Abstract

This study provides a critical discussion on oral corrective feedback (CF) in the Spanish heritage language context by analyzing the language ideologies of both teachers and students relating to this everyday pedagogical practice. Despite the undeniable relevance of oral CF within the SHL language classroom, it is an area mainly studied within the field of SLA and, thus, primarily grounded in cognitive perspectives of the individual L2 learner and their subsequent language development. Drawing on scholarship that has long contested the discrimination that U.S. Latinxs face at the macro, meso, and micro-levels of society, this study interrogates and presents the core beliefs and values that legitimize the underlying asymmetrical power relationships propagated by oral CF. As critical paradigms continue to gain currency in the field of SHL education (e.g., critical language awareness), unmasking the various ways by which monolingual ideologies operate within language education is key to developing pedagogy that promotes Spanish language maintenance and, ultimately, dismantling such structures of domination. This study focuses on exploring the ideologies about oral CF by asking: (1) What language ideologies are prevalent in relation to participants’ conceptualization of oral CF? and (2) What are the instructor’s goals for oral CF? To answer these questions, this study analyzes interview data of a language instructor (n = 1) and SHL learners (n = 4) in an elementary-level, mixed Spanish course at a Hispanic-serving community college. The results show how the instructor utilized oral CF as a mechanism to enact dominant ideologies regarding SHL learners’ non-prestige varieties, while simultaneously advocating for an approach to learners’ varieties based on appropriateness. The instructor grounded her corrective practices in beliefs and values regarding the “deficiency” of SHL learners’ cultures and social categories that she considered to be the root causes of the “problem” that SHL learners spoke non-prestige varieties of Spanish. This study sheds light on the need to reexamine current L2-based oral CF taxonomies and teaching principles that do not account for the wide-ranging ways that corrective feedback becomes entrenched in educators’ culturally shared ideologies of language, learning and the learners themselves, and as normalized by the programmatic context wherein such practices are embedded. Finally, the study concludes by proposing several guiding considerations based on CLA to develop reflective practices for pedagogues to promote a consciousness of the ideologically charged nature of CF within the SHL learning context.

1. Introduction

Within the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA), oral CF is defined as one possible manifestation of form-focused instruction that provides negative evidence to the learner with an aim to expand their knowledge of the L2. Specifically, an Oral CF episode is an other-initiate repair of a learner’s output that typically involves several discursive moves: (1) a trigger (erroneous utterance), (2) an indication that an error has been committed by the learner via a feedback move (strategy employed), (3) the learner is provided the correct target language form (input), (4) metalinguistic information about the error is provided, or any combination of these three elements, and (5) sometimes includes learner uptake (learner self-correction; output) (Ellis 2009). Oral CF is a common practice utilized by many instructors to draw attention to inaccuracies in the target language and, therefore, this practice has received wide attention from both SLA researchers and language teachers alike. On the one hand, teachers are concerned with whether they should engage in corrective feedback and, if this is the case, where and how it should be enacted during instruction (Ellis 2017). On the other hand, SLA scholars are interested in testing theories of SLA, “which make differing claims about the effect that CF has on acquisition and which type is the most effective” (Ellis 2017, p. 3).

Another vein of related SLA research focuses on beliefs about CF, which are operationalized as “the attitudes, views, opinions, or stances learners and teachers hold about the utility of CF in second language learning and teaching and how it should be implemented in the classroom” (Li 2017, p. 145). Research on the construct of beliefs about CF provides insight on several important factors that are key to understanding its role and effectiveness in the classroom. Li (2017) points out that studies on beliefs include analyzing whether teachers are consistent on what they identify to be their preferences in providing CF and what they in actuality do in classroom practice. Additionally, beliefs about CF are also important because the effectiveness of it may depend on the learners’ receptivity of receiving CF. For instance, Sheen (2006) found a significant correlation between learner positive attitudes toward error correction and immediate gains after receiving CF than for those with less positive attitudes. Moreover, mismatches between learners’ expectations and teachers’ beliefs about CF may have an impact on dissatisfaction and ultimately affect the motivation to learn a language (Li 2017).

Despite its relevance as both a theoretical and practical teaching issue, there is a dearth of empirical research on oral CF beliefs within the context of Spanish Heritage Language education. To address this gap in the field, the present study draws upon Loza’s (2019, 2022) notion of ideologically charged oral CF to examine the underlying beliefs and value systems that mediate oral CF. Instead of focusing solely on attitudinal data, this study proposes that theoretical and practical notions of CF within the SHL field must critically account for the asymmetrical power relationships and real-world consequences of employing error correction on minoritized language learners. Because SHL learners and the varieties they speak have historically faced contempt within language education, it is important to gain a nuanced understanding of CF that reaches beyond the individual learner and their subsequent cognitive language development (Razfar 2010). Theorizing oral CF must be approached in a way that acknowledges and respects the decades-long advocacy of the SHL field to dismantle the subtractive curricular practices that disparage U.S. Spanish. As such, this study proposes that the construct of CF within the SHL context must be viewed as an index of the teachers’ language ideologies, which are embedded within a larger institutional and societal context. Therefore, this qualitative study explores the multilayered values and beliefs that critically underpin and shape both instructor and learners’ understanding, expectations, and learning objectives that involve CF practices to answer the complex, moral and broad question: How is the practice of oral CF meaningfully different for minoritized students?

2. Varying Perspectives on Oral CF Beliefs

Beliefs on Whether Error Should Be Corrected

Several quantitative studies demonstrate the general tendency that students view oral CF positively as well as an important element in the language learning process (e.g., Agudo 2014; Loewen et al. 2009; Schulz 1996; Sheen 2006, among others). In an early survey study by Schulz (1996), learners (n = 340) reported having positive attitudes toward negative feedback and grammar instruction. Specifically, 90 percent of the student participants indicated that they liked to have their spoken errors corrected and 94 percent disagreed with the statement, “teachers should not correct students when they make errors in class”. More recently, Agudo (2014) found that, out of a sample size of 185 Spanish EFL student respondents, a majority disagreed with the notion of not providing students with corrective feedback (88.44%). Although such data may depict a strong tendency in favor of CF, beliefs about CF are not uniform across both learner and teacher groups.

In a landmark study, Loewen et al. (2009) developed and implemented a questionnaire consisting of 37 Likert-scale items and four open-ended prompts to investigate L2 learners’ beliefs regarding grammar instruction and error correction. The study had a total of 754 ESL and FL participants from various levels. The results pointed to two main findings: (1) learners generally held positive beliefs about grammar instruction and error correction and (2) error correction was viewed as a separate category from grammar instruction by the participants, “whereas researchers might view error correction as a type of focus on form and, thus, a type of grammatical focus” (Loewen et al. 2009, p. 101). Moreover, the researchers noted variation among the different types of learners. ESL learners were “less convinced about the need for grammar instruction and error correction and were more enthusiastic about improving communicative skills than foreign language learners” (Loewen et al. 2009, p. 101). The researchers attributed this difference to the amount of grammar instruction in the learners’ current or past L2 classes that might have caused their rejection of CF.

SLA scholarship on beliefs about CF practices brings attention to several important considerations regarding its complexity as a construct. While some learners might not always view corrective feedback or studying grammar positively, many do in fact regard CF as being essential for mastering a second language. Additionally, Li (2017) points out that “the importance of investigating CF beliefs also lies in the fact that it is an independent construct that is distinct from beliefs about other aspects of language learning” (p. 143). Because learners view CF as being separate from grammar instruction, research must engage with beliefs about CF to gain a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of form-focused instruction. Moreover, CF can also be utilized for learners’ pronunciation, lexicon and pragmatics, which makes this construct relevant for various aspects of language teaching.

