1. Introduction

This paper analyses a case of structural change in relative clauses in heritage speakers of two varieties of Venetan, a northern Italo-Romance language. It will be shown that appositive and restrictive relative clauses are not structurally distinguished in Brazilian Venetan, while they display different structural properties in Italian Venetan. It is possible to observe a difference in the realisation of resumptive pronouns in the two varieties: Italian Venetan distinguishes appositive and restrictive relative clauses by the realisation of a resumptive subject pronoun in the first but not in the second type; Brazilian Venetan never realises resumptive pronouns, regardless of the relative clause type. Other observations concerning the scope of the head noun and the ordering of relative clauses confirm that appositive and restrictive relative clauses are not structurally distinguished in Brazilian Venetan. It is concluded that a process of structural change is responsible for the pattern displayed by Brazilian Venetan, regardless of sociolinguistic factors and conditions in which the language is spoken.

The fact that structural change happens independently of extra-linguistic factors is confirmed by the fact that the two varieties of Venetan considered in the paper are spoken in quite similar conditions. Both of them are spoken in bilingual contexts and underwent contact with another language: Italian in Italy and Portuguese in Brazil. Moreover, both varieties display at least some properties of heritage languages: they are not the dominant languages of the society and they are used exclusively in informal contexts. The phenomenon described in the paper does not depend on transfer from another language and it is not exclusively a matter of processing, unlike what was argued in previous studies on heritage grammars (

Montrul 2004,

2008;

Pires and Rothman 2007): if that would be the case, similar changes would be expected in both Venetan varieties, contrary to the empirical evidence discussed in this study. The approach presented here aims to account for structural change in syntactic terms, without resorting to extra-linguistic factors. It will be proposed that heritage grammars are autonomous systems and follow predictable paths of language change; variation can take place in heritage languages, both at an interface level and at a syntactic level alike. Influence from the dominant language or simplification as a strategy to reduce processing costs is possible, but they should not be taken as the only triggers of change in heritage languages.

2. Venetan in Italy and Brazil

This paper considers two varieties of Venetan, an Italo-Romance language spoken in North-Eastern Italy, in its native settings, as well as an in a number of other countries, where it is still used by the descendants of the Venetan speaking emigrants that left Italy in the second half of the 19th century. The first variety considered is the Central Venetan variety spoken in Treviso (Italy); this variety will be referred to as Italian Venetan. The second variety considered in the study is the Venetan variety spoken by the community of descendants of Venetan immigrants in Bento Gonçalves (Brazil); this variety will be referred to as Brazilian Venetan.

Both varieties qualify as heritage languages: despite being quite vital in both settings, their use is limited to informal contexts. Venetan is protected by regional laws

1 in Italy, but the language does not have an official recognition nor standardised forms; both Brazilian and Italian Venetan are not the dominant languages of the society. All Venetan speakers in Italy and Brazil are bilingual and are, respectively, dominant in Italian and Brazilian Portuguese. Following

Rothman (

2009), varieties spoken in these conditions can be considered as heritage languages.

The Syntax of the Subject in Venetan Varieties

The syntax of the two Venetan varieties considered in this paper does not present major differences as far as subject realisation is concerned: both Brazilian and Italian Venetan are continuations of the Venetan varieties spoken in North-Eastern Italy in the 19th century

2.

Both varieties are pro-drop languages and display two paradigms of subject pronouns. The first paradigm includes the tonic forms, which evolved from Latin oblique forms; the second paradigm includes reduced clitic forms that evolved from Latin nominative personal pronouns. The two paradigms are reported in

Table 1.

Notice that while the tonic paradigm is complete, the clitic paradigm is defective, including only second person singular and third person forms.

The second person singular clitic and the third person forms have a rather different distribution, as noticed by

Vanelli (

1998) and

Benincà (

1994). The second person singular clitic is always obligatorily realised with finite verbs, while the third person clitics are generally realised with finite verbs whenever there is no other overt subject available. This difference emerges in particular in the context of doubling

3: while a second person singular subject clitic obligatorily doubles a tonic subject pronoun when present (1a), a third person subject clitic can be dropped (1b).

| (1) Italian Venetan |

| a. | Ti | te | vien. |

| | you | you | come.2sg |

| ‘You are coming.’ |

| b. | Ela | (la) | vien. |

| | she | she | come.3sg |

| ‘She is coming’. |

Despite this crucial difference in their distribution, all clitic forms have been traditionally analysed as agreement markers realised on T, playing a role comparable to that of verbal morphology (see in particular

Poletto 1993,

2000). While this analysis could be maintained for second person singular, more recent studies have challenged the agreement nature of third person clitics (

Pescarini 2020;

Schaefer 2020;

Frasson 2021), evidencing their pronominal behaviour. The distribution of Venetan third person subject clitics resembles that of French subject clitics, which have been analysed as reduced pronouns (‘weak pronouns’, in the classification presented in

Cardinaletti and Starke 1999) since the seminal works by

Kayne (

1975,

1983).

