Abstract

Language processing impairments across different dimensions result in deficits of informational content, syntactic complexity, and morphological well-formedness of sentences produced by people with aphasia (PWA). Deficits in language processing affect linguistic skills of bi/multilingual PWA in all languages that they have acquired prior to aphasia. However, the impairments of dual or multiple languages in aphasia may not necessarily be parallel. One language may be more preserved than another and be recovered at different paces, including sentence production abilities. This scoping review aims to compare syntactic characteristics and errors demonstrated by bi/multilingual PWAs between their acquired languages and to explore the nature of bilingual impairments in primary progressive aphasia (PPA). We conducted an online search on three databases (MEDLINE, SciVerse Scopus, and Taylor and Francis publications) for original studies on sentence production of bi/multilingual aphasia that were published between 1991 and 2021 using keywords related to “bilingualism”, “aphasia”, and “speech production”. Based on the titles, abstracts, and full-text screenings, 13 studies were found to have met our inclusion criteria. A qualitative synthesis of the accumulated evidence was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines. Collectively, past researchers reported dominance in L1 with higher occurrences of linguistic errors in L2 among participants with sudden onset aphasia. In PPA, language impairments were found to be comparable between L1 and L2, which may indicate parallel deterioration. It is noted that this review is not exhaustive and many of the reviewed studies were based on single case studies. This review also highlighted an urgent need for investigation into multilingual PPA to fully comprehend the nature of sentence production impairment.

1. Introduction

1.1. Sentence Production in People with Aphasia

Aphasia is a disorder caused by brain damage that results in impaired processing of language input and output in various forms, including auditory–verbal, textual, and sign language (Hallowell 2023). Damage to language-related parts of the brain affects language processing in many ways, such as the ability to combine content, the complexity of syntactic structures, the use of grammatical rules, the formation of morphological units, and the rate of language production (Wilshire et al. 2014). People with aphasia (PWA) experience a variety of language difficulties, including sentence production deficits (SPD), also known as agrammatism. Agrammatism refers to the difficulty to produce complete or correctly constructed sentences (Poirier et al. 2021). This condition is marked by poor and halted connected speech, deletion or substitution of grammatical morphemes and verbs, diminished fluency, impaired sentence repetition, and difficulties with naming, reading, and writing. Oral comprehension of phrases and sentences with meanings that are dependent on grammar can also be impaired. In agrammatism, sentences produced by PWA are reduced in both length and grammatical complexity (Ardila 2014). In the monolingual aphasia literature, SPD was reported to occur not only in PWA who experienced sudden brain insults, but was also demonstrated by individuals experiencing progressive language impairments, known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). PPA is a neurodegenerative disorder where language functions continue to decline over time without any significant impairments in other cognitive domains (Hallowell 2023). In PPA, language abilities are significantly impaired despite the preservation of non-linguistic cognitive abilities (Hallowell 2023). Due to the progressive death of brain cells, language impairment worsens over time in PPA. Even though the pathophysiological nature of sudden-onset aphasia and PPA differ, similar aphasia symptoms are observed (Grossman and Irwin 2018). People with a non-fluent variant of PPA (nvPPA) and those with sudden-onset Broca’s aphasia, for instance, exhibit slowed, labored speech with grammatical deficits in sentence production. These similarities may be the result of brain damage occurring at the same anatomical sites (Grossman and Irwin 2018).

Sentence production is the process of stringing together words in accordance with the grammatical order of a language in order to convey meaning. Bresnan (2001) defined argument structure as lexical information about the number of arguments, their syntactic type, and their hierarchical organization that is required for the mapping to syntactic structure. Thompson (2019) found that monolingual PWA with chronic agrammatism had difficulties producing complex syntactic structures in their sentences. In particular, PWA have poor abilities in processing noncanonical sentences compared to canonical forms (Garraffa and Grillo 2008; Hanne et al. 2015; Townsend and Bever 2001). Based on the Trace Deletion Hypothesis (see Grodzinsky 1990, 2000), PWA tend to assign the thematic role to the first noun phrase encountered in a sentence, which results in judgment errors in processing noncanonical sentences. Grodzinsky (1990, 2000) suggested that PWA use the extralinguistic heuristic only after they have finished processing a sentence.

