A Portrait of Lexical Knowledge among Adult Hebrew Heritage Speakers Dominant in American English: Evidence from Naming and Narrative Tasks

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Heritage Speakers and Their Lexical Abilities

1.2. Hebrew Typology

1.3. Hebrew Speakers in the United States

1.4. Research Questions and Hypothesese

- How do Hebrew HSs compare on HL and SL vocabulary production?

- What HL non-target responses do Hebrew HSs produce and do they follow a pattern?

- What characterizes their HL narrative production?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Coding Schemata: MINT

2.4. Coding Schemata: Narrative

3. Results

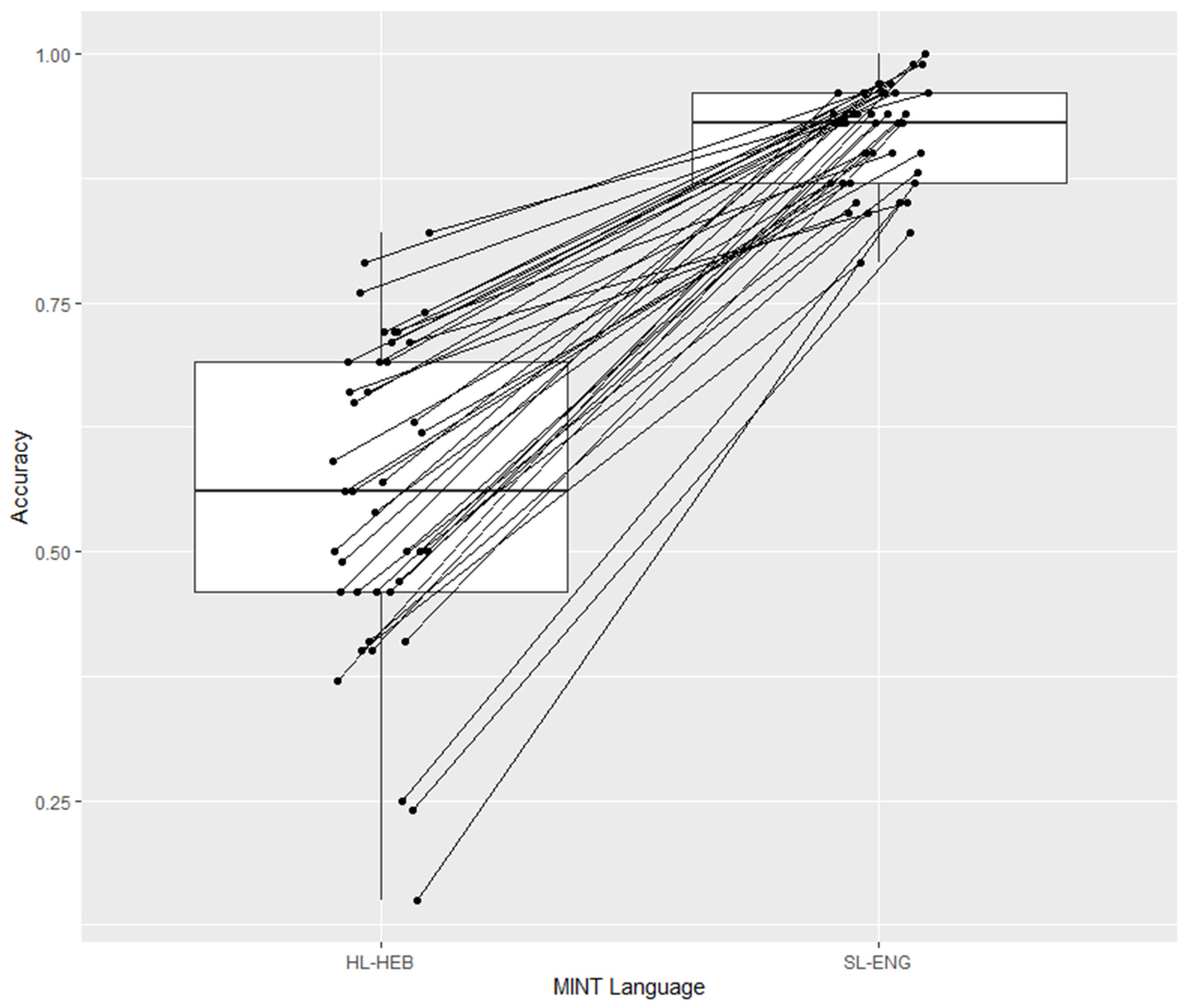

3.1. Quantitative Vocabulary

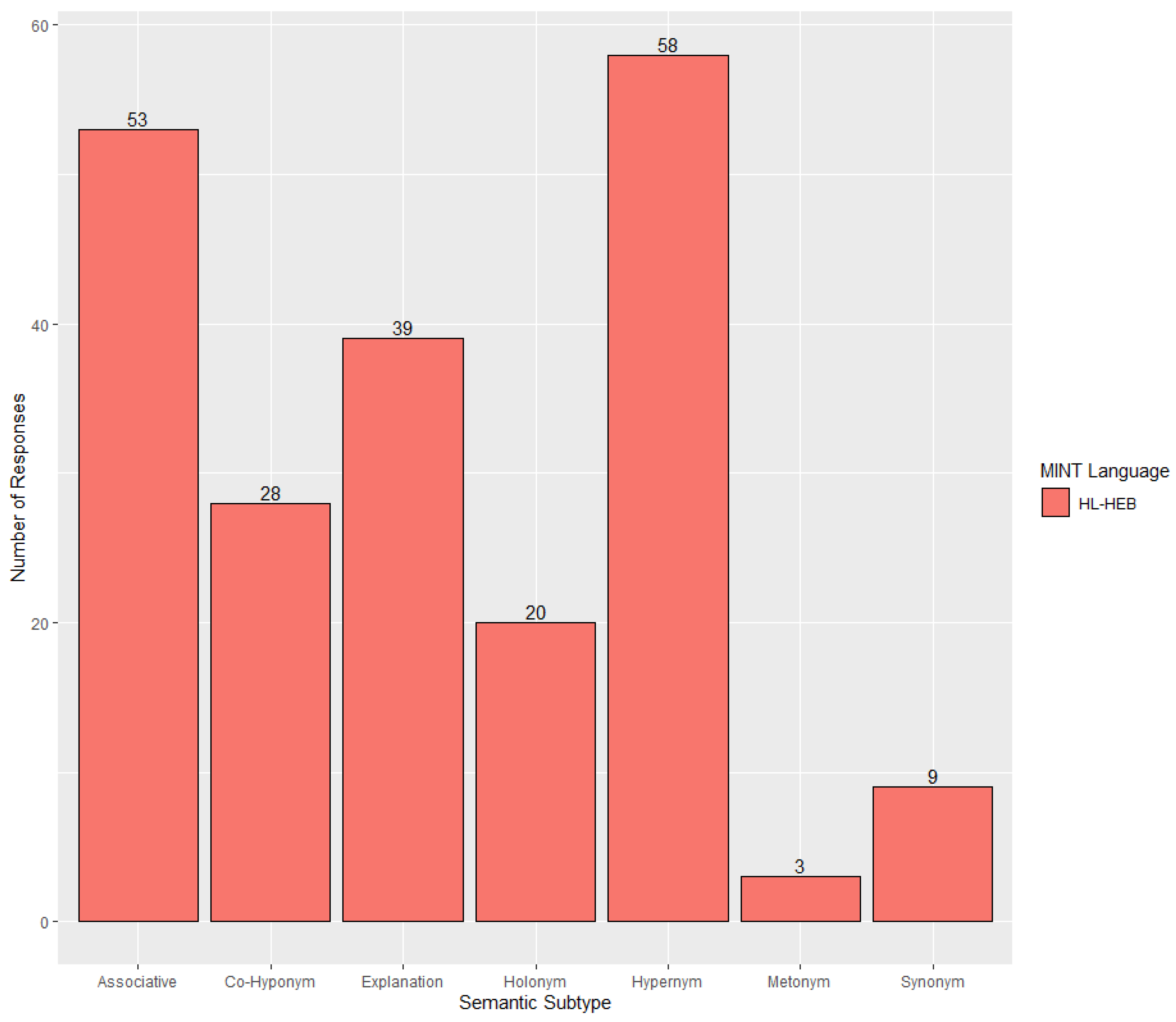

3.2. Non-Target Responses

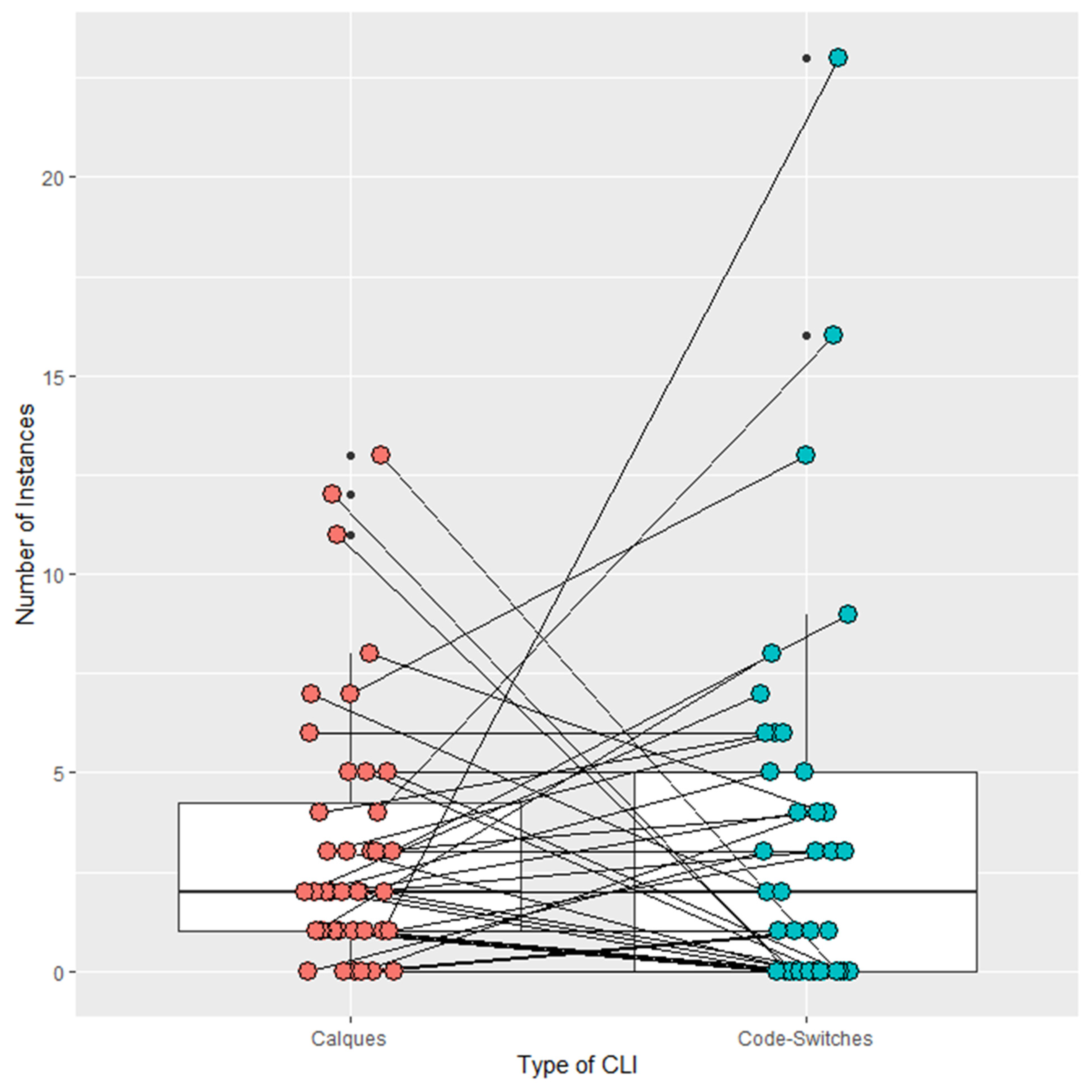

3.3. Narrative

- 1.