The nature of subject clitics will not be discussed in detail in this paper, but it will be maintained that, based on their distributional properties, an analysis of third person subject clitics as pronouns is to be preferred. This is particularly evident in Brazilian Venetan

4, with respect to the discourse-related properties of subject clitics. Not only can third persons be dropped when another subject is realised, they can also be dropped in contexts of topic continuation when no other subject is realised, a behaviour that is typical of pronouns rather than of agreement markers.

| (2) Brazilian Venetan |

| La nona | (la) ga | nasesto | en Alemania. | Dopo | (la) | se | ga | criado en Italia. |

| the grandmother | she have.3sg | born | in Germany | then | she | refl | have.3sg | grown in Italy |

| ‘My grandmother was born in Germany. Then she grew up in Italy’ |

In the first part of example (2), the subject DP

la nona is not doubled by the subject clitic

la; if subject clitics were obligatory agreement markers realised on T, nothing would prevent the doubling. In the second part of the example, an overt subject clitic

la is not felicitous in the context of topic continuation. These facts evidence the pronominal nature of subject clitics; this analysis will be adopted in the remainder of the paper. The pronominal nature of third person subject clitics allows to capture their peculiar distribution in relative clauses, as shown in

Section 3.

3. Appositive and Restrictive Relative Clauses

A relative clause can be defined as a complex expression contained within another expression.

De Vries (

2001), following the traditional description of relative clauses, defines a relative clause as clausal modifiers of an NP, called an antecedent or head NP. Consider the following Portuguese example (3):

| (3) Portuguese |

| O | livro | [RC que | o | Marcos | leu]. |

| the | book | that | the | Mark | read.pst |

| ‘The book that Mark read.’ |

The relative clause in (3) is introduced by the relative pronoun

que, which establishes a dependency with the head NP

livro. Both the head NP and the relative clause are contained inside a DP; in the present analysis, the relative pronoun is taken to be a determiner (see

Bianchi 1999;

De Vries 2001 in this respect).

Different hypotheses have been proposed to explain the structural relation between relative clauses and their antecedent (the head NP). One hypothesis predicts that the head NP is merged outside the relative clause (

Chomsky 1977;

Safir 1986;

Browning 1991). An alternative hypothesis predicts that the head NP is raised from inside the relative clause (

Kayne 1994;

De Vries 2006). This study adopts a raising approach to relative clauses, namely

De Vries’s (

2006) promotion analysis, discussed in

Section 3.1. In the two types of relative clauses taken into account in this study (appositive and restrictive relative clauses), the head NP is raised to the specifier position of the relative DP. Cross-linguistically, appositive and restrictive relative clauses are superficially very similar; however, there are differences between the two structures at the interpretive and syntactic levels.

At the interpretive level, a restrictive relative clause restricts the reference of the head NP (4), while an appositive relative clause adds some information about the head NP (5).

| (4) Portuguese |

| As meninas | [RRC que | tem | dez | anos] | vão | para | escola |

| the girls | that | have.3pl | ten | years | go.3pl | for | school |

| ‘Girls that are ten years old, go to school.’ |

| (5) Portuguese |

| As meninas, | [ARC que | tem | dez | anos], | vão | para | escola |

| the girls | that | have.3pl | ten | years | go.3pl | for | school |

| ‘The girls, which are ten years old, go to school.’ |

The two structures are superficially very similar in Portuguese, but their interpretation is different; the restrictive relative clause limits the reference of the head NP only to the group of girls that are ten years old; the appositive relative clause adds some further specification or information about the girls that go to school, namely the fact that they are ten years old.

Several studies (see, for instance,

Demirdache 1991 in this respect) show that the different interpretations depend on a syntactic difference, in that the two structures are attached at different levels inside the DP.

In order to understand how the different interpretations are linked to the different attachment of the two relative clause types, consider example (6): a restrictive relative clause is in the scope of a determiner of a quantifier of the head NP, while an appositive relative clause is not.

| (6) Italian |

| a. | Tutti | gli | studenti | [RRC che | hanno | passato l’ | esame] | sono | tornati | a | casa. |

| | all | the | students | that | have.3pl | passed | the exam | are.3pl | come.prt | at | home |

| ‘All the students that passed the exam came back home.’ |

| b. | Tutti | gli | studenti, | [ARC che | hanno | passato | l’ | esame], | sono | tornati | a | casa. |

| | all | the | students | that | have.3pl | passed | the | exam | are.3pl | come.prt | at | home |

| ‘All the students, who passed the exam, came back home.’ |

In the restrictive relative clause in (6a),

tutti gli takes scope over both the head NP and the relative clause; in the appositive relative clause (6b),

tutti gli takes scope over the head NP but not the relative clause, triggering the difference in the interpretation. This difference depends on the fact that the scope of a determiner D is defined by its c-command domain; the appositive relative clause is not in the c-command domain of D, hence not in its scope. In most approaches, the difference in the two structures is ascribed to the different levels to which they are attached inside the DP: both structures are subordinate clauses embedded within a DP and form a constituent with it, but restrictive relative clauses are more deeply embedded, as shown in (7).

This structural difference explains the different scope of determiners and quantifiers of the head noun in (6a) and (6b).