Complementary studies that explore teacher beliefs regarding CF have reported data to suggest that its acceptance is not always as strong when compared to learners’ attitudes. For instance, Schulz (1996) found that out of 92 teacher participants only 34 percent agreed that students should be, in general, corrected if they make an error in the target language. The researcher also found differences among teacher groups wherein ESL teachers were less enthusiastic about oral CF compared to other groups of teachers. In a related study, Rahimi and Zhang (2015) observed variability among different teacher groups by comparing experienced teachers with novice teachers to understand how their cognitions about teaching informed their classroom practices. Rahimi and Zhang showed that experienced teachers scored the statement “students’ spoken error should be corrected” higher than less experienced teachers. The researchers noted that “…both groups of teachers agreed with correcting students’ error in oral communication…the experienced teachers, however, believed in the importance of providing CF to a much greater extent than novice teachers did” (p. 115). They concluded that as teachers gain more classroom teaching experience, they “value” the gains in students’ interlanguage and acknowledge the role that CF plays in its development. In contrast, novice teachers drew upon their own language learning experiences and hesitation to harm learners’ motivations and self-esteem. Both teachers’ and learners’ attitudes toward CF may vary depending on individual experience and the learning context as well as whether the teachers focus on accuracy or fluency (Li 2017). The studies reviewed show how the field of SLA utilizes Likert-scale metrics and open-ended questions to elicit cognitive, affective and behavioral aspects of beliefs about CF from both students and teachers.

3. Overview of CF within the Field of SHL Education

3.1. The Eradication Approach

Whereas SLA scholarship draws upon social psychology to research beliefs about CF, SHL education has explored the construct of “error correction” through a sociolinguistic lens. Since the beginning of the SHL field, researchers have been searching for ways to honor and respect SHL learners’ varieties on account of the discriminatory treatment that Latinx students have historically faced within Spanish language education (e.g., Rodríguez Pino 1997; Valdés 1981; Villa 1996). During the first wave of the SHL field, scholars engaged in advocacy of the need to develop “theories, pedagogical principles, and curricular interventions that are distinct from those of foreign language education” (Beaudrie and Loza 2022, p. 1). This effort to shift away from traditional teaching models was, in part, based on early scholars’ own personal experiences and professional observations that drew attention to that eradicationist instructional and curricular practices that SHL learners faced in Spanish language courses (e.g., Rodríguez Pino 1997; Sánchez 1981; Valdés 1981). Known as the eradication approach, teachers utilized grammar instruction to identify the extent to which each learners’ bilingual varieties deviated from the accepted norm and to erase all undesirable linguistic features from the students’ repertoire (Valdés-Fallis 1978).

3.2. The Construct of Error Correction and Minoritized Learners

According to Valdés (1981), the primary objective of the eradication approach was to teach “standard” Spanish under the guise of helping students gain access to success, acceptance, and achievement by “freeing” themselves of the wrong dialect features (p. 81). Within this philosophy, early SHL scholars identified the construct of error correction to be a core mechanism whereby educators sought to achieve the subtractive learning objectives of the eradication approach. Discussions regarding error correction included interrogating the various ways that this practice was embedded explicitly within grammar instruction and learning materials. Specifically, SHL learners were assigned se dice/no se dice lists and were subjected to grammar drills to eliminate undesired morphological, phonetic, and lexical features that were considered to be part of “vulgar” Spanish (Bernal-Enríquez and Hernández-Chávez 2003; Rodríguez Pino 1997; Rodríguez Pino and Villa 1994). Importantly, subtractive teaching models are founded upon dominant language ideologies, which are defined as the values and beliefs speakers have about “language generally, specific languages or language varieties, or particular language practices and ways of using language” (Leeman 2012, p. 43). Hegemonic ideologies are reproduced in multiple levels of society, including educational institutions, wherein the lived linguistic and cultural knowledge of marginalized learners is often disregarded as being academically legitimate and worthy (Leeman 2010). Spanish language programs enact such disenfranchisement by devaluing learners’ varieties in the classroom often by prioritizing the teaching of the so-called “standard” variety. As such, understanding how such mechanisms operate within educational spaces gleans light on the links between language ideologies and specific instructional practices such as oral CF.

Despite error correction being a salient and contentious issue within SHL education, past research has mainly reported anecdotal evidence of this practice; hence, the distinction between “error correction” and the more formal SLA construct of oral CF. The terminologies used (i.e., error correction vis-à-vis oral CF) also distinguishes between diverging approaches to corrective feedback that are grounded in two distinct theoretical traditions of Spanish language education. The field of SHL has viewed this construct through a moral lens that questions its complicit role within subtractive educational models, whereas SLA has engaged with oral CF in a quest to understand and enhance the language acquisition process. Moreover, many SHL scholars remain cautious of oral CF given its potential to shape SHL learners’ classroom experiences in potentially negative ways.

Although empirical evidence on oral CF is scarce, related studies on language ideologies within Spanish language programs provide significant findings that show how instructional and larger programmatic practices can enable subtractive orientations toward SHL learner Spanish. Lowther Pereira (2010) documents how a pedagogically trained SHL instructor corrected SHL learners in a university-level class: “Students who used nonstandard forms in speech, whether before the class started in informal conversation or during classroom discussions, were corrected and instructed to use standard forms” (Lowther Pereira 2010, p. 212). The targeted lexical items were students’ use of papel instead of ensayo and moverse instead of mudarse. Additionally, the instructor would also mock such lexical variants by utilizing humor to illustrate their incorrectness by dancing or using gestures. As the researcher states, “such humor can sometimes be humorous only for the person in the position of authority… [for] students it can, instead, be real source of embarrassment or shame” (Lowther Pereira 2010, p. 218). In a survey of 151 university-level SHL learners, Ducar (2008) showed that 91% reported that their instructors corrected their Spanish in class and, in fact, 96% preferred to have their Spanish corrected. These results suggest that the learners had internalized stigmas about their Spanish and that, perhaps, “students simply perceive the classroom as a learning environment, and as such, expect to be corrected when deemed necessary by the figure of authority” (Ducar 2008, p. 424). Nonetheless, the participants unanimously reported that the Spanish they used was respected by their instructors and, the qualitative data, also elucidated the “tender manner” with which such correction was viewed as being imparted to them. The participants described their instructors’ corrections as gentle, helpful, and respectful, which highlights that the “teachers’ style of imparting such correction has served to create a safe and resultful learning environment” (Ducar 2008, p. 425). These findings contribute invaluable data that evidence a complex and dynamic interconnectedness between corrective feedback and language ideologies.

3.3. SHL Approaches to Language Variation

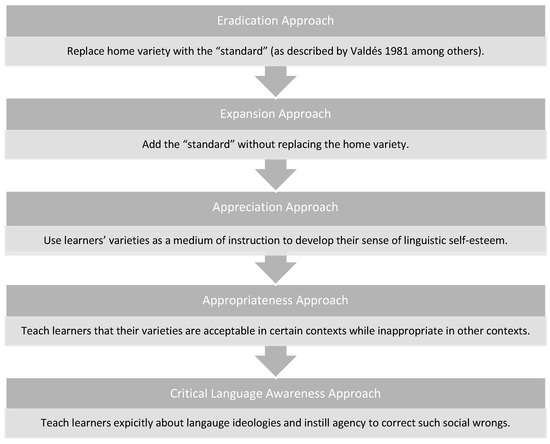

Understanding prior research findings on SHL language ideologies requires situating them within the larger philosophical orientations that currently guide how contemporary SHL programs and educators approach learners’ varieties in the classroom. Over the years, alternative philosophies to the eradication approach have emerged to overcome the educational disparities that have long impacted SHL learners’ class experiences negatively. Beaudrie (2015) describes these differing approaches as a taxonomy that consists of the expansion approach (Acevedo 2003; Kondo-Brown 2003; Porras 1997; Sánchez 1981), the appreciation approach (Carreira 2000), the appropriateness approach (Guitiérrez 1997; Samaniego and Pino 2000; Potowski 2005) and the critical language awareness approach shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Approaches to SHL non-prestigious varieties (based on Beaudrie 2015).