- ve- yotzet yanshuf I THINK yotze yanshuf‘and out comes.F an owl I THINK out comes.M an owl’

- 2.

- yesh lahem mishpaxa AW THAT’S CUTE‘they have a family AW THAT’S CUTE’

- 3.

- ha- kelev leyad ha- I HAVE THE WORD TREE ON THE TIP OF MY TONGUE THAT’S THE THING I SAY THIS WORD ON THE DAILY I DON’T KNOW WHY I’M FORGETTING IT BUT HE’S NEXT TO THE TREE ve- hem od mexapsim‘The dog next to the [English] and they are still looking’

- 4.

- ha- tzfardea yatz’a me- ha- GLASS JAR‘the frog came out of the GLASS JAR’

- 5.

- ve- pitom ex omrim OWL‘and suddenly how do you say OWL’

- 6.

- leyad ha- mashu shel dvorim I DON’T KNOW WHAT A BEEHIVE IS CALLED‘next to the something of bees I DON’T KNOW WHAT A BEEHIVE IS CALLED’

- 7.

- ve- az ha- BEES hem osim dvash ex korim lahem loh zoxeret OKAY ve- az ha- xarakim‘and then the BEES they make honey what are they called don’t remember OKAY and then the bugs’

- 8.

- hu *mitkasher la- tzfardea shelo‘he calls his frog’

- 9.

- eifo ha- tzfardea shelo *bifnim ha- etz‘where is his from inside the tree’

- 10.

- hem korim ve- *mistaklim la- tzfardea‘they call and look for the frog’

- 11.

- hem karu *bishvil ha- tzfardea‘they called for the frog’

- 12.

- im *davar al ha- rosh shelo‘with a thing on his head’

- 13.

- exad mihem *loh *afilu al ha- etz‘one of them not even on the tree’

- 14.

- hem kaasu *ito‘they were angry with him’

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Next Steps

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The case of Israeli Arabs living in the United States is particularly unique. While, like their Jewish counterparts, they may settle primarily in large metropolitan areas, their communities, experiences, and home language use are distinct. Therefore, they are beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 2 | The explanations for yaeh ‘dustpan’ included ha lemata shel ha matateh ‘the below of the broom’; kli shel zevel ‘tool of trash’; osef avak ‘dust collector’; metaateim im zeh ‘[people] clean with this’; and mashehu la nikayon ‘something for cleaning’. |

| 3 | Of the five examples provided for ‘correct root–incorrect formation,’ only the first, miftax, is a real Modern Hebrew word (meaning ‘part that can be opened’). |

| 4 | Only two of the 15 responses included a morpho-phonological error on a semantically related term. They were *maMSer instead of masmer ‘nail’ for boreg ‘screw’, and *tzanxENEt instead of *tzanxANIt ‘female paratrooper’ instead of mitznax ‘parachute’. |

