Abstract

This paper provides a syntactic analysis of two types of compounds in Greek: synthetic and phrasal compounds derived from agentive nominalizations of verbal strings containing an internal argument of the verb. The analysis is couched within a ‘morphology as syntax’ account and uses independently motivated syntactic tools to show that both types of compounds are derived in syntax proper without any need for a separate morphological component. The differences in the syntactic properties of the two types of compounds are explained with reference to the ‘size’ or ‘complexity’ of the projected internal arguments, which can be either ‘roots’, in the case of synthetic compounds, or unquantized nominals projected as NumPs, which require special licensing conditions in the case of phrasal compounds. Differences in prosodic and semantic interpretation are also explained with reference to phase theory and the type/number of phase domains within the structure of the two types of compounds.

1. Introduction

Synthetic verbal compounds have been at the forefront of the discussion of the morphology syntax interface because of their idiosyncratic morphosyntactic properties. The decision on whether they are formed exclusively within the morphological or the syntactic component of the grammar (or in both) is important for deciding the status of morphology as an independent module of grammar.

This paper argues for a syntactic derivation of Greek agentive synthetic and phrasal compounds following recent syntactic accounts of ‘traditional’ morphological processes such as derivation and compounding, including Distributed Morphology (DM, Halle and Marantz 1993; Halle 1997) and Nanosyntax (Starke 2002, 2009; Caha 2009). However, while the approach advocated here is in the spirit of certain DM accounts of compounding (e.g., Harley 2009), it departs from more recent accounts of DM that seem to reinstate a morphological layer at the base ‘root’ level of syntactic structure. It is assumed that roots are active syntactic objects that project argument structure before category-assigning heads are projected. This conflicts with Wood (2021) and Marantz (2021), who assume that a root has to be categorized first, before becoming visible for later syntactic operations, including the selection and licensing of arguments. We show that data from synthetic and phrasal compounding in Greek do not support this assumption and the status of the uncategorized root as a building block of compound formation in syntax must be maintained. The approach on the nature of morphosyntactic structures adopted here is closer to the ‘morphology as syntax’ framework (Collins and Kayne 2020; Koopman 2005), which accounts for traditionally termed morphological generalizations exclusively in terms of syntactic operations and principles (for example, assuming phrasal movement instead of morphological incorporation), without recourse to an independent morphological component in the grammar and without postulating additional post-syntactic morphological operations or a late spell-out. However, the analysis can easily be adapted to certain versions of DM and/or Nanosyntax without any major changes.

Given the hybrid nature of compounds (spanning a range from lexical root-based compounds to phrasal compounds with robust phrasal syntactic properties), the data on compounds in different languages provide an excellent empirical domain to try to understand how independently motivated syntactic processes operate at the low, ‘molecular’ level of the structure-building mechanism.

The work presented here summarizes several tools that have been discussed extensively in the relevant literature on phrasal layering accounts of compound formation, especially within certain versions of the Distributed Morphology framework (see, for example, Alexiadou 2017, 2020; Iordachioaia et al. 2017; Iordachioaia 2019) and presents some further ideas developed independently in syntactic theory, and, in particular, the ‘split-DP’ hypothesis, defended in Sportiche (1999, 2005). The basic building blocks of compounds are assumed to include nominal strings of various sizes and in particular roots (category-neutral lexical elements that receive categorial status through category-assigning functional heads).

We adopt the hypothesis of ‘phases-within-words’ in Marantz (2001, 2006), where certain category-defining functional heads also define a syntactic phase. Several differences in the distribution and prosodic properties of different compound forms, including synthetic and phrasal compounds, are shown to be derived from properties of the lower verbal domain and the variable positional and selectional properties of nominalizing affixes. It is shown that the existence of nominalizing affixes, at least for languages of the Greek and English type, is essential for the successful derivation of such compounds.

Finally, we explore issues of the ‘licensing’ of nominal phrases at this lower molecular level of syntactic structure. While structural Case has been the main licensing mechanism for DPs at different levels of structure, we assume that it is not an available mechanism for the nominal phrases projected at this low structural level, given that the target phrases are not ‘quantized’, in the sense of Sportiche (1999, 2005). We show that, for synthetic compounds in Greek (and other languages), the licensing mechanism involves inversion of the nominal argument over the predicate root that projects it. The analysis is in the spirit of Levin (2015), where it is proposed that nominal licensing does not necessarily require Case-feature valuation (as in Chomsky 2001), but rather, Case-features can survive the derivation unvalued.

Bringing all of these assumptions together, it is proposed that the domain of synthetic and phrasal compound formation is the lower verbal domain, and that the nominalizer defines the categorial projection of this domain, which contains the verbal predicate and an argument that is either a root or a nominal string with number features (a NumP) that has not been quantized (i.e., become referential yet) (Sportiche 1999, 2005). The status of the projected argument (root or unquantized nominal) determines the properties of the derived compound, including internal word order, semantics, and prosody.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the well-established properties of synthetic-compound formation and the apparent lexical-integrity effects that the latter exhibit with reference mainly to Greek compound deverbal nominals; Section 3 presents the main proposal of a phase-based analysis of synthetic-compound formation and provides an explanation of these effects; Section 4 discusses phrasal compounds and shows how their frequent nontransparent readings form an important problem for strictly morphological and lexicalist accounts of word formation; and finally, Section 5 presents concluding remarks.

2. Morphology as Syntax in Compound Formation

Synthetic compounding has been at the forefront of syntactically oriented morphological research since the work of Roeper and Siegel (1978) and extending through Williams (1981); Selkirk (1982); Lieber (1983); Pesetsky (1985); Di Sciullo and Williams (1987); Booij (1988, 2005); Roeper (1988); Di Sciullo (2005); Di Sciullo and Ralli (1999). In more recent work, synthetic and attributive compounding has received analyses within various syntactic models of morphological processes, including Distributed Morphology (Harley 2009) and Nanosyntax (Franco 2011).

Roeper and Siegel (1978) provide an analysis that, even though lexicalist in spirit, encompasses a transformational aspect in postulating a movement rule. In this kind of ‘lexical transformation’, the internal argument of the verb moves from its postverbal position in the verb’s lexical subcategorization frame to a preverbal ‘empty’ position. The movement must obey a First Sister Principle (Roeper and Siegel 1978, p. 208), which states that only a ‘word’ that is the first sister of the head can move to the empty slot. Restriction to words rules out phrasal compounds, while the first-sister restriction rules out verb–goal synthesis in the presence of a theme.

In many ways, this first post-‘Remarks’ (Chomsky 1970) approach to synthetic compounding incorporates aspects of both of the two main approaches that have dominated the relevant literature since then: the lexicalist approach and the syntactic approach. The first assumes a separate grammatical component for the operations that give rise to the derivation of synthetic compounds and similar structures (see, among others, Williams (1981); Selkirk (1982); Di Sciullo and Williams (1987); Booij (1988); Di Sciullo (2005)). The second assumes a syntactic analysis of synthesis, which, by adopting a number of different tools from the syntactic inventory, claims that synthetic compounds are formed from parts that are syntactic ‘atoms’ and through processes that are independently motivated by purely syntactic mechanisms (see Fabb 1984; Sproat 1985; Roeper 1987, 1988).

Synthetic compounds are formed by at least three basic morphosyntactic units: the verbal head, a verbal argument (in most cases, the internal argument, but see below), and a derivational morpheme (usually a nominalizer) as in the following example from Greek:

1.

| pliroforio | - dho | -tis |

| information | - give | -er |

| ‘informer’ |

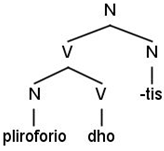

The structure immediately poses a bracketing problem: the verb forms a morphological constituent with its argument before the nominalizer applies, as in (2.a), or the compound is formed by two nominal elements, the verb plus nominalizer complex and the nominal argument, as in (2.b):

2.

| a. | b. |

|  |

The analysis of synthetic compounds as N–N root compounds (c.f. 2.b) has been proposed in several studies, most notably (Selkirk 1982; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; Ralli 1989; Booij 1988, 1992; Di Sciullo and Ralli 1999; and others). There are a few facts that seem to support the analysis. Languages such as English allow the formation of N–N compounds freely, and such formations are very productive in the language. On the other hand, N–V compounds, where the nominal element is the internal argument of the verb, seem to be very rare (Ackema and Neeleman 2005, p. 55). Thus, for proponents of the analysis in (2.b), the analysis in (2.a) cannot be maintained, as the first constituent is not a possible independent structure in the language. Similarly, the nominalizing suffix –tis merges productively with verbs to produce nominals and, therefore, both ingredients of the analysis in (2.b) are independently motivated.

