SHL Teacher Development and Critical Language Awareness: From Engaño to Understanding

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Spanish as a Heritage Language in the Midwest

1.2. Language Teacher Training and SHL

1.3. Critical Language Awareness and Language Teacher Training

2. Current Research

2.1. Examining Teachers’ Ideologies and Practices

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Research Purpose and Questions

- Do Ohio’s high school Spanish teachers feel prepared to teach and meet the needs of their SHL students?

- What are these Ohio teacher participants’ perceptions of SHL student language?

- Can exposure to varieties of US Spanish, linguistic variation in general and critical language awareness result in a change in teacher attitudes toward SHL student language?

3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative and Qualitative Results

4.1.1. Demographic Information

4.1.2. General Quantitative Results

4.1.3. Outlier Data

4.2. Qualitative Results

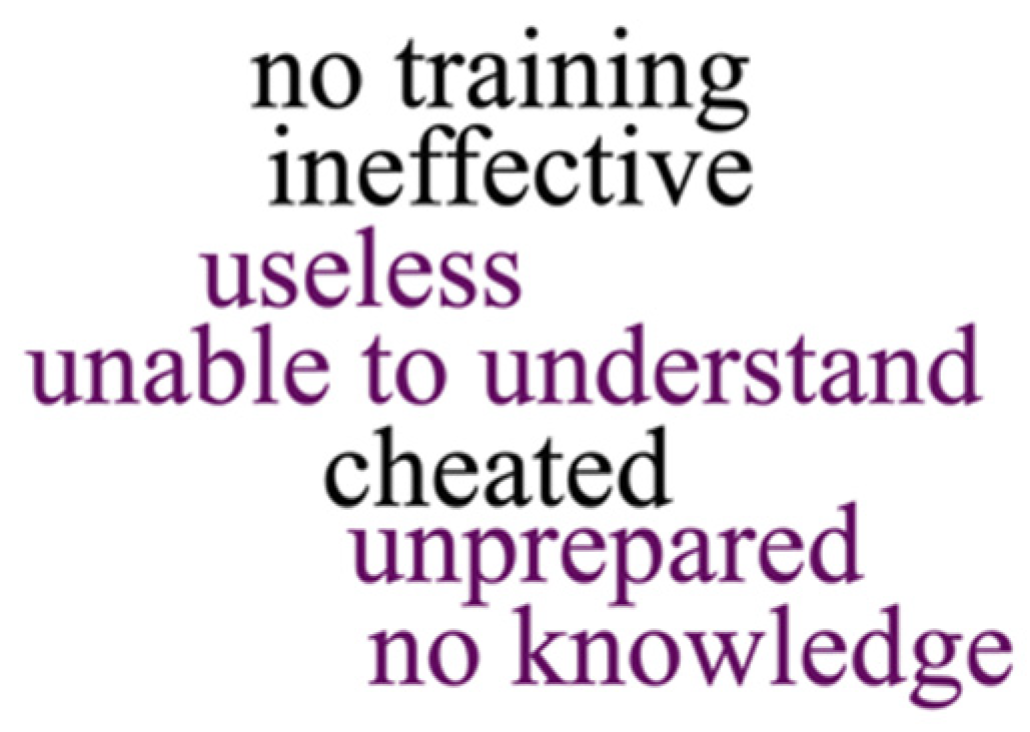

4.2.1. SHL Teacher Preparation

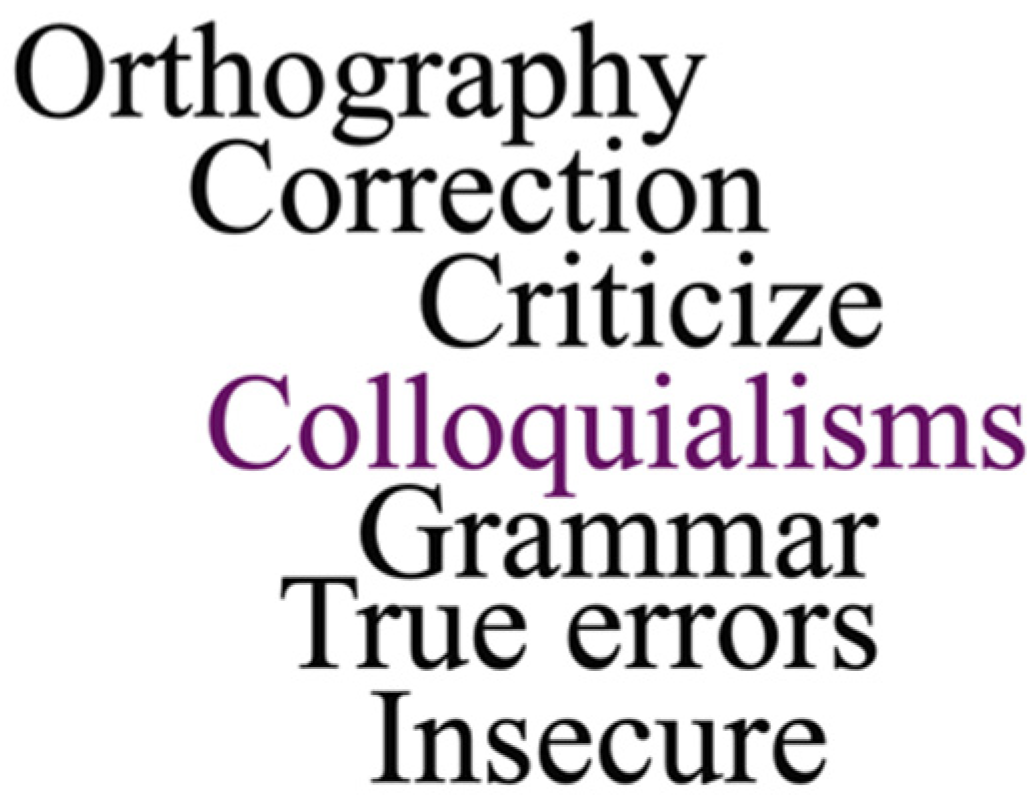

4.2.2. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Student Language

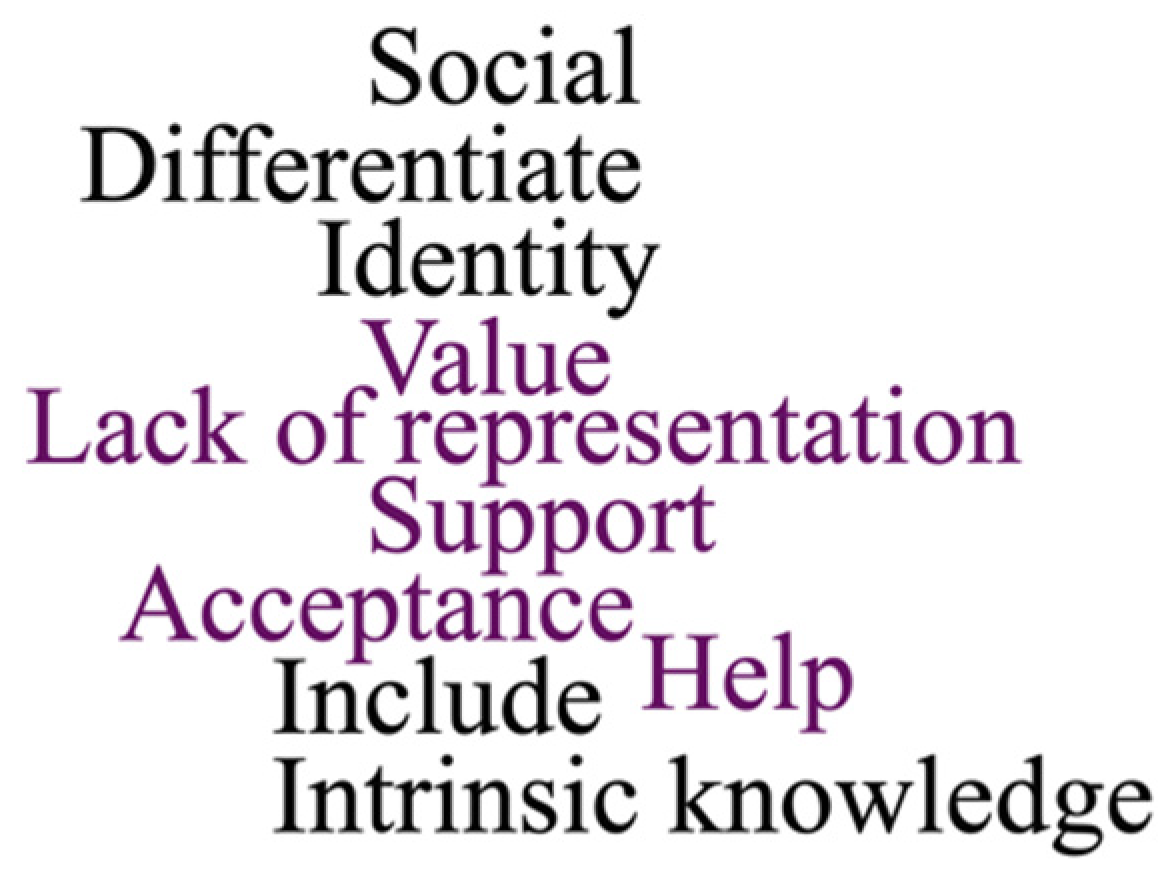

4.2.3. Critical Language Awareness and Transformation

5. Discussion and Suggestions

5.1. Teacher Training Reform

5.2. Increasing Teachers’ Knowledge of Students’ Varieties of Spanish

5.3. CLA as a Means to Revamp the System and Transform Understanding

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Course Topics

| Week 1 | What is SHL? |

| Week 2 | Who are SHL students? |

| Week 3 | What are the goals of SHL instruction? (CLA) |

| Week 4 | What is U.S. Spanish? (sociolinguistic perspectives) (CLA) |

| Week 5 | What is U.S. Spanish? (sociolinguistic perspectives, continued) (CLA) |

| Week 6 | What is standard, academic Spanish? (CLA) |

