ömer-genböyük silah-ı var, onda Ömər getməlidir.big gun-acc has then Ömer go.should‘If Leyla thinks/remembers that Ö. has a big gun, he should leave the city.’

Thus, with bilmək ‘think/know’ we could encode the factive inference as a presupposition, e.g., by requiring that this verb wants a definite description as its Theme argument instead of an indefinite one, or by writing an allosemy rule (see Wood and Marantz 2017, a.o.) that introduces a presupposition about the individual argument introduced by in the context of the root bilmək (cf. Bondarenko 2020). But with xatırlamaq ‘remember’ encoding the factive inference as a presupposition would be too strong, as it does not require the embedded proposition to be true throughout the context set. So one hypothesis that we could entertain is that the Theme argument of xatırlamaq is just an indefinite which has to take exceptional scope. That indefinites can take exceptional scope has been observed in the literature (Fodor and Sag 1982; Charlow 2014, a.m.o.), for example the indefinite in (81) can take scope outside of the conditional, suggesting that there is a particular relative of the speaker, such that if that relative dies, they will inherit a condo.

- (81)

- If a wealthy relative of mine dies, I’ll inherit a condo. (Charlow 2014, p. 1)

So if a QR-ed clause with xatırlamaq is an indefinite that has to take exceptional scope, then even with entailment-canceling operators we will get the factive inference p as an entailment. Such an inference will not allow us to utter a sentence in a context where p is known to be false: asserting something that entails p when is known to be true should lead to infelicity. However if p is just an entailment, we should be able to utter it when the context is undecided with respect to p. This is exactly what we observed with xatırlamaq.

6. Conclusions

In this paper I have provided an argument in favor of the structural approach to factivity alternations based on factivity-alternating verbs like bilmək ‘think/know’ and xatırlamaq ‘remember’ in Azeri. We could have thought that pragmatic vs. structural explanations are both needed, but they are needed for different kinds of factivity alternations: the former is required for prosodically-conditioned alternations, the latter is required for alternations that arise due to differences in the syntax of clausal embedding. But data from Azeri makes one question this dichotomy: we see that the same verbs display both prosodically-conditioned alternations, and alternations related to structural distinctions (presence vs. absence of elə), and it is the syntax of the embedded clause that determines the choice between the two. This is difficult to account for under a purely pragmatic approach, which relies only on the placement of focus marking and the differences in lexical semantics of attitude verbs in its explanation of the alternation.

I argued that Özyıldız (2017b)’s idea that factive and non-factive LFs differ in the scope of the embedded clause can help us understand the two factivity alternations in Azeri. I proposed that whether a clause moves or not is related to the argument structure of the verb: QP-encapsulated CPs are Theme arguments of verbs, but bare CPs are Content arguments. The difference between diy-clauses and ki-clauses is that while the former can optionally move (factive reading, stress falls on the verb remaining in VP) or stay within VP (non-factive reading, stress falls within the clause), the latter have to move overtly in syntax in order to satisfy FOFC (Halpert and Griffith 2018). This means that they will always be outside of the domain of the stress assignment, accounting for the fact that manipulating prosody does not have an effect with ki-clauses. I proposed that due to the syntactic necessity of this movement, both QP-encapsulated and bare ki-clauses are allowed to move, but the two cases differ in how the lower copy will be pronounced: in the former case, where the clause leaves an e-type trace, the lower copy has null exponence, but in the latter case, where the clause leaves an <s,t>-type trace, its lower copy is exponed as elə ‘so’. Since under the proposed account the FOFC requirement of ki-clauses can be satisfied by two different types of movement (QR and bare CP extraposition), we might expect these movements to exhibit different syntactic properties—something that remains to be investigated in the future research.