The only potential problem for this analysis would be explaining the presence of a verb-internal argument in the configuration, i.e., the fact that the verbal base has one of its arguments saturated inside the compound:

3.

| * O Giorgos | ine | pliroforiodhotis | hrisimon | pliroforion. |

| D Giorgos | is | information.giver | useful | information.GEN1 |

| ‘Giorgos is an informer of useful information’. | ||||

In order to explain this, proponents of the analysis in (2.b) have to assume some sort of inheritance, whereby the internal argument of the verbal base is inherited by the nominalization. However, in cases where the argument is assumed to have been inherited by the verbal base, idiomatic readings are usually excluded (Ackema and Neeleman 2005, p. 56; Borer 2013, chp. 12):

4.

| a. | John has always made trouble. |

| b. | * John has always been a maker of trouble. |

On the other hand, synthetic compounds clearly allow for idiomatic readings to be maintained:

5. John has always been a troublemaker.

Thus, an argument-inheritance analysis is problematic. Finally, the analysis in (2.b) has nothing to say about the unavailability of N–V compounds, where N is the internal argument of V.

The presence of an internal-argument and the availability of idiomatic readings are not problematic for the proponents of the analysis in (2.a) (see, among others, Lieber 1983; Fabb 1984; Sproat 1985; Ackema and Neeleman 2005). In these proposals, the nominal argument merges directly with a verbal base, and thus, argument saturation is triggered by the independently motivated selectional restrictions on the verb. Locality of selection at that level would also explain the presence of idiomatic readings. However, this looks more and more like a syntactic configuration, and this has led some of the relevant research into the conclusion that the processes involved in synthetic-compound formation are independently motivated syntactic processes, and that there is no need for the involvement of a separate morphological component (Fabb 1984; Sproat 1985; Roeper 1987, 1988). In most of these analyses, the internal structure of synthetic compounds is assumed to be syntactic in nature, involving elements of the basic head level (Xo), which is an atom for the purposes of syntactic operations.

Greek synthetic compounds share the same order as English synthetic compounds, with the nominal argument being the leftmost sister of the compound, while the verbal base appears on the right, followed by derivational and inflectional (gender/number) morphology. A difference between English and Greek synthetic compounds lies in the presence of a ‘linking’ morpheme -o- that appears between the verbal domain and the nominal argument. Thus, (1) is better represented as:

6.

| plirofori | -o | - dho | -tis |

| information | LNK | - give | -er |

| ‘informer’ |

The existence of the linking morpheme seems to formally spell-out the compounding process, and its presence or not in a language may be related to the morphological and/or phonological properties of the language (Ralli 2007). In other approaches (c.f. Di Sciullo 2005), it is assumed to head a compound-internal functional projection that imposes an asymmetry in the way the compound elements relate to each other. I will not pursue this issue here, as it does not directly affect the analysis presented.

One of the first attempts to propose a syntactic analysis for a morphological process in Greek compounding is Rivero (1992), who, based on the general process of syntactic incorporation (via head-movement), as detailed in Baker (1988), proposed that Greek synthetic compounds whose first element is either a verbal argument or a manner adverbial involve nominal or adverbial incorporation to the verb. This analysis met with strong criticism (see, for example, Kakouriotes et al. 1997; Smirniotopoulos and Joseph 1997, 1998). The criticism against the analysis is based on a series of lexicalist arguments, including lexical integrity effects, semantic transparency, and productivity. In particular, the case of lexical integrity has been at the forefront of the polemic against syntactic analyses of synthetic compounding, most notably in the case of Greek synthetic compounds in the work of Ralli (1989, 1992, 1999, 2003, 2007); Ralli and Stavrou (1998); and Di Sciullo and Ralli (1999).

Lexical Integrity refers to the fact that ‘words’ (a concept generally resistant to a good working definition) seem to not be subjects to syntactic operations that apply to ‘sublexical’ (i.e., word-internal) elements (c.f. Lapointe 1980; Selkirk 1982; Bresnan and Mchombo 1995; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; Anderson 1992; Booij 2005; Spencer 2005 and others). Bresnan and Mchombo (1995, p. 181f), define lexical integrity as the fact that “syntactic principles do not apply to morphemic structures. Morpheme order is fixed, even when syntactic word order is free; the directionality of ‘headedness’ of sublexical structures may differ from supralexical structures; and the internal structure of words is opaque to certain syntactic processes.” Thus, lexical integrity is an umbrella term for the inapplicability of several different syntactic operations on sublexical elements, including inbound anaphoric islands, availability of phrasal recursivity, conjoinability, gapping, and displacement. Let us examine some of these cases with respect to Greek synthetic compounds.

Word parts, in general, are not possible links in chains, ruling out movement into and out of words (Chomsky 1970; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; Bresnan and Mchombo 1995).

7.

| a. | O | Giannis ine | plirofori-o-dotis. | |

| The | Giannis is | information- LNK-giver | ||

| ‘Giannis is an informer’. | ||||

| b. | * Ti | ine | o | Giannis dotis? |

| What | is | the | Giannis giver? | |

| ‘What is Giannis giver (of)? | ||||

| c. | * Ti | ine | o | Giannis plirofori(as)? |

| What | is | the | Giannis information(GEN)? | |

| ‘What is Giannis (of) information? | ||||

As we can see in (7.b), trying to question the leftmost element of a synthetic compound results in ungrammaticality, and thus, no wh-movement operation can displace a compound-internal element. A similar type of ungrammaticality is observed in attempting to wh-question the rightmost element in the compound 7.c).

A stronger lexical-integrity-based argument comes from the fact that words seem to be anaphoric islands—sub-lexical elements cannot be referential. Binding relations or coreference cannot relate elements below the word level to material external to the word (Postal 1969; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987):

8.

a. * O Giannis ine plirofori1-o-dotis alla den tin1 gnorizo.

The Giannis is information- LNK-giver but not 3SG.F know.1SG

‘Giannis is an informer but I don’t know it (the information)’.

b. * O kapn1-o-kalliergitis dhen katafere na ton1 poulisi fetos.

The tobacco- LNK-grower not managed to 3SG.M sell this.year

‘The tobacco-grower didn’t manage to sell it (the tobacco) this year’.

c. O Giannis edhose [mia pliroforia]1 ston Giorgo alla den tin1 gnorizo.

The Giannis gave.3SG an information to.the Giorgo but not 3SG.F know.1SG

‘Giannis gave some information to Giorgo but I don’t know what it is’.

In (8.a), the leftmost part of the compound, plirofori- (information) is supposed to be coreferential to the clitic pronoun tin, but the sentence is completely ungrammatical in Greek. Compare the grammatical sentence in (8.c), where the antecedent of the clitic is now a full independent DP. A second ungrammatical example is provided in (8.b), where the compound-internal nominal argument kapn- (tobacco) is supposed to bind the clitic pronoun ton.

