Abstract

This article describes and discusses some properties of the distribution of Negative Concord Items (NCIs) in the Italo-Romance domain, taking into account both varieties of Italian and varieties of other Italo-Romance languages. More precisely, the authors examine non-negative contexts, which allow the presence of NCIs. Across all non-negative contexts, bare/pronominal NCIs are systematically allowed in more contexts than complex ones, modulo the behavior of the specific variety in relation to non-negative contexts. The phenomenon can be accounted for by assuming that the structure of complex and bare NCIs is different not only in terms of null versus lexically realized NPs. The authors argue that bare NCIs, and possibly other quantificational elements, are not paired with a null DP but with a reduced structure, i.e., a classifier-like element which contains no lexical N.

1. Introduction

In this work, we intend to analyze the distribution of Negative Concord Items (NCIs, labeled also as N-words in the literature; cf. Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017; Giannakidou 2020) in non-negative contexts across some old and modern Italo-Romance varieties.

The label NCI is used for those indefinites (pronouns, determiners and adverbs) that, in negative concord languages, appear in negative contexts. Usually these elements are obligatorily accompanied by the morphosyntactic marker of sentential negation in strict negative concord languages (like Romanian, Greek or all Slavic languages), while in non-strict negative concord languages (like Italian or Spanish) they are able to encode sentential negation by themselves when they surface in specific syntactic positions (usually above T(ense), i.e., the inflected verb; cf. Giannakidou 2000; Zeijlstra 2004). For instance, in Italian the subject nessuno ‘nobody’ requires the preverbal particle non when it is postverbal, while the presence of non is ungrammatical when the subject is preverbal (Non è arrivato nessuno/Nessuno (*non) è arrivato ‘Nobody arrived’). In some languages (e.g., in the whole Slavic group or in Albanian) NCIs can appear only in negative contexts, while in other languages, like Italian and Italo-Romance varieties, they are allowed also in other environments, where they correspond to simple existential expressions.1

We will show that the distribution of “non-negative” NCIs can be described, taking into consideration two fundamental variables:

- (a)

- The bare versus complex nature of the NCI, i.e., for instance, Italian nessuno/niente ‘nobody/nothing’ versus nessun X ‘no X’;

- (b)

- The type of non-veridical context (e.g., interrogative or conditional; see Giannakidou 2000 and subsequent works; Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017) in which the NCI occurs.

In particular, besides the canonical NCI environments, that is direct and indirect negation (like under the preposition ‘without’), we will concentrate on the following contexts, which are the ones where the NCIs can occur in Italo-Romance varieties: (a) polar interrogative clauses, (b) conditional if-clauses, (c) comparative structures (where the NCI appears in the comparative sub-clause), and (d) free relative clauses. Considering these contexts, we observe that all the varieties we investigate obey the same implicational hierarchy in precisely the order of the contexts listed above. For instance, if a variety allows the presence of an NCI in a conditional clause (e.g., in Italian Se vedi nessuno… ‘If you see anyone…’), then it will allow it in polar questions as well (Italian Hai visto nessuno? ‘Have you seen anyone?’).

At the same time, all varieties display sensitivity to the bare versus complex nature of the NCI, so that bare NCIs are much more prone to be accepted in domains that are different from a proper negative environment, while complex NCIs tend to be compatible with fewer environments. For instance, a variety that allows bare NCIs in conditional clauses and polar questions, allows complex NCIs only in polar questions. In these implicational terms, a similar difference between bare and complex NCIs has never been observed in the literature on NCIs2 and we will concentrate on its explanation.

Our main research question is: why is there a distinction in the distribution of NCIs that takes pronominal ones apart from complex ones? We will develop an analysis in terms of a different internal structural layering of the NCI itself. More precisely, we hypothesize that the internal structure of pronominal NCIs is different, and contains fewer projections than the one of complex NCIs. However, this will not be done in the sense of Cardinaletti and Starke (1999), as one might expect, but reversing their perspective in the sense that what bare NCIs lack is not a functional layer located on top of its structure, but rather the NCI-words are defective in the lower portion, i.e., what is missing is the lexical part. Hence, they are not deficient in their higher functional projections, but rather, and almost trivially so, in the fact that they lack the lower lexical portion, i.e., the NP.3 We will argue that bare NCIs are paired to a smaller internal structure only containing a classifier-like element of the sortal type (see Svenonius 2008) but no lexical NP projection. In this sense, our analysis goes against what has been standardly proposed in the literature (see among others, Doetjes 1997; Baunaz 2011), namely that bare quantifiers are paired with a pro. We propose that the pronominal NCIs only contain a classifier-like element because this is the most minimal category necessary for a nominal expression to be interpreted, and requires no lexical specification per se. On the contrary, the complex NCIs contain a fully-fledged nominal structure with a lexical NP and the corresponding functional projection in the IP/TP-analogue of the DP functional structure. This internal difference determines a different distribution of simple and complex NCIs, cutting across the different contexts we take into account. This idea could in principle be adapted to other types of quantificational elements, like existential and universal quantifiers (see Garzonio and Poletto 2018 on this), and even be extended to all types of pronouns, in particular to personal, possessive and wh-pronouns.