References

- Altman, Carmit, Tamara Goldstein, and Sharon Armon-Lotem. 2017. Quantitative and qualitative differences in the lexical knowledge of monolingual and bilingual children on the LITMUS-CLT task. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 31: 931–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, Fatih, Jason Rothman, Grazia Di Pisa, and Roumyana Slabakova. 2021. Current Trends and Emerging Methodologies in Charting Heritage Language Grammars. In The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics. Edited by Silvina Montrul and Maria Polinsky. Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 545–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, Fatih, Tanja Kupisch, Diego Pascual y Cabo, and Jason Rothman. 2019. Terminology matters on theoretical grounds too!: Coherent grammars cannot be incomplete. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41: 257–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers: Opportunities and Challenges for Linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, Ruth A. 2003. Children’s lexical innovations. In Language Processing and Acquisition in Languages of Semitic, Rootbased, Morphology. Edited by Joseph Shimron. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 243–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, Ellen, and Gigi Luk. 2012. Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual adults. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Gigi Luk, Kathleen F. Peets, and Sujin Yang. 2010. Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism (Cambridge, England) 13: 525–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Evan Gary. 2009. The Role of Similarity in Phonology: Evidence from Loanword Adaptation in Hebrew. Doctoral dissertation, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Evan Gary. 2019. Loanword phonology in Modern Hebrew. Brill’s Journal of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 11: 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, Avital, Ram Frost, and Kenneth I. Forster. 1998. Verbs and nouns are organized and accessed differently in the mental lexicon: Evidence from Hebrew. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 24: 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, Philip. 2014. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Marta, and Anel Garza. 2018. The Lexicon of Spanish Heritage Language Speakers. In The Routledge Handbook of Spanish as a Heritage Language. Edited by Kim Potowski and Javier Muñoz-Basols. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Foygel, Dan, and Gary S. Dell. 2000. Models of impaired lexical access in speech production. Journal of Memory and Language 43: 182–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, Clara, and Natalia Meir. forthcoming. Lexical Production and Innovation in Child and Adult Russian Heritage Speakers Dominant in English and Hebrew. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. in preparation.

- Fullwood, Michelle, and Timothy O’Donnell. 2013. Learning non-concatenative morphology. Paper presented at the Fourth Annual Workshop on Cognitive Modeling and Computational Linguistics (CMCL), Sofia, Bulgaria, August 8; pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi, Khadijeh, and Frank Boers. 2017. Influential factors in incomplete acquisition and attrition of young heritage speakers’ vocabulary knowledge. Language Acquisition 24: 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Steven J. 2005. The Israeli Diaspora. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, Tamar H., Gali H. Weissberger, Elin Runnqvist, Rosa I. Montoya, and Cynthia M. Cera. 2012. Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish–English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hary, Benjamin H., and Sarah Bunin Benor, eds. 2018. Languages in Jewish Communities, Past and Present, 1st ed. Contributions to the Sociology of Language (CSL). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, vol. 112. [Google Scholar]

- IAC Impact Report. 2021. The Israeli American Council. Available online: https://www.israeliamerican.org/sites/default/files/files-attached-to-pages/iac-impact-2020–2021.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi. 2018. Factors of variation, maintenance and change in Scandinavian heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 447–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, Janne Bondi, and Signe Laake. 2015. On two myths of the Norwegian language in America: Is it oldfashioned? Is it approaching a written Bokmål standard? In The Study of Germanic Heritage Languages in the Americas. Edited by Janne Bondi Johannessen and Joseph C. Salmons. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, Olga, Miriam Minkov, Ekaterina Protassova, and Mila Schwartz. 2021. What kind of speakers are these? Placing heritage speakers of Russian on a continuum. The Changing Face of the “Native Speaker”: Perspectives from Multilingualism and Globalization 31: 155. [Google Scholar]