| Week 7 | What are the tenets of SHL pedagogy? (CLA) |

| Week 8 | How can we best place SHL students into classes that will meet their needs? |

| Week 9 | How can we help SHL students develop their speaking and listening skills? |

| Week 10 | How can we help SHL students develop their reading skills? |

| Week 11 | How can we help SHL students develop their writing skills? |

| Week 12 | What is grammar and is there a place for grammar instruction in the SHL context? (CLA) |

| Week 13 | What is culture and what is the role of culture in the SHL context? |

| Week 14 | What is the role of critical applied linguistics in the SHL classroom? (CLA) |

| Week 15 | How can I develop a critically aware language classroom for all of my students? (CLA) |

| 1 | For more information on College Credit Plus, see here: https://www.ohiohighered.org/collegecreditplus (accessed on 20 May 2022). |

| 2 | Please note that all names included in the study are pseudonyms. No identifying participant information is included. |

| 3 | Baasim’s heritage language is Arabic. He has lived in numerous Arabic- and French-speaking countries, in addition to his time in the United States. |

| 4 | All translations are provided by the author. All text in Spanish is written exactly as it appeared in the course discussion board. Translations aim to convey the meaning of the participants without addressing grammatical and lexical differences. |

| 5 | It should be noted that all the teacher participants chose to enroll in this course. Therefore, it is possible that they were highly motivated by the topic and were more open to learning new ideas about SHL and CLA. The results and data are only representative of the participants involved in this study and may not be reflective of teacher attitudes in the field. As one reviewer pointed out, it is quite possible that more teachers agree with the ideas expressed by the outlier in this study. |