A further argument from lexical integrity comes from the fact that coordination or gapping word-internally is not allowed (Bresnan and Mchombo 1995). Coordination of compound-internal elements would allow, for example, two or more nominal arguments to appear conjoined as the leftmost element in a compound:

9.

| * O Giannis | ine | plirofori | -o | (ke) | em-o-dotis. |

| The Giannis | is | information- | LNK- | (and) | blood- LNK- giver |

| ‘Giannis is an information-(and)-blood-giver’. | |||||

As (9) illustrates, this is not possible. One can argue here that the impossibility of (9) stems from the inability of the conjunction ke (and) to appear word-internally. However, Greek has so-called copulative compounds that seem to encode coordination:

10.

| alat-o-pipero |

| salt-LNK-pepper |

| ‘salt and pepper’ |

Given this property of Greek grammar, it could be possible to form a compound whose leftmost element is itself a copulative compound. However, as (11) illustrates, this is also impossible. While the copulative compound psomotiri (psomi+tiri, ‘bread+cheese’) and the synthetic compound tirofagos (tiri+fagos, ‘cheese+eater”) are both attested, the complex compound * psomotirofagos is not possible:

11.

| * O | Giannis | ine | psom-o-tir-o-fagos. |

| The | Giannis | is | bread-LNK-cheese-LNK- eater |

| ‘Giannis is a bread-cheese-eater’. | |||

Similarly, gapping constructions where the leftmost or rightmost elements of the synthetic compound are elided because of the presence of an antecedent in the immediately preceding environment are ruled out. Compare (12.a) to (12.b):

12.

| a. | O Giannis | kalliergi | kapno | ke | I | Mary | sitira. | |

| the Giannis | grows | tobacco | and | the | Mary | wheat | ||

| ‘Giannis grows tobacco and Mary wheat’. | ||||||||

| b. | * O Giannis | ine | ele-o-kaliergitis | (ke) | i | Mary | sitir-o- | |

| The Giannis | is | olive-LNK-grower | (and) | the | Mary | wheet- LNK | ||

| ‘Giannis is an olive-grower and Mary a wheat-grower’. | ||||||||

In (12.a), the verb in the second conjunct can be deleted (presumably, due to the fact that the verb is ‘given’ information), but no such deletion of the verbal base is available in the compound of (12.b) even though the context and, therefore, the informational makeup of the sentence remain the same.

A final issue arises with the distribution of definite determines and other elements that arguably make use of the D-projection of the noun phrase (pronouns, proper names, and so on). Definite determiners and referential nouns (pronouns and proper names) are, in general, excluded in synthetic-compound formation (c.f. Postal 1969; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; see Alexiadou 2020 for the unavailability of compounds with proper names in Greek):

13.

| a. | * [o kapno-] | kalierjia |

| [D tobacco-] | cultivation | |

| b. | * Giorgo-thavmastis | |

| Giorgo-admirer | ||

A final property of synthetic compounds that has been noticed is that, in most cases, additional arguments are excluded in synthetic compounds (c.f. Grimshaw 1990):

14.

| a. | emo-o-dotis |

| blood- LNK-giver | |

| b. | * nosokomi-o-emo-o-dotis |

| hospital- LNK -blood- LNK-giver | |

| ‘a hospital-blood-donor’ |

Ralli (2003) mentions the attested form agroto-danio-dotisi ‘farmer-loan-giving’, but I think that the agentive agrotodaniodotis is not attested, and this type of synthetic compound is extremely rare—in most cases (as in 11 and 14.b), these forms are ungrammatical. For a purely morphological analysis of compound formation, this is problematic, as, in most cases, compound formation is freely recursive, at least in languages like English. In the following section, recent advancements in syntactic theory will be implemented in order to explain these facts.

3. A Phrase/Phase-Based Analysis

Any syntactic analysis of synthetic-compound formation must necessarily start from three basic questions about the nature of compound structure. These include the nature of the building blocks in synthetic-compound formation; the base structure on which the derivational process proceeds; and the nature of the actual operations which derive the final synthetic compound structure. For a successful ‘morphology as syntax’ model of grammar, it is important that the syntactic principles that operate in synthetic-compound formation are general, independently motivated syntactic rules and not compound-specific processes.

3.1. The Status of Roots

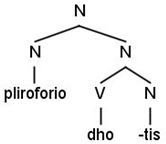

We assume here that the building blocks of compound formation include pre-categorial roots, which remain active throughout syntactic operations (such as internal or external merge). This is a standard assumption within earlier versions of the DM analysis of compounding, such as Harley (2009, 2014). Let us take the Greek synthetic compound pliroforiodhotis, ‘information-provider’, discussed in the previous section. Harley (2009) assumes the following structure for such a compound:

15.

A root predicate, dho (‘provide’), selects for a nominal argument, pliroforio (‘information’), and the root head moves to the predicate head (via head-movement). This root string is then nominalized by a category-assigning head, n, expressed as the nominalizing suffix -tis in Greek, and further head movement to the left of the nominalizing head derives the final synthetic compound structure.

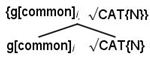

The structure assumed here departs from Harley’s (2009) structure in a number of ways. However, before discussing the details, it is important to revisit the syntactic status of the root here. In several approaches within DM, (see, for example, Arad 2003; Harley 2012; Wood 2021; Marantz 2021), all roots have to be categorized first before becoming visible for later syntactic operations, including the selection and licensing of arguments, and also in order to be interpreted (see Harley (2014) for a treatment of roots as active, argument-selecting syntactic objects, as well as response papers in the same volume, especially Alexiadou (2014), for arguments against such an approach). Thus, the structure of the compound above would be represented by a structure like (16), below (adapted from Wood 2021):

16.

The structure in (16) resembles the structures in (2) if one decomposes morphological labels such as N and V to ROOT+category-assigning-head (√+n and √+v, respectively). It seems then that these approaches form a retreat to a more morphology-like base syntactic structure, with argument structure projected after the categorization of heads has taken place.

However, such an analysis cannot be maintained, at least not for the Greek compound data. The form of the nominal argument within a Greek compound is not inflected for gender/number features. Such a form is illicit as a free form in the language:

17.

| a. | * i | plirofori | (-o) |

| b. | i | plirofori | -a |

| the | information | -F.SG.NOM |

All Greek nouns (with some exceptions, especially loanwords) need to be inflected with gender, number, and case morphology. Noninflected nouns are only allowed in compound-internal (or derivational) contexts (see Ralli 1992 for discussion). Marantz (2021) assumes that nouns are formed by a root attached to a gender feature, where gender would exhaustively classify nouns (partition the class of nouns) syntactically. Thus, a typical noun would have the following structure:

18.

In Marantz’s (2021) notation, √CAT{N} indicates a root that will become a noun (i.e., has a nominal predisposition) and g[common]i indicates a gender feature (where the subscript i identifies the specific set of phi features that this gender feature will be a member of). Thus, the little nominalizing n in Wood’s (2021) structure in (16) translates to the gender feature in Marantz’s structure in (18). If this is correct and based on the examples in (17), Wood’s structure cannot be accurate for Greek synthetic compounds such as pliroforiodhotis.

The root status of the non-head element in synthetic compounds has been clearly supported in work on Greek synthetic compounds presented in Iordachioaia et al. (2017), who assume that the initial merging of the Greek synthetic compound elements involves two roots, a “verbal” root and a “nominal” root, which saturates the internal argument of the former. In this account, the internal argument root incorporates into the verbal element. The timing of the incorporation process results in different back-formed N–V compounds in Greek: If incorporation happens before categorization of the verbal root by a v head, then the resulting N–V compound verb has idiosyncratic stress patterns and stem form (for example, vivli-o-detó, ‘to book-bind’; compare déno, ‘to bind’). However, if incorporation happens after verbal root categorization (to an already categorized verb) then the resulting N–V compound has the typical source verb stress pattern and stem form (for example, thiri-o-damázo, ‘to beast-tame’; compare damázo, ‘to tame’).

In addition to the morphological evidence for assuming the active presence of roots (without categorization layers) in Greek synthetic compounds, additional evidence of the presence of roots in compounding is provided in numerous other languages, including Dutch primary compounds (de Belder 2017), where it is clearly shown that primary compounds contain uninflected roots with generic (i.e., nonnominal) interpretations, or in Chinese (Zhang 2007), where the only possible derivation of exocentric compounds in Chinese is shown to involve the merger of bare roots without syntactic features (see Bauke 2014, chp. 2, for extended discussion of the presence of roots inside syntactically derived compounds).

We will assume then that the base structure of synthetic compounds in Greek involves a verbal predicate selecting for a root argument.

3.2. Merge and Licensing

In recent years, work within the minimalist program (Chomsky 1995 and later work) has assumed that syntactic derivations proceed in steps that interface with the phonological and interpretive components (‘phases’ in Chomsky 2001, 2005). In its initial implementation, Phase Theory assumed that the only possible phases are CPs and vPs (and possibly DPs, although this is left open in Chomsky 2001). Marantz (2001) extends the phase inventory to include every case where category-changing morphology attaches to a syntactic structure, changing the extended projection. Thus, every time a nominalizer attaches to a verbal string, it defines a new phase. In other work, the term phase is applied to each domain of the verb in which an argument is added (Sportiche 1999, 2005; Hallman 1997; Carnie and Barss 2006). Even though the notion of ‘phase’, and what the possible domains in which it applies are, is not completely clear yet, ‘phase theory’ has helped explain a number of problems within the syntactic component and has been applied to the analysis of morphological derivations with similar success, most notably in the work of Marantz (2001, 2006).