Lexical–semantic components play a crucial role in establishing syntactic structures in language production. Impairment of lexical–semantic access may result in word retrieval difficulties and affect the constructions of sentences (Caramazza and Hillis 1991; Kambanaros 2009; Dragoy and Bastiaanse 2010). The two most basic lexical–semantic categories comprise nouns and verbs. Other categories include modifiers, such as adjectives, prepositions, and questions. Concrete nouns consist of multiple hierarchical levels. Different nouns may share similar semantic properties. In contrast, verbs have a shallower semantic structure and fewer shared semantic features (Vinson and Vigliocco 2002); however, verbs govern the argument and syntactic structure of a sentence. Verbs play a central role in determining the argument structure of a sentence by encoding who performs an action and who is affected by it (i.e., who does what to whom). However, verbs are more difficult to retrieve because of lower imageability and frequency than nouns. In addition, they are more vulnerable to impairment following brain damage, where difficulties specifying the thematic role of sentences among PWA frequently co-occur with impaired verb processing (Whitworth et al. 2015). According to the Argument Structure Complexity Hypothesis, verbs with a higher argument structure complexity (i.e., a greater number of arguments or noncanonical thematic mapping) are more difficult to be produced by PWA (Heinzova et al. 2022; Lee and Thompson 2004).

1.2. Language Production in Bilingual PWA

Language processing is also affected in PWA who are bilingual. Kambanaros (2016) highlighted that bilingual aphasia allows researchers to determine whether linguistic and grammatical distinctions, such as those between verbs and nouns, are language specific. Studies on bilingual aphasia may also provide insights into the neural network involved in language processing when two different languages are involved. For example, differences in verb and noun processing in two or more languages may indicate whether dual or multiple language processing occurs in similar cortical and subcortical brain regions (Green 2003). However, Kambanaros (2016) reported that only a few studies have involved the bilingual and/or multilingual population with aphasia (see Hernández et al. 2007, 2008; Kambanaros and van Steenbrugge 2006; Kambanaros 2009; Faroqi-Shah and Waked 2010). Heinzova et al. (2022) hypothesized that the complexity of argument structure may vary by language type and predicted different results for English/Spanish versus Basque. In their study, results showed that a person who speaks both Spanish and English makes the same number of errors in both languages as predicted by the ASCH. However, a participant who speaks Spanish and Basque does not match either the ASCH or their predictions. The study concluded that argument processing costs might depend not only on the number of arguments and the canonicity of thematic mapping but also on language types, language pairs, and post-onset proficiency in bilingual PWA, as well as on individual differences.

Deficits in different languages may not always occur to the same extent, nor do languages recover to the same degree. Paradis (2004) suggested six different recovery patterns, namely, parallel recovery, differential recovery, antagonistic recovery, alternating antagonism, blended recovery, and selective and successive recovery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recovery patterns of languages among bilingual PWA. Adapted from Paradis (2001).

In a recent review, Kuzmina et al. (2019) reported that language abilities of bilingual PWA are better preserved in the dominant language (L1) when the less dominant language (L2) was acquired after seven years old. When L2 was acquired before seven years old, language abilities of L1 and L2 were reported to be comparable. The effects of age of L2 acquisition were found mildly moderated by the proficiency and frequency of usage of L2 prior to aphasia (Kuzmina et al. 2019). Although the nature of language impairments and recovery in monolingual and bilingual aphasia may differ, we have not discovered a review on sentence production abilities in bilingual or multilingual aphasia. Past reviews on bilingual aphasia highlighted aspects of aphasia recovery, assessment, and treatment (Lorenzen and Murray 2008) and methods for eliciting sentence production in PWA (Mehri and Jalaie 2014).

The current review aims to address the following research question: “What is the nature of sentence production impairments in bilingual aphasia?” This review explores and compares aspects of sentences produced by bilingual and multilingual PWA in two or more languages that they have acquired, as reported in published studies. In addition, this review aims to compare sentence production abilities in sudden onset versus progressive bi/multilingual aphasia. An appreciation of the pattern and features of sentence production in bilingual aphasia may shed some light on dual or multiple language processing, which is fundamental for developing an accurate theory and models of bilingualism (Heinzova et al. 2022).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Searching Strategy and Citation Management

A priori protocol was established based on a scoping review guideline—PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-Scr; Tricco et al. 2018) and a guideline by Levac et al. (2010). Our initial search was conducted on three electronic databases: MEDLINE, SciVerse Scopus, and Taylor and Francis. These databases cover a broad range of disciplines within the field of health sciences, specifically aphasia. The search was limited to articles written in English and published between 1990 and 2021. The search consisted of keywords relevant to bilingualism, aphasia, and verbal production. The Boolean phrases used were: ((((((((bilingualism) OR (bilingual)) OR (multilingual)) OR (multilingualism)) OR (trilingual)) OR (trilingualism)) OR (dual language)) AND (((aphasia[MeSH Terms]) OR (agrammatic)) OR (agrammatism))) AND ((((sentence) OR (syntactic)) OR (syntax)) OR (word order). All citations were imported into a Mendeley bibliographic manager, which automatically removed duplicated citations. Prior to the screening process, additional duplicates were manually identified and removed.