Loza (2022) argues that this taxonomy elucidates how these “orientations diverge in the extent and manner to which they explicitly engage with the socio-politics of SHL language teaching, which has larger implication for whether oral CF functions to reinforce linguistic domination” (p. 123). Furthermore, these differing philosophies on how to situate the Spanish spoken by SHL learners in the classroom are rooted in a much larger debate about how to reconcile the teaching of a prestige variety with respect for student varieties. On the one hand, experts agree that U.S. Spanish––understood as being inherently valid–– and learner identities and cultures are integral to building a quality SHL curriculum. On the other hand, the language classroom is also conceived as a space for the “learning” of Spanish which typically hinges on the so-called “standard” (Beaudrie 2015). It is within this dialectic that certain philosophies such as appropriateness become a source of debate within the field as well as the contradictive nature of specific instructional practices such as error correction. Although the SHL field has yet to solve such contradictions, this study utilizes this above-mentioned taxonomy to gain a better picture of the underlying philosophical properties that guide the study’s participants’ beliefs and values about SHL varieties and the goals for developing SHL learners’ varieties through particular teaching practices such as oral CF. Critical language awareness is a philosophy that provides a framework to contest hegemonic language ideologies within Spanish language education by prioritizing and centering learners’ social and linguistic experiences in the classroom (Beaudrie et al. 2019, 2021; Holguín Mendoza 2018; Leeman 2005; Martínez 2003). As a pedagogical approach, CLA provides educators with the knowledge and tools to render the hierarchical power inequities embedded within language legible to SHL learners, which are invaluable for encouraging them to becoming advocates for social change; therefore, this study draws upon CLA not only to name the ideological mechanisms that are problematic for SHL learners, but also to explore what is pedagogically possible by engaging with students’ classroom experiences.

As this review shows, the decisions that language programs and instructors take with respect to their SHL learners’ varieties have underlying ideological implications; therefore, the evidence suggests that instructional practices such as oral CF can potentially become an index of language ideologies rooted in the “teachers’ ideas, perceptions, and expectations of language, learning and the speakers themselves” (Razfar 2010, p. 14). The present study is the first of its kind to attempt to uncover the beliefs and values that underpin oral CF through a rigorous qualitative analysis that is systematic rather than solely anecdotal. Furthermore, this study contributes to SHL education and research by taking a socio-politically situated perspective on this controversial instructional practice.

4. Study

4.1. Focal Participants

The researcher conducted a two-month qualitative study of an Elementary-level Spanish course at a Hispanic serving community college in Arizona. The language program where the study took place did not offer specialized SHL courses to their sizable Latino student community. As Table 1 shows, the Spanish 101 course that served as the research site for this study had a total of four SHL learners and twelve L2 learners enrolled.

Table 1.

SHL Participant Language Background Information.

The majority of the focal SHL student participants reported learning Spanish as their first language from birth with the exception of Petra who was a receptive learner of Spanish. The instructor of the course originated from Colombia and moved to the U.S. to pursue an advanced graduate degree in phycology.

Looking at Table 2, Belinda’s 50 years of experience primarily comes from teaching in Colombia. The participant studied both her B.A. and one of her M.A.’s in Latin America and had advanced schooling in education-related fields. She began to teach in the U.S. after finishing graduate school and has lived in Arizona for 10 years. In that time, Belinda secured a part-time teaching position at the community college teaching one class as well as tutoring Spanish students. Importantly, she reported not having prior professional development in SHL pedagogy.

Table 2.

Instructor Background Information.

4.2. Research Instruments

This study draws on interview data from a larger research project as its main source of evidence to address the following research questions:

- What language ideologies are prevalent in relation to participants’ conceptualizations of oral CF?

- How does the instructor define an SHL error?

- What is considered to be “good” CF for Spanish heritage language learners according to the instructor?

- What are the instructor’s goals for oral CF?

- How does this converge with language ideologies?

To answer the research questions, this study took a dual focus approach that consists of two main units of analysis. The first level of data focused on ideologies about SHL learners and the Spanish they speak, and the second level considered the beliefs and values expressed by participants regarding oral CF practices. The instructor participated in a total of five semi-structured interviews, whereas the student participants were interviewed twice. Furthermore, the interviews with the student participants were conducted at the beginning of the research study and toward the end of the semester and the teacher was interviewed weekly. As such, the researcher was able to follow up and clarify with the participants on topics relating to CF during these multiple interviews.

The data were collected during the Spring 2018 semester beginning in March until the end of April before final exams. As part of the larger project, the researcher engaged in classroom observations that included ethnographic field notes as well as audio recordings of language instruction to document instances of oral CF episodes; however, this study only presents partial data specific to the instructor’s and student beliefs about CF to address the present research questions. To gain a deeper understanding of the construct in question, the interview protocol was constructed by first developing an interview matrix so that the thematic interview questions were in alignment with the current research questions (Kvale and Brinkmann 2015). The primary domains of the interview content and the types of data needed to fully address the research questions were outlined within the matrix. Further, the interview questions addressed beliefs about language learning, language use, U.S. Spanish, teaching philosophies, SHL learner needs, difficulties in teaching SHL learners, mixed courses, and beliefs relating to oral CF, etc. Each interview lasted between 45 to 120 min (15 h of total recorded audio time). The interviews were transcribed and coded utilizing the NVivo 12 qualitative software. The first phase of the coding process involved data reduction of the recorded audio to focus the analysis on the current research questions. The second phase of the qualitative analysis coded the interview data by utilizing a schema. The coding schema was specifically designed to firstly categorize the discursive articulations relating to notions of oral CF practices, SHL learners, and their language varieties which, in turn, were condensed into focused codes, and to then develop themes. The coding was performed iteratively (Maxwell 2013) in conjunction with interpretations of the ethnographic field-notes (Emerson et al. 2011) and analytic memos (Marshall and Rossman 2016) to pinpoint emerging themes on oral CF within the context of the current research questions. After the organization of the data was complete, the final step of the analysis involved the study’s interpretive framework. To uncover dominant language ideologies, the data were carefully analyzed through a Critical Discourse Studies approach to interpret and contextualize the various potential discursive devices that shaped the participants’ beliefs about oral CF, namely, pronouns, verbs to denote processes, metaphors, diminutives, allusions, evaluative attributations, quotes, quotatives and adjectives (van Dijk 2016; Reisigl and Wodak 2016). Critical discourse analysis provides a powerful lens to uncover how educational systems “meld students into knowledgeable citizens” (Ducar 2006, p. 43). Fairclough’s (2010) three-dimensional dialectical model illustrates how an analysis of micro-level discursive practices, events and texts can lead to uncovering how ideologies—rooted in relations of power and struggles over power—mediate wider social and cultural structures, relations and processes. Thus, discourse is constitutive of the social world but is also constituted by it; discourse is a form of social practice that not only contributes to the shaping and reshaping of social structures, but also reflects them.