2. Materials and Methods

This article is based on two different types of linguistic data. For present-day varieties, the authors have used their respective native speaker competences of the regional Italian of Tuscany (JG) and the regional Italian of Veneto (CP) as a starting point, and then verified their judgements with ten other speakers for each variety. The selected speakers are all adults, equally distributed among gender and selected on the basis of their competence in the respective variety of regional Italian. All informants have always lived in Tuscany or Veneto. Each informant has provided an acceptability judgement (grammatical vs. ungrammatical) on four pairs of sentences, one with a bare NCI and one with a complex one for each of the four relevant contexts. The interviews were conducted in September and October 2023.

Regional varieties of Italian (cf. Cerruti 2011) are defined as geographically restricted variants of the standard language; they occupy the sociolinguistic space of the colloquial spoken language and are mastered by all the speakers native to a certain region. They are not to be confused with varieties usually labeled “Italian Dialects”, that are a different language originally derived not from any version of Italian, but directly from Latin. Dialects are used only in a familiar setting (either in the family or among friends), while regional standard varieties have a much broader diffusion across contexts and styles. Furthermore, not all speakers native of a certain region master the dialect as native speakers, but they all master the colloquial variant of Italian. While dialects are alive in the consciousness of the speakers, who know that they are speaking a different language, regional variants are often just perceived as the standard, although they actually have geographically confined phonological and syntactic properties. Even if the regional varieties of Italian and the so-called “Italian Dialects” have a different sociolinguistic position and a separate historical development, for the goals of this work they can all be considered as varieties of the Italo-Romance linguistic continuum, i.e., strictly related varieties, with very similar parametric patterns, where it is possible to conduct a micro-variational analysis.

Data from medieval Italo-Romance varieties are taken from the corpus of the Opera del Vocabolario Italiano database (http://www.ovi.cnr.it/Il-Corpus-Testuale.html, accessed on 1 October 2022), which contains more than 3000 texts (ca. 30 million words) and can be searched for text strings and lemmata specifying parameters like the author, the chronology, the type or the variety of the text.

We have restricted our investigation to Italo-Romance varieties because we intend to compare languages that are minimally different from each other, thereby keeping most factors as a constant and having only the distribution of the NCIs as the variable phenomenon. Hence, the choice of using a micro-variational methodology forcedly determines the narrowing down of the set of languages we investigate to a single homogeneous linguistic domain: we can only compare languages in which the morphological endowment of these elements remains stable and the general syntactic properties of the clausal and nominal structure are similar (amount of N and V raising, types of lexically realized functional features, agreement and concord, etc.); we do not think it would be fruitful to add the comparison with other totally different languages. This type of investigations is more and more used in comparative syntax and constitutes the counterpart of typological investigations.

We are aware of the fact that there are other possible non-veridical constructions in which weak NPIs can occur, but the ones we consider here are those that occur consistently in the sample of the languages we are working on.4

3. Previous Work on Quantificational Items

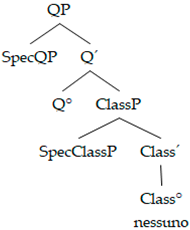

If we consider universal and existential quantifiers, which are in their internal syntactic layering the most similar candidate to NCIs, we observe that bare and complex quantifiers have been treated in the literature as having an identical internal structure. In other words, previous work has not detected any internal syntactic differences between complex QPs (Quantifier Phrases) and bare quantifiers, if we factor out the possibility of bare quantifiers being treated like clitics or weak elements mentioned in Cardinaletti and Starke (1999). The standard analysis of bare quantifiers (see among others Doetjes (1997), Baunaz (2011)) is that they are paired with a null category of the pro type, as the one reported in (1):

| (1) | a. | [QP Q [(DP) pro]] | pronominal Q |

| b. | [QP Q [(DP) (D) [NP N]]] | determiner-like Q | |

| Italian | |||

| c. | [QP tutto [(DP) pro]] | pronominal Q | |

| ‘Everything’ | |||

| d. | [QP tutti [DP i [NP ragazzi]]] | determiner-like Q | |

| ‘All the boys’ | |||

| e. | [QP nessun [(DP) [NP ragazzo]]] | determiner-like Q | |

| ‘No boy’ | |||

The first problem one encounters with such an account is that pro generally corresponds to a whole DP (Determiner Phrase) and pronouns are generally considered as D° elements, but not all quantifiers select for a whole DP. Actually, only universal quantifiers of the type Italian tutto ‘all’ tolerate a DP with a definite article as their complement, while all other quantifiers are in a complementary distribution with articles.5 Furthermore, as discussed by Garzonio and Poletto (2017), the internal etymological construal of many Italo-Romance bare quantifiers suggests that they are not simply monomorphemic, but are paired to a classifier-like element of the sortal type (see Svenonius 2008 for a discussion on different types of classifiers) in cases like somebody, something, sometime and to a classifier of the numeral type in cases like someone. Hence, in the account proposed in Garzonio and Poletto (2017), there is an asymmetry in the lower portion of the internal structure of quantifiers, so that the bare ones lack a regular NP but are only paired to the most minimal category necessary for quantification, namely a classifier. In this view, classifiers are seen as a sort of existential element which states that an entity of a specific class (objects, persons, places, times, etc.) exists and does not provide any information about further content properties, a function which is generally performed by the lexical noun itself:

| (2) | [QP Q [ClassP THING/PERSON/PLACE/TIME/WAY]] |

In (2), there is no lexical NP related to bare quantifiers, the only element present is the classifier, which singles out the “sort”, and is most probably a light noun similar to the ontological categories that Kayne (2005) first proposed and that have since become a standard way to analyze different types of nominal expressions containing null or lexical sortal classifiers. To prove that there is indeed a structural difference between the bare quantifiers and complex quantifier expressions, Garzonio and Poletto (2017) observe that the bare quantifiers are consistently located in front of the past participle in languages like Old Italian (OI), i.e., the Italo-Romance variety spoken in Florence in the second half of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century. This is not the case for complex quantified expressions, as shown by (3b):

| (3) | a. | (…) seguire | Idio | chi | à | tutto | venduto. | ||

| follow.Inf | God | who | has | everything | sold | ||||

| ‘(he can) follow God who sold all his possessions.’ (Fiore, 232) | |||||||||

| b. | à(n)no | ve(n)duto | tutto | i·loro | podere. | ||||

| have | sold | all | the their | land | |||||

| ‘they sold all their land.’ (Val di Streda, 226) | |||||||||

Similar effects have been found in other languages, like Cimbrian and modern French (see Grewendorf and Poletto 2005; Garzonio and Poletto 2018), with a further twist. Here, the distinction is not between the bare quantifiers and complex ones, but has to do with the lexicalization of the classifier portion, so that when the classifier is lexically empty, it is located in front of the past participle; when it is lexically realized, the quantifier appears in its regular in situ position:

| (4) | a. | J’ai | tout | vu/%J’ai | vu | tout. | |||

| I=have | all | seen | I=have | seen | all | ||||

| ‘I have seen everything.’ | |||||||||

| b. | J’ai | vu | tout | le monde/*J’ai | tout | le monde | vu. | ||

| I=have | seen | all | the world I=have | all | the world | seen | |||

| ‘I have seen everyone.’ | |||||||||

Furthermore, bare quantifiers in French cannot be paired with a preposition when they occur in front of the participle, while Old Italian allows these constructions. In general, these differences can be explained by assuming that only bare elements can be merged in the inflectional layer of the clause structure above vP. In what follows, we intend to show that the idea that there is a structural distinction between bare and complex quantifiers can be naturally extended to NCIs. We will show that the empirical evidence can be interpreted in terms of a split between the bare and complex NCIs, where pronominal ones have a different internal layering that results in a different distribution in the clause. Our starting point in favor of this conclusion is the detailed observation of the (micro-)variation across Italo-Romance regarding the non-veridical contexts allowing the presence of NCIs.

4. The Data

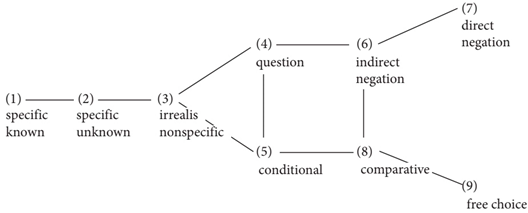

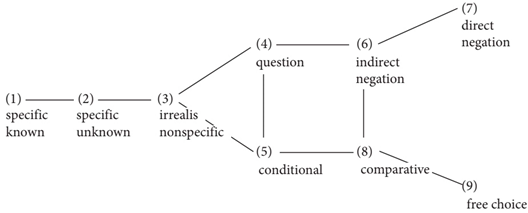

As mentioned above, we consider four types of syntactic environments where NCIs can be found outside the domain of negative clauses. Looking at Italo-Romance varieties, it is possible to establish an implicational scale which goes from yes/no interrogative clauses6, to if-clauses, to comparative, to free relative clauses.7 In what follows, we will consider one variety for each step of the implicational hierarchy. We are aware of the fact that similar data have been observed in the typological literature, and refer the reader back to Haspelmath’s (1997) conceptual map. However, the languages we are considering here do not require such a complex map, including various developmental paths, some of which are in an alternative distribution. We adopt here a much simpler one, which is the one we will be using for the sake of concreteness, ignoring the rest of the possibilities that are not relevant to the distribution of the bare and complex NCIs. Since Haspelmath’s conceptual map is based on very many different languages, we think it is appropriate to narrow down our focus to a single domain and show which part of this general semantic map can be used to describe the distribution of NCIs in Romance.

4.1. First Step: Southern Italian Dialects

In the Southern Italian dialects (SIDs) (we take here the Sicilian variety of Palermo as an exemplary point, but the facts are replicated also in other dialects in the ASIt database8), the NCIs are never freely available outside a negative environment. The SIDs are regular, non-strict, negative concord languages with a preverbal negative marker of the Latin etymological type non. None of the four additional environments considered here allow the presence of NCIs, either bare or complex ones. Very marginally, some speakers accept the interrogative context under the influence of Italian:

| (5) | a. | ??Viristi | a nuddu, | pi’ | ccasu? | |||||

| saw.2sg | to nobody | by | chance | |||||||

| ‘Have you seen anybody, by chance?’ | ||||||||||

| b | *?Abbisami | si | bbiri | a nuddu | ‘m piazza. | |||||

| warn=me | if | see.2sg | to nobody | in square | ||||||

| ‘Warn me if you see someone in the square.’ | ||||||||||

| c. | *È | a cuasa | chiù strana | ca | rissi | nuddu. | ||||

| is | the thing | more strange | that | said | nobody | |||||

| ‘It is the strangest thing that someone said.’ | ||||||||||

| d. | *Cu | vitti | a nuddu, | un | ddici | a virità. | ||||

| who | saw.3sg | to nobody | Neg | tells | the truth | |||||

| ‘Who has seen somebody is not telling the truth.’ | ||||||||||

These varieties constitute the grade zero of the implicational scale we are considering here, so that NCIs necessarily require a negative marker (or none, if they are in preverbal subject position or in preverbal focus position) to be licensed. No other types of non-veridical contexts are possible licensors for the NCIs. In all four contexts in (5), NCIs have to be substituted by an existential quantifier corresponding to ‘someone’. Hence, in the Southern Italian dialects, postverbal NCIs have the same distribution as strong NPIs in languages like English (see Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017).