- Klapicová, Edita Hornáčková. 2018. Acquisition of meaning in bilingual children: Interference, translation and errors. Topics in Linguistics 19: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopotev, Mikhail, Olesya Kisselev, and Maria Polinsky. 2020. Collocations and near-native competence: Lexical strategies of heritage speakers of Russian. International Journal of Bilingualism. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1367006920921594 (accessed on 1 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2018. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 564–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laks, Lior. 2018. Verb innovation in Hebrew and Palestinian Arabic: The interaction of morpho-phonological and thematic-semantic criteria. Brill’s Journal of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 10: 238–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laks, Lior. 2019. Competing suffixes: Feminine formation of Hebrew loanwords. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 16: 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, Asher. 1990. Hebrew. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 20: 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jin Sook, and Sarah J. Shin. 2008. Korean heritage language education in the United States: The current state, opportunities, and possibilities. Heritage Language Journal 6: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbeth, Alessandra, Natsuki Atagi, Jessica L. Montag, Michelle R. Bruni, and Christine Chiarello. 2022. Assessing language background and experiences among heritage bilinguals. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 993669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, Mercer. 1969. Frog, Where Are You? New York: Dial Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Karla K., Robyn M. Newman, Renée M. Reilly, and Nina C. Capone. 2002. Semantic representation and naming in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 45: 998–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meir, Natalia, Susan Joffe, Ronald Shabtaev, Joel Walters, and Sharon Armon-Lotem. 2021. Heritage Languages in Israel: The multilingual tapestry with Hebrew threads. In The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics. Edited by Silvina Montrul and Maria Polinsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 129–55. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism. Re-Examining the Age Factor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2013. How “native” are heritage speakers? Heritage Language Journal 10: 153–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2000. The composite linguistic profile of Speakers of Russian in the U.S. In The learning and Teaching of Slavic Languages and Cultures. Edited by Olga Kagan and Benjamin Rifkin. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers, pp. 437–65. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2006. Incomplete acquisition: American russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 14: 191–262. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2008. Gender under incomplete acquisition: Heritage speakers’ knowledge of noun categorization. Heritage Language Journal 6: 40–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2018. Bilingual children and adult heritage speakers: The range of comparison. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 547–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2020. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2007. Heritage Languages: In the ‘Wild’ and in the Classroom. Language and Linguistics Compass 1: 368–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhilina, Ekaterina, Anastasia Vyrenkova, and Maria Polinsky. 2016. Linguistic creativity in heritage speakers. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 1: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, Christine Barth, Marjorie Nicholas, Rhoda Au, Loraine K. Obler, and Martin L. Albert. 1999. Verb naming in normal aging. Applied Neuropsychology 6: 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravid, Dorit. 1990. Internal structure constraints on new-word formation devices in Modern Hebrew. Folia Linguistica 24: 289–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebhun, Uzi, and Lilach Lev-Ari. 2013. Migration, Transnationalism, Diaspora, and Research on Israelis in the United States. In American Israelis. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ringblom, Natalia, and Galina Dobrova. 2019. Holistic Constructions in Heritage Russian and Russian as a Second Language: Divergence or Delay? Scando-Slavica 65: 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason, and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. 2014. A prolegomenon to the construct of the native speaker: Heritage speaker bilinguals are natives too! Applied Linguistics 35: 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scontras, Gregory, and Michael T. Putnam. 2020. Lesser-studied heritage languages: An appeal to the dyad. Heritage Language Journal 17: 152–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Lily, Qing Cai, and Tamar H. Gollan. 2021. Effects of cumulative language exposure on heritageand majority language skills: Spanish and Mandarin heritage speakers in the USA. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 11: 168–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, Veronika, and Natalia Terekhova. 2020. Russian-as-a-heritage-language vocabulary acquisition by bi-/multilingual children in Canada. Russian Language Studies 18: 409–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, John C. 1982. Accents of English: Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, Terrence G. 2007. The foreign language “crisis” in the United States: Are heritage and community languages the remedy? Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 4: 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Non-Target Response Type | Subtype | Definition | Example (Target–Non-Target) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic | Associative | A word related to the target by some association | kluv ‘cage’–kele ‘jail’ |

| Co-Hyponym | A member of the same category as the target | tapuax ‘apple’–tapuz ‘orange’ | |

| Explanation | Using a string of words to describe the target | megahetz ‘iron’–mashu xam le bgadim ‘something hot for clothes’ | |

| Holonym | A larger whole of the target part | tris ‘blinds’–xalon ‘window’ | |

| Hypernym | The wider category containing the target | nura ‘lightbulb’–or ‘light’ | |

| Metonym | Contents of the target | ken ‘nest’–beitzim ‘eggs’ | |

| Synonym | An equally acceptable term for the target | teka ‘plug’–shteker ‘plug’ (older term) | |

| Morpho-Phonological | A word or non-word morpho-phonologically similar to the target | xilazon ‘snail’–*zilaxon ‘snail’ | |