5. Findings

The participants’ ideologies regarding their conceptualization of oral CF are explored in the following interview excerpts. First, the teacher participant data will be presented thematically and discussed, followed by the SHL student data. The excerpts illustrate how the instructor, Belinda, prioritized the teaching of a privileged variety of Spanish by touting that certain language forms are inherently more educated and standard. Moreover, the data also reveals how her value judgments and beliefs about the Spanish spoken by the SHL learners intersected with other social structures (e.g., ethnicity and social class), which in turn shaped what Belinda perceived to be “good” oral CF practices for SHL learners. The student data provides evidence that they did not always adhere to hegemonic ideologies outright and may contest deficit views of their varieties; thus, highlighting how the classroom space may also be a site of conflicting student–teacher ideologies. The following excerpts contain bolded key words and phrases to help guide the reader’s attention throughout the analysis.

5.1. Theme 1: The Problem with SHL Learners’ Varieties

Upon interviewing Belinda, it became clear that the answer to the question “what is an SHL error” lay in her deficit ideologies of the Spanish spoken by the SHL learners as well as of the local community that they belonged to. The data show a common theme that centers on the standard language ideology, which creates boundaries between groups of speakers based on both the preferred language forms as well as on the speakers’ social identities.

Excerpt 1: “what is an SHL error?”

| Belinda: No olvide que yo clasificó a los alumnos [SHL] es por la cultura, yo hablo con un estudiante y yo de una vez sé, cómo es el lugar [de donde viene], porque la forma como la persona hable ahí está la educación que tiene. | Belinda: Don’t forget that I classify [SHL] students by their culture, I speak to a student and I know, what is the place [they come from] like, because the way a person speaks is the education that they have. |

| Utilizan [los estudiantes SHL] demasiadas palabras, yo sé que el pueblo las usa, pero eso no es lo normal…pero yo todos los días en las clases digo, “Yo puedo decir esa palabra, pero esa no es la correcta”, ese no es el nivel de español que queremos enseñarle. | They [SHL learners] use too many words, I know that the el pueblo uses, but that is not the norm…but every day in class I tell them, “I can say that word, but that is not the correct one”, that is not the level of Spanish that we want to teach them. |

For Belinda, a central theme in her interview related to how the SHL learners’ Spanish was problematic and inappropriate for the instructional context. Specifically, she deemed their Spanish as inappropriate because it indexed the students to non-privileged social categories. As the participant noted, the SHL learners’ Spanish contained “demasiadas palabras” that should not be used in the classroom because they are associated with “el pueblo”, a characteristic that is not associated with the standard “norm”. Belinda constructed such connections by calling upon social class distinctions to frame what was considered, in her view, as being normal, educated, and aesthetically pleasing Spanish, which is often associated with dominant groups of speakers (Leeman 2012). Belinda also pointed to the SHL learners’ “cultura” as a euphemism to place them within a linguistic hierarchy. This euphemism was also constructed as a foundational element responsible for shaping the learners’ Spanish and, ultimately, the root cause of her professional burden to sanitize their repertoires. As Bernal-Enríquez and Hernández-Chávez (2003) remind us, many SHL learners have a “campesino” or “obrero” background; therefore, the slight against their varieties by educators is simultaneously disparaging of the socioeconomic status of their families (p. 107). Further compounding Belinda’s negative views of her SHL learners Spanish was the fact that she pointed to local “Mexican” Spanish as being a principal cause of the students’ academic challenges.

| Belinda: Es que el problema que tenemos aquí en los Estados Unidos es por la frontera, porque ese idioma que tenemos aquí es idioma mexicano. | Belinda: It’s because the problem we have here in the United States is because of the border, because that language that we have here is a Mexican language. |

| Por ejemplo, dicen “Órale” o “Asina” y yo pues yo les dije, “No, no es asina, es así es- pero no asina”. Entonces, yo les describo la palabra, yo le descompongo la palabra y les explico por qué. | For example, they say “Órale” or “Asina”and I well told them, “No, its not xi, it is like that but not asina”. So I describe the word, I pull apart the word and I explain to them why. |

Belinda used perspectivization to position her involvement in the teaching of such ‘normal’ Spanish while simultaneously also creating an evaluation of her SHL learners’ Spanish. Specifically, Belinda used quotes and quotatives as discursive devises to not only position herself but also her point of view with respect to the Spanish spoken by the learners: “…choices about how to create a representation of another voice that fits the purposes of the present discourse” (Johnstone 2018, p. 60). Belinda quoted her own use of explicit CF that clearly signals to the learner that an error has occurred and further claims to provide “metalinguistic” commentary of why such stigmatized forms are wrong. The contrastive nature of Belinda’s description of CF echoed the se dice/no se dice practices of the eradication approach by clearly marking a boundary between what is deemed appropriate and inappropriate Spanish.

These findings add more evidence that supports the need to adopt CLA-based teaching models, which are necessary for educators working with student communities that have historically faced institutional erasure. As the evidence shows, sociolinguistics training is invaluable for language instructors to understand their SHL learners’ varieties; a foundation element to practicing CLA (Bessette and Carvalho 2022; Carvalho 2012). Additionally, instructors must also have the knowledge to contextualize language variation within the broader societal issues of race and class that are indispensable to serving minoritized students (Lacorte and Magro 2022).

5.2. Theme 2: Spanglish Is Awkward but It Is Mine

The SHL participants in this study were crucial to gaining a nuanced understanding of language ideologies in the classroom. In their interviews, Myriam, Petra, María and Reina expressed varying opinions about U.S. Spanish. The common theme found among the learner participants were both supportive of their own varieties, but also disparaging of Spanglish.

Excerpt 2: “Spanglish”

| Myriam: | I don’t like Spanglish. Like I like it, but I just feel like, like, I don’t know, I just feel like either you’re gonna talk one language or the other one, because me traba…, I just feel like it’s awkward I don’t know. To me it’s a kind of weird. |

| Petra: | Because most my family is from here; all they talk is Spanglish. They don’t talk the correct form of Spanish. So, when I come into class and hear words that they’ve used differently, it kind of confuses me. |

| María: | With my family we talk more in Spanglish ‘cause like my brothers and sisters, they don’t know as much Spanish. Everyone’s in my family speaks slang… I feel like it’s kind of easier because like if you talk to someone like you don’t know kind of, but like you have a connection as soon as she started speaking. Spanglish. You have the best of both worlds from English and Spanish. |

| Reina: | Personally, I like Spanglish. I use it all the time…I think actually lots of Mexicans actually do like Spanglish…Mexicans that come over here, do speak a lot of Spanglish because they try to use the little English they know and like introduced that into their own vocabulary. |

The mixed sentiments regarding U.S. Spanish are reflective of a monolingual ideology that downplays the value of U.S. Spanish. In Myriam and Petra’s excerpts, descriptive words like “awkward”, “weird”, and “slang” evidence their internalization of such dominant ideologies that are rampant throughout educational settings and U.S. Spanish-speaking communities; however, María and Reina overtly liked Spanglish for its real-world practicality and shared the observation that even Mexican immigrants also incorporate the English they learn into their own language practices. In particular, their critical metalinguistic commentary in support of Spanglish demonstrates the multiplicities of language ideologies wherein they become a site of contention and conflict as well as resistance to hegemony (Kroskrity 2010). Nonetheless, the students’ own deficit views of U.S. Spanish may only serve to reinforce the ideological mechanisms hidden within explicit language instruction and practices such as CF. As mentioned earlier, CLA is currently the most effective teaching model for rendering legible to SHL learners the ideological mechanisms that emerge from and propagate hierarchical power inequities. Developing SHL learners’ critical metalinguistic awareness is important for supporting their sense of linguistic pride (Martínez 2003) and, most importantly, for promoting heritage language maintenance. As Beaudrie and Wilson (2022) argue, HL maintenance is unattainable unless HL students become cognizant of the ideologies and practices that shape their language experiences.