2.2. Screening Procedures and Evidence Synthesis

The articles were initially screened based on their titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text screening based on the eligibility criteria in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for articles screening.

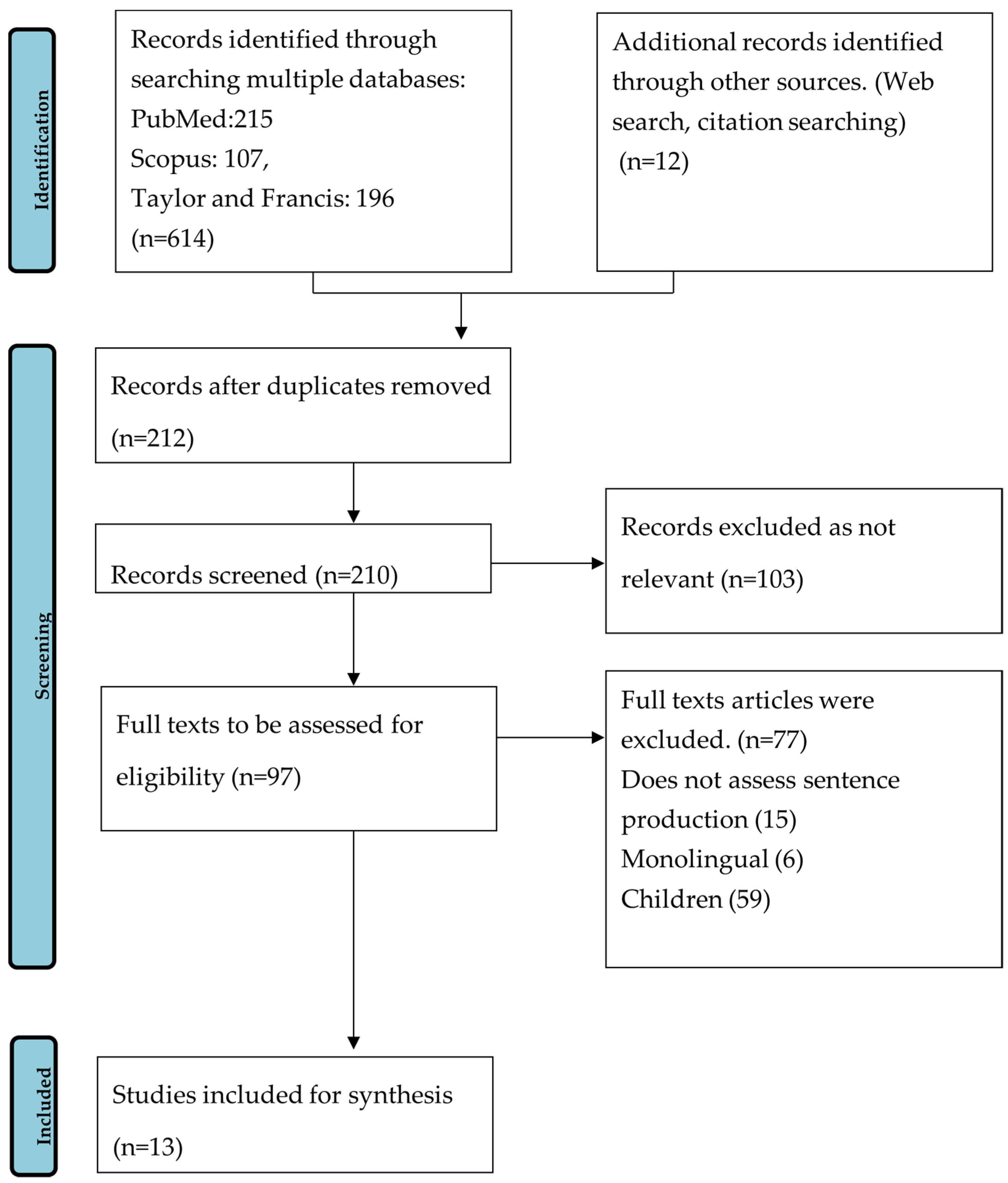

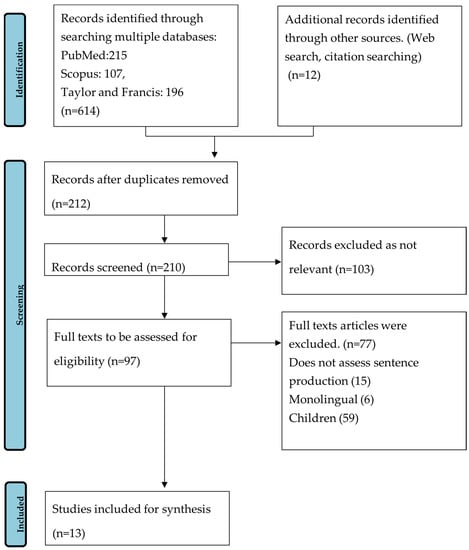

For the initial screening, all titles and abstracts were reviewed by two of the authors independently. The authors exhibited 15% disagreement at this stage, which was then resolved through a discussion based on this review’s objectives. Upon agreement between the authors, articles were selected for full-text screening. Articles without available abstracts were also included in the full-text screening process. The full-text screening was conducted by the first author and was also based on the inclusionary and exclusionary criteria. The number of articles that were included and excluded during the screening and review processes is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Screening procedure flowchart.

During the full-text screening, articles that did not meet the inclusionary and exclusionary criteria were further excluded. For articles that met our criteria, specific information was collated from each selected article, including the year of publication, study objectives, study design, participants’ background, materials and procedures, and study limitations. The second author reviewed collated information from full-text reviews. Similar to the initial screening phase, discrepancies between the authors were resolved through discussions and consensus. The accumulated evidence was synthesized qualitatively to determine the patterns of sentence production and production errors for L1 and L2 of PWA in the reviewed studies.

3. Results

In this review, 14 articles were assessed in detail (Table 3). Among the included studies, 10 articles described single case studies, while the rest involved between-group (control versus PWA) and within-group PWA comparisons. Ten articles on participants with sudden onset aphasia reported a range of onset duration between two months and 17 years. Four articles reported on single cases of PPA with an onset ranging between 2 years and 6 years. We found studies focused on the use of verbs and adverbs in sentences (n = 4), word order (n = 3), language priming/mixing (n = 5), and fluency and grammatical qualities (n = 3).