4.2. Second Step: Veneto Italian

In the contemporary regional standard variant of Italian spoken in Veneto, the usage of NCIs outside negative domains is extremely restricted; they are essentially only allowed in yes/no questions, and not in if-clauses, comparatives or free relative clauses. The data in (6) illustrate this distribution:

| (6) | a. | Hai | visto | nessuno | per | caso? | |||||

| have.2sg | seen | nobody | for | chance | |||||||

| ‘Have you seen anybody, by chance?’ | |||||||||||

| b. | *Avvertimi | se | vedi | nessuno | in piazza. | ||||||

| warn=me | if | see.2sg | nobody | in square | |||||||

| ‘Warn me if you see someone in the square.’ | |||||||||||

| c. | *È | la cosa | più strana | che | abbia | detto | nessuno. | ||||

| is | the thing | more strange | that | has | said | nobody | |||||

| ‘It is the strangest thing that someone said.’ | |||||||||||

| d. | *Chi | ha | visto | nessuno, | non dice | la verità. | |||||

| who | has | seen | nobody | Neg tells | the truth | ||||||

| ‘Who has seen somebody is not telling the truth.’ | |||||||||||

Notice that this variety is the colloquial Italian variety considered standard in the region and not one of the local dialectal varieties, which are more similar to SIDs in this regard. Hence, if we compare the regional Italian of Veneto with Sicilian, the NCIs are one step “weaker,” since they occur in one further environment besides the negative one.

4.3. Third Step: Tuscan Italian

If we consider the Tuscan variety of standard Italian spoken in Florence, the NCIs are licensed not only in yes/no questions but also in if-clauses. Nevertheless, comparative and free relative clauses are still not possible environments for NCIs:

| (7) | a. | Hai | visto | nessuno | per | caso? | ||||

| have.2sg | seen | nobody | for | chance | ||||||

| ‘Have you seen anybody, by chance?’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Avvertimi | se | vedi | nessuno | in piazza. | |||||

| warn=me | if | see.2sg | nobody | in square | ||||||

| ‘Warn me if you see someone in the square.’ | ||||||||||

| c. | *?È | la cosa | più strana | che | abbia | detto | nessuno | |||

| is | the thing | more strange | that | has | said | nobody | ||||

| ‘It is the strangest thing that someone said.’ | ||||||||||

| d. | *Chi | ha | visto | nessuno, | non dice | la verità. | ||||

| who | has | seen | nobody | Neg tells | the truth | |||||

| ‘Who has seen somebody is not telling the truth.’ | ||||||||||

We asked ten native speakers of the Tuscan Italian for their judgements, and they unanimously agreed that NCIs are not only allowed in yes/no questions, but are also possible in (7b). Marginally, some speakers accept the comparative context (but never the free relative one). For all speakers, (7c–d) are fully acceptable if the NCI is substituted by an existential quantifier (è la cosa più strana che abbia detto qualcuno/chi ha visto qualcuno, non dice la verità). Interestingly enough, at present, we have not found a variety that allows NCIs in if-clauses but not in yes/no interrogatives, thereby confirming our implicational scale.

4.4. Fourth Step: Old Venetian

That the situation we observe today has changed is attested to by the fact that the older varieties were much more liberal in the distribution of NCIs. For instance, in Old Venetian (i.e., the variety of 13th and 14th century texts from Venice), in addition to yes/no interrogatives and if-clauses, it was also possible to find NCIs in comparative clauses. However, NCIs in free relatives are still not found in the texts we have at our disposal:

| (8) | a. | perciò | io | ve domando | se | nigun | de vui | sa | ||||

| so | I | you=ask.1sg | if | nobody | of you | knows | ||||||

| qui hè | questo cavalier. | |||||||||||

| who is | this knight | |||||||||||

| ‘…thus I ask you whether someone of you knows who is this knight.’ (Tristano veneto, 499) | ||||||||||||

| b. | Et | se | nigun | domandasse | de lui… | |||||||

| and | if | nobody | asks | about him | ||||||||

| ‘And if someone asks about him…’ (Tristano veneto, 279) | ||||||||||||

| c. | lo qual | sa | plui | de l’arpa, | plui | qua | nigun | che sia | ||||

| the which | knows | more | of the harp | more | than | nobody | that is | |||||

| al | mondo. | |||||||||||

| at-the | world | |||||||||||

| ‘…who knows about the harp more than anybody who is in the world.’ (Tristano veneto, 433) | ||||||||||||

Evidently, we cannot provide an ungrammatical example of free relatives in a variety that is not currently spoken, but the fact that they are not found in the texts9 is already significant. In free relatives, Old Venetian displays the non-negative NPI quantifier alcun/algun ‘any, some’:

| (9) | chi | volese | conseguir | raxon | da | algun | |

| who | wanted | get.inf | reason | from | anyone | ||

| ‘Who wanted to resolve a dispute with someone…’ (Capitolare bottai, 453) | |||||||