| Both Semantic and Morpho-Phonological | A response that is both semantically and morpho-phonologically similar to the target OR a morpho-phonological error on a word semantically related to the target | nura ‘lightbulb’–menora ‘lamp’ boreg ‘screw’–*mamser ‘nail’ (masmer) | |

| Cross-Linguistic | Borrowing | Responding in the SL | tavas ‘peacock’–peacock |

| Calque | Translating an SL term into the HL | mad laxatz ‘pressure gauge’–sha’on hafsaka ‘stop watch’ | |

| Mixing | Combining a root from the SL with HL morphosyntax | magrefa ‘rake’–merokek ‘agent that rakes’, from the English root ‘rake’’ | |

| Culturalism | Invocation of a cultural or religious term | pe’a ‘wig’–sheitel ‘wig’ (Yiddish); a term for the head covering worn by Orthodox Jewish women | |

| L3 | Responding in a language other than the SL or HL | matos ‘airplane’–avion ‘airplane’ (French) | |

| Phonetic | Producing an HL word based on the sound of the SL translation of the target | xilazon ‘snail’–snai ‘squirrel’ (sounds like hebraicized ‘snail’) | |

| Perceptual | A miscomprehension of the picture prompt | tzaif ‘scarf’–magevet ‘towel’ | |

| Unknown | No response | - | |

| Cross-Linguistic Subtype | Target | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Borrowing | richrach ‘zipper’ (x6) seren ‘axle’ tavas ‘peacock’ teka ‘plug’ nadneda ‘seesaw’ mad laxatz ‘pressure gauge’ | ziper bar pikok charger seesaw meter |

| Calque | mad laxatz ‘pressure gauge’ | sha’on hafsaka (lit) ‘stop watch’ |

| Culturalism | notza ‘feather’ pe’ah ‘wig’ | we just did it for bdikat xametz sheitel ‘head covering for religious Jewish women’ |

| L3 | matos ‘airplane’ | *avion (French) |

| Blending | magrefa ‘rake’ | *merokek |

| Phonetic | xilazon ‘snail’ | snai ‘squirrel’ |

| Morpho-Phonological Non-Target Response Pattern | Target | Response |

|---|---|---|

| General phoneme error | xetz boreg aniva mitznax | ketz bored aneva mitzax |

| Correct root–incorrect formation | maFTeaX maN’uL Be’ER BoReG PEaH | miFTaX miN’aL Ba’OR BeReG PaEH |

| Gender marking | nadneda salsala mazleg | nadned salsal mazleget |

| Total Number of Lexical Units, Tokens | Number of Unique Lexical Units, Types | Total Number of Target Lexical Units, Target Tokens | Number of Unique Target Lexical Units, Target Types | TTR | Target TTR | Number of Code-Switching Instances | Number of Calques | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (SD) | 379.5 (114.9) | 134.3 (34.4) | 368.8 (119.9) | 127.1 (37.3) | 0.36 (0.06) | 0.35 (0.06) | 3.5 (4.80) | 3 (3.25) |

| Range | 199–692 | 68–246 | 171–692 | 46–246 | 0.24–0.52 | 0.24–0.52 | 0–23 | 0–13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fridman, C.; Meir, N. A Portrait of Lexical Knowledge among Adult Hebrew Heritage Speakers Dominant in American English: Evidence from Naming and Narrative Tasks. Languages 2023, 8, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010036

Fridman C, Meir N. A Portrait of Lexical Knowledge among Adult Hebrew Heritage Speakers Dominant in American English: Evidence from Naming and Narrative Tasks. Languages. 2023; 8(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleFridman, Clara, and Natalia Meir. 2023. "A Portrait of Lexical Knowledge among Adult Hebrew Heritage Speakers Dominant in American English: Evidence from Naming and Narrative Tasks" Languages 8, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010036

APA StyleFridman, C., & Meir, N. (2023). A Portrait of Lexical Knowledge among Adult Hebrew Heritage Speakers Dominant in American English: Evidence from Naming and Narrative Tasks. Languages, 8(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010036