5.3. Theme 3: “Good” CF for SHL’s Is Clear and Direct

In addition to Belinda sharing her problematic awareness of the SHL learners’ cultures and language abilities, she also described her preferences and style for practicing oral CF. The thematic patterns found relate to the level of professionalism and “normative” language practices expected by Belinda in her classroom. Understanding what “good” CF means for the instructor was important for identifying how her ideologies about the SHL learners’ varieties ultimately informed how she employed this teaching practice.

Excerpt 3: “good corrective feedback”

| Belinda: Yo pienso que un profesor tiene que ser claro y también sobre todo clarificarle al estudiante que es lo que quiere…el estudiante termina por no saber que en realidad que-como son las ah-condiciones-para la evaluación-entonces el maestro tiene que ser directo, claro y persistente…con el estudiante sin humillarlo, ni menospreciarlo… | Belinda: I think that a teacher needs to be clear and also above all else clarify to the student what it is that you want…the student ends up not knowing what how- are the ah-conditions for the evaluation- and so the teacher has to be direct, clear and persistent…with students without humiliating them, nor underestimate them… |

Belinda pinpointed three CF qualities that a teacher must exercise: being clear, direct, and persistent. She reflected upon the “incontrollable” nature of oral CF as an on-line, in the moment—sometimes instinct-driven (Ellis 2009)—attempt to draw learners’ focus onto an “error”. She noted that teachers can unwittingly harm students and, therefore, CF must be clear, direct and persistent to avoid any problems between the educator and the pupil. As Belinda reasoned, these qualities prompt students’ awareness of teacher expectations and the evaluative criteria pertinent to the feedback given, which avoids any possibility of miscommunication. Belinda showed concern for the affective aspects of oral CF. In particular, she argued that teachers must have the know-how to provide CF without “humiliating” or “looking down” on learners; a common sentiment among language teachers (Lyster et al. 2013; Li 2017).

| Belinda: …[si] el maestro está negativo… va a dañar eh a la-la parte emocional del estudiante y también el estudiante…puede entender esa corrección como una cosa negativa. | Belinda: …[if] the teacher is negative…they can damage um the-the emotional part of the student…the student can interpret that correction like something negative. |

| Yo los corrijo igual que a todos, siempre tratando de explicarles, cuáles son las ventajas de tener un lenguaje correcto -porque a veces… tienen [los Latinos] un vocabulario distinto y o un nivel más bajo- de no es normal. Entonces, les explico que la necesidad de mejorar el lenguaje… Entonces, yo les explico que estamos en la clase a un nivel más profesional y por consiguiente es necesario aprender el idioma correcto, no solamente hablado, sino escrito. | I correct everyone the same, I always try to explain to them, what are the advantages of having a correct language because sometimes…they [the Latinos] have a distinct vocabulary or a level that is lower that the norm. So…I explain to them the need to improve their language…So, I explain to them that we are in class which is a more professional level and, therefore, it is necessary to learn the correct language, not only spoken, but also written. |

Continuing with the second point, she described herself as utilizing CF practices that were respectful of the SHL learners’ varieties and clarified that for educators, the intent of providing feedback is purely grounded in the educational pursuit of learning language. Opposite to the philosophy of CLA, the participant painted a picture of how CF was, in fact, a neutral language learning practice despite recognizing that the SHL learners may view the CF as offensive. Importantly, Belinda explained her CF practices as providing a “metalinguistic” commentary that tells students why they should strive to develop a “polished” and “professional” variety of spoken and written Spanish. The data illustrate how Belinda’s self-reported provision of oral CF contained ideologically charged discourses that accompanied the corrective strategy. Typically, within an L2 context, a metalinguistic explanation is regarded as purely linguistic in nature, whereas in this context it became a subjective appraisal of the worth of the learners’ Spanish and of themselves (Loza 2022).

5.4. Theme 4: CF Is Confusing

The SHL participants did not support Belinda’s assertions of her ability to impart transparent oral CF. In fact, overall, the participants shared that they did not gain much from their teacher’s CF practices.

Excerpt 4: “I still don’t know what I did wrong”

| Reina: | Usually she [Belinda] just like repeats the correct word but she but she doesn’t like say anything after. She says oración [correcting sentencia] then just keeps going. |

| Researcher: | O.K. and what do you think about that? |

| Reina: | Sometimes I don’t know what she’s talking about. Like I was just like, “O.K.”, just keep listen. |

| Researcher: | Does it work for you? |

| Reina: | Repetition works sometimes. |

| Researcher: | Repetition? |

| Reina: | Yeah, that’s just what my mom says, repetition, repetition, repetition. It helps to learn things and memorize them but honestly when I get corrected, I still don’t know what I did wrong. |

From Reina, Petra and María’s point of view, Belinda reformulated “erroneous” utterances without providing a clear explanation of the “error”, which the learners perceived as confusing.

Excerpt 5: “I feel like everyone stops…”

| Petra: | She would just, she would just say the word and if we didn’t say it right, she would just say the word again. Speaking wise, she’ll just pronounce the word. So, it’s more like repetition and she doesn’t really explain why but sometimes. |

| Researcher: | Um, do you think that’s helpful? |

| Petra: | Sometimes. Not all the time, like a few times. It just makes me more nervous because I feel like everyone stops to listen. |

The interview excerpts suggest how the SHL learners regarded “repetition” as both a common practice that promoted memorization and also as a source of confusion, frustration and even anxiety.

Excerpt 6: “I’ll just forget it…”

| María: | She’ll just pronounce it the correct way and wait for me to say it properly and we’ll go on and on for a couple times. She doesn’t offer an explanation; she just corrects it. |

| Researcher: | Does it help you? |

| Myriam: | Not really because I’ll just forget it again like in ten minutes. |

The students dismissed the idea of Belinda’s oral CF being beneficial to their learning. For instance, María noted that despite the teacher expecting her to repeat the correct form (to produce output), Belinda’s failure to explain the source of the correction became a barrier to her learning. Despite a shared belief among the learners that repetition leads to memorization and, thus, learning, these data suggest incongruencies between the students’ and the teacher’s beliefs about oral CF practices. Instead of perceiving their teacher’s feedback as disparaging of their varieties, the student participants focused on how they viewed their CF experience as being purposeless and confusing. Furthermore, the data also exemplifies the incongruency between the instructor’s beliefs about the need and efficacy of her CF practices and the SHL learners’ expectations of the language classroom, which were grounded to local Spanish for its practicality and family connection.

5.5. Theme 5: Mejorar y No Dañar el Lenguaje

Upon further review of the data, it is clear that Belinda’s beliefs that shaped her conceptualization of oral CF were interconnected to properties that aligned at times with the appropriateness and expansion. This point was further illustrated in her ideas about her goals for developing her SHL learners’ varieties within the broader moral obligation to improve and expand the Spanish language y no dañarlo (and not damage it).