Furthermore, Sportiche (1999, 2005) puts forward a novel account of how verbal arguments acquire referential properties. The account is based on the assumption that selection is ‘strictly’ local. This means that predicates must select for bare NPs and that subsequent nominal layers (case, number, quantification) project outside the thematic domain and trigger movement of the argument NP to VP-external positions. Thus, a VP-internal argument is selected by the verb as an NP. It subsequently raises to number, case, and D projections outside the VP shell. The evidence that Sportiche (2005) provides for such a claim is drawn from reconstruction effects. Consider, for example, the following:

19. In 1986, no integer had been proved to falsify Fermat’s theorem.

Under current assumptions, the underlying structure for (19) would be something like (20):

20. In 1986, had been proved [no integer falsify Fermat’s theorem]

This structure should give rise to two different interpretations (depending on the scope of the determiner no with respect to the main predicate):

21.

a. In 1986, no integer x, it had been proved that x falsifies Fermat’s theorem

b. In 1986, it had been proved that no integer falsifies Fermat’s theorem

However, the second interpretation is not possible, which means that the quantifier does not reconstruct in its base position. Assuming that there is always reconstruction when there is a movement operation, Sportiche (2005) concludes that (20) is not an accurate underlying representation for (19), and it should change to (22):

22. No ……prove …[EMBEDDED CLAUSE integer falsify…]

Thus, surface structure is derived by movement of the NP integer to the projection that hosts the quantifier in order to be quantized. Since this is not DP movement, reconstruction is not possible, and the paradox is explained straightforwardly.

What does this predict with respect to the lexical integrity effects, which were discussed in the previous section? If the analysis is on the right track, then D-elements merge outside the verbal domain of ‘first merge’ between the verb and a unquantized nominal head. I propose that the domain of synthetic-compound formation (and, possibly, most ‘derivational’ processes) is exactly this ‘first merge’ domain (see, for example, ‘first phase syntax’, Ramchand 2003; see also Sportiche 1999 for a discussion of synthetic compounds). In other words, the domain of synthetic-compound formation includes the lower VP but no additional verbal functional layers.

Nominalizers (e.g., the agentive –er in English or –tis in Greek) merge at different levels in the syntactic spine, changing the categorial status of the projection from verbal to nominal (see Alexiadou 2001; Ntelitheos 2006, 2013 for different approaches on how this is achieved). In the case of synthetic compounds, the nominalizer merges directly above VoiceP (the projection where the external argument is licensed). Let us see how the proposed derivation is implemented.

3.3. Deriving Synthetic Compounds in Greek

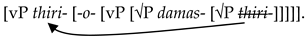

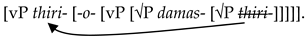

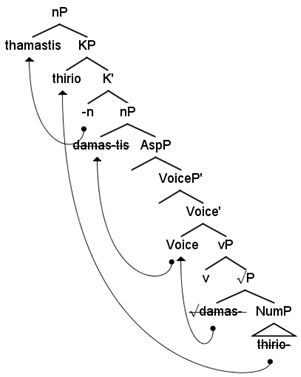

Consider the formation of thiriodamastis ‘beast-tamer’. The verb enters the derivation selecting its internal (THEME) argument in the lower vP: [vP [√P damas- [√P thiri-]]] (see also Iordachioaia et al. (2017), based on Harley 2009, 2014). The argument is a root, and thus, it has no nominal properties or nominal functional layers.

The string of the preverbal predicate selecting for a root argument defines a symmetrical structure where each head c-commands the other since there is no functional material to create antisymmetry. Delfitto et al. (2008) show that such structures are not licit, as they create a Point of Symmetry of two substructures that share the same structural complexity (in this case, two roots, but it could also be two nominalized roots or two larger identical structures). Delfitto et al. (2008) identify such symmetric structures as instances of Parallel Merge, which constitute a violation of the Linear Correspondence Axiom (LCA) of Kayne (1994), resulting in a structure that cannot be linearized (see Citko 2005; Delfitto et al. 2008; and Bauke 2014 for leftward movement as a symmetry-breaking mechanism for licensing purposes).

Therefore, the only way for the structure to be well formed is for the internal argument to move to a higher functional projection in order to be linearized. We propose that the movement of the internal argument in a synthetic compound to a preverbal position is triggered by such symmetry-breaking linearization requirements (see Barrie 2006 for a somewhat different discussion of these issues). This predicts that such movement can only be licit in the environment of real ‘root’ compounds, i.e., compounds in which two roots merge at the lower level of the derivation. If the compound involves a merger of an inflected predicate or a nominal argument (with gender and number morphology) then no such movement is predicted (unless there are other independent reasons that force inversion; see discussion in Ntelitheos and Pertsova (2019) for this asymmetry in primary/root compounds in several different languages).

Thus, the internal argument inverts over the verb to some licensing projection. We assume (following the discussion in Ralli 1992 and later work) that this projection is headed by the compound marker -o- in Greek. The status of this marker has received considerable discussion in the relevant literature (Ralli 1992, 2013; Booij 1992; Scalise 1992) where it is termed a ‘linking vowel’. The discussion in Ralli (2013) clearly shows that the linking element has the function to signal compound-formation processes, but only in the cases where the leftmost element of the compound is a root. The linking marker is dropped when this element is a fully (or partially) inflected word, e.g., in compounds borrowed from classical Greek:

23. angeli.a-foros

message.ACC-bringer

‘messenger’

As we will see in the following section, this is also the case in phrasal compounds in Greek, where the argument of the verb is an inflected nominal, and thus, licensing is achieved via adjacency and not through inversion over the linker -o-.

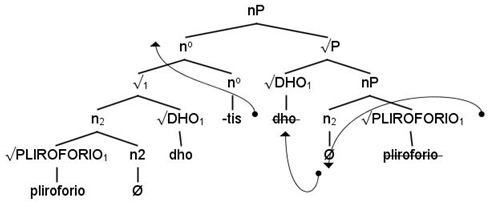

Returning to the derivation of Greek synthetic compounds, the current step in the derivation is as in (24):

24.

At this point, the nominalizer merges, changing the projection from verbal to nominal. The nominalizer in the case of the agentive nominal thiriodamastis/‘beast-tamer’ expresses the external theta-role of the verb. This means that the nominalizer merges above the projection where the external argument is licensed. Based on observations in Kratzer (1994) and subsequent work (see, among others, Cuervo (2003); Collins (2005); Alexiadou et al. (2006); Merchant (2008); Harley (2009)), we assume that the external argument is projected in the specifier of a separate projection VoiceP, which may additionally be the locus for voice morphology in passive voice structures. The lower vP projection maintains the role of verbalizing the root domain but may also carry semantic (and morphological) content with the introduction of causative or inchoative semantics (see, for example, Cuervo 2003 for detailed discussion of the different flavors of little v). The structure, thus, is as follows:

25. [np tis [VoiceP [vP thiri- [-o- [vP [√P damas- [√P thiri-]]]]]]]

The approach proposed here differs from the incorporation analysis of Iordachioaia et al. (2017), based on Harley (2009, 2014), in at least two crucial ways. Firstly, the agentive synthetic compound order of compound-internal elements is not achieved through incorporation but through phrasal movement of the root internal argument over the linking element -o-. This means that the linker plays an active syntactic role (in the sense of den Dikken 2006), and it is not simply a phonological reflex (as in Ralli 2013). Secondly, the agentive interpretation of the resulting synthetic compound is achieved through a type of reduced relative clause formation. Thus, the suffix -tis is assumed to be a relative pronoun of sorts, with the meaning ‘one (m.sg) who’. In Iordachioaia et al. (2017), the agentive nominalizing suffix (e.g., -er in English) is assumed to bind an external argument variable, <x>, introduced by the Voice projection (Schäfer 2008; Alexiadou and Schäfer 2010). However, a relative clause analysis does not presuppose the existence of an external argument and thus can potentially unify all cases where the affix is used with similar semantics, e.g., in non-verbal contexts (‘three-footer’, ‘Londoner’, or Greek politis, ‘citizen’, from poli, ‘city’, and anatolitis, ‘easterner’, from anatoli, ‘east’).