The different attachment level also results in a precise relative order of the two structures: appositive relative clauses generally follow restrictive relative clauses.

| (8) |

| a. | La | signora | [RRC che | è | venuta | in | negozio], | [ARC che | è | mia | zia], | ha | comprato | dei | vestiti. |

| | the | lady | that | is | come.prt | in | shop | which | is | my | aunt | has | bought | of.the | clothes |

| ‘The lady that came to the shop, which is my aunt, bought some clothes.’ |

| b. | *La | signora, | [ARC che | è | mia | zia], | [RRC che | è | venuta | in | negozio], | ha | omprato | dei | vestiti. |

| | the | lady | which | is | my | aunt | that | is | come.prt | in | shop | has | bought | of.the | clothes |

| ‘The lady, which is my aunt, that came to the shop, bought some clothes.’ |

This property follows from the fact that restrictive relative clauses, unlike appositive ones, are embedded inside the head NP. Restrictive relative clauses are more strictly dependent on the head NP in this respect. The approach presented in

Section 3.1 (

De Vries 2006) captures this difference between appositive and restrictive relative clauses in structural terms.

3.1. The Promotion Analysis

De Vries (

2006) maintains that the two types of relative clauses have a different syntactic behaviour that depends on their attachment level; he proposes that both appositive and restrictive relative clauses have a similar internal structure (9):

| (9) De Vries (2006) |

| a. | Restrictive | relative | clause: | [DP | [D | [CP-REL | [DP-REL | NPi | [D-REL | RPi | [NPi]]]] | ]] |

| b. | Appositive | relative | clause: | [DP | [D | [CP-REL | [DP-REL | Øk | [D-REL | RPk | [(NPi)]]]] | ]] |

In both structures, a relative pronoun (‘RP’) is in D-REL. In restrictive relative clauses, the relative pronoun is co-indexed with the head NP, which further moves to Spec-DP-REL (9a). In appositive relative clauses, the relative pronoun is co-indexed with an abstract null NP in Spec-DP-REL (9b); the head noun, in this case, is implicit and its position is empty. In other words,

De Vries (

2006) argues that the syntactic derivation of both constructions involves the promotion of an NP, but the relationship between the appositive relative clause and the head noun requires an additional step, because of the presence of a null pronominal element.

As shown in (9a), the head NP of restrictive relative clauses moves to Spec-DP-REL for case checking; the relative pronoun is directly bound by the head NP, which functions as an antecedent for it.

Appositive relative clauses have a parallel but more complex derivation: they are analysed as semi-free relative clauses attached in a coordination phrase CoP headed by a null &-head. The head NP is located in the first conjunct of the CoP, while the appositive relative clause is located in the second conjunct. What is promoted in this case is not the head NP, but a null abstract pronominal head Ø that functions as an antecedent for the relative pronoun.

| (11) |

| [CoP [DP1 NPi] [Co’ & [DP2 [D [CP-REL [DP-REL Øk [D-REL RPk [(NPi)]]]] ….]]]] |

The two conjuncts, DP

1 and DP

2, of the CoP have the same referent. The appositive relative clause is contained in the second conjunct and modifies an abstract pronominal head Ø. The appositive relative clause behaves like a free relative clause whose pronominal head is empty. Note that the relative pronoun is syntactically linked to Ø, the abstract pronominal antecedent of the free relative. In turn, Ø refers to the overt head NP in DP

1 in the first conjunct, but this link cannot be established syntactically, as the head NP does not c-command the second conjunct.

De Vries (

2006) proposes that the antecedent and the referring element in an appositive relative are in a cospecification relationship. This analysis has one immediate advantage: since free relatives are a special type of restrictive relative clause and coordination exists independently of appositive relative clauses,

De Vries (

2006) concludes that there is no need to assume the existence of an independent type of appositive relative clause. However, the derivation of appositive relative clauses, despite showing similarities with that of restrictive relative clauses, is made more complex by the presence of an abstract Ø and an additional extra-syntactic operation defined as cospecification.

De Vries further notes that appositive relative clauses can marginally contain an NP that functions as an additional internal head, a fact that further supports the indirect link of the relative clause with the head NP. This additional internal head cannot be realised in restrictive relative clauses, as the same position inside DP-REL in these structures is occupied by the head NP to be raised. An NP may, however, take the position of the implied head noun in a free relative, therefore in an appositive relative clause, too. This additional NP refers to the antecedent, instead of the pronominal element Ø.

| (12) Dutch (De Vries 2006) |

| “Jonge | sla”, | welk | gedicht | van | Rutger | Kopland | veel | gelezen | wordt, | is | herdrukt. |

| young | lettuce | which | poem | of | Rutger | Kopland | much | read.prt | was | is | reprint.prt |

| ‘“Young Lettuce”, which (poem by Rutger Kopland) is read by many people, has been reprinted.’ |

| (13) |

| [CoP [DP1 “Jonge sla”] [Co’ & [DP2 [CP-REL [DP-REL Øk [D-REL welkk gedicht]]]]]] |

Summarising, appositive and restrictive relative clauses have a similar internal structure. However, there are some relevant differences. The attachment of an appositive relative clause is more complex than that of a restrictive relative clause: both structures are embedded into a DP, but in the case of the appositive relative clause, the DP containing it behaves as an apposition which is coordinated to a first DP containing the head NP. Moreover, the promoted element is different in the two types: the head NP is raised in restrictive relative clauses and an abstract null pronominal in appositive relative clauses. Finally,

De Vries (

2006) showed that an additional internal NP paired with the relative pronoun can be realised in appositive relative clauses.