Table 3.

Language Production among PWA: Comparison between L1 and L2.

Overall, PWA produced simplified sentences with some morpheme substitutions and omissions, such as morphemes that indicate past tense and free grammatical morphemes (e.g., Alexiadou and Stavrakaki 2006; Bastiaanse 2013; Imaezue et al. 2017; Machado et al. 2010). Participants with sudden onset aphasia were reported to struggle with applying grammatical structures and using correct word order (Alexiadou and Stavrakaki 2006; Bastiaanse 2013; Sang 2015; Lerman et al. 2019; Imaezue et al. 2017). In a few studies, PWA demonstrated deficits in verb retrieval, verb inflection, and use of transitive and ditransitive verbs (Imaezue et al. 2017; Lerman et al. 2019). In other studies, the authors reported a lack of congruence in subject–verb agreements, occurrences of subject deletions, and erroneous use of prepositions in PWAs’ sentences (Sang 2015).

Some impairments in sudden onset aphasia and in PPA were found to be similar. Three out of four cases of PPA reported deficits in grammatical structure, word order, and verb production in sentences (Druks and Weekes 2013; Machado et al. 2010; Zanini et al. 2011). In addition, PPA studies reported non-fluent, laborious, and effortful speech with word-finding pauses, broken-off phrases, and interjections of unspecified words in PWAs’ production, such as “it” and “that” (Filley et al. 2006; Machado et al. 2010).

Based on comparisons of L1 versus L2, several studies reported that language impairments were more evident in L2, and L1 was reported to be more preserved (Adrover-Roig et al. 2011; Alexiadou and Stavrakaki 2006; Imaezue et al. 2017; Kong and Weekes 2011; Lerman et al. 2019; Zanini et al. 2011). Other studies found that syntactic impairments were comparable between languages (Druks and Weekes 2013; Filley et al. 2006; Goral et al. 2019). A few studies demonstrated that language mixing was prominent among bilingual PWA when producing sentences (Adrover-Roig et al. 2011; Goral et al. 2019; Kong and Weekes 2011). In two studies, the authors highlighted that the patterns of language impairments in L1 and L2 may differ where certain impairments may be more prominent in one language, while other types of impairments were demonstrated more often in another language (Alexiadou and Stavrakaki 2006; Goral et al. 2019). Additionally, Verreyt et al. (2013) demonstrated preserved priming effects between languages in their study.