4.5. Fifth Step: Old Tuscan

The last step of our implicational scale is the one found in Old Tuscan, where all clause types we consider are possible licensing environments for NCIs, as shown in (10):

| (10) | a. | et | quivi | stette | 3 dì | per sapere | se | niuno | volesse | |||

| and | here | stayed.3sg | 3 days | to know | if | nobody | wished | |||||

| apporre | nulla. | |||||||||||

| provide | nothing | |||||||||||

| ‘and he stayed there three days in order to know whether someone wished to provide anything.’ (Cronica di Pisa, 118) | ||||||||||||

| b. | e | se | niuno | si opponea | loro… | |||||||

| and | if | nobody | refl=opposed | them | ||||||||

| ‘and if someone opposed them…’ (Cronica cose correnti, 199) | ||||||||||||

| c. | uomo | assai | più | pessimo | che | neun | che | anzi | se fosse. | |||

| man | much | more | bad | that | nobody | that | before | was | ||||

| ‘a man much worse than anyone who has been before.’ (Contro i pagani, 432) | ||||||||||||

| d. | chi | aveva | niente | di grano | el | serbava | ||||||

| who | had.3sg | nothing | of wheat | it= | kept.3sg | |||||||

| ‘…and who had some wheat retained it.’ (Cronaca senese, 139) | ||||||||||||

Interestingly enough, Tuscan seems to be more liberal than Venetan, both today and in the medieval period, as it is essentially one step beyond it in the evolution of allowed environments.

Summing up, for each step of the scale there is a variety, but there are no varieties that license NCIs in domains to the right of the scale which do not do so in those to the left. Here is a representation of the scale:

| (11) | Negative → Interrogatives → ‘if’ clauses → Comparatives → Free Relatives | ||||

| Sicilian | Veneto Italian | Tuscan Italian | Old Venetian | Old Tuscan | |

This distribution can be interpreted as a trend in the change from weak to strong NPIs, i.e., towards a loss of non-veridical contexts or in the opposite direction as a scale depicting the acquisition of the value of a negative quantifier depending on the direction in which it is read. The more NCIs that are found to the right of the scale, the weaker they are and vice versa. It must be pointed out that we are not suggesting that NCIs are like other “standard” NPIs, at least in some of these varieties, since this scale is not fully superimposable on the negative/non-veridical hierarchy of polarity items as emerging from Giannakidou (1997) and subsequent works, nor on the hierarchy of non-veridical contexts (Zwarts 1996). As noted above, the scale proceeds in a similar way to the semantic map of lexical indefinites already singled out in Haspelmath (1997), where interrogative is closer to negative contexts. Notice that Haspelmath labels ‘free choice’ those items of the functional lexicon used as free choice pronouns and determiners (like Italian chiunque ‘whoever’), while we take into consideration the indefinites found under a free relative wh item in order to have a clausal context (the labels in Haspelmath’s map are heterogeneous).

| (12) | [Implicational map of the distribution of indefinites (Haspelmath 1997, p. 64) |

As far as we know, there is at present no semantic explanation for the reason why there should be an implicational hierarchy concerning the distribution of NCIs in the typical contexts in which NPIs are used. We surmise that this scale is of semantic origin and cannot be explained only in syntactic terms.10 However, we do not intend to focus on the implicational scale here, since this is not the main research question of this work. We rather intend to analyze the other factor ruling the distribution of NCIs, namely the amount of lexical material internal to the NCI, which is indeed undoubtedly of syntactic origin, as discussed in the next section.

5. The Complexity Factor: Bare Versus Complex NCIs

The implicational scale described above is rather solid from the empirical point of view: The ASIt database does not contain any contradictory evidence of this, at least for yes/no questions and if-clauses in over 300 modern Italo-Romance dialectal varieties represented in the database; there is no variety allowing NCIs in if-clauses but not in polar questions. On the other hand, there is another factor that has to be taken into account and is clearly observable in the modern varieties, namely the bare versus complex status of the NCI. Complex NCIs tend to be less flexible in terms of the environment in which they occur, for instance, the speakers in the regional Italian of Veneto perceive a clear difference between (13a) and (13b), and they prefer the standard existential quantifier in the complex case (13a′):

| (13) | a. | *Ha | invitato | nessun | parente? |

| has | invited | no | relative | ||

| ‘Has s/he invited any relative?’ | |||||

| a′ | Ha | invitato | qualche | parente? | |

| has | invited | some | relative | ||

| ‘Has s/he invited any relative?’ | |||||

| b. | Ha | invitato | nessuno? | ||

| has | invited | nobody | |||

| ‘Has s/he invited anybody?’ | |||||

The same type of divergence is observed in Tuscan regional Italian for if-clauses, where bare NCIs are much more acceptable than complex ones:

| (14) | a. | *Se | vedi | nessuno | studente, | avvertimi. |

| if | see.2sg | no | student | warn=me | ||

| ‘Warn me if you see any student.’ | ||||||

| a′. | Se | vedi | qualche | studente,… | ||

| if | see.2sg | some | student | |||

| ‘If you see any student,…’ | ||||||

| b. | Se | vedi | nessuno, | avvertimi. | ||

| if | see.2sg | nobody | warn=me | |||

| ‘Warn me if you see anyone.’ | ||||||

In yes/no interrogatives, bare NCIs are still better than complex ones, which, however, are not excluded, but simply somewhat marginal.