4. Subject Resumption in Venetan Relative Clauses

The possibility of having an additional element realised in appositive relative clauses has been shown for Venetan in

Benincà (

1994): a subject clitic, functioning as a resumptive subject pronoun, appears in appositive relative clauses. Similar to the additional anaphoric epithet shown in (12) for Dutch, the additional subject clitic in Venetan does not refer to the empty pronominal head of the relative clause, but to the head noun. Therefore, it is possible to say that Venetan distinguishes appositive from restrictive relative clauses by means of a resumptive pronoun in the first but not in the second structure.

In

McCloskey (

1990), among others, a resumptive pronoun is defined as a personal pronoun that occupies the position corresponding to the grammatical function of the head noun. In the case under analysis, this is the subject. Being resumptive, this pronoun appears in a position in which a gap would appear in other contexts and is used to restate an antecedent, the head noun.

Note that subject resumption is not very common cross-linguistically, as suggested by

Keenan and Comrie (

1977): in the hierarchy of accessibility of resumptive pronouns’ antecedents, subjects occupy the leftmost position. Resumptive pronouns, however, are expected to occur more frequently when referring to antecedents in the rightmost positions, because of their greater processing difficulties.

| (14) Accessibility hierarchy (Keenan and Comrie 1977) |

| Subject > Direct object > Indirect object > Oblique > Genitive |

McCloskey (

1990) defines the fact that a resumptive pronoun generally does not appear in the subject position immediately subjacent to the head noun as the Highest Subject Restriction (

McCloskey 1990). In Italian Venetan, this restriction is violated, as a resumptive pronoun is realised precisely in this context.

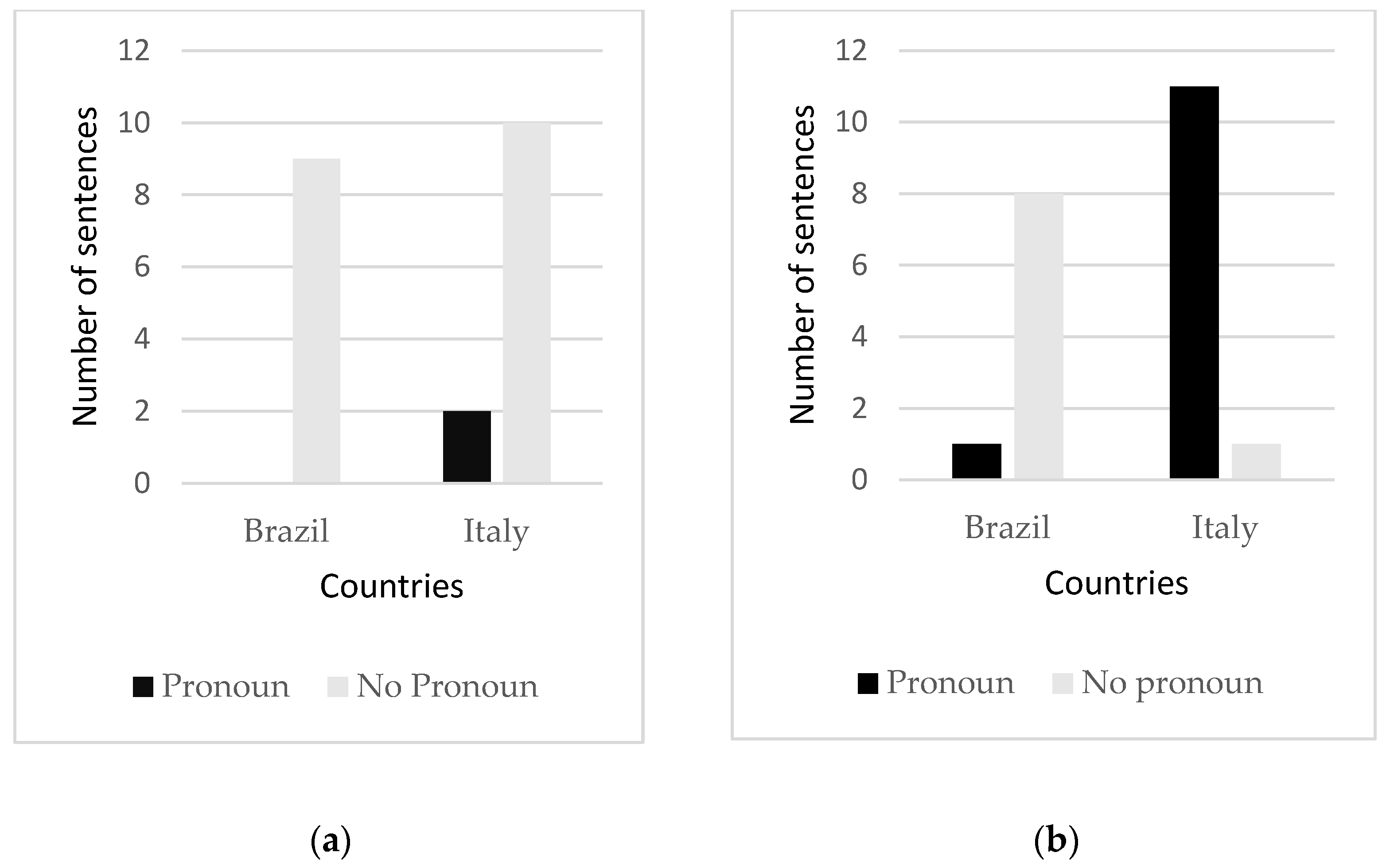

Appositive and Restrictive Relative Clauses in Brazilian and Italian Venetan

Italian Venetan and Brazilian Venetan display a difference in the use of resumptive subject pronouns in relative clauses. In particular, while Italian Venetan realises a subject clitic in appositives, but not in restrictives, Brazilian Venetan never realises subject clitics, regardless of the relative clause type.