Looking at the PPA case studies (Study 11–14 in the Table 3), Filley et al. (2006) and Machado et al. (2010) reported similar results where the functioning of a language that was more recently and frequently used was better regardless of the order of language acquisition. A similar report was found in Zanini et al. (2011) as an L2 that was greatly impaired was used less frequently by the participant. However, in the case of PPA according to Druks and Weekes (2013), both languages deteriorated in a similar way, even though L2 was used as a dominant language in the participant’s adult life. Interestingly, one key difference in Druks and Weekes (2013) study was the age when the second language was acquired. That participant acquired the second language significantly later compared to participants of other PPA case studies.

4. Discussion

In this review, the language production of bilingual PWA with either sudden onset aphasia or PPA was explored, specifically with regards to their sentence production. The bilingual PWA demonstrated comparable features of agrammatism, such as errors in grammatical structures, word order, substitution, and deletion of morphemes and verbs. In addition, word retrieval difficulties were found commonly co-occurring with difficulties in sentence production, which is one of the characteristics of agrammatism. With the presence of incomplete sentences, the omission of arguments, the production of semantic errors, or the reliance on general words or pronouns, noun retrieval difficulties may have an impact on sentence production among PWA (Webster et al. 2004). It is believed that difficulties in retrieving verbs have a greater effect on sentence production. Due to the semantic representation of the verb that encodes information in the form of the sentence’s argument structure (Levelt 1989), difficulties in accessing verbs result in a reliance on single words and phrases and the absence of sentence structure (Berndt et al. 1997).

Among bilingual PWA, we found that the extent of agrammatism in L1 versus L2 tends to vary. This is partly due to grammatical rules and the typological distances of the languages involved. For example, in Sang’s (2015) study, Kiswahili is a highly agglutinative language, whereas English is an analytical language. This difference presents a situation where English inflects the verb with grammatical elements while Kiswahili uses free morphemes instead. The same pattern was also duplicated in Bastiaanse (2013), where another agglutinative language, Swahili, showed a similar pattern in verbs compared to English. The past tense for verbs in Swahili was maintained as present tense because an omission of the tense results in non-words, whereas the omission of morphemes is possible in English. Similarly, in Alexiadou and Stavrakaki (2006), performance is affected by a syntactic discrepancy for verb movement exhibited in English but not in Greek. Therefore, it could be seen that the generalization of morphology across L1 and L2 may in some studies function as a facilitating device but not in other studies (Alexiadou and Stavrakaki 2006; Bastiaanse 2013; Sang 2015).

Additionally, the reviewed studies generally showed better language abilities and recovery of L1 rather than L2 among bilingual PWA. Sentence production in L1 was found to be superior to L2 in various aspects, including the selection of verbs and adverbs, word order, and grammaticality of sentences. Additionally, studies included in this review reported more error patterns in L2 compared to L1, such as verb deletion and errors in word order. Better performance in L1 compared to L2 was observed for a variety of languages. This appears consistent with the assumption that the impairment may be in the participant’s language system (Abutalebi and Green 2007; Green 2003; Green et al. 2006; Grosjean 1998; Ullman 2001, 2005). Ullman (2001, 2005) proposed that declarative memory plays a greater role in the syntactic processing of L2, while procedural memory is more significant in L1 processing among late bilingual users. One striking similarity across reviewed studies is the relatively late acquisition of L2 among participants. According to Ullman, the late acquisition of L2 led to the implicit/automatized construction of sentences in L1; however, sentence construction in L2 depended on explicit processing and was non-automatized. Lack of automaticity of declarative memory may contribute to greater retrieval errors in L2 production compared to L1, which may, in turn, lead to the lack of parallel language impairments in bilingual users with aphasia. This is further supported by the review by Kuzmina et al. (2019), who found that the age of acquisition (AoA) of L2 influenced the level of comparability between L1 and L2 performances. In studies on bilingual participants with PPA, L1 was also found to be better preserved than L2.