Subsequent movement of VoiceP to spec-nP is driven by the fact that the nominalizer is a bound morpheme, entering the derivation with the relevant morphophonological selection information. What is important here is that the nominalizer changes the properties of the extended projection from verbal to nominal and the distribution of the final string is that of an NP. Ntelitheos (2006, 2013) provides a discussion of the mechanisms involved in nominalization processes of this type, but the general idea here is that the higher nP is, in fact, a type of relative clause, with the suffix -tis acting as a relativizer attracting the external argument of the verb (or is, in fact, itself a relativized external argument of the verb in some languages). This straightforwardly provides the sematic interpretation of these strings as ‘one who V(P)s’, e.g., ‘one who tames beasts’. In such an account, an agentive nominalization (of the type involved in these compounds) is a reduced and headless relative clause where the agentive argument is null. However, this does not exclude the case where a similar structure could be formed with an overt nominal as the agent. Thus, a ‘repairer’ is ‘one who repairs’ and a ‘repairman’ is a ‘person who repairs’ (allowing for a gender-neutral interpretation of the gendered compound). Wood (2021) proposes that the two strings (the derived nominal and the compound) must have different structures, given the incompatibility of parallel examples:

26. a. a frequent watcher of the movies

b. * a frequent watchman of the movies

However, the problem here may be the semantic incompatibility of the internal argument, given the semantically nontransparent meaning of man-compounds. Thus, watchman is not ‘man who watches’ in general but ‘man who works as guard’, and an internal argument may be forced if it is ‘something that can be guarded’:

27. John is a government-appointed watchman of the district school.

Several similar examples can be found with other compounds of this type: ‘a repairer of TVs’ vs. ‘a repairman of TVs’ and, even better, as a compound: ‘a TV repairman’.

Returning now to the derivation of (25), what predictions, if any, does this derivation make? This being a syntactic derivation, the fact that the leftmost element in the compound is interpreted as an argument of the verbal base follows directly from the derivational process: thiri- is the internal argument of the verb and is selected directly by it within the VP. This predicts the exclusion of additional internal arguments in the structure:

28.

| * O Giannis | ine | thiriodamastis | liontarion. |

| The Giannis | is | beast-tamer | lions.GEN |

| ‘Giannis is a beast-tamer of lions’ | |||

More importantly, most lexical integrity effects follow directly. As has been noted in the previous section, most lexical integrity effects are directly related to the referential properties of the internal (‘sublexical’) argument. However, if Sportiche’s (1999, 2005) proposal is on the right track, and the internal argument enters the derivation without any referential properties, then these effects disappear.

Let us revisit the relevant examples. We have seen that synthetic compounds seem to be anaphoric islands (8, repeated here as 29):

29.

| * O Giannis | ine | plirofori1-o-dotis | alla den tin1 gnorizo. |

| The Giannis | is | information- LNK-giver | but not 3SG.F know.1SG |

| ‘Giannis is an informer but I don’t know it (the information)’. | |||

It is well known in the relevant literature that only DPs (i.e., ‘quantized’ nominals) can be referential; NPs never can (cf. Stowell 1991; Longobardi 1994). If the nominal inside the synthetic compound has not been quantized (due to lack of the appropriate projections) then its inability to bind/co-refer with a compound-external referential expression follows straightforwardly.

The fact that the internal argument cannot be quantized is further supported by its inability to host determiners or proper names and pronoun internal arguments 13, repeated here as 30):

30.

| a. | * [o kapno-] | kalierjia |

| [D tobacco-] | cultivation | |

| b. | * Giorgo-thavmastis | |

| Giorgo-admirer | ||

However, there are certain derivational processes, including compounding, that seem to allow for some proper names to be included in the resulting forms (see Lees 1960; Lieber 1983; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; and others):

31.

a. a Nixon admirer

b. the Euler number

c. my computer is an IBM machine

However, as Di Sciullo and Williams (1987) show, this is not possible with any proper name:

32. * a Bill admirer

It is therefore possible that the proper name inside the compound is not fully referential—it does not refer to the respective entity in the real world but rather to a specific property of that entity (e.g., in the case of ‘Nixon admirer’, to the policies of Richard Nixon). For Greek synthetic compounds, Alexiadou 2020 shows that a limited number of compounds, formed on verbal root heads that are remnants from earlier historical stages in the language (e.g., -ktonos, ‘killer’, or -latris, ‘admirer’), allow for proper names as non-head compound elements. However, she supports an analysis of these as formed on bound roots, which have achieved (or are on the way of achieving) an affixal status in the language. Thus, the fact that Greek synthetic compounds do not readily allow for the inclusion of proper names as non-head elements in the compound can be maintained. Alexiadou (2020) shows that this contrasts with English, where synthetic compounds do allow the inclusion of proper names as non-heads (as in 31). This is because, in her analysis, English synthetic compounds are formed on already categorized nominal elements (nPs) and not roots (or semi-affixes, in her analysis), as we have been arguing for Greek synthetic compounds (see Alexiadou 2020 for further discussion).

Moving to other types of integrity effects, we have noted that no movement is allowed out of the compound 7, repeated here 33):

33.

| a. | O | Giannis | ine | plirofori-o-dotis. |

| The | Giannis | is | information- LNK-giver | |

| ‘Giannis is an informer’. | ||||

| b. | * Ti | ine | o | Giannis dotis? |

| What | is | the | Giannis giver? | |

| ‘What is Giannis giver (of)? | ||||

In Bresnan and Mchombo (1995), this inability is taken as one of the main lexical integrity effects. However, the problem here is that there are numerous, clearly syntactic structures that disallow such movement. The effect observed in (33) is a case of the well-known left-branch extraction (Ross 1967), which the following example also exhibits:

34.

a. I like green apples.

b. * Which do you like apples?

Other types of extraction unavailability can also be accounted for because of the phasal status of the synthetic compound. The Phase-Impenetrability Condition (Chomsky 2001, 2005) assumes that at each step of the derivation, the only elements available to subsequent syntactic operations are the head and specifier of the phase. This means that, for elements inside the compound, the rightmost element is not available for subsequent computations, as it resides below the phase head (i.e., the nominalizer). Thus, neither the leftmost nor the rightmost elements of the compound can move for independent reasons, and thus, the effect disappears.

The unavailability of N–V compound verbs (i.e., noun incorporation) is due to the fact that, when the nominalizing affix is not projected, and the domain (and extended projection) remains verbal, the nominal argument would be forced to vacate the VP and check quantificational properties in the subsequent available projections. The only reason this is not a possibility in synthetic compounds is because the projection where definiteness is checked is not available because the nominalizer has altered the extended projection. This has to be a language–specific property—in cases of noun incorporation (e.g., in polysynthetic languages), the nonreferential nominal can be licensed inside the VP. In addition, this predicts something that has not really been discussed in detail in the relevant literature. The only cases that are brought forward as examples for the unavailability of noun-incorporation (in English and other languages of this type) are infinitival or finite forms of the verb:

35.

a. * to truck-drive

b. * The farmer occasionally tobacco-produces.

However, when slightly nominalized forms of the verb are used (e.g., gerundive forms in progressive contexts) then incorporation seems to be okay:

36.

a. I’d download his podcast when I was truck driving part time.

b. We have been window cleaning in Dudley and Stourbridge for 13 years.

c. I was truck driving up north, too.

There are several examples of this type available, many appearing in simple web searches (36.a-36.b) or in the Corpus of Contemporary American English 36.c). This is predicted in the analysis proposed here, as the suffix -ing nominalizes the verbal structure, allowing for incorporation of the internal argument; then, the copular verb BE verbalizes this nominal structure again, allowing for subsequent verbal projections (aspect and tense) to merge. The issue of noun-incorporation of this type in English, therefore, needs to be explored in more detail, beyond quick dismissals based simply on the data of (35.a-35.b).