The distribution of subject clitics in appositive and restrictive relative clauses in Italian Venetan was studied by

Benincà (

1994). She noted that a subject clitic needs to be realised in appositive relative clauses (15), but it is not grammatical in restrictive relative clauses (16).

| (15) Italian Venetan |

| Le | tose, | che | le | ga | diese | ani, | le | va | scuola. |

| the | girls | which | they | have.3pl | ten | years | they | go. 3pl | school |

| ‘The girls, which are ten years old, go to school.’ |

| (16) |

| Le | tose | che | ga | diese | ani, | le | va | scuola. |

| the | girls | that | have.3pl | ten | years | they | go.3pl | school |

| ‘Girls that are ten years old, go to school.’ |

This situation parallels the one described by

De Vries (

2006) for Dutch: the subject clitic in Italian Venetan functions as an additional internal head and takes the position of the implied head noun, referring to the external head noun.

| (17) |

| [CoP [DP1 Le tosei] [Co’ & [DP2 [CP-REL [DP-REL Øk [D-REL chek [lei]…]]]]]] |

This is not possible in restrictive relative clauses, as the NP complement position of D-REL is occupied by the head noun to be raised.

| (18) |

| [DP Le tosei [D [CP-REL [DP-REL NPi [D-REL chei [NPi/*lei]]]] ….]] |

The data contained in the Microcontact corpus of Brazilian Venetan

5 display a different situation. Speakers of Brazilian Venetan do not distinguish the two structures by realising a subject clitic in appositive relative clauses. Both structures are realised without a resumptive pronoun and are therefore distinguished only by intonation.

| (19) | Le | tose, | [ARC che | ga | diese | ani], | va | scuola. |

| | the | girls | which | have.3pl | ten | years | go.3pl | school |

| | ‘The girls, which are ten years old, go to school.’ |

| (20) | Le | tose | [RRC che | ga | diese | ani], | va | scuola. |

| | the | girls | that | have.3pl | ten | years | go.3pl | school |

| | ‘Girls that are ten years old, go to school.’ |

The two types of data are, of course, very different: Benincà’s data refer specifically to Paduan, a variety of Italian Venetan; the data from the Microcontact corpus come from a semi-guided production task carried out with elderly speakers of Brazilian Venetan in different locations. There are many linguistic and extra-linguistic variables that could have altered the way speakers produced the sentences in the corpus. In order to obtain more comparable data, a short online questionnaire was carried out for the present study, involving speakers of Italian and Brazilian Venetan with comparable sociolinguistic profiles.

6. Analysis

In this section, it will be proposed that the difference between the two Venetan varieties is structural: crucially, the two types of relative clauses are not distinguished at a syntactic level in Brazilian Venetan, maintaining however the interpretive difference discussed in

Section 3.

In Italian Venetan, appositive and restrictive relative clauses are structurally distinguished because of their attachment in the clause. While restrictive relative clauses are the complement embedded within the DP, appositive relative clauses are analysed as free relative clauses realised in a coordination phrase. A simplified version of this structural difference, addressed in

Section 3, is given in (26):

| (26) |

| [CoP [DP DP [RRC]] [Co’ & [ARC]]] |

This difference implies that the restrictive relative clause is embedded in the DP headed by the head noun, while the appositive relative clause is not. Moreover, the relationship of the appositive relative clause with the head noun is more complex: it does not refer directly to the head noun, but to an abstract null pronoun, which in turn is in a cospecification relationship with the head noun. In this respect, the derivation of appositive relative clauses is then more complex both at the structural and processing level. Appositive relative clauses are structurally more complex in the sense of

Roberts and Roussou (

2003): an apposition is a form of adjunction, and the presence of adjuncts makes the syntactic structure more complex, in that, an extra segment of structure needs to be added; conversely, restrictive relative clauses are complements of DP, hence no extra structure is added. Moreover, at the level of processing,

Sorace (

2011) showed that syntactic relationships are less costly to process than interface processes; the relation of cospecification required in the appositive relative clause is a type of discourse linking and as such, it requires additional processing efforts by the speakers

9.