This can further be justified based on the case of parallelism in PPA, in which Druks and Weekes (2013) argued that explicit memory plays an important role in L2 processing when L2 is acquired later in life. According to the convergent hypothesis (Abutalebi and Green 2007; Green 2003; Green et al. 2006; Grosjean 1998), the developmental time windows of explicit and implicit memory systems determine the processing of dual languages. Language acquisition of L1 before the age of 5–6 years old serves as the implicit memory system, while language acquired later serves as the explicit memory for adults. Acquiring another language is not limited to securing additional vocabulary (word forms and morphemes) but more of its vocabulary–conceptual functional link and sensory representations of their referents and interface with combinatorial syntactic and phonological processes (Green et al. 2006), which needs to be maintained. This suggests that the neural representation of L2 converging with L1 among PWA affects the languages in similar ways after onset of L2 acquired at an early age. In summary, parallel language deterioration provides supporting evidence of the effect of age on language acquisition in terms of the nature of impairment among L1 and L2 following onset (Kuzmina et al. 2019). Unfortunately, studies on bilingual PPA are quite limited. For future studies, we recommend that longitudinal studies be conducted on PPA to help explain the patterns of impairments among sudden onset bilingual aphasia.

The studies reviewed also looked at factors that contributed to differential patterns. Three main factors were identified: (i) characteristics of L1 versus L2 (Alexiadou and Stavrakaki 2006; Bastiaanse 2013; Sang 2015), (ii) factors on aphasia types and severity (Goral et al. 2019; Verreyt et al. 2013), and (iii) factors on brain lesion area (Adrover-Roig et al. 2011; Filley et al. 2006; Goral et al. 2019; Imaezue et al. 2017). In terms of the characteristics of L1 versus L2, the nature of morphological typological structure (e.g., agglutinative versus analytic and parametrization of verb movement and tenses) was found to be influenced by the frequency of language use (Alexiadou and Stavrakaki 2006; Lerman et al. 2019; Machado et al. 2010). This may be because what is explicitly learned in later childhood is sustained by declarative memory processes, thus, L2 became susceptible to more phonemic paraphrasing and morphological and syntactic errors (Druks and Weekes 2013; Green et al. 2006; Imaezue et al. 2017; Zanini et al. 2011). In terms of aphasia types and severity, differential patterns of bilingual aphasia recovery may be observed. Collectively, two major patterns of aphasia recovery were discovered in the reviewed studies—parallel recovery (both languages recover at the same speed) and differential recovery (recovery is more pronounced in one language compared to the other language; the recovery in both languages differs qualitatively), as in Verreyt et al. (2013). Finally, it is important to consider factors related to the brain lesion areas. Previous studies have shown that a lesion in the basal ganglia may result in L1 production deficits while leaving L2 spontaneous speech better preserved (Adrover-Roig et al. 2011; Fabbro 2001). We believe that the presence of neuroanatomic relationships with linguistic processing is crucial for comparable abilities in dual languages. In the past, the age of acquisition was suggested to develop distinct lexical subsystems for the native language and the language that was acquired later (Green et al. 2006).