References

- Alonso, Carlos. 2007. Spanish: The foreign national language. Profession 2007: 218–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Stephanie. 2013. Evaluating the role of the Spanish department in the education of US Latin@ students: Un testimonio. Journal of Latinos and Education 12: 131–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, Blair E., and Sara L. Wilkinson. 2010. Spanish for Heritage Speakers: A Statewide Survey of Secondary School Teachers. Foreign Language Annals 43: 324–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara. 2011. Spanish heritage language programs: A snapshot of current programs in the southwestern United States. Foreign Language Annals 44: 321–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara. 2012. Research on university-based Spanish heritage language programs in the United States: The current state of affairs. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: State of the Field. Edited by Sara Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 203–21. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara. 2020. Towards growth for Spanish heritage programs in the United States: Key markers of success. Foreign Language Annals 53: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., and Marta Ana Fairclough. 2016. Innovative Strategies for Heritage Language Teaching: A Practical Guide for the Classroom. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara, and Damian Vergara-Wilson. 2022. Reimagining the goals of SHL pedagogy through critical language awareness. In Heritage Language Teaching and Research: Perspectives from Critical Language Awareness. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara Beaudrie. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara, Cynthia Ducar, and Kim Potowski. 2014. Heritage Language Teaching; Research and Practice. New York: McGraw Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara, Angélica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2021. Critical Language Awareness in the Heritage Language Classroom: Design, Implementation, and Evaluation of a Curricular Intervention. International Multilingual Research Journal 15: 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Alan, and Gregory Thompson. 2018. The Changing Landscape of Spanish Language Curricula: Designing Higher Education Programs for Diverse Students. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, María. 2022. HL Exchange, Week 4. Available online: https://csulb-my.sharepoint.com/:w:/g/personal/maria_carreira_csulb_edu/EYKAGeqLmCRHoaCmIYMdgu0BERNcp5hVIaQ93iUIVzwcxA?rtime=Qz2sz7BT2kg (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Carreira, Maria, Claire Hitchins Chik, and Shushan Karapetian. 2019. Project-Based Learning in the Context of Teaching Heritage Language Learners. In Project-Based Learning in Second Language Acquisition: Building Communities of Practice in Higher Education. Edited by Adrian Gras-Velazquez. New York: Routledge, pp. 135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon Perugini, Dorie, and Stacey Johnson. 2020. We Teach Languages Episode 142: Language Legitimacy and Imagining New Educational Contexts with Jonathon Rosa [Audio Podcast]. Available online: https://weteachlang.com/2020/06/12/142-with-jonathan-rosa/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Douglas Fir Group. 2016. A Transdisciplinary Framework for SLA in a Multilingual World. The Modern Language Journal 100: 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducar, Cynthia M. 2008. Student Voices: The Missing Link in the Spanish Heritage Language Debate. Foreign Language Annals 41: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman, ed. 1992. Critical Language Awareness. London and New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Nelson, and Jonathon Rosa. 2019. Bringing race into second language acquisition. Modern Language Journal 103: 145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gironzetti, Elisa, and Flavia Belpoliti. 2021. The other side of heritage language education: Understanding Spanish heritage language teachers in the United States. Foreign Language Annals 54: 1189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, Kimberly. 2013. A Twice-Told Tale: Voices of Resistance in a Borderlands Spanish Heritage Language Class. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 44: 269–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín Mendoza, Claudia. 2017. Critical Language Awareness (CLA) for Spanish Heritage Language Programs: Implementing a Complete Curriculum. International Multilingual Research Journal 12: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, Gabriela. 2012. Hindi heritage language learners’ performance during OPIs: Characteristics and pedagogical implications. The Heritage Language Journal 9: 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, Véronique, Jijun Zhang, Xiaolei Wang, Sarah Hein, Ke Wang, Ashley Roberts, Christina York, Amy Barmer, Farrah Bullock Mann, Rita Dilig, and et al. 2021. Report on the Condition of Education 2021 (NCES 2021-144); Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2021144 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lacorte, Manal, and Evelyn Canabal. 2005. Teacher beliefs and practices in Advanced Spanish classrooms. Heritage Language Journal 3: 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jin Sook, and Eva Oxelson. 