Excerpt 7: “normal Spanish…”

| Belinda: El español normal, dijéramos así, porque dentro del lenguaje existe el lenguaje que el pueblo lo habla, el lenguaje un poco a un nivel más alto, y el lenguaje que es lo perfecto del lenguaje. Perdón que diga, pero si usted se pone a ver en la televisión, en los noticieros, usted encuentra la diferencia del lenguaje. Usted coloca un noticiero o una televisión y usted va a notar que unas personas hablan con un lenguaje alto… Por qué, por ejemplo, si usted mira Univisión, ¿cuántas locutoras son colombianas de las que dan las noticias? Por el lenguaje. Ahí es donde yo digo, sí hay que pulir, hay que manejar y corregir para que la persona entienda que es necesario mejorar el lenguaje, no dañarlo. | Belinda: Normal Spanish, let’s call it that, because within language there exists the language that is spoken by people from el pueblo, the language that is slightly at a higher level, and language that is perfection. Sorry to say it, but if you watch television, in the news, you will find a difference in language. If you find a news cast or a television and you will notice that some people speak with a high language…Why, for example, if you watch Univision, how many broadcasters are Colombian of those who give the news? Because of the language. That’s why I say, yes lets polish, lets control and correct so that the person can understand that is it necessary to improve their language and not damage it. |

Belinda utilized repeated adjectives and adverbs such as “very medium” and “low” to frame her assessment of the SHL learners’ Spanish compared to institutional expectations of how they should speak in a more appropriate manner. Accordingly, Belinda noted that her goal for the development of the SHL learners’ Spanish was to “elevate” and “polish” the “low” language they brought to the classroom, which were clearly notions entrenched in dominant beliefs about language. Although seemingly neutral, Belinda’s learning goals were mediated by dominant language ideologies that express “…the relative worth of different languages, what constitutes ‘correct’ usage, how particular groups of people ‘should’ speak in given situations” (Leeman 2012, p. 43), which frame U.S. Spanish as a corruption of the Spanish language and which act as an impediment to academic and professional success.

| Belinda: Nosotros [los colombianos] no somos inmigrantes así, siempre todos nos venimos [a los EE.UU] con título. Nosotros llamamos inmigrantes el que pasa la frontera sin permiso, esa es la idea que uno tiene de inmigrante, pero nosotros no somos inmigrantes en ese sentido, sino que la mayoría del 80% llega con sus papeles normales y entran normal. | Belinda: We [Colombians] are not immigrants like that, we always come [to the U.S.] with degrees. We call immigrants those that pass through the border without permission, that is the idea that one has about immigrants, but we are not immigrants in that sense, rather the 80% majority arrives with their papers normally and the enter normally. |

Continuing to construct the ideological group of which speakers possess ‘good’ Spanish, Belinda used Colombian newscasters as examples of professional and ideal upper-class speakers with the desired linguistic qualities that the SHL learners should aspire to obtain. Or as Valdés et al. (2003) describes it, “…beliefs and values centered around conceptualizations of monolingual educated native speakers and the ways in which educated is also understood as a euphemism for membership in a particular social class” (Valdés et al. 2003, p. 118). Belinda further situated upper-class Colombian Spanish as the ideal model representative of this so-called “elevated” variety of Spanish by creating a detailed contrast between her own variety and the local Mexican community. In this way, the participant imbued herself with the epistemic authority to teach Spanish, as well as to work with this “underprivileged” student population. The geopolitical anthroponym “colombiano” was utilized in reference to immigration, elite social status and, thus, it was clear that this term took on a metonymical meaning for “good” Spanish. As van Dijk (2016) indicates, speakers often use pronouns to denote their membership and other’s membership to ideological groups. This they vs. us polarization is exemplified in the repeatedly used pronoun “nosotros” (we) and the negation “no” to communicate: “we [Colombians] are not immigrants”. In this sense, the opposite of we is the use of they to create a distance between herself and the local community that immigrated to the U.S. without documents. In her view, Colombians in the U.S., including herself, do not fall into the same stereotypical category with the local Mexican immigrant community. The data show how Belinda constructed the notion of “standard” language practices and, ultimately her CF practices, in ways that were clearly intertwined with the social stigma and socio-political obstacles of the local SHL community.

5.6. Theme 6: SHL Learner Resistance

Despite the ideologies faced by the SHL learners, they did not passively accept their instructor’s oral CF. The following excerpts showcase how the SHL participants expressed their discontent and confusion with the classroom vocabulary.

Excerpt 8: “…my culture”

| Reina: | Yeah, more like words I don’t hear anyone in my culture say. I’m learning, I’m trying to like get better at stuff so I could communicate better with people from my culture and like form for my family and I, if I use vosotros in front of them, they’ll roast me. Like, it’s not something I’m willing to do. |

| Petra: | I don’t think Belinda really likes Spanglish because most my family is, all they talk is Spanglish. They don’t talk the correct form of Spanish. So when I come into class and hear words that they’ve used differently, it kind of confuses me. |

| María: | She makes me feel stupid. I’m like “come on!” It [the word] still works the same for me you know. I still get places by using that word. I feel like my Spanish is the common everyday Spanish that you would hear not some boujee stuff where I’m going to be like O.K. I’m never going to use that again. |

| Myriam: | I feel like that at the same time. It’s awkward. It’s because people are not used to it. Like if I say bolígrafo people are going to be like “oh, what do you mean” instead of you say pen. |

Reina, Petra, María, and Myriam discuss how vocabulary items from the class materials did not reflect their home varieties that they considered to be more authentic, useful, and common. In contrast to what Belinda thought, the SHL learners’ so-called Spanish of “el pueblo” was the common everyday Spanish that they wanted to learn and use with their community. This was reflected in the use of “my” to relate the personal connection students’ had with their HL: “my culture” and “my family”. Reina and María both made use of quotes and quotatives to illustrate the difficulty in having to reconcile their home Spanish with classroom expectations. Both SHL participants expressed their frustration with Belinda: “She makes me feel stupid”. Such discourse is indicative that these SHL learners noticed how the classroom instruction they received—often catered to L2 learners—failed to reflect the regional lexical variation familiar to them and their communities (c.f., Shenk 2014). As such, the SHL learners expressed a disinterest for such L2 textbook vocabulary as it was not relevant to them, to their families and may have even become a source of ridicule within their own speech communities (e.g., “I’m never going to use that again”). Moreover, Reina and María’s sentiment of wanting to learn Spanish to communicate with people from their culture and families is reflective of why many learners choose to study their HL (Carreira and Kagan 2011). Reina argued that local Spanish was important because she fulfilled the role as a language broker within her family; thus, using the local lexicon was vital to effectively helping her parents. For these SHL participants, learning in a context where their varieties were not represented while facing the pressure to learn a culturally foreign variety, created a situation in which these students became keenly aware of the linguistic differences between their “common everyday Spanish” and the “boujee” (upper-class) classroom Spanish.

Many of the viewpoints expressed by the student participants are analogous to the CLA philosophy. For instance, the value that they placed on their own varieties and the awareness that they presented in exposing the upper-class values associated with certain language forms allowed them, at times, to resist Belinda’s CF. Furthermore, they showed their emerging critical metalinguistic awareness by questioning Belinda’s authority as well as the classroom Spanish being taught to them (e.g., bolígrafo and vosotros). As Ducar (2008) observes, SHL learners’ perceptions on what Spanish is used and taught by the teacher “may allow us a window into their ability to recognize variety outside of their own” (p. 420). Likewise, the students were able to engage in critical language analysis by drawing upon their lived experiences and linguistic knowledge to interrogate their own educational experiences. These findings support the fact that SHL learners already possess significant expertise on such matters, which can be amplified by working within frameworks that further develop their critical analytical abilities.