5. Conclusions

This study summarized the characteristics of language impairments in bi/multilingual aphasia. Interestingly, we found similarities in the patterns of bi/multilingual impairments between individuals with sudden onset aphasia and PPA. The reviewed studies generally showed better language abilities and recovery of L1 compared to L2 in bilingual PWA. The results were significantly in favor of parallel deterioration when both languages (L1 and L2) were acquired earlier in life. Meanwhile, when another language was acquired much later, they showed selective deterioration. Similarly, among the control group, the age of acquisition of language reciprocated similar patterns in their language performance. In sequential asymmetrical language acquisition, the earlier language was found to exhibit superior performance compared to language acquired later. It is worth highlighting that all reviewed studies compared participants’ abilities in their L1 and L2 prior to aphasia, except for one study by Sang (2015) that looked at the PWAs’ abilities in two non-dominant languages—English and Kiswahili. This study stood out as it could serve as a new trajectory that needs to be explored, especially for multilingual people. As sentence production involves multiple linguistic processes (i.e., grammatical, morphological, lexico-semantic, and syntactic) a more comprehensive picture that captures grammatical competency in sentence production should be included in future review studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N. and F.H.H.; methodology, A.N. and F.H.H.; software, A.N.; validation, F.H.H.; formal analysis, A.N.; resources, A.N.; data curation, A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N. and F.H.H.; writing—review and editing, R.A.R. and M.A.A.A.; visualization, A.N.; supervision, F.H.H.; project administration, F.H.H.; funding acquisition, F.H.H., R.A.R. and M.A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, grant number GGPM-2020-022.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia for the financial support. We extend our appreciation to Shamim Mohd Affian and Nurul Ain Mohd Tahir for their insightful comments on this review. We are also grateful for Murhaini Muid for her assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abuom, Tom O., and Roelien Bastiaanse. 2013. Production and comprehension of reference of time in Swahili-English bilingual agrammatic speakers. Aphasiology 27: 157–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutalebi, Jubin, and David Green. 2007. Bilingual language production: The neurocognition of language representation and control. Journal of Neurolinguistics 20: 242–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrover-Roig, Daniel, Nekane Galparsoro-Izagirre, Karine Marcotte, Perrine Ferré, Maximiliano A. Wilson, and Ana Inés Ansaldo. 2011. Impaired L1 and executive control after left basal ganglia damage in a bilingual Basque-Spanish person with aphasia. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 25: 480–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, and Stavroula Stavrakaki. 2006. Clause structure and verb movement in a Greek-English speaking bilingual patient with Broca’s aphasia: Evidence from adverb placement. Brain and Language 96: 207–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardila, Alfredo. 2014. Major aphasic syndromes: Wernicke’s aphasia and Broca’s aphasia. In Aphasia Handbook. Miami: Florida International University, pp. 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaanse, Roelien. 2013. Why reference to the past is difficult for agrammatic speakers. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 27: 244–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndt, Rita, Charlotte C. Mitchum, Anne N. Haendiges, and Jennifer Sandson. 1997. Verb retrieval in aphasia. 1. Characterizing single word impairments. Brain and Language 56: 68–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnan, Joan. 2001. Lexical-Functional Syntax. Oxford: Blackwell, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza, Alfonso, and Argye Hillis. 1991. Lexical organization of nouns and verbs in the brain. Nature 349: 788–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoy, Olga, and Roelien Bastiaanse. 2010. Verb production and word order in Russian agrammatic speakers. Aphasiology 24: 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druks, Judit, and Brendan Stuart Weekes. 2013. Parallel deterioration to language processing in a bilingual speaker. Cognitive Neuropsychology 30: 578–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbro, Franco. 2001. The bilingual brain: Bilingual aphasia. Brain and Language 79: 201–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroqi-Shah, Yasmeen, and Arifi N. Waked. 2010. Grammatical category dissociation in multilingual aphasia. Cognitive Neuropsychology 27: 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filley, Christopher M., Gail Ramsberger, Lise Menn, Jiang Wu, Bessie Y. Reid, and Allan L. Reid. 2006. Primary progressive aphasia in a bilingual woman. Neurocase 12: 296–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garraffa, Maria, and Nino Grillo. 2008. Canonicity effects as grammatical phenomena. Journal of Neurolinguistics 21: 177–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goral, Mira, Monica Norvik, and Bård Uri Jensen. 2019. Variation in language mixing in multilingual aphasia. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 33: 915–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, David W. 2003. The neural basis of the lexicon and the grammar in L2 acquisition: The convergence hypothesis. In The Interface between Syntax and the Lexicon in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Roeland van Hout, Aafke Hulk, Folkert Kuiken and Richard Towell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Green, David W., Jenny Crinion, and Cathy J. Price. 2006. Convergence, degeneracy and control. Language Learning 56: 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grodzinsky, Yosef. 1990. Theoretical Perspectives on Language Deficits. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky, Yosef. 2000. The Neurology of Syntax: Language Use without Broca’s Area. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 23: 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosjean, François. 1998. Studying bilinguals: Methodological and conceptual issues. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 1: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Murray, and David J. Irwin. 2018. Primary Progressive Aphasia and Stroke Aphasia. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 24: 745–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, Brooke. 2023. Aphasia and Other Acquired Neurogenic Language Disorders: A Guide for Clinical Excellence, 2nd ed. San Diego: Plural Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hanne, Sandra, Frank Burchert, Ria De Bleser, and Shravan Vasishth. 