2006. ‘It’s Not My Job’: K–12 Teacher Attitudes toward Students’ Heritage Language Maintenance. Bilingual Research Journal 30: 453–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2005. Engaging Critical Pedagogy: Spanish for Native Speakers. Foreign Language Annals 38: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2015. Heritage Language Education and Identity. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 35: 100–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2018. Critical language awareness and Spanish as a heritage language: Challenging the linguistic subordination of US Latinxs. In Handbook of Spanish as a Minority/Heritage Language. Edited by Kim Potowski. New York: Routledge, pp. 345–58. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer, and Pilar García. 2007. Ideologías y prácticas en la enseñanza del español como lengua mayoritaria y lengua minoritaria. In Lingüística Aplicada del Español. Edited by Manel Lacorte. Madrid: Arco Libros, pp. 117–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lippi-Green, Rosina. 2004. Language ideology and language prejudice. In Language in the USA. Themes for the Twenty-First Century. Edited by Edward Finegan and John R. Rickford. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Looney, Dennis, and Natalia Lusin. 2019. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report. Modern Language Association of America. Available online: https://www.mla.org/Resources/Research/Surveys-Reports-and-Other-Documents/Teaching-Enrollments-and-Programs/Enrollments-in-Languages-Other-Than-English-in-United-States-Institutions-of-Higher-Education (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Loza, Sergio. 2017. Transgressing Standard Language Ideologies in the Spanish Heritage Language (SHL) Classroom. Chiricú Journal: Latina/o Literatures, Arts, and Cultures 1: 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza, Sergio, and Sara Beaudrie. 2022. Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness Perspectives for Research and Pedagogy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Macías, Reynaldo. 2003. The Role of Schools in Language Maintenance and Shift. Available online: https://international.ucla.edu/institute/article/3901 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Martinez, Glenn, and Robert Train. 2020. Tension and Contention in Language Education for Latinxs in the United States. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamonte, Luis, Hugo Lopez, Mark Korgstad, and Jens Manuel. 2020. U.S. Hispanic population surpassed 60 million in 2019, but growth has slowed. Pew Research Center Publication. Available online: https://pewrsr.ch/30oRezf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- ODE Facts and Figures. 2022. Ohio Department of Education. February 28. Available online: https://education.ohio.gov/Media/Facts-and-Figures (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Pascual y Cabo, Diego, and Josh Prada. 2018. Redefining Spanish Teaching and Learning in the United States. Foreign Language Annals 51: 533–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Kelly. 2015. Developing Critical Language Awareness via Service Learning for Heritage Speakers. Heritage Language Journal 12: 159–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim. 2002. Experiences of Spanish heritage speakers in university foreign language courses and implications for teaching training. ADFL Bulletin 33: 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim. 2005. Fundamentos de la Enseñanza del Español a Hispanohablantes en los EE.UU. Madrid: Arco/Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph, Linwood J. 2017. Heritage Language Learners in Mixed Spanish Classes: Subtractive Practices and Perceptions of High School Spanish Teachers. Hispania 100: 274–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, Linwood J. 2022. CLA in the mixed L2/SHL classroom. In Heritage Language Teaching and Research: Perspectives from Critical Language Awareness. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara Beaudrie. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Brittany D., and Lisa M. Kuriscak. 2015. High School Spanish Teachers’ Attitudes and Practices toward Spanish Heritage Language Learners. Foreign Language Annals 48: 413–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Julio, Diego Pascual y Cabo, and John Beusterien. 2018. What’s next?: Heritage Language Learners Shape New Paths in Spanish Teaching. Hispania 100: 271–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2017. From Language Maintenance and Intergenerational Transmission to Language Survivance: Will ‘Heritage Language’ Education Help or Hinder? International Journal of the Sociology of Language 243: 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe, Joshua Fishman, Rebecca Chávez, and William Pérez. 2006. Developing Minority Language Resources: The Case of Spanish in California. Buffalo: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, Teun. 1988. How ‘They’ Hit the Headlines. Ethnic Minorities in the Press. In Discourse and Discrimination. Edited by Geneva Smitherman-Donaldson and Teun van Dijk. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, pp. 221–62. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, Daniel. 2002. The Sanitizing of U.S. Spanish in Academia. Foreign Language Annals 35: 222–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | Language maintenance |