In the case of Brazilian Venetan, both appositive and restrictive relative clauses display the same structure and do not allow resumptive subject clitics. Appositive relative clauses are analysed as regular restrictive relative clauses, possibly also in view of the similarity between the two structures. The two structures are still distinguished in their interpretation and intonation; however, at the syntactic level, the two structures are not distinguished. This proposal captures the different distribution of subject clitics in the two varieties of Venetan. If appositive and restrictive relative clauses are not structurally different in Brazilian Venetan, in that they both behave as restrictive relative clauses, there is no empty position for the subject clitic to be realised. Recall that restrictive relative clauses have the structure in (27):

| (27) |

| [DP NPi [D [CP-REL [DP-REL NPi [D-REL RPi [NPi/*SCli]]]] ….]] |

A subject clitic is not allowed in the subject position inside the relative clause as it is already occupied by the head noun, which will be subsequently moved to the specifier of the relative DP.

Further Evidence and Possible Problems for the Analysis of Structural Change

Informants that took the questionnaire were also asked to judge

10 some further sentences in Venetan

11, to check for possible factors that could support or contradict my hypothesis on structural change.

The first property is the order of relative clauses in sentences in which both a restrictive and an appositive relative clause are found. As shown in

Section 3, appositive follow restrictive relatives. This order depends on the fact that restrictive relative clauses are embedded within the maximal projection of the antecedent DP, while appositive relative clauses are in the second conjunct of a coordination phrase; therefore, restrictive relative clauses cannot be separated from the head NP by an appositive relative clause. This is the case in Italian Venetan:

| (28) Italian Venetan |

| a. | Le | tose | [RRC che | riva | ancuò], | [ARC che | le | ga | dieze | ani], | le | va | scuola. |

| | the | girls | that | arrive.3pl | today | which | they | have.3pl | ten | years | they | go.3pl | school |

| | ‘The girls that arrive today, that are ten years old, go to school.’ |

| b. | *Le | toze, | [ARC che | le | ga | dieze | ani], | [RRC che | riva | ancuò], | le | va | scuola. |

| | the | girls | which | they | have.3pl | ten | years | that | arrive.3pl | today | hey | go.3pl | school |

| | ‘The girls, which are ten years old, that arrive today, go to school.’ |

The Brazilian Venetan informants, however, accepted both orders:

| (29) Brazilian Venetan |

| a. | Le | tose | [RRC che | riva | ancuò], | [ARC che | ga | dieze | ani], | va | scuola. |

| | the | girls | that | arrive.3pl | today | which | have.3pl | ten | years | go.3pl | school |

| ‘The girls that arrive today, that are ten years old, go to school.’ |

| b. | Le | toze, | [ARC che | ga | dieze | ani], | [RRC che | riva | ancuò], | va | scuola. |

| | the | girls | which | have.3pl | ten | years | that | arrive.3pl | today | go.3pl | school |

| | ‘The girls, which are ten years old, that arrive today, go to school.’ |

This fact supports the hypothesis of a structural change in Brazilian Venetan relative clauses: the possibility of inverting the order of the two relative clauses shows that they stand in the same relation with the head NP, in that they are both embedded inside a DP; the ordering in (29b) cannot be accounted for if we maintain that appositive relative clauses are realised in the second conjunct of a coordination phrase. For a comparison, notice that the same inversion of the order of the two types of relative clauses is possible in other heritage Italo-Romance varieties spoken in Brazil, such as Calabrian:

| (30) Brazilian Calabrian |

| a. | I | calabresǝ | [RRC ch’ | avianǝ | venutǝ | prima | ‘ra | guerra], | [ARC che | nun | arlavano | italiano]. |

| | the | Calabrians | that | had.3pl | come.prt | before | the | war | that | not | spoke.3pl | Italian |

| | ‘The Calabrians that had come before the war, who did not speak Italian.’ |

| b. | I | calabresǝ, | [ARC che | nun | parlavano | italiano], | [RRC ch’ | avianǝ | venutǝ | prima | ‘ra | guerra]. |

| | the | Calabrians | that | not | spoke.3pl | Italian | that | had.3pl | come.prt | before | the | war |

| | ‘Calabrians, who did not speak Italian, that had come before the war.’ |

Examples (30a,b) suggest that the structural change displayed by Brazilian Venetan could be a common process among heritage languages. More data are necessary in order to pursue this hypothesis.

A second property of appositive relative clauses is opacity for variable binding, which was discussed in

Demirdache (

1991) and

De Vries (

2006). This opacity depends on the fact that in coordinated structures, such as appositive relative clauses, the first conjunct does not c-command the second conjunct; as a consequence, variable binding in appositive relative clauses is not possible. However, this is possible in restrictive relative clauses. Consider the Italian Venetan examples in (31):

| (31) Italian Venetan |

| a. | Qualchedunii | ga | parlà | dela | cesa | [RRCi che | gavea | visità]. |

| | somebody | have.3pl | talk.prt | of.the | church | that | had.3pl | visit.prt |

| | ‘Somebody talked about the church that they had visited.’ |

| b. | Qualchedunii | ga | parlà | dela | Basilica | de | Sant’Antonio, | [ARC*i/j che | i | gavea | visità]12. |

| | somebody | have.3pl | talk.prt | of.the | Basilica | of | Saint Anthony | that | they | had.3pl | visit.prt |

| | ‘Somebody talked about the Basilica of Saint Anthony, which they had visited.’ |

As already shown in

Section 3, a restrictive relative clause is c-commanded by the head NP; in (31a), the relative clause is also c-commanded by the QP qualcheduni, being therefore interpreted under the scope of the quantifier. In the case of the appositive relative clause in (31b), there is no c-command relationship with the antecedent: the relative clause is adjoined in the second conjunct of the CoP. The impossibility of establishing syntactic dependencies holds also for the higher QP qualcheduni: the appositive relative clause cannot be interpreted under its scope and the subject clitic i can only be referential.