6. Discussion

The present study examined the beliefs and values of one instructor of Spanish and her four SHL learners. Clearly, Belinda’s deep-seated ideologies regarding the worth of her SHL learners and the varieties they speak were an underlying element that critically shaped how the participants viewed this high-stakes instructional practice. The learning and teaching of “correct” Spanish and of being “corrected” are typically perceived as apolitical practices within L2 learning contexts. In contrast, for SHL learners, the same notion of “expanding” one’s language “abilities” is a socio-politically loaded construct that entails a range of potential real-world implications for themselves and their communities—it is not always the same for L2 learners. The study’s findings cast a critical eye on how the instructor leveraged the SHL learners’ social categories to construct and justify additive learning goals for the students’ development while also promoting an appropriateness-based view of her students’ Spanish; thereby, providing clear examples of how macro-level ideologies shape micro-level interview discourses and practices. Because of the scope of this study, the full range of the methodology employed, including a recorded classroom discourse of Belinda’s CF practices during instruction were not included. Furthermore, this study does not claim to represent all SHL learners, but rather adds to the growing evidence that language ideologies are significant determinants of SHL learners’ educational experiences within language education. As Li (2017) indicated, discrepancies between what teachers say they do and how they actually practice CF calls for a closer examination of HL teacher development. This is especially important given that gaining a rigorous understanding of the mismatches between teacher and student expectations regarding CF is invaluable to the development of instructional best practices. This data represents the experiences of participants in a specific learning context, which can then be compared to other educational situations to generate pedagogical practices that are germane to the SHL context. Given that the majority of SHL learners in the U.S. study Spanish within mixed courses and not in specialized SHL classes (Carreira and Kagan 2018), it is crucial that qualitative research continues to document the full range of classroom learning experiences and pedagogical practices designed for L2 learning. Additionally, future research must explore how CF practices are utilized by instructors with different pedagogical backgrounds to fully understand how teaching practices might be designed for SHL learners.

Expanding the Boundaries of CLA: Oral CF

Viewing oral CF through a lens that is capable of accounting for the many ways that it can potentially become ideologically charged is invaluable to theorizing it within the field of SHL education. Belinda often mitigated her discriminatory beliefs and eradicationist intents by masking them as expansion and appropriateness learning objectives. This was possible because none of the approaches to SHL language variation that currently exist in the field, with the exception of the critical language awareness approach, explicitly contest the socio-political aspects of language in society (Beaudrie and Loza 2022; Holguín Mendoza 2018; Leeman 2005). As discussed in an earlier section, oral CF is a debatable and an ideologically contradictory practice on account of the SHL field’s continued struggle to reconcile the teaching of a privileged variety of Spanish with respect for the Spanish spoken by its learners. Because the field has developed much of its pedagogy on the conviction that SHL learners’ varieties are inherently valid, teaching in isolation from the sociolinguistic context and validity of bilingual discourses only sustains a monolithic idea of language as being static and uniform across all speakers of Spanish. Therefore, a path toward reconciling the ideological contradiction that oral CF represents for SHL pedagogy lays in the tenets of CLA.

CLA draws attention to the vital need to develop reflective practices not only for learners, but also for pedagogues who are willing to engage in a transformative process that closely examines and questions the socio-politics that have long played an important role in forming the lived educational experiences and social realities of minoritized students. The broad goal of CLA is to engage pedagogues and researchers to reimagine education to include and support the socio-political and economic interests of marginalized groups of learners. Specifically, CLA aims to transform society through instruction that instills a learner awareness of social and educational inequity as well as the agency to correct such social wrongs (Beaudrie et al. 2019, 2021; Leeman 2005; Holguín Mendoza 2018; Quan 2020).

Departing from the above stated CLA principles, there are several considerations that are important in order to engage in reflective practices about CF (see also Loza 2022):

- Teachers must reflect on the fact that they have the authority to initiate oral CF at their discretion as well as the authority to decide what counts as worthy knowledge within the classroom.

- Moving past narrow conceptualizations of CF must consider that the idea of correctness, about being corrected and about correcting others are all discursive practices that speakers engage with both inside and outside of the classroom. They may convey asymmetrical power relationships depending on the situational context and the relationship between the speakers.

- When teachers “correct” SHL learners’ varieties they are listening to a racialized speaking subject. Flores and Rosa’s (2015) scholarship brings attention to the ways that minoritized learners are often “heard” based on who they are and not on how they are able to model elite varieties that are conceived as being “professional” or “appropriate”. Because racialized learners are viewed as being inherently deficit speakers, pedagogues must learn to listen differently by gaining an awareness of the ideologies that underpin deficit perceptions of minoritized students.

- Educators must reflect openly and humbly on their own positionality as listeners, as language users, language learners, and the privileges they hold over their leaners.

- Pedagogues should cultivate a democratic classroom wherein critical metalinguistic awareness is welcomed. Learners should feel enabled to openly ask questions and even resist CF if they do not agree and engage in a socio-linguistically-based discussion that reaches beyond the appropriateness of language within the institutional context.

- CLA stimulates learners to gain a critical metalinguistic awareness of their own speech communities. This tenet can be extended to include SHL’s own self-awareness of the educational process to which they belong. Pedagogues should consider having open class conversations about the purpose and intent of CF and how it relates to the philosophy of the course; thereby, engaging learners in their own learning process.

The above-mentioned recommendations are a reflection on the present findings and aim to initiate a conversation regarding this salient yet glossed over issue within the field. These recommendations should be considered within the context of SHL instructor development as part of CLA. Prior research like Quan (2021) provides significant evidence to suggest that critically-oriented teacher development is both effective and highly necessary. Reflecting on these considerations can provide examples of how language instructors can reimagine and apply the tenets of CLA to different programmatic and curricular contexts such as oral CF. Finding new ways to extend the theoretical reach of critical philosophies is invaluable to designing teaching models that are responsive and provide SHL learners with a transformative learning experience.

7. Conclusions

Given the study’s findings, CLA provides a critical framework to develop guidelines to overcome the ideological issues observed in this study’s data. The qualitative findings reported, aim to make sense of and identify patterns within the interview data to paint a meaningful picture of the importance of adding the dimensionality of “ideology” to the construct of oral CF within the larger context of SHL education, rather than searching for “generalizability” in the quantitative sense. Importantly, this study contributes to rendering visible the fact that the SHL field must account for the ideologically charged nature of oral CF, which can potentially become tied to values about what is “normal” and “correct” speech, in turn, reinforcing what it means to “learn” a language within the academic context” (Loza 2022, p. 126). SLA research on beliefs about CF draws upon attitudinal data that stem from a social psychology framework. Despite the valuable insight that this line of research provides, attitudes “emphasize individual beliefs and to pay less attention to the politics of language” (Leeman 2012, p. 43); therefore, the field needs a complementary focus that that is capable of understanding how instructional practices embody ideologies. Future directions to researching and developing oral CF practices for the SHL context must account for its connections to questions of power as a moral and ethical obligation for providing minoritized learners with a quality educational experience. Lastly, these SHL learner participants resisted and exercised their agency by questioning the validity of their instructor’s CF practices. This resistance was largely based on the SHL learners’ emerging critical metalinguistic awareness wherein their community’s variety of Spanish was viewed as being more legitimate and viable than the Spanish taught in the classroom. These results confirm the need to include CLA as a way to validate and expand upon SHL learners’ “intuitions” that emerge from their lived social and linguistic knowledge.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Maricopa County Community College District (protocol code 2018-02-609 and date of 2 March 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Acevedo, Rebeca. 2003. Navegando a través del registro formal. In Mi Lengua: Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States. Edited by Ana Roca and M. Cecilia Colombi. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 257–68. [Google Scholar]