Finally, Iordachioaia et al. (2017) show that, in the case of Greek synthetic compounds, N–V verbs are available in many cases, but their existence is subject to certain restrictions. Greek has three types of synthetic compounds depending on whether they allow for backformed NV verbs or not: synthetic compounds that do not have any N–V verbs (e.g., anth-o-polis, ‘flower-seller’ vs. * anth-o-polo, ‘to flower-sell’); synthetic compounds which can derive backformed N–V verbs with idiosyncratic stress patterns and stem forms (e.g., vivli-o-detis, ‘book-binder’ and vivli-o-detó, ‘to book-bind’; compare déno, ‘to bind’); and synthetic compounds with independent N–V compounds with the expected verb stems and stress patterns (e.g., thiri-o-damastis, ‘beast-tamer’ and thiri-o-damázo, ‘to beast-tame’; compare damázo, ‘to tame’).

The status and availability of N–V backformed verbs for these types of synthetic compounds need to be further explored (see Iordachioaia et al. (2017) for an analysis of what restricts the availability of these patterns in Greek).

4. Phrasal Compounds

Greek exhibits a type of phrasal structures that seem to have a limited number of compound-like properties. In these structures, the internal argument appears following the deverbal nominal in genitive case (Anastasiadi-Symeonidi 1983; Horrocks and Stavrou 1989; Ralli 1992, 2003, 2007, 2013):

37.

| a. | kalliergitis | kapnou |

| grower | tobacco.SG.GEN | |

| ‘grower of tobacco’ | ||

| b. | damastis | thirion |

| beast.PL.GEN | ||

| ‘beast tamer’ | ||

Phrasal compounds exhibit mixed lexical and phrasal properties: they share with synthetic compounds the properties of not allowing D-elements (38.a-38.b) and occasional non-compositional semantics (39):

38.

| a. | * kalliergitis | tou | kapnou |

| grower | D | tobacco.SG.GEN | |

| ‘grower (of) the tobacco’ | |||

| b. | * damastis | ton | thirion |

| tamer | D | beast.PL.GEN | |

| ‘tamer (of) the beasts’ | |||

39.

| epexergastis | dhedhomenon |

| processor | data.PL.GEN |

| ‘processor (of) data’ | |

However, contrary to synthetic compounds, phrasal compounds of this sort allow for argument modification (40.a-40.b), exhibit default syntactic word order with the argument following the predicate (37.a-37.b, 39), the internal argument appears with morphological genitive case as well as number and gender morphology (37.a-37.b, 39), and the structure defines two distinct prosodic domains for stress assignment.

40.

| a. | epexergastis | neon | dhedhomenon |

| processor | new | data.PL.GEN | |

| ‘processor (of) new data’ | |||

| b. | ekpobi | dhilitiriodhon | aerion |

| release | poisonous.PL.GEN | gas.PL.GEN | |

| ‘release (of) poisonous gasses’ | |||

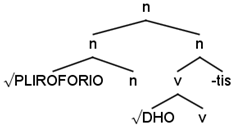

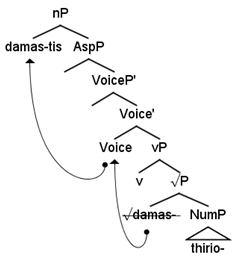

It is obvious here that the compound contains a verbal argument with further nominal layers above just the root. The theme arguments in the examples above are fully inflected for gender, number, and case. This indicates the presence of a category-assigning projection nP (which we can assume also encodes gender features) and at least a projection for number features (but, crucially, no projection KP associated with unspecified Case features; see Levin 2015):

41.

The tree represents the structure of Argument Supporting Nominals (ASNs) with a dispositional meaning, as proposed in (Alexiadou and Schäfer 2010; Alexiadou 2017). In the projection, AspP is an aspectual projection that hosts certain adverbial modifiers, available with these kinds of nominals. The internal argument is a NumP with expressed number properties, but which is unquantized in the sense of Sportiche (1999, 2005; see Section 3.2). In their analysis, the types of objects that are excluded in dispositional nominals are those that have definite and/or specific readings, i.e., DPs and, thus, the bare plurals found in the context of phrasal compounds proposed here are acceptable in dispositional contexts. The derivation proceeds as with a normal syntactic verb phrase up to this point. In verb syntax, the next step would be to license the nominal in a structural case KP position valuing case features, followed by a determiner (e.g., definiteness) projection with final movement of the verb to a higher projection, resulting in a typical VP structure with a definite object. However, the process is here, again, interrupted by the nominalizer, which triggers movement of the verbal predicate to its specifier (see tree above). At this point, KP can attach outside the nominalized string attracting the internal NumP argument. This means that the case will be manifested as the nominal case, which, in Greek, is morphologically marked as the genitive case with the suffix -n. Finally, this is followed by movement of the nP damastis to the specifier of KP, resulting in the final word order damastis thirion. This type of case licensing outside the verbal domain with the use of case projections (and prepositional complementizers as probes, in the case of the prepositional case assignment) is proposed in Kayne (2000) (see Kayne 2010, pp. 182–83, for details on the different steps of these nominalization processes and how case licensing and linking is established):

42.

The proposal explains the word order without further stipulations. Final word order is achieved following the same mechanisms that apply to more straightforward nominal structures, bringing the predicate to the left of its argument. The final structure contains some of the functional material that is available in the verbal domain, namely, NumP, and thus exhibits more ‘syntactic’ properties, in that it provides the space for possible adjectival modification or syntactic coordination (i.e., recursive structures of any sort). Motivation for the movement to a KP position may be again enforced by the need to break an antisymmetric structure. The initial merger of the verb root with NumP creates a symmetric structure that cannot be interpreted. Case licensing in these cases, then, is a way to create antisymmetry in the structure and allow the resulting derivation to be linearized.

The fact that the nominal has a richer functional structure dominated by a NumP projection, before nominalization has taken place, explains the presence of inflectional morphology on the noun. However, the theme argument is interpreted as a generic plural and not as specific/definite. This is because the argument is not fully quantized (in Sportiche’s (1999, 2005) sense) given that the DP and KP projections are missing from the structure. The corresponding syntactic verbal phrase with projected accusative case is:

43.

| kallierg-o | kapn-a |

| grow-1SG.PRS | tobacco.PL.ACC |

| ‘I grow tobacco’ | |

The addition of the definite determiner would imply a specific type of tobacco and would normally be followed by a relative clause further specifying the argument:

44.

| kallierg-o | ta kapn-a | pou hrisimopii | o | ASSOS |

| grow-1SG.PRS | tobacco.PL.ACC | that use.3SG.PRS | the | ASSOS |

| ‘I grow the tobacco that ASSOS uses (in its cigarettes)’ | ||||

Therefore, the existence of an indefinite plural in these cases is not a property of the phrasal compound but of the more general syntactico-semantic properties of the construction. Thus, in general, there is nothing that distinguishes these strings from common noun phrases, and this also explains the stress-patterns observed in these strings. The nominalizer dominates two phases: the nP domain of the nominal argument and the nominalized domain of the full structure (the nP). Marantz (2001, 2006) proposes that category-changing morphology defines a spell-out domain (a phase). Marvin (2003) examines the prosodic properties of words and puts forward the idea that each phase (inside a word) defines its own prosodic domain for the purposes of stress assignment.

Following these proposals, stress in Greek synthetic and phrasal compounds is predicted to differ. Synthetic compounds define a unique phase (the nominalizer merges immediately above the root domain), and there is no DP argument. This predicts that synthetic compounds will have a single primary stress:

45.

| a. | kapnokaliérjia |

| ‘tobacco cultivation’ | |

| b. | thiriodamastís |

| ‘beast tamer’ |

Phrasal compounds, on the other hand, define two nominal phases: the lower nominal phase of the internal argument (nP), and the higher nominal phase dominated by the nominalizer n (nP). Thus, two prosodic domains are defined, and this predicts two primary stresses:

46.

| a. | kaliérjia | kapnoú |

| cultivation tobacco.GEN | ||

| b. | damastís | thiríon |

| tamer | beast.PL.GEN | |

Alexiadou (2017) proposes that the strings discussed here are not “phrasal compounds” (of a specific type) and, while accepting a richer syntactic structure for them, proposes that they are dispositional (ASNs), in the spirit of Alexiadou and Schäfer (2010). As discussed above, (see tree in (41) and discussion there), we adopt the proposal that the compounds discussed here and in Alexiadou and Schäfer (2010) are in fact dispositional ASNs. The internal argument in these compounds has not been quantized and has the properties of a generic noun, thus providing a dispositional interpretation. Alexiadou (2017) provides several arguments that clearly show that the target compounds have different properties with respect to diagnostic tests, such as reversibility and insertion of parentheticals. The examples provided in support of this argument do include action nominals with the properties of dispositional ASNs. However, the data here becomes slightly peculiar, showing that, while both ASNs and agentive phrasal compounds (as discussed here) have the interpretation of dispositional nominals, their behavior with respect to the tests is different. For example, one of the main arguments in Alexiadou 2017 against a phrasal compound analysis for these strings is the possible reversibility of the elements in these compounds (47.a), as opposed to ‘true’ phrasal compounds of the type in (47.b), where the order is not reversible:

47.

| a. | epeksergasia | dedomenon | dedomenon | epeksergasia |

| processing | data.GEN | data.GEN | processing | |

| b. | zoni asfalias | * asfalias | zoni | |

| belt safety.GEN | safety.GEN | belt | ||

However, the argument does not hold for the phrasal compounds discussed here, which are based on agentive nominalizations of a verbal structure. There is no reversibility attested with these compounds:

48.

| a. | O | Giannis | ine | kalliergitis | kapnou | * kapnou kalliergitis2. |

| The | Giannis | is | grower | tobacco.GEN | ||

| ‘Giannis is a tobacco-grower’. | ||||||

| b. | Htes | gnorisa | ena | thamasti | thirion/ * thirion thamasti. | |

| Yesterday met.1SG | a | tamer | beast.PL.GEN | |||

Thus, while all strings above are dispositional ASNs, the strings in (48.a-b) must be phrasal compounds. A second argument Alexiadou (2017) presents against a phrasal compound analysis of these strings is the possibility of inserting parentheticals between the two elements of the phrasal compound. This is true for the examples with action nominals of the type in (47) but not for agentive nominals of the type in (48), which, again, do not seem to easily allow the insertion of parentheticals (when used as profession name holders, for example):

49.

| a. *? | O | Giannis | ine | kalliergitis | opos | vlepete | kapnou |

| The | Giannis | is | grower | as | see.2PL | tobacco.GEN | |

| ‘Giannis is a tobacco–(as you see)-grower’. | |||||||

Other apparent counterarguments that Alexiadou (2017) provides against a phrasal compound analysis fall in the same category—they work very well with dispositional action ASNs of the type discussed there but seem to fail with the phrasal compounds discussed here. These include the (un)availability of passive phrases (* kalliergitis kapnou apo ergates, ‘grower (of) tobacco by workers’, which is excluded independently as the external argument interpretation of the compound excludes a by-phrase) and resistance to pluralization (kalliergites kapnou, ‘tobacco-growers’). We believe that the data supports an analysis of the agentive strings discussed here as a type of dispositional ASNs that are phrasal compound, in the broader sense, which assume a specific complex ‘phrasal’ structure (i.e., involving a root plus additional functional projections) with properties that may be somewhat different than what Alexiadou (2017; following Ralli 2007) terms ‘phrasal compounds’ (of the zoni-asfalias type).

The significance of phrasal compounds of this sort lies in their frequent tendency to appear with nontransparent, idiomatic meanings. Ralli (2007, pp. 245–46) accepts that this is problematic for her proposal of a distinct morphological component of the grammar and, rather, seems to indicate a grammatical continuum where synthetic compounds reside at the lowest, strictly morphological level, followed by ‘loose’ compounds (in her terminology) that have a limited number of syntactic properties, followed by semantically nontransparent ‘phrasal’ compounds, with syntactic phrases occupying the other extreme.

The problem for proponents of the lexicalist approach is, of course, a lot more serious. One of the strongest arguments against syntactic analyses of previously-thought-to-be morphological processes has been the frequent nontransparent interpretations of derived strings (see Chomsky 1970 and most work in the ‘lexicalist tradition’ that followed). However, if there are parallel, purely syntactic strings that exhibit similar semantic opacity to morphologically derived strings to the same or greater extend, then the argument against syntactic analyses of morphological derivational processes, such as compounding, disappears.

The analysis proposed here does not face such a problem. The continuum that Ralli (2007) acknowledges is encoded in the proposed structures. Synthetic compounds are formed at the ‘first merge’ lower syntactic domain, the most basic available domain that contains no functional layers yet. This is the domain of lexical idiosyncrasies, which Marantz (2006) calls the domain of ‘inner word formation’ as contrasted with the domain of ‘outer word formation’, the contrast defined by the cyclic interpretation imposed by phases, given that each category-determining head defines a phase. The domain of synthetic-compound formation or root domain is closed by the first category-determining head and constitutes what Ramchand (2003) calls the ‘first-phase syntax’.

Thus, the inner domain is the domain of potential forms with fixed idiosyncratic meaning and syntactically corresponds to the domain determining the category of the resulting structure. The idiosyncratic properties of synthetic and phrasal compounds follow straightforwardly: in both cases, the first category-defining morpheme (the nominalizer) attaches above the domain where compositional meaning is fixed. In the derivation of normal syntactic phrases, on the other hand, all additional functional projections merge on top of different category-assigning morphemes for the verb (vP) and the nominal argument (nP), and thus, the meaning is predictable from the structure.

5. Conclusions

I have argued for a purely syntactic approach to agentive deverbal compound formation in Greek. The differences in the distribution of different compound forms, including synthetic and phrasal compounds, were shown to be derived from the properties of the lower verbal domain and the idiosyncratic selectional properties of nominalizing affixes.

Following (Sportiche 1999) and previous work in the formation of deverbal compounds of this type in Greek (Alexiadou 2017; Iordachioaia et al. 2017), I propose that the domain of compound formation is the lower vP, where v verbalizes a root domain that contains the root and a single argument that has not been quantized (i.e., become referential yet) (Sportiche 1999). In synthetic compounds, the internal argument is also a root, and the word order properties of the resulting compound are derived from a need to create an antisymmetric structure, forcing the root argument to move to the specifier of a linking element above vP for licensing purposes. The nominalizer generates a reduced, headless relative clause structure that enforces the correct, agentive, interpretation (‘one who Vs’). The proposal explains a number of facts about synthetic compounds and, in particular, lexical integrity effects and the definition of prosodic domains.

In the domain of phrasal compounds, a similar structure is generated by a root predicate, selecting this time for a larger nominal constituent: a NumP with number properties, which, however, has not been quantized yet and cannot have a definite/specific interpretation. This creates a phrasal string with dispositional semantics but without the robust phrasal properties of a fully layered syntactic phrase, i.e., a phrasal compound in the terminology adopted here. A similar licensing mechanism, this time with the projection of a KP assigning nominal genitive case, licenses the internal NumP argument and breaks the initial symmetric structure of the root-NumP merge. The proposed structure explains the mixed semiphrasal properties and stress patterns of the resulting strings as well as their ‘compound’-like distribution.

A number of residual issues remain. For example, the contrast between (4.b) and (5) in the introduction, concerning the unavailability of idiomatic readings for ASNs in English, even though the latter are available in the corresponding synthetic compounds, has not been discussed here. A similar contrast does not exist between agentive synthetic and phrasal compounds in Greek, but see Iordachioaia et al. 2017 for extensive discussion on how this asymmetry can be captured by the different status of the internal arguments involved in these structures: idiomatic compounds are formed on ROOT–ROOT sequences, while the corresponding ASNs are formed on ROOT–nP sequences. As a result, different readings with respect to semantic transparency can be obtained by the two types of strings, as they do with the possibility for N–V-backformed verbs (discussed here in Section 3.3; see Iordachioaia et al. 2017 for detailed discussion of these issues).