The situation in Brazilian Venetan is different, as speakers accepted both structures. Both appositive and restrictive relative clauses can be interpreted under the scope of the quantifier qualcheduni.

| (32) Brazilian Venetan |

| a. | Qualchedunii | ga | parlà | sora | la | cesa | [RRCi che | gavea | visità]. |

| | somebody | have.3pl | talk.prt | over | the | church | that | had.3pl | visit.prt |

| | ‘Somebody talked about the church that they had visited.’ |

| b. | Qualchedunii | ga | parlà | sora | la | Basilica | de | Santo | Antonio, | [ARCi che | gavea | visità]. |

| | somebody | have.3pl | talk.prt | over | the | Basilica | of | Saint | Anthony | that | had.3pl | visit.prt |

| | ‘Somebody talked about the Basilica of Saint Anthony, which they had visited.’ |

The grammaticality of (32b) confirms that the relative clause is embedded in the antecedent DP; only this configuration allows the c-commanding relationship that exists between the relative clause and the quantifier. If appositive relative clauses were realised in a different coordinated conjunct, (32b) would be ungrammatical.

7. Alternative Analyses and Possible Problems with Them

This paper assumes that heritage languages function as independent systems and changes in heritage grammars and follow the general pattern of language variation. In other words, variation attested in heritage grammars do not necessarily depend on the contact language. Changes that go in the direction of a stronger similarity with the dominant language of heritage speakers can be coincidental, and the influence of the dominant language cannot be generalised.

This section briefly considers two alternatives to this notion, showing that they cannot be applied to the case of Venetan. The potential counterarguments for the present analysis of change consist of the problem of language representation and transfer and the role of processing of discourse-related information. These factors could potentially play a role in the change, but arguments in favour of such alternative causes of change cannot be maintained in the case of relative clauses.

The problem of language representation in bilingual speakers is addressed, among others, in

Hulk and Müller (

2000). They proposed that bilingual speakers are able to distinguish their two languages from very early on, but this does not exclude the possibility of an influence from one language to the other. This phenomenon, labelled cross-linguistic influence, is most likely to occur if one of the two languages spoken by the bilingual has a syntactic construction that seems to allow for more than one syntactic analysis and the other language contains evidence for only one of these two possible analyses.

Montrul (

2004) further proposed that, in heritage languages, structures of the dominant language are most likely transferred to the heritage language when the input evidence from the two languages is conflicting. This proposal cannot be applied to the case under analysis for various reasons. First of all, the hypothesis that Venetan and Portuguese provide speakers with conflicting evidence with respect to the realisation of relative clauses is untenable: there is no evidence that Brazilian Portuguese has a simplified (or anyway different) realisation of appositive and relative clauses, therefore it could not trigger the change process in Brazilian Venetan, too.

The question of whether transfer from the dominant language took place could possibly be moved to the distribution of overt subject pronouns. Venetan and Brazilian Portuguese differ in that the first is a consistent null-subject language, while the second is a partial null-subject language and it generally does not allow for third-person referential null subjects (see

Holmberg 2005 for an overview); therefore, Venetan speakers receive different information from the two languages. In the case of subject resumption in relative clauses, however, the hypothesis cannot be maintained. In this sense, Brazilian Portuguese should provide speakers with conflicting influence with respect to the realisation of subject pronouns in appositive relative clauses. This is not necessarily the case.

Kato and Nunes (

2009) showed that subject resumption is possible in appositive relative clauses in non-standard varieties of Brazilian Portuguese:

| (33) Brazilian Portuguese (adapted from Kato and Nunes 2009) |

| Uma | amiga, | que | ela | é | muito | engraçada. |

| a | friend | that | she | is | very | nice |

| ‘A friend, which is very nice.’ |

Example (33) shows that in non-standard Brazilian Portuguese, it is possible to have a subject pronoun realised in the relative clause. Recall that in Italian Venetan, this is also the case: a subject clitic is realised in appositive relative clauses. I take both cases to depend on the availability of an empty subject position, which is taken by the head NP in restrictive relative clauses.

A second problem with this hypothesis is represented by the fact that subject resumption is not possible in Italian. Recall that Italian Venetan speakers are all dominant in Italian, so we should expect to see effects of language contact in this variety, too. Italian, however, does not allow for subject resumption in appositive relative clauses:

| (34) Italian |

| Ho | un’ | amica, | che | (*lei) | è | molto | simpatica. |

| have.1sg | a | friend | that | she | is | very | nice |

| ‘I have friend, which is very nice.’ |

Being in contact with a language that disallows subject resumption in appositive relative clauses, Italian Venetan should favour subject drop in the same contexts, if transfer from the dominant language happened. However, Italian Venetan realises subject clitics; as shown throughout the paper, Brazilian Venetan, which is spoken in contact with a language that allows for resumptive pronouns, displays subject clitic drop. Therefore, comparing the data from the two Venetan varieties to the dominant languages spoken by Venetan speakers in Italy and Brazil, it is clear that the transfer hypothesis cannot be maintained: the system displayed by Brazilian Venetan cannot be the result of transfer from Brazilian Portuguese, which also displays subject resumption in appositive relative clauses. At the same time, if a change was to be caused by transfer, there is no clear explanation as to why Italian Venetan does not display a simpler system, too.