| 2. | Acquisition or development of a prestige language variety |

| 3. | Expansion of bilingual range |

| 4. | Transfer of literacy skills |

| 5. | Acquisition or development of academic skills in the heritage language |

| 6. | Positive attitudes toward both the heritage language and various dialects of the language, and its cultures |

| 7. | Acquisition or development of cultural awareness |

| Number | Student Status | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | Full-time high school teachers | Northwest Ohio |

| 3 | (2) Second year MA Spanish students and (1) first year MA student | On campus |

| 8 | First year MA students | Studying abroad in Spain |

| Heritage Speaker | L2 Speaker of Spanish | Partner Is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish | Years of Teaching Experience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marisol | X (Mexican-American) | 7 | ||

| Gisela | X (Cuban-American) | 10 | ||

| Grace | X (Mexican-American) | 14 | ||

| Baasim | X3 | X | 5 | |

| Liliana | X | X (partner is Mexican-American) | 2 | |

| Carina | X | X (partner is Mexican-American) | 5 | |

| Arianna | X | 6 | ||

| Mark | X | 5 | ||

| Emi | X | 5 | ||

| Austin | X | 5 | ||

| Jack | X | 23 | ||

| Kayla | X | 6 | ||

| Karter | X | 8 | ||

| Jordyn | X | 5 | ||

| Sharon | X | 15 | ||

| Evelyn | X | 10 | ||

| Anita | X | 25 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ducar, C. SHL Teacher Development and Critical Language Awareness: From Engaño to Understanding. Languages 2022, 7, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030182

Ducar C. SHL Teacher Development and Critical Language Awareness: From Engaño to Understanding. Languages. 2022; 7(3):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030182

Chicago/Turabian StyleDucar, Cynthia. 2022. "SHL Teacher Development and Critical Language Awareness: From Engaño to Understanding" Languages 7, no. 3: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030182

APA StyleDucar, C. (2022). SHL Teacher Development and Critical Language Awareness: From Engaño to Understanding. Languages, 7(3), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030182