2015. Sentence comprehension and morphological cues in aphasia: What eye-tracking reveals about integration and prediction. Journal of Neurolinguistics 34: 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzova, Pavlina, Manuel Carreiras, and Simona Mancini. 2022. Processing argument structure complexity in Basque-Spanish bilinguals. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Mireia, Agnés Caño, Albert Costa, Núria Sebastián-Gallés, Montserrat Juncadella, and Jordi Bayarri-Gascón. 2008. Grammatical category-specific deficits in bilingual aphasia. Brain and Language 107: 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, Mireia, Agnés Costa, Núria Sebastián-Gallés, Montserrat Juncadella, and Ramón Reñé. 2007. The Organization of Nouns and Verbs in Bilingual Speakers: A Case of Bilingual Grammatical Category-specific Deficit. Journal of Neurolinguistics 20: 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaezue, Gerald C., Ibraheem A. Salako, and Akinyemi T. Akinmurele. 2017. Selective Sentence Production Deficit in an Agrammatic Yoruba-English Bilingual Patient with Minor Stroke: A Case Study. Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science 7: 416–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambanaros, Maria. 2009. Investigating Grammatical Word Class Distinctions in Bilingual Aphasic Individuals. In Aphasia: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Edited by Grigore Ibanescu and Serafim Pescariu. New York: Nova Science, pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kambanaros, Maria. 2016. Verb and noun word retrieval in bilingual aphasia: A case study of language- and modality-specific levels of breakdown. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 19: 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambanaros, Maria, and Willem van Steenbrugge. 2006. Noun and Verb Processing in Greek–English Bilingual Individuals with Anomic Aphasia and the Effect of Instrumentality and Verb–Noun Name Relation. Brain and Language 97: 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Anthony Pak-Hin, and Brendan Stuart Weekes. 2011. Use of the BAT with a Cantonese-Putonghua speaker with aphasia. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 25: 540–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, Ekaterina, Mira Goral, Monica Norvik, and Brendan Stuart Weekes. 2019. What influences language impairment in bilingual aphasia? A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Miseon, and Cynthia K. Thompson. 2004. Agrammatic aphasic production and comprehension of unaccusative verbs in sentence contexts. Journal of neurolinguistics 17: 315–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, Aviva, Lia Pazuelo, Lian Kizner, Katy Borodkin, and Mira Goral. 2019. Language mixing patterns in a bilingual individual with non-fluent aphasia. Aphasiology 33: 1137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K. O’Brien. 2010. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 5: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, William Johannes Maria. 1989. Speaking: From Intention to Articulation. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen, Bonnie, and Laura L. Murray. 2008. Bilingual aphasia: A theoretical and clinical review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 17: 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, Alvaro, Margarida Rodrigues, Sónia Simões, Isabel Santana, and João Soares-Fernandes. 2010. The Portuguese who could no longer speak French: Primary progressive aphasia in a bilingual man. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 22: 123.e31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehri, Azar, and Shohreh Jalaie. 2014. A Systematic Review on methods of evaluate sentence production deficits in agrammatic aphasia patients: Validity and Reliability issues. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences: The Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences 19: 885–98. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, Michel. 2001. Bilingual and polyglot aphasia. In Language and Aphasia. Edited by Rita Sloan Berndt. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, Michel. 2004. A Neurolinguistic Theory of Bilingualism. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier, Sarah-Ève, Marion Fossard, and Laura Monetta. 2021. The efficacy of treatments for sentence production deficits in aphasia: A systematic review. Aphasiology 37: 122–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Hillary K. 2015. Agrammatic aphasia verb and argument patterns in Kiswahili-English spontaneous language. The South African Journal of Communication Disorders = Die Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Kommunikasieafwykings 62: E1–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Cynthia K. 2019. Neurocognitive Recovery of Sentence Processing in Aphasia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 62: 3947–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, David J., and Thomas G. Bever. 2001. Sentence Comprehension: The Integration of Habits and Rules. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, Micah D. J. Peters, Tanya Horsley, Laura Weeks, and et al. 2018. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, Michael. 2001. A neurocognitive perspective on language: The declarative/procedural model. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2: 717–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, Michael. 2005. A cognitive neuroscience perspective on second language acquisition: The declarative/procedural model. In Mind and Context in Second Language Acquisition. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 141–78. [Google Scholar]

- Verreyt, Nele, Louisa Bogaerts, Uschi Cop, Sarah Bernolet, Miet De Letter, Dimitri Hemelsoet, Patrick Santens, and Wouter Duyck. 2013. Syntactic priming in bilingual patients with parallel and differential aphasia. Aphasiology 27: 867–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, David P., and Gabriella Vigliocco. 2002. A semantic analysis of grammatic class impairments: Semantic representations of object nouns, action nouns and action verbs. Journal of Neurolinguistics 15: 317–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, Janet, Sue Franklin, and David Howard. 2004. Investigating the sub-processes involved in the production of thematic structure: An analysis of four people with aphasia. Aphasiology 18: 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, Anne, Janet Webster, and David Howard. 2015. Argument structure deficit in aphasia: It’s not all about verbs. Aphasiology 29: 1426–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilshire, Carolyn E., Carolina C. Lukkien, and Bridget R. Burmester. 2014. The sentence production test for aphasia. Aphasiology 28: 658–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, Sergio, Valentina Angeli, and Allesandro Tavano. 2011. Primary progressive aphasia in a bilingual speaker: A single-case study. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 25: 553–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).