- Agudo, Juan de Dios Martínez. 2014. Beliefs in learning to teach: EFL student teachers’ beliefs about corrective feedback. Utrecht Studies in Language and Communication 27: 209–362. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara M. 2015. Approaches to Language Variation: Goals and Objectives of the Spanish Heritage Language Syllabus. Heritage Language Journal 12: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., and Damián Wilson. 2022. Reimagining the goals of HL pedagogy through critical language awareness. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., and Sergio Loza. 2022. The central role of critical language awareness in Spanish heritage language education in the United States: An introduction. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., Angélica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2019. Critical language awareness for the heritage context: Development and validation of a measurement questionnaire. Language Testing 36: 573–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., Angélica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2021. Critical language awareness in the heritage language classroom: Design, implementation, and evaluation of a curricular intervention. International Multilingual Research Journal 15: 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Enríquez, Ysaura, and Eduardo Hernández-Chávez. 2003. La enseñanza del español en Nuevo México: ¿Revitalización o erradicación de la variedad chicana? In Mi Lengua: Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States. Edited by Ana Roca and M. Cecilia Colombi. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bessette, Ryan M., and Ana M. Carvalho. 2022. The structure of Spanish. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, Maria. 2000. Validating and promoting Spanish in the United States: Lessons from linguistic science. Bilingual Research Journal 24: 423–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2011. The results of the National Heritage Language Survey: Implications for teaching, curriculum design, and professional development. Foreign Language Annals 44: 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2018. Heritage language education: A proposal for the next 50 years. Foreign Language Annals 51: 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2012. Code-switching from theoretical to pedagogical considerations. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: The State of the Field. Edited by Sara M. Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 139–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ducar, Cynthia Marie. 2006. (Re) Presentations of US Latinos: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Spanish Heritage Language Textbooks. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ducar, Cynthia Marie. 2008. Student voices: The missing link in the Spanish heritage language debate. Foreign Language Annals 41: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2009. Corrective feedback and teacher development. L2 Journal 1: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellis, Rod. 2017. Oral corrective feedback in L2 classrooms: What we know so far. In Corrective Feedback in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Edited by Hossein Nassaji and Eva Kartchava. New York: Routledge, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Nelson, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review 85: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitiérrez, John R. 1997. Teaching Spanish as a heritage language: A case for language awareness. ADFL Bulletin 29: 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín Mendoza, Claudia. 2018. Critical language awareness (CLA) for Spanish heritage language programs: Implementing a complete curriculum. International Multilingual Research Journal 12: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, Barbara. 2018. Discourse Analysis. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo-Brown, Kimi. 2003. Heritage language instruction for post-secondary students from immigrant backgrounds. Heritage Language Journal 1: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroskrity, Paul V. 2010. Language ideologies: Evolving perspectives. In Society and Language Use. Edited by Jürgen Jaspers, Jef Verschueren and Jan-Ola Östman. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 192–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2015. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lacorte, Manel, and José L. Magro. 2022. Foundations for critical and antiracist heritage language teaching. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2005. Engaging critical pedagogy: Spanish for native speakers. Foreign Language Annals 38: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2010. Introduction. The sociopolitics of heritage language education. In Spanish of the U.S. Southwest: A Language in Transition. Edited by Susana V. Rivera-Mills and Daniel J. Villa. Norwalk: Iberoamericana Vervuert Publishing Co., pp. 309–17. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2012. Investigating language ideologies in Spanish as a heritage language. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: The State of the Field. Edited by Sara M. Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shaofeng. 2017. Student and teacher beliefs and attitudes about oral corrective feedback. In Corrective Feedback in Second Language Teaching and Learning: Research, Theory, Applications, Implications. Edited by Hossein Nassaji and Eva Kartchava. New York: Routledge, pp. 143–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lowther Pereira, Kelly Anne. 2010. Identity and Language Ideology in the Intermediate Spanish Heritage Language Classroom. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Loewen, Shawn, Shaofeng Li, Fei Fei, Amy Thompson, Kimi Nakatsukasa, Seongmee Ahn, and Xiaoqing Chen. 2009. Second language learners’ beliefs about grammar instruction and error correction. The Modern Language Journal 93: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza, Sergio. 2019. Exploring Language Ideologies in Action: An Analysis of Spanish Heritage Language Oral Corrective Feedback in the Mixed Classroom Setting. Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Loza, Sergio. 2022. Oral corrective feedback in the Spanish heritage language context: A critical perspective. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 119–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lyster, Roy, Kazuya Saito, and Masatoshi Sato. 2013. Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Language Teaching 46: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2016. Designing Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Glenn. 2003. Classroom based dialect awareness in heritage language instruction: A critical applied linguistic approach. Heritage Language Journal 1: 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2013. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Porras, Jorge. 1997. Uso local y uso estándar: Un enfoque bidialectal a la enseñanza del español para nativo. In La Enseñanza Del Español a Hispanohablantes: Praxis y Teoría. Edited by María Cecilia Colombi and Francisco Alarcón. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 190–98. [Google Scholar]

- Potowski, Kim. 2005. Fundamentos de la Enseñanza del Español a Hispanohablantes en los EE.UU. Madrid: Arcos Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Tracy. 2020. Critical language awareness and L2 learners of Spanish: An action-research study. Foreign Language Annals 53: 897–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Tracy. 2021. Critical Approaches to Spanish Language Teacher Education: Challenging Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Fostering Critical Language Awareness. Hispania 104: 447–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, Muhammad, and Lawrence Jun Zhang. 2015. Exploring non-native English-speaking teachers’ cognitions about corrective feedback in teaching English oral communication. System 55: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razfar, Aria. 2010. Repair with confianza: Rethinking the context of corrective feedback for English learners (ELs). English Teaching: Practice and Critique 9: 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Reisigl, Martin, and Ruth Wodak. 2016. The discourse-historical approach. In Methods of Critical Discourse Studies. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 23–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pino, Cecilia. 1997. La reconceptualización del programa de español para hispano hablantes: Estrategias que reflejan la realidad sociolingüística en la clase. In La enseñanza del Español a Hispanohablantes: Praxis y teoría. Edited by María Cecilia Colombi and Francisco Alarcón. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pino, Cecilia, and Daniel Villa. 1994. A student-centered Spanish-for-native-speakers program: Theory, curriculum design, and outcome assessment. In Faces in a Crowd: The Individual Leaner in Multisection Courses. Edited by Carol A. Klee. Boston: Heinle and Heinle Publishers, pp. 355–77. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego, Fabián, and Cecilia Pino. 2000. Frequently asked questions about SNS programs. In Spanish for Native Speakers. Edited by AATSP. Fort Worth: Harcourt College, vol. 1, pp. 29–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Rosaura. 1981. Spanish for native speakers at the university: Suggestions. In Teaching Spanish to the Hispanic Bilingual: Issues, Aims and Methods. Edited by Guadalupe Valdés, Anthony Lozano and Rodolfo Garcia Moya. New York: Teachers College Press, pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, Renate A. 1996. Focus in the foreign language classroom: Students’ and teachers’ views on error correction and the role of grammar. Foreign Language Annals 29: 343–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, Younghee. 2006. Exploring the relationship between characteristics of recasts and learner uptake. Language Teaching Research 10: 361–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenk, Elaine M. 2014. Teaching sociolinguistic variation in the intermediate language classroom: Voseo in Latin America. Hispania 97: 368–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 1981. Pedagogical implications of teaching Spanish to the Spanish-speaking in the United States. In Teaching Spanish to the Hispanic Bilingual: Issues, Aims and Methods. Edited by Guadalupe Valdés, Anthony Lozano and Rodolfo Garcia Moya. New York: Teachers College Press, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés-Fallis, Guadalupe. 1978. A comprehensive approach to the teaching of Spanish to bilingual Spanish-speaking students. Modern Language Journal 35: 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe, Sonia V. González, Dania López García, and Patricio Márquez. 2003. Language ideology: The case of Spanish in department of foreign language. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 34: 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, Teun A. 2016. Critical discourse studies: A sociocognitive approach. In Methods of Critical Discourse Studies. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishers, pp. 62–85. [Google Scholar]