| (15) | a. | ?Ha | invitato | nessun | parente? |

| has | invited | no | relative | ||

| ‘Has s/he invited any relative?’ | |||||

| b. | Ha | invitato | nessuno? | ||

| has | invited | nobody | |||

| ‘Has s/he invited anybody?’ | |||||

This effect is not found in modern varieties of regional Italian for the last two steps of the scale, namely comparatives and free relative clauses, which are ungrammatical with both the NCI words and phrases:

| (16) | a. | *È | la cosa | più strana | che | nessuno | abbia | detto. | ||||

| is | the thing | more strange | that | nobody | has | said | ||||||

| ‘It is the strangest thing anybody said.’ | ||||||||||||

| a′. | È | la cosa | più strana | che | qualcuno | abbia | detto. | |||||

| is | the thing | more strange | that | somebody | has | said | ||||||

| ‘It is the strangest thing anybody said.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | *È | la cosa | più strana | che | nessun professore | abbia | detto. | |||||

| is | the thing | more strange | that | no professor | has | said | ||||||

| ‘It is the strangest thing any professor said.’ | ||||||||||||

| b′. | È | la cosa | più strana | che | qualche professore | abbia | detto. | |||||

| is | the thing | more strange | that | some professor | has | said | ||||||

| ‘It is the strangest thing any professor said.’ | ||||||||||||

| c. | *Chi | ha | visto | nessuno, | non | dice | la verità. | |||||

| who | has | seen | nobody | neg | says | the truth | ||||||

| ‘Who has seen anybody, does not tell the truth.’ | ||||||||||||

| c′. | Chi | ha | visto | qualcuno, | non | dice | la verità. | |||||

| who | has | seen | somebody | neg | says | the truth | ||||||

| ‘Who has seen anybody, does not tell the truth.’ | ||||||||||||

| d. | *Chi | ha | visto | nessun | ladro, | non | dice | la verità. | ||||

| who | has | seen | no | thief | neg | says | the truth | |||||

| ‘Who has seen any thief, does not tell the truth.’ | ||||||||||||

| d′. | Chi | ha | visto | qualche | ladro, | non | dice | la verità. | ||||

| who | has | seen | some | thief | neg | says | the truth | |||||

| ‘Who has seen any thief, does not tell the truth.’ | ||||||||||||

However, in the old varieties, we see that complex items can indeed occur in these environments, so it seems that the effect was not present in Old Italian (or in Old Venetan). In (17) we provide a couple of examples for the comparative context.

| (17) | a. | fue | bello | più | che | neuno | altro omo | che | sia | o | ||

| was | beautiful | more | than | no | other man | that was | or | |||||

| sia | stato | |||||||||||

| was | been | |||||||||||

| ‘…he was more beautiful than any other man who ever lived.’ (Prediche sulla Genesi, 54) | ||||||||||||

| b. | e′ | romaravi | vedoa | e | plu | desconsejada | ka | |||||

| I | would.remain | widow | and | more | insane | that | ||||||

| nexuna | raïna | k’al | mundo | sia | nada. | |||||||

| no | queen | that at-the | world | is | born | |||||||

| ‘…I would remain a widow and more insane that any queen born in the world.’ (Leggenda di Santa Caterina, 267) | ||||||||||||

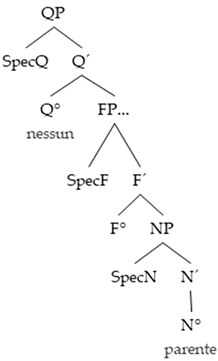

Evidently, one wonders why at first sight, complex NCIs look “more negative” in the sense that they do not occur outside negative domains, while simple NCIs can. It is rather straightforward to tie this effect to the previously discussed cases of bare/complex quantifiers that are located in different positions in the clause, since they have a different internal structure. In the next section, we present a possible analysis of this bare/complex effect.

6. The Analysis

If we assume that bare NCIs, on a par with bare quantifiers, are “slimmer” in their internal constitution with respect to complex ones, we still have to derive the fact that they seem to be less negative than complex ones. We argue that on a par with bare quantifiers, NCI words do not contain a lexical restrictor, i.e., there is no pro/NP at the bottom of the functional structure, but simply a sortal classifier-like element, like THING or PERSON in a Kaynian framework. This is shown by the fact that bare NCIs, just like other bare quantifiers, do contain a classifier like element, which can be observed in their morphology or in their etymological formation (nessuno, for instance, contains the numeral uno, corresponding to English one in no one, niente is built upon an element -ente(m) ‘thing’ or gente(m) ‘people’, depending on the etymology one accepts, see Garzonio and Poletto (2018, 237n) for discussion). Thus, we argue that their internal constitution is similar to that of bare quantifiers, i.e., it can be represented as in (18):11

| (18) |  |

Here, the only lexical item in the internal structure does not necessarily occupy the highest position at the edge of the nominal structure. We assume here the Déprez and Poletto (this volume) analysis and that NCIs can be intrinsically negative only if the negative feature is phase-aligned, i.e., if the internal negative feature they possess reaches the edge position in their internal structure, which means that the NCI lexical item itself must have moved to a phase edge (either vP or CP). This means that in a structure like (18), where the negative feature is embedded inside the QP, the NCI is not intrinsically negative. Thus, NCI words can be interpreted as non-negative indefinites. Furthermore, we also have the other option, where the lexical element nessuno is moving to the internal phase edge, as illustrated in (19):

| (19) |  |

In this case, the NCI words are considered as intrinsically negative, because the lexical item bearing the negative feature is visible on the phase edge, and as such, it cannot occur in non-negative contexts. Hence, we find variation among the Italian dialects we have considered.