A second possibility related to the distribution of null and overt subjects regards the problems with the processing of information at the syntax-discourse interface by bilingual speakers. This notion is fundamental in the last version of the interface hypothesis (

Sorace 2011), according to which the processing of discourse information is problematic for bilingual speakers of null-subject languages, especially when the second language of such speakers has a different distribution of null subjects or does not allow for null subjects at all. In the case of null subjects, this hypothesis predicts that bilingual speakers extend the use of overt subjects to contexts that would otherwise favour a null subject. This ‘simplification’ depends on the fact that null subjects are referentially more ambiguous and more costly to process, while overt subjects are not ambiguous and therefore easier to process. In the case under analysis, we would expect to see an extension of overt subjects to contexts in which a null subject would be the preferred choice. However, this is not the case in Brazilian Venetan relative clauses. The data does not show an extension of overt subjects, but an extension of null subjects to a context that otherwise requires an overt subject in Italian Venetan. This situation contradicts the studies on the realisation of subjects in bilingual speakers: the extension of null subjects would make the system more ambiguous, instead of decreasing the level of referential ambiguity. It is concluded that, while the processing of pragmatic and discourse-related information needs to be always taken into account while addressing change in contact (as in the case of cospecification described in

Section 3), the perspective of structural change also needs to be accounted for, especially in cases in which the change does not directly depend on interface conditions. Moreover, while the contact language can play a role at some levels of language representation, it is not the case that all cases of convergence in heritage languages depend on direct transfer from the dominant language.

The Autonomy of Heritage Grammars

Given the impossibility of reconciling the data presented in this study with previous studies on the role of language representation, transfer and processing, the case of relative clauses in Brazilian Venetan is taken to represent a peculiar case of divergent attainment (

Kupisch and Rothman 2018;

Pascual y Cabo and Rothman 2012;

Polinsky 2018;

Putnam and Sánchez 2013). Heritage grammars are not incompletely acquired (as earlier proposed in

Montrul 2008), but are internally consistent grammars, organised by systematic principles (

Polinsky 2018). Heritage speakers are native speakers of their language, which is complete but may potentially diverge from other varieties of the same language (

Kupisch and Rothman 2018).

The case of heritage Venetan varieties, however, requires a further specification of the concept of divergence. As shown in

Section 2, Italian Venetan cannot be taken as a prototypical homeland variety and there are no baseline speakers of Venetan in Brazil to identify the starting point of divergent properties in the structure of relative clauses. Moreover, both varieties underwent contact with another language, even though there is no direct effect of language contact on the structure of relative clauses. In this situation, it does not seem the case that Brazilian Venetan ‘diverged’ from Italian Venetan; it is rather the case that the two varieties followed autonomous paths of development which led to the establishment of different structural properties. Both varieties are spoken by unbalanced bilinguals that are dominant in another language (Italian in Italy, Portuguese in Brazil): it is therefore not possible to confirm that the simpler structure of Brazilian Venetan is the result of a simplification process triggered by language contact, as such process should be expected in Italian Venetan, too. In conclusion, the reduction of structural complexity attested in Brazilian Venetan is better captured as a diachronic process of structural change, in which simpler syntactic structures are preferred to more complex ones, as shown in

Roberts and Roussou (

2003)

13.

8. Conclusions

This paper discussed the realisation of appositive and restrictive relative clauses in two varieties of the same language: Italian Venetan and Brazilian Venetan. The final goal of the paper was to test the possibility of accounting for heritage language change in syntactic terms, excluding possible sociolinguistic or interface issues. It was shown that what could superficially be ascribed to a difference in the availability of resumptive pronouns in appositive relative clauses in the two varieties requires a more detailed analysis of structural change. This is shown by a number of facts related to the scope and ordering of relative clauses. It was proposed that the different interpretations of appositive and restrictive relative clauses are maintained in both Venetan varieties, while the difference between them can be interpreted in purely structural terms.

Brazilian Venetan underwent a process of structural change similar to the diachronic process described in

Roberts and Roussou (

2003): appositive relative clauses, being adjuncts, are structurally more complex than complements, being, therefore, more prone to change. Such complexity is not the result of transfer from the dominant language of Brazilian Venetan speakers and can be only partially ascribed to pure processing factors: Brazilian Portuguese does not display a similar phenomenon and it was not possible to identify difficulties in the processing of the structures under analysis. It was concluded that in the case under analysis, the change is structural: such change does not require a special analysis, as it conforms to general diachronic syntactic change. Brazilian Venetan grammar followed an autonomous development along a prototypical diachronic path. The case of Venetan varieties shows that heritage grammars are autonomous systems and follow predictable paths of language variation, as such, changes may take place at an interface and at a syntactic level alike. This does not exclude possible influences from the dominant language, which, however, do not need to be taken as the only triggers of change.