A second residual issue not pursued further here is the observed microvariation on distributional properties between the agentive phrasal compounds discussed here and the ‘phrasal’ compounds of the type discussed in Ralli (2007) and Alexiadou (2017). We leave this for future work, stressing, however, how the mere existence of such different types of compound-like elements, with various morphosyntactic properties across a scale from more word-like to more phrasal-like strings, provides strong support for a syntactic analysis of these compounds, resulting from syntactic structures with different levels of complexity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Glossing follows the general Leipzig Glossing Rules: GEN (genitive case); LNK (linker); SG (singular number); PL (plural number); F (feminine gender); ACC (accusative case); PRS (present tense); 1, 2, 3 (first, second, and third person). |

| 2 | It is possible to allow for a reverse structure if contrastive focus is added. Thus, one can possibly say: (i) O Giannis ine THIRION damastis, ohi alogon. The Giannis is BEASTS.GEN tamer, not horses.GEN “Giannis is a beast-tamer, not a horse-(tamer).” If contrastive focus is allowed, however, even ‘real’ phrasal compounds such as praktorio idiseon, ‘agency news’, can be reversible: (ii) IDISEON praktorio ehi o Giannis, ohi lahion NEWS.GEN agency has the Giannis, not lottery-tickets.GEN ‘Giannis has a news-agency not a lottery-ticket one’. Example (i), above, additionally shows that the phrasal compound-internal verbal predicate can be elided, further supporting the phrasal status of these strings. |

References

- Ackema, Peter, and Ad Neeleman. 2005. Beyond Morphology. Interface Conditions on Word Formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, and Florian Schäfer. 2010. On the syntax of episodic vs. dispositional -er nominals. In The Syntax of Nominalizations across Languages and Frameworks. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou and Monika Rathert. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2001. Functional Structure in Nominals: Nominalization, and Ergativity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2014. Roots don’t take complements. Theoretical Linguistics 40: 287–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2017. On the complex relationship between deverbal compounds and argument supporting nominals. In Aspect and Valency in Nominals. Edited by Anna Malicka-Kleparska and Maria Bloch-Trojna. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2020. On the morphosyntax of synthetic compounds with proper names: A case study on the diachrony of Greek. Word Structure 13: 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2006. The properties of anticausatives crosslinguistically. In Phases of Interpretation. Edited by Mara Frascarelli. Berlin: Mouton, pp. 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadi-Symeonidi, Anna. 1983. La Composition en Grec Moderne d’un Point de Vue Diachronique. Lalies 2: 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Stephen R. 1992. A-Morphous Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Maya. 2003. Roots and Patterns. Studies in NLLT. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark. 1988. Incorporation: A Theory of Grammatical Function Changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrie, Michael Jonathan Mathew. 2006. Dynamic Antisymmetry and the Syntax of Noun Incorporation. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Bauke, Leah S. 2014. Symmetry Breaking in Syntax and the Lexicon. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, Geert. 1988. The relation between inheritance and argument linking. In Morphology & Modularity. Edited by Martin Everaert, Riny Huybregts and Mieke Trommelen. Dordrecht: Foris, pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, Geert. 1992. Compounding in Dutch. Rivista di Linguistica 4: 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, Geert. 2005. The Grammar of Words. An Introduction to Linguistic Morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, Hagit. 2013. Taking Form. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bresnan, Joan, and Sam Mchombo. 1995. The lexical integrity principle: Evidence from Bantu. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13: 181–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caha, Pavel. 2009. The Nanosyntax of Case. Ph.D. thesis, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Carnie, Andrew, and Andrew Barss. 2006. Phases and Nominal Interpretation. Research in Language 4: 127–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1970. Remarks on Nominalizations. In Readings in English Transformational Grammar. Edited by Roderick A. Jacobs and Peter S. Rosenbaum. Waltham: Blaisdell, pp. 184–221. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by Phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language. Edited by Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2005. On Phases. Cambridge: MIT, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Citko, Barbara. 2005. On the nature of merge: External merge, internal merge, and parallel merge. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 475–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Chris. 2005. A smuggling approach to the passive in English. Syntax 8: 81–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Chris, and Richard Kayne. 2020. Towards a Theory of Morphology as Syntax. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo, María Cristina. 2003. Datives at Large. Doctorate dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- de Belder, Marijke. 2017. The root and nothing but the root: Primary compounds in Dutch. Syntax 20: 138–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfitto, Denis, Antonio Fábregas, and Chiara Melloni. 2008. Compounding at the Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 39th Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS 39). Edited by Suzi Lima, Kevin Mullin and Brian Smith. Amherst: GLSA Publications, pp. 255–69. [Google Scholar]

- den Dikken, Marcel. 2006. Relators and Linkers. The Syntax of Predication, Predicate Inversion, and Copulas. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sciullo, Anna Maria, and Angela Ralli. 1999. Theta-role saturation in Greek deverbal compounds. In Studies in Greek Syntax. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou, Geoffrey Horrocks and Melita Stavrou. Dordrecht: Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sciullo, Anna Maria, and Edwin Williams. 1987. On the Definition of Word. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sciullo, Anna Maria. 2005. Asymmetry in Morphology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fabb, Nigel. 1984. Syntactic Affixation. Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Ludovico. 2011. A Nanosyntactic Account of Romance VN Compounds. Venezia: Università Ca’ Foscari, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, Jane. 1990. Argument Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The View from Building 20. Edited by Ken Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 111–76. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, Morris. 1997. Distributed Morphology: Impoverishment and Fission. In PF: Papers at the Interface. Edited by Benjamin Bruening, Yoonjung Kang and Martha McGinnis. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, pp. 425–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman, Peter. 1997. Reiterative Syntax. In Clitics, Pronouns and Movement. Edited by James R. Black and Virginia Motapanyane. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 87–131. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Heidi. 2009. Compounding in distributed morphology. In The Oxford Handbook of Compounding. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 129–44. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Heidi. 2012. Semantics in Distributed Morphology. In Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning. Edited by Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger and Paul Portner. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Heidi. 2014. On the identity of roots. Theoretical Linguistics 40: 225–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, Geoffrey, and Melita Stavrou. 1989. Clitics and Demonstratives in Noun Phrases. In Studies in Greek Linguistics. Thessaloniki: Kyriakidis. [Google Scholar]

- Iordachioaia, Gianina, Artemis Alexiadou, and Andreas Pairamidis. 2017. Morphosyntactic sources for nominal synthetic compounds in English and Greek. Journal of Word Formation 1: 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordachioaia, Gianina. 2019. English deverbal compounds with and without arguments. In Proceedings of the Fifty-fourth Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Edited by Eszter Ronai, Laura Stigliano and Yenan Sun. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, pp. 179–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouriotes, A., M. Papastathi, and A. Tsangalides. 1997. Incorporation in Modern Greek: Lexical or Syntactic? In Proceedings of the Second International Conference of Greek Linguistics. Edited by Gaberell Drachman, Angeliki Malikouti-Drachman, Celia Klidi and Jannis Fykias. Graz: Neubauer Verlag, pp. 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard. 2000. Parameters and Universals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard. 2010. Comparisons and Contrasts. Oxford Studies in Comparative Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, Hilda. 2005. Korean (and Japanese) morphology from a syntactic perspective. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 601–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, Angelika. 1994. The Event Argument and the Semantics of Voice. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe, Steven. 1980. A theory of Grammatical Agreement. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, Robert B. 1960. The Grammar of English Nominalizations. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Theodore Frank. 2015. Licensing without Case. Ph.D. thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, Rochelle. 1983. Argument Linking and Compounding in English. Linguistic Inquiry 14: 251–86. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, Giuseppe. 1994. Reference and Proper Names: A Theory of N-Movement in Syntax and Logical Form. Linguistic Inquiry 25: 609–65. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2001. Words. Cambridge: MIT, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2006. Phases and Words. New York: NYU, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2021. Rethinking the Syntactic Role of Word Formation. New York: New York University, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, Tatjiana. 2003. Topics in the Stress and Syntax of Words. Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Jason. 2008. An asymmetry in voice mismatches in VP-ellipsis and pseudogapping. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 169–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntelitheos, Dimitrios, and Katya Pertsova. 2019. Root- and Semiphrasal Compounds: A Syntactic Approach. Paper presented at Linguistic Society of America vol. 4, 2019 Annual Meeting, New York City, NY, USA, January 5–8; Edited by Patrick Farrell. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ntelitheos, Dimitrios. 2006. The Morphosyntax of Nominalizations: A Case Study. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ntelitheos, Dimitrios. 2013. Deriving Nominals: A Syntactic Account of Malagasy Nominalizations. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Pesetsky, David. 1985. Morphology and Logical Form. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 193–246. [Google Scholar]

- Postal, P. 1969. Anaphoric Islands. In Proceedings of the Fifth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Edited by Robert I. Binnick, Alice Davison, Georgia M. Green and Jerry L. Morgan. Chicago: CLS, pp. 205–19. [Google Scholar]