As for complex items, which possess a fully-fledged nominal structure with a lexical N restrictor at its bottom, the probability that the element nessuno is found at the phase edge must be higher, because the lower portion of the structure is occupied by a lexical noun, and is not represented by nessuno itself. Complex NCIs have a negative determiner, which can indeed be located at the highest edge of the nominal phase and therefore visible from the outside. Thus, they cannot occur other than in anti-veridical (i.e., negative) contexts.

| (20) | Non ho invitato [QP nessun [NP parente ]]. |

| ‘I have invited no relatives.’ |

| (21) |  |

It is possible that nessuno is not sitting at the edge of the QP, but rather in an intermediate FP from which it then raises: in this case, it is in fact a determiner of a lexical N and not a single entity together with the classifier. However, complex NCIs have a higher probability of displaying the negative feature on their edge. On the contrary, NCI words do not have a lexical restrictor, and the only lexical item in their internal structure does not necessarily occupy the highest position at the edge, hence the negative feature is not visible at its edge. Thus, they can be interpreted as non-negative indefinites, and we find variation.

7. Concluding Remarks

NCIs are a special type of indefinites with a distribution that makes them similar to NPIs, since some of them can occur in non-negative contexts, and others cannot. We have first established an implicational hierarchy of non-veridical contexts that starts with yes/no interrogatives, goes to if-clauses, then to comparatives, and ends with free relative clauses. This hierarchy is consistently observable in the Italo-Romance domain. We surmise that this implicational hierarchy is of semantic origin and purely use it to describe another problem, i.e., the internal complexity of the NCI itself. We have proposed that the microvariation they display regarding the nonveridical contexts in which they can or must appear is related to the Merge position the NCI itself and occupies in its internal nominal structure. Those elements which are directly merged on the edge of the NCI are indeed negative and can only occur in negative clauses. Those that are more tolerant are more similar to weak NPIs, i.e., their presence can be licensed by other non-negative operators. Complex NCIs tend to be restricted to anti-veridical contexts because the NCI portion must be merged at the edge of the nominal expression and thus the negative feature is readable from outside of the nominal phase.

In other words, since complex NCIs have a higher probability of displaying the negative feature on their edge, due to the presence of an independent noun occupying the lower portion of the nominal structure, they tend to behave as strong NPIs. On the contrary, NCI words are merged in the classifier position and do not necessarily reach the edge of the nominal phase, and therefore behave as weaker NPIs. This explains why there is a complex/bare opposition overlapping the context microvariation. In this work, we have not considered the relationship between Ns and NPIs, which lies beyond the scope of a work on Romance and remains to be seen for future research.

Furthermore, it should be pointed out that we have not taken into consideration the problem of the source of the variation displayed by Italian and Italo-Romance varieties. There is a clear impression of a diachronic loss of non-veridical contexts where NCIs can be used (this has been shown for Venetan dialects). Our goal was to provide a micro-typological view to show that the implicational scale we have found is always valid across all Italo-romance varieties. However, a diachronic perspective can tell us more about the scale itself and also about other possible contexts that have to be taken into consideration. We leave this to future research, likely on specific domains inside the broader Italo-Romance group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and C.P.; methodology, J.G. and C.P.; investigation, J.G. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G. (Section 1, Section 4, Section 6) and C.P. (Section 2, Section 3, Section 5, Section 7); writing—review and editing, J.G. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since no personal data were collected from informants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study and not taken from the cited databases are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank four anonymous reviewers for all the comments and the suggestions on the previous versions of this article. The authors also thank Ryan Chon, Silvio Cruschina, Cristina Guardiano, Giuseppe Magistro and Jessica Rita Messina for discussing the data and the analysis presented in this contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In standard Italian, the NPI element which can be used in these cases is alcuno ‘any’, which is stilistically marked. In more colloquial variants of the language (like in Italo-Romance dialects) it is usually substituted by the generic existential quantifier qualche/qualcuno ‘some/somebody’. Since we are interested in the distribution of NCIs, we will not take into consideration these alternative constructions here. |

| 2 | Notice, however, that Acquaviva (1999) pointed out a separate difference between the two types of items, that is that Italian complex NCIs, different from bare NCIs, disallow a negative spread (see also Giannakidou 2006). Since this property is strongly connected to the non-strict negative concord configuration, i.e., the relation between preverbal NCIs and the standard sentential negation, we leave it aside in our analysis. For other types of differences between pronouns and full DPs in negative concord configurations, see van der Auwera and Koohkan (2022). |

| 3 | This clearly goes against the idea that functional structure always depends on a lexical element located at the bottom of the layer, as proposed in the extended projections approach by Grimshaw (1991), since in this view there should not be any functional elements without a lexical one at their foot. This is precisely what we propose here, and it is possibly a property that all types of pronouns have, i.e., they are just functional “pillars” without an NP at their base. |

| 4 | An anonymous reviewer suggests that other contexts could be added to the investigation. More precisely, other possible contexts are temporal clauses introduced by ‘before’ or under verbs corresponding to ‘doubt’ or ‘be glad’. We have decided to exclude the first type because in Italian and in Italo-Romance varieties ‘before’ can be followed by a special type of expletive negation (cf. Greco 2019 on this), which obligatorily triggers a negative concord. The other two cases are not consistently represented in the diachronic corpus. Under verbs corresponding to ‘doubt’, some speakers of Italian allow postverbal NCIs without non (Zanuttini 1991, p. 143), but this is excluded in the regional Italian of both Veneto and Tuscany, so we leave these contexts to future research with a larger dataset of sinchronic varieties. |

| 5 | It is also possible, at least for some quantifiers, to occur in an adjectival position lower than the article. This is a structure we do not handle here, since it is never found with NCIs. |

| 6 | We consider here only yes/no questions, since wh-questions are problematic in terms of intervention effects between the wh-item and NCIs, as well as various types of quantifiers. There is a clear difference between sentences where the NCI is the object and the wh-item is the subject and those where the opposite is true. When the wh-item is the object and crosses over the NCI in the subject position, we obtain ungrammaticality. This is most probably a classic intervention effect, and it is the reason why we confine our analysis to yes/no questions here. |

| 7 | Here we consider only clausal comparison, and not the comparison between nominal expressions, since clausal comparison is more similar to the other environments considered here. Notice, however, that the comparative sub-clause can be elliptical. |

| 8 | The ASIt database is freely accessible and searchable at the following website: http://asit.maldura.unipd.it/; there are no cases of NCIs used in non-negative environments in examples from the Southern Italian Dialects. |

| 9 | The Old Venetan texts are present in the OVI database and have been studied in the framework of the project GraVO (Grammatica del veneto delle Origini ‘A Grammar of Old Venetan’) of the University of Padua. For further details, see Garzonio (2022). |

| 10 | One might try to implement it in terms of two factors. One concerns the similarity between negation and other types of operators: the more similar they are, the easier it is for NCIs to occur in those contexts. The other concerns the featural constitution of NCIs in the different varieties. Since the main research question of this work is about the different behavior of bare and complex NCIs, we do not pursue this problem here. |

| 11 | Here we dub the highest projection in the NCI as QP, although it is not clear what these elements are. This does not mean we are taking a stand on the long debated question whether NCIs are quantificational elements or polarity elements. The label here is only meant as a place-holder. |

References

- Acquaviva, Paolo. 1999. Negation and operator dependencies: Evidence from Italian. Lingua 108: 137–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baunaz, Lena. 2011. The Grammar of French Quantification. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency. A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In Clitics in the Languages of Europe. Edited by Henk van Riemsdijk. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 145–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruti, Massimo. 2011. Regional varieties of Italian in the linguistic repertoire. Journal of the Sociology of language 210: 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetjes, Jenny. 1997. Quantifiers and Selection. On the Distribution of Quantifying Expressions in French, Dutch and English. The Hague: HAG. [Google Scholar]

- Garzonio, Jacopo. 2022. Descrizione grammaticale e variazione linguistica: Il caso della dialettologia storica. Storie e Linguaggi 8: 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Garzonio, Jacopo, and Cecilia Poletto. 2017. How bare are bare quantifiers? Some notes from diachronic and synchronic variation in Italian. Linguistic Variation 17: 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzonio, Jacopo, and Cecilia Poletto. 2018. The distribution of quantifiers in Old and Modern Italian: Everything or nothing. In Word Order Change. Edited by Ana Maria Martins and Adriana Cardoso. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 221–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1997. The Landscape of Polarity Items. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2000. Negative… Concord? Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18: 457–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2006. N-words and Negative Concord. In The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. Edited by Martin Everaert and Henk C. Van Riemsdijk. Volume III: Chapter 45. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 327–91. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2020. Negative Concord and the nature of Negative Concord Items’. In The Oxford Handbook of Negation. Edited by Viviane Déprez and Espinal M. Teresa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 458–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Hedde Zeijlstra. 2017. The landscape of negative dependencies: Negative Concord and n-words. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Syntax, 2nd ed. Edited by Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk. Hoboken: John Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, Matteo. 2019. Is expletive negation a unitary phenomenon? Lingue e Linguaggio 1: 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Grewendorf, Günther, and Cecilia Poletto. 2005. ‘Von OV zu VO: Ein Vergleich zwischen Zimbrisch und Plodarisch. Diversitas Linguarum 9: 114–30. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, Jane. 1991. Extended Projection. Master’s thesis, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin. 1997. Indefinite Pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard S. 2005. Movement and Silence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Svenonius, Peter. 2008. The position of adjectives and other phrasal modifiers in the decomposition of DP. In Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse. Edited by Louise McNally and Chris Kennedy. Oxford: Oxford University press, pp. 16–42. [Google Scholar]

- van der Auwera, Johan, and Sepideh Koohkan. 2022. Extending the typology: Negative concord and connective negation in Persian. Linguistic Typology at the Crossroads 2: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1991. Syntactic properties of sentential negation. A comparative study of Romance languages. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2004. Sentential negation and Negative Concord. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Zwarts, Frans. 1996. Three types of polarity. In Plural Quantification. Edited by Fritz Hamm and Edward W. Hinrichs